#Dizzy Gillespie Big Band

Text

1988 - Big bands at North Sea Jazz Festival (Den Haag / La Haye)

Gerry Mulligan, Dizzy Gillespie, Illinois Jacquet

#jazz#poster flyer#big band#gerry mulligan#dizzy gillespie#illinois jacquet#1988#jazz festival#north sea jazz festival

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

During her time with Dizzy Gillespie’s Progressive Big Band, brilliant arranger and trombonist Melba Liston completed tasks considered to be appropriate for her gender such as sewing and doing the other hand members’ hair.

Randy Westin said of Liston: “She was simply a genius who had a very original way of writing arrangements.”

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ernie Wilkins: The Unsung Hero of Jazz Arranging

Introduction:

Ernie Wilkins is a name that may not be as immediately recognizable as some of his contemporaries, but his contributions to jazz are profound and far-reaching. An accomplished saxophonist, composer, and arranger, Wilkins’ work has been instrumental in shaping the sound of some of the most iconic jazz ensembles. From his early days with the Count Basie Orchestra to his prolific work…

#Almost Big Band#Bent Jaedig#Count Basie#Count Basie Orchestra#Danish Radio Big Band#Dizzy Gillespie#Earl Hines#Ed Thigpen#Ella Fitzgerald#Ernie Wilkins#Harry James#Jazz Composers#Jazz History#Jazz Saxophonists#Jesper Thilo#Kenny Drew#New Testament#Tommy Dorsey

1 note

·

View note

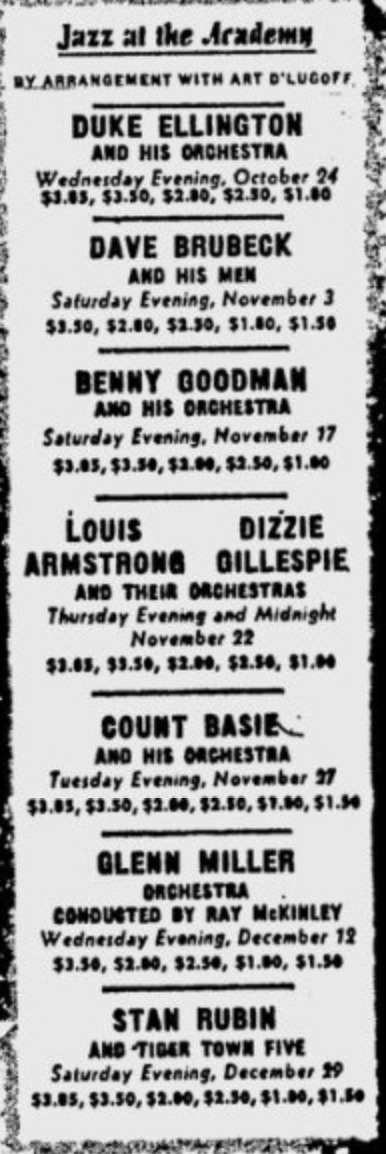

Photo

This lineup!

Brooklyn Academy of Music ad

Village Voice, October 1956

#Duke Ellington#Dave Brubeck#Benny Goodman#Louis Armstrong#Dizzie Gillespie#Count Basie#Glenn Miller#Stan Rubin#Jazz#Big Band#old new york#Brooklyn#BAM#Brooklyn Academy of Music#1956#50s#50sjazz

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daily Listening, Day #116 - April 25th, 2020

Album: Dizzy Gillespie At Newport (Verve, 1957)

Artist: Dizzy Gillespie

Genre: Bebop, Big Band

Track Listing:

"Dizzy's Blues"

"School Days"

"Doodlin'"

"Manteca"

"I Remember Clifford"

"Cool Breeze"

Favorite Song: "I Remember Clifford"

0 notes

Text

Today We Honor Lee Morgen

Lee Morgan was one of hard bop’s greatest trumpeters, and indeed one of the finest players of the ‘60s. An all-around master of his instrument modeled after Clifford Brown, Morgan boasted an effortless, virtuosic technique and a full, supple, muscular tone that was just as powerful in the high register.

His playing was always emotionally charged, regardless of the specific mood: cocky and exuberant on uptempo groovers, blistering on bop-oriented technical showcases, sweet and sensitive on ballads.

In his early days as a teen prodigy, Morgan was a busy soloist with a taste for long, graceful lines, and honed his personal style while serving an apprenticeship in both Dizzy Gillespie’s big band and Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

Due to the crossover success of “The Sidewinder” in a rapidly changing pop music market, Blue Note encouraged its other artists to emulate the tune’s “boogaloo” beat. Morgan himself repeated the formula several times with compositions such as “Cornbread” (from the eponymous album Cornbread) and “Yes I Can, No You Can’t” on The Gigolo.

CARTER™️ Magazine

#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#historyandhiphop365#cartermagazine#carter#leemorgan#jazz#blackhistorymonth#blackhistory#staywoke

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

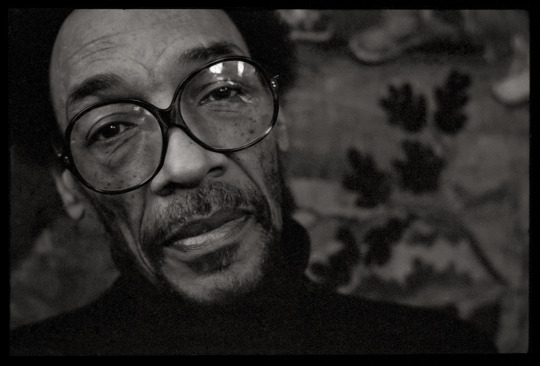

SAM RIVERS, Toronto 1989

That Sam Rivers was born just over a hundred years ago is a reminder that the avant-garde tradition in jazz is an old one. The son of a gospel singer, the Oklahoma-born Rivers moved to Boston where he studied at the Conservatory, which helped build his command of music theory and composition that would make him stand out in his career. Briefly a member of Miles' Davis legendary quintet, he recorded his first album for Blue Note Records in 1964, working as a sideman on albums by Blue Note artists such as Tony Williams, Andrew Hill and Larry Young. His work would often straddle bebop and free jazz, and he would perform and record with influential artists such as Anthony Braxton, Dave Holland and Cecil Taylor. In the '70s he and his wife Beatrice opened their NYC loft to performances, and Studio Rivbea became the most famous of the venues in the city's "loft scene".

I met and photographed saxophonist and flautist Sam Rivers when he came through town with Dizzy Gillespie's Big Band - the trumpeter hadn't been part of the jazz avant-garde for many years, but he frequently hired musicians like Rivers for his band. (Latin jazz trumpet star Arturo Sandoval was also in Gillespie's band when I saw them at Berlin, a club in midtown Toronto.) The perk with playing with Gillespie is that touring conditions were more than decent, and after I talked Rivers into doing a shoot with me, he told me to meet him at the old Sutton Place, a luxury hotel downtown where I did a lot of shooting, as it was the home of the film festival and frequently used to put up big stars by the movie and record companies.

I found a decent spot for my shoot with Sam Rivers in the mezzanine lobby of the Sutton Place, where an antique couch had been placed in front of a big tapestry. (The spot would become a favorite one for shoots.) The light wasn't brilliant but I put high speed Kodak film in my camera and managed to elicit a good range of expressions from Rivers as I coaxed him through our brief but - in hindsight - very productive portrait session. My live photos of Rivers playing in Dizzy Gillespie's band weren't as successful, as the spotlights were mostly on Dizzy and Rivers stuck to his spot downstage from the bebop star. Rivers and his wife moved their Studio Rivbea performing space to Florida in the '90s, where he was able to put together a larger band, and his private recordings have been mined to produce a series of records documenting his work at Studio Rivbea. Sam Rivers died of pneumonia in Florida in December of 2011.

#portrait#portrait photography#photography#black and white#film photography#some old pictures i took#early work#musician#sam rivers#jazz#jazz musician#avant garde#pentax spotmatic

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think, in general, the punk community is really bad at distinguishing between punk (ethos), punk (aesthetic), and punk (music). I saw a post the other day circulating in punk circles that was mocking someone for saying Mr. Rogers was punk. That person was right! Mr. Rogers practiced radical kindness in a way that was contrary to how most of our society is. That’s why he’s still beloved. He definitely wasn’t punk (aesthetic) or punk (music) but he’s a hell of a lot more punk than some douchebag in a battle jacket singing about how much he hates his girlfriend.

Similarly, a lot of people seem to think that punk encompasses rebellion as a general concept, regardless of what you’re rebelling against, and that’s nonsense. Rebelling at your mom telling you to go to bed when you’re 8 isn’t punk. Rebelling against racial or gender equality isn’t punk. What you believe and how you express it matters.

While we’re on the topic, punk fans often wanna draw these really tiny circles around what is or what isn’t punk (music). But the fact of the matter is musicologically speaking, blink 182, Ramones, Green Day, MCR, Fallout Boy, The Clash, and yes, even Reel Big Fish and Less than Jake, they’re all punk bands. In much the same way that Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman, Herbie Hancock, and Dizzy Gillespie are all jazz artists. They all come from different periods, and follow distinct and traceable patterns of genre diversion. Sorry, but Punk is a big branch of music on par with Rock, even as it’s descended from it.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dexter Gordon played the tenor saxophone. His sound was big and unapologetic. You could feel his warmth and power at the same time. The musician was imposing in stature too. 6 foot 6 inches of a man.

He played ferocious bebop when he started. However, like Miles Davis, he decided to explore slower and longer sounds, especially when he lived in Europe. He stayed there 14 years.

I love his album “Our man in Paris” (1963), especially ��A Night in Tunisia”, co-wrote by Dizzy Gillespie and Frank Paparelli. Dexter Gordon is among great friends, Kenny Clarke on drums and Bud Powell on piano. These are exceptional musicians.

A sophisticated player, Dexter Gordon is at his best in small bands. “Go!” and “A Swingin’ Affair” (1962) are also great albums. Sonny Clark on piano is trading great vibes with Dexter Gordon.

Dexter Gordon jouait du sax ténor. Son son est imposant et remplit l’oreille. Vous pouvez sentir sa chaleur et sa puissance. Le musicien était grand de taille dans la vie. 2 mètres de haut. Il jouait du bebop avec fureur au début de sa carrière. Mais, comme Miles Davis, il décida d’explorer les autres styles et joua plus lentement, surtout lorsqu’il s’est expatrié en Europe. Il y est resté 14 ans.

J’aime son album « Our man in Paris » (1963), surtout « A Night in Tunisia” que Dizzy Gillespie a écrit avec Frank Paparelli. Dexter Gordon est avec des amis, Kenny Clark à la batterie, Bud Powell au piano. Ce sont des musiciens exceptionnels.

Dexter Gordon est un joueur sophistiqué qui brille surtout dans les petits orchestres. « Go! » et « A Swingin’ Affair » (1962) sont aussi de très bons albums. Sony Clark au piano échange brillamment avec Dexter Gordon.

Pic by Francis Wolff

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carmen Mercedes McRae (April 8, 1922 – November 10, 1994) was a jazz singer. She is considered one of the most influential jazz vocalists of the 20th century and is remembered for her behind-the-beat phrasing and ironic interpretation of lyrics.

She was born in Harlem. Her father, Osmond, and mother, Evadne (Gayle) McRae, were immigrants from Jamaica. She began studying piano when she was eight, and the music of jazz greats such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington filled her home. When she was 17 years old, she met singer Billie Holiday. As a teenager, she came to the attention of Teddy Wilson and his wife, the composer Irene Kitchings. One of her early songs, “Dream of Life”, was, through their influence, recorded in 1939 by Wilson’s long-time collaborator Billie Holiday. She considered Holiday to be her primary influence.

She played piano at an NYC club called Minton’s Playhouse, Harlem’s most famous jazz club, sang as a chorus girl, and worked as a secretary. It was at Minton’s where she met trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, bassist Oscar Pettiford, and drummer Kenny Clarke, had her first important job as a pianist with Benny Carter’s big band (1944), worked with Count Basie (1944) and under the name “Carmen Clarke” made her first recording as a pianist with the Mercer Ellington Band (1946–47). But it was while working in Brooklyn that she came to the attention of Decca’s Milt Gabler. Her five-year association with Decca yielded 12 LPs.

She sang in jazz clubs across the world—for more than fifty years. She was a popular performer at the Monterey Jazz Festival, performing with Duke Ellington’s orchestra at the North Sea Jazz Festival, singing “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore”, and at the Montreux Jazz Festival. She left New York for Southern California in the late 1960s, but appeared in New York regularly, usually at the Blue Note, where she performed two engagements a year through most of the 1980s. She collaborated with Harry Connick Jr. on the song “Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone”. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lee Morgan Was One Of Jazz’s Biggest Stars — Until His Wife Shot Him In The Middle Of A Show

Lee Morgan's wife saved his jazz career and his life. And then she ended it.

Lee Morgan in 1959

Lee Morgan was a brilliant trumpet star and was recognized for his talents by the time he was a teenager. By 1960, he had recorded with legendary jazz musicians like John Coltrane, Tina Brooks, Dizzy Gillespie, and Art Blakey.

But the downside to a rising artist’s life is the drugs and alcohol that are so easily accessible. Lee almost gave into them, but a woman named Helene Moore saved him.

Lee Morgan could have gone on to produce many more jazz records. Unfortunately, his bourgeoning career would be tragically cut short. In 1972, after getting into an argument, Morgan was shot by his wife in the middle of a show. Ironically, that woman who saved him would ultimately cause his demise.

Lee Morgan Discovers Jazz

Born on July 10, 1938, in Philadelphia, Lee Morgan grew up loving jazz. He was the youngest of four children to Otto Ricardo and Nettie Beatrice, and the family moved to New York City after he was born.

Morgan was interested in many instruments including the vibraphone, the alto saxophone, and the trumpet. But he took a particular liking to the trumpet and when he turned 13, he was given one as a gift from his sister. After taking lessons with influential jazz musicians like Clifford Benjamin Brown, his style and talent developed rapidly.

By age 15, Morgan was already performing at clubs on the weekends. He soon moved on to record with well-known bands, joining Dizzy Gillespie’s Big Band when he was just 18 years old.

In 1957, Morgan recorded on John Coltrane’s Blue Train, which elevated him to a level of prominence in the jazz world, a level he remained at until his death.

He wound up recording on 25 albums for the Blue Note, a notable jazz record label. After playing with other bands like Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, Morgan tried his hand as a solo trumpeter and composer.

Morgan’s Fast-Paced Life Takes A Turn

Lee Morgan’s lifestyle came with a side of adventure and risk. The jazz scene was loud, fast, and wild. It revolved around the night, which is when the music would come alive.

It’s also when Morgan and his fellow musicians would race their cars down the city streets, drink strong cognac cocktails, and engage in many sexual escapades.

Wayne Shorter, a notable saxophonist who hung around and played with Morgan in the 1960s recalled, “I would drink and have like a think veil around me– that’s my space, my little dream space– and we would play.”

Drugs were a big part of the scene as well. Blakey introduced Morgan to heroin in the early 1960s and he soon became addicted. The habit had a noticeable effect on his playing as not only did he not sound as good, but he became flakey.

One time while he was high, Morgan started dozing off near a radiator. He wound up burning the side of his head, leaving him with a scar and a bald spot for the rest of his life.

Morgan’s heroin addiction lasted for years and reached the point where he’d say he’d rather do drugs than play music.

Lee Morgan Meets Helen Moore

Then, in 1967, after hardly playing anymore and having pawned his trumpet, Lee Morgan met Helen Moore.

Moore was popular in jazz circles and was given the nickname “the little hip square.” Known as “Helen’s Place,” her apartment served as a refuge for all the musicians after the clubs closed down. It was also where struggling musicians and addicts would go to get fed and keep warm.

So on a cold night in 1967, Lee Morgan came stumbling in. In the biography, The Lady Who Shot Lee Morgan, he’s described as “raggedy and pitiful” when he came in. But for some reason, Moore said, “my heart just went out to him.” She made him her project.

“She was a sucker for people who were suckers,” said Larry Reni Thomas, the author of The Lady Who Shot Lee Morgan.

Moore got Morgan’s trumpet back for him and helped him get clean. Though they were never legally married, Moore became his common-law wife and took his name. She got his career back on track too, booking him gigs as he worked to grow into the great musician he was capable of being.

When he started playing again, the shows were some of his most daring and experimental. He became a must-see at clubs around New York City.

It would seem like a happy ending. Except that Lee Morgan began seeing another woman, Judith Johnson.

The Shot Heard ‘Round The Jazz World

On Feb. 19, 1972, on a cold, snowy Tuesday night, Lee Morgan was playing a show at the popular jazz club Slugs’ Saloon in the East Village of Manhattan.

Though the specific details of the night haven’t been definitively confirmed, it’s alleged that Johnson was there that night, watching Morgan perform.

Unfortunately, so was Helen. Feeling betrayed after everything she had done for him, the two got into an argument between sets. She left the club and came back with a gun. In a jealous rage, while Morgan was on stage during the second act, she shot him in the chest.

Due to the snow, the ambulance was slow to arrive and by the time they got there, the 33-year-old trumpet player had bled to death.

The murder shocked the jazz community and all those close with the Morgans.

Helen Morgan was arrested and released on parole after serving just a short time. She moved back to her hometown of Wilmington, North Carolina in 1978 and died in 1996 following heart problems.

As for Lee Morgan, he led a short life that was filled with drama and struggle. But it was also filled with music that would influence generations of jazz artists to come. Even today, he’s considered one of the greatest trumpet players of the 20th century.

By Kara Goldfarb in ati-All That's Interesting

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Aziraphale and “bebop:”

I’ve seen GO fans expressing confusion about Aziraphale’s animosity towards bebop, so I wanted to chime in about what I think is going on.

Bebop represented a sharp break from the more melodic big band/swing/dance orchestra styles of jazz that preceded it. It is a much more purely improvisational form of music, and it sounded jarring and discordant to people who were used to more traditional styles of jazz and pop. It was considered “musician’s music,” more designed to show off virtuosity than to be accessible to the listener.

Some of the older generation of jazz musicians were pretty hostile to bebop when it began to emerge in the early-mid 1940s. See, for example, the notorious clashes between Cab Calloway and Dizzy Gillespie when young Dizzy was cutting his teeth on the super edgy modern style during his time in Cab’s band. A lot of listeners must have reacted the same way at the time.

Aziraphale objects to bebop because it is jarring and new and bizarre to his ear. When your favorite “modern” music is stuff like the New Mayfair Dance Orchestra, bebop is going to sound weird as fuck. And because he is so slow to adapt to the way the world changes around him, any type of music from the last century or so that sounds jarring and new and weird to him (i.e., most of it) gets lumped into the category of “bebop.” It’s the eldritch immortal being equivalent of “Darn kids and their loud rock and roll music!”

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hot Tuna Acoustic at Natalie’s Grandview, Columbus, Ohio, July 11, 2024

Just how long have Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady been playing together?

So long that the old friends took a moment toward the end of their sold-out, Columbus, Ohio, show to reminisce about their first band, Jefferson Airplane, opening for Dizzy Gillespie on New Year’s Eve 1965.

So while it might be reasonable to assume the men - known together as Hot Tuna - see their work as a grind, the opposite is true. The July 11 performance inside Natalie’s Grandview marked their first gig in five months, a big gap they were happy to bridge, according to their between-song chatter and the undefinable extra spark that permeated the music and belied the octogenarian reality of the band.

At 83, Kaukonen remains a nimble finger-picking acoustic guitarist capable of subtle, quiet playing and aggressive, loud blues. Electric bassist Casady, 80, meanwhile, is a lead player on a rhythm instrument who consistently finds the sweet spot between support and showcase. Together, they’re as close to one musician as two musicians can be even as they’re walking down the same musical paths with very different gaits.

Opening with “Ain’t in No Hurry” and choosing 18 songs on the fly from a master list, Kaukonen and Casady played familiar chestnuts from their repertoire including “Death Don’t Have No Mercy,” “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out” and “Hesitation Blues;” newer, lighthearted additions such as “Where Have My Good Friends Gone;” and closed after 100 minutes with “True Religion.”

The musical closeness Hot Tuna share within the music is also evident outside of it, something easy to pick up on in a venue so intimate, the face of Casady’s smart watch was visible from the audience. As the friends and colleagues continued their six-decade-plus conversation, they exchanged knowing glances, beaming smiles and inside signals known only to them but visible to all. Often lost in the music, Casady would mouth the words Kaukonen sang, move his lower body to his own low notes and throw his head back in aural ecstasy as Kaukonen riffed away in the chair beside his.

“It’s been swell, Jack,” Kaukonen said through a wide smile that showed his gold tooth sparkling in the stage lights.

And it was that. And more.

Grade card: Hot Tuna Acoustic at Natalie’s Grandview, Columbus, Ohio - 7/11/24 - A

7/12/24

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Teddy Hill: Architect of Jazz Evolution

Introduction:

Teddy Hill, born one hundred and fourteen years ago today on December 7, 1909, in Birmingham, Alabama, left an indelible mark on the landscape of jazz. An American big band leader, instrumentalist, and the visionary manager of Minton’s Playhouse, Hill’s multifaceted contributions to jazz have reverberated through time. This article delves into the life, career, and enduring legacy…

View On WordPress

#Beatrice Hill#Bebop#Big Band Jazz#Bill Coleman#Bonnie Davis#Dizzy Gillespie#Frankie Newton#George Howe#Jazz History#Kenny Clarke#Luis Russell#Melba Moore#Minton&039;s Playhouse#Roy Eldridge#Swing#Teddy Hill#Thelonious Monk#Whitman Sisters

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

recent album listens

i can actually listen to music while i work again, it's been over a year of not being able to swing it. anyways, some recent first-time listens the last couple of months

my ancestors - chrissy zebby tempo & ngozi family (1976, psych rock)

panoramic feelings - alessandro alessandroni (1971, library music / lounge)

small medium large - sml (2024, nu jazz)

keesh mountain - wombo (2021, post-punk / slacker rock)

we be all africans - idris ackamoor & the pyramids (2021, spiritual jazz / afro-jazz)

blue hour - stanley turrentine with the 3 sounds (1960, soul jazz / hard bop)

shadowfax - shadowfax (1982, new age / jazz fusion)

for the recently found innocent - white fence (2014, garage rock / psych rock)

seven waves - ciani (1982, progressive electronic / new age)

the president plays with the oscar petersen trio - lester young (1956, recorded 1952, bebop / cool jazz)

the very best of bird - charlie parker (1977 released compilation, jazz / bebop)

big band - charlie parker (1954 released compilation, cool jazz / big band)

i just dropped by to say hello - johnny hartman (1964, vocal jazz / standards)

john coltrane and johnny hartman (1963, vocal jazz / standards)

everybody split - possible humans (2019, indie rock / jangle pop)

walt wolfman - richard swift (2013, garage rock)

ballet of apes - brigid dawson & the mothers network (2020, psych folk / singer-songwriter)

jaguar sound - adrian quesada (2022, psych rock, jazz-funk)

miles ahead - miles davis + 19 (1957, cool jazz)

blow out - john carroll kirby (2023, jazz-funk / nu jazz)

birks' works - dizzy gillespie (1957, big band / bebop)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

DON BYRON, AGENT PROVOCATEUR

"Nobody calls up Eric Clapton and says, 'Yo, Clapton, you're the white guy that plays all that black {expletive}, right? Why don't you come play at a rally?' What makes them think they can do that to me?"

- Don Byron

Né le 8 novembre 1958 à New York, Donald Byron était issu d’une famille musicale. Son père, Donald Byron Sr., était postier et jouait de la contrebasse dans des groupes de calypso. Sa mère Daisy White travaillait comme téléphoniste et était aussi pianiste. Sous l’influence de sa mère, Byron avait été initié à une musique diversifiée allant de la musique classique à la salsa et au jazz. Exposé à la musique de Dizzy Gillespie, du percussionniste cubain Machito et de Miles Davis durant ja jeunesse, Byron avait également assisté à des spectacles de ballet et de musique classique.

Même si le fait d’avoir été familiarisé avec une musique aussi éclectique l’avait aidé Byron à bâtir un style très personnel, il n’avait pas toujours pu exploiter tout son potentiel en raison de ses origines afro-américaines. Il expliquait: "Nobody wanted to believe I was capable of doing the classical stuff. I'd show up and they'd say, 'You want to play jazz.' In the classical pedagogy, I had teachers telling me my lips were too big."

Byron ayant été atteint d’asthme durant son enfance, un médecin lui avait recommandé d’apprendre à jouer d’un instrument à vent afin de développer ses capacités respiratoires. C’est ainsi qu’il avait commencé à jouer de la clarinette.

Byron avait grandi dans le sud du Bronx aux côtés de jeunes juifs qui avaient contribué à développé son intérêt pour le klezmer, la tradition musicale des Juifs ashkénazes d’Europe centrale et d’Europe de l’Est. Décrivant son intérêt pour la musique juive, Byron avait commenté: ‘’I was playing Jewish music 15 years before all of this downtown [radical Jewish culture] activity. [Klezmer] is just a music that uses clarinet; it’s just one of the musics that I play that uses clarinet. I was interested in the chord changes and the scales. There’s lots of little musics around the world where the clarinet is kind of like the lead instrument.”

Parmi les autres influences de Byron à cette époque, on remarquait Joe Henderson, Artie Shaw, Jimmy Hamilton et Tony Scott. À l’adolescence, Byron avait pris des cours de clarinette avec Joe Allard. Il avait aussi écrit des arrangements pour le groupe de son high school. George Russell avait également été un de ses professeurs durant ses études au New England Conservatory of Music de Boston où il avait décroché un baccalauréat en musique en 1984. Durant cette période, Byron avait également fait partie du Klezmer Conservatory Band dirigé par Hankus Netsky. À l’époque où il avait obtenu son diplome, Byron était d’ailleurs devenu le leader du groupe. Il avait aussi joué avec des groupes de jazz latin. Byron avait également étudié à la Manhattan School of Music de l’Université de New York.

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

Byron avait quitté le Klezmer Conservatory Band en 1987 pour travailler avec de grands noms du jazz comme Reggie Workman, Hamiet Bluiett et Bill Frisell. Il avait aussi joué avec des musiciens d’avant-garde comme Craig Harris et David Murray.

En 1991, Byron avait publié un premier album comme leader intitulé Tuskegee Experiments. Le titre de l’album faisait référence à une série d’expériences médicales et psychologiques hautement discutables sur le plan éthique tentées sur des Afro-Américains en 1932. Enregistré avec Frisell et Workman, l’album comprenait des versions de "Auf Einer Burg" du compositeur classique Robert Schumann et de ‘’Mainstem’’ de Duke Ellington. Le Penguin Guide to Jazz avait qualifié l’album de chef-d’oeuvre et d’un ‘’des premiers albums les plus excitants en plus d’une décennie."

L’album suivant de Byron, Plays the Music of Mickey Katz, avait été une surprise pour les amateurs de jazz qui ne connaissaient pas les antécédents de Byron avec la musique klezmer. Tentative de témoigner de la contribution des traditions yiddish à la culture populaire américaine, l’album avait été décrit en ces termes par Byron qui avait expliqué en entrevue: "People today think that Jewish musicians of the 20's, the generation that could have been klezmers, had the greatest attitude about their own music. But really, those cats didn't want to know... klezmer. They wanted to play jazz or symphony --anything to avoid being stereotyped by klezmer." Malheureusement, plutôt que de mieux faire accepter la culture yiddish, l’album avait eu pour résultat de l’enfermer dans certains stéréotypes. Comme Byron l’avait expliqué plus tard au cours d’une entrevue accordée au magazine Down Beat: "I run into people all the time who don't know I made anything after the Mickey Katz record. No matter how much I've done before and after, it always seems to be that stuff they want to talk about and hear. Sometimes I'm sorry I did it."

ÉVOLUTION RÉCENTE

Peu avant la publication de l’album Music for Six Musicians en 1995, Byron avait expliqué la démarcation qui existait entre le jazz dit ‘’mainstream’’ et l’avant-garde. Comme il l’avait déclaré au cours d’une entrevue accordée au magazine New York Times:

"Me and most of the cats I hang with, we're too left-wing to be around {mainstream jazz institution Jazz At} Lincoln Center. They should be presenting the freshest, baddest stuff. I don't even exist in jazz the way these people perceive it to be.... I've gotten to the point where I can't care what other jazz cats think." L’album Music for Six Musicians était un hommage à la musique afro-cubaine qui avait marqué la jeunesse de Byron dans le Bronx. La musique latine formait d’ailleurs un volet important de la personnalité musicale de Byron. Continuant de témoigner d’une grande conscience sociale, Byron avait ouvert l’album sur un extrait du poème d’Haji Sadiq Al Sadiq "White History Month," qui contenait des affirmations comme: "You think it fair if there was a white history month? ... I picture a kind of underground railroad, Delivering us in the dead of night from the inner city to the suburbs, Yea, like right into the hands of the Klan?"

En 1996, Byron avait fait une apparition dans le film Kansas City de Robert Altman aux côtés d’autres grands noms du jazz comme Geri Allen et James Carter. Même si le film était un hommage à la musique du début au milieu des années 1930, la bande sonore avait laissé une grande place au jazz contemporain. Selon le directeur musical Hal Willner, "If you listen to records like 'Lafayette' {by Count Basie} or 'Prince of Wails', there was as much energy as any punk-rock I've ever heard." Dans le film, Byron avait interprété un solo sur la pièce d’Eddie Durham "Pagin' the Blues."

En 1996, Byron avait d’ailleurs publié un album intitulé Bug Music dans lequel il avait rendu hommage à la fois aux compositions classiques de Duke Ellington et aux oeuvres des compositeurs John Kirby et Raymond Scott, qui avaient souvent été discrédités par les critiques malgré leur succès commercial et la complexité technique de leur musique. Comme Byron l’avait expliqué dans l’ouvrage Music and The Arts, "Even in Gunther Schuller's The Swing Era, {he says} it's not really good music.... When you look at the era those cats came up in, that was the stuff that was turning everybody out." Byron avait ajouté que le titre de l’album était inspiré d’un épisode du dessin animé The Flintstones qui comprenait une parodie des Beatles avant que la musique du groupe ne soit considérée comme acceptable par les critiques de la musique ‘’mainstream.’’

En suivant sa propre inspiration et en ignorant les préjugés subjectifs des critiques, Byron était devenu une des voix les plus intéressantes de la musique des années 1990. Dénonçant la façon stéréotypée dont les musiciens noirs étaient traités dans le cadre d’un profil publié dans le magazine New York Times, Byron avait déclaré: "Nobody calls up Eric Clapton and says, 'Yo, Clapton, you're the white guy that plays all that black {expletive}, right? Why don't you come play at a rally?' What makes them think they can do that to me?"

En 1999, lors de la promotion de son album Romance With the Unseen, Byron avait expliqué pourquoi il avait toujours eu des goûts aussi éclectiques. Byron, qui détestait les étiquettes, avait commenté:

‘’I think lots of people listen to that range of music. Ultimately, intellectually, I’m very connected to that range of idioms. The clarinet puts you in a situation that’s kind of unique. There’s no way you can play the clarinet without playing classical music, so well all have that, even some of the cats like Greg Tardy. To play as much clarinet as he plays, you can’t without going to school and studying Mozart. People are just not used to seeing black folks to do that. It just takes that involvement in that kind of music to get to a point where you can even finger some jazz.’’

Byron croyait d’ailleurs que sa jeunesse dans le Bronx l’avait préparé à manifester une grande ouverture face aux autres cultures. Il expliquait:

‘’In terms of trying to put together a poetry project {Nu Blaxploitation}, I grew up in the South Bronx (Eddie Daniels didn’t grow up in the South Bronx) so I saw Grandmaster Flash and DJ Cool Herc; these cats were all around the neighborhood, so I witnessed the beginning of {hip-hop}. My parents are of Afro-Carribean descent so we were into the calypso, and Afro-Carribean stuff and Cumbia... and my father was a jazz musician too, so we even knew some cats who were in and out of the Basie and Ellington bands. So I’m not really doing anything that I didn’t hear before I was 18. I didn’t grow up in a sheltered way, like I didn’t hear before I was 18. I didn’t grow up in a sheletered way, like ‘We’re from the Dominican Republic and we only listen to meringue’’; that’s not the way I grew up.’’

Évoquant son implication sociale et politique, Byron avait déclaré:

‘’I just have a certain politic. I think a lots of people have a polioc, but I think in the past, certainly since the Young Lions era, there hasn’t been a lot of politics in the music. But compared to what Mingus was talking about it’s not excessive, compared to what the hip hop cats are talking about, or the Last Poets, I don’t think it’s excessive. People that know me know what if we’re gonna talk for an hour, we’ll spend 20 minutes talking about stuff that I have in my pieces. When I think about putting that politic and that feeling in the music I think back to the Gary Bartz Ntu Troop. That for me was a model of how to do it, just feeling ike when you put out a thing you want to put out some kind of gestalt picture of what you are. I think we’re at a point in history where people don’t want to think about those things because it profits them to think, or at east to let you think, that all of this stuff is over and we don’t need to be talking about biases of race and gender. And it’s never over, either you want to talk about it or you don’t, so if the fact that you want to talk about it means that you’re controversial. If you read where I was coming from doing the Mickey Katz and doing Bug Music, there’s even a politic to those particular projects.’’

Membre de la Black Rock Coalition, une organisation qui affirmait que le rock n’ roll était inspiré de la musique noire, Byron avait interprété la pièce "Bli Blip" dans la compilation de la Red Hot Organization intitulée Red Hot + Indigo en 2001. Hommage à la musique de Duke Ellington, l’album avait pour but de recueillir des fonds pour prévenir et combattre le SIDA. Dans le cadre de l’album, Byron avait joué aux côtés de Bill Frisell, Joe Henry, Marc Ribot, Vernon Reid et Allen Toussaint. Dans les années 1990, Byron avait également dirigé le quintet de musique classique Semaphore. De 1996 à 1999, Byron avait aussi été directeur musical de la Brooklyn Academy of Music où il avait dirigé une série de concerts pour le Next Wave Festival et présenté en première son spectacle pour enfants intitulé Bug Music for Juniors.

De 2000 à 2005, Byron avait été artiste-en-résidence au New York's Symphony Space où il avait dirigé l’Adventurers Orchestra, lancé la série de concerts Contrasting Brilliance et tranmis sa vision de compositeurs et d’artistes comme Henry Mancini, Sly Stone, la compagnie de hip-hop Sugar Hill Records, Igor Stravinsky, Raymond Scott, Herb Alpert et le groupe Earth, Wind and Fire.

Également professeur, Byron avait enseigné la composition, l’improvisation, l’histoire de la musique, la clarinette et le saxophone à la Metropolitan State University of Denver (2015), l'Université d'Albany (2005–2009) et le Massachusetts Institute of Technologie (MIT) de 2007 à 2008. Historien du jazz reconnu, Byron avait tenté de recréer dans ses albums des moments importants de l’histoire des de la musique populaire, notamment dans le cadre d’albums comme Plays the Music of Mickey Katz (1993) et Bug Music (1996).

Don Byron a remporté de nombreux honneurs au cours de sa carrière, dont une bourse de la Fondation Guggenheim en 2007. La même année, Byron avait été nommé USA Prudential Fellow et avait décroché une bourse de United States Artists, une organisation caritative qui soutient et encourage le travail des artistes américains. En 2009, l’American Academy de Rome lui avait également décerné un Rome Prize Fellowship. La même année, la composition de Byron intitulée Seven Etudes for solo piano, qui lui avait été commandée par la pianiste Lisa Moore, lui avait valu d’être mis en nomination pour un prix Pulitzer en composition. Byron avait aussi été mis en nomination en 2005 pour un prix Grammy pour le meilleur solo de jazz instrumental pour son solo de clarinette basse sur le standard "I Want to Be Happy" tirée de l’album Ivey-Divey en 2004. Byron avait également été juge lors du 2e gala des Independent Music Awards. Élu artiste de jazz de l’année par le magazine Down Beat en 1992, Byron avait également remporté le prix de meilleur clarinettiste dans le cadre des sondages des critiques du magazine Down Beat de 1992 à 1997.

Musicien et compositeur très éclectique, Byron a travaillé dans des contextes diversifiés allant de la musique classique à la salsa, en passant par le be bop, le swing, le hip-hop, le funk, le rhythm & blues et la musique klezmer. Il s’est également produit dans plusieurs festivals de musique à travers le monde, y compris à Vienne en Autriche, San Francisco, Hong Kong, Londres en Angleterre, Monterey en Californie, en Nouvelle-Zélande et à Broadway.

Byron a collaboré avec les plus grands noms du jazz au cours de sa carrière, de Mario Bauza au Duke Ellington Orchestra, en passant par John Hicks, Tom Cora, Bill Frisell, Vernon Reid, Marc Ribot, Cassandra Wilson, Hamiet Bluiett, Anthony Braxton, Geri Allen, Jack DeJohnette, Hal Willner, Marilyn Crispell, Reggie Workman, Craig Harris, David Murray, Leroy Jenkins, Bobby Previte, Gerry Hemingway, DD Jackson, Douglas Ewart, Brandon Ross, Ed Neumeister, Tom Pierson, Steve Coleman, Living Colour, Ralph Peterson, Uri Caine, Mandy Patinkin, Steve Lacy, les Kansas City All-Stars, les Bang On A Can All-Stars, Medeski Martin & Wood, Angelique Kidjo, Carole King, Daniel Barenboim et Salif Keita. Il a également collaboré avec l’Atlanta Symphony, Klangforum Wien (un orchestre de chambre autrichien), le guitariste auteur-compositeur Joe Henry, l’écrivain Paul Auster, la poète, bassiste et autrice-compositrice Meshell Ndegeocello et plusieurs autres.

Évoquant sa collaboration avec Jack DeJohnette, Byron avait expliqué: ‘’I like those loud, interactive drummers, all of which are coming out of Jack, even Joey Baron and Ralph Peterson - they’d all say in a heartbeat that they’re coming out of {Jack}. So it was just interesting to experience Jack firsthand.’’ Au sujet de sa collaboration de longue date avec le guitariste Bill Frisell, Byron avait ajouté: ‘’We have a sense of line that’s similar and a sense of harmony and how to attack it. I think that we’ve used all of the indefinite qualities of our instruments together in a really kind of unusual way.’’

Un des derniers projets de Byron était un duo avec le pianiste Uri Caine. Il expliquait:

‘’I’m doing this duo thing, gathering songs together that have the kind of control over harmony and the drama of lyrics that an aria from an opera has. I had to try to find some stuff that did that. There’s the obvious stuff, like the Schumann that I love, Puccini, but then I pulled in some Stevie Wonder or some L.A. and Babyface, and we’re gonna have different singers come in and guest. It’s a duo between me and Uri with a few guest singers, some Broadway, some pop, some jazz.’’

Grand amateur de musique classique, Byron appréciait particulièrement la Symphonie No 1 de John Corigliano. Il expliquait: ‘’An excellente performance, great music that actually encourages classical players to make improvisational choices without they knowing it.’’ Parmi ses autres albums de prédilection, Byron citait La Sonora Poncena, un disque de jazz afro-cubain dEdward Simon la Bikina, Musical Conquest de Mike Nichols et Elaine May et Sonny Meets Hawk, de Sonny Rollins et Coleman Hawkins.

©-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

SOURCES:

‘’Don Byron.’’ Wikipedia, 2023.

‘’Don Byron.’’ All About Jazz, 2023.

‘’Don Byron Biography.’’ Net Industries, 2023.

JENKINS, Williard. ‘’Don Byron: Range and Vision.’’ Jazz Times, 25 avril 2019.

2 notes

·

View notes