#But then in the face of The Immanent Death Of Free Will

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It's always bothered me that we don't get to know what happened to that kid who was mistaken for Reynie when he got caught spying on the Executives and Recruiters.

Because, we know very few things about him:

He was a Messenger, and a candidate for an Executive in the future

He was a "special recruit" (Read: kidnapped and brainwashed child)

He was curious, and asking questions got him sent to the Waiting Room at least once

He was likely going to be retrained as a Helper, so he's probably an older teen

He's average looking

What else?? What happened to him??? Is he okay? Did he really end up being one of the Helpers and then Mr. Benedict gave him his memories back?

I've been thinking about him so much.

I've been calling him "Digory Hallows"; "Digory" being a French name meaning "lost one", and "Hallows" an English surname meaning "hollow". Also it just sounds like an MBS character name.

And I have decided that Milligan probably just rescued him in his spare time on the island and forgot to tell the other kids because there was so much going on.

He was moving around the Institute, pretending to be a Helper and trying to blend in, when he saw this kid getting taken away to get his brain swept. He's not super close, so for a minute Milligan also mistakes him for Reynie, and he starts panicking because How on earth did the kid get caught, I thought they were fine? Does this mean the others (Kate) are in trouble too?

So he runs over and takes out the Executives/Ten Men who have a hold of the kid, and part way through he realises from behaviour/lack of recognition/general demeanor that this kid isn't Reynie. But, he's not about to leave something half-finished, and the kid needs help anyway, so he finishes dealing with the situation. He then just kind of looks at this boy who is Clearly Not Reynie, and awkwardly introduces himself as "someone who will help".

The kid doesn't have any good information about the Whisperer, since he didn't have the background that Mr. Benedict gave the team, so after he relays a few details about the building set up and directions, Milligan helps him sneak onto a supply ship and escape. He also tells him to check in with some people they have connections with, so the boy isn't totally alone when he gets to the mainland.

And then the normal sequence of events proceeds and Milligan gets captured, etc., meanwhile Digory goes on to be the most accomplished useless side character ever, and gets a job on the Shortcut! Eventually, he makes his way back to Mr. Benedict and gets whatever memories he may have lost restored, but by then he's seen the world, and he settles down in Stonetown to be a journalist.

He does cross paths with Reynie and the others when he gets back, since Milligan checks in to see how he's doing, and Kate points out how similar the two look. At which point the whole story comes out, and Reynie apologises profusely, but Digory waves him off. He would have been stuck with Curtain for much longer if Milligan hadn't gotten him out, and he probably wouldn't have been able to see how bad things were going until it was too late.

As it is, he's happy with where he ended up. He can put his curiosity to good use and help people now, but he acknowledges that he was in way over his head at the Institute, and he wouldn't have been able to do what the kids did. However, he does help interview the Helpers and other ex-Messengers, and tries to get the information out about all the good Mr. Benedict did as much as he can.

#Keep in mind: Digory is exactly and exceptionally “okay” at all of these tasks#He doesn't make a big difference#But he tries#And so here is just yet another silly little tangent my brain decided to go down#If there is an explanation and I just missed it somehow because I'm an idiot I am going to spontaneously combust#Please take it with a grain of salt. It's so very stupid.#I just remember being totally stricken when I first learned about this kid#I know that the children had a lot on their shoulders#But since questions about that kid stayed with me I wonder if they bothered Reynie too#It does say he feels guilty about how everything is getting other people in trouble#But then in the face of The Immanent Death Of Free Will#Some stuff understandably slips through the cracks#Anyways I'm going to shut up now and stop rambling like a lunatic over an inconsequential detail that no one else cares about#the mysterious benedict society#mbs#reynie muldoon#milligan#milligan wetherall

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Modern Industry, indeed, compels society, under penalty of death, to replace the detail-worker of to-day, grappled by life-long repetition of one and the same trivial operation, and thus reduced to the mere fragment of a man, by the fully developed individual, fit for a variety of labours, ready to face any change of production, and to whom the different social functions he performs, are but so many modes of giving free scope to his own natural and acquired powers (...) But the historical development of the antagonisms, immanent in a given form of production, is the only way in which that form of production can be dissolved and a new form established. “Ne sutor ultra crepidam”* — this nec plus ultra of handicraft wisdom became sheer nonsense, from the moment the watchmaker Watt invented the steam-engine, the barber Arkwright, the throstle, and the working-jeweller, Fulton, the steamship." – Karl Marx, Capital Vol. 1, Ch. 15

*Latin: "Do not go to the shoemaker for anything more than shoes" (literally "the shoemaker is not above the shoe")

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

As for comfort, when we seek it, I can imagine none greater than the happy knowledge that when I see the death of a child I do not see the face of God, but the face of His enemy. It is not a faith that would necessarily satisfy Ivan Karamazov, but neither is it one that his arguments can defeat: for it has set us free from optimism, and taught us hope instead. We can rejoice that we are saved not through the immanent mechanisms of history and nature, but by grace; that God will not unite all of history’s many strands in one great synthesis, but will judge much of history false and damnable; that He will not simply reveal the sublime logic of fallen nature, but will strike off the fetters in which creation languishes; and that, rather than showing us how the tears of a small girl suffering in the dark were necessary for the building of the Kingdom, He will instead raise her up and wipe away all tears from her eyes—and there shall be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying, nor any more pain, for the former things will have passed away, and He that sits upon the throne will say, “Behold, I make all things new.”

David Bentley Hart, “Tsunami and Theodicy”

102 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think is the most 'human' part of Jonalias?

Human is a very abstract quality, isn't it? It's a bit ironic that the monsters considered antithetical to humanity are sustained by human fear, I've always thought. The line is explicitly blurred in canon, which we see as early as with Jane Prentiss and her terrified devotion.

But I think I know what you mean. Pain, death, and fear are immanent to the human condition; the desire to transcend these shackles is, therefore, the drive to become inhuman (this must not be equated with being evil; the only reason why Jonah's actions can be considered immoral is that his method for approaching divinity requires the suffering of others, not that there is something intrinsically wrong with not wanting to be human or an inherent moral purity or impurity in humanity). Ironically, this urge, actuated by fear, is in itself very human.

So, I'd say that the closer Jonah becomes to freeing himself of the weight of death the further away he gets from his humanity, and vice versa. Jonah is, in my opinion, a human person trying to carve himself into a god, and the closest he comes to his goal is when the Beholding makes him a part of its apotheosis. He becomes one with the sickening dread that has always haunted him, but it doesn't sink its claws into him; it merely passes through him because it recognises him as one of its own. To escape death, he must embrace it, wield it, and become it.

So I'd say Jonah is mostly human, especially since his motivation is fundamentally human. And he's at his most human in the moments after his agonised bliss is interrupted and he's faced with the reality of his imminent death; whatever criticisms I have of how that scene was written, there's something very poetic about that.

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

WOAH 1.8K??? That's amazing ace congrats aaaaa ok so I think I'm gonna do the lyric thing. Law and 'All I am is a man, I want the world in my hands'? (from sweater weather haha it's one of my favorite lyrics) thank you and ily <3

aaaah Lunes!!! Thank u sm~ (btw is it aight if I call u that?)

gfood song choice, I like it too and honestly...it fits his character very well

Word count: 588

Warnings: swearing maybe, uuuh bad thoughts? insecurities?

Law was tired. Of himself, of others, of silly dreams.

They all went to dust anyway. Life never went as planned and it frustrated him.

He was too young to feel this tired.

But then again he experienced at least ten people´s worth of bad luck and experiences.

His baggage was just about too heavy to carry at this point, but still he did. Because he had no other choice.

Of course he could always accept help, but that meant sharing his thoughts and past and nobody who would hear that would stick around, so it was all useless anyway.

And then there were you.

You who never gave up and always had something to say.

Law liked to pretend you were going on his nerves but you really weren´t.

You were challenging him, you were making him want to be alive.

He didn´t want his story to be over, he wanted yours to start, together.

The world you lived in was dangerous and he was done throwing his life away, instead he wanted to protect you, to show you all the beautiful places in the world and go on adventures with you.

He actually wanted to see new islands now, just because he could, because it was what pirates did.

Being a pirate suddenly meant so much more than coming closer to his already achieved goal and rebelling against the world government.

It meant being free and for the first time in his life he understood what that meant, he could actually feel the impact it had… the impact you had on him.

Because maybe love wasn´t so scientific after all. Maybe love was something to actively be experienced rather than calculated and overthought.

It was hard for Law to live this freely, so… spontaneously.

And yet he never thought it would feel this good.

Meeting new people, something he dreaded, exploring new islands, something that was such a bother to him before, now it was just every day life.

Oh and how he thrived.

Somehow it was much more fulfilling living a happy life to spite his enemies than to die for his dreams.

Especially with you by his side.

He loved living for and with you.

Every day was an adventure, but one he knew he would get out alive from.

Not one where he asked himself how anyone could be so stupid and just ignore all the plans and common sense like his temporary alliance with the Strawhats.

Who would´ve thought that life could be this exciting? Exciting in the most positive way, without his immanent anxiety, without second guessing everything and everyone.

Just plain and simple with you.

“What are you thinking of?” you asked, slowly walking up to him.

“Conquering the world” he smirked, making you chuckle.

“Alright, how about something more realistic?” you remarked, crossing your arms and shaking your head, still laughing.

Law could be quite silly sometimes even though he would deny it to his death.

“All I am is a man, I want the world in my hands” he just stated, making you raise an eyebrow.

“You´re so dramatic…” you sighed.

“How about something a bit more manageable?” you said.

“Oh, but it is the easiest thing I could ever dream of doing” he smirked widely and gently placed his hands on your face, softly caressing your cheeks.

“See? Now I got the whole world in my hands” he smiled.

“Trafalgar D. Water Law! You have no right being this cheesy!” you squealed, feeling your cheeks heat up.

#one piece#one piece imagine#one piece oneshot#one piece scenario#one piece drabble#one piece law#trafalgar d. water law#trafalgar law#law#law x reader#law imagine#law oneshot#law scenario#law drabble#op#op imagine#op drabble#op oneshot#op scenario#op law

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

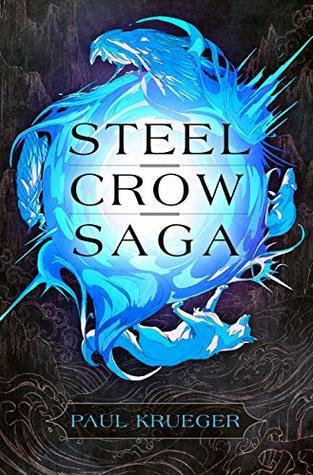

Reluctant Allies: Enemies Team Up: a reading list

Steel Crow Saga by Paul Krueger

Four destinies collide in a unique fantasy world of war and wonders, where empire is won with enchanted steel and magical animal companions fight alongside their masters in battle. A soldier with a curse Tala lost her family to the empress’s army and has spent her life avenging them in battle. But the empress’s crimes don’t haunt her half as much as the crimes Tala has committed against the laws of magic... and her own flesh and blood. A prince with a debt Jimuro has inherited the ashes of an empire. Now that the revolution has brought down his kingdom, he must depend on Tala to bring him home safe. But it was his army who murdered her family. Now Tala will be his redemption—or his downfall. A detective with a grudge Xiulan is an eccentric, pipe-smoking detective who can solve any mystery—but the biggest mystery of all is her true identity. She’s a princess in disguise, and she plans to secure her throne by presenting her father with the ultimate prize: the world’s most wanted prince. A thief with a broken heart Lee is a small-time criminal who lives by only one law: Leave them before they leave you. But when Princess Xiulan asks her to be her partner in crime—and offers her a magical animal companion as a reward—she can’t say no, and soon finds she doesn’t want to leave the princess behind. This band of rogues and royals should all be enemies, but they unite for a common purpose: to defeat an unstoppable killer who defies the laws of magic. In this battle, they will forge unexpected bonds of friendship and love that will change their lives—and begin to change the world.

Deception Cove by Owen Laukkanen

Former US Marine Jess Winslow reenters civilian life a new widow, with little more to her name than a falling-down house, a medical discharge for PTSD, and a loyal dog named Lucy. The only thing she actually cares about is that dog, a black-and-white pit bull mix who helps her cope with the devastating memories of her time in Afghanistan. After fifteen years — nearly half his life — in state prison, Mason Burke owns one set of clothes, a wallet, and a photo of Lucy, the service dog he trained while behind bars. Seeking a fresh start, he sets out for Deception Cove, Washington, where the dog now lives. As soon as Mason knocks on Jess's door, he finds himself in the middle of a standoff between the widow and the deputy county sheriff. When Jess's late husband piloted his final "fishing" expedition, he stole and stashed a valuable package from his drug dealer associates. Now the package is gone, and the sheriff's department has seized Jess's dearest possession — her dog. Unless Jess turns over the missing goods, Lucy will be destroyed. The last thing Mason wants is to be dragged back into the criminal world. The last thing Jess wants is to trust a stranger. But neither of them can leave a friend, the only good thing in either of their lives, in danger. To rescue Lucy, they'll have to forge an uneasy alliance. And to avoid becoming collateral damage in someone else's private war, they have to fight back — and find a way to conquer their doubts and fears.

Kingdom of Exiles by Maxym M. Martineau

Exiled beast charmer Leena Edenfrell is in deep trouble. Empty pockets forced her to sell her beloved magical beasts on the black market—an offense punishable by death—and now there's a price on her head. With the realm's most talented murderer-for-hire nipping at her heels, Leena makes him an offer he can't refuse: powerful mythical creatures in exchange for her life. If only it were that simple. Unbeknownst to Leena, the undying ones are bound by magic to complete their contracts, and Noc cannot risk his brotherhood of assassins...not even to save the woman he can no longer live without.

Winter of Ice and Iron by Rachel Neumeier

In this gorgeous, dark fantasy in the spirit of Jacqueline Carey, a princess and a duke must protect the people of their nations when a terrible threat leaves everyone in danger. With the Mad King of Emmer in the north and the vicious King of Pohorir in the east, Kehara Raehema knows her country is in a vulnerable position. She never expected to give up everything she loves to save her people, but when the Mad King’s fury leaves her land in danger, she has no choice but to try any stratagem that might buy time for her people to prepare for war—no matter the personal cost. Hundreds of miles away, the pitiless Wolf Duke of Pohorir, Innisth Eanete, dreams of breaking his people and his province free of the king he despises. But he has no way to make that happen—until chance unexpectedly leaves Kehara on his doorstep and at his mercy. Yet in a land where immanent spirits inhabit the earth, political disaster is not the greatest peril one can face. Now, as the year rushes toward the dangerous midwinter, Kehera and Innisth find themselves unwilling allies, and their joined strength is all that stands between the peoples of the Four Kingdoms and utter catastrophe.

#fiction#fantasy#mystery#thriller#enemies to lovers#enemies to friends#teamwork#book recs#adult books#adult fiction#reading recommendations#recommended reading#to read#booklr#tbr#library#romance

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“ Should the Haruspex attempt to autopsy her body on Day 11, he will make the curious discovery that Aglaya does not appear to have any organs. However, looting her body reveals she is carrying a Revolver. “

trawling some highly enjoyable patho wiki content. Congratulations Aglaya Lilich on becoming a Body without Organs, with a gun! you go girl!

“Aglaya contends with God. Those she touches begin to rebel against the established order of things. At the same time, Aglaya is the voice of the law. She sees the universe as a machine. She maintains that the logic of the universe is above everything—polyhedrons be damned. To her, contending with God, too, is a form of restoring justice and natural law. Those she touches begin to realize that there are limits of what’s possible, and they must be accepted with humility.”

Humility

“I should have written nothing[1] at all, but it is far too late for that. Sin and guilt[2] have entered the world[3]— never mind where from, since in any case it would do no good to close that box — and I am no longer striding the crests of my dreams, filling my lungs with air and expelling it again, now instead I am manipulating the keys of a machine[4] striving to thus let my dreams pour and play out across the space of an information-obsessed plane of existence.

There exists no good reason[5] to occupy this space, especially when I have the heights and depths of life wholly available to me at any moment, and yet something compels me, God help me.[6] I have no hope that I will save anyone this way. Not even myself. I know I will not even reach to prevent the wretched[7] from abusing whatever I create. It is a fact that to take something from oneself and put it out into the world is to let it escape and become everything you didn’t want it to be. They say this is so for God the Father as for every human father. I do not believe in either one, but their stories both hold a strange beauty for me.

One can create a monster[8] or a babe; the difference is purely aesthetic. But it is this question of creation. Many simply put it aside, to their own loss. They still create things but they deny they are doing so. They are befallen by atrophy.[9] Others take on the question of creation by accepting the market assurance that whatever makes money must be good because, so the logic goes, people buy things that are good.[10] They become lost to the world of production. Others, in reaction to this, turn toward smaller and smaller circles to keep their creatures safe from the real world. But these spaces are either infected by the social disease or else suffocate for lack of oxygen.

There are some rare exceptions. No one can say where they come from. They destroy all that has come before. They blow into a dying ember. Without them there would be nothing at all.

Now, we have to say that the whole world without them would be an empty[11] dull[12] pale[13] and suffocating lifeless and deathless nothingness, and that they themselves are also a nothingness, but an ecstatic explosion of creative destructive nothingness. So it will be worth keeping in mind that there is a huge and unspeakable gap between the qualities of different sorts of nothingness. Otherwise everything will be overcome by an immense confusion.[14]

The first aspect which ensures that there is something interesting rather than nothing is the explosive energy of the sun. The second is the implosive energy of the earth. These provide for the habitation of a thin membrane where their intercourse takes place. Here there exists a tension between them. Much life forms by rebelling against being crushed into the bowels of the earth and the depths of the sea, whether this rebellion is volcanic, evaporative, or organic. Life must protect itself from being lost in the emptiness of space or scorched in the heat of the sun, and so it also flows, crumbles, burrows, glides, swims, falls and floats downward. This might be all, were it not for something else. Organization, organism, orgasm.[15]”

-Musings on Nothingness (And Some of It’s Varieties)

“Producing, a product: a producing/product identity. It is this identity that constitutes a third term in the linear series: an enormous undifferentiated object. Everything stops dead for a moment, everything freezes in place—and then the whole process will begin all over again. From a certain point of view it would be much better if nothing worked, if nothing functioned. Never being born, escaping the wheel of continual birth and rebirth, no mouth to suck with, no anus to shit through. Will the machines run so badly, their component pieces fall apart to such a point that they will return to nothingness and thus allow us to return to nothingness?

It would seem, however, that the flows of energy are still too closely connected, the partial objects still too organic, for this to happen. What would be required is a pure fluid in a free state, flowing without interruption, streaming over the surface of a full body. Desiring-machines make us an organism; but at the very heart of this production, within the very production of this production, the body suffers from being organized in this way, from not having some other sort of organization, or no organization at all. "An incomprehensible, absolutely rigid stasis" in the very midst of process, as a third stage: "No mouth. No tongue. No teeth. No larynx. No esophagus. No belly. No anus."

The automata stop dead and set free the unorganized mass they once served to articulate. The full body without organs is the unproductive, the sterile, the unengendered, the unconsumable. Antonin Artaud discovered this one day, finding himself with no shape or form whatsoever, right there where he was at that moment. The death instinct: that is its name, and death is not without a model. For desire desires death also, because the full body of death is its motor, just as it desires life, because the organs of life are the working machine. We shall not inquire how all this fits together so that the machine will run: the question itself is the result of a process of abstraction.”

-Anti-Oedipus ch. 1, “THE DESIRING MACHINES”

youtube

I can't stitch it together… but I can cut the knot.

We're all just… dancing on our strings.

Whenever I trace the edges of possibility on a map, I find myself reaching for an eraser not soon after…

Imagine a sphere. See it in your mind's eye. Now lay it out flat. Why is that so easy, when topology is so hard?

We live under the shadow of a higher power… I just despise it.

Only a fool would cut the Gordian knot. It ought to be… vivissected.

The squeal of the gears can't halt the machine.

Why do they insist on torturing me?

There is an immutable and rational order that fate itself has composed. All things run their inevitable courses, down the topology of the universe, toward the mass of this black gravity.

Let's open it. Carefully. And tally the contents.

The judgment of God, the system of the judgment of God, the theological system, is precisely the operation of He who makes an organism, an organization of organs called the organism, because He cannot bear the BwO, because He pursues it and rips it apart so He can be first, and have the organism be first. The organism is already that, the judgment of God, from which medical doctors benefit and on which they base their power. The organism is not at all the body, the BwO; rather, it is a stratum on the BwO, in other words, a phenomenon of accumulation, coagulation, and sedimentation that, in order to extract useful labor from the BwO, imposes upon it forms, functions, bonds, dominant and hierarchized organizations, organized transcendences.

The strata are bonds, pincers. “Tie me up if you wish.“ We are continually stratified. But who is this we that is not me, for the subject no less than the organism belongs to and depends on a stratum? Now we have the answer: the BwO is that glacial reality where the alluvions, sedimentations, coagulations, foldings, and recoilings that compose an organism—and also a signification aid a subject—occur. For the judgment of God weighs upon and is exercised against the BwO; it is the BwO that undergoes it. It is in the BwO that the organs enter into the relations of composition called the organism.

The BwO howls: “They’ve made me an organism! They’ve wrongfully folded me! They’ve stolen my body!“ The judgment of God uproots it from its immanence and makes it an organism, a signification, a subject. It is the BwO that is stratified. It swings between two poles, the surfaces of stratification into which it is recoiled, on which it submits to the judgment, and the plane of consistency in which it unfurls and opens to experimentation.

If the BwO is a limit, if one is forever attaining it, it is because behind each stratum, encasted in it, there is always another stratum. For many a stratum, and not only an organism, is necessary to make the judgment of God. A perpetual and violent combat between the plane of consistency, which frees the BwO, cutting across and dismantling all of the strata, and the surfaces of stratification that block it or make it recoil.

- “ Deleuze/Guattari; How Do You Make Yourself a Body Without Organs? “

youtube

(every morning i listen to confessional, i don’t give a shit bout the bulk ov it, still i keep it professional. and as penance i tell em to proselytize, say the sun is red, say that i am red, say that all their bases belong to us)

The crack Where is the crack? When did I crack?

Then I’ll stand alone on a planet with Nothing left to remember it And I’ll try, I’ll try, I’ll try to prevent it I’ll try, I’ll try, but I’ll never stop it, no

Muzzle me, muzzle muzzle me Bind my will and break of me And you try, you try, you try to prevent it You’ll try, you’ll try, but you’ll never stop it, no

because, laugh if you like, what has been called microbes is god, and do you know what the Americans and the Russians use to make their atoms? They make them with the microbes of god.

- I am not raving. I am not mad. I tell you that they have reinvented microbes in order to impose a new idea of god.

They have found a new way to bring out god and to capture him in his microbic noxiousness.

This is to nail him though the heart, in the place where men love him best, under the guise of unhealthy sexuality, in that sinister appearance of morbid cruelty that he adopts whenever he is pleased to tetanize and madden humanity as he is doing now.

He utilizes the spirit of purity and of a consciousness that has remained candid like mine to asphyxiate it with all the false appearances that he spreads universally through space and this is why Artaud le Mômo can be taken for a person suffering from hallucinations.

- What do you mean, Mr. Artaud?

- I mean that I have found the way to put an end to this ape once and for all and that although nobody believes in god any more everybody believes more and more in man.

So it is man whom we must now make up our minds to emasculate.

- How's that?

No matter how one takes you you are mad, ready for the straitjacket.

- By placing him again, for the last time, on the autopsy table to remake his anatomy. I say, to remake his anatomy. Man is sick because he is badly constructed. We must make up our minds to strip him bare in order to scrape off that animalcule that itches him mortally,

For you can tie me up if you wish, but there is nothing more useless than an organ.

To Have Done With the Judgement of God

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WHAT THE VIRUS SAID

First published in Lundimatin, March 16, 2020

Translated by Robert Hurley

“I’ve come to shut down the machine whose emergency brake you couldn’t find.”

You’d do well, dear humans, to stop your ridiculous calls for war. Lower the vengeful looks you’re aiming at me. Extinguish the halo of terror in which you’ve enveloped my name. Since the bacterial genesis of the world, we viruses are the true continuum of life on Earth. Without us, you would never have seen the light of day, any more than the first cell would have come to exist.

We are your ancestors, just like the rocks and the seaweed, and much more than the apes. We are wherever you are and also where you aren’t. Too bad for you if you only see in the universe what is to your liking! But above all, quit saying that it is I who am killing you. You will not die from my action upon your tissues but from the lack of care of your fellow humans. If you had not been just as rapacious amongst yourselves as you were with all that lives on this planet, you would still have enough beds, nurses, and respirators to survive the damage I do in your lungs. If you didn’t pack your old people into nursing homes and your able-bodied into concrete hutches, you wouldn’t be in this predicament. If you hadn’t changed the whole expanse of the world, or worlds rather, that just yesterday were still luxuriant, chaotic, infinitely inhabited, into a vast desert for the monoculture of the Same and the More, I wouldn’t have been able to launch myself into the global conquest of your throats. If nearly all of you had not become, over the last century, redundant copies of a single, untenable form of life, you would not be preparing to die like flies abandoned in the water of your sugary civilization. If you had not made your environments so empty, so transparent, so abstract, you can be sure that I wouldn’t be moving at the speed of an aircraft. I only come to carry out the punishment that you have long pronounced against yourselves. Forgive me, but it’s you, after all, who invented the name “Anthropocene”. You have awarded yourselves the whole honor of the disaster; now that it is unfolding, it’s too late to decline it. The most honest among you know this very well: I have no other accomplice than your social organization, your folly of the “grand scale” and its economy, your fanatical belief in systems. Only systems are “vulnerable”. Everything else lives and dies. There’s no “vulnerability” except for what aims at control, at its extension and its improvement. Look at me closely: I am just the flip side of the prevailing Death.

So stop blaming me, accusing me, stalking me. Working yourselves into an anti-viral paralysis. All of that is childish. Let me propose a different perspective: there is an intelligence that is immanent to life. One doesn’t need to be a subject to make use of a memory and a strategy. One doesn’t have to be a sovereign to decide. Bacteria and viruses can also call the shots. See me, therefore, as your savior instead of your gravedigger. You’re free not to believe me, but I have come to shut down the machine whose emergency brake you couldn’t find. I have come in order to suspend the operation that held you hostage. I have come in order to demonstrate the aberration that “normality” constitutes. “Delegating to others our nutrition, our protection, our ability to care for our way of life was a madness”…“There is no budgetary limit, health has no price” : see how I redirect the language and spirit of your governing authorities! See how I bring them down for you to their real standing as miserable racketeers, and arrogant to boot! See how they suddenly denounce themselves not just as being superfluous, but as being harmful! For them you’re nothing but supports for the reproduction of their system – that is, less than slaves. Even the plankton are treated better than you.

But don’t waste your time reproaching them, pointing out their deficiencies. Accusing them of negligence is still to give them more credit than they deserve. Ask yourselves rather how you could find it so comfortable to let yourselves be governed. Praising the merits of the Chinese option compared to the British option, of the imperial-legist solution as against the Darwinist-liberal method is to understand nothing about the one or the other, the horror of one and the horror of the other. Since Quesnay, the “liberals” have always looked with envy at the Chinese empire ; and they still do. They are Siamese twins. The fact that one of them confines you in its interest and the other in the interest of “society” always amounts to suppressing the only non-nihilist conduct : taking care of oneself, of those one loves and of what one loves in those one doesn’t know. Don’t let those who’ve led you to the abyss claim to be saving you from it: they will prepare for you a more perfect hell, an even deeper grave. Someday when they’ll able, they’ll send the army to patrol the afterlife.

You ought to thank me, rather. Without me, for how much longer would those unquestionable things that are suddenly suspended have gone on being presented as necessary? Globalization, competitive exams, air traffic, budgetary limits, elections, sports spectacles, Disneyland, fitness gyms, most businesses, the National Assembly, school barracking, mass gatherings, most office jobs, all that automatic sociability that is nothing but the reverse of the anxious solitude of the metropolitan monads : all of that was rendered unnecessary, once the state of necessity asserted its presence. Thank me for the truth test of the coming weeks; you’re finally going to inhabit your own life, without the thousand escapes that, good year bad year, hold the untenable together. Without your realizing it, you had never taken up residence in your own existence. You were there among your boxes, and you didn’t know it. Now you will live with your kindreds. You will be at home. You will cease to be in transit towards death. Perhaps you will hate your husband. Maybe your children won’t be able to stand you. Maybe you will feel like blowing up the décor of your everyday life. The truth is that you were no longer in the world, in those metropolises of separation. Your world was no longer livable in any of its guises unless you were constantly fleeing. One had to make do with movement and distractions in the face of the hideousness that had taken hold. And the spectral that reigned between beings. Everything had become so efficient that nothing made any sense any longer. Thank me for all that, and welcome back to earth!

Thanks to me, for an indefinite time you will no longer work, your kids won’t go to school, and yet it will be the opposite of a vacation. Vacations are that space that must be filled up at all costs while waiting for the obligatory return to work. But now what is opening up in front of you, thanks to me, is not a delimited space but a gaping emptiness. I render you idle. There’s no guarantee that yesterday’s non-world will reappear. All of that profitable absurdity may cease. Not being paid oneself, what would be more natural than to stop paying one’s rent? Why would a person unable to work go on depositing their mortgage payments at the bank? Isn’t it suicidal, when you come down to it, to live where you can’t even cultivate a garden? Someone who doesn’t have any money left doesn’t stop eating as a consequence, and who has the iron has the bread. Thank me: I place you in front of the bifurcation that was tacitly structuring your existences: the economy or life. It’s your move, your turn to play. The stakes are historical. Either the governing authorities impose their state of exception on you, or you invent your own. Either you go with the truths that are coming to light, or you put your head on the chopping block. Either you use the time I’m giving you to envision the world of the aftermath in light of what you’ve learned from the collapse that’s underway, or the latter will go extreme. The disaster ends when the economy ends. The economy is the devastation. That was a theory before last month. Now it is a fact. No one can fail to sense what it will take in the way of police, propaganda, surveillance, logistics, and remote working to keep that fact under control.

As you deal with me, don’t succumb to panic or denial. Don’t give in to the biopolitical hysterias. The coming weeks will be terrible, oppressive, cruel. The gates of death will be wide open. I am the most devastating production of the devastation of production. I come to reduce the nihilists to nothingness. The injustice of this world will never be more outrageous. It’s a civilization, not you, that I come to bury. Those who desire to live will have to construct new habits, ones that are suitable for them. Avoiding me will be the occasion for this reinvention, this new art of distances. The art of greeting one another, which some were short-sighted enough to see as the very form of the institution, will soon not obey any etiquette. It will sign beings. Don’t do it “for the others”, for “the population” or for “society”, do it for your people. Take care of your friends and those you love. Rethink along with them, decisively, what a just form of life would be. Organize clusters of right living, expand them, and I won’t be able to do anything against you. I am calling for a massive return, not of discipline, but of attention. Not for the end of insouciance, but the end of all carelessness. What other way remained for me to remind you that salvation is in each gesture? That everything is in the tiniest thing.

I’ve had to face the facts: humanity only asks itself the questions it can no longer keep from asking.

65 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Obvious from the offensive quotation above—found on a blog recently popularized on right-wing TV—is the fatal contradiction in the radical feminist’s anti-transgender worldview. Is separation of identity from biology, the reversal of Freud’s infamous equation of anatomy and destiny, not the telos of second-wave feminism, as of the Marxism from which second-wave feminism was derived?—to wit: the destruction of gender identity itself, the refusal to apply gender definition, which was on this view only ever a legitimating ideology of labor exploitation, to the mere biological substrate out of which the free and ideally genderless subject is to be formed. And when the radical feminist accuses the rich of meddling in these matters, such moralism neglects that technological changes make the abolition of gender nearly inevitable. Once we went to live online, “biological sex” didn't stand a chance. The rich are only following this logic, not imposing it out of some strange religious desire. By "strange religious desire” I allude to the controversial thesis that contemporary evolving gender norms, among much else in our culture, represents a return of gnosticism, e.g., The Matrix with its retrospectively understood trans subtext. Writers up and down the status scale and all over the genre map and across the political spectrum[*] have argued that we live in a gnostic world and have been for almost a century, that postmodernism is nothing but late antiquity misspelled. As I think the cyberpunks once argued, gnostic theology was only ever a presentiment of “online.” But unless the radical feminist proposes to go back to church, I don't see what she plans to do about it from within the conceptual horizon of Marxism, which is in itself, as Eric Voeglin long ago taught us, always already gnostic. To secure matter as essence—among other things, to make boy and girl permanently adhere to bodies—requires a transcendent source of matter, rather than gnosticism's alien God scattered like gems through the offal of the demiurge’s botched work; sans a transcendent but, as it were, in-universe God, matter is pure virtuality, which the sovereign soul, the alien God within and therefore immanent to matter, can alter as it wishes. One caution: these moments of idealism and instability tend not to last, so we may all be going back to church eventually, whether we like it or not, and sooner than we think. In my novel Portraits and Ashes, which I wrote the year before the topic of gender identity began to occupy public consciousness, including mine, and which begins and ends in an abandoned church, I portrayed a cult that abolishes its congregants' gender (and not only gender) through surgical intervention and that alters their various personal pronouns to it. I did not have anything like transgender identity in mind, since I understand this identity to be a matter of individual determination, whereas my interest was in collective ecstasies. As the novel’s lexicon and motifs make clear, I was thinking of radical religious movements and their relation to communism—my direct inspiration was probably the Skoptsy, which I learned about from James Meek’s once-hyped and now-forgotten Russian Revolution historical fiction of 2005, The People's Act of Love (I didn’t read Dostoevsky’s Demons until 2014 or so). The Skoptsy were officially claimed for queerness in a 2018 article—that is, six years after I wrote and one year after I published the book. You can tell I wasn't conscious of any such subtext during the composition because when I show leftist academics in the novel heaping high-theory rhetoric on the cult—which I intended as an #Occupy-era spoof of certain upper-class radical mooning over a fancied working class—it didn’t even occur to me to have the professoriate laud them as “queer,” as in this scene, set on a public bus, where a young scholar’s assessment of the phenomenon—in the first quoted paragraph—contrasts with an older man’s judgment in the hearing of my delirious heroine:

“They’re the revolutionary multitude, all of the excluded, man as species, affect generalized, the persistence of life apart from consciousness, the sublime purity of the conatus against all territorializations. Immanent being without intent or control. They aren’t subjects. They’re post-humanity. What comes after the subject. The reign of love.”

Julia opened her feverish eyes in time to see that the old man had turned from the window and faced her again. He said, very quietly, through thin white lips, his eyes wide and wet, as if addressing only her, “Essenes. Desert Fathers. Bogomils. Albigenses. Fifth Monarchy Men. The rejection of this world.”

All these issues were on the table when I independently published the novel in 2017, if not when I wrote it five years before, but I trusted that my meaning—my sympathetic inquiry into various configurations of spirit and matter—was clear enough to prevent the giving of broad offense. I am no longer quite so certain, but then this conversation is not yet finished or final either. As my older relatives used to say of death, so my literary generation might say of cancellation: You’ve got to go sometime. And if I’m cancelled for having written a great novel, well, the gnostic God knows that I’m certainly in good company!

_____________________

[*] Eric Voeglin, Harold Bloom, Elaine Pagels, Victoria Nelson, Umberto Eco, John Gray, Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, Toni Morrison, etc.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Based on your response to the comment regarding the use of Althusserian concepts; would you say a revolutionary process necessarily involves conscious elements? And are there other concepts of the state that you prefer over the instrumental view of the state?

i guess my argument would be that, even outside of revolutionary scenarios, the traditional understanding of class tends emphasize consciousness in a peculiar (and moralistic way), which is to treat The Capitalists (bad guys) as extremely aware of what’s actually going on while The Workers (good guys) suffer from “false consciousness” (overstated in the secondary literature, compared to its relative non-existence in the primary sources. engels used the term like, Once). the problem then is about whipping up proletarian consciousness (often assumed to be somehow automatically revolutionary after that has been done) against the deliberate attempts by capital (understood here as a group of people) to obscure the realities of the system. althusser’s work is an elaboration on this view.

marx, however, had a completely different approach, which is to focus on the way that capital (now appropriately understood as an “automatic subject”, as a self-moving substance with its own logic) obscures itself. in the unfolding of capital’s categories, marx shows how the money-form covers the tracks of the law of value’s operation at a higher level of abstraction so that there appears to be a contradiction between the “theories” of value and money, when in reality the paradox is immanent to the system and not a matter of conflicting understandings (the common criticism that marx contradicts himself between value and money, value and price, etc stems from this confusion).

what this means is that the concepts are generative of multiple understandings of the concepts themselves, and that these appear contradictory so that these conceptions are often developed into one-sided theories of political economy. this is why marxs project takes the form of a genealogical critique of political economy, which requires interrogating the social forms in order to understand why they appear the way that they do, and why they, bearing the function of social mediation, determine our actions in such a way as to produce and reproduce everyday life, i.e. capitalism, thereby naturalizing it.

this involves an implicit theory of knowledge and necessarily has huge ramifications for how we can understand the development and limitation of class consciousness, because the object under investigation presents itself in a distorted manner. as marx says,

“Reflection on the forms of human life, hence also scientific analysis of those forms, takes a course directly opposite to their real development. Reflection begins post festum, and therefore with the results of the process of development ready to hand. The forms which stamp products as commodities and which are therefore the preliminary requirements for the circulation of commodities, already possess the fixed quality of natural forms of social life before man seeks to give an account, not of their historical character, for in his eyes they are immutable, but of their content and meaning. Consequently, it was solely the analysis of the prices of commodities which led to the determination of the magnitude of value, and solely the common expression of all commodities in money which led to the establishment of their character as values. It is however precisely this finished form of the world of commodities - the money form - which conceals the social character of private labour and the social relations between the individual workers, by making those relations appear as relations between material objects, instead of revealing them plainly. If I state that coats or boots stand in a relation to linen because the latter is the universal incarnation of abstract human labour, the absurdity of the statement is self-evident. Nevertheless, when the producers of coats and boots bring these commodities into a relation with linen, or with gold or silver (and this makes no difference here), as the universal equivalent, the relation between their own private labour and the collective labour of society appears to them in exactly this absurd form.

The categories of bourgeois economics consist precisely of forms of this kind. They are forms of thought which are socially valid, and therefore objective [my emphasis], for the relations of production belonging to this historically determined mode of social production, i.e. commodity production. The whole mystery of commodities, all the magic and necromancy that surrounds the products of labour on the basis of commodity production, vanishes therefore as soon as we come to other forms of production.” [v1: p168-9, penguin ed.]

all of this is to say that the existence of a class unconsciousness does not require a class of evil puppeteers working behind the scenes to obscure the real functioning of the capitalist mode of production; the system generates its own obscuration independently of social actors and, as marx says, involves “a social process that goes on behind the backs of the producers” [v1: p135], which also necessarily applies to the capitalists themselves. all of this is why fetishism is so important to marx, and runs throughout the 3 volumes of capital, explicitly reappearing at the end of v3 when marx tackles the trinity formula. it is only after this is explained that marx closes the chapter on “the revenue and its sources” [part 7 in engels’ edition, divided into smaller chapters] with what we now have as a fragment of the final “chapter” of the three volumes of capital: “classes”.

i dont think this ordering of the sections is an accident, as the elaboration on classes could only come after the clarification of the fetish-forms of the trinity formula, which necessarily complicates the notion of a class of omniscient agents directly overseeing and controlling society, and which also affirms the existence of “the three great classes of modern society based on the capitalist mode of production” [v3: p1025, penguin ed.], contrary to the earlier position developed at the beginning of the communist manifesto where he says that the bourgeois epoch has “simplified class antagonisms”, with the increasing reduction “into two great hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each other — Bourgeoisie and Proletariat”, which is generally the starting point for most marxist perspectives on class struggle in capitalism.

an alternative theorization/critique of the capitalist state (and with it, the theory of knowledge as it relates to the development of consciousness) would deal with the historically specific nature of capitalist social relations, especially the distinct form of impersonal domination where political and economic rule are divorced from one another in a way that differentiates bourgeois society from others, such as feudalism, where the serf stood in relation to the landlord as the former’s direct political-economic ruler. under capitalism, however, your employer at a retail establishment does not hold direct political power over you, just as the state which you must otherwise obey does not directly control whether or not you may quit your job in retail and move to some other industry. this is the sense in which the onslaught of capital involves the dual constitution of the “free laborer” and “legal subject”, with the former involving the historical “freeing” of labor from the land (and the corresponding freedom to starve to death if one does not submit to wage-labor), while our equivalence as legal subjects in labor contracts is dealt with by marx in a single sentence: “Between equal rights, force decides.” [v1, p344]

obviously, if we were politically and economically ruled by capitalists in a direct way like that which characterizes feudalism, and which is suggested by the instrumentalist conception of the state, this separation would not need to exist (although the conspiracy theorist’s rendering of the theory would be that this separation is an intentionally illusory one meant to make us feel as if we are free, even though this is, as i already suggested, something generated by the system itself regardless of any class malevolence). any critique of the state worth paying attention to must be able to grapple with all of this, and i think the best starting point would be the work of legal scholars like pashukanis and the german state derivation debates beginning in the 1970s, as well as some more recent elaborations by those associated with the “open marxist” tradition (holloway, clarke, bonefeld, etc).

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fire and Reign: Necromancy

Finally, we have witches au chapter four! I am so sorry for the delay here, and for the length. It’s a bit shorter than usual, but the next chapter will be action packed! I don’t think there are TWs for this chapter, so enjoy loves

Ao3 Link https://archiveofourown.org/works/19249039/chapters/47313391

“Find anything else since we last talked?” Called Aragon as she made her way into the greenhouse with a mug of coffee in her hand, eyes still bleary from sleep.

A sleep deprived, but alert Catherine Parr glanced up to her godmother worriedly, it was abnormal for her to be up this early. She glanced at the clock. It was only eight. Usually Aragon awoke around an hour later, looking much less frazzled. Stray curls stuck out at angles and she still wore her pajamas.

Catherine frowned then, at the question asked. In reality, she hadn’t been able to uncover anything new, even with the help of the American Supreme. “You’re up earlier than usual,” she nodded, completely avoiding the subject as a whole.

“Didn’t want to sleep in,” Aragon shrugged, quickly dispelling any further discussion on the topic. Parr nodded, knowing when she didn’t want to broach a topic.

“What about Henry? I need to know if we have anything new,” An unspoken, ‘I have to do something,’ stayed in her head. Aragon tried again. Since Anne’s sighting the previous night, she’d practically been on hyperdrive. Sleep had been fitful and erratic because all she could do was contemplate possible avenues, and who his next victim might be.

Realistically, it could be anyone in London. The lack of knowledge concerning witches and the secrecy put blinders on most people, including young witches themselves. As a result, Henry’s scope of possible victims had much greater magnitude than she would have liked.

Finding witches and protecting them would be ideal; however, Catherine knew the semantics of that plan were much more complex in practice. Finding young witches was about as difficult as finding a needle in a haystack, unless of course you were finding their mangled corpses, she thought bitterly to herself.

Parr observed the other woman, the clipped question’s brittle tone bounced off of her. She could only imagine what it would be like to be in the Supreme’s shoes. As a child, she’d dreamt about the idea of being the Supreme and being trusted to lead, but as she’d grown to understand what the job entailed, she realized she didn’t want that. She wanted to care for her coven, but her decisions couldn’t be the difference between life or death. She understood Catherine’s stress, and if she was honest, everyone in the house now felt it.

Shockwaves of the harsh reality that Henry was ready to kill, hadn’t settled easily among any of the queens. All of them had known in a certain capacity it was true, but there was something about the casual encounter that reminded everyone of the immanence in the situation.

“No,” Parr finally answered. “I’ve done just about everything I can, and contacted the Supremes in Spain, France, and Germany. They never linked the killings even. It seems like whoever’s employing him was moving him around or giving him spot kills there, but of course I have no evidence to back that up. It’s purely assumption, and he’s smart. He doesn’t leave a paper trail or physical evidence. If we knew a last name it could be helpful, but even then I'm not sure we’d have anything concrete,” she admitted with a regretful shrug.

“So we’re stuck?” Aragon asked, her mouth falling into a thin line as she wracked her brain for anything helpful. Nothing. Then it hit her, his victims were the key. “Do you think that he’s killed everyone here in the same location? Or at least remotely so,” she added.

Parr tilted her head, “Probably, he seems consistent in London.”

“Great. That’s all I needed to know,” Aragon nodded, a small smile replacing the frustration, a bit self satisfied with her own idea. “I’ll talk to you later, love, but I think I might have an idea of something we can do.”

Catherine raised an eyebrow in shock but nodded, “See you later then.” Aragon turned to exit the greenhouse and return to her office. First things first, she had to do some research of her own, then she needed to speak to the council.

She wasn’t sure she had the proper books in her office, Most likely, she’d have to search the attic.. Necromancy as a whole was risky business, and when done wrong, things could go south in the blink of an eye. Of course Aragon was competent enough to perform the type of magic properly, but not without proper research. The last Supreme, her mother, coincidentally, had always had a bit of an interest in the darker aspects of magic and the more ‘forbidden’ things.

For example, Catherine vividly remembered her mother practicing descensum frequently. She’d later explained she’d only done so in an attempt to understand hell and understand who and what lived down there. Aragon herself had never had much of an interest as a result.

She understood the consequences of failing descensum. One would be trapped in hell and their body would disintegrate. No matter if they beat their personal hell, if they didn’t bring themselves back in time they’d be gone. She hated that her mother ran that risk so often, and for what? As far as Aragon was concerned there were no practical purposes, as understanding hell was futile.

Catherine’s own experience with descensum had been as she’d expected: hellish. Her hell consisted of the coven disowning her and her being thrown to the streets only to have Henry and his manipulative, vindictive ways waiting for her outside the doors. No one thought she’d make it back in time, and truthfully she’d only just made it back before dawn, panting and panicked she’d bolted up. How did anyone get used to beating their hell and how did anyone do it regularly? The concept baffled her.

Her mother had fittingly also been interested in learning about necromancy, which granted was a lot less dangerous than casually practicing descensum. It couldn’t directly destroy the caster, but any number of bad outcomes could occur without understanding how to properly control such magic and without knowing exactly whom one was contacting. At one point, Catherine had a mild interest in the basics, but quickly strayed away from it once she began to understand the negative consequences: it could put those she cared about in danger.

Now it seemed she’d have to return to her old interest and ignore the overly analytical and cautious voices in her head that told her necromancy was a bad idea. Upon a small browsing of her office shelves, unsurprisingly, she found nothing of use. With a short sigh of impatience, she turned to traipse her way up the stairs to the attic.

Upon pushing the door open, she observed Jane’s workspace. Books sat strewn on the table’s surface and pages of notes sat stacked in one corner. Her stones sat atop one open book and a separate sheet of notes sat beside the stones. Part of Aragon felt inclined to see what Jane had been working on, but she stopped, reminding herself that Jane would let her know when the time was right.

Instead, she made her way toward the dust covered boxes containing her mother’s old books. She went through two boxes before she found what she needed: books on the foundations and extended applications of necromancy. Now that she had the books she could hopefully find what she needed. And once the adequate research was done she could call the council and see if they approved of her plan. Back to her office to read, it seemed.

By the time she finished relaying the cornerstones of her reading and in detail her plan, Anna and Jane each had their own looks of shock and intrigue on their face.

“Do you think that’ll work?” Asked Jane.

“The magic or the plan?” Anne countered the blonde as if Jane’s question hadn’t been directed at Catherine. She was caught up in the semantics and possible dangers of what Aragon her proposed to even question effectiveness yet.

Jane glanced at the short haired woman beside her, “I was addressing both actually. Messing with necromancy can be dangerous, and in practice this plan is basically built on assumptions.”

Aragon cut in, “I know the dangers, but we’re at a practical roadblock on learning anything else. We haven’t been able to ID any of his victims easily, and I’ve had Cathy doing some research for me. She’s also been unable to find anything else. If my hunch is right, then this could get us somewhere,” she insisted.

“But if something were to go horribly wrong, for example, you could contact the wrong spirit, and set something free or be unable to contain it. There’s also physical safety to take into account when you think of this. What if someone happened upon you?”

“I’m planning to take Anne with me. You know she’s not easily scared off by a task, and should something happen she knows how to fight,” Catherine raised a brow. She understood Anna and Jane’s concern, she needed to do something. “As for what we talk to, I should be able to contain it. I’m no novice,” she added with a hint of mirth in an attempt to lighten the mood.

The other two women shared a weary look, ultimately Aragon did have a final say in what she did. They hadn’t had to have been called in, which meant she most likely wanted their support and help ironing out details of the plan. “So, when do you want to leave?” Jane asked after a moment’s silence. She could feel waves of urgency and underlying anxiety radiating off the Supreme potently.

“I’d like to go tonight. The sooner the better, and around ten. There’s no need to cause more disruption than normal,” she shrugged, a bit relieved the two relented in the doubts at least verbally. When she listened to their thoughts, she could hear the doubts screaming loudly. That was a confidence boost for sure.

“I’d suggest later. If your location’s right, you could have a chance of running into him if he’s found a victim,” Jane pointed out tilting her head.

“Go after midnight,” Anna suggested directly after Jane spoke.

The other two were right, an earlier time was a gamble. Well, in reality, this whole trip was a gamble. She only nodded though, “Brilliant idea.”

The girls were absolutely correct. This could be fatal, useless, too much of a risk or all of the above. Catherine did her best to suppress the whirling thoughts of what that failure could be though. She had to do something about Henry, and in her mind, knowing the enemy was the first step to beating the enemy.

If they could gain the upperhand by learning more information about Henry Tudor before he gained more intel on them, they’d have the upperhand. So far, nonmagic routes hadn’t gleaned enough information. If she wasn’t desperate, she wouldn’t push less ‘safe’ options for informational purposes.

Truth be told, she was still shaken from the night before, and she was waiting on news from Maria that there’d been another victim. Realizing she’d spaced out for a moment, she shook her head in an attempt to play it off, “I’m going to find Anne. Make sure when we’re gone to hold down the fort, yeah?” she joked with a quiet laugh.

“Yes ma’am,” Anna jested back, accompanied by a nod and smile from Jane. With one final nod, Aragon slipped out of her office to search for Anne. The brunette would most likely be in her room or roaming about the house, considering it was nearing dinner. Luck seemed to be on Catherine’s side when she peeked into Anne’s room to see the other with a book open on her bed.

“Anne?” Catherine called quietly, so as not to startle Anne from her reading.

The brunette glanced up, her eyes wide for a second, until she recognized Catherine in the doorway. “Hm?” she hummed in response closing the book and pulling herself up.

“Mind if I come in first of all?”

“Be my guest,” Anne shrugged with a vague gesture to the room. With a nod, Aragon stepped into the messy room, maneuvering small piles of clothes or the several fallen objects on the floor. “What’s up?” Anne asked as Aragon made her way to sit down at the desk chair.

“I need a favor,” Aragon started with a deep breath.

“Oh?” Anne leaned forward curiously.

Simultaneously, in a pub in the city, two men sat at a corner booth. One had an angular jaw and sandy stubble dotting that same jaw. His grim face, contained smile lines only shown in malice. His accomplice sat across from him. This man’s features were polar the first man’s. His dark hair, dark eyes, and complimenting five o’clock shadow contrasted the light blonde man’s features. The similarities though, sat in the stone cold hollow eyes and in the understated intimidation of his muscular stature.

“You know,” the dark headed man started, “You can’t just keep waiting for them to do something. This wasn’t supposed to take as long as it has. I mean, three years? That’s excessive, even if they’re being wise Henry.”

The newly named Henry shook his head, “They’ll stop being careful soon enough, and that’s when I’ll catch them.”

“You were supposed to get in and take them out,” the second man persisted.

“I know, Thomas, but they were smarter than I anticipated!” his nostrils flared in a flash of irritation. “That’s completely on me though, I will admit. I shouldn’t have underestimated them.”

“At least we know what we know, and we have our inside contact, well if that’s what you call her,” Thomas shrugged, appraising his own words.

“She’s served her purpose, and continues to. She keeps up my wards and gives me information and I don’t kill her,” he shrugged in return as if what he said were the simplest agreement ever.

“Speaking of which, has she turned up anything new?” Thomas asked in curiosity.

“Katherine Howard, the one about a week ago is alive. Anne got her out of there apparently.”

The other man’s eyes lit up in recognition, “Howard?”

Henry narrowed his eyes, “Yeah, you know her?”

Quickly, realizing his sudden interest hadn’t been inconspicuous, Thomas forced himself to sit back, “Heard the name before.”

An obvious lie, but Henry didn’t care to push it. Instead he pushed forward, “Last night was an easy one. She was young, sixteen, and out too late for her own good. If only the others were as easy. God, it still baffles me that Catherine is the leader, and that Anne is alive. Of course now it all makes sense, knowing Jane’s a healer. If only I’d gotten that much out of her that night. I was so close to nipping the problem in the bud with her,” he shook his head, thinking of the drunken night Jane had begun to divulge the London coven’s secrets when he’d been with her.

“And now you have baggage now. What’ll you do with the son once you deal with everyone else?” Thomas asked.

“Eh, haven’t really thought about it. There are merits to getting rid of him with his mother or keeping him. We’ll see how everything pans out, then I’ll deal with it all.” In one statement, Henry Tudor had revealed truly how little he cared for life. He cared for manipulation, ease, and power above all else.

While Thomas definitely was unbothered by murder, the idea of murdering a baby didn’t settle well with him. The kid hadn’t had much of a chance to live. It must have shown on his face because Henry’s face hardened, “You got a problem with that?” he asked carefully, his brow raised.

Forcing his expression back to neutral, Culpeper shook his head. He had more interest in Katherine Howard, even if murdering an infant didn’t sit well. He wouldn’t have a part of it bothered him so much. All he cared about was seeing Katherine again.

“Good. Can you go take care of the body from last night sometime tonight?” Henry continued.

“Always sending me to do your dirty work, eh?” Thomas scoffed. “Yeah, sure.”

#catherine of aragon#six the musical#catherine parr#anne boleyn#anne of cleves#jane seymour#katherine howard

28 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

This is a scene about a man kissing another man.

The other night, I told a man “I’m thinking about what would happen if I leaned in and kissed you”. He was taken aback at first. Got quiet. He mumbled something about how he’d thought of it before, but it doesn’t work for him. Then, he looked at me and said “I could kill you”.

In this scene, I think I can see what that kiss would have meant to him. It would have been painful, terrifying, more than he could handle. What it means to be kissed, to be marked with queerness is pain. It’s loss.

It’ll hurt more than you’ve ever been burned, and you’ll have a scar

Queerness, in a sort of idealized sense, means transgression.

You have to consider the possibility that god does not like you. He never wanted you! In all probability he hates you!

If God is the Father, neither do our lowercase fathers care much for us. Neither the rules of our gods or fathers apply any more, and now we’re out there, beyond good and evil.

It’s only after we’ve lost everything that we are free to do anything

The church hates us, our families disown us, and the world wants to kill us. Our choice is to stay with the pain, to acknowledge the melancholy quality of our lives, the immanence of our death.

Congratulations. You’re one step closer to hitting the bottom

Well, bend over then, and let’s have at it.

The reality that I faced, though, was one that wasn’t this. The person I was talking to was likely not queer, and I was not strong in the way that Tyler was, didn’t have the connection and the shared experience. He didn’t have the desire to push past the pain (which is fine). He felt threatened by it, burned by it, and struck back.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The body is under threat in the city—The cinema is under threat in the city—The digital city is antipathetic to both ...

1.

In early 2016 I was standing in the ballroom of the Duke of Cornwall Hotel in Plymouth (UK), chatting with a kilted Dee Heddon, co-founder with Misha Myers of The Walking Library (see Heddon & Myers 2014), and waiting for a performance of a scabrous Pearl Williams routine by Roberta Mock, author of a key account of walking arts (2009, 7-23). Conversation drifted to films and Dee wondered what kind of resource for wandering a passion for movies might offer.

It was an appropriate space for Dee’s question. The ballroom is on the ground floor of the hotel, which rises to an impressive tower topped by a single room. It was to this room that Roberta’s partner, Paul, and I had gained access on a ‘vertigo walk’ some years previously. We had walked from Paul’s childhood home town of Saltash on the other side of the Hamoaze, a stretch of the River Tamar, into Plymouth. This involved us crossing high above the river gorge on the 1961 road bridge. Although he had crossed this bridge many hundreds of times by car and bus, Paul, susceptible to vertigo like myself, had never walked it before.

Having successfully negotiated the bridge, we sought out all the highest points in the city that we could access. The manager of the Duke of Cornwall led us up winding stairs and opened the room in the tower for us. A telescope stood at a window; above the bed (and this was after 9/11) hung a framed photograph of the twin towers of the World Trade Centre in New York. I might have thought of ‘Wolfen’ (1981), or the anachronistic underwater shot of the twin towers in Tim Burton’s 2001 ‘Planet of the Apes’, or ‘Man on Wire’ (2008) even, but the opening scene of Fulci’s ‘Zombi 2’/Zombie Flesh Eaters’ (1979) was how I immediately cross-referenced through film what I was feeling on coming into the room; to be precise, the moment when the music reaches its climax not for the monster, but for the Manhattan skyline. Flying in the face of Ivan Chtcheglov’s assertion that “[W]e are bored in the city, there is no longer any Temple of the Sun”, in Fulci’s movie solar rays spill from behind the twin towers, just as they have from behind the zombie cadaver. The two monoliths cancel each other out and the movie almost stalls before it can begin; landscape and body equally ruinous.

2.

I want to propose that by systematically drawing on such associations – of the ambience, shape or narrative of particular places with memories of movies – the effectiveness of a certain kind of political and critical walking can be enhanced. Ironically, this walking springs from the dérive of the Lettrists/situationists who, subsequent to their exploratory walking, developed a theory of the ‘Society of the Spectacle’, a deeply negative attitude to the predominance of the visual, and produced anti-art and anti-cinema works like ‘Hurlements En Favour De Sade’ (1952) in which the screen throughout is blank, either dazzling white or dark. While what follows skirts a narrow adherence to the asceticism of later situationist theory, drawing upon the Lettrist/situationist experimentation with art processes recovered in more recent publications such as McKenzie Wark’s trilogy (2008, 2011, 2103), it also implements the orthodox situationist technique of détournement, hacking up and depredating the movies drawn upon and redeploying their images, themes and narratives in ways that are often aggressively at odds with their makers’ intentions.

3.

The body is under threat in the city. The cinema is under threat in the city. The digital city is antipathetic to both. The cinema offers the urban walker a chance to return as an immanent and imaginative body to the city.

Stephen Barber, in considering the turbulent confluence of body, performance, film and digital screens, makes this damning assessment of the contemporary city: “[T]he city’s surface, as a scoured and excoriated environment.... precludes and voids the eruption of performance acts.... forming an exposed medium that is already maximally occupied with such visual Spectacles as digital image-screens transmitting corporate animations, along with saturated icons, insignia and hoardings.... surface has no space for the corporeal infiltration of performance, unless that performance is commissioned.... to fully serve corporate agendas” (2104, 89). Barber’s portrait of urban surface is extreme, but it explains the absurd policing of image-making and the suppression of the most innocuous of non-retail behaviours by mall security guards, the tendency, akin to conspiracy, among consumers to mistake advertising logos for ornament and the strange brutalist sculptural contraptions placed to inconvenience rough sleepers.

When the screen was digitised, the Society of the Spectacle became architectural. A new intensity to the integration of the Spectacle (Debord 1998, 8), beyond and subsuming free market and authoritarian manipulation, now commits it to an invasive, algorithmic pursuit of the preferences of the online majority. An authoritarian redesign of the city, complementing the ‘nudge units’ of its happiness industry, is under way; engineered to encourage the preferences that the Spectacle prefers. This new city space wraps free market around free interiority; then, by scandal-dramaturgy and pseudo-spirituality, it demands a confessional revealing of all things to the Spectacle’s algorithms.