#Else Siegle

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Profile Press Ephemera

In a previous post, I mentioned my former boss and friend Fred R. Siegle. He and his wife Else are pictured above. Fred ran a print shop called Profile Press. It was on 25th Street and Seventh Avenue in Manhattan, in a building that housed printers and binderies and type houses. The upper 20s was filled with the printing industry and then a bit farther north began the garment district.

Profile Press was my first real job out of college in 1972. I did have a short run with another designer, doing paste-ups of really schlocky packaging where the environment was toxic, and my co-worker was sexually harassing and blackmailing the boss. Getting the job with Fred was a life-saver.

In reality, Fred was a printing broker and a designer. His clients included many of the finest art galleries—Betty Parsons, OK Harris, Marlborough, and more.— along with small publishers and a variety of interesting people in the arts.

Each year, Fred self-published a charming keepsake book for his clients and delivered them during the holidays. Fred learned design during the 20's and 30's and his style reflected that.

I have been buying them whenever I see them available on used bookstore sites. Here are some examples, some which are available on Amazon or Oak Knoll Books.

#ProfilePress#Profile Press#Fred Siegle#else Siegle#printing industrty 1970#Susan McCaslin#vintage#1970s#isearchedandfound#searchedfound#new haven artist

0 notes

Note

I adore ur art style, what are ur inspirations and what are your social media handles other than tumblr?? I’d love to follow you everywhere else :)

Ah, thank you - that's very kind! My earliest (and biggest) inspiration was definitely VivziePop, in terms of her art style and character design (I don't know all that much about her as a person), hence the Hazbin content on my blog! And more recently I've been taking inspiration from Tracy Butler and Fable Siegle of Lackadaisy fame. Apart from that, I couldn't give you a solid list of names, sadly. I mostly find inspiration on Pinterest, which has a bit of a crediting problem. But I like anything loose, sketchy and textured, so I have a lot of fun with digital brushes that try to emulate traditional media! Pencils and inks and all that jazz.

As for the second half of your ask, I’m touched, but I'm not online anywhere but Tumblr ^^” Posting to social media in general is a very new thing for me, and the same goes for making fan art. That Dr. Facilier / Husk fusion is the first drawing I’ve uploaded to the Net (and let stay up for more than a couple hours) in years! /lh

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

LACKADAISY (Pilot)

youtube

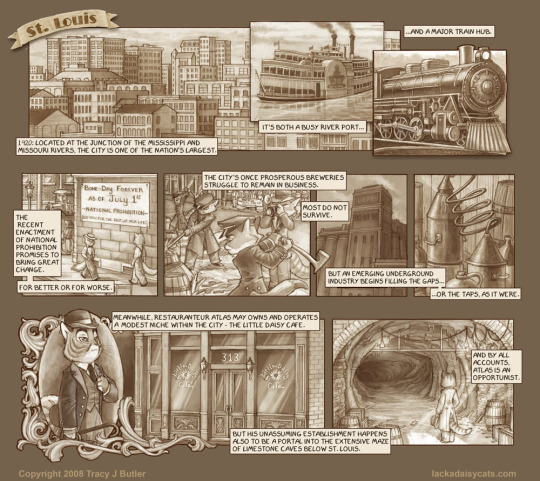

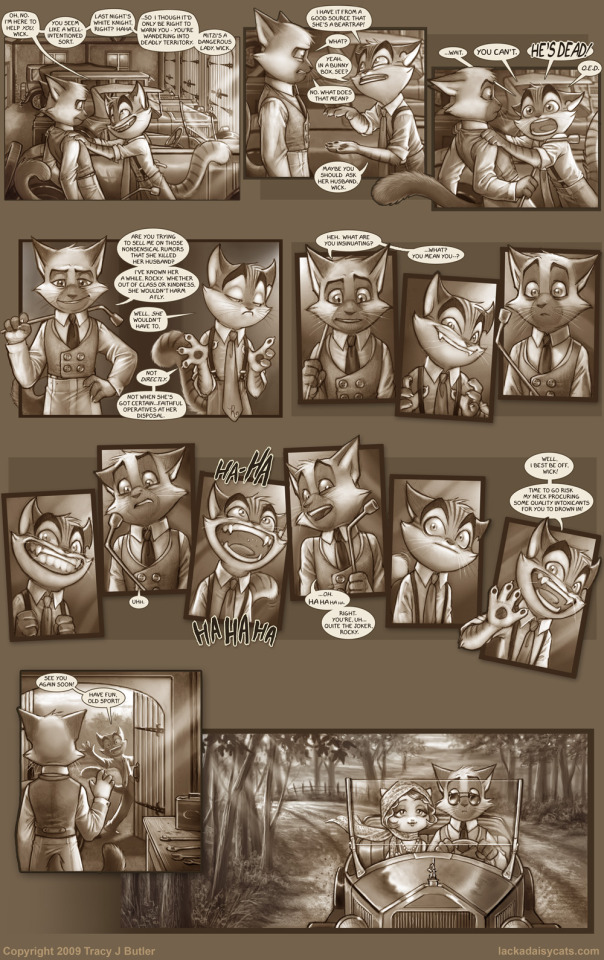

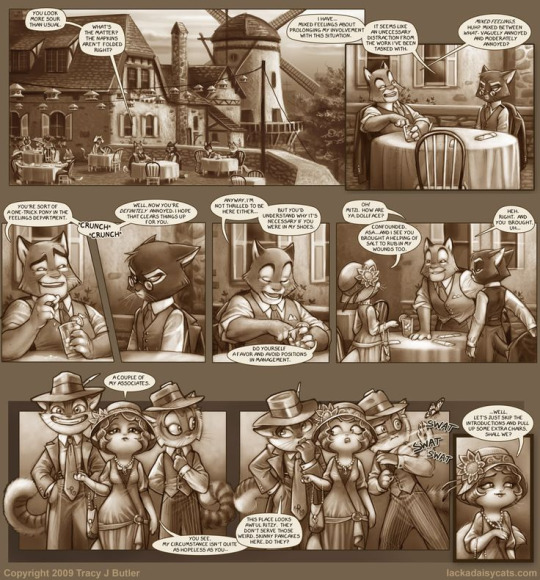

LACKADAISY is a 2D animated film pilot based on the 2006 comic series by Tracey J. Butler, directed by Fable Siegle, and produced by Iron Circus Animation. Released only 2 months ago as of June 15th 2023, LACKADAISY is a labor of love animated by over 160 artists around the world! The pilot introduces us to St. Louis Missouri in the year 1927, prohibition is in full effect and the impending doom of their beloved bar looms over the characters heads. Those characters including Rocky, Freckle and Ivy, three cats trying their hardest to smuggle alcohol into the city despite the challenges they face.

My Thoughts:

!!!SPOILERS AHEAD!!!

What else can I say other than this film was phenomenal! I was incredibly impressed by how smooth the animation is and I love, love, loved the character designs! All of them were unique and had their own sort of spunk and interest while keeping a cohesive look. Let's take a moment to appreciate the artwork for this show shall we?

This image here is an excellent example of creative character design within a certain art style! Shape language, body language, facial expression, and color are all used in subtle ways to express the character's personality!

An important detail to remember is that LACKADAISY was originally a comic, so some things had to be changed to translate it from comic to film.

The original comics primarily used warm, detailed pictures that focused more on shading and texture rather than color. The artwork has a similar warm, almost brown tone that some film photographs from the area take on. Whether that is on purpose I have no idea, it was just something I noticed. These images are from the comics, just to give you a better idea of what I mean.

Even when color is added that detailed artwork and focus on shading remains. Giving the viewer stunning scenes to look at, like these.

Gorgeous right?

But one thing you notice right off the bat is that with the animated pilot, the detail and the emphasis on shading have decreased significantly. But that is to be expected with an animated show, as those things are well... hard to animate. However, what is lacking in detail and shading is made up for in color! The animated pilot is packed full of color and light, which I really enjoy.

Personally, I believe they did a really good job adapting a comic into an animated pilot, if you have anything to add or any animations you want me to look over let me know in the suggestion box! Anyways! be sure to send the people behind this amazing pilot (and comic) some love and support! signing off for now,

-N.Ink

#Youtube#lackadaisy#cats#catslover#2d animation#tv show#tv show pilot#cats the musical#animation#cartoon#comic#Animations you should know about#2d animated film#animals#furry?#film review

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“Sometimes it’s a curse, and sometimes it’s a blessing,” said Greg Siegle, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist at the University of Pittsburgh. He studies the brains of C-PTSD patients, and he told me that my suspicions were right—there were many ways in which C-PTSD could be considered an actual asset. “I call them superpowers,” he told me. “So many of what we call psychopathologies are actually skills and capabilities gone awry.”

Much of my research had stated that people with PTSD had shrunken prefrontal cortices—that experiencing triggers often shut down the logical centers of our brains and left us irrational and incapable of complex thought. But Siegle told me he’d discovered that research to be flawed. He’d found that for many people with complex PTSD, the exact opposite was happening. In moments of intense stress and trauma, our prefrontal cortices were actually far more active.

Normally, if you’re facing a threat, your body immediately reacts to it. Your heart starts pumping blood. The hair on the back of your neck stands up. This is all in service of getting blood to your legs so you can run the hell away from it. On top of this, you feel your heart beating faster. You recognize that you’re freaking out. That makes you even more anxious, and your heart beats even faster.

But Siegle told me, “As far as we can tell with complex PTSD, in really stressful situations, you’ve got this coping skill that allows the prefrontal cortex to just shut off some of our evolutionary freak-out mechanisms and instead have high levels of prefrontal activity. So our bodies stop reacting.”

In other words, in some moments of intense stress, we are super-duper good at dissociation. Our hearts don’t pump as hard. Our brains cut themselves off from our bodies, so we don’t really have that feedback loop of getting anxious about getting anxious. Instead, our prefrontal cortices blink online—we become hyperrational. Super focused. Calm.

Siegle explained it this way: “If running away has never been an option for you, you have to be cunning and do other things. So it’s like, this is time to bring all of our resources online, because we’re going to survive this.”

People with C-PTSD might have an outsized, gnarly freak-out about a cockroach in the house or a flash of anger on someone’s face. But in times of real danger—when someone furious is coming toward us with an actual machete in their hand, ready to kill—we face the problem head-on, while everyone else is cowering. A lot of the time, we’re the ones getting shit done.”]

Stephanie Foo, from What My Bones Know: Healing From Complex Trauma

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is it fun to be frightened?

by Margee Kerr

Visiting an extreme haunted house can be delightfully terrifying. AP Photo/John Minchillo

John Carpenter’s iconic horror film “Halloween” celebrates its 40th anniversary this year. Few horror movies have achieved similar notoriety, and it’s credited with kicking off the steady stream of slasher flicks that followed.

Audiences flocked to theaters to witness the seemingly random murder and mayhem a masked man brought to a small suburban town, reminding them that picket fences and manicured lawns cannot protect us from the unjust, the unknown or the uncertainty that awaits us all in both life and death. The film offers no justice for the victims in the end, no rebalancing of good and evil.

Why, then, would anyone want to spend their time and money to watch such macabre scenes filled with depressing reminders of just how unfair and scary our world can be?

I’ve spent the past 10 years investigating just this question, finding the typical answer of “Because I like it! It’s fun!” incredibly unsatisfying. I’ve long been convinced there’s more to it than the “natural high” or adrenaline rush many describe – and indeed, the body does kick into “go” mode when you’re startled or scared, amping up not only adrenaline but a multitude of chemicals that ensure your body is fueled and ready to respond. This “fight or flight” response to threat has helped keep humans alive for millennia.

That still doesn’t explain why people would want to intentionally scare themselves, though. As a sociologist, I’ve kept asking “But, why?” After two years collecting data in a haunted attraction with my colleague Greg Siegle, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Pittsburgh, we’ve found the gains from thrills and chills can go further than the natural high.

Around Halloween, some people love to head to haunted attractions like this one in an old Cincinnati schoolhouse. AP Photo/John Minchillo

Studying fear at a terrifying attraction

To capture in real time what makes fear fun, what motivates people to pay to be scared out of their skin and what they experience when engaging with this material, we needed to gather data in the field. In this case, that meant setting up a mobile lab in the basement of an extreme haunted attraction outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

This adults-only extreme attraction went beyond the typical startling lights and sounds and animated characters found in a family-friendly haunted house. Over the course of about 35 minutes, visitors experienced a series of intense scenarios where, in addition to unsettling characters and special effects, they were touched by the actors, restrained and exposed to electricity. It was not for the faint of heart.

For our study, we recruited 262 guests who had already purchased tickets. Before they entered the attraction, each completed a survey about their expectations and how they were feeling. We had them answer questions again about how they were feeling once they had gone through the attraction.

We also used mobile EEG technology to compare 100 participants’ brainwave activity as they sat through 15 minutes of various cognitive and emotional tasks before and after the attraction.

Guests reported significantly higher mood, and felt less anxious and tired, directly after their trip through the haunted attraction. The more terrifying the better: Feeling happy afterward was related to rating the experience as highly intense and scary. This set of volunteers also reported feeling that they’d challenged their personal fears and learned about themselves.

Analysis of the EEG data revealed widespread decreases in brain reactivity from before to after among those whose mood improved. In other words, highly intense and scary activities – at least in a controlled environment like this haunted attraction – may “shut down” the brain to an extent, and that in turn is associated with feeling better. Studies of those who practice mindfulness meditation have made a similar observation.

Coming out stronger on the other side

Together our findings suggest that going through an extreme haunted attraction provides gains similar to choosing to run a 5K race or tackling a difficult climbing wall. There’s a sense of uncertainty, physical exertion, a challenge to push yourself – and eventually achievement when it’s over and done with.

Fun-scary experiences could serve as an in-the-moment recalibration of what registers as stressful and even provide a kind of confidence boost. After watching a scary movie or going through a haunted attraction, maybe everything else seems like no big deal in comparison. You rationally understand that the actors in a haunted house aren’t real, but when you suspend your disbelief and allow yourself to become immersed in the experience, the fear certainly can feel real, as does the satisfaction and sense of accomplishment when you make it through. As I experienced myself after all kinds of scary adventures in Japan, Colombia and all over the U.S., confronting a horde of zombies can actually make you feel pretty invincible.

Movies like “Halloween” allow people to tackle the big, existential fears we all have, like why bad things happen without reason, through the protective frame of entertainment. Choosing to do fun, scary activities may also serve as a way to practice being scared, building greater self-knowledge and resilience, similar to rough-and-tumble play. It’s an opportunity to engage with fear on your own terms, in environments where you can push your boundaries, safely. Because you’re not in real danger, and thus not occupied with survival, you can choose to observe your reactions and how your body changes, gaining greater insight to yourself.

Friends stuck together in a ‘Gates of Hell’ haunted house. AP Photo/John Locher

What it takes to be safely scared

While there are countless differences in the nature, content, intensity and overall quality of haunted attractions, horror movies and other forms of scary entertainment, they all share a few critical components that help pave the way for a fun scary time.

First and foremost, you have to make the choice to engage – don’t drag your best friend with you unless she is also on board. But do try to gather some friends when you’re ready. When you engage in activities with other people, even just watching a movie, your own emotional experience is intensified. Doing intense, exciting and thrilling things together can make them more fun and help create rewarding social bonds. Emotions can be contagious, so when you see your friend scream and laugh, you may feel compelled to do the same.

No matter the potential benefits, horror movies and scary entertainment are not for everyone, and that’s OK. While the fight-or-flight response is universal, there are important differences between individuals – for example, in genetic expressions, environment and personal history – that help explain why some loathe and others love thrills and chills.

Regardless of your taste (or distaste) for all things horror or thrill-related, an adventurous and curious mindset can benefit everyone. After all, we’re the descendants of those who were adventurous and curious enough to explore the new and novel, but also quick and smart enough to run or fight when danger appeared. This Halloween, maybe challenge yourself to at least one fun scary experience and prepare to unleash your inner superhero.

About The Author:

Margee Kerr is an Adjunct Professor of Sociology at the University of Pittsburgh.

This article is republished from our content partners, The Conversation, under a Creative Commons license.

#psychology#sociology#halloween#movies#haloween movies#also horror#fear#adrenaline#horror movies#scary movies

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chef’s choice: Walt Siegl Builds The Ducati Leggero His Way

Chef’s choice: Walt Siegl Builds The Ducati Leggero His Way

Walt Siegl has built everything from 50s era Harley panheads to modern KTM enduros. But if there’s one thing his New Hampshire-based shop is known for over anything else, it’s custom Ducatis. Specifically, his vintage-inspired Ducati Leggero builds. Ducati Leggeros are emblematic to the Walt Siegl Motorcycles brand. They are equal parts form and function, design and execution, modern performance…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Thanksgiving Stories

When I was 16 or so I started writing a comic about Thanksgiving with my family. The premise was that a technology had been developed that could turn Alzheimer’s patients into healthy, thriving...plants; and that my grandfather had signed my grandmother up for this cutting-edge treatment. I still think it’s a good story, tbh. Maybe someday I’ll finish it. I struggled with representing my family members. It feels likely that my grandfather was a bit indescribable, and now that he’s gone I can never get a new second opinion. I felt his death less like the loss of a person and more like the destruction of an edifice. At his funeral, his family members spoke about him with difficulty; his casual cruelty, his brilliance, his rare and glorious moments of warmth. The staff at his nursing home chastised us; he had been, to them, a figure of good humour and radiant love. That’s always how it is; we save our worst shit for the people we’re closest to.

Peter E. Siegle died on Christmas; early in the morning, December 25th, 2010. My aunt and I spent Christmas Eve with him, waiting while he died slowly, but neither of us were there when it happened, appropriate to his dignity. However, we both came back the next morning, both accompanied by nervous new boyfriends. (My guy was an absolute trooper and even though we broke up we’re still good friends; we frustrate each other but he never made me less than I am.) Rachel’s man she later married, and I can’t help it, my mistrust of him began this Christmas morning; when they rolled my grandfather’s body out of his room, covered by a sheet, he tried to make us look away. We said no, he tried to insist. I was furious inside. My aunt is one of the strongest people I know, and in my eyes, this man, trying to be gentle, believing she needed protection, was treating her as if she was weak. We watched with our eyes goddamn open, thank you. But she married him anyway. And I like him now, I really do. Certain things aside. But now Thanksgiving happens in Rachel and Pete’s world, up in New Hampshire, in a big new house with Pete’s big family and no one ever argues and Pete is relentlessly affable and fusses over everyone because he wants everyone to be comfortable at his house. It’s...nice. There is absolutely nothing wrong with it. It’s just not mine and I can’t get past this feeling that it isn’t right.

Thanksgiving with my family in my grandfather’s series of boston apartments used to be a battle of wits. The conversation was high level, and if I’m being totally honest, it was more than a little snobbish. There were arguments about ideas. When I was a kid it often exploded into a shouting match between my grandfather and my dad, but as I got older everyeone mellowed just enough, and we found a way of making it work. It was stressful, at times it was fucking awful, but it was mine. It’s supposed to be like this: my grandfather and my dad arguing and both popping into the kitchen occasionally where my aunt and me are listening to Alice’s Restaurant and peeling sweet potatoes hot from being pre-baked and then my grandfather’s friends show up at dinner time and everyone eats chopped liver on crackers and talks politics and drinks wine. Everyone knows that there are going to be disagreements and arguments, that there’s going to be some discomfort, in fact, because that’s just how my grandfather is, and that’s how things are in his company; he’s tough and smart but not without his own weird brand of kindness, and he insisted that the people around him get on his level. My family, in kind, wasn’t nice. They were brutal, honest, to the point, intellectual. I didn’t always enjoy that. There was a lot missing from our interactions, we’re often bad, as a clan, at seeming to care, and when I was younger that bugged me. It wasn’t Norman Rockwell, and when I was a kid i kind of wanted everything to be that way, cuddly and warm; and now I miss my hard-edged family more than anything in the world.

I miss avidly following a discourse from person to person, and my dad or my aunt catching my eye to make me know they haven’t forgotten about me. That’s how it’s supposed to be. A yearly reminder of who we are, heading into the winter: we grapple with the tough questions, we don’t look away. That I’m not alone in being this kind of person, whatever that means. Family was a touchstone. That’s what this holiday was for. Loss of family transfers responisbilities; I don’t have a lot of the people who re-affirmed my sense of self in my life anymore. So I have to carry that flag for myself, and ...so that if someone else needs to find that reassurance, they can find it in me. We become adults in this way when our own grown-ups die, whether we like it or not, whether we’re ready or not; the responsibility sits there waiting for you silently until you’re ready to pick it up. It’s been tough to offer gratitude during this holiday-time for the last few years, because I bitterly resent what I have lost, and I wasn’t ready to move forward from that point yet. And that sucks, because gratitude is kind of my thing. But maybe now that I’ve written it out I can start dealing with this event for what it is now, not what it used to be.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The True Cost of Fast Fashion

By Kayla Fragman.

I stepped into a mall for the first time in two years.

Prices written in bold through the windows screamed for my attention, a sale found at every step, brands in bold, I stare at it all in amazement. The past two years have been spent changing my style between the racks of clothes at Value Village, the unworn items of my parents’ past, my grandmother’s dusty jewelry or the bold colours of a vintage shop. Finding my inspiration online or through the eyes of the city, I forgot what the inside of a shopping mall even looked like. People around me in a motion, in and out, bags weighing each of them down. We buy from brands without knowing the consequences of it all.

There is a hidden side to the industry not many seem to realize or care for. After informing myself about the mistreated and underpaid workers or the environmental impacts of buying from popular brands, I quickly changed my unethical ways. I first watched The True Cost, a documentary on Netflix about the detrimental impacts of fast fashion, after my friend recommended it to me. The film explores every aspect of the industry, from producer to consumer, without trying to sugarcoat anything. Workers in developing countries are payed horribly low salaries, barely able to provide for their families. Some are physically abused by their bosses and their suicide rates have gone up drastically.

The documentary claims that in 1960, the American Fashion Industry produced 95% of the clothes worn by Americans. Now, only 3% of clothes are produced in the United States while the rest is made in developing countries. The movie also attempts to show the consumeristic lifestyle that we have been accustomed to. Commercials, social media, ads online, we are constantly reminded of the newest trends. Often, as soon as our teenage years approach, we feel the pressure to buy from popular stores and keep up with what everyone else is wearing. The thought of the origins of that piece of fabric, where those clothes come from or who made them does not even cross our minds.

Lucy Siegle’s book To Die For has helped many realize the ethical issues of the fashion industry and inspired the producers of the documentary. When asked in an interview if sustainable fashion is even a real possibility, she explained that there are solutions to creating clothes that are not detrimental to the environment and to the lives of workers. “Fashion has been co-opted by turbo charged capitalist corporations who are kicking the shit out of it and stripping fashion of its culture.” The essence of the problem are the big brands that refuse to change their ways and follow innovative solutions to help make their brand more ethical.

I followed up by reading several articles about fast fashion online and came to the conclusion that I was never to buy from an unethical brand again. I found new joys in spending hours searching for treasures in the endless rows of thrift shops or supporting ethical brands made in my own country or city. Simple steps such as buying from local shops or signing petitions for fast fashion brands to pay their workers reasonable salaries can go a long way. Ethical consciousness can start with something as simple as your own wardrobe. With the benefits of an original style and environmental consciousness, why continue to support fast fashion?

#fast fashion#the true cost documentary#garment industry#sweatshops#thrift shops#brand ethics#fashion#fashion industry#clothing#awareness#amaize mag#kayla fragman

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sun Catchers: Art or Kitsch?

My newest acquisition is this lovely sun catcher. I picked it up at The Trove in Old Saybrook, Connecticut. Serendipity led me to its discovery as I almost overlooked it. While checking out of the store, I finally looked up and there it was, hanging in the window. I was told it was made by a late, local artisan. If you recognize the work, please let me know who made it.

Signed 1980 ©Glassmasters

The Owl and the Pussycat I had never been attracted to sun catchers until my sister sent this one to my young children back in the 1980s. We spent many a morning reciting the beginning of Edward Lear's poem (The Owl and the Pussycat went to sea in a beautiful pea green boat...) I had thought of sun catchers as Disney memorabilia or holiday decor, a stained glass Santa Claus or a Thanksgiving Turkey.

The above was made by Glassmasters based in Macomb Township, Michigan and is dated 1980.

I should have known better. I was schooled in stained glass by my tenth grade history teacher when we studied art from the middle ages. But I saw those beautiful windows as art and sun catchers as kitsch.

And then, when I was getting married in 1975, my dear friend and boss Fred R. Siegle (The Profile Press) and his wife Else offered me a choice of a wedding gift between two objects. One was a piece of stone carving from a lintel or doorway and the other was the roundel above. I took the roundel. I was surprised when I visited The Cloisters to see similar roundels displayed in the windows.

New York Cloisters 33 010 Glass Gallery - Roundel Window, Turkish Soldier and Wild Man, Justice, Descent of the Damned

And finally, my garden ornament that hangs in my bedroom window.

None of these are offered for sale in my shop but I am looking for more and will add them to my inventory when and if I find more.

#sun catcher#stained glass#vintage memorabilia#vintage souvenirs#collectibles#garden ornaments#window art#glassmasters#roundel#rondel#profile press#Fred R Siegle#Else Siegle#susan McCaslin#isearchedandfound

0 notes

Text

This is Fashion Sustainability

Sustainability by definition is not a trend. Ironically it is pretty simple, and yet a not so simple concept. Sustainability is a balance between the community, the planet, and the economy.

There are many factors to manage when working within sustainability. You have ethical fashion, cruelty-free fashion, practical fashion, minimalistic fashion, style over fashion, vegan fashion and even gluten free jeans. The industry does not know what end is up, let alone anyone else.

Balancing between the economy, the planet, and human rights.

Sustainable fashion is all about creating an equalise. If you focus too much on one factor more than the others this is not being sustainable.

Society as a whole has been focused entirely on economic incentives. This has naturally been a disaster because it oppresses people and exploits our planet’s resources.

There is no singular solution to solving the world’s problems, and no one individual can do it alone. It will take a society-wide effort to fix these problems. It just takes time, effort, and dedication to something greater than monetary gains. Sustainability and sustainable fashion will happen in due time.

Maintaining profit incentive without exploiting workers and communities.

“Fast fashion isn’t free. Someone, somewhere is paying.” Lucy Siegle, Fashion Revolution.

Sustainable fashion is just another commodity if you think of it from a business point of view. People see value in fashion. They buy it, use it and sell it. Repeat cycle.

We will always need clothing. Our expression of ourselves is tied to our ego, and our egos absolutely love pretty things. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. Fashion isn’t going anywhere and sustainable fashion is here to at least help reduce our impact.

We all hear about garment factories in foreign countries- fires, exploitation of child labour, underpaid employees etc. Nothing seems to get better in the world of mass-market clothing. We hear stories about Ivanka Trump’s clothing line being exposed for being linked to manufactures that harm the rights of workers, and Beyoncé’s under treated employees behind the creation of her Ivy Park collection. There are news stories summarising atrocities, without giving any suggestions on how to fix it. It doesn’t seem to get any better.

And yet, on the other hand, we hear about how people like Emma Watson insisted on fair-wage workers to produce clothing for the beauty and the beast movie. There is hope. There are inspiring stories. It’s out there. We just have to find it, and we should support fair wages when we can.

We can’t shop our way out of climate change, but we can’t do nothing either.

Even if we were each able to perfectly choose the right products that “help the environment” we still wouldn’t be doing much of a dent on fixing them because these big problems require collective action. This is not something we can buy ourselves out of.

Except for that way of thinking is also a little bit flawed.

We can’t just do nothing and hope that the collective action will somehow save us. The demand shifts when we buy different products. Therefore, if you are able to reduce your pollution, and use a product that is mildly more helpful for the environment, over time, the markets will shift to produce better products.

By shifting trends over time, sustainable fashion has a chance at making a major impact on how we view and purchase clothing.

0 notes

Text

LiCheng Flat Screen Printing Machine

LiCheng Flat Screen Printer are widely used in various printing industries to provide fine and smooth prints. Features of the Flat Screen Printing Machine : Its appearance is stylish and beautiful, adopted soft platen with customizable length and quantity of colors. Information of Flat Screen Printing Machine : Model:F1 Printing width:1900mm-3200mm Printing repeat range:400-3200mm Printing color quantities:8-16 LiCheng flat screen printing machine are designed and manufactured with optimum precision using optimum grade components and ultra-modern technology to meet the set industrial standards. ◆All electric components are from Mitsubishi, Omron, Yaskawa, Schneider, etc. ◆All pneumatic components are from the Japanese brand of SMC ◆Reinforced printing blanket is from the German brand of Siegling ◆Main drive reducer of blanket is from the German brand of SEW ◆Lifting driving screw is from the Japanese brand of THK Custom products are our main products. We can develop and manufacture products according to customer's drawing or sample. We have our own foreign trade department, we market our own products. We're so glad that you tell us your special requirement or find out more, please feel free to contact us by click https://ift.tt/2UNnTNb source https://unme.us/for-sale/everything-else/licheng-flat-screen-printing-machine_i1338

0 notes

Text

Top 7 Ways to Support Sustainable Fashion

dailymotion

30 Tips in 30 Days Designed to Help You Take Control of Your Health

This article is included in Dr. Mercola's All-Time Top 30 Health Tips series. Every day during the month of January, a new tip will be added that will help you take control of your health. Want to see the full list? Click here.

Shopping is often referred to as "retail therapy." Some suggest buying stuff, especially new clothes, can make you feel better - more relaxed, perhaps, or prettier or popular. While shopping for the latest trendy fashions may boost your mood temporarily, most people agree the positive vibes seldom last long.

Even if they did, there is more to modern fashion than meets the eye. Underneath all the glitz and glam portrayed in store windows are layers of what a new BBC documentary refers to as "fashion's dirty secrets."

If you think turning over your wardrobe frequently has little impact on world events, you may want to take an hour to watch the film. From start to finish, it will compel you to seriously consider how the fashion industry is actually wreaking havoc on the environment and endangering human health.

BBC Reporter Suggests Our Clothes Are Wrecking the Planet

In the featured 2018 documentary, BBC investigative reporter Stacey Dooley unearths some of the fashion industry's "dirty secrets."1 Her conclusion: Our clothes are wrecking the planet. At the onset of the film, Dooley is quick to admit she is a fan of fashion.

"It's retail therapy," she says. "For me, shopping is a way to unwind. I buy a treat, and I get home, try it on and take loads of photos wearing it." Like many, she puts the clothes on, poses in front of a full-length mirror and uses her smartphone to snap a bunch of photos. Later, she posts her favorite pictures on social media, which attracts a flurry of comments from friends and followers.

Dooley notes how easy it is to get pulled into a relatively new trend called "fast fashion," which alludes to how designers and retailers introduce new collections on a weekly basis to keep consumers hooked on clothing. Because clothing lines turn over rapidly, buyers often feel pressure to keep pace with the latest trends, even when they already have a closet full of perfectly useable clothing.

"Fast fashion lures us into buying more clothes than we need," asserts Lucy Siegle, a journalist and author specializing in environmental issues and one of Dooley's interviewees in the documentary. "It's a production system that brings us clothes at intense volume." The problem is our insatiable demand for cheap copies of catwalk fashion is having a devastating impact on the environment.

Like Dooley, you may be surprised to learn that fashion is second only to oil on the list of the top five most polluting industries in the world. That revelation took Dooley on a global adventure to further investigate the impact fashion has on vital aspects of living such as air quality, the economy, human health and water supplies.

Nonorganic Cotton Is One of the Worst Offenders of the Environment

Nonorganic cotton is one of the fibers Dooley reveals as doing the most harm to the environment, particularly as it relates to its devastating impact on fresh water supplies.

Finding out that cotton is one of the "bad guys" may surprise you, especially if you have been influenced by the U.S. industry group advertising that, for nearly 50 years, has promoted conventionally grown cotton as the "fabric of our lives."2 Dooley notes some of the "dirty secrets" associated with nonorganic cotton include the:

Pesticides used in cotton farming

Dyes and other chemicals used in manufacturing items made from cotton

Immense amounts of water needed to produce and process it

In the film, Dooley is told it can take upward of 15,000 liters (about 4,000 gallons) of water to grow the cotton necessary to make some brands of jeans. "I've never associated clothes production with pollution before," she said.

Vital Waterways Damaged by Cotton Production and Textile Manufacturing

In addition to being chemical-dependent, conventionally produced cotton also needs water - lots of water. Dooley discovered the amount of water needed in some cases is enough to nearly drain a sea in a few decades. On a visit to Kazakhstan, Dooley heard firsthand about how the water level of the Aral Sea began receding in the early 1970s.

The Aral Sea is situated between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan - the world's sixth-largest cotton producer among 90 cotton-growing countries.3 At the time cotton began making inroads, fish started dying from the chemical runoff from cotton fields. Now, in an area that used to be covered in turquoise blue water, you find a sparsely populated, barren wasteland.

The Amu Darya, one of the rivers that fed the Aral, was diverted into cotton-production farms in Uzbekistan and sucked dry before it could reach the sea. In Kazakhstan, what used to be a thriving seaport is now nearly 80 kilometers (50 miles) from the water's edge. The country's fishing industry has been obliterated by its neighbor's cotton industry.

Sadly, the former Kazakhstani seabed is heavily contaminated with pesticides, which prevents plant growth. Locals say wind-driven toxic dust has led to high rates of cancer, tuberculosis and other illnesses among those eking out a living there. The negative impact of cotton is felt daily in the local economy, public health and weather.

"You don't understand the enormity of the situation until you're here," asserts Dooley, standing on the dry earth that was once the Aral seabed. Camels and horses roam in an area once teeming with fish and other sea life. "[D]id I know cotton was capable of this? Of course, I didn't. I had no idea."

Beyond cotton, textile manufacturers themselves also misuse water resources. Dooley visited Indonesia to get a firsthand look at the Citarum River, known as the world's most polluted river. The area around the Citarum is home to more than 400 factories thought to be releasing toxic chemicals into waterways across the region on a daily basis.

Touring the river by raft, Dooley observed several hues of colored dye being pumped into the water and well as bubbling, bad-smelling foam. Toxicology results indicated the river is heavily polluted by heavy metals, including arsenic, cadmium, lead and mercury, which damages the health of local residents who depend on the river for drinking water as well as for bathing and washing clothes.

"To me, this feels like a complete catastrophe, and it's worth bearing in mind that Indonesia isn't even in the top five garment manufacturing countries globally," Dooley commented.

Sustainability: A Real Issue That Needs To Be Addressed in the Fashion Industry

In the U.S. alone, the impact of fashion has been outlined as follows. Every year:4

13.1 million tons of textile waste are created

11 million tons of textile waste end up in landfills

68 percent of the water used to create one pair of jeans revolves around fiber production alone

Because sustainability is such a huge issue for the textile industry, as part of her investigation, Dooley attended the Copenhagen Fashion Summit - a gathering billed as "the world's leading business event on sustainability in fashion." Unfortunately, not many of the clothing brands participating in the event were willing to speak to Dooley on camera.

As such, she stated, "This summit is a sign that some in this industry are working to clean up fashion, but I have felt the brands' refusal to talk to me make it look like some of them have something to hide."

That said, Dooley was able to speak to Paul Dillinger, vice president of global product innovation for Levi Strauss & Co., the $5-billion American brand that produces denim jeans and jackets and other clothing. "We're working on a solution that takes old garments, chemically deconstructs them and turns them into a new fiber that feels and looks like cotton, but with zero water impact," he said.

Beyond that, Dillinger says, "In the meantime, we are doing everything we can to use less water in our finishing. We share information on how to reduce the water footprint of our cotton with everyone else." While all that sounds great, he and Dooley agreed the industry and consumers are not yet ready for large-scale change.

"This is a big industry. It's so broadly decentralized that affecting change is nearly impossible," Dillinger notes, "especially when the [consumer] appetite doesn't want change. For that reason, there will need to be a regulatory solution. It has to happen, because there just isn't enough water."

The only lasting solution it seems is for the fashion brands to invest themselves in environmentally friendly production methods. Those new methods, Dooley notes, must run in a parallel path alongside government oversight.

This would include laws and regulations designed to place limitations on water usage, while closely monitoring and responding to other negative environmental impacts brought about by textile companies.

Discarded Clothing Also Has Huge Environmental Impacts

While it may seem the number of textiles discarded are not important, as most fabric should be biodegradable, the reality is the large amount of clothing thrown away every day contains more than cotton. Procedures to treat clothing include using specialized chemicals, such as biocides, flame retardants and water repellents.5

More than 60 different chemical classes are used in the production of yarn, fabric pretreatments and finishing. When fabrics are manufactured, between 10 and 100 percent of the weight of the fabric is added in chemicals.6 Even fabrics made from 100 percent cotton are coated with 27 percent of its weight in chemicals.

Most fabrics are treated with liquid chemicals to ready them for the fashion industry, going through several treatments before being shipped to a manufacturer. A number of chemicals used on clothing are known to present human health and environmental issues.

Greenpeace International7 commissioned an investigation into the toxic chemicals used in clothing. They purchased 141 different pieces of clothing in 29 different countries. The items were manufactured in 18 countries. The chemicals found included high levels of phthalates and cancer-causing amines.

The investigators also found 89 garments with nonylphenol ethoxylates (NPEs). Twenty percent of the garment reflected levels above 100 parts per million (ppm), whereas 12 of the samples contained levels above 1,000 ppm. Because any level of phthalates, amines or NPEs are considered to be hazardous, you do not want them coming into contact with your body through clothing.

While you may think the potential danger of these chemicals comes from wearing clothing containing them, that is just one step in the cycle of harm. When the material makes it to a landfill, these toxic chemicals can leach out into the groundwater. Perfluorinated chemicals (PFCs) have been widely used in textile marketing and have been linked to a variety of health problems in humans.8

PFCs are so ubiquitous they've been found in the blood of polar bears9 and in tap water supplies used by 15 million Americans in 27 states.10 Fortunately, Greenpeace has listed PFCs as one of the hazardous chemicals used in clothing production targeted for elimination by 2020.11 So far, progress has been slow.

"It fills me with dread," says Dooley. "It's hard to think that the clothes I'm wearing could do so much damage, but I now see how the industry is such a threat to the planet."

youtube

The Care What You Wear Campaign

We simply have to start caring about what went into the clothes we wear, which is why I'm participating and donating proceeds from my Dirt Shirts to the Care What You Wear campaign. Marci explains the incentive behind the campaign thus:

"We want to empower consumers and businesses to care about what's behind the way it looks. It's not just about looking good in clothing. It's about feeling good and doing good in the world. When you think about caring about what you're wearing, it's about going deeper and saying, 'Where did this apparel come from? How is it being grown? Where is it being made? Who's making it?'

It's not that different from the Farm to Table Movement, where people are saying, 'Where is my food coming from? How is it being grown and produced?' It's the same thing.

We're waking up to our source inside. We're awakening to that desire to know what we're putting in and on our bodies as an extension of ourselves. It's not just what you eat. It's also what you wear that is a part of you. We need to be thinking about fiber no differently than we are about food."

Startups Are Changing the Industry From the Ground Up

Though not explicitly mentioned in the documentary, one of Levi Strauss' big moves in terms of sustainability involves its partnership with a Seattle-based textile startup called Evrnu.12 In 2016, the two created the world's first jeans made from the reclaimed fibers of five recycled cotton T-shirts. This renewable fiber uses substantially less water than the traditional cotton process.

Such a change is significant considering the Evrnu team notes it takes a staggering 20,000 liters (about 5,300 gallons) of water to produce the amount of cotton needed to make a single pair of jeans. After discovering it takes 700 gallons of fresh clean water to make a simple cotton shirt, Evrnu founder Stacy Flynn recognized the need for sustainability.

Determined to find a way to combat such waste, Flynn launched Evrnu as a startup. By 2014, Flynn and her team had created a new, sustainable alternative from recycled clothing.

Although the full impact of companies like Evrnu are yet to be seen, Flynn says, "It shows that even big players in the textile industry are open to change for the good of the environment, as well as willing to seek out and find the new eco-friendly solutions that are emerging."13

About the new product, Dillinger said, "This first prototype represents a major advancement in apparel innovation. We have the potential to reduce by 98 percent the water that would otherwise be needed to grow virgin cotton."14

7 Ways You Can Help Reduce the Negative Impact of Fashion

Given Dooley's passionate call to action, you may want to consider how you can help reduce the negative impact of fashion. For one, as a consumer, you can vote with your purchases - buying sustainable brands and avoiding companies and clothing items you know are damaging the environment. Beyond that, you can:

1. Choose fabrics made with organic cotton, hemp, silk, wool and bamboo; learn more by reading my article "Why Opting for Organic Cotton Matters"

2. Resist the pull of "fast fashion" and only buy clothes you can commit to wearing for a long time

3. Trade clothes among your family and friends, especially items that have been hanging in your closet unworn for more than six months

4. Select items colored with nontoxic, natural dyes

5. Avoid screen printed items because they typically contain phthalates

6. Be mindful of when and how you wash synthetic clothing so as to minimize the shedding of microfibers

7. Keep in mind that most donated clothing actually ends up in landfills

While in Indonesia, Dooley spoke with Ade Sudrajat, chairman of the Indonesian Textile Association (API), who said, "I feel ill. The situation I face makes me desperate." Without better regulation and oversight from government, Sudrajat says, "The planet is gone. Water is our life. Water is our future."

Though she has investigated environmental issues before, Dooley says she was marked by the enormity of the problems going on inside the fashion industry, which she claims have become "a tremendous threat to the planet."

"For me to tell you that I'm never going to shop again would be completely dishonest," she concludes. "But I do recognize how powerful I am as a consumer. This is a situation that needs addressing - and fast. There has to be a real sense of urgency now because to be totally honest with you, we're running out of time."

Tip #11Grow Your Own Food

0 notes

Text

Top 7 Ways to Support Sustainable Fashion

30 Tips in 30 Days Designed to Help You Take Control of Your Health

This article is included in Dr. Mercola's All-Time Top 30 Health Tips series. Every day during the month of January, a new tip will be added that will help you take control of your health. Want to see the full list? Click here.

Shopping is often referred to as "retail therapy." Some suggest buying stuff, especially new clothes, can make you feel better — more relaxed, perhaps, or prettier or popular. While shopping for the latest trendy fashions may boost your mood temporarily, most people agree the positive vibes seldom last long.

Even if they did, there is more to modern fashion than meets the eye. Underneath all the glitz and glam portrayed in store windows are layers of what a new BBC documentary refers to as "fashion's dirty secrets."

If you think turning over your wardrobe frequently has little impact on world events, you may want to take an hour to watch the film. From start to finish, it will compel you to seriously consider how the fashion industry is actually wreaking havoc on the environment and endangering human health.

BBC Reporter Suggests Our Clothes Are Wrecking the Planet

In the featured 2018 documentary, BBC investigative reporter Stacey Dooley unearths some of the fashion industry's "dirty secrets."1 Her conclusion: Our clothes are wrecking the planet. At the onset of the film, Dooley is quick to admit she is a fan of fashion.

"It's retail therapy," she says. "For me, shopping is a way to unwind. I buy a treat, and I get home, try it on and take loads of photos wearing it." Like many, she puts the clothes on, poses in front of a full-length mirror and uses her smartphone to snap a bunch of photos. Later, she posts her favorite pictures on social media, which attracts a flurry of comments from friends and followers.

Dooley notes how easy it is to get pulled into a relatively new trend called "fast fashion," which alludes to how designers and retailers introduce new collections on a weekly basis to keep consumers hooked on clothing. Because clothing lines turn over rapidly, buyers often feel pressure to keep pace with the latest trends, even when they already have a closet full of perfectly useable clothing.

"Fast fashion lures us into buying more clothes than we need," asserts Lucy Siegle, a journalist and author specializing in environmental issues and one of Dooley's interviewees in the documentary. "It's a production system that brings us clothes at intense volume." The problem is our insatiable demand for cheap copies of catwalk fashion is having a devastating impact on the environment.

Like Dooley, you may be surprised to learn that fashion is second only to oil on the list of the top five most polluting industries in the world. That revelation took Dooley on a global adventure to further investigate the impact fashion has on vital aspects of living such as air quality, the economy, human health and water supplies.

Nonorganic Cotton Is One of the Worst Offenders of the Environment

Nonorganic cotton is one of the fibers Dooley reveals as doing the most harm to the environment, particularly as it relates to its devastating impact on fresh water supplies.

Finding out that cotton is one of the "bad guys" may surprise you, especially if you have been influenced by the U.S. industry group advertising that, for nearly 50 years, has promoted conventionally grown cotton as the "fabric of our lives."2 Dooley notes some of the "dirty secrets" associated with nonorganic cotton include the:

Pesticides used in cotton farming

Dyes and other chemicals used in manufacturing items made from cotton

Immense amounts of water needed to produce and process it

In the film, Dooley is told it can take upward of 15,000 liters (about 4,000 gallons) of water to grow the cotton necessary to make some brands of jeans. "I've never associated clothes production with pollution before," she said.

Vital Waterways Damaged by Cotton Production and Textile Manufacturing

In addition to being chemical-dependent, conventionally produced cotton also needs water — lots of water. Dooley discovered the amount of water needed in some cases is enough to nearly drain a sea in a few decades. On a visit to Kazakhstan, Dooley heard firsthand about how the water level of the Aral Sea began receding in the early 1970s.

The Aral Sea is situated between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan — the world's sixth-largest cotton producer among 90 cotton-growing countries.3 At the time cotton began making inroads, fish started dying from the chemical runoff from cotton fields. Now, in an area that used to be covered in turquoise blue water, you find a sparsely populated, barren wasteland.

The Amu Darya, one of the rivers that fed the Aral, was diverted into cotton-production farms in Uzbekistan and sucked dry before it could reach the sea. In Kazakhstan, what used to be a thriving seaport is now nearly 80 kilometers (50 miles) from the water's edge. The country's fishing industry has been obliterated by its neighbor's cotton industry.

Sadly, the former Kazakhstani seabed is heavily contaminated with pesticides, which prevents plant growth. Locals say wind-driven toxic dust has led to high rates of cancer, tuberculosis and other illnesses among those eking out a living there. The negative impact of cotton is felt daily in the local economy, public health and weather.

"You don't understand the enormity of the situation until you're here," asserts Dooley, standing on the dry earth that was once the Aral seabed. Camels and horses roam in an area once teeming with fish and other sea life. "[D]id I know cotton was capable of this? Of course, I didn't. I had no idea."

Beyond cotton, textile manufacturers themselves also misuse water resources. Dooley visited Indonesia to get a firsthand look at the Citarum River, known as the world's most polluted river. The area around the Citarum is home to more than 400 factories thought to be releasing toxic chemicals into waterways across the region on a daily basis.

Touring the river by raft, Dooley observed several hues of colored dye being pumped into the water and well as bubbling, bad-smelling foam. Toxicology results indicated the river is heavily polluted by heavy metals, including arsenic, cadmium, lead and mercury, which damages the health of local residents who depend on the river for drinking water as well as for bathing and washing clothes.

"To me, this feels like a complete catastrophe, and it's worth bearing in mind that Indonesia isn't even in the top five garment manufacturing countries globally," Dooley commented.

Sustainability: A Real Issue That Needs To Be Addressed in the Fashion Industry

In the U.S. alone, the impact of fashion has been outlined as follows. Every year:4

13.1 million tons of textile waste are created

11 million tons of textile waste end up in landfills

68 percent of the water used to create one pair of jeans revolves around fiber production alone

Because sustainability is such a huge issue for the textile industry, as part of her investigation, Dooley attended the Copenhagen Fashion Summit — a gathering billed as "the world's leading business event on sustainability in fashion." Unfortunately, not many of the clothing brands participating in the event were willing to speak to Dooley on camera.

As such, she stated, "This summit is a sign that some in this industry are working to clean up fashion, but I have felt the brands' refusal to talk to me make it look like some of them have something to hide."

That said, Dooley was able to speak to Paul Dillinger, vice president of global product innovation for Levi Strauss & Co., the $5-billion American brand that produces denim jeans and jackets and other clothing. "We're working on a solution that takes old garments, chemically deconstructs them and turns them into a new fiber that feels and looks like cotton, but with zero water impact," he said.

Beyond that, Dillinger says, "In the meantime, we are doing everything we can to use less water in our finishing. We share information on how to reduce the water footprint of our cotton with everyone else." While all that sounds great, he and Dooley agreed the industry and consumers are not yet ready for large-scale change.

"This is a big industry. It's so broadly decentralized that affecting change is nearly impossible," Dillinger notes, "especially when the [consumer] appetite doesn't want change. For that reason, there will need to be a regulatory solution. It has to happen, because there just isn't enough water."

The only lasting solution it seems is for the fashion brands to invest themselves in environmentally friendly production methods. Those new methods, Dooley notes, must run in a parallel path alongside government oversight.

This would include laws and regulations designed to place limitations on water usage, while closely monitoring and responding to other negative environmental impacts brought about by textile companies.

Discarded Clothing Also Has Huge Environmental Impacts

While it may seem the number of textiles discarded are not important, as most fabric should be biodegradable, the reality is the large amount of clothing thrown away every day contains more than cotton. Procedures to treat clothing include using specialized chemicals, such as biocides, flame retardants and water repellents.5

More than 60 different chemical classes are used in the production of yarn, fabric pretreatments and finishing. When fabrics are manufactured, between 10 and 100 percent of the weight of the fabric is added in chemicals.6 Even fabrics made from 100 percent cotton are coated with 27 percent of its weight in chemicals.

Most fabrics are treated with liquid chemicals to ready them for the fashion industry, going through several treatments before being shipped to a manufacturer. A number of chemicals used on clothing are known to present human health and environmental issues.

Greenpeace International7 commissioned an investigation into the toxic chemicals used in clothing. They purchased 141 different pieces of clothing in 29 different countries. The items were manufactured in 18 countries. The chemicals found included high levels of phthalates and cancer-causing amines.

The investigators also found 89 garments with nonylphenol ethoxylates (NPEs). Twenty percent of the garment reflected levels above 100 parts per million (ppm), whereas 12 of the samples contained levels above 1,000 ppm. Because any level of phthalates, amines or NPEs are considered to be hazardous, you do not want them coming into contact with your body through clothing.

While you may think the potential danger of these chemicals comes from wearing clothing containing them, that is just one step in the cycle of harm. When the material makes it to a landfill, these toxic chemicals can leach out into the groundwater. Perfluorinated chemicals (PFCs) have been widely used in textile marketing and have been linked to a variety of health problems in humans.8

PFCs are so ubiquitous they've been found in the blood of polar bears9 and in tap water supplies used by 15 million Americans in 27 states.10 Fortunately, Greenpeace has listed PFCs as one of the hazardous chemicals used in clothing production targeted for elimination by 2020.11 So far, progress has been slow.

"It fills me with dread," says Dooley. "It's hard to think that the clothes I'm wearing could do so much damage, but I now see how the industry is such a threat to the planet."

The Care What You Wear Campaign

We simply have to start caring about what went into the clothes we wear, which is why I'm participating and donating proceeds from my Dirt Shirts to the Care What You Wear campaign. Marci explains the incentive behind the campaign thus:

"We want to empower consumers and businesses to care about what's behind the way it looks. It's not just about looking good in clothing. It's about feeling good and doing good in the world. When you think about caring about what you're wearing, it's about going deeper and saying, 'Where did this apparel come from? How is it being grown? Where is it being made? Who's making it?'

It's not that different from the Farm to Table Movement, where people are saying, 'Where is my food coming from? How is it being grown and produced?' It's the same thing.

We're waking up to our source inside. We're awakening to that desire to know what we're putting in and on our bodies as an extension of ourselves. It's not just what you eat. It's also what you wear that is a part of you. We need to be thinking about fiber no differently than we are about food."

Startups Are Changing the Industry From the Ground Up

Though not explicitly mentioned in the documentary, one of Levi Strauss' big moves in terms of sustainability involves its partnership with a Seattle-based textile startup called Evrnu.12 In 2016, the two created the world's first jeans made from the reclaimed fibers of five recycled cotton T-shirts. This renewable fiber uses substantially less water than the traditional cotton process.

Such a change is significant considering the Evrnu team notes it takes a staggering 20,000 liters (about 5,300 gallons) of water to produce the amount of cotton needed to make a single pair of jeans. After discovering it takes 700 gallons of fresh clean water to make a simple cotton shirt, Evrnu founder Stacy Flynn recognized the need for sustainability.

Determined to find a way to combat such waste, Flynn launched Evrnu as a startup. By 2014, Flynn and her team had created a new, sustainable alternative from recycled clothing.

Although the full impact of companies like Evrnu are yet to be seen, Flynn says, "It shows that even big players in the textile industry are open to change for the good of the environment, as well as willing to seek out and find the new eco-friendly solutions that are emerging."13

About the new product, Dillinger said, "This first prototype represents a major advancement in apparel innovation. We have the potential to reduce by 98 percent the water that would otherwise be needed to grow virgin cotton."14

7 Ways You Can Help Reduce the Negative Impact of Fashion

Given Dooley's passionate call to action, you may want to consider how you can help reduce the negative impact of fashion. For one, as a consumer, you can vote with your purchases — buying sustainable brands and avoiding companies and clothing items you know are damaging the environment. Beyond that, you can:

1. Choose fabrics made with organic cotton, hemp, silk, wool and bamboo; learn more by reading my article "Why Opting for Organic Cotton Matters"

2. Resist the pull of "fast fashion" and only buy clothes you can commit to wearing for a long time

3. Trade clothes among your family and friends, especially items that have been hanging in your closet unworn for more than six months

4. Select items colored with nontoxic, natural dyes

5. Avoid screen printed items because they typically contain phthalates

6. Be mindful of when and how you wash synthetic clothing so as to minimize the shedding of microfibers

7. Keep in mind that most donated clothing actually ends up in landfills

While in Indonesia, Dooley spoke with Ade Sudrajat, chairman of the Indonesian Textile Association (API), who said, "I feel ill. The situation I face makes me desperate." Without better regulation and oversight from government, Sudrajat says, "The planet is gone. Water is our life. Water is our future."

Though she has investigated environmental issues before, Dooley says she was marked by the enormity of the problems going on inside the fashion industry, which she claims have become "a tremendous threat to the planet."

"For me to tell you that I'm never going to shop again would be completely dishonest," she concludes. "But I do recognize how powerful I am as a consumer. This is a situation that needs addressing — and fast. There has to be a real sense of urgency now because to be totally honest with you, we're running out of time."

from http://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2019/01/12/fashion-industry-pollution.aspx

source http://niapurenaturecom.weebly.com/blog/top-7-ways-to-support-sustainable-fashion

0 notes

Text

A Cautionary Tale: Inheriting a BMW R100GS project

Love ’em or hate ’em, BMW’s GS behemoths have dominated the ADV market for almost four decades now. Five years ago, the 500,000th GS rolled off the Berlin production line, and we’re betting it won’t be long before the go-anywhere boxer hits the million mark.

We don’t see many GS customs, though. These machines are a triumph of function over form, and most owners like it that way.

So this R100GS is something of a rarity—and its backstory is rather strange too.

It belongs to Hasselblad Master photographer and bike builder Gregor Halenda, who is best known for an amazing KTM 2-wheel-drive motorcycle he collaborated on for the apparel brand REV’IT!

It some respects this is a cautionary tale about buying a project bike started by someone else. When the R100 GS arrived in Gregor’s workshop in Portland, Oregon, it didn’t take long for problems to surface.

“While the fabrication was great on the tanks, the overall mechanical condition was horrible,” says Gregor.

“The bike burned a quart of oil every 100 miles. It was down on power, and it wouldn’t run in the mornings because the petcocks were plumbing parts that let water and debris into the carbs.”

“I don’t know why the engine was in such bad shape, and maybe the previous owner didn’t either.”

Gregor didn’t complain because he considered this bike to be a test bed for his next build. He’s replaced everything except the three custom tanks—the rear is in a monocoque subframe—the frame, and the exhaust.

When Gregor took the engine apart he realized that a full rebuild was in order. “The heads were shot, the cylinders were shot, the pistons were toast, the rods were fried, the crank was shot and the crank bearings and block were ruined!”

So Gregor dumped that engine and installed a solid motor from an early 80s BMW R100RS, complete with a big valve conversion and head work by the Portland, Oregon shop Baisley Hi-Performance.

It fits just nicely into the braced frame, raised up and tipped back a little for extra clearance. The GS now has some serious grunt.

The 304 stainless steel exhaust came with the GS, but Gregor had to modify it by changing brackets and the backpressure. “It’s actually the wrong diameter, so I’ll remake it in the correct diameter.”

The suspension is another big upgrade: Gregor’s installed beefy 48mm WP upside-down forks from a KTM 690R, using KTM 450 SX triples and a custom fabricated steering stem.

The single disc brakes are Brembo, with a twin-piston floating caliper at the front.

The swingarm is from an R1100 GS—but it’s been cut and sectioned, with the shock mount repositioned, to allow fitment of the biggest possible 18-inch tire.

The driveshaft is a hybrid of parts from the R1100GS and R100GS, with the final drive coming from an R850R. It’s got 37/11 gearing, the lowest possible.

New rims and billet hubs from Denver-based Woody’s Wheel Works have made a huge difference.

They are very narrow: 21×1.6 and 18×2.15. “These are true off-road rims,” says Gregor. “BMWs are made for 17-inch rims, and the rear wheel squeezes the huge 140/80-18 Goldentyre GT723R into a very tall, round shape.”

“It rolls over things much better, and the round profile makes it much quicker to turn now.”

An extreme enduro Goldentyre ‘Fatty’ front complements the giant Rally Raid-style rear. “The traction is mind-bending for a big bike,” says Gregor. “It also has over 11 inches of suspension travel; previously it was nine, so it sits much taller now but with greater stroke.”

Cutting 20 pounds off the rotating weight apparently feels like more than 100 pounds. “The original owner got the GS down from 500 to 428 pounds, and I’ve taken it down to 400—with all that being in the rotating and unsprung weight,” says Gregor.

Adding to the rider enjoyment are new ProTaper bars in a ‘CR High’ bend, Renthal half waffle grips, and modified Fastway pegs from Pro Moto Billet. Gregor also made up new shifter and brake assemblies using stainless steel and precision needle bearings

The wiring loom on the BMW was neatly done, but it’s now upgraded with a Euro MotoElectric (EME) charging system and ignition.

There’s also a Trail Tech Voyager Pro instrument—a cutting-edge off-road GPS system with built-in Bluetooth for phone connections, and a 4-inch color touchscreen.

“I feel like the bike is ‘mine’ now,” says Gregor. “I’ve spent more time sorting it than the original owner did building it! I consider it a mule—a test bed for my next bike.”

“To get the weight I really want to be at—350 pounds—will require a new frame and much lighter bodywork. But the bike works great now, and it’s a blast to ride.

Gregor’s now going to design a new frame from scratch and test out some more motor mods. “I’ve become friends with Walt Siegl and he’s convincing me to do composites for the body and tank.”

“My long-term goal is to build the next bike into the ultimate custom adventure bike. A couple of people have expressed interest in having me build a series of bikes, like Walt does, but on the BMW platform.”

“Custom adventure bikes are the next big thing. I’ve raced, rallied and adventured, and I know what works. My bikes are function and form together: never at the expense of one or the other.”

Amen to that. And we can’t wait to see what this formidable GS turns into next.

Gregor Halenda Instagram

0 notes

Text

Top 7 Ways to Support Sustainable Fashion

dailymotion

30 Tips in 30 Days Designed to Help You Take Control of Your Health

This article is included in Dr. Mercola's All-Time Top 30 Health Tips series. Every day during the month of January, a new tip will be added that will help you take control of your health. Want to see the full list? Click here.

Shopping is often referred to as "retail therapy." Some suggest buying stuff, especially new clothes, can make you feel better — more relaxed, perhaps, or prettier or popular. While shopping for the latest trendy fashions may boost your mood temporarily, most people agree the positive vibes seldom last long.

Even if they did, there is more to modern fashion than meets the eye. Underneath all the glitz and glam portrayed in store windows are layers of what a new BBC documentary refers to as "fashion's dirty secrets."

If you think turning over your wardrobe frequently has little impact on world events, you may want to take an hour to watch the film. From start to finish, it will compel you to seriously consider how the fashion industry is actually wreaking havoc on the environment and endangering human health.

BBC Reporter Suggests Our Clothes Are Wrecking the Planet

In the featured 2018 documentary, BBC investigative reporter Stacey Dooley unearths some of the fashion industry's "dirty secrets."1 Her conclusion: Our clothes are wrecking the planet. At the onset of the film, Dooley is quick to admit she is a fan of fashion.

"It's retail therapy," she says. "For me, shopping is a way to unwind. I buy a treat, and I get home, try it on and take loads of photos wearing it." Like many, she puts the clothes on, poses in front of a full-length mirror and uses her smartphone to snap a bunch of photos. Later, she posts her favorite pictures on social media, which attracts a flurry of comments from friends and followers.

Dooley notes how easy it is to get pulled into a relatively new trend called "fast fashion," which alludes to how designers and retailers introduce new collections on a weekly basis to keep consumers hooked on clothing. Because clothing lines turn over rapidly, buyers often feel pressure to keep pace with the latest trends, even when they already have a closet full of perfectly useable clothing.

"Fast fashion lures us into buying more clothes than we need," asserts Lucy Siegle, a journalist and author specializing in environmental issues and one of Dooley's interviewees in the documentary. "It's a production system that brings us clothes at intense volume." The problem is our insatiable demand for cheap copies of catwalk fashion is having a devastating impact on the environment.

Like Dooley, you may be surprised to learn that fashion is second only to oil on the list of the top five most polluting industries in the world. That revelation took Dooley on a global adventure to further investigate the impact fashion has on vital aspects of living such as air quality, the economy, human health and water supplies.

Nonorganic Cotton Is One of the Worst Offenders of the Environment

Nonorganic cotton is one of the fibers Dooley reveals as doing the most harm to the environment, particularly as it relates to its devastating impact on fresh water supplies.

Finding out that cotton is one of the "bad guys" may surprise you, especially if you have been influenced by the U.S. industry group advertising that, for nearly 50 years, has promoted conventionally grown cotton as the "fabric of our lives."2 Dooley notes some of the "dirty secrets" associated with nonorganic cotton include the:

Pesticides used in cotton farming

Dyes and other chemicals used in manufacturing items made from cotton

Immense amounts of water needed to produce and process it

In the film, Dooley is told it can take upward of 15,000 liters (about 4,000 gallons) of water to grow the cotton necessary to make some brands of jeans. "I've never associated clothes production with pollution before," she said.

Vital Waterways Damaged by Cotton Production and Textile Manufacturing

In addition to being chemical-dependent, conventionally produced cotton also needs water — lots of water. Dooley discovered the amount of water needed in some cases is enough to nearly drain a sea in a few decades. On a visit to Kazakhstan, Dooley heard firsthand about how the water level of the Aral Sea began receding in the early 1970s.

The Aral Sea is situated between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan — the world's sixth-largest cotton producer among 90 cotton-growing countries.3 At the time cotton began making inroads, fish started dying from the chemical runoff from cotton fields. Now, in an area that used to be covered in turquoise blue water, you find a sparsely populated, barren wasteland.

The Amu Darya, one of the rivers that fed the Aral, was diverted into cotton-production farms in Uzbekistan and sucked dry before it could reach the sea. In Kazakhstan, what used to be a thriving seaport is now nearly 80 kilometers (50 miles) from the water's edge. The country's fishing industry has been obliterated by its neighbor's cotton industry.

Sadly, the former Kazakhstani seabed is heavily contaminated with pesticides, which prevents plant growth. Locals say wind-driven toxic dust has led to high rates of cancer, tuberculosis and other illnesses among those eking out a living there. The negative impact of cotton is felt daily in the local economy, public health and weather.

"You don't understand the enormity of the situation until you're here," asserts Dooley, standing on the dry earth that was once the Aral seabed. Camels and horses roam in an area once teeming with fish and other sea life. "[D]id I know cotton was capable of this? Of course, I didn't. I had no idea."

Beyond cotton, textile manufacturers themselves also misuse water resources. Dooley visited Indonesia to get a firsthand look at the Citarum River, known as the world's most polluted river. The area around the Citarum is home to more than 400 factories thought to be releasing toxic chemicals into waterways across the region on a daily basis.

Touring the river by raft, Dooley observed several hues of colored dye being pumped into the water and well as bubbling, bad-smelling foam. Toxicology results indicated the river is heavily polluted by heavy metals, including arsenic, cadmium, lead and mercury, which damages the health of local residents who depend on the river for drinking water as well as for bathing and washing clothes.

"To me, this feels like a complete catastrophe, and it's worth bearing in mind that Indonesia isn't even in the top five garment manufacturing countries globally," Dooley commented.

Sustainability: A Real Issue That Needs To Be Addressed in the Fashion Industry

In the U.S. alone, the impact of fashion has been outlined as follows. Every year:4

13.1 million tons of textile waste are created

11 million tons of textile waste end up in landfills

68 percent of the water used to create one pair of jeans revolves around fiber production alone

Because sustainability is such a huge issue for the textile industry, as part of her investigation, Dooley attended the Copenhagen Fashion Summit — a gathering billed as "the world's leading business event on sustainability in fashion." Unfortunately, not many of the clothing brands participating in the event were willing to speak to Dooley on camera.

As such, she stated, "This summit is a sign that some in this industry are working to clean up fashion, but I have felt the brands' refusal to talk to me make it look like some of them have something to hide."

That said, Dooley was able to speak to Paul Dillinger, vice president of global product innovation for Levi Strauss & Co., the $5-billion American brand that produces denim jeans and jackets and other clothing. "We're working on a solution that takes old garments, chemically deconstructs them and turns them into a new fiber that feels and looks like cotton, but with zero water impact," he said.