#Earl Bostic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"A Portrait of Thelonious:" Bud Powell's Tribute to Monk and His Enduring Genius

Introduction: When jazz pianist Bud Powell recorded “A Portrait of Thelonious” on December 17, 1961, it represented both a homage to his longtime friend and fellow innovator Thelonious Monk and a personal statement of artistic resilience. Released in 1965 on Columbia Records, the album captures Powell’s profound understanding of Monk’s music while highlighting his distinctive style. Accompanied…

#A Portrait of Thelonious#A Tribute to Cannonball#Brian Fahey#Bud Powell#Cannonball Adderley#Charles Albertine#Classic Albums#Earl Bostic#Harry Warren#Jazz History#Kenny Clarke#Mack Gordon#Nica de Koenigswarter#Pierre Michelot#Thelonious Monk

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alto saxophonist Earl Bostic was a technical master of his instrument, yet remained somewhat underappreciated by jazz fans due to the string of simple, popular R&B/jump blues hits he recorded during his heyday in the '50s.

Born Eugene Earl Bostic in Tulsa, OK, on April 25, 1913, Bostic played around the Midwest during the early '30s, studied at Xavier University, and toured with several bands before moving to New York in 1938. There he played for Don Redman, Edgar Hayes, and Lionel Hampton, making his record debut with the latter in 1939. In the early '40s, he worked as an arranger and session musician, and began leading his own regular large group in 1945. Cutting back to a septet the next year, Bostic began recording regularly, scoring his first big hit with 1948's "Temptation." He soon signed with the King label, the home of most of his biggest jukebox hits, which usually featured a driving, heavy, R&B-ish beat and an alto sound that could be smooth and romantic or aggressive and bluesy.

In 1951, Bostic landed a number one R&B hit with "Flamingo," plus another Top Ten in "Sleep." Subsequent hits included "You Go to My Head" and "Cherokee." Bostic's bands became important training grounds for up-and-coming jazzmen like John Coltrane, Blue Mitchell, Stanley Turrentine, Benny Golson, Jaki Byard, and others. Unfortunately, Bostic suffered a heart attack in the late '50s, which kept him away from music for two years. He returned to performing in 1959, but didn't record quite as extensively; when he did record in the '60s, his sessions were more soul-jazz than the proto-R&B of old. On October 28, 1965, Bostic suffered a fatal heart attack while playing a hotel in Rochester, NY.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earl Bostic “For You” From my grandparents collection, an artist ai’d never heard of. He is a fantastic saxophonist, the album is one of my favorite kinds of jazz - a very horn heavy, complex but neat arrangements, and just so relaxing. This will be in heavy rotation for a bit. (1956, King Records)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Strictly Midnight Vol. 2

Harlem Nocturne (1957) - Illinois Jacquet Heavy Soul (1962) - Ike Quebec Minor Impulse (1962) - Ike Quebec Chitlin Con Carne (1963) - Kenny Burrell Somethin’ Strange (1961) - Baby Face Willette All Night Long (1964) - Freddie Roach Blue Monday (1959) - Ike Quebec Harlem Nocturne (1956) - Earl Bostic Track A - Solo Dancer (1963) - Charles Mingus Bahia (1962) - Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis Midnight At Minton’s (1961) - Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis & Johnny Griffin Quintet Night Tide (1961) - Carmell Jones Mox Nix (1958) - Art Farmer Blue Leo (1961) - Leo Parker Morris The Minor (1961) - Richard Holmes & Gene Ammons Angel Eyes (1965) - Gene Ammons Willow Weep For Me (1959) - Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis Cry Me A River (1955) - Dexter Gordon You Don’t Know What Love Is (1961) - Charlie Rouse Left Alone (1959) - Mal Waldron Round About Midnight (1962) - Don Byas Love Song From “Apache” (1963) - Coleman Hawkins Quartet Goodbye Pork Pie Hat (1959) - Charles Mingus Blues For Mr. Broadway (1965) - Oliver Nelson

Modern jazz classics for nighthawks. Cover: Ike Quebec

Compiled by Abeja Mariposa

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Coles (July 3, 1926 – December 21, 1997) was a jazz trumpeter.

He was born in Trenton, New Jersey. He grew up in Philadelphia and was self-taught on trumpet.

He spent his early career playing with R&B groups, including those of Eddie Vinson (1948–1951), Bull Moose Jackson (1952), and Earl Bostic (1955–1956). He was with James Moody (1956-58) and played with Gil Evans’s orchestra (1958-64) including for the album Out of the Cool. He spent time with Charles Mingus in his sextet, which included Eric Dolphy, Clifford Jordan, Jaki Byard, and Dannie Richmond. He played with Herbie Hancock (1968-69), Ray Charles (1969–71), Duke Ellington (1971–74), Art Blakey (1976), Dameronia, Mingus Dynasty, and the Count Basie Orchestra under the direction of Thad Jones (1985–86).

In 1985, he settled in the San Francisco Bay Area; he recorded with Frank Morgan and Chico Freeman the following year. He returned to Philadelphia in 1989, where he worked with Morgan and was part of Gene Harris’s Philip Morris Superband. In 1990, he recorded with Charles Earland and Buck Hill. He was recorded as a leader several times throughout his career. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 4.25

Beer Birthdays

Al Levy (1860)

Cassio Piccolo (1960)

Stephen Beaumont (1964)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Batman; comic book character (1940)

Ella Fitzgerald; jazz singer (1917)

Jason Lee; actor (1970)

Meadowlark Lemon; Harlem Globetroters basketball player (1932)

Edward R. Murrow; broadcast journalist (1908)

Famous Birthdays

Karel Appel; Dutch painter (1921)

Hank Azaria; actor (1964)

Andy Bell; pop singer (1964)

Earl Bostic; saxophonist (1913)

William J. Brennan Jr.; U.S. Supreme Court justice (1906)

Joe Buck; sportscaster (1969)

Ron Clements; animator (1953)

Oliver Cromwell; English politician (1599)

Willis "Gator" Jackson; saxophonnist (1932)

Albert King; blues singer (1923)

Jerry Leiber; pop songwriter (1933)

Guglielmo Marconi; physicist, radio inventor (1874)

Paul Mazursky; film director (1930)

Flannery O'Connor; writer (1925)

Al Pacino; actor (1940)

Eugene “Gene Gene the Dancing Machine” Patton; stagehand, dancer (1932)

Wolfgang Pauli; physicist (1900)

Talia Shire; actor (1946)

John Frank Stevens; Panama Canal engineer (1853)

Renee Zellweger; actor (1969)

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Flamingo · Earl Bostic & his Orchestra

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

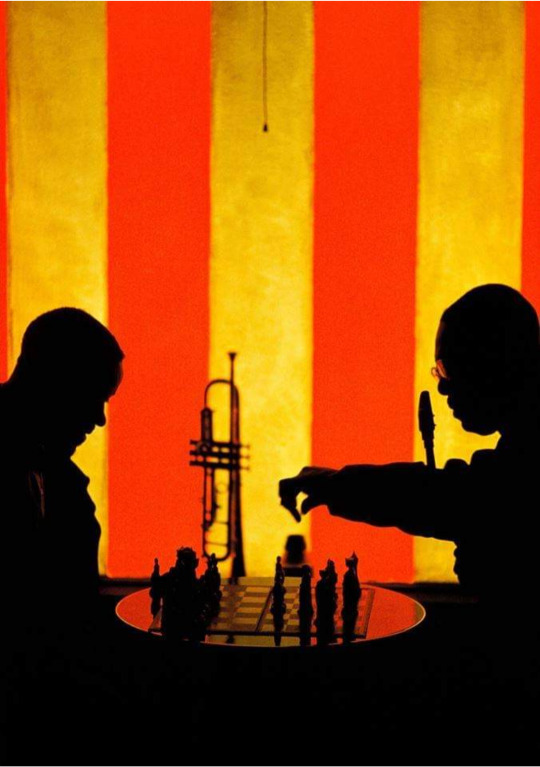

Earl Bostic and his trumpet player play chess, San Francisco, 1960.

Black Hawk nightclub in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conductor-arranger Gene Page introduced Marvin to Jewel Price, a black woman with whom Marvin would become extremely close. Nearly twenty years Gaye's senior, Mrs. Price was a real estate agent. Marvin found her effusive, energetic personality both earthy and charming. A woman with connections to millionaires throughout southern California, she'd sold homes to stars such as Nat Cole, Art Tatum, and Earl Bostic. A passionate music lover, Jewel had an almost mystical power of persuasion over Gaye. 'Mrs. Price could get him to do things other people - even I - couldn't,' said Marvin's mother. 'Get her to tell you about Marvin.'

'I loved him,' Jewel explained enthusiastically as we sat in her spacious Los Angeles home, "and he loved me. He said he'd never met anyone like me before. I treated Marvin like a king, because that's what he was. I'd send him flowers, buy him candy - that kind of thing. He appreciated my thoughtfulness and would return the favors.'

Was the relationship sexual?

'Honey, please! Once he playfully suggested something, but I said to him, I said, 'Marvin, I'm a Christian lady with Christian morals. We're friends and nothing more.' No, Marvin was always a perfect gentleman with me.'

She added, 'He trusted me. In fact, he had me take Anna and her sister Gwen around looking for homes. That was fun for a few hours, but I couldn't keep up with those ladies. They never stopped partying. Marvin also had me looking for houses for him. He never bought one, though I did find him a three-acre place to rent in Palm Springs for awhile. He took me down there all the time. Meanwhile, I'd take him to Malibu where we'd visit my rich friends, sit by the beach, and look at the ocean. With me, Marvin could relax and be himself. When he needed something done, I'd find a way to do it.

I was forceful with Marvin. I told him when he was doing something wrong, and I wasn't afraid to scold him. He respected that. In fact, he put me on a pedestal. He treated me like a queen. I love Mrs. Gay, but she was never firm or frank enough with Marvin. He was so good to her, she was afraid of angering him.

Marvin confided in me when he started having problems with Jan, and that broke my heart. You see, he loved that girl heavily and strongly. But she had a very strange and powerful effect on him. She controlled him. After talking to Jan on the phone, he might spend the next three hours staring into space, looking so lost and sad. I'd say, 'Marvin, what is it?' and he wouldn't even reply. His moods changed minute to minute, and Jan could change him quicker than anyone. He was such a beautiful man, but so unstable.'

0 notes

Text

Three By Earl Bostic - Past Daily Nights At The Round Table

1. Back Beat – https://pastdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Back-Beat-Earl-Bostic-And-His-Orchestra.mp3 2. Moonglow – https://pastdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Moonglow-Earl-Bostic-Gene-Redd-Jr.-Joe-Mitchell.mp3 3. Steamwhistle Jump – https://pastdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Steamwhistle-Jump-Earl-Bostic-and-his-Orchestra.mp3 The legendary Earl Bostic this weekend – three…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Stanley Turrentine: The Soulful Saxophonist of Jazz

Introduction: Stanley Turrentine was a prominent saxophonist whose soulful sound and melodic improvisations made him a beloved figure in the world of jazz. With a career spanning over four decades, Turrentine left an indelible mark on the genre, collaborating with some of the biggest names in jazz and recording numerous critically acclaimed albums. In this blog post, we will delve into the life,…

View On WordPress

#Al Cooper&039;s Savoy Sultans#Earl Bostic#Illinois Jacquet#Jazz History#Jazz Saxophonists#Jimmy Smith#John Coltrane#Look Out!#Lowell Fulson#Max Roach#Milt Jackson#Shirley Scott#Stanley Turrentine#Tommy Turrentine

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

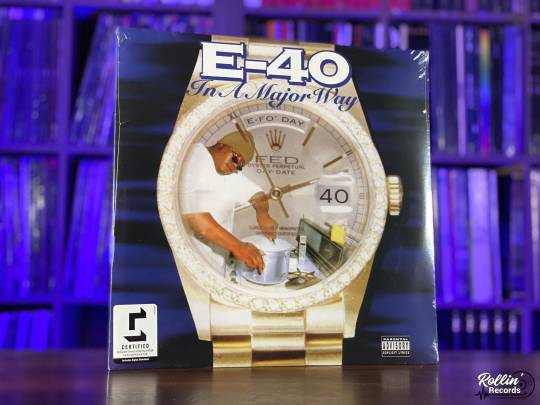

Throwback: E-40-Sprinkle Me Feat. Suga-T

E-40's "Sprinkle Me" features his sister Suga-T and was one of the singles from his 1995 album In A Major Way. The Bay Area legend's words flowed like the movement of curvy lines, and his unique rapping style made him identifiable and his songs unforgettable. Mike Mosley and Sam Bostic produced the song, which used rapper James Bailey's term sprinkle, which means to teach. "Sprinkle Me" was E-40's most successful single of the '90s, and In A Major Way, his first album on a label, charted in the Top Ten. Tupac Shakur and Mac Mall also appeared on this album. E-40, one-fourth of the hip-hop supergroup Mount Westmore, released their self-titled album in 2022. A lifelong entrepreneur, he recently launched the Earl Stevens Selections wine company and the Goon With The Spoon food brand. His cookbook Snoop Dogg Presents Gone With The Spoon and his 27th album Rule Of Thumb was released last week. He also dropped the video for "Off Dat Mob" from ROT.

youtube

youtube

0 notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

JOHN HANDY, UN MULTI-INSTRUMENTISTE MÉCONNU

“John just sounded so good. He’ll give you that old-school authentic thing, and when he plays a ballad, it’s hard to replicate if you don’t come from that era. But he’s also very modern and can be abstract in his thinking. A lot of his music is very free and open and forward-thinking.”

- Joe Warner

Né le 3 février 1933 à Dallas, au Texas, John Richard Handy III a d’abord fréquenté la St. Peter’s Academy de Dallas avant de déménager à Oakland avec sa famille à l’âge de quinze ans. À Oakland, Handy avait étudié au McClymonds High School. À l’époque, Handy avait déjà appris à jouer de la clarinette. Amateur de boxe, Handy était aussi champion poids plume, même s’il était aveugle d’une oeil et avait disloqué un de ses pouces dans un combat.

Également passionné de jazz, Handy avait l’habitude de s’endormir sur la musique de Charlie Parker pour étouffer le bruit des soirées que son beau-père organisait pour faire la promotion de son commerce illégal d’alcool. Parmi les camarades de classes de Handy à l’époque, on remarquait des membres de la famille Escovedo ainsi que le violoniste Michael White. Dans le cadre de ses études, Handy avait également fait la rencontre du futur athlète étoile Bill Russell, qui l’avait convié à participer à un tournoi de basketball. “I won the first game — of 15’’, avait expliqué plus tard Handy en riant.

Après avoir découvert que l’école possédait un excellent groupe musical, Handy s’était procuré une anche et une embouchure et avait appris à jouer du saxophone alto. De fait, Handy était tellement talentueux qu’il avait participé à sa première performance une semaine plus tard. Il précisait: “That was $5, and that became my way of making money.’’ Il avait ajouté: “Most of my gigs were in the East Bay. I was 17 before I went to San Francisco and discovered Bop City.”

À l’époque, Handy ne savait pas lire la musique et avait appris à jouer du saxophone alto en autodidacte à partir de 1949. Il poursuivait: “I taught myself how to read music, and if I heard something on the radio, I could play it,When Louis Jordan was popular, I learned some of his solos.”

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

Particulièrement influencé par le haut registre du saxophoniste Earl Bostic, Handy était encore adolescent lorsqu’il avait participé à une jam session à Bop City avec des membres de l’orchestre de Duke Ellington et du groupe de Gerald Wilson. Il avait aussi joué avec les saxophonistes Teddy Edwards et Frank Morgan. Après s’être inscrit au San Francisco State College, Handy avait fait ses débuts sur disque en 1953 avec le guitariste Lowell Fulson. Mobilisé et envoyé en Corée où la guerre venait tout juste de se terminer, Handy avait passé deux ans dans l’armée. Sa dernière affectation était au Presidio de San Francisco.

Après s’être marié, Handy avait eu un fils, John Handy IV, qui était devenu batteur. Après sa démobilisation, Handy était retourné au San Francisco State College. Même si le jazz ne faisait pas encore partie du programme du département de musique, Handy avait fait partie de groupes aux côtés d’autres passionnés de jazz. Comme l’avait expliqué Handy plus tard, à l’extérieur du campus, “some of the best people in jazz would come to Bop City. But by the mid-’50s, they were letting people in that would ruin it, because they didn’t know crap about music and didn’t care to know.” Handy avait même décliné une invitation de Charles Mingus pour venir jouer avec son groupe en 1958, car le contrebassiste avait une très mauvaise réputation auprès des musiciens qui, selon ses dires, ‘’complained a lot about Charles, but not in his company. They said he was a real asshole.”

Handy se produisait au Five Spot en 1958 avec le saxophoniste Frank Foster et le trompettiste Thad Jones, deux vedettes de l’orchestre de Count Basie, lorsqu’il avait été remarqué par Mingus. Le contrebassiste avait été tellement impressionné par le solo d’Handy sur le standard “There Will Never Be Another You” qu’il était sorti du club en criant “Bird’s back! Bird’s back!” (Charlie Parker était mort trois ans auparavant). Après s’être calmé, Mingus, qui devait se produire au club quelques semaines plus tard, avait fait venir Handy au bar pour lui faire une offre.

En dépit de l’obstruction d’un de ses professeurs particulièrement antipathique, Handy avait finalement décroché son diplôme en 1958 à l’âge de trente ans. Il expliquait: “I had ‘incompletes’ on my transcript that I had already completed and they never gave me the grade. This particular guy said in essence ‘You’re too raw.’ I took every took every course they had to get a B.A. and I finally graduated at 30.”

Après s’être installé à New York, Handy s’était joint au groupe de Mingus. Même s’il n’avait pas fait partie du groupe que durant un an, le séjour de Handy avait contribué à changer l’évolution du jazz, notamment dans le cadre des albums Mingus Ah Um et Mingus Dynasty, dans lesquels il avait participé à l’enregistrement des classiques “Better Git It in Your Soul’’, Goodbye Pork Pie Hat’’ (un éloge au saxophoniste Lester Young qui venait de mourir) et “Fables of Faubus’’, une dénonciation du gouverneur ségrégationniste de l’Arkansas, Orval Faubus. Tout aussi marquant avait été l’album Blues and Roots, dans lequel Handy avait fait équipe avec Jackie McLean au saxophone alto. Même si ces albums avaient été reconnus comme des classiques dès leur parution, Handy avait particulièrement excellé sur l’album Jazz Portraits: Mingus in Wonderland, un enregistrement en concert mettant en vedette le pianiste de San Francisco, Richard Wyands. Après avoir livré une performance au Five Spot, le quintet de Mingus s’était déplacé plus loin sur la même rue pour se produire à la Nonagon Art Gallery où il avait enregistré quatre pièces d’une durée totale de quarante-cinq minutes avec le saxophoniste ténor Booker Ervin (le seul autre musicien à avoir participé à tous les albums de Handy avec Mingus). Après le concert, le groupe était retourné au Five Spot pour prendre la relève de Sonny Rollins, qui avait fait les frais de l’intermission pendant son absence.

Après avoir enregistré quatre albums en un an avec Mingus, Handy était retourné à San Francisco où il avait fait ses débuts au début des années 1950 au Jimbo’s Bop City et partagé la scène avec de grands noms du jazz comme les saxophonistes Teddy Edwards, Frank Foster et Dexter Gordon. Handy avait aussi commencé à flirter avec le jazz modal, à une époque où très peu de ses pairs commençaient à peine à assimiler ce concept. En 1965, Handy avait présenté les résultats de cette expérimentation dans le cadre d’un concert présenté au Festival de jazz de Monterey, en Californie. L’enregistrement du concert, qui avait été publié par les disques Columbia l’année suivante sous le titre Live at the Monterey Jazz Festival, avait mérité à Handy deux nominations au gala des prix Grammy pour les pièces "Spanish Lady" (dans la catégorie de la meilleure performance de jazz) et pour sa composition "If Only We Knew". Le quintet de Handy était composé à l’époque du violoniste Michael White, du guitariste Jerry Hahn, et d’une section rythmique entièrement canadienne formée du contrebassiste Don Thompson et du batteur Terry Clarke.

Avec l’aide de sa femme, qui était également sa gérante, Handy avait aussi enregistré un premier disque comme leader en 1959. À l’époque, le vibraphoniste Milt Jackson s’était lié d’amitié avec Handy et sa femme et leur avait proposé d’habituer dans un de ses appartements situé près de Harlem. Décrivant ses débuts à cette époque, Handy avait commenté: “Most of my gigs were with Charles, but I played the whole summer of ’59 with Randy Weston at the Five Spot. Though Charles and Randy were both mavericks, Randy was more positive.” Handy avait ajouté: “We played with Randy six nights a week. That’s where my exposure came.’’

Handy se produisait au le pianiste Five Spot avec Randy Weston lorsqu’il avait rencontré la baronne Pannonica de Koenigswarter, une mécène qui avait été la protectrice de Charlie Parker et Thelonious Monk. Handy expliquait:

‘’One of the characters who came in to the Five Spot was the Baroness [Kathleen Annie Pannonica de Koenigswarter]; she came in with Thelonious Monk almost every night. She said, ‘Monk would like to speak to you’ as I’m coming off the bandstand, so I follow him into to kitchen, and Monk was a big man, his hat is almost touching the roof, and he kept walking, never turned around. He kind of looks up, not at me, and says, ‘You play your motherfucking ass off. You think,’ or maybe, ‘You play your motherfucking ass off, you think.’ I’m not sure which one he meant. And then he walked around me and out. I’m still scratching my head.”

Impressionné par le talent d’Handy, Monk lui avait plus tard proposé de faire sa première partie à la Jazz Gallery.

Handy avait également fait une tournée européenne avec son groupe en 1961. Par la suite, il avait travaillé comme soliste en Suède et au Danemark.

Retourné à San Francisco, Handy avait été très impliqué dans le mouvement des droits civiques. Il avait précisé: ‘’I couldn’t sit back, with all I’d gone through, and let somebody fight for me without trying to help my own cause.” À l’époque, des Afro-Américains comme le joueur de baseball Willie Mays des Giants de San Francisco faisaient l’objet d’une discrimination incessante, et Handy avait été arrêté durant une manifestation. Handy expliquait: ‘’I couldn’t sit back, with all I’d gone through, and let somebody fight for me without trying to help my own cause.” Afin de recueillir des fonds pour la cause, Handy avait formé le Freedom Band avec deux jeunes saxophonistes ténor, Mel Martin et Noel Jewkes. Le trompettiste Eddie Henderson faisait également partie du groupe.

À l’époque, Handy se produisait au Both/And Club sur la rue Divisadero. C’est dans ce club qu’Handy avait entendu pour la première fois la chanteuse Faye Carol. La chanteuse avait rencontré Handy au début des années 1970 alors qu’elle était mariée au professeur de musique Jim Gamble.

Même si le climat social était plutôt tendu à l’époque, Handy ne se rappelle pas que des incidents raciaux se soient produits dans les clubs de San Francisco ou dans le cadre de ses relations avec l’Union des Musiciens. “You don’t see that in jazz’’, avait expliqué Handy. Après avoir divorcé de sa première femme, Handy s’était marié avec une femme qu’il avait rencontrée au Five Spot et qui était devenue plus tard chancelier du San Francisco City College. Le couple s’était éventuellement acheté une maison sur la rue Baker.

En 1963, Handy a travaillé comme soliste sur la Côte Ouest avec des orchestres de musique classique comme le Santa Clara Symphony Orchestra et le San Francisco State College Band. L’année suivante, il avait retrouvé Mingus dans le cadre du Festival de Jazz de Monterey, en Californie. En 1966 et 1967, Handy avait fait une tournée aux États-Unis avec les Monterey All Stars. Il avait également participé à l’opéra The Visitation de Günther Schuller. En 1968, Handy a fondé un nouveau quartet avec Mike Nock, Michael White et Ron McClure.

Par l’entremise d’anciens camarades de classe du San Francisco College State, Handy avait été présenté au virtuose de la cithare Ravi Shankar, qui lui avait donné deux leçons privées sur la musique indienne. Comme Handy l’avait expliqué plus tard, “And I understood, because when I went to St. Peter’s, we sang Gregorian modal music. And African Americans are very modal. Later, I recorded with Ravi in India.’’

À la fin des années 1960, Handy avait également collaboré avec Ali Akbar Khan, un pionnier de la sarod, un instrument à cordes d’origine indienne. Andy poursuivait: “Then I got a call to play with [sarodist] Ali Akbar Khan. I went to his house in Marin County, and it was like I’d been playing with him all my life. I booked several concerts with him and paid him half of the ticket sales, though I realized that Indian musicians don’t do what we do. They don’t change keys and can’t play jazz.” Handy avait enregistré deux albums avec Khan. Zakir Hussain, avec qui il avait joué sur l’album Karuna Supreme en 1975, lui avait également fait cadeau d’un tabla.

La collaboration d’Handy avec Khan avait éventuellement donné lieu à l’enregistrement de l’album Karuna Supreme en 1975. À l’époque, Handy tentait de réaliser une symbiose entre la musique du Nord de l’Inde et les airs de Gospel qui avaient marqués son enfance avec sa grand-mère. Il expliquait: “I could relate it to the stuff I’d been exposed to in the African American church. At the first rehearsal with Ali Akbar Khan he said ‘Let’s just play,’ and I just understood it. I had met Ravi Shankar. He invited me to a concert in LA and gave me a couple of lessons. I did learn something from it, but I could always play it with my background in the blues.” Handy avait aussi travaillé en 1980 avec Lakshminarayana Subramaniam dans le cadre du groupe Rainbow.

Retourné au San Francisco State College (devenu l’Université de San Francisco State) en 1968, Handy avait repris sa carrière de professeur et avait pris la direction des études de jazz. Conscient d’être l’objet d’une certaine jalousie de la part des professeurs de musique classique, Handy avait commenté: “I know they were jealous of me because I could do what they did but they couldn’t do what I did.”

Comme mentor, Handy avait encouragé la carrière de plusieurs générations de jeunes musiciens. Lorsque le saxophoniste Hafez Modirzadeh était venu enseigner à San Francisco State, Handy l’avait pris sous son aile et l’avait initié à la musique non-occidentale. Ne tarissant pas d’éloges sur les compositions et les arrangements innovateurs d’Handy, Modirzadeh avait ajouté:

“It’s something that really connects him to jazz history, to Buddy Bolden and Louis Armstrong. You had to be there to see these people play. There won’t be a technical book by John Handy describing how he does what he does, that fingering and embouchure. It’s mystical, completely John Handy’s, and we’ll never know how he did it.I’ve asked him once or twice, ‘Can I come over and you show me how to do something?’ Very graciously, he’ll say, ‘I’m still working out some things that Charlie Parker did.’”

À l’époque, Handy avait aussi reçu une commande pour composer un Concerto for Jazz Soloist and Orchestra, qui avait éventuellement été interprétée par la San Francisco Symphony en 1970. Handy avait également enseigné à l’Université de Californie à Berkeley, à l’Université Stanford, au San Francisco Conservatory of Music et au City College de San Francisco.

La pièce-titre de l’album Hard Work (1976) était devenue le plus grand succès de la carrière d’Handy. En plus de s’être classée sur le palmarès Billboard, la pièce avait fait partie du répertoire des juke box à travers le monde. Toujours en 1976, Handy avait enregistré un album de jazz-fusion avec le guitariste Lee Ritenour. L’album intitulé Carnival est paru en 1977.

ÉVOLUTION RÉCENTE

Dans les années 1980, Handy s’était joint au groupe Bebop and Beyond. Basé à San Francisco, le groupe avait rendu hommage à des pionniers du bebop comme Dizzy Gillespie et Thelonious Monk. Gillespie s’était même joint au groupe comme artiste-invité dans le cadre de l’album qui lui était consacré. Au milieu des années 1980, Handy avait également participé à une tournée avec le groupe Mingus Dynasty.

À la fin des années 1980, Handy avait formé le groupe John Handy With Class qui le mettait en vedette aux côtés de trois chanteuses-violonistes.

Retiré dans sa résidence de Hillside après avoir été victime d’une légère attaque, Handy avait continué se consacrer à la musique. Comme l’avait expliqué sa partenaire de longue date, la chanteuse Faye Carol: “Before Jazz on the Hill, I hadn´t heard anything from John lately, so I was so happy when he said he’d do our [Aug. 13] show.’’ Un autre membre du groupe, le pianiste Joe Warner, avait ajouté: “I’ve been trying to get the opportunity to work with John since that Yoshi’s gig. And we have a great band for him, with Tarus Mateen on bass, who plays with [pianist] Jason Moran, and Jaz Sawyer, a great drummer I worked with when he was living up here, who’s been in Southern California.”

Multi-instrumentiste souvent sous-estimé, Handy joue à la fois du saxophone alto et ténor, du saxello, du saxophone baryton, de la clarinette et du hautbois. Il chante également à l’occasion. Très impliqué dans les musiques du monde, Handy avait consacré sa vie à transformer l’esprit humain par l’entremise de sa musique. Utilisant une instrumentation souvent inusitée, Handy avait toujours été un musicien et compositeur sans compromis qui échappait à toute étiquette. Principalement connu pour sa participation à des petits groupes comme les quintets et les quartets, Handy s’était également produit avec de grandes formations allant des big bands aux orchestres symphoniques, aux ensembles vocaux et aux chorales.

Comme chanteur, Handy excelle tant dans le blues que le scat et les ballades. Au cours de sa carrière, Handy s’était produit dans les plus grandes salles de concert d’un peu partout sur la planète, dont Carnegie Hall, le Lincoln Center, le Berlin Philharmonic Auditorium et le San Francisco Opera House. Il avait aussi livré des performances dans les plus importants festivals de jazz du monde, dont le Monterey Jazz Festival, le Newport Jazz Festival, le Playboy Jazz Festival, le Chicago Jazz Festival, le Pacific Coast Jazz Festival et les festivals de Montreux, d’Antibe, de Cannes, de Berlin et de Yubari et Miyasaki au Japon. Tout en continuant de se produire régulièrement dans les universités et les collèges, Handy fait également de nombreuses lectures sur les aspects techniques, académiques, spirituels et créatifs de la musique.

Parmi les plus récents enregistrements d’Handy, on remarque "Centerpiece" (1989), "Excursion in Blue" (1988), ‘’John Handy Live at Yoshi’s Nightspot" (1996) et "John Handy’s Musical Dreamland" (1996). Certains des premiers albums d’Handy ont été réédités sur CD, dont "John Handy: Live at the Monterey Jazz Festival" (1966), "The Second John Handy Album" (1966), "New View" (1967) et "Projections’’ (1968). En plus d’avoir enregistré avec Sonny Stitt, Handy a enregistré neuf albums avec le Charles Mingus Jazz Workshop.

Le pianiste Joe Warner, qui avait joué avec Handy pour la première fois au club Yoshi’s de San Francisco une décennie plus tôt, avait perdu contact avec le saxophoniste jusqu’à ce qu’il l’entende jouer en juin 2023 au Festival Jazz on the Hill avec le Akira Tana Quartet. On avait aussi remis un Jazz Icon Award à Handy dans le cadre de l’événement. Warner poursuivait: “John just sounded so good. He’ll give you that old-school authentic thing, and when he plays a ballad, it’s hard to replicate if you don’t come from that era. But he’s also very modern and can be abstract in his thinking. A lot of his music is very free and open and forward-thinking.” En 2009, l’organisme SF JAZZ a décerné à Handy un Beacon Award.

Le fils de Handy, John Richard Handy IV, est devenu batteur, et se produit avec son père à l’occasion. Handy est également le père du saxophoniste Craig Handy.

©-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

SOURCES:

GILBERT, Andrew. ‘’At 90, Bay Area Sax Great John Handy Is Still Composing His Legacy.’’ KQED Inc., 2 février 2023.

‘’John Handy.’’ All About Jazz, 2024.

‘’John Handy.’’ Wikipedia, 2024.

KALISS, Jeff. ‘’At 90, Saxophonist John Handy Still Puts In the Hard Work.’’ Classical Voice, 1er août 2023.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

This week on Everything Old Is New Again Radio Show, we feature the music of Dakota Staton

Some of the songs from her career that we will hear:

* I Hear Music

* Gladys Shelley’s I Did Everything Right With The Wrong Man (And Everything Wrong With The Right Man)

* Make It Easy on Yourself (Burt Bacharach, Hal David)

* plus “Let Me Off Uptown” (Earl Bostic, Redd Evans)

* of course, The Late, Late, Show

* and Is You Is, or Is You Ain’t My Baby recorded Live at Storyville, 1961

* And More!

More info at www.oldisnew.org

#EverythingOldIsNewAgainRadioShow #44thYear #PopStandards #GreatAmericanSongbook #Jazz #Showtunes #Cabaret

0 notes