#Dimitar Bechev

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

"He's the quintessential populist" | Dimitar Bechev on his book "Turkey Under Erdoğan"

0 notes

Text

Kolektif – Türkiye’de Balkanlar (2023)

Balkanlar, Türkiye toplumunun sosyo-kültürel ve siyasi yapısı açısından çok kritik öneme sahip. Bu çok yönlü derlemede, Türkiye’deki Balkan etkisi ve varlığı enine boyuna ele alınıyor: “Muhacir” sözcüğüyle neredeyse özdeşleşmiş Balkan muhacirleri ve göç politikası… Bu uzun göç tarihinin hafızadaki izleri ve nostaljisi… Kadınların evlilik tecrübesiyle kesişen, çocukları yalnızlığa iten kendine…

View On WordPress

#2023#Ahmet Ceylan#Ayşe Parla#Özlem Hocaoğlu#Bayram Şen#Dimitar Bechev#Dionysis Goularas#Ersin Uğurkan#Feryal Tansuğ#Gökçe Bayındır Goularas#Leman İncedere#Nurcan Özgür Baklacıoğlu#Selda Adiloğlu#Sinem Arslan#Tanıl Bora#Türkiye’de Balkanlar#Ulaş Sunata#İletişim Yayınları

0 notes

Photo

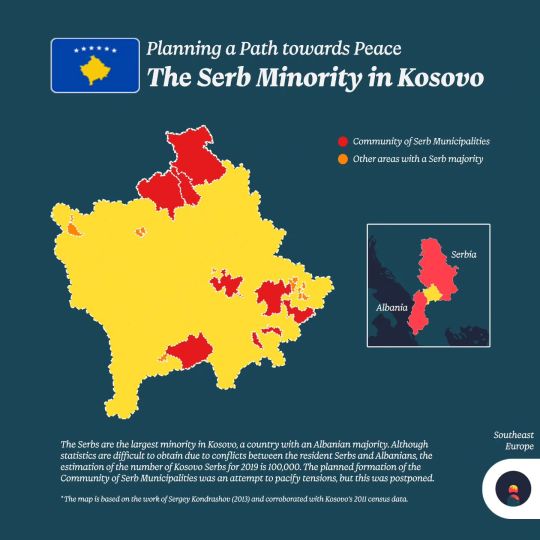

The Serb minority in Kosovo

The Serbs make up the largest minority of the population in Kosovo, a Balkan nation with an Albanian majority that proclaimed its independence from Serbia in 2008. Reliable statistics on the number of Serbs in Kosovo are difficult to obtain as a result of the complications caused by the wars and disagreements between the resident Serbs and Albanians. However, the usual estimation for 2019 is 100,000, down from around 300,000 in 1999.

In an attempt to pacify tensions in the country, the 2013 Brussels Agreement called for the formation of the Community of Serb Municipalities in Kosovo. But it was postponed due to conflicts, the most recent of which occurred in September 2023 when armed Serb paramilitaries assaulted a police patrol in northern Kosovo, killing one officer.

What do you think is the best way to bring Serbs and Albanians in Kosovo together in peace?

Sources:

Bechev, Dimitar. “Analysis: are Kosovo and Serbia on the brink of war?” Al Jazeera. 3 October 2023.

Judah, Tim. “Kosovo’s demographic destiny looks eerily familiar.” Reporting Democracy. 7 November 2019.

“Serbs.” Minority Rights Group. March 2018.

by anthro.atlas

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Je li NATO u krizi?

Je li NATO u krizi?

Dimitar Bechev Dvadesetprvog septembra, britanski premijer Boris Johnson sreo se sa američkim predsjednikom Joeom Bidenom u Bijeloj kući. Ovi pregovori su bili na nivou uspješnog diplomatskog poteza za London. Uslijedili su odmah nakon objave tzv. AUKUS-a, trodijelnog partnerstva između SAD-a, Velike Britanije i Australije. Pod uvjetima ovog partnerstva, vlada u Canberri je pristala da nabavi…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Macedonia cigarettes from 1941-44. pic.twitter.com/Oe4TNVXjJM

— Dimitar Bechev (@DimitarBechev) August 20, 2019

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A seaside-villa scandal sparks huge protests in Bulgaria

Bullies on a beach A seaside-villa scandal sparks huge protests in Bulgaria

Bodyguards who shoved an opposition politician could cost Boyko Borisov, the prime minister, his job

ON JULY 7TH a small boat motored up to a villa near the Black Sea resort town of Burgas. On board (and livestreaming) was Hristo Ivanov, a former justice minister who leads “Yes Bulgaria”, an anti-corruption party. He wanted to show that the villa’s main resident, Ahmed Dogan, founder of a party representing the country’s ethnic Turkish minority, was illegally treating the beach as his own. (In Bulgaria, coastal beaches are public property.) Mr Ivanov alighted and planted a Bulgarian flag, to the consternation of several muscular men in sunglasses who, unmoved by the ex-minister’s protestations of his constitutional rights, pushed him into the water.

A few weeks on, it is Bulgaria’s government that risks being pushed over. Mr Dogan is seen as an ally of the prime minister, Boyko Borisov, a former bodyguard who dominates the political scene with a mix of populism and patronage. But multiple scandals have led to daily protests in Sofia by thousands of demonstrators. On July 23rd Mr Borisov announced he was sacking four of his ministers, hoping to fend off demands that he resign.

The government’s troubles started in June, when an anonymous source began leaking recordings of someone who sounded like Mr Borisov ridiculing EU officials and boasting of harassing a local business. The next week, photos surfaced of a man resembling the prime minister asleep on a bed, with a handgun on the nightstand and an open drawer full of €500 bills and gold ingots. Mr Borisov said the recordings and photos were manipulated, but acknowledged it was his bedroom.

Then came Mr Ivanov’s visit to Mr Dogan’s beach, which led to questions about the mysterious men who shoved him. On July 8th Rumen Radev, Bulgaria’s president, who was nominated by the opposition Socialists, revealed that they were officers of the state agency that protects senior officeholders. It was providing security for Mr Dogan and another member of his party: Delyan Peevski, a media oligarch. It was not clear why they deserved taxpayer-supplied beach bouncers, and Mr Radev called for the protection to be withdrawn.

The response was swift. On the morning of July 9th police raided the president’s office and detained two aides on charges of influence-peddling and disclosing state secrets. That afternoon demonstrators took to the streets, accusing the chief prosecutor of ordering the raid. By July 11th Mr Radev was saying Mr Borisov ran a “mafia government” and urging him to step down.

Mr Borisov’s term ends next spring, but he may not last that long. Axing his finance, economy, interior and culture ministers was meant to deflect blame, but it hardly suggests strength. Dimitar Bechev, a political scientist at the University of North Carolina, thinks he has lost control of the agenda: voters suspect he is beholden to Mr Dogan and Mr Peevski. But early elections would bring little relief. Apart from Mr Borisov’s conservative GERB party, only the Socialists are strong enough potentially to form a government. They are seen as little better than GERB on corruption, and are friendly towards Russia.

All this has made for a rough summer. Bulgaria handled the first stage of the covid-19 epidemic well, with a tough lockdown. Early this month the European Commission accepted its entry into the “waiting room” for adopting the euro. But covid-19 cases have begun to rise, and the scandals are a reminder of how little progress has been made against corruption. “The state of democracy, the state of the institutions and the quality of life have been going backwards rather than forwards,” says Ruzha Smilova, a political scientist at Sofia University. At least the weather at Mr Dogan’s villa has been marvellous. ■

This article appeared in the Europe section of the print edition under the headline "Bullies on a beach"

https://ift.tt/3fPiG1b

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bulgaria rocked by protests amid coronavirus fears | News

Over the past four days, Bulgaria has been shaken by a wave of anti-government protests with thousands marching through the capital Sofia “against a mafia model of governance”.

Demonstrators have demanded the resignation of Prime Minister Boyko Borisov, and smaller protests have been held in other cities in the country.

Public anger erupted on Tuesday when a politician from the centre-right party, Democratic Bulgaria, Hristo Ivanov, tried to reach a public beach on the Black Sea coast but was stopped by officers from the National Protection Service (NSO), guarding the nearby mansion of Ahmed Dogan, former leader of the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS) party.

Ivanov accused Borisov’s government of enabling Dogan, who is seen as one of the most powerful men in Bulgaria, to encroach on public property and using taxpayer’s money to provide him security, although he occupies no formal government post.

On Saturday, after declaring that NSO will stop providing a security detail for Dogan, Borisov of the governing GERB party rejected the calls for his resignation.

“We will remain in power because the opposition will break the country,” he said in a Facebook live from his home.

Earlier in the day, Bulgarian President Rumen Radev, a member of the opposition Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), also called on Borisov, as well as General Prosecutor Ivan Geshev, to resign. On Thursday, prosecutors entered the presidency building and arrested two members of the presidential administration.

The raid came after Radev criticised the government and said NSO should not guard Dogan.

The deepening political crisis comes after a series of major political scandals in recent months and amid growing public anger against the government’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic.

After Bulgaria saw a slump in daily cases during a two-month lockdown, the sudden opening up of businesses and the permission to hold public gatherings have led to a new spike in cases.

Analysts say the roots of the present crisis run deep and have to do with the country’s weak rule of law and the problematic relationship between oligarchy and politics.

Oligarchy and ‘state capture’

Dogan is a controversial figure in Bulgarian politics. A former agent of the communist secret services and an ethnic Turk, he founded the DPS in 1990 as a party meant to give political representation to Bulgaria’s Turkish minority, which had been brutally victimised by the collapsing communist regime.

Over the next 20 years, however, he came to occupy an important position in Bulgarian politics. “The power is in my hands. I am the instrument of power that distributes the portions of financing in the state,” he famously saidin 2009.

Bulgarians shout slogans and hold the national flag during a demonstration in front of the Council of Ministers in Sofia [Vassil Donev/EPA-EFE]

Dogan has not been seen in public for several years and refused to give on-camera interviews during the recent events.

Bulgarian media mogul Delyan Peevski, who is one of Dogan’s closest allies and also a member of DPS, has also been using NSO security.

Ivanov of Democratic Bulgaria Party has accused Dogan and Peevski of controlling the General Prosecutor’s office and the interior ministry, and has claimed Borisov is “afraid of” and “dependent” on them.

“[Dogan and Peevski are] part of a governing cartel going back to the mid-2000s. Other stakeholders include the Prosecutor General and whoever happens to be in power,” Dimitar Bechev, senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, told Al Jazeera.

According to him, “state capture is a reality” in Bulgaria.

“[In Bulgaria, there is] weakness of the rule of law and the fact that the most powerful political force, GERB, isn’t a transformational actor but part of the setup [and the] EU is no longer an external check … but a source of rent,” he said.

The European Union, which Bulgaria became a member of in 2007, has repeatedly suspended financial assistance for various economic initiatives in the small Balkan country over corruption concerns and its failure to tackle organised crime. DPS has been accused of controlling public works funding in non-urban areas, part of which has come from the EU.

According to Jana Tsoneva, a Sofia-based sociologist, the main problem in Bulgarian politics is that DPS, along with all other major parties, are dependent on powerful business interests.

“[Big] business is a source of corruption … When we talk about corrupted politicians, we have to talk about who is corrupting them,” she said. “We need institutions to be fixed, but that cannot happen as long as [big] businessmen continue to buy politicians and use these institutions in their internal battles of market share.”

What happens next?

The political crisis in Bulgaria has exacerbated the growing public discontent triggered by the coronavirus pandemic and the slumping economy. According to the European Commission, Bulgaria’s economy is projected to shrink by 7.1 percent. Meanwhile, unemployment has soared to 9 percent.

Some have argued the crisis may bring Borisov’s long political career to an end and damage GERB’s chances in the next election.

In an opinion poll released by Sova 5 in early July, before the protests erupted, just 28.5 percent of the respondents said they trust Prime Minister Borisov; 31.9 percent said they trust President Radev.

If there were to be early elections, Borisov’s GERB party, which has led three governments in Bulgaria since 2009, would get 21.3 percent of the vote, Radev’s BSP 12 percent, DPS five percent, and Democratic Bulgaria 2.4 percent, the poll suggested.

Bechev and Tsoneva said the protests are unlikely to shrink GERB’s support significantly, but they could lead to early elections.

“Early polls might help Borisov maximize the vote for GERB but will hand power to Radev who appoints a caretaker government,” said Bechev. “I guess GERB will still be the largest party after the next elections, but the question is who will coalesce with it.”

Borisov’s current coalition partner, the far-right alliance United Patriots, may not clear the 4 percent threshold at the next election. Other options may include, “There is such a people”, a new party established by popular talk show host Slavi Trifonov, whose support currently stands at 5 percent, or DPS. A coalition with the latter, according to Bechev, may be too risky for Borisov, given the negative public opinion of Dogan and Peevski.

For Tsoneva, as long as GERB is in power it is unlikely for the reforms needed to end oligarchical interference in government affairs to be carried out.

However, she sees an opportunity for the pro-EU and pro-reform Democratic Bulgaria to exploit the current political crisis and play a more significant role in the political scene. Ivanov’s party is seen as catering to the small educated urban elite and so far has struggled to achieve significant results in parliamentary elections.

“[Democratic Bulgaria] could go beyond its unpopular legalistic discourse of guarantees for private ownership and anti-corruption and expand into wider notions of justice, which engage those suffering from poverty, exploitation, marginalisation and racism, and the lack of adequate healthcare, which are the concerns of the majority,” said Tsoneva.

Follow Mariya Petkova on Twitter: @mkpetkova

Source link

قالب وردپرس

from World Wide News https://ift.tt/3fo9Ozh

0 notes

Link

Bulgarians averaged just 4.8 on a zero-to-10 scale of happiness, some distance behind Portugal, the next most miserable with 6.2.

[ ... ]

Bulgaria has the lowest GDP in the EU and its unemployment rate is 10.8 percent, above the bloc’s 9.8 percent average. The average annual wage in Bulgaria was 1,949 euros in 2013 – the lowest in the EU. The country saw rapid growth between 2004-2008, but was hard hit by the economic crisis.

But Dimitar Bechev, an expert on south-east Europe from the London School of Economics, suggested Bulgaria’s misery was more nuanced than simply money.

“Joining the EU has not made Bulgarians happy,” he said. “It’s seen as a necessary evil and perhaps expectations were higher, they thought it was the silver bullet.

“Bulgarians saw their own government as problematic and Europe as the solution. But since the economic crisis that’s changed, they can’t trust anyone. There’s an underlying nature in Bulgarian people and society – not to trust anyone.

“You see some green shoots [of positivity]. There’s been lots of civic activism over the last few years, a protest movement.

“People have been calling for rule of law and more transparency in government. And for not just box-ticking for Brussels, but actually doing it for yourself.

“But that’s long-term, it doesn’t happen overnight. But if it does happen – more democracy, more transparency, more accountability – then over time the amount of people saying things are going in the right direction will increase. But we’re not there yet, as this survey shows.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Commentaries, Analysis, And Editorials -- February 19, 2019 https://ift.tt/2IobAV9

ISIL fighters are now stuck in limbo, unwanted by their home countries and unlikely to receive a trial by the SDF [File: Rodi Said/Reuters]

Zaheena Rasheed & Farah Najjar, Al Jazeera: Burden of victory: What should happen to European ISIL prisoners? Fate of more than 1,000 European ISIL prisoners, detained by Kurdish forces in northern Syria, hangs in the balance. In a tiny sliver of land along the Euphrates River in northern Syria, about 300 battle-hardened ISIL fighters are making a last stand, with just a "few days" remaining for the group's total military defeat, according to US-backed Kurdish forces battling the fighters. But US President Donald Trump - even while hailing an impending "100 percent victory" - has issued a threat that, if executed, could help the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS) group rise once again. Read more ....

Commentaries, Analysis, And Editorials -- February 19, 2019

ISIS fighters had thousands of children. So what happens to them now? -- Saphora Smith, NBC Sunni Jihad Is Going Local -- Hassan Hassan, The Atlantic What’s next in Syria? Here are 10 takeaways. -- Tara Copp, Military Times Iran’s regional ambitions set to suffer -- Dnyanesh Kamat, Asia Times Violence breeds more violence in Kashmir -- Ather Zia, Al Jazeera Pakistan unlikely to act against terror group -- Kunwar Khuldune Shahid, Asia Times This Is How the Kashmir Terrorist Attack Could Start a Major War -- Mohammed Ayoob, National Interest Singapore defense minister: Cost of conflict in South China Sea 'too high' -- Shamil Shams, DW Now Is Not the Time for a Referendum on Taiwanese Independence -- J.Michael Cole, National Interest Vietnam opens up about past clashes with China -- Doan Xuan Loc, Asia Times Resurgent Russia: Myth and reality -- Dimitar Bechev, Al Jazeera 'There is no free press': Freedom of speech in Mexico -- Courtney Tenz, DW Trump might have a solid case for emergency declaration, analysts say -- Tom McCarthy, The Guardian China watchers in US debate ‘strategic competitor’ label Donald Trump has pinned on Beijing -- Robert Delaney, SCMP How Chinese Theft Becomes a Global Menace -- Gordon G. Chang, American Conservative Never mind Huawei: US is already winning the 5G race, Cisco report claims -- SCMP/Washington Post from War News Updates http://bit.ly/2TYLitM via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

2023 will mark the centennial of the founding of the Turkish Republic and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. In just the past two decades, one party led from its inception by one leader (excluding the period between August 2014 and May 2017), the Justice and Development Party (AKP) under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has made Turkey reverse course from the eight-decade order sustained by secular Kemalists who founded Turkey.

Dimitar Bechev, a Lecturer at the Oxford School of Global and Area Studies who is of Bulgarian descent with a specialty in the Balkans, Turkey, and Russia, has produced a masterful and balanced long view of how Turkey “succumbed to authoritarianism, took to nationalism and turned away from the West” in his recent book, Turkey Under Erdoğan: How a Country Turned from Democracy & the West.

In 2004, then-Prime Minister Erdoğan pledged to an audience of Western academics, students and journalists gathered at St. John’s College, Oxford, “to make European Values Ankara’s Values.” This was the era of Old Turkey, when, in 2002, the ruling AKP had just won their first of four consecutive elections in the past two decades, marketed themselves as “Muslim Democrats” for leading democratic reforms at home, retained an isolationist foreign policy, and participated in accession talks to join the European Union (EU) starting in 1999.[1]

Fast forward to October 2016: after having won three consecutive elections, expanded the judiciary, deployed military interventions in three continents, and consolidated draconian control over the media, law enforcement, and national institutions, Erdoğan invited Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, and Russian President Vladimir Putin to his recently finished Beștepe Mansion complex—the lavish, new, Ottoman and Seljuk-style residence of the President of Turkey.[2] The Beștepe Mansion represents New Turkey and is built on Atatürk Forest Farms, land held sacred to secular Kemalists who led the prior “eight-decade order” and now find themselves uprooted by the AKP and living in a Turkey that is richer and more influential, but whose citizens enjoy less freedoms and whose foreign policy is increasingly confrontational.[3]

Bechev provides a chronological assessment of Erdoğan’s rise to power—from the AKP’s early economic successes in the 2000s to its later muscular foreign policy that allowed Turkey to re-emerge as a considerable power broker in the region. As a power vacuum in the Middle East opened up with the United States’ gradual retreat from policing the region, Erdoğan’s AKP decided that Turkey would fill in the void, having accumulated a robust economic base from its perfection of the market economy and multi-party politics, earning Western support in the process. While Western criticism of how Erdoğan “duped the United States and EU” during this period is commonplace in explaining Turkey’s later democratic backsliding, Bechev explains how the West crying foul play on Turkey evades accountability.[4] He further elaborates that “Western allies are seen as complicit in the molding of Turkey in Erdoğan’s image,” for having encouraged Turkey to join the EU before eventually ceasing the talks.[5]

Bechev narrates the rise of the AKP as long-coming and Erdoğan as the exceptional leader who installed a one-man regime using the AKP’s profound electoral success. The AKP’s predecessor, the Motherland Party (ANAP), and Erdoğan’s predecessor, former Turkish President Turgut Özal, assured Turkey served a strategic role for the West as a “poster boy for the benefits of the market economy.”[6] ANAP, the first departure from the Kemalist-dominated establishment, provided the formula for the successful combination of domestic prosperity and more holistic neighborhood policy prioritizing engagement with the Middle East, the Balkans and post-Soviet Central Asia. A technocrat who had previously worked at the World Bank and Turkish State Planning Board, Özal spearheaded Turkey’s transition to a neoliberal development state through structural reforms such as privatizing state-owned enterprises, abolishing quotas, cutting import tariffs and opening financial flows from Western countries, which expanded the Turkish GDP by 7% in 1986 and then 9.5 % in 1987.[7]

During this period, what stood out domestically was ANAP’s practice of “big tent politics” that “captured the center ground” in the country’s electorate, attracting a wide array of the Turkish polity including conservatives, nationalists, and liberals. In its foreign policy, Turkey under Özal approached both the East and Europe for trade and cooperation, much like Erdoğan’s Turkey.[8] Özal’s reign coinciding with the collapse of the Soviet Union brought ANAP and the West a window of opportunity to sell Turkey as a model to the rest of the Islamic world. Post-Soviet Central Asian states saw Turkey as agabey (“big brother” in Turkish) and as a “model of political and economic development of other Muslim majority countries” since the 1920s.[9] While Özal himself assured that, “we have a free market, pluralistic democracy, a secular state and provide a good example for the rest of the Islamic World,” Gorbachev lauded Turkey’s “balancing effect” and Kissinger stressed Turkey’s role as a “bridge.”[10]

Bechev explains Turkey as a “double gravity state”, using this formulation to describe its predicament of being anchored in the Middle East whilst waiting at the gates of the EU.[11] In Bechev’s analysis of the AKP’s first election victory in 2002, the AKP “perfected the formula” in retaining a voting bloc of Islamist Conservatives while being welcomed by the United States and the EU. Western think-tanks praised the AKP as “Islamic Calvinists” for their integration of Islam and industriousness, while the Western intelligentsia living in Turkey saw the AKP as a “vehicle to Turkey’s liberalization, integration with Europe, and ability to come to terms with the past.”[12] In only the first decade of AKP rule, Turkey witnessed unprecedented economic growth as GDP per capita tripled from $3,600 in 2002 to $12,600 in 2013, and the GDP growth rate increased from 8% to 11% from 2010 to 2011 while the United States dealt with the aftershock of the financial crisis.[13]

Born out of Özal’s economic and diplomatic embrace of Turkey’s immediate neighborhood, the AKP’s foreign policy under Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu envisioned Turkey “as the center of the universe,” rather than a Western periphery.[14] A former professor of international relations elevated to the Foreign Ministry by Erdoğan, Davutoğlu stressed that Turkey “did not have to choose” between EU membership and engagement with the East.[15] As outlined in his visionary book, Strategic Depth, Turkey enjoys multiple identities and the unique combination of their history and geography brings a sense of responsibility to contribute actively toward peace and security. The “Zero Problems with Neighbors” policy created by Davutoğlu showed how the “flag followed trade”, as between 1999 and 2008, trade with the Middle East grew tenfold, trade with Iran grew thirteen fold, trade with Russia grew twelve fold, and Turkish exports to the Balkans and the Middle East outpaced imports.[16]

However, Turkey’s foreign policy after the Arab Spring failed to achieve the country’s hegemonic goals that had seen some progress in the Balkans, as regime change efforts in the Middle East and North Africa brought limited success. After nearly a decade of exponential trade and mobility gains in the early 2000s, Egypt, Syria, and Libya became realms for power competition. Davutoğlu decided at this moment that Turkey would be on the right side of history as the revolution’s standard bearer by supporting the masses against their authoritarian leaders. In refusing to maintain ties with the oppressive rulers and supporting popular uprisings to secure basic democratic rights, Erdoğan declared that the “Turkish state is in its core a state of freedoms and secularism.”[17]

Despite these professed values, in the decade following the Arab Spring Turkish democracy itself proved to be eroding from internal factors under Erdoğan’s watch. The expansion of the judiciary in 2010, the Gezi Park protests in 2013, the 2016 failed coup attempt, and finally, the abolishment of the Office of Prime Minister in 2017 all marked important steps in the decline of democracy in Turkey. In the meanwhile, the Turkish state also cracked down on the media based on allegations of ties to the plotters of the 2016 coup. This dropped Turkey’s media freedom ranking from 101 in 2007 to 157 in 2019. Even worse, as a result of Erdoğan’s abolishment of the Prime Minister, Freedom House to designate Turkey as “not free.”[18] The effects of rolling back institutions will undermine Turkey’s practice of multi-party politics, which to Bechev is the one thing that keeps Turkish democracy from devolving into autocracy like its neighbors Azerbaijan and Russia.

Turkey Under Erdoğan does an admirable job overall describing Erdoğan’s political rise and consolidation of power, but it neglects one important aspect—the development of its defense industry into one of the most powerful players in the region. While Bechev explains how internal factors such as Turkish nationalism and a strong market economy fueled military interventions in three continents over the course of two decades, he does not describe how the Turkish state became a regime with an indispensable capacity for hard power. From proxy forces to drone capacity, how exactly the Turkish defense industry prepared itself for its military forays abroad deserves attention. This question is even more important considering Erdogan’s declaration in October 2020 that Turkey has reduced their external dependency in the defense industry from around 70% to around 30%.[19]

Ultimately, Turkey Under Erdoğan illustrates the shift in domestic and foreign policy to the “new Sultan’s imperial designs” as well as external challenges.[20] “Neo-Ottomanism” is a label of increasingly common use in the Western media for Turkey’s foreign policy whether in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea or Syria.[21] While Erdoğan’s claim to global leadership of Muslims is acknowledged by Bechev, irredentism, pan-Turkism and Ottoman nostalgia are all actively present in AKP rhetoric as well as in Western and Kemalist media outlets. The AKP’s decision to increase Turkey’s regional stature rests on a larger narrative to rise in the region built upon Turkish nationalism and demolition of checks and balances, with much socioeconomic and political risk.

Turkey's role in the global response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine earlier this year has underlined its status as a regional superpower: with the eyes of the world now on Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Bechev's book provides an essential crash course to the politics of one of the region's most complex, ambitious and influential actors.

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

🇲🇰 🇬🇷 What is in a name? | Inside Story by Al Jazeera English A new name was intended to end decades of diplomatic deadlock. But nationalists in both Greece and Macedonia are unhappy at the choice - Republic of North Macedonia. Thousands of people in both countries took to the streets to protest against a deal they say is tantamount to a humiliating defeat. A far-right Greek newspaper went so far as to run a front-page graphic - showing Greece's prime minister, foreign minister and president being shot by firing squad for treason. Between the end of World War Two and the early 1990s, Macedonia was one of six republics comprising the former Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. It declared independence in 1991 under the name -- the Republic of Macedonia. Greece immediately opposed it, seeing it as a veiled challenge to Greek sovereignty over its northern province that's also called Macedonia Presenter: Elizabeth Puranam Guests: Borjan Jovanovski, Chief Editor of NOVA TV. Panos Polyzoidis, Political Analyst and Journalist Dimitar Bechev, Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council Subscribe to our channel http://bit.ly/AJSubscribe Follow us on Twitter https://twitter.com/AJEnglish Find us on Facebook https://ift.tt/1iHo6G4 Check our website: https://ift.tt/snsTgS

0 notes

Text

Šta dogovor o Nagorno-Karabahu znači za Rusiju i Tursku?

Ankara je uspjela doći do uporišta na jugu Kavkaza, no Moskva u toj regiji i dalje ima glavnu riječ.

Dimitar Bechev

Ruske trupe su 11. novembra preuzele koridor Lahin koji povezuje Armeniju i odmetnutu enklavu Nagorno-Karabah. Njihovo razmještanje je bio prvi korak u provođenju mirovnog sporazuma koji su postigli Azerbejdžan, Armenija i Rusija dva dana ranije.

Prema sporazumu, Moskva je pristala poslati kontigent od 2.000 mirovnjaka i uspostaviti 16 posmatračkih tački oko Nagorno-Karabaha. Dogovoreno je i da Azerbejdžan ponovo preuzme sedam distrikta oko regije, uključujući i Šušu (Šuši na armenskom), njegovu historijsku prijestolnicu nakon šest sedmica borbi protiv Armenije i samoproglašene republike Artsakh.

Premda je sporazum krunsko postignuće za predsjednika Ilhama Alijeva, Rusija je također došla do značajnih dobitaka. Nagorno-Karabah je bio jedini „zamrznuti sukob“ u postsovjetskom prostoru gdje nije bilo ruskih „čizama na terenu���. To je dalo lokalnim stranama, Erevanu i Bakuu, više prostora za manevre. Azerbejdžan je također jedina država na jugu Kavkaza bez ruske vojske na svom terenu. Sada se to promijenilo.

Pašinijanova budućnost

Novi status-quo danas u Nagorno-Karabahu je podsjeća na odmetnutu regiju Transnjistrija u Moldaviji ili Južnu Osetiju i Abhaziju koje su se odvojile od Gruzije, a gdje se Moskva nametnula kao arbitar od samog početka dešavanja.

Na ruku Putina je rat donio i odlazak armenskog premijera Nikola Pašinijana. On je došao na vlast kroz ulične demonstracije aprila i maja 2018. godine, a bivši novinar je upravo ona kategorija „obojenog revolucionara“ kakve Kremlj vidi kao prijetnju.

Iako Pašinijan, razumljivo, nikada nije dovodio u pitanje armensko-ruske specijalne odnose, on se sukobljavao sa pojedincima i klanovima povezanim sa Moskvom. Ranije ove godine, Seržu Sargsjanu, bivšem predsjedniku koga je Pašinijan svrgnuo, počelo je suđenje za korupciju zajedno sa nekoliko njegovih ministara. Još jedan bivši lider Rober Kočarjan, koji je slučajno lični Putinov prijatelj, našao se na sudu zbog nasilnog suzbijanja demonstracija 2008. godine.

Zbog toga su Pašinijanove poruke ka Moskvi, i prije i tokom rata, bile uglavnom odbijane. U julu je Margarita Simonjan, šefica ruskog medija RT i jedna od vodećih propagandista Kremlja, optužila armenske lidere za antirusku aktivnosti i kazala kako oni ne trebaju očekivati rusku pomoć ako dođe do rata.

Sada Pašinijanu, koji je suočen sa ljutnjom naroda zbog teritorijalnih gubitaka, politička budućnost visi o niti. Ruskim liderima neće nedostajati ako ode. Mediji bliski Kremlju sada slave rusku ulogu u očuvanju armenskih historijskih lokacija i zaštiti naroda na terenu, te ističu ogromnu suprotnost sa navodnim neuspjesima Pašinijana.

Šta je Turska dobila?

No, veliko pitanje koje svi postavljaju se odnosi na Tursku. Kakav je njen rezultat u Nagorno-Karabahu? U konačnici, upravo je podrška njenog predsjednika Recepa Tayyipa Erdogana da pruži jaku vojnu podršku Azerbejdžancima donijela prevagu.

Dok Ankara negira izvještaje o proslijeđivanju sirijski boraca na linije fronta Nagorno-Karabaha ili raspoređivanje turskih oficira u azerbejdžanske redove, dronovi turske proizvodnje Bayraktar donijeli su haos za Armence, uništivši njihovo oružje, u prvom redu tenkove ruske proizvodnje, te izazvavši ogroman broj žrtava.

Ograničena vojna intervencija je donijela i neke političke koristi. Turska je potvrdila svoju ulogu vodećeg igrača u Južnom Kavkazu. Nadmašila je Zapad pa su SAD i Francuska, članovi takozvane Grupe Minsk za Karabah u ime OSCE-a, izgledali nebitni.

Dodatno, koridorom kroz armensku teritoriju do azerbejdžanske eksklave Nakičevan dogovorenim u Moskvi se uspostavlja direktni teritorijalni most između Turske i Azerbejdžana na pravi način. Političke i ekonomske veze dvije države bi trebale bujati što sa dobrodošlicom pozdravlja većina turske javnosti.

Kakogod, dobici su parcijalni. Turska je pokušavala upecati utjecaj na jugu Kavkaza. Ona je željela mjesto za pregovaračkim stolom za dogovor o Nagorno-Karabahu, sa Moskvom, Bakuom i Erevanom, te moguću mirovnu misiju sličnu zajedničkoj sa Rusijom u sirijskoj regiji Idlib. No, to se nije desilo.

Turska bi mogla izboriti neku simboličnu ulogu u očuvanju mira, kao što je slanje posmatrača uz ruske snage, ali to će biti odluka Moskve. Azerbejdžansko prihvatanje ruske armije je nazadak za Ankaru. U biti, Ankara se odvažila doći na ruski teren i osvojila je bodove. Turska se ubacila na „blisko inostranstvo“, kako Rusija gleda ovaj teren, jednako kao što je Rusija uradila 2015. intervencijom u Siriji. Međutim, barem za sada, Moskva je u prednosti.

Slučaj Nagorno-Karabaha dodatno ističe rusko-turska dešavanja. Dvije države su partneri i takmaci na raznim pozorištima: u Siriji, Libiji, na jugu Kavkaza, na Crnom moru kao i na Zapadnom Balkanu. Naučile su svoje lekcije i znaju kako da riješe razlike i koncentriraju se na zajedničke interese. Udruživanje protiv Zapada pomaže da se zatvore međusobni sukobi. No, to je složen čin balansiranja za Putina i Erdogana.

Stavovi izraženi u ovom tekstu autorovi su i ne odražavaju nužno uredničku politiku Al Jazeere.

Izvor

0 notes

Text

LUFTA E SPIUNAZHIT RUS NË BALLKAN

LUFTA E SPIUNAZHIT RUS NË BALLKAN

Nga Dimitar Bechev – Kur në marsin e vitit 2018, bëri bujë lajmi se ish-agjenti i dyfishtë rus Sergei Skripal dhe vajza e tij Julia, mund të ishin helmuar me një agjent nervor të quajtur Noviçok, nga agjentët që punonin për shërbimin sekret ushtarak rus, GRU, tregtari bullgar i armëve Emilian Gebrev u alarmua.

Tre vjet më parë, në prillin e vitit 2015, ai ra për disa ditë në gjendje kome, pasi…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

Vox Sentences is your daily digest for what’s happening in the world. Sign up for the Vox Sentences newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox Monday through Friday, or view the Vox Sentences archive for past editions.

The man who fatally shot Laquan McDonald in 2014 takes the stand; Macedonia’s name-change referendum fails due to low voter turnout.

Antonio Perez-Pool/Getty Images

Jason Van Dyke took the witness stand Tuesday in his own defense for fatally shooting black teenager Laquan McDonald in 2014. The Chicago police officer, teary-eyed, said McDonald was advancing on him the night he killed him. [NPR / Michael Lansu]

Van Dyke has been charged with six counts of first-degree murder, 16 counts of aggravated battery, and one count of official misconduct. [AP]

The shooting spurred days of protests in November 2015 after a judge ordered the release of a grainy dash-cam video that which showed McDonald being shot 16 times in less than 15 seconds. The prosecution has argued that race played a factor in the killing. [Fox News / Barnini Chakraborty]

In June of last year, a grand jury also indicted three Chicago police officers who are suspected of conspiring to cover up Van Dyke’s actions. [AP]

Van Dyke testified Tuesday that McDonald swung a knife at him from a 15-foot distance, and that he had never fired a weapon while on duty prior to that night. He added that he never lost eye contact with the 17-year-old and that he was “in shock” after the shooting. [Chicago Tribune / Megan Crepeau, Jason Meisner, and Stacy St. Clair]

The trial has already ignited tensions throughout the US, with a group of black pastors calling for a day-long strike if the jury lets Van Dyke walk. [Chicago Sun-Times / Adam Thorp]

The news, but shorter, delivered straight to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and European users agree to the data transfer policy. For more newsletters, check out our newsletters page.

The decades-long name dispute between Macedonia and Greece may have to wait a little longer for a proper resolution, since an overwhelming majority of the former nation’s population opted out of voting on the referendum Sunday. [Atlantic / Yasmeen Serhan]

The vote came only a few months after negotiators from both sides met at a region near Lake Prespa, where Greeks agreed to Macedonia being renamed the “Republic of North Macedonia” and joining NATO and the European Union as a member nation. [LA Times / Maria Petrakis]

Less than 37 percent of eligible Macedonian voters turned up for the referendum, failing to meet the 50 percent threshold for participation. Instead, many citizens took to social media to protest the vote with a hashtag meaning “I boycott.” [Al Jazeera / Dimitar Bechev]

The boycott is sure to upset Macedonia’s supporters since many European leaders — including German Chancellor Angela Merkel and NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg — visited the small Balkan country in September and urged voters to be a part of this “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” [Washington Post / Ishaan Tharoor]

Despite the turn of events, Macedonian Prime Minister Zoran Zaev declared the referendum vote a success, given that 91.5 percent of the votes backed the name-change arrangement and only 5.7 opposed it. [Atlantic / Yasmeen Serhan]

Amazon announced it will raise the minimum wage it pays its employees to $15 an hour, a move that will affect more than 350,000 workers. [WSJ / Laura Stevens]

Taylor Swift announced on Instagram that she’ll open the 2018 American Music Awards next week with a performance of “I Did Something Bad,” a track from her latest album. This is Swift’s first awards show set in nearly three years. [Us Weekly / Leanne Aciz Stanton]

Scientists have discovered a dwarf planet at the very edge of our solar system, nicknamed “the Goblin,” whose orbit may hint at the existence of the so-called “Planet X,” which could be 10 times the size of Earth. [Washington Post / Ben Guarino]

For her first solo trip overseas, first lady Melania Trump visited Ghana in order to learn ways the US may help the nation become more self-sufficient. She is also expected to make stops in Malawi, Kenya, and Egypt. [NPR / Tamara Keith]

“He is a fan of the technology.” [A spokesperson for Steven Mnuchin on the Treasury secretary’s transition lenses, which stole the show at a White House press conference Tuesday / The Cut]

This photo conceals a clue to a brutal story of vengeance. [YouTube / Coleman Lowndes]

USMCA, the new trade deal between the US, Canada, and Mexico, explained

Donna Strickland had no Wikipedia page before her Nobel. Her male collaborator did.

New research brings us one step closer to eradicating malaria — but progress will take a while

Artisanal brooms exist, and they can cost $350

Those whimsical “Fabric of Our Lives” ads hide the ugly truth about cotton

Original Source -> Vox Sentences: 16 shots in 14 seconds

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

NO HOPE IN TURKEY

NO HOPE IN TURKEY

By Dimitar Bechev

Those who followed Turkey’s tense constitutional referendum are looking high and low to find the silver lining. Unfortunately, there is none. Yes, President Erdoğan would have loved to carry the day with a much wider margin than 51.35 percent. The victory of the “No” vote in 17 out of 30 big urban centres, including Ankara and Istanbul where his own political career took off…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Rusya uzmanları Putin’in paralı askerleri olan Wagner Grubu’nu anlattı

Rusya uzmanları Putin’in paralı askerleri olan Wagner Grubu’nu anlattı

İlk olarak 2015’te Ukrayna’da ortaya çıkan Wagner Grubu’nu, Rusya uzmanı Dr. Has ve Bechev anlattı. Bu savaşçı gruplar kamuflaj kıyafetlerini giyiyor ama asla Rus bayrağı ya da ordudan olduklarını gösteren bir sembol taşımıyorlardı. Uzmanlara göre grup 3 bin kişiden oluşuyor. Ele geçirdikleri petrol sahalarının gelirinin 4’te 1’ini alıyorlar Pek konuşulmadı, tartışılmadı ama 7 Şubat’ta Suriye’de,…

View On WordPress

#Dimitar Bechev#haberler#Putin’in paralı askerleri#Rusya#son dakika#son dakika Dünya Haberleri#suriye#ukrayna#Vladimir Putin#Wagner Grubu

0 notes