#Defining Culinary Authority: The Transformation of Cooking in France 1650-1830

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Citizen Cooks in the Age of Napoleon

Excerpt about the role of cooks in France after the abolition of culinary guilds, and how they navigated a world which demanded for them to find new ways to stay relevant and prosperous. From Defining Culinary Authority: The Transformation of Cooking in France, 1650-1830 by Jennifer J. Davis:

French cooks sought new sites upon which to rebuild the authority of culinary labor. Throughout the early nineteenth century cooks increasingly adopted scientific terms to demonstrate their reliability and profound knowledge of the culinary arts. Such language communicated the author's education and distinction, just as an appeal to an elite patron had done in the 1660s and referral to a cook's professional expertise had done in the 1760s. The rhetoric and institutions of scientific knowledge also provided a means of distinguishing men's work from women's in the post-revolutionary era. During the early nineteenth century, cooks' claims to scientifically valuable savoir-faire rested on three crucial points of culinary innovation: food preservation, the improved production of bouillon, and gelatin extraction.

As these processes left the realm of traditional knowledge and became sites of scientific inquiry by tradespeople and amateurs alike, cooks sought to maintain authority in this arena by including scientific terms and theories in cookbooks, advertisements, and government petitions.

Two factors encouraged cooks' claims to scientific knowledge during this era. First, when Napoleon Bonaparte took the reins of government as first consul in 1799 and established himself as emperor in 1804, he raised medical doctors and academic scientists, Idéologues, to positions of political prominence. From these posts, the Idéologues subsidized experiments and inventions deemed useful to the nation and encouraged the popularization of science in the public sphere through state sponsorship of exhibitions and print forums. The Idéologues particularly supported research related to food preparation and preservation that might benefit France's armies and navies, with obvious benefits for professional cooks. Many cooks presented their particular techniques to the government during this time, seeking both financial recompense and public acclaim. Second, a voluntary association closely allied with the Idéologues' vision, the Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale (Society for the Encouragement of National Industry), provided a forum in which formally trained scientists, politicians, merchants, artisans, and curious educated men might unite to address questions that inhibited French science and industry.

Together, these men sought to develop a more coherent program for industrial advancement than any one group could achieve independently. The society explicitly sought to join scientific knowledge to artisanal practical expertise, recognizing that each group had strengths that would benefit industrial development. This association invested heavily in three diffuse projects that eventually infused the most basic culinary processes with scientific awareness: new methods of food preservation to benefit the nation's armies and navies, new methods of stock preparation to sustain the nation's poor, and new methods of extracting gelatin from bones to improve hospital and military diets at little added expense.

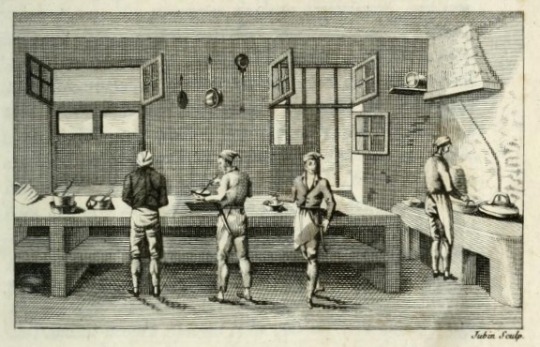

#Illustration from L'art du Cuisinier by Antoine Beauvilliers (1814)#Defining Culinary Authority: The Transformation of Cooking in France 1650-1830#Jennifer J. Davis#David#citizen cooks#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic#napoleonic era#first french empire#french empire#19th century#french revolution#cooks#food#culinary history#france#1800s#history#french history#Antoine Beauvilliers#Beauvilliers#Society for the Encouragement of National Industry#Soci��té d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon and Nicolas Appert: The invention of canned food

“Although he [Napoleon] continued so far as possible the Revolutionary practice of having armies live off the land, he also did his best to develop an efficient commissariat. A famous part of his supply system was canned food, particularly meat, for the army. Nicholas Appert had started the food-canning industry in 1804, building a factory that employed fifty people. His method prescribed putting the food in glass jars, which were next carefully stoppered, and then cooked in boiling water for lengths of time varying with the type of food. The navy first used the canned food, with great success even on extended cruises. In 1810 the Minister of the Interior awarded Appert 12,000 francs on condition he make his process public.”

— Robert B. Holtman, The Napoleonic Revolution

The inventor of canning, Appert, deposited samples of his invention to the imperial government in 1809, specifically to the Society for the Encouragement of National Industry [Société d'Encouragement pour l'Industrie Nationale].

He published his findings in 1810, titled: Le livre de tous les ménages ou l'art de conserver pendant plusieurs années toutes les substances animales et végétales [English tr: The Art of Preserving All Kinds of Animal and Vegetable Substances For Several Years]. It was “a work published by the order of the French Minister of the Interior, on the report of the Board of Arts and Manufactures”.

For his discovery, the government paid him 12,000 francs and gave him free lodgings and a workshop in the Hospice des Quinze-Vingts. Every prefecture in the French Empire was supplied with a copy of his book, and the prefects were assigned the responsibility of disseminating the information widely. Two more editions were created under the empire, and another in 1831.

His factories were ransacked and destroyed during the invasions of France in 1814 and again in 1815. He was able to rebuild and won several gold medals from the Society for the Encouragement of National Industry and eventually became a member of the Society.

Appert is quoted as saying “I sacrificed everything for humanity, all my life”.

Additional Sources:

English translation of Appert’s 1810 publication

Nicolas Appert inventeur et humaniste, Jean-Paul Barbier, 1994 (Fondation Napoléon)

Collection A. Carême: Le conservateur 1842 (archive.org)

Defining Culinary Authority: The Transformation of Cooking in France, 1650-1830 by Jennifer J. Davis

#he’s my hero 😭#Nicolas Appert#Appert#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#canned food#Robert B. Holtman#Holtman#the Napoleonic revolution#napoleonic era#napoleonic#canned#canning#first french empire#french empire#19th century#history#Jean-Paul Barbier#Barbier#culinary history#french history#napoleonic wars#coalition wars#1800s#food#food history#gastronomy#Napoleonic reforms#reforms#Napoleon’s reforms

27 notes

·

View notes