#Christian disunity is a scandal

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

John 17:

21. That they all may be one, as thou, Father, in me, and I in thee; that they also may be one in us; that the world may believe that thou hast sent me.

22. And the glory which thou hast given me, I have given to them; that they may be one, as we also are one:

23. I in them, and thou in me; that they may be made perfect in one: and the world may know that thou hast sent me, and hast loved them, as thou hast also loved me.

#catholic#scripture#500 reasons and counting#reformation day#Christian disunity is a scandal#that they may be one

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

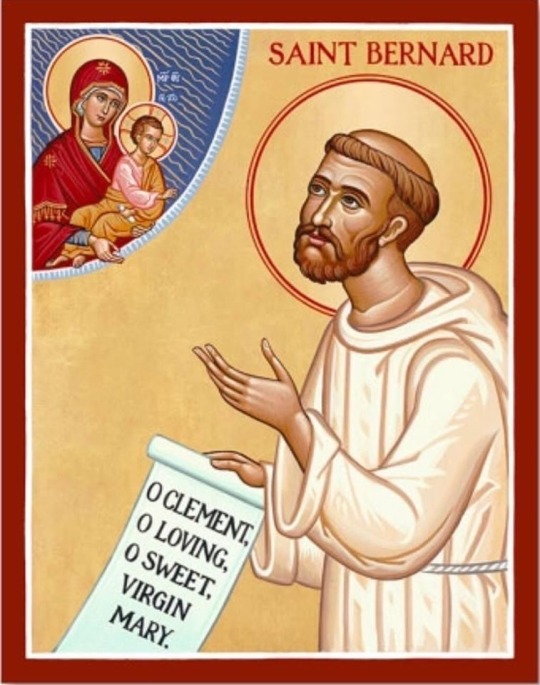

Today the Church remembers St. Bernard of Clairvaux, Monk.

Ora pro nobis.

St. Bernard de Clairvaux, (born 1090 AD, probably Fontaine-les-Dijon, near Dijon, Burgundy [France]—died August 20, 1153 AD, Clairvaux, Champagne; canonized January 18, 1174; feast day August 20), was a Cistercian monk and mystic, the founder and abbot of the abbey of Clairvaux, and one of the most influential churchmen of his time.

Born of Burgundian landowning aristocracy, Bernard grew up in a family of five brothers and one sister. The familial atmosphere engendered in him a deep respect for mercy, justice, and loyal affection for others. Faith and morals were taken seriously, but without priggishness. Both his parents were exceptional models of virtue. It is said that his mother, Aleth, exerted a virtuous influence upon Bernard only second to what Monica had done for Augustine of Hippo in the 5th century. Her death, in 1107, so affected Bernard that he claimed that this is when his “long path to complete conversion” began.

He turned away from his literary education, begun at the school at Châtillon-sur-Seine, and from ecclesiastical advancement, toward a life of renunciation and solitude. Bernard sought the counsel of the abbot of Cîteaux, Stephen Harding, and decided to enter this struggling, small, new community that had been established by Robert of Molesmes in 1098 as an effort to restore Benedictinism to a more primitive and austere pattern of life. Bernard took his time in terminating his domestic affairs and in persuading his brothers and some 25 companions to join him. He entered the Cîteaux community in 1112, and from then until 1115 he cultivated his spiritual and theological studies.

Bernard’s struggles with the flesh during this period may account for his early and rather consistent penchant for physical austerities. He was plagued most of his life by impaired health, which took the form of anemia, migraine, gastritis, hypertension, and an atrophied sense of taste.

Founder And Abbot Of Clairvaux

In 1115 Stephen Harding appointed him to lead a small group of monks to establish a monastery at Clairvaux, on the borders of Burgundy and Champagne. Four brothers, an uncle, two cousins, an architect, and two seasoned monks under the leadership of Bernard endured extreme deprivations for well over a decade before Clairvaux was self-sufficient. Meanwhile, as Bernard’s health worsened, his spirituality deepened. Under pressure from his ecclesiastical superiors and his friends, notably the bishop and scholar William of Champeaux, he retired to a hut near the monastery and to the discipline of a quack physician. It was here that his first writings evolved. They are characterized by repetition of references to the Church Fathers and by the use of analogues, etymologies, alliterations, and biblical symbols, and they are imbued with resonance and poetic genius. It was here, also, that he produced a small but complete treatise on Mariology (study of doctrines and dogmas concerning the Virgin Mary), “Praises of the Virgin Mother.” Bernard was to become a major champion of a moderate cult of the Virgin, though he did not support the notion of Mary’s immaculate conception.

By 1119 the Cistercians had a charter approved by Pope Calixtus II for nine abbeys under the primacy of the abbot of Cîteaux. Bernard struggled and learned to live with the inevitable tension created by his desire to serve others in charity through obedience and his desire to cultivate his inner life by remaining in his monastic enclosure. His more than 300 letters and sermons manifest his quest to combine a mystical life of absorption in God with his friendship for those in misery and his concern for the faithful execution of responsibilities as a guardian of the life of the church.

It was a time when Bernard was experiencing what he apprehended as the divine in a mystical and intuitive manner. He could claim a form of higher knowledge that is the complement and fruition of faith and that reaches completion in prayer and contemplation. He could also commune with nature and say:

Believe me, for I know, you will find something far greater in the woods than in books. Stones and trees will teach you that which you cannot learn from the masters.

After writing a eulogy for the new military order of the Knights Templar he would write about the fundamentals of the Christian’s spiritual life, namely, the contemplation and imitation of Christ, which he expressed in his sermons “The Steps of Humility” and “The Love of God.”

Pillar Of The Church

The mature and most active phase of Bernard’s career occurred between 1130 and 1145. In these years both Clairvaux and Rome, the centre of gravity of medieval Christendom, focussed upon Bernard. Mediator and counsellor for several civil and ecclesiastical councils and for theological debates during seven years of papal disunity, he nevertheless found time to produce an extensive number of sermons on the Song of Solomon. As the confidant of five popes, he considered it his role to assist in healing the church of wounds inflicted by the antipopes (those elected pope contrary to prevailing clerical procedures), to oppose the rationalistic influence of the greatest and most popular dialectician of the age, Peter Abelard, and to cultivate the friendship of the greatest churchmen of the time. He could also rebuke a pope, as he did in his letter to Innocent II:

There is but one opinion among all the faithful shepherds among us, namely, that justice is vanishing in the Church, that the power of the keys is gone, that episcopal authority is altogether turning rotten while not a bishop is able to avenge the wrongs done to God, nor is allowed to punish any misdeeds whatever, not even in his own diocese (parochia). And the cause of this they put down to you and the Roman Court.

Bernard’s confrontations with Abelard ended in inevitable opposition because of their significant differences of temperament and attitudes. In contrast with the tradition of “silent opposition” by those of the school of monastic spirituality, Bernard vigorously denounced dialectical Scholasticism as degrading God’s mysteries, as one technique among others, though tending to exalt itself above the alleged limits of faith. One seeks God by learning to live in a school of charity and not through “scandalous curiosity,” he held. “We search in a worthier manner, we discover with greater facility through prayer than through disputation.” Possession of love is the first condition of the knowledge of God. However, Bernard finally claimed a victory over Abelard, not because of skill or cogency in argument but because of his homiletical denunciation and his favoured position with the bishops and the papacy.

Pope Eugenius III and King Louis VII of France induced Bernard to promote the cause of a Second Crusade (1147–49) to quell the prospect of a great Muslim surge engulfing both Latin and Greek Orthodox Christians. The Crusade ended in failure because of Bernard’s inability to account for the quarrelsome nature of politics, peoples, dynasties, and adventurers. He was an idealist with the ascetic ideals of Cîteaux grafted upon those of his father’s knightly tradition and his mother’s piety, who read into the hearts of the Crusaders—many of whom were bloodthirsty fanatics—his own integrity of motive.

In his remaining years he participated in the condemnation of Gilbert de La Porrée—a scholarly dialectician and bishop of Poitiers who held that Christ’s divine nature was only a human concept. He exhorted Pope Eugenius to stress his role as spiritual leader of the church over his role as leader of a great temporal power, and he was a major figure in church councils. His greatest literary endeavour, “Sermons on the Canticle of Canticles,” was written during this active time. It revealed his teaching, often described as “sweet as honey,” as in his later title doctor mellifluus. It was a love song supreme: “The Father is never fully known if He is not loved perfectly.” Add to this one of Bernard’s favourite prayers, “Whence arises the love of God? From God. And what is the measure of this love? To love without measure,” and one has a key to his doctrine.

St. Bernard was declared a doctor of the church in 1830 and was extolled in 1953 as doctor mellifluus in an encyclical of Pius XII.

O God, by whose grace your servant Bernard, kindled with the flame of your love, became a burning and a shining light in your Church: Grant that we also may be aflame with the spirit of love and discipline, and walk before you as children of light; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

#christianity#jesus#saints#monasticism#god#father troy beecham#troy beecham episcopal#father troy beecham episcopal

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I have a question: do you know how and/or why the Catholic Church got its name? My MIL is curious because she knows why certain churches have the names they have but not the Catholic Church.

Okay, so strictly speaking there is no such thing as the “Catholic Church” and there hasn’t been since the great schism of 1054 CE.

Now wait just a minute, I hear you say. I’m darn sure there is in fact a Catholic Church. And I’m pretty sure I heard something about a Pope in Rome?

Well, yes, you are absolutely right. But, strictly speaking, that is the Roman Catholic Church.

Okay, okay, let me actually explain. So the word “catholic” means “universal" in Greek (by way of Latin). It first came into use in the earliest centuries of Christianity, and was used to distinguish the “true” and “universal” church from various splinter groups understood to be heretical. Many, though not all, of these groups had more exclusionary policies as to who could join the group, and hence were in opposition to the “universal” church, which was, at least in theory, open to all. The Catholic church was also supposed to be distinguished by a unity of prayer, practice, and belief across geographical and cultural distances.

Fast forward to the great East-West schism of 1054, when the western Roman Catholic and the eastern Orthodox church split from one another. (There’s quite a lot that underlies this split and I won’t bog you down with that here.) Since then, both halves of the church have considered Christian unity to be ruptured, and both East and West still refer to the “great scandal” of disunity in the church.

Because the church universal is divided, no church can truly claim to be the Catholic church. The eastern churches call themselves Orthodox (meaning “right teaching”), while the western church calls itself “Roman Catholic,” that is, the universal church of Rome. It’s still considered very important to Roman Catholic religious identity that there is a oneness of teaching, liturgy, and communion with Rome in all Roman Catholic churches, across diverse cultural and geographical spaces. This is also often in implied distinction to the tradition of a lot (though not all) of Protestant churches, particularly those in Europe, where the church is referred to as the “Church of [Country].”

So, technically, when we call ourselves Catholic we really ought to be saying “Roman Catholic.” But that’s kind of a mouthful, so we generally shorten it to just Catholic.

#replies#jedikali#catholicism#christianity#this is of course still over simplified#and i'm not about to get into the various breakaway sects from the roman catholic church#that also call themselves some form of catholic#it gets complicated#as one of my orthodox professors often joked#westerners love their schisms

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

11th September >> “Using shame to motivate the community” ~ Daily Reflection on Today’s Gospel Reading for Roman Catholics on Tuesday of the Twenty-Third Week in Ordinary Time.

Some of the faults listed by St Paul are less serious than others, but all were disturbing the peace of the church in Corinth. The main problem was their disunity, compounded by the complacency they felt even when wronging one another, “You yourself injure and cheat your very own brother and sister.” He singles out the scandal of members taking their problems and disputes to secular law courts. Indignantly he adds, “I say this in an attempt to shame you.”

Paul tends to link the idea of darkness to a list of sins which he found or suspected in Corinth: fornication, idolatry, adultery, sodomy, thievery, miserliness, drunkenness, slander and the rest. Their main sin, in his view, is disunity and their willingness to offend one another, He singles out the scandal of mistrust and deceit in the Corinthian church, so that members feel obliged to take their problems and disputes to secular law courts. Indignantly, he expects more of baptised Christians.

Night can be a time of violence and death, as well as of rebirth and new awareness. At night some people lose their healthy inhibitions and self-control, and it can be dangerous to go anywhere near certain areas just as the bars are closing. But night can also be a time of profound, silent prayer. Jesus went out to the mountain to pray, spending the night in communion with God. Silent prayer of such intense surrender turns into a dynamic time of new life. “Even when you were dead in sin, God gave you new life in company with Christ.” After being restored by the night of prayer, at daybreak he called his disciples and selected twelve of them to be his apostles. Jesus proceeded to share his life by teaching and by healing all who came to him. “Power went out from him which cured all.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Angela Merkel’s final year

New Post has been published on http://khalilhumam.com/angela-merkels-final-year/

Angela Merkel’s final year

By Constanze Stelzenmüller It is mortifying to have to begin a column with a confession about one’s worst-ever prognosis. But in October 2005, I wrote for the Financial Times about the recent German election: “Ms. Merkel’s grand coalition … is merely an interregnum arrangement. With luck, it will last two years.” I may or may not have added, “Ms. Merkel might turn out to be a dead woman walking: a leader beginning the end of her career rather than ending the beginning.” Chancellor Angela Merkel is now entering the last year of her fourth and—she vows—final term in office. She has already been in power for more years than West Germany’s first leader Konrad Adenauer (1949-63). Depending on how long it takes to form a government after the next election, due in fall 2021, she might even overtake Helmut Kohl (1982-98) to become Germany’s longest-serving postwar leader. The 66-year-old’s popularity has soared during the pandemic, making her the country’s best-liked politician by a long shot, and Germans also give her government top marks. As one commentator noted, she “is now on her third American and fourth French presidents, her fifth British and seventh Italian prime ministers.” A recent US poll of 13 countries showed Merkel to be the world’s most trusted leader, well ahead of all of her peers. Depressed American and British commentators, in particular, have taken to calling her the “leader of the free world” (a title the chancellor is said to detest). So, I got that really, really, really wrong. I’ve never met the chancellor, and probably never will, so this is probably the best place to say: sorry, Ms. Merkel.

An Inconclusive Claim to Fame

Still, such an Alpine range of political capital begs questions. Where did it come from? What will she do with it? Adenauer’s claim to greatness was Westbindung—anchoring the young West German republic in the transatlantic alliance. Willy Brandt (1969-74) sought reconciliation with Eastern Europe, falling to his knees in Warsaw. Helmut Kohl gave up the deutschmark for the sake of a European currency and steered the two Germanies to reunification. Each one left office against his will and under a shadow: Adenauer, because he had clung on too long; Brandt, a heavy drinker, because of a spy affair; Kohl’s record is tarnished by a party finance scandal. Yet all three were great chancellors. Meanwhile Angela Merkel’s claim to a place in the annals of fame remains oddly inconclusive. Certainly, the character flaws of some of her predecessors elude her. She only ran for a fourth term after agonizing reflection, and stepped down gracefully as party head after two regional election defeats for her party in 2018; she has firmly excluded running again—or seeking any other public office. She is famously hard-working and in total command of her material. Her sobriety and probity are in no doubt. And yet ambiguity envelops her record. Perhaps it is rooted in the fact that many of the most significant achievements of her tenure have come with a darker underside. The Merkel era saw Germany roar from “sick man of Europe” to the world’s fourth-largest economy, with sharply rising living standards. Her economic policies were notably business-friendly, but failed to do enough when it came to technological and infrastructure modernization. Scandals, from “Dieselgate” to the Wirecard drama, reveal a deeply flawed corporate culture, and a resistance to accountability that makes the German economy highly vulnerable to illicit financial flows. Merkel’s decision not to close Germany’s borders against a huge wave of refugees in September 2015 was an act of genuine humanism. It was also the responsible thing to do; it took pressure off much weaker neighbors. Most of those who stayed have become integrated into society and the workforce. But cities and states struggled to cope at first. It took a multi-billion euro deal with Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to stop the flow of migrants. And it propelled an obscure right wing party, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), to leader of the opposition a mere four years after it was founded.

A True Believer

The chancellor’s move to support the European Recovery Program in May deserves a place in the history books—it probably saved the European Union. But her government’s insistence on austerity for Greece during the eurozone crisis, and her failure to call out fellow Christian Democrat Viktor Orbán for turning Hungary into an illiberal democracy, deepened European divisions. Merkel is a true believer in the transatlantic alliance, yet she struggled to stand up to US President Donald Trump, and failed to keep Germany’s defense commitments. Her reluctance to recognize and counter Russian and Chinese interference in the European space for what it is—efforts to establish dominance and undermine the cohesion of the West—has weakened the EU in a dark time. When the chancellor rises to the occasion, she shows herself to be a shrewd and empathetic leader who can forge common purpose out of disunity —as she has done at many EU and G-7 summits, and during the pandemic. Ruling a fractious Germany with three grand coalition governments (and one with the pro-business Free Democrats) —is in itself an achievement. Yet she will be equally remembered for her hesitancies and an often maddening incrementalism. By pushing her own center-right Christian Democrats to modernize, she marginalized her coalition partners, the center-left Social Democrats, and left a gaping vacuum on the right flank of her own party, promptly filled by the AfD.

Admired but Lonely

Finally, after a political lifetime of expertly eliminating rivals, she is left with no plausible heir. So, the chancellor finds herself, as the longest-serving leader in Europe, in much the same place as her country: admired, but rather lonely. Where does that leave her legacy? Grand gestures are not Merkel’s style; and she may well try to kick political liabilities like Nord Stream 2 or the fight over 5G to her successor. The US elections, however, might give her a fateful choice: to re-build bridges over the Atlantic, or seek refuge in the East. I’d like to think the good bet is on the former. But then again, you may not want to trust my judgment.

0 notes

Text

“What then can we do about the glaring contradiction between the unity and catholicity of the church we say we believe in and its brokenness in practice?

Acknowledging once again that like all the gifts of the Spirit the gift of unity and wholeness is one we cannot give ourselves, what can we do to open ourselves to receive it?

1. If we want the community-creating work of the Spirit within and among the churches, we can give up all attempts to justify, excuse, or explain away the scandal of the church’s disunity and brokenness that contradicts everything we say about one Lord, one Spirit, one faith, one baptism, one God of us all. We can acknowledge the sinfulness of the wrangling within and the divisions between churches and denominations that call themselves the body of Christ.

2. If we want the Spirit’s gift of community, we can examine ourselves before we criticize the faith and life of other denominations and groups within our own denomination. Is it really our steadfast holding to biblical truth that separates us from others—or perhaps only the desire to insist on the superiority of our limited and self-serving interpretation of it? If the church is split into warring churches and factions with churches, is it because of “their” or our own unwillingness to be instructed and corrected by the gospel? When we reject and refuse to have anything to do with people and groups of people who understand Christian faith and life differently from us, is it really because we seek the integrity of the church—or perhaps because what we really want is for people like us to have controlling power (us males or females, heterosexuals or homosexuals, rich or poor people, political and theological liberals or conservatives)? Is the disunity and brokenness of the church due to someone else’s or our own sinfulness?

3. If we want the Spirit’s community-building power among us, we will be open to talk and listen to other denominations and groups within our denomination. What if the Spirit of God is also at work among them? If we are too afraid or too suspicious to have anything to do with them, might we not deprive ourselves of something very important the Spirit is saying to us and doing for us through them? Unless we let them speak for themselves, how can we know whether their version of Christian faith and life is as foolish or corrupt as we think? Have we rejected fellowship with them on the basis of what they really believe and how they really live, or only on the basis of the prejudiced caricatures we have made of them? Do we listen to everything they have to say, or do we hear only what we “knew” beforehand they would say? How can we be open to the reformation of the church if we are not open to listen to, learn from, and let ourselves be corrected by other Christians and churches who read the same Bible in their efforts to be guided by and follow the same Lord we want to follow?

“Dialogue” is not a magic solution to the problem of the church’s lack of unity and catholicity, but the problem can never be solved without dialogue.

4. If we want the Spirit’s gift of community, we will recognize that unity does not mean uniformity. Within Christian community there are “varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit; and there are varieties of services, but the same Lord; and there are varieties of activities, but it is the same God who activates all of them in everyone” (1 Cor. 12:4–6).

All Christians do not have to think or live exactly alike. Are we sure that the different interpretations of Christian truth and practice among other denominations and parties are of community-splitting significance? Even if others seem to be one-sided in one direction or another, might we not need fellowship with them to correct one-sidedness on our part?

True unity does not mean a boring and sterile sameness; it is a unity in which there is exciting and mutually enriching diversity.

... If it is the Spirit’s unity-in-diversity we seek, we will be very careful not to draw these boundaries too rigidly or narrowly, and will always be open to learn that the God of Jesus Christ is more “inclusive” than we might have expected (as the early church had to learn in its dealings with uncircumcised Gentiles).

Of course, all this is easier said than done. But how can we refuse to take the risks and run the dangers of such attitudes and actions if we really want the one holy catholic church we confess?”

-- Shirley Guthrie in Christian Doctrine

#What do you think?#i definitely do not agree with all of what he says but find it a good nuance for discussions on unity and dialogue#dialogue tag#Shirley Guthrie#Christian Doctrine

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The disunity of the Christendom, therefore, must be seen as a scandal in which all the divided churches bear a share of the responsibility. We have all sinned. And yet, perhaps as never before, Christian churches need each other and have been driven by the traumatic historical events of this century to seek the deeper bond of unity that has always been present in the general acceptance of Jesus as Lord. The widespread cooperation and ecumenical tone in biblical studies may prove a harbinger.“

Creed as Symbol, Nicholas Ayo, C.S.C., p. 124

0 notes

Text

An Open Letter to the Priests of the Holy Catholic Church

Great News has been shared on https://apostleshop.com/an-open-letter-to-the-priests-of-the-holy-catholic-church/

An Open Letter to the Priests of the Holy Catholic Church

Copyright 2014 Holy Cross Family Ministries. All rights reserved.

My priests,

It has happened yet again. The men who we, the laity, are supposed to trust with our souls have violated us and brought scandal to the vocation of the priesthood. I am imagining a sobering morning as you read or watched the news. You knelt before God saying your morning prayers, your thoughts distracted by what the rest of the day might hold: The mistrust, the questions, the demand for answers from your parishioners. Did you pray for your fellow priests? Did you pray for the ones who brought the shame and struggle back to the surface? Did you pray for the people who were abused?

I did. And as I prayed, I asked God: “Lord, the Pope has asked us to evangelize. Yet who wants to come to a church where priests lure in and abuse young children? Why do I want to convince my family or friends to join the Catholic Church? Who wants to subject themselves to this mess?”

I began to challenge myself and my faith. I have five young children. Do I want to stay in a church where I can’t trust the people who call themselves “shepherd?” I would put my stamp of approval on my priests and go to the grave claiming their innocence, but I could be wrong. Every Sunday morning or every time I go to confession, I could be staring into the face of a child abuser, and I would never know until it was too late. Is it worth it?

These are my thoughts, not just for our priests but for everyone to read:

Since the death of Christ, His followers have been persecuted. Everyone who bore the cross of Christ on their hearts were sought out, drug out, beat, stoned, crucified, beheaded, burned, fed to lions, and so much more. Yet that did not stop them. Their numbers grew like wildfire because the message of Christ, His body and His blood, filled the bones of all those who stood their ground and defended the Son of God.

Eventually the bloodshed slowed. All was quiet. Money was pouring into the church from people who believed in the message of giving all they had to the poor. After fifteen hundred years, the church was bloated. Finery, excess, indulgences. Satan, the enemy of God, who hates God and all of humanity – changed his tactic from bloodshed to greed. A stain. A reason to leave the church; start something new. Start something that didn’t include the precious body and blood of ‘that Christ’, because a house divided cannot stand.

Five hundred years, 33,000 flavors of Christianity, and one holy, Catholic and apostolic church later … Satan wants more. The Pope has given his flock an evangelization mission and Satan wants to stop anyone from coming to the altar of grace and mercy. They must be thwarted from that transubstantiated Host. So what does he do? He weakens the church from within. Confusion. Mistrust. How can a holy man of God, a man who holds Christ in his hands, molest a small child? The flock will not be able to reconcile this monstrosity before them. They will leave. They will find faith in their hearts and minds elsewhere– as long as they stay away from the Body – because a house divided cannot stand.

From the depths of hell Satan cries for chaos, fear, anger, apathy, and disunity. He will get what he wants. But there is also something else he will get:

Me. And an army of other Catholics who are called and are being called to sainthood.

The sainthood that doesn’t lie in our own perfection but lies in Christ’s. The sainthood which understands that the transubstantiated Host – Jesus’ body and blood – is in us. God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit – the Trinitarian God of the universe made a way for us to consume Him. When we Catholics finally understand the power we have in Him, with Him and through Him, we will be unstoppable. When we match our will with God’s, He can have His way with us on earth: Healing us, changing us, and using us to spread His message of love and forgiveness to wherever He needs it to go.

Saints do not cower and hide out of fear for personal safety and security. They do not grow discouraged at human failing. They do not jump ship when the rumbling giant of Rome is slow to change. Saints press in with a renewed vigor. They use the power of the I AM that is burning inside of them to enact reform. Saints stand out and stand tall in the face of opposition. They forgive human failing. They start small, in their parishes, praying, protecting, and advocating for the innocents – humbly accomplishing the tasks that God has assigned.

And they never, ever stop teaching Truth. Whether the soul is an ordained priest or a baptized one, we are all called to teach the message of Christ. We are all called to proclaim His Passion and Resurrection. We are all called to invite the world to the altar so that they may partake of the Bread of Life. Scandal and the fear of abuse or the fear of being associated with abuse cannot keep us away from what we know to be the Way, the Truth, and the Life.

Scandal cannot keep us away from the Way, the Truth, and the Life. -by @TheJPGeneral Click To Tweet

In closing, the damage done must not be ignored. The Church must account for and admit its failings. It must make reparation. Catholic doctrine teaches repentance and penance and must uphold its own teaching or risk being thrown into the Pharisaical lot that Jesus so often reprimanded.

As an advocate for the Church, by order of being one of its members, I humbly apologize to all who have been hurt by the actions of the leaders of our Church. It is our job as the laity to be on guard against the works of Satan. We have grown lazy in our prayers, lazy in our faith, and lazy in our attitude towards our relationships with others. I am sorry we were not there for you. I am sorry that you now have to suffer for the rest of your life. I am sorry that it has ruined the ability to have healthy relationships with others.

On behalf of many who are frustrated and who care immensely about you and what you have to live with, we promise to do our part in protecting the children of our parishes. As we sacrifice our time, talent, and treasure to protect our children, we will offer these things up for your healing. Let any merit received go towards the reconciliation between your heart and the heart of Christ.

Peace and good will,

Kelly Tallent

Copyright 2018 Kelly Tallent

Source link

0 notes

Text

When East Meets West

A response to Bradley Nassif's suggestions for Protestant and Orthodox communion.

Prospects for church fellowship between the Orthodox Church and churches with roots in the 16th century Reformation have been and continue to be distant at best. This is not a reason to despair. This makes dialogue, official or unofficial, all the more important, not least as a repentant and hopeful protest against divisions which we know are contrary to Christ’s will.

The deep scandal of Christian disunity is disobedience to Christ’s command: “As I have loved you, so you must love one another” (John 13:34). Such love is not “tolerant” indifference to true doctrine and right practice but demands patient, persevering effort toward reconciliation with fellow Christians from whom we are estranged. The horror of our divisions lies less in the divisions themselves than in our long acceptance of them and the ensuing enmity or (worse) indifference of divided Christians toward one another. Persistent conversation about the faith, even with no prospect of immediate “results,” is one small but essential way for divided Christians to practice loving one another in imitation of the Savior without whose persistent love in the face of contradiction we would have no hope.

An Opening and an Invitation

Bradley Nassif’s article “The Reformation Viewed from the East” is a noteworthy example of an Orthodox theologian looking without rancor at a central Reformation teaching, sola fide, and putting the best construction on it. It is an opening and invitation into just the sort of conversation to which we are summoned by Christ’s command. Representatives of Reformation traditions would doubtless have much to say in response. But rather than pursue this particular conversation ...

Continue reading...

from Christianity Today Magazine http://ift.tt/2B7oW3F via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

When East Meets West

A response to Bradley Nassif's suggestions for Protestant and Orthodox communion.

Prospects for church fellowship between the Orthodox Church and churches with roots in the 16th century Reformation have been and continue to be distant at best. This is not a reason to despair. This makes dialogue, official or unofficial, all the more important, not least as a repentant and hopeful protest against divisions which we know are contrary to Christ’s will.

The deep scandal of Christian disunity is disobedience to Christ’s command: “As I have loved you, so you must love one another” (John 13:34). Such love is not “tolerant” indifference to true doctrine and right practice but demands patient, persevering effort toward reconciliation with fellow Christians from whom we are estranged. The horror of our divisions lies less in the divisions themselves than in our long acceptance of them and the ensuing enmity or (worse) indifference of divided Christians toward one another. Persistent conversation about the faith, even with no prospect of immediate “results,” is one small but essential way for divided Christians to practice loving one another in imitation of the Savior without whose persistent love in the face of contradiction we would have no hope.

An Opening and an Invitation

Bradley Nassif’s article “The Reformation Viewed from the East” is a noteworthy example of an Orthodox theologian looking without rancor at a central Reformation teaching, sola fide, and putting the best construction on it. It is an opening and invitation into just the sort of conversation to which we are summoned by Christ’s command. Representatives of Reformation traditions would doubtless have much to say in response. But rather than pursue this particular conversation ...

Continue reading...

from http://feeds.christianitytoday.com/~r/christianitytoday/ctmag/~3/fZy0iz4S5jA/east-meets-west-david-yeago-response-orthodoxy.html

0 notes

Text

Grace v Lordship: Proper v Follower viz Poetry, Spirit, and Kingship

Note: This is in prep for upcoming changes to my longer Doctrinal Statement and may be revised.

– I had a professor in one of my two Hermeneutics classes and the Gospel of John who was in the Grace Theological Society, Dr. John Hart. – I grew up under a Lordship Theology -trained pastor. Dr. Gerhard T. deBock, but experienced a nice contrast with the Church of God with my grandmother during my younger childhood years, which my childhood church didn’t really know much about. – I also visited many other Christian fellowships across the North and Midwest, which I wrote about in my Crossroads series. – My primary understanding of both comes from studying under their avid evangelists and in life and conversation, not merely through literature nor as a third-hand follower. – Tenants of “Grace” Proper (not extra teachings spread by fans & followers of Grace Theology who tend to use it as a license to sin) is mainly theoretical: In theory, sin does not remove salvation, which is by faith, not by perfect obedience to works. They define “repentance” as “changing one’s mind at a core, worldview level”. Their main point is essentially that we can’t lose our salvation. – Tenants of “Lordship” Proper (not the extra teachings spread by the fans & followers who tend to tone it down when it seems too extreme) is mainly behavioral: In practice, ongoing, conscious sin in a Believer’s life with no concern whatsoever is an indication that that Believer might not have become a Christian, but still can. They define “repentance” as both mental and emotional and teach “radical repentance”, missing the point that over-defining emotions makes a kind of volitional repentance (emotional theatrics) and that the decision to believe Jesus usually catches us by surprise to such a point that we have no control over how “radical” our repentance is. Lordship usually teaches that salvation can be lost, but more as a concession, redirecting conversation to the likelihood that a Christian who appears to “lose salvation” probably was not a real Christian to begin with. – Both groups feel that they want to agree at some level. Both question whether they are only debating semantics. Both eventually agree that it is about more than semantics, but lifestyle and quality of happiness in Christ. – The two seem to be offspring of Calvinism and Arminianism, and are post- Millard J. Erickson, which is why I prefer his book, Christian Theology. – Both of them have powerful truths that don’t necessarily need to conflict. – Grace, though it often leads to it among followers, does not want lawlessness and strongly objects to “Grace as a license to sin”. – Lordship, though it often leads to it among followers, does not want legalism and strongly objects to “Works-based salvation”. – The general problem, in my conclusion, is over-analysis. – It is interesting that their primary circuits are in Bible Church communities (likely to believe that Baptism of the Holy Spirit is not a second work, but happens at Christian conversion.) Presence in Pentecostal and Charismatic circles (Baptism of the Holy Spirit is a second work, post Christian conversion, usually through laying on of hands) rarely reflects the original tenants of either Grace of Lordship and behaves more like the extra ideas added by fans and followers. – I believe that these both result from a combination of genuine love for Jesus in a believer who has not received the second work of baptism. It seems like the man who tries to manufacture an android female companion until he falls in love with a real woman. – In their over-analysis, both of them miss the point that humans instinctively use the term “repent” correctly, even with no theological, Biblical, Christian, or any kind of religious background at all. We know what it means. It’s emotional. It is both cooperative and involuntary. It is a “come to Jesus moment” about whatever truth is on the table. It is that moment that hits us where we say, “What have I done!” And, above all, it is beyond any definition except to say that repentance is repentance. Such emotional-poetic forms of explanation usually seem uncomfortable when trying to over-analyze. Still, this mistake of over-analysis is well-intended and not malicious, at least from the the Grace and Lordship Proper theologians themselves. – The basic solution to Grace v Lordship is the paradigm that Jesus is Bridegroom, King, and Judge. The Bible refers to these three paradigms to describe Jesus quite often. He can judge us because he is our friend. That’s what a king involves. He is not a Lord only. He is not a grace-giver only. He is our king, which means both friend and judge, and he has the authority to help and save. – The best-kept secret among both Grace and Lordship is the benefit of works. God’s commands make perfect sense, though not always to us in our situations. God’s law liberates us (Ps 119:32). His command is love and life. By making wise and moral choices, quality of life will be better. Thus, the bigger question is not whether we can or cannot sin and be Christian, but the Christian question is whether we can sin and remain happy. Both Grace and Lordship Proper teachers seem to agree to this, but rarely say so since their main focus seems to be on detailed analysis. Again, by over-analyzing, they miss another point: The Bible is not an analytical-academic work, it is poetic, whether in prose or in content. – The essential problem with both Grace and Lordship is that they are over-analytical rather than poetic. And, most of the problems in the Church do not come from Proper Grace or Lordship teachings, but from followers and fans of each who, not being as heavily trained in developing Biblical and Systematic-Bible Theology just don’t understand what the academic authors are really trying to get at. I, however, understand them perfectly and I love them all in both groups. I just pray they can find that second work of poetry and Spirit so that their good message might finally come across.

Can Christians continue in ongoing sin? (Just look at Sunday Morning.) – Of course they can. To say otherwise would indite everyone who attends Sunday Morning… – Living off of Christian donations, but not in a commune or as guests on the mission field. (We have come to accept a local resident of what the Shepherd of Hermes called ‘Christ mongers’.) – The scandal of disunity during the most segregated and unbiblically territorial hour of the week. – So many theological disagreements that would be solved if we merely applied Matt 18:15ff and James 1:19 to our denominational differences. – Essentially, Christian divisiveness and concern about “retaining local congregation membership” wouldn’t exist if pastors didn’t live off of donations—a practice neither demonstrated nor encouraged in the New Testament. Paul’s teaching of “payment” was not for a leader, but for deacons (Operations Employees). – The sad part is that we care so little about Christian fellowship, except for our small group of friends, that we gladly tolerate the widespread mutual spite in the Church and walls that inhibit more fellowship. We easily say, “It’s not perfect, but it is where we are.” But, with all the stronger friendships we could share in Christ, the current Sunday Morning system is not merely imperfect, it is a travesty that needs to be ended as soon as possible. – Back to the “necessary evil” argument about the problems with the Constantine-initiated clerical and non-profit structures we mandate today, they may be evil but they are anything but necessary. – So much sin is tolerated in the Church. Even with all the vomit spilled on Rob Bell (rather than Don Carson’s benevolent and charitable ‘communicative’ approach to potentially errant doctrine), Christian “professionals” (a Biblical oxymoron, given that Jesus and Paul had a trade) would rather that someone submit to and agree with Rob Bell as a pastor, rather than be a Christian who disagreed with Rob Bell and followed Biblical teaching, but without “submitting” to a paid, State-licensed clergy. It is clear where the “professionalism” culture in the Church has misguided our priorities. If the organic and undocumented Christian life had more priority than State-licensed “church” membership, perhaps there wouldn’t be so much widespread immorality in the Church universal. – The only reason I advocate a delay in the inevitable transition away from Sunday Morning is to avoid even more of the same broken fellowship that is no less than intolerable. I don’t advocate leaving Sunday Morning quickly, but no one, under any circumstances, should advocate staying aboard when the time comes to abandon the sinking ship. – Grace v Lordship and similar controversies, arguably, might not exist were it not for the divisive and misguided priorities of the Constantine-implemented territorial clerical system.

Can Christians live without Sunday Morning?

– Of course they can. They did before Constantine.

– Without the crutch, Christians need to learn to walk on their own.

– They must read the Bible seriously and daily.

– They must take initiative to maintain meaningful Christian fellowship, without a nanny to make sure it happens on autopilot.

– They must take personal responsibility for failures, confess their sins and faults to each other, and keep a close connection with Jesus.

– When the strong Christian life becomes the responsibility of the individual Christian, not the responsibility of paid clergy, then Christians will not struggle so much to know the difference between Grace, Works, Faith, and Jesus Christ as our King.

Grace v Lordship: Proper v Follower viz Poetry, Spirit, and Kingship from Jesse Steele

#answer#cheap grace#faith v works#Grace Theology#legalism#license to sin#Lordship Salvation#solution#summary#synthesis

0 notes

Link

“In pointing out all of these differences and areas of separation, I’m not making an argument here for the Catholic side (although I’ve done that for each of these issues elsewhere on this blog). Rather, I’m just pointing out that the wounds of the Reformation are still festering, and in a way that keeps us from being able to pray together as deeply and unitedly as we should. This is for two reasons.

One, because we need to be reminded. When a well-meaning Evangelical said that Catholics and Protestants were basically in agreement, someone (perhaps Mark Shea or Peter Kreeft? I can no longer remember) responded to the effect of, “Great, let’s pray the Rosary together in front of the Blessed Sacrament before Mass!” The point of the response was, yes we have huge areas of unity and that’s great (truly!), but if we can’t pray together without the Catholic leaving his spiritual traditions at the door, we’re not yet where we need to be. We shouldn’t overlook the great progress in Catholic-Protestant relations in the last century, but we also can’t whitewash the areas still needing work.

Second, because this Christian disunity is a scandal (cf. John 17:20-23) and a crisis that demands serious attention. More specifically, it needs a spiritual response, not just a theological one. For us Catholics, it strikes me as exactly why (well, one reason why) we should be making a morning offering of the sort that Cardinal Burke prescribes. Through Mary, united with the graces of the Sacrifice of the Mass, offer up your sufferings for your Protestant and Orthodox brothers and sisters for the cause of Christian unity.

#morning offering#catholic#joe heschmeyer#one holy catholic apostolic#scandal#500 reasons and counting

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today the Church remembers St. Bernard of Clairvaux, Monk.

Ora pro nobis.

St. Bernard de Clairvaux, (born 1090 AD, probably Fontaine-les-Dijon, near Dijon, Burgundy [France]—died August 20, 1153 AD, Clairvaux, Champagne; canonized January 18, 1174; feast day August 20), was a Cistercian monk and mystic, the founder and abbot of the abbey of Clairvaux, and one of the most influential churchmen of his time.

Born of Burgundian landowning aristocracy, Bernard grew up in a family of five brothers and one sister. The familial atmosphere engendered in him a deep respect for mercy, justice, and loyal affection for others. Faith and morals were taken seriously, but without priggishness. Both his parents were exceptional models of virtue. It is said that his mother, Aleth, exerted a virtuous influence upon Bernard only second to what Monica had done for Augustine of Hippo in the 5th century. Her death, in 1107, so affected Bernard that he claimed that this is when his “long path to complete conversion” began.

He turned away from his literary education, begun at the school at Châtillon-sur-Seine, and from ecclesiastical advancement, toward a life of renunciation and solitude. Bernard sought the counsel of the abbot of Cîteaux, Stephen Harding, and decided to enter this struggling, small, new community that had been established by Robert of Molesmes in 1098 as an effort to restore Benedictinism to a more primitive and austere pattern of life. Bernard took his time in terminating his domestic affairs and in persuading his brothers and some 25 companions to join him. He entered the Cîteaux community in 1112, and from then until 1115 he cultivated his spiritual and theological studies.

Bernard’s struggles with the flesh during this period may account for his early and rather consistent penchant for physical austerities. He was plagued most of his life by impaired health, which took the form of anemia, migraine, gastritis, hypertension, and an atrophied sense of taste.

Founder And Abbot Of Clairvaux

In 1115 Stephen Harding appointed him to lead a small group of monks to establish a monastery at Clairvaux, on the borders of Burgundy and Champagne. Four brothers, an uncle, two cousins, an architect, and two seasoned monks under the leadership of Bernard endured extreme deprivations for well over a decade before Clairvaux was self-sufficient. Meanwhile, as Bernard’s health worsened, his spirituality deepened. Under pressure from his ecclesiastical superiors and his friends, notably the bishop and scholar William of Champeaux, he retired to a hut near the monastery and to the discipline of a quack physician. It was here that his first writings evolved. They are characterized by repetition of references to the Church Fathers and by the use of analogues, etymologies, alliterations, and biblical symbols, and they are imbued with resonance and poetic genius. It was here, also, that he produced a small but complete treatise on Mariology (study of doctrines and dogmas concerning the Virgin Mary), “Praises of the Virgin Mother.” Bernard was to become a major champion of a moderate cult of the Virgin, though he did not support the notion of Mary’s immaculate conception.

By 1119 the Cistercians had a charter approved by Pope Calixtus II for nine abbeys under the primacy of the abbot of Cîteaux. Bernard struggled and learned to live with the inevitable tension created by his desire to serve others in charity through obedience and his desire to cultivate his inner life by remaining in his monastic enclosure. His more than 300 letters and sermons manifest his quest to combine a mystical life of absorption in God with his friendship for those in misery and his concern for the faithful execution of responsibilities as a guardian of the life of the church.

It was a time when Bernard was experiencing what he apprehended as the divine in a mystical and intuitive manner. He could claim a form of higher knowledge that is the complement and fruition of faith and that reaches completion in prayer and contemplation. He could also commune with nature and say:

Believe me, for I know, you will find something far greater in the woods than in books. Stones and trees will teach you that which you cannot learn from the masters.

After writing a eulogy for the new military order of the Knights Templar he would write about the fundamentals of the Christian’s spiritual life, namely, the contemplation and imitation of Christ, which he expressed in his sermons “The Steps of Humility” and “The Love of God.”

Pillar Of The Church

The mature and most active phase of Bernard’s career occurred between 1130 and 1145. In these years both Clairvaux and Rome, the centre of gravity of medieval Christendom, focussed upon Bernard. Mediator and counsellor for several civil and ecclesiastical councils and for theological debates during seven years of papal disunity, he nevertheless found time to produce an extensive number of sermons on the Song of Solomon. As the confidant of five popes, he considered it his role to assist in healing the church of wounds inflicted by the antipopes (those elected pope contrary to prevailing clerical procedures), to oppose the rationalistic influence of the greatest and most popular dialectician of the age, Peter Abelard, and to cultivate the friendship of the greatest churchmen of the time. He could also rebuke a pope, as he did in his letter to Innocent II:

There is but one opinion among all the faithful shepherds among us, namely, that justice is vanishing in the Church, that the power of the keys is gone, that episcopal authority is altogether turning rotten while not a bishop is able to avenge the wrongs done to God, nor is allowed to punish any misdeeds whatever, not even in his own diocese (parochia). And the cause of this they put down to you and the Roman Court.

Bernard’s confrontations with Abelard ended in inevitable opposition because of their significant differences of temperament and attitudes. In contrast with the tradition of “silent opposition” by those of the school of monastic spirituality, Bernard vigorously denounced dialectical Scholasticism as degrading God’s mysteries, as one technique among others, though tending to exalt itself above the alleged limits of faith. One seeks God by learning to live in a school of charity and not through “scandalous curiosity,” he held. “We search in a worthier manner, we discover with greater facility through prayer than through disputation.” Possession of love is the first condition of the knowledge of God. However, Bernard finally claimed a victory over Abelard, not because of skill or cogency in argument but because of his homiletical denunciation and his favoured position with the bishops and the papacy.

Pope Eugenius III and King Louis VII of France induced Bernard to promote the cause of a Second Crusade (1147–49) to quell the prospect of a great Muslim surge engulfing both Latin and Greek Orthodox Christians. The Crusade ended in failure because of Bernard’s inability to account for the quarrelsome nature of politics, peoples, dynasties, and adventurers. He was an idealist with the ascetic ideals of Cîteaux grafted upon those of his father’s knightly tradition and his mother’s piety, who read into the hearts of the Crusaders—many of whom were bloodthirsty fanatics—his own integrity of motive.

In his remaining years he participated in the condemnation of Gilbert de La Porrée—a scholarly dialectician and bishop of Poitiers who held that Christ’s divine nature was only a human concept. He exhorted Pope Eugenius to stress his role as spiritual leader of the church over his role as leader of a great temporal power, and he was a major figure in church councils. His greatest literary endeavour, “Sermons on the Canticle of Canticles,” was written during this active time. It revealed his teaching, often described as “sweet as honey,” as in his later title doctor mellifluus. It was a love song supreme: “The Father is never fully known if He is not loved perfectly.” Add to this one of Bernard’s favourite prayers, “Whence arises the love of God? From God. And what is the measure of this love? To love without measure,” and one has a key to his doctrine.

St. Bernard was declared a doctor of the church in 1830 and was extolled in 1953 as doctor mellifluus in an encyclical of Pius XII.

#father troy beecham#christianity#troy beecham episcopal#jesus#father troy beecham episcopal#saints#god#salvation#peace#monk

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

St. Bernard of Clairvaux

St. Bernard de Clairvaux, (born 1090 AD, probably Fontaine-les-Dijon, near Dijon, Burgundy [France]—died August 20, 1153 AD, Clairvaux, Champagne; canonized January 18, 1174; feast day August 20), was a Cistercian monk and mystic, the founder and abbot of the abbey of Clairvaux, and one of the most influential churchmen of his time.

Ora pro nobis.

Born of Burgundian landowning aristocracy, Bernard grew up in a family of five brothers and one sister. The familial atmosphere engendered in him a deep respect for mercy, justice, and loyal affection for others. Faith and morals were taken seriously, but without priggishness. Both his parents were exceptional models of virtue. It is said that his mother, Aleth, exerted a virtuous influence upon Bernard only second to what Monica had done for Augustine of Hippo in the 5th century. Her death, in 1107, so affected Bernard that he claimed that this is when his “long path to complete conversion” began.

He turned away from his literary education, begun at the school at Châtillon-sur-Seine, and from ecclesiastical advancement, toward a life of renunciation and solitude. Bernard sought the counsel of the abbot of Cîteaux, Stephen Harding, and decided to enter this struggling, small, new community that had been established by Robert of Molesmes in 1098 as an effort to restore Benedictinism to a more primitive and austere pattern of life. Bernard took his time in terminating his domestic affairs and in persuading his brothers and some 25 companions to join him. He entered the Cîteaux community in 1112, and from then until 1115 he cultivated his spiritual and theological studies.

Bernard’s struggles with the flesh during this period may account for his early and rather consistent penchant for physical austerities. He was plagued most of his life by impaired health, which took the form of anemia, migraine, gastritis, hypertension, and an atrophied sense of taste.

Founder And Abbot Of Clairvaux

In 1115 Stephen Harding appointed him to lead a small group of monks to establish a monastery at Clairvaux, on the borders of Burgundy and Champagne. Four brothers, an uncle, two cousins, an architect, and two seasoned monks under the leadership of Bernard endured extreme deprivations for well over a decade before Clairvaux was self-sufficient. Meanwhile, as Bernard’s health worsened, his spirituality deepened. Under pressure from his ecclesiastical superiors and his friends, notably the bishop and scholar William of Champeaux, he retired to a hut near the monastery and to the discipline of a quack physician. It was here that his first writings evolved. They are characterized by repetition of references to the Church Fathers and by the use of analogues, etymologies, alliterations, and biblical symbols, and they are imbued with resonance and poetic genius. It was here, also, that he produced a small but complete treatise on Mariology (study of doctrines and dogmas concerning the Virgin Mary), “Praises of the Virgin Mother.” Bernard was to become a major champion of a moderate cult of the Virgin, though he did not support the notion of Mary’s immaculate conception.

By 1119 the Cistercians had a charter approved by Pope Calixtus II for nine abbeys under the primacy of the abbot of Cîteaux. Bernard struggled and learned to live with the inevitable tension created by his desire to serve others in charity through obedience and his desire to cultivate his inner life by remaining in his monastic enclosure. His more than 300 letters and sermons manifest his quest to combine a mystical life of absorption in God with his friendship for those in misery and his concern for the faithful execution of responsibilities as a guardian of the life of the church.

It was a time when Bernard was experiencing what he apprehended as the divine in a mystical and intuitive manner. He could claim a form of higher knowledge that is the complement and fruition of faith and that reaches completion in prayer and contemplation. He could also commune with nature and say:

Believe me, for I know, you will find something far greater in the woods than in books. Stones and trees will teach you that which you cannot learn from the masters.

After writing a eulogy for the new military order of the Knights Templar he would write about the fundamentals of the Christian’s spiritual life, namely, the contemplation and imitation of Christ, which he expressed in his sermons “The Steps of Humility” and “The Love of God.”

Pillar Of The Church

The mature and most active phase of Bernard’s career occurred between 1130 and 1145. In these years both Clairvaux and Rome, the centre of gravity of medieval Christendom, focussed upon Bernard. Mediator and counsellor for several civil and ecclesiastical councils and for theological debates during seven years of papal disunity, he nevertheless found time to produce an extensive number of sermons on the Song of Solomon. As the confidant of five popes, he considered it his role to assist in healing the church of wounds inflicted by the antipopes (those elected pope contrary to prevailing clerical procedures), to oppose the rationalistic influence of the greatest and most popular dialectician of the age, Peter Abelard, and to cultivate the friendship of the greatest churchmen of the time. He could also rebuke a pope, as he did in his letter to Innocent II:

There is but one opinion among all the faithful shepherds among us, namely, that justice is vanishing in the Church, that the power of the keys is gone, that episcopal authority is altogether turning rotten while not a bishop is able to avenge the wrongs done to God, nor is allowed to punish any misdeeds whatever, not even in his own diocese (parochia). And the cause of this they put down to you and the Roman Court.

Bernard’s confrontations with Abelard ended in inevitable opposition because of their significant differences of temperament and attitudes. In contrast with the tradition of “silent opposition” by those of the school of monastic spirituality, Bernard vigorously denounced dialectical Scholasticism as degrading God’s mysteries, as one technique among others, though tending to exalt itself above the alleged limits of faith. One seeks God by learning to live in a school of charity and not through “scandalous curiosity,” he held. “We search in a worthier manner, we discover with greater facility through prayer than through disputation.” Possession of love is the first condition of the knowledge of God. However, Bernard finally claimed a victory over Abelard, not because of skill or cogency in argument but because of his homiletical denunciation and his favoured position with the bishops and the papacy.

Pope Eugenius III and King Louis VII of France induced Bernard to promote the cause of a Second Crusade (1147–49) to quell the prospect of a great Muslim surge engulfing both Latin and Greek Orthodox Christians. The Crusade ended in failure because of Bernard’s inability to account for the quarrelsome nature of politics, peoples, dynasties, and adventurers. He was an idealist with the ascetic ideals of Cîteaux grafted upon those of his father’s knightly tradition and his mother’s piety, who read into the hearts of the Crusaders—many of whom were bloodthirsty fanatics—his own integrity of motive.

In his remaining years he participated in the condemnation of Gilbert de La Porrée—a scholarly dialectician and bishop of Poitiers who held that Christ’s divine nature was only a human concept. He exhorted Pope Eugenius to stress his role as spiritual leader of the church over his role as leader of a great temporal power, and he was a major figure in church councils. His greatest literary endeavour, “Sermons on the Canticle of Canticles,” was written during this active time. It revealed his teaching, often described as “sweet as honey,” as in his later title doctor mellifluus. It was a love song supreme: “The Father is never fully known if He is not loved perfectly.” Add to this one of Bernard’s favourite prayers, “Whence arises the love of God? From God. And what is the measure of this love? To love without measure,” and one has a key to his doctrine.

St. Bernard was declared a doctor of the church in 1830 and was extolled in 1953 as doctor mellifluus in an encyclical of Pius XII.

#father troy beecham#christianity#troy beecham episcopal#father troy beecham episcopal#saints#jesus#god#salvation#blessed virgin mary

0 notes