#Eduardo P. Archetti

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The transformations of tango

[by Eduardo P. Archetti]

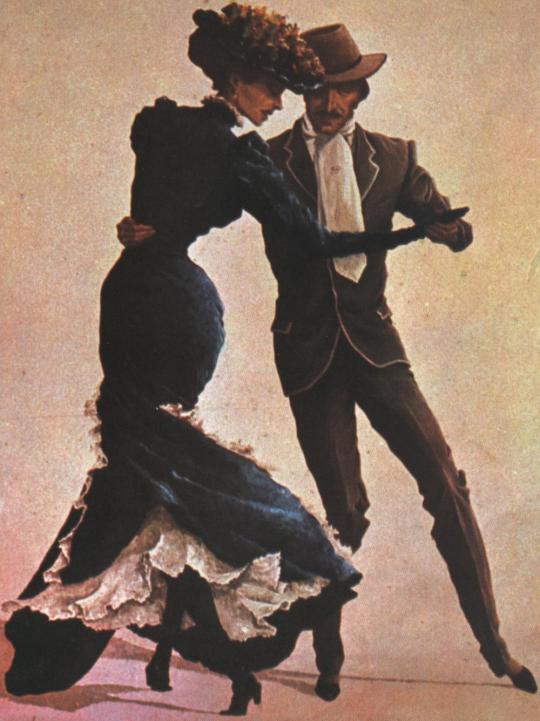

painting by Sigfredo Pastor

Between 1890 and 1914, Argentine became one of the great immigrant nations in the modern world. In 1914 around one-third of Argentina’s population of almost eight million was foreign-born, the majority being Italians and Spaniards. A mirror of this historical pattern exists in the growth and development of the capital city of Buenos Aires (the city of tango). By 1930 the city had almost 3 million inhabitants, one third of whom were immigrants. Buenos Aires became a kind of cultural Babel, wherein English was the language of commerce and industry, French was the language of culture, and the tongues of daily life were a mixture of Spanish (and Galician), Italian (various dialects) and a mixture of Western and Eastern European languages. Buenos Aires in the 1920s, like New York, represented in effect a ‘truly global space of cultural connections and dissolutions’ long before anthropology discovered global culture, diasporas and multinational encounters.

The tango was born in the arrabales (the outskirts of the city) of Buenos Aires in the 1880s. Borges pointed out that tango was a typical suburban product and that in the arrabales the rural presence was still important but did not radically influence its development. He wrote that ‘the tango is not rural, it is porteño’ [i.e. from Buenos Aires]. One of the social figures in the arrabal was the compadre, a male character with roots in the rural areas, often employed in the slaughter houses that proliferated there.

Rural gaucho / semi-urban compadre / urban compadrito

Collier has vividly described him as follows:

The free nomadic gaucho world had more or less vanished by the 1880s, yet the suburban compadre did perhaps inherit certain gaucho values: pride, independence, ostentatious masculinity, a propensity to settle matters of honour with knives. More numerous than the compadres were the young men of poor background who sought to imitate them and who were known as compadritos, street toughs well depicted in the literature of the time and easily identifiable by their contemporaries from their standard attire: slouch hat, loosely-knotted silk neckerchief, knife discreetly tucked into belt, high-heeled boots’.

“Compadrito afroargentino. Buenos Aires, ca. 1910, colección Silvio Killian.” From “El origen negro del Tango”.

By 1890 a new style of couple dancing was called baile de corte y quebradas (cut-and-break dance). Its was also know as milonga, a name that also designated a rural dance.

Milonga, Buenos Aires, 1915

In the new form the compadritos combined the milonga with the style and movement of the candombe, the popular dance of the Black Argentines living in Buenos Aires, characterized by quebradas and cortes. The quebrada was an improvised, a very athletic contortion, while the corte was a sudden pause, a break in the normal figures of the dance.

Scène de candombe, à Montevideo, eau-forte des années 1870

In the tango the Argentine black population that almost had disappeared by the end of the nineteenth century was recuperated in a kind of unexpected marriage with the habanera, the Spanish-Cuban rhythm that was very trendy in Latin America. Collier has perfectly summarised this creative process:

‘The tango...was just a fusion of disparate and convergent elements: the jerky, semi-athletic contortions of the candombe, the steps of the milonga and mazurka, the adapted rhythm and melody of the habanera. Europe, America and Africa all met in the arrabales of Buenos Aires, and thus the tango was born – by improvisation, by trial and error, and by spontaneous popular creativity’

Urban life in Buenos Aires was rapidly transformed during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Luxury hotels, restaurants, bistros, hundreds of cafés, a world-famous opera house and theatres were built by European architects. This prompted changes in the use of leisure time and created a new environment outside the walls of privacy and home. The appearance of public arenas created new conditions for public participation and enjoyment where cultural life, sports and sexual concerns dominated. Four institutions, where tango as dance was prominent, provided the public with new excitements and opportunities for the deployment of sexual fantasies: the brothel, the ‘dancing academies’ (academias de baile), ‘cafes with waitresses’ (café de camareras), and the cabarets. These arenas provided a space for women, albeit of a special kind.

The tango was directly related to these public contexts: in the last two decades of the nineteenth century, the brothel and the ‘dancing academies’ were the places where the original tango dance was created. Later, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the cabaret became a privileged public space for dancing, playing and singing. It has been assumed that originally the tango was only music and was mostly danced by male couples. However, the importance of the ‘dancing academies’ as meeting places for men and ‘waitresses’ or for couples cannot be overlooked.

The first period of tango, lasting from 1880 to 1920, has been called la Guardia Vieja or ‘the old guard’. Harp, flute, violin and the guitar dominated the orchestra until the 1920s, when the piano and bandoneon were gradually introduced. At the beginning, the tango was for dancing and not for listening. The texts accompanying the music were direct, daring, insolent, and, in the opinion of many, reflected a kind of male primitive exhibitionism.

The new tango developed after the 1920s, and has been called the tango of la Nueva Guardia or ‘the new Guard’. Both the musical composition of this period and the new orchestras gave more freedom to the soloists. The most important change, however, can be observed in the lyrics. The new authors of the tango tell compressed, moving stories about characters and moral dilemmas that were easily understood and identified by a vast, heterogeneous lower and middle class audience. Thus, the tango shifted from being first and foremost a musical expression to being primarily a narrative interpreted by a plethora of extraordinary singers, both male and female.

The orchestras gradually entered into the dancing halls and in the cabarets. The cabarets of Buenos Aires in the 1920s were generally elegant, but also dark and secretive, definitely not a place for family entertainment. The cabaret became both a real and an imagined arena for ‘timing out’ and, for many women, for ‘stepping out’, even though only a minority of women actually moved into its sphere. It was both an existing physical space, and a dramatic fictional stage for many tango stories. In the tango lyrics the cabaret appears as a key place for erotic attraction, a powerful image to contrast to the home, the local bar and the barrio (the neighbourhood). In this setting, as well in the different dancing arenas, the clothes were urban, modern, elegant and sophisticated. Neither dancers nor orchestras or singers used gaucho clothes, a matter evidently out of place. Tango was thus disconnected from the rural origins, the mixed dress of the compadritos, and turned into the representation of a quintessential urban way of life.

The globalization of tango took place during this period with the help of modern technology: radio, movies and records. Some of the singers became famous worldwide. This very process of globalization served to invent a ‘tradition’, a mirror in which Argentines could see themselves precisely because the ‘others’ began to see them. The narrative, the dance and the music of tango became a key element in the creation of a ‘typical’ Argentine cultural product.

The tango as a dance arrived to Paris as early as in the in the 1910s and it was seen as exotic as other musical genres: tropical Cuban music, flamenco, Russian and Hawaiian dances, and, later, North American jazz. It is in this context that an urban dance will be associated to a typical gaucho bodily creation. The European gaze conditioned the evolution of the dance and the way the opposition between wild and sophisticated eroticism was presented.

The tango was experienced as different because it was coming from a distant place, from a country with a vast pampa populated by gauchos that had attracted in the last decades millions of European immigrants. Savigliano has pointed out that the fascination of tango as a dance was not necessarily related to an instinctive sensuality, like in many ‘primitive’ dances, but to what she calls the process of seduction: a couple dancing and keeping their erotic impulses under control ‘measuring each other’s powers’. However, tango was seen as an exotic dance coming from an exotic place with a flavour of primitivism. André de Fouquiéres, a dance pedagogue, wrote in 1913 that tango ‘was a dance of the famous gauchos, cattle herders in South America, rough men who evidently cannot enjoy the precious manners of our salons – their temperament goes from brutal courtship to a body-to-body that resembles a fight- the tango...cannot be directly imported. It must be stopped at customs for a serious inspection and should be subjected to serious modifications’.

Primitivism was seen as ‘subverting the foundations of rational order in order to pursue the irrational for its own sake’. As an artistic expression it was seen rude, naive, expressing great feeling and great passion, lacking structured narrative and putting a strong emphasis on extreme bodily exhibitions. In the 1910s Argentine dancers had problems in finding jobs in Paris and if they did many of them were obliged to wear gaucho costumes. In this way it was communicated that the ‘wild’ and ‘exotic’ dance was performed by authentic Argentines. The same happened with touring orchestras and dancers all over Europe and United States. Nochlin has characterised this attitude as a way of defining the ‘other’ in relation to a ‘peculiar elusive wild life’.

However, the fascination for primitivism in the European representations of the tango was ambivalent because it became a typical dancing-hall and ball-room dance. The exotic wild and original choreography, developed by Argentine dancers, was transformed by French pedagogues into a stylistic and almost ballet-like dance. De Fouquiéres suggested a kind of choreographic revolution replacing the countless steps into just eight main figures. These attempts to domesticate the tango were for the most part favourably received. Tango was thus transformed into a global dance once a reduced choreographic grammar was produced. Borges commented on this transformation, pointing out that, before the triumph in Paris, the tango was an ‘orgiastic devilry’ and, after it, just ‘a way of walking’ – from sexual wildness into urban dance.

– Eduardo P. Archetti, “Gaucho, Tango, Primitivism, and Power in the Shaping of Argentine National Identity”, University of Oslo (abridged excerpts)

35 notes

·

View notes