#Daoist magic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Is there any sort of symbolism for Sun Wukong's shootling lazers out of his eyes after bowing to the four cardinal directions? Also is there any other mention of his lazer eyes or is just this one time in the beggining of the novel?

The laser beams only appear in the beginning of the novel.

I've previously suggested in this article that they are one of several events from the historical Buddha's biography that the author-compiler of Journey to the West borrowed in order to make Sun Wukong's early life more familiar. The pertinent section reads:

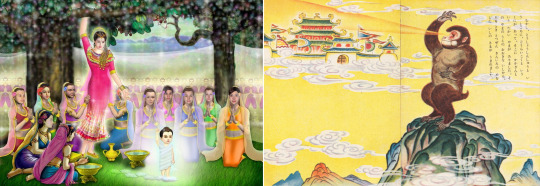

Upon his birth, the Buddha is said to have “shed in every direction the rays of his glory” (fig. 3) (Beal, 1883, p. 3). The source continues to describe this light, as well as the Bodhisattva’s first few moments outside the womb:

His body, nevertheless, was effulgent with light, and like the sun which eclipses the shining of the lamp, so the true gold-like beauty of the Bodhisattva shone forth and was diffused everywhere. / Upright and firm and unconfused in mind, he deliberately took seven steps, the soles of his feet resting evenly upon the ground as he went, his footmarks remained bright as seven stars. / Moving like the lion, king of beasts, and looking earnestly towards the four quarters, penetrating to the centre the principles of truth, he spake thus…” (Beal, 1883, pp. 4-5).

The historical Xuanzang (on whom Tripitaka is based) notes in his travelogue that the Buddha even walks towards the cardinal directions: “After he had been born the Bodhisattva walked seven steps unaided to each of the four quarters … [u]nder each step a large lotus flower sprang up from the earth” (Xuanzang, 1996/2016, p. 158).

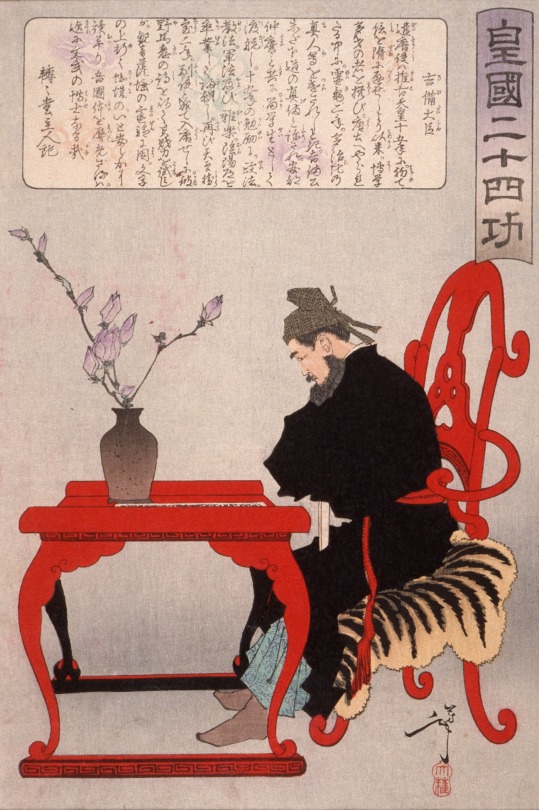

Wukong too produces a great light in every direction: “Having learned at once to climb and run, this monkey also bowed to the four quarters, while two beams of golden light flashed from his eyes to reach even the Palace of the Polestar” (fig. 4) (Wu & Yu, 2012, p. 101).

Therefore, both shine their lights in the four cardinal directions.

Fig. 3 – Baby Buddha producing a radiant splendor upon his birth (larger version). Artist unknown. Found on this article. Fig. 4 – Bright beams of light shine from Wukong’s eyes as he bows to the four directions (larger version). From the Japanese children’s book Son Goku (1939).

Sources:

Beal, S. (Trans.). (1883). The Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king: A Life of Buddha by Asvaghosha Bodhisattva. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/foshohingtsankin00asva/mode/2up

Xuanzang (2016). The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions (2nd ed., R. Li, trans.). California: BDK America, Inc. (Original work published 1996)

Wu, C., & Yu, A. C. (2012). The Journey to the West (Vols. 1-4) (Rev. ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Journey to the West#JTTW#laser beams#lasers#eye lasers#Buddha#historical Buddha#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK#Magic#Buddhist magic#Daoist magic#Asks

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wan'an Palace (萬安宮), a cozy and old rural temple in Dehua village (德化仙境村), Fujian, dedicated to Thunder deities. Natural detail of the fairy landscape.

Photo: ©鸿慈永祜

#ancient china#chinese culture#taoism#chinese mythology#chinese architecture#chinese art#taoist magic#taoist practices#wooden architecture#wooden buildings#chinese customs#taoist#chinese folk religion#chinese temple#religious art#temple architecture#Taoist temple#daoism#daoist#rural#countryside#Thunder deities#thunder rites#Leifa

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

We Are Time

What is time? We use time and observe time by our ability of measuring changes. To us, time is the measurement of changes. The sunrise to sunset, the full moon to the new moon, the seasons, the changing of our physical appearances as a new born baby to an old person in the grave, the time between each heartbeat, and so on.

Those are just our measurements of the observations we notice of changes. We do not realize that our brain time stamps each incoming sensory signal so that they can be accurately matched to the same event: seeing, touching, hearing, and hitting a ball all have sensory signals traveling at different speeds reaching the brain at different times. Otherwise, we would be in a constant state of confusion.

We also do not realize that our vision of receiving photons, all come at different time intervals from the same source. This then creates the perception of length, width, and height. When we see a building, or a tree, or a stick, we think we are seeing all at once the entire building, tree, or stick. In fact, thousands of photons from each different point and location of the building, tree, or stick, from the bottom, from the middle, from the top, are reaching our brain at different time intervals. Our brain just combines the bottom, middle, and top sections together as one moment. We then see the building as one thing at one moment, and not thousands of moments and of sections with each section and each moment having a photon reaching our brain at slightly different time intervals. So when we see width, length, and height, we are seeing time! But, that still is not the substance of time. It is still a measurement of our ability of observation!

We are time. The substance of time is us! Time is not out there. Time is us! What does this mean? Can I break this down to more elemental insights and understandings? What is the substance of time! What has been given to me for me to be time? How am I time? What makes me and you to be time itself! Time is me, and me is time! How can this be?

#consciousness#atheist#mind#meditation#buddhism#spiritual#buddha#atheism#buddhist#hinduism#time#perception#simulation#gnostic#mysticism#mystical#magic#reality#enlightenment#heaven#truths#daoist#dao#taoist#taoism#qabalah#kabbalah

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Zhang Lu was a native of Pei. He was a grandson of Zhang Ling who retired to Mount Humming, in the East River Land, where he had composed a work on Daoism for the purpose of deluding the multitude. Yet all the people respected Zhang Liang, and when he died his son, Zhang Heng, carried on his work, and taught the same doctrines. Disciples had to pay a fee in rice, five carts. The people of his day called him the Rice Thief.

Luo Guanzhong, Romance of the Three Kingdoms (trans. C.H. Brewitt-Taylor)

#quote#quotation#Luo Guangzhong#Romance of the Three Kingdoms#Zhang Lu#Zhang Ling#Daoism#I love every magic Daoist#the Rice Thief

1 note

·

View note

Text

dark kegel tricks. show me the forbidden daoist sex magic.

990 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know, I know. LMK is kinda its own fantasy setting at this point, not everything has to be mythos-accurate, yadda yadda yadda.

However, I won't be me if I don't take the chance to ramble and nitpick anyways.

Basically: What do I mean when I say "Chaos doesn't work that way in traditional Chinese cosmology", in regards to LMK S5?

When people think of Chaos in the pop culture sense, it tends to be this destructive, corrosive force of entrophy, or a maelstrom of changes and aimless activities.

Even when the Chaos/Order divide doesn't get simplified into Evil/Good, Chaos is still painted as the antithesis of Order, and the two forces are often engaged in an antagonistic, dualistic conflict.

The way the primodial chaos is described in LMK very much fits that mold. It is something Nvwa has to create the Pillar of Heaven to protect humanity from, its magic is dark and ominous-looking, and the villain of the season is obsessed with it.

Yet Chaos——Hundun, when it isn't this cute little guy in the Book of Mountains and Seas:

or the victim of two gods' failed cosmetics surgery in Zhuangzi, is simply the undifferentiated, pre-creation state of the world, before it separates into Yin and Yang and the Five Phases.

In fact, Chaos in early Daoism and later, internal alchemy is something one desires to return to, because with the division of Chaos into Yin and Yang and the subsequent formation of the world also comes life and death, suffering and disorder.

For early Daoists, they yearned to return to that primitive, undivided state, which was viewed as a golden age, on an individual and societal level. For practitioners of internal alchemy, it was a lot more personal: by returning oneself to that primodial, Pre-Heaven stage through the blending of one's Spiritual Mind and Vital Force, one can attain immortality.

In fact, the word for the sort of disorder and mayhem people imagine when they heard "Chaos" is not Hundun, but Luan in early Chinese sources.

Both early Daoists and Confucians used the word Luan in their writings, but had significantly different take on what caused it.

To early Daoists, Luan was the result of people imposing their arbitary moral standards and civilization onto the natural, undifferentiated state of the world, a.k.a. what the Confucians and their idealized sage kings had done.

By introducing order, they caused division in the undivided, and from such divisions comes disorder. After all, if you had to educate people on right and wrong and exhort them to do good, then the world you were living in was already an immoral one.

(That's what the fable of the failed cosmetics surgery in Zhuangzi means...probably. Where two sea gods try to artificially create the seven orifices for the faceless Central Lord Chaos to repay his favor, and end up killing him in the process.)

The early Confucians also shared the same yearning to return to the golden age of the ancients, but their idea of the golden age wasn't the sea of undifferentiated, primodial unity.

Instead, it's the reign of the virtuous sage kings. Luan was the result of a breakdown of the order they established, as people lost respect for propriety and hierarchy of relations and began to behave immorally.

Their most explicit mention of Hundun was in Zuo Zhuan, where it was one of the Four Perils, all of which were immoral offsprings of ancient kings who were exiled by Sage King Shun. It very much fits into the narrative of "triumph of the righteous ruler over rebellious vassals", civilization over disorder.

However, the Confucian Hundun was no actual, primodial force of chaos, merely a historicized personification of disorderly, wrongful *human* conducts. In return, order isn't the cosmological, capital "O" Order either, but a moral and societal one.

Anyways, that's why the Order/Chaos conflict doesn't map neatly onto ancient Chinese cosmology: to have an Order/Chaos conflict implies there is a division, when Hundun is actually the lack of any sort of division.

Neither is Hundun a cosmological force of destructive changes and entrophy. If anything, it's more like the state of nature, from which everything spawns and will ultimately return to.

A cosmic egg, a sea of warm primodial soup, instead of a maelstrom of destruction or a corrupting poison.

(TL;DR: reject Moorcock, embrace Zhuangzi. /lh)

#chinese mythology#chinese religions#chinese philosophy#hundun#lego monkie kid#lego monkie kid season 5#lmk season 5#lmk s5 spoilers#lmk s5#monkie kid spoilers#harbinger of chaos

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Wheel of Time 🤝 my favorite xianxia danmei

1. Dope costumes

2. Magic system based loosely on daoist philosophy

3. A protagonist being driven slowly to madness and horrific acts of violence by the immense power they wield and also all the trauma

4. Gay people

#luo binghe#Wei wuxian#Xie lian#svss#mdzs#tgcf#rand al’thor#wheel of time#wot on prine#wot show#caitie speaks

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

"As an indigenous Chinese literary genre highlighting magical arts and imaginary worlds, xiuxian/xiuzhen ('Immortality Cultivation' novel) is grounded in Chinese culture and religion, especially Daoist alchemy. Xiuxian/xiuzhen literature in postsocialist China is postsecular, in that it captures the influence of the religious revival since the 1980s on popular culture and challenges the state’s secularisation projects in the 20th century. The postsecularity of ‘superstitious’ fantasies alters the utopian dreams of socialism and deviates from the anti-religious and anti-superstitious ideology in this modern secular country.

Correlated with traditional novels and influenced by mass-market Western novels, ‘immortality cultivation’ fantasies do not simply generate reality-escaping and wish-fulfilling reverie. More significantly, they serve as a platform for Chinese readers to orient themselves in a postsocialist, neoliberal capitalist context, by means of enabling them to reconsider the contemporary Western triad of religion, science and superstition. Xiuxian/xiuzhen fantasies are enriched by magical transhumanism beyond boundaries of ‘legitimate’ religion and science, thereby inventing a posthuman subject and a utopian world; Daoist alchemy, in particular, bears resemblance to transhumanist technology in terms of theories and visions."

-"Cliché-ridden Online Danmei Fiction? A Case Study of Tianguan ci fu," Aiqing Wang

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zhuge Guo (諸葛果), Zhuge Liang's daughter. Her father named her guo (果; "fulfil / realise", basic meaning "fruit / result") because he wanted her to learn Daoist magical arts and fulfil her destiny of becoming an immortal [x]

#I've been wanting to draw them for months#and i finally did :)#zhuge guo#zhuge liang#romance of the three kingdoms#rot3k#san guo#三国演义

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shikigami and onmyōdō through history: truth, fiction and everything in between

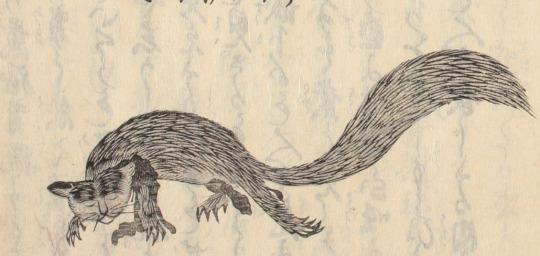

Abe no Seimei exorcising disease spirits (疫病神, yakubyōgami), as depicted in the Fudō Riyaku Engi Emaki. Two creatures who might be shikigami are visible in the bottom right corner (wikimedia commons; identification following Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage, pp. 57-58)

In popular culture, shikigami are basically synonymous with onmyōdō. Was this always the case, though? And what is a shikigami, anyway? These questions are surprisingly difficult to answer. I’ve been meaning to attempt to do so for a longer while, but other projects kept getting in the way. Under the cut, you will finally be able to learn all about this matter.

This isn’t just a shikigami article, though. Since historical context is a must, I also provide a brief history of onmyōdō and some of its luminaries. You will also learn if there were female onmyōji, when stars and time periods turn into deities, what onmyōdō has to do with a tale in which Zhong Kui became a king of a certain city in India - and more!

The early days of onmyōdō In order to at least attempt to explain what the term shikigami might have originally entailed, I first need to briefly summarize the history of onmyōdō (陰陽道). This term can be translated as “way of yin and yang”, and at the core it was a Japanese adaptation of the concepts of, well, yin and yang, as well as the five elements. They reached Japan through Daoist and Buddhist sources. Daoism itself never really became a distinct religion in Japan, but onmyōdō is arguably among the most widespread adaptations of its principles in Japanese context.

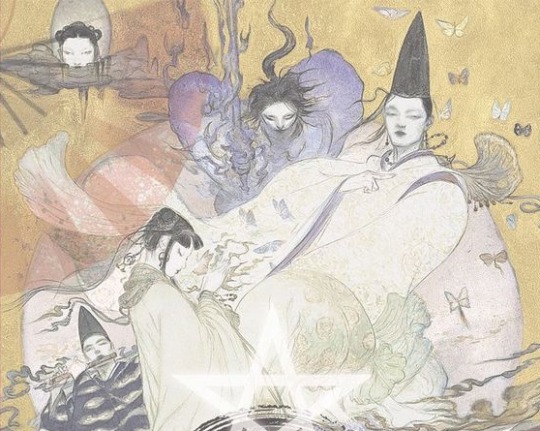

Kibi no Makibi, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (wikimedia commons)

It’s not possible to speak of a singular founder of onmyōdō comparable to the patriarchs of Buddhist schools. Bernard Faure notes that in legends the role is sometimes assigned to Kibi no Makibi, an eighth century official who spent around 20 years in China. While he did bring many astronomical treatises with him when he returned, this is ultimately just a legend which developed long after he passed away.

In reality onmyōdō developed gradually starting with the sixth century, when Chinese methods of divination and treatises dealing with these topics first reached Japan. Early on Buddhist monks from the Korean kingdom of Baekje were the main sources of this knowledge. We know for example that the Soga clan employed such a specialist, a certain Gwalleuk (観勒; alternatively known under the Japanese reading of his name, Kanroku).

Obviously, divination was viewed as a very serious affair, so the imperial court aimed to regulate the continental techniques in some way. This was accomplished by emperor Tenmu with the formation of the onmyōryō (陰陽寮), “bureau of yin and yang” as a part of the ritsuryō system of governance. Much like in China, the need to control divination was driven by the fears that otherwise it would be used to legitimize courtly intrigues against the emperor, rebellions and other disturbances. Officials taught and employed by onmyōryō were referred to as onmyōji (陰陽師). This term can be literally translated as “yin-yang master”. In the Nara period, they were understood essentially as a class of public servants. Their position didn’t substantially differ from that of other specialists from the onmyōryō: calendar makers, officials responsible for proper measurement of time and astrologers. The topics they dealt with evidently weren’t well known among commoners, and they were simply typical members of the literate administrative elite of their times.

Onmyōdō in the Heian period: magic, charisma and nobility

The role of onmyōji changed in the Heian period. They retained the position of official bureaucratic diviners in employ of the court, but they also acquired new duties. The distinction between them and other onmyōryō officials became blurred. Additionally their activity extended to what was collectively referred to as jujutsu (呪術), something like “magic” though this does not fully reflect the nuances of this term. They presided over rainmaking rituals, purification ceremonies, so-called “earth quelling”, and establishing complex networks of temporal and directional taboos.

A Muromachi period depiction of Abe no Seimei (wikimedia commons)

The most famous historical onmyōji like Kamo no Yasunori and his student Abe no Seimei were active at a time when this version of onmyōdō was a fully formed - though obviously still evolving - set of practices and beliefs. In a way they represented a new approach, though - one in which personal charisma seemed to matter just as much, if not more, than official position. This change was recognized as a breakthrough by at least some of their contemporaries. For example, according to the diary of Minamoto no Tsuneyori, the Sakeiki (左經記), “in Japan, the foundations of onmyōdō were laid by Yasunori”.

The changes in part reflected the fact that onmyōji started to be privately contracted for various reasons by aristocrats, in addition to serving the state. Shin’ichi Shigeta notes that it essentially turned them from civil servants into tradespeople. However, he stresses they cannot be considered clergymen: their position was more comparable to that of physicians, and there is no indication they viewed their activities as a distinct religion. Indeed, we know of multiple Heian onmyōji, like Koremune no Fumitaka or Kamo no Ieyoshi, who by their own admission were devout Buddhists who just happened to work as professional diviners.

Shin’ichi Shigeta notes is evidence that in addition to the official, state-sanctioned onmyōji, “unlicensed” onmyōji who acted and dressed like Buddhist clergy, hōshi onmyōji (法師陰陽師) existed. The best known example is Ashiya Dōman, a mainstay of Seimei legends, but others are mentioned in diaries, including the famous Pillow Book. It seems nobles particularly commonly employed them to curse rivals. This was a sphere official onmyōji abstained from due to legal regulations. Curses were effectively considered crimes, and government officials only performed apotropaic rituals meant to protect from them. The Heian period version of onmyōdō captivated the imagination of writers and artists, and its slightly exaggerated version present in classic literature like Konjaku Monogatari is essentially what modern portrayals in fiction tend to go back to.

Medieval onmyōdō: from abstract concepts to deities

Gozu Tennō (wikimedia commons)

Further important developments occurred between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. This period was the beginning of the Japanese “middle ages” which lasted all the way up to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. The focus in onmyōdō in part shifted towards new, or at least reinvented, deities, such as calendarical spirits like Daishōgun (大将軍) and Ten’ichijin (天一神), personifications of astral bodies and concepts already crucial in earlier ceremonies. There was also an increased interest in Chinese cosmological figures like Pangu, reimagined in Japan as “king Banko”. However, the most famous example is arguably Gozu Tennō, who you might remember from my Susanoo article.

The changes in medieval onmyōdō can be described as a process of convergence with esoteric Buddhism. The points of connection were rituals focused on astral and underworld deities, such as Taizan Fukun or Shimei (Chinese Siming). Parallels can be drawn between this phenomenon and the intersection between esoteric Buddhism and some Daoist schools in Tang China. Early signs of the development of a direct connection between onmyōdō and Buddhism can already be found in sources from the Heian period, for example Kamo no Yasunori remarked that he and other onmyōji depend on the same sources to gain proper understanding of ceremonies focused on the Big Dipper as Shingon monks do.

Much of the information pertaining to the medieval form of onmyōdō is preserved in Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), a text which is part divination manual and part a collection of myths. According to tradition it was compiled by Abe no Seimei, though researchers generally date it to the fourteenth century. For what it’s worth, it does seem likely its author was a descendant of Seimei, though. Outside of specialized scholarship Hoki Naiden is fairly obscure today, but it’s worth noting that it was a major part of the popular perception of onmyōdō in the Edo period. A novel whose influence is still visible in the modern image of Seimei, Abe no Seimei Monogatari (安部晴明物語), essentially revolves around it, for instance.

Onmyōdō in the Edo period: occupational licensing

Novels aside, the first post-medieval major turning point for the history of onmyōdō was the recognition of the Tsuchimikado family as its official overseers in 1683. They were by no means new to the scene - onmyōji from this family already served the Ashikaga shoguns over 250 years earlier. On top of that, they were descendants of the earlier Abe family, the onmyōji par excellence. The change was not quite the Tsuchimikado’s rise, but rather the fact the government entrusted them with essentially regulating occupational licensing for all onmyōji, even those who in earlier periods existed outside of official administration.

As a result of the new policies, various freelance practitioners could, at least in theory, obtain a permit to perform the duties of an onmyōji. However, as the influence of the Tsuchimikado expanded, they also sought to oblige various specialists who would not be considered onmyōji otherwise to purchase licenses from them. Their aim was to essentially bring all forms of divination under their control. This extended to clergy like Buddhist monks, shugenja and shrine priests on one hand, and to various performers like members of kagura troupes on the other.

Makoto Hayashi points out that while throughout history onmyōji has conventionally been considered a male occupation, it was possible for women to obtain licenses from the Tsuchimikado. Furthermore, there was no distinct term for female onmyōji, in contrast with how female counterparts of Buddhist monks, shrine priests and shugenja were referred to with different terms and had distinct roles defined by their gender. As far as I know there’s no earlier evidence for female onmyōji, though, so it’s safe to say their emergence had a lot to do with the specifics of the new system. It seems the poems of the daughter of Kamo no Yasunori (her own name is unknown) indicate she was familiar with yin-yang theory or at least more broadly with Chinese philosophy, but that’s a topic for a separate article (stay tuned), and it's not quite the same, obviously.

The Tsuchimikado didn’t aim to create a specific ideology or systems of beliefs. Therefore, individual onmyōji - or, to be more accurate, individual people with onmyōji licenses - in theory could pursue new ideas. This in some cases lead to controversies: for instance, some of the people involved in the (in)famous 1827 Osaka trial of alleged Christians (whether this label really is applicable is a matter of heated debate) were officially licensed onmyōji. Some of them did indeed possess translated books written by Portuguese missionaries, which obviously reflected Catholic outlook. However, Bernard Faure suggests that some of the Edo period onmyōji might have pursued Portuguese sources not strictly because of an interest in Catholicism but simply to obtain another source of astronomical knowledge.

The legacy of onmyōdō

In the Meiji period, onmyōdō was banned alongside shugendō. While the latter tradition experienced a revival in the second half of the twentieth century, the former for the most part didn’t. However, that doesn’t mean the history of onmyōdō ends once and for all in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Even today in some parts of Japan there are local religious traditions which, while not identical with historical onmyōdō, retain a considerable degree of influence from it. An example often cited in scholarship is Izanagi-ryū (いざなぎ流) from the rural Monobe area in the Kōchi Prefecture. Mitsuki Ueno stresses that the occasional references to Izanagi-ryū as “modern onmyōdō” in literature from the 1990s and early 2000s are inaccurate, though. He points out they downplay the unique character of this tradition, and that it shows a variety of influences. Similar arguments have also been made regarding local traditions from the Chūgoku region.

Until relatively recently, in scholarship onmyōdō was basically ignored as superstition unworthy of serious inquiries. This changed in the final decades of the twentieth century, with growing focus on the Japanese middle ages among researchers. The first monographs on onmyōdō were published in the 1980s. While it’s not equally popular as a subject of research as esoteric Buddhism and shugendō, formerly neglected for similar reasons, it has nonetheless managed to become a mainstay of inquiries pertaining to the history of religion in Japan.

Yoshitaka Amano's illustration of Baku Yumemakura's fictionalized portrayal of Abe no Seimei (right) and other characters from his novels (reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Of course, it’s also impossible to talk about onmyōdō without mentioning the modern “onmyōdō boom”. Starting with the 1980s, onmyōdō once again became a relatively popular topic among writers. Novel series such as Baku Yumemakura’s Onmyōji, Hiroshi Aramata’s Teito Monogatari or Natsuhiko Kyōgoku’s Kyōgōkudō and their adaptations in other media once again popularized it among general audiences. Of course, since these are fantasy or mystery novels, their historical accuracy tends to vary (Yumemakura in particular is reasonably faithful to historical literature, though). Still, they have a lasting impact which would be impossible to accomplish with scholarship alone.

Shikigami: historical truth, historical fiction, or both?

You might have noticed that despite promising a history of shikigami, I haven’t used this term even once through the entire crash course in history of onmyōdō. This was a conscious choice. Shikigami do not appear in any onmyōdō texts, even though they are a mainstay of texts about onmyōdō, and especially of modern literature involving onmyōji.

It would be unfair to say shikigami and their prominence are merely a modern misconception, though. Virtually all of the famous legends about onmyōji feature shikigami, starting with the earliest examples from the eleventh century. Based on Konjaku Monogatari, there evidently was a fascination with shikigami at the time of its compilation. Fujiwara no Akihira in the Shinsarugakuki treats the control of shikigami as an essential skill of an onmyōji, alongside the abilities to “freely summon the twelve guardian deities, call thirty-six types of wild birds (...), create spells and talismans, open and close the eyes of kijin (鬼神; “demon gods”), and manipulate human souls”.

It is generally agreed that such accounts, even though they belong to the realm of literary fiction, can shed light on the nature and importance of shikigami. They ultimately reflect their historical context to some degree. Furthermore, it is not impossible that popular understanding of shikigami based on literary texts influenced genuine onmyōdō tradition. It’s worth pointing out that today legends about Abe no Seimei involving them are disseminated by two contemporary shrines dedicated to him, the Seimei Shrine (晴明神社) in Kyoto and the Abe no Seimei Shrine (安倍晴明神社) in Osaka. Interconnected networks of exchange between literature and religious practice are hardly a unique or modern phenomenon.

However, even with possible evidence from historical literature taken into account, it is not easy to define shikigami. The word itself can be written in three different ways: 式神 (or just 式), 識神 and 職神, with the first being the default option. The descriptions are even more varied, which understandably lead to the rise of numerous interpretations in modern scholarship. Carolyn Pang in her recent treatments of shikigami, which you can find in the bibliography, has recently divided them into five categories. I will follow her classification below.

Shikigami take 1: rikujin-shikisen

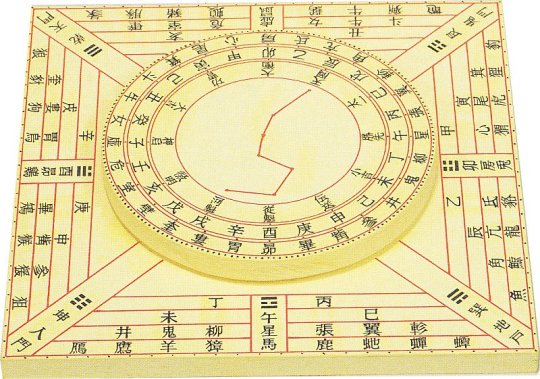

An example of shikiban, the divination board used in rikujin-shikisen (Museum of Kyoto, via onmarkproductions.com; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

A common view is that shikigami originate as a symbolic representation of the power of shikisen (式占) or more specifically rikujin-shikisen (六壬式占), the most common form of divination in onmyōdō. It developed from Chinese divination methods in the Nara period, and remained in the vogue all the way up to the sixteenth century, when it was replaced by ekisen (易占), a method derived from the Chinese Book of Changes.

Shikisen required a special divination board known as shikiban (式盤), which consists of a square base, the “earth panel” (地盤, jiban), and a rotating circle placed on top of it, the “heaven panel” (天盤, tenban). The former was marked with twelve points representing the signs of the zodiac and the latter with representations of the “twelve guardians of the months” (十二月将, jūni-gatsushō; their identity is not well defined). The heaven panel had to be rotated, and the diviner had to interpret what the resulting combination of symbols represents. Most commonly, it was treated as an indication whether an unusual phenomenon (怪/恠, ke) had positive or negative implications. It’s worth pointing out that in the middle ages the shikiban also came to be used in some esoteric Buddhist rituals, chiefly these focused on Dakiniten, Shōten and Nyoirin Kannon. However, they were only performed between the late Heian and Muromachi periods, and relatively little is known about them. In most cases the divination board was most likely modified to reference the appropriate esoteric deities.

Shikigami take 2: cognitive abilities

While the view that shikigami represented shikisen is strengthened by the fact both terms share the kanji 式, a variant writing, 識神, lead to the development of another proposal. Since the basic meaning of 識 is “consciousness”, it is sometimes argued that shikigami were originally an “anthropomorphic realization of the active psychological or mental state”, as Caroline Pang put it - essentially, a representation of the will of an onmyōji. Most of the potential evidence in this case comes from Buddhist texts, such as Bosatsushotaikyō (菩薩処胎経).

However, Bernard Faure assumes that the writing 識神 was a secondary reinterpretation, basically a wordplay based on homonymy. He points out the Buddhist sources treat this writing of shikigami as a synonym of kushōjin (倶生神). This term can be literally translated as “deities born at the same time”. Most commonly it designates a pair of minor deities who, as their name indicates, come into existence when a person is born, and then records their deeds through their entire life. Once the time for Enma’s judgment after death comes, they present him with their compiled records. It has been argued that they essentially function like a personification of conscience.

Shikigami take 3: energy

A further speculative interpretation of shikigami in scholarship is that this term was understood as a type of energy present in objects or living beings which onmyōji were believed to be capable of drawing out and harnessing to their ends. This could be an adaptation of the Daoist notion of qi (氣). If this definition is correct, pieces of paper or wooden instruments used in purification ceremonies might be examples of objects utilized to channel shikigami.

The interpretation of shikigami as a form of energy is possibly reflected in Konjaku Monogatari in the tale The Tutelage of Abe no Seimei under Tadayuki. It revolves around Abe no Seimei’s visit to the house of the Buddhist monk Kuwanten from Hirosawa. Another of his guests asks Seimei if he is capable of killing a person with his powers, and if he possesses shikigami. He affirms that this is possible, but makes it clear that it is not an easy task. Since the guests keep urging him to demonstrate nonetheless, he promptly demonstrates it using a blade of grass. Once it falls on a frog, the animal is instantly crushed to death. From the same tale we learn that Seimei’s control over shikigami also let him remotely close the doors and shutters in his house while nobody was inside.

Shikigami take 4: curse As I already mentioned, arts which can be broadly described as magic - like the already mentioned jujutsu or juhō (呪法, “magic rituals”) - were regarded as a core part of onmyōji’s repertoire from the Heian period onward. On top of that, the unlicensed onmyōji were almost exclusively associated with curses. Therefore, it probably won’t surprise you to learn that yet another theory suggests shikigami is simply a term for spells, curses or both. A possible example can be found in Konjaku Monogatari, in the tale Seimei sealing the young Archivist Minor Captains curse - the eponymous curse, which Seimei overcomes with protective rituals, is described as a shikigami.

Kunisuda Utagawa's illustration of an actor portraying Dōman in a kabuki play (wikimedia commons)

Similarities between certain descriptions of shikigami and practices such as fuko (巫蠱) and goraihō (五雷法) have been pointed out. Both of these originate in China. Fuko is the use of poisonous, venomous or otherwise negatively perceived animals to create curses, typically by putting them in jars, while goraihō is the Japanese version of Daoist spells meant to control supernatural beings, typically ghosts or foxes. It’s worth noting that a legend according to which Dōman cursed Fujiwara no Michinaga on behalf of lord Horikawa (Fujiwara no Akimitsu) involves him placing the curse - which is itself not described in detail - inside a jar.

Mitsuki Ueno notes that in the Kōchi Prefecture the phrase shiki wo utsu, “to strike with a shiki”, is still used to refer to cursing someone. However, shiki does not necessarily refer to shikigami in this context, but rather to a related but distinct concept - more on that later.

Shikigami take 5: supernatural being

While all four definitions I went through have their proponents, yet another option is by far the most common - the notion of shikigami being supernatural beings controlled by an onmyōji. This is essentially the standard understanding of the term today among general audiences. Sometimes attempts are made to identify it with a specific category of supernatural beings, like spirits (精霊, seirei), kijin or lesser deities (下級神, kakyū shin). However, none of these gained universal support. Generally speaking, there is no strong indication that shikigami were necessarily imagined as individualized beings with distinct traits.

The notion of shikigami being supernatural beings is not just a modern interpretation, though, for the sake of clarity. An early example where the term is unambiguously used this way is a tale from Ōkagami in which Seimei sends a nondescript shikigami to gather information. The entity, who is not described in detail, possesses supernatural skills, but simultaneously still needs to open doors and physically travel.

An illustration from Nakifudō Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

In Genpei Jōsuiki there is a reference to Seimei’s shikigami having a terrifying appearance which unnerved his wife so much he had to order the entities to hide under a bride instead of residing in his house. Carolyn Pang suggests that this reflects the demon-like depictions from works such as Abe no Seimei-kō Gazō (安倍晴明公画像; you can see it in the Heian section), Fudōriyaku Engi Emaki and Nakifudō Engi Emaki.

Shikigami and related concepts

A gohō dōji, as depicted in the Shigisan Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

The understanding of shikigami as a “spirit servant” of sorts can be compared with the Buddhist concept of minor protective deities, gohō dōji (護法童子; literally “dharma-protecting lads”). These in turn were just one example of the broad category of gohō (護法), which could be applied to virtually any deity with protective qualities, like the historical Buddha’s defender Vajrapāṇi or the Four Heavenly Kings. A notable difference between shikigami and gohō is the fact that the former generally required active summoning - through chanting spells and using mudras - while the latter manifested on their own in order to protect the pious. Granted, there are exceptions. There is a well attested legend according to which Abe no Seimei’s shikigami continued to protect his residence on own accord even after he passed away. Shikigami acting on their own are also mentioned in Zoku Kojidan (続古事談). It attributes the political downfall of Minamoto no Takaakira (源高明; 914–98) to his encounter with two shikigami who were left behind after the onmyōji who originally summoned them forgot about them.

A degree of overlap between various classes of supernatural helpers is evident in texts which refer to specific Buddhist figures as shikigami. I already brought up the case of the kushōjin earlier. Another good example is the Tendai monk Kōshū’s (光宗; 1276–1350) description of Oto Gohō (乙護法). He is “a shikigami that follows us like the shadow follows the body. Day or night, he never withdraws; he is the shikigami that protects us” (translation by Bernard Faure). This description is essentially a reversal of the relatively common title “demon who constantly follow beings” (常随魔, jōzuima). It was applied to figures such as Kōjin, Shōten or Matarajin, who were constantly waiting for a chance to obstruct rebirth in a pure land if not placated properly.

The Twelve Heavenly Generals (Tokyo National Museum, via wikimedia commons)

A well attested group of gohō, the Twelve Heavenly Generals (十二神将, jūni shinshō), and especially their leader Konpira (who you might remember from my previous article), could be labeled as shikigami. However, Fujiwara no Akihira’s description of onmyōji skills evidently presents them as two distinct classes of beings.

A kuda-gitsune, as depicted in Shōzan Chomon Kishū by Miyoshi Shōzan (Waseda University History Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Granted, Akihira also makes it clear that controlling shikigami and animals are two separate skills. Meanwhile, there is evidence that in some cases animal familiars, especially kuda-gitsune used by iizuna (a term referring to shugenja associated with the cult of, nomen omen, Iizuna Gongen, though more broadly also something along the lines of “sorcerer”), were perceived as shikigami.

Beliefs pertaining to gohō dōji and shikigami seemingly merged in Izanagi-ryū, which lead to the rise of the notion of shikiōji (式王子; ōji, literally “prince”, can be another term for gohō dōji). This term refers to supernatural beings summoned by a ritual specialist (祈祷師, kitōshi) using a special formula from doctrinal texts (法文, hōmon). They can fulfill various functions, though most commonly they are invoked to protect a person, to remove supernatural sources of diseases, to counter the influence of another shikiōji or in relation to curses.

Tenkeisei, the god of shikigami

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

The final matter which warrants some discussion is the unusual tradition regarding the origin of shikigami which revolves around a deity associated with this concept.

In the middle ages, a belief that there were exactly eighty four thousand shikigami developed. Their source was the god Tenkeisei (天刑星; also known as Tengyōshō). His name is the Japanese reading of Chinese Tianxingxing. It can be translated as “star of heavenly punishment”. This name fairly accurately explains his character. He was regarded as one of the so-called “baleful stars” (凶星, xiong xing) capable of controlling destiny. The “punishment” his name refers to is his treatment of disease demons (疫鬼, ekiki). However, he could punish humans too if not worshiped properly.

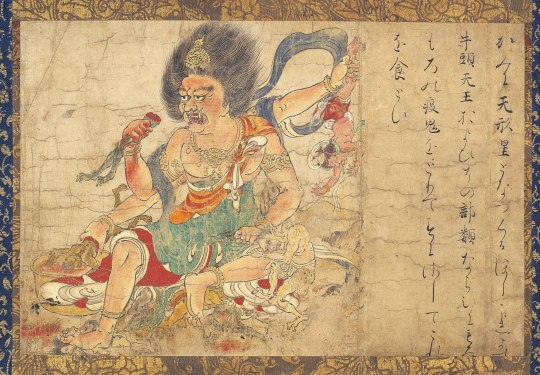

Today Tenkeisei is best known as one of the deities depicted in a series of paintings known as Extermination of Evil, dated to the end of the twelfth century. He has the appearance of a fairly standard multi-armed Buddhist deity. The anonymous painter added a darkly humorous touch by depicting him right as he dips one of the defeated demons in vinegar before eating him. Curiously, his adversaries are said to be Gozu Tennō and his retinue in the accompanying text. This, as you will quickly learn, is a rather unusual portrayal of the relationship between these two deities.

I’m actually not aware of any other depictions of Tenkeisei than the painting you can see above. Katja Triplett notes that onmyōdō rituals associated with him were likely surrounded by an aura of secrecy, and as a result most depictions of him were likely lost or destroyed. At the same time, it seems Tenkeisei enjoyed considerable popularity through the Kamakura period. This is not actually paradoxical when you take the historical context into account: as I outlined in my recent Amaterasu article, certain categories of knowledge were labeled as secret not to make their dissemination forbidden, but to imbue them with more meaning and value.

Numerous talismans inscribed with Tenkeisei’s name are known. Furthermore, manuals of rituals focused on him have been discovered. The best known of them, Tenkeisei-hō (天刑星法; “Tenkeisei rituals”), focuses on an abisha (阿尾捨, from Sanskrit āveśa), a ritual involving possession by the invoked deity. According to a legend was transmitted by Kibi no Makibi and Kamo no Yasunori. The historicity of this claim is doubtful, though: the legend has Kamo no Yasunori visit China, which he never did. Most likely mentioning him and Makibi was just a way to provide the text with additional legitimacy.

Other examples of similar Tenkeisei manuals include Tenkeisei Gyōhō (天刑星行法; “Methods of Tenkeisei Practice”) and Tenkeisei Gyōhō Shidai (天刑星行法次第; “Methods of Procedure for the Tenkeisei Practice”). Copies of these texts have been preserved in the Shingon temple Kōzan-ji.

The Hoki Naiden also mentions Tenkeisei. It equates him with Gozu Tennō, and explains both of these names refer to the same deity, Shōki (商貴), respectively in heaven and on earth. While Shōki is an adaptation of the famous Zhong Kui, it needs to be pointed out that here he is described not as a Tang period physician but as an ancient king of Rajgir in India. Furthermore, he is a yaksha, not a human. This fairly unique reinterpretation is also known from the historical treatise Genkō Shakusho. Post scriptum The goal of this article was never to define shikigami. In the light of modern scholarship, it’s basically impossible to provide a single definition in the first place. My aim was different: to illustrate that context is vital when it comes to understanding obscure historical terms. Through history, shikigami evidently meant slightly different things to different people, as reflected in literature. However, this meaning was nonetheless consistently rooted in the evolving perception of onmyōdō - and its internal changes. In other words, it reflected a world which was fundamentally alive. The popular image of Japanese culture and religion is often that of an artificial, unchanging landscape straight from the “age of the gods”, largely invented in the nineteenth century or later to further less than noble goals. The case of shikigami proves it doesn’t need to be, though. The malleable, ever-changing image of shikigami, which remained a subject of popular speculation for centuries before reemerging in a similar role in modern times, proves that the more complex reality isn’t necessarily any less interesting to new audiences.

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, A Religion in Search of a Founder?

Idem, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Makoto Hayashi, The Female Christian Yin-Yang Master

Jun’ichi Koike, Onmyōdō and Folkloric Culture: Three Perspectives for the Development of Research

Irene H. Lin, Child Guardian Spirits (Gohō Dōji) in the Medieval Japanese Imaginaire

Yoshifumi Nishioka, Aspects of Shikiban-Based Mikkyō Rituals

Herman Ooms, Yin-Yang's Changing Clientele, 600-800 (note there is n apparent mistake in one of the footnotes, I'm pretty sure the author wanted to write Mesopotamian astronomy originated 4000 years ago, not 4 millenia BCE as he did; the latter date makes little sense)

Carolyn Pang, Spirit Servant: Narratives of Shikigami and Onmyōdō Developments

Idem, Uncovering Shikigami. The Search for the Spirit Servant of Onmyōdō

Shin’ichi Shigeta, Onmyōdō and the Aristocratic Culture of Everyday Life in Heian Japan

Idem, A Portrait of Abe no Seimei

Katja Triplett, Putting a Face on the Pathogen and Its Nemesis. Images of Tenkeisei and Gozutennō, Epidemic-Related Demons and Gods in Medieval Japan

Mitsuki Umeno, The Origins of the Izanagi-ryū Ritual Techniques: On the Basis of the Izanagi saimon

Katsuaki Yamashita, The Characteristics of On'yōdō and Related Texts

192 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh no ...

Someone aware of my recently-finished catalog of Sun Wukong's powers and skills indirectly requested that I make a list of powers from Fengshen yanyi (封神演義, c. 1620).

But I don't have the mental energy for it. Plus, I am not as familiar with the book as I am JTTW. I'll pass the torch onto someone else ... COUGH @ryin-silverfish COUGH.

#journey to the west#jttw#fengshen yanyi#fsyy#list of powers#magic powers#twitter#sun wukong#monkey king#magic#chinese magic#taoist magic#daoist magic#buddhist magic#pass the torch

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ming and Qing Taoist tokens (Ling Pai 令牌 aka Lei Ling 雷令or Wu Lei Hao Ling 五雷號令) used in the Thunder Rites (Lei Fa 雷法). Mostly from Lushan Taoist school (閭山派), Fujian.

The tokens are made of wood, often peach wood or jujube, however, jade, ivory, bamboo root, etc. are allowed. The rounded top represents Heavens and the rectangular base – Earth.

The Ling Pai are engraved with signs corresponding to those divinities or forces with which the practitioner interacts during the Rites. The patterns and shapes may vary depending on the Taoist school and lineage, but the overall structure remains recognizable.

Photo: © Lin Mengyi, Xuanwu Daomen Taoist Research Center (林孟毅 玄武道門 道教研究中心), Taiwan.

#qing dynasty#qing#ming dynasty#ming#taoism#taoist#taoist immortal#yuan dynasty#taoist sorcery#taoist magic#chinese mythology#daoism#daoist#chinese myth#chinese culture#ancient china#taoist spell#fu talisman#taoist talisman#taoist ritual#leifa#taoist seals#thunder rites#雷法#xuanwu#真武#zhenwu#玄武#玄天上帝#xuantian shangdi

244 notes

·

View notes

Note

I can easily imagine a situation where Wukong is actually fem or trans actually. Like, China, especially ancient China, is a hugely patriarchal society, and Wukong is born into a matriarchal society. One that has a pretty significant language barrier considering Wukong describes speaking chinese or any none monkey language really as "speaking human." It's easy to imagine a situation where there wasn't really a good descriptor for what Wukong was to her tribe other than "Chief" or "King" or little baby Wukong not knowing the proper pronouns to a language he's not quite fluent in yet accidentally claiming herself to be King when Queen or Chieftess would be a more appropriate title. And history just... never realizes it was a translation mistake or that Wukong was actually a girl until MK becomes Wukong's successor. It could even be a situation where Wukong hid her gender when one considers the views of women at the time and the fact she spent several years in the presence of a very aggressive flirt and pervert, even if Baijie probably wouldn't have ever actually done anything just his presence done would make her uncomfortable

Just little ideas based in what you said about the story not really changing much if Wukong were female

Prev.

I can def see a situation in LMK where Wukong identifies as a girl (personal hc is genderfluid) and just... got tired of correcting people.

Younger Wukong didn't exactly have the correct word for her status amongst the troop in "Human" language so she uses "King" since it's the closest. "Queen" didn't sound right cus that meant the King's mate from what she saw.

We know that Subodhi takes on acolytes of all genders, so he had no problem with Wukong (then Shihou) wanting to learn daoist & buddhist magic. He did think Wukong was a guy at first simply cus he didn't think to ask. He did have some old-fashioned "Women = Yin. Yin is bad" views though, and that led to a few arguments between him and his most outspoken student.

No one in Heaven or the Seas bothered checking cus "Thats a Monkey". Except for whoever was in charge of electing Wukong for the stable-monkey job - that was a directed hit at her (in ancient china female monkeys were kept around horses for luck/scaring off wolves). When Sun Wukong realised that she had been given a job even below a stable-boy simply for her body and/or gender identity, she flipped out.

Being elected a Peach Orchard Maiden was a lot better, which made her even more upset that she wasn't allowed to attend the Queen's Banquet - the Orchard Maidens got to go! Why couldn't she!? The real reason turned out to be that the other Maidens were actually the Jade Emperor and Xiwangmu's daughters - a fact that's often forgotten amongst even the nobles of the Celestial Realm. The Maidens hadn't been able to explain that it was an immediate-family-only party when Wukong decided to crash it.

Bonus for Stone Matriarch au: Xiwangmu immediately recognises a startling familiar destruction in this little demon. Like she's seeing a mirror of her younger self; a wild queen destroying the Heavens to prove her worth. The Queen Mother even pauses at the sight of the chaos on Flower Fruit Mountain, thinking she's seeing one of her own daughters throwing a tantrum.

Ofc the relationship between Fem!Wukong and the Brotherhood gets altered a bit. I feel that they knew Wukong's gender and supported her 100%. DBK goes full "You looking at my little sister, punk!?"-mode on anyone that even looks at Wukong. PIF helped a lot with understanding "human girly-stuff" when Wukong joined the Celestials.

Macaque knew from day 1, and it doesn't change his level of devotion to his King - though he makes a point of referring to Wukong as the "Beautiful Monkey King". Guaranteed to leave Wukong blushing. Macaque's own gender identity is a question mark - he takes what gender he can steal from others.

It also only served to reinforce Azure's projected martyrdom onto Wukong - who would be the best figurehead for the rebellion than a woman who suffers as much pain as the Bodhisattva Guanyin?

Tripitaka likely faints once or twice at the revelation that his bodyguard is a bloodthirsty woman - but quickly gets over it cus thats the least of his worries. Tthough he does panic at the thought of Wukong being like certain other female demons towards monks -Wukong quickly puts his worries to rest; Tripitaka isn't her type.

Sha Wujing and Ao Lie didn't mind but they made sure to have Wukong's input for when she preferred to be addressed as male - usually amongst humans or celestials.

Zhu Bajie on the other hand...

It took Bajie a lot of rejection to get the point that the Monkey King was not a free lady. After a few years their relationship became a lot more "annoying siblings"-vibes, but the initial creep factor always made Wukong uncomfortable.

MK (he/they transmasc) discovers the Monkey King's true gender and *immediately* works to correct his language.

MK: "Monkey- wait, do you prefer being called King or Queen? I don't want to misgender you if possible." Wukong, surprised: "Uh, King is fine bud. It's sort of my brand now anyway." MK: "Okay! Never be afraid to correct me if I mess up." (*points to trans pride pin on his jacket*) :D Wukong, honestly touched: "Aww."

Later when the rest of the Noodle Gang meets Wukong, there's a little surprise - mostly from Tang who's rambling how all the translation inconsistencies finally make sense! Mei shrieks with glee - the Monkey King is "The Ultimate Girl Boss!". Sandy politely asks for Wukong's preferred pronouns if she's comfortable sharing them. Pigsy is a lot more understanding of why Wukong felt the need to hide her gender for so long.

Pigsy: "Let me guess, you pulled a Mulan cus of a certain... pervert in your travel party." Wukong: "Eh not entirely... Bajie figured it out after a few months, but by then he already saw me as One of the Guys. Felt weird to bathe or sleep near him though - dude stared." Pigsy: "Gross." Wukong: "Mega-gross."

Wukong's dynamic with Spider Queen becomes a bit funnier, since she likely doesn't know Wukong's gender. Second she learns that her opponent is "a fellow Queen" she gains a lot more respect for her. Female spiders are overwhelmingly the strongest after all.

If it becomes wide knowledge during LMK, then Wukong gets an intense public reaction, not just from fans (she tells Fire Star to deal with the media dumpster fire) but from demons that knew her back in the day that never knew and are surprised, or did know and are extremely proud of her for coming out.

DBK loudly declares "MY BABY SISTER HAS RETURNED!". The king he's been forced to fight felt like a complete stranger until Wukong started owning her gender identity again. He is extremely supportive to an embarassing extent. Red Son feels elated, especially since they're coming to terms with their own gender indentity.

And ofc a lot of this is me projecting as a trans masc person - I tend to automatically see Sun Wukong's as afab either way. This idea can have Wukong either as afab genderfluid or trans fem, whatever tickles the brain.

#sun wukong#lmk mk#qi xiaotian#six eared macaque#liu er mihou#gender bend#gender swap#jttw#journey to the west#lmk#lego monkie kid#lmk aus

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching jentry chau and I'm trying to imagine this from another characters perspective like. Imagine you're an American, or even wilder, a first generation Nigerian American. And it turns out all of Chinese mythology is real. Jiangshi are real. Ghosts are real. Daoist magic. Underworld demons. Some girl from school has fire magic hands and is shooting at ghosts all the time and that's just just like normal now. Like she burned your house down by accident when you were kids. But like. That doesn't mean all mythology is real. Like it's just Chinese mythology. Vampires? Not real. Jiangshi, colloquially referred to as Chinese vampires? Real. Demons? Only the Chinese variety. Like imagine waking up one day to discover that one culture got all the afterlife and supernatural lore right. Like just one. Everyone else was wrong. And it's not yours. Like forget mr Jesus or whatever you have to be worried about daoist magic now. It's kind of sending me, conceptually, how funny that would be

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celestial Dragon (Tianlong)

Legends of the Dragon

The myriad legends of the Chinese Dragon permeate ancient Chinese civilization and shaped their culture even today. Its benevolence signifies greatness, goodness and blessings. Instead of being feared and hated the Chinese dragons are highly respected creatures of good fortune that bring ultimate abundance, prosperity and good fortune. Chinese mythology says dragons control the rain, rivers, lakes, and seas. Many Chinese cities have pagodas where people used to burn incense to ask the dragons to favor their crops or change the weather. Dragons are referred to as the divine mythical creature.

As an animal possessed of magical abilities the Chinese dragon is able to shrink to the size of a silk worm; and then swell up to fill the entire space between heaven and earth. It can make itself visible or invisible, as it so chooses. It can take on human form or that of another animal to carry out some secret mission.

Everything connected with Eastern Dragons is blessed. The Year of the Dragon that takes place ever twelve years is lucky. Present-day Oriental astrologers claim that children born during Dragon Years enjoy health, wealth, and long life. (1964 and 1976 were Dragon Years.

Dragons are so wise that they have been royal advisors. A thirteenth-century Cambodian king spent his nights in a golden tower, where he consulted with the real ruler of the land a nine-headed dragon. Eastern Dragons are vain, even though they are wise. They are insulted when a ruler doesn’t follow their advice, or when people don’t honor their importance. Then, by thrashing about, dragons either stop making rain and cause water shortages, or they breathe black clouds that bring storms and floods.

Types of Dragons

There is more than one type of dragon depicted in Chinese art. In early times there were four main kinds of dragon with many other sub-divisions:

The heavenly or celestial dragon (tian-long) was the celestial guardian who protected the heavens, supporting the mansions of the gods and shielded them from decay. The Tian-long could fly and are depicted with or without wings they are always drawn with five toes while all other dragons are shown with four or three toes.

Spiritual Dragon

The spiritual dragons (shen-long) were the weather makers. These giants floated across the sky and due to their blue color that changed constantly were difficult to see clearly. Shen-long governed the wind, clouds and rain on which all agrarian life depended. Chinese people took great care to avoid offending them for if they grew angry or felt neglected, the result was bad weather, drought of flood.

Earth Dragon

Dragons that ruled the rivers, springs and lakes were called Earth dragons (di-long). They hide in the depths of deep watercourses in grand palaces. Many Chinese fairy tales spin yarns of men and women taken into these submarine castles to be granted special favors or gifts. Some of the di-long even mated with women to produce half-human dragon children.

Treasure Dragon

Believed to live in caves deep in the earth the (fu-can-long) or treasure dragon had charge of all the precious jewels and metals buried in the earth. Each of these dragons had a magical pearl that was reputed to multiply if it was touched. This pearl was as symbol of the most valuable treasure, wisdom.

Over the ages many other forms and hybrid animals related to the Chinese dragon have emerged as part of dragon lore. There are said to be nine distinct offshoots of the dragon that are carved as mystical symbols on doors, gates, swords, and other implements as means of protection and as harbingers of good fortune.

The Dragon Pearl

The luminous ball or pearl often depicted under the dragon’s chin or seen to be spinning in the air, pursued by one or two dragons is thought to be a symbolic representation of the ‘sacred pearl’ of wisdom or yang energy. Pearl symbolism, like lunar symbolism arises from Daoist roots and the connections, are extremely The dragon's pearlcomplex. This pearl can be said to stand most often for ‘truth’ and ‘life’ – perhaps even everlasting life which is made available to those who perceive the truth and attain enlightenment.

The dragon’s pearl can also be thought of as a symbol for universal Qi the progenitor of all energy and creation. The dragons seem to be depicted in attitudes of pursuit. He is seen to be reaching out eagerly to clutch at the elusive object, mouth open in anticipation and eyes bulging with anticipation of achieving the prize afforded by clutching the pearl.

In connection with the dragon the pearl has been called the image of thunder, of the moon, of the sun, of the egg emblem of the dual influences of nature, and the ‘pearl of potentiality’. The pearl is most often depicted as a spiral or a globe. In some paintings it is sometimes red, dragons eggsometimes gold, sometimes the bluish white of a true pearl. The pearl is often accompanied by little jagged flashes that seem to spark out from it, like flames; and it almost always has an appendage in the form of a small undulating sprout, not unlike the first young shoot from a bean.

In Daoist concepts the moon, pearls, dragons and serpents are inextricably linked. Like the snake that is reborn when it sheds its skin, the moon is reborn each month, and both are symbols of immortality. Like the dragon, the moon is always associated with water; its undeniable power over the tides is believed to extend to all liquids on earth. The dragons that lived in the sea were said to be inordinately fond of pearls and collected them and watched over them in great submarine palaces. -The Dragons of China

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ask/Writing Masterlist (irregularly updating)

Ryin(阿璎), 23. She/They. First Gen Chinese student. Ryin_Silverfish on AO3. Currently hyperfixating on old Chinese novels. casual Zhiguai tales and LMK enjoyer.

Investiture of the Gods/FSYY:

Why are the Daoist immortals fighting?

Did Yuanshi Tianzun manipulate Shen Gongbao?

Chan, Jie, and possible prejudice against yaoguai

Azure Lion and the other Bodhisattvas' steeds in FSYY

Daji's fox form in FSYY Pinghua

The historical Su Daji

Is Shen Gongbao a yaoguai?

Are all yaoguai irredeemable monsters in FSYY?

Ao Bing and the dragons Nezha fought

Does deification wipe your memory and personality?

Bi Gan and the Great Fox Massacre

More discussion about prejudice against yaoguai

How old was Su Daji the human when she died?

Differences between FSYY novel and Pinghua

Musing on FSYY's view of fate and its possible effects on Yang Jian

Master Yuding

The messy marriages of FSYY

Is Daji a goddess in the novel?

Names of immortal masters in FSYY

Just for fun: the FSYY drinking game

Nezha's age in FSYY

Nezha's death and resurrection in FSYY

What happened to the original Daji?

Lady Shiji aka the Rock Demoness

Chinese Fox Spirits:

Auspicious/Demonic Foxes

More on fox spirits

The inner core of foxes

Foxes and their association with Fire

Notable fox spirits

The foxes of 狐狸缘全传

Has Daji ever been worshipped as a goddess?

Fox masks

The foxes of Liaozhai

Weaknesses and abilities of fox spirits

Three resource collections on Chinese fox spirits: 1, 2, 3

Human-fox hybrids

Can foxes and their descendents magically know if someone's telling the truth?

The magical properties of fox saliva

Fox exams and Heavenly Foxes

Are male foxes more malicious?

More on fox exams

Offerings to fox spirits

The "Lady Fox Immortal"

Chinese Mythos in General:

The Precious Scroll of Erlang

Into the Erlang-verse: Li, Zhao, Yang

Can immortal masters romance their students?

Why we don't power-rank characters in God-Demon novels

A brief overview of Chang'e

On Chinese Religion and "Respect"

The 28 Lunar Mansions

Can the Heavenly Emperor be replaced + a primer on dynastic successions

A Guide to the Chinese Underworld (and what it isn't)

Is Nüwa JE's daughter?

Weaver Girl

Can yaoguais a/o their descendents enter the Celestial Bureaucracy?

Queen Mother of the West and her husband(s)

Bixia Yuanjun, Lady of Mt. Tai

Erlang's dad

The story that gives us the name "Yang Jian"

On the transformation of Erlang's image (and his relationship with JE in JTTW)

Erlang's mom, Lotus Lantern, and a neat little discovery

Erlang cameos in other stories and Zajus

Erlang's mom-saving story in Chinese operas

Child Manjushri, or: the absurdity of pinning a definitive age on gods

The strange modern ship of Mengpo/Yuelao, and Mengpo's myths

The half-beast form of QMoW

Does Erlang have a wife/love interest?

Nezha's mom

A overview of Gonggong and his mythos

Some introductory sources on the Chinese Underworld

Mythos-inspired Worldbuilding:

Dragons of the Four Seas

LMK S5 and a possible "Celestial Council of Regents" AU

LMK S5 Fix-it: the Four Divine Beasts

Character/Story Analysis (JTTW + LMK)

Heart and Mind: Tripitaka

Local Lion Uncle enjoyer goes on a rant

On SWK and his fear of death

Why the Dead People Supreme Court?

No, seriously, why?

Chinese Underworld =/= Christian Hell

LMK S4, Havoc in Heaven, and revolutions

Why I dislike the "class warfare" reading of Havoc in Heaven

In Defence of Li Jing...ha, as fucking if

On Yin-Yang, Chaos/Order, and the Harbringer

JTTW's view on the Three Religions

Disjointed S5 Reactions

"Chaos doesn't work that way in traditional Chinese Cosmology"

Xiangliu, the Nine-headed Bird, and Jiutou Chong

Lotus Lantern: The Summaries

Part 1: Precious Scroll of Chenxiang

Part 2: The Epic of Prince Chenxiang

Part 3: Lotus Lantern 1.0 + 2.0

Part 4: Chenxiang and the Male-Female Swords

My Fanfics:

Climbing the Sky

The Wild Son

Bodhicitta

The Serpent and the Deluge

South Seas Sojourn

Journey of the Gods AU sideblog

Masterpost 2

266 notes

·

View notes