#Cleopatra II

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Kleopatra II, as the first basilissa spousal co-ruler, jointly held power with Ptolemy VI, and then Ptolemy VIII, during which time she saw to the political, religious, and international affairs of Egypt. She was also the first basilissa-regnant, ruling the administrative center of Egypt on her own for a period of at least three to four years. Her ability to rule Alexandria on her own and her feminization of the dating protocol would allow several successive queens to follow in her footsteps, most notably, Kleopatra VII."

— Tara L. Sewell-Lasater, Becoming Kleopatra: Ptolemaic Royal Marriage, Incest, and the Path to Female Rule (University of Houston) / Anne Bielman Sánchez and Giuseppina Lenzo, "Ptolemaic Royal Women", The Routledge Companion to Women and Monarchy in the Ancient Mediterranean World

"Kleopatra I left behind her three minor children: Ptolemy VI, his sister Kleopatra II, and his brother Ptolemy VIII. To strengthen this fragile royal power base, two operations were carried out: first, a marriage between Ptolemy VI and his younger sister was conducted in the spring of 175, then joint rule was established between the three siblings in 170. Even if Kleopatra II appears in the protocols of this ruling trio only in final position, behind the two kings, she nevertheless played a political role by mediating between her brothers in the Sixth Syrian War (Liv. 44.19.6; 45.11.3 and 6).

After the reconciliation of the siblings in 168, the ruling trio was active again, but tensions persisted and led to a split in 163: Ptolemy VIII became king of Kyrenaika while Ptolemy VI and his sister-wife began a joint rule over Egypt and Cyprus, a rule that lasted until the death of Ptolemy VI in 145. The queen then appears in all Greek and demotic protocols, in second position behind Ptolemy VI, and is often referred to as the “sister” or “sister and wife” (of the king). In addition, she officially participates in the management of the kingdom: the two sovereigns are invoked in the oaths of Egyptians and they receive petitions and reports in both their names and co-sign some royal orders and letters to officials. The honors for the queen and her husband in several gymnasiums in Kypros and Egypt confirm that she was considered the king’s partner by Greco-Macedonian inhabitants of Egypt.

The death of Ptolemy VI in the summer of 145 put an end to this duo and promoted Ptolemy VIII’s ambitions. Indeed, the option of a joint rule between Kleopatra II and her minor son is abandoned in favor of a joint rule between Kleopatra II and Ptolemy VIII. Through these events, the queen appears to be the legitimizing element of Ptolemaic power. In the protocols of the new joint rule, Kleopatra II regains her rank behind the king as well as her title of “sister” or “sister and wife” (of the king), while her role as an effective co-ruler of the kingdom seems to have been maintained. While the marriage in 141/140 of Ptolemy VIII and his niece—the daughter of Kleopatra II and Ptolemy VI—led to a ruling trio, Kleopatra II kept her place in the new configuration: she appears in the second rank, behind the king, and is generally called “the sister” to distinguish herself from Kleopatra III, who is called “the wife.”.

The agreement between the trio shattered in 132, when the Alexandrians drove out Ptolemy VIII and Kleopatra III, and supported Kleopatra II. Kleopatra II’s two sons (one born of Ptolemy VI, the other of Ptolemy VIII) were murdered by order of Ptolemy VIII to prevent the queen from forming a joint rule with one of them. Kleopatra II was then forced to assume sole royal power: in 131 and 130, documents from cities in the south of the country (notably Thebes) mention a new sequence of regnal years, and a protocol of a Greek papyrus from Hermonthis is dated “under the reign of Kleopatra, goddess Philometor Soteira” (P. Baden Gr. II.2, October 29, 130).

After the failure of an alliance attempt with her son-in-law, the Seleukid king Demetrios II, Kleopatra II facing the military reconquest of the country by Ptolemy VIII, left Egypt in 127 and took refuge at the Seleukid court. However, her royal career was not over: in 124, thanks to negotiations between Ptolemies and Seleukids, she returned to a ruling trio with Ptolemy VIII and Kleopatra III, and regained the same rank and title as before the civil war. Finally, we cannot rule out the possibility that, after the death of Ptolemy VIII in 116, Kleopatra II briefly participated in a ruling trio with Kleopatra III and her son Ptolemy IX. She probably died in 115.

As a partner in six joint rules, Kleopatra II sets the record for the longest reign of a queen on the Ptolemaic throne (55 years)."

#HOW is she not more well-known?#Kleopatra II#Cleopatra II#Egyptian history#ancient egypt#ptolemaic egypt#women in history#historicwomendaily#my post#hellenistic period#ancient history#Ptolemy VI#Ptolemy VIII

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Three major elements form the basis of female power in Ptolemaic Egypt: (1) the valorization of the royal matrimonial couple (from at least the time of Berenike II); (2) the system of joint rule with two or three partners (from the time of Kleopatra I); and (3) the dynastic cult (from the time of Arsinoë II). Each reign introduced innovations that were usually accepted and developed by the next ruler, including the institutional revolution of joint rule. However, some innovations were tolerated only because circumstances necessitated it, despite the fact that they were neither valued nor developed: this can be observed in the case of the reign of a single queen. In fact, the strength of the Ptolemaic queens rested on the presence of a mixed–gender couple. It could be a husband–wife tandem (inbred or not), as in the case of Berenike II or Kleopatra II. It could also be a mother-son tandem, as in the case of Kleopatra I, who established the first joint rule with the young Ptolemy VI; or Kleopatra III, who innovated by leading a joint rule with each of her adult sons Ptolemy IX and Ptolemy X; or, finally, Kleopatra VII, who, through her joint rule with her son Caesarion, represents the climax of Ptolemaic female power."

— Anne Bielman Sánchez and Giuseppina Lenzo, "Ptolemaic Royal Women," The Routledge Comapnion to Women and Monarchy in the Ancient Mediterranean World (edited by Elizabeth D. Carney and Sabine Müller)

#history#ptolemaic egypt#ancient egypt#Hellenistic age#historicwomendaily#cleopatra vii#kleopatra vii#berenice ii#Arsinoe II#cleopatra ii#cleopatra iii#I'm genuinely amazed by the scale and research of this book#it's magnificent#mine#ancient history#queue

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This intaglio shows the head of Ptolemaic Queen Cleopatra II, in profile to the left.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm curious about people's levels of familiarity; I intend no judgment or elitism and it's absolutely fine not to be a completionist, btw. I didn't think I would've intended to have read them all at age 25; it just sort of happened that after I passed the halfway point in the middle of 2023, I came out of a reading slump and was motivated to finish. Fwiw I consider myself a hobbyist (I am not involved in academia or professional theater) but I realize that that label is usually attributed to people with less experience.

I also have always loved seeing other bloggers' Shakespeare polls where they put certain plays or characters up against each other, but I'm often left wondering if it's really a 'fair' fight all the time if you're putting up something like Hamlet or Twelfth Night against one of the more obscure works, like the Winter's Tale. It's not a grave affront to vote in those polls if you don't know every play, but I am curious about it.

Please reblog for exposure if you vote; I would appreciate it a lot. Also feel free to elaborate on your own Shakespeare journey in tags, comments, reblogs, because I love to hear about other people's personal relationships to literature.

#yeah that's that!#shakespeare#william shakespeare#english literature#i guess i'll tag some random plays so this has better reach in searches#ill do some popular ones and also some obscure favs lol#hamlet#othello#macbeth#king lear#much ado about nothing#twelfth night#as you like it#the winter's tale#cymbeline#the tempest#henry iv part 1#henry v#richard ii#richard iii#all's well that ends well#antony and cleopatra

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

grabbed all of the ebook versions of the folger shakespeare library's annotated versions of shakespeare's plays (+sonnets and poems) and put them all in one place in case anyone is interested

#shakespeare#ws#henry vi#richard iii#comedy of errors#titus andronicus#two gentlemen of verona#love's labour's lost#romeo and juliet#richard ii#a midsummer night's dream#king john#merchant of venice#henry iv#much ado about nothing#henry v#julius caesar#as you like it#twelfth night#hamlet#troilus and cressida#all's well that ends well#measure for measure#othello#king lear#macbeth#antony and cleopatra#coriolanus#the winter's tale#the tempest

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Introducing Cleopatra II and Mark Antony II; a co-worker asked for some baby plants so I'm propagating several cultivars.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“First Queen II: Sabaku no Joō” Yoshitaka Amano 1990

296 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Full view plz)

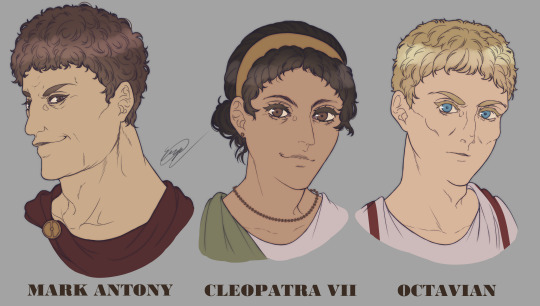

Some historical characters that will be making an appearance in the webcomic I'm developing!

#webcomic#ancient history#ramesses ii#hatshepsut#amasis#mark antony#cleopatra vii#octavian#augustus#alexander the great#hadrian#antinous#ancient egypt#ancient rome#ancient greece#roman egypt#hellenistic egypt#imperial rome#hellenistic period#republican rome#ptolemaic egypt#shmswart#thefollowersart

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cleopatra Eurydice

#studyblr#notes#history#historyblr#history notes#world history#world history notes#western civ#western civilization#philip II#cleopatra eurydice#macedonia#greece#ancient greece#olympias#europa#alexander the great#greek history#caranus#alexander of macedon#macedon#ancient macedon#cleopatra

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

i haven't drawn digitally in maybe five years, so here are some recent studies i did of tamara dobson from cleopatra jones and sylvester stallone from rocky ii. fun fact: i drew these with my finger bc i don't have a drawing tablet any more, haha!!

refs that i used are under the cut!

#tamara dobson#cleopatra jones#sylvester stallone#rocky ii#black artist#my art#artists on tumblr#artist of color#fanart#digital art#i tried to color the art of sly but failed miserably so that's why it's just the line art#also i hate drawing digitally so much i don't see how y'all do it!!#traditional art my one love!!!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

#ai#cleopatra#shakespeare#caesar#julius caesar#genghis khan#elizabeth#queen elizabeth ii#vincent van gogh#benjamin franklin#tmnt michelangelo#ada lovelace#nikola tesla#amelia earhart#tutankhamun#johan sebastian bach#abraham lincoln

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Cleopatra took her own life, she left behind her four surviving children.

Her firstborn, and only living child with Caesar, Caesarion, did not live for long after her death. She had sent him away from Egypt for his own safety, but he was falsely lured back with promises of being allowed to rule in her place. He was murdered by Octavian’s men, after he’d received advice that “Too many Caesars is not good". As Caesar’s biological son, he was too much of a threat to Octavian’s rule. It’s thought he was likely killed by strangulation, but no one knows that for certain, or what happened to his body. He was 17 years old when he died, and had nominally been sole ruler of Egypt after his mother’s death.

It was a different story for her children with Mark Antony. There were the twins Cleopatra Selene II and Alexander Helios, who were both 9 at the time of their mother’s death, and Ptolemy Philadelphus, who was just 5 or 6. The three of them were taken to Rome by Octavian, and forced to walk behind his chariot in his Triumph Parade, attached to it with chains so heavy they could barely walk. This aroused not the scorn he’d been expecting, but sympathy for the poor young children. Octavian gave them to his sister Octavia, who had been married to their father, to be raised along with her children.

Neither of the boys would see adulthood, both apparently dying sometime before 25 B.C. There were rumours that Octavian had both of them killed, not wanting any adult sons of Antony and Cleopatra to remain alive.

Cleopatra Selene however, had a somewhat kinder fate. She was married to Juba II, King of Numidia and later Mauretania. She inherited the same strength and pride in her heritage of the Ptolemaic women that came before her, and used the same titles as her mother on coins. She had at least one child, a son she named Ptolemy, and possibly a daughter named Drusilla. Her exact date of death is unknown, but she was placed in the Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania when she died. It is still visible today, and a fragmentary inscription there is dedicated to Juba and Cleopatra, as the King and Queen of Mauretania.

#cleopatra vii#caesarion#cleopatra selene#cleopatra selene ii#alexander helios#ptolemy philadelphus#long live the queue#ptolemaic dynasty#cleopatra

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

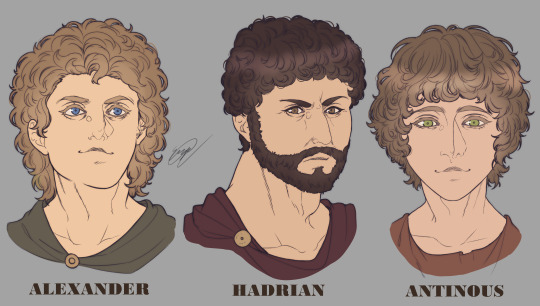

A friend of mine shared this post with me that she came across on Twitter, and there's something I'd like to break down about it :

As a North African Amazigh, I find it concerning when there are attempts to inaccurately portray our heritage. The Amazigh people have varied skin tones, influenced by regional climates. Generally, the further north you go, the lighter the skin color tends to be among the population. Juba, being a descendant of the Massylii tribe which was located in the northeast of Algeria, would likely have had a Mediterranean skin tone. It would be historically inaccurate to categorize him as black.

I'm tired of seeing him portrayed as black in literature (like in Stephanie Dray's trilogy 🤡) If you're going to write about a certain culture, it's essential to thoroughly research and understand that culture instead of perpetuating stereotypes or misrepresentations.

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

Would Alexander have really married Cleopatra Eurydice? He seems to have respected her enough despite her relation to Attalus- some sources say when removing her statue from the Philippeum he transferred it to another respected place in Heraion. Did they get along personally? How would their marriage have changed matters, if at all?

Did Alexander Mean to Marry Kleopatra Eurydike?

Okay, first, I believe we have a confusion/conflation of Eurydikes. The one from the Philippion is Philip’s mother, wife of Amyntas III. Her statue was never removed out by Alexander, so I’m unsure what the asker is referring to? The statues were lost over time, but we have the statue bases, and descriptions of the monument. See especially Elizabeth D. Carney, “The Philippeum, Women, and the Formation of Dynastic Image,” in W. Heckel, L. Tritle, and P. Wheatley (eds.) Alexander’s Empire: Formulation to Decay (Claremont, CA, 2007) 27-70. For Eurydike herself, see Olga Palagia, “Philip's Eurydice in the Philippeum at Olympia,” in E. Carney and D. Ogden (eds.), Philip II and Alexander the Great (Oxford 2010) 33-41.

“Eurydike” became a dynastic name, so it keeps popping up among Argeads (and later). Philip’s mother was Eurydike, as was his daughter, wife of Philip III Arrhidaios: (Hadea) Eurydike. Also Kleopatra, niece of Attalos, took the name Eurydike when she married Philip. But she was never in the Philippeon. Philip’s only wife represented there was Olympias, mother of his heir, Alexander. Amyntas III and Eurydike appeared as his parents.

We have no idea if Alexander shared more than a few words with Attalos’s neice. Given her uncle’s hostility towards him, he would likely have minimized contact. Also, timing was against it. Alexander left on the heels of the marriage, was gone 6 months to a year, then likely kept his distance after his return. While Macedonian women were not as sequestered as in Athens, men and (respectable) unrelated women still didn’t mingle freely. If he did interact with her, it would have been when visiting the women’s rooms to see his sisters, with plenty of women present. If marrying a dead father’s widow had precedent, an affair with the wife of one’s living father was another thing. Alexander knew his mythology, and would’ve had no desire to be Hippolytos.* After he took the throne, he had to leave relatively quickly to settle affairs in the south…and she was (likely) dead before he returned.

As for the marriage… this was suggested by my colleague, Tim Howe: “The Giver of the Bride, the Bridegroom, and the Bride,” in T. Howe, S. Müller, and R. Stoneman, Ancient Historiography on War and Empire (Oxbow, 2017) 92-124. Nothing in the ancient sources says Alexander planned such a marriage BUT marrying the wife (especially if young) of the former king wasn’t novel in Macedonia; Archelaos did the same. It was accepted practice generally.

The titbit that might suggest Alexander did plan to wed Kleopatra-Eurydike … Olympias murdered her.

Now, ignoring Justin’s account of a son Karanos, which is wrong (for reasons I don’t have time to go into), Kleopatra-Eurydike’s child was a girl (Europa). That means Kleopatra had no power in the women’s rooms after Philip’s assassination. So why the hell would Olympias kill the infant (and her, by extension)? Revenge alone?

Possibly. Revenge, especially for a slight to timē (personal honor), was a perfectly respectable reason to kill someone. “Turn the other cheek,” or “When they go low, we go high,” is a very Christianized view. But an even better revenge would have been to let her live to raise an extra daughter under the king her uncle had insulted and schemed to replace. Philip had 3 prior adult/almost adult daughters. A 4th, well over a decade from marriageability, was a day late and a dollar short. She could expect a miserable existence in the Pella palace where she was no threat to Olympias.

Unless Alexander planned to marry her in a diplomatic solution to suppress Attalos’s faction, and secure Parmenion’s support. (Attalos had married Parmenion’s daughter.) I strongly suspect Philip’s final marriage was not the midlife-crisis love match Plutarch/Diodoros present, but an attempt to deal with push back in his latter years. Alexander may have decided that marrying the girl was the best way to deal with it too.

And if Alexander did plan to marry her, she was a threat to Olympias’ influence. This isn’t necessarily jealousy. Olympias may have decided that wooing the snake wasn’t sound policy. Remember that Alexander was barely twenty and Olympias would have been between 36 and 38, with oodles more political experience. While sure, her move was self-serving, it also may have been sound policy to keep her son from the match. (Two things can be true at once.)

Alexander need not have publicly declared an intention to marry his father’s widow; he had bigger fish to fry in the immediate aftermath. Yet if he’d discussed it privately, his mother may have moved to eliminate the possibility while he was out of the country. The brutality of the murder certainly suggests a vengeance theme.

Incidentally, while the death of Europa at Olympias’s hands (and Eurydike’s subsequent suicide) is not securely dated in our sources—except that Alexander wasn’t in Pella—it almost certainly occurred in the first months after Philip’s death, during Alexander’s first trip into the Greek south, to shore up support for the Persian invasion and re-ratify the Corinthian League.

As for how their marriage may have changed things…it would almost certainly have put Alexander under the thumb of Attalos-Parmenion. We can see, in the appointments of his two sons, that Parmenion alone held great sway in Alexander’s early years—but at least he wasn’t an in-law. For once, Olympias and Antipatros were likely on the same side. (Antipatros and Parmenion weren’t precisely friendly.) If, as I suspect, Philip made that marriage for political reasons, it suggests the Attalos faction—whatever that entailed—was strong enough to force Philip’s hand before leaving on a probable long-term campaign. That means Attalos was powerful. And a 20-year-old Alexander was no match for him, even if adolescent arrogance may have made him think he was. Olympias may also have decided/suspected that the Attalos-Parmenion tie wasn’t as strong as Alexander feared—which proved to be true. When push came to shove, Parmenion allowed Attalos to be eliminated on Alexander’s order.

Arrian glosses over all this. I wish we had the first two books of Curtius, who likely covered the story of Alexander’s accession in more detail. It would provide more clues. Attalos sorta comes out of nowhere at the end of Philip’s life. Although Diodoros’ account of his reign is so truncated we don’t know the marshals under Philip well, so he may have been around longer than it seems.

————-

* Alexander knew his mythology. Theseus’s second wife, Phaidra, was reportedly cursed to conceive a passion for her (more age-appropriate) son-in-law, Hippolytos. Yet Hippolytos had pledged his virginity to Artemis, offending Aphrodite, who was behind the curse. When Hippolytos rebuked poor Phaedra’s advances, she suicided, leaving a note implicating Hippolytos (for rape). As punishment, Theseus asked his father Poseidon to kill his son. While out in his chariot, a sea monster spooked the horses, he fell out the back but got tangled in the reins, and they dragged him to death. A variation exists in which Aisklepios brings him back from death but Hades is so offended/(worried) by this power, he asks his brother Zeus to strike down Aisklepios by lightning…which he does. One of the few cases of a god dying. (They’re immortal, yes…but can be killed; it’s just that few things can kill one. Being fried by lightning will do it.)

#asks#Kleopatra-Eurydike#Alexander the Great#Philip II#Attalos#Attalus#Cleopatra-Eurydice#Olympias#Macedonian marriage#Parmenion#ancient Macedonia#Alexander the Great's early years#ancient Greece#Classics

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The queen [Cleopatra Selene II] and Juba arrived in Mauretania at the end of 25 BC, taking up residence at a place called Iol, on the coast (modern Cherchel in Algeria). It was originally a Carthaginian outpost that had been developed as a Mauretanian royal city in the second century BC. Its location probably had much to do with the presence of an island immediately offshore (the modern Corniche des Dahra) that provided a certain amount of shelter on a coast otherwise lacking it; except for this, the site of Iol is hardly propitious, with virtually no coastal plain and mountains rising high behind the city. Iol was probably in decline when the new monarchs arrived, and they chose to live there presumably because it lay roughly midway along the lengthy Mediterranean coast of Mauretania. In the emerging fashion of the era, Iol was renamed Kaisareia, or Caesarea, honoring Augustus; cities with such names were founded by allied monarchs during much of the last quarter of the first century BC.

[...] Decayed Iol was rebuilt lavishly, with all kinds of marble used in constructing the royal city, including Italian, Greek, and African. How much Cleopatra Selene participated in this architectural transformation is not known—the city did include a temple to Isis, her mother’s alter ego—but her efforts are most apparent in the artistic program of the kingdom. As the exiled queen of Egypt, she took care to commemorate her heritage. She would have felt devoted to her mother’s legacy: at the time that she became queen, the demonization of Cleopatra VII was being vigorously asserted in contemporary Latin literature, and Cleopatra Selene would have taken no comfort in reading that her mother was merely the cowardly Egyptian mate of Antonius or that her death caused great rejoicing. As her only living descendant, she had not only the chance but the obligation to set the record straight by commemorating her mother at her new capital, especially through portrait sculpture.

It may seem that she took a personal risk in promoting her mother’s heritage so vigorously, given the official opinion in Rome, but this suggests that the attitude toward Cleopatra VII was far more nuanced than is generally believed today, and the official point of view—mostly vividly represented in Augustan poetry—was essentially government propaganda. Moreover, Cleopatra Selene was a daughter of Antonius, whose other living descendants were still quite active in the political life of Rome. Her status—as well as the memory of her mother—is well shown on her coinage; a series of autonomous issues (without the name of her husband) having the legend “Kleopatra basilissa” demonstrates royal privileges separate from his. Some of these coins have the Nile crocodile, a reminder not only of Egypt but also of the coins issued in the 30s BC when she was named queen of the Cyrenaica. Juba also had his autonomous coins, indicating that the two monarchs acted independently of one another in certain undefined ways. There was also joint coinage, but even here the distinction between the two is apparent, since Juba’s legend is always in Latin while Cleopatra Selene’s is in Greek—emphasizing the bilingual nature of the court—and the two monarchs appear on opposite sides of the coins, never together. In at least one case, Cleopatra is identified merely as “Selene,” a memory of the role that she was destined to play before the collapse of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Most significantly, she also issued coins with the legend “queen Cleopatra, daughter of Cleopatra,” strong evidence of her devotion to her mother’s memory.

Cleopatra Selene’s emphasis on her Ptolemaic heritage was also apparent in the sculptural program at Caesarea. In addition to the expected portraiture of herself and her mother, there was an elaborate display of historical Egyptian sculpture, from as far back as the time of Tuthmosis I (reigned ca. 1504-1492 bc). There was also a statue of the Egyptian god Ammon, and he and Isis appeared on the obverse and reverse of the joint coinage, suggesting divine roles for the monarchs.

Perhaps the most interesting sculpture at Caesarea is a statue of the Egyptian priest Petubastes IV, who died (according to the inscription) 31 July 30 BC at the age of sixteen. He was perhaps a cousin of Cleopatra Selene and, as a member of the priestly aristocracy, would have been the last indigenous claimant to the Egyptian throne. There is little doubt that he and Cleopatra Selene knew each other in Alexandria, and the setting up of his statue in Caesarea is the most tangible evidence of her memory of that last summer in Egypt. As much as possible, she sought both to establish herself as the last Ptolemaic queen and to create a new Alexandria at Caesarea, bringing Egyptian material culture from more than fifteen hundred miles away.

— Duane W. Roller, Cleopatra’s Daughter and Other Royal Women of the Augustan Era

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm sorry but these quotes LITERALLY are Julius Caesar x Cleopatra VII, Louis XIV x Francoise D'Aubigne, Hades x Persephone, Loki x Sigyn, Suleiman x Hurrem, Ramses II x Nefertari, Genghis x Borte and Saladin x Ismat in a nutshell

🤯🤯🤯🤯

#ramses ii x nefertari#genghis x borte#saladin x ismat#hades x persephone#loki x sigyn#louis xiv x francoise d'aubigne#julius caesar x cleopatra vii#suleiman x hurrem#power couples

7 notes

·

View notes