#Chadian Arabic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Chadian Arabic: An Overview of Chad's Fascinating Arabic Language and Culture

Jump into the Fascinating World of Chadian Arabic The rich tapestry of languages spoken across the globe is a testament to the diversity of human cultures. Among these linguistic marvels is Chadian Arabic, a language that holds a special place in the heart of Chad and its neighboring regions. In this comprehensive article, we’ll embark on an engaging journey through the intricacies of Chadian…

View On WordPress

#Arabic dialects#Chad language#Chadian Arabic#Cultural Heritage#language diversity#linguistic communication

0 notes

Text

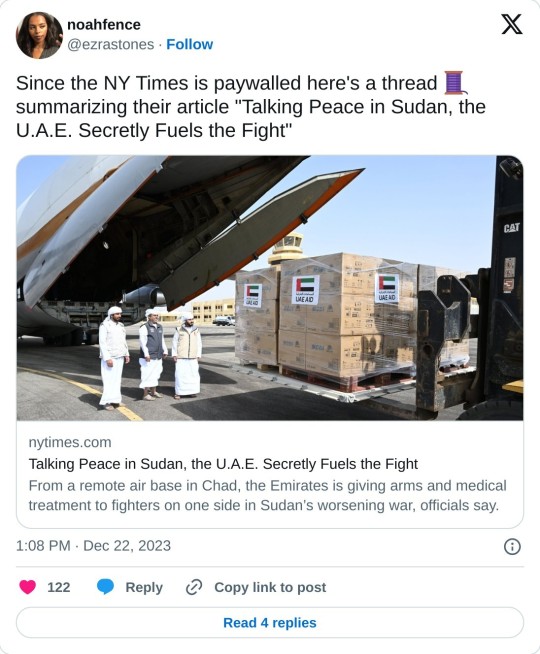

A senior Sudanese army commander said on Sunday that airports in neighbouring Chad would be considered military targets, accusing the United Arab Emirates (UAE) of supporting the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Sudan’s ongoing conflict.[...]

Sudan’s defence ministry said in December last year that the UAE had supplied the RSF with strategic drones equipped with guided missiles and that attacks had been launched from within Chad.[...]

“We will take retaliatory action against the UAE, the corrupt centres of influence in South Sudan, and we will take retaliatory action against Mohamed Kaka, the President of Chad,” al-Atta said. “And we warn him that the airports of N’Djamena and Amdjarass are legitimate targets for the Sudanese Armed Forces.”

He added: “We know what we are saying, and our words are not a joke at all, nor are they spoken lightly.”

23 Mar 25

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

The extent of Russia’s influence in Sudan goes beyond its involvement in the current war. It’s not only fueling war in Sudan but it’s the reason Russia is able to continue its war in Ukraine and other places despite being sanctioned by the West. Russia is surviving western sanctions by exploiting, smuggling gold and aiding the Sudanese Transitional Military Council (TMC) in the suppression of the pro-civilian led government movement.

In 2014, Putin was vocal about creating an economic plan to circumvent potential Western sanctions tied to the Ukraine war. By 2017, they began extending lifelines to autocrats, and unsurprisingly, former Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir joined Putin’s economic pipeline. After a meeting between the two presidents, Russian geologists and mineralogists employed by Meroe Gold arrived in Sudan.

The Russian companies, including Wagner, a private military company linked to Russia and frequently engaged in conflicts worldwide, began establishing a presence in Sudan. Notably, Wagner leader is under US sanctions, accused of meddling in the 2020 US elections. In 2020, under Trump administration, the group was sanctioned for its heavy exploitation of Sudan’s natural resources. The exploitation was so evident that they literally had to be sanctioned by Trump, which is quite surprising.

In 2019, following Al-Bashir’s overthrow, Wagner transitioned to striking deals with the Rapid Support Forces militia general, Hemeti. This militia, formerly known as Janjaweed and implicated in the Darfur genocide, received weapons and training. Wagner, in return, gained access to smuggled gold and devised plans to maintain control, ultimately contributing to today’s proxy war in Sudan.

The method of gold smuggling involved disguising it as flying cookies and concealing the smuggled gold beneath Russian cookie boxes. 🤣

In 2022, @/nimaelbagir a Sudanese journalist and CNN’s Chief International Investigative Correspondent went to a Russian owned gold mining facility in Sudan. Watch her report here ⬇️

Full report here:

In June 2022, the Darfur Bar Association (DBA) launched an investigation and confirmed Wagner mercenaries presence in South Darfur after its attack on gold miners in South Darfur. The investigation also revealed that the Transitional Military council (SAF+RSF) knew about the presence of Wagner in Sudan and in 2019 a copy of the report was actually sent to then prime minister Hamadok.

The DBA investigation also revealed how the UAE is involved in Sudan and its role in the current war. There’s also an extensive investigation report on the role of the UAE in Sudan by the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal that proves the UAE involvement in Sudan.

How are the UAE and Russia linked you might ask?

1) Most Sudanese gold passes through the United Arab Emirates. Unofficial data from the United Arab Emirates reported that over $1.7bn of Sudanese gold landed in Dubai in 2021, just under half the value of all the country’s exports. But there is little accurate data tracking it after it arrives in the UAE (arrives via Russia). Most industry exports reckon that official figures account for less than a quarter of total gold sales. Khartoum’s central bank recorded gold exports of 26.4 tonnes from January to September in 2021 but estimates over 100 tonnes would have been smuggled out during that period. (Africa Confidential)

Amdjarass, the Chadian town just across the Sudanese border, is the base from which the UAE is running an operation supposedly to help Sudanese refugees. But behind the façade of what the UAE maintains are humanitarian efforts, lies covert weapons, drones, and medical treatment to injured RSF fighters. (The Africa Report)

A U.S. Ally Promised to Send Aid to Sudan. It Sent Weapons Instead. (WSJ)

The New York Times report on how the UAE is further involved ⬇️

2) In April 2023, following the onset of the war in Sudan, the Wagner group was exposed by CNN for allegedly supplying missiles to the RSF in their conflict against the Sudanese armed forces (SAF). The arms came through the UAE under the guise of humanitarian aid for Sudanese refugees in Chad. These armaments were destined for the UAE’s local proxy, the RSF, in Sudan’s western region. In addition, CNN exposed that the shipments of surface-to-air missiles provided by Wagner were destined for the RSF via flights shuttling the hardware from Latakia, Syria, to Khadim, Libya, and then airdropped to northwestern Sudan, where the RSF enjoys a strong presence. This support from Wagner is considered a significant factor contributing to the RSF’s continuation of the war and their reported atrocities against Sudanese civilians, including killing, looting, sexual violence, and mass destruction of Sudan’s infrastructure.

The satellite images from CNN and the open-source group “All Eyes On Wagner,” provide evidence of an escalated Wagner presence at the bases of Khalifa Haftar, the leader of a Libyan militia supported by Wagner, in Libya. This heightened presence was purportedly in preparation to assist the RSF militia against the SAF.

Full report here:

3) There is evidence that the UAE has been funding Wagner in Libya to help reduce the financial burden on Russia for its Libyan operations and has been deploying these forces to prop up its ally, General Khalifa Haftar, who has been fighting the UN-recognized Government of National Accord in Tripoli. The report that the UAE is funding Wagner in Libya actually came from the US department of defense, which again is a surprise considering the close alliance of the US and the UAE.

East Africa Counterterrorism Operation, North and West Africa Counterterrorism Operation Quarterly Report to Congress, July 1, 2020‒September 30, 2020

#repost of someone else’s content#twitter repost#sudan#keep eyes on sudan#sudanese genocide#uae#russia#putin#wagner#rsf#proxy war#genocide#free sudan#liberate sudan

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

So far Armies of Sand: The Past, Present and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness has been enjoyable, informative but unsatisfying (and I'm getting a vibe that it's going to get worse). It's presenting a history and theory of military underperformance by Arab government forces post-WW2, written by an ex-CIA-turned-academic guy who clearly has a great breadth of knowledge about the topic.

He presents compelling evidence that military performance in Arab states over this period has been dreadful (which. isn't controversial), to an extent that it really looks like a pattern and requires an explanation. He puts up four factors that he says are popular explanations for the pattern among analysts and military officals and historians: over-reliance on inappropriate Soviet doctrine, widespread military politicisation, economic underdevelopment, and Arab culture. For each one, he gives in-depth case studies of conflicts involving Arab armies with these characteristics and others with non-Arab armies demonstrating the same characteristics, and compares them to show that the failures experienced by Arab militaries weren't demonstrated by non-Arab militaries operating under the same constraints (e.g. Egyptian and Cuban militaries were both trained as far as possible according to Soviet doctrine, but performed totally differently, and the ways in which Egypt's armies failed were clearly independent to the doctrine/went against that doctrine entirely).

Anyway. Like so many pop-history or pop-science books with a narrative to sell, you really benefit from reading reviews from people who know what they're talking about beforehand, and to keep an eye out for any gaps in the story they're telling you. Here, the reviews will tell you what you should really pick up from the Acknowledgements section at the start; he really doesn't talk to many Arabs for his book on Arab military history. He doesn't really engage with wider literature either, from the region or otherwise. The first big section of the book, on whether Soviet military doctrine was widely responsible for Arab underperformance, is genuinely a completely sound case for why it wasn't; it was in-depth and very well explained. But because Pollack is never interested in presenting competing points of view in the literature, I have no idea whether he's debunking a widespread myth that people take seriously, or if he's shadowboxing against a view that occasional officials will mention but which no one took seriously in the first place.

The narrative also is hung very firmly on the lynchpin of "there's an explanation that's true for all or nearly all Arab militaries". Which, you know. That's an ethnicity, not a Warhammer race. Maybe explanations don't stack up because not every country in the region has problems caused by the same things!

He also is definitely cherry-picking his comparison case studies; there are a lot of wars in the world, and he picks ones that work for his points. That isn't fatal to his arguments, and he's not really hiding it, but it's something to bear in mind.

Lastly, his section on whether Arab underperformance can be put down to economic under-development is... kind of a nothing-burger; I'm not sure he has or even needs a coherent argument. He gives very detailed accounts of the Chadian-Libyan wars and then of the Chinese offensives in the Korean War, which are super interesting vignettes on how the forces of underdeveloped nations can thrash technologically and logistically superior forces; I am not really sure they added anything to the thesis of the book. At some point you are just comparing incredibly different situations and forces, to no real point. "Arab militaries underperform compared to what their available resources should suggest" was the premise of the book that needed explaining; it didn't need 110 pages of argument to prove that it wasn't the explanation.

Anyway, I'm making this post now because the last third of the book focuses on whether Arab militaries underperform due to Arab culture, which... feels like it will want a separate post to talk about after reading, because apparently he's quite keen on this explanation. Even if you ignore that it seems dodgy and unpleasant, it's not an explanation that can really be falsified; it's not easily distinguishable from "Arab militaries are bad because Arab militaries are bad". It's the explanation you would have to fall back on if you didn't have a good explanation, and if there isn't actually a unified explanation you would end up looking pretty silly.

#to be clear#the in-depth strategic and tactical case studies are really good and i've enjoyed them#and they do seem accurate when i've gone off to check#but... this is not an author i am convinced by#armies of sand

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

EL GENEINA, SUDAN—Once crowded, El Geneina’s main street was empty other than a few pedestrians in civilian dress, but with AK-47s slung over their shoulders. As our car drove across West Darfur’s capital in October, I was trying to remember the buildings that, two years ago, were packed with displaced people.

In 2021, local Arab militias, including members of Sudan’s paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), had stormed the nearby camp of Kirinding, which was then hosting some 50,000 civilians. The displaced had found shelter in the town itself, in more than 80 buildings, including schools, ministries, and courts, which they filled with hastily built huts of branches and straw.

The compounds were now deserted, their walls riddled with bullet holes. The displaced had been displaced again, now to neighboring Chad, only 20 miles away. They mostly belong to the Masalit community, the main non-Arab tribe in West Darfur, which once ruled over a powerful precolonial sultanate.

In theory, there was no reason for the Masalit, with few armed forces nor influence in national politics, to be victims of the conflict between the regular army and the RSF, both focusing on control of remote Khartoum. But the war did not spare Darfur, and in El Geneina, it immediately took an ethnic turn. The RSF is largely made of Darfuri Arab militias, the same or similar to those known as the janjaweed that had displaced the non-Arab communities 20 years ago alongside the army.

In El Geneina over the past nine months, whether part of the RSF or acting on their own, Arab fighters had enough arms to settle their accounts with the Masalit. Meanwhile, the army, led by officers from central Sudan, did not seem to care about protecting Darfuri civilians. More than 5,000 Masalit were reportedly killed in June, and the Doctors Without Borders hospital in Adre, Chad, received 1,000 injured people in a week. A retrospective mortality survey conducted in a new camp in Chad, where most refugees came from El Geneina, found that the death rate had multiplied twentyfold between the beginning of the crisis and the survivors’ arrival in Chad, and more than 80 percent of the deaths had been caused by violence.

After that first wave of killings, the new administration of El Geneina, dominated by Arabs and close to the RSF, has been trying to send signs of appeasement. The Masalit are welcome to return, several officials told me. But not in town itself, some added. They accused the disgruntled Masalit youth born in the displaced camps of having formed criminal gangs known as “Colombians.” Some specified that the Masalit should not live less than six miles from El Geneina. But in rural areas, they’re likely to lack essential services (such as water healthcare, and education) and often suffer exploitative practices, such as giving up a share of their harvest in order not to be attacked, as has been common in Darfur in the last 20 years. Under such conditions, their return might not come anytime soon.

As I was driving back to the Chadian border after a week in El Geneina, I saw a truck full of people stopped at a military checkpoint, likely to pay taxes. A couple of weeks later, in early November, about 10,000 people—mostly Masalit civilians—followed them when Ardamata, a Masalit neighborhood on the outskirts of El Geneina where survivors had taken refuge around the army garrison, was evacuated by the regular army forces and attacked by RSF forces and Arab militias as well. Up to 2,000 people were reportedly killed.

Adre, once a small Chadian border post, looked like a small city when I visited in October. Its so-called transit camp hosts more than 120,000 refugees, waiting for the UNHCR to register them and move them to official refugee camps, where the pace of construction struggles to keep up with new arrivals. For now, the refugees have built tents with branches covered with plastic tarpaulins, women’s clothing, and cardboard. It seems almost as if all of El Geneina—at least all Masalit, the majority of the town’s population—have moved to Adre.

Some 120 miles farther north, the border crossing of Tina—with only a dry riverbed to cross between the Sudanese town and its Chadian twin—has also been welcoming refugees daily, many coming from much more remote places than El Geneina. A few miles outside the Chadian town, similar shelters to those in Adre have been built by about 1,500 refugees around an empty concrete fence.

The morning I visited, Abderrahman, who arrived the night before with his family of six other refugees (three women and three children), was erecting a frame made of branches and covering them with plastic sheeting. It would likely be their home for some weeks or months—the time that UNHCR needs to move them to a regular camp, where they will receive some relief—food, water, a better tent, blankets and some medical assistance.

For now, his 20-year-old niece, Manahil, helped him build the shelter in spite of injuries to her shoulder and arm from the bombing that destroyed their house one week before, in Nyala, the capital of South Darfur and Sudan’s second-largest city. But no health care was available in the camp, and refugees had to pay for water delivered from the town on trucks.

Abderrahman then had to walk into Tina to find work while I stayed to speak with Manahil under a tree.

The Darfur war first displaced her family from their village 20 years ago, “when I was still breastfed,” she said, so she has no memory from that first war. The new war is the first that she saw. Her neighborhood was controlled by soldiers from the RSF, who were “entering houses, looting properties, and whipping or killing those resisting,” she told me. “They also kidnapped many girls in our area, until now they haven’t come back.”

The family left town after an army plane bombed their neighborhood. Her three brothers were killed, and six members of the family were injured. They saved the food they could from their kitchen, separated from the rest of the house by a heap of rubble. Across a hole, they could see RSF soldiers looting their clothes in the living room. At the city’s exit, the RSF also took the phones and money of those leaving.

The 300-mile journey to Chad, on a pickup truck with 15 passengers, lasted a week. She couldn’t remember how many checkpoints—controlled by the RSF, unidentified Arab militias, or non-Arab rebel groups—they crossed. Each time, the driver had to pay. Now the family is broke and can’t move further.

“We only want a quiet place here in Chad,” Manahil said. “Unlike the others, we don’t want to migrate.” She pointed at a group of young men, university students who said they were on their way to Europe to resume their interrupted studies.

In the town of Tina itself, I met similar refugees on the road. Mohamed, 27, and Ilham, 20, are a recently married student couple from Khartoum’s middle class. He had studied computer science; she was still in high school but hoping to study the same subject. For them, too, it was their first time seeing fighting; indeed, this war is the first of Sudan’s almost continuous conflicts since independence in 1956 to engulf the capital city, which historically had been a place of refuge for displaced people from the peripheries.

“We realized it would last years, and that we were eating the little money we had,” Mohamed said. In July, they decided to leave with what remained. In Kosti, a city on the Nile to the south of Khartoum, for about $100 each, they joined the monthly convoy to Darfur, escorted by former rebels who were presenting themselves as neutral in the ongoing conflict.

A month after they left Khartoum, they reached Tina. “It was still the good season to take the sea, but we had no more money,” said Mohamed, referring to the journey across the Mediterranean. He began working as a day laborer, cutting grass in the bush for the livestock. In the convoy, most of their fellow passengers had wanted to go to Europe, Mohamed said: “Some already reached Libya, then Tunisia, from where crossing is cheaper. One is now in France. I know the risks, but we will continue. I know that in Libya, there are prisons where they call your parents so that they pay a ransom. I know that at sea, it’s between life and death, but we have no other solution.”

As soon as they have money, the two will travel with Khalil, a pseudonym for a smuggler based in Tina, whose phone number they had been given when they were still in Khartoum. The 37-year-old Sudanese man came to Chad as a refugee himself 20 years ago. In 2014, as there was no work in the camp where he was staying, he began to work as a driver to support his family. Gold had recently been discovered in the borderlands between Chad and Libya, and new routes were opened. Drivers such as Khalil began carrying both miners and migrants, dropping them at the border, from where the latter were quickly entrusted to Libyan smugglers.

Last year, Khalil turned himself from smuggler to migrant, traveling with his jobless younger brother, “who had heard some were crossing the sea and succeeding in life.” They reached the gold mines without enough money to continue. They looked for gold, got 30 grams (worth about $1,500), and continued to Zawiya, a main departure hub on the Libyan coast.

Then they decided that it was better not to risk both their lives at sea. Khalil gave up his share of the gold and returned to Chad. His brother carried on, but his boat was intercepted by the Libyan Coast Guard, which is supported by the European Union in order to decrease flows of migrants toward Europe. He was brought back to Libya, then decided to go to Algeria and, like many Sudanese asylum-seekers, entered Morocco, from where he made three unsuccessful attempts to reach Spain. This year, he managed to get on a plane to Turkey and is now in Greece.

Khalil resumed driving gold-miners and migrants. He said he’s been doing well since the war broke out in Sudan; the number of passengers has increased, and rates have doubled between North Darfur’s capital El Fasher and Tina.

By the end of December 2023, more than 7 million Sudanese had been displaced by the new war. Among them, 1.3 million sought refuge outside Sudan, nearly half of them in Chad and 380,000 in Egypt. Depending on sources, only 5,000 to 14,000 officially made it to Libya, but many more likely crossed the largely unpatrolled Libyan border, including through Chad. New routes opened and older ones were reactivated, from Chad to Libya, as well as to Niger, then Algeria, then Tunisia. Gold mines in the Saharan borderlands acted as hubs; there, migrants could quickly shift from a Chadian truck to a Libyan taxi, or from a Nigerien smuggler to an Algerian one.

Many Sudanese quickly reached Tunisia, and unlike other African migrants, they had no intention to stay and work. They went directly to Sfax, the main departure hub along the Mediterranean coast—only 117 miles from the small Italian island of Lampedusa—and camped in city parks.

The local population was not so happy. It was alleged that on July 3, a Sudanese refugee (though other sources alleged it was two Cameroonians) killed a Tunisian man. The incident became the trigger for local mobs that rounded up Black Africans in an attempt to expel them from Tunisia’s second city. The police, pretending to offer protection, put the migrants into vehicles amid racist shouting by locals, before deporting them to the Libyan border. As many as 1,200 people were stranded in the no man’s land between Tunisian and Libyan forces for a week, and some remained for more than a month.

It became a deadlock, with Tunisian and Libyan forces playing ping-pong with the migrants before eventually striking a deal to share them between the two countries. There were reports of nearly 30 deaths, including from violence and thirst. At first, the only water available was from the sea.

The European Union remained astoundingly silent during the waves of violence against Black Africans in Tunisia. While they were taking place, the European Commission and some members states (chiefly Italy and the Netherlands) struck a cooperation deal with Tunisia, including a migration component described by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen as a “blueprint” for future similar deals. It is mostly aimed at paying Tunisia more than $115 million to tighten its borders to prevent migrants leaving by sea and to accept the “readmission” of those Tunisians who succeed in crossing. (In 2023, more than 60 percent of sea arrivals to Italy had come from Tunisia, rather than Libya—as had been common in the past).

I visited southern Tunisia in August. The UNHCR noted a sharp increase around then of Sudanese registration in the country, as well as of Sudanese asylum-seekers crossing from Tunisia to Italy. During a morning of medical consultations I attended at a UNHCR center, of 20 patients, 19 were Sudanese. Six had left Sudan after the war began, including three who had reached Tunisia in about a month. Six had foot injuries from having walked too much.

Among them, Issa, who preferred not to use his real name, had left his displaced camp near El Fasher 40 days before. He said he had been pushed back to Libya three times by Tunisian border guards and had then gone from Libya to Algeria before walking 450 miles to the Tunisian coast. Among those who had spent longer on the road, Abdallah had left Khartoum in 2017, spending seven years in Libya and only coming to Tunisia after 12 failed attempts to cross the sea, generally followed by stays in Libyan detention centers. “Each time, I had to pay a bribe, or to escape,” he said.

Ismail, from Nyala, decided to go to Libya even though his father, who made the journey first, was jailed for five months and tortured for ransom until he died. The family did not have enough money to get him released, even after selling their house. “I left Sudan in 2021. I didn’t have enough information on Libya but knew my father’s story. I had to be ready for anything,” he said.

He failed to cross the sea and went on to Morocco, where he tried more than 10 times to climb the walls surrounding the Spanish enclave of Ceuta. “My life was like that of a gazelle running from a lion. I tried to reach Europe from Libya and failed. From Morocco, I failed too. Then I found lots of migrants were coming to Tunisia. Everywhere there’s just a small hole to reach Europe, migrants go through.” A month later, he messaged me after arriving in Lampedusa.

In the past, most Sudanese used to try to make a living in Libya. But the increasing violence in the country has pushed more to cross the sea. The same thing took place this year in Tunisia, in spite of increasing interceptions by the coast guard.

There is a bitter irony in seeing Europe again panicked by growing migrant flows, including from Sudan, transiting through its new model partner, Tunisia. Indeed, in 2016, Sudan itself had become a main EU partner on migration, with the capital hosting the headquarters of the EU’s regional “Khartoum Process.”

The EU was then accused of cooperating with a regime whose president, Omar al-Bashir, was indicted by the International Criminal Court for genocide; and with his then-trusted, RSF, which he had specifically tasked to control migration, and whose leader, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo—also known as Hemeti—repeatedly bragged that he was arresting migrants on behalf of Europe.

The EU only admitted to working with the police, which also included a paramilitary component involved in crimes in Darfur—namely, the Central Reserve Police, a force that’s now under U.S. sanctions for killing pro-democracy protesters in Khartoum in 2022.

Whether regular or not, some of the Sudanese forces that benefited from Europe’s financial (or at least political) support to fight migration are now fighting each other, and provoking new refugee flows.

Sudanese refugees know they have high chances of success at getting asylum in Europe and North America, in particular since the latest war started. The United States, France, and other nations see them as perfectly legitimate refugees. In August, the U.S. government extended its temporary protected status for Ukrainian and Sudanese nationals through 2025.

Since July, the French asylum appeal court also granted similar temporary protection status to several Sudanese refugees from Khartoum and Darfur whose asylum claims had first been rejected, arguing their regions of origin were in “a situation of blind violence of exceptional intensity”—thus creating legal precedents for anyone from the same regions to get protection, at least temporarily.

Maybe because its decisions are too generous in the eyes of the current government, that court is now under attack from the interior minister, whose new law on immigration (hardened and approved on Dec. 19) is set to reduce typical asylum appeal panels of three judges—one representing the UNHCR—to only one. It also reintroduced into French law an infraction known as “illegal stay,” while the new European Commission Pact on Migration and Asylum, agreed upon the same night, will allow detention of some asylum-seekers at the EU’s external borders. UNHCR head Filippo Grandi congratulated the EU, tweeting his readiness to support.

The temporary protection status is based on older, more generous EU laws, most notably a 2001 directive allowing immediate protection, rather than detention, in case of mass displacement, which was enforced for the first time in the case of Ukraine in March 2022. Together with measures facilitating Ukrainians’ entry and circulation within Europe, this allowed more than 4 million Ukrainians to receive immediate protection in the EU. But there seems to be little appetite in Europe to expand the Ukrainian exception to other war-torn countries.

Sudanese migrants still have to reach Europe by themselves and face obstacles—across the Sahara, the Mediterranean, or the Alps between Italy and France—that are not only natural, but also caused by European policies. The EU has been gradually building a network of both physical and legal walls south of the Mediterranean, harming both economic migrants and political refugees, violating both the U.N.’s 1990 convention on the rights of migrant workers and its 1951 Geneva refugee convention, and using all kinds of excuses—from COVID-19 to the war in Ukraine—to make exceptional measures permanent—in effect, as Foreign Policy pointed out at the height of COVID-19, the end of asylum as a practical possibility. Now the new EU pact uses the vague concept of “crisis” to allow members states to ignore their asylum obligations.

Europe’s reaction to the new Sudanese war was not particularly vocal other than recognizing that it was also a refugee crisis, merging with Europe’s existing migration crisis. Calling for much-needed funding for the new refugees, the U.N., to which the EU is a major donor, did not hesitate to play on Europe’s fears; the reasoning being that Europe’s interest was to keep the refugees in the camps in Chad, and thus fund relief or face increasing flows.

But once in Chad, the newcomers quickly realized that those who preceded them 20 years before had suffered from the fickleness of the aid sector, which is always moving from one crisis to the next. When rations had decreased, many had decided to travel to find work (from gold-mining in the Sahara to cheap labor industries in Europe) and send remittances to their families in the camps.

UNHCR resettlement processes remained extremely limited because of the lack of slots in Europe and North America. Everywhere I went, in Chad, Libya, or Tunisia, I heard of a few cases of Sudanese resettled to the United States or Canada—but some had waited 20 years, and others were still waiting.

UNHCR admits being compelled to look for “durable solutions” within those three African countries, even though they are neither durable, nor solutions. In Libya as in Tunisia, even refugees registered by UNHCR have been arrested—including by being rounded up when they were camping or protesting in front of the U.N. agency’s offices—before being detained or deported.

Among those who travelled to Tina with Mohamed, the computer science student, some registered as refugees in Chad in the hope that they’d be resettled, then changed their minds and are now in Libya or Tunisia.

Khalil, the smuggler, knows he won’t be short of clients: “Some applied to resettlement since 2003 and never left,” he told me. “Legal migration is too difficult.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Guelta d'Archei Lake in the Chadian Sahara.

A guelta (Arabic: قلتة, also qalta or galta; Tamazight: agelmam) is a pocket of water that forms in drainage canals or wadis (river valleys) in the Sahara.

Ennedi. Guelta de Archei. Desde el mirador, escandio

143K notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 3.20 (after 1950)

1951 – Fujiyoshida, a city located in Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan, in the center of the Japanese main island of Honshū is founded. 1952 – The US Senate ratifies the Security Treaty Between the United States and Japan. 1956 – Tunisia gains independence from France. 1964 – The precursor of the European Space Agency, ESRO (European Space Research Organisation) is established per an agreement signed on June 14, 1962. 1969 – A United Arab airlines (now Egyptair) Ilyushin Il-18 crashes at Aswan international Airport, killing 100 people. 1972 – The Troubles: The first car bombing by the Provisional IRA in Belfast kills seven people and injures 148 others in Northern Ireland. 1985 – Libby Riddles becomes the first woman to win the 1,135-mile Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. 1987 – The Food and Drug Administration approves the anti-AIDS drug, AZT. 1988 – Eritrean War of Independence: Having defeated the Nadew Command, the Eritrean People's Liberation Front enters the town of Afabet, victoriously concluding the Battle of Afabet. 1990 – Ferdinand Marcos's widow, Imelda Marcos, goes on trial for bribery, embezzlement, and racketeering. 1991 – Khaleda Zia takes oath as the first female Prime Minister of Bangladesh. 1993 – The Troubles: A Provisional IRA bomb kills two children in Warrington, England. It leads to mass protests in both Britain and Ireland. 1995 – The Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo carries out a sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway, killing 13 and wounding over 6,200 people. 1999 – Legoland California, the first Legoland outside of Europe, opens in Carlsbad, California, US. 2000 – Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, a former Black Panther once known as H. Rap Brown, is captured after murdering Georgia sheriff's deputy Ricky Kinchen and critically wounding Deputy Aldranon English. 2003 – Iraq War: The United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Poland begin an invasion of Iraq. 2006 – Over 150 Chadian soldiers are killed in eastern Chad by members of the rebel UFDC. The rebel movement sought to overthrow Chadian president Idriss Déby. 2010 – Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland begins eruptions that would last for three months, heavily disrupting air travel in Europe. 2012 – At least 52 people are killed and more than 250 injured in a wave of terror attacks across ten cities in Iraq. 2014 – Four suspected Taliban members attack the Kabul Serena Hotel, killing at least nine people. 2015 – A Solar eclipse, equinox, and a supermoon all occur on the same day. 2015 – Syrian civil war: The Siege of Kobanî is broken by the People's Protection Units (YPG) and Free Syrian Army (FSA), marking a turning point in the Rojava–Islamist conflict. 2019 – Kassym-Jomart Tokayev is sworn in as acting president of Kazakhstan, following the resignation of long-time president Nursultan Nazarbayev.

0 notes

Text

The third war was the Libyan invasion of Chad:

The last of the three wars is the Libyan invasion of Chad, which ended with the Toyota War. This war also points to a key difference between the real Muammar Gaddafi and the person that posterity and useful idiots try to make him into being.

Namely that instead of some pan-Africanist anti-racist Gaddafi was a fascist Arab nationalist who believed Arabs were culturally and morally superior to Black Africans and waged the war first for a narrow strip of land and then to expand his power as far into Chad as he could reach.....and then it turned out that things didn't go very well because the Chadians improvised and routed him at the Battle of Fada, exposing the hollowness of Gaddafi the man versus that of Gaddafi the myth.

#lightdancer comments on history#black history month#african history#military history#libyan-chadian war#toyota war

0 notes

Text

Sicilian heritage

Going to Rome this year has me interested in getting a better grip on Italian history. Since my heritage on my mom's side is Sicilian, I thought I'd get a bead on Sicilian history too, though that isn't my focus right now.

A basic history is that in the area of Sicily where my family is from, there were an initial people called the Elymoi. From somewhere 1000-750 BC, the Carthaginians, a Phoenician people that had established an outpost in modern Tunisia, colonized the area of Trapani, on the far west point of Sicily. There were a series of wars fought with the Greeks for control of the island until the mid 200's BC when the Romans made Sicily a province of Rome. The Vandals and Ostrogoths ruled from 469-535, then the Byzantine (Greek) empire took over Sicily until 826. A Muslim emirate from Tunisia invaded Sicily in 826 and by 962, Sicily became the emirate of Sicily. The Normans, originally from Scandinavia, but coming through France, conquered Sicily by 1091.

In 1282, Peter of Aragon (Spain) takes over Sicily. From 1400-1600, there is a wave of Greek immigrants that flood the island due to Greeks fleeing the Ottoman invasions. In 1720, Sicily is ruled by the Austrian Habsburg dynasty, but the Bourbon Spaniard Charles VII takes over again in 1735. Garibaldi invaded and captured Sicily in 1860, when it was unified with Italy as the Kingdom of Italy.

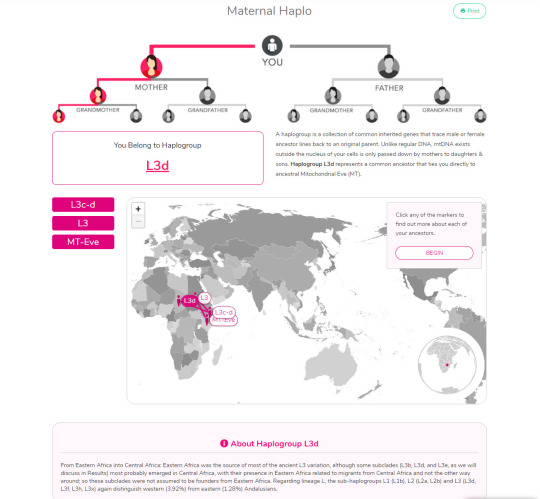

So being Sicilian could mean Elymoi, Carthaginian, Greek, Roman, German, Arab, Norman, Spanish, Austrian or Italian blood. This is where I was interested in the mtDNA test that 23 and me offered.

The maternal DNA test was what interested me since the Sicilian heritage was from my mom's side, and this traces back through mom, my maternal grandmother, and then her mom, etc. The farthest I can go back on that side is my nonna's mom, whose maiden name was Rosa Sinatra, born in 1886 in Custonaci, Sicily.

The results came back with a haplogroup of L3d, which is from central to north-east Africa.

Looking up haplogroup L3 on wikipedia, it shows that it spread from east Africa in the upper paleolithic (50k-12k years ago) to Central Africa with some subclades spreading to East Africa with the Bantu migration. It is found among the Fulani, Chadians, Ethiopians, Akan, Mozambique, Yemeni, Egyptians and Berbers.

The Berbers were located on the north and north-west coast of Africa along the Mediterranean and some of that area was ruled by Carthage. Egypt was also a Roman province from before Christ. So it's possible that the bloodline has been in Sicily since those early times.

But only 2% of the Sicilian population has the haplogroup type L, so it doesn't seem likely that my ancestry is from some ancient line of peoples that had been there for millennia. That would probably mean some more recent migration, of which, as can be seen through the history, there has been a LOT. I suppose the most likely choice would be during the Caliphate years. The Muslims who had come from north Africa were perhaps more easily expelled when the island was taken by the Spaniards after the Normans, which would have meant there were relatively few of them left. Or perhaps the blood line came up in one of the more recent migrations that happened in the ensuing centuries. Since the L3 line isn't common, I'm assuming it wasn't part of any 'wave' of immigration, unless it was the Arabs that were in Sicily from 900-1300.

However, since the main location of L3 is found in central Africa, it's possible there was some slave trading involved, and an ancestor ended up in Sicily as part of the slave trade. This paper looks at the Arab trans-saharan slave trade: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2875235/

This trade of black slaves began circa 650 AD. The estimate was that roughly 4.8 million slaves were taken between 650-1600 AD. The site shows the trans-saharan slave trade routes.

The paper mentions that males were sought for service functions as well as soldiers. But the bulk of the trade was in females, for domestic service, entertainers and/or concubines. The figure 6 maps (on the site, but not reposted here) show the particular L3d group being on the far west and north-west coasts of Africa, (modern Senegal, Western Sahara, Mauritania, Algeria and Morrocco) and also in southern Arabia, Turkey and Jordan, then further into Iran

Another author I found wrote this:

"For the span of one hundred years, early modern Sicily became an export market of a trans-Saharan slave trade route that originated in Borno, West Africa. In turn, Black men, women, and children became a significant portion of the enslaved populations living in Sicily. This project focuses on the long-standing communities of West Africans in sixteenth-century Palermo. It examines census, legal, and ecclesiastical records for indicators of their mobility both within Sicilian society and the wider Mediterranean. Enslaved and freed Black Africans' experiences reveal the complex ways in which local practices of slavery interplayed with Mediterranean constructs of religion, race, and empire."

This leads me to suspect that one of the ancestors was a female slave brought up from central Africa through the slave trade. Maybe.

I'm certain the truth of the story is lost to history by now, but it is interesting to me. I hadn't expected to see central African as the maternal haplogroup, but there it is.

0 notes

Text

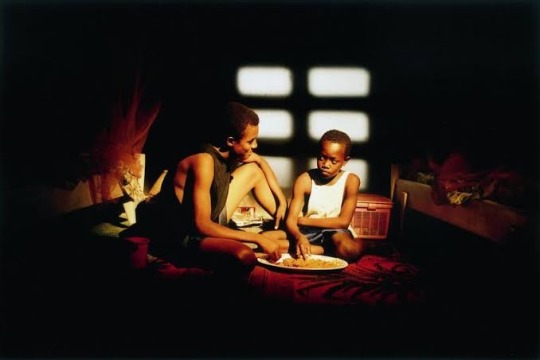

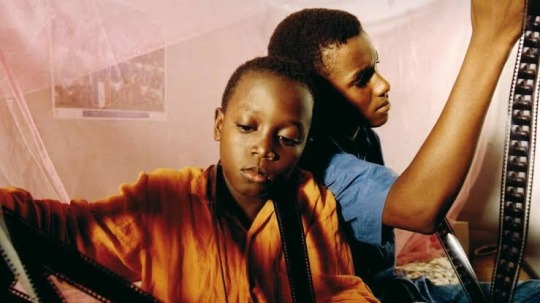

Abouna - dir. Mahamat Saleh Haroun - (2002)

#movie#film#chad#chadian movie#chadian film#Mahamat Saleh Haroun#Zara Haroun#Mounira Khalil#Hamza Moctar Aguid#Ahidjo Mahamat Moussa#chadian arabic#french#our father#poetic#drama#coming of age#young adult#foreign film

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arabic dialects

Arabic is spoken by around 369.8 million people and is the official language in 24 countries, in a geographical area that stretches from Morocco to Oman.

It is subdivided into three main varieties: Classical Arabic, Modern Standard Arabic, and spoken Arabic. Classical Arabic, also known as Quranic Arabic, is the written language of the Quran. It is no longer a spoken language and is used only for religious purposes.

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), or fusha, derives from Classical Arabic and is the foundation of all dialects. It is used in formal meetings, politics, media, and books.

Spoken Arabic refers to the Arabic dialects used in everyday life for daily tasks and to communicate informally with other people. They do not have a standardized written form.

Compared to MSA, it has a simpler grammatical structure and a more casual vocabulary and style. Some letters are pronounced differently.

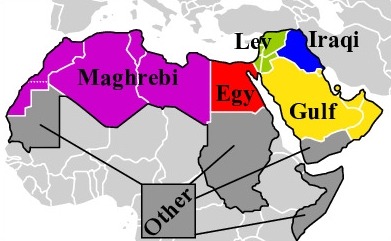

Dialects vary considerably from region and region and are not always mutually intelligible. There are 25 of them, classified into five groups: Maghrebi, Egyptic, Mesopotamian, Levantine, and Peninsular.

Two main groups were formerly distinguished: Mashriqi (eastern), which includes Peninsular, Mesopotamian, Levant, and Egyptic Arabic, and Maghrebi (western) dialects. Mutual intelligibility is high within each of the groups, while intelligibility between them is asymmetric: Maghrebi speakers are more likely to understand Mashriqi than vice versa.

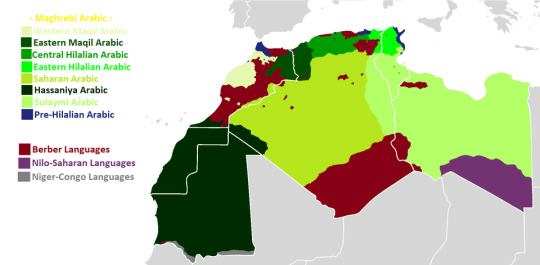

Maghrebi Arabic

Maghrebi Arabic includes Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Libyan, Hassaniya, and Saharan. These varieties have been influenced by Punic and the Amazigh and Romance languages. They are collectively known as Darija, also written as Derija or Derja.

Darija has over 100 million speakers across Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Mauritania. It is known to sound very fast and to be difficult to understand for other Arabic speakers. One of its most remarkable characteristics is the integration of English and French words in technical fields.

Maghrebi dialects use n- as the first-person singular prefix on verbs instead of a-. In Moroccan Arabic, short vowels are weakened, and double consonants are never simplified.

Egyptic

Egyptic Arabic comprises Sudanese, Juba, Egyptian, Sa’idi, and Chadian. Sudanese and Juba Arabic are influenced by the Nubian languages, while the rest have been shaped by Coptic.

They are spoken in Sudan, South Sudan, Egypt, and Chad. Egyptian Arabic alone is spoken by 83 million people and is the most widely spoken dialect. Its grammar is significantly different from that of MSA, and it has 10 vowels instead of six.

Sudanese Arabic has 32 million speakers and has some unique characteristics. For example, the letter ج is pronounced like “g” instead of “sh” like in other Arabic dialects.

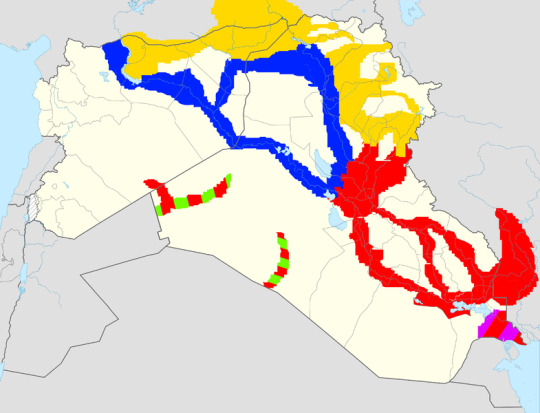

Mesopotamian

Mesopotamian Arabic includes North Mesopotamian, Cypriot Maronite, Iraqi, and South Mesopotamian. It is spoken by almost 50 million people in Iraq, Iran, Syria, Turkey, Cyprus, Israel, and Kuwait.

They have been influenced by Turkish, Iranian languages, and Mesopotamian languages like Akkadian, Aramaic, and Sumerian.

Iraqi Arabic has more than 40 million speakers. It has more consonants and long vowels than MSA. Furthermore, words end in consonants rather than vowels.

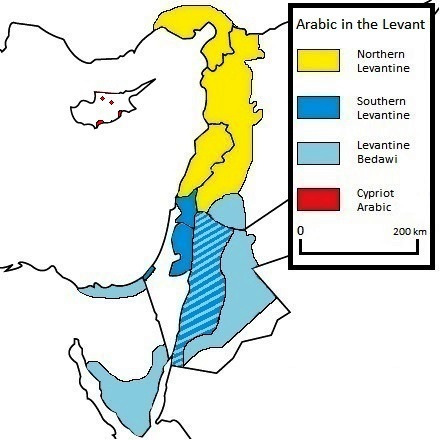

Levantine

Levantine Arabic can be further divided into North and South. North Levantine, spoken by 25 million, includes Syrian and Lebanese, and South Levantine, with 12 million speakers, comprises Palestinian and Jordanian. Northwest Arabian Arabic, or Bedawi, forms its own group and has more than 2 million speakers.

Levantine varieties are influenced by the Canaanite and Western Aramaic languages and to a lesser extent by Ancient Egyptian, Greek, Persian, Turkish.

It has unique phonological, lexical, and grammatical features. For example, personal pronouns can take up to 12 different forms depending on the dialect.

Lebanese Arabic has a simpler morphology than MSA, but its syllables are more complex. Palestinian Arabic is the closest dialect to Modern Standard Arabic, but still differs in morphology.

Peninsular

Peninsular Arabic includes the following dialects: Najdi, Gulf, Bahrani, Hejazi, Yemeni, Omani, Dhofari, Shihhi, and Bareqi. It has more than 40 million speakers. Some varieties were influenced by the extinct South Arabian languages.

It is mainly spoken in the Arabian Peninsula and its neighboring regions. Peninsular Arabic has fewer loanwords than other dialects. Gulf Arabic differs in phonology and lexicon from MSA. It is mostly mutually intelligible with Egyptian Arabic, but unlike it, pronounces ج like “j”.

Yemeni Arabic, on the other hand, retains many classical features that are not used in other parts of the Arabic-speaking world, such as the -k suffix.

Here is a comparison of how interrogative pronouns are said in each dialect:

(what - where - when - how - why - who)

MSA: maatha - ayna - mataa - kayf - limaatha - man

Egyptian: eih - feen - imta - izzayy - leih - miin

Levantine: shoo - wayn - imta - keef - leesh - meen

Maghrebi: shnoo - feen - foquash - kifash - 3lash - shkoon

Peninsular: maa aysh - ayn - mata - layf - limih - man

286 notes

·

View notes

Text

Languages of Chad:

The main languages of Chad are Arabic and French. Few Chadians other than the educated and well-travelled speak literary Arabic; however, a dialect of Arabic known as "Chadian Arabic" is much more widely spoken and is the closest thing the country has to a trade language. Chadian Arabic is significantly different from literary Arabic, but similar to the dialects of Sudan and Egypt. Literary Arabic speakers can typically understand Chadian Arabic but the reverse is not true. Over one hundred indigenous languages are also spoken.

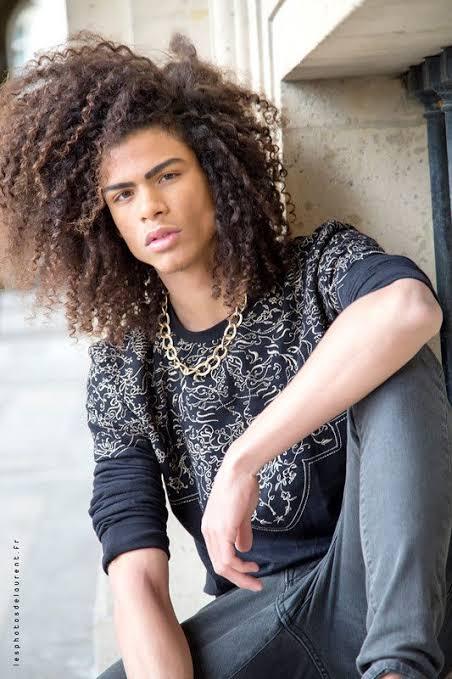

Map of Chad. Chadian children.

0 notes

Text

HC: The Lee-Thorne Children

Because TRH tried to fuck Hana over by pretending she couldn't have kids, and I was very strongly for Hanara by then, I'd decided I was going to take my revenge by giving the couple FIVE children! Three of them Hana gave birth to, and two (who are twins) came from Kiara.

In my HC, Hana basically loves the process of pregnancy (not so much childbirth - but she does feel a lot more connected and involved with the process), and Kiara not as much, therefore Hana does get the urge to have kids more than once and Kiara had a great birthing experience but wasn't really going to actively look for another chance to birth kids. All of the kids came from anonymous donors so the ethnicities are listed along with their names.

Kiara and Hana both have different origins and different places they view as home...so their kids' names are meant to honour those places.

Here's a short list of the five kids Hanara have in my P&T-verse, and a few hcs I currently have about them (still developing!):

Chaima:

• She was named so because one of the meanings for this name in Arabic is "the one with a beauty spot", which she definitely has above her chin, towards the left. Her ethnicity is Chinese, Parsi and Jamaican.

• As the firstborn, Chaima was doted on, but Hana also worried she was falling into some of her mother's parenting patterns while caring for her. Kiara, having actually experienced a healthier family environment, provides Hana with a safe space to channel her more negative thoughts and emotions.

• Kiara also identified early on that Chaima struggled with focus, and realized visual stimuli worked best. When she pointed this out to Hana the two worked on ensuring Chaima knew how to channel her nervous, easily-distractible into something that could help her achieve goals she may be comfortable setting.

• Chaima is very quiet, and loves reading. While her mothers help curate her reading material, as time passes they try to help her figure out what she likes best. Chaima never has to hide a book from her mothers - if something she has is found with objectionable content, the two decide how to broach on the subject in alternative ways with her, rather than guilting her out of reading it. She is very active in Castel's LGBTQ scene and is involved in a lot of their organizations.

Fleur:

• Fleur is one of the two children (twins) Kiara carried. She was named (obviously) as an affectionate little nudge to Hana, who loves flowers. Her ethnicity is Moroccan, French, Polish and Chadian among others. The age gap between Chaima and the twins are 3 years.

• As a child Fleur loved the idea of treasure hunts. Perhaps she may have taken that idea to extremes 😅 You would often find her picking random stuff off the road claiming it was for her treasure chest. This was something Kiara encouraged, having been in that phase in her childhood too - until she was confronted with the sheer amount of stickers and bottlecaps and used bills that wound up in her nice fancy velvet lined chest! 😂😂

• She's very sensitive and emotional, and when dealing with an off-mood likes to stay away from everyone else and deal with her emotions and discomfort in peace. Usually around that time her twin Guillaume is the only one she feels comfortable around.

• Kiara did some amount of local modelling when she was younger but was never interested in pursuing the same as a career or even continuing casually after she reached adulthood. Fleur is very different in this regard - she loves modelling and fashion and walked many international ramps and uses her career to promote causes she is passionate about.

Guillaume:

• He is Fleur's twin, and was named after Guillaume Appollinaire, Kiara's favourite poet of all time. His ethnicity is Moroccan, French, Polish and Chadian among others.

• He is the most musically inclined of Hanara's children, and is particularly talented with the harp. Hana by this time started to secretly do film score music compositions and was very conscious esp of ensuring he didn't feel forced into anything, esp in public.

• Guillaume however loves performance as much as he loves the art and initially misunderstands his Mama Hana as not being very impressed with his talent, however Kiki does fill him in on where Hana's overcautiousness stems from (with Hana's permission) because she sees the gap it's creating between them. They become closer than ever after that and I hc Guillaume inspires Hana to eventually come public when all the kids are grown. (A portion of this hc was borrowed from one of @thecapturedafrique's hcs too, credit to her!! 💖💖💖)

• Because of his interest in music he also keeps closer ties to his cousins in Morocco than the rest of the kids, considering his great-grandfather was a musician from the Gnawa community in Fes. He also keeps in touch often with his great-aunt Xīngxià, who mentored Hana.

• Additional hc: both Fleur and Guillaume team up to produce a line of haircare products, specifically for people with 4c and 4d curly hair.

Táo huā:

• Hana has the urge to have another child after Chaima is 7 and the twins are 4. So there is an 8- and 5-year age gap between them and Táo huā. Her name means ""peach blossom", which is a good luck symbol esp for love and romance in Chinese culture, but one definite inspiration for Hana was the same Shanghai jazz song that inspired her name (Méi huā). The song compares the plum blossom to the peach one in the lyrics in a way that extols the former's resilience and steadfastness, but Hana's takeaway is that she doesn't want her children to have to be forced to learn resilience. She also did it as a dedication to her cousin Chūntáo (whose name means "spring peach"), who has long been seen as the family's "black sheep". Táo huā's ethnicity is Chinese, Parsi, Hawaiian, and Welsh.

• Most people think Táo huā resembles her Mama Hana the most (they don't really, but it's the popular opinion) so they're usually in for a surprise when they find her to be the most chaotic of the Lee-Thorne clan. She's cheerful and impulsive and loves pranks.

• Kiara loves all her children but feels a special kind of joy seeing Táo huā in her element because she is so unlike herself and Hana, her own parents, and most of the kids. While Táo huā occasionally does get into a little bit of trouble occasionally, Kiara is firm with her but internally feels a bit of joy that they've managed to keep an environment where a spirited individual like her can feel safe and loved. Normally this wouldn't be as big a deal to Kiara - family is family and you need to feel safest with them - but seeing the effects of Hana's parenting on her self-esteem does ensure that Kiara doesn't take that kind of freedom for granted.

• Hana's relationship with Táo huā is internally a bit more complicated. There's some of herself she sees in this child, but in her she also sometimes sees what she could have become if her parents weren't as controlling. Most times she's able to process her feelings about her kids and her parenting with Kiara, but a lot of these feelings are even harder to articulate in Táo huā's case. There is an incident where Táo huā impulsively colours her hair pink as a teen, and Hana struggles to process coz she once wanted to do that as a child. Thanks to Kiara's support and role in helping Hana process - both Chaima and Táo huā have mostly very positive memories of their mother during their childhood.

Jehangir aka Zachariah:

• The youngest and final child. Hana had him when Chaima was 9, the twins were 7 and Táo huā was 2. He's the only kid in the bunch whose names to honour both his mothers' Houses are publicly know. His official name, Jehangir ("Conqueror of the World" and also the name of a Mughal Emperor) is a nod to his grandmother Lorelai's family in Bethulia, who are of Parsi (Indian Zoroastrian) origin. His name at home, Zachariah, is part of a family tradition among the Thornes where they name at least one son after a Hebrew/Biblical/Islamic prophet. His uncle Ezekiel was also part of a similar tradition. Jehangir/Zachariah's ethnicity is Chinese, Parsi and Singaporean.

• The gourmand of the family. While the entire clan is known for their impeccable and eclectic knowledge of world cuisines, Jehangir is the only one who focuses on it specifically. He is especially inspired by a close friend of his mothers', King Liam, who trusted Mama Kiki with hosting Cordonia's first International Gastrodiplomacy Summit and whose own mother did a thesis on Gastrodiplomacy.

• Jehangir eventually hosts his own food and travel shows as an adult. His show, Culinary Trails Across Cordonia, put the country on the world map for its excellent and interesting showcase of the culinary diversity in Cordonia. It explored places that most documentaries and shows didn't explore, seeing as many of them focused more on Lythikos, Fydelia, Portavira and the Capitol.

• Kiara's friendship with Liam had a lot to do with their mothers' own bond, and just before he got married she managed to find a copy of one of the first drafts of his mother's thesis in the attic. She gave it to him as a wedding gift. When Jehangir was starting out with this interest as an adult, Liam gave it to him as a gift, and as an affectionate reminder to Kiki of how their friendship began.

(Faceclaims:

Chaima - Lauren N. Hardie

Fleur - Anais Mali

Guillaume - Cohe Paroix

Táo huā - Laura Elizabeth Woo

Jehangir/Zachariah - Nathan Hartono)

#kiara theron#hana lee#kiaratheronappreciationweek#KTAW#the royal romance#the royal heir#the royal finale#KTAW Day 2#KTAW Day 2: Family#long post

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Sorry if this is too specific, but could I please get some suggestions for a female fc in her 20s with brightly colored hair and a good amount of resources?

Anna Lambe (Trickster) Inuit - bisexual.

Kawennáhere Devery Jacobs (The Sun at Midnight) Mohawk - not straight but hasn’t labelled her sexuality.

Sofia Carson (Descendants) Colombian – including Arab [Syrian, Lebanese, Palestinian], Spanish, possibly English, possibly other.

China Anne McClain (Descendants) African-American.

Muskkaan Jaferi (Mismatched) Indian.

Keke Palmer (Scream) African-American.

Amanda Arcuri (Degrassi) Argentinian and Italian.

Nikki Gould (Degrassi) Miꞌkmaq and Italian.

Park Gyu-young (Sweet Home) Korean.

Shona McGarty (EastEnders)

Chelsea Zhang (Titans) Chinese.

Mary Elizabeth Winstead (Scott Pilgrim vs. the World)

Emma Dumont (The Gifted)

Linnea Berthelsen (Stranger Things) Indian.

Tati Gabrielle (Chilling Adventures of Sabrina) African-American / Korean.

Taylor Dearden (Sweet/Vicious)

Lin Min-Chen (1990) Chinese-Malaysian.

Loey Lane (1993)

Na Whan (1993) Korean.

Kim Miso (1994) Korean.

Pat Chayanit Chansangavej (1995) Thai.

Fernanda Ly (1995) Chinese-Vietnamese.

Cheris Lee (1996) Singaporean.

Shannon Taylor (1997) - has alopecia.

Shanudrie Priyasad (1997) Sri Lankan.

Ziruza Tasmagambetova (1997) Kazakh.

Arlo Parks (2000) Chadian and French-Nigerian - bisexual.

another ask for 28-35 years olds with bright hair including more suggestions!

If you send this to other people they might suggest Vanessa Morgan but she’s playing the role of a Native character so please be mindful of that as I don’t personally suggest her!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 3.14 (after 1930)

1931 – Alam Ara, India's first talking film, is released. 1939 – Slovakia declares independence under German pressure. 1942 – Anne Miller becomes the first American patient to be treated with penicillin, under the care of Orvan Hess and John Bumstead. 1943 – The Holocaust: The liquidation of the Kraków Ghetto is completed. 1945 – The R.A.F. drop the Grand Slam bomb in action for the first time, on a railway viaduct near Bielefeld, Germany. 1951 – Korean War: United Nations troops recapture Seoul for the second time. 1961 – A USAF B-52 bomber carrying nuclear weapons crashes near Yuba City, California. 1964 – Jack Ruby is convicted of killing Lee Harvey Oswald, the assumed assassin of John F. Kennedy. 1967 – The body of U.S. President John F. Kennedy is moved to a permanent burial place at Arlington National Cemetery. 1972 – Sterling Airways Flight 296 crashes near Kalba, United Arab Emirates while on approach to Dubai International Airport, killing 112 people. 1978 – The Israel Defense Forces launch Operation Litani, a seven-day campaign to invade and occupy southern Lebanon. 1979 – Alia Royal Jordanian Flight 600 crashes at Doha International Airport, killing 45 people. 1980 – LOT Polish Airlines Flight 007 crashes during final approach near Warsaw, Poland, killing 87 people, including a 14-man American boxing team. 1982 – The South African government bombs the headquarters of the African National Congress in London. 1988 – In the Johnson South Reef Skirmish Chinese forces defeat Vietnamese forces in an altercation over control of one of the Spratly Islands. 1995 – Norman Thagard becomes the first American astronaut to ride to space on board a Russian launch vehicle. 2006 – The 2006 Chadian coup d'état attempt ends in failure. 2006 – Operation Bringing Home the Goods: Israeli troops raid an American-supervised Palestinian prison in Jericho to capture six Palestinian prisoners, including PFLP chief Ahmad Sa'adat. 2007 – The Nandigram violence in Nandigram, West Bengal, results in the deaths of at least 14 people. 2008 – A series of riots, protests, and demonstrations erupt in Lhasa and subsequently spread elsewhere in Tibet. 2017 – A naming ceremony for the chemical element nihonium takes place in Tokyo, with then Crown Prince Naruhito in attendance. 2019 – Cyclone Idai makes landfall near Beira, Mozambique, causing devastating floods and over 1,000 deaths. 2021 – Burmese security forces kill at least 65 civilians in the Hlaingthaya massacre.

0 notes

Text

Architecture highlights from northeast Africa include projects from Sudan and Somalia

In the fourth part of our collaboration with Dom Publishers, the editors of the Sub-Saharan Africa Architectural Guide pick their architectural highlights from countries in northeast Africa.

With contributions from nearly 350 authors, the Sub-Saharan Africa Architectural Guide aims to be a comprehensive guide to architecture in the African countries that lie south of the Sahara.

Sub-Saharan Africa Architectural Guide is a seven-volume book focused on architecture in Africa

The fourth volume of the seven-volume publication is named Eastern Africa from the Sahel to the Horn of Africa and focuses on the architecture of Chad, Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti, Ethiopia and Somalia.

Read on for picks from the region selected by the book's editors Philipp Meuser and Adil Dalbai:

Photo is by Luca Compri

Chad N'Djamena Grand Hotel, N'Djamena, by TAU ⁄ Roberto Sechi, Luca Compri

The N'Djamena Grand Hotel is part of an architectural complex designed to host big political events. It is situated in N'Djamena city centre, overlooking the Chari River. The building is characterised by its palace-like structure and its rectangular shape.

The facade of this hotel building clearly shows the Arabic influence on Chadian architecture. The repetitive patterns of the facade give the building a grandeur that many modern mosques can hardly match.

In total, it has eight levels. On the ground floor is the lobby (a double-height space), the restaurant, the cafeteria, the meeting room, and all of the administrative offices. The 187 bedrooms cover the remaining floors and have varying sizes: the higher the floor number, the bigger and more luxurious the rooms become, ending with the deluxe executive suites on the top floor.

Photo is by Ibrahim Z Bahreldin

Sudan Al-Nilein Mosque, Morada, Gamar Eldowla Abdelgadir

Al-Nilein Mosque stands near the confluence of the two Niles, facing west onto the White Nile. It was a graduation project by Gamar Eldowla Abdelgadir, one of the University of Khartoum's architecture students during the mid-1970s.

The project comprises three components: the mosque, the library, and the space for communal activities. Shaped like a giant shell, the main building's geodesic dome shelters a large column-less room, where the walls are continuously connected through the curved ceiling.

The form of this mosque almost resembles a coconut macaroon – even if strictly devout Muslims don't like to hear that. But from an architectural point of view, it is a true masterpiece.

Photo is by Hanming Huang

South Sudan Juba International Airport, Juba, by China Communications Construction Company

Following the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) and the establishment of the autonomous government of Southern Sudan, the building of a new, modern airport was initiated in 2009, but was marred by successive failures, which led to the squandering of vast sums of public money.

An unfinished terminal remains in that state and has been left abandoned. A new terminal with two halls was erected next to it and was finally inaugurated in October 2018.

The airport may not be photographed for security reasons. From an architectural point of view, it is hardly worthy of a photo, too.

What is interesting here again is that China has also extended its claws into South Sudan and has taken the small state in Africa under its wings as part of its global trade network.

Photo is by Katharina Paulweber

Eritrea Fiat Tagliero Service Station, Asmara, Giuseppe Petazzi

The Fiat Tagliero Service Station is probably the most remarkable building in Asmara and perhaps one of the finest examples of futurist architecture in Africa and the world.

Giuseppe Pettazzi designed the building to resemble the streamlined and dynamic form of a plane, and translated the modernist spirit of his time into a build manifesto. Its cantilevered concrete wings have a span of 30 metres and hang unsupported above street level.

The colonial architecture of the 20th century is a reminder of an inglorious chapter in European-African history. It is linked to racism and exploitation. It is no different in Eritrea.

But the Italian occupiers left behind an architectural heritage that is unique in the world. One could almost think that the architects were more creative in Africa than in their European homeland.

Photo is by Philipp Meuser

Djibouti Djibouti Cathedral, Djibouti, by Joseph Müller

A masterpiece of architecture! A clear cube, a successful composition of the entrance and a facade made of seashells that seems almost more mystical than the Word of God – no church can be built better!

Our Lady of the Good Shepherd Cathedral (Cathédrale Notre-Dame du Bon-Pasteur de Djibouti) was built on the site of a previous church, Sainte-Jeanne-d'Arc. The Bishop of Djibouti at the time, Henri Hoffmann, backed its construction, and the Catholic church was consecrated in January 1964.

The architect of the church, Joseph Müller (1906–1992), who drew its plans free of charge, acquired the nickname Kirchenmüller for the many religious buildings he designed at home in France and abroad, from the 1940s to the 1960s.

Photo is by Jennifer Tobolla

Ethiopia Lideta Market, Addis Ababa, by Vilalta Architects ⁄ Xavier Vilalta

Another cube. Another mystical building that works with the staging of light. But this is not a sacred building, it's a shopping temple!

The Lideta Market in Addis Ababa is a 14,200-square-metre multistorey building designed by Xavier Vilalta for a competition in 2010. It is located in an area that has been redeveloped within the frame of the government's housing programme.

The surrounding buildings define a dense and lively neighbourhood. The project is a simple rectangular volume with a carved interior void that creates an inclined atrium, which delivers a spatial quality to a traditional market layout.

The building is enclosed by a perforated concrete facade, which allows natural ventilation and light to flow in. The pattern of the facade is inspired by traditional Ethiopian dress and makes the building a landmark in the area.

Photo is by Heimo Liendl

Somalia Binocularsi, Mogadishu, by Carlo Enrico Rava

The Italian colonial heritage in Somalia is less preserved than in Eritrea. And the Arc de Triomphe is more irritating than reminiscent of an architectural heritage of world importance.

But the civil war has preserved few architectural monuments. Thus, even an almost destroyed relic of the Italian occupiers can become part of a new national identity.

This triumphal arch was designed by the Italian architect Carlo Enrico Rava and realised by the Ciccotti company to celebrate King Vittorio Emanuele III's visit to Mogadishu in December 1934. It stands by the seafront near the customs section of the old port, on a square formerly known as Piazza 21 April.

The arch is made up of rounded twin towers, joined in the middle – hence the name Binoculars.

The post Architecture highlights from northeast Africa include projects from Sudan and Somalia appeared first on Dezeen.

3 notes

·

View notes