#Danpei

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Boxers of Yesterday Today and Tomorrow

Storytelling in Sports

A normal person otherwise devoid of any specific purpose finds their raison dêtre in training for the martial arts.

This single sentence storyline is a fundamental story type in many Asian stories. You find it in Chinese Shaolin Temple epics, Japanese and Chinese rival school epics, Thai action films, Spanish and French sword-fighting fictions, and even American dramas and comedies. Rocky is the most notable example of an American version of this story type. In every example, the storytelling rarely focuses on the action and instead puts the onus on the relationships the character has with the world.

The most notable Japanese examples are Samurai films and combat/sports manga. In most of these examples the protagonist is relatively normal, allowing the audience to relate to them. Then the narrative introduces a reason for the character to evolve during exposition. The main character then is introduced to a mentor, not unlike Joseph Cambell’s example path of the Hero’s Journey. In sports narratives this mentor is usually in the form of a coach or trainer and they are uplifted from normal person to a superior athlete.

In sports manga and other sports fiction, the answer to all problems is always the same: Training.

Discipline provides confidence and training provides strength. Both of these are held together with ‘guts’ or determination. The athletic hero is confronted with stronger and stronger opponents and continues to train until he can defeat them. This type of ‘superiority through training and determination’ is a cornerstone of most Japanese stories. Many deal with an argument between skill and talent as well. In most cases learned skill defeats natural-born talent after enough training has occurred.

The lessons taught in these stories are almost always the same:

Nothing good is achieved without effort

Trust your friends and family

Strength is the product of discipline

Determination will give you victory

In this essay I will be focusing on three Boxing stories from Japanese culture. We will explore their meanings and narratives, the lessons taught, and the importance of their stories on culture.

Joe Learns to Box: Yesterday’s Tomorrow

Pugilism has a long history of nobility and violence. Boxing is enjoyed the world over as the world’s most basic of martial arts. Everyone can do it, but few can master it. Despite the sport’s organization being mostly from a European base, the United States has become the de facto home of the sport. It spread across the world and entered Japan in 1854 and became popular despite Japan’s dominance in the martial arts world.

Post World War II anti-American sentiment led to a lull in the sport, but boxing matches continued. As Japanese classical art like Emakimono evolved into Manga, artists struggled for meaning in a post nuclear world. One particular author found this meaning in the story of a prize fighter from the slums of Tokyo. Asao Takamori under the pen name Ikki Kajiwara teamed up with the artist Tetsuya Chiba to create their seminal work, Ashita no Joe. The story captured the spirit of Japanese determination and also their desperation in the face of their defeat of WW II and the subsequent reconstruction period. Joe’s redemption and anger belonged to the youth of the day and inspired other authors, artists, and aspiring boxers to try their best to grow and learn what it means to be strong.

Using this story as a lens to view other anime and manga you can see its influence everywhere you look, from popular to obscure. Notably Takamori’s story inspired a renaissance of boxing fandom in the late 1970’s. Despite there being several titles going to Featherweight and Welterweight champions in Japan during the time, boxing was relatively unpopular due to its association with the US. Ashita no Joe, or “Tomorrow’s Joe” captured a moment and helped to move its fans forwards toward a brighter tomorrow.

The titular character Joe Yabuki, is a tough-as-nails drifter that wanders into a shantytown and runs into an alcoholic boxing trainer, who sees a bright future hiding inside the brash youth and attempts to coax it out of him. Because of his terrible attitude and criminal behavior he is instead put in jail. Joe redeems himself (somewhat at least) and pushes himself to become a professional boxer. His story can be seen as a successful transition from an economic outcast into a functional member of society. In this case, society can be said to be the true villain of the story. Joe has either rejected society or society has rejected him, he has either turned to violence or been rejected due to his reliance on violence to solve his problems. Similar story origins can be found in gangster movies but also in stories like Rambo: Firstblood.

Classic and contemporary gangster films have characters that as children are shown a violent way of life, either by design or necessity. These children then grow into violent adults, full of anger and contempt for society and view the world as a thing to be possessed or conquered. Society ultimately rejects them for their violent and destructive natures. Stories like Rambo on the other hand, have a well liked child grow into a life of violence for a noble cause, but are ultimately unable to separate this violence from their personality. They eventually reject society as they cannot find a place and the violence in them serves no purpose.

Yabuki is a bit of a mystery as we have no context to put him in, but as with both other character types, his violence serves no purpose. He is defined by his violence and it colors all of his actions towards others. Joe is a fundamentally unlikable character, full of anger, bitterness, and child-like pettiness. His relationship with those that eventually come to care about him serves to instill societal norms in him in an attempt to turn him into a better person.

Instead of society itself, I propose that poverty is the real enemy of Joe and his friends. Every day is a struggle for all of them in San’ya. Economic disparity is on parade throughout the narrative, from the driftwood houses along the Namida Bashi (Bridge of Tears) to the sky scrapers and mansions of the mega-wealthy. Joe is carted around the world boxing in various countries, but he never really grows out of the slums in his mind. Joe is obviously a victim of his own stubbornness, but he was made that way because of lack of economic opportunity. This is one of the primary stumbling blocks on display in gangster stories, but instead of becoming an enforcer and earning a living in the underworld, Joe becomes a homeless wanderer, evoking the Japanese concept of a Ronin. A skilled fighter, disgraced and masterless but clinging on to his own moral code as he wanders from town to town.

While Joe is a product of his time, his story is no less poignant for modern audiences. I enjoy Ashita no Joe for a variety of reasons, but one of the best is its lack of focus on form. Chiba’s art is almost romantic with emphasis on Joe’s inability to care about the world, and Takamori’s rambling narrative is like a daydream at times with no obvious focus or form. If I had to compare it to music, Joe’s story is like a free form jazz with some repeating phrases and a theme, but mostly feels disorganized and yet is familiar. Joe has emblazoned himself into the minds and hearts of Japanese artists and athletes for decades and will continue to guide hearts, minds, and fists for decades to come.

Ippo Steps into the Ring: Yesterday’s Today

In sharp contrast to the unlikable character study of Joe Yabuki, we now come to possibly the most likable character in all of Japanese sports manga. Makunouchi Ippo, the titular character of Hajime no Ippo, has a boundless optimism that is almost never extinguished and his ability to win through sheer will power is incredibly inspirational. When I meet people that do not watch any anime or read manga and they ask me what to start with, Ippo’s story is always close to the top of the list. Of the three stories explored in this work, Ippo is my favorite. I have watched Ippo's road to fight against Date Eji more times that I can remember.

As with Joe, Ippo is a product of his environment and time. He is an example of modern boxing theory and technique tempered with lessons from the past. The origins of boxing are represented by the retired boxers in the narrative and the techniques of famous modern era boxers are on display in this love letter to obscure boxing styles. Ippo is the son of a fishing boat captain whose good naturedness causes him to forgo friendships and childhood distractions to help his mother operate the fishing boat business that supports them after his father's death. He is bullied and taunted until a chance encounter with a professional boxer saves him from a group of wannabe hoodlums underneath a bridge. Ippo awakens to find himself in the world of boxing and puts all of his considerable determination into making himself a professional licensed boxer. He manages this and continues to help his mother without complaining or losing his intoxicating optimism.

Makunouchi is meant to be a representation of the perfect son in Japanese culture. He is mannered, self-effacing, and always does the right thing. Conceptually, Ippo is almost as far as possible from Joe as a character. The world that Ippo exists in is also just as opposed to Joe’s world. While economics do factor into the narrative a bit, it is not a focus of the story. In this world the common everyday experience of Japan’s average citizen is on display. The manga is in full swing with shonen style comedy and slice of life stories, Ippo’s life is beset with heartache, rivals, highschool life, and bad dating advice.

The thing that really sets Ippo apart is the illustration of effort and power in the art of the near constant boxing and sparring matches. Although the art is a bit dated, it still communicates emotion and drama in a way that no other sports show has ever done in my opinion. Some of the later fights continue to give me chills and despite knowing the outcome of every fight, I still find myself cheering on Ippo. The color palette for everyday life is somewhat subdued but still contains a range of colors, but the fights are incredibly bright with flashes and huge blast lines. Usually this style of art would be a turn off for me in other mediums, but somehow Hajime no Ippo gets away with it.

If Joe’s story is Jazz, then Ippo is a Rock Ballad. Guitars scream at times, but other times the story is whimsical or romantic. George Morikawa’s skillful blend of emotions bring you through a chord progression of inspiring notes building to larger than life crescendos, that crash down upon you in a hail of pummeling fists, and knock you out with the power solos that are the crowd pumping championship matches. The drama conveyed in Takamura’s face while he attempts to control himself from opening a refrigerator while dieting to make weight, and the joyful head nod that Ippo gives when he defeats the first villain of the show are highlights that play on an loop in my mind drenched in squealing guitar riffs and the roar of the crowd.

One of the craziest things about watching the show for me is the effect it has on my exercise habits. If I ever want to get motivated to work out, I put on the first season of Ippo. Just as Ashita no Joe’s world is meant to capture the desperation of the downtrodden and the realism of his world, Hajime no Ippo seems to look at the world through Ippo’s guileless naivete. Ippo’s world is both very realistic and simultaneously extremely exaggerated. This offputting juxtaposition is difficult to navigate at times when you are wondering what is real and what is imagination.

Junkyard Dog Bites Mankind: Today’s Tomorrow

When writing about the future one of the things you have to ask yourself is ‘what will X be like in the future?’ Yō Moriyama, Katsuhiko Manabe, and Kensaku Kojima asked themselves, what would boxing be like in the future? How would people fight in the age of machines and artificial intelligence? Gearless Joe is the answer, or rather the inverse of the answer as he is essentially an anti-hero forgoing the future methods of robotic-assisted carnage, for old fashioned human-powered beatdowns.

If Hajime no Ippo is Classic Rock and Ashita no Joe is Jazz, then Megalobox is Industrial HipHop. It is hard, but rhythmic, artistic and catchy. By far the most polished of the 3 examples, it is an extremely fun watch and is effectively a stylized re-telling of Ashita no Joe. The nameless protagonist chooses the moniker ‘Joe’ meaning a man with no real name, but also an obligatory hat-tip to the source material that inspired them. Originally self-named ‘Junk Dog’ is employed to fight in fixed matches in the underworld that our original Joe eschewed. He feels trapped by his life and while attempting to force change, ends up essentially trapping himself even worse. Through a twist of fate, he is forced into the world of professional legitimate boxing in which if he loses he will die. In this brutal and vicious dog-eat-dog world, Gearless Joe shines as a likable anti-hero.

Unlike Ashita no Joe, society is not the big bad guy. There are of course real bad guys in Megalobox in the form of gangsters and fixers and hustlers, but the true villain in the story is greed. The story paints a nasty picture of corruption in the slums and then opens up the world into the bright lights of the legitimate world. With every turn you see another sign of economic elitism, not the least of which is Joe’s lack of personal identity. He is a non-person in the society and cannot even be allowed into the city, there is of course a blackmarket answer for everything and Gearless is allowed to come into the futuristic world of the Megalonia tournament and fight for his life.

His trainer sets up their gym under a bridge bearing more than a passing likeness to the same Bridge of Tears from Ashita no Joe. His team and Gearless Joe are the only desperate ones in the narrative, so unlike the feeling of inclusivity that Yabuki’s gang felt, Gearless Joe feels isolated.

An Abridged Story of A Bridge: Tears to Cheers to Fears

Dieting and sweat, training and bruises, bright lights and cheering crowds. There are a lot of things that the stories share due to the sheer concept of boxing, but one thing that stands out the most to me about the similarities is the geography. Ashita no Joe and Hajime no Ippo canonically occur in Tokyo whereas Megalobox occurs in the fictional ‘Administrative Zone’, but a common point with all stories is their reliance on a single feature of the landscape, a bridge. The bridge in Ashita no Joe is a famous one called Namida Bashi or the Bridge of Tears. It got this name due to the requirement that future prisoners of Kozukahara penitentiary would have to say their goodbyes to their loved ones on that bridge as you had to cross the Omoigawa river to get to the prison. The river was moved and the bridge doesn’t exist anymore, but in its time it was a symbol of loss and heartache and of loss of agency. It was no small symbolism for Joe’s trainer Danpei to open his ramshackle gym under the bridge. Joe’s relatively brief stint in prison and their constant struggle for survival, coupled with Joe’s incessant need to cause trouble always lead to loss, heartache, and usually a loss of agency. Many of Ashita no Joe’s most important moments occur in and around the bridge, borrowing context from the bridge’s reputation. Each of these events is usually a precursor to a major event in the context of Joe Yabuki.

Even though the bridge is now gone, the area around the bridge’s location is close to the Tiato and Arakawa districts that have several rivers that run through them with modern bridges that look remarkably like the one that serves as a setting for many of the critical plot turns in Hajime no Ippo. We see the entire storyline of Ippo’s relationship with Umezawa (Ippo’s school bully that is turned into his greatest fan) unfold under and around the bridge. Ippo manages to catch the 10 leaves that teach him how to jab next to the bridge, and several key conversations and character introductions are in and around the canal next to the bridge. I don’t feel that this use of the canal next to this particular bridge is random and suspect that if it isn’t just an icon from the author’s youth, it is an homage to Ashita no Joe’s use of the Bridge of Tears.

Ippo’s story doesn’t revolve around the same themes, so the bridge being similar but different is important in my mind. Being under the bridge, where Joe and Danpei were, is when Ippo is at his weakest and most vulnerable. The wise tree nearby becomes his first teacher and Ippo learns that he can grow stronger through dedication and training. This causes the bridge to become a symbol for growth and hope for a better tomorrow for Ippo. Even Umezawa crosses the bridge on his way to become a better person. Like Ippo is the inverse of Joe, the bridge in Hajime no Ippo is the inverse of the Namida Bashi. Everytime a character crosses the bridge they are stronger than they were before.

Megalobox as a revamp of Ashita no Joe also has a bridge, and of course they have their ‘gym’ underneath it. The symbolism in Megalobox is missing however and the bridge takes on a different meaning. Joe Yabuki and his trainer Danpei are poor in a community of poor people and they have a community to help them make their gym a home. Gearless Joe and Gansaku Nanbu have no such community to help them and must toil essentially on their own. The bridge and the river are essentially signs of the reality of illegal squatting, evidence that they do not belong in the world they find themselves in. As Gearless Joe and Nanbu rock the boat in entirely different ways than Joe Yabuki, death at the hands of the corruption of the city is their motivating factor instead of prison and poverty. The bridge over their heads instead becomes a symbol of cover, of hiding in plain sight. Not unlike the nameless boxer’s decision to choose the anonymous name of ‘Joe’.

To my reckoning there are a lot of examples of symbolism in all three stories, but none are shared so visibly and with as great an impact as the bridges over the heads of heroes while they train and live life outside the ring. Plans are formed, strategies devised, and history is made under these bridges, while clueless people stroll above them not knowing what extreme determination and strength of will lies beneath.

#boxing#hajime no ippo#ippo makunouchi#ashita no joe#megalo box#anime#animation#stories#modern mythology#heroes journey#joseph campbell#joe yabuki#gearless joe#Danpei#Gansaku Nanbu#Yō Moriyama#Katsuhiko Manabe#Kensaku Kojima#Asao Takamori#Ikki Kajiwara#Tetsuya Chiba#manga#manga art

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

ashita no joe………………

#ashita no joe#joe yabuki#danpei tange#challenging myself to draw as fast as i can….. for the sake of tomorrow#anyway im like 23 episodes in and going insane…. its so good.. its so good

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

does mr joe yabuki know how much i'd die for him

#this scene is even better when voiced but ehhh i couldnt encode it for shit#mine#official art#ashita no joe#joe yabuki#danpei tange

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

quis esboçá-los no meu estilo :)

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

Economy class had so much space in the 70s

#look at that business class legroom#how is joe able to stretch out like that#ashita no joe#joe yabuki#danpei tange

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

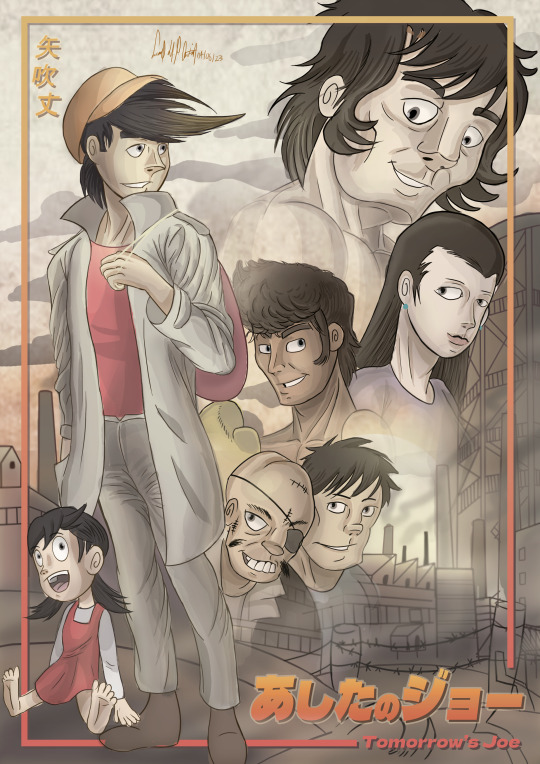

Art made on Photoshop CS5 during 3 days.

DO NOT RE-POST MY ART WITHOUT MY PERMITION!!!

Ashita no Joe © by Ikki Kajiwara & Tetsuya Chiba/TMS Entertainment.

#Art#Fanart#Digital#Digital Art#Photoshop CS5#Photoshop#Anime#Tomorrow's Joe#Ashita no Joe#Boxing#Sports#Fighting#Joe Yabuki#Rikiishi Tooru#Yoko Shiraki#Tange Danpei#Carlos Rivera#70s#80s#Manga#Tetsuya Chiba#tomorrow

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Huh, now this intrigues me!

Joe's design is okay, not much different but DANPEI WITHOUT FACIAL HAIR?? That's throwing me off so much 😰

Advertisement for the upcoming publication of the first chapter of ‘Ashita no Joe’ in Weekly Shonen Magazine (december 1967)

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ashita no Joe - 1970

Titulo: Ashita no Joe

Autor: Ikki Kajiwara, Chiba Tetsuya, Takamori Asaki

Direção: Dezaki Osamu

Gênero: Ação, Boxe, Luta, adaptação de Manga, Shounen, Esporte, Drama

Produtora: Mushi Production

Exibição Original: 1970 – 1971

Número de Episódios: 79

Até onde você iria em busca de um sonho?

Danpei Tange é um boxeador frustrado. Largou os ringues quando perdeu a visão de um dos olhos, e desistiu de ser treinador quando foi traído por seu discípulo. Desde então, vive uma vida de miséria, andando com mendigos e enchendo a cara o dia inteiro.

Um dia, chega à cidade onde Tange mora um jovem. Violento, orgulhoso, aproveitador e mentiroso, Joe Yabuki arranja brigas, trapaceia, rouba e mente. No entanto, sua força e agilidade em suas brigas de rua despertam a atenção de Danpei, que vê em Joe o potencial para se tornar um grande boxeador, talvez até mesmo um campeão.

É aí que começa Ashita no Joe, a saga de Joe Yabuki para deixar de ser um simples marginal e se tornar um grande campeão do boxe. De início a contragosto, Joe se recusa a treinar com Danpei, mas tudo muda quando entram em sua vida a bela Yoko Shiraki e o valente Rikiishi Tohru, aquele que se tornaria o grande rival de Joe até o fim da série.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finished Ashita no Joe, 9/10, if I had to pick a word to describe this story I would say Great. Because it is great, it has great characters, great fights, and a great story, but it’s just missing something that gives it that push into 10/10. First off, the art is about as good as you’d expect from something written in the 60s, but it just adds to the series’ charm. The story itself isn’t anything special, it’s a classic story, our Protagonist Joe keeps fighting and fighting stronger and stronger opponents until he can’t anymore. Joe Yabuki is what really makes this story click, he’s constantly fighting forwards just so he can fight again tomorrow, he’s an empty man with only boxing left for himself and he’s causing so much pain by continuing on down his path of boxing. He’s an inspiring tale of tenacity and will to grow and keep going in what you love. And he isn’t the only compelling character, the stories of Danpei and Youko intertwining with his to help tell the story of Ashita no Joe to its fullest. And that’s the very reason I hesitate to give it a 10/10, I’ve given stories with less quality 10/10s before, but that’s because they have something special to them, but Ashita no Joe is just an excellent story and there’s nothing else to it, 9/10

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Manga Monday: Ashita no Joe: Fighting for Tomorrow 1

Author: Asao TakamoriArtist: Tetsuya ChibaPublisher: Vertical ComicsReleased: December 24, 2024Find it on Goodreads | More Manga Summary: Joe Yabuki is no stranger to fighting – he’s lived in some rough places over the years and knows how to take care of himself. Yet one fight in the slums of Tokyo may just change everything for him. This latest fight caught the attention of Danpei Tange, a…

#Asao Takamori#Ashita no Joe: Fighting for Tomorrow#Ashita no Joe: Fighting for Tomorrow 1#Cover#Manga#Manga Monday#Manga Mondays#Tetsuya Chiba#Vertical Comics

0 notes

Text

it is still pretty funny to me that there is like a total lack of interest in translating dodge danpei to english but dodge danko gets one

0 notes

Text

Honoo no Toukyuujo DODGE DANPEI RELOADED[炎の闘球児 ドッジ弾平 リローデッド]

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why is Joe so unsettled by this scene?

Joe's running on the beach when he spots Jose Mendoza there too, playing with his kids. Yoko offers to introduce him but he says he's not into scenes of Jose as a family man, or that it's "hard to watch."

The question is...why, though? Why would the sight of Jose spending time with his family unnerve Joe so much? He never says, but I think we can figure it out.

I'm sure many people would say that since Joe's an orphan with no known family, it's super obvious that he would be uncomfortable seeing something he never had.

Except...I don't think this is true.

Joe doesn't have any problem spending time around families. He spends lots of time with the Hayashis and had a part-time job at their store. He's pretty bad at/disinterested in his job, but he seems to have a good time around them.

Another thing is, Jose in the anime asks where Joe comes from and where he will go, and in response Joe says that a rootless guy like him can go anywhere. It's a cool quote. Except, by now, Joe already has roots. He doesn't know his birth family, but the people in the Doya have become his adopted family. After this, he even goes souvenir shopping for them. Joe treasures his connections with them deeply. Here he is, having the time of his life with them.

So, no, Joe isn't uncomfortable with scenes of all families, he's just uncomfortable seeing Jose's family.

Why?

Two things have happened. One, by this point, Joe is extremely punch-drunk. He's known for a while that something's very, very wrong with his body. Two, not only did he receive the news that Carlos lost to Jose by KO, but he learned that he's been severely brain damaged...and has vanished without a trace. Joe asks around about what happened to his best friend Carlos and gets the response that he's been 'wandering' around Venezuela and no one has seen him since.

People in the fandom say that the saddest part of Carlos' fate is his permanent brain damage, but to me, personally, the biggest tragedy is that Carlos was abandoned and forsaken in his hour of need. It's very obvious that this is the case, before we even see Carlos again, because no one knows what happened to him. His manager is gone. The reporters who were all over Carlos are gone.

It feels like Joe was the deepest and most significant relationship Carlos has ever had, and Joe knows that. Otherwise Joe wouldn't be the only person he remembers and somehow finds after getting punch-drunk.

I think Joe was worried that he was next in line. As an orphan, he treasures every relationship he has, and he must have been wondering if he'll slowly lose them all as his condition deteriorates. What he fears is abandonment. And I mean, he already got a small taste of it a while ago.

A little while back, when he told Noriko that all he desired in the ring was to become white ash, she said she couldn't keep up...and then she slowly faded from his life and married Nishi instead. He didn't actually reject Noriko. She was the one who gave up on him because it was too painful to be around him.

It's even more obvious in the anime. Joe calls out to her and she's gone. Whether Joe had feelings for her or not, I'm sure this sat in his mind unpleasantly. He even had a thoughtful, vaguely glum expression during hers and Nishi's wedding.

This is a guy who had a breakdown when Danpei started coaching Aoyama, and in the manga he seems shocked and upset when Yoko says she won't watch his match against Kim.

He's scared that people will leave him.

When he saw Jose's family at the beach, I don't think he was unsettled by seeing what he never had. I think he was unsettled by the thought of losing whatever he gained. No wonder he wants to keep a distance. Jose's kids don't act all that different from the Doya kids.

I think this is another reason why he was so weirdly friendly to Yoko in Hawaii. The punch-drunk syndrome obviously played a role in his behavioral changes, but besides that...

She's a person he's known for years, and they have a very antagonistic relationship, but she's still there, with him, at his side in a strange country he doesn't know. He must have found that reassuring on some level.

16 notes

·

View notes