#DSM-III-R

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Masochistic / Self-Defeating Personality Disorder (Ma/SDPD)

Note: You cannot be diagnosed with this disorder, as it's not in any diagnostic manual; you would be diagnosed with Other Specified Personality Disorder instead.

Criteria from the DSM-III-R (1987):

A. A pervasive pattern of self-defeating behavior, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts. The person may often avoid or undermine pleasurable experiences, be drawn to situations or relationships in which he or she will suffer, and prevent others from helping him or her, as indicated by at least five of the following:

chooses people and situations that lead to disappointment, failure, or mistreatment even when better options are clearly available

rejects or renders ineffective the attempts of others to help him or her

following positive personal events (e.g., new achievement), responds with depression, guilt, or a behavior that produces pain (e.g., an accident)

incites angry or rejecting responses from others and then feels hurt, defeated, or humiliated (e.g., makes fun of spouse in public, provoking an angry retort, then feels devastated)

rejects opportunities for pleasure, or is reluctant to acknowledge enjoying himself or herself (despite having adequate social skills and the capacity for pleasure)

fails to accomplish tasks crucial to his or her personal objectives despite demonstrated ability to do so, e.g., helps fellow students write papers, but is unable to write his or her own

is uninterested in or rejects people who consistently treat him or her well, e.g., is unattracted to caring sexual partners

engages in excessive self-sacrifice that is unsolicited by the intended recipients of the sacrifice

B. The behaviors in A do not occur exclusively in response to, or in anticipation of, being physically, sexually, or psychologically abused.

C. The behaviors in A do not occur only when the person is depressed.

Millon's subtypes:

(Millon, ed.).

About Ma/SDPD

Ma/SDPD is similar to avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive, depressive / melancholic, negativistic / passive-aggressive and borderline PDs. It's part of what Millon & Bloom term the "Compliant Personality Patterns", along with OCPD, DPD & HPD.

Differential diagnoses include ongoing abuse, anxiety disorders, somatic disorders, and mood disorders.

The most common PD comorbidities with Ma/SDPD are AsPD (22.17%), Depressive / Melancholic PD (16.74%), & SzPD (12.22%). The least common was HPD (4.07%). Less than 8 percent (7.24%) had only ("pure") Ma/SDPD [much higher than those who had pure Negativistic / Passive-Aggressive, Depressive / Melancholic and Sadistic PDs] (Millon & Bloom).

Millon defines it on a spectrum from aggrieved -> masochistic (self-defeating) (Millon Personality Group); or alternatively from abused [personality type] -> aggrieved [style] -> self-defeating [disorder] (Millon). It also exists on a spectrum from self-sacrificing -> yielding -> masochistic (Millon, ed.).

Originally called masochistic PD, the name was changed to self-defeating PD in the DSM-III-R "to avoid the historic association of the term masochistic with older psychoanalytic views of female sexuality and the implication that a person with the disorder derives unconscious pleasure from suffering" (DSM-III-R). However, Millon & Bloom write that the specific name chosen is pointless, because "all personality disorders are “self-defeating.”"

Childhood trauma is a predisposing factor (DSM-III-R).

Herman argues that Ma/SDPD is a misdiagnosis of Complex PTSD, due to victim blaming and sexism (she also argues the same for Dependent and Histrionic PDs).

In the DSM-III-R it was described as being characterised by “ubiquitous self-defeating behavior such as repeatedly entering into unsatisfying and hurtful relationships, avoiding opportunities for pleasure, rejecting relationships with seemingly caring people, and repeatedly rendering ineffective reasonable efforts by others to help the person" (Coolidge & Segal).

Ma/SDPD "is a mixing or confusion of the usual pleasure-seeking drive with the pain avoidance. As a result, these individuals appear to create personal and social discomfort in their lives. Although it is often reported that they seem to feel comfortable only with guilt and shame, they are also believed to use their self-deprecation as a social strategy to gain support from others" (Millon & Bloom).

In Ma/SDPD, "the individual experiences what is emotionally painful as a means of fulfilling his or her survival aims" (Millon, ed.).

Ma/SDPD only ever appeared in the appendix of the DSM-III-R, and it was dropped because it was associated with 'feminine sexual submissiveness' (Millon, ed.).

References

Coolidge, Frederick L., & Segal, Daniel L., ‘Evolution of Personality Disorder Diagnoses in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’, Clinical Psychology Review, 1998, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 585-599.

Herman, Judith Lewis, Trauma and Recovery, 2015.

Millon, Theodore, & Bloom, Caryl, The Millon Inventories, 2008.

Millon, Theodore, Disorders of Personality, 2011.

Millon, Theodore, ed., Personality Disorders in Modern Life, 2004.

'Aggrieved / Masochistic Personality', Millon Personality Group, 2015, https://www.millonpersonality.com/theory/diagnostic-taxonomy/masochistic.htm.

#masochistic personality disorder#self defeating personality disorder#self-defeating personality disorder#other specified personality disorder#ospd#personality disorders#pd info#long post#dogpost#dsm-iii-r#dsm iii r#dsm-iii#dsm iii#described#described in alt text

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some fact checks about plurality

The "Bible of psychiatry" is the DSM. In 1994, the DSM changed the name of Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD) to Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID). This was in response to a moral panic where critics claimed that the condition was fake.

The original and current diagnostic criteria do not require trauma for DID (or MPD) (DSM-III, p. 259; DSM-III-R, p. 272; DSM-5-TR, p. 331).

The international counterpart of the DSM is the ICD-11. Its essential features for DID do not require trauma, either.

Both books say that not all cases of multiple personalities are a disorder or a severe impairment. Psychiatry recognizes that medicalizing them is not always appropriate.

Plurality (or multiplicity) is a community umbrella term for many ways of being more than one person in a body. Psychiatrists who know enough about DID are aware of it. Plurality includes but is not the same as DID.

The community has always included plurals who formed for reasons other than trauma. Dividing the community by excluding non-traumagenic plurals and calling them fake is new. That only started in August 2014 on Tumblr, unheard of elsewhere.

When that started, a trauma-caused DID system created the word "endogenic." This means plurals who formed naturally rather than from trauma. The Lunastus Collective coined it in solidarity with them.

(Similarly, the coiner of another umbrella term, "alterhuman," is a member of a traumagenic OSDD system who supports endogenic plurals. The purpose of that word is for plural systems to unite with other sorts who differ from usual definitions of human individual, valuing what we do and do not have in common, instead of in-fighting about who is more legitimate.)

Community historian LB Lee gives several good reasons why-- as trauma-surviving plurals-- they choose not to call themselves "traumagenic" or divide the community by origins. If I may briefly paraphrase a couple of these: If you see suffering as your whole foundation of who you are, then you have a more difficult time envisioning a better situation. If you want others to respect you, a losing strategy is to put down people who are seen as similar to you.

Neither psychiatry nor the greater community of plurals see trauma history as an important distinction in determining whether someone is plural.

#plurality#PluralGang#DID OSDD#sysblr#endogenic#traumagenic#plural community#endo safe#traumagenic safe#alterhuman#SysCourse#plural#OSDD#DID#dissociative identity disorder#multiplicity#rated G#screen reader friendly#psychiatry#trauma#about words#I've been meaning to make this post for months; it is not a response to whatever the latest plural quarrel is.#if you don't want to see posts like this from me i always tag thoroughly so you can just blacklist a selection of the tags in your settings

682 notes

·

View notes

Note

i think you do a really impressive job balancing comprehensive/concise while referencing a lot of complex frameworks(contexts? schools of thought? lol idk what to call that. big brain ideas) but if you have any readings specifically on the institution of psychiatry topic that you would recommend/think are relevant, I'd be interested. it's absolutely not a conversation that's being had enough and I want to be able to articulate myself around it

yes i have readings >:)

first of all, the anti-psychiatry bibliography and resource guide is a great place to start getting oriented in this literature. it's split by sub-topic, and there are paragraphs interspersed throughout that give summaries of major thinkers' positions and short intros to key texts.

it's from 1979, though, so here are some recs from the last 4 decades:

overview critiques

mind fixers: psychiatry's troubled search for the biology of mental illness, by anne harrington

psychiatric hegemony: a marxist theory of mental illness, by bruce m z cohen

desperate remedies: psychiatry's turbulent quest to cure mental illness, by andrew scull

psychiatry and its discontents, by andrew scull

madness is civilization: when the diagnosis was social, 1948–1980, by michael e staub

contesting psychiatry: social movements in mental health, by nick crossley

the dsm & pharmacy

dsm: a history of psychiatry's bible, by allan v horwitz

the dsm-5 in perspective: philosophical reflections on the psychiatric babel, by steeves demazeux & patrick singy

pharmageddon, by david healy

pillaged: psychiatric medications and suicide risk, by ronald w maris

the making of dsm-iii: a diagnostic manual's conquest of american psychiatry, by hannah s decker

the myth of the chemical cure: a critique of psychiatric drug treatment, by joanna moncrieff

the book of woe: the dsm and the unmaking of psychiatry, by gary greenberg

prozac on the couch: prescribing gender in the era of wonder drugs, by jonathan metzl

the creation of psychopharmacology, by david healy

the bitterest pills: the troubling story of antipsychotic drugs, by joanna moncrieff

psychiatry & race

the protest psychosis: how schizophrenia became a black disease, by jonathan metzl

administrations of lunacy: racism and the haunting of american psychiatry at the milledgeville asylum, by mab segrest

the peculiar institution and the making of modern psychiatry, 1840–1880, by wendy gonaver

what's wrong with the poor? psychiatry, race, and the war on poverty, by mical raz

national and cross-national contexts

mad by the millions: mental disorders and the early years of the world health organization, by harry yi-jui wu

psychiatry and empire, by sloan mahone & megan vaughan

ʿaṣfūriyyeh: a history of madness, modernity, and war in the middle east, by joelle m abi-rached

surfacing up: psychiatry and social order in colonial zimbabwe, 1908–1968, by lynette jackson

the british anti-psychiatrists: from institutional psychiatry to the counter-culture, 1960–1971, by oisín wall

crime, madness, and politics in modern france: the medical concept of national decline, by robert a nye

reasoning against madness: psychiatry and the state in rio de janeiro, 1830–1944, by manuella meyer

colonial madness: psychiatry in french north africa, by richard keller

madhouse: psychiatry and politics in cuban history, by jennifer lynn lambe

depression in japan: psychiatric cures for a society in distress, by junko kitanaka

inheriting madness: professionalization and psychiatric knowledge in 19th century france, by ian r dowbiggin

mad in america: bad science, bad medicine, and the enduring mistreatment of the mentally ill, by robert whitaker

#sorry this is SO MANY things lmao#i wld recommend starting with harrington or scull as an intro and then maybe look at one of the more topic-specific texts#depending on what interests you specifically#book recs#psychiatry

617 notes

·

View notes

Text

And Alexander Wept for Hephaistion....

If you don’t mind, I wanted to ask, you said something along the lines of: by the time Alexander was coming closer to his death, he had recovered from the grief of Hephaistion’s death (if I’m remembering this correctly; I’m so sorry I have a fuzzy memory) how long do you think he mourned Hephaistion?

------------------

This was an ask via message, so putting it here to reply publicly, as it may be of interest to others.

First, however, I want to mention a pair of articles I wrote many years ago now, but which are still valid:

“The Mourning of Alexander the Great,” Syllecta Classica 12 (2001), 98-145.

“Some New Thoughts on the Death of Alexander the Great,” with Eugene N. Borza (lead author), The Ancient World 31.1 (2000), 1-9. (I wrote the last 1/3 of it.)

The first, in particular, is an in-depth analysis of Alexander’s behavior after Hephaistion died. I’m still rather proud of it, as it brings together two quite diverse fields: bereavement + Alexander studies. If I had a critique for it now, it’s that I didn’t analyze the stories inherent in the primary sources, but that also wasn’t my intention in writing it. I specifically say that I do not plan to pick apart which reports of Alexander’s behavior are likely authentic and which aren’t. My goal was to evaluate all of them in terms of possible evidence of pathological bereavement, according to the (then) DSM III-R (et al.).

TL;DR version of the article: Alexander’s mourning was NORMAL and followed recognized patterns, if one allows for the loss of someone extremely close, a spouse/similar.

Yes, there were complicating factors. BUT he did not go crazy with grief.

Unfortunately, this article is far less known than the “An Atypical Affair” article on Alexander and Hephaistion’s relationship. That’s too bad, as the “His grieving was extreme!” persists among even some of my colleagues, never mind those outside the field of Macedoniasts. (It’s also admittedly possible that they were simply unconvinced by my arguments, but in that case, one usually cites and says so.)

If I could put a giant blinking neon light on one of my earlier articles to get it more attention, that would be the one I’d point to.

The second article—or my 1/3rd of it anyway—deals with the possible effects of deep mourning on the immune system of adult males of Alexander’s age group. Yes, according to some limited research, it does have an impact that increases susceptibility to infectious disease. Add his poor overall physical health after all those battles (and Macedonian-style symposial drinking), and he was just too spent to fight off the typhoid or malaria or whatever fever disease got him.

Ergo, he died roughly 8 months after Hephaistion. We don’t have a date for the latter’s death, but sometime in October or November of 324 BCE is the window. Alexander died June 10th, 323 … or possibly a day or so later if he were in a paralysis too deep for his breathing to be ascertained. (As per Gene’s part of the article.)

The dating is important, as it affects where he (probably) was in his mourning process.

Mourning follows a somewhat predictable pattern, and one of the biggest mistakes made by those unfamiliar with human mourning is to underestimate (often by a lot) just how long mourning takes … even perfectly normal, healthy mourning.

For a major loss, main mourning takes up to a year. No joke. That’s why bereavement counselors try to keep the bereaved from making any permanent decisions within that year. They’re still very much being buffeted by the winds of grief, even if they want to pretend they aren’t. But even after the year anniversary—and marking it with some sort of formal ceremony helps!*—mourning continues off-and-on (sometimes really intense for a few hours or even a few days) for up to 5 years. Again, no joke. Some bereavement studies experts don’t really consider a person truly recovered (note I never say “over it”) for as long as 10 years.

Additionally, ANY deep loss triggers mourning; it doesn’t have to be death. A divorce will result in mourning, even if the people in the marriage wanted to divorce. It’s still a “death” of sorts. Moving some distance away, graduation, and retirement can all set off mourning. This surprises people, that mourning can attach even to “happy” circumstances. Anything that includes an ending will set off mourning, albeit it may not be that intense.

But THE #1 and #2 most devastating losses are the loss of a child and the loss of a spouse/spouse-like figure. Period.

So, a slight correction to the question, I didn’t say he’d recovered from his mourning, but that he was beginning to emerge from the deepest parts of mourning.

What do I mean by that? There are (roughly) 3(-4) major phases of mourning. The speed at which we pass through these varies, dependent on the type of death and our closeness to the deceased. (The first article goes into that in more depth.)

Shock phase, which is typically anywhere from a few days to about 2 weeks.

Deep mourning phase, where the bereaved must come to terms with the loss. The bereaved cycles through a series of stages (not the best term) and, more importantly, struggles with certain TASKS of mourning (as per Worden). Again, the length of this phase can vary, but for serious losses, it can take up to 8-9 months, with the worst of it usually hitting 3-6 months. There is an intense focus on the deceased and the bereaved person may want little to do with new people and vacillate between wanting to talk a lot about the deceased or wanting to give away all their stuff because it’s too painful. Anger, bargaining, depression, self-blame … all are typical of this phase. It’s INTENSE. It really does take months, and people routinely underestimate it.

Re-emergent phase, where the bereaved begins to take an interest again in the external world, may make new friends and new plans that don’t involve the deceased. The deceased is far, far from forgotten, but the bereaved is learning to live without the dead person.

Continued bereavement would be a fourth phase past the one-year anniversary, where the bereaved will still experience grief, sometimes very intense when triggered by a particular memory, a birthday, or anniversaries. But the overall “worst” part of mourning is past.

Finally, especially in the deepest part of mourning, the depression felt by the bereaved is on par with clinical depression, but (except for rare cases) the bereaved absolutely should not take or be prescribed antidepressants as these interrupt the mourning process.

Yes, it hurts like hell but one can only go through, not over, around, or under. Through.

In some cases, however, bereavement becomes “complicated,” resulting in what’s referred to as pathological bereavement, by which I mean only not normal (I wouldn’t even say abnormal). Sudden death (as with Hephaistion) IS one factor that can complicate mourning, but it doesn’t necessarily lead to full-blown pathological grief. In the article, I evaluate all Alexander’s listed behaviors and explain why my final conclusion is that his bereavement was sharp, but not pathological.

Alexander’s behavior in the last few months showed aspects of the third phase. He was planning (or probably returning to planning) his next campaign and thinking about improvements to the city of Babylon apparently with the intention of making it his eastern capital. Yes, he was also planning Hephaistion’s funeral, but the other two things were new and show re-engagement.

So Alexander’s mourning had not ended before he died himself, only shifted. Even if he’d lived another 5 years, he’d still have experienced bereavement off and on.

Remember, grieving takes TIME. More time than you expect.

If you know someone going through grief, especially for a family member, beloved, or very close friend … give them space. Let them cry. Encourage them to talk about the lost person if they want to, but don’t force it if they don’t want to. Don’t argue with their theology/beliefs about death or their gallows humor, but also don’t shove your theology/beliefs about death, or your gallows humor, onto them. Read the room.

MOST OF ALL, JUST BE PRESENT. It matters less what you say than that you’re there. They may not even remember what you say later; they will remember you showed up.

—————-

* In fact, world cultures that have traditional, one-year anniversary ceremonies routinely show better outcomes for mourning individuals.

#asks#Alexander the Great#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#death of Hephaistion#death of Hephaestion#Mourning of Alexander the Great#bereavement#mourning#tasks of mourning#stages of grief#Alexander the Great's grief#alexander x hephaestion#alexander x hephaistion

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Debunking Series: Normal Dimensions of Multiple Personality Without Amnesia

Hello all! I spent the better part of today (the last 3 hours or so, I believe) reading through a horrific article that was part of a list of "sources proving nondisordered plurality." I wanted to read through all of these sources and thoroughly discuss what is good and bad about them.

Sadly, this article has nothing good.

The full debunk can be found at this link, or below the cut. The link also includes a link to the article in question, as well as the casebook referenced in the article.

TL;DR: This article is horrifically ableist, fakeclaims DID systems (including a real actual case study), and suggests that DID systems are simply fantasizing their alters due to traumatic events -- suggesting that everyone is "naturally" plural, and that DID systems imagine new alters to hold amnesia.

TW: Fakeclaiming, discussions of trauma (SA, abandonment, war, food scarcity), poor research methods.

“IMAGINATION, COGNITION AND PERSONALITY, Vol. 18(3) 205-220, 1998-99

NORMAL DIMENSIONS OF MULTIPLE PERSONALITY

WITHOUT AMNESIA”

The TL;DR summary of the article: These people made a survey with the express purpose of proving that multiple personality states are completely normal. To do this, they fakeclaim DID, suggest it is completely imagined, and that the only pathological part of DID is the amnesia. Their survey proves nothing beyond what they claim it should be showing, their sample size is a mere 209 people at a single college (with no remarks to age, race, gender, etc – all of which are factors in developing DID), and they end off the article with such wonderful lines as “It is not surprising that a fantasizer like Frieda would exhibit dissociative amnesia in response to trauma, even though most traumatized persons do not dissociate, because absorption in fantasy has been shown to be a diathesis for dissociative responses to traumatic stressors [6],” or “The fact that ‘animal alters’ have actually been reported by DID patients [30] gives added credence to our suggestions that multiple personality results when emotionally incompatible self images are fantasized (with or without amnesia), not when personality and memory are fragmented.” Simply put, this article is horrific, and proves nothing. Full live reactions below.

“In Harter’s view, it is not unusual for the normal adolescent to experience himself or herself as different people in different situations” – Is this not simply IFS? It is not at all unusual to experience yourself as multiple different people - “work self versus home self” has always been a thing. This is remarkably different from the Completely Dissociated From Each Other Personalities that we see in DID.

“Moreover, the old DSM-III-R syndrome of Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD) had diagnostic criteria corresponding to multiple self-identity and multiple self-control, but none corresponding to dissociative amnesia [9], and studies found 30 percent to 50 percent of people with MPD to be “high-functioning”” – Excuse me, but why is this relevant? Why are you bringing up MPD, from a previous DSM, from a time before we knew somewhat better about DID and how it forms? At the point this was published, the DSM 4 had been out for 5 years; why go back to a previous DSM? Why remark on the “high-functioning” label? Is this meant to argue that those high-functioning individuals were actually endogenic? Is this meant to argue that those with DID cannot be high-functioning? I think this is a completely unintentional bit of ableism on the author's parts.

“Our thesis predicts that many more, totally normal people with multiple personalities, but no amnesia, never even come to the attention of the clinical psychological establishment.” – … You mean OSDD? You mean the other representation of dissociative disorder in which amnesia barriers are not present between alters? You mean that completely clinically recognized phenomenon? Yeesh. DDNOS was in the DSM-4 – they have no excuse.

“Such an assertion, however, ignores the fact that many religious adults with no psychopathology experience God as their imaginary companion. Two studies have even documented normal dissociation, without pathological dissociation, in religious mystics who ritualistically imagine themselves being possessed by spirits [19, 20].” – Yes, remarkably, the DSM-4 did not feel the need to remark that a purely spiritual experience is different from the pathological psychological experience they were describing. Because of studies like this one, however, the DSM-5 added in the cultural exemption criteria, in which this sort of thing is explained as Very Clearly Not DID. No fault of the authors for not reading the future, but again – are they now arguing that mystics and ritual possession are endogenic plurality?? What does this have to do with DID? They’re totally different experiences.

METHODS – This is, by far, the shortest methodology section I have ever seen in an article. The summary of their methods: They gave people a survey that they, themselves, crafted. This survey consisted of 31 questions, each with three parts. People self reported their sense of self, sense of control, and sense of memory. It was posited by the authors that higher rankings on A and B were demonstrable as higher levels of dissociation, but only higher rankings on C were indicative of DID… without… stating why that was or how that was proven. They also failed to address: was this completed online, or on paper? Was there a time limit? Were participants paid for their answers? How did you authenticate that the survey actually correlates to the DES (which, this article itself points out is a flawed and only partial examination of dissociation, which cannot, on its own, validate DID)? This study did jack shit and they know it.

SUBJECTS – Oh my god it got even shorter??? This is a failing grade in any psych class. “The subjects for this research were randomly sampled from General Psychology classes at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, and were tested in group settings. Two hundred nine subjects completed the questionnaires.” What are their ages? Gender? Race? Do any of them have a diagnosis of a dissociative disorder already? Have you examined these randomly selected individuals for their medical histories of schizophrenia or BPD, two things that impact the sense of self tremendously? How could you call these normal representations of multiple personalities when you can’t even tell me their age range??? This is stunningly negligent.

“Our finding in Figures 3 and 4—that subjects tend not to exhibit multiple personality with amnestic features on Scale C unless they also exhibit normal features of multiple personality on Scales A and B—further supports our hypothesis that the DID patient’s pathological amnesia for trauma is superimposed on pre-existing normal dimensions of multiple personality.” – Woah there buddy, slow the roll. Your hypothesis was simply that multiplicity without amnesia was a normal experience, and that the trauma is what creates amnesia. You have now changed your hypothesis to be that DID systems are just naturally plural with some pesky amnesia being the issue. You’re saying the alters are just… normal, and that DID systems who have alters are only disordered because they have amnesia. What does this mean for the alters, then? Why are my alters suffering from dissociation, then? Is the amnesia my only problem?? Jesus…

“Indeed, in the only case of multiple personality in the DSM-III-R Casebook, the patient Frieda started fantasizing alternate personalities during early childhood” – WHAT. WHAT IN THE FUCK. Are you really, really, going so far as to suggest that this case study was of an individual who was naturally multiple in childhood, because she fantasized (you know, fantasy theory, that shit Freud pushed, that shit that’s been used to invalidate and fakeclaim DID systems for years???) her fucking alters… Out of curiosity I went and found this casebook. More discussion about this topic is below the liveblog, because surprise surprise, this article purposely omit things about the case study…

“It is not surprising that a fantasizer like Frieda would exhibit dissociative amnesia in response to trauma, even though most traumatized persons do not dissociate” – Fuck you. Genuinely, where does this claim come from? I know you cite a source, but genuinely, everything we have seen about fucking dissociative disorders is that the people with them, surprise surprise, fucking dissociate. What gives you the goddamn right to fakeclaim?

“It remains an empirical question, however, whether actual DID patients of this sort would remember their alternate personalities well enough to score high on Scale A, but Figure 3 suggests that they would” – They have to use the word ‘suggests’ here because they never fucking clarified if any of their participants have DID.

“The gentleman who experiences irreconcilably violent impulses on the football field, for example, might imaginally integrate such impulses into an alternate personality that is “pure animal.” The fact that “animal alters” have actually been reported by DID patients [30] gives added credence to our suggestions that multiple personality results when emotionally incompatible self images are fantasized (with or without amnesia), not when personality and memory are fragmented.” – Read that again and fully understand it. Need a translation? “The man who has violent impulses that conflict with his regular personality might imagine that those impulses are a violent animal personality. This suggests that animal alters in DID are just conflicting emotions that are imagined to be real alters.” This is the article people are upholding as endogenic plurality.

To be blunt: fuck anyone who reads this and tries to suggest it’s proving endogenic plurality.

Discussion of the DSM-III Casebook (Specifically, the entry on Frieda) - This is entirely from Circular, none of this is from the article, so I'll drop the color coding for this section.

Located on Page 114 of the Casebook (located at this link, this was the best I could find – made an account, borrowed the book for an hour), is the case study Frieda. Frieda was a 42 year old woman who, accompanied by her husband, sought consultation with a psychiatrist. She went primarily at her husband’s request due to marital problems.

Frieda was “daydreaming” during the consultations, and her husband reported her acting startlingly different at times (dressed in new attire, leaving the house for hours or even days with no communication, seeming to act like a little girl after disagreements and being unable to get out of that space, etc). Under hypnosis, Frieda was able to describe events in her childhood, which were incredibly traumatic (father was killed, mother abandoned her, was raised in multiple orphanages that were lacking in food and supplies, and raised by nuns, etc etc etc). What Freida describes next is that, at the age of 4, she had an “imaginary companion” of the same age who she would “run away with” to a field to play with dolls. This companion remained with her well past childhood, and their escapes from reality would only increase in frequency after she was molested by Soviet soldiers after the war.

The case describes her struggles in her marriage (particularly with a more promiscuous alter – if I had to hazard a guess, a sexual persecutor – stepping in frequently when arguments occurred) and struggles with parenthood (where a little would clearly begin fronting and she would be returned to the war-time flashbacks). After leaving hypnosis, the client had no memory of these events.

This is clearly DID. This is very similar to much of what I’ve experienced and gone through, albeit with hypnosis taking a very different role in my own life. The article posits that this woman was raped, and before that instance, she had simply an imaginary friend. This completely ignores – and in my opinion seeks to invalidate – the traumatic childhood Freida experienced. The authors are positing that her experience of having alters is completely normal, and the thing that caused her amnesia was the sexual assault she experienced. This is ignoring her feelings toward her mother who abandoned her, which today is regarded as a primary leading cause of DID developing (disorganized attachment theories).

So, in order to prove that Freida is merely a regular, normal person with amnesia, they fakeclaim her childhood trauma and suggest she’s simply fantasizing these alters (and, of course, all of their actions and everything, which she has no memory of) due to later trauma she experienced. Because god forbid anyone acknowledge a DID system having childhood trauma.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

The discovery that general paresis was caused by a bacterial microorganism and could be cured with penicillin reinforced the view that biological causes and cures might be discovered for other mental disorders. The rapid and enthusiastic adoption of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), lobotomy, and insulin coma therapy in the 1930s and 1940s encouraged hopes that mental disorders could be cured with somatic therapies. Psychiatry's psychopharmacological revolution began in the 1950s, a decade that witnessed the serendipitous discovery of compounds that reduced the symptoms of psychosis, depression, mania, anxiety, and hyperactivity. Chemical imbalance theories of mental disorder soon followed (e.g., Schilkraudt, 1965; van Rossum, 1967), providing the scientific basis for psychiatric medications as possessing magic bullet qualities by targeting the presumed pathophysiology of mental disorder. Despite these promising developments, psychiatry found itself under attack from both internal and external forces. The field remained divided between biological psychiatrists and Freudians who rejected the biomedical model. Critics such as R. D. Laing (1960) and Thomas Szasz (1961) incited an “anti-psychiatry” movement that publicly threatened the profession's credibility. Oscar-winning film One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (Douglas & Zaentz, 1975) reinforced perceptions of psychiatric treatments as barbaric and ineffective.

In response to these threats to its status as a legitimate branch of scientific medicine, organized psychiatry embraced the biomedical model. [...] The publication of the DSM-III in 1980 was heralded by the APA as a monumental scientific achievement, although in truth the DSM-III's primary advancement was not enhanced validity but improved interrater reliability. Psychiatrist Gerald Klerman [...] remarked that the DSM-III “represents a reaffirmation on the part of American psychiatry to its medical identity and its commitment to scientific medicine” (p. 539, 1984). Shortly after publication of the DSM-III, the APA launched a marketing campaign to promote the biomedical model in the popular press (Whitaker, 2010a). Psychiatry benefitted from the perception that, like other medical disciplines, it too had its own valid diseases and effective disease-specific remedies. The APA established a division of publications and marketing, as well as its own press, and trained a nationwide roster of experts who could promote the biomedical model in the popular media (Sabshin, 1981, 1988). The APA held media conferences, placed public service spots on television and spokespersons on prominent television shows, and bestowed awards to journalists who penned favorable stories. Popular press articles began to describe a scientific revolution in psychiatry that held the promise of curing mental disorder. [...]

United by their mutual interests in promotion of the biomedical model and pharmacological treatment, psychiatry joined forces with the pharmaceutical industry. A policy change by the APA in 1980 allowed drug companies to sponsor “scientific” talks, for a fee, at its annual conference (Whitaker, 2010a). Within the span of several years, the organization's revenues had doubled, and the APA began working together with drug companies on medical education, media outreach, congressional lobbying, and other endeavors. Under the direction of biological psychiatrists from the APA, the NIMH took up the biomedical model mantle and began systematically directing grant funding toward biomedical research while withdrawing support for alternative approaches like Loren Mosher's promising community-based, primarily psychosocial treatment program for schizophrenia (Bola & Mosher, 2003). The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), a powerful patient advocacy group dedicated to reducing mental health stigma by blaming mental disorder on brain disease instead of poor parenting, forged close ties with the APA, NIMH, and the drug industry. Connected by their complementary motives for promoting the biomedical model, the APA, NIMH, NAMI, and the pharmaceutical industry helped solidify the “biologically-based brain disease” concept of mental disorder in American culture. Whitaker (2010a) described the situation thus:

In short, a powerful quartet of voices came together during the 1980s eager to inform the public that mental disorders were brain diseases. Pharmaceutical companies provided the financial muscle. The APA and psychiatrists at top medical schools conferred intellectual legitimacy upon the enterprise. The NIMH put the government's stamp of approval on the story. NAMI provided moral authority. This was a coalition that could convince American society of almost anything… (p. 280).

–Brett J. Deacon, "The biomedical model of mental disorder: A critical analysis of its validity, utility, and effects on psychotherapy research." Clinical Psychology Review 33 (2013), 846–861. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.007

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first Hellraiser is this really compelling erotic sci-fi horror whose main problem is that—deserving or not—the place it occupies in our culture is Reefer Madness but for BDSM, but the second movie adds this really tacky “BDSM? More like B-DSM-5 [it was DSM-III-R at the time whatever]” that kinda ruins the whole vibe. The 2022 Hellraiser reboot brilliantly made Pinhead an absolute babe, but it was so sexlessly bland and philosophically vacant in its nostalgia chasing that it leaves most things unexplored in a movie about sexual exploration so far-reaching it delves into an alien dimension where pain and pleasure are indistinguishable. I was gonna rant about how Anglo Protestantism dooms us to shitty Hellraiser movies because its “temporal suffering is punishment for sin” diminishes the possibility of erotically fulfilling paradigms for suffering (for all its faults, Roman Catholicism leaves open the possibility of suffering as sanctification or at the very least the Biblically accurate acknowledgement [Job, Ecclesiastes, Jesus] that temporal suffering often has no correlation with morality), but admitting I’m an Anglo-Catholic queer usually makes people assume I’m an idiot—which is a very Anglo Protestant way to practice atheism, by the way, if you were wondering why it’s not constructive or sociable 🤷🏻♀️

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

History of Situational Mutism

have made a post on this before, so have taken some parts of that. but this is more comprehensive. aka long post like looong⚠️

summary:

aphasia voluntaria -> elective mutism (voluntary, refusal, oppositional) -> DSM IV = inability (failure, rather than refusal, to speak).

differential diagnoses: DSM-III = developmental disorders -> IV and IV-TR = speech abnormalities and social anxiety disorder -> DSM-V = communication disorders, social anxiety and psychotic disorders like schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders.

2013 DSM-V changed it from Childhood disorder to anxiety disorder. it also removes reference to trauma as a possible cause.

DSM IV-TR said SM had slightly more females than males. DSM-V says SM has equal gender distribution.

People thought DSM-V would subsume SM into SAD, but it didn’t due to the uncertainty around the relationship between SM and SAD.

It has since been recognised unofficially as ‘situational’. but this is not enough because ‘mutism’ also ignores how SM can affect all communication.

“It was back in 1877 that a German physician called Adolph Kussmaul used the term ‘aphasia voluntaria’ to describe children who ‘refused’ to speak though they could speak normally. Kussmaul used the term after he reported three clinical cases with similar symptoms (Jainer, Quasim, & Davis, 2001). In 1934, a child psychologist from Switzerland called Mortis Tramer used the term ‘elective mutism’ for the first time to describe ‘a fascinating group of children, whose talking is confined to familiar situations’ (Kolvin, Trowell, Le Couteur, Baharaki, & Morgan, 1997). Going by both the terms, it can be seen that the understanding was of a voluntary act of refusing to speak, which would mean it was an oppositional behavior (Noelle, 2017).

The same understanding is reflected in the diagnostic criteria given by the earlier versions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM). The third editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-III and DSM-III-R) explained elective mutism in terms of ‘refusal to speak’. This was changed in the fourth edition of DSM, where it was recognized as an inability to speak (Noelle, 2107). The diagnostic criteria given in DSM-III (APA, 1980) talks of ‘continuous refusal to speak in almost all social settings’, while the diagnostic criteria given in DSM-III-R (APA, 1987) updated it to ‘persistent refusal to speak in one or more social settings’. In contrast, after the publication of DSM-IV in 1994, the diagnostic criterion read ‘failure to speak in specific social situations’.

There are other differences between the elective mutism as described in the third editions (DSM-III and DSM-III-R) of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuals (APA, 1980, 1987) and the selective mutism as described in the subsequent editions, i.e., DSM-IV (APA, 1994), DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) and DSM 5 (APA, 2013). Some instances would be the predisposing factors and differential diagnosis.

According to both the third editions of the DSM (APA, 1980; 1987), maternal overprotection, speech disorders, mental retardation and trauma were possible predisposing factors for the onset of selective mutism. These factors were, however, removed in the subsequent editions of the DSM (DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR & DSM-5). Similarly, the third editions stated that the ‘refusal’ to speak could be differentially diagnosed as developmental disorders, while the later editions (DSM-IV & DSM-IV-TR) list speech abnormalities and social anxiety disorder as differential diagnosis for selective mutism. DSM-5 (APA, 2013) lists a differential diagnosis of communication disorders, social anxiety and psychotic disorders like schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders.” Source: ‘selective mutism - understanding and management’ by Charu Kriti 🌹🌹

in 2013 the DSM-5 moved SM from the childhood disorders category to the anxiety disorders category. The DSM-5 also drops the reference to trauma as a possible cause of SM, and indicates that SM has equal gender distribution, whereas the DSM-4-TR had indicated slightly more females than males.

People thought the DSM-5 would subsume SM into SAD, but this didn’t happen due to the uncertainty surrounding the relationship between the two disorders. (high comorbidity, some argue SM is an extreme version of SAD; some argue SAD causes SM; others argue vice versa).

people with SM have since recognised it as ‘situational mutism’ to avoid the misunderstanding that sm is ‘selective’ or a choice not to speak; and they consider it an inability to speak in certain situations (people, places, settings). but this name is still not enough in my opinion, because it still focuses on what is considered the biggest problem for OTHER people, rather than for the person. sm is not just mutism (inability to speak); it affects all forms of communication. source: ‘Selective mutism in adults: an exploratory study’ by Carl Sutton. pp 18-19

maybe a better name is communication anxiety disorder or something like that. but then again, it is still not fully accepted as an anxiety disorder; only in official definitions.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Another factor that may have affected prevalence is that autism became a distinct special education category in 1991, shortly after the DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria were introduced. The federal definition of Autism within the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA; 34 C.F.R. § 300.7 (c)(1)[1999]) is ‘a developmental disability [..] that adversely affects a child’s educational performance’ [..] While there are many similarities between the federal [educational] definition and the DSM descriptions, the two are not identical.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Allonormativity in Western Society

tw: mention of psychiatric malpractice, sexual violence, acephobia, homophobia, outdated terminology, misogyny, and Christian fundamentalism.

Reference list below the cut

Allonormativity – modelled from the adjacent concept of heteronormativity – labels the assumption within Western society that experiencing sexual attraction is the default and fundamentally what makes one human (Bonos, 2017). Asexuality has its historical roots running just as deep as any other form of queerness; Karl-Maria Kertbeny who coined ‘heterosexual’ and ‘homosexual’ in 1869 also devised ‘monosexual’, to describe those who only participated in masturbation (Reed, 2023, p. 32). Likewise, in 1896, Magnus Hirschfeld, known for coining ‘transvestite’ and ‘transsexual’, and creating the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, the first sexology research centre, also recognised people without sexual desire, terming it ‘anaesthesia sexual’ (The Asexual Visibility and Education Network, 2014). Despite its rich history, asexuality remains underrepresented both in research and in society’s collective consciousness. In this essay, I intend to explore how acephobia upholds Western individualism and capitalism via the nuclear family, oppugn the notion that Western conservative Christianity doesn’t persecute asexuals in the same way other queer identities are, and demystify the disturbingly overlooked intersection between acephobia, rape, misogyny, and psychiatric malpractice.

The pathologising of non-heterosexual sexuality in Western society may seem like something of the distant past, now a tiny dot reflected in history’s side mirror; however, while homosexuality was declassified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1974, it wasn’t until 2013 that asexuality followed suit. I believe that when comparing the history behind homosexuality’s and asexuality’s declassification there are parallels. To provide context, in 1952, the DSM-I classified homosexuality as a sexual deviation under the category of ‘sociopathic personality disturbance’ (American Psychiatric Association, 1952, pp. 39, 85); in 1968 the DSM-II identified homosexuality officially as a mental disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 1968, pp. 79). Spurred on by the exponential increase in queer rights activism following the Stonewall Riots, the DSM-II in 1974 was edited, stating that “[homosexuality] by itself does not constitute a psychiatric disorder,” yet maintaining the diagnostic of, “individuals whose sexual interests are directed primarily toward people of the same sex and who are either disturbed by, in conflict with or wish to change their sexual orientation” (American Psychiatric Association, 1973, pp. 1). In a nutshell, homosexuality was no longer considered a mental disorder; however, an individual who felt distressed by their queerness and wanted to be converted to heterosexuality would be recognised as having a sexual orientation disturbance, thus, retaining the societal assumption that heterosexuality is the norm and default. Furthermore, the DSM-III published in 1980 changed this prior diagnosis to ego-dystonic homosexuality, and then in 1987 the DSM-III-R again revised it as “persistent and marked distress about one’s sexual orientation” (American Psychiatric Association, 1980, pp. 281) (American Psychiatric Association, 1987, pp. 296). Finally, as of the DSM-V published in 2013, there are no listed diagnostic criteria pertaining to one’s sexuality – and while I had stated earlier that homosexuality had been declassified in 1974, I believe the complete removal of sexuality-based criteria is more akin to depathologisation.

Now, when considering asexuality, we see a similar pattern of pathologisation, with the DSM-III having listed inhibited sexual desire disorder (ISD), alternatively referred to as simply sexual aversion or apathy. The current DSM-V hosts the reworked condition called hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), which is split further into two gendered disorders – male HSDD (MHSDD) and female sexual interest/arousal disorder (FSIAD) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, pp. 433-437). In 2007, asexual rights activists with the Asexuality Visibility Education Network (AVEN) rallied to have asexuals recognised as being a separate entity from those that experienced a lack of sexual desire due to a medical condition; this was distinguished in the manual – “if a lifelong lack of sexual desire is better explained by one’s self-identification as ‘asexual,’ then a diagnosis of [FSAID or MHSDD] would not be made” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, pp. 434). In my opinion, this negotiation of recognising the existence of asexuals while also continuing to medicalise normal sexuality based on societal notions of sexuality is perfectly comparable to the DSM-II in 1974 compromising that while homosexuality wasn’t in itself a medical condition rather one can consider it as such if the individual is distressed by their queerness. Moreover, when evaluating the social context in which ISD was termed and the subsequent development of HSDD, one must consider Western society during the 1970s as what constitutes normal levels of sexual desire vary depending on one’s culture. Western society during the 1970s placed great emphasis on sexual desire as a sexual revolution took hold due to an influx of factors such as the recent development of the pill and other contraceptives, women’s liberation movements, interracial dating, cultural values shifting away from traditional Christian restraints, queer visibility, capitalism adopting sex as a means to sell a product, and the like (Tompkins et al., 1995). While I agree that all of these bar the last were important markers, this emphasis on sexual desire as inherent and something everyone would experience led to the creation of these disorders with the assumption that asexuality is something that can and needs to be fixed. While some may not see this as too problematic, at least compared to the medicalisation of homosexuality, one must remember that asexuals do not benefit from the upholding of cisheterosexuality, as a lack of attraction, just like attraction considered deviant, are both viewed as something in need of correcting. If homosexuality was rightfully depathologised, why can’t asexuality be too? In my opinion, apart from the issues that arise from asexuals being misdiagnosed with HSDD, and the over-fixation of what is considered acceptable sex and sexuality in the West, HSDD is too wide and too vague of a diagnosis to have any meaning as it’s lumping together people that are experiencing varying disorders with just one trait in common. Overall, I believe in this regard, psychiatry has done more harm to the queer community, as unfortunately, asexuals are highly likely to experience sexual violence, specifically corrective rape, due to this belief that minimal or a lack of sexual desire – especially in women – is something to fix.

To expand on this intersection which has formed from the pathologising of sexuality, and sexual violence, I’ll be discussing the prevalence of sexual assault experienced by asexuals. The term ‘corrective rape’ was initially coined in South Africa to describe the phenomenon in which lesbians are raped by cishet men to ‘cure them’ of their queerness (Koraan & Geduld, 2016, pp. 1932). Despite its particular definition, as lesbians are frequently targeted in this way (Meyer, 2012, p. 864), the term has transcended to describe any form of rape that is enacted on a queer person with the false notion that it’ll ‘correct’ the victim’s sexuality, making them heterosexual. Generally, ‘corrective rape’ is still associated with lesbians; however, just as any queer individual may be subjected to this form of sexual violence, so have asexuals. Asexuality is often referred to as ‘the invisible orientation’ due to its lack of public recognition, as such, sexual violence against asexuals is often overlooked and dismissed as something you’ll eventually come around to enjoying, which results in alarming statistics (Kliegman, 2018). According to the 2015 Asexual Community Census Summary Report organised by AVEN which surveyed around 8,000 asexuals, 35.4% of participants reported experiencing sexual contact (e.g., groping or kissing) that they didn’t consent to/were unable to consent to, 18.5% reported being coerced into sex due to social pressure from their partner, and 43.5% reported having experienced sexual violence, often with the intention to ‘fix’ their lack of sexual desire (Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault | MCASA, 2015). I believe that the pathologisation of asexuality reinforces rape culture by labelling asexuality as a disorder it helps justify the concept of ‘curing’ it like any other sickness. As previously mentioned, what is considered a regular level of sexual desire is subjective. As such, I believe that there are certain considerations that must be taken in order to help reduce the frequency of corrective rape against asexuals happens. We would need increased visibility of asexuals, as a culture we must also acknowledge that normative sexual desire is a social construct, that there is no morality attached to sexuality, and that sexual and romantic milestones should be irradicated from the mind by instilling this notion that certain actions (e.g., first kiss, loss of virginity, etc) should happen by a certain age or have to happen at all, it fuels coercion as people don’t want to be socially ostracised.

When considering how acephobia presents itself in Western culture, we can’t eschew examining how Christian ideology embedded in our society shapes our views on sexuality. I propose that asexuality, just like any other form of queer expression, is oppressed by Christian fundamentalism. Often, I’ve seen this argument disputed with the claim that asexuals wouldn’t be harmed by these views due to Christian fundamentalism preaching pre-marital abstinence; however, I beg to differ. Whether a gay person is sexually active or not doesn’t change whether or not they’re considered immoral by the standards of Christian fundamentalism, as the sex isn’t the problem, it’s the fact that you’re different at all (Fulton et al., 1999) (MacInnis & Hodson, 2012). An example of this was in 2015 when Russia passed a road safety law that tried to place a ban on certain people from driving with the Association for Russian Lawyers for Human Rights stating that it would affect, “all transgender people, bigender, asexuals, transvestites, cross-dressers, and people who need sex reassignment” (Oliphant, 2015). Luckily, after much criticism, it was clarified that it wouldn’t affect these people (The Moscow Times, 2015). Ergo, from this example, it is apparent that as asexuals are different to heterosexuals, they don’t reap any benefits or are safe from the moral judgement of Christian fundamentalism despite generally not engaging with sex. Adjacently, while abstinence is a key tenet, there is still the expectation that one will engage in cisheterosexual sexual intercourse once they’re married and that they will bear children, with even in some jurisdictions a lack of consummation being grounds for annulment, such as in England in Wales according to the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 (United Kingdom) (s 12). I don’t need to explain how this feeds into the alarming statistics of corrective rape against asexual individuals. While all of these concerns can be correctly considered as being rooted in misogyny, I think it more appropriate to consider it both an issue of misogyny and acephobia, as these things can overlap, doubly so if experienced by an asexual woman or any genderqueer asexual individual that is subject to misogyny.

Finally, the intersection between capitalism and allonormativity is something I don’t see nearly discussed enough. To review, Western society has transitioned from the large, interconnected, extended families prior to the 19th century, to the isolated nuclear family of the current era (Brooks, 2020). These larger families, which remain common in non-Western countries, were a complex safety net that allowed for more people to shoulder the weight of rearing children and overall creating community – by cutting this down to one man, one woman, and two point five children, it effectively put a strain on the family unit by focusing on the then new cultural importance of a love-marriage. The industrialisation of Western society corresponded with a decline in farming, which led to the burgeoning of the nuclear family as more people moved away from their multigenerational cohabitating families to work and marry young. Cultural values of the Western middle and upper-middle class shifted to assume the importance of individuality over the collective (Bulbeck, 2003, pp. 57). During the mid-20th century, the nuclear family peaked as fertility rates rose while divorce rates dropped – it was so taken with that a survey conducted in 1957 revealed that more than one in two Americans believed that unmarried people were “sick”, “immoral”, and “neurotic” (Guillén, 2023). However, despite the nuclear family being formed from love marriages, one must not forget that a crucial aspect underlying it is that their children will grow up to work and start their own nuclear family and continue the cycle, essentially, reducing the family down to a farm for the creation of workers. Although the stigma attached to unmarried folk has declined, the nuclear family remains the default within Western society, and as such, is still considered the norm. Therefore, by not challenging allonormativity, which pushes the assumption that experiencing sexual attraction is the standard – specifically heterosexual attraction – we as a society continue to uphold capitalism via the nuclear family. Thus, I believe by not deconstructing our socially erected relationship hierarchy, the nuclear family as the standard path, and the social expectations around sexuality, we won’t fully be able to free ourselves from the binds of capitalism.

Overall, through this essay’s analysis of the intersection between capitalism and acephobia, Christian fundamentalism and allonormativity, and the connection between acephobia, corrective rape, and psychiatry, I have come to the conclusion that although asexuals aren’t treated with the same level of disgust by acephobes as gay people are by homophobes, that doesn’t reduce the importance in recognising allonormativity as another societal norm to deconstruct. Moreover, I consider allonormativity and acephobia to be a form of prejudice and an aspect of queerphobia as an oppressive structure.

Reference List:

Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 (United Kingdom)

American Psychiatric Association. (1952). DSM-I: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (1st ed., pp. 39, 85). American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychiatric Association. (1968). DSM-II: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (2nd ed., p. 79). American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychiatric Association. (1973). Homosexuality and sexual orientation disturbance: Proposed change in DSM-II, 6th printing, page 44 (pp. 1, 5). American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychiatric Association. (1980). DSM-III: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed., pp. 281). American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychiatric Association. (1987). DSM-III-R: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed., pp. 296). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Bonos, L. (2017, July 6). Analysis | bugging your friend to get into a relationship? How amatonormative of you. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/soloish/wp/2017/07/06/what-is-amatonormativity-the-belief-that-youre-always-better-off-in-a-romantic-relationship/

Brooks, D. (2020, February 10). The nuclear family was a mistake. The Atlantic; The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/03/the-nuclear-family-was-a-mistake/605536/

Bulbeck, C. (2003). Re-orienting western feminisms: Women’s diversity in a postcolonial world (pp. 57–96). Cambridge University Press.

Fulton, A. S., Gorsuch, R. L., & Maynard, E. A. (1999). Religious Orientation, Antihomosexual Sentiment, and Fundamentalism among Christians. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 38(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1387580

Guillén, M. F. (2023, August 24). Why we must replace the American nuclear family with a “postgenerational” society. Big Think. https://bigthink.com/the-present/replace-american-nuclear-family-postgenerational-society/#:~:text=A%201957%20survey%20revealed%20that

Kliegman, J. (2018, July 27). When you’re an asexual assault survivor, it’s even harder to be heard. BuzzFeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/jmkliegman/asexuality-sexual-assault-harassment-me-too

Koraan, R., & Geduld, A. (2016). “Corrective rape” of lesbians in the era of transformative constitutionalism in South Africa". Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal/Potchefstroomse Elektroniese Regsblad, 18(5), 1930–1952. https://doi.org/10.4314/pelj.v18i5.23

MacInnis, C. C., & Hodson, G. (2012). Intergroup bias toward “Group X”: Evidence of prejudice, dehumanization, avoidance, and discrimination against asexuals. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 15(6), 725–743. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430212442419

Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault | MCASA. (2015). Sexual Violence Against the Asexual Community. MCASA. https://mcasa.org/newsletters/article/sexual-violence-against-the-asexual-community

Meyer, D. (2012). An intersectional analysis of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people’s evaluations of anti-queer violence. Gender & Society, 26(6), 849–873. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243212461299

Oliphant, R. (2015, January 9). Vladimir Putin bans transsexuals from driving. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/11334934/Vladimir-Putin-bans-transsexuals-from-driving.html

Reed, K. (2023). Erasing Invisibility: Asexuality in the Media. In Global LGBTQ+ Concerns in a Contemporary World : Politics, Prejudice, and Community (pp. 30–57).

The Asexual Visibility and Education Network. (2014, February 8). (Indirect) mentions of asexuality in Magnus Hirschfeld’s books. https://www.asexuality.org/en/topic/98639-indirect-mentions-of-asexuality-in-magnus-hirschfelds-books/

The Moscow Times. (2015, January 14). Health ministry says transsexuals can still drive in Russia. The Moscow Times. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/archive/health-ministry-says-transsexuals-can-still-drive-in-russia

Tompkins, V., Baughman, J., Bondi, V., Layman, R., Bargeron, E. L., & Tidd, J. F. (1995). American decades: 1970-1979. American Decades.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi !! System who's also very interested in psychology/psychiatry/cognitive science here -- saw you talking about the DSM, can I ask about your general opinions on it (since I know a lot of people have a lot of opinions on it, and I really like hearing other people's thoughts about this hehe)

yeah, i would love to talk about this! our opinions are always subject to change ofc, but here’s the right now opinions

also just to remind everyone: we are not medical professionals! we’re just an autistic kid with a DSM who likes to talk about it. listen to professionals please!

so generally, i feel like the DSM has room for improvement- it always does, but i do think it’s a lot better than some people seem to think. it’s done a really good job of moving past some outdated language, such as moving to the use of intellectual disability instead of using the hard R, and moving to ASD (and the levels) instead of the multiple previous pervasive development disorder diagnoses. the DSM also does a good job in the preface and the “use of the manual” section, both noting how the manual is not capable of representing the entire range of disordered experiences (hence the “other specified” and “unspecified” disorder diagnoses). it also notes how the DSM should not be used “in a cookbook fashion” (the desk reference actually uses that analogy), and how clinical judgement is incredibly important when it comes to assessment.

in regards to improvements, i would say the biggest thing would be to change the language used around personality disorders. the (emerging) alternative model for diagnosing personality disorders in section III is definitely an improvement, but (to me) it seems like there is bias towards the people with personality disorders in what is supposed to be solely objective criteria. i would also just want to look at oppositional defiant disorder, i think that it needs to be reevaluated in some ways- especially when in comes to how racially biased the diagnosis of it seems to be (though that may be an issue with biased practitioners, it still deserves to be looked at).

i honestly think that the main issue with the DSM is how it’s applied by psychiatrists, psychologists, etc, and not the DSM itself. a lot of psych professionals don’t stay up to date with the manual, and most of them don’t read the big chunks of text at the beginning (or at least haven’t since they were in school). i think that personal experience also plays a huge role in understanding the diagnostic criteria, even if your personal experience isn’t having the specific disorder you’re diagnosing! not every psychiatrist or psychologist will be mentally ill or neurodivergent, but i do think it’s important for neurotypical professionals to make an effort to understand the experiences of their mentally ill and neurodivergent patients.

but yeah! i’ll stop my rambling now lmao. tysm for asking, and i hope that this makes some sense ::]]]

#firefly flickers#dsm 5#long post#special interest#infodump#psychology#psychiatry#did system#actually autistic#autism special interest#infodumping

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sadistic Personality Disorder (SaPD)

Note: You cannot be diagnosed with this disorder, as it's not in any diagnostic manual; you would be diagnosed with Other Specified Personality Disorder instead.

Criteria from the DSM-III-R (1987):

A. A pervasive pattern of cruel, demeaning, and aggressive behavior, beginning by early adulthood, as indicated by the repeated occurrence of at least four of the following:

has used physical cruelty or violence for the purpose of establishing dominance in a relationship (not merely to achieve some noninterpersonal goal, such as striking someone in order to rob them);

humiliates or demeans people in the presence of others;

has treated or disciplined someone under their control unusually harshly, e.g., a child, student, prisoner, or patient;

is amused by, or takes pleasure in, the psychological or physical suffering of others (including animals);

has lied for the purpose of harming or inflicting pain on others (not merely to achieve some other goal);

gets other people to do what they want by frightening them (through intimidation or even terror);

restricts the autonomy of people with whom they have a close relationship, e.g., will not let spouse leave the house unaccompanied or permit teen-age daughter to attend social functions;

is fascinated by violence, weapons, martial arts, injury, or torture

B. The behavior in A has not been directed toward only one person (e.g., spouse, one child) and has not been solely for the purpose of sexual arousal (as in Sexual Sadism).

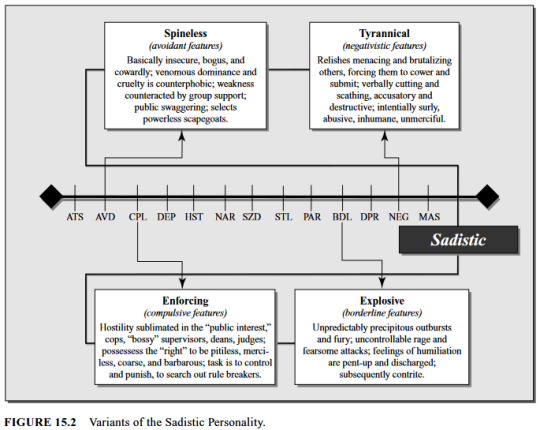

Millon's subtypes:

(Millon, ed.).

About SaPD

SaPD is similar to antisocial, negativistic / passive-aggressive, paranoid, and narcissistic PDs. It's part of what Millon & Bloom term the "Aggressive Personality Patterns", along with AsPD, NPD, & Negativistic / Passive-Aggressive PD.

Differential diagnoses include anxiety disorders, mood disorders, substance abuse, AsPD, psychotic disorders (especially with paranoid & persecutory features), and coercive sexual sadism disorder.

The most common PD comorbidities with SaPD are AsPD (36.45%), Negativistic / Passive-Aggressive PD (24.04%), & NPD (14.09%). The least common was OCPD (0.77%). Less than 1 percent (0.31%) had only ("pure") SaPD [less than those who had comorbid OCPD] (Millon & Bloom).

Millon defines it on a spectrum from assertive -> negativistic (Millon Personality Group); or alternatively from assertive [personality type] -> denigrating [style] -> sadistic [disorder] (Millon).

In the DSM-III-R it was described as being “characterized by pervasive cruel, demeaning, humiliating, and aggressive behavior directed toward others, along with a basic lack of empathy and respect for others" (Coolidge & Segal).

Millon also calls it "Aggressive Personality Disorder" (Millon & Bloom).

People with this disorder "might engage in risky behavior undaunted by danger, and [they] might be forward and inhibiting to others. This kind of person is often described as strongly opinionated, closed-minded, unbending, energetic, hardheaded, competitive, and malicious. [They] might be cold-blooded and detached from awareness of the impact of [their] own actions. Sexual energy might lead to imprudent and unseemly behavior" (Millon & Bloom).

People with SaPD are "socially aggressive and seek to dominate those around them", and "are likely to identify vulnerabilities in [people] and exploit them, producing strong fearful or painful emotional responses" (Millon & Bloom).

Not everyone with SaPD is violent, and some inflict pain by other non-physical means; "[t]he person may inflict pain or suffering by lying; for example, a woman may call her former husband and lie to him about their son's having been seriously hurt" (DSM-II-R).

"People with this disorder rarely experience depression, and their reaction to feeling abandoned is usually anger" (DSM-III-R).

SaPD is often caused by childhood trauma, especially domestic abuse (DSM-III-R). The underlying reason for symptoms is often pain avoidance; "[a]lthough sadistic individuals do seem to acquire a perverse pleasure in inflicting pain on others, the underlying motivation seems to be in their own pain avoidance by inflicting overwhelming pain on others before it can be done to them" (Millon & Bloom).

"... sadists may think of themselves as energetic, assertive, and realistic. What is dominating and callous to others is competitive and not overly sentimental to the sadist" (Millon, ed.).

SaPD only ever appeared in the appendix of the DSM-III-R, and if a person met criteria for this PD they were diagnosed with PDNOS (Coolidge & Segal).

"... it was dropped because of scientific concerns, such as the relatively low prevalence rate of the disorder in many settings. However, there were also political reasons. Physically abusive, sadistic personalities are most often male, and it was felt that any such diagnosis might have the paradoxical effect of legally excusing cruel behavior” (Millon, ed.).

References

Coolidge, Frederick L., & Segal, Daniel L., ‘Evolution of Personality Disorder Diagnoses in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’, Clinical Psychology Review, 1998, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 585-599.

Millon, Theodore, & Bloom, Caryl, The Millon Inventories, 2008.

Millon, Theodore, Disorders of Personality, 2011.

Millon, Theodore, ed., Personality Disorders in Modern Life, 2004.

'Assertive / Sadistic Personality', Millon Personality Group, 2015, https://www.millonpersonality.com/theory/diagnostic-taxonomy/sadistic.htm.

#sadistic personality disorder#personality disorders#pd info#other specified personality disorder#ospd#dogpost#long post#described#described in alt text#dsm-iii-r#dsm iii r#dsm iii#dsm-iii

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abstract This study reports follow-up data on the largest sample to date of boys clinic-referred for gender dysphoria (n = 139) with regard to gender identity and sexual orientation. In childhood, the boys were assessed at a mean age of 7.49 years (range, 3.33–12.99) at a mean year of 1989 and followed-up at a mean age of 20.58 years (range, 13.07–39.15) at a mean year of 2002. In childhood, 88 (63.3%) of the boys met the DSM-III, III-R, or IV criteria for gender identity disorder; the remaining 51 (36.7%) boys were subthreshold for the criteria. At follow-up, gender identity/dysphoria was assessed via multiple methods and the participants were classified as either persisters or desisters. Sexual orientation was ascertained for both fantasy and behavior and then dichotomized as either biphilic/androphilic or gynephilic. Of the 139 participants, 17 (12.2%) were classified as persisters and the remaining 122 (87.8%) were classified as desisters. Data on sexual orientation in fantasy were available for 129 participants: 82 (63.6%) were classified as biphilic/androphilic, 43 (33.3%) were classified as gynephilic, and 4 (3.1%) reported no sexual fantasies. For sexual orientation in behavior, data were available for 108 participants: 51 (47.2%) were classified as biphilic/androphilic, 29 (26.9%) were classified as gynephilic, and 28 (25.9%) reported no sexual behaviors. Multinomial logistic regression examined predictors of outcome for the biphilic/androphilic persisters and the gynephilic desisters, with the biphilic/androphilic desisters as the reference group. Compared to the reference group, the biphilic/androphilic persisters tended to be older at the time of the assessment in childhood, were from a lower social class background, and, on a dimensional composite of sex-typed behavior in childhood were more gender-variant. The biphilic/androphilic desisters were more gender-variant compared to the gynephilic desisters. Boys clinic-referred for gender identity concerns in childhood had a high rate of desistance and a high rate of a biphilic/androphilic sexual orientation. The implications of the data for current models of care for the treatment of gender dysphoria in children are discussed.

[..] Summary of Key Findings

The present study provided follow-up data with regard to gender identity and sexual orientation in boys referred clinically for gender dysphoria. There were three key findings: (1) the persistence of gender dysphoria was relatively low (at 12%), but obviously higher than what one would expect from base rates in the general population; (2) the percentage who had a biphilic/androphilic sexual orientation was very high (in fantasy: 65.6% after excluding those who did not report any sexual fantasies; in behavior: 63.7% after excluding those who did not have any interpersonal sexual experiences), markedly higher than what one would expect from base rates in the general population; (3) we identified some predictors (from childhood) of long-term outcome when contrasting the persisters with a biphilic/androphilic sexual orientation with the desisters with a biphilic/androphilic sexual orientation and when contrasting the desisters with a biphilic/androphilic sexual orientation and the desisters with a gynephilic sexual orientation.