#Cloisonné

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A small cloisonné-enamel vase

Meiji era (late 19th century)

Bonhams

Worked in silver and gold wire and polychrome enamels with trailing wisteria around the shoulder, the neck with dense foliate scroll and the foot with a stiff-leaf band, all on a midnight blue ground, gilt-copper mounts

5 1/4 inches (13.1cm) high

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Potted Flowers (Chinese, 19th century). Maker unknown.

Cloisonné enamels; hardstones.

Image and text information courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art.

503 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold bracelets dated 9th–10th centur, Constantinople, Turkey.

Each bracelet consists of twenty partitions that are framed by granular strips and are decorated with cloisonné enamel.

The partitions alternately depict birds pecking at leaves, palms and rosettes and are rendered in different colour variations.

Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki

#art#history#design#style#archeology#sculpture#gold#bracelet#jewelry#jewellery#turkey#constantinople#9th century#10th century#cloisonné#enamel#birds#leaves#palms#rosettes#byzantine

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patek set.

Released in 1962 and designed by Gilbert Albert,

The unique bracelet watch (Ref. 3290) is accompanied by a matching ring and necklace.

Crafted from yellow gold, each piece is decorated with blue turquoise and green cloisonné enamel and set with round cultured pearls.

Courtesy: Sotheby's

#art#design#luxury#overdose#gold#jewellery#jewelry#luxury lifestyle#luxurious#diamond#patek#gilbert albert#necklace#ring#turquoise#cloisonné#pearls#sotheby's#billionaire#billionairelife

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyoto Namikawa aka Namikawa Yasuyuki (Japanese, 1845–1927)

cloisonné enamel vase - Meiji period (late 19th century)

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A rare pair of Chinese Imperial cloisonné and champlevé ennamel lingzhi jardinières Qing Dyansty, 18th Century

Ann and Gordon Getty Collection

#lingzhi#qing dynasty#18th century#china#chinese art#cloisonné#🍄#interior design#gold#coral#garouste & bonetti

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cloisonné: #bdd8ad to #638850 to #183915

#Cloisonné#gradient text#gradien#gradient-text#green#light green#dark green#green_gradient#bdd8ad#638850#183915

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

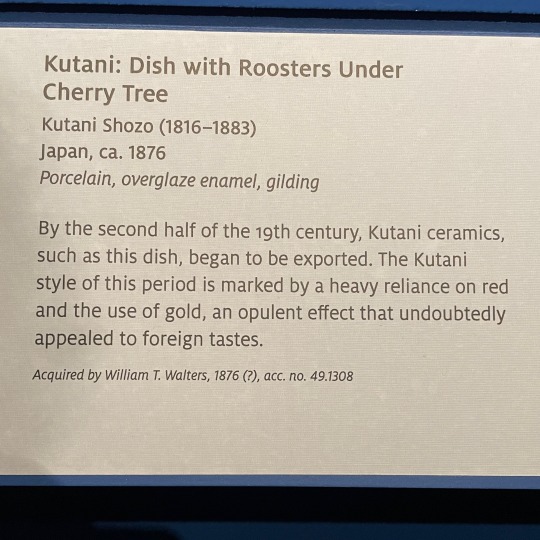

It’s #InternationalRespectForChickensDay 🐓 so here some roosters from the The Walters Art Museum’s Arts Across Asia exhibition!

Namikawa Sosuke (1847-1910) Vase with Rooster, Hen, and Chicks among Banana Plants Japan (Tokyo), early 20th century copper, gold-copper alloy (shakudö), silver, gold, enamel Walters Art Museum

“Beginning in the 1880s, Japanese cloisonné artists developed wireless cloisonné (musen shippo), a technique for which Namikawa Sosuke was renowned. This vase shows no traces of the metal wires that initially outlined the animals and plants. The effect was achieved by taking off the metal wires before each of the three firings, resulting in a cloisonné design that the artist intended to look like a painting.”

Kutani Shozo (1816-1883) Kutani: Dish with Roosters Under Cherry Tree Japan, c. 1876 porcelain, overglaze enamel, gilding Walters Art Museum

“By the second half of the 19th century, Kutani ceramics, such as this dish, began to be exported. The Kutani style of this period is marked by a heavy reliance on red and the use of gold, an opulent effect that undoubtedly appealed to foreign tastes.”

#Walters Art Museum#exhbition#museum visit#Arts Across Asia#Japanese art#Asian art#chicken#rooster#hen#chick#bird#birds#birds in art#ceramics#porcelain#cloisonné#19th century art#20th century art#animals in art#animal holiday#International Respect for Chickens Day

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Flow of Time_E_13 Material : cloisonne enamel(silver), acrylic, cotton cloth on wood panel (七宝焼(純銀)、アクリル絵具、綿布、木製パネル) Size: H20cm×W20cm Year: 2023

Tomoko Hokyo 宝居智子

#tomokohokyo#宝居智子#contemporaryart#art#artwork#artist#galleryart#contemporaryartist#cloissoneenamel#cloisonné#七宝焼#七宝#アートのある暮らし#アート作品

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's discuss jewelry made with cloisonné art.

Later in history, during the Renaissance, cloisonné saw a resurgence in popularity as European artisans tried to replicate the beauty of this Eastern technique.

Nearer to the present, the organic shapes and vivid colors of cloisonné were embraced by the Art Nouveau movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, revitalizing the tradition.

I know from personal experience that when one stumbles upon an old cloisonné piece in a hidden corner of a vintage shop, they are instantly transported back in time to the hands that painstakingly created it years ago.

These are powders of colored glass that have been finely powdered. They fuse to the metal basis at high temperatures, creating a surface that is robust and glossy.

Often composed of gold or silver, thin wires are expertly bent and attached to the metal base to create complex patterns that characterize the design.

The enamel mosaic that now adorns the metal cloisons produces an enthralling interplay of color and light

#jewelrymaking#jewelrydesigner#3dmodelofjewelry#earrings#jewelrycaddesigner#cloisonné art jewelry#cloisonné art#cloisonné

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

At last I found myself a creative moment in the studio yesterday to sort through lots of lost treasures and broken artefacts. I was also able to design these salvaged jewelry and upcycled earrings in pretty teal and orange sunset colours. I love these puffy Cloisonné enamel disc beads which feature the ancient Chinese symbol of Longevity. They pair well with the two glass flower molded carriage clock decorations that I found in a box of large clock parts. I gave them a tint of turquoise and gold alcohol inks to bring out the textures. At the base are some pretty mother of pearl carved flowers with pink coral beads and Czech glass leaf. Available in my Etsy shop - link in bio. . . . #cloisonné #cloisonnéenamel #carriageclocks #salvagedjewelry #sustainablejewelry #artefactearrings #ancientartefacts #chinesecloisonne #chinesesymbols #longevity #longevitysymbol #shou #shousymbol #ancientsymbols #talismanearrings https://www.instagram.com/p/CpnCqXIoUrI/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#cloisonné#cloisonnéenamel#carriageclocks#salvagedjewelry#sustainablejewelry#artefactearrings#ancientartefacts#chinesecloisonne#chinesesymbols#longevity#longevitysymbol#shou#shousymbol#ancientsymbols#talismanearrings

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vacheron Constantin Métiers d’Art Tribute to traditional symbols Eternal flow & Moonlight slivers

#cloisonné#enamelling#engraving#Métiers d’Art#news#Press release#Tribute to traditional symbols#Vacheron Constantin

0 notes

Text

Vase (circa 1876) by Elkington & Company (British, 1830s–1892).

Brass and cloisonné.

Image and text information courtesy Carnegie Museum of Art.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Polychrome jewellery like these earrings are part of a really, really old artistic tradition! The first examples come from early Bronze Age, like this pectoral (brooch) worn by a princess in Middle Kingdom Egypt:

Pectoral and necklace of Sithathoryunet with the name of pharaoh Senwosret II (c. 1887–1878 BCE), from his pyramid in Faiyum, Egypt.

So, the process of crafting these pieces (called cloisonné) is exactly as painstaking as you'd expect. First, the jewellers would cut gemstones (in this case garnet, turquoise, carnelian, feldspar and lapis lazuli) into precise shapes according to the design. Then, they would weld or hot-solder thin gold wires onto the gold base (usually cast from a lost-wax mould) to create the "lines" between the stones. Finally, the stones would be carefully glued into the slots, creating complex, multicoloured designs like you'd see here.

The ancient world was a deeply interconnected place: the deep blue lapis lazuli on the above piece was likely brought to Egypt all the way from modern-day Afghanistan. It naturally followed that the cloisonné technique took off in more than one place. While the thin-wire style came to define Bronze Age Mediterranean jewellery, the thick-walled style of medieval Byzantine cloisonné originated in another place: the Inner Eurasian steppe.

Kushan/Yuezhi pendant and neckwear (1st century CE) from the Tillya Tepe (Golden Hill) burial site, northern Afghanistan.

We often think that steppe peoples lived in small, freewheeling tribes, idly wandering endless open plains. This wasn't actually the case! They lived (and still live) a highly technical lifestyle, moving like clockwork between grazing grounds, trading towns and winter quarters sheltered by mountains and forests.

And most importantly: they were enthusiastic metalworkers. Steppe peoples prized their mines and smithies, whether as places they'd drop by on the way to the next pasture or as year-round homes for groups of professional metalworkers employed by nomadic nobles.

The Altai Mountains in Central Asia, the ancestral holy ground of many steppe peoples, were also one of the world's largest and richest mining and metallurgical complexes, going all the way back to the late Bronze Age. Starting in the early 1st millennium BCE, we started to see a flourishing of this style of ornaments, cast from gold or silver and inlaid with complex, often multicoloured gemstone designs:

Left: Sarmatian belt buckle (2nd-1st century BCE) from Sadovy Kurgan, Novocherkassk, Russia. Right: Xiongnu horse ornament (c. 1st century CE) from the Gol Mod burial site, Mongolia.

Steppe peoples were hardly the only ones who knew how to inlay gemstones into gold. Plenty of other cultures did it, too. What set Inner Eurasian cloisonné apart was the sheer complexity of its gemstone arrangements, rarely seen on the continent since the Bronze Age collapse. Many of these pieces were crafted in the shape of animals like horses, stags or leopards; others took more abstract, flowing shapes that evoked animal parts like horns or wings, symbolically calling upon their strengths on the wearer's behalf.

Since the most ancient times, the Greeks and Romans had heard of the Scythians, a nomadic Iranian people from the plains north of the Black Sea (think modern-day Ukraine), famed for their wealth and skills on horseback. In the late 1st century CE, some of these steppe Iranians (variously known to the Romans as the Sarmatians, Roxolani, Aorsi, Iazyges or Alans) started to make their way further west, to the Roman Empire's border on the Danube River. Their hierarchies of kings and nobles met the local Germanic peoples' egalitarian tribes; their polychrome craft met the flowing patterns on the natives' gold and silver.

Though the steppe Iranians fought many border wars against the Romans, there were many years of peace and quiet, too. The Romans paid good money for the nomads' craft through the Black Sea trade, and their skill on horseback made them highly sought after as elite soldiers. Some of them rose to very high ranks in the empire.

Then everything changed when the Hunnic Empire attacked.

Left: Scythian earring (c. 1st-2nd century CE) from Ust-Alma necropolis, Crimea. Objects from this trove were originally displayed at the Simferopol Museum; after the Crimean Peninsula was annexed by Russia in 2014, the Ukrainian government managed to successfully sue for their return from a Dutch museum they were on loan to. Right: White Hunnic dragon-shaped collar (5th century) from Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan

The Huns were a powerful steppe empire, heirs to an old, long-fallen empire far to the east. They were made up of many tribes, rearranged into ranked military units and commanded by nobles who swore their oaths personally to one of their two kings: one in the east, one in the west.

In a few short decades of the 4th century CE, the Huns conquered a vast swathe of land, from north of the Caucasus to the very borders of the Roman Empire on the Danube. The proudly independent Germanic peoples of Central Europe, whom the Romans couldn't quite conquer, now faced two choices.

They could submit to the Huns, pay them expensive tributes and be absorbed into their army, like countless nations before them. Or they could cross the river, into Roman land, and ask for sanctuary from the other empire.

Whichever way they went, the Germanic peoples — Goths, Vandals, Suebians, Langobards, Thuringians — were by now a transformed people. Centuries of trade and elite intermarriage with the Black Sea nomads had steeped them in the culture of the steppe: the strict ranks of kingship and nobility, the ways of the horse and the bow, the cult of mystical swords.

Now Hunnic rule would firmly imprint all those things onto their cultural fabric, along with one more thing: the art of the steppe.

Left: Hunnic noblewoman's diadem (5th century CE) from Kerch, Crimea. Right: Horse harness buckles (5th century CE) from the tomb of Ardaric in Apahida, Romania. Ardaric is traditionally believed to be a king of the Gepid people and a vassal of the Huns, but recent historians have suggested that he might've been a Hunnic prince himself.

In older histories of the Migration Period, you might see this style of cloisonné called by various European terms, like maybe "Visigothic" or "Aquitainian". These names belie the style's Asian roots. By the end of the 4th century, a uniform style of jewellery stretched from the Hungarian Plains to the Caucasus, practiced by the artisans living under Hunnic rule.

For a few decades, the Romans and the Huns sized each other up across the frontier. But in time, the Huns pacified their borders. The flight of Germanic peoples into Roman lands slowed down, and the old cross-border trade routes lurched back into life.

Sometimes the Romans would ask the Huns to break the kneecaps of "barbarian" bands roaming the borderlands (whom the Huns gladly hunted down as "fugitives"), and paid them off with tributes of gold and precious stones, which were turned into colourful jewellery for Hunnic rulers to reward their vassals with.

Which brings us to the proverbial elephant in the room! These splendid works of art mostly belonged to the royals and aristocrats at the top of society. If you were an average peasant living under Roman rule — or a herder living under Hunnic rule — you might see these things displayed at houses of worship and religious rituals, you might even wear one to really big occasions like weddings, whether borrowed or as a family heirloom.

But it would've been a small upper-class who owned these things in droves (enough that their families buried them with their jewels when they died). In some cases, the nobility would even enact strict sumptuary laws to control what kinds of ornaments each social class was allowed to wear. Even though it would've been the commoner's hands that dug out the stones from deep, dark tunnels. Their hands that farmed and herded to pay the elites taxes; maybe their arms that seized gold or exacted it as tribute in the wars they were levied to fight.

And lest you think we left all this behind in the "Dark Ages": the global jewel industry today is still deeply tied with armed conflict and labour abuse. That slab of lapis you saw on CrystalTok? Probably smuggled out of war-torn Afghanistan. Gold rings and bracelets? Could well have come from mines run by warlords in the Sahel.

Not all precious stones and metals are mined at gunpoint, obviously — there are plenty of people in the industry who are proud of what they do and are compensated well for it, now just as then. The passion and skill that went into crafting these incredible works of art were 100% real.

But I think it's important to remember the equally real systems of violence that ensured that so much of them flow so easily and cheaply to the end user. Jewellery, like all other displays of surplus wealth, has a long trail of bloodshed and oppression surrounding it.

Left: Ostrogothic noblewoman's eagle-shaped brooch in the Hunnic style (5th century CE), Domagnano, Italy. Right: Illustration of Danubian (Hunnic) grave goods from the tomb of Frankish king Childeric I (5th century CE), stolen from the National Library of France in 1831. Both the Ostrogothic and Frankish peoples were vassals of the Hunnic Empire.

In 453, Attila, the supreme ruler of the Huns, died suddenly at a feast. Throughout his two decades of rule, Attila had brought his empire into open war with the Romans; inflicted mortal wounds on the Western Empire; brought the Eastern Empire to its knees.

But his reign also laid on unstable foundations. Attila had installed himself as sole dictator by murdering his brother who ruled over the eastern plains and moving the core of his empire west, to the Hungarian Plains. With the king gone, his heirs and vassals quickly lapsed into civil wars as they sought to claim his empire for themselves — in full or in part.

Flash-forward to a century later, around the time the time Byzantine earrings in the OP were made. Europe, by this time, was a very different place. The Western Roman Empire was gone. A smattering of kingdoms stood in its place, ruled by the military elites of migrating Germanic peoples who'd come to an accommodation with the local Roman senatorial elites and church clergy.

For a few short decades, at least, the new kingdoms of Europe traded with the Eastern Empire in peace. That wouldn't last forever (thanks, Justinian); but it was enough time for the steppe-derived style of cloisonné jewellery to permeate Byzantine fashion, adding onto the earlier Germanic and Alan influences.

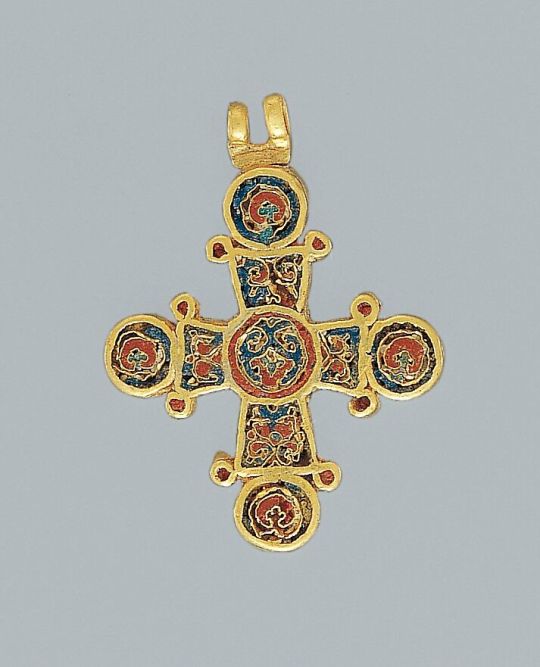

Left: Enamelled cross. Right: Medallion of St John the Baptist. Both from Constantinople, c. 1100 CE.

So while the northern Germanic kingdoms (like the Carolingian Franks and the Anglo-Saxons) took the craft to the far corners of the continent, the Byzantines worked on combining it with familiar Greco-Roman techniques. Byzantine cloisonné would be marked by fine carved reliefs along the gold's surface, and also textures made by chasing and repoussé.

Throughout the next few centuries, Byzantine artists revived a couple of ancient Egyptian practices. The first was the use of thin gold wires, which they used to create complex (often religious) images.

The second was a Roman specialty: glass! Precious stones like garnet and turquoise are eye-catching, sure. But they cost a lot to mine, a lot more to cut and polish, and there are only so many ways you can work with them. So Byzantine jewellers started pouring coloured glass powder into spaces in the design, and then heating it until it fuses into enamel.

This enamelling technique, combined with thin wires, enabled much more complex designs than were traditionally possible with precious stones. But it wasn't 100% foolproof! The fusing temperature of silicate glass can be quite close to the melting temperature of gold alloys (and doubly so for silver and copper-based alloys), meaning it took a lot of care to fire the powder into translucent glass without damaging the rest of the piece.

So yeah: we might be used to thinking of "Europe" and "Asia" as two separate worlds. But the past was a lot more interconnected than it might appear; even some of the art we associate with "Medieval Europe" have deep roots in the Central Asian steppes. And I think that if we look closely at the world around us, we'd all be surprised by how many markers of wealth and style had roots in equally unlikely places.

References:

Zhixin Sun, James C. Wyatt and Emma C. Bunker, Nomadic Art of the Eastern Eurasian Steppes (2002)

Hyun Jin Kim, The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe (2013)

Nicola Di Cosmo, Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity (2018)

A pair of gold earrings with garnet, pearl, and chalcedony elements, Byzantine, 6th century AD

from Hindman Auctions

#cloisonné#jewellery#polychrome#history#late antiquity#early medieval#migration period#central asia#eastern europe#attila the hun#scythians#sarmatians#byzantine empire#goths#franks#merovingian#inlay#gems#garnet#turquoise#gold#enamel#historical aesthetic#fashion history#mesoamerican turquoise mosaics kinda had the same energy#but they're way out of my ballpark#steppe nomads: closer than they might appear in your history textbooks

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold wristwatch with cloisonné enamel dial depicting a dragon by Nelly Richard, perpetual chronometer, ref. 6099,

Rolex, circa 1952.

#art#design#overdose#gold#jewellery#jewelry#luxury lifestyle#luxurious#dragon#rolex#nelly richard#enamel#1952#vintage watch#collectors#chronometer#wristwatch#cloisonné

21 notes

·

View notes