#DANTON AS LENIN???

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I want 2 die

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

From hubris to debris: "Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!"

This mboi to frev tumblrs. It was news to me! Taken from https://bestencyclopedia.com/Robespierre_Monument

Robespierre's self-destructing monument

Robespierre's statue being unveiled in Moscow, on 3 November 1918.

The Robespierre Monument (Памятник Робеспьеру) was one of the first monuments erected in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (later part of the Soviet Union), raised in Moscow on 3 November 1918 – just ahead of the first anniversary of the October Revolution, which had brought the Bolsheviks to power.

Located in Alexander Garden, it was designed by the sculptor Beatrice Yuryevna Sandomierz. Created as part of the "monumental propaganda" plan, the monument was commissioned by Vladimir Lenin, who in an edict referred to Robespierre as a "Bolshevik avant la lettre". It was only one of several planned statues depicting French revolutionaries – others were to be made of Georges Danton, François-Noël Babeuf and Jean-Paul Marat, although only the one of Danton was ever completed.

Created in the context of the ongoing Russian Civil War and with the country in a state of war communism, there were few materials available to make the statue. Lacking bronze or marble, the monument was constructed using concrete, with hollow pipes running through it. This design proved frail, lasting only a few days. On the morning of 7 November only a pile of rubble remained. Over the following days different newspapers supplied varying versions as to why it collapsed, with Znamya Trudovoi Kommuny and others saying it was the work of "criminal" (counter-revolutionary) hands, and Izvestia stating the statue's demise was caused by improper construction.

#frev#robespierre#monuments#french revolution#russian revolution#Shelley#Ozymandias#what happened to Marat's statue?#Danton!

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

When politics gets involved in history (French Revolution part)

As a general rule, when politicians meddle in history, it often creates confusion. Today I will talk about how they handle the French Revolution.

Of course, Jean Jaures did a good job on this period, although there are naturally points to criticize. But generally speaking, our politicians allow themselves to make crude or inappropriate remarks.

There are even serious historians who fall into the trap by making political amalgamations. A few days ago, while doing research, I came across an excerpt from an article by Thierry Lentz, a respected historian, made comments in Le Figaro comparing the left-wing opposition party, France Insoumise, to the Hébertists, labeling them as vulgar. My intention on this page is not to promote France Insoumise, but to qualify the Hébertists as vulgar (I imagine he also includes the Cordeliers and the Exagérés) is not good for me (the only thing that can be qualified as vulgar is the newspaper Le Père Duchesne and Hébert's style). Moreover, what does he mean by the left's reinterpretation of the Terror? He talks about Marxist-Leninist dogma in his terms, but Lenin preferred Danton, who was not a Hébertist. Plus the Bolshevik revolution was not based on the same principles as the French Revolution. The French Revolution has democratic aspects that the Bolsheviks did not apply (I'm not saying this to denigrate gratuitously the USSR, which became Russia, let's be clear). A country that has undergone a revolution compared to another country doesn’t necessarily adopt the same principles (often because there are different contexts, different paths, etc.). And reducing the Hébertists, Cordeliers, or Exagérés to the Terror is quite reductive (I have already expressed my thoughts on the Cordeliers in one of my posts).

Moreover, in left-wing parties, from what I have observed, it is rather the character of Babeuf that is taken up, considered as the father of communism (I once met a communist who saw Momoro as a reference and another who prefer Marat), while France Insoumise is something else (we can rather place Robespierre in the radical left, but I don't think he would have been a socialist, and we can be sure he was not a communist). So why once again Thierry Lentz associates France Insoumise with Trotskyism and Marxist-Leninism for taking up Robespierre? I mean, okay, there were communists who admired Robespierre like Stellio Lorenzi, but clearly not as many as one would think.

While Lentz's expertise in French history is widely respected, such political analogies raise questions about the neutrality of historical interpretation.

Moreover, it is interesting that the fact that "La Caméra explore le temps" rehabilitated the Montagnards led to the end of the program because of the Gaullist government. Once again, politics gets involved in history and leads to very bad results.

Now it's President Macron's turn. With Stéphane Bern, the president started to explain that an edict signed in 1539 by François I imposed French as the sole language in France. However, historian Mathilde Larrère says it was the French Revolution that imposed French as the sole language on the French. Once again, politics in history can lead to bad results.

I won't even talk about certain elements of the far right who claim to be followers of Robespierre because that would be giving them publicity, and it's not my vocation.

Now let's move on to Mélenchon from the France Insoumise party, who also made significant historical errors during this period. First, in one of Robespierre's videos, he calls Marie Antoinette a "spoiled brat." Accusing the former queen of treason I understand, she gave all the information she could to the enemy, but when you hear "spoiled brat," you're passing a value judgment that has nothing to do with it. Finally, he invents a marriage of Pauline Léon, saying that she ended her life in bourgeois fashion with a Girondin.

Moreover, Melenchon explain that the extreme left of the time was manipulated by the corrupt who arrested Robespierre. Okay, there were Billaud-Varennes and Collot d'Herbois in the mix, but you can't tell me that the Plaine was part of the extreme left. Moreover, most of the elements of what was called the extreme left were either in prison, like Claire Lacombe, Pauline Léon, Jean-François Varlet, or eliminated, like Chaumette, Momoro, Ronsin, and Hébert at the time of 9 Thermidor.

Moreover, contrary to what Mélenchon suggested, Chaumette and Hébert were not part of the Enragés movement.

In the end, this is the problem when our politicians try to shape history to fit their agendas. It leads to significant inconsistencies and inaccuracies.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Students of history have long observed the tendency of social movements to overflow their channels. Moderate reformers seize power from tired regimes and alter the traditional way of things, and then extremists wrest power from the moderates; a Robespierre succeeds a Danton; a Lenin succeeds a Kerensky. Often it is not actual suffering but the taste of better things that excites people to revolt. —James MacGregor Burns

Roosevelt: The Lion and the Fox Roosevelt: The Lion and the Fox (at Internet Archive)

0 notes

Text

#this but it’s like Lenin and martov about the wording of the nrlsdp member requirements#or Robespierre and Danton

0 notes

Text

“White Russians” or two revolutionaries and a Grand Duke walk into a café

Searching for a historical parallel, the Parisian newspapers recalled the French emigration of 1791-1793, although the flight of a few thousands of aristocrats frightened by the clang of the guillotine and the eloquence of Robespierre had little in common with this exodus of over two million intellectuals and tradesmen. Not only was there no Catherine the Great in the Paris of 1919 and no palaces were thrown open to the Russian exiles but the similarity of political opinions which united the Counts and the Chevaliers gathered in Coblenz and St. Petersburg was totally absent in Passy. The French emigrants of 1791-1793 were royalists, each and every one of them, whether supporters of the future King Louis XVIII or champions of the Duc d’Orléans, while the Russian refugees of 1919 belonged to numberless political parties and hated each other much more than they did the Bolsheviks. A vast majority of them were republicans: republicans of the bourgeois type who were thinking of “liberty” in terms of a Raymond Poincare’ or a Herbert Hoover; republicans of that quasi-socialistic type which produces millionaire-lawyers in France and millionaire-publishers of radical weeklies in the United States; and finally, not a few of them belonged to the Second Internationale type of republicans and would have gladly embraced the Soviet faith had Lenin been willing to accept their collaboration. No one except a badly informed American correspondent could have classified that multicolored army as just “White Russian emigration.” Pink and reddish, green and whitish, they were all waiting for the Bolsheviks to fall so that they could go back to Russia and resume their feuds interrupted by the October Revolution. Meanwhile, they had to do their fighting in the columns of the Paris papers and on the platform of that same stuffy hall in the Rue Danton where in the early 1900’s Lenin used to denounce Plekhanoff’s fallacies. One afternoon, while sipping my apéritif on the terrace of the Café de la Tour in the Square Albany, I noticed two men who were exchanging glances of undisguised hatred. Their faces seemed familiar, greatly photographed and connected with some unpleasant memories. There was a considerable distance between their respective table and the café was crowded, yet they appeared to be interested only in each other, as if unwilling to concede defeat in this battle of looks. Both must have known me because once in a while they turned in my direction, in a manner hardly suggestive of mere curiosity. Must be Russians, I thought, and evidently my enemies, but who? I watched for a moment the elder of the two and then I had it. Savinkoff, the assassin of my cousin Grand Duke Sergei, later Minister of War in the Provisional Government, still later hired agent of the Allies in Siberia and the man for whose head the Soviets would have paid a handsome reward! I used to see is Napoleonic profile, first in the circulars of the Department of the Secret Imperial Police, then on the Bolshevik posters plastered all over Russia and inviting “all honest proletarians to shoot that contemplatable bourgeois snake on sight.” I would have recognized him at once but he had aged considerably and had grown quite fat. “Well, well,” I said to myself, “in your white spats and with that gardenia in your buttonhole you certainly could pass for a vacationing English stockbroker or a retired Monte Carlo croupier, anything but a legendary bomb-thrower. Wonder who the target of your angry stares might be? Perhaps some prominent Bolshevik on an incognito trip to France.” But nothing in the younger Russian indicated the probability of a Soviet pedigree. For one thing, he was dressed in a neat- middle-class fashion while the Moscow emissaries either neglect their appearance completely or go in for flashy ties and silk shirts. I would have taken him for a former agent provocateur o the Imperial Police who might have bothered Savinkoff in the pre-war days but then I noticed his eyes and ears. The ears were bloodless and immense. They stood up like an abnormal outgrowth of the neck. They eyes were small and watery; they reflected meanness and deceit. Mirabeau’s description of Barnave came to my mind: “Barnave, tu as les yeaux froids et fixes, il n’y a pas de divinité en toi,” and this provided the cue. The great orator of the Russian Revolution! The Prime Minister who threatened to “lock up his heart and throw the keys into the sea”! The man who refused to sanction the departure of Nicky and the Imperial Family for England and insisted on their transfer to Siberia.[*] I motioned to the waiter. “Am I right?” I asked. “That gentleman over there, is it Kerensky?” “I am sorry, Monseigneur,” was the blushing answer, “but this is a public café. Unfortunately, we must admit anyone who has the price of a cup of coffee.” He could not understand my delirious laughter. Few Frenchmen would have understood the piquancy of that scene. One had to be a Russian and live through twenty years of assassinations and uprisings in order to appreciate the subtle attire of fate. Savinkoff, Kerensky and a Grand Duke – all three on the terrace of the same third-rate café in Paris, all three in the identically same situation, unable to return to Russia, unwilling to forget the past, choking with toothless hatred, not knowing whether they would be permitted to remain in France and continue to possess the price of a cup of coffee. His was something distinctly new, something that neither the French emigrant of the 1790s’ nor the hard-bitten Stuarts had ever experienced. No Robespierre sat with the Duc d’Orléans in the latter’s unpaid-for room in a dingy inn in Philadelphia and no Cromwell rode by the side of Charles II through the muddy fields of Burgundy in search of a meal and a five-pound loan.

[*] here in this copy someone has written a five-line pencil refutation of this claim. Memoirs of Alexander Mikhailovich Romanov, published in English translation in 1933 as ‘Always a Grand Duke’ by Farrar & Rinehart, pp. 68-72.

#Russian Revolution#Alexander Mikhailovich#Alexander Kerensky#Boris Savinkov#French Revolution#history

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

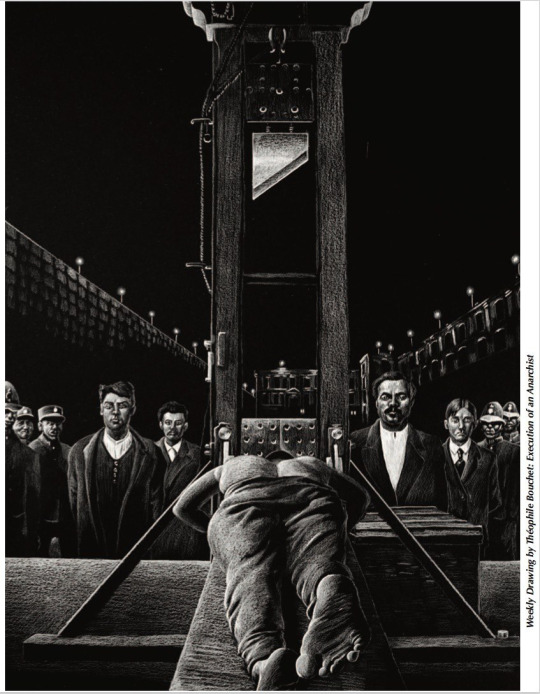

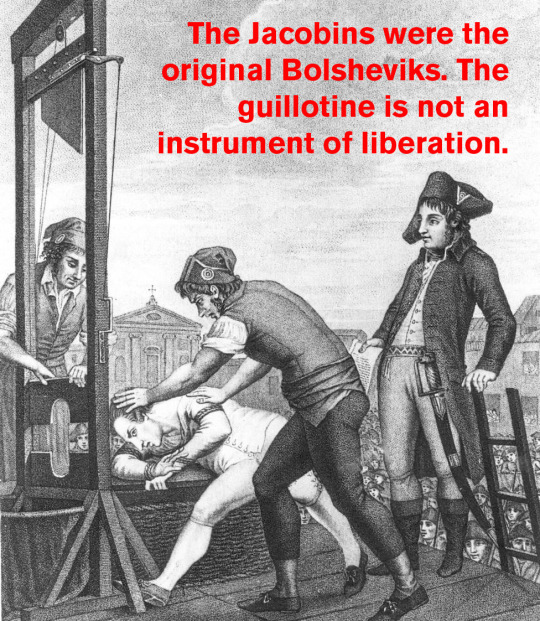

Against the Logic of the Guillotine: Why the Paris Commune Burned the Guillotine—and We Should Too

148 years ago this week, on April 6, 1871, armed participants in the revolutionary Paris Commune seized the guillotine that was stored near the prison in Paris. They brought it to the foot of the statue of Voltaire, where they smashed it into pieces and burned it in a bonfire, to the applause of an immense crowd.1 This was a popular action arising from the grassroots, not a spectacle coordinated by politicians. At the time, the Commune controlled Paris, which was still inhabited by people of all classes; the French and Prussian armies surrounded the city and were preparing to invade it in order to impose the conservative Republican government of Adolphe Thiers. In these conditions, burning the guillotine was a brave gesture repudiating the Reign of Terror and the idea that positive social change can be achieved by slaughtering people.

“What?” you say, in shock, “The Communards burned the guillotine? Why on earth would they do that? I thought the guillotine was a symbol of liberation!”

Why indeed? If the guillotine is not a symbol of liberation, then why has it become such a standard motif for the radical left over the past few years? Why is the internet replete with guillotine memes? Why does The Coup sing “We got the guillotine, you better run”? The most popular socialist periodical is named Jacobin, after the original proponents of the guillotine. Surely this can’t all be just an ironic sendup of lingering right-wing anxieties about the original French Revolution.

The guillotine has come to occupy our collective imagination. In a time when the rifts in our society are widening towards civil war, it represents uncompromising bloody revenge.

Those who take their own powerlessness for granted assume that they can promote gruesome revenge fantasies without consequences. But if we are serious about changing the world, we owe it to ourselves to make sure that our proposals are not equally gruesome.

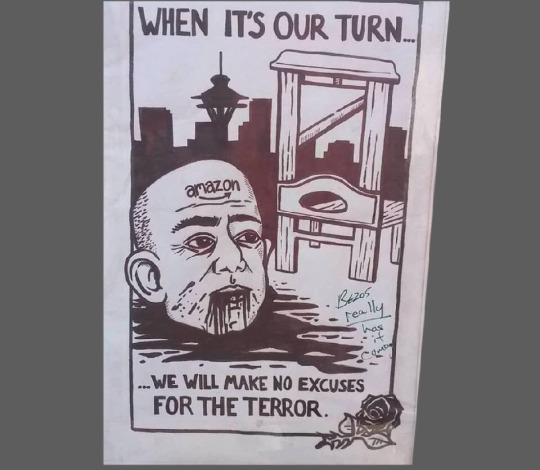

A poster in Seattle, Washington. The quotation is from Karl Marx.

Vengeance

It’s not surprising that people want bloody revenge today. Capitalist profiteering is rapidly rendering the planet uninhabitable. US Border Patrol is kidnapping, drugging, and imprisoning children. Individual acts of racist and misogynist violence occur regularly. For many people, daily life is increasingly humiliating and disempowering.

Those who don’t desire revenge because they are not compassionate enough to be outraged about injustice or because they are simply not paying attention deserve no credit for this. There is less virtue in apathy than in the worst excesses of vengefulness.

Do I want to take revenge on the police officers who murder people with impunity, on the billionaires who cash in on exploitation and gentrification, on the bigots who harass and dox people? Yes, of course I do. They have killed people I knew; they are trying to destroy everything I love. When I think about the harm that they are causing, I feel ready to break their bones, to kill them with my bare hands.

But that desire is distinct from my politics. I can want something without having to reverse-engineer a political justification for it. I can want something and choose not to pursue it, if I want something else even more—in this case, an anarchist revolution that is not based in revenge. I don’t judge other people for wanting revenge, especially if they have been through worse than I have. But I also don’t confuse that desire with a proposal for liberation.

If the sort of bloodlust I describe scares you, or if it simply seems unseemly, then you absolutely have no business joking about other people carrying out industrialized murder on your behalf.

For this is what distinguishes the fantasy of the guillotine: it is all about efficiency and distance. Those who fetishize the guillotine don’t want to kill people with their bare hands; they aren’t prepared to rend anyone’s flesh with their teeth. They want their revenge automated and carried out for them. They are like the consumers who blithely eat Chicken McNuggets but could never personally butcher a cow or cut down a rainforest. They prefer for bloodshed to take place in an orderly manner, with all the paperwork filled out properly, according to the example set by the Jacobins and the Bolsheviks in imitation of the impersonal functioning of the capitalist state.

And one more thing: they don’t want to have to take responsibility for it. They prefer to express their fantasy ironically, retaining plausible deniability. Yet anyone who has ever participated actively in social upheaval knows how narrow the line can be between fantasy and reality. Let’s look at the “revolutionary” role the guillotine has played in the past.

“But revenge is unworthy of an anarchist! The dawn, our dawn, claims no quarrels, no crimes, no lies; it affirms life, love, knowledge; we work to hasten that day.”

-Kurt Gustav Wilckens—anarchist, pacifist, and assassin of Colonel Héctor Varela, the Argentine official who had overseen the slaughter of approximately 1500 striking workers in Patagonia.

A Very Brief History of the Guillotine

The guillotine is associated with radical politics because it was used in the original French Revolution to behead monarch Louis XVI on January 21, 1793, several months after his arrest. But once you open the Pandora’s box of exterminatory force, it’s difficult to close it again.

Having gotten started using the guillotine as an instrument of social change, Maximilien de Robespierre, sometime President of the Jacobin Club, continued employing it to consolidate power for his faction of the Republican government. As is customary for demagogues, Robespierre, Georges Danton, and other radicals availed themselves of the assistance of the sans-culottes, the angry poor, to oust the more moderate faction, the Girondists, in June 1793. (The Girondists, too, were Jacobins; if you love a Jacobin, the best thing you can do for him is to prevent his party from coming to power, since he is certain to be next up against the wall after you.) After guillotining the Girondists en masse, Robespierre set about consolidating power at the expense of Danton, the sans-culottes, and everyone else.

“The revolutionary government has nothing in common with anarchy. On the contrary, its goal is to suppress it in order to ensure and solidify the reign of law.”

-Maximilien Robespierre, distinguishing his autocratic government from the more radical grassroots movements that helped to create the French Revolution.2

By early 1794, Robespierre and his allies had sent a great number of people at least as radical as themselves to the guillotine, including Anaxagoras Chaumette and the so-called Enragés, Jacques Hébert and the so-called Hébertists, proto-feminist and abolitionist Olympe de Gouges, Camille Desmoulins (who had had the gall to suggest to his childhood friend Robespierre that “love is stronger and more lasting than fear”)—and Desmoulins’s wife, for good measure, despite her sister having been Robespierre’s fiancée. They also arranged for the guillotining of Georges Danton and Danton’s supporters, alongside various other former allies. To celebrate all this bloodletting, Robespierre organized the Festival of the Supreme Being, a mandatory public ceremony inaugurating an invented state religion.3

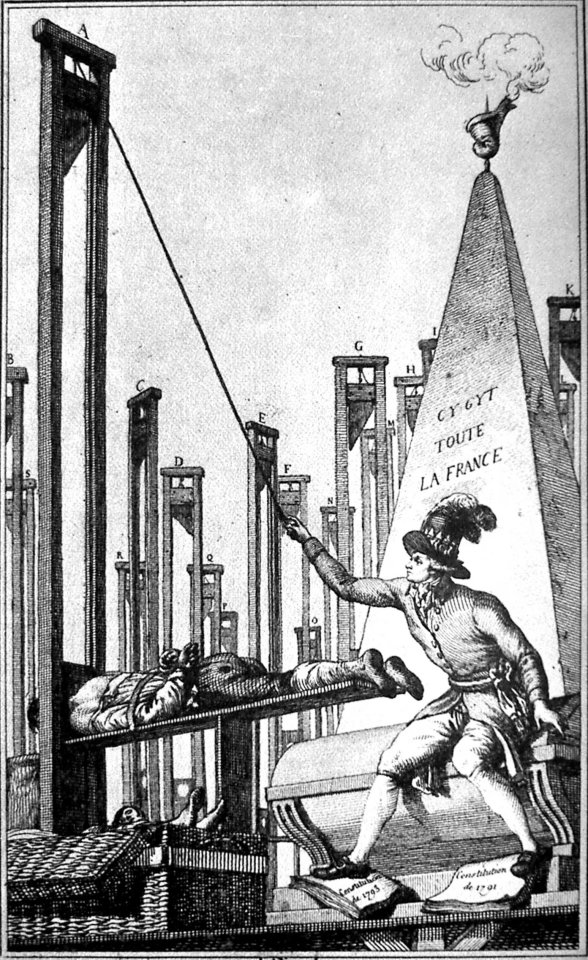

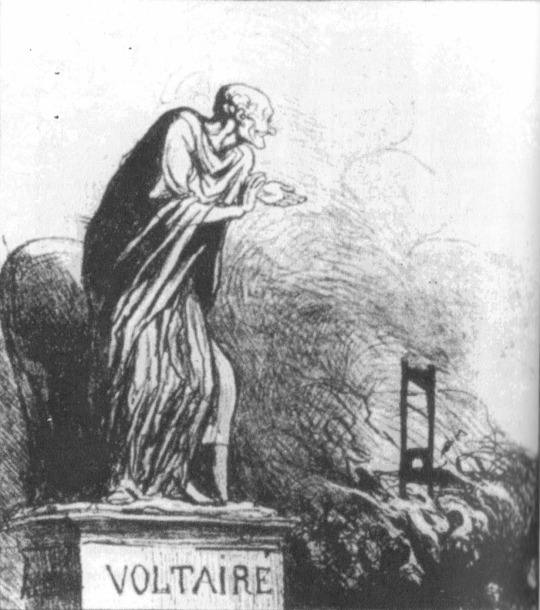

“Here lies all of France,” reads the inscription on the tomb behind Robespierre in this political cartoon referencing all the executions he helped arrange.

After this, it was only a month and a half before Robespierre himself was guillotined, having exterminated too many of those who might have fought beside him against the counterrevolution. This set the stage for a period of reaction that culminated with Napoleon Bonaparte seizing power and crowning himself Emperor. According to the French Republican Calendar (an innovation that did not catch on, but was briefly reintroduced during the Paris Commune), Robespierre’s execution took place during the month of Thermidor. Consequently, the name Thermidor is forever associated with the onset of the counterrevolution.

“Robespierre killed the Revolution in three blows: the execution of Hébert, the execution of Danton, the Cult of the Supreme Being… The victory of Robespierre, far from saving it, would have meant only a more profound and irreparable fall.”

-Louis-Auguste Blanqui, himself hardly an opponent of authoritarian violence.

But it is a mistake to focus on Robespierre. Robespierre himself was not a superhuman tyrant. At best, he was a zealous apparatchik who filled a role that countless revolutionaries were vying for, a role that another man would have played if he had not. The issue was systemic—the competition for centralized dictatorial power—not a matter of individual wrongdoing.

The tragedy of 1793-1795 confirms that whatever tool you use to bring about a revolution will surely be used against you. But the problem is not just the tool, it’s the logic behind it. Rather than demonizing Robespierre—or Lenin, Stalin, or Pol Pot—we have to examine the logic of the guillotine.

To a certain extent, we can understand why Robespierre and his contemporaries ended up relying on mass murder as a political tool. They were threatened by foreign invasion, internal conspiracies, and counterrevolutionary uprisings; they were making decisions in an extremely high-stress environment. But if it is possible to understand how they came to embrace the guillotine, it is impossible to argue that all the killings were necessary to secure their position. Their own executions refute that argument eloquently enough.

Likewise, it is wrong to imagine that the guillotine was employed chiefly against the ruling class, even at the height of Jacobin rule. Being consummate bureaucrats, the Jacobins kept detailed records. Between June 1793 and the end of July 1794, 16,594 people were officially sentenced to death in France, including 2639 people in Paris. Of the formal death sentences passed under the Terror, only 8 percent were doled out to aristocrats and 6 percent to members of the clergy; the rest were divided between the middle class and the poor, with the vast majority of the victims coming from the lower classes.

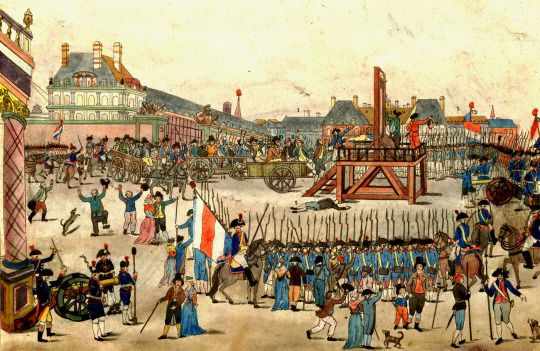

The execution of Robespierre and his colleagues. Robespierre is identified by the number 10; sitting in the cart, he holds a handkerchief to his mouth, having been shot in the jaw during his capture.

The story that played out in the first French revolution was not a fluke. Half a century later, the French Revolution of 1848 followed a similar trajectory. In February, a revolution led by angry poor people gave Republican politicians state power; in June, when life under the new government turned out to be little better than life under the king, the people of Paris revolted once again and the politicians ordered the army to massacre them in the name of the revolution. This set the stage for the nephew of the original Napoleon to win the presidential election of December 1848, promising to “restore order.” Three years later, having exiled all the Republican politicians, Napoleon III abolished the Republic and crowned himself Emperor—prompting Marx’s famous quip that history repeats itself, “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”

Likewise, after the French revolution of 1870 put Adolphe Thiers in power, he ruthlessly butchered the Paris Commune, but this only paved the way for even more reactionary politicians to supplant him in 1873. In all three of these cases, we see how revolutionaries who are intent on wielding state power must embrace the logic of the guillotine to acquire it, and then, having brutally crushed other revolutionaries in hopes of consolidating control, are inevitably defeated by more reactionary forces.

In the 20th century, Lenin described Robespierre as a Bolshevik avant la lettre, affirming the Terror as an antecedent of the Bolshevik project. He was not the only person to draw that comparison.

“We’ll be our own Thermidor,” Bolshevik apologist Victor Serge recalls Lenin proclaiming as he prepared to butcher the rebels of Kronstadt. In other words, having crushed the anarchists and everyone else to the left of them, the Bolsheviks would survive the reaction by becoming the counterrevolution themselves. They had already reintroduced fixed hierarchies into the Red Army in order to recruit former Tsarist officers to join it; alongside their victory over the insurgents in Kronstadt, they reintroduced the free market and capitalism, albeit under state control. Eventually Stalin assumed the position once occupied by Napoleon.

So the guillotine is not an instrument of liberation. This was already clear in 1795, well over a century before the Bolsheviks initiated their own Terror, nearly two centuries before the Khmer Rouge exterminated almost a quarter of the population of Cambodia.

Why, then, has the guillotine come back into fashion as a symbol of resistance to tyranny? The answer to this will tell us something the psychology of our time.

Fetishizing the Violence of the State

It is shocking that even today, radicals would associate themselves with the Jacobins, a tendency that was reactionary by the end of 1793. But the explanation isn’t hard to work out. Then, as now, there are people who want to think of themselves as radical without having to actually make a radical break with the institutions and practices that are familiar to them. “The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living,” as Marx said.

If—to use Max Weber’s famous definition—an aspiring government qualifies as representing the state by achieving a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory, then one of the most persuasive ways it can demonstrate its sovereignty is to wield lethal force with impunity. This explains the various reports to the effect that public beheadings were observed as festive or even religious occasions during the French Revolution. Before the Revolution, beheadings were affirmations of the sacred authority of the monarch; during the Revolution, when the representatives of the Republic presided over executions, this confirmed that they held sovereignty—in the name of The People, of course. “Louis must die so that the nation may live,” Robespierre had proclaimed, seeking to sanctify the birth of bourgeois nationalism by literally baptizing it in the blood of the previous social order. Once the Republic was inaugurated on these grounds, it required continuous sacrifices to affirm its authority.

Here we see the essence of the state: it can kill, but it cannot give life. As the concentration of political legitimacy and coercive force, it can do harm, but it cannot establish the kind of positive freedom that individuals experience when they are grounded in mutually supportive communities. It cannot create the kind of solidarity that gives rise to harmony between people. What we use the state to do to others, others can use the state to do to us—as Robespierre experienced—but no one can use the coercive apparatus of the state for the cause of liberation.

For radicals, fetishizing the guillotine is just like fetishizing the state: it means celebrating an instrument of murder that will always be used chiefly against us.

Those who have been stripped of a positive relationship to their own agency often look around for a surrogate to identify with—a leader whose violence can stand in for the revenge they desire as a consequence of their own powerlessness. In the Trump era, we are all well aware of what this looks like among disenfranchised proponents of far-right politics. But there are also people who feel powerless and angry on the left, people who desire revenge, people who want to see the state that has crushed them turned against their enemies.

Reminding “tankies” of the atrocities and betrayals state socialists perpetrated from 1917 on is like calling Trump racist and sexist. Publicizing the fact that Trump is a serial sexual assaulter only made him more popular with his misogynistic base; likewise, the blood-drenched history of authoritarian party socialism can only make it more appealing to those who are chiefly motivated by the desire to identify with something powerful.

-Anarchists in the Trump Era

Now that the Soviet Union has been defunct for almost 30 years—and owing to the difficulty of receiving firsthand perspectives from the exploited Chinese working class—many people in North America experience authoritarian socialism as an entirely abstract concept, as distant from their lived experience as mass executions by guillotine. Desiring not only revenge but also a deus ex machina to rescue them from both the nightmare of capitalism and the responsibility to create an alternative to it themselves, they imagine the authoritarian state as a champion that could fight on their behalf. Recall what George Orwell said of the comfortable British Stalinist writers of the 1930s in his essay “Inside the Whale”:

“To people of that kind such things as purges, secret police, summary executions, imprisonment without trial etc., etc., are too remote to be terrifying. They can swallow totalitarianism because they have no experience of anything except liberalism.”

Punishing the Guilty

“Trust visions that don’t feature buckets of blood.”

-Jenny Holzer

By and large, we tend to be more aware of the wrongs committed against us than we are of the wrongs we commit against others. We are most dangerous when we feel most wronged, because we feel most entitled to pass judgment, to be cruel. The more justified we feel, the more careful we ought to be not to replicate the patterns of the justice industry, the assumptions of the carceral state, the logic of the guillotine. Again, this does not justify inaction; it is simply to say that we must proceed most critically precisely when we feel most righteous, lest we assume the role of our oppressors.

When we see ourselves as fighting against specific human beings rather than social phenomena, it becomes more difficult to recognize the ways that we ourselves participate in those phenomena. We externalize the problem as something outside ourselves, personifying it as an enemy that can be sacrificed to symbolically cleanse ourselves. Yet what we do to the worst of us will eventually be done to the rest of us.

As a symbol of vengeance, the guillotine tempts us to imagine ourselves standing in judgment, anointed with the blood of the wicked. The Christian economics of righteousness and damnation is essential to this tableau. On the contrary, if we use it to symbolize anything, the guillotine should remind us of the danger of becoming what we hate. The best thing would be to be able to fight without hatred, out of an optimistic belief in the tremendous potential of humanity.

Often, all it takes to be able to cease to hate a person is to succeed in making it impossible for him to pose any kind of threat to you. When someone is already in your power, it is contemptible to kill him. This is the crucial moment for any revolution, the moment when the revolutionaries have the opportunity to take gratuitous revenge, to exterminate rather than simply to defeat. If they do not pass this test, their victory will be more ignominious than any failure.

The worst punishment anyone could inflict on those who govern and police us today would be to compel them to live in a society in which everything they’ve done is regarded as embarrassing—for them to have to sit in assemblies in which no one listens to them, to go on living among us without any special privileges in full awareness of the harm they have done. If we fantasize about anything, let us fantasize about making our movements so strong that we will hardly have to kill anyone to overthrow the state and abolish capitalism. This is more becoming of our dignity as partisans of liberation.

It is possible to be committed to revolutionary struggle by all means necessary without holding life cheap. It is possible to eschew the sanctimonious moralism of pacifism without thereby developing a cynical lust for blood. We need to develop the ability to wield force without ever mistaking power over others for our true objective, which is to collectively create the conditions for the freedom of all.

“That humanity might be redeemed from revenge: that is for me the bridge to the highest hope and a rainbow after lashing storms.”

-Friedrich Nietzsche (not himself a partisan of liberation, but one of the foremost theorists of the hazards of vengefulness)

Communards burning the guillotine as a “servile instrument of monarchist domination” at the foot of the statue of Voltaire in Paris on April 6, 1871.

Instead of the Guillotine

Of course, it’s pointless to appeal to the better nature of our oppressors until we have succeeded in making it impossible for them to benefit from oppressing us. The question is how to accomplish that.

Apologists for the Jacobins will protest that, under the circumstances, at least some bloodletting was necessary to advance the revolutionary cause. Practically all of the revolutionary massacres in history have been justified on the grounds of necessity—that’s how people always justify massacres. Even if some bloodletting were necessary, that it is still no excuse to cultivate bloodlust and entitlement as revolutionary values. If we wish to wield coercive force responsibly when there is no other choice, we should cultivate a distaste for it.

Have mass killings ever helped us advance our cause? Certainly, reactionaries throughout history have disingenuously held revolutionaries to a double standard, forgiving the state for murdering civilians by the million while taking insurgents to task for so much as breaking a window. But as we seek transformation rather than conquest, we should appraise our victories according to a different logic than the police and militaries we confront.

This is not an argument against the use of force. Rather, it is a question about how to employ it without creating new hierarchies, new forms of systematic oppression.

A taxonomy of revolutionary violence.

The image of the guillotine is propaganda for the kind of authoritarian organization that can avail itself of that particular tool. Every tool implies the forms of social organization that are necessary to employ it. In his memoir, Bash the Rich, Class War veteran Ian Bone quotes Angry Brigade member John Barker to the effect that “petrol bombs are far more democratic than dynamite,” suggesting that we should analyze every tool of resistance in terms of how it structures power. Critiquing the armed struggle model adopted by hierarchical authoritarian groups in Italy in the 1970s, Alfredo Bonanno and other insurrectionists emphasized that liberation could only be achieved via horizontal, decentralized, and participatory methods of resistance.

“It is impossible to make the revolution with the guillotine alone. Revenge is the antechamber of power. Anyone who wants to avenge themselves requires a leader. A leader to take them to victory and restore wounded justice.”

-Alfredo Bonanno, Armed Joy

Together, a rioting crowd can defend an autonomous zone or exert pressure on authorities without need of hierarchical centralized leadership. Where this becomes impossible—when society has broken up into two distinct sides that are fully prepared to slaughter each other via military means—one may no longer speak of revolution, but only of war. The premise of revolution is that subversion can spread across the lines of enmity, destabilizing fixed positions, undermining the allegiances and assumptions that underpin authority. We should never hurry to make the transition from revolutionary ferment to warfare. Doing so usually forecloses possibilities rather than expanding them.

As a tool, the guillotine takes for granted that it is impossible to transform one’s relations with the enemy, only to abolish them. What’s more, the guillotine assumes that the victim is already completely within the power of the people who employ it. By contrast with the feats of collective courage we have seen people achieve against tremendous odds in popular uprisings, the guillotine is a weapon for cowards.

By refusing to slaughter our enemies wholesale, we hold open the possibility that they might one day join us in our project of transforming the world. Self-defense is necessary, but wherever we can, we should take the risk of leaving our adversaries alive. Not doing so guarantees that we will be no better than the worst of them. From a military perspective, this is a handicap; but if we truly aspire to revolution, it is the only way.

Liberate, not Exterminate

“To give hope to the many oppressed and fear to the few oppressors, that is our business; if we do the first and give hope to the many, the few must be frightened by their hope. Otherwise, we do not want to frighten them; it is not revenge we want for poor people, but happiness; indeed, what revenge can be taken for all the thousands of years of the sufferings of the poor?”

-William Morris, “How We Live and How We Might Live”

So we repudiate the logic of the guillotine. We don’t want to exterminate our enemies. We don’t think the way to create harmony is to subtract everyone who does not share our ideology from the world. Our vision is a world in which many worlds fit, as Subcomandante Marcos put it—a world in which the only thing that is impossible is to dominate and oppress.

Anarchism is a proposal for everyone regarding how we might go about improving our lives—workers and unemployed people, people of all ethnicities and genders and nationalities or lack thereof, paupers and billionaires alike. The anarchist proposal is not in the interests of one currently existing group against another: it is not a way to enrich the poor at the expense of the rich, or to empower one ethnicity, nationality, or religion at others’ expense. That entire way of thinking is part of what we are trying to escape. All of the “interests” that supposedly characterize different categories of people are products of the prevailing order and must be transformed along with it, not preserved or pandered to.

From our perspective, even the topmost positions of wealth and power that are available in the existing order are worthless. Nothing that capitalism and the state have to offer are of any value to us. We propose anarchist revolution on the grounds that it could finally fulfill longings that the prevailing social order will never satisfy: the desire to be able to provide for oneself and one’s loved ones without doing so at anyone else’s expense, the wish to be valued for one’s creativity and character rather than for how much profit one can generate, the longing to structure one’s life around what is profoundly joyous rather than according to the imperatives of competition.

We propose that everyone now living could get along—if not well, then at least better—if we were not forced to compete for power and resources in the zero-sum games of politics and economics.

Leave it to anti-Semites and other bigots to describe the enemy as a type of people, to personify everything they fear as the Other. Our adversary is not a kind of human being, but the form of social relations that imposes antagonism between people as the fundamental model for politics and economics. Abolishing the ruling class does not mean guillotining everyone who currently owns a yacht or penthouse; it means making it impossible for anyone to systematically wield coercive power over anyone else. As soon as that is impossible, no yacht or penthouse will sit empty long.

As for our immediate adversaries—the specific human beings who are determined to maintain the prevailing order at all costs—we aspire to fight against them without seeking to exterminate them. However selfish and rapacious they appear, at least some of their values are similar to ours, and most of their errors—like our own—arise from their fears and weaknesses. In many cases, they oppose our proposals precisely because of what is internally inconsistent in them—for example, the idea of bringing about the fellowship of humanity by means of violent coercion. Were it not for the genuinely egregious things that have been done in the name of liberation, our enemies would have much weaker arguments against it.

Even when we are engaged in pitched physical struggles with our adversaries, we ought to maintain a profound faith in their potential, for we hope to live in different relations with them one day. As aspiring revolutionaries, this hope is our most precious resource, the foundation of everything we do. If revolutionary transformation is to spread throughout society and across the world, those we fight today will have to be fighting alongside us tomorrow. We do not preach conversion by the sword, nor do we imagine that we will persuade our adversaries in some abstract marketplace of ideas; rather, we aim to interrupt the ways that capitalism and the state currently reproduce themselves while demonstrating the virtues of our alternative inclusively and contagiously. There are no shortcuts when it comes to revolution.

Precisely because it is sometimes necessary to employ force in our conflicts with those who preserve the prevailing order, it is especially important that we never lose sight of our aspirations, our compassion, and our optimism. When we are compelled to use coercive force in the struggle, the only possible justification for doing so is that it is a necessary step towards creating a better world for everyone—including our enemies, or at least their children. Otherwise, we risk becoming the next ones to operate the guillotine.

“The only real revenge we could possibly have would be by our own efforts to bring ourselves to happiness.”

-William Morris, in response to calls for revenge for police attacks on demonstrations in Trafalgar Square

Voltaire applauding the burning the guillotine during the Paris Commune.

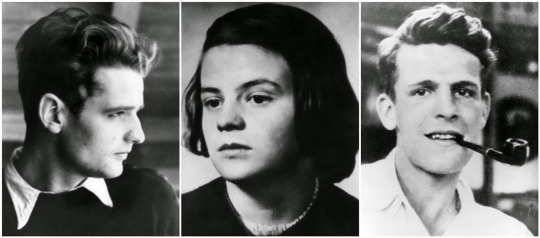

Appendix: The Beheaded

The guillotine did not end its career with the conclusion of the first French Revolution, nor when it was burned during the Paris Commune. In fact, it was used in France as a means for the state to carry out capital punishment right up to 1977. One of the last women guillotined in France was executed for providing abortions. The Nazis guillotined about 16,500 people between 1933 and 1945—the same number of people killed during the peak of the Terror in France.

A few victims of the guillotine:

Ravachol (born François Claudius Koenigstein), anarchist

Auguste Vaillant, anarchist

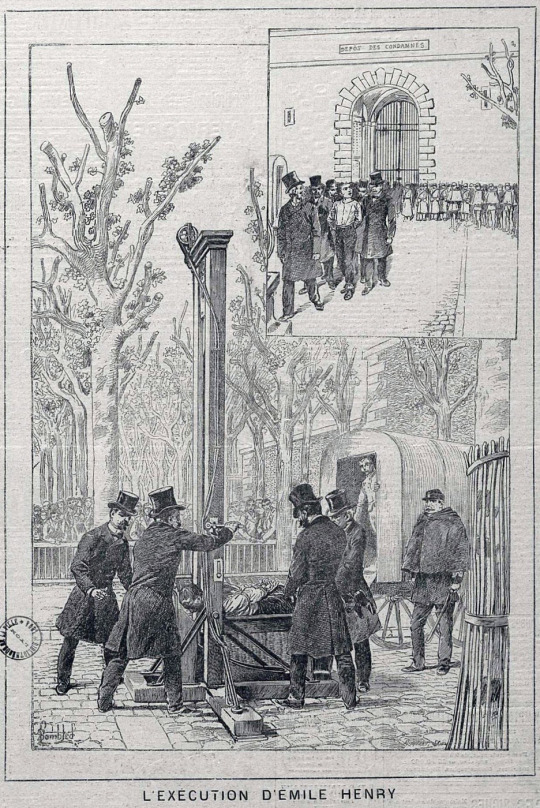

Emile Henry, anarchist

Sante Geronimo Caserio, anarchist

Raymond Caillemin, Étienne Monier and André Soudy, all anarchist participants in the so-called Bonnot Gang

Mécislas Charrier, anarchist

Felice Orsini, who attempted to assassinate Napoleon III

Hans and Sophie Scholl and Christoph Probst—members of Die Weisse Rose, an underground anti-Nazi youth organization active in Munich 1942-1943.

Emile Henry.

Sante Geronimo Caserio.

André Soudy, Edouard Carouy, Octave Garnier, Etienne Monier.

Hans and Sophie Scholl and Christoph Probst.

“I am an anarchist. We have been hanged in Chicago, electrocuted in New York, guillotined in Paris and strangled in Italy, and I will go with my comrades. I am opposed to your Government and to your authority. Down with them. Do your worst. Long live Anarchy.”

-Chummy Fleming

Further Reading

The Guillotine At Work, GP Maximoff

As reported in the official journal of the Paris Commune:

“On Thursday, at nine o’clock in the morning, the 137th battalion, belonging to the eleventh arrondissement, went to Rue Folie-Mericourt; they requisitioned and took the guillotine, broke the hideous machine into pieces, and burned it to the applause of an immense crowd.

“They burned it at the foot of the statue of the defender of Sirven and Calas, the apostle of humanity, the precursor of the French Revolution, at the foot of the statue of Voltaire.”

This had been announced earlier in the following proclamation:

“Citizens,

“We have been informed of the construction of a new type of guillotine that was commissioned by the odious government [i.e., the conservative Republican government under Adolphe Thiers]—one that it is easier to transport and speedier. The Sub-Committee of the 11th Arrondissement has ordered the seizure of these servile instruments of monarchist domination and has voted that they be destroyed once and forever. They will therefore be burned at 10 o’clock on April 6, 1871, on the Place de la Mairies, for the purification of the Arrondissement and the consecration of our new freedom.” ↩

As we have argued elsewhere, fetishizing “the rule of law” often serves to legitimize atrocities that would otherwise be perceived as ghastly and unjust. History shows again and again how centralized government can perpetrate violence on a much greater scale than anything that arises in “unorganized chaos.” ↩

Nauseatingly, at least one contributor to Jacobin magazine has even attempted to rehabilitate this precursor to the worst excesses of Stalinism, pretending that a state-mandated religion could be preferable to authoritarian atheism. The alternative to both authoritarian religions and authoritarian ideologies that promote Islamophobia and the like is not for an authoritarian state to impose a religion of its own, but to build grassroots solidarity across political and religious lines in defense of freedom of conscience. ↩

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

I agree with @mali-umkin.

I have an issue with the reaction of Paul Chopelin and Jean-Clément Martin. It's good to present historical facts, but when I'm looking to the tweetstroms from Mathilde Larrere, historian specialized in revolutionary movements, their speech seem to be an answer that lacks analysis of current events.

Larrere often analyzes modern social movements, she understands that the revolution still feeds the collective imagination today. She has shown this many time in particular with the Yellow Vests movement.

By the way, this is not the first time that Chopelin criticizes the use of Robespierre by the left. He did the same thing last July 14th when Robespierre was trending on Twitter. But I think that Chopelin and Martin, in their fed up with the lack of historical rigor of politicians, have lacked this same scientific rigor. They failed or unwilling to elevate the debate. They only presents facts.

Here are some things they could have talked about :

The figure of Robespierre was already controversial when he was still alive. He was so adored and so hated that at the end of his life he was beaten by his own legend. Could suggest consulting Leuwers' work, their collegue, on the Robespierre myth.

Using figures in politics has always existed and served a political purpose, even during the revolution. Jacques Roux presented himself as 'Marat's heir', to prove his closeness with the sans-culottes, even if they didn't have the same political opinions about economy.

To the left, revolution and Robespierre are spoils of war and rightful examples. Babeuf inspired communism. Lenin was inspired by the Jacobin governance but remains very critical because it was too bourgeois. Louise Michel loves Saint-Just.

If politicians lacks of rigor, historians are NEVER neutral. The historiography of the revolution proves it. Mathiez and Aulard argued because one defended Danton while the other defended Robespierre. Does a bias prevent a rigorous work ? Mathiez' analysis of Danton's accounts to prove that he was corrupt shows it doesn't.

Highlight the problem of the follow-up of the school institutions in relation to the progress of the historical works. We got stuck in 1989, because it was the last time that there were historiographical debates on television accessible to the general public. There was a cultural battle between Michel Vovelle and François Furet during the bicentenary. Today, television is slowly starting to give more decent documentaries (I'm talking about the documentary where the revolutionaries are interviewed) but it still far behind. On the internet, we can congratulate 'Nota Bene' and 'Histony' for having done a work respecting at best the recent works.

I would end with the question that neither of them asks : why does the French left still use Robespierre today ?

=> Because the end of the Soviet bloc and socialists making liberal politics destroyed the collective imagination of the left. The USSR put an end to the possibility of an alternative society with communism. Capitalism won. And the french socialist party, allying itself with liberalism, reinforced the idea there was no alternative to capitalism. If the left wants to win, it must rebuild an imaginary that speaks to all, even to minorities.

This is what Antoine Leaument is trying to do. It's to say "we, our France, we want it to be anti-colonial, born from the constitution of 1793, this France that abolished slavery".

In her latest interview with Dany and Raz, Houria Bouteldja, spokeswoman for the Indigenous of the Republic, thinks using French revolution and Robespierre inside the collective imagination of the left is a good start (1:14:47-1:15:52).

And what better start to use the one who once said "Let's perish our colonies !" ? 😏

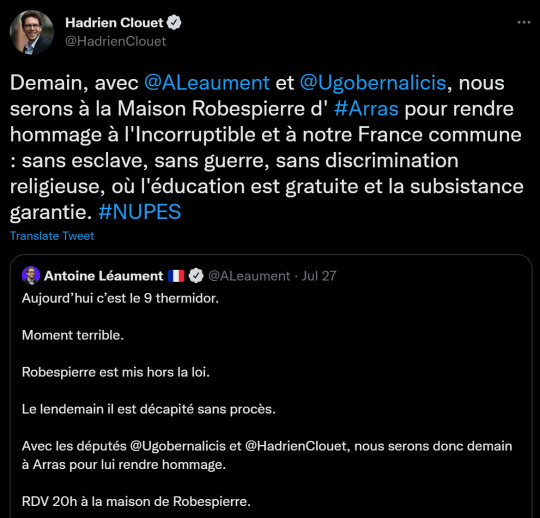

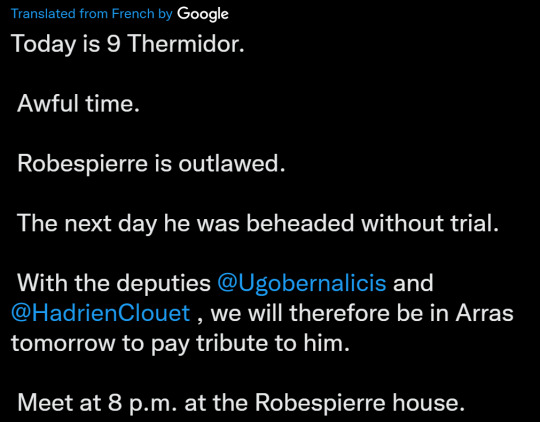

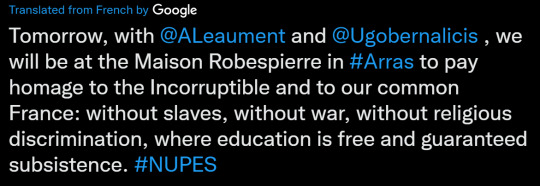

Apparently there’s controversy in France over 3 deputies from NUPES going to Arras to pay tribute to Robespierre on 9 Thermidor

Reaction from Macron’s Minister of Transport:

And this…what the hell is this

And then a Frev historian made this whole thread where he was like “yeah Robespierre has been unfairly slandered and said some good things but he was also a conspiracy theorist”:

To be very fair to him the rest of his thread is pretty firmly neutral on Robespierre but unfortunately most people who read the thread were just like YEAH YOU TELL THEM!!! ROBESPIERRE WAS TERRIBLE!!!

anyway french politics is a whole ass mess it seems

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Resistance: Chapter 1

*disclaimer I apologize in andvance for these character intros they are super similar to other character intros in an other story but I pronise the characters branch out* Chapter 1: An Introduction to the Activists It is said that spring is the time of rebirth but if it is why do we start our years in winter, why are world leaders elected in fall, and why do revolutions take place in summer. That was the question set to ponder on the chilly February day. It was a gray day the kind of sent to remind you that it was still winter and not yet growing warm. The icy sheets of rain had let up just long enough for people to walk from their homes or for tourists to spend time outside. This February day was quite different from any other cold almost spring days for today was valentine’s day, a day for love to prosper but the world then was filled with hate, pure hate. Love, now that was needed and sadly that was in very short supply. The people of the United States had trouble with loving anything for too long. They had trouble loving each other.

Down the street in the village below the Georgetown campus was a coffee shop and above that coffee shop was a loft of sorts in that loft was a pretty sight there was a tubby wood burning stove in the corner that everyone worried would cause a fire. It was packed with students well, packed might have been an exaggeration. It held at least fifteen people today. The room was used by no one most of the time but when it was being used it was being used by a group of students. They were loud and could be heard out the well lit window on summer nights but during days like these the window was locked shut and sound did not leave the room. Everyone was silent. Their heads bowed over something, for some home work for others it was personal project, and for the majority it was publications for a newspaper/web news site. ‘The Activist Paper’ as it was known on campus. It was actually called The Student Sentinel. It was a collection of bipartisan articles, even though all of the people who wrote the newspaper were liberal shmiberals.

The newspaper was not the only export of the room. This room was like the tavern where the sons of liberty met, like the salons where the Jacobins discussed the happenings of Paris, The Play Royale, it was where the great liberating minds of the times met. That room was, pardon my reference, the room where it happened. In it was the planning of rebellion in a time where everyone wanted to rebel against the government they felt was looming on becoming oppressive. The group was known by many names. There official name was the Coalition of the Friends of the Discriminated. They were more commonly known as The Activists of DC. The DCs as they were referred to in casual conversation, much to the displeasure of one of the two leaders . The room had six booths three on each wall of the rectangular room on the other side of the room was a few wooden tables in chairs. The members sat quietly in a thick tension between the two leaders in the room.

The first was Gabriel Saint Louis, otherwise known as Gabe. Gabriel was a beautiful young man whose charm and charisma lured even the most hesitant in yet he was neither warm nor patient. He could be terrible in many ways. Gabriel however fair of appearance, had no tolerance for anything that stood in his way. The 22 year old Political Science major’s pure blue eyes never seemed to be completely present they often seemed to be looking at something that only he could see. In them you could the history of the men like him before him, you could see Robespierre, Adams, Washington, Hamilton, Lenin, and Danton. You could see the desire for revolution that lurked in the heart of the handsome Gabriel. His blonde curls fell onto his tan forehead above his puppy dog ice blue eyes. Though he had men and women thrusting themselves at him constantly he rarely noticed them. Gabe was not looking for someone to love, he was looking for people to help him make a change. His atypical behavior had gained discussion around the room and the campus. He was the priest, the saint, the protector of the revolutionary flame, the priest of the movement.

The other leader sat slammed in a booth. That was Mathilde Brennan-Boivin. Mathilde, or as her friends knew her Mat, was ruthless and strong but she unlike Gabe had patience, she had a human level of compassion. She was stunning as Gabriel but unlike him she used her beauty. Her fair appearance was used to seduce the best minds even if she didn’t sleep with them, they still were drawn to her. She shone like a beacon of light to all the activists. Her passion was evident and it inspired everyone including the Patron Saint of the movement Gabriel, even though he would never admit it. Mathilde looked very different from Gabriel. She had green gray blue eyes that reminded one of an ocean in a storm and that was what was in her eyes a coming storm, a flickering flame, that light and power showed through;those eyes could cut you like knives or welcome you like an old friend. Mathilde had both sides in her character. Her dark hair was often worn down hanging around her pale face and onto her shoulders. The black curls that hung around her face gave her a further air of mystery. Her face had a cold look to it. Despite her smiling eyes, her high cheek bones, danity, slightly upturned button nose and the way the corners of the her lips always found a down turned position. That gave her the look of Gabe, that look of unadulterated devotion and cold emotions. Mathilde was not the saint or the nun of the ideals. She, like Saint Just, really embodied them; she represented what the idea of revolution was. Mathilde was ruthless and could be cold. Passion burnt in her eyes. She also had compassion for the people who were the most vulnerable. Most importantly, Mathilde, like the enticing flame of revolution, drew great people to her. She and Gabriel were more similar than they liked to admit. Gabe and Mathilde challenged each other. They had no reason to the both of them were equally as worthy as the leadership position. However both had a strange want for each other. The man devoted to his ideals and the woman who embodied them.

Mathilde slapped a sleeping man next to her. It was her adopted brother Jared. Where Mathilde had this passion and conviction to her belief in her ideals Jared lacked; he had beliefs but he had not the desire to fight for them like his younger sister.

Jared was handsome and charming when sober but when not he was crude and brash. He drank often more than his precious little sister wanted him to. Jared had a deep love of his sister and felt the one of the few things he was good at was protecting her from the dangers of life, when he was not high or intoxicated. The alcohol and drugs were driven by some degree of self loathing. Jared had deep affection toward his sister but he had none for himself. Jared sat up quickly and looked at his little sister. He looked sloppy, with his maroon t-shirt covered by stains. His sweatshirt lay on the table as a pillow. Jared’s dark curls were oily and slightly matted but he hid it extremely well with a beanie. His face had a thin layer of stubble around it and although he got more than 8 hours of sleep each day his blue eyes resembled someone who had not slept for days. Dark ikea bags outlined the bottom of his bloodshot eyes. Jared shared an apartment with Mathilde. They often said it was them against the world. Their parents not very attentive to Jared and over attentive to Mathilde their perfect baby girl that did not come from them. Jared was five when Mat was adopted. Mathilde was still an infant when she had been adopted. Jared had vowed that day to protect his little sister to always be there for her. To do her hair, to help her with anything from dancing to homework. That was his purpose.

He had met Gabriel Saint Louis in his Senior year. He had been given the task of showing the kid around campus but he and Gabriel never became great friends. However, he was the first person to dwell in this back room; he had brought Gabe here on their first day of showing him around. Well, he brought Gabriel, and Gabe’s two friends Christopher and Conrad. It was his way of showing them the hotspots. The trio had planted roots here and the boy who had showed them never really left. Jared graduated stayed to get his masters and let his little sister move in with him. It was better this way he could keep her safer in general.

Christopher Wiatt sat next to Gabriel reading, simply reading. Christopher was Logos in the equation of the group. He was logical, calm, cool, and collected. His face was fair and prone to reddening when frustrated. He had black rectangular glasses that framed his sapphire eyes, eyes that seemed deeper than the darkest ocean. The boy was quieter but inquisitive. He troubled his head with Marx, Locke, Voltaire, Rousseau, Plato, and Proudhon. Enjoying reading them and sharing what had learned with other especially Gabe and Conrad. Chris did not have many friends but with Gabe and Conrad he could be himself and even though he was dreadfully awkward and quiet Conrad and Gabe sure weren’t. Christopher combed his sandy hair out of the way of his glasses. He ought to get it cut; he hated when it got past his glasses. It became a nuisance then. Christopher dwelled in a collection of cardigans, sweater vests, and geeky t-shirts. His dorky smile perpetuated his asserted nerdiness. He was the proofreader of all articles, he was also the official organizer of the group. Mathilde, Gabriel, and Conrad were not always the most organized of people no matter their other stunning qualities. Chris liked binders and spred sheets, he also liked folders, those were just a few of his favorite methods of organization. The tall nerdy boy was the essential, he was the coolant. When everything went up in flames he put them out, with them help of Conrad, sometimes. Conrad and Christopher had been friends first. Gabe had moved to their street when he was 10. They quickly gained the title the three musketeers.

Conrad the final member of the trifecta sat trying his hardest to make Chris laugh. It wasn’t working extremely well. Conrad was the only one who seemed to have some humanity in him. He was not socially awkward like Chris nor was he unreasonably harsh like Gabe. Conrad was charismatic because he connected with people. He was extremely emotionally intelligent and was an emotional sponge. Conrad had a warm smile that he often wore to show that unlike his friends, one of whom did not give a shit about you unless you were holding a demonstration, he was a normal human. Conrad cared, he cared for every single person on the planet. His heart was always in the right even though sometimes he went too far with his antics. Conrad had a knack for trying to set couples up and it seemed to everyone a massive waste of time, everyone was mostly Chris, Laurent, Gabe, and Mathilde. Jared didn’t mind. Hell he liked seeing his friends being shoved at each other as the Beatles song “All You Need Is Love” played in the background. It was only when he tried to set Mathilde up when Jared freaked out. His sister would never, ever date someone in this God forsaken little group.

Conrad was now pulling up the front of his swooshy brown hair off his forehead and trying to make it into a horn shape. Chris was still refusing to break. Conrad’s warm bright brown eyes crossed as he looked as his nose that was wrinkled in frustration. He always looked very nice and presentable. Not in the nerdy Christopher way, but in his very own way. Conrad liked sweaters, he liked flannels, and he liked patterned button ups the most. Today he was wearing a navy blue button up with white polka dots. He was also a sucker for expensive shoes. If you looked inside the boys closet you would find that he had stashed away at least 20 pairs of shoes. Today he had gone with his black shiny doc martins with the sunshine yellow laces. They thumped on the floor. Conrad had for a long time been the tallest in the group until Gabe and then finally Chris shot up to tower above him. He liked that the doc martins gave him a little height so he did not seem so small besides his friends. Though anyone standing besides Gabe looked small no matter if they were a giant. Conrad was still trying to get Chris to laugh still no luck. He was confusing the hell out of his cousin Laurent though.

Laurent was sitting next to the other female in the room. The other female was named Esmeralda but her introduction is coming latter. Laurent was Conrad’s cousin and a friend to the rest of the group. He was lanky but not unattractive; he had that artsy slim look going for him. He was a shameless freckle face with jade green eyes and blonde hair. Laurent was naive, he had grown up in the bourgeois suburbs in Southern California. His mother and father took great care to protect him from reality. It was this naivety that made him valued. His innocence and his wide eyed enthusiasm. It was hard for him to be independent. He was glad to have Conrad as a faithful cousin to help him get adjusted to life outside of his immediate family’s thumb. Laurent had come into his own though. He had made friends with everyone in that room. Esmerelda fiddled with the collar of his green dress shirt as he smiled fondly at the pretty girl leaning into him.

Esmeralda, or Essie, was a beautiful girl. She was a lovely thing with soft brown eyes and chocolate curls a top tanned skin. Esmeralda was slim and elegant with a bit of shape to her. Her name had been taken from a Victor Hugo novel, by her mother, a professor of French literature. Esmeralda was not as passionate about the cause as Mathilde was but she was a believer in what the people in that room stood for. Essie was from a family that wanted their daughter to experience everything. So she did. Esmeralda Keeper had seen wealth and poverty, sickness and health, death and life, despair and joy, and so much more. It was what gave her, her character. Esmeralda was witty and sassy but she was also a bit prone to jealousy. Not that it ever showed. Emeralda was a beautiful girl often covered by some hand made garment. She made her own clothing most of the time using scraps from her own and goodwill. She also helped run a cute bohemian clothing shop. Esmeralda often wore these unique colored clothing and one eye catching piece, today it was a light pink silk scarf with cherry blossoms on it. Her eyes were often framed by white eyeshadow and dramatically winged eyeliner. She was beautiful. Laurent whispered something into her ear causing her to smile. Laurent Morel had met Esmeralda when Essie was still sixteen. They had become friends. Esmeralda often worked as her mother’s errand boy. Laurent knew who her as the girl who dressed in patches and walked around campus barefoot. She had helped him get to his classes on time, sadly Laurent’s sense of direction was lacking. They did not really become friends until after Esmeralda joined the ranks of a college student. It had been just recently that Laurent and Esmeralda had decided to date. Everyone agreed that Essie was perfect for Laurent.

The final booth was louder than the others. Laying basically on the table was Jakub. Jakub was mixed race his father was Polish and his mother was African American. They had raised him in an apartment in New York city and with a deep love of history. Jakub was not quiet about his adoration for history in general. His frequent trips to the UN also gave him an immense interest in foreign policy making him a champion in Model United Nations club as a kid. He was reaching for the letter from his mother that Blaise had taken from him.

Blaise was a flame haired boy with a calm yet slightly intense demeanor. Blaise was a football player and all in all tough. He was intense, very intense, when it came to the cause or anything else in life. He was like drinking hard alcohol from a shot glass intense. His attitude was generally pretty positive and people generally liked him.

Next to him, was a man name Jehan. Jehan Hugo was small in stature and a very pretty person. He was the kind of person who could pass as a beautiful girl if he really wanted too. Jehan liked all sorts of things most importantly he liked the arts. He worked part time in the gift shop at the main art museum at the mall. He and Esmeralda often shared clothing pieces and was very fond of her scarves. His hair and face always looked perfect. He had taken to the trend of drawing on freckles to his face and his own trend of purple guy liner. It looked great to everyone though no one dare admit they wished they could pull off little eyeliner hearts under the corners of their eyes.

The final boy was named Felix and he was the kind of person with a sweet demeanor about him. He had orange hair and sparkling green eyes that showed a level of insight. He seemed the kind of person who should wear glasses although he never did. Felix studied medicine with Chris here on campus. Felix took it much more serious when it came to implementing that training into practice his christmas gift to everyone was hand sanitizers from bath and body works. He also took it open himself to be the human dispenser of advil and cold medicine. He even carried around some of his friend prescription meds in order to remind them to take their meds. Together the entire bar was quietly working and all because Mathilde and Gabe had gotten into a pissing match.

When the two clashed it was an intriguing display, for the fact that Gabe represented the protector of the ideals and Mathilde the ideals themselves. When they fought a sexual tension lingered between them and it made everyone uncomfortable, except for Mathilde’s brother who was usually drunk or stoned out of his mind. The substance of their quarrel was the location of the rally they were planning. It was a common enough bickering point and everyone knew that Mat and Gabe loved each other too much to ever do lasting damage.

Mathilde and Gabriel were not dating. They were co-leaders, co-leaders that had an abundance of sexual and most likely romantic attraction that showed when they argued or were working super well together. Gabe constantly eyed Mathilde. His blue eyes drifting from his plans to Mathilde and her brother.

Gabe had always found Mathilde beautiful, but he never acted on it. His attraction for her had grown as she had gained her footing as the co leader in the group. Jared had first brought his sister when she was a sophomore after she had spent a year basically leading a feminist group. Jared brought her to the meetings to keep a better eye on her, even though he usually got too drunk to take care of her at this place.

Jared liked Gabe very much, he found the man noble and highly moral. Gabe seemed to have a zeal about him that Jared admired. Whereas Jared seemed to have no nobility or anything to be zealous about. Jared was the kind of person who appeared to have nothing going on. Jared was a smart and could have done even better things in his life. When he was a high school student he got into the party scene. He had played lacrosse and too dance aswell, but something happened. Parties and stupidity and pressures of society had driven him into a jaded state. He had been driven into such a pit of self loathing. His sister had tried to help him but it was hard for her. She was five years younger and could only do so much.

Mathilde had dragged him out of bars, out of friends houses, and literally any place where one could party and get high/drunk. It was a sad sign when your ten year older sister had to literally pull you home in a wagon on her beach cruiser. By the time she was 13 Mathilde had been driving for two years illegally getting her brother home. It was rough but Jared did care very much for her and did try his best to be there for his little sis. He had helped her practice her dancing, drove her to class when he could, and came to every single competition. When ever he found her stressed out of her brain doing homework, crying because she was overwhelmed, or was feeling down in general he would distract her, help cheer her up with music blasting/ watching bootlegged musicals/musical movies. When he got his car he would take her out for whatever food she wanted and they would sit and eat together while he joked around to make her feel much better. He took care of her like a big brother should care for a little sister.

Gabriel, then turned his eyes away and noticed the loving glance that Conrad was giving Chris. It was so annoying the fact that both his best friends were madly in love with each other and had been since highschool but never ever did anything about it. He cleared his throat causing Chris and Conrad to snap their heads to look at him.

“Yes?” Chris perked up at the opportunity to take on a new task.

“Have you finished the organization of those past articles to add to our archive?” Gabriel asked his organization happy friend.

“Yes, anything else?” Chris sighed. Gabe wrinkled his forehead.

“Can you and Conrad work on figuring out the next location for our protest?” Gabe ordered

“Yes, of course,” Conrad smirked and tugged on Chris’s cardigan. Chris smiled and opened his binder and Conrad rolled his eyes. Conrad had fallen in love with a nerd, a goddamn beautiful nerd. A nerd he wanted to date.

Gabe looked back at Mathilde who was chatting with her brother. He frowned a bit and looked at the memo on his laptop a text from his mother warning him about his activities and his funds from his parents.

Younger generations tend to see the world as it could be not as it is. Students want to change the world more than many of their parents who were content with their bourgeois existence. In the youth you find the vision of how the earth should be and not as it was. That is different in their predecessors who can no longer see that view their lives adjusting to the problems they live with. They assimilate to the problems and begin to forget about them even justify their existence. Then there is the matter of religion and how many people find it truly latter in life. Religion has been the reason for wars and laws for years and when someone has found it they use it justify even the worst kind of laws. That was essentially why Gabe found his funds under threat by his parents.

Gabriel Apollinaire Saint Louis belonged to a prominent and wealthy family resting comfortably in the top one percent. Gabe had opportunities for everything growing up, he attended multiple high brow boarding schools. Gabe’s family lived in a large house in Connecticut. It was sandwiched between the houses of the Philander and the Wiatt family. The homes of Conrad and Chris. The boys stuck together in their high class, very posh lives. Their large back yards and game rooms gave the three relatively well behaved boys enough entertainment for the summers and holidays in which they were home from their boarding schools and exchange programs.

It seemed that no place would be more unlikely for a young revolutionary to be spawned. That was his background Mrs. Saint Louis was a well mannered woman who had a very strict idea of how things ought to be done. It must be mentioned that the surname Saint Louis, was pronounced San Loui, at her discretion. She could not stand when someone pronounced it Saint Lewis, like the city. She dressed in highly fashionable and simple clothing with delicate elegant jewelry. Her favorites were pearl necklaces and sapphire earrings. The woman kept the appearance as neat as possible with perfect modest makeup. Her blonde hair that had to be dyed regularly to hide the gray that was showing itself more and more with age was always swept off her face and done perfectly never frizzy and with no hair out of place. She looked perfect constantly as if nothing in her life had ever been wrong.

Mrs. Saint Louis, or Reinette, was a strictly catholic and pious woman. She had been born in France to a well of family, that raised her in a slew of religious schools around the world. Reinette dragged her small family of three to church every Sunday, unless they were sick or had a conflict that could not be ignored. She was known as a leader of book clubs, charity galas, and countless bible studies. Reinette loved gardening and had a beautiful garden that was maintained by her and the staff of three grounds keeper. Although, she seemed strict she would never lay a hand on her son if not in a loving embrace. Her little angel, her Gabriel, whom she had named. From the second he was born she had made sure her only son had every advantage in the world. She constantly insisted her son was a genius and fancied him a successful high power lawyer and maybe a senator. Her love for her son knew no bounds but it did not mean she was not willing to be strict with her little angel. When he did things in which she disapproved she did not hesitate in punishing him with taking away things.

When it came to politics she had very firm opinions. Most of the time Fox news played through the home although Gabe most often changed it to CNN which was as liberal as Mrs. Saint Louis was willing to allow in her tightly run ship of a home. However, when Gabe had tried to watch MSNBC on the living room tv she had a fit and blocked the channel as if it were something nasty like porn. Her dismay at her son’s new radical opinions was very evident. Yet she could never do anything as cruel as cut her son off.

Mr. Saint Louis, or Charles, was a charming man with wit that was used sparingly. He dressed constantly as if he was in the public view his blonde hair always neatly combed and his clothing well ironed and crisp, his shoes were always shined and he had a liking of expensive fine watches. His hobbies included attending sporting events, besides basketball, through box seats that were always high class and comfortable. He also liked painting and art in general. That was how he had met Reinette.

He had traveled to France to study art for awhile, where he met Reinette Lebelle. She had met him at a cafe they both frequented. They had married fairly quickly after that meeting. Then they had Gabriel and he became their world. In Gabriel, Mr. Saint Louis saw his replacement as the leader of his company. In Gabriel he saw a brilliant and charming young man capable of wonderful things. His son’s upbringing meant the world to him and he parented Gabe the best way he knew how. He parented him with the goal of raising his replacement and a mini version of himself and his wife.