#Chief Lincoln Red Crow

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

RM Guera: Scalped

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

(8/29/22)

Turned the Five Nights at Freddy's UCN board into It Lives-themed, with characters/animals/creatures from ILITW, ILB, and ILW! (I added my personal MCs on the board.)

Here are all of the characters included:

Devon (ILITW MC), Andy, Ava, Noah, Jane, Lucas, Dan, Lily, Connor, Britney, Jocelyn, Mr. Red (Redfield), Cattywumpus (Kitten), Russel (Crow), Hilda (Border Collie), Moss Creature, Vine Creature, Thumper (jackalope), Bear Monster, Elk Monster, Ben, Kyle, Chief Kelly, Josephine (Lake Ghost), Elliot, Parker, Harper (ILB MC), Tom, Imogen, Danni, Astrid, Vincent, Richard, Arthur, Robbie, Chance, Craig, Garrett, Ned, Mr. Cooper, Cody, Mayor Green, Principal Flores, Cid, Lincoln, Rowan (ILW MC), Amalia, Abel, Annie, and Jessica.

#it lives in my head rent free#it lives#it lives anthology#it lives in the woods#choices game#pixelberry#choices ilitw#ilitw#it lives series#it lives beneath#it lives within#fnaf ultimate custom night#fnaf ucn#haha funnies#choices stories you play#choices ilb#ilw

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Orleans playlist

Hungry for some po boys? Feeling the Mardi Gras vibes for this weekend? This is the ultimate NOLA playlist, right here. Play the songs here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL-iHPcxymC182dTlE-Gii6ZOO5ZrN1Z1T

Louisiana and New Orleans, all in the one awesome playlist. If there are songs I left out, let me know and I can add those. Or come meet me at Le Bon Temps Roulé and we’ll listen to this NOLA playlist together with drinks.

LOUISIANA & NEW ORLEANS

001 Bob James - Take Me To The Mardi Gras 002 Earl King - Ain’t no city like New Orleans 003 John Lee Hooker - goin’ to Louisiana 004 Crowbar - Wrath Of Time By Judgment 005 True Detective - Theme (The Handsome Family - Far From Any Road) 006 EyeHateGod - New Orleans Is The New Vietnam 007 The The Meters - Chicken Strut 008 Paul McCartney - Live And Let Die (from Live And Let Die) 009 The Rolling Stones - Brown Sugar 010 Lucinda Williams - Crescent City 011 King Hobo - New Or-Sa-Leans 012 Concrete Blonde - Bloodletting 013 Down - Underneath Everything 014 True Blood Theme Song (Jace Everett - Bad Things) 015 Corrosion of Conformity - Broken Man 016 The New Orleans Jazz Vipers - I Hope Your Comin' Back To New Orleans 017 Willy DeVille - Jump City 018 Left Side - Gold In New Orleans 017 Necrophagia - Reborn through Black Mass 018 Johnny Horton - The Battle Of New Orleans 019 Dr John - Litanie des Saints 020 Foo Fighters - In the Clear 021 Redbone - The Witch Queen Of New Orleans 022 Jucifer - Lautrichienne 023 Danzig - It's a long way back from hell 024 Harry Connick, Jr. - Oh, My Nola 025 The Gaturs - Gator Bait 026 Jon Bon Jovi - Queen Of New Orleans 027 Cyril Neville - Gossip 028 Carlos Santana - Black Magic Woman 029 Gentleman June Gardner - It's Gonna Rain 030 Eddy G. Giles - Soul Feeling (Part 1) 031 Tool - Swamp Song 032 Beasts of Bourbon - Psycho 033 Seratones - Gotta Get To Know Ya 034 Chuck Berry - You Never Can Tell 035 Grateful Dead - Mississippi Half-Step Uptown Toodleoo 036 Pale Misery - Hope is a Mistake 037 Exhorder - Homicide 038 King James & the Special Men - Special Man Boogie 039 Chuck Carbo - Can I Be Your Squeeze 040 Amebix - Axeman 041 Tomahawk - Captain Midnight 042 Waylon Jennings - Jambalaya 043 Heavy Lids - Deviate 044 Red Hot Chili Peppers - Apache Rose Peacock 045 Necrophagia - Rue Morgue Disciple 046 Johnny Cash - Big River 047 Albert King - Laundromat Blues 048 Meklit Feat Preservation Hall Horns - You Are My Luck 049 Le Winston Band - En haut de la montagne 050 Dr. john - I Thought I Heard New Orleans Say 051 Down - New Orleans is a dying whore 052 Samhain - To Walk The Night 053 Creedence Clearwater Revival - Green River 054 Southern Culture on the Skids - Voodoo Cadillac 055 Bonnie, Sheila - You Keep Me Hanging On 056 Warren Lee - Funky Bell 057 Elf - Annie New Orleans 058 Cannonball Adderley - New Orleans Strut 059 Doug Kershaw - Louisiana Man - New Orleans Version 060 Willy deVille - Voodoo Charm 061 The Animals - The House of the Rising Sun 062 Porgy Jones - The Dapp 063 Lost Bayou Ramblers - Sabine Turnaround 064 IDRIS MUHAMMAD - New Orleans 065 John Lee Hooker - Boogie Chillen No. 2 066 Hank 3 - Hillbilly Joker 067 Nine Inch Nails - Heresy 068 Talking Heads - Swamp 069 Irma Thomas - I'd Rather Go Blind 070 Mississippi Fred McDowell - I'm Going Down the River 071 Dee Dee Bridgewater - Big Chief 072 Dr. John - Creole Moon 073 Agents of Oblivion - Slave Riot 074 Steve Vai - Voodoo Acid 075 Saviours - Slave To The Hex 076 Kris Kristofferson - Casey's Last Ride 077 JJ Cale - Louisiana Women 078 Cher - Dark Lady of New Orleans 079 LE ROUX - Take A Ride On A Riverboat 080 The Melvins - A History Of Bad Men 081 Floodgate - Through My Days Into My Nights 082 Opprobium - voices from the grave 083 Quintron & Miss Pussycat - Swamp Buggy Badass 084 Child Bite - ancestral ooze 085 Sammi Smith - The City Of New Orleans 086 The Explosions - Garden Of Four Trees 087 Bobby Boyd - straight ahead 088 Bobby Charles - Street People 089 Wall of Voodoo - Far Side of Crazy 090 Rhiannon Giddens - Freedom Highway (feat. Bhi Bhiman) 091 Elton John - Honky Cat 092 Serge Gainsbourg - Bonnie and Clyde 093 Fats Domino - I'm Walking To New Orleans 094 Cruel Sea - Orleans Stomp 095 Down - On March The Saints 096 Danzig - Ju Ju Bone 097 The Neville Brothers ~ Voodoo 098 Megadeth - The Conjuring 099 Miles Davis - Miles runs the voodoo down 100 Elvis Presley - King Creole 101 Led Zeppelin - Royal Orleans 102 The Lime Spiders - Slave Girl 103 BIG BILL BROONZY -'Mississippi River Blues' 104 Kreeps - Bad Voodoo 105 Dirty Dozen Brass Band - Caravan 106 Kirk Windstein - Dream In Motion 107 Eletric Prunes - Kyrie Eleison - Mardi Gras 108 Merle Haggard - The Legend Of Bonnie And Clyde 109 Corrosion of Conformity - River of Stone 110 THE ADVENTURES OF HUCK FINN (MAIN TITLE) 111 Zigaboo Modeliste - Guns 112 ReBirth Brass Band - Let's Go Get 'Em 113 Inell Young - What Do You See In Her? 114 Jimi Hendrix - If 6 as 9 (Studio Version) Easy Rider Soundtrack 115 Deep Purple - Speed King 116 Exhorder - The Law 117 Crowbar - The Cemetery Angels 118 A Streetcar Named Desire OST - Main Title 119 WOORMS - Take His Fucking Leg 120 steely dan - pearl of the quarter 121 Tabby Thomas - Hoodoo Party 122 Black Label Society - Parade of the Dead 123 Dwight James & The Royals - Need Your Loving 124 Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter (2012) The Rampant Hunter (Soundtrack OST) 125 PanterA - The Great Southern Trendkill 126 Ween - WHO DAT? 127 Earl King - Street Parade 128 Ernie K-Doe - Here Come The Girls 129 Dejan's Olympia Brass Band ~ Mardi Gras In New Orleans 130 Body Count - KKK Bitch 131 Goatwhore - Apocalyptic Havoc 132 C.C. Adcock - Y'all d Think She Be Good To Me (from True Blood S01E01) 133 The Meters - Fire On The Bayou 134 Dr. John - I Walk On Guilded Splinters 135 Balfa Brothers - J'ai Passe Devant ta Porte 136 Ween - Voodoo Lady 137 King Diamond - 'LOA' House 138 Creedence Clearwater Revival - Born On The Bayou 139 Dax Riggs - See You All In Hell Or New Orleans 140 Professor Longhair - Go to the Mardi Gras 141 Dixie Witch - Shoot The Moon 142 Ramones - The KKK Took My Baby Away 143 Fats Waller - There's Going To Be The Devil To Pay 144 Mississippi Fred McDowell - When the Train Comes Along with Sidney Carter & Rose Hemphill 145 Treme Song (Main Title Version) 146 Tony Joe White - Even Trolls Love Rock and Roll 147 Nine Inch Nails - Sin 148 Exodus - Cajun Hell 149 NEIL DIAMOND - New Orleans 150 James Brown - Call Me Super Bad 151 Jimi Hendrix - Voodoo Child ( Slight Return ) 152 Allen Toussaint - Chokin Kind 153 Dash Rip Rock - Meet Me at the River 154 Hawg Jaw- 4 Lo 155 Hot 8 Brass Band - Keepin It Funky 156 Hank Williams III - Rebel Within 157 Dejan's Original Olympia Brass Band - Shake It And Break It 158 Jelly Roll Morton - Finger Buster 159 The Royal Pendletons - (Im a) Sore Loser 160 Little Bob & The Lollipops - Nobody But You 161 Gregg Allman - Floating Bridge (True Detective Soundtrack) 162 Michael Doucel with Beausoleil - Valse de Grand Meche 163 Dolly Parton - My Blue Ridge Mountain Boy 164 Othar Turner & the Afrossippi Allstars – Shimmy She Wobble 165 Jucifer - Fleur De Lis 166 Soilent Green - Leaves Of Three 167 Ides Of Gemini - Queen of New Orleans 168 Betty Harris - Trouble with My Lover 169 Lead Belly - Pick A Bale Of Cotton 170 Candyman Opening Theme 171 Goatwhore - When Steel and Bone Meet 172 Acid Bath - Bleed Me An Ocean 173 Pere Ubu - Louisiana Train Wreck 174 Walter -Wolfman- Washington - You Can Stay But the Noise Must Go 175 Alice in Chains - Hate To Feel 176 Body Count - Voodoo 177 Live and Let Die - Jazz Funeral 178 Smoky Babe - Cotton Field Blues 179 Professor Longhair - Big Chief Part 2 180 Lewis Boogie - Walk the Line 181 James Black - Theres a Storm in the Gulf 182 The Balfa Brothers - Parlez Nous A Boire 183 The Jambalaya Cajun Band - Bayou Teche Two Step 184 The Deacons - Fagged Out 185 Thou - The Changeling Prince 186 Black Sabbath - Voodoo 187 King Diamond - Louisiana Darkness 188 Doyle - Cemeterysexxx 189 KINGDOM OF SORROW - Grieve a Lifetime 190 Hank Williams III - Louisiana Stripes 191 FORMING THE VOID - On We Sail 192 BUCK BILOXI AND THE FUCKS - fuck you 193 Down in New Orleans - The Princess and the Frog Soundtrack 194 Trombone Shorty & James Andrews - oh Poo Pah Doo 195 Whitesnake - Ain't No Love In The Heart Of The City 196 The Dirty Dozen Brass band - Voodoo 197 Joe Simon - The Chokin' Kind 198 Down - Ghosts along the Mississippi 199 AEROSMITH - Voodoo Medicine Man 200 Nine Inch Nails - The Perfect Drug 201 The Byrds - [Sanctuary III] Ballad Of Easy Rider 202 The Iguauas - Boom Boom Boom 203 PJ Harvey - Down By The Water 204 Louis Armstrong - Do You Know What It Means To Miss New Orleans 205 Dr John - Right Place Wrong Time 206 ESTHER ROSE - handyman 207 Lightnin Slim - It's Mighty Crazy 208 Slim Harpo - Blues Hangover 209 Irma Thomas - Ruler Of My Heart 210 WEATHER WARLOCK - Fukk the Plan-0 211 Superjoint Ritual - The Alcoholik (Use Once And Destroy) 212 Stressball - dust 213 Trampoline Team - Kill You On The Streetcar 214 Xander Harris - Where’s your Villain? 215 Dukes of Dixieland - When The Saints Go Marching In 216 Kid Congo & The Pink Monkey Birds - Su Su 217 Danzig - I'm the one 218 EyeHatteGod - Pigs 219 Hank Williams Jr - Amos Moses 220 The Cramps - Alligator Stomp 221 Crowbar - The Serpent Only Lies 222 Shrüm - drip 223 Thou - The Only Law 224 DR. JOHN - Babylon 225 Garth Brooks - Callin' Baton Rouge 226 Wild Magnolias - All On A Mardi Gras Day 227 NCIS New Orleans TV Show theme 228 Skull Duggery - Big Easy 229 Harry Connick Jr. - City beaneath the sea 230 Elvis Presley - Dixieland Rock 231 Tom Waits - I Wish I Was In New Orleans (In The Ninth Ward) 232 Neil Young - Everybody's Rockin 233 Philip H. Anselmo & The Illegals - Delinquent 234 CORROSION OF CONFORMITY - Wolf Named Crow 235 Widespread Panic - Fishwater 236 Lillian Boutté - Why Don't You Go Down to New Orleans 237 Bryan Ferry - Limbo 238 Scream - Mardi Gras 239 EyeHateGod - Shoplift 240 Better Than Ezra - good 241 Duke Ellington - Perdido (1960 Version) 242 Bob Dylan - Rambling, Gambling Willie 243 Big Bad Voodoo Daddy - sAve my soul 244 Le Roux - So Fired Up 245 Concrete Blonde - The Vampire song 246 Boozoo Chavis - Zydeco Mardi Gras 247 Idris Muhammad - Piece of mind 248 Les Hooper - Back in Blue Orleans 249 Doug Kershaw - Cajun stripper 250 DOWN - Witchtripper 251 Soilent Green - So hatred 252 Professional Longhair - Big chief 253 Willie Nelson - City Of New Orleans 254 Tom Waits - Whistlin' Past The Graveyard 255 Brian Fallon - sleepwalkers 256 Patsy - Count It On Down 257 Into the Moat - The Siege Of Orleans 258 Bruce Cockburn - Down To The Delta 259 Jello Biafra · the Raunch and Soul All-Stars - Fannie Mae 260 Exhorder - Asunder 261 Cane Hill - Too Far Gone 262 The Slackers - peculiar 263 Crowbar - A Breed Apart 264 COC - Wiseblood 265 Necrophagia - Embalmed Yet I Breathe 266 EYEHATEGOD - Fake What's Yours 333 Alan Vega - Bye Bye Bayou 666 DOWN - Stone the crow

I don’t beads by the way! Hit play here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL-iHPcxymC182dTlE-Gii6ZOO5ZrN1Z1T

#new orleans#New Orleans playlist#NOLA#NOLA playlist#Louisiana#corrosion of conformity#Alan Vega#necrophagia#New Orleans songs#mardi gras#Mardi Gras songs#crowbar#eyehategod

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your Hero is Not Untouchable Pt 2

Your Hero is Not Untouchable

A Monuments Study: Dakota War of 1862 Memorials, Monuments and Markers

by Rye Purvis 7/3/2020

(T.C. Cannon, Kiowa, painting “Andrew Myrick - Let Em Eat Grass” 1970)

On December 26th, 1862 38 Dakota prisoners of war were executed in Mankato, Minnesota. This was to mark an ending (though not an end to the suffering of the Dakota peoples) to the Dakota War of 1862, a war that began just months earlier in the Fall of ’62. The 38 men were ordered to be executed under the order of Abraham Lincoln, after Lincoln’s examined 303 war trials conducted from September to November of ’62 in Minnesota:

“The trials of the Dakota prisoners were deficient in many ways, even by military standards; and the officers who oversaw them did not conduct them according to military law. The hundreds of trials commenced on 28 September 1862 and were completed on 3 November; some lasted less than 5 minutes. No one explained the proceedings to the defendants, nor were the Sioux represented by defense attorneys. "The Dakota were tried, not in a state or federal criminal court, but before a military commission. They were convicted, not for the crime of murder, but for killings committed in warfare. The official review was conducted, not by an appellate court, but by the President of the United States. Many wars took place between Americans and members of the Indian nations, but in no others did the United States apply criminal sanctions to punish those defeated in war." The trials were also conducted in an atmosphere of extreme racist hostility towards the defendants expressed by the citizenry, the elected officials of the state of Minnesota and by the men conducting the trials themselves. "By November 3, the last day of the trials, the Commission had tried 392 Dakota, with as many as 42 tried in a single day." Not surprisingly, given the socially explosive conditions under which the trials took place, by the 10th of November the verdicts were in, and it was announced to the nation and the world that 303 Sioux prisoners had been convicted of murder and rape by the military commission and sentenced to death.” 1

Lincoln reviewed all transcripts from the rushed trials and made his decision on the final execution in under a month. The public execution remains the largest mass execution in American history. Today a public park remains at the site of the execution, named “Reconciliation Park” and given the theme “Forgive Everyone Everything.” 2 Merriam-Webster’s lists its dictionary definition of reconciliation as “the act of causing two people or groups to become friendly again after an argument or disagreement.”

It Starts with Treaties

To provide context to the Dakota War of 1862 is to acknowledge a trail of once again broken treaties and a US hunger for land acquisition. Before colonial interactions, the Great Sioux Nation covered present-day northern Minnesota and Wisconsin. The ancestors of the Sioux “arrived in the Northwoods of central Minnesota and northwestern Wisconsin from the Central Mississippi River shortly before 800 AD.” 3 Under the Great Sioux Nation are three subdivision groups: The Lakota (Northern Lakota, Central Lakota and Southern Lakota), Western Dakota (Yankton, Yanktonai) and the Eastern Dakota (Santee, Sisseton). It wasn’t until the early 1800’s that the Dakota, of the Sioux Nation, signed a treaty with the US in order to establish US Military posts in Minnesota and open trading for the Dakota. Soon after, the 1825 Treaty of Prarie du Chien and the 1830 Fourth Treaty of Prarie du Chien were put into place to cede more land to the American government. Another 1858 Treaty established the Yankton Sioux Reservation for the Yankton Western Dakota peoples, a treaty that ultimately moved the band from “eleven and a half million acres” to a “475,000 acre reservation.”11 The US created the Territory of Minnesota in 1849, thus placing even more pressure on the Sioux to concede land. More treaties followed with the 1851 Treaty of Mendota and the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux. In both deals, 21 million acres were ceded to the US by the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands of the Dakota in exchange for $1,665,000. “However, the American government kept more than 80% of the funds with only the interest (5% for 50 years) being paid to the Dakota” 4

The US’s aim ultimately was to force the Sioux out of Minnesota. Minnesota, established as a state on May 11, 1858 had two temporary reservations set up along the Minnesota River, one for the Upper Sioux Agency and one for the Lower Sioux Agency. Relocation and displacement from land once used for hunting created even more tension with delayed treaty payments causing economic suffering and starvation. Treaties promised payments to the Sioux, payments that were used for foods but at that point but were often late due to the US’s focus on the Civil War. Trader store operators many times charged credit to the Upper and Lower Sioux Agency’s, collecting the annuity allotments directly from the government in return.

Let them eat grass

Having owned stores in both the Upper and Lower Sioux Agency at the time, trader Andrew J Myrick eventually refused to sell food on credit to the Dakota during the summer of 1862. That summer saw additional hardship with failed crops in the previous year on top of late federal payments. In response to his refusal to allot food, Myrick was quoted as “allegedly” saying “Let them eat grass” a quote that is oftentimes disputed. Around the same time as this disputed quote, on August 17, 1862 a few Santee men of the Whapeton band killed a white farmer and part of his family, thus starting the beginning of the Dakota War of 1862.

This is where we in the 21st century have to take a pause. Most of the written accounts of the start of the war or the “murderous violence” of the “Murdering Indians” 5 (a quote from Peter G Beidler’s “Murdering Indians”) were accounts from the side of the colonizers. When researching the Dakota War of 1862, perspectives from the Dakota are not common. At some point the basis for war warrants a question of American mythology. In researching about this white farmer debacle, the killing is in one instance described as coming from “an argument between two young Santee men over the courage to steal eggs from a white farmer became a dare to kill.”6 In another account, the story follows the same narrative about the farmer’s eggs: “Upon seeing some chicken eggs in a nest at the farm of a white settler, there was a disagreement whether or not to take the eggs. When one refused, his companion dared him to prove that he was not afraid of the white man's reaction.”7 I bring up the eggs incident not to stress on this sliver of historical mythology but to emphasize the instability of perspective in historical accounts. Anti-Indian perspectives and a notion of eradication of the “Indian” has been profound in the beginning in the colonization of the US. For a war to rest on the stolen eggs of a farmer, and the killing of 5 individuals doesn’t take into account the broken down persons that were driven to get to the point of having to steal eggs nor what exactly occurred between the farmer and the men.

After the incident, however it occurred, Mdewakanton Dakota leader Little Crow led a group against the American settlements waging war as a means to remove the white settlers. Little Crow as he is known in European mistranslations, name was actually Thaóyate Dúta meaning “His Red Nation”. He was instrumental in leading discussions in the treaties, providing a voice for his people, and leading Dakota in the Battle of Birch Coulee. In a letter to Henry Sibley, the first Governor of the US State of Minnesota, on September 7, 1862, Thaóyate described the context for the uprising:

“Dear Sir – For what reason we have commenced this war I will tell you. it is on account of Maj. Galbrait [sic] we made a treaty with the Government a big for what little we do get and then cant get it till our children was dieing with hunger – it is with the traders that commence Mr A[ndrew] J Myrick told the Indians that they would eat grass or their own dung. Then Mr [William] Forbes told the lower Sioux that [they] were not men [,] then [Louis] Robert he was working with his friends how to defraud us of our money, if the young braves have push the white men I have done this myself." 8

Famine, broken treaties, late payments from the government were but a few of the motivating factors for driving change. The killing of the five white settlers by the 5 Santee men prompted a motion of action led by then natural leader Thaóyate.

When the war neared an end, Thaóyate and other Dakota warriors escaped. It wasn’t until July 3 of 1863 that Thaóyate was shot by 2 settlers and mortally wounded. Upon his death, Thaóyate’s body was mutilated and his remains were withheld from both family and his tribe until 1971 when the Minnesota Historical Society returned his remains to Thaóyate’s grandson. A historical marker remains where Thaóyate’s life was taken:

“[The] marker, erected in 1929 at the spot where Chief Little Crow (who escaped the hanging) was shot, glorifies the chief’s killer: “Chief Little Crow, leader of the Sioux Indian outbreak in 1862, was shot and killed about 330 feet from this point by Nathan Lamson and his son Chauncey July 3, 1863.” The marker does not mention that Little Crow’s body was mutilated, that his scalp was donated to the Minnesota Historical Society and put on display at the State Capitol. He would not be buried until 1971.” 9

Marker of where Little Crow was shot (photo by Sheila Regan)

I just want to acknowledge, that there is a lot of information to unpack that occurred during the Dakota War of 1862, and I don’t want to pretend that this article can sum up every occurrence, battle or person involved. Author and non-Native Gary Clayton Anderson wrote “Through Dakota Eyes” in 1988, and though not perfect, it provides eyewitness accounts from various Dakota peoples perspectives that is worth noting. The Minnesota Historical Society, though known for its problematic history holding on to Thaóyate’s body, also provides more information on its website regarding oral traditions, resources, publications and more in regards to the Dakota War of 1862. I encourage those interested in diving deeper into information to seek out more while simultaneously questioning the source of the information.

Stolen Bodies

Before Thaóyate’s death, the 38 Dakota men were hung at Mankato under Lincoln’s orders. An additional 2 men by the name of Shakpe and Wakanozanzan who had been captured were also executed on November 11th, 1865 under the order of Andrew Johnson. But this mass execution was not the end of the US’s threat to eradicate the Sioux. After the mass execution, “277 male members of the Sioux tribe, 16 women and two children and one member of the Ho-Chunk tribe”1 were sent to a prison camp at Camp McClellan from April 25, 1863 to April 10, 1866. The prisoners who did not survive Camp McClellan were buried in unmarked graves, later dug up and their skulls used by scientists at the Putnam Museum in the late 1870’s. The 23 skulls were given to the Dakota tribe and not until 2005 was a proper memorial ceremony held for the Dakota prisoners.

In addition, 1600 Dakota women, children and old men were forced into internment camps at Pike Island. Wita Tanka, the Dakota name for Pike Island, is now part of Fort Snelling State Park.

“During this time, more than 1600 Dakota women, children and old men were held in an internment camp on Pike Island, near Fort Snelling, Minnesota. Living conditions and sanitation were poor, and infectious disease struck the camp, killing more than three hundred.[37] In April 1863, the U.S. Congress abolished the reservation, declared all previous treaties with the Dakota null and void, and undertook proceedings to expel the Dakota people entirely from Minnesota. To this end, a bounty of $25 per scalp was placed on any Dakota found free within the boundaries of the state.[38] The only exception to this legislation applied to 208 Mdewakanton, who had remained neutral or assisted white settlers in the conflict."1

Where does this leave us?

The year was 1990 and a 36-year old Cheyenne and Arapaho artist by the name of Hock E Aye VI Edgar Heap of Birds had just finished an installation along the Mississippi River in Downtown Minneapolis titled “Building Minnesota.” The installation featured 40 white metal signs containing the names of the 38 men executed under the order of Abraham Lincoln, and the 2 men executed under the order of Andrew Johnson. Heap of Birds explained, “‘Not everyone loved the piece. Heap of Birds says that he received criticism because of the negative portrayal of Abraham Lincoln. ‘They thought it was a betrayal,’”9 Beyond that, the installation came to be known as a space for healing, mourning, for acknowledgement of the lost men, and a place for community to gather.

(One of the 38+2 Signs by Edgar Heap of Birds, photo from Met Museum)

Two monuments were placed up in 1987 and in 2012 at Reconciliation Park in Monkato, MN. The ‘87 monument named “Winter Warrior” features a Dakota warrior figure made by a local artist and the 2012 monument features a large scroll with poems, prayers, and the list of all the men killed on that dark day of 1862.

Beyond that, Minnesota boasts a plethora of statues, monuments and memorials under the umbrella of the Dakota War of 1862. Fort Ridgely State Park located near Fairfax MN hosts a number of monuments, Wood Lake State Monument, Camp Release State Monument, Defenders State Monument are a few of the myriad of locations dedicated to the Americans who fought, lost their lives as well as civilian causality acknowledgement.

Located in Morton, MN, the Birch Coulee monument was erected in 1894. Close to this monument a granite obelisk was erected five years later titled the “Loyal Indian Monument,” to honor the 6 Dakota “who saved the lives of whites during the U.S. Dakota War.” This monument stood out to me, not so much for its bland appearance, but the unusual circumstance to highlight six “loyal” Native lives amongst the many lost who were seen as disloyal.

Seth Eastman, a descendant of Little Thunder (one of the 38 men executed in Mankato) shared how “one public school at the border of Minnesota, where a man dressed as Abraham Lincoln talked to the students and answered their questions [and one] of my nephews asked the question, ‘Why did you hang the 38?’ This man went on to tell him, ‘Oh, I only hung the bad Indians. The ones that killed and raped.’ Telling kids this, that we’re bad, it’s the same as how we’ve been portrayed in the media. That struck my core.””

He continued:

“Minnesota has its own memorials for the Dakota War, but some of the older ones especially are quite problematic. These markers paint the settlers who fought the Dakota as brave victims who defended themselves, without discussion of the broken treaties and ill treatment the Dakota endured which prompted the war; neither is there any mention of the mass execution, internment, and forced removal that followed.”9

Director and Founder of Smooth Feather productions Silas Hagerty released the documentary Dakota 38 in 2012. The documentary highlights a yearly journey where riders from across the world meet in Lower Brule, South Dakota to take a 330-mile journey to Mankato as part of a commemoration and ceremony of remembrance for the 38 lost in 1862. The film also delves into bits of history on the attempts the US took to remove the Dakota peoples from Minnesota. Jim Miller, a direct descendant of Little Horse (one of the 38 men) started the annual ride in 2005 as “a way to promote reconciliation between American Indians and non-Native people. Other goals of the Memorial Ride include: provide healing from historical trauma; remember and honor the 38 + 2 who were hanged; bring awareness of Dakota history and to promote youth rides and healing.”10

(Dakota Riders Ceremonial ride to Mankota, Photo by Sarah Penman)

The memorials and monuments are in abundance in regards to the Dakota War. But who’s perspective is acknowledged? Through work such as Edgar Heap of Birds in his 1990′s installation, to the 2012 larger public scroll monument in Mankato’s “Reconciliation Park” there have been steps taken by both Native and non-natives to explore what this reconciliation looks like.

Of the two Dakota men captured and ordered to be executed under then US president Andrew Johnson on November 11, 1865, Wakanozanzan of the Mdeqakanton Dakota Sioux Nation’s final words were:

“I am a common human being. Some day, the people will come from the heart and look at each other as common human beings. When they do that, come from the heart, this country will be a good place.”12

This article is dedicated to the 38+2.

-------

Images Sources Andrew Myrick – Let Em Eat Grass 1970 TC Cannon, Google Arts & Culture https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/andrew-myrick-let-em-eat-grass-t-c-cannon-kiowa-and-caddo-southern-plains-indian-museum/uwGyR0PTzacQkA

Met Museum photo of Edgar Heap of Birds artwork https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/653721

Mankota riders https://nativenewsonline.net/currents/dakota-382-wokiksuye-memorial-riders-commemorate-1862-hangings-ordered-lincoln/

Sources

1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dakota_War_of_1862 2 https://www.mankatolife.com/attractions/reconciliation-park/ 3 Gibbon, Guy The Sioux: The Dakota and the Lakota Nations https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Sioux.html?id=s3gndFhmj9gC 4 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sioux 5 Beidler, Peter G. “Murdering Indians” October 17, 2013 https://books.google.com/books?id=4RRzAQAAQBAJ&dq=santee+men+murdered+white+farmer 6 History of the Santee Sioux Tribe in Nebraska http://www.santeedakota.org/santee_history_ii.htm 7 https://www.usdakotawar.org/history/acton-incident 8 Little Crow’s Letter https://www.usdakotawar.org/history/taoyateduta-little-crow 9 Regan, Sheila June 16, 2017 “In Minnesota, Listening to Native Perspective on Memorializing the Dakota War” Hyperallergic https://hyperallergic.com/385682/in-minnesota-listening-to-native-perspectives-on-memorializing-the-dakota-war/ 10 https://nativenewsonline.net/currents/dakota-382-wokiksuye-memorial-riders-commemorate-1862-hangings-ordered-lincoln/

11 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yankton_Sioux_Tribe

12 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/64427183/wakan_ozanzan-medicine_bottle

Monuments Depicting Victims of the Dakota Uprising http://www.dakotavictims1862.com/monuments/index.html Morton, MN Monuments https://sites.google.com/site/mnvhlc/home/renville-county/morton-monuments

More information regarding Dakota War of 1862 Holocaust and Genocide Studies: Native American University of Minnesota https://cla.umn.edu/chgs/holocaust-genocide-education/resource-guides/native-american

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Is a color-blind political system possible under our Constitution? If it is, the Supreme Court’s evisceration of the Voting Rights Act in 2013 did little to help matters. While black people in America today are not experiencing 1950s levels of voter suppression, efforts to keep them and other citizens from participating in elections began within 24 hours of the Shelby County v. Holder ruling and have only increased since then.

In Shelby County’s oral argument, Justice Antonin Scalia cautioned, “Whenever a society adopts racial entitlements, it is very difficult to get them out through the normal political processes.” Ironically enough, there is some truth to an otherwise frighteningly numb claim. American elections have an acute history of racial entitlements—only they don’t privilege black Americans.

For centuries, white votes have gotten undue weight, as a result of innovations such as poll taxes and voter-ID laws and outright violence to discourage racial minorities from voting. (The point was obvious to anyone paying attention: As William F. Buckley argued in his essay “Why the South Must Prevail,” white Americans are “entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally,” anywhere they are outnumbered because they are part of “the advanced race.”) But America’s institutions boosted white political power in less obvious ways, too, and the nation’s oldest structural racial entitlement program is one of its most consequential: the Electoral College.

Commentators today tend to downplay the extent to which race and slavery contributed to the Framers’ creation of the Electoral College, in effect whitewashing history: Of the considerations that factored into the Framers’ calculus, race and slavery were perhaps the foremost.

Of course, the Framers had a number of other reasons to engineer the Electoral College. Fearful that the president might fall victim to a host of civic vices—that he could become susceptible to corruption or cronyism, sow disunity, or exercise overreach—the men sought to constrain executive power consistent with constitutional principles such as federalism and checks and balances. The delegates to the Philadelphia convention had scant conception of the American presidency—the duties, powers, and limits of the office. But they did have a handful of ideas about the method for selecting the chief executive. When the idea of a popular vote was raised, they griped openly that it could result in too much democracy. With few objections, they quickly dispensed with the notion that the people might choose their leader.

But delegates from the slaveholding South had another rationale for opposing the direct election method, and they had no qualms about articulating it: Doing so would be to their disadvantage. Even James Madison, who professed a theoretical commitment to popular democracy, succumbed to the realities of the situation. The future president acknowledged that “the people at large was in his opinion the fittest” to select the chief executive. And yet, in the same breath, he captured the sentiment of the South in the most “diplomatic” terms:

There was one difficulty however of a serious nature attending an immediate choice by the people. The right of suffrage was much more diffusive in the Northern than the Southern States; and the latter could have no influence in the election on the score of the Negroes. The substitution of electors obviated this difficulty and seemed on the whole to be liable to fewest objections.

Behind Madison’s statement were the stark facts: The populations in the North and South were approximately equal, but roughly one-third of those living in the South were held in bondage. Because of its considerable, nonvoting slave population, that region would have less clout under a popular-vote system. The ultimate solution was an indirect method of choosing the president, one that could leverage the three-fifths compromise, the Faustian bargain they’d already made to determine how congressional seats would be apportioned. With about 93 percent of the country’s slaves toiling in just five southern states, that region was the undoubted beneficiary of the compromise, increasing the size of the South’s congressional delegation by 42 percent. When the time came to agree on a system for choosing the president, it was all too easy for the delegates to resort to the three-fifths compromise as the foundation. The peculiar system that emerged was the Electoral College.

Right from the get-go, the Electoral College has produced no shortage of lessons about the impact of racial entitlement in selecting the president. History buffs and Hamilton fans are aware that in its first major failure, the Electoral College produced a tie between Thomas Jefferson and his putative running mate, Aaron Burr. What’s less known about the election of 1800 is the way the Electoral College succeeded, which is to say that it operated as one might have expected, based on its embrace of the three-fifths compromise. The South’s baked-in advantages—the bonus electoral votes it received for maintaining slaves, all while not allowing those slaves to vote—made the difference in the election outcome. It gave the slaveholder Jefferson an edge over his opponent, the incumbent president and abolitionist John Adams. To quote Yale Law’s Akhil Reed Amar, the third president “metaphorically rode into the executive mansion on the backs of slaves.” That election continued an almost uninterrupted trend of southern slaveholders and their doughfaced sympathizers winning the White House that lasted until Abraham Lincoln’s victory in 1860.

In 1803, the Twelfth Amendment modified the Electoral College to prevent another Jefferson-Burr–type debacle. Six decades later, the Thirteenth Amendment outlawed slavery, thus ridding the South of its windfall electors. Nevertheless, the shoddy system continued to cleave the American democratic ideal along racial lines. In the 1876 presidential election, the Democrat Samuel Tilden won the popular vote, but some electoral votes were in dispute, including those in—wait for it—Florida. An ad hoc commission of lawmakers and Supreme Court justices was empaneled to resolve the matter. Ultimately, they awarded the contested electoral votes to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, who had lost the popular vote. As a part of the agreement, known as the Compromise of 1877, the federal government removed the troops that were stationed in the South after the Civil War to maintain order and protect black voters.

The deal at once marked the end of the brief Reconstruction era, the redemption of the old South, and the birth of the Jim Crow regime. The decision to remove soldiers from the South led to the restoration of white supremacy in voting through the systematic disenfranchisement of black people, virtually accomplishing over the next eight decades what slavery had accomplished in the country’s first eight decades. And so the Electoral College’s misfire in 1876 helped ensure that Reconstruction would not remove the original stain of slavery so much as smear it onto the other parts of the Constitution’s fabric, and countenance the racialized patchwork democracy that endured until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

What’s clear is that, more than two centuries after it was designed to empower southern whites, the Electoral College continues to do just that. The current system has a distinct, adverse impact on black voters, diluting their political power. Because the concentration of black people is highest in the South, their preferred presidential candidate is virtually assured to lose their home states’ electoral votes. Despite black voting patterns to the contrary, five of the six states whose populations are 25 percent or more black have been reliably red in recent presidential elections. Three of those states have not voted for a Democrat in more than four decades. Under the Electoral College, black votes are submerged. It’s the precise reason for the success of the southern strategy. It’s precisely how, as Buckley might say, the South has prevailed.

Among the Electoral College’s supporters, the favorite rationalization is that without the advantage, politicians might disregard a large swath of the country’s voters, particularly those in small or geographically inconvenient states. Even if the claim were true, it’s hardly conceivable that switching to a popular-vote system would lead candidates to ignore more voters than they do under the current one. Three-quarters of Americans live in states where most of the major parties’ presidential candidates do not campaign.

More important, this “voters will be ignored” rationale is morally indefensible. Awarding a numerical few voting “enhancements” to decide for the many amounts to a tyranny of the minority. Under any other circumstances, we would call an electoral system that weights some votes more than others a farce—which the Supreme Court, more or less, did in a series of landmark cases. Can you imagine a world in which the votes of black people were weighted more heavily because presidential candidates would otherwise ignore them, or, for that matter, any other reason? No. That would be a racial entitlement. What’s easier to imagine is the racial burdens the Electoral College continues to wreak on them.

Critics of the Electoral College are right to denounce it for handing victory to the loser of the popular vote twice in the past two decades. They are also correct to point out that it distorts our politics, including by encouraging presidential campaigns to concentrate their efforts in a few states that are not representative of the country at large. But the disempowerment of black voters needs to be added to that list of concerns, because it is core to what the Electoral College is and what it always has been.

The race-consciousness establishment—and retention—of the Electoral College has supported an entitlement program that our 21st-century democracy cannot justify. If people truly want ours to be a race-blind politics, they can start by plucking that strange, low-hanging fruit from the Constitution.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two Poems by Cathy Arellano -Fugitive Slave Act and Immigration, a found poem based on “The Long Struggle for America’s Soul” by Andrew Delbanco* and Alfie, What’s It All About?

Art is copyright ©2017 Hedy Treviño. Mixed media, acrylic base, collage on gold foil. All rights reserved.

Fugitive Slave Act and Immigration, a found poem based on “The Long Struggle for America’s Soul” by Andrew Delbanco*

southern border separation children parents president’s denigration nonwhite migrants denying birthright citizenship pledge federal troops caravan frantic refugees

not first time president threatened return them to horrors fled African-Americans not human property no different cattle sheep

South Carolina “Act to Prevent Runaways” 1683 hundred years later Georgia nightly slave patrol

Philadelphia 1787 problem new nation slaves running freedom

Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 Constitution founding fathers stop them

“right to recover our slaves” stating easier than carrying out just as “Build the Wall!” easier than building

obliged to return runaways

obliged to return stray livestock stolen cash

but boundary slavery freedom porous

slave owners cut off shoes collected at night runaways resisting killed with impunity only witness killer himself

most fugitives never far tendons cut faces branded kept on trying

just as in our time immigrants keep coming 1840s fugitive slave problem gravest of all questions calls for secession congress tried to solve August 1850 Fugitive Slave Act

president signed law law without mercy denied most basic right habeas corpus right to challenge detention forbade own defense trial by jury disallowed exonerating evidence criminalized sheltering fugitive required local authorities assist recovering lost human property

free Black people in North even never been enslaved lives infused with terror of being deported

in South deepened despair already desperate

1851 free Black people organize resistance

Norfolk, Va. slave catchers seized young man Shadrach with his waiter’s apron still on Black crowd gathered Court Square rushed courtroom hustled whisked from Boston to Cambridge to Canada

Lancaster County, Pa. slave owner tried force return shot killed by Black man

Syracuse biracial crowd attacked police station clubs axes battering ram Canada

Milwaukee Joshua Glover escaped held until twenty men large timber bumb bumb bumb down door out Glover

1850 more than three million Black people legally enslaved within country’s borders

politicians racist

chief justice United States Blacks have no rights White man bound to respect

Boston New Bedford Syracuse Cincinnati Rochester “sanctuary cities”

Black people feared law enforcement

congress courts collapsed

fugitive slaves 19th century undocumented immigrants today non-persons

Who is isn’t human?

Declaration of Independence “all men created equal “unalienable rights” “life, liberty, pursuit of happiness”

1854 Abraham Lincoln readopt the Declaration

postwar constitutional amendments guarantee citizenship right to vote

former slaves naturalized immigrants

The New Deal tried The Civil Rights Movement tried dismantle Jim Crow

age of trump rights constricted rescinded

self-evident truth

all people life liberty pursuit of happiness long way from settled

Note: I have adjusted some capitalization, removed most punctuation, changed Delbanco’s “illegal” and replaced with “undocumented” before “immigrant(s)”. Words are in same order as article.

Alfie, What’s It All About?

every Saturday during our walk up and down the coolest street in town we stopped at the American Music Store (they changed their name to Música Latina when us Latinos finally reached a critical and commercial mass)

this was Mom’s spot she only bought one LP or a couple 45s each time but “each time” times “every Saturday” equals stacks and stacks of Stax fingers ready to snap on yellow background Motown road maps guiding the way with its red star

and the rest of our housemates Capitol, Atlantic, RCA, Buddha Tamla, Scepter, Capitol, Philips crashing in the Livingroom behind to the left of right of in front of her stereo

one Saturday when we were 6 and 7 years old Mom made a payment on our inheritance her magic her balm her joy

You girls, pick a record my older sister and I knew this was a moment like when someone else’s Mom teaches them to bake cookies Mom was offering us something precious

it was sweet not like later when Mom let my sister smoke in front of her when she was 15

it wasn’t mine or my sister’s birthday I hadn’t ever dreamed this moment would arrive but I was ready we both were

My sister turned around ran to the back of the store dug in a white bin flipped through grabbed her catch clutched it in her arms ran back to us at the counter showed us her treasure

The Three Little Pigs

I couldn’t read very well but I recognized the pigs and wolf on the cover behind the counter Enrique turned to me for my order I didn’t run just said

Alfie

he looked at Mom then back at me by Dionne Warwick?

huh?

Yes, that one Mom told him

we returned the next Saturday and the next and the next Mom bought us many more 45s not as many as she bought herself but enough to begin our own stacks

my sister started buying classic Oldies “Angel Baby” and “Sitting in the Park” I bought Prince’s “I Wanna Be Your Lover” Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” for the until then unheard of price of $4.99 and later AC/DC’s “You Shook Me All Night Long”

when she died in 1984 after a month in the hospital when we were 18 and 19 Mom had amassed so many records and we had to move so fast and were so lost in the chaos we threw them away

I wish I had all her records back I’d play them for my partner our son

no, I’d trade hers, mine, my sister’s, all the 45s, LPs, and CDs in the world for one more moment with her

The broken-hearted lesbian love poems in Cathy Arellano’s I LOVE MY WOMEN, SOMETIMES THEY LOVE ME are suitable for anyone who has loved, been loved, or been left. I LOVE MY WOMEN was released in Fall 2017 from Kórima Press. In 2016, Kórima published SALVATION ON MISSION STREET, Arellano’s family memoir in poems and stories set in San Francisco from the 1960s to the 2000s. SALVATION won the 2017 Golden Crown Literary Society’s Debut Author Award.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Who Were The Republicans In The Civil War

New Post has been published on https://www.patriotsnet.com/who-were-the-republicans-in-the-civil-war/

Who Were The Republicans In The Civil War

Gop Overthrown During Great Depression

What if Civil War broke out between Republicans and Democrats?

The pro-business policies of the decade seemed to produce an unprecedented prosperityuntil the Wall Street Crash of 1929 heralded the Great Depression. Although the party did very well in large cities and among ethnic Catholics in presidential elections of 19201924, it was unable to hold those gains in 1928. By 1932, the citiesfor the first time everhad become Democratic strongholds.

Hoover was by nature an activist and attempted to do what he could to alleviate the widespread suffering caused by the Depression, but his strict adherence to what he believed were Republican principles precluded him from establishing relief directly from the federal government. The Depression cost Hoover the presidency with the 1932 landslide election of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition controlled American politics for most of the next three decades, excepting the presidency of Republican Dwight Eisenhower 19531961. The Democrats made major gains in the 1930 midterm elections, giving them congressional parity for the first time since Wilson’s presidency.

Election Of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was born into relative poverty in Kentucky in 1809. His father worked a small farm. In his youth, Lincoln held down a variety of jobs before moving to Illinois and becoming a lawyer.

Lincoln sarted to get involved in local politics. Lincolns political views came to the fore after the Kansas Nebraska Act where he spoke out against the spread of slavery.

1860 was the presidential election year. In the spring the two main parties, the Democrats and the Republicans chose their candidates.

Abraham Lincoln . The Republicans held their convention in Chicago. Lincoln was chosen with overwhelming support.

Stephen Douglas . The Democratic Party was split. Northern Democrats wished for further compromise over slavery. Douglas was chosen as their candidate.

John Breckinridge . The Southern Democrats wanted no compromise on slavery. They wished to see slavery guaranteed and were trying to take over the party. They left the Democrat Convention in Baltimore and selected their own candidate John Breckinridge.

John Bell . The Constitutional Union Party was trying to prevent the country dividing over the issue of slavery.

The election campaign of 1860 was unusual. Lincoln only campaigned in the North and Breckinridge in the South. Stephen Douglas exhausted himself by campaigning in all the states.

The result was that Lincoln became President. He won all 17 states in the North but none in the South. The country was now more divided than ever.

Opinionheres What Getting Rid Of Mississippis Confederate Flag Means And Doesnt

In the summer of 1864, for example, the war was going poorly, and Republicans feared that a public sick of defeat would toss Lincoln out of office. Then Gen. William T. Sherman won a resounding victory at Atlanta in September. Lincolnâs landslide re-election in 1864 seemed to many at the time and since then to be the result of that military success.

But by analyzing House elections in 1864, Kalmoe uncovered a different story. In the 1860s, congressional contests were held over the course of the entire year, rather than on the same day as the presidential contest. If Republicans were in trouble before September, House GOP candidates should have been crushed by Democratic challengers. But instead, Kalmoe found, Republican vote share changed little over time. Lincoln was on his way to win before Atlanta. Republican partisans supported the president even though the war was going poorly, as they did when the war was going well.

In the Civil War era, partisanship had a strong effect on how people interpreted good or bad news.

Republican refusal to abandon Trump seems ominous. Trumpâs disastrous response to a national health crisis has led to tens of thousands of unnecessary deaths. If his voters arenât moved by that, how can we hold government accountable to the people at all? Partisanship seems to be a recipe for denial, dysfunction and death.

Read Also: Did Republicans Cut Funding For Benghazi

Read Also: Parties Switched Platforms

President Truman Integrates The Troops: 1948

Fast forward about sixty shitty years. Black people are still living in segregation under Jim Crow. Nonetheless, African Americans agree to serve in World War II.

At wars end, President Harry Truman, a Democrat, used an Executive Order to integrate the troops.

These racist Southern Democrats got so mad that their chief goblin, Senator Strom Thurmond, decided to run for President against Truman. They called themselves the Dixiecrats.

Of course, he lost. Thurmond remained a Democrat until 1964. He continued to oppose civil rights as a Democrat. He gave the longest filibuster in Senate history speaking for 24 hours against the 1957 Civil Rights Act.

Recommended Reading: How Many States Are Controlled By Republicans

Republicans And Democrats After The Civil War

Its true that many of the first Ku Klux Klan members were Democrats. Its also true that the early Democratic Party opposed civil rights. But theres more to it.

The Civil War-era GOP wasnt that into civil rights. They were more interested in punishing the South for seceding, and monopolizing the new black vote.

In any event, by the 1890s, Republicans had begun to distance themselves from civil rights.

You May Like: Why Does Donald Trump Wear Red Ties

Horace Greeley Proceedings Of The First Three Republican National Conventions Of 1856 1860 And 1864 78

“Republican Party Platform of 1856, American Presidency Project, at , accessed April 25, 2014.

Abraham Lincoln, Speech at Carlinville, Illinois, August 31, 1858, in Abraham Lincoln Association, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, edited by Roy Basler, at , accessed April 25, 2014.

Abraham Lincoln, Emancipation Proclamation, January 1, 1863, at United States National Archives, Americas Historical Documents, at , accessed April 25, 2014.

University of Richmond Digital Scholarship Lab, Voting America: Presidential Election, 1864, at , accessed January 9, 2014.

History Of The Republican Party

Republican Party

The Republican Party, also referred to as the GOP , is one of the two major political parties in the United States. It is the second-oldest extant political party in the United States; its chief rival, the Democratic Party, is the oldest.

The Republican Party emerged in 1854 to combat the KansasNebraska Act and the expansion of slavery into American territories. The early Republican Party consisted of northern Protestants, factory workers, professionals, businessmen, prosperous farmers, and after 1866, former black slaves. The party had very little support from white Southerners at the time, who predominantly backed the Democratic Party in the Solid South, and from Catholics, who made up a major Democratic voting block. While both parties adopted pro-business policies in the 19th century, the early GOP was distinguished by its support for the national banking system, the gold standard, railroads, and high tariffs. The party opposed the expansion of slavery before 1861 and led the fight to destroy the Confederate States of America . While the Republican Party had almost no presence in the Southern United States at its inception, it was very successful in the Northern United States, where by 1858 it had enlisted former Whigs and former Free SoilDemocrats to form majorities in nearly every Northern state.

Also Check: How Many States Are Controlled By Republicans

How Did The Spanish Civil War End

The final Republican offensive stalled at the Ebro River on November 18, 1938. Within months Barcelona would fall, and on March 28, 1939, some 200,000 Nationalist troops entered Madrid unopposed. The city had endured a siege of nearly two-and-a-half years, and its residents were in no condition to resist. The following day the remnant of the Republican government surrendered; Franco would establish himself as dictator and remain in power until his death on November 20, 1975.

Spanish Civil War, , military revolt against the Republican government of Spain, supported by conservative elements within the country. When an initial military coup failed to win control of the entire country, a bloody civil war ensued, fought with great ferocity on both sides. The Nationalists, as the rebels were called, received aid from Fascist Italy and NaziGermany. The Republicans received aid from the Soviet Union as well as from the International Brigades, composed of volunteers from Europe and the United States.

Pietistic Republicans Versus Liturgical Democrats: 18901896

MOOC | The Radical Republicans | The Civil War and Reconstruction, 1865-1890 | 3.3.5

Voting behavior by religion, Northern U.S. late 19th century % Dem 90 10

From 1860 to 1912, the Republicans took advantage of the association of the Democrats with “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion. Rum stood for the liquor interests and the tavernkeepers, in contrast to the GOP, which had a strong dry element. “Romanism” meant Roman Catholics, especially Irish Americans, who ran the Democratic Party in every big city and whom the Republicans denounced for political corruption. “Rebellion” stood for the Democrats of the Confederacy, who tried to break the Union in 1861; and the Democrats in the North, called “Copperheads, who sympathized with them.

Demographic trends aided the Democrats, as the German and Irish Catholic immigrants were Democrats and outnumbered the English and Scandinavian Republicans. During the 1880s and 1890s, the Republicans struggled against the Democrats’ efforts, winning several close elections and losing two to Grover Cleveland .

Religious lines were sharply drawn. Methodists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Scandinavian Lutherans and other pietists in the North were tightly linked to the GOP. In sharp contrast, liturgical groups, especially the Catholics, Episcopalians and German Lutherans, looked to the Democratic Party for protection from pietistic moralism, especially prohibition. Both parties cut across the class structure, with the Democrats more bottom-heavy.

Also Check: Was Trump A Democrat

Birthplace Of The Republican Party

Meeting at a in Ripon on March 20, 1854, some 30 opponents of the called for the organization of a new political party . The group also took a leading role in the creation of the in many northern states during the summer of 1854. While conservatives and many moderates were content merely to call for the restoration of the or a prohibition of slavery extension, the group insisted that no further political compromise with slavery was possible.

The February 1854 meeting was the first political meeting of the group that would become the Republican Party. The modern , a Republican think tank, takes its name from Ripon, Wisconsin.

Ripon is located in the northwest corner of .

According to the , the city has a total area of 5.02 square miles , of which, 4.97 square miles is land and 0.05 square miles is water.

Presidency Of George W Bush

In the aftermath of the , the nationâs focus was changed to issues of national security. All but one Democrat voted with their Republican counterparts to authorize President Bushâs 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. House leader Richard Gephardt and Senate leader Thomas Daschle pushed Democrats to vote for the USA PATRIOT Act and the invasion of Iraq. The Democrats were split over invading Iraq in 2003 and increasingly expressed concerns about both the justification and progress of the War on Terrorism as well as the domestic effects from the Patriot Act.

Recommended Reading: How Many States Are Controlled By Republicans

Social Conservatism And Traditionalism

Social conservatism in the United States is the defense of traditional social norms and .

Social conservatives tend to strongly identify with American nationalism and patriotism. They often vocally support the police and the military. They hold that military institutions embody core values such as honor, duty, courage, loyalty, and a willingness on the part of the individual to make sacrifices for the good of the country.

Social conservatives are strongest in the South and in recent years played a major role in the political coalitions of and .

The Founding Fathers Disagree

Differing political views among U.S. Founding Fathers eventually sparked the forming of two factions. George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and John Adams thus formed The Federalists. They sought to ensure a strong government and central banking system with a national bank. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison instead advocated for a smaller and more decentralized government, and formed the Democratic-Republicans. Both the Democratic and the Republican Parties as we know them today are rooted in this early faction.

Read Also: How Many States Are Controlled By Republicans

On This Day The Republican Party Names Its First Candidates

On July 6, 1854, disgruntled voters in a new political party named its first candidates to contest the Democrats over the issue of slavery. Within six and one-half years, the newly christened Republican Party would control the White House and Congress as the Civil War began.

For a brief time in the decade before the Civil War, the Democratic Party of Andrew Jackson and his descendants enjoyed a period of one-party rule. The Democrats had battled the Whigs for power since 1836 and lost the presidency in 1848 to the Whig candidate, Zachary Taylor. After Taylor died in office in 1850, it took only a few short years for the Whig Party to collapse dramatically.

There are at least three dates recognized in the formation of the Republican Party in 1854, built from the ruins of the Whigs. The first is February 24, 1854, when a small group met in Ripon, Wisconsin, to discuss its opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The group called themselves Republicans in reference to Thomas Jeffersons Republican faction in the American republics early days. Another meeting was held on March 20, 1854, also in Ripon, where 53 people formally recognized the movement within Wisconsin.

On July 6, 1854, a much-bigger meeting in Jackson, Michigan was attended by about 10,000 people and is considered by many as the official start of the organized Republican Party. By the end of the gathering, the Republicans had compiled a full slate of candidates to run in Michigans elections.

The Uss Hispanic Population Swells

In recent decades, America has gone through a major demographic shift in the form of Hispanic immigration both legal and illegal.

The legal immigration has major electoral implications, as the electorate is becoming more diverse, and there is a new pool of voters that the parties can try to win over. Currently, the Democrats are doing a better job of it this population growth already helped California and New Mexico become solidly Democratic states on the presidential level, and helped tip swing states Florida and Colorado toward Barack Obama too.

But meanwhile, illegal immigration has also risen to the top of the political agenda. Democrats, business elites, and some leading Republicans have tended to support reforming immigration laws so that more than 10 million unauthorized immigrants in the US can get legal status. Many conservatives, though, tend to denounce such policies as “amnesty,” and being “tough on illegal immigration” has increasingly become a badge of honor on the right.

The bigger picture is that while the country is growing increasingly diverse, non-Hispanic whites are still a majority, and Trump’s strong support among them was sufficient to deliver him the presidency.

You May Like: Did Trump Call Republicans Stupid In 1998

If There Was A Republican Civil War It Appears To Be Over

The party belongs to Trump for as long as he wants it.

By Jamelle Bouie

Opinion Columnist

That there is a backlash against the seven Republican senators who voted to convict Donald Trump of inciting a mob against Congress is not that shocking. What is shocking is how fast it happened.

Senator Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, for example, was immediately censured by the Louisiana Republican Party. We condemn, in the strongest possible terms, the vote today by Senator Cassidy to convict former President Trump, the party announced on Twitter. Another vote to convict, Richard Burr of North Carolina, was similarly rebuked by his state party, which censured him on Monday. Senators Ben Sasse of Nebraska and Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania are also in hot water with their respective state parties, which see a vote against Trump as tantamount to treason. We did not send him there to vote his conscience. We did not send him there to do the right thing or whatever he said hes doing, one Pennsylvania Republican Party official explained. We sent him there to represent us.

That this backlash was completely expected, even banal, should tell you everything you need to know about the so-called civil war in the Republican Party. It doesnt exist. Outside of a rump faction of dissidents, there is no truly meaningful anti-Trump opposition within the party. The civil war, such as it was, ended four-and-a-half years ago when Trump accepted the Republican nomination for president.

Ideology And Political Philosophy

MOOC | The Radical Republicans | The Civil War and Reconstruction, 1850-1861 | 1.6.6

In terms of governmental economic policies, American conservatives have been heavily influenced by the or tradition as expressed by and and a major source of influence has been the . They have been strongly opposed to .

Traditional conservatives tend to be anti-ideological, and some would even say anti-philosophical, promoting, as explained, a steady flow of “prescription and prejudice”. Kirk’s use of the word “prejudice” here is not intended to carry its contemporary pejorative connotation: a conservative himself, he believed that the inherited wisdom of the ages may be a better guide than apparently rational individual judgment.

There are two overlapping subgroups of social conservativesthe traditional and the religious. Traditional conservatives strongly support traditional codes of conduct, especially those they feel are threatened by social change and modernization. For example, traditional conservatives may oppose the use of female soldiers in combat. Religious conservatives focus on conducting society as prescribed by a religious authority or code. In the United States, this translates into hard-line stances on moral issues, such as and . Religious conservatives often assert that “America is a Christian nation” and call for laws that enforce .

Read Also: Dems For Trump

1 note

·

View note

Text

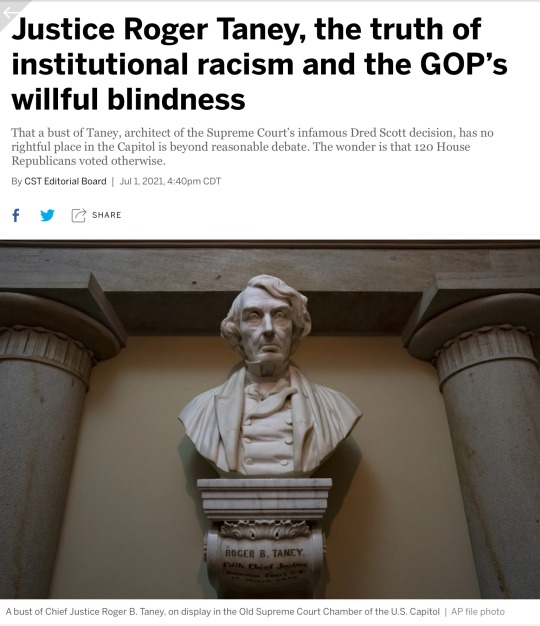

If you’re looking for the patron saint of institutional racism in the United States, Roger B. Taney is your man.

That a bust of Chief Justice Taney in the U.S. Capitol should be removed, as the House voted last week to do, is beyond reasonable debate. It is the lowest hanging fruit in our nation’s efforts to reckon more honestly with its past.

The only wonder is that 120 House Republicans voted against the measure. The question is not what’s to be done about Taney, but what’s to be done about them. And what’s to be done about the Republicans in the Senate who are sure to vote against the measure, too.

They have declared where they stand: Against any reconsideration of our nation’s past that might annoy their most racist supporters in the next Republican primary. And in favor of — the perfect metaphor — continued white washing.

Chicago knows institutional racism

If you live in Chicago and know the worst of our city’s own history, you can only marvel at such willful blindness.

To argue that institutional racism is a fiction — or that removing the bust of somebody like Taney is an “erasing” of history — looks like a farce to those of us who grew up and live in a city where whole neighborhoods once were red-lined by mortgage companies so Black folks couldn’t live there, where mobile classrooms called “Willis wagons” were installed to keep Black children from having to be bused to white schools, and where an expressway, the Dan Ryan, was strategically located to create a wall between Black and white neighborhoods.

Listen, we know. There’s also a lot of over-the-top “wokeness” going around. There are calls for corrective actions, such as taking down statues of Abe Lincoln, that ignore historical context and go too far. There is plenty of room all around, that is to say, for a more nuanced debate about our nation’s history and how its failings play out to this day.

But Justice Taney? To oppose the removal of his bust from a place of honor in the Capitol, on any grounds, is to declare you really don’t give a damn about truth, racial healing and reconciliation.

Taney was the author of the infamous Dred Scott decision, often called the worst legal decision in the Supreme Court’s history. The court held in 1857 that Scott, as a Black man, was not an American citizen and therefore had no right to sue. The court also ruled that legislation restricting slavery in certain territories was unconstitutional.

Taney reviled in his own time

To those who argue that Taney was simply a man of his times and should not be judged by the standards of today, we would point out that he was reviled by many in his own day. Even this business of the bust is nothing new.

When a senator from Illinois in 1865, shortly after Taney’s death, proposed that a bust of the chief justice be put on display in the Capitol, he was mocked.

A senator from New Hampshire said Taney was nothing but a “traitor” who sought to place the nation “forever by judicial authority under the iron rule of the slave-masters.”

A senator from Massachusetts warned that “the name of Taney is to be hooted down the page of history. Judgment is beginning now.”

It would not be until 1874 that Congress passed a bill to honor Taney with a bust, creating a new monument to white supremacy just as Reconstruction was being dismantled in the South and Jim Crow was kicking in.

Removing the bust of Taney now is not about “erasing history.” It’s about getting history right.

A willful blindness

A willful blindness to the obvious, largely on the part of those who have made a cult of Donald Trump and those who fear that cult, threatens to destroy our country.

It has people believing, or pretending to believe, that the 2020 election was “stolen” from Trump, that former Vice President Mike Pence had the authority to hand the election to Trump, that COVID-19 vaccines are a threat to freedom, and that left-wing activists were behind the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol.

It has people believing that the threat of global warming is not real, that Dr. Anthony Fauci conspired to cover up the actual origins of the coronavirus, that wind turbines cause cancer, and that Biden is senile and Vice President Kamala Harris is secretly pulling the strings.

And it has people believing a brush-stroked children’s version of our nation’s complicated history, one in which the Founding Fathers were beyond reproach, slavery was unfortunate but its legacy dead and gone, and racism is largely a matter of individual prejudices, not something woven into laws and institutions.

As a person, Taney was a racist. As a jurist, he was a chief architect of institutional racism. His bust should be removed.

That there is a willful blindness to this obvious fact, as to so many others, should distress us all.

0 notes

Text

People are calling for museums to be abolished. Can whitewashed American history be rewritten?

New Post has been published on https://appradab.com/people-are-calling-for-museums-to-be-abolished-can-whitewashed-american-history-be-rewritten/

People are calling for museums to be abolished. Can whitewashed American history be rewritten?

Written by Brian Boucher, Appradab

After years of resisting calls for its removal, New York’s American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) has asked the city to dislodge from its front steps an equestrian monument to Theodore Roosevelt, the twenty-sixth US president, which depicts him charging forward, and towering over two mostly nude figures, one Black and one Indigenous.

In a statement dated June 2020 sent to museum staff, posted on the museum’s website, Ellen Futter, president of the institution’s board, said, “As we strive to advance our institution’s, our City’s, and our country’s passionate quest for racial justice, we believe that removing the statue will be a symbol of progress and of our commitment to build and sustain an inclusive and equitable Museum community and broader society.” (After the announcement President Donald Trump tweeted, “Ridiculous, don’t do it!”)

Might this concession be a harbinger of other changes ahead for American museums? How can institutions whose leadership is often overwhelmingly White rethink their staffing, collections and exhibitions, much less move toward more truly equitable governance? Or, some ask, should museums continue to exist in anything like their current form?

The controversial statue of former President Theodore Roosevelt outside of the Museum of Natural History, featuring a Black man and a Indigenous man at his sides Credit: Spencer Platt/Getty Images North America/Getty Images

The Natural History Museum’s statement places the monument’s removal in the context of “the ever-widening movement for racial justice that has emerged after the killing of George Floyd,” a Black man who was killed by four police officers in Minneapolis, Minnesota, one of whom knelt on his neck for nearly nine minutes. After a video of Floyd’s killing went viral, tens of thousands took to the streets in protest in the US and around the world, even in the midst of a pandemic, to demand accountability for police brutality and to call for the defunding, or even the abolition of local police forces, among other demands.

The presence of an Indigenous figure in the Roosevelt monument, and the museum itself, have a very personal meaning for Wendy Red Star, an artist and member of the Crow tribe. She created a project, “The 1880 Crow Peace Delegation,” about a group of Crow chiefs who traveled to Washington, DC, that year to try to negotiate a peace treaty. In researching for the project, she found that the remains of one of those chiefs, Pretty Eagle, had been stolen from a burial site and later sold to the AMNH. The tribe was able to repatriate the remains in the 1990s.

“It wasn’t until I did this project that I learned about that,” Red Star said in a phone interview. “The Roosevelt monument was the first thing I thought of. To me, it’s a really direct connection to how my people have been presented at the museum — along with the dinosaur bones as part of the natural world. It’s always been such a surreal experience to see my community’s objects on display and watch people observing them as if these were peoples of the past.”

Just as government, law enforcement, and all forms of authority are being questioned in this moment of upheaval, museums worldwide have come in for intense scrutiny, and the situation on the ground is changing very fast. Earlier this month, dozens of current and former staffers of multiple cultural institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum, the Guggenheim Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art as well as institutions nationwide, published an open letter accusing the institutions of unfair treatment of employees of color and saying that “your covert and overt white supremacy that has benefited the institution, through the unrecognized dedication and hard labor of Black/Brown employees, with the expectation that we remain complacent with the status quo, is over.”

Apsáalooke Feminist #4, 2016, by Wendy Red Star Credit: Courtesy Wendy Red Star

Within days, staffers at the Guggenheim and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art openly accused the institutions’ leadership of racism. In an emailed statement to Appradab, Richard Armstrong, director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation, said the institution was prepared to address these concerns:

“As a society, we are confronting sustained injustices never resolved, and feel today the pain and anger of previous moments of turmoil. The Guggenheim addresses the shared need of great reform, and long overdue equality, and want to reaffirm that we are dedicated to doing our part.

“In this period of self-reflection and reckoning, we will engage in dialogue with our staff and review all processes and procedures to lead to positive change,” he continued. “We are expediting our ongoing … efforts to produce an action plan for demonstrable progress.”

The Metropolitan Museum declined to comment. The Museum of Modern Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art did not respond to requests for comment.

Museums have also been critiqued for issuing anodyne statements that failed to mention Floyd or the Black Lives Matter movement. The Getty Museum, in Los Angeles, posted an unspecific call for “equity and fairness” on Instagram, and later apologized; the director of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art privately apologized to Black artist Glenn Ligon for using a work of his from the museum’s holdings on social media without his permission, according to the New York Times.

Decolonize This Place protesting outside the American Museum of Natural History Credit: Andres Rodriguez/Decolonize This Place

The AMNH’s statement does not mention the groups that have for several years organized protests calling for the Roosevelt monument’s removal. In a phone interview, Decolonize This Place (DTP) organizer Amin Husain pointed out that removal of the monument was just one of three demands that Decolonize had placed on the museum, which include internally renaming Columbus Day as Indigenous People’s Day and rethinking the museum’s displays.