#Dzawada’enuxw First Nation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Meet Hawilkwalał Rebecca Baker-Grenier of the Kwakiuł, Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw, and Skwxwú7mesh First Nations. Rebecca is a fashion designer who debuted her first collection at New York Fashion Week in 2022 and sees “fashion as a living practice that is rooted in our art form, laws, and worldview.”

See her work in the Museum’s Northwest Coast Hall as part of the Grounded by Our Roots exhibition, which features extraordinary works by up-and-coming Indigenous artists who draw inspiration from their cultural traditions.

#amnh#museum#things to do in nyc#new york city#fashion#indigenous art#northwest coast#northwest coast art

923 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kimowan Metchewais, “Cold Lake Fishing”, 2004/06

Koyoltzintli, “Gathering Roots” and “Spider Woman Embrace”, Abiquiú, New Mexico, 2019, from the series MEDA, 2018/19, Archival pigment print

(Alan Michelson “Hanödagayas (Town Destroyer): Whirlwind Series”, 2022 Archival pigment prints and “Pehin Hanska ktepi (They Killed Long Hair)”, 2021 Single-channel video installation: wool blanket and video projection; 1:05 minutes (looped), no sound)

Currently at the USF Contemporary Art Museum is Native America: In Translation curated by Wendy Red Star and organized by Aperture. The work included offers viewers a chance to discover new perspectives on the Native American experience.

From the museum- “The ultimate form of decolonization is through how Native languages form a view of the world. These artists provide sharp perceptions, rooted in their cultures.” —Wendy Red Star

Native America: In Translation assembles the wide-ranging work of nine Indigenous artists who pose challenging questions about identity and heritage, land rights, and histories of colonialism. Probing the legacies of settler colonialism, and photography’s complex and often fraught role in constructing representation of Native cultures, the exhibition includes works by lens-based artists offering new perspectives on Indigenous identity, reimagining what it means to be a citizen in North America today.

Works included in the exhibition address cultural and visual sovereignty by reclaiming Native American identity and representation. Honoring ancestral traditions and stories tied to the land, Koyoltzintli (Ecuadorian-American, b. 1983) reflects on how the landscape embodies traditional knowledge, language, and memories. Nalikutaar Jacqueline Cleveland’s (Yup’ik, b. 1979) photographs of contemporary tribal communities in western Alaska document Native foraging and cultural traditions as a form of knowledge passed through generations. Revealing stories of trauma and healing, Guadalupe Maravilla (American, b. El Salvador, 1976) communicates autobiographical and fictional narratives informed by myth and his own migration story.

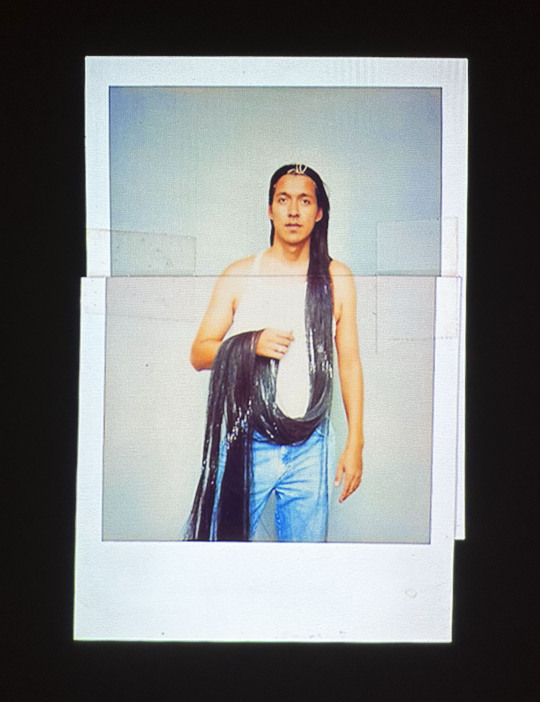

Expanding Indigenous archives and collective memory through photographic means, works by the late artist Kimowan Metchewais (Cree, Cold Lake First Nations, 1963–2011), drawn from his personal archive of Polaroid photographs, construct self-realized Native imagery challenging the authority of colonial representation. Excavating repressed colonial histories of invasion and eviction, Alan Michelson (Mohawk, Six Nations of the Grand River, b. 1953) reinterprets and repositions archival material to redress history from an Indigenous perspective. Marianne Nicolson’s (Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw First Nations, b. 1969) light-based installation projects Dzawada’enuxw tribal symbols of authority and power onto colonized spaces to contest treaties that imposed territorial boundaries on Indigenous lands. Duane Linklater (Omaskêko Ininiwak from Moose Cree First Nation, b. 1976) reconfigured the pages sourced from a 1995 issue of Aperture, featuring Indigenous artists, creating space for artistic improvisation and reinvention across generations.

Reflecting on performative aspects of Indigeneity and the colonial gaze, Martine Gutierrez’s (American, b. 1989) series of photographs reinterpret high-fashion magazine spreads with a revolving roster of identities and narratives to question Native gender and heritage. Working across performance and photography, Rebecca Belmore (Anishinaabe, Lac Seul First Nation, b. 1960) creates powerful reenactments of past performances incorporating organic materials that reference knowledge, labor, and care of the Earth in defiance of state violence of Indigenous people.

This exhibition closes 12/1/23.

Rebecca Belmore, “matriarch”, 2018, and “mother” from the series “nindinawemaganidog (all of my relations)”, 2018, Archival pigment prints

Photos by Rebecca Belmore and Installation by Marianne Nicolson

Marianne Nicolson’s installation detail

Nalikutaar Jacqueline Cleveland, “Molly Alexie and her children after a harvest of beach greens in Quinhagak, Alaska”, 2018 and “There are two main Yup’ ik names for crowberries or blackberries in Alaska, “paunrat” and “tangerpiit””, 2017, Archival pigment prints

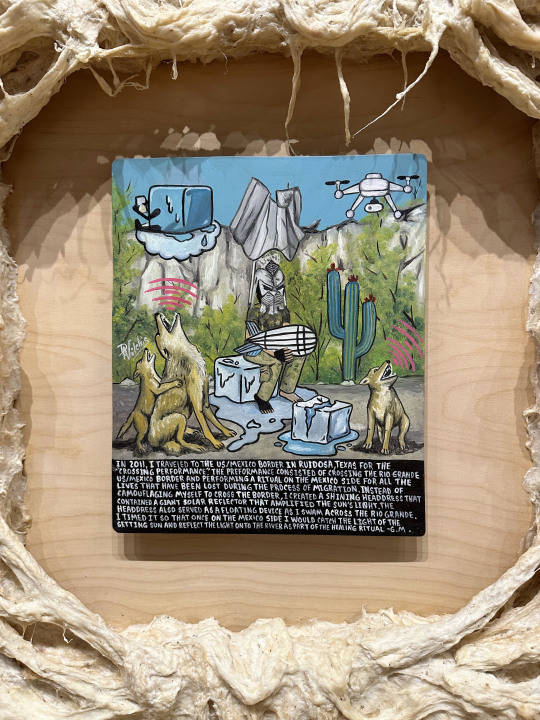

Guadalupe Maravilla, “I Crossed the Border Retablo”, 2021, Oil on tin, cotton, glue mixture, wood

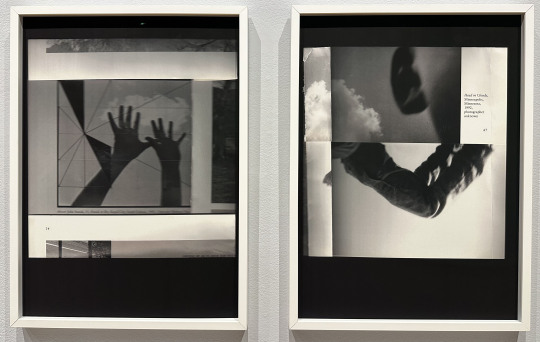

Duane Linklater, “ghost in the machine”, 2021, Archival pigment prints

Martine Gutierrez, “Queer Rage, Dear Diary, No Signal During VH1’s Fiercest Divas”, and “Queer Rage, THat Girl Was Me, Now She’s A Somebody”, 2018. digital chromogenic print

One of Kimowan Metchewais’ polaroids from the slide show

#USF Contemporary Art Museum#Native American Artists#Rebecca Belmore#Kimowan Metchewais#Alan Michelson#Martine Gutierrez#Institute For Research in Art#Marianne Nicolson#Duane Linklater#Koyoltzintli#Guadalupe Maravilla#Nalikutaar Jacqueline Cleveland#Mixed Media#Mixed Media Art#Art#Mixed Media Photography#Native American#Native American Art#Native American Heritage Month#Black and White Photography#Art Shows#Florida Art Shows#Native American History#Photography#Polaroid#Polaroid Photography#Tampa Art Shows

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Dzawada’enuxw First Nation is suing the federal government for granting nine fish farm licences in its territory without the nation’s consent.

According to the Federal Court lawsuit, the granting of licences to Cermaq and Marine Harvest encroached upon Aboriginal rights by threatening wild eulachon and salmon populations, traditional staples for the First Nations.

“It is a very simple, uncluttered case,” Jack Woodward, lawyer for the nation, told The Tyee. “If we can prove fishing is an aboriginal right and that fish farms have infringed on these rights, then federal licences allowing fish farms should fall.”

The lawsuit argues that the fish farm licences have exposed wild salmon and eulachon (a smelt-like species that provides essential oils and grease) to higher levels of sea lice and viral diseases, including piscine orthoreovirus(PRV), a disease of farmed Atlantic salmon.

“Furthermore, there is a credible body of scientific evidence indicating a direct link between PRV and heart and skeletal muscle inflammation (HSMI). Both PRV and HSMI are known to have deleterious effects on fish,” says the lawsuit.

“This fight is not only for my nation but all people of B.C. who live up and down the coast and love salmon,” said former elected chief Willie Moon in a Tyee interview.

Continue Reading.

#Justin Trudeau#First Nations#Dzawada’enuxw First Nation#Salmon#cdnpoli#canada#canadian politics#canadian news#canadian#Fish Farms#Fish Farming#British Columbia

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

B.C. First Nation files Aboriginal title claim challenging fish farms in their territory

Zig Zag | Warrior Publications | June 4th 2018 by Laurie Hamelin, APTN News, June 2, 2018 The Dzawada’enuxw First Nation of Kingcome Inlet filed a claim of Aboriginal title in British Columbia’s Supreme Court that affects ten fish farms in their traditional territory that they say are operating without their consent. “We have been saying no for 30 years,” says Lindsey Mae Willie of Dzawada’enuxw First […]

→ READ MORE ←

Get your Latest News From The Leftist Front on LeftPress.News → Support Us On Patreon! ←

#freeblr#socialism#news#Fisheries#aboriginal title#Dzawada’enuxw First Nation#fish farms#Kwakwaka'wakw#B.C. First Nation files Aboriginal title claim challenging fish farms in their territory#Warrior Publications#June 4th 2018

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amber Midwinter wearing dress by Himikalas Pamela Baker

#amber midthunder#fashion#indigenous fashion#celebrity fashion#celebrity style#indigenous designer#print#indigenous actor#indigenous actress#himikalas pamela baker#surface pattern#textile design#printed textiles#musgamakw dzawada’enuxw#tlingit#haida#squamish#first nations#turtle island#indigenous canadian designer

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indigenous Artists Radically Imagine a New Future

Submitted by Tram Nguyen on November 10, 2021

This session began with a song of welcome from cultural practitioner and filmmaker Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu (Native Hawaiian, Kanaka Maoli) that opened up a space for radical imagination and relationship. Artists from the 2021 cohort of NDN Collective’s Radical Imagination Grant shared their work from the project, which invests in Indigenous artists’ community-based expressions of “a radically imagined, more just and equitable future.”

Engaging with this work—whether it be taking in fine art photography and film, hearing Native languages spoken and sung, or learning about specific customs and ceremonial practices within the context of decolonization—is about experiencing the gift of centering Indigenous worldviews and knowledge.

Cara Romero (Chemehuevi), a contemporary fine arts photographer, shared images that visually express her people’s cultural landscape, presence and connection to the water, land, flora and fauna of the Mojave Desert of Southern California. “People outside the reservation have little idea about contemporary life of Natives on the reservation. Everything is taught as historic and bygone. From an early age, I knew I wanted to change this narrative,” she said. “I want to counter the narrative that we were historic and bygone, with an emphasis on our modernity, resilience, and the beauty all around us.”

Cara’s series of #Tongvaland images are a powerful disruption of the invisibility and erasure of California First Peoples, such as the Tongva of Los Angeles. Billboards with #Tongvaland and stunning images of Native women in regalia next to oil refineries or in natural springs that remain still amidst L.A. industrial spaces, the Hollywood Sign reimagined as TONGVALAND—these are examples of how Cara’s art radically educates and shifts understanding about a place like Los Angeles. “Los Angeles is a holy place,” she asserts, pointing out that it is second to Manhattan as home to the highest population of inter-tribal Indigenous residents.

Marianne Nicholson (Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw First Nations) is a visual artist whose project undertakes the reclaiming of meaning and repatriating of material culture forcibly removed from her people, whose homelands are on the coast of British Columbia. That work entails rebuilding her own understanding and knowledge, and designing community-based platforms to share and return the knowledge to the tribe. This included the carving of a 14-foot traditional feast dish, which was given to the community with a feast being planned around it.

Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu’s animated short film, Kapaemahu, tells a Native Hawaiian story hidden from history, that honors legendary healers who embodied two-spirit, dual male and female energy.

“My work focuses on the movement and advancement of my people, where the U.S. continues illegal occupation of our land. We struggle to know what is our identity because the colonization has been so great, the loss of language,” Hinaleimoana said. “My work is dedicated to challenging the norms, and sharing how our people understand the world.”

All 10 artists from the 2021 Cohort are featured at the Radical Imagination virtual festival on November 12, 2021.

Posted by Tram Nguyen on November 10, 2021 at 07:07AM. Read the full post.

0 notes

Text

BC First Nation Files Aboriginal Title Claim Challenging Fish Farms in their Territory

BC First Nation Files Aboriginal Title Claim Challenging Fish Farms in their Territory

by Laurie Hamelin / APTN News

Dzawada’enuxw leaders outside BC Supreme Court in Vancouver. Photo courtesy Lindsey Mae Willie

The Dzawada’enuxw First Nation of Kingcome Inlet filed a claim of Aboriginal title in British Columbia’s Supreme Court that affects ten fish farms in their traditional territory that they say are operating without their consent.

“We have been saying no for 30 years,” says…

View On WordPress

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tensions rise between RCMP and First Nations against fish farms by Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw Cleansing Our Waters, October 17, 2017 by Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw Cleansing Our Waters, October 17, 2017 For Immediate Release RCMP, Marine Harvest, and Department of Fisheries and Oceans has just arrived on site to where Members from six First Nations of the Kwakwaka’wakw have been occupying fish farms, in their territorial waters for nearly two months near Alert Bay, B.C. via Tensions rise between RCMP and First Nations against fish farms — Warrior Publications

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

B.C. fish farms hit by occupations following release of footage showing sickly, blind salmon

Willie Moon, Dzawada’enuxw First Nation Hereditary Chief: “We always said we never wanted these fish farms in our territory.”

#salmon#atlantic salmon#salmon farms#british columbia#conservation#environment#salmon farm#fish farm#fish farms#open net pen#salmon farming#fish farming#Salmon Are Sacred#Alexandra Morton

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

B.C. First Nation sues feds over Atlantic salmon farming in Pacific waters Dzawada’enuxw First Nation alleges 10 Atlantic salmon fish farms in the waters of their territory infringe on their Aboriginal rights to harvest eulachon and wild salmon. They allege farms threaten those species by exposing them to viruses and parasites and want them gone.

#North Shore affordable lawyer#North Shore assault lawyer#North Shore child support lawyer#North Shore Company lawyer#North Shore criminal defence lawyer#North Shore criminal lawyer#North Shore custody lawyer#North Shore divorce lawyer#North Shore Family lawyer#North Shore Farsi-Speaking Lawyer#North Shore Iran lawyer#North Shore Iranian Lawyer#North Shore lawyer and notary#North Shore Lawyers#North Shore Lawyers and Notaries Public#North Shore Licensed lawyer#North Shore litigation lawyer#North Shore Notary Public#North Shore spousal support lawyer#North Shore Wills lawyer#Registration of Companies on the North Shore#Registration of logo#Registration of Trademark#Samin Mortazavi#Seyed Samin Mortazavi#smortazavi

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

See Canada Through Fresh Eyes on a First Nations Tour

New Post has been published on https://mediafocus.biz/see-canada-through-fresh-eyes-on-a-first-nations-tour/

See Canada Through Fresh Eyes on a First Nations Tour

Growing up on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, I located it smooth to mock traffic from abroad. “This vicinity,” they had whispered. “I can go swimming in the morning, skiing within the afternoon, then kayak domestic for dinner.” The perspectives, the panorama, the wildlife — that was the refrain. Even in the cities, the surroundings dominates. On any clean afternoon, appearance up from the streets of downtown Vancouver and you will see the snow-capped North Shore mountains sparkling crimson, an ostentatious display of herbal splendor so commonplace that maximum citizens barely take be aware.

There have been instances while visitors’ compliments sounded like admiration for a -dimensional backdrop. But B.C. Is a complex region, especially in terms of its aboriginal communities. With a population of just over 4.5 million, the province is domestic to around 230,000 aboriginal humans from 203 special First Nations, who among them speak 34 languages and 60 dialects. Today, those agencies stay lifestyles of ostensible equality, but centuries of oppression — stated in official circles as “alien modes of governance” — started a cycle of social devastation that hasn’t yet been completely resolved. In many Aboriginal communities, poverty, homelessness, and substance abuse nonetheless loom massive.

Indeed, residents of B.C. Live in a province of uneasy contrasts. My village on the island became a haven of center-magnificence comfort, bordered via the poverty of a First Nations reserve. As a toddler, I walked down the stony seaside and saw wealth and privilege provide the way to sudden worry. This, I changed into advised once, turned into my first experience of apartheid.

As an adult, I spent more than 15 years residing out of doors Canada, and sometimes I might catch a glimpse of the ancient cedars and airborne orcas used to put it on the market my home province. I puzzled which B.C. The site visitors have been coming to look. Was it feasible to engage with the region’s complexities and to approach its original citizens in a way that went past the superficial?

If I was asking that query of others, I found out, I first had to solve it myself. So I deliberate a experience that took me from mid-Vancouver Island, the land of Snuneymuxw and Snaw-Naw-As First Nations, north to Port Hardy, then directly to the remote, fog-shrouded islands of Haida Gwaii, domestic of the formidable Haida people, to find out whether it becomes feasible for a vacationer to absorb B.C.’s nuanced human tales whilst still retaining the one’s forests and snow-capped peaks in view.

Port Hardy, a beach town of 4,000 humans at the northern tip of Vancouver Island, is today referred to as a vacation spot for typhoon-watchers, sports fishermen, and hikers, even though the location has retained a plaid-shirt solidity that reflects its beyond as a middle for logging and mining. Outside the airport, I changed into met by Mike Willie of Sea Wolf Adventures. Willie is a member of the Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw First Nation, and he runs what he calls boat-based cultural tours across the waters into the Kwakwaka’wakw territory. That consists of the village of Alert Bay, the Namgis Burial Ground, with its totem and memorial poles, and the unpredictable waters close by. He goes from Indian Channel as much as Ralph, Fern, Goat, and Crease Islands, and as a long way north as the Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw territory, also referred to as the Great Bear Rainforest — a 25,000-square-mile nature reserve this is domestic to the elusive white “spirit” endure.

I’d organized to tour with Willie to the U’mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay, in addition to Village Island, the website of an infamous potlatch — a ceremonial dinner and gifting ceremony thru which First Nations chiefs might assert their reputation and territorial rights. (Potlatches had been banned in 1884 by means of the Canadian government, considering that they were contrary to “civilized values.” The ban became repealed in 1951.) As we activate, Willie told me about the site. “The potlatch changed into an opportunity to reaffirm who you had been,” he said. “It turned into a manner to get thru the tough winters. We accumulated: that became the drugs.”

Willie took me to my lodgings, a beachfront cabin at the Cluxewe Resort outside the logging city of Port McNeill. The Inn was secure however clearly designed to propel traffic outdoors. (A word inner my room reminded guests to please refrain from gutting fish at the porch.) I spent the evening reading, observed by means of a soundtrack of waves sweeping the beach outdoor, and the next morning, I took a walk alongside the stretch of pebbly Pacific shore in the front of my cabin. I desired to reacquaint myself with the past, inhale the moisture inside the air, smell the cedar. Up above, unhurried eagles swooped, exuding a proprietary air as they circled and fell and turned around again.

As I walked, it struck me that this seaside, like so many others, has been domestic to the Kwakwaka’wakw humans for lots of years. Canada, on the other hand, turns a trifling 150 this 12 months, and it appeared to be an amazing time to reflect on the kingdom’s progress. The contrasts and contradictions I found in B.C. Are gambling out on a countrywide scale. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, installation as a response to the abuse inflicted on indigenous college students in residential faculties, concluded its findings in December 2015, attempting to redress the legacy with ninety-four Calls to Action. The Idle No More motion has been making use of the spirit of Occupy to the problems facing First Nations through a series of rallies and protests.

Meanwhile, in B.C., tourism sales are expected to double within the subsequent two decades, with the aboriginal zone playing a starring position. (This yr it’s miles forecast to herald $68 million.) Something is taking place. This is not approximately “having a moment”; moments recede. This is a long slog for admire, an attempt to trade the way Canadians view the Aboriginal network’s land and lives.

In preparation for our experience to Alert Bay, Willie drove me into Port McNeill for a breakfast of eggs and bacon at an unpretentious area referred to as Tia’s Café. The city is small, so it wasn’t a massive marvel when Willie’s uncle Don wandered in. He informed us there was pleasure up in Kingcome, web page of the circle of relatives’ First Nations network. He said the policies, or lichens — smelt fish used for making oil — had arrived, and the villagers were out the fishing remaining night.

“Sea lions were noticed within the river,” Uncle Don said. “It’s peculiar to look them up that high.”

“And there may be exhilaration?” Willie requested.

Don raised an eyebrow. “Oh, certain.”

Willie got here to the guiding business in a natural way. In 2013, he began a water-taxi carrier among Alert Bay and neighboring Telegraph Cove, and en route he’d inform passengers about Kwakwaka’wakw lifestyles. Back then, the creaky remains of the notorious First Nations residential faculty in Alert Bay, which housed Aboriginal children from 1929 to 1975, had been nevertheless standing, and site visitors had been every so often moved to tears whilst he told them approximately the abuses that took place there. But there has been a lot greater: the totem-pole ceremony; the loss of life protocol; family crests. You can study a totem pole and appreciate the art, Willie defined to his passengers, but genuine appreciation comes from an understanding of its which means. As he placed it, “Wouldn’t you as an alternative see B.C. Through fourteen thousand years of history?”

Inside the U’mista Cultural Centre, in Alert Bay, which became set up to protect the history of the Kwakwaka’wakw network, I walked some of the masks — a collection of painted wooden beaks and faces peering forth into the dimly lit exhibition room. In this tradition, mask function not best as the ornament but additionally as a shape of historical and prison documentation. They additionally serve as the gear of social practice. Willie and I stopped in the front of Gwalkwamł, or the Deaf Man, a one-eared mask with a downturned mouth and wisps of black horsehair. “It shows a head chief of an extended family,” Willie defined. “He failed to need to hold a potlatch, and the clansmen were not glad about that, so they killed him.” The masks, worn at some stage in retellings of the tale, became a caution.

Back at the dock in Alert Bay, brightly colored homes huddled alongside boats ranging from weathered to freshly painted. As we left the harbor, Willie supplied me pâté of untamed sockeye salmon from the Nimpkish River, and I ate as much as I ought to before we started out cresting waves. Over the roar of the engine, I asked him why interacting with vacationers became important. “We want to be vocal,” he stated. “We want to talk about our evolution and bring humans toward our reality.” Oral-history cultures, I turned into reminded, need audiences. “Every time we tell this truth,” he said, “it is strengthened.”

We pulled as much as a red-ocher pictograph on a rock face on Berry Island, and Willie cut the engine. The photo depicted Baxbakwalanuksiwe’, an essential figure in Kwakwaka’wakw spirituality. Bestowed with the strength to convert himself into multiple guy-eating birds, and decorated with mouths throughout his body, his imposing presence at the rock meant burial websites were close by.

0 notes

Link

by Joshua Ostroff Aug 1, 2017

On Mar. 12, 1862, the San Francisco steamer Brother Jonathan pulled into the boisterous colony of Vancouver Island, a former Hudson’s Bay Company fur trading post that had exploded in population after a mainland gold rush.

“The town was taken completely by surprise,” wrote the British Colonist newspaper, reporting that along with merchandise and mules, the ship carried 350 passengers to Victoria—home to 4,000 to 5,000 colonists, with slightly more Indigenous people from various nations camped nearby for trade and work. Most of the passengers were heading to a new strike on the Salmon River.

But along with his pickaxe and gold pan, one of these miners brought another piece of unexpected cargo: smallpox.

The man was quarantined. But the Colonist noted that, without preventive measures, “we fear that a serious evil will be entailed on the country.” And the measures the colonial government chose—limited vaccination efforts, and declining to try a general quarantine, which would have kept the crisis localized—wound up leading to an epidemic when police emptied the camps at gunpoint, burned them down, and towed canoes filled with smallpox-infected Indigenous people up the coast.

Over the next year, at least 30,000 Indigenous people died, representing about 60 per cent of the population—a crisis that left mass graves, deserted villages, traumatized survivors and societal collapse and, in a real way, created the conditions for modern-day British Columbia. Less than a decade before B.C. became Canada’s sixth province, the colonial response to this crisis formed the basis for the fraught relationship between First Nations and government and sparked the question of what this problematic past means for its future.

“The smallpox epidemic … it changes everything in British Columbia,” says John Lutz, the head of the University of Victoria’s history department and an Indigenous-settler relations specialist. “The citizens of Victoria, one could say, panicked. Or, one could say, with a less charitable view, that they deliberately drove the Indigenous people out of town, and that spread the disease back to their home communities up and down the coast.”

It was a betrayal that hasn’t been forgotten by many Indigenous people. “The sad thought is, if they had contained those people who contracted smallpox within the Victoria area, the Indigenous population would be far, far higher today,” says Marianne Nicholson, a Victoria-based artist and anthropology Ph.D from the Dzawada’enuxw Nation of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw whose video installation about the epidemic, There’s Blood In The Rocks, is being exhibited at Victoria’s Legacy Art Gallery until September. Nicholson’s nation’s population fell to 1,500 from 10,000, and has since rebounded to 7,000.

“The colonial authorities … knew that would spread smallpox throughout British Columbia,” she says. “That was an act of genocide against Indigenous people. … At that point in time the [government] wanted to be able to claim those lands without having to compensate or recognize Indigenous title.”

That thinking—that the colonial response was part of an active land grab as opposed to a tragedy they made much worse and took advantage of—is pervasive. And while there is no concrete evidence of it, historian Robert Boyd did argue in his landmark book The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence that “the Whites knew” the epidemic was avoidable, and that it “paved the way for the colonization of their lands by peoples of European descent.” The Colonist even reported at the time that First Nations were worried that Governor James Douglas “was about to send the small pox among them for the purpose of killing off the tribe and getting their land.” (Douglas dismissed this at the time as a hoax.)

Taken together, the smallpox response, the creation of the residential school system, and a ban on the potlatch—a tradition that helps pass on oral histories—have been seen by Indigenous people as efforts to force them to “accept the colonial grand narrative that British Columbia acquired Indigenous lands fairly and in a legal manner,” says Nicholson.

The 1862 smallpox epidemic wasn’t the first to rage across the region post-contact, but it was the first in the colonial era. “The significance of the 1862-1863 crisis lies in the presence of a rapidly expanding white population—this was the factor that was different,” says Maureen Atkinson, a historian from Terrace, B.C. “If the Fraser River gold rush and then the Cariboo gold rush had not happened then I think there might have been a different response, perhaps, in the colonial government’s approach to Indigenous peoples.”

These newcomer numbers surged as Indigenous populations fell by as much as 90 per cent in some areas. Geographer Cole Harris reports in The Resettlement of British Columbia that by 1863 in southeastern B.C., large areas were “almost completely depopulated,” and that census-takers on the north coast found the Haida had fallen from a pre-epidemic count of 6,607 people to only 829 in 1881.

Whether or not smallpox began as a colonial conspiracy, settlers started occupying the flat, fertile land that was left seemingly abandoned as devastated Indigenous communities consolidated with hopes of later returning home, says Lutz. “A lot of First Nations village sites were lost to that.”

A belief in terra nullius, or the settlement of “empty land,” spurred land commissioner Joseph Trutch in 1864 to refuse recognition of Indigenous title, kiboshing treaty-making and reducing reserves mapped out pre-epidemic by 92 per cent. “The Indians have really no rights to the lands they claim,” he argued, doling it out instead to settlers, miners and loggers.

That’s why, unlike the rest of Canada, the bulk of B.C. is built on disputed, unceded land; there are almost no treaties establishing rights. In accordance with the Royal Proclamation of 1763, Governor Douglas had earlier signed 14 treaties on Vancouver Island until a funding conflict between the Crown and the colony postponed progress and, in the face of the smallpox crisis, treaties became a low priority. “There was this pervasive belief that this was a dying race and the smallpox epidemic seemed to confirm that. So essentially treaty-making was abandoned as a result,” says Lutz.

One Indigenous nation, though, did fight back in defence of its land. In 1864, the Tsilhqot’in declared war after being threatened with smallpox by the foreman of a road being built through their territory. This battle, the Chilcotin War, ended with the hanging of six chiefs, an act that then-premier Christy Clark apologized for in a 2014 speech that acknowledged that “there is an indication [smallpox] was spread intentionally.”

With First Nations still too weakened to resist, post-Confederation B.C. continued the colonial policy of Indigenous erasure even as “numbered treaties” were being negotiated in other new Canadian provinces.

But denying land title didn’t extinguish it, according to a 1973 Supreme Court ruling on a century-long treaty effort by the Nisga’a, which was only finalized nearly 30 years later. That inspired the B.C. Treaty Process in the 1990s, which has proven similarly glacial, partly because it doesn’t put jurisdiction truly on the table.

So the Tsilhqot’in lawyered up. And in 2014, the Supreme Court gave them title to 1,900 square kilometres near Williams Lake, setting a precedent in a province where most land is similarly contested.

“If one applies generally the principles of the Tsilhqot’in title case, British Columbia is a province unlike the rest in that it owns comparatively little of its natural resources,” says Tom Swanky, a Quesnel, B.C. author of books that allege that the epidemic was a “war of extermination” for land.

Without smallpox, B.C. would look like the numbered treaty provinces, Swanky believes. “The Crown eventually would have purchased native title, little by little or territory by territory, as needed and, under the Canadian system, the province now would have had some more understandable claim to resources.”

While Indigenous consent is an issue across Canada—the Supreme Court recently ruled on the Crown’s duty to consult Indigenous people on development projects—few First Nations have as much leverage today to address environmental and economic concerns as those in B.C. because treaty-less land is in legal limbo; governments can still overrule opposition, but now must prove “development is pressing, substantial and meets the Crown’s fiduciary duty.”

“The thing that bothers me the most as a descendant of this history is how unjust all of it is,” Nicholson says, explaining how her smallpox-reduced Kingcome Inlet community—“where we lived for thousands of years”—saw their land taken. But, she adds, “Indigenous peoples, while suffering tremendous losses, still survived. And their land title remains intact, which continues to be a problem for British Columbia and the resource-extractive projects they wish to push through within those contested lands.”

But with B.C.’s new Green-supported NDP government committing to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Tsilhqot’in Supreme Court decision, perhaps justice will one day be served. At the very least, we should acknowledge that the province we know today was, by many accounts, founded on the back of a potentially avoidable epidemic.

0 notes

Text

B.C. First Nation sues feds over Atlantic salmon farming in Pacific waters

Dzawada’enuxw First Nation alleges 10 Atlantic salmon fish farms in the waters of their territory infringe on their Aboriginal rights to harvest eulachon and wild salmon. They allege farms threaten those species by exposing them to viruses and parasites and want them gone.

Original Story: http://bit.ly/2RqZUFi

from Blogger http://bit.ly/2TOmNPN

0 notes

Text

B.C. First Nation sues feds over Atlantic salmon farming in Pacific waters

Dzawada’enuxw First Nation alleges 10 Atlantic salmon fish farms in the waters of their territory infringe on their Aboriginal rights to harvest eulachon and wild salmon. They allege farms threaten those species by exposing them to viruses and parasites and want them gone.

Original Story: http://bit.ly/2RqZUFi

0 notes

Text

BC First Nation Files Aboriginal Title Claim Challenging Fish Farms in Their Territory

BC First Nation Files Aboriginal Title Claim Challenging Fish Farms in Their Territory

from Warrior Publications

The Dzawada’enuxw First Nation of Kingcome Inlet filed a claim of Aboriginal title in British Columbia’s Supreme Court that affects ten fish farms in their traditional territory that they say are operating without their consent.

“We have been saying no for 30 years,” says Lindsey Mae Willie of Dzawada’enuxw First Nation. “We have always said no and they just plunked…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note