#Christianity and Slavery: The role of the Church

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

received an email yesterday concerning an article I wrote some time ago. The person asked me so many interesting and thought-provoking questions in that email. In this follow-up post, I will try to answer some of those questions to the best of my knowledge.

What role did the church play in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade? What exactly does the Bible say about slavery? Is Christianity a “slave religion”? Why so many black people love the church and the Bible?

According to Jomo Kenyatta, the founding father and first president of Kenya, “When the missionaries arrived, the Africans had the land and the missionaries had the Bible. They taught us how to pray with our eyes closed. When we opened them, they had the land and we had the Bible”.

That was the beginning of the European colonization of Africa. As I said in my other post, the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade was introduced by the coming of the Europeans. The Europeans came with the Bible the same way the Arab raiders and traders from the Middle East and North Africa introduced Islam and the Quran through the Trans-Saharan Slave Trade. So yes, the church did play a major role in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. In fact, the church was the backbone of the slave trade.

In other words, most of the slave traders and slave ship captains were very “good” Christians. For example, Sir John Hawkins, the first slave ship captain to bring African slaves to the Americas, was a religious gentleman who insisted that his crew “serve God daily” and “love another”. His ship, ironically called “the good ship Jesus,” left the shores of his native England for Africa in October 1562.

The church, especially the Roman Catholic and the Anglican Churches, had plantations with slaves working on them. For example, the United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (USPG) – the world's oldest Anglican mission agency, owned several acres of slave plantations. It has been documented that the 800 acre Codrington slave plantation in Barbados was owned and operated by the United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (USPG) during the 18th and 19th centuries.

One may ask, why would the church condone such barbaric acts as slavery? Well, the answer lies in the Bible the same way the answer for extremist Islamic terrorism in the world today lies in the Quran. Yes, slavery isn't just "normal" in the Bible. It is perfectly OK (or can be interpreted so) according to the scriptures. There are several chapters and verses supporting slavery in both the old and new testaments of the Bible.

Exodus 21 of the old testament of the Bible for example, gives clear instructions on how to treat a slave. Both Deuteronomy 20:10-14 and Leviticus 25:44-46 also give clear instructions on who should be slaves, how and where to buy slaves, etc.

Some Christians argue those chapters and verses are in the old testament and therefore don’t count but that is heresy. Also, there are several chapters and verses supporting slavery even in the New testament of the Bible. For example, the book of Ephesians 6:5 of the New Testament clearly states “Slaves, Obey your earthly masters with deep respect and fear. Serve them sincerely as you would serve Christ”. Not just that, 1 Timothy 6:1 of the New Testament also clearly states “Christians who are slaves should give their masters full respect so that the name of God and his teaching will not be shamed”. I can go on and on.

Slavery existed during the time of Jesus and continued after Jesus. Slavery got abolished nearly 2000 years after the death of Jesus. Jesus had every chance to speak against slavery. The question is, did he do it? And if Jesus did speak against slavery then why did his followers twist his words? If Jesus did speak against slavery then why does the New Testament of the Bible support slavery? And if the Bible got twisted along the way then does it make much sense for us to put our trust in it?

Now back to the question, "Is Christianity a slave religion?" Well, I am not that great with the Bible so I will leave that to the experts to answer.

Reverend Richard Furman, President of the South Carolina Baptist convention 1823 said, “The right of holding slaves is clearly established in the holy scriptures, both by precepts and by example”.

In a letter to the Emancipator in 1839, the Reverend Thomas Witherspoon of the Presbyterian church of Alabama in the USA wrote, “I draw my warrant from the scriptures of the old and new testaments to hold the slave in bondage”.

"The extracts from Holy Writ unequivocally assert the right of property in slaves"--Rev. E.D. Simms, professor, Randolph-Macon College. I can go on and on.

So as we can see, the church and the early Christians saw nothing wrong with slavery and fully engaged themselves. Most churches and cathedrals owned several acres of slave plantations and owned several slaves. Even when slavery was abolished, most churches had to be compensated for setting their slaves free.

Yes, one of the ironies of the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act was that, it was slave owners, not the slaves, who were compensated at the emancipation of slaves. The Anglican Church received 8,823 pound sterling in compensation for its loss of over 400 slaves. The Bishop of Exeter, along with three of his colleagues received some 13,000 pounds in compensation for over 660 slaves. All these have been documented and I can go on and on.

Why so many black people love the church and the Bible? Well, that is a question I cannot answer all alone.

#Christianity and Slavery: The role of the Church#slavery#church#catholic church#anglican church#christians#slavery in america

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

my USAmerican sisters:

NEVER forget that when it came down to rapists or competency, men overwhelmingly chose a rapist and pedophile to represent their values. MEN ARE NOT RATIONAL VOTERS.

NEVER forget that MOC sold you down river for their own perceived gain of supremacy over you. They would rather elect someone who would grant police immunity than side with you. You have no solidarity with them.

NEVER forget that racism cost women and girls the right to their bodies and that racism is a threat to feminism. NEVER underestimate how divisive of an issue it is between women.

NEVER forget the role (CHRISTIAN) religion played in justifying the "natural order" of women's subjugation, torment, slavery and abuse--that religious propaganda was instrumental in securing the male status quo. that MANY churches encouraged a vote for a rapist pedophile if not split votes. (stop assuming religious people have morals)

NEVER forget that when it came to credentials, none of it ever mattered to men - their only concern was maintaining power over you.

NEVER underestimate white supremacy and male supremacy as drivers in societal regress and don't ever think you're even remotely out of the woods when the rights you were born with are now ones you have to fight for.

416 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why People Are Wrong About the Puritans of the English Civil War and New England

Oh well, if you all insist, I suppose I can write something.

(oh good, my subtle scheme is working...)

Introduction:

So the Puritans of the English Civil War is something I studied in graduate school and found endlessly fascinating in its rich cultural complexity, but it's also a subject that is popularly wildly misunderstood because it's caught in the jaws of a pair of distorted propagandistic images.

On the one hand, because the Puritans settled colonial New England, since the late 19th century they've been wrapped up with this nationalist narrative of American exceptionalism (that provides a handy excuse for schoolteachers to avoid talking about colonial Virginia and the centrality of slavery to the origins of the United States). If you went to public school in the United States, you're familiar with the old story: the United States was founded by a people fleeing religious persecution and seeking their freedom, who founded a society based on social contracts and the idea that in the New World they were building a city on a hill blah blah America is an exceptional and perfect country that's meant to be an example to the world, and in more conservative areas the whole idea that America was founded as an explicitly Christian country and society. Then on the other hand, you have (and this is the kind of thing that you see a lot of on Tumblr) what I call the Matt Damon-in-Good-Will-Hunting, "I just read Zinn's People's History of the United States in U.S History 101 and I'm home for my first Thanksgiving since I left for colleg and I'm going to share My Opinions with Uncle Burt" approach. In this version, everything in the above nationalist narrative is revealed as a hideous lie: the Puritans are the source of everything wrong with American society, a bunch of evangelical fanatics who came to New England because they wanted to build a theocracy where they could oppress all other religions and they're the reason that abortion-banning, homophobic and transphobic evangelical Christians are running the country, they were all dour killjoys who were all hopelessly sexually repressed freaks who hated women, and the Salem Witch Trials were a thing, right?

And if anyone spares a thought to examine the role that Puritans played in the English Civil War, it basically short-hands to Oliver Cromwell is history's greatest monster, and didn't they ban Christmas?

Here's the thing, though: as I hope I've gotten across in my posts about Jan Hus, John Knox, and John Calvin, the era of the Reformation and the Wars of Religion that convulsed the Early Modern period were a time of very big personalities who were complicated and not very easy for modern audiences to understand, because of the somewhat oblique way that Early Modern people interpreted and really believed in the cultural politics of religious symbolism. So what I want to do with this post is to bust a few myths and tease out some of the complications behind the actual history of the Puritans.

Did the Puritans Experience Religious Persecution?

Yes, but that wasn't the reason they came to New England, or at the very least the two periods were divided by some decades. To start at the beginning, Puritans were pretty much just straightforward Calvinists who wanted the Church of England to be a Calvinist Church. This was a fairly mainstream position within the Anglican Church, but the "hotter sort of Protestant" who started to organize into active groups during the reigns of Elizabeth and James I were particularly sensitive to religious symbolism they (like the Hussites) felt smacked of Catholicism and especially the idea of a hierarchy where clergy were a better class of person than the laity.

So for example, Puritans really first start to emerge during the Vestments Controversy in the reign of Edward VI where Bishop Hooper got very mad that Anglican priests were wearing the cope and surplice, which he thought were Catholic ritual garments that sought to enhance priestly status and that went against the simplicity of the early Christian Church. Likewise, during the run-up to the English Civil War, the Puritans were extremely sensitive to the installation of altar rails which separated the congregation from the altar - they considered this to be once again a veneration of the clergy, but also a symbolic affirmation of the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation.

At the same time, they were not the only religious faction within the Anglican Church - and this is where the religious persecution thing kicks in, although it should be noted that this was a fairly brief but very emotionally intense period. Archbishop William Laud was a leading High Church Episcopalian who led a faction in the Church that would become known as Laudians, and he was just as intense about his religious views as the Puritans were about his. A favorite of Charles I and a first advocate of absolutist monarchy, Laud was appointed Archbishop of Canturbury in 1630 and acted quickly to impose religious uniformity of Laudian beliefs and practices - ultimately culminating in the disastrous decision to try imposing Episcopalianism on Scotland that set off the Bishop's Wars. The Puritans were a special target of Laud's wrath: in addition to ordering the clergy to do various things offensive to Puritans that he used as a shibboleth to root out clergy with Puritan sympathies and fire them from their positions in the Church, he established official religious censors who went after Puritan writers like William Prynne for seditious libel and tortured them for their criticisms of his actions, cropping their ears and branding them with the letters SL on their faces. Bringing together the powers of Church and State, Laud used the Court of Star Chamber (a royal criminal court with no system of due process) to go after anyone who he viewed as having Puritan sympathies, imposing sentences of judicial torture along the way.

It was here that the Puritans began to make their first connections to the growing democratic movement in England that was forming in opposition to Charles I, when John Liliburne the founder of the Levellers was targeted by Laud for importing religious texts that criticized Laudianism - Laud had him repeatedly flogged for challenging the constitutionality of the Star Chamber court, and "freeborn John" became a martyr-hero to the Puritans.

When the Long Parliament met in 1640, Puritans were elected in huge numbers, motivated as they were by a combination of resistance to the absolutist monarchism of Charles I and the religious policies of Archbishop Laud - who Parliament was able to impeach and imprison in the Tower of the London in 1641. This relatively brief period of official persecution that powerfully shaped the Puritan mindset was nevertheless disconnected from the phenomena of migration to New England - which had started a decade before Laud became Archbishop of Canterbury and continued decades after his impeachment.

The Puritans Just Wanted to Oppress Everyone Else's Religion:

This is the very short-hand Howard Zinn-esque critique we often see of the Puritan project in the discourse, and while there is a grain of truth to it - in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Congregational Church was the official state religion, no other church could be established without permission from the Congregational Church, all residents were required to pay taxes to support the Congregational Church, and only Puritans could vote. Moreover, there were several infamous incidents where the Puritan establishment put Anne Hutchinson on trial and banished her, expelled Roger Williams, and hanged Quakers.

Here's the thing, though: during the Early Modern period, every single side of every single religious conflict wanted to establish religious uniformity and oppress the heretics: the Catholics did it to the Protestants where they could mobilize the power of the Holy Roman Emperor against the Protestant Princes, the Protestants did it right back to the Catholics when Gustavus Adolphus' armies rolled through town, the Lutherans and the Catholics did it to the Calvinists, and everybody did it to the Anabaptists.

That New England was founded as a Calvinist colony is pretty unremarkable, in the final analysis. (By the by, both Hutchinson and Williams were devout if schismatic Puritans who were firmly of the belief that the Anglican Church was a false church.) What's more interesting is how quickly the whole religious project broke down and evolved into something completely different.

Essentially, New England became a bunch of little religious communes that were all tax-funded, which is even more the case because the Congregationalist Church was a "gathered church" where the full members of the Church (who were the only people allowed to vote on matters involving the church, and were the only ones who were allowed to be given baptism and Communion, which had all kinds of knock-on effects on important social practices like marriages and burials) and were made up of people who had experienced a conversion where they can gained an assurance of salvation that they were definitely of the Elect. You became a full member by publicly sharing your story of conversion (which had a certain cultural schema of steps that were supposed to be followed) and having the other full members accept it as genuine.

This is a system that works really well to bind together a bunch of people living in a commune in the wilderness into a tight-knit community, but it broke down almost immediately in the next generation, leading to a crisis called the Half-Way Covenant.

The problem was that the second generation of Puritans - all men and women who had been baptized and raised in the Congrgeationalist Church - weren't becoming converted. Either they never had the religious awakening that their parents had had, or their narratives weren't accepted as genuine by the first generation of commune members. This meant that they couldn't hold church office or vote, and more crucially it meant that they couldn't receive the sacrament or have their own children baptized.

This seemed to suggest that, within a generation, the Congregationalist Church would essentially define itself into non-existence and between the 1640s and 1650s leading ministers recommended that each congregation (which was supposed to decide on policy questions on a local basis, remember) adopt a policy whereby the children of baptized but unconverted members could be baptized as long as they did a ceremony where they affirmed the church covenant. This proved hugely controversial and ministers and laypeople alike started publishing pamphlets, and voting in opposing directions, and un-electing ministers who decided in the wrong direction, and ultimately it kind of broke the authority of the Congregationalist Church and led to its eventual dis-establishment.

The Puritans are the Reason America is So Evangelical:

This is another area where there's a grain of truth, but ultimately the real history is way more complicated.

Almost immediately from the founding of the colony, the Puritans begin to undergo mutation from their European counterparts - to begin with, while English Puritans were Calvinists and thus believed in a Presbyterian form of church government (indeed, a faction of Puritans during the English Civil War would attempt to impose a Presbyterian Church on England.), New England Puritans almost immediately adopted a congregationalist system where each town's faithful would sign a local religious constitution, elect their own ministers, and decide on local governance issues at town meetings.

Essentially, New England became a bunch of little religious communes that were all tax-funded, which is even more the case because the Congregationalist Church was a "gathered church" where the full members of the Church (who were the only people allowed to vote on matters involving the church, and were the only ones who were allowed to be given baptism and Communion, which had all kinds of knock-on effects on important social practices like marriages and burials) and were made up of people who had experienced a conversion where they can gained an assurance of salvation that they were definitely of the Elect. You became a full member by publicly sharing your story of conversion (which had a certain cultural schema of steps that were supposed to be followed) and having the other full members accept it as genuine.

This is a system that works really well to bind together a bunch of people living in a commune in the wilderness into a tight-knit community, but it broke down almost immediately in the next generation, leading to a crisis called the Half-Way Covenant.

The problem was that the second generation of Puritans - all men and women who had been baptized and raised in the Congrgeationalist Church - weren't becoming converted. Either they never had the religious awakening that their parents had had, or their narratives weren't accepted as genuine by the first generation of commune members. This meant that they couldn't hold church office or vote, and more crucially it meant that they couldn't receive the sacrament or have their own children baptized.

This seemed to suggest that, within a generation, the Congregationalist Church would essentially define itself into non-existence and between the 1640s and 1650s leading ministers recommended that each congregation (which was supposed to decide on policy questions on a local basis, remember) adopt a policy whereby the children of baptized but unconverted members could be baptized as long as they did a ceremony where they affirmed the church covenant. This proved hugely controversial and ministers and laypeople alike started publishing pamphlets, and voting in opposing directions, and un-electing ministers who decided in the wrong direction, and accusing one another of being witches. (More on that in a bit.)

And then the Great Awakening - which to be fair, was a major evangelical effort by the Puritan Congregationalist Church, so it's not like there's no link between evangelical - which was supposed to promote Congregational piety ended up dividing the Church and pretty soon the Congregationalist Church is dis-established and it's safe to be a Quaker or even a Catholic on the streets of Boston.

But here's the thing - if we look at which denominations in the United States can draw a direct line from themselves to the Congregationalist Church of the Puritans, it's the modern Congregationalists who are entirely mainstream Protestants whose churches are pretty solidly liberal in their politics, the United Church of Christ which is extremely cultural liberal, and it's the Unitarian Universalists who are practically issued DSA memberships. (I say this with love as a fellow comrade.)

By contrast, modern evangelical Christianity (although there's a complicated distinction between evangelical and fundamentalist that I don't have time to get into) in the United States is made up of an entirely different set of denominations - here, we're talking Baptists, Pentacostalists, Methodists, non-denominational churches, and sometimes Presbyterians.

The Puritans Were Dour Killjoys Who Hated Sex:

This one owes a lot to Nathaniel Hawthorne's Scarlet Letter.

The reality is actually the opposite - for their time, the Puritans were a bunch of weird hippies. At a time when most major religious institutions tended to emphasize the sinful nature of sex and Catholicism in particular tended to emphasize the moral superiority of virginity, the Puritans stressed that sexual pleasure was a gift from God, that married couples had an obligation to not just have children but to get each other off, and both men and women could be taken to court and fined for failing to fulfill their maritial obligations.

The Puritans also didn't have much of a problem with pre-marital sex. As long as there was an absolute agreement that you were going to get married if and when someone ended up pregnant, Puritan elders were perfectly happy to let young people be young people. Indeed, despite the objection of Jonathan Edwards and others there was an (oddly similar to modern Scandinavian customs) old New England custom of "bundling," whereby a young couple would be put into bed together by their parents with a sack or bundle tied between them as a putative modesty shield, but where everyone involved knew that the young couple would remove the bundle as soon as the lights were turned out.

One of my favorite little social circumlocutions is that there was a custom of pretending that a child clearly born out of wedlock was actually just born prematurely to a bride who was clearly nine months along, leading to a rash of surprisingly large and healthy premature births being recorded in the diary of Puritan midwife Martha Ballard. Historians have even applied statistical modeling to show that about 30-40% of births in colonial America were pre-mature.

But what about non-sexual dourness? Well, here we have to understand that, while they were concerned about public morality, the Puritans were simultaneously very strict when it came to matters of religion and otherwise normal people who liked having fun. So if you go down the long list of things that Puritans banned that has landed them with a reputation as a bunch of killjoys, they usually hide some sort of religious motivation.

So for example, let's take the Puritan iconoclastic tendency to smash stained glass windows, whitewash church walls, and smash church organs during the English Civil War - all of these things have to do with a rejection of Catholicism, and in the case of church organs a belief that the only kind of music that should be allowed in church is the congregation singing psalms as an expression of social equality. At the same time, Puritans enjoyed art in a secular context and often had portraits of themselves made and paintings hung on their walls, and they owned musical instruments in their homes.

What about the wearing nothing but black clothing? See, in our time wearing nothing but black is considered rather staid (or Goth), but in the Early Modern period the dyes that were needed to produce pure black cloth were incredibly expensive - so wearing all black was a sign of status and wealth, hence why the Hapsburgs started emphasizing wearing all-black in the same period. However, your ordinary Puritan couldn't afford an all-black attire and would have worn quite colorful (but much cheaper) browns and blues and greens.

What about booze and gambling and sports and the theater and other sinful pursuits? Well, the Puritans were mostly ok with booze - every New England village had its tavern - but they did regulate how much they could serve, again because they were worried that drunkenness would lead to blasphemy. Likewise, the Puritans were mostly ok with gambling, and they didn't mind people playing sports - except that they went absolutely beserk about drinking, gambling, and sports if they happened on the Sabbath because the Puritans really cared about the Sabbath and Charles I had a habit of poking them about that issue. They were against the theater because of its association with prostitution and cross-dressing, though, I can't deny that. On the other hand, the Puritans were also morally opposed to bloodsports like bear-baiting, cock-fighting, and bare-knuckle boxing because of the violence it did to God's creatures, which I guess makes them some of the first animal rights activsts?

They Banned Christmas:

Again, this comes down to a religious thing, not a hatred of presents and trees - keep in mind that the whole presents-and-trees paradigm of Christmas didn't really exist until the 19th century and Dickens' Christmas Carol, so what we're really talking about here is a conflict over religious holidays - so what people were complaining about was not going to church an extra day in the year. I don't get it, personally.

See, the thing is that Puritans were known for being extremely close Bible readers, and one of the things that you discover almost immediately if you even cursorily read the New Testament is that Christ was clearly not born on December 25th. Which meant that the whole December 25th thing was a false religious holiday, which is why they banned it.

The Puritans Were Democrats:

One thing that I don't think Puritans get enough credit for is that, at a time when pretty much the whole of European society was some form of monarchist, the Puritans were some of the few people out there who really committed themselves to democratic principles.

As I've already said, this process starts when John Liliburne, an activist and pamphleteer who promoted the concept of universal human rights (what he called "freeborn rights"), took up the anti-Laudian cause and it continued through the mobilization of large numbers of Puritans to campaign for election to the Long Parliament.

There, not only did the Puritans vote to revenge themselves on their old enemy William Laud, but they also took part in a gradual process of Parliamentary radicalization, starting with the impeachment of Strafford as the architect of arbitrary rule, the passage of the Triennal Acts, the re-statement that non-Parliamentary taxation was illegal, the Grand Remonstrance, and the Militia Ordinance.

Then over the course of the war, Puritans served with distinction in the Parliamentary army, especially and disproportionately in the New Model Army where they beat the living hell out of the aristocratic armies of Charles I, while defying both the expectations and active interference of the House of Lords.

At this point, I should mention that during this period the Puritans divided into two main factions - Presbyterians, who developed a close political and religious alliance with the Scottish Covenanters who had secured the Presbyterian Church in Scotland during the Bishops' Wars and who were quite interested in extending an established Presbyterian Church; and Independents, who advocated local congregationalism (sound familiar) and opposed the concept of established churches.

Finally, we have the coming together of the Independents of the New Model Army and the Leveller movement - during the war, John Liliburne had served with bravery and distinction at Edgehill and Marston Moore, and personally capturing Tickhill Castle without firing a shot. His fellow Leveller Thomas Rainsborough proved a decisive cavalry commander at Naseby, Leicester, the Western Campaign, and Langport, a gifted siege commander at Bridgwater, Bristol, Berkeley Castle, Oxford, and Worcester. Thus, when it came time to hold the Putney Debates, the Independent/Leveller bloc had both credibility within the New Model Army and the only political program out there. Their proposal:

redistricting of Parliament on the basis of equal population; i.e one man, one vote.

the election of a Parliament every two years.

freedom of conscience.

equality under the law.

In the context of the 17th century, this was dangerously radical stuff and it prompted Cromwell and Fairfax into paroxyms of fear that the propertied were in danger of being swamped by democratic enthusiasm - leading to the imprisonment of Lilburne and the other Leveller leaders and ultimately the violent suppression of the Leveller rank-and-file.

As for Cromwell, well - even the Quakers produced Richard Nixon.

#history#puritans#calvinism#english civil war#oliver cromwell#the stupid meme about christmas#new england#protestantism

449 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Holiness Hoodoo: Rediscovering Ancestral Roots Without Jesus"

The term "Holiness Hoodoo" may leave some people puzzled, so allow me to clarify its meaning. In my view, Holiness Hoodoo represents a return to the traditional practices of my ancestral lineage, a way to decipher who I am and what my purpose entails. Many of our forebears were devout Christians, and this undeniable fact forms the backdrop of my spiritual journey. Despite the complex relationship that many Black Americans have with the Bible due to the scars of slavery, it's essential to remember that it wasn't the Bible itself that caused harm, but the people wielding it as a tool of oppression.

As I delved deeper into the realms of ancestral magic, I began to notice striking parallels with church practices. To some, I seemed too "churchy" for hoodoo, and to others, too "hoodoo" for the church—there appeared to be no middle ground. However, I've come to understand that my connection to my ancestors is the cornerstone of my spiritual practice. I've realized that perhaps the reason some individuals struggle to communicate with their spirits is that they try to venerate them through African traditions, tarot, or other methods their ancestors might not recognize.

The Bible, as a potent tool in hoodoo, is not revered because we live by its teachings but because it contains powerful scriptures. My mother, for instance, believed in Jesus, yet she was a practitioner of hoodoo—a tongue-speaking, spirit-conjuring woman. Her approach, which I now embrace, is what I refer to as "Holiness Hoodoo."

So, what does Holiness Hoodoo look like for me?

1. Setting the Atmosphere:

I play inspirational or gospel music that resonates with my specific needs, allowing it to fill my home as I clean, pray, or perform spiritual work. Gospel music serves as a direct conduit to my ancestral spirits, and sometimes, when I hear a song I haven't listened to in a while, an ancestor's presence is assured.

2. Keeping a Bible on the Altar:

While I don't read the Bible frequently, I keep it open to the Psalms as an offering to my spirits. The Bible also serves as a powerful tool of protection, and specific verses and pages can function as talismans and petitions.

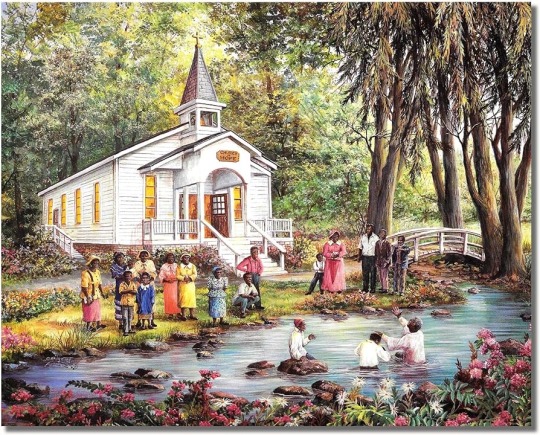

3. Baptisms:

Baptism, in my lineage, is a ritual practice to wash ourselves of sins and start anew. It's not just for babies; it can also cleanse generational curses and traumas passed down from parents.

4. Shouting:

Listening to gospel music, I engage in the practice of shouting, a form of ecstatic dance that connects me with my spirits. This practice fills me with light and often results in downloads of ancestral wisdom.

5. Laying of Hands:

I perform the laying of hands, a practice I'll discuss in more detail in the future. It's distinct from Reiki and is a significant part of my spiritual tradition.

6. Fasting:

Fasting is a part of my spiritual practice, serving as a means of both elevating my spiritual consciousness and cleansing my body. I firmly believe that one's health plays a pivotal role in their spiritual journey.

Holiness Hoodoo is about preserving the traditions of our ancestors and finding connections with them. It doesn't rely on dogma or strict religious doctrine; instead, it is a pathway to tap into the wisdom and spirituality that has been passed down through generations. In this practice, there is no room for being "too churchy" or "too hoodoo"—it's about embracing the rich tapestry of our heritage and harnessing it for a profound and authentic spiritual experience.

Please make sure you SHARE! SHARE! SHARE! For more if you enjoyed this post.

Don’t forget My MInd and Me inc is still seeking donors for The Peoples Praise House! Even if you cannot donate, SHARE ! Thank you !

@conjuhwoeman on twitter

@realconjuhwoeman on IG

#hoodoo#medium#ancestor veneration#witch#rootwork#black women#conjure#prophet#tutnese#luxury#traditional hoodoo#holiness

139 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have this theory that progressive Christianity and liberal Christianity are different, and I'm putting in this ask to get the opinion of a progressive Christian on the issue.

The way I'd define it is that progressive Christianity is the belief that Christianity should be aligned with progressive social movements, while liberal Christianity is the belief that the Bible, while a book about God, was not inspired by God.

For example, I've heard that Side A Christians in Evangelicalism will argue that the Bible doesn't condemn same-sex relationships (at least not as we have them), while Side A Christians in mainline churches often think that the Bible does condemn same-sex relationships and the Bible is wrong about this.

The thought came to me thinking about the theologians who supported Nazism (here's a good resource on them); they were clearly liberal theologians - they thought that Christianity should move on from the Old Testament - but self-evidently not progressive theologians.

How interesting! And I will respond to your other one too - just gathering my thoughts.

I'd tend to agree with you on your definition - as a self-proclaimed progressive Christian, I believe that Christianity (should be) a liberation theology. 'Even' in the OT/HB, if Christians move away from that, the focus is on the liberation of a persecuted and abused people, and this message is made more personal and clearer in the NT with Jesus and his rejection of religious establishments that weren't so hot on this idea of loving everyone. We can see so many examples in history of this conflict between Christianity used as justification for an oppressive regime (eg slavery) and recognition in its true form as a liberation theology (eg Black theology, notably in apartheid South Africa, and women's role in this - here's a really interesting article by Isabel Phiri on this.)

I'm inclined to your definition of liberal too. It's never been a word I've really associated myself with. Personally, I believe that the Bible is inspired by God, and infallible, but that we have to remember that it was written by real people in a real time in a different society with its own concerns that were likely very different from ours, and these influences will and do show through. We can see this even in differences between accounts - what different gospels emphasise and pay attention to, even completely disagreeing at points. A great example of this is the writing and interpretation of the well-known 'clobber verses' under Roman rule. I think I've mentioned this before, and I still haven't found the article I'm talking about, but if I do I'll edit, but essentially the author argues that as Christianity found its feet in being a religion of equality and love and doing the right thing, it was undoubtedly influenced by Roman persecution, and Romans, as well as persecuting them, were also doing things like men sexually abusing boy slaves, and worshipping other gods, the sects of which often incidentally contained a lot of (gay) cult sex, and therefore early Christians and apostles etc writing their book on what is right, went wow. These Romans who abuse us also abuse their slaves like that, and also worship other gods like that? That's not right, let's write that down. Anyway that's a very bad summary but this isn't the post for the detail on that - my point is, inspired by God, but not immune to the world.

'For example, I've heard that Side A Christians in Evangelicalism will argue that the Bible doesn't condemn same-sex relationships (at least not as we have them), while Side A Christians in mainline churches often think that the Bible does condemn same-sex relationships and the Bible is wrong about this.'

This bit is super interesting to me! So as everyone knows by now I'm ⋆。°✩ anglocatholic ⋆。°✩ so this is completely the opposite of what I'd believe (Side A, more? mainline church (not evangelical at least), and I believe that the Bible doesn't condemn same-sex relationships as we have them - great specification on your part). I can't really speak on this because I'll assume? that based on the word Evangelicalism this is more US focused, and, although I'm learning, I really don't know that much about US Christianity. Also for me, the Bible cannot be wrong. Idk I just think that's fundamental.

'The thought came to me thinking about the theologians who supported Nazism (here's a good resource on them); they were clearly liberal theologians - they thought that Christianity should move on from the Old Testament - but self-evidently not progressive theologians.'

Yes! This comes back to my above point about abuse and use of Christianity as a force for oppression and liberation. Really enjoyed the video you linked, would recommend too. Completely agree again, this fits totally in your definition of liberal vs progressive - taking the text liberally but without socially progressive views. Again personally I am the exact opposite, I tend to lean towards socially progressive views while maintaining a less liberal view of the Bible and liturgy etc.

Overall, I love your argument and think it's very well supported in terms of there being a difference, and your choice of words to describe each side fits very well imo. The thing I would say is that I think that it's a difficult theory to support further in this terminology. We can make a distinction between those who take the Bible as not inspired by God (and we can call them liberal) and those who hold socially progressive views (and we can call them progressive), but I'd suggest it's more a definition than a theory, if that makes sense? Because language is so subjective, I think it's difficult to theorise on the basis of two linked and often confused words, especially in the even more subjective field of personal religion. Do you know what I mean?

But, in conclusion, yes! Agree! Love it!

#progressive christianity#lgbt christian#queer christian#religion#theology#christian#christianity#musings

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Christianization of African-Americans

Postcolonial American culture's preoccupation with breaking away from Europe was far removed from the situation among Africans in the United States at the time. The initial tenacity with which African Americans held onto their indigenous practices and the reluctance of many Southern white slaveholders to teach Christianity to the slaves limited the Christianizing process in the early period. Even the Great Awakening of the 1740s, which swept the country like a hurricane, failed to reach the masses of slaves. Only with the Great Western Revival at the turn of the nineteenth century did the Christianizing process gain a significant foothold among black people. The central questions at this junction are: Why did large numbers of American black people become Christians? What features of Protestant Christianity persuaded them to become Christian? The Baptist separatists and the Methodists, religious dissenters in American religious culture, gained the attention of the majority of slaves in the Christianizing process. The evangelical outlook of these denominations stressed individual experience, equality before God, and institutional autonomy. Baptism by immersion, practiced by Baptists, may indeed have reminded slaves from Nigeria and Dahomey of African river cults, but fails to fully explain the success of the Christianizing process among Africans. Black people became Christians for intellectual, existential, and political reasons. Christianity is, as Friedrich Nietzsche has taught us and liberation theologians remind us, a religion especially fitted to the oppressed. It looks at the world from the perspective of those below. The African slaves' search for identity could find historical purpose in the exodus of Israel out of slavery and personal meaning in the bold identification of Jesus Christ with the lowly and downtrodden. Christianity also is first and foremost a theodicy, a triumphant account of good over evil. The intellectual life of the African slaves in the United States —like that of all oppressed peoples— consisted primarily of reckoning with the dominant form of evil in their lives. The Christian emphasis on against-the-evidence hope for triumph over evil struck deep among many of them. The existential appeal of Christianity to black people was the stress of Protestant evangelicalism on individual experience, and especially the conversion experience. The "holy dance" of Protestant evangelical conversion experience closely resembled the "ring shout" of West African novitiate rites: both are religious forms of ecstatic bodily behavior in which everyday time is infused with meaning and value through unrestrained rejoicing. The conversion experience played a central role in the Christianizing process. It not only created deep bonds of fellowship and a reference point for self-assurance during times of doubt and distress; it also democratized and equalized the status of all before God. The conversion experience initiated a profoundly personal relationship with God, which gave slaves a special self-identity and self-esteem in stark contrast with the roles imposed upon them by American society. The primary political appeal of the Methodists and especially of the Baptists for black people was their church polity and organizational form, free from hierarchical control, open and easy access to leadership roles, and relatively loose, uncomplicated requirements for membership. The adoption of the Baptist polity by a majority of Christian slave marked a turning point in the Afro-American experience [...] Independent control over their churches promoted the proliferation of African styles and manners within the black Christian tradition and liturgy. It also produced community-minded political leaders, polished orators, and activist journalists and scholars. In fact, the unique variant of American life that we call Afro-American culture germinated in the bosom of this Afro-Christianity, in the Afro-Christian church congregations.

- Cornel West ("Race and Modernity," from his Reader, pages 61-63, 63)

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

(LATimes) In ‘The Exvangelicals,’ Sarah McCammon tells the tale of losing her religion

Sarah McCammon.

(Kara Frame)

Book Review

The Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical Church

By Sarah McCammon St. Martin’s Press: 310 pages, $30

The term “exvangelical,” a reference to disillusioned evangelicals after Donald Trump commandeered 81% of the white evangelical vote in 2016, has always struck me as contrived and a tad too cute. It’s a variation — a reversal, I suppose — of Ronald Reagan’s famous lament that he didn’t leave the Democratic Party; the Democratic Party left him.

Although the author, a national political correspondent for NPR, purports to be telling “the stories of millions of Americans,” this book is really autobiography with a few cameo roles. Nevertheless, McCammon’s history is captivating and well told: a childhood cosseted in the evangelical subculture, with schools and sermons trumpeting the Christian nationalism that’s fueling so many culture wars now.

In “The Exvangelicals,” McCammon’s evolution unfolds as a series of steps, chapter by chapter, on a descending staircase toward disillusionment.

She begins by questioning the conviction that only Christians (by which evangelicals mean evangelicals) go to heaven, then rejects creationism and embraces the veracity of science before moving on to such matters as female submission and sexual identities.

“Having a female body came with heavy responsibility and fear,” she writes, referring to admonitions at home and school to dress modestly lest she inflame unholy passions.

Perhaps not surprisingly, McCammon devotes a great deal of attention to her own sexual awakening, much of which occurred at the small evangelical college she attended (which, as it happens, is where I was an undergraduate a couple of decades earlier). The “purity culture” of evangelicalism demanded that women be demure, while young men were cast as warriors and defenders.

“On our wedding night, we didn’t know how to have sex,” one informant tells McCammon, who adds, “That experience is not unusual for young evangelicals who begin their honeymoons with little or no sexual experience, and, often, years of sexual shame.”

Many exvangelicals testify to enduring religious trauma, some of it caused by corporal punishment or perhaps fear of the Rapture, the belief popular among evangelicals that Jesus will return soon to collect the faithful and those “left behind” will face terrible judgment. One psychotherapist cataloged the symptoms of religious trauma as “anxiety and depression, chronic pain and intestinal symptoms, feelings of shame and a tendency toward social isolation.”

Religious trauma drives many evangelicals, including the author and one of her siblings, into therapy and out of evangelicalism, though not necessarily in that order.

McCammon is especially effective at juxtaposing the condemnations of Bill Clinton’s philandering with full-throated defenses of Donald Trump’s sexual predations — the condemnations and the defenses coming from the same evangelical sources with no apparent self-awareness and no hint of irony. Even more devastating is the author’s examination of her Christian school textbooks and recollections of classroom conversations in those schools regarding slavery. One textbook conjured the halcyon days on the plantation — “Southern weather was warm and the slaves stayed healthy” — and a student recalled his teacher’s remark that bondage “was a pretty good gig for them; they got free housing and all their meals were taken care of.”

If historical accuracy and context are missing from these textbooks, however, those qualities are also lacking in McCammon’s narrative, although her missteps are not nearly so egregious. She talks about evangelicalism reaching its peak of influence “beginning in the late 1980s,” ignoring the fact that evangelicals set the nation’s social and political agenda for much of the 19th century, especially in the years before the Civil War, albeit with very different sensibilities.

The author might have explored how white evangelicalism was different before its hard-right turn in defense of racial segregation in the late 1970s. Might an understanding of evangelicalism’s generally laudable social agenda in centuries past — abolition, prison reform, public education, even women’s suffrage were all evangelical concerns — have provided McCammon and her compatriots with a standard to which they could appeal in their quest to reform their churches?

As in many coming-of-age narratives, those who leave the safety of the subculture rarely have smooth landings. McCammon’s marriage to a classmate three months after their college graduation “felt awkward and surprisingly lonely,” she writes; it ended in divorce. The author tells of her parental-enforced estrangement from her grandfather because he was gay. The two mended their relationship and became close during the final years of his life, although McCammon’s overtures to him created a rift with her mother and father.

The author’s schoolmate, Jeff, came out as gay, thereby rupturing the relationship with his parents, who refused to acknowledge his husband at their son’s graduation from seminary. “I am not an evangelical in large part because there’s no room in most of American evangelicalism for queer people,” he told the author. “I’m angry about that. I’m angry and sad for the kids that are still in evangelical churches who are being told they can’t be themselves.”

All these factors and more, together with what many evangelicals regard as the hypocritical embrace of Trump, are leading some evangelicals out of the fold. But leaving itself is traumatic, both for the individuals and for family members left behind.

McCammon quotes a South Dakota exvangelical’s angry letter to Focus on the Family, the organization partially responsible for the subculture veering to the right in the decades surrounding the turn of the 21st century. She cultivated a deep Christian faith outside of evangelicalism. “But thanks to you,” she wrote to the group, “my mother believed I was living a sinful lifestyle because of how I voted.”

“Leaving conservative evangelicalism means giving up the security of silencing some of life’s most vexing and anxiety-inducing questions with a set of ‘answers’ — about the purpose of life, human origins, and what happens after death,” McCammon writes. “It also means losing an entire community of people who could once be relied on to help celebrate weddings and new babies, organize meal trains when you’re sick and bereaved, and provide a built-in network of support and socialization around a shared set of expectations and ideals.”

McCammon insists that the challenge for her and others is to define themselves in positive rather than negative terms — they do not want to be known for what they are fleeing — in which case the label “exvangelical” isn’t exactly helpful. Nonetheless, these “expatriates” are finding safety, or at least comfort, in numbers.

“Many of us who’ve been cast out are surveying the wilderness around us,” she writes, “and finding that we’re anything but alone.”

Randall Balmer teaches religion at Dartmouth College. His most recent book is “Saving Faith: How American Christianity Can Reclaim Its Prophetic Voice.”

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

A.2.20 Why are most anarchists atheists?

It is a fact that most anarchists are atheists. They reject the idea of god and oppose all forms of religion, particularly organised religion. Today, in secularised western European countries, religion has lost its once dominant place in society. This often makes the militant atheism of anarchism seem strange. However, once the negative role of religion is understood the importance of libertarian atheism becomes obvious. It is because of the role of religion and its institutions that anarchists have spent some time refuting the idea of religion as well as propagandising against it.

So why do so many anarchists embrace atheism? The simplest answer is that most anarchists are atheists because it is a logical extension of anarchist ideas. If anarchism is the rejection of illegitimate authorities, then it follows that it is the rejection of the so-called Ultimate Authority, God. Anarchism is grounded in reason, logic, and scientific thinking, not religious thinking. Anarchists tend to be sceptics, and not believers. Most anarchists consider the Church to be steeped in hypocrisy and the Bible a work of fiction, riddled with contradictions, absurdities and horrors. It is notorious in its debasement of women and its sexism is infamous. Yet men are treated little better. Nowhere in the bible is there an acknowledgement that human beings have inherent rights to life, liberty, happiness, dignity, fairness, or self-government. In the bible, humans are sinners, worms, and slaves (figuratively and literally, as it condones slavery). God has all the rights, humanity is nothing.

This is unsurprisingly, given the nature of religion. Bakunin put it best:

"The idea of God implies the abdication of human reason and justice; it is the most decisive negation of human liberty, and necessarily ends in the enslavement of mankind, both in theory and in practice. “Unless, then, we desire the enslavement and degradation of mankind .. . we may not, must not make the slightest concession either to the God of theology or to the God of metaphysics. He who, in this mystical alphabet, begins with A will inevitably end with Z; he who desires to worship God must harbour no childish illusions about the matter, but bravely renounce his liberty and humanity. “If God is, man is a slave; now, man can and must be free; then, God does not exist.” [God and the State, p. 25]

For most anarchists, then, atheism is required due to the nature of religion. “To proclaim as divine all that is grand, just, noble, and beautiful in humanity,” Bakunin argued, “is to tacitly admit that humanity of itself would have been unable to produce it — that is, that, abandoned to itself, its own nature is miserable, iniquitous, base, and ugly. Thus we come back to the essence of all religion — in other words, to the disparagement of humanity for the greater glory of divinity.” As such, to do justice to our humanity and the potential it has, anarchists argue that we must do without the harmful myth of god and all it entails and so on behalf of “human liberty, dignity, and prosperity, we believe it our duty to recover from heaven the goods which it has stolen and return them to earth.” [Op. Cit., p. 37 and p. 36]

As well as the theoretical degrading of humanity and its liberty, religion has other, more practical, problems with it from an anarchist point of view. Firstly, religions have been a source of inequality and oppression. Christianity (like Islam), for example, has always been a force for repression whenever it holds any political or social sway (believing you have a direct line to god is a sure way of creating an authoritarian society). The Church has been a force of social repression, genocide, and the justification for every tyrant for nearly two millennia. When given the chance it has ruled as cruelly as any monarch or dictator. This is unsurprising:

“God being everything, the real world and man are nothing. God being truth, justice, goodness, beauty, power and life, man is falsehood, iniquity, evil, ugliness, impotence, and death. God being master, man is the slave. Incapable of finding justice, truth, and eternal life by his own effort, he can attain them only through a divine revelation. But whoever says revelation, says revealers, messiahs, prophets, priests, and legislators inspired by God himself; and these, as the holy instructors of humanity, chosen by God himself to direct it in the path of salvation, necessarily exercise absolute power. All men owe them passive and unlimited obedience; for against the divine reason there is no human reason, and against the justice of God no terrestrial justice holds.” [Bakunin, Op. Cit., p. 24]

Christianity has only turned tolerant and peace-loving when it is powerless and even then it has continued its role as apologist for the powerful. This is the second reason why anarchists oppose the church for when not being the source of oppression, the church has justified it and ensured its continuation. It has kept the working class in bondage for generations by sanctioning the rule of earthly authorities and teaching working people that it is wrong to fight against those same authorities. Earthly rulers received their legitimisation from the heavenly lord, whether political (claiming that rulers are in power due to god’s will) or economic (the rich having been rewarded by god). The bible praises obedience, raising it to a great virtue. More recent innovations like the Protestant work ethic also contribute to the subjugation of working people.

That religion is used to further the interests of the powerful can quickly be seen from most of history. It conditions the oppressed to humbly accept their place in life by urging the oppressed to be meek and await their reward in heaven. As Emma Goldman argued, Christianity (like religion in general) “contains nothing dangerous to the regime of authority and wealth; it stands for self-denial and self-abnegation, for penance and regret, and is absolutely inert in the face of every [in]dignity, every outrage imposed upon mankind.” [Red Emma Speaks, p. 234]

Thirdly, religion has always been a conservative force in society. This is unsurprising, as it bases itself not on investigation and analysis of the real world but rather in repeating the truths handed down from above and contained in a few holy books. Theism is then “the theory of speculation” while atheism is “the science of demonstration.” The “one hangs in the metaphysical clouds of the Beyond, while the other has its roots firmly in the soil. It is the earth, not heaven, which man must rescue if he is truly to be saved.” Atheism, then, “expresses the expansion and growth of the human mind” while theism “is static and fixed.” It is “the absolutism of theism, its pernicious influence upon humanity, its paralysing effect upon thought and action, which Atheism is fighting with all its power.” [Emma Goldman, Op. Cit., p. 243, p. 245 and pp. 246–7]

As the Bible says, “By their fruits shall ye know them.” We anarchists agree but unlike the church we apply this truth to religion as well. That is why we are, in the main, atheists. We recognise the destructive role played by the Church, and the harmful effects of organised monotheism, particularly Christianity, on people. As Goldman summaries, religion “is the conspiracy of ignorance against reason, of darkness against light, of submission and slavery against independence and freedom; of the denial of strength and beauty, against the affirmation of the joy and glory of life.” [Op. Cit., p. 240]

So, given the fruits of the Church, anarchists argue that it is time to uproot it and plant new trees, the trees of reason and liberty.

That said, anarchists do not deny that religions contain important ethical ideas or truths. Moreover, religions can be the base for strong and loving communities and groups. They can offer a sanctuary from the alienation and oppression of everyday life and offer a guide to action in a world where everything is for sale. Many aspects of, say, Jesus’ or Buddha’s life and teachings are inspiring and worth following. If this were not the case, if religions were simply a tool of the powerful, they would have long ago been rejected. Rather, they have a dual-nature in that contain both ideas necessary to live a good life as well as apologetics for power. If they did not, the oppressed would not believe and the powerful would suppress them as dangerous heresies.

And, indeed, repression has been the fate of any group that has preached a radical message. In the middle ages numerous revolutionary Christian movements and sects were crushed by the earthly powers that be with the firm support of the mainstream church. During the Spanish Civil War the Catholic church supported Franco’s fascists, denouncing the killing of pro-Franco priests by supporters of the republic while remaining silent about Franco’s murder of Basque priests who had supported the democratically elected government (Pope John Paul II is seeking to turn the dead pro-Franco priests into saints while the pro-Republican priests remain unmentioned). The Archbishop of El Salvador, Oscar Arnulfo Romero, started out as a conservative but after seeing the way in which the political and economic powers were exploiting the people became their outspoken champion. He was assassinated by right-wing paramilitaries in 1980 because of this, a fate which has befallen many other supporters of liberation theology, a radical interpretation of the Gospels which tries to reconcile socialist ideas and Christian social thinking.

Nor does the anarchist case against religion imply that religious people do not take part in social struggles to improve society. Far from it. Religious people, including members of the church hierarchy, played a key role in the US civil rights movement of the 1960s. The religious belief within Zapata’s army of peasants during the Mexican revolution did not stop anarchists taking part in it (indeed, it had already been heavily influenced by the ideas of anarchist militant Ricardo Flores Magon). It is the dual-nature of religion which explains why many popular movements and revolts (particularly by peasants) have used the rhetoric of religion, seeking to keep the good aspects of their faith will fighting the earthly injustice its official representatives sanctify. For anarchists, it is the willingness to fight against injustice which counts, not whether someone believes in god or not. We just think that the social role of religion is to dampen down revolt, not encourage it. The tiny number of radical priests compared to those in the mainstream or on the right suggests the validity of our analysis.

It should be stressed that anarchists, while overwhelmingly hostile to the idea of the Church and an established religion, do not object to people practising religious belief on their own or in groups, so long as that practice doesn’t impinge on the liberties of others. For example, a cult that required human sacrifice or slavery would be antithetical to anarchist ideas, and would be opposed. But peaceful systems of belief could exist in harmony within in anarchist society. The anarchist view is that religion is a personal matter, above all else — if people want to believe in something, that’s their business, and nobody else’s as long as they do not impose those ideas on others. All we can do is discuss their ideas and try and convince them of their errors.

To end, it should noted that we are not suggesting that atheism is somehow mandatory for an anarchist. Far from it. As we discuss in section A.3.7, there are anarchists who do believe in god or some form of religion. For example, Tolstoy combined libertarian ideas with a devote Christian belief. His ideas, along with Proudhon’s, influences the Catholic Worker organisation, founded by anarchists Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin in 1933 and still active today. The anarchist activist Starhawk, active in the current anti-globalisation movement, has no problems also being a leading Pagan. However, for most anarchists, their ideas lead them logically to atheism for, as Emma Goldman put it, “in its negation of gods is at the same time the strongest affirmation of man, and through man, the eternal yea to life, purpose, and beauty.” [Red Emma Speaks, p. 248]

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Simon of Cyrene, an African and the father of Alexander and Rufus. Carried the cross Christ would be crucified upon when Jesus became too weak to continue under its weight. Simon of Cyrene is mentioned in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke. Simon's son Rufus may have been the same man the Apostle Paul greets in his letter to Rome (the biblical Epistle of Romans), whom he calls “chosen in the Lord” and whose mother “has been a mother to me, too” (Romans 16:13). The Christian faith has always included Africans. By contrast a faith such as Mormonism didn't even allow Africans or non-white people to serve their church in leadership roles or receive "blessings" until a special "revelation from God" in 1978 instructed the church to start including them.

Below is one of Ethiopia's ancient "rock churches". Following the death and resurrection of Jesus, Ethiopia was one of the first nations in the world to build Christian churches and follow the teachings of Jesus Christ. More than 650 years before Mohammad was even born, Ethiopian Christians were singing praises to God the Father, His Son Jesus and the Holy Spirit. Islamic invaders attacked and enslaved Christian Africa in the years between their prophet's establishment of Islam and the early middle-ages, forcing Christian Africans to convert to Islam or die by the sword. Many chose to die. To this day Islam still preys on the people of Africa, giving them the choice of death, slavery or conversion.

Most people think Slavery ended in 1865. It still exists. These are black Africans in a slave market in Libya. Muslim nations still have a brisk slave trade and hundreds of thousands of black Africans are kidnapped, tortured and sold on a daily basis with the full blessing of Islamic mufti's and Islamic governments. The Western World doesn't seem to care very much because the west wants the oil these countries produce. How much is the life of a black slave in the Islamic world? About $400 U.S. dollars for a "healthy" young male.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saints&Reading; Wednesday, April 10, 2024

march 27_april 10

VENERABLE HESYCHIUS OF JERUSALEM (C.408)

He was a priest-monk renowned in the Eastern Church as a theologian, biblical commentator, and preacher. He played a prominent role in the 5th-century controversy on the nature of Christ and was acclaimed as having annotated the whole of sacred Scripture.

Serving as a priest in the church in Jerusalem c. 412, Hesychius gained repute as a theologian and catechist so that by 429, he was recognized by chroniclers and the Orthodox Mēnologion (lives of the saints liturgically arranged by month) as the pre-eminent biblical interpreter and teacher of the church in Jerusalem and Palestine.

Most of Hesychius’ writings have been lost, although scholarship in the second half of the 20th century continues to identify more of his works hidden among Greek manuscripts and Latin translations. His biblical commentaries include interpretations of the Old Testament books of Leviticus, Job, Isaiah, and Ezekiel. A celebrated moralistic annotation on the Psalms that had long been attributed to the 4th-century spokesman for orthodoxy, Athanasius of Alexandria, is now acknowledged as Hesychius’. Some earlier commentaries of probable authenticity contain germinal terminology of the heterodox Nestorians.

As a biblical exegete, Hesychius generally followed the allegorical method of the 3rd-century Christian theologian Origen of Alexandria. Hesychius’ preoccupation with symbolism led him to deny that a literal meaning could be found for every sentence in the Scriptures. In order to avoid heretical interpretations of Scripture, he rejected such philosophical terms as person, essence, or substance to express doctrine on the nature of Christ. On this point, he allowed only the term logos sarkotheis (“the word made flesh”), a biblical concept. Against the diminution of Christ’s divinity by Arius and his Antiochene followers, he veered toward the view of the Monophysites.

Credited with the earliest known liturgical addresses on the Virgin Mary, Hesychius also wrote a church history after 428 that controverted Nestorianism and other heretical beliefs. This text was incorporated into the second Council of Constantinople proceedings in 553. The works of Hesychius were published in the series Patrologia Graeca, J.-P. Migne (ed.), vol. 27, 55, and 93 (1866).

Source: Encyclopedia Britannica

THE MONKMARTYR EUSTRATIUS OF THE KIEV NEAR CAVE (1096)

Martyr Eustratius of the Caves was born in the eleventh century at Kiev into a wealthy family. As an adult, he received monastic tonsure at the Kiev Caves monastery, after giving away all his possesions to the poor. Saint Eustratius humbly underwent obediences at the monastery, strictly fulfilling the rule of prayer and passing his days in fasting and vigilance.

In 1096 the Polovetsians captured Kiev and ravaged the monastery of the Caves, doing away with many of the monks. Saint Eustratius was taken into captivity, and was sold into slavery with thirty monastic laborers and twenty inhabitants of Kiev to a certain Jew living in Korsun.

The impious Jew tried to make the captives deny Christ, threatening to kill those who refused by starving them. Saint Eustratius encouraged and exhorted his brother Christians, “Brothers! Let none of us who are baptized and believe in Christ betray the vows made at Baptism. Christ has regenerated us through water and the Spirit. He has freed us from the curse of the Law by His Blood, and He has made us heirs of His Kingdom. If we live, we shall live for the Lord. If we die, we shall die in the Lord and inherit eternal life.”

Inspired by the saint’s words, the captives resolved to die of starvation, rather than renounce Christ, Who is the food and drink of Eternal Life. Exhausted by hunger and thirst, some captives perished after three days, some after four days, and some after seven days. Saint Eustratius remained alive for fourteen days, since he was accustomed to fasting from his youth. Suffering from hunger, he still did not touch food nor water. The impious Jew, seeing that he had lost the money he had paid for the captives, decided to take revenge on the holy monk.

The radiant Feast of the Resurrection of Christ drew near, and the Jewish slave owner was celebrating the Jewish Passover with his companions. He decided to crucify Saint Eustratius. The cruel tormentors mocked the saint, offering to let him share their Passover meal. The Martyr replied, “The Lord has now bestown a great grace upon me. He has permitted me to suffer on a cross for His Name just as He suffered.” The saint also predicted a horrible death for the Jew.

Hearing this, the enraged Jew grabbed a spear and stabbed Saint Eustratius on the cross. The martyr’s body was taken down from the cross and thrown into the sea. Christian believers long searched for the holy relics of the martyr, but were not able to find them. But through the Providence of God the incorrupt relics were found in a cave and worked many miracles. Later, they were transferred to the Near Caves of the Kiev Caves monastery.

The prediction of the holy Martyr Eustratius that his blood would be avenged was fulfilled soon after his death. The Byzantine Emperor issued a decree expelling all Jews from Korsun, depriving them of their property, and putting their elders to death for torturing Christians. The Jew who crucified Saint Eustratius was hanged on a tree, receiving just punishment for his wickedness.

Source: Orthodox Church in America_OCA

ISAIAH 26:21-27:9

21 For behold, the Lord comes out of His place To punish the earth's inhabitants for their iniquity; The earth will also disclose her blood, And will no longer cover her slain.

1 In that day the Lord with His severe sword, great and strong, Will punish Leviathan the fleeing serpent, Leviathan that twisted serpent; And He will slay the reptile that is in the sea. 2 In that day sing to her, “A vineyard of red wine! 3 I, the Lord, keep it, I water it every moment; Lest any hurt it, I keep it night and day. 4 Fury is not in Me. Who would set briers and thorns Against Me in battle? I would go through them, I would burn them together. 5 Or let him take hold of My strength, That he may make peace with Me; And he shall make peace with Me.” 6 Those who come He shall cause to take root in Jacob; Israel shall blossom and bud, And fill the face of the world with fruit. 7 Has He struck Israel as He struck those who struck him? Or has He been slain according to the slaughter of those who were slain by Him? 8 In measure, by sending it away, You contended with it. He removes it with His rough wind on the day of the east wind. 9

Therefore, by this, Jacob's iniquity will be covered; and this is all the fruit of taking away his sin: When he makes all the stones of the altar like chalkstones that are beaten to dust, wooden images and incense altars shall not stand.

GENESIS 9:18-10:1

18 Now the sons of Noah who went out of the ark were Shem, Ham, and Japheth. And Ham was the father of Canaan. 19 These three were the sons of Noah, and from these the whole earth was populated. 20 And Noah began to be a farmer, and he planted a vineyard. 21 Then he drank of the wine and was drunk, and became uncovered in his tent. 22 And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brothers outside. 23 But Shem and Japheth took a garment, laid it on both their shoulders, and went backward and covered the nakedness of their father. Their faces were turned away, and they did not see their father’s nakedness. 24 So Noah awoke from his wine and knew what his younger son had done to him. 25 Then he said: “Cursed be Canaan; A servant of servants He shall be to his brethren.” 26 And he said: “Blessed be the Lord, The God of Shem, And may Canaan be his servant. 27 May God enlarge Japheth, And may he dwell in the tents of Shem; And may Canaan be his servant.” 28 And Noah lived after the flood three hundred and fifty years. 29 So all the days of Noah were nine hundred and fifty years; and he died.

1 Now this is the genealogy of the sons of Noah: Shem, Ham, and Japheth. And sons were born to them after the flood.

#orthodoxy#orthodoxchristianity#easternorthodoxchurch#originofchristianity#spirituality#holyscriptures#bible#old testament#wisdom#saints

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction

For most of the past two millennia, Christian churches have not only accepted slavery, but have also participated in the slave trade and owned human property. The ethics of Christian slaveholding, however, have changed significantly. While Christians owned other Christians without controversy during the late ancient period, Christian churches began to forbid that practice over time. By the early modern period, it was considered taboo for Christians to own other Christians, although the practice sometimes continued illegally. While some individual Christians, including ministers and members of the clergy, questioned the legitimacy of slavery during the early modern period, it was not until the 18th century that a small minority of Christian churches began to assert an abolitionist stance.

Even then, it was deeply contested. For the majority of the early modern period, most Christian churches—both Catholic and Protestant—supported slavery and benefited from the institution. Even the Quakers (Society of Friends), who were leaders in the abolitionist movement, took a century to disown enslavers from their congregations. In the United States, many Christian denominations split on the issue of slavery in the 19th century, and Christian ministers and missionaries developed robust defenses of slavery based on Christian scripture and proslavery theology.

Enslaved and free Black Christians were the most ardent abolitionists, and they drew on scripture to support antislavery and abolition. While a significant amount of scholarship has debated whether Christian churches were pro- or anti-slavery, some of the most exciting research about the church and slavery has focused on why enslaved people became Christian and how they used the bureaucracy of the church to advocate for their rights and to protect their communities.

Much of this scholarship has emerged from a Latin American context, where archival records are more robust, but there are also important studies focusing on Black churches in the North America, especially the role of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and other African American–led churches. Within this area, scholars debate the meaning of conversion as well as the relationship between African religions and Black Christianity. Recent scholarship has emphasized that Africans and their descendants were not passive recipients of Christianity.

Rather, many enslaved men and women actively sought out baptism and used church institutions not only as a place of worship, but also as a way to protect themselves and their families. Another significant area of research has examined the relationship between the church, slavery, and race. Scholars have demonstrated how European Christians drew on categories of religious difference as they developed new racial categories. They have shown how categories like “Whiteness” and “purity of blood” were transformed within the context of slavery, as enslavers sought to reconcile slaveholding with Christian practice.

General Overviews