#Dartington Outing

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

How Deborah Levy can change your life

From her shimmering novels to her ‘living autobiographies’, Deborah Levy’s work inspires a devotion few literary authors ever achieve

Last August, the author Deborah Levy began to sit for her portrait. The starting point was a selfie – eyes penetrating, lips sensuous, head topped by a tower of chestnut hair. The artist, her friend Paul Heber-Percy, used Photoshop, then a pencil and tracing paper, to reverse and multiply the image of her face, until he had a drawing, neatly laid out on a grid, that satisfied him.

Then it was time to paint. He liked to work in the mornings, in hour-long bursts, in his tiny attic studio. When Levy came for sittings, he’d bring the painting down to the dining room, and the two of them would drink tea or wine, and talk. Not that these were sittings in the traditional sense, but “times I could observe her without feeling self-conscious”, he said.

Sometimes they’d discuss Levy’s new novel, August Blue, which she was finishing; but mostly it was “everyday things – friends, the news, exchanging recipes, how to unblock a sink”, said Levy. But, Heber-Percy said, nothing about these conversations was really everyday. She is the sort of person who makes the mundane remarkable. Even “going down to the bakery with her to get a baguette becomes a slightly magical thing”, says her friend the novelist Tash Aw. When her friends talk about her, they say things like this: “she is an event”, “she is a personage”, “she is a whole world”. People often remember the first time they met her. For Kate Bland, an audio producer, it was at a party at a Shoreditch warehouse. Levy was sitting on a high windowsill; Bland was leaning on it. The author’s rich, slightly breathy voice was coming over Bland’s shoulder. Talk unwound in a sequence of dazzling vignettes. “It seemed that there was a necessary theatricality: we had to hoist ourselves out of the ordinariness of chat and have a conversation that was going to be memorable,” she recalled. “I was quite thrilled by it.”

At the time of that party, in 2008, Levy was 49. Her life had contained one immense dislocation: when she was nine, her family emigrated from South Africa to the UK, after her father had spent three years as a political prisoner. After school at a London comprehensive, Levy took a theatre degree at the pioneering, avant-garde Dartington College of the Arts in Devon, and first forged a path as a playwright. Her first novel, Beautiful Mutants, was published in 1989, the year she turned 30. Twenty years on, at the time of the Shoreditch party, she wasn’t famous, and hadn’t sold more than a modest number of books, though she carried herself as if she had. She was teaching, adapting Colette and Carol Shields for the radio, raising two daughters, and living with her husband, playwright David Gale, in a semi-detached house off Holloway Road in north London. She was working on a novel, her first since 1996. Her previous books were out of print.

Four years later, Levy’s life was transformed. Her novel, Swimming Home – a sun-drenched story about a family holiday on the French Riviera, beneath whose glinting surface runs a Freudian riptide of wartime trauma – was shortlisted for the 2012 Booker prize. That sent sales flying. At the same time, her marriage fell apart. “By the time I went to the Booker dinner in December I knew I would be moving house and I was packing up,” she recalled. “It was very turbulent and very painful.”

The following year, she published Things I Don’t Want to Know, the first in a trilogy of what she calls “living autobiographies”, to convey their selective, fictive nature. Over the next few years, she alternated two more novels, Hot Milk and The Man Who Saw Everything, with two more volumes of living autobiography, which spoke of how, after her marriage ended, she recomposed a life for herself and her daughters in her 50s, outside the old patriarchal structures. All of these books, flew out of her “like a cork coming out of a bottle”.

Levy’s novels are popular and critically acclaimed. But it is with the living autobiographies that her reputation has transcended the literary. At events, readers tell Levy that her books make them feel less lonely, or ask her what to do about a life crisis. (One can’t quite imagine readers doing this with, say, Rachel Cusk, who also anatomises female experience, but in a somewhat chillier style.) At one of Levy’s online readings during the Covid pandemic, an audience member posted in the chat: “I’m 41 with two kids and sometimes I don’t feel I’m at home at all … Did it work for you, coming out of an unhappy marriage?” Levy answered: “It did work for me. You have to make another sort of life and gather your friends and supporters to your table” – which is pretty much the story of the second and third of her living autobiographies, The Cost of Living and Real Estate.

Levy’s writing has a very particular quality: it seems to infiltrate the mind. You absorb her way of seeing and start to perceive the world in Levy-ish ways. In her stories, seemingly trivial moments take on political force: an encounter with a hairdresser in The Cost of Living becomes a story about the camaraderie of women and what they reveal to each other; a scene about sharing a table on the Eurostar becomes about how men, literally and figuratively, fail to make space for younger women. In the new novel, August Blue, the narrator, having been insulted by a young man in a cafe, tells us, “I think he was expecting me to respond, to reply in some way, but I didn’t care about him or his problems.” I’ve used that in my own life more than once, since first reading it. The books become “almost a guide to life”, said Gaby Wood, director of the Booker Foundation. “She trains you to become your best self.”

Part of the appeal of Levy’s writing is that it is shot through with unpatronising sympathy towards younger women – both the hesitant, tough young female characters who populate her novels, and those who appear in her living autobiographies, often negotiating sticky situations with older, entitled men. In Real Estate, there is a passage in which she describes her joy in cooking for her daughters’ friends: “I liked their appetite – yes, for the dish prepared, but for life itself. I wanted them to find strength for all they had to do in the world and for all the world would throw at them.” She is not just talking about her daughters’ friends. Levy is also in the business of feeding and strengthening her readers. And they feel it.

The plays and the novels Levy wrote in her 20s and 30s are collage-like, gravelly, spiky, and dense, marinated in the eastern European avant-garde influences she absorbed at college. She had a talent for epigrammatic, slightly surreal sentences. “I once heard a man howl just like a wolf except he was standing in a phone box in Streatham,” says a character in her first novel. But the work had not yet acquired the razored-away, spare quality that has given the later work such airiness, such ripple and flow, nor was there the emotional force with which readers identify so strongly.

It was in the late 2000s that she forged the style that transformed her reputation. She was working at the Royal College of Art at the time. Two days a week, she’d take the tube from the fumes of Holloway Road to green South Kensington. She was a tutor in the animation department, helping students learn to write and construct narrative. “It was a potent time,” she said. Her colleagues at the Royal College of Art were inspiring; so were her students. At nights, while her young daughters slept, she was writing Swimming Home. “I was somehow living closer to my own emotions and understood that I might be able to put them to work in my book.” She had always felt that emotion was frowned upon by her avant-garde art “family”, but “from Swimming Home onwards, I decided to totally up-end that”. Charging the story with feeling changed her writing – and her relationship with readers. “I knew I was on to something, and it rocked me,” she recalled. “There were times when I’d stop writing and I’d come down to cook my daughters spaghetti in the evening. There was a sort of cool place under the steps, and I was so on fire, I would just stand there and cool down.”

What Levy found in her writing was a way of giving her story a shimmering, attractive surface, while allowing her preoccupations with literary theory, myth and psychoanalysis to occupy its murkier depths. The novel can be taken as “a kind of holiday novel gone wrong”, she said – and it has been slipped into many a suitcase as a beach or poolside read. “I’m happy if the surface is read. Because everything else is there to be found. And I’m working hard for my readers to find it. But I don’t look down on readers who don’t. I think, ‘Something will come through.’” The “something” might include the Freudian desire and death-wish that suffuses the novel; its peculiar linked imagery of sugar mice and rats; above all the immense treacherous undertow of history – of the Holocaust, of 20th-century suffering and wars – that Levy sketches into the story with almost imperceptible strokes.

But Swimming Home was rejected by every major publisher it was sent to. Levy, in all her certainty that it was good, was devastated. The years following the financial crisis of 2008 were inhospitable to a midlist novelist who hadn’t been in print for a while. The publishing industry was in trouble; the powerful new wave of feminism of the 2010s was a whisper rather than a roar; and the kind of spare, experimental books by women that would come to define recent literary trends, such as Cusk’s auto-fictional Outline trilogy, or Annie Ernaux’s intimate unfurling of memory, or Elena Ferrante’s revelatory novels on female friendship, had yet to appear in Britain. At the time, she said, “your book was either going to sell or it wasn’t going to sell, and when they said it was ‘too literary’, they meant it wasn’t going to sell”.

Then, in summer 2009, something changed. A friend of Levy’s, the late Jules Wright, who ran an arts centre in east London, read the manuscript. She was organising a show on photographer Dean Rogers, who documented the sites of car crashes that had killed cultural heroes – the spot, for example, where Marc Bolan died. Swimming Home begins with a scene in which Kitty Finch, a young woman with a death wish, perilously drives an older poet, with whom she believes she has a telepathic connection, along a winding mountain road. Wright decided to have the first two pages of the book printed large and installed at the beginning of the exhibition. Not long after the opening, though, she called Levy and bluntly announced she was removing them. It was a disaster, she said – people were clogging the entrance as they stopped to read the text. “It was,” Levy said, “the first spark: that those two pages of this much-declined book were gathering a crowd around them.”

Eventually the novel did find its publisher, a tiny new press called And Other Stories. The literary translator Sophie Lewis was editor there. Levy’s pitch, remarkably given all the rejections, was supremely confident. “Deborah said: ‘This is the tightest book I’ve ever written, and it’s going to be a bestseller,’” Lewis remembered.

In autumn 2011, Levy’s friend Charlotte Schepke, who runs Large Glass gallery in London, hosted the launch party. They decided to project The Swimmer, the 1968 Burt Lancaster film, on to the wall. On the night, to Schepke’s immense surprise, “you couldn’t stand – the place was absolutely packed. It was rammed.” Her interesting new friend, who had written witty labels for the opening show at her small gallery earlier that year, was suddenly making waves. It was almost, said Schepke, “as if she’d done this grand thing of claiming to be an author – and then, suddenly, she really was an author”.

In her living autobiographies, Levy frequently refers to her rented shed, a writing space in a friend’s garden, on whose roof the apples used to fall in autumn with a dull thunk. These days, as she moves deeper into her 60s, the shed has been replaced by an attic in Paris, a few blocks behind the bookshop Shakespeare & Company, near the Seine. On a limpid blue February day, she had pinned a branch of yellow mimosa to her front door. Its flowering marked, she said, the “end of gloomy, rat-grey January”.

The studio was as near to the platonic ideal of a Paris garret as you could imagine: reached by a winding stair through a courtyard, and with low ceilings and wooden beams. Kilim rugs were scattered on the floor, and her bed was covered in a fluffy sheepskin throw. There was a stash of red wine in the fireplace. Everything about the studio radiated her delight in objects and food and pleasure. If you met the author and saw the studio before you read the work, you might expect something more excessive and elaborate than the stripped-down, translucent prose she produces.

She poured coffee from a moka pot and passed me a dish heaped with croissants from her local boulangerie, La Maison D’Isabelle; pastries from the same shop turn up in the new novel. Objects from her real world often slip into her fiction. There was a biography of Isadora Duncan face-out on a shelf, perhaps the same book about the dancer she has her character Elsa read in August Blue. On a table stood a bowl of pearl necklaces, and at her throat were pearls – like the pearl necklace she has her beautiful, careless character Saul wear in her novel, The Man Who Saw Everything.

Things in her stories often hold the kind of powerful significance that Freud attaches to artefacts in dreams – such as the pool in Swimming Home, which, at its most basic, Levy pointed out, is a rectangular hole in the ground, and thus also metaphorically a grave. She loves the surrealists. The turning point of Hot Milk is the moment when her narrator, Sofia, discovers boldness through making bloody handprints on the kitchen wall of a man who has been tormenting his dog – a scene borrowed from a story told about the artist Leonora Carrington who, letting herself into the apartment of her prospective lover Luis Buñuel, smeared menstrual blood over his pristine white walls.

Motifs slip between books, too; in this she has something in common with a visual artist building a subtly interconnected body of work. The title August Blue, for example, is taken from the colour of the thread that, in Hot Milk, one character Ingrid uses to embroider Sofia’s name into a shirt. Horses, in particular, gallop through Levy’s work – from the tiny horse-shaped buttons that, in Real Estate, she kept from her late stepmother’s button box, to the moment Ingrid appears in the desert landscape on horseback, like a bellicose goddess, in the myth-infused Hot Milk. The whole of August Blue hangs on striking images of horses: it begins with her character, the pianist Elsa, watching jealously as a woman she thinks might be her doppelganger buys a pair of mechanical dancing horses in an Athens flea market.

Levy laughed when I asked her about her equine enthusiasms. “That’s a case for Dr Freud!” she said. She ponders, in Real Estate, what it is to be a woman “on your high horse”. Sometimes, she writes, you might find yourself incapable of controlling your high horse; at other times, people are all too eager to to pull you off it. She imagines a friend riding her high horse “down the North Circular to repair her smashed screen at Mr Cellfone”. When I think of Levy’s horses, I also think of her adoration of her small fleet of e-bikes, now famous from her living autobiographies, which she stables by her London flat and lends to friends when they visit; she bought her first when she moved out of her marriage and into her new life. When they start up with a little equine surge of power, she told me, “it’s hard not to whoop every time”.

When Levy was a small child in South Africa, and her father, Norman Levy, was imprisoned for his anti-apartheid activism, she started to speak so quietly that her voice became barely audible. What saved her from this state of virtual silence was her imagination: the dawning understanding that she could write other realities. “It was a question,” Levy told me, “of finding avatars.” The avatar she created for her nine-year-old self was a cat with wondrous powers of flight – perhaps unconsciously imagining freedom for her father, as well as liberation for herself. (In Real Estate, The Flying Cat is the name she gives to the ferry that brings her daughters to her for a holiday on a Greek island.) The characters in her fiction are still her avatars. “I’m in every one of them,” she said, “including the cats and including the horses.”

For a long time, in adulthood, she resisted writing or even talking about South Africa. The difficulties of her family felt irrelevant, when set against the struggles of black South Africans. But since she had decided to base the structure of Things I Don’t Want to Know on George Orwell’s headings in his essay Why I Write – one of which is “historical impulse” – she found herself obliged to tackle those repressed memories. Using a child’s eye view, she said, “I tried to convey, without using the old language of ‘the bloodstained regime of apartheid’, what it’s like to be told that you’re supposed to respect adults, while there are white adults who are clearly doing very cruel things to children of colour my age.”

Her mother, Philippa, through her husband’s imprisonment, coped alone, earning a living through a succession of secretarial jobs. Levy remembers her as capable and glamorous. “I loved the way she cooked, with her cigarette holder, and the way that she’d dance a bit to the record she’d put on when she came back from work.”

When Levy’s father was released in 1968, he was banned from working, and the family – Levy has an elder half-brother from her mother’s first marriage, as well as a younger brother and sister – had little option but to emigrate. Her father found work lecturing at Middlesex University, among other places. Money was tight. Her parents’ marriage ended in 1974.

After the “blue sky, and the bone-white grass of the garden” in Johannesburg, arriving in London felt “as if someone had pulled the plug out”. But despite England’s greyness, she loved it. She made, for the first time, proper friends. “I don’t have that narrative of exile, of wanting to return to the place that you left”. She adored the way people spoke, and she still delights in English turns of phrase: “Hello pet, hello lamb, hello duck.” As for her accent, “I had to lose it very quickly in the playground not to be beaten up.”

She often plucks her characters out of their familiar environments, partly in order to see their psychological foibles magnified on foreign shores. (She herself likes very much to be in a hot country, in southern Spain or a Greek island, swimming in the sea.) Sometimes these characters, like her, have been swept on the tides of 20th-century history – like the English poet Joe in Swimming Home, who is really Jozef, smuggled out of Łódź in 1943; or Lapinski in Beautiful Mutants, whose mother was “the ice-skating champion of Moscow”. Levy recalled of an interview in the news that moved her recently: it was with a Ukrainian woman from Kherson who had been lying in bed, thinking, when she was blown into her kitchen by a Russian shell. “Those were her words: ‘I was lying in bed, thinking,’” said Levy. “I do not take a place of calm, a place that is agreeable to think in, for granted.” Levy’s senses are finely tuned to the fragility of things.

After her A-levels, in the summer of 1978, she would walk past the Gate cinema in Notting Hill, timidly noting the thrilling, eccentrically dressed people who hung out there. One day, she saw an ad in the Evening Standard for front-of-house staff. For the interview, she put on a pair of big, gold platform wedges; as she left the house, her mother yelled, “‘You’ll never get a job dressed like that.’” Those gold wedges are the ancestors of the shoes that have carried her female characters on to victory, or else to triumphant defeat: the silver gladiator sandals that Ingrid, like the goddess Athena, straps high up her calves in Hot Milk; the sage-green Parisian tap shoes that get her into a scrape in Real Estate; the brothel creepers that, to her younger self, “marked me out for a meaningful life”; and the “scuffed brown leather shoes with high snakeskin heels” that we meet on page three of August Blue.

She got the job at the Gate. Her new colleagues were “either at drama school or off to university, and all way cooler than me. I was a nerdy writer” – of poetry, at the time – “with a great love of Bowie.” The cinema was screening Derek Jarman’s film Jubilee, “and he would come in, and he was curious and charismatic and friendly and cultured and he didn’t feel above talking to this 18-year-old making the popcorn, tearing the tickets and scooping the ice cream”. It was Jarman who told her she should apply not to university but to Dartington, where she’d learn about improvisation and dance and avant-garde theatre and art.

It was at this time, not having the kind of parents who dragged her round galleries at weekends, that she encountered contemporary art for the first time. It was an exhibition of the work of Joseph Beuys. She remembers, a grand piano muffled and covered with cloth marked with a cross; other objects made of gold leaf; dried plants tacked to the wall; things scribbled in pencil. “I remember almost not being able to breathe. And there was this voice inside my head, saying, ‘This is it. This is it.’ And I had no idea what it was.”

The Cost of Living opens with the narrator witnessing an encounter between a young woman and an older man in a bar in Colombia. The man, whom Levy calls “the Big Silver”, invites the young woman to his table. After she tells him a strange story about a perilous diving expedition, he remarks that she talks a lot, and carelessly knocks her book off the table. Levy writes: “It had not occurred to him that she might not consider herself to be the minor character and him the major character.” It is a very Levy-ish story, in its wry observation of dynamics between men and women, and with its implicit call to arms to women who have, as the critic Dwight Garner has put it, “come to sense they’re not locked into their lives and stories”.

Levy herself is without doubt a major character – and is intent on expanding the role. She has an immense appetite “for experiencing the strange dimensions of living and the absolutely practical dimensions”, she said. We were sitting, at the time, outside a cafe near the Panthéon in Paris after a good lunch, and Levy was smoking a roll-up. “I’m not endlessly open to experience. I am easily bored and impatient. I want to keep things moving, keep thought moving. I want to make something new of the old story. How do you make the novel as complicated as life, as interesting as life? That’s what I want to do.”

She has many plans. She wants to adapt her two most recent novels for the screen. (Swimming Home and Hot Milk are in other scriptwriters’ hands.) She knows exactly, how the opening scene of August Blue will go, and she has the perfect idea of how to tackle the temporal complexities of The Man Who Saw Everything, which slips, through its main character’s fractured consciousness, between the Berlin of 1988 and the London of 2016. In The Cost of Living, Levy fantasises about living in California and writing scripts by her pool. When I teased her lightly about the unlikelihood of this, she said, “You never know. I just might be there in my swimming costume at 80, writing films. I’d have a river now – with a little rowing boat tied to the jetty, and I’d smoke, drink coffee and write my scripts, I think probably in France.”

In the meantime, now that her daughters are in their 20s, she comes from her London flat to work in her Paris studio for weeks at a time. She is taking French lessons, though presently her literary enthusiasms outstrip her linguistic ability. “I say, ‘Shall we translate this poem of Apollinaire together?’ and my teacher says, ‘I think today, Deborah, we will try to master être and avoir.’” Her most natural creative affinities are in fact French – Godard, Duras – rather than British. To her evident delight, Levy has won one of France’s most important literary awards, the Prix Femina Étranger. She has not yet won a major prize in Britain, despite multiple short listings, perhaps because British prizes tend to favour large, self-sufficient, discrete slabs of fiction.

She begins her days early, with a walk by the Seine. After work there might be an exhibition, or dinner – which she might depart, more than one friend told me, with sudden decision, announcing that she is back off to work. She looked abashed when I mentioned this habit, worried she might appear rude to her friends. “I’m immensely sociable and then I really need to be on my own. I do like to write after a dinner party,” she said. (She herself loves to cook – “delicious mountains of cream and garlic, and the kitchen is like a bomb site,” Charlotte Schepke said, “but it’s like being in the finest restaurant. Her presence makes it an occasion”.)

At the moment, in a sharp change of gear, she is researching a biography of the young Gertrude Stein, to be titled Mama of Dada. She is concentrating on the writer’s early training under psychologist William James, brother of the novelist Henry. Levy wants to think about how this academically brilliant American – who’d be late for her medical lectures because her bustled skirts were weighted down by horsehair-stuffed hems – moved to Paris, ditched the corset and became the pioneering modernist who dressed in monk-like robes and filled her house with Picassos.

It’s a characteristic way for Levy to build character. But while the books are rooted in the physical, they also make room for the uncanny and the unexplained, for the sudden intrusion into a person’s consciousness of unwelcome memories or dark imaginings. “It would be very sad to have all the possibilities of the novel, this hot-air balloon, but to say, ‘I only write social realism and the hot-air balloon must never leave the ground,’” she said. “That’s not how people’s minds work: people have very strange dreams, and thoughts, and daydreams, and associations.” She is, she said, very careful not to let her hot-air balloon float away into the clouds of fantasmagoria. It is all in the balance and control.

What also earths Levy’s work is her wit. “She is so amused, diverted and delighted by life,” said the actor Tilda Swinton, who is a fan. Her jokes, often wryly commenting on her own failings, make for a kind of intimacy, even complicity – “the kind of complicity that many of us can only relate to the dry land of childhood companionship”, said Swinton. Levy’s women, especially the “I” of the living autobiographies, fail as well as succeed; they have good days and bad. They are neither “feisty” and “gutsy” – those tiresome cliches – nor are they self-saboteurs, who put themselves down to ingratiate themselves with the reader. They are both real and offer an example of how to live well. When Levy was finding a way to write her living autobiographies, she searched for a voice that “was immensely powerful, immensely vulnerable; immensely eloquent and totally inarticulate. Because that’s all of us.”

In March, I went back to Paul Heber-Percy’s house to see her portrait finished. It renders Levy’s face in triplicate, as if seen through a kaleidoscope, and her hair, piled on her head, soars upwards like Medusa’s snaky locks, dissolving into abstract, Rorschach-like patterns and repetitions. It gave the impression of a presence with many selves, in constant movement of thought. In the portrait, Levy has five large, wide-open, scrutinising eyes; but one of her tripled faces disappears into the world outside the frame, and the sixth eye is unseen.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The history of the bridges in the parish is not easy to trace and the dates when they were first built are not known. Their existence only comes to light when they were officially recorded for some reason. Before the 14th Century, people and packhorses had to cross the Dart at Staverton at the ford – after which the village is named. The first bridge in the parish was Austin’s Bridge, just off the Buckfastleigh to Totnes Road. Originally 7’ 6’ wide it was widened in 1809. Dart Bridge (formerly known as Hood Bridge) was believed to have been built around 1356. Records indicate that Staverton Bridge was rebuilt in 1413 after the previous wooden structure was in danger of collapse.

The Church decided to finance the rebuilding of Staverton Bridge by issuing Indulgences, an apparently common means of raising finance for such projects in medieval times. People paid money to the church for Indulgences in the belief that they would spend less time in Purgatory, the equivalent of paying a fine instead of going to prison! The morality of raising funds in this way might be suspect, but at least we now benefit from the superstition of those who had done some wrong and hoped to buy their way out of Purgatory. As a result we now have the present fine stone bridge, which is a much-loved symbol of the Parish and which features on the Parish Council Chairman’s badge.

Some colourful events appear to have taken place on the bridge over the centauries. In 1436, an official enquiry resulted from a drunken brawl between a parish chaplain, Sir John Laa and one John Gayne. They were returning home from dining out and they started to argue on the bridge. The former drew a knife in self defence and the latter fell on it and was killed. Normally, a priest who had killed a man would have lost his living, but the Bishop’s enquiry absolved Sir John of any guilt and he continued in office.

Twenty years later, other incidents took place involving John Murry, the Bailiff of Haytor Hundred, who should have been maintaining the peace, but instead appears to have behaved suspiciously like a highwayman, relieving travellers of horses, harnesses and baggage as they crossed the bridge. It would have been an ideal place for waylaying and trapping victims.

Repairs and alterations have been carried out during the bridge’s long history but it remains the main route out of the village to Dartington and Totnes. Stand quietly on the bridge for a moment or two and you might just be lucky enough to catch the vivid blue flash of the kingfisher as it hunts for fish.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A few words

I have not written anything on Tumblr for a while.

Why is that?

My mood, my inclination or because I've nothing to say. Probably all or some of them; but I'm not done -- at least with my poetic and mythic sensibilities.

Right now, as I talked about in today's blog post, I'm almost at the end of my 5th job in five years. In bygone years, that would have meant anyone thinking of employing me, should stay well clear. There's trouble out in yonder movings and shakings.

But (of course) everything's explainable away; I can story-make with the best of them but let's just say there's only so much consternation one man can live under and with before you have to sever the Gordian Knot.

Where next for me?

Well, I'd love to do a Bukowski and go big or go home but I'm not his heir apparent -- not even close -- and I'll I can do is wend my way to another ending, along the tightrope of conformity that I've lived for far too long. If I don't do that then I'll have to go solo and see where the winds of time-tested theory take me.

Anyhow, it's good to have this platform available to me. It's out the way and means that my language doesn't have to border on the serene. That's code for saying I can be myself.

Take care.

Blessings, Julian

PS. This was today's walk around the Dartington Estate with the River Dart flowing mellifluously beside me.

1 note

·

View note

Note

I call JPJ's 1980 haircut "dad hair" because its what a lot of white dad's rocked 80-00's. Since you're Queen Jonesy, can you tell me how long he had that cut?

I know I can easily research this myself but I just love when you talk about him.

it is SUCH a sensible dad haircut like?? after all this time, he finally gave into having three daughters. but it honestly makes it perverse and iconic for him since the shortest he had had it was 1975 and that was still a scruffy moment with those sideburns (sidenote, I don't think we talk about his sideburns enough).

as far as how long he had it, i can only guess at. I think he probably held onto having short hair for the most part until the later 80s. The next photographic evidence of him is December, 1981.

lookin tiny as ever. Dave Lewis wrote in Tight But Loose "Jonesy looked like he’d just come from doing the school run (which he probably had!) in new Kicker shoes and smart tie," (x). Fucking cute.

This preceded his time teaching electronic composition at Dartington College of the Arts in 1982, for which I can't imagine he didn't have a sensible haircut.

And then we get to 1984, the 'Scream For Help' era which is EXTREMELY FLUFFY, but still short.

Live Aid, 1985, still saw the general fluffiness of our boy.

And then the next photographs we have, he's growing out his hair in 1987 I believe.

Which gets us to the Atlantic reunion in 1988…

Which gave birth to his last long hair-a up through 1995.

with a brief break in 1992.

Okay I know more than I thought 😂

Also, so honored you like to hear me talk about the little man. He is, for better or worse, a huge part of my life and I'm always happy to share my archival knowledge.

#thanks queen!!!!#queen kelly jeanne!!#john paul jones#led zeppelin#jonesy#classic rock#jimmy page#robert plant#john bonham

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Young Bond: Shoot to Kill by Steve Cole Review

For a challenge this year I decided to read a new Ian Fleming James Bond book, and a non-Fleming Bond book every month. Last month’s non-Fleming offering was Shoot to Kill which I thought I’d write a review of:

Despite growing up with the Young Bond series penned by Charlie Higson I had aged out of it by the time this book came around in 2014. I can’t recall when I found out that there was a second Young Bond series so this time I’m going without any knowledge and crucially without any sentimental attachment to them.

Anecdotally I’ve never seen any of the Cole books in the wild which doesn’t augur well, except at the mecca of books, the Foyles Bookshop at Charing Cross Road, which is where I picked up my paperback copy of Shoot to Kill.

I was both fascinated and trepidatious about Cole’s Young Bond series because on the one hand, I was really interested to see how he continued what Higson started and how he wrote James during his time at Fettes. I enjoyed his first Doctor Who novel, The Feast of the Drowned, but apart from that I’ve not been too enthused with his work, I get the impression he’s a very workmanlike author which is not necessarily a bad thing but he not only has to live up to Fleming but also Higson in my book.

On the whole, I think Cole does achieve the impossible, Shoot to Kill is a competently written continuation of Higson’s series with marvellous action in an inspired setting, Hollywood in the Golden Age of Film is such a great fit for James Bond. Doubly so for this prequel series which carries on the rumination on James’ future. In a meta sense, the silver screen is where James Bond eventually ends up.

Cole to his further credit confounded my expectations from the very first page, I had assumed that we’d get straight to Fettes but James has to spend a few weeks at Dartington Hall, an experimental new school in Totnes before he makes his way north of the border.

It’s an effective rug pull for the seasoned Bond readers and allows Cole to play in the gaps in James Bond’s timeline while also carving out something new and revealing something about the transitory nature of James’ life.

But knowing from the start that we’ll likely never see these characters again does hamper the ability to fully embrace them. They do grow on you, there is an endearing quality about them and I like that there is more of an ensemble feel to this adventure. Hugo Grande is easily the most likeable of the newly-introduced characters, and a better representation of a person with dwarfism than No Time to Die. However, I don’t think they are quite as distinctive as they could be.

It would’ve been hard for anyone to top the previous Bond girl Roan Power but Bouddica “Boody” Pryce does feel like a downgrade. Some attempt is made to flesh her out, with her engineering streak that gives Bond an iconic weapon but she fills the typically prickly girl that Bond has to deal with that fails to mark her out as something more.

Where Shoot to Kill falls down in the plotting. James along with his classmates happening to fall upon a snuff film is intriguing but unlike SilverFin where there is a gradual ramping up of stakes as the story goes on Shoot to Kill has a decently solid, if a little slow opening but then it completely sags in the middle only for it to do a full 180 and go full throttle in the final third. It’s only in that final third where the villain of the piece I felt truly became worthy of Fleming.

What Cole lacks is what Raymond Benson coined as ‘the Fleming sweep’ the little hooks at the end of a chapter that urge you to read the next and on and on. Something that Higson was similarly able to master.

It also relies a little too much on coincidence, there’s an awful lot of James happening to overhear things at just the right time. However, the one occasion where it does work is the one time he gets caught eavesdropping by a newspaper reporter of Asian heritage which is a nice subversion of Dr No.

To first get to America James has to board a Zeppelin. I love how the book takes advantage of a phenomenon that wouldn’t be possible if the story was set even only a couple of years later in the decade.

The Young Bond series has never been glamorous in the way that Fleming’s novels often are so it’s welcome that this series finally indulges in the splendour of the USA. And this is in a sense the first time James canonically has his first taste of luxury and the book captures the childlike naivety of the wonder of America that I certainly had at that age, that it was like Britain but bigger and more ostentatious.

And the glamour is effectively juxtaposed with the sleaze, something that I think Shoot to Kill does better than Diamonds Are Forever, which the former is clearly inspired by, the penultimate showdown having definite ‘Spectreville’ vibes.

It’s a similar story with the goriness which if anything is something more prominent in Higson’s stories than Fleming’s. Rather than shying away from it the goriness is still here with the villain getting a fittingly gruesome death but on more than one occasion the gore is simply described prosaically as “gory”, Cole’s writing again lacks the sharpness that Fleming and Higson employed.

It took me a little while to acclimatise to how Cole writes James as opposed to Higson, it’s only when James gets a charmingly cheeky, toying with his friend did I realise that Cole is writing him with Roger Moore in mind. Which makes a lot of sense, Higson very much a child of Connery and Cole being a couple of decades younger must’ve grown up with Moore.

There are some more cute references, James walking past a concert hall playing a ‘distinctive and jazzy’ number ‘with a mid-tempo beat, brasses and strings and needling steel guitars’ and an ominous swagger’ nod to the iconic Bond theme while still being quite subtle. Then there’s the obligatory Hoagy Carmichael reference that actually factors into the plot later on which I think works less well. Then come the final page we get something of a sequel hook concerning Andrew Bond and if this is going where this is going then I’m not looking forward, to put it mildly.

Overall, Shoot to Kill is a mostly competent debut for Cole’s series, filled with decent action but one that lacks the finesse of its predecessors that ultimately left me feeling a little lukewarm.

#007 fest#team00#james bond#ian fleming#young bond#shoot to kill#steve cole#charlie higson#book!bond#book review

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bunker’s work is characterised by an obsession with those twin disruptors born of Modernism, abstraction and collage, and their continuing powerful presence in contemporary art.

Abstraction is often associated with high ideals, formal innovation and a preoccupation with purely aesthetic experience. Collage is, by contrast, the stuff of gritty satire, stark juxtapositions of imagery and the quotidian world of objects and images.

Bunker plays with the friction generated between these two modes, creating images and objects that are both allusive and elusive. Swinging from the delicate and poetic to the materially dense and brutal, the array of sculptures, paintings and wall-based assemblages on show- all of them made within the last decade– offer tangible proof of Bunker’s ability to conjure captivating and psychologically charged abstract images from a startling and diverse range of materials.

Whilst working on a house in Edinburgh in 1887, two itinerant labourers placed a message inside a whisky bottle and hid it under the floorboards. Bottle and contents have only now come to light; and John Bunker’s survey show at Tension Fine Art, ‘Our Dust is Blowing Along the Road’ derives its title from one of the message’s most memorable fragments.

Bunker has this to say: “What struck me about this particular story was that the bottle was hidden in a house, rather than cast out to sea, and so long ago. I’d been thinking about putting together a survey show of my work for quite a while; and it occurred to me that, just like the bottle in this story, artworks get hidden away for years and then are rediscovered by the artist or curators. I liked the quiet poetry of those men’s words. They got me thinking: what messages from the past do artworks hold within the fabric of their peculiar singularity? How do they speak to us in the present tense and what might the future hold for them? Even an artwork I finished last week is already history!”

John Bunker was born in Norwich in the UK in 1968. He received BA Hons Degree in Art & Social Context from Dartington College of Arts, Devon in 1991. Since moving to London in 1996, Bunker has worked in various arts settings including community arts and Further and Higher Education. As well as maintaining his multi- disciplinary arts practise, Bunker also regularly curates exhibitions which have included artists as diverse as Sir Frank Bowling OBE RA and Harland Miller. He also writes regularly about art. Bunker has written numerous reviews, catalogue essays and articles and in 2018 co-founded instantloveland.com with Matt Dennis, a website dedicated to exploring the histories and potential futures of abstract art. Bunker has exhibited widely in the UK and abroad and has works in many private collections.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.dartington.org/event/the-spectre-at-the-feast-a-talk-with-mark-gatiss/

Join on line for free (or give a small donation), to hear Mark Gatiss share his own spooky tales and some of his favorites, while exploring the connection between festivity and terror.

👻🎃👹👻🎃👹👻🎃👹👻

#mark gatiss#the spectre at the feast#a talk with Mark Gatiss#the arts at Dartington#90 minutes with Mark#submission

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mark Gatiss - Press review of the day (02/10/2020)

‘Lockdown’: Ben Stiller, Lily James, Stephen Merchant, Dulé Hill, Jazmyn Simon & Mark Gatiss Set To Join Doug Liman’s Harrods Heist Movie Underway In London

Producers are in advanced talks with Ben Stiller, Lily James, Stephen Merchant, Dulé Hill, Jazmyn Simon and Mark Gatiss to join the cast.

Source: Deadline

Full article: Click here

______________________________________________________________

Summer Reads to Carry You into the Fall

“The Vesuvius Club”

Now, this book is purely in here for fun. I picked it up over the summer on Thriftbooks, along with other books for a book club I do with my friends, because I just wanted something fun to read.

I also saw it was by Mark Gatiss, the brilliant writer of “Sherlock” on the BBC, which made me like it even more. It turned out to be so much better than I ever could have expected! The book follows the character of Lucifer Box, an English spy in the early 1900s, described on the back cover as “equal parts James Bond and Sherlock Holmes, with a dash of Austin Powers.”

The book showcases the funny and fast-paced writing that made “Sherlock” so loved by viewers, but in a fun setting. This book was a little ridiculous, but it made me actually laugh out loud, while still having a good plot. Definitely a fun read for anyone looking to relax!

Source: The Fairfield Mirror

Full article: Click here

______________________________________________________________

The Spectre at the Feast: A Talk with Mark Gatiss

What makes a good ghost story? Find out on this thrilling evening with the man who describes himself on social media as ‘actor, writer, strangler’, Mark Gatiss.

The bond between Christmas and the spooky – perhaps most embodied by the Charles Dickens classic, A Christmas Carol – is the staple of many much-loved stories. In this talk, Mark will share his own and his favourite tales as he reads from ghost stories looking at the contrast between jollity and terror; the invitation of a spectre to the feast; the tracing of the anxiety within the festivity.

Mark has been writing ghoulish tales since his childhood, and is best known for his acting and writing credits on The Vesuvius Club, the BBC’s Sherlock and Dracula adaptations, and The League of Gentlemen.

Source: Dartington

Full article: Click Here

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Virtual Workshop Weekend for singers: Sing Joyfully 2021

Last year, in the wake of COVID-19 and the uncertainty that it created for singers getting together, I decided to make 2020 my year of delivering my regular workshop courses online. They were a resounding success.

I had the wonderful experience of attending another of Gillian Wormley's events this last weekend 10th to 12th October Sing Joyfully focussing on ensemble singing. This would normally be at lovely Dartington Hall in Devon, but COVID19 rather put a stop to that especially with 2 of our number living in Spain. However, Gillian brilliantly turned this into a virtual weekend but cleverly named the virtual meeting rooms names which were familiar from Dartington rooms and places especially meeting in the White Hart afterward although the real wine in my hand was rather nicer than the virtual one 😃

Steve Hope

Residential weekends at Dartington Hall, have in recent years formed part of my teaching year structure. Situated near Totnes in South Devon, the Dartington Hall ethos provided the perfect vibe for such valuable learning exchanges to happen. The workshop weekends typically ran in March (Love Your Voice) for solo singers, and October (Sing Joyfully) for ensemble singers.

Since March 2020, thanks to the pandemic, I’ve been on a learning curve of my own, reconfiguring my music studio, learning more about the tech requirements for teaching, and leading online. Little did I know how eerily on-point my post of January that year, where I welcomed applications for my ‘Love Your Voice’ course at Dartington Hall. This is how I opened the post:

“Teaching is more than imparting knowledge, it is inspiring change. Learning is more than absorbing facts, it is acquiring understanding.”

William Arthur Ward

and ...

Where the mentor provides a thought-provoking, boundary-busting structure to learning practices, so the student is encouraged to open themselves up to new ideas and patterns of work.

There is co-operative freedom to inspire. Magical when you experience it.

I like the idea of boundary-busting and inspiring change.

There is always a buzz of excitement in the months leading up to each of these events. It is very rewarding to watch returning singers, who in the normal turn of events, have allowed Dartington’s beautiful surroundings to feed their soul with each repeated experience, to hear their voices GROW in confidence and enjoyment in what they can do.

This year, right now, I anticipate that Sing Joyfully 2021 may offer singers two modes of participation; in person AND (for those who cannot travel easily) online. I rise to the challenge of taking on both initiatives to offer the whole music-making/ensemble-collaboration experience, in equal part.

My workshop weekends are immersive, by design. The best experiences are those borne out of an eagerness to learn. Good preparation is key - only then can each singer give wholeheartedly to the group as a whole.

The Dartington ethos, learning by doing, fits the bill completely. The magic will still weave its spell.

Come and join us; click the link and discover more. If you know you’d like to sing with us, here’s an application form link: Sing Joyfully 2021

You’ll find more info/details about planned SJ 2021 activities emerging on the event page in coming weeks and in early September I will share final timetable & ensemble details with participants sharing what to expect from the weekend as a whole.

Workshop weekend fees: £200 with a £75 deposit to pay on application, with deadline for action being Friday 20 August 2021, latest.

Thanks to my lovely friend and musician Paul Hornsby (fellow ex-dart too) for the first post image above. More examples of his excellent work can be found at www.hornsbyphotography.com or www.joatamon.photos.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

National Treasure

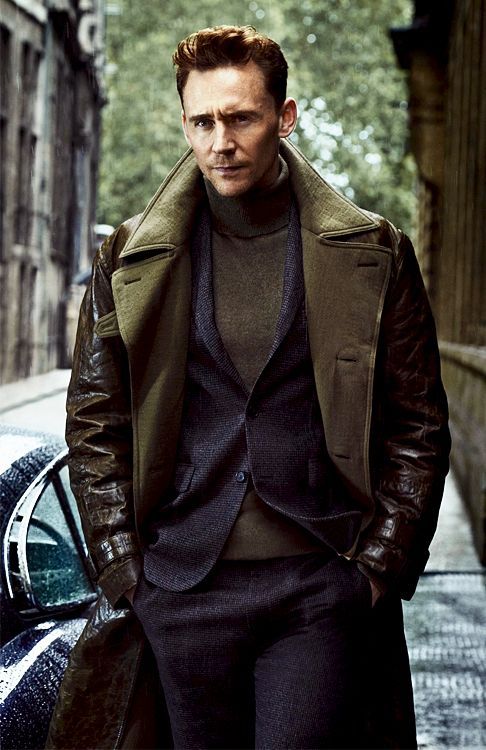

A ridiculous one shot I wrote after being dragged down the rabbit hole by my pals @hopelessromanticspoonie and @just-the-hiddles.

*****

“Okay, let’s take a break from this segment. Y/N, can you do a tea run?”

“Sure.” You took the moment to stretch, assessing that with all the crew members you’d need an extra pair of hands. “I’ll just do a recce.”

It was the final day of filming for a new series of adverts for the National Trust. They wanted to pitch their viewing at a newer, cooler audience, and they’d enlisted a whole load of famous British faces to speak on behalf of the places the NT looked after - “forever, for everyone.”

You were a fan. Especially of this place. You were currently filming at Stourhead, the home of the first ever Palldian villa to be built in the UK. The villa sat, the gem in an estate that included a tranquil lake complete with secluded grotto and statues, and a wishing fountain. When you arrived, some of the other runners had taken turns with you to toss coins into the fountain, making wishes.

You fished your notepad from the back pocket of your jeans and drew the pen from where you’d tucked it into your ponytail. Sexy it might not be, but having a pen there was beyond handy.

“Don’t forget Tom. He’s in the Grotto,” your colleague called as you started off.

The team were spread out. It was going to be a long recce and an even longer trip to get tea, you thought, but you didn’t mind. The day was sunny but a cool breeze ensured tempers hadn’t frayed, which could happen on a long day of filming.

So far the NT had filmed Benedict Cumberbatch at Trelissick Gardens, Luke Evans at Dyrham Park, Emma Thompson at Treasurer’s House, and Dame Judi Dench at Dartington Hall.

The NT had planned for Tom to film his segment in London, at Osterley Park, but filming clashes with the BBC had meant that Stourhead was closer for him.

He’d been friendly and warm when you’d met, and a little tingle of awareness had zinged up your arm when he’d shaken your hand, those summer sky blue eyes meeting yours and holding for a hot second.

You had shaken it off though, ever the consummate professional. Of course you felt a zing. You’d have to be dead not to.

The cool September breeze ruffled the ends of your ponytail as you picked your way down the steps to the Grotto. A gorgeous surprise to visitors who walked around the lake, the Grotto held two marble statues and the bubble of fresh, running stream water. In one of the pools, koi carp swam, delighting all who saw them, especially young children.

The Grotto was habitually slippery due to the springwater that sometimes bubbled over, and you were always careful. You wore work boots on site to protect yourself from any slips. Even so, your toe caught on one stony outcrop and for a second, you were flailing in mid air.

“Got you.”

You looked up into Tom’s stormy blue eyes. His arms encircled you, the springy curls on his head messy at the top, like he’d been running his hands through them. The corner of his mouth tipped up. You settled your hands on his shoulders, the material of the tweed jacket he wore soft under your palms. He’d really gone for the “country pile” look - tweed, a button down white shirt, jeans and Barbour boots.

“Thanks,” you breathed. “Bit slippery, here.”

He set you down safely. “Pleasure’s mine.”

You looked around, never tiring of the beauty of your home county, and proud that the National Trust worked to conserve green places like this. Secret places, where imagination and nature dreamed hand in hand.

“I love it here,” you said, without thinking, turning a circle to admire the statues and the stony walls, the shadows cast by trees and plants overhead.

“Hard to believe the world is out there, isn’t it? One touch of nature makes the whole world kin.”

“Shakespeare?”

He rubbed his cheek, looking embarrassed. “How did you know?”

“I, ah, came to see if you wanted some refreshment. Before we start again.”

His gaze held yours and you saw it. A flicker of naughty in his eyes. “What did you have in mind?”

Your mouth went dry as he moved closer to you, boxing you in against the slick wall of the Grotto. The stone was cool against your back, through your thin black shirt. He smelled fresh, citrussy with just a hint of bergamot and the tang of coffee.

“I’ve thought about this all day,” he murmured, his mouth lowering to yours.

Your heart lurched. “Seriously?”

Your voice came out a squeak, but he didn’t seem to notice.

“The way you bite your lip when you’re thinking. The way your hair sways with your hips when you walk.”

He hadn’t even touched you yet and you were melting inside.

Swallowing your gasp, his lips moved over yours. He was as fantastic a kisser as you’d imagined when you’d watched him kiss Kate in The Hollow Crown, later retiring to bed to indulge in a fantasy only your vibrator had been able to help you complete.

Your pulse raced as his tongue danced with yours, and of their own volition your arms slipped around his neck. You let your fingers tangle in the hair at the nape of his neck, and in response he yanked you closer. All coherent thought left your mind as you felt the length of him hard against your lower belly. Yes.

You groan his name as he nips at your lips. As you wriggle against him, trying to get closer still, Tom slides his hands under you and boosts you up against the uneven, stony wall. Its edges go unnoticed by you as you wrap your legs around his waist. His stubble scrapes your skin and it electrifies his kiss, every nerve ending coming alive in a burst of heat and fire.

“Y/N! Where are you?”

You both jump at the shout from your colleague. Tom meets your gaze and looks guilty, but happy.

“I’ve delayed you.”

“And look how hard I’m fighting to get free,” you tease.

He brushes another kiss over your mouth, tender from his attention. “I’m staying at the B&B down the road. Come see me, later?”

You nod and hop down from his arms to attend to the tea run.

Later, during filming, he sends you a wink as the make up artist finishes fussing with him. Your cheeks heat and you know that after you wrap, you’ll be doing a lot more than drinking tea together.

OK, it’s not a tweed jacket, but I’m limited to what’s on the internet.

Disclaimer: There are no koi carp at Stourhead. I just think they’re awesome.

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My Man Jean is a 30-page, single sided, black and white, mini size, picture storybook zine. Published by The Bubblegum Dada Corporation.

A little dark humor in this mini picture-book of love, jealously, and murder! Through a series of black and white vintage illustrations that look as if they were taken from Victorian books, a story unfolds as told by a young woman infatuated with her step-brother. The woman’s passion for her step-brother is not returned, instead his head is turned by another. Out of desperation the woman tells her tale of pursuit, crime, escape, and the assumption of a new identity…all because of love!

Tune in to a torrid tale of tempestuous fixation in the pages of My Man Jean at:

The Bubblegum Dada Corporation c/o 15 Dartington Walk Leigham Plymouth Devon PL6 8QA UK

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘Many sided’ Dartington Outing: first major queer arts festival at Dartington Hall

‘Many sided’ Dartington Outing: first major queer arts festival at Dartington Hall

We’re a little behind the curve on this one – that’s what happens after a month-long beach party here at PRSD towers (there’s still some sand behind our spacebars) – so this is a delayed heads up about ‘a Dartington Outing – seven days of queer arts and bent events’, talking place from 21-29 September 2017, to mark 50 years since the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in the UK1. Read on…

View On WordPress

#An Evening of Coward and Friends#Bayard Rustin#Beccy Strong#Bennett Singe#Daisy Asquith#Dartington#Dartington Hall#Dartington Outing#Impermanence Dance Theatre#Jonathan Cooper#Kevin Childs#Lisa Gornick#Proud2Be#Queerama#Stefan Bednarczyk#The Book of Gabrielle#Tom Marshman and Friends#What (the f**k) is lesbian cinema?

0 notes

Text

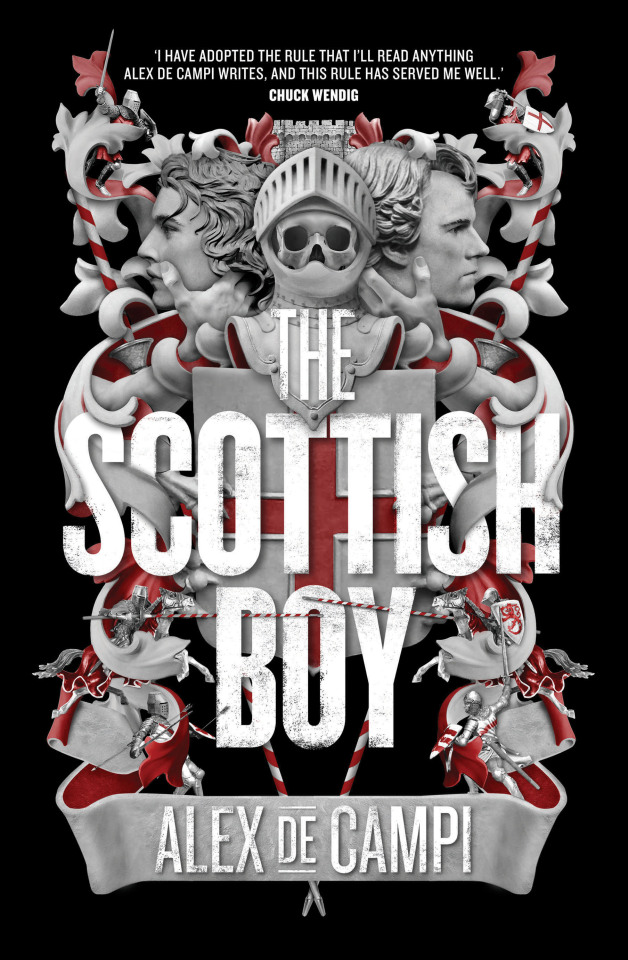

The Scottish Boy excerpt: The Black Knight

Hello all! Now that I've posted the lovely art of the Black Knight from @Trungles in the last Scottish Boy update, I thought I'd give you an excerpt (spoiler-free) from a later chapter where the Black Knight features. (I’ve also re-posted Trungles’ art under the cut!)

I think one of the benefits of coming back to prose writing after a lengthy sojourn in comics is it's made me quite good at blocking out action scenes and keeping them dramatic and suspenseful. Anyway, judge for yourself. Please consider pledging for the novel this is an excerpt from, you can read more right here. It’s only $35 for a 450+ page illustrated hardback, and $15 for eBook. And in a very real way, I can’t do this without you.

“I need to speak to His Majesty,” mutters Montagu, pacing. He points at the head. “Take this thing away and bury it. You, come with me,” he commands, his index finger rising to indicate the young knight who had spoken first. “You’ll give a full report in front of the King. Number of troops. Weapons. Likely nationalities. Tactics. If the King approves, we’ll raise a larger force and destroy this resistance and all who support them the same way we took care of it in Scotland.”

“I’d like to go,” says Harry, stepping forwards before he even realises it. “I’ve been on several raids across the border. I know some of the land.” Harry inhales, and plays his final card. “Sir Thomas Howland, too, he is the most experienced raider of us all.”

Montagu smiles at him, his hooded eyes as dead as a December garden. “Good old Sir Harry. We can always count on you.”

The King prevaricates. Sending enough men to end the border resistance once and for all would mean sending an Earl, and if they send an Earl, they might as well just invade France. The King doesn't want to invade until Germany and the Low Countries get off the fence. Plus, their army at Antwerp is not large. A hundred and twenty knights, plus about a thousand men-at-arms.

Then France sends its fleet against English port towns. Portsmouth is hit; Southampton, burned. The Channel Islands are seized. The news reaches Antwerp at the same time as a letter from Oliver Ingham, the English seneschal in Gascony, begging for help against a French invasion.

Edward sends messengers to England to begin raising real army. And he sends an Earl over the border.

Montagu takes a quarter of their men-at-arms and twenty knights, including Harry and Sir Thomas. They follow the Scheldt river southwest to Ghent and then towards Tournai, just across the line into France. Once they reach Tournai, they will turn north and travel along that border, killing and burning their way towards Calais. It’s a cumbersome force, ill-suited to fast raiding in enemy territory. Instead, Montagu plans to intimidate the locals into giving up the mercenaries: each village will be asked for information, and if they don’t respond, the village and everyone in it will be destroyed.

The monotonous, flat fields of Flanders are finally relieved by low hills as they approach the border. Sparse stands of trees thicken into forest and Harry is relieved for the shade, even if he misses the stark, endless visibility of the farmlands. The docile barns and quiet farmsteads of the plains are not all friendly to the English cause. Any one could harbor enemy combatants ready to slip out under the cover of night and devastate an English camp. The landscape reminds Harry heartbreakingly of Dartington, and he spends a day in turmoil, imagining men like them riding through Devon, burning and killing.

They cross the Scheldt at a little stone bridge late on their third afternoon, and then the small army makes camp at the edge of the elm forest just on the Flemish side of the border. Tomorrow, they ride into France. Tonight, their last night on Flemish soil, they eat cold rations of cheese and hard bread and sausage, and turn in without fires. Harry sleeps in his mail. He learned that lesson in Scotland.

Their first mistake is assuming they were safe in Flanders.

Their second is assuming the mercenaries would fight like Englishmen.

The raiders slay the sentries with knife and bolt in the deepest pits of the night, when the moon has already begun her decline. Harry jolts awake to the sounds of screaming and the creak and twang of crossbows. He slams on his helmet, grabs his shield and sword, and unlaces his tent flap. His first instinct is to head for Montagu, because he has a feeling that is where the Black Knight, this Chevalier de la Mort, will be. But as he looks cautiously outside his tent, his military instincts take over. First, he has to secure the horses.

The camp is pandemonium. Montagu brought with him a score of longbowmen but their ranged weapons are useless in a packed, close-range night fight in a forest. Harry keeps his shield up and his head down and yells “<To the horses! To the horses!>” as he runs through the camp towards the horse lines. He deliberately chooses to speak in English, hoping none of the raiders understand their language.

He ducks under a crossbow bolt and whirls, his sword coming up low and under the bowman’s short hauberk. Harry feels the wet suck of the sword hitting the man’s thigh bone and yanks hard, pulling it out. He runs on. There’s no point making sure the man is dead. If he can’t stand, he’s as good as gone, and with luck one of his friends will stop to help him. Then Harry will have stopped two raiders rather than just one.

A few men-at-arms from their camp stagger towards him, clutching weapons and shields, most still in their nightshirts. By the time they get to the horse lines there are a couple dozen of them, knights and spearmen and a few longbowmen, massed together. It’s enough to make them a hard target in a camp full of easy ones, and but for a few opportunistic shots from passing raiders with crossbows they’re left alone.

Harry doesn’t hear the sound of hooves anywhere but from their own horses, fearful and restless in their lines. Inside, he’s panicking, because he knows the raiders' mounted force is out there somewhere. But where? It makes his skin crawl, knowing that the main part of the attack hasn’t even happened yet, that any moment now will come the thunder of heavy armor riding them all down. The forest will slow them, but it’s an old forest, with tall trees and little undergrowth. Nothing to stop a mounted knight.

Harry throws a bridle on on Nomad then jumps up on him, bareback, and once again yells “<To me! Rally to the horse lines!>” He orders the younger knights, all with fresh memories of squiring, to grab all the remaining destriers and take the men-at-arms and head as a body back over the Scheidt bridge, deeper into Flanders. All Harry can do is send a quick prayer heavenward that he’s not sending them to their death. It’s strange that the raiders hadn’t already freed the horses, or stolen them… unless they want the English to run.

Unless the bridge is a trap.

“<Ride back along the river!>” Harry calls, his guts twisting in panic as he remembers the little copse of trees on the Antwerp side of the bridge. At what perfect cover it would be to turn the crossing into a killing ground. “<Don’t take the first bridge you come to. Take the second.”>

The men nod their understanding.

Harry calls to some of the men-at-arms he’s worked with before: Carl and Pete and Kev and old Lars. He has just enough time to point out the horses of the Earl and his household knights before the raiders – who hadn’t been avoiding them, they’d been organizing – are on them. It’s a dozen enemy against the six of them, but Harry is on horseback and Kev has his bow. Kev can shoot six arrows for every one from the more cumbersome Genoese crossbows, and they soon even the odds. Carl's hit, they can’t tell how badly, but Pete and Lars get him over a horse and they’ll worry about it later, when they have the luxury of time.

They push through the camp towards Montagu’s tent. Harry can see the knights of quality bunched in front of it, surrounded by enemy raiders.

Montagu is furious, screaming at the raiders from behind the cordon of knights defending him. “French scum! Brigands! Your leader calls himself a knight, then why won’t he come out and fight like one?”

There’s a soft, harsh sound then, somehow audible over the clash of steel and the thud of arrows into shields. It’s a crackling, gasping wheeze, and Harry realizes after a moment that it’s laughter.

A chill runs down his spine as he looks to its source. There, deep in the shadows of the trees, is a pool of even greater darkness: a knight, huge and broad in black plate, his shield plain but for a bend sinister, on a large black warhorse. And he’s laughing at them.

Harry can hear the muted chink of the horse’s tack as the knight shakes his head in amusement and turns his steed, disappearing into the forest. And that’s somehow the most terrifying thing of all: that the Black Knight didn’t feel like he had to engage. That they weren't worth his time.

38 notes

·

View notes

Audio

This track, (mainly for any aliens out there who ?... maybe secretly visiting earth), is from my self released Bandcamp album Corner People. It will be the first track on my new album, which is called Rope Theory. This recording will be available as a digi DL in loads of different outlets next Thursday the 16th of May, and is a compilation of a bunch of my tunes.

If anyone is interested, I got the name Liudprand, and there are various spellings, from my liking of Late Roman/Byzantine history. He was a diplomat and Bishop of Cremona (c. 920-972). I liked the way he wrote.

Listen/purchase: Corner People by liudprand

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buy Dartington flower vases online made by Hilary Green it features an indented base that can be used to help retain or splay out stems when using with flowers.

0 notes

Text

Teaching: freedom to inspire

“Teaching is more than imparting knowledge, it is inspiring change. Learning is more than absorbing facts, it is acquiring understanding.”

William Arthur Ward

When it arrives, this kind of synergy brings an exciting dynamic to the relationship between student and mentor. If present, the two elements generously combine to create an unwritten contract of possibility.

Where the mentor provides a thought-provoking, boundary-busting structure to learning practices, so the student is encouraged to open themselves up to new ideas and patterns of work.

There is co-operative freedom to inspire. Magical when you experience it.

Dartington Hall, near Totnes in South Devon, provides the perfect vibe for such exchanges to happen and with my next residential weekend in March just visible on the horizon, those of us who have already signed up to be there are beginning to feel the buzz of excitement.

For solo singers, the Love Your Voice weekend workshop promises...

Three working workshop sessions and a final performance afternoon to nurture and gently challenge the solo singer. We’ll be looking at everything from vocal technique issues and exercise with warm-ups, to repertoire offerings and the intricacies and experience of performance. Each singer will be offered generous opportunity to sing to other members of this very supportive and intimate workshop group.

The Dartington ethos, learning by doing, fits the bill completely. The magic still weaves its spell.

My workshop weekends are immersive, by design.

The best experiences are those borne out of an eagerness to learn.

Good preparation is key - only then can each singer give wholeheartedly to the group as a whole.

t is both humbling and rewarding to watch returning singers, who allow Dartington’s beautiful surroundings to feed their soul with each repeated experience, to hear their voices GROW in confidence and enjoyment in what they can do.

“Love Your Voice 2019 was a wonderful voyage of discovery for me where the excellent coaching and mentoring of Gillian Wormley really helped me to find the way forward with my singing after suffering significant vocal problems. But with that came the close friendships that were generated among like minded people all working towards their vocal goals and ideals all supporting each other in a great atmosphere at the wonderful Dartington Hall where the historic spirit of creativity still pervades every nook and cranny. Excellent Teacher Lovely Music Great Friends all came together to make a Wonderful Weekend. I look forward to the next.”

At the time of writing this, there are TWO places left on the course. The application deadline is 31 January 2020.

The mini-retreat weekend provides an excellent opportunity for a small group of singers to meet for an inspiring residential weekend within a mutually supportive intimate setting and environment dedicated to the art and JOY of solo-singing.

“I had the privilege to take part in Spring 2019 Love Your Voice ... I have attended similar workshops, run by Gillian in the wonderful surrounds of Dartington Hall, Devon, but this one was particularly special for me. I am at a critical stage in my vocal development. I am just finding my true voice and I am nearly ready to add solo singing to my current choral singing activities. During this weekend I had ample time to sing solo pieces with excellent, tutoring and mentoring from Gillian and the wonderful support of my fellow singers. Also, during the weekend there was plenty of time to relax, eat and talk about singing and repertoire. This led to a wonderful holistic weekend of music. Particularly beneficial for me, was the opportunity to perfect my singing of a duet, that I am singing in an upcoming concert. On my return from the workshop, I was auditioned for a solo, singing a piece I had worked on in LYV. I was given the solo, and that is all thanks to the weekend! LYV gave me a great deal of confidence to sing different repertoires in different physical environments and to take some risks! I would recommend the weekend to singers of all abilities, you will have total musical experience in a safe, but the challenging vocal environment.”

So, if you are someone who enjoys a high standard of solo singing, good company, excellent mentoring, beautiful rural surroundings, fine food and diverting conversation, you are tailor-made for this experience.

Come and join us.

Here’s a link to the dedicated event page, where you’ll find more info/details about the wondrous venue and what to expect from the weekend timetable.

Please note, the deadline for applications is 31 January, latest.

Thanks to my lovely friend and musician Paul Hornsby (fellow ex-dart too) for the images above. More examples of his excellent work can be found at www.hornsbyphotography.com or www.joatamon.photos.

2 notes

·

View notes