#Daniel Guérin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Max Stirner rehabilitated the individual at a time when the philosophical field was dominated by Hegelian anti-individualism and most reformers in the social field had been led by the misdeeds of bourgeois egotism to stress its opposite: was not the very word “socialism” created as antonym to “individualism”? Stirner exalted the intrinsic value of the unique individual, that is to say, one cast in a single unrepeatable mold (an idea which has been confirmed by recent biological research). For a long time this thinker remained isolated in anarchist circles, an eccentric followed by only a tiny sect of intelligent individualists. Today, the boldness and scope of his thought appear in a new light. The contemporary world seems to have set itself the task of rescuing the individual from all the forms of alienation which crush him’ those of individual slavery and those of totalitarian conformism. In a famous article written in 1933, Simone Weil complained of not finding in Marxist writings any answer to questions arising from the need to defend the individual against the new forms of oppression coming after classical capitalist oppression. Stirner set out to fill this serious gap as early as the mid-nineteenth century. He wrote in a lively style, crackling with aphorisms: “Do not seek in self-renunciation a freedom which denies your very selves, but seek your own selves... Let each of you be an all-powerful I.” There is no freedom but that which the individual conquers for himself. Freedom given or conceded is not freedom but “stolen goods.” “There is no judge but myself who can decide whether I am right or wrong.” “The only things I have no right to do are those I do not do with a free mind.” “You have the right to be whatever you have the strength to be.” Whatever you accomplish you accomplish as a unique individual: “Neither the State, society, nor humanity can master this devil.” In order to emancipate himself, the individual must begin by putting under the microscope the intellectual baggage with which his parents and teachers have saddled him. He must undertake a vast operation of “desanctification,” beginning with the so-called morality of the bourgeoisie: “Like the bourgeoisie itself, its native soil, it is still far too close to the heaven of religion, is still not free enough, and uncritically borrows bourgeois laws to transplant them to its own ground instead of working out new and independent doctrines.”

Daniel Guérin

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

The word anarchist seems to me too restrictive and I don't use it unless it is joined by the word communist.

— Daniel Guérin

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daniel Guérin – Burjuvazi ve Çıplak Kollular (2024)

Daniel Guérin’in Fransız Devrimi sırasında Fransa’daki sınıf gerilimlerini incelediği çalışması ‘Burjuvazi ve Çıplak Kollular’, 31 Mayıs 1793 yılında Jirondenler’in düşmesinden itibaren ilk modern sınıf çatışmasının ortaya çıkışına tanıklık etmemize yardımcı oluyor ve burjuva devriminin jakoben liderlerine karşı baldırı çıplaklar tarafından yönetilen proleter bir devrimin tohumlarının atıldığını…

View On WordPress

#2024#Ayrıntı Yayınları#Beyza Başer#Burjuvazi ve Çıplak Kollular#Daniel Guérin#Fransız Devrimi#Fransız Devrimi&039;nde Toplumsal Mücadeleler (1793-1795)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Saint-Just and Camille Desmoulins were not just heterosexuals, and the former's loyalty to Robespierre, to the point of agreeing to be guillotined with him, seems to have been a form of sublimated homosexuality.

Daniel Guérin, "Homosexualité et révolution"

I'm not sure what the author is trying to say about Camille, because he is not mentioned at all after that in the article.

Considering that the example of SJ and Max follows, it is most likely that he refers to the fact that he died with Danton. (In fact, before his execution, Camille wrote that he would not hide the fact that he would die for his friendship with Danton and that he would be happy to die with him). But if so, I wonder why his name is not mentioned here. Due to the "manly Danton" myth, the author is hesitant to associate something queer with him?

(I don't know whether it is appropriate to say that the deaths of Camille (for Danton) and Saint-Just (for Robespierre) are "sublimated homosexuality". I don't know much about queer studies...)

It could also be his complicated relationship with Maxime (since that his name is mentioned here), or the author thought his "vice honteux" could be homosexuality (I know some people have made similar claims, but I don't see any conclusive evidence).

Or did Guérin discover something about Camille that we don't know?

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

G.6 What are the ideas of Max Stirner?

To some extent, Stirner’s work The Ego and Its Own is like a Rorschach test. Depending on the reader’s psychology, he or she can interpret it in drastically different ways. Hence, a few have tried to use Stirner’s ideas to defend capitalism while others have used them to argue for anarcho-syndicalism. For example, many in the anarchist movement in Glasgow, Scotland, took Stirner’s “Union of Egoists” literally as the basis for their anarcho-syndicalist organising in the 1940s and beyond. Similarly, we discover the noted anarchist historian Max Nettlau stating that ”[o]n reading Stirner, I maintain that he cannot be interpreted except in a socialist sense.” [A Short History of Anarchism, p. 55] In this section of the FAQ, we will indicate why, in our view, the latter, syndicalistic, interpretation of egoism is far more appropriate than the capitalistic one.

It should be noted, before continuing, that Stirner’s work has had a bigger impact on individualist anarchism than social anarchism. Benjamin Tucker and many of his comrades embraced egoism when they became aware of The Ego and Its Own (a development which provoked a split in individualist circles which, undoubtedly, contributed to its decline). However, his influence was not limited to individualist anarchism. As John P. Clark notes, Stirner “has also been seen as a significant figure by figures who are more in the mainstream of the anarchist tradition. Emma Goldman, for example, combines an acceptance of many of the principles of anarcho-syndicalism and anarcho-communism with a strong emphasis on individuality and personal uniqueness. The inspiration for this latter part of her outlook comes from thinkers like … Stirner. Herbert Read has commented on the value of Stirner’s defence of individuality.” [Max Stirner’s Egoism, p. 90] Daniel Guérin’s classic introduction to anarchism gives significant space to the German egoist, arguing he “rehabilitated the individual at a time when the philosophical field was dominated by Hegelian anti-individualism and most reformers in the social field had been led by the misdeeds of bourgeois egotism to stress its opposite” and pointed to “the boldness and scope of his thought.” [Anarchism, p. 27] From meeting anarchists in Glasgow during the Second World War, long-time anarchist activist and artist Donald Rooum likewise combined Stirner and anarcho-communism. In America, the short-lived Situationist influenced group “For Ourselves” produced the inspired The Right to Be Greedy: Theses on the Practical Necessity of Demanding Everything, a fusion of Marx and Stirner which proclaimed a “communist egoism” based on the awareness that greed “in its fullest sense is the only possible basis of communist society.”

It is not hard to see why so many people are influenced by Stirner’s work. It is a classic, full of ideas and a sense of fun which is lacking in many political writers. For many, it is only known through the criticism Marx and Engels subjected it too in their book The German Ideology. As with their later attacks on Proudhon and Bakunin, the two Germans did not accurately reflect the ideas they were attacking and, in the case of Stirner, they made it their task to make them appear ridiculous and preposterous. That they took so much time and energy to do so suggests that Stirner’s work is far more important and difficult to refute than their notoriously misleading diatribe suggests. That in itself should prompt interest in his work.

As will become clear from our discussion, social anarchists have much to gain from understanding Stirner’s ideas and applying what is useful in them. While some may object to our attempt to place egoism and communism together, pointing out that Stirner rejected “communism”. Quite! Stirner did not subscribe to libertarian communism, because it did not exist when he was writing and so he was directing his critique against the various forms of state communism which did. Moreover, this does not mean that anarcho-communists and others may not find his work of use to them. And Stirner would have approved, for nothing could be more foreign to his ideas than to limit what an individual considers to be in their best interest. Unlike the narrow and self-defeating “egoism” of, say, Ayn Rand, Stirner did not prescribe what was and was not in a person’s self-interest. He did not say you should act in certain ways because he preferred it, he did not redefine selfishness to allow most of bourgeois morality to remain intact. Rather he urged the individual to think for themselves and seek their own path. Not for Stirner the grim “egoism” of “selfishly” living a life determined by some guru and which only that authority figure would approve of. True egoism is not parroting what Stirner wrote and agreeing with everything he expounded. Nothing could be more foreign to Stirner’s work than to invent “Stirnerism.” As Donald Rooum put it:

“I am happy to be called a Stirnerite anarchist, provided ‘Stirnerite’ means one who agrees with Stirner’s general drift, not one who agrees with Stirner’s every word. Please judge my arguments on their merits, not on the merits of Stirner’s arguments, and not by the test of whether I conform to Stirner.” [“Anarchism and Selfishness”, pp. 251–9, The Raven, no. 3, p. 259fn]

With that in mind, we will summarise Stirner’s main arguments and indicate why social anarchists have been, and should be, interested in his ideas. Saying that, John P. Clark presents a sympathetic and useful social anarchist critique of his work in Max Stirner’s Egoism. Unless otherwise indicated all quotes are from Stirner’s The Ego and Its Own.

So what is Stirner all about? Simply put, he is an Egoist, which means that he considers self-interest to be the root cause of an individual’s every action, even when he or she is apparently doing “altruistic” actions. Thus: “I am everything to myself and I do everything on my account.” Even love is an example of selfishness, “because love makes me happy, I love because loving is natural to me, because it pleases me.” He urges others to follow him and “take courage now to really make yourselves the central point and the main thing altogether.” As for other people, he sees them purely as a means for self-enjoyment, a self-enjoyment which is mutual: “For me you are nothing but my food, even as I am fed upon and turned to use by you. We have only one relation to each other, that of usableness, of utility, of use.” [p. 162, p. 291 and pp. 296–7]

For Stirner, all individuals are unique (“My flesh is not their flesh, my mind is not their mind,”) and should reject any attempts to restrict or deny their uniqueness: “To be looked upon as a mere part, part of society, the individual cannot bear — because he is more; his uniqueness puts from it this limited conception.” Individuals, in order to maximise their uniqueness, must become aware of the real reasons for their actions. In other words they must become conscious, not unconscious, egoists. An unconscious, or involuntary, egoist is one “who is always looking after his own and yet does not count himself as the highest being, who serves only himself and at the same time always thinks he is serving a higher being, who knows nothing higher than himself and yet is infatuated about something higher.” [p. 138, p. 265 and p. 36] In contrast, egoists are aware that they act purely out of self-interest, and if they support a “higher being,” it is not because it is a noble thought but because it will benefit them.

Stirner himself, however, has no truck with “higher beings.” Indeed, with the aim of concerning himself purely with his own interests, he attacks all “higher beings,” regarding them as a variety of what he calls “spooks,” or ideas to which individuals sacrifice themselves and by which they are dominated. First amongst these is the abstraction “Man”, into which all unique individuals are submerged and lost. As he put it, “liberalism is a religion because it separates my essence from me and sets it above me, because it exalts ‘Man’ to the same extent as any other religion does to God … it sets me beneath Man.” Indeed, he “who is infatuated with Man leaves persons out of account so far as that infatuation extends, and floats in an ideal, sacred interest. Man, you see, is not a person, but an ideal, a spook.” [p. 176 and p.79] Among the many “spooks” Stirner attacks are such notable aspects of capitalist life as private property, the division of labour, the state, religion, and (at times) society itself. We will discuss Stirner’s critique of capitalism before moving onto his vision of an egoist society and how it relates to social anarchism.

For the egoist, private property is a spook which “lives by the grace of law” and it “becomes ‘mine’ only by effect of the law”. In other words, private property exists purely “through the protection of the State, through the State’s grace.” Recognising its need for state protection, Stirner is also aware that ”[i]t need not make any difference to the ‘good citizens’ who protects them and their principles, whether an absolute King or a constitutional one, a republic, if only they are protected. And what is their principle, whose protector they always ‘love’? Not that of labour”, rather it is ”interesting-bearing possession … labouring capital, therefore … labour certainly, yet little or none at all of one’s own, but labour of capital and of the — subject labourers.” [p. 251, p. 114, p. 113 and p. 114]

As can be seen from capitalist support for fascism, Stirner was correct — as long as a regime supports capitalist interests, the ‘good citizens’ (including many on the so-called “libertarian” right)) will support it. Stirner sees that not only does private property require state protection, it also leads to exploitation and oppression. As noted in section D.10, like subsequent anarchists like Kropotkin, Stirner attacked the division of labour resulting from private property for its deadening effects on the ego and individuality of the worker:

“When everyone is to cultivate himself into man, condemning a man to machine-like labour amounts to the same thing as slavery … Every labour is to have the intent that the man be satisfied. Therefore he must become a master in it too, be able to perform it as a totality. He who in a pin-factory only puts on heads, only draws the wire, works, as it were mechanically, like a machine; he remains half-trained, does not become a master: his labour cannot satisfy him, it can only fatigue him. His labour is nothing by itself, has no object in itself, is nothing complete in itself; he labours only into another’s hands, and is used (exploited) by this other.” [p. 121]

Stirner had nothing but contempt for those who defended property in terms of “natural rights” and opposed theft and taxation with a passion because it violates said rights. “Rightful, or legitimate property of another,” he stated, “will by only that which you are content to recognise as such. If your content ceases, then this property has lost legitimacy for you, and you will laugh at absolute right to it.” After all, “what well-founded objection could be made against theft” [p. 278 and p. 251] He was well aware that inequality was only possible as long as the masses were convinced of the sacredness of property. In this way, the majority end up without property:

“Property in the civic sense means sacred property, such that I must respect your property … Be it ever so little, if one only has somewhat of his own — to wit, a respected property: The more such owners … the more ‘free people and good patriots’ has the State. “Political liberalism, like everything religious, counts on respect, humaneness, the virtues of love … For in practice people respect nothing, and everyday the small possessions are bought up again by greater proprietors, and the ‘free people’ change into day labourers.” [p. 248]

Thus free competition “is not ‘free,’ because I lack the things for competition.” Due to this basic inequality of wealth (of “things”), ”[u]nder the regime of the commonality the labourers always fall into the hands of the possessors … of the capitalists, therefore. The labourer cannot realise on his labour to the extent of the value that it has for the customer.” [p. 262 and p. 115] In other words, the working class is exploited by the capitalists and landlords.

Moreover, it is the exploitation of labour which is the basis of the state, for the state “rests on the slavery of labour. If labour becomes free, the State is lost.” Without surplus value to feed off, a state could not exist. For Stirner, the state is the greatest threat to his individuality: ”I am free in no State.” This is because the state claims to be sovereign over a given area, while, for Stirner, only the ego can be sovereign over itself and that which it uses (its “property”): “I am my own only when I am master of myself.” Thus the state “is not thinkable without lordship and servitude (subjection); for the State must will to be the lord of all that it embraces.” Stirner also warned against the illusion in thinking that political liberty means that the state need not be a cause of concern for ”[p]olitical liberty means that the polis, the State, is free; … not, therefore, that I am free of the State… It does not mean my liberty, but the liberty of a power that rules and subjugates me; it means that one of my despots … is free.” [p. 116, p. 226, p. 169, p. 195 and p. 107]

Therefore Stirner urges insurrection against all forms of authority and dis-respect for property. For ”[i]f man reaches the point of losing respect for property, everyone will have property, as all slaves become free men as soon as they no longer respect the master as master.” And in order for labour to become free, all must have “property.” “The poor become free and proprietors only when they rise.” Thus, ”[i]f we want no longer to leave the land to the landed proprietors, but to appropriate it to ourselves, we unite ourselves to this end, form a union, a société, that makes itself proprietor … we can drive them out of many another property yet, in order to make it our property, the property of the — conquerors.” Thus property “deserves the attacks of the Communists and Proudhon: it is untenable, because the civic proprietor is in truth nothing but a propertyless man, one who is everywhere shut out. Instead of owning the world, as he might, he does not own even the paltry point on which he turns around.” [p. 258, p. 260, p. 249 and pp. 248–9]

Stirner recognises the importance of self-liberation and the way that authority often exists purely through its acceptance by the governed. As he argues, “no thing is sacred of itself, but my declaring it sacred, by my declaration, my judgement, my bending the knee; in short, by my conscience.” It is from this worship of what society deems “sacred” that individuals must liberate themselves in order to discover their true selves. And, significantly, part of this process of liberation involves the destruction of hierarchy. For Stirner, “Hierarchy is domination of thoughts, domination of mind!,” and this means that we are “kept down by those who are supported by thoughts.” [p. 72 and p. 74] That is, by our own willingness to not question authority and the sources of that authority, such as private property and the state:

“Proudhon calls property ‘robbery’ (le vol) But alien property — and he is talking of this alone — is not less existent by renunciation, cession, and humility; it is a present. Who so sentimentally call for compassion as a poor victim of robbery, when one is just a foolish, cowardly giver of presents? Why here again put the fault on others as if they were robbing us, while we ourselves do bear the fault in leaving the others unrobbed? The poor are to blame for there being rich men.” [p. 315]

For those, like modern-day “libertarian” capitalists, who regard “profit” as the key to “selfishness,” Stirner has nothing but contempt. Because “greed” is just one part of the ego, and to spend one’s life pursuing only that part is to deny all other parts. Stirner called such pursuit “self-sacrificing,” or a “one-sided, unopened, narrow egoism,” which leads to the ego being possessed by one aspect of itself. For “he who ventures everything else for one thing, one object, one will, one passion … is ruled by a passion to which he brings the rest as sacrifices.” [p. 76]

For the true egoist, capitalists are “self-sacrificing” in this sense, because they are driven only by profit. In the end, their behaviour is just another form of self-denial, as the worship of money leads them to slight other aspects of themselves such as empathy and critical thought (the bank balance becomes the rule book). A society based on such “egoism” ends up undermining the egos which inhabit it, deadening one’s own and other people’s individuality and so reducing the vast potential “utility” of others to oneself. In addition, the drive for profit is not even based on self-interest, it is forced upon the individual by the workings of the market (an alien authority) and results in labour “claim[ing] all our time and toil,” leaving no time for the individual “to take comfort in himself as the unique.” [pp. 268–9]

Stirner also turns his analysis to “socialism” and “communism,” and his critique is as powerful as the one he directs against capitalism. This attack, for some, gives his work an appearance of being pro-capitalist, while, as indicated above, it is not. Stirner did attack socialism, but he (rightly) attacked state socialism, not libertarian socialism, which did not really exist at that time (the only well known anarchist work at the time was Proudhon’s What is Property?, published in 1840 and this work obviously could not fully reflect the developments within anarchism that were to come). He also indicated why moralistic (or altruistic) socialism is doomed to failure, and laid the foundations of the theory that socialism will work only on the basis of egoism (communist-egoism, as it is sometimes called). Stirner correctly pointed out that much of what is called socialism was nothing but warmed up liberalism, and as such ignores the individual: “Whom does the liberal look upon as his equal? Man! …, In other words, he sees in you, not you, but the species.” A socialism that ignores the individual consigns itself to being state capitalism, nothing more. “Socialists” of this school forget that “society” is made up of individuals and that it is individuals who work, think, love, play and enjoy themselves. Thus: “That society is no ego at all, which could give, bestow, or grant, but an instrument or means, from which we may derive benefit … of this the socialists do not think, because they — as liberals — are imprisoned in the religious principle and zealously aspire after — a sacred society, such as the State was hitherto.” [p. 123]

Of course, for the egoist libertarian communism can be just as much an option as any other socio-political regime. As Stirner stressed, egoism “is not hostile to the tenderest of cordiality … nor of socialism: in short, it is not inimical to any interest: it excludes no interest. It simply runs counter to un-interest and to the uninteresting: it is not against love but against sacred love … not against socialists, but against the sacred socialists.” [No Gods, No Masters, vol. 1, p. 23] After all, if it aids the individual then Stirner had no more problems with libertarian communism that, say, rulers or exploitation. Yet this position does not imply that egoism tolerates the latter. Stirner’s argument is, of course, that those who are subject to either have an interest in ending both and should unite with those in the same position to end it rather than appealing to the good will of those in power. As such, it goes without saying that those who find in egoism fascistic tendencies are fundamentally wrong. Fascism, like any class system, aims for the elite to rule and provides various spooks for the masses to ensure this (the nation, tradition, property, and so on). Stirner, on the other hand, urges an universal egoism rather than one limited to just a few. In other words, he would wish those subjected to fascistic domination to reject such spooks and to unite and rise against those oppressing them:

“Well, who says that every one can do everything? What are you there for, pray, you who do not need to put up with everything? Defend yourself, and no one will do anything to you! He who would break your will has to do with you, and is your enemy. Deal with him as such. If there stand behind you for your protection some millions more, then you are an imposing power and will have an easy victory.” [p. 197]

That Stirner’s desire for individual autonomy becomes transferred into support for rulership for the few and subjection for the many by many of his critics simply reflects the fact we are conditioned by class society to accept such rule as normal — and hope that our masters will be kind and subscribe to the same spooks they inflict on their subjects. It is true, of course, that a narrow “egoism” would accept and seek such relationships of domination but such a perspective is not Stirner’s. This can be seen from how Stirner’s egoist vision could fit with social anarchist ideas.

The key to understanding the connection lies in Stirner’s idea of the “union of egoists,” his proposed alternative mode of organising society. Stirner believed that as more and more people become egoists, conflict in society will decrease as each individual recognises the uniqueness of others, thus ensuring a suitable environment within which they can co-operate (or find “truces” in the “war of all against all”). These “truces” Stirner termed

“Unions of Egoists.” They are the means by which egoists could, firstly, “annihilate” the state, and secondly, destroy its creature, private property, since they would “multiply the individual’s means and secure his assailed property.” [p. 258]

The unions Stirner desires would be based on free agreement, being spontaneous and voluntary associations drawn together out of the mutual interests of those involved, who would “care best for their welfare if they unite with others.” [p. 309] The unions, unlike the state, exist to ensure what Stirner calls “intercourse,” or “union” between individuals. To better understand the nature of these associations, which will replace the state, Stirner lists the relationships between friends, lovers, and children at play as examples. [No Gods, No Masters, vol. 1, p. 25] These illustrate the kinds of relationships that maximise an individual’s self-enjoyment, pleasure, freedom, and individuality, as well as ensuring that those involved sacrifice nothing while belonging to them. Such associations are based on mutuality and a free and spontaneous co-operation between equals. As Stirner puts it, “intercourse is mutuality, it is the action, the commercium, of individuals.” [p. 218] Its aim is “pleasure” and “self-enjoyment.” Thus Stirner sought a broad egoism, one which appreciated others and their uniqueness, and so criticised the narrow egoism of people who forgot the wealth others are:

“But that would be a man who does not know and cannot appreciate any of the delights emanating from an interest taken in others, from the consideration shown to others. That would be a man bereft of innumerable pleasures, a wretched character … would he not be a wretched egoist, rather than a genuine Egoist? … The person who loves a human being is, by virtue of that love, a wealthier man that someone else who loves no one.” [No Gods, No Masters, vol. 1, p. 23]

In order to ensure that those involved do not sacrifice any of their uniqueness and freedom, the contracting parties have to have roughly the same bargaining power and the association created must be based on self-management (i.e. equality of power). Only under self-management can all participate in the affairs of the union and express their individuality. Otherwise, we have to assume that some of the egoists involved will stop being egoists and will allow themselves to be dominated by another, which is unlikely. As Stirner himself argued:

“But is an association, wherein most members allow themselves to be lulled as regards their most natural and most obvious interests, actually an Egoist’s association? Can they really be ‘Egoists’ who have banded together when one is a slave or a serf of the other?… “Societies wherein the needs of some are satisfied at the expense of the rest, where, say, some may satisfy their need for rest thanks to the fact that the rest must work to the point of exhaustion, and can lead a life of ease because others live in misery and perish of hunger, or indeed who live a life of dissipation because others are foolish enough to live in indigence, etc., such societies … [are] more of a religious society, a communion held as sacrosanct by right, by law and by all the pomp and circumstance of the courts.” [Op. Cit., p. 24]

Therefore, egoism’s revolt against all hierarchies that restrict the ego logically leads to the end of authoritarian social relationships, particularly those associated with private property and the state. Given that capitalism is marked by extensive differences in bargaining power outside its “associations” (i.e. firms) and power within these “associations” (i.e. the worker/boss hierarchy), from an egoist point of view it is in the self-interest of those subjected to such relationships to get rid of them and replace them with unions based on mutuality, free association, and self-management. Ultimately, Stirner stresses that it is in the workers’ self-interest to free themselves from both state and capitalist oppression. Sounding like an anarcho-syndicalist, Stirner recognised the potential for strike action as a means of self-liberation:

“The labourers have the most enormous power in their hands, and, if they once become thoroughly conscious of it and used it, nothing could withstand them; they would only have to stop labour, regard the product of labour as theirs, and enjoy it. This is the sense of the labour disturbances which show themselves here and there.” [p. 116]

Given the holistic and egalitarian nature of the union of egoists, it can be seen that it shares little with the so-called free agreements of capitalism (in particular wage labour). The hierarchical structure of capitalist firms hardly produces associations in which the individual’s experiences can be compared to those involved in friendship or play, nor do they involve equality. An essential aspect of the “union of egoists” for Stirner was such groups should be “owned” by their members, not the members by the group. That points to a libertarian form of organisation within these “unions” (i.e. one based on equality and participation), not a hierarchical one. If you have no say in how a group functions (as in wage slavery, where workers have the “option” of “love it or leave it”) then you can hardly be said to own it, can you? Indeed, Stirner argues, for ”[o]nly in the union can you assert yourself as unique, because the union does not possess you, but you possess it or make it of use to you.” [p. 312]

Thus, Stirner’s “union of egoists” cannot be compared to the employer-employee contract as the employees cannot be said to “own” the organisation resulting from the contract (nor do they own themselves during work time, having sold their labour/liberty to the boss in return for wages — see section B.4). Only within a participatory association can you “assert” yourself freely and subject your maxims, and association, to your “ongoing criticism” — in capitalist contracts you can do both only with your bosses’ permission.

And by the same token, capitalist contracts do not involve “leaving each other alone” (a la “anarcho”-capitalism). No boss will “leave alone” the workers in his factory, nor will a landowner “leave alone” a squatter on land he owns but does not use. Stirner rejects the narrow concept of “property” as private property and recognises the social nature of “property,” whose use often affects far more people than those who claim to “own” it: “I do not step shyly back from your property, but look upon it always as my property, in which I ‘respect’ nothing. Pray do the like with what you call my property!” [p. 248] This view logically leads to the idea of both workers’ self-management and grassroots community control (as will be discussed more fully in section I) as those affected by an activity will take a direct interest in it and not let “respect” for “private” property allow them to be oppressed by others.

Moreover, egoism (self-interest) must lead to self-management and mutual aid (solidarity), for by coming to agreements based on mutual respect and social equality, we ensure non-hierarchical relationships. If I dominate someone, then in all likelihood I will be dominated in turn. By removing hierarchy and domination, the ego is free to experience and utilise the full potential of others. As Kropotkin argued in Mutual Aid, individual freedom and social co-operation are not only compatible but, when united, create the most productive conditions for all individuals within society.

Stirner reminds the social anarchist that communism and collectivism are not sought for their own sake but to ensure individual freedom and enjoyment. As he argued: “But should competition some day disappear, because concerted effort will have been acknowledged as more beneficial than isolation, then will not every single individual inside the associations be equally egoistic and out for his own interests?” [Op. Cit., p. 22] This is because competition has its drawbacks, for ”[r]estless acquisition does not let us take breath, take a calm enjoyment. We do not get the comfort of our possessions… Hence it is at any rate helpful that we come to an agreement about human labours that they may not, as under competition, claim all our time and toil.” [p. 268] In other words, in the market only the market is free not those subject to its pressures and necessities — an important truism which defenders of capitalism always ignore.

Forgetting about the individual was, for Stirner, the key problem with the forms of communism he was familiar with and so this “organisation of labour touches only such labours as others can do for us … the rest remain egoistic, because no one can in your stead elaborate your musical compositions, carry out your projects of painting, etc.; nobody can replace Raphael’s labours. The latter are labours of a unique person, which only he is competent to achieve.” He went on to ask “for whom is time to be gained [by association]? For what does man require more time than is necessary to refresh his wearied powers of labour? Here Communism is silent.” Unlike egoism, which answers: “To take comfort in himself as unique, after he has done his part as man!” In other words, competition “has a continued existence” because “all do not attend to their affair and come to an understanding with each other about it.” [p. 269 and p. 275] As can be seen from Chapter 8 of Kropotkin’s Conquest of Bread (“The Need for Luxury”), communist-anarchism builds upon this insight, arguing that communism is required to ensure that all individuals have the time and energy to pursue their own unique interests and dreams (see section I.4).

Stirner notes that socialising property need not result in genuine freedom if it is not rooted in individual use and control. He states “the lord is proprietor. Choose then whether you want to be lord, or whether society shall be!” He notes that many communists of his time attacked alienated property but did not stress that the aim was to ensure access for all individuals. “Instead of transforming the alien into own,” Stirner noted, “they play impartial and ask only that all property be left to a third party, such as human society. They revindicate the alien not in their own name, but in a third party’s” Ultimately, of course, under libertarian communism it is not “society” which uses the means of life but individuals and associations of individuals. As Stirner stressed: “Neither God nor Man (‘human society’) is proprietor, but the individual.” [p. 313, p. 315 and p. 251] This is why social anarchists have always stressed self-management — only that can bring collectivised property into the hands of those who utilise it. Stirner places the focus on decision making back where it belongs — in the individuals who make up a given community rather than abstractions like “society.”

Therefore Stirner’s union of egoists has strong connections with social anarchism’s desire for a society based on freely federated individuals, co-operating as equals. His central idea of “property” — that which is used by the ego — is an important concept for social anarchism because it stresses that hierarchy develops when we let ideas and organisations own us rather than vice versa. A participatory anarchist community will be made up of individuals who must ensure that it remains their “property” and be under their control; hence the importance of decentralised, confederal organisations which ensure that control. A free society must be organised in such a way to ensure the free and full development of individuality and maximise the pleasure to be gained from individual interaction and activity. Lastly, Stirner indicates that mutual aid and equality are based not upon an abstract morality but upon self-interest, both for defence against hierarchy and for the pleasure of co-operative intercourse between unique individuals.

Stirner demonstrates brilliantly how abstractions and fixed ideas (“spooks”) influence the very way we think, see ourselves, and act. He shows how hierarchy has its roots within our own minds, in how we view the world. He offers a powerful defence of individuality in an authoritarian and alienated world, and places subjectivity at the centre of any revolutionary project, where it belongs. Finally, he reminds us that a free society must exist in the interests of all, and must be based upon the self-fulfilment, liberation and enjoyment of the individual.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

books finished (not necessarily started) this year

only marking ‘strongly recommend’ (👍) and ‘don’t recommend’ (❌️). well and molière is molière lol

The Fascist Revolution: Toward a General Theory of Fascism by George Mosse (January 2) 👍

The Ba‘th and the Creation of Modern Syria by David Roberts (January 19)

The Occult Roots of Nazism: Secret Aryan Cults and their Influence on Nazi Ideology by Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke (February 20) 👍

The Brown Plague: Travels in Late Weimar and Early Nazi Germany by Daniel Guérin (March 6) 👍

Fascism in Brazil: From Integralism to Bolsonarism by Leandro Pereira Gonçalves and Odilon Caldeira Neto (March 22)

Iraqi Arab Nationalism: Authoritarian, Totalitarian, and Pro-Fascist Inclinations, 1932–1941 by Peter Wien (April 5)

Bunch of Thoughts by M.S. Golwalkar (April 11) ❌️

Hebrew Fascism in Palestine, 1922–1942 by Dan Tamir (April 18)

Latin American Dictatorships in the Era of Fascism: The Corporatist Wave by António Costa Pinto (May 2)

L’École des femmes by Molière (May 17)

A History of Fascism, 1914–1945 by Stanley Payne (May 30) 👍

Anarcho-Fascism: Nature Reborn by Jonas Nilsson (June 20) (extremely doesn’t count, basically a pamphlet) ❌️

French Colonial Fascism: The Extreme Right in Algeria, 1919–1939 by Samuel Kalman (August 23)

The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How To Get Good at It by Kelly McGonigal (October 11)

Fascism in Spain, 1923–1977 by Stanley Payne (October 27) 👍

Inside Latin America by John Gunther (November 10)

It Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis (November 24)

i have ambitions of finishing wynot’s polish politics in transition over the weekend but that’s probably not going to happen

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

non-exhaustive list of sources that are imo especially interesting/thought-provoking, just really solid, or otherwise a personal favorite:

MISC

“Leaders and Martyrs: Codreanu, Mosley and José Antonio,” Stephen M. Cullen (1986)

“Bureaucratic Politics in Radical Military Regimes,” Gregory J. Kasza (1987)

A History of Fascism, 1914–1945, Stanley Payne (1996)

The Fascist Revolution: Toward a General Theory of Fascism, George L. Mosse (1999)

Fascism Outside Europe: The European Impulse against Domestic Conditions in the Diffusion of Global Fascism, ed. Stein U. Larsen (2001)

Ancient Religions, Modern Politics: The Islamic Case in Comparative Perspective, Michael Cook (2014)

MARXISM

“Crisis and the Way Out: The Rise of Fascism in Italy and Germany,” Mihály Vajda (1972)

“Austro-Marxist Interpretation of Fascism,” Gerhard Botz (1976)

“Fascism: some common misconceptions,” Noel Ignatin (1978)

“Gramsci’s Interpretation of Fascism,” Walter L. Adamson (1980)

ARGENTINA

“The Ideological Origins of Right and Left Nationalism in Argentina, 1930–43,” Alberto Spektorowski (1994)

“The Making of an Argentine Fascist. Leopoldo Lugones: From Revolutionary Left to Radical Nationalism,” Alberto Spektorowski (1996)

“Argentine Nacionalismo before Perón: The Case of the Alianza de la Juventud Nacionalista, 1937–c. 1943,” Marcus Klein (2001)

BRAZIL

“Tenentismo in the Brazilian Revolution of 1930,” John D. Wirth (1964)

“Ação Integralista Brasileira: Fascism in Brazil, 1932–1938,” Stanley E. Hilton (1972)

“Integralism and the Brazilian Catholic Church,” Margaret Todaro Williams (1974)

“Ideology and Diplomacy: Italian Fascism and Brazil (1935–1938),” Ricardo Silva Seitenfus (1984)

“The corporatist thought in Miguel Reale: readings of Italian fascism in Brazilian integralismo,” João Fábio Bertonha (2013)

CHILE

“Corporatism and Functionalism in Modern Chilean Politics,” Paul W. Drake (1978)

“Nationalist Movements and Fascist Ideology in Chile,” Jean Grugel (1985)

“A Case of Non-European Fascism: Chilean National Socialism in the 1930s,” Mario Sznajder (1993)

CHINA

Revolutionary Nativism: Fascism and Culture in China, 1925–1937, Maggie Clinton (2017)

CROATIA

“An Authoritarian Parliament: The Croatian State Sabor of 1942,” Yeshayahu Jelinek (1980)

“The End of “Historical-Ideological Bedazzlement”: Cold War Politics and Émigré Croatian Separatist Violence, 1950–1980,” Mate Nikola Tokić (2012)

EGYPT

“An Interpretation of Nasserism,” Willard Range (1959)

Egypt’s Young Rebels: “Young Egypt,” 1933–1952, James P. Jankowski (1975)

“The Use of the Pharaonic Past in Modern Egyptian Nationalism,” Michael Wood (1998)

FRANCE

“Mores, “The First National Socialist”,” Robert F. Byrnes (1950)

“The Political Transition of Jacques Doriot,” Gilbert D. Allardyce (1966)

“National Socialism and Antisemitism: The Case of Maurice Barrès,” Zeev Sternhell (1973)

“Georges Valois and the Faisceau: The Making and Breaking of a Fascist,” Jules Levey (1973)

“The Condottieri of the Collaboration: Mouvement Social Révolutionnaire,” Bertram M. Gordon (1975)

“Myth and Violence: The Fascism of Julius Evola and Alain de Benoist,” Thomas Sheehan (1981)

GERMANY

“A German Racial Revolution?” Milan L. Hauner (1984)

“Abortion and Eugenics in Nazi Germany,” Henry P. David, Jochen Fleischhacker, and Charlotte Höhn (1988)

“Nietzschean Socialism — Left and Right, 1890–1933,” Steven E. Aschheim (1988)

The Brown Plague: Travels in Late Weimar and Early Nazi Germany, Daniel Guérin, tr. Robert Schwartzwald (1994)

“Hitler and the Uniqueness of Nazism,” Ian Kershaw (2004)

HAITI

“Ideology and Political Protest in Haiti, 1930–1946,” David Nicholls (1974)

“Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s State Against Nation: A Critique of the Totalitarian Paradigm,” Robert Fatton, Jr. (2013)

IRAN

“Iran’s Islamic Revolution in Comparative Perspective,” Said Amir Arjomand (1986)

IRAQ

“Arab-Kurdish Rivalries in Iraq,” Lettie M. Wenner (1963)

“From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State,” Cole Bunzel (2015)

“Iraqi Archives and the Failure of Saddam’s Worldview in 2003,” Samuel Helfont (2023)

ISRAEL

“The Emergence of the Israeli Radical Right,” Ehud Sprinzak (1989)

“Max Nordau, Liberalism and the New Jew,” George L. Mosse (1992)

The Stern Gang: Ideology, Politics and Terror, 1940–1949, Joseph Heller (1995)

““Hebrew” Culture: The Shared Foundations of Ratosh’s Ideology and Poetry,” Elliott Rabin (1999)

“Israel’s fascist sideshow takes center stage,” Natasha Roth-Rowland (2019)

“‘Frightening proportions’: On Meir Kahane’s assimilation doctrine,” Erik Magnusson (2021)

ITALY

“The Fascist Conception of Law,” H. Arthur Steiner (1936)

“The Goals of Italian Fascism,” Edward R. Tannenbaum (1969)

“Fascist Modernization in Italy: Traditional or Revolutionary?” Roland Sarti (1970)

“Fascism as Political Religion,” Emilio Gentile (1990)

“I redentori della vittoria: On Fiume’s Place in the Genealogy of Fascism,” Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht (1996)

JAPAN

“A New Look at the Problem of “Japanese Fascism”,” George M. Wilson (1968)

“Marxism and National Socialism in Taishō Japan: The Thought of Takabatake Motoyuki,” Germaine A. Hoston (1984)

“Fascism from Below? A Comparative Perspective on the Japanese Right, 1931–1936,” Gregory J. Kasza (1984)

“Japan’s Wartime Labor Policy: A Search for Method,” Ernest J. Notar (1985)

“Fascism from Above? Japan’s Kakushin Right in Comparative Perspective,” Gregory J. Kasza (2001)

PARAGUAY

“Political Aspects of the Paraguayan Revolution, 1936–1940,” Harris Gaylord Warren (1950)

“Toward a Weberian Characterization of the Stroessner Regime in Paraguay (1954–1989),” Marcial Antonio Riquelme (1994)

ROMANIA

“The Men of the Archangel,” Eugen Weber (1966)

“Breaking the Teeth of Time: Mythical Time and the “Terror of History” in the Rhetoric of the Legionary Movement in Interwar Romania,” Raul Carstocea (2015)

RUSSIA

“Was There a Russian Fascism? The Union of Russian People,” Hans Rogger (1964)

“The All-Russian Fascist Party,” Erwin Oberländer (1966)

“The Zhirinovsky Threat,” Jacob W. Kipp (1994)

Russian Fascism: Traditions, Tendencies, Movements, Stephen Shenfield (2000)

“Why fascists took over the Reichstag but have not captured the Kremlin: a comparison of Weimar Germany and post-Soviet Russia,” Steffen Kailitz and Andreas Umland (2017)

SLOVAKIA

“Storm-troopers in Slovakia: the Rodobrana and the Hlinka Guard,” Yeshayahu Jelinek (1971)

SPAIN

“The Forgotten Falangist: Ernesto Gimenez Cabellero,” Douglas W. Foard (1975)

Fascism in Spain, 1923–1977, Stanley Payne (1999)

“Spanish Fascism as a Political Religion (1931–1941),” Zira Box and Ismael Saz (2011)

SYRIA

The Ba‘th and the Creation of Modern Syria, David Roberts (1987)

TURKEY

“Kemalist Authoritarianism and fascist Trends in Turkey during the Interwar Period,” Fikret Adanïr (2001)

“The Other From Within: Pan-Turkist Mythmaking and the Expulsion of the Turkish Left,” Gregory A. Burris (2007)

“The Racist Critics of Atatürk and Kemalism, from the 1930s to the 1960s,” İlker Aytürk (2011)

UNITED KINGDOM

“Northern Ireland and British fascism in the inter-war years,” James Loughlin (1995)

“‘What’s the Big Idea?’: Oswald Mosley, the British Union of Fascists and Generic Fascism,” Gary Love (2007)

“Why Fascism? Sir Oswald Mosley and the Conception of the British Union of Fascists,” Matthew Worley (2011)

UNITED STATES

“Ezra Pound and American Fascism,” Victor C. Ferkiss (1955)

“Populist Influences on American Fascism,” Victor C. Ferkiss (1957)

“Vigilante Fascism: The Black Legion as an American Hybrid,” Peter H. Amann (1983)

“Silver Shirts in the Northwest: Politics, Personalities, and Prophecies in the 1930s,” Eckard V. Toy, Jr. (1989)

“Women in the 1920s’ Ku Klux Klan Movement,” Kathleen M. Blee (1991)

“‘Leaderless Resistance’,” Jeffrey Kaplan (1997)

“The post-war paths of occult national socialism: from Rockwell and Madole to Manson,” Jeffrey Kaplan (2001)

“The Upward Path: Palingenesis, Political Religion and the National Alliance,” Martin Durham (2004)

“The F Word: Is Donald Trump a fascist?” Dylan Matthews (2021)

“Castizo Futurism and the Contradictions of Multiracial White Nationalism,” Ben Lorber and Natalie Li (2022)

#this is not The Masterpost this has just emerged along the way#and there's definitely plenty that could go here that aren't bc i just got tired of listing them#i need somewhere and preferably multiple places to put sources so i feel like ive accomplished something when i finish reading them lol

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Oi, me ensina sobre o anarquismo?

O anarquismo é uma filosofia política que defende a abolição do Estado e outras formas de autoridade coercitiva, buscando uma sociedade baseada na cooperação voluntária, liberdade individual e igualdade. Os anarquistas acreditam que o poder e a hierarquia são intrinsecamente opressivos e que as pessoas devem ter o direito de governar suas próprias vidas.

Princípios fundamentais do anarquismo incluem:

Autonomia individual: Os anarquistas enfatizam a liberdade individual e a autonomia, acreditando que cada pessoa deve ter controle sobre suas próprias escolhas e ações.

Anti-autoritarismo: O anarquismo é contra todas as formas de autoridade coercitiva, incluindo o Estado, hierarquias sociais, instituições opressivas e sistemas de dominação.

Auto-organização e autogestão: Os anarquistas propõem a organização horizontal da sociedade, onde as pessoas se organizam em comunidades autônomas e tomam decisões de forma descentralizada, através de processos de tomada de decisão participativos.

Mutualismo e cooperação: O anarquismo valoriza a cooperação voluntária entre indivíduos e grupos, enfatizando a solidariedade, a ajuda mútua e a construção de relações baseadas no benefício mútuo.

Propriedade comum ou coletiva: Os anarquistas, em sua maioria, defendem formas de propriedade comum ou coletiva, onde os recursos e os meios de produção são controlados diretamente pelas comunidades e pelos trabalhadores.

É importante destacar que existem diferentes correntes dentro do anarquismo, cada uma com suas ênfases e abordagens específicas. Algumas das principais correntes incluem o anarco-comunismo, o anarco-sindicalismo, o mutualismo e o anarcofeminismo.

É interessante estudar as obras de teóricos anarquistas proeminentes, como Mikhail Bakunin, Piotr Kropotkin, Emma Goldman e Murray Bookchin, para compreender melhor as diferentes perspectivas dentro do anarquismo. Algumas das maiores obras anarquistas são:

"O Príncipe", de Piotr Kropotkin.

"A Conquista do Pão", de Piotr Kropotkin.

"Desobediência Civil", de Henry David Thoreau.

"A Sociedade contra o Estado", de Pierre Clastres.

"A Política do Obedecer", de Étienne de La Boétie.

"A Condição Humana", de Hannah Arendt.

"A Desobediência Civil e Outros Escritos", de John Rawls.

"Ação Direta", de Voltairine de Cleyre.

"O Anarquismo: Da Teoria à Prática", de Daniel Guérin.

"O Que É a Propriedade?", de Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

THREE BETWEEN THE SHEETS

ECSTASY (1984) - BLACK VENUS (1983) - MELODY OF PASSION (1985)

Indulge your ‘80s fantasies with two softcore classics produced by Harry Alan Towers (99 Women, Franco’s Count Dracula): In Black Venus, former Miss Bahamas Josephine Jacqueline Jones (Love Circles) leads a sumptuous orgy of Victorian lust co-starring Florence Guérin (Faceless), Karin Schubert (Black Emanuelle), Helga Liné (Black Candles) and Profumo Affair temptress Mandy Rice-Davies. Drive-in goddess Tiffany Bolling (The Candy Snatchers) stars in Ecstasy – also known as Love Scenes – as a Hollywood actress caught between reel passion and her own erotic hungers that include Britt Ekland, Julie Newmar, Monique Gabrielle and Jack Carter. As a Bonus, Austrian centerfold Sonja Martin (Red Heat, Emmanuelle IV) stars in Melody of Passion from director Hubert Frank (Vanessa), with all three features scanned in 2K from their original negatives.

ECSTASY (1984)

Label: Severin Films

Region Code: Region-Free

Rating: Unrated

Duration: 90 Minutes

Audio: English DTS-HD MA 2.0 Mono with Optional English Subtitles

Video: 1080p HD Widescreen (1.85:1)

Director: Bud Towsend

Cast: Franc Luz, Tiffany Bolling, Julie Newmar, Jack Carter, Britt Ekland, Daniel Pilon

In the Playboy Channel produced Ecstasy (1984) (aka Love Scenes) up and coming director Peter Binnes (Franc Luz, Ghost Town) has just won a critics choice award, and looking to cash-on this windfall her tries to get a new erotic thriller, penned by Belinda (Julie Newmar, Catwoman from the 60's Batman TV series!), into production, but his cigar-chompin' producer Sidney (Jack Carter, Alligator) says that no studio wants to finance an erotic film without some star power. Luckily Peter's wife Val (Tiffany Bolling, Kingdom of the Spiders) is a renowned actress, but she's never done nudity in film before. After some prompting from her hubby, as well as some reinforcement from a photographer friend Annie (Britt Ekland, The Wicker Man) she agrees to do the film, but with reservations.

Problems soon arise when the leading man in the erotic thriller, Rick (Daniel Pilon, Scanners III - The Takeover), who well-known for being a hand-on lothario ends up unexpectedly igniting Val's libido, and she embarssingly climaxes while film is rolling during their first filmed hook-up. This very real moment of passion exacerbates Val's mundane faked-orgasm sex life with her director-husband. Conflicted by her attraction to her co-star Val worries that her married life is on the rocks, but the self-obsessed Peter is too consumed with making his film to worry too much about his wife's concerns. This is a fun lightweight bit of softcore erotica that is heavy on the daytime soap opera drama vibes, but does feature some titillating softcore nudity, and it's capably directed by Bus Townsend (Nightmare In Wax). The film is less tawdry that I would have liked, and is lousy with sax-heavy score, but plenty entertaining, and getting an eyefull of drive-in goddess Tiffany Bolling (Candy Snatchers, Bonnie's Kids) nude is always a pleasure, and both Ekland and Newmar seem to be having a blast in their non-nude roles,

Special Features:

- Trailer (50 sec)

BLACK VENUS (1983)

Label: Severin Films

Region Code: Region-Free

Rating: Unrated

Duration: 95 Minutes

Audio: English, French, German DTS-HD MA 2.0 Mono with Optional English Subtitles

Video: 1080p HD Widescreen (1.66:1)

Director: Claude Mulot

Cast: José Antonio Ceinos, Josephine Jacqueline Jones, Florence Guérin, Emiliano Redondo

Another Playboy Channel produced slice of erotica, Black Venus (1984) directed by Claude Mulot (The Blood Rose), is a Victorian era set erotic film that begins with penniless sculptor Armand (José Antonio Ceinos, Leonor) meeting the gorgeouse Venus (Josephine Jacqueline Jones, Christina). Entranced by her beauty she becomes his muse and lover, and he sets about sculpting a statue of her likeness. With no source of income from his artwork Venus begins working as a model at a fashion house, but the attention she draws and the money she makes proves to be a blow to his ego, he drowns his sorrows in drinks, and Venus ends up leaving him, embarking on sexual adventures with a horny wealthy couple, but growing tired of being exploited by others, she teams-up with Louise (Florence Guérin, Faceless) to work at a brothel, until Armand, no longer tortured, returns to reclaim his muse.

Black Venus has some solid period set production value, conjuring the Victorian era convincingly for a low-budget film, it's attractively lensed, and is well-acted, not to mention chock full of nudity and actual erotic scenes that are a turn on. This one also has a bookend scenes of an older gent (Emiliano Redondo, The People Who Own The Dark), who is turned on by being a voyeur, touring a brothel down a secret hallway that allows him to peep through two-way mirrors to witness the sexy cosplay shenanigans happening inside themed rooms where people indulge in fantasies involving pirates, slaves, and kings.

Special Features:

- Trailer

MELODY OF PASSION (1985)

Label: Severin Films

Region Code: Region-Free

Rating: Unrated

Duration: 91 Minutes

Audio: English or German DTS-HD MA 2.0 Mono with Optional English Subtitles

Video: 1080p HD Widescreen (1.66:1)

Director: Hubert Frank

Cast: Sonja Martin, Montse Bayo, Marina Oroza, Klaus Münster, Martin Garrido

The final titillating softcore delight is Hubert Frank's Melody of Passion (aka La chica que cayó del Cielo) German gal Betty (Sonja Martin, Emmanuelle IV) is notified that she has inherited a family castle in Spain. Arriving there she finds the castle and learns from the lawyer handling the estate, Don Cervantes, that it might be haunted and more trouble than it's worth, and insists that she should sell it to him sight unseen. Now this guy has reasons for wanting the castle, in that he is partnered with a madame and they are running a profitable high-class brothel within it's stone walls!

This is certainly the most offbeat of the bunch this Austrian-Spanish co-production throws a little bit of everything into the mix. We get the expected softcore delights, plentiful nudity, some nice atmosphere, plus a robbery, high-speed car chase, Gothic horror elements and quite a bit more. The tone is uneven to say the least but the unexpected camp-factor and exploitation entertainment quotients are through the roof, making this wild slice of Euro-rotica the best of the bunch in my estimation.

Audio/Video: All three films make their North American Blu-ray debuts from Severin Films on region-Free Blu-ray presented in 1080p HD widescreen. Both Black Venus and Melody of Passion are framed in 1.66:1 while Ecstasy gets 1.85:1. These are advertised as being scanned in 2K from the original negatives, and they look pretty terrific. Film grain is unmolested and organic, colors and skin tones look natural throughout. Audi comes by way of uncompressed DTS-HD MA Mono with optional English subtitles. Ecstasy gets uncompressed English while Melody of Passions has both German and English audio options, with Black Venus sporting English, German, and French audio options. All the tracks are clean and free of issues, a bit limited in range, but clean and well-balanced. Extras are anemic, we only get trailers for Black Venus and Ecstasy, so that is a disappointing, I would have loved commentary tracks on these, but the HD upgrades are appreciated and blow away the previous DVD editions. The three disc release arrives in a black keepcase with a single sides sleeve of artwork, inside a flipper tray houses the three films on separate discs with separate artworks.

If you're looking to indulge in some vintage ‘80s softcore fantasies Severin has you covered with this titillating triple-threat collection. The extras are slim but the A/V is wonderful, and the erotic delights are plentiful. The three films are handsomely produced for what they are and look fantastic in HD. The films range from horny melodrama, to sleazy Victorian debauchery, and bonkers 80's raunchiness - it's a wonderful assortment of vintage erotica that all lovers of softcore should have on their shelf.

http://mcbastardsmausoleum.blogspot.com/2023/04/three-between-sheets-severin-films-blu.html?m=1

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

They don't know about the 30 years relationship between reactionary actor alain delon and anarchist gay militant Daniel guérin ...

1 note

·

View note

Link

Author: Daniel GuérinTitle: Proudhon In the ClosetSubtitle: The homophobia and misogyny of Pierre-Joseph ProudhonDate: Originally written in 1969 & translated in 2013.Notes: Translated by Jesse Cohn. A reinterpretation of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s well-known misogyny as a symptom of repressed homosexual desires. Daniel Guérin (1904–1988), was also author of Homosexualité et révolution (1953) and the widely read Anarchism: From Theory to Practice (1965/1970).Source: Originally published in French in Essai Sur La Révolution Sexuelle (Après Reich Et Kinsey) by Daniel Guerin in 1969, published in Paris by Editions Pierre Belfond. See the English translation word document with the original French here: . This English translation was published by Bastard Press in 2014: Pierre-Jospeh Proudhon is best known as the anarchist who exclaimed Property is theft!, and the first anarchist to fall foul of Marx and Engels’ tendency to viscously turn on those who who refuse to submit to their authority. He is less well known as a misogynist, and even less so as a venomous homophobe. Here Daniel Guerin analyses Proudhon’s misogyny and homophobia and the raging contradictions brought about by his hatred and the paradoxical consequences this has on Proudhon’s anarchism. Guerin’s research reveals a complex and conflicting emotional relationship with men and masculinity, and consequently women and the feminine, in Proudhon’s life. Jesse Cohn’s easy-to-read translation is the first into English since the essay was written in 1969. Daniel Guerin (1904–1988) was a leading figure of the French New Left, and authored dozens of books on Capitalism, Fascism, Socialism, Marxism and Anarchism. He was an early advocate of gay rights in the New Left, which saw him ostracised from much French leftist publishing houses. His best known works in English are perhaps Anarchism and Anarchism: From Theory to Practice. I would like to consider one of the least known aspects of the work of the great social reformer: his keen and unusual curiosity with regard to homosexuality.[1] A curiosity all the more surprising since he passed, quite rightly, for a man of rigid mores – a man, moreover, who had authored the posthumous Pornocratie, who was wont to thunder against the deviations of the flesh. Proudhon claimed to observe that the homosexuality of his time was hardly practiced by the working classes. Its practitioners, according to him, were rather “refined types, artists, men of letters, magistrates, priests.” Why? because workers were “not sufficiently advanced in the worship of the ideal.” For him, unisexual love was “an error of judgment produced by an illusion of the ideal,” the pursuit of “the beautiful and the good.” What struck him concerning ancient mores was that “great poets came to celebrate this monstrous ardor – the privilege, according to them, of gods and heroes”. He added that it was this “poetic” of homosexuality that really had to be explained. And excusing himself in advance for the audacity of his incursion into such a field, he dared to write: “I have consulted written testimonies; I have queried those ancients who were able to express it in poetry and philosophy everywhere, and who, speaking to a society accustomed to Socratic manners, were hardly obstructed from doing so […] what I will say […] will have […] the advantage of singularly reducing the crimes of those who comprised its first singers and panegyrists […] We have pleaded in favor of a few persons, the greatest to have illuminated our race, in favor of Greek poetry and philosophy, the eternal honor of the human spirit, the innocence of unisexual love.” Proudhon opens his study by deliberately rejecting the explanation of Saint Paul “who believes to have explained everything when he attributes the phenomenon with which we are concerned to the worship of false gods.” For him, “Saint Paul’s explanation does not explain anything.” It was too convenient for Christianity to charge polytheism and the society based on it with behaviors that it wanted to purge from the earth. “But […] Christianity did not succeed in its enterprise” and the passions denounced by the apostle “remained in the Church of Christ.” Returning to the origins of Greek love, Proudhon suggests, with reason, that homosexuality had existed in Greece well before Socrates. It is in Ionia that this love initially “was sung and divinized.” Earlier, the Syrians, the Babylonians, and other Eastern religions had made homosexuality one of their mysteries. At the origin of humanity, an “erotic pantheism” reigned, one which Charles Fourier, to whom Proudhon owed so much, called omnigamy and which Proudhon evokes in these terms: “This supreme love, which cleared up the chaos and which animates all the beings, does not need, to enjoy, of the human form. For him, the reigns, the kinds, the species, the sexes, all is confused […] It is Cénis, changed girl into a boy; Hermaphrodite, at the same time male and female; Protée, with its thousand metamorphoses […] Théocrite goes further: in a lament on the death of Adonis, it claims that the wild boar which killed it out of a blow of hook was guilty only of awkwardness. The poor animal wanted to give a kiss to this beautiful young man: in the transport of its passion it tore it! ” When humanity, exit of chaos, entered civilization, this erotic pantheism was moulted in “erotic idealism”: “Above all, the old ones thought, the man cannot live without love; without love the life is an anticipation of death. Antiquity is full with this idea; it sang and recommended the love; it disputed as far as the eye can see its nature like it disputed of the Bien sovereign, and more once it was able to him to confuse them. With the same power that its artists idealized the human form, its philosophers and its poets idealized the Love […] It was […] among them, with which would discover and carry out the perfect love […] But this ideality of the love, where to find it? How to enjoy it, and up to what point?” ...

0 notes

Text

Mai MMXXIV

Films

Les Trois Jours du Condor (Three Days of the Condor) (1975) de Sydney Pollack avec Robert Redford, Faye Dunaway, Cliff Robertson, Max von Sydow, John Houseman, Addison Powell, Walter McGinn et Tina Chen

La Loi du silence (I Confess) (1953) d'Alfred Hitchcock avec Montgomery Clift, Anne Baxter, Karl Malden, Brian Aherne, Roger Dann, Charles Andre, O.E. Hasse et Dolly Haas

Bon Voyage (2003) de Jean-Paul Rappeneau avec Isabelle Adjani, Virginie Ledoyen, Yvan Attal, Grégori Derangère, Gérard Depardieu, Peter Coyote, Jean-Marc Stehlé et Aurore Clément

Complot de famille (Family Plot) (1976) d'Alfred Hitchcock avec Bruce Dern, William Devane, Barbara Harris, Karen Black, Ed Lauter, Cathleen Nesbitt et Katherine Helmond

Elvis: That's the Way It Is (1970) de Denis Sanders avec Elvis Presley, Richard Davis, Sammy Davis, Jr, Joe Esposito, Felton Jarvis et Red West

Reivers (The Reivers) (1969) de Mark Rydell avec Steve McQueen, Sharon Farrell, Will Geer, Rupert Crosse, Mitch Vogel, Juano Hernández, Michael Constantine, Burgess Meredith et Diane Ladd

La Belle Espionne (Sea Devils) (1953) de Raoul Walsh avec Yvonne De Carlo, Rock Hudson, Maxwell Reed, Denis O'Dea, Michael Goodliffe, Bryan Forbes, Jacques Brunius et Gérard Oury

L'assassin habite au 21 (1942) de Henri-Georges Clouzot avec Pierre Fresnay, Suzy Delair, Jean Tissier, Pierre Larquey, Noël Roquevert, Odette Talazac, Marc Natol et Louis Florencie

Une aussi longue absence (1961) de Henri Colpi avec Alida Valli, Georges Wilson, Charles Blavette, Amédée, Jacques Harden, Paul Faivre, Catherine Fonteney et Diane Lepvrier

Le Procès Goldman (2023) de Cédric Kahn avec Arieh Worthalter, Arthur Harari, Stéphan Guérin-Tillié, Nicolas Briançon, René Garaud, Aurélien Chaussade, Christian Mazucchini, Jeremy Lewin, Jerzy Radziwiłowicz et Chloé Lecerf

La Vendetta (1962) de Jean Chérasse avec Louis de Funès, Francis Blanche, Marisa Merlini, Olivier Hussenot, Jean Lefebvre, Rosy Varte, Jean Houbé et Christian Mery

Messieurs les Ronds de Cuir (1978) de et avec Daniel Ceccaldi et Claude Dauphin, Raymond Pellegrin, Evelyne Buyle, Roger Carel, Roland Armontel, Bernard Le Coq, Jean-Marc Thibault et Michel Robin

Marcello mio (2024) de Christophe Honoré avec Chiara Mastroianni, Catherine Deneuve, Nicole Garcia, Fabrice Luchini, Benjamin Biolay et Melvil Poupaud

Opération Opium (Poppies Are Also Flowers) (1966) de Terence Young avec E. G. Marshall, Trevor Howard, Angie Dickinson, Gilbert Roland, Yul Brynner, Eli Wallach, Georges Géret, Marcello Mastroianni et Anthony Quayle

Viva Maria ! (1965) de Louis Malle avec Brigitte Bardot, Jeanne Moreau, Paulette Dubost, George Hamilton, Claudio Brook, Carlos López Moctezuma et Gregor von Rezzori

Séries

Kaamelott Livre V

Le Phare

Maguy Saison 4

Retour de France - Retour à l'occase départ - Rimes et châtiment - Fugue en elle mineure - Mise aux poings - Vote voltige - St Vincent de Pierre - Courant d'hertz - Un médium et une femme - Retrouvailles, que vaille ! - Parrain artificiel - Infarctus et coutumes - Soupçons et lumières - Dakar, pas Dakar - Impair Noël - Maguy Antoinette - Otages dans le potage - Piqûres de mystique - Nécropole et Virginie - Nitro, ni trop peu - Assassin-glinglin - Le nippon des soupirs - Pas de deux en mêlée - Main basse sur Bretteville - Ski m'aime me suive - Des plaies et des brosses - Polar ménager - Une faim de look - Le bronzage de Pierre - Transport-à porte - En chantier de vous connaître - La fête défaite - Câblé en herbe - L'enjeu de la vérité - Déformation permanente - En deux tanks, trois mouvements - Postes à galère - Prince-moi, je rêve - Science friction - Démission impossible - Lis tes ratures ! - L'infâme de lettres

Affaires sensibles

Apollo 13 : Les naufragés de l’espace - La vraie arrestation du faux Xavier Dupont de Ligonnès - L'assaut sur le Capitole - Trésor de Lava : embrouilles corses - Secte, clonage et soucoupes volantes : voyage aux frontières du Raël - Ils ont enlevé Fangio ! - Guerre du Golfe et fake news - "The Crown", une série royale ou la royauté selon Netflix - La catastrophe de Beaune - Concorde, la Lune et l'ovni - USA-URSS 1972, Guerre Froide sur parquet - Amityville : 28 jours avec le diable - L'affaire Athanor - Coupe du monde 1966, les Nord-Coréens sortent du vestiaire - La véritable histoire de Rabbi Jacob

Coffre à Catch

#155 : Les débuts historiques de Sheamus ! - Hors-série : WWE One Night Stand 2007 - #51 : Randy Orton ≥ Charles Ingalls - #50 : Tommy Dreamer, représentant Decathlon et Jean-Louis David - #52 : Lashley Récupère son Titre ! - #53 : RIP Vince McMahon - #54 : Qui a fait exploser la bagnole de Vince ? - #55 : JOHN CENA EST DANS LA CE-PLA ! - #56 : Le Poison du Catch vu par CM Punk & John Morrison - Hors-série : ECW December to Dismember - #166 : William Regal : un maître du micro !" - #167: Buckle up, Teddy: Chris Agius nous parle de Backlash 2024 ! - #168 : L'épisode des 1000 likes + Tony Atlas" - #169 : Tiffany est de retour et William Regal est fabuleux!

La croisière s'amuse Saison 5

Merci, je ne joue plus - Le Parfait Ex-amour - Enfin libre - L'amour n'est pas interdit - L'amour n'est pas la guerre - La Fête en bateau : première partie - La Fête en bateau : deuxième partie - Une expérience inoubliable : première partie - L'Amour de ses rêves - Les Victimes - Vive papa ! - L'Amour programmé - Ça, c'est une fête ! - Que dire de l'amour ?

The Hour Saison 1

Une heure, une équipe - Une heure de vérité - Une heure, une tentation - Une heure sous haute tension - L'heure de la révolte - Une heure qui change tout

Castle Saison 5, 6

Le Facteur humain - Jeu de dupes - Valkyrie - Secret défense - Pas de bol, y a école ! - Sa plus grande fan - L'avenir nous le dira - Tout un symbole - Tel père, telle fille - Le meurtre est éternel - L'Élève et le Maître - Le Bon, la Brute et le Bébé

Commissaire Moulin Saison 1

Choc en retour - L'Évadé - Marée basse

Totally Spies! Saison 5, 6, 7

Totally Mystère ! - Totalement Versailles : première partie - Totalement Versailles : deuxième partie - Pandapocalypse - Quand c'est trop, c'est Troll !

Meurtres au paradis Saison 13

Face à face - Le troisième passager

Doctor Who Season 1

Space Babies - The Devil's Chord - Boom - 73 Yards

Commissaire Dupin

Le trésor d'Ys

Spectacles

WWE Backlash France (2024) à la LDLC Arena de Lyon-Décines

Chocolat Show ! (2007) avec Olivia Ruiz

Les Faux British (2024) de Henry Lewis et Henry Shields avec Francis Huster, Cristiana Reali, Gwen Aduh, Aurélie de Cazanove, Renaud Castel, Lionel Laget, Jean-Marie Lecoq et Miren Pradier

Jamiroquai : Live in Verona (2002)

David Bowie : Glass Spider Tour (1987)

Livres

Détective Conan, tome 22 de Gôshô Aoyama

Dis-moi ton fantasme de Léa Celle qui aimait

Kaamelott, tome 5 : Le Serpent Géant du Lac de l'Ombre d'Alexandre Astier, Steven Dupré et Benoît Bekaert

Une enquête du commissaire Dupin : Péril en mer d'Iroise de Jean-Luc Bannalec

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

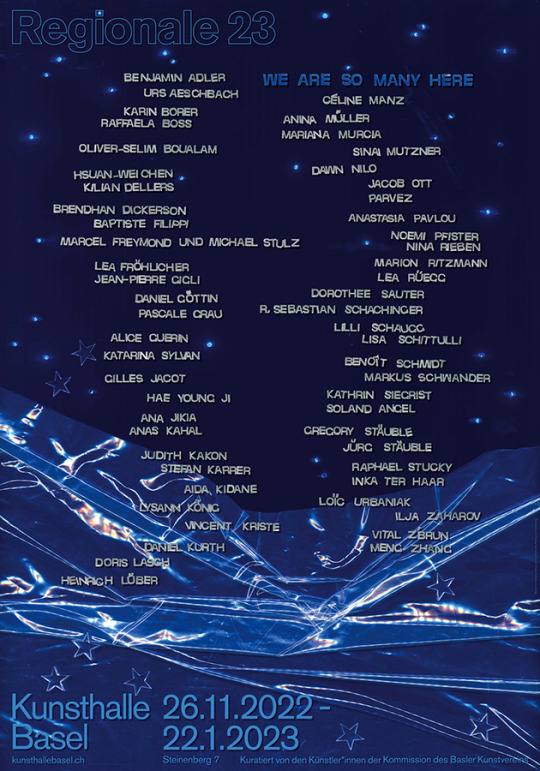

Under the title We are so many here, the artists of the association board of the Basler Kunstverein exceptionally curate this year’s Regionale at Kunsthalle Basel. On the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Kunsthalle Basel, more than 50 artists will be brought together in a polyphonic, colorful, and resonant presentation. Kunsthalle Basel was founded in 1872 by artists for artists, among others, as a place of exchange, critical debate, and friendship, to “establish a site for visual arts,” as declared when its foundation stone was laid. In addition to its legendary exhibition spaces, Kunsthalle Basel also houses other cultural institutions under its roof, as well as the renowned Restaurant Kunsthalle. To mark its 150th birthday, Kunsthalle Basel is to be experienced in all its facets and taken over by artists in a playful and celebratory way—not to look at the past nostalgically, but to continue writing history afresh.

With Benjamin Tiberius Adler, Urs Aeschbach, Karin Borer, Raffaela Boss, Oliver-Selim Boualam, Hsuan-wei Chen, Kilian Dellers, Brendhan Dickerson, Baptiste Filippi and Loïc Urbaniak, Marcel Freymond and Michael Stulz, Lea Fröhlicher, Jean-Pierre Gigli, Daniel Göttin, Pascale Grau, Alice Guérin, Gilles Jacot, Hae Young Ji, Ana Jikia, Anas Kahal, Judith Kakon, Stefan Karrer, Aida Kidane, Lysann König, Vincent Kriste, Daniel Kurth, Doris Lasch, Heinrich Lüber, Céline Manz, Anina Müller, Mariana Murcia, Sinai Mutzner, Dawn Nilo, Jacob Ott, Parvez, Anastasia Pavlou, Noemi Pfister, Nina Rieben, Marion Ritzmann, Lea Rüegg, Dorothee Sauter, R. Sebastian Schachinger, Lilli Schaugg, Lisa Schittulli, Benoît Schmidt, Markus Schwander, Kathrin Siegrist, SOLAND ANGEL, Gregory Stäuble, Jürg Stäuble, Raphael Stucky, Katarina Sylvan, Inka ter Haar, Ilja Zaharov, Vital Z’Brun, Meng Zhang

We are so many here is part of the Regionale 23 and is curated on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Kunsthalle Basel by Rut Himmelsbach, Cécile Hummel, Sophie Jung, Edit Oderbolz, Hannah Weinberger, and Johannes Willi, current and former artist members of the association board of the Basler Kunstverein.

0 notes

Text

favorite color: bright red

currently reading: daniel guérin anthology

last song: feldobom a követ carson coma

last movie: the guy ritchie sherlock holmes movie

last series: rewatched tatort saarbrücken w zez

sweet, savoury or spicy: listen i have post covid syndrome u cannot be asking me this

craving: ugh sára now i want pho too!! but also some good fried rice...

tea or coffee? hot? iced?: i cant drink either for medical reasons

currently working on: oh so many things. a giant milipede crochet pattern, linoprinting some patches, an article about mark davis' moveset, hakama pants for my sister, dying some stuff and def more things im forgetting about

tagging uhhh @robyn-goodfellowe @vassyflorence @the-hiddenblade

GET TO KNOW ME

tagged by @dragongirl180

Favourite Colour: nectar yellow

Currently Reading: The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains by Thomas W. Laqueur

Last Song: Outside Today - YoungBoy Never Broke Again

Last Movie: Fourteen Days in May (1987)

Last Series: All or Nothing: Toronto Maple Leafs

Sweet, Savoury, Spicy: I’ve got the worst sweet tooth known to man

Craving: BBQ

Tea or Coffee? Hot? Iced?: Coffee, hot, black

Currently Working On: a Sid/Geno ghost story I haven’t updated in weeks. Also an Eichel / McDavid edit. Which is to say: currently not working on any of the uni stuff I should be doing

tagging: @cinnamoncowboy

59 notes

·

View notes

Quote