#Columbian black-tailed deer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Columbian black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus)

White Boy spotted in Washington

Seeing white deer isn’t all that rare around here but this lil baby was just SO CUTE with his giant brown nose I had to draw em

#nice art op#columbian black-tailed deer#black-tailed deer#odocoileus hemionus columbianus#image#deer

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Columbian black-tailed deer Odocoileus columbianus columbianus

Observed by eckhartdpe, CC BY

#Odocoileus columbianus columbianus#Columbian black-tailed deer#Cervidae#deer#North America#United States#California

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buck contemplating a muddy crossing - in the end he went for it!

#original photography#original photographers#artists on tumblr#pacific northwest#hiking#nature#washington#nikon#pnw#orofeaiel#wildlife#animals#deer#buck#forest friends#swamp#creatures#columbian black-tailed deer#i think

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

hmmm I put in all the field marks but my Merlin app doesn't have an entry for this species

0 notes

Text

Columbian black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus)

Love him... love mr. cool...

134K notes

·

View notes

Text

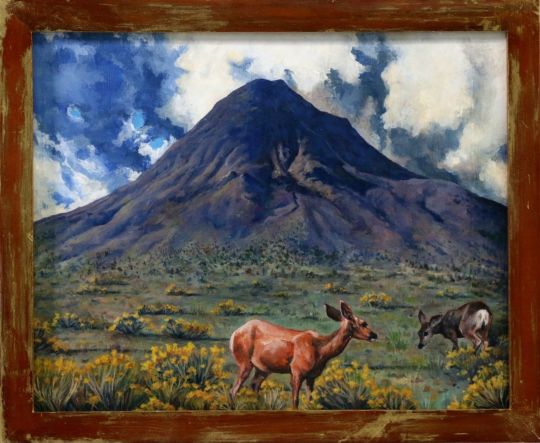

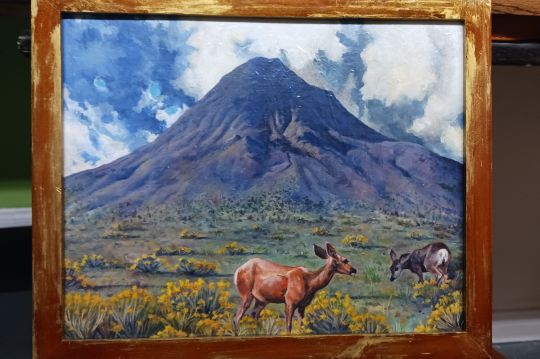

Bell Mountain, Pre-Columbian It's a local landmark, and is not actually a 'mountain' as much as a large, very steep hill. There's these lonely steep hills just kinda around parts of the Mojave. They're decomposing just extra slowly because of the material. It's neat! It doesn't look exactly like this, that is, there's a water tank and businesses and suburbs nearby the actual mountain. Sometimes I look at the desert and try to imagine it before there were invasive grasses and mustards. A wet autumn a thousand years ago.

#art#painting#acrylic#acrylic painting#open acrylics#deer#bell mountain#mojave desert#inland empire#mule deer#columbian black tail deer#rubber rabbit bush#rubber rabbit brush#rabbit bush#pre columbian#natural history#natsci#sciart#natural history illustration

1 note

·

View note

Text

Columbian Black-tailed Deer Odocoileus hemionus columbianus

8/16/2022 Pinnacles National Park, California

#deer#black tailed deer#mule deer#wildlife#nature#animals#wildlife photography#photographers on tumblr#my photos#california#california wildlife#pinnacles#pinnacles national park

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Columbian Black-tailed Deer (Piebald) | Milli Vedder

#photo#cervidae#capreolinae#odocoileus#odocoileus hemionus#odocoileus hemionus columbianus#mule deer#colombian black tailed deer#aberrant#piebaldism#milli vedder

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Columbian black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus)

a hard rain’s a‐gonna fall.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Columbian black-tailed deer Odocoileus columbianus columbianus

Observed by phylogenomics, CC BY

#Odocoileus columbianus columbianus#Columbian black-tailed deer#Cervidae#deer#North America#United States#California#juvenile

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Columbian Black-Tailed Deer | MRNP

#artists on tumblr#original photographers#original photography#hiking#pacific northwest#nature#washington#pnw#nikon#orofeaiel#animals#wildlife#deer#columbian black tailed#four legged friends#locals#fog#forest#landscape#moody

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s Tell a Friend Friday!

Please enjoy this photo I took of the hoofprint of a Columbian black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus).

Then tell someone you know about my work–you can reblog this post, or send it to someone you think may be interested in my natural history writing, classes, and tours, as well as my upcoming book, The Everyday Naturalist: How to Identify Animals, Plants, and Fungi Wherever You Go. Here’s where I can be found online:

Website - http://www.rebeccalexa.com

Rebecca Lexa, Naturalist Facebook Page – https://www.facebook.com/rebeccalexanaturalist

Tumblr Profile – http://rebeccathenaturalist.tumblr.com

BlueSky Profile - https://bsky.app/profile/rebeccanaturalist.bsky.social

Twitter Profile – http://www.twitter.com/rebecca_lexa

Instagram Profile – https://www.instagram.com/rebeccathenaturalist/

LinkedIn Profile – http://www.linkedin.com/in/rebeccalexanaturalist

iNaturalist Profile – https://www.inaturalist.org/people/rebeccalexa

Finally, if you like what I’m doing here, you can give me a tip at http://ko-fi.com/rebeccathenaturalist

#track#animal tracks#tracking#nature#wildlife#deer#black-tailed deer#mule deer#mammals#scicomm#science communication#ecology#environment#conservation#science#animals#science education

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Columbian black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus)

just watched this guy fumble two does in a row

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Deer have been on human minds and in human lives for eons. Between 120,000 and 108,000 years ago, Homo erectus relied on deer for food on the island of Java. A Neanderthal living in what is now Germany carved chevron shapes into a deer bone 51,000 years ago. Between 33,000 and 30,000 years ago, Paleolithic people painted on the walls of Chauvet Cave in what is now France. Among the animals they left for us to ponder are red deer, reindeer, and Megaloceros—the largest deer to have ever lived.

Deer have appeared in the art and mythology of the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Celts, Hindus, and Chinese, for whom deer represent longevity and prosperity. They are prominently represented in medieval European heraldry, mythology, and culture. The deer is a sacred symbol of the Maya world and its image appears throughout their culture. Maya mythology holds that it was a stag, using his hoof, who formed the sexual organs of the moon. The Maya sacrificed deer to their gods and used deerskin to record the pre-Columbian Maya codices. To this day, many Maya people have the surname Ceh, which means “deer” in the Mayan language.

Across cultures and time, people have revered deer as symbols of spiritual authority. A deer’s antlers, resembling a crown, extend beyond its head and body, connecting it to the heavens. Those same antlers drop off and regrow each year, making them symbols of regeneration. In Christian iconography, the stag serves as a symbol for Christ, conveying piety, devotion, and God’s care for his children. Deer star in countless folk tales and fables. In 1942, Walt Disney Studios released the animated film Bambi, which has helped shape North American perceptions of deer ever since. Through it all, human hunters have prized deer for their meat.

Deer are special. We are not talking about a plague of locusts, rats, or venomous snakes—we’re talking about deer. And whenever the words deer and problem come together, many people have big feelings.

Both Indigenous knowledge and Western science have long recognized that deer can have big impacts wherever their predators are few, causing a trophic cascade—the ecological term for changes throughout a food web. Aldo Leopold, the first professor of game management in the United States, famously observed a century ago how overabundant deer on Arizona’s Kaibab Plateau degraded the habitat to the extent that their population collapsed. “I now suspect,” he wrote in his seminal A Sand County Almanac, “that just as a deer herd lives in mortal fear of its wolves, so does a mountain live in mortal fear of its deer. And perhaps with better cause, for while a buck pulled down by wolves can be replaced in two or three years, a range pulled down by too many deer may fail of replacement in as many decades.”

Tara Martin has been studying the effects of overabundant deer for more than 15 years. Because some islands in the Salish Sea have deer and some don’t, they provide a natural experimental setup to measure deer’s effect on the environment. Martin has found that palatable plant species cover, richness, and diversity are 92 percent lower where deer are common and 52 percent lower where deer are scarce (less than 0.08 per hectare) compared with areas with no deer at all. On some islands, native black-tailed deer and exotic fallow deer occur at densities of over 20 per square kilometer. The resulting loss of understory means the loss of habitat for numerous bird species, which rely on the first 1.5 meters above the forest floor for cover, nesting sites, and food such as flowers and seeds.

“There are over 300 species in this ecosystem that are being negatively impacted by overbrowsing,” Martin says. “Many of those are plants, but it also includes bumblebees and songbirds, and our amazing alligator lizard and sharptailed snake species that are at risk of [local] extinction.”

— Giving Bambi the Boot

#brian payton#giving bambi the boot#history#prehistory#animals#zoology#early humans#christianity#environmentalism#ecology#wildlife conservation#extinction#paleolithic period#germany#france#china#mesoamerica#maya#usa#native americans#chauvet cave#deer#red deer#reindeer#megaloceros#homo erectus#neanderthals

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Columbian black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Black-tailed deer (Columbian) - Odocoileus hemionus columbianus

Santa Barbara County, Mar 22, 2024

0 notes