#De Rotterdam [Rem Koolhaas/OMA]

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Illustratie OMA.

De Kunsthal ligt voor mij helaas te ver weg om er nog te komen. Als ik vroeger in Rotterdam was, reed ik wel eens om voor een blik op het gebouw van Rem Koolhaas. Het interieur zag ik bijvoorbeeld tijdens een tentoonstelling over Noord-Koreaanse sociaal-realistische kunst. Voor mijn zoon en zijn vriendjes werd er ook van alles georganiseerd. Toen ik in de buurt een terrasje pikte, kwam Jules Deelder voorbij, met een hondje. De nachtburgemeester van Rotterdam droeg een wit pak.

0 notes

Text

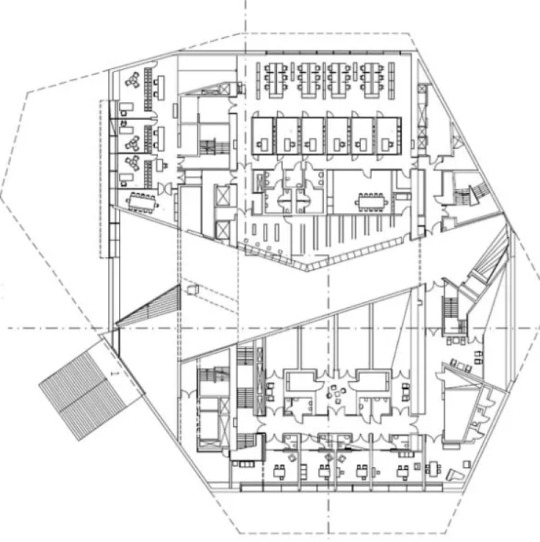

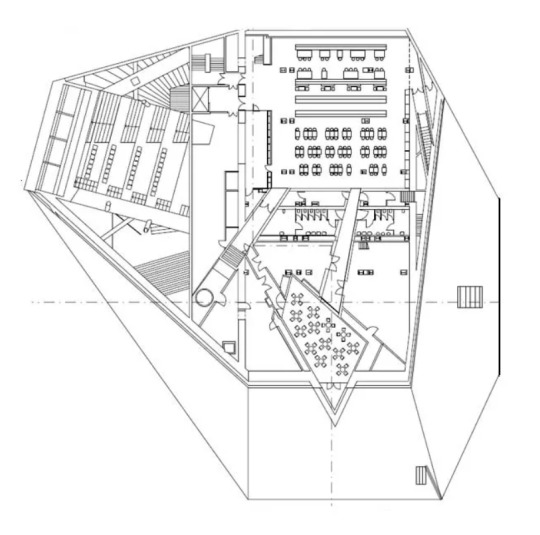

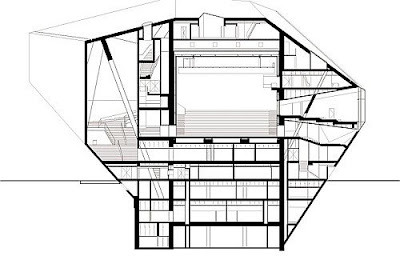

CASA DA MUSICA

Datos principales

→ Ubicación: Se sitúa en el perímetro de una de las grandes rotondas de Oporto, quedando así a la vista de cualquier persona.

→ Ciudad: Oporto.

→ País: Portugal.

→ Arquitecto encargado de la obra: Rem Koolhaas.

→ Fecha de construcción: entre 1999 y 2005.

Biografía del arquitecto

Remmet Koolhaas nació el 17 de noviembre de 1944 en Rotterdam, Holanda; trabajó como periodista y publicista antes de comenzar sus estudios de Arquitectura en la Architectural Association de Londres, donde estudió entre 1968 y 1972. Entre 1972 y 1975 ingresó en la Cornell University de Nueva York bajo la tutela de Oswald Mathias Ungers. En 1975 regresó a los Países Bajos y junto a tres socios fundó Office for Metropolitan Architecture.

En la década de 1990 Koolhaas llevó a cabo el plan urbanístico de Euralille en Lille que concluyó en 1995. Este incluye una estación de ferrocarril de alta velocidad, oficinas, comercios, apartamentos, hoteles, salas de exposiciones y auditorios. En 1995 publicó Small, Medium, Large, Extra-Large, una colección de artículos, manifiestos, diarios y cuadernos de viajes intercalados entre ilustraciones de los trabajos más recientes de OMA.

Entre sus obras destacan el Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Moscú en 2015, la Fundación Prada de Milán en 2015, la sede de la Televisión Central de China o la obra que estamos documentando; la Casa da Música de Oporto Library en 2005.

Rem Koolhaas sobresale por su teoría urbanista, ya que ningún arquitecto ha abarcado tanto.

En 2000 Koolhaas recibió el premio Pritzker, el galardón internacional más importante de arquitectura.

Descripción de la obra y su contexto cultural

En el año 1998, Oporto y Rotterdam fueron elegidas como Capitales Europeas. De cara al evento de 2001, se crearon programas artísticos y culturales para estas ciudades. En la ciudad de Oporto, el arquitecto Rem Koolhaas ideó la Casa de la Música. Al inicio fue un proyecto con polémica debido a que se pensaba que sería muy futurista y rompería con la estética tradicional de Oporto, pero, finalmente, ha acabado siendo uno de los edificios más emblemáticos de esta ciudad.

La casa de la Música tiene un aspecto poliédrico debido a que es como una gran caja a la cual se le han recortado los ángulos en distintas inclinaciones, situado en un gran perímetro explanado de mármol. Las entradas de este edificio se encuentran en los laterales y dan a un gran hall, por el cual podemos acceder a varias estancias rectangulares, salas de ensayo, restaurantes, una terraza y a las dos grandes salas de conciertos de este auditorio, unidas todas ellas por pasillos de hormigón ya que están pegados a la estructura del edificio. Las fachadas laterales del edificio dan a las salas de conciertos, hechas de vidrio corrugado, el cual se convierte como en un telón de fondo para las actuaciones. El edificio está construido con una gran variedad de diversos materiales como el hormigón armado, la piedra, diferentes metales, el acero, el vidrio, la madera y muchos azulejos portugueses. Es un gran edificio público y privado, con un aspecto futurista que contrasta con los edificios históricos de la ciudad de Oporto.

Alumnos redactores

Paula Cardona Riera

Antonio Cortés Bartolote

Bibliografía

→ Rem Koolhaas lleva la batuta en Oporto. (2019, April 26). Arquitectura Y Diseño. https://www.arquitecturaydiseno.es/relatos/edificios-imprescindibles-casa-da-musica_2567

→ LA CASA DE LA MÚSICA EN OPORTO. (n.d.). https://oa.upm.es/3075/2/CAPITEL_ART_2007_02A.pdf

→Casa da Música en Oporto: info, horario, precio y cómo llegar. (n.d.). Guía Nómada de Oporto. Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://www.oporto.es/que-ver/casa-da-musica/

→ Casa da Música - Sala de concertos, Porto, Portugal. (n.d.). Www.casadamusica.com. Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://www.casadamusica.com/en/

→Rem Koolhaas de escritor a arquitecto. (2021, July 12). Www.arquitecturaconfidencial.com. https://www.arquitecturaconfidencial.com/blog/rem-koolhaas/

1 note

·

View note

Photo

De Rotterdam

Rotterdam, The Netherlands (2013)

Architects: Rem Koolhaas, Ellen van Loon & Reinier de Graaf of OMA

↻ ʀᴇᴘʟᴀʏ ⇉ sᴋɪᴘ ♡ ʟɪᴋᴇ

95 notes

·

View notes

Photo

OMA, De Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands, 1997-2013 VS Pierre-Jean Mariette, Description des travaux qui ont précédé, accompagné et suivi la fonte en bronze d'un seul jet de la statue équestre de Louis XV, le Bien-Aimé, 1768

#oma#rem koolhaas#de rotterdam#rotterdam#Netherlands#skyscraper#tower#Pierre-Jean Mariette#collage#cut and paste#architecture

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

De Rotterdam by Rem Koolhaas, OMA (at Kop van Zuid) https://www.instagram.com/p/B8BphB5F9Xz/?igshid=odbh782nnx94

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

De Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands (2014) Architect OMA / Rem Koolhaas (2013) #residential #officebuilding #hotel #oma #remkoolhaas #Rotterdam (bij De Rotterdam)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Feyenoord Stadium, Rotterdam

Feyenoord Stadium, RotterdamSports Venue Project, Dutch Architecture News, Property, Image

Feyenoord Stadium in Rotterdam

6 May 2021

Feyenoord Stadium

Design: OMA

Location: Rotterdam, Holland

Fondly referred to as De Kuip (or the tub) in Rotterdam, Feyenoord’s stadium in the city’s south has been home to the Dutch football club for over eighty years. When completed in 1937, the stadium structure—built entirely with steel and concrete tiers and including a curved, cantilevered stand—was a forerunner in modernist football stadium.

Feyenoord’s current ambitions to further strengthen the football club, in combination with the municipality of Rotterdam’s plan to rejuvenate the area of Rotterdam-Zuid, have led to the development of the new Feyenoord Stadium as part of Feyenoord City—a masterplan designed to transform Rotterdam-Zuid into a well-connected and vibrant neighbourhood for sports, recreation, and living.

Over the past decades, stadium design has been evolving in response to football clubs’ new demands, including engagement with a larger supporter base, diversification of hospitality offerings, and development of commercial opportunities. For Feyenoord, various renovations of De Kuip between the 1950s and 1990s have offered immediate solutions to the needs of the football club to upgrade the football watching experience, and to increase its business and hospitality capacity.

While catering to Feyenoord’s changing needs, these transformations also compromised the stadium’s original design intent. The new Feyenoord Stadium—proposed by OMA, Feijenoord Stadium, and the Feyenoord football club—at a new location along the Nieuwe Maas and a highly accessible transportation node, is a future-proof infrastructure for football and daily activities in the surrounding communities.

The new stadium is an ensemble of essential elements: the stand, circulation cores, the structure, and functional spaces. Each element has been logically designed to maximise performance. The three-tier stand increases the capacity of the stadium to 63,000, while placing spectators as close to the field as possible for an intimate matchexperience. All seats have an above FIFA standard C-value that ensures clear and unobstructed views of the playing field.

Twelve concrete circulation cores, with different types of stairs and elevators inside, are evenly distributed along the perimeter of the stadium. This configuration allows a large number of visitors to efficiently move between the concourse and upper levels on event days. The bowl-shaped steel structure—a diagrid that requires less structural steel than a conventional steel frame—is the primary structure supporting the stand and its roof.

Functional spaces have been designed for specific users such as players, guests, and media. They also accommodate hospitality offerings including restaurants and multifunctional spaces.

All these elements have been assembled to form a stadium that is more than the sum of its parts: logical and functional as De Kuip and offering one of the best sightlines among stadiums of this scale, it is a truly open stadium with an public concourse on the main entry level. Designed in collaboration with LOLA Landscape Architects, this concourse is not fenced off but welcomes the public. With daily open F&B offerings, a playground, and greeneries, it is a space for football fans and the public to gather on match days, and for everyone to use for leisure activities when there are no events.

Distinctive from most contemporary stadiums designed as isolated icons—relevant only to football and detached from a city’s daily life—the new Feyenoord Stadium is a vital space in the Feyenoord City masterplan and open to public. By restoring the stadium’s historical role as a city’s significant public realm, it redefines the existing typology.

Feyenoord Stadium in Rotterdam, NL – Building Information

Design: OMA Status: Design Development Clients: Stadion Feijenoord NV, Feyenoord Rotterdam NV Location: Rotterdam Site: Rotterdam-Zuid Program: New football stadium Feyenoord 78.000sqm Feyenoord Stadium Team: Schematic Design: Partner-in-Charge: David Gianotten Associate-in-Charge: Kees van Casteren Project Architect : Shinji Takagi Team: Andrea Tabocchini, Andrew Keung, Aris Gkitzias, Emma Lubbers, Hanna Jurkowska, Lex Lagendijk, Max Scherer, Stefano Campisi

Design Development: Partner-in-Charge: David Gianotten Associate-in-Charge: Kees van Casteren Project Architect : Shinji Takagi Team: Alex Mortiboys, Aris Gkitzias, Andrea Tabocchini, Dagna Dembiecka, Eunjin Kang, Eve Hocheng, Gaetano Giordano, Giuseppe Dotto, Lex Lagendijk, Lucien Glass, Jingshu Li, MacAulay Brown, Marco Gambare, Maria Aller Rey, Matvei Osipov, Niccolo Cesaris, Vitor Oliveira, Vincent Kersten, Xianming Sang

Feyenoord City Team: Partner-in-Charge: David Gianotten Project Manager: Max Scherer Project Architect: Sandra Bsat Team: Alicja Krzywinska, Ana Otelea, Andrea Verni, Caterina Corsi, Marco Gambare, Marina Bonet

COLLABORATORS Project Management: Projectbureau Feyenoord City Landscape Architect: LOLA Landscape Architects Cost consultant: IGG Structure and MEP consultant: Royal Haskoning DHV Acoustics: Event Acoustics, Peutz Stadium Advise: The Stadium Consultancy Fire safety: DGMR Lighting: Philips Lighting Vertical Transport: Techniplan Facades: TGM Crowd Control Simulation: InControl Image Production: Beauty and The Bit

Image courtesy of OMA

OMA

Feyenoord Stadium, Rotterdam images/information received 060521

Location: Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Architecture in Rotterdam

Rotterdam Architecture Designs – chronological list

Rotterdam Architecture Walking Tours

Rotterdam Architecture

Also by OMA in Rotterdam:

De Rotterdam image courtesy of OMA; photography by Ossip van Duivenbode De Rotterdam

Stadskantoor Rotterdam Stadskantoor

Coolsingel Project Coolsingel Rotterdam

Rotterdam Architect Offices

Dutch Buildings

Office for Metropolitan Architecture

Rem Koolhaas architect

Selected Buildings by Office for Metropolitan Architecture

Shenzhen Stock Exchange by OMA

Singapore Tower

Netherlands Embassy Berlin

Hamburg Science Centre Building

Maison á Bordeaux

Comments / photos for Feyenoord Stadium in Rotterdam page welcome

Website: Rotterdam

The post Feyenoord Stadium, Rotterdam appeared first on e-architect.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

There’s no mistaking that the new Qatar National Library was designed by the Rotterdam office of OMA. Like a lot of @oma.eu’s built work, it is slightly odd, slightly off-putting, but impossible to ignore. And the building quite literally borrows from earlier OMA projects, most conspicuously from the Casa da Música in Porto, Portugal with its unusual crystalline geometry and large swaths of corrugated glass, and, inside, from the Bibliothèque Alexis de Tocqueville in Caen, France—though Rem Koolhaas would say otherwise about that. As Koolhaas described the design during a recent tour of the building, “We started with a square then lifted two corners.” The resulting structure appears like a rocky outcrop amid a bizarre hardscape of craters and faux mounds—by Dutch design firm Inside Outside—that might fit as easily on the moon as in this desert setting. Massive columns, nearly four-feet wide, protrude from the building’s concrete underbelly—where the main entrance is—to support the entire structure and its 80-foot-long sloping spans. Circling the exterior, the library changes appearance from different angles—the “pinched” corners are unquestionably the most intriguing aspect. Read more about this #AR_Project at http://ow.ly/hpLs30k8fDb Text by @minutillo_josephine Photo © Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti #oma #remkoolhaas #doha #contemporarydesign #interior #light #archidaily #arquitectura #architecture #architect #design #buildings #buildingdesign #Architektur #architettura #archigram #archilovers #archdaily #archilovers #architecturephotography #architecturalphotography #geometry #ig_architecture #pocket_architecture #archi_features #architecture_view #architecturelovers #architexture (at Doha)

#architecture#buildings#ig_architecture#architecturelovers#architect#ar_project#pocket_architecture#archilovers#contemporarydesign#architecturephotography#doha#archidaily#architettura#geometry#oma#architektur#interior#light#arquitectura#architecture_view#architexture#archi_features#remkoolhaas#archigram#design#buildingdesign#architecturalphotography#archdaily

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi, lovely ~ can you give something about the Netherlands to a soul who's wandering there in their dreams? ♡

You can see previous posts about the Netherlands following this link.

Here are some examples of the architecture in the Netherlands:

Rietveld Schröder House Gerrit Rietveld

Cube Houses

Rijksmuseum

Markthal RotterdamMVRDV

Witte Huis

De Rotterdam OMA / Rem Koolhaas

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

MODERNISMO EN ESTEROIDES

Luis Castillo Villegas

La instalación que OMA diseñó para la XVII La Triennale de Milán de 1986 es un proyecto poco conocido, pero transcendental en la trayectoria de Rem Koolhaas. Los organizadores de la Trienal, Mario Bellini y Georges Teyssot, invitaron a dieciocho arquitectos a reflexionar sobre “Il progetto domestico”, [“El proyecto doméstico”].(1) En torno a este motivo, OMA diseñó su particular versión de la “Casa Palestra” o la “Casa Gimnasio”. La palestra era el término con el que se designaba la antigua Grecia al edificio en el que se ejercitaban los deportes de lucha, como el boxeo o la lucha grecorromana. Su arquitectura gravitaba entorno a un gran patio central porticado alrededor del cual se desplegaban diferentes estancias accesorias. Derivado del griego y luego de latín, en italiano la palabra palestra designa hoy en día un gimnasio o centro deportivo. Koolhaas señala que con esta instalación intenta mostrar que “la arquitectura moderna es en sí misma un movimiento hedonista, que su severidad, abstracción y rigor son de hecho tramas para crear los entornos más provocativos en los que experimentar lo que significa la vida moderna”(2) y “sistemáticamente desarrollar un proyecto de la ocupación humana total relacionado con la cultura material en el mas amplio sentido de este término”.(3)

La arquitectura del Pabellón es muy simple en apariencia. Dado que el lugar asignado al arquitecto holandés para ubicar su instalación es la exedra semicircular del “edificio fascista de la Trienal”,(4) Koolhaas decidió insertar una reproducción “curvada” del Pabellón de Barcelona diseñado entre 1928-29 por Mies van de Rohe para la Exposición Internacional que tuvo lugar en esta misma ciudad. En el mismo año en el que se celebró la Trienal de Milán, concluyó la entonces controvertida reconstrucción del Pabellón de Mies que estaba teniendo lugar en el recinto ferial de Barcelona, dirigida por un equipo de arquitectos a cuya cabeza se encontraba Ignasi de Solà-Morales. Aunque la instalación de Koolhass para la Trienal pretendía ser una crítica irónica de la reconstrucción “a lo Disney” que estaba teniendo lugar en Barcelona, esta obra se convierte en una declaración de principios en la que emplea estrategias de diseño que constituye las base de su trabajo posterior.

En primer lugar, Koolhaas elige intencionalmente el Pabellón de Barcelona como punto de partida de su intervención. De todos los edificios proyectados por Mies, opta por este Repräsentationspavillon, dado que fue concebido como un espacio sin programa específico. A la vez una casa sin habitantes y un templo sin un Dios, el edificio de Mies carece de función, dado que su uso principal fue acoger por unos instantes la fugaz ceremonia de inauguración de la sección alemana de la exposición. Más allá de eso, no era más que la puerta de entrada al cuerpo principal de la exposición germana, compuesta en su mayoría por maquinaria y diversos ingenios que pretendían mostrar el poder industrial de la emergente potencia mundial.

Casa Palestra está diseñada como si estuviese en la cima de un rascacielos, un penthouse desde el que poder contemplar el skyline de una metrópolis norteamericana sin identificar.(5) Los materiales empleados en la construcción del pabellón son baratos, de poca calidad y de naturaleza temporal.(6) En lugar de acero cromado y las lujosas placas de mármol y ónice que Mies eligió con gran cuidado, Koolhaas utiliza paneles de viruta de madera de fibras orientadas, aluminio y metacrilato, materiales usados para construir la arquitectura ligera de los pabellones en las ferias comerciales. Aunque en este caso la elección de este tipo de materiales y el carácter provisional del pabellón podría explicarse como una metáfora de la condición efímera de esta instalación y de la propia modernidad, el empleo de este tipo de material barato y la construcción poco detallada, casi industrial, se convirtió en una seña de identidad de los posteriores proyectos de OMA.(7)

Koolhaas concibe el Pabellón pleno de “intensidad programática”(8) insertando máquinas de aire acondicionado, luces de neón, televisiones, proyecciones, altavoces, haces de luz láser y “un sinfín de tecnologías que intensifican el delirio de la metrópolis” en el deformado edificio Miesiano.(9) En la Casa Palestra hay una incómoda coexistencia entre la presencia de elementos domésticos como televisiones, columnas dóricas decorativas y ropa tirada por toda la casa, y su mezcla con confusos efectos visuales y sonoros, como voces grabadas, luces de neón y el uso predominante de la casa-gimnasio. Koolhaas acelera el espacio miesiano para intensificar sus características, mostrándonos cómo no solo cualquier uso, sino la superposición de programas diversos y efectos simultáneos puede alojarse en el espacio continuo y fluido que el arquitecto alemán creó. Esta actitud frente al binomio espacio-programa será una constante en los proyectos posteriores de Koolhaas.

Hay que considerar también los aspectos formales del diseño: Koolhaas dobla o curva el pabellón original de Mies para que encaje en el espacio semicircular que se le asigna dentro del edificio en el que se celebra la Trienal. En proyectos posteriores de Koolhaas, veremos cómo trozos y pedazos de edificios icónicos del movimiento moderno se insertan, manipulados formalmente de diversas formas, para intentar intensificar las características espaciales y formales de la arquitectura moderna. Esto es especialmente reconocible en sus primeros proyectos, como el Kunsthal de Rotterdam, por ejemplo, en cuya planta podemos identificar una versión hiperestimulada de la rampa de la Villa Saboya de Le Corbusier. En este mismo edificio, en la planta baja que mira hacia el parque trasero, Koolhaas envuelve las columnas en troncos de árbol en un gesto irónico que nos retrotrae a la arquitectura de Alvar Aalto y sus intentos de introducir la naturaleza dentro de sus edificios. El Kunsthal culmina con una sala de exposiciones miesiana, un espacio de planta libre y espacialmente continua que nos recuerda a la Neue Nationalgalerie de Berlín.

Desapercibido para la mayoría de los críticos y arquitectos,10 la decisión más simbólica que adopta Koolhaas en el diseño de Casa Palestra es la supresión de la escultura de Georg Kolbe, ubicada en el patio interior del Pabellón de Mies. Denominada “Der Morgen”, “La Mañana” o el “Alba”, como también es conocida, Koolhaas sustituye este bronce por una imagen del cuerpo desnudo de una fisicoculturista en una poderosa pose. Esta elección a la vez irónica e irreverente encarna la actitud de Koolhaas frente el Movimiento Moderno y sus intentos de esterilizar y desideologizar la arquitectura moderna. La escultura de Kolbe tenía un importante significado, tanto simbólico como político, como el crítico mallorquín Josep Quetglas nos descubre.(11) Su nombre “Alba”, o “La Mañana”, hace referencia en un momento concreto, en el que está saliendo un intenso sol de cuya deslumbrante luz se está protegiendo la figura femenina esculpida en bronce. El espectador puede pensar que es el penetrante sol vertical de un amanecer estival el que le está cegando. Pero, indagando con más profundidad en las asociaciones que nos provoca, ¿no sería legítimo pensar que esta figura femenina se está intentando proteger de la abrasadora luz producida por el nacimiento del poderoso, industrializado y moderno nuevo estado alemán que pronto se convertirá en una máquina para la guerra?

Georg Kolbe realizó numerosos encargos para el régimen nacionalsocialista alemán durante los últimos quince años de su vida. El régimen nazi vio reflejados en sus monumentales esculturas de cuerpos atléticos idealizados la expresión artística de la supremacía de la raza aria. Durante el periodo que va de 1937 a 1944, Kolbe realizó diversos trabajos para el régimen fascista alemán, incluyendo un busto del dictador Franco (el bronce más replicado del escultor germánico, una de cuyas copias le fue entregada a Hitler como regalo en 1939). Como Quetglas nos sugiere,(12) resulta casi imposible ignorar la naturaleza casi profética de esta escultura femenina: la piel llena de ampollas, quemada por una fuente de calor anormal, el miedo reflejado en sus brazos que la protegen de los horrores que presenciará en los años venideros. ¿Estamos ante una víctima de una catástrofe nuclear como la de Hiroshima? ¿Está siendo abrasada en una cámara de gas para convertirse en cenizas? ¿Está tratando de evitar contemplar la devastación y el genocidio del terrible régimen nazi?

Al suprimir la incómoda presencia de la escultura de Kolbe, Koolhaas esteriliza el Pabellón de Barcelona, borrando cualquier traza del régimen fascista y la incómoda cohabitación que Mies mantuvo con los nazis hasta 1939, cuando finalmente emigró a Estado Unidos para triunfar cuando el Movimiento Moderno y el Estilo Internacional que propugnaba se convertían poco a poco en el estilo representativo del capitalismo corporativo multinacional. Es muy probable que Koolhaas conociese el simbolismo de esta escultura, y por ello decidiese remplazar la obra de Kolbe. Pero ¿por qué elegir la imagen de una fisicoculturista? Obviamente siempre tendremos la interpretación en clave feminista: la temerosa y vulnerable mujer de la escultura de Kolbe, con su cuerpo de delicadas proporciones neoclásicas que se protege de la cegadora luz solar, se remplaza con el cuerpo poderoso, masculino, exhibicionista y muscular de la mujer culturista.

Podemos también encontrar una actitud provocadora y transgresora en la elección de esta figura desinhibida para sustituir la frágil mujer de la escultura de Kolbe. Pero fundamentalmente nos encontramos ante una declaración de profundo cinismo e ironía. Los curadores querían que Koolhaas reflexionase sobre la relación entre la arquitectura moderna y el ejercicio físico: “recuerda el dormitorio con un saco de boxeo de Edwin Piscator”(13) diseñado por Marcel Breuer; o “el gimnasio de Walter Gropius en la exposición de Berlín del año 1931”, le sugerían al realizarle la invitación para tomar parte de la trienal.14 Los arquitectos del Movimiento Moderno, como Le Corbusier, creían en la capacidad atlética y la salud que la práctica del deporte aporta al “nuevo hombre moderno”, personificado en el boxeador que aparece en sus bocetos habitando el interior de los Immeuble-Villas. Para el Movimiento Moderno, el deporte y el bienestar físico era parte fundamental de una nueva y mejor humanidad.

En cambio, como representante de la arquitectura neomoderna, Koolhaas elige el fisicoculturismo como la actividad icónica que simboliza la sociedad actual: aunque se considere un deporte, ésta puede ser una de las prácticas más insanas y dañinas a las que podemos someter a nuestro cuerpo, que se ve envuelto en una masacre metabólica en el empeño de ganar masa muscular a toda costa, incluso produciendo daños irreparables a los órganos vitales por el consumo de esteroides anabolizantes y otras drogas para incrementar la productividad del organismo. El cuerpo de la culturista lo podemos interpretar como un símbolo de la ideología de OMA en los años posteriores: el cuerpo de la arquitectura moderna mejorado artificialmente mediante la bioquímica y el ejercicio intensivo, un símbolo de la hipermodernidad. La figura representa el deseo de manipular, incrementar, intensificar y modificar su cuerpo. Koolhaas ha sido designado, y con cierta razón, como el arquitecto más relevante del capitalismo postindustrial y el liberalismo económico globalizador. El iniciador y más relevante exponente de la arquitectura pragmática basada en los “datos” y desprovista de ideología. Como los fisicoculturistas, Koolhaas parte del cuerpo de la arquitectura moderna para transformarlo, acelerando e intensificando sus características mediante una fe ciega en la economía de mercado, el liberalismo socioeconómico y la globalización, de manera que lo transmuta en la representación construida de la hipermodernidad. La obra de OMA la podríamos resumir, de alguna manera, como de modernidad en esteroides.

______________

1. Georges Teyssot, Mario Bellini, Il Progetto Domestico: La Casa dell'Uomo Archetipi e Prototipi. Progetti, Electa, Milán, pp. 9-13. 2. OMA, “La casa palestra”, AA Files 13 (Fall 1986), pp. 8-12. 3. Ibid. 4. Rem Koolhaas, Bruce Mau, Hans Werlemann, S, M, L, XL, The Monacelli Press, Nueva York, p. 49. 5. Roberto Gargiani, Rem Koolhaas/OMA The Construction of Merveilles, Lausana, EPFL Press, p. 124 6. Urtzi Grau, “Three replications of the German pavilion”, Quaderns nº 263, 2011, p. 62 7. Jeffrey Kipnis, “Recent Koolhaas”, El Croquis nº 79, 1996, p. 28. 8. Urtzi Grau, p. 62. 9. Ibid. 10. De todos los críticos que han escrito sobre el pabellón de la Trienal, solo Urtzi Grau menciona brevemente que la escultura de Kolbe ha sido sustituida por la figura de la fisicoculturista. 11. Josep Quetglas, “Fear of Glass-Mies van der Rohe's Pavilion in Barcelona”, Birkhauser, 2001. 12. Quetglas, p. 185. 13. Georges Teyssot, Mario Bellini, op.cit. 14. Ibid.

* Este texto fue publicado en su versión original en inglés bajo el título “Modernism on Steroids” en la revista OASE #94/ OMA. The First Decade (nai010 Publishers, Rotterdam, 2015).

** Materiales concretos agradece al Departamento de Relaciones Públicas de OMA los permisos de reproducción del collage que acompaña el texto.

DESCARGAR EN PDF

0 notes

Video

De Rotterdam, Rotterdam by Peter Westerhof Via Flickr: Architect: Rem Koolhaas, OMA (2014)

#De Rotterdam#Rotterdam#verticale stad#architect#rem koolhaas#koolhaas#OMA#architectural photography#architectuurfotografie#kantoor#hotel#appartementen

0 notes

Text

Journal - 10 Landmark Architecture Projects by OMA

Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.

The Office for Metropolitan Architecture is a landmark practice. OMA was founded in 1975 by Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis, along with Madelon Vriesendorp and Zoe Zenghelis. Since then, the team has become known for visionary solutions that upend programmatic convention. Understanding design as a process, OMA has shaped how we understand architecture and design around the world.

Drawing on the firm’s more recent portfolio of work, the following projects were built within the last five years. Showcasing critical and rigorous design concepts, they are made with a wide variety of programs at diverse scales. Sited around the world, the collection begins to illustrate OMA’s impact on architecture and urbanism with different materials, forms and spaces. Together, they also represent the practice’s conceptual approach to a wide array of typologies.

Taipei Performing Arts Center, Taipei, Taiwan

TPAC consists of three theaters, each of which can function autonomously. The theaters plug into a central cube, which consolidates the stages, backstages and support spaces into a single and efficient whole. This arrangement allows the stages to be modified or merged for unsuspected scenarios and uses. The design offers the advantages of specificity with the freedoms of the undefined.

Concrete at Alserkal Avenue, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Located in Dubai’s Al Qouz industrial area, Alserkal Avenue was founded in 2007 with the aim of promoting cultural initiatives in the region. Since then, it has become Dubai’s most important art hub with twenty-five galleries and art spaces. Concrete, a new venue, addresses the districts growing need for a centrally located public space which can host a diverse program.

Pierre Lassonde Pavilion, Québec City, Canada

The Pierre Lassonde Pavilion—the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec’s fourth building is interconnected yet disparate—is an ambitious addition to the city. Rather than creating an iconic imposition, it forms new links between the park and the city, and brings coherence to the MNBAQ. In order to respond to context while clarifying the museum’s organization and a adding to its scale, new galleries were stacked in three volumes of decreasing size.

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow, Russia

A dramatic renovation of the 1960’s restaurant on site, the Garage Museum is a center for contemporary art in Moscow. The museum program includes galleries, a shop, café, roof terrace, auditorium and offices. A new translucent polycarbonate façade wraps the original structural framework and is lifted off the ground, allowing views between Gorky park and the exhibition space inside.

The Design Museum, London, United Kingdom

OMA with Allies and Morrison were the architects responsible for the design of the refurbished structural shell and external envelope of the building. The project required a close working relationship with Design Museum interior architects, John Pawson. Significant and complex refurbishment works were carried out, including the wholesale reconfiguration of the structure and basement excavation to increase floor area and organizational efficiency to suit the needs of the Design Museum.

Timmerhuis, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Timmerhuis was designed as a new municipal building for the city hall that combines residential and administration space. Formed as modular units that work within an innovative structural system, the building was designed to be the most sustainable building in the Netherlands. OMA accomplished this through the building’s core concept of flexibility, and also through the two large atriums that act like lungs.

Il Fondaco Dei Tedeschi, Venice, Italy

First constructed in 1228, and located at the foot of the Rialto Bridge across from the fish market, the Fondaco dei Tedeschi is one of Venice’s largest and most recognizable buildings. OMA’s restoration of the building was commissioned by the Benetton family in 2009 to transform the 9,000-square-meter structure into a department store, now under a leasing agreement with Hong Kong-based DFS.

New Museum for Western Australia, Perth, Australia

Located in the heart of Perth’s cultural precinct, the Hassell + OMA design was conceived as a ‘collection of stories’, offering a multidimensional framework to engage with Western Australia. A holistic building, comprised of heritage and new structures, the New Museum for Western Australia will be a place where the local community and global visitors gather.

Lujiazui Harbour City Exhibition Centre, Shanghai, China

The Lujiazui Harbour City Exhibiton Centre is located on the northern and most recent development of Shanghai Pudong, along the Huangpu River, one of the most photographed waterfronts in the world. The new Exhibition Centre is positioned on the ramp of a former ship cradle and provides a concentrated event space within the surrounding financial district.

Galleria, Yeongtong-gu, Suwon, South Korea

The store in Gwanggyo—a new town just south of Seoul—is the sixth branch of Galleria. Located at the center of this young urban development surrounded by tall residential towers, the Galleria’s stone-like appearance makes it a natural point of gravity for public life in Gwanggyo. The store has a textured mosaic stone façade that evokes nature of the neighboring park.

Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.

The post 10 Landmark Architecture Projects by OMA appeared first on Journal.

from Journal https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/collections/landmark-oma-projects/ Originally published on ARCHITIZER RSS Feed: https://architizer.com/blog

#Journal#architect#architecture#architects#architectural#design#designer#designers#building#buildings

0 notes

Text

118. Oliver Wainwright

Oliver Wainwright a writer and photographer based in London. He has been the architecture and design critic of the Guardian since 2012. He trained as an architect at the University of Cambridge and the Royal College of Art, and worked in strategic planning at the Architecture and Urbanism Unit of the Greater London Authority and at a number of architecture practices, including OMA in Rotterdam and Muf in London. In this conversation, Oliver and Jarrett talk about the relationship between writing and architecture, the tensions between practice and criticism, and what it means to write for a major newspaper.

Show Notes:

Oliver Wainwright

@ollywainwright

Oliver's archive on The Guardian

OMA/AMO

114. Reinier de Graaf | Scratching the Surface

Four Walls and a Roof - Reinier de Graaf

Rem Koolhaas's De Rotterdam: cut and paste architecture - Oliver Wainwright

Mass Design Group

Michael Sorkin

110. Sam Jacob | Scratching the Surface

Snapping point: how the world’s leading architects fell under the Instagram spell - Oliver Wainwright

Super-tall, super-skinny, super-expensive: the 'pencil towers' of New York's super-rich – podcast - Oliver Wainwright

Inside North Korea

Inside Facebook and friends: a rare tour around tech's mind-boggling HQs - Oliver Wainwright

Nairn's London - Ian Nairn

Ian Nairn's Outrage columns

Rowan Moore

96. Christopher Hawthorne | Scratching the Surface

Owen Hatherley

A.A. Gill

Download mp3 | Soundcloud | Apple Podcasts | Google Play | Spotify

0 notes

Photo

De Rotterdam by Rem Koolhaas, OMA. (at Kop van Zuid) https://www.instagram.com/p/B8yEmX5FjZz/?igshid=ks6d81g1rkxz

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

De Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands (2017) Architect OMA / Rem Koolhaas (2013) #officebuilding #hotel #residential #remkoolhaas #rotterdam (bij De Rotterdam)

0 notes

Text

OMA builds metal and glass campus headquarters for Tencent in Beijing

OMA has housed the Tencent Beijing Headquarters in China within a giant glass building that is punctured by geometric insets and has interiors that mimic a small city.

Located at the edge of Zhonguancun Software Park in Beijing, the seven-storey office was designed to accommodate Chinese technology company Tencent's thousands of employees, without resorting to building a skyscraper.

Tencent Beijing Headquarters in Zhonguancun Software Park

Tencent Beijing Headquarters is described by OMA as a city, divided into nine independent zones across its seven vast floors. Each floor measures 180 metres in length and width.

To reduce the building's visual impact, its form is softened by the removal of its corners, which mark entrance points, and large geometric insets that are lined with brushed metal.

Metallic insets puncture the facade

"Instead of seeking soaring heights to host the expansion of the digital workforce, OMA designed a square-shaped floating volume of merely seven floors that stretches out horizontally," explained the studio.

"Tencent Headquarters is a city in a singular building – the campus allows for unique manipulations not possible within the limits of typical traditional offices."

The insets help soften the building's form

Like in a city masterplan, a connection to the outdoors plays a key role in OMA's design of Tencent Beijing Headquarters. This is achieved in part with three triangular courtyards that plummet through its centre to bring in natural light and ventilation.

Outside, a network of paths that are interspersed by green spaces and areas for outdoor activities has been established to connect each zone.

A more private outdoor space has been incorporated at roof level, forming a green belt around the top floor that is set back from the building's perimeter.

Tencent Beijing Headquarters' rooftop garden

The interiors of Tencent's headquarters, which have not been photographed, were designed in collaboration with Woods Bagot.

According to OMA, each of the nine zones are designed to function independently using their own service core, but are connected via a "web of intersecting streets".

The zones are also each subdivided into smaller areas, which are all visually connected and host a different programme or activity.

An entrance that frames the headquarters' interiors

OMA is a Dutch architecture studio that was founded in 1975 by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas. Today it has offices in Rotterdam, Hong Kong, Beijing, New York, Dubai, Doha and Sydney.

Tencent Beijing Headquarters is one of several buildings in China undertaken by the studio, including the CCTV building, the Prince Plaza skyscraper and the upcoming Xinhu Hangzhou Prism.

Elsewhere in China, Zaha Hadid Architects is currently designing the amorphous OPPO Shenzhen headquarters and MVRDV is converting a disused factory into creative office space.

Photography is by Ossip van Duivenbode, courtesy of OMA.

Project credits:

Architect: OMA Client: Tencent Partner in charge: Rem Koolhaas and David Gianotten Associate: Adam Frampton and Ravi Kamisetti Project leader: Patrizia Zobernig Team: Kathleen Cayetano, Vanessa Chan, Hin Cheung, Yin Ho, Jedidiah Lau, Kwan Ho Li, Vivien Liu, Kai Sun Luk, Kevin Mak, Cristina Martin de Juan, Arthas Qian, Saul Smeding, Benny Tam, Arthas Qian, Hannah Zhang, Casey Wang with Helen Chen, Jocelyn Chiu and Stella Tong Chinese co-architect: BIAD Structure, HVAC/MEP/Electric, Traffic, BIM: BIAD, AECOM Interiors: Woods Bagot Landscape: Inside Outside, Maya Lin Studio and Margie Ruddick Landscape Facade: VS-A, Beijing Zizhou Architecture Curtain Wall Design Consulting Broadcast: Radio, Film & TV Design and Research Institute Lighting: Beijing Ning Field Lighting Design Corp., Ltd. Fire engineering: Tianjin Fire Research Institute of M.E.M., China Academy of Building Research Institute of Building Fire Research Acoustics: DHV Sustainability: Dad Daring Kitchen Consultant: Compass

The post OMA builds metal and glass campus headquarters for Tencent in Beijing appeared first on Dezeen.

0 notes