#Bronze Statue Nigeria

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bronze Statue Nigeria

Explore a curated collection of authentic African art at our online store. Discover unique antique pieces, masks, textiles, stools, and woodwork that tell stories of heritage and craftsmanship. Bring the spirit of Africa into your home with our handpicked treasures. Shop now for a cultural journey through timeless arti, Baule mask ivory coast, Baga stool guinea, Kuba textile Congo, Hand carved baga stool guinea , Lega Mask in USA. https://mdafricanart.com/

Badagry, situated in the western tip of Lagos city and about an hour drive from Lagos fundamental land, is the second biggest business town in Lagos State.

The beginning of Badagry could be followed back to the period when individuals lived along the Bank of Gberefu that later brought forth the town of Badagry.

Badagry has a momentous spot throughout the entire existence of Nigeria's excursion to freedom, consequently its well known epithet - the old city. The town, established in the fifteenth 100 years - on a tidal pond, was a critical port in the product of captives to America, during the time of slave exchange Nigeria.

Md african art transcends

African Traditional Tools

Basket in african

Glass bead necklace from Ghana

Bronze Statue Nigeria

Ceremonial beaded Bracelet South Africa

Ceremonial cache sexe from nigeria

Dan Guere Mask from Liberia

Gouro Mask from Ivory Coast

Badagry is situated in a quiet climate to a great extent encompassed by the sea and near Seme line. The town gets bunches of visits, from sightseers to understudies and history darlings who need to investigate the gallery, fascination focuses, and find out about Nigeria's set of experiences.

Vacation destination Focuses IN BADAGRY

A famous hotel community in Badagry is the Murmuring Palms Resort. Possessing 8 sections of land of land, Murmuring Palms Resort is situated in Iworo, Badagry and lies on the Tidal pond, providing you with an ideal perspective on nature. The cool Atlantic breeze, silica sands, palms trees and tweeting birds recognizes it from clamoring urban communities, as it is a spot away from the standard commotion of traffic and raving residents.

It harbors a smaller than usual zoo, pool, various scaled down nurseries and Nigerian carvings and works of art (counting bronze heads of different Yoruba divinities).

There are basic and extravagance facilities for visitors to pick from. The hotel likewise offers nearby and intercontinental foods - Ogbono flavored with Ugu and severe leaf, Spanish paella, coconut shrimps, Cantonese chicken among others.

Very much like other significant vacation spot focuses, it draws in loads of individuals yearly who need some time away to unwind and appreciate nature. What procured Murmuring Palms Resort its notoriety is its closeness to significant vacation spot focus like the slave historical centers, which takes around 20 to 30 minutes' drive.

Past that, another element is the presence of a small exhibition hall called the Legacy room. The scaled down exhibition hall houses relics of slave exchange, for example, - slave chains and pictures of generally significant areas (like the site where Christianity was first taught in Nigeria in 1842).

The Primary designs in Nigeria.

The main essential and optional schooling systems in Nigeria are St Thomas Anglican Elementary School and Badagry Punctuation School.

Fabricated millennia after the principal story building was developed in Nigeria, the structure sitting above the Marina waterfront, worked in 1842 by Fire up Bernard Freeman and different ministers, is frequently alluded to as the main story working in Nigeria.

1 note

·

View note

Text

ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE HEAD OF OBA

THE BENIN KINGDOM

THE LOOTED TREASURES BY THE BRITISH EMPIRE

BLACK HISTORY IS DEEPER THAN SLAVE TRADE

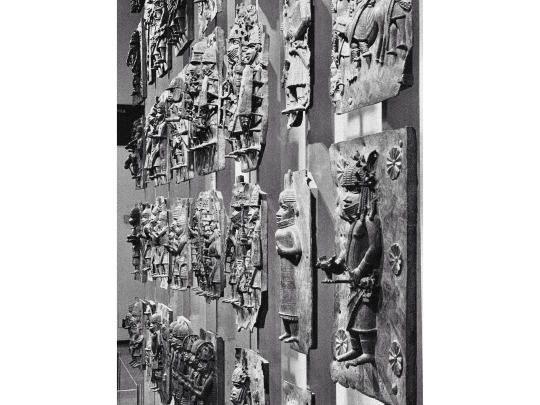

The head sculptures of the Oba of Benin, also known as the Benin Bronzes, are a collection of intricate bronze and brass sculptures created by the Edo people of Nigeria. These sculptures typically depict the reigning Oba (king) of the Benin Empire and were produced over several centuries, with some dating back to the 13th century.

They are renowned for their artistic and historical significance, representing the cultural heritage and power of the Benin Kingdom. These sculptures often portray the Oba wearing coral beaded regalia, symbolizing his divine status and authority.

Many of these artifacts were taken from Benin during the late 19th century by British colonial forces, and they are now scattered in museums and private collections worldwide. There have been ongoing discussions and negotiations regarding their repatriation to Nigeria to restore their cultural heritage.

The head sculptures of the Oba of Benin remain a testament to the rich artistic and historical legacy of the Edo people and the Benin Kingdom.

HOW THE BRITISH STOLE FROM THE EDO TRIBE

1. British Punitive Expedition: In 1897, a British expedition, led by British officials and soldiers, was sent to the Benin Kingdom (in what is now Nigeria) with the stated objective of punishing the Oba of Benin, Oba Ovonramwen, for resisting British influence and trade in the region.

2. Sacking of the Royal Palace: During the expedition, the British forces entered the royal palace in Benin City, where many of these intricate bronze and brass sculptures were housed. The palace was looted, and numerous artifacts, including the Benin Bronzes, were taken.

3. Confiscation and Dispersal: The looted artifacts were then confiscated by the British authorities and later distributed to various individuals, museums, and institutions. Many of these artworks ended up in European museums and private collections.

The theft of the Benin Bronzes remains a contentious issue, as these artworks are considered cultural treasures of the Edo people and Nigeria as a whole. There have been ongoing discussions and demands for the repatriation of these artifacts to Nigeria, which has gained momentum in recent years as part of broader efforts to address historical injustices related to colonial-era looting.

The head sculptures of the Oba of Benin, like many traditional African artworks, hold deep symbolic significance within the context of the Benin Kingdom and its culture. Here are some of the key symbols and meanings associated with these sculptures:

1. Royal Authority: The Oba's head sculptures symbolize the authority and divine status of the reigning monarch, who was regarded as a sacred figure in Benin society. The elaborate regalia, such as coral beads and headdresses, worn by the Oba in these sculptures signifies his royal and spiritual power.

2. Ancestral Connections: The sculptures often depict the Oba with distinctive facial scarification patterns and detailed facial features. These features can represent specific ancestors or dynastic connections, emphasizing the Oba's lineage and connection to past rulers.

3. Historical Record: The sculptures also serve as historical records, documenting the appearance and regalia of the Oba during their reigns. This provides valuable insights into the history and evolution of the Benin Kingdom over the centuries.

4. Spiritual Protection: Some sculptures may incorporate elements like beads and cowrie shells, which were believed to have protective and spiritual qualities. These elements were worn by the Oba not only for their aesthetic value but also for their symbolic protection.

5. Cultural Identity: Beyond their specific symbolic meanings, the head sculptures are integral to the cultural identity of the Edo people and the Benin Kingdom. They represent the rich artistic traditions and heritage of the kingdom and its rulers.

It's important to note that the symbolism of these sculptures is deeply rooted in the cultural and historical context of the Benin Kingdom, and their interpretation can vary among different individuals and communities.

#life#animals#culture#aesthetic#black history#history#blm blacklivesmatter#anime and manga#architecture#black community#black heritage

832 notes

·

View notes

Text

IRL Wakanda: The Kingdom of Benin

The Kingdom of Benin was practically a futuristic utopia in Nigeria for hundreds of years. It was a powerful center of trade and culture.

They created what is (currently) known as the first pre-modern street lights. (used by traders at night)

It had a collection of earthen walls that were longer than the Great Wall of China.

They were BEYOND expert metalworkers. They crafted bronze into masks and statues that are hard to make even with 21st Century tools. They were EXTREMELY complex and advanced for the time period.

When Britain threatened them, they basically told them to fuck off and when Britain first attacked (with an assassination squad to kill Benin's King), they got their asses handed to them. The Kingdom of Benin had a formidable (to put it lightly) army.

youtube

#history#african history#black history#nigeria#the kingdom of benin#benin#africa#british history#britian#england#politics#world politics#wakanda#marvel#mcu#marvel cinematic universe#avengers#black panther#wakanda forever#STEM#technology#metalworking#metalwork#sculpture#bronze#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art Theft, Cultural Heritage, and European Museums: The Nexus of History and Identity

The theft of art and cultural artifacts is an enduring issue that has shaped global history, leaving profound implications for cultural heritage and ethnic identity. Nowhere is this dynamic more visible than in the history of European museums, which have often become repositories of artifacts obtained under controversial circumstances. The interplay between art theft, the consolidation of museum collections, and the assertion of ethnic and cultural identity reveals a complex narrative of power, colonialism, and the enduring struggle for cultural reclamation.

The Roots of Art Theft in European History

Art theft is not a modern phenomenon. Throughout history, conflicts and conquests have been accompanied by the appropriation of cultural treasures. During the Roman Empire, for example, victorious generals often seized statues, mosaics, and other artworks from subjugated peoples to symbolize their dominance. This tradition continued into the Napoleonic era, as Napoleon Bonaparte looted European and Middle Eastern artifacts to fill the Louvre in Paris, presenting himself as the cultural custodian of Europe.

However, the most significant phase of art theft coincided with European colonial expansion from the 16th to the 20th centuries. As European powers extended their reach across Africa, Asia, and the Americas, they appropriated vast amounts of cultural heritage under the guise of exploration and scientific study. These artifacts were often transported to Europe, where they formed the foundation of renowned museums such as the British Museum in London, the Louvre in Paris, and the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

European Museums and the Legacy of Colonialism

Many of Europe’s major museums are emblematic of this legacy. The British Museum, for example, houses the Parthenon Marbles, Benin Bronzes, and Rosetta Stone—iconic artifacts acquired under circumstances widely considered exploitative. Similarly, the Louvre boasts artifacts like the Venus de Milo and treasures from ancient Egypt, many of which were removed during colonial expeditions or military campaigns.

These collections were not just about artistic appreciation; they served as symbols of imperial power. By displaying the cultural achievements of other civilizations, European nations sought to assert their superiority as custodians of global heritage. Museums became institutions where national pride and imperial dominance intertwined, presenting a curated narrative of history that often marginalized the voices and rights of the cultures from which these artifacts originated.

Cultural Heritage and Ethnic Identity

Art and cultural artifacts are deeply tied to identity, serving as tangible expressions of history, religion, and collective memory. When artifacts are removed from their original context, it disrupts this connection, eroding the ability of communities to engage with their heritage. This loss is particularly poignant for formerly colonized nations, where stolen artifacts are seen as emblematic of broader historical injustices.

For many ethnic groups, the reclamation of cultural artifacts is central to the process of healing and reclaiming their identity. The demand for the return of the Benin Bronzes to Nigeria, for example, is not just about restoring physical objects but about reasserting control over a history that was forcibly interrupted. Similarly, Greece's campaign for the return of the Parthenon Marbles is intertwined with its national identity and pride in its classical heritage.

The Ethical Role of European Museums

In recent decades, the ethics of artifact ownership have come under increasing scrutiny. European museums face growing calls to repatriate artifacts to their countries of origin. While some institutions, like the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, have begun engaging in dialogue about the provenance of their collections, many remain reluctant to part with high-profile objects, citing reasons such as conservation concerns and their role in educating global audiences.

However, these arguments are increasingly challenged by advocates of repatriation, who argue that true education and preservation must involve respecting the rights of source communities. The return of artifacts, such as the recent decision by the Smithsonian Institution to repatriate Benin Bronzes, demonstrates that collaboration between museums and source nations is both possible and beneficial.

Balancing Universalism and Cultural Identity

A central tension in this debate lies in the concept of universal museums. Proponents of universalism argue that museums serve as spaces where people from all backgrounds can encounter the diversity of human achievement. This vision, however, is often at odds with the desires of source communities, who view these artifacts as integral to their cultural and ethnic identity.

The challenge lies in balancing these perspectives. Collaborative initiatives, such as long-term loans, co-curated exhibitions, and digital repatriation, offer potential solutions. By fostering partnerships, European museums can maintain their educational mission while honoring the rights and dignity of source communities.

The history of art theft and cultural heritage is inseparable from the story of European museums and their role in shaping ethnic identity. While these institutions have long served as symbols of national pride and imperial dominance, they must now navigate a changing landscape that demands accountability and inclusivity. By addressing their colonial legacies and embracing ethical practices, European museums have an opportunity to transform themselves into spaces of reconciliation and shared humanity. Through such efforts, the stolen legacies of the past can become a bridge to a more equitable future.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Le Grand Egyptian Museum figure en tête de la liste des nouveaux musées les plus importants en 2025 établie par le Guardian.

Sous le titre « Pharaons, masques et bateaux de l'âge de bronze : Six nouveaux musées remarquables dans le monde en 2025 », le journal The Guardian fait la lumière sur les nouveaux musées remarquables qui ouvriront dans le monde en 2025, plaçant le Grand Egyptian Museum en tête de liste et lui consacrant l'image principale du rapport.

De l'impressionnant centre culturel Yoruba de Lagos, au Nigeria, au très attendu Grand Egyptian Museum de Gizeh, l'année 2025 offre une abondance de nouveaux musées. Vous pouvez les visiter grâce aux circuits en Égypte proposés par Cairo Top Tours. Le Guide de voyage de l'Égypte recommande vivement de visiter les musées en Égypte. Cette expérience vous permettra d'en apprendre davantage sur les pharaons, les reines et les souverains d'Égypte qui se caractérisaient par leur force et leur sagesse.

Les visiteurs ont eu l'occasion de visiter les principales galeries lors d'une ouverture restreinte, à titre d'essai pour ce projet longtemps retardé, qui a déjà coûté plus d'un milliard de dollars et qui sera le plus grand musée archéologique du monde. Ils ont découvert les dieux et les déesses de l'ancienne religion égyptienne, qu'ils ne vénéraient pas au hasard.

Selon elle, un monument massif en granit rouge représentant Ramsès II, qui a vécu de 1279 à 1213 avant J.-C., accueille les visiteurs. La statue, qui a été placée sur l'une des plus grandes places du Caire en 1955 et y est restée pendant 50 ans, malgré les vibrations des trains qui passent et la pollution de la circulation, est devenue un spectacle bien connu en Égypte.

La conception intérieure et extérieure du musée est fortement influencée par les pyramides de Gizeh, que l'on peut voir du haut du grand escalier de six étages. Des colonnes de granit, des obélisques, des sphinx, des sarcophages et des sculptures royales sont exposés dans les douze salles principales. Ces salles couvrent une vaste période allant de la préhistoire à l'époque romaine, avec notamment la statue de la reine Hatchepsout agenouillée.

Dans les musées, on trouve également des statues de dieux comme Ptah, le dieu de la création et des artisans. Sérapis est également l'un des dieux les plus célèbres dont le culte était très répandu. Vous découvrirez l'histoire d'Isis et d'Osiris, qui revêtaient une importance religieuse pour les anciens Égyptiens. Le musée possède également une statue du dieu Bès, dieu de l'accouchement, sous la forme d'un nain.

Dans les musées égyptiens, comme le Musée égyptien du Caire, on trouve des statues de Sobek et des poteries qui illustrent le culte et la mythologie du dieu. Quant au dieu Aton, le musée contient de nombreux artefacts qui mettent en lumière le culte d'Atun, et représente une part importante des collections des musées égyptiens. Des statues et des objets illustrant le rôle d'Atoum dans la création sont également exposés dans les musées égyptiens. Enfin, la déesse Sekhmet est représentée par de nombreux objets qui permettent aux visiteurs de comprendre la place importante qu'elle occupe dans la religion égyptienne ancienne.

0 notes

Text

Reclaiming Tradition: How Hair Beads Connect Us to Our History

"The wearing of hair jewelry is a beauty practice that long predates our present-day interpretations. "Just about everything about a person's identity could be learned by looking at their hair," Lori Tharps, co-writer of the book Hair Story told BBC Africa about early African braiding practices.

These styles weren't just about aesthetics and functionality. They were also markers of social standing. In Ancient Egypt people commonly wore alabaster, white glazed pottery or jasper rings in wigs, depending on which materials were available locally, they were symbols of status and authority, with those of high class ranking, let's say a young Cleopatra, using them to signify wealth and status.

Hair adornment played a similar role in early West African civilizations. In many communities braid patterns were used to identify marital status, social standing and even age. In present-day Cameroon and Côte d'Ivoire hair embellishments were used to denote tribal lineage. In Nigeria coral beads are worn as crowns in traditional wedding ceremonies in various tribes. These crowns are referred to as okuru amongst Edo people, and erulu in Igbo culture. In Yoruba culture, an Oba's Crown, made of multicolored glass beads, is worn by leaders of the highest authority.

Hair ornaments have been worn by Fulani women across the Sahel region for centuries, who adorn intricate braid patterns with silver or bronze discs, often passed down from generations.

Early uses of hair jewelry were also seen in East Africa. Habesha women from the northern regions of Ethiopia and Eritrea drape cornrow hairdos with delicate gold chains that usually fall past the forehead when in traditional garb. Members of the Hamar tribe in the Southern Omo Valley are known to wear their hair in cropped micro-dreadlocks dyed with red ochre and use flat discs and cowrie shells to accentuate styles.

Some of the earliest beads to be used as adornment were found in 2004 at the Blombos Cave site near Cape Town. They were made from shells and date back 76,000 years."

0 notes

Text

Essay from ARTH 10

Essay Prompt #15: Elgin Marbles

Taylor Polston ARTH 10 Course 03

A source of controversy in the art world involves ancient art that resides in countries that are not of their origin. For example, art like the Elgin Marbles of Greece, that currently reside in the United Kingdom. In recent times there has been much more of a call to return art works back to their culture and country of origin. Repatriation is the term used to refer to reuniting the art with its home country. An example of repatriation would be the Paris Quai Branly museum returning bronze statues to Nigeria that had originally been looted in 1892 (Porterfield). Although many works are being returned, there are also many that are not. The question of “should they be returned,” is an ongoing argument that doesn’t seem to have an exact end in sight.

One major source of controversy is the Elgin Marbles. In the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Empire had control over Greece. A British Ambassador and Earl of Elgin, Thomas Bruce, decided he wanted to remove marble sculptures from the Parthenon. So, with permission from the Ottomans’, Bruce made the order to remove the sculptures and have them sent back to England. Since the Parthenon was being used by the military at the time, Bruce claimed to be protecting the serving art works from ruin by removing them to be preserved (Stokstad). He was immediately criticized, however, those against him became silent once he laid out his arguments. Eventually, the marble

works, now called Elgin Marbles, were purchased by the British Crown for about thirty five thousand pounds (“Elgin Marbles”).

Throughout recent times, the Greek government has made ongoing attempts to have these marbles retuned. However, the United Kingdom has continuously refused to participate in the repatriation of these works, claiming they are preserving them. To this day they can be viewed at the British Museum in London. Although Greece does not have possession of the authentic work, they do have a plaster cast of the marble work on display at the Acropolis Museum in Athens. This museum can be found next to the Elgin Marbles original home. The Parthenon (“Elgin Marbles”).

It is hard to say if Thomas Bruce’s true intent was to preserve the marbles instead of leaving them in a war zone, however, Greece is no longer a war heavy country. The United Kingdom stating they are preserving them doesn’t seem like a good enough argument to not return them to Greece. This is because Greece also has the means to preserve and protect these art works if they were to be returned. It is also assumed they already have a location for them, as they would probably replace their plaster counterparts.

In terms of other works in similar circumstances, it may makes sense to not return items that are important to art and culture history. This is only if the country they originally hail from does not have the ability to properly care for the works and the work would become destroyed if returned. Some may argue that if they get ruined in their home country that is that countries arrogative because they won them. However, any see art, even those from foreign countries, s something owned by all and not just

specific countries. This is because art not only shows the story of a countries future but gives people a glimpse into history that wasn’t explicitly recorded. It can also be argued that art from various countries should be found in museums so that people from various cultures can enjoy and learn about other cultures. However, it would also be a good middle ground for agreements to be made with the country of origin so that the works don’t feel stolen but instead their “home” has been agreed upon or at least have temporary placement.

In regards to the Elgin Marbles, there doesn’t seem to be a valid reason why they should to be returned to Greece. This cannot be said for all artworks, as it may be poor judgement to return art to war torn countries who don’t have the ability to take of them. Repatriation will probably always be a controversial topic because of all the wars and conquering of the past and what there will probably be more of in the future.

Works Cited

“Elgin Marbles.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 24 Mar. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Elgin-Marbles.

Porterfield, Carlie. “Europe's Museums, Collectors Are Returning Artifacts to Countries of Origin amid Fresh Scrutiny.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 9 Nov. 2022, https:// www.forbes.com/sites/carlieporterfield/2021/10/27/europes-museums-collectors- are-returning-artifacts-to-countries-of-origin-amid-fresh-scrutiny/? sh=11b247d7675b.

Stokstad, Marilyn, and Michael Watt Cothren. Art History, 5th ed., Pearson, Boston, 2014, p. 133.

0 notes

Photo

A bronze statue depicting a scantily-clad female character from a 19th century poem has sparked debate in Italy. Some politicians called the figure “an offense to women” and demanded that it be removed. The statue was unveiled in the town of Sapri in southern Italy over the weekend, but was quickly met with backlash. (📸: Italia2TV) Follow @joseifworldblog.page for more beautiful stories #italian #worldnews#cbstv#bbcnews #aljazeera#washingtonpost #universal #joseifworlrldblog #blm #archive #news #instagram #explorepage #instafollow #repost #statue#bronze#nbcnews#nigeria #exploreeverything#joseifworld#cnnnews #petemcbride #rodneyking #unitedstates #instablog #instablog9ja # https://www.instagram.com/p/CUZGnzxobm9/?utm_medium=tumblr

#italian#worldnews#cbstv#bbcnews#aljazeera#washingtonpost#universal#joseifworlrldblog#blm#archive#news#instagram#explorepage#instafollow#repost#statue#bronze#nbcnews#nigeria#exploreeverything#joseifworld#cnnnews#petemcbride#rodneyking#unitedstates#instablog#instablog9ja

0 notes

Text

Elég gyenge a címadás a klasszikus óta

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Elizabeth Gregory

“Made between 447BC and 438BC, under the supervision of the architect and sculptor Phidias, the marbles were originally part of the Parthenon temple in Athens. The story goes that the Ottoman Empire gave Lord Elgin the go-ahead to extract some of the statues in 1801. The validity of the permission is seen as dubious at best and today Greece is calling for the return of its ancient artefacts.”

Continue reading | Login required

#classics#tagamemnon#tagitus#history#ancient history#art#art history#artefacts#antiquities#contentious objects#theft#looting#imperialism#western museums#parthenon marbles#rosetta stone#Nefertiti Bust#Benin bronzes#Hoa Hakananai’a#illegal acquisition#mediterranean#greece#egypt#nigeria#easter island#repatriation#i firmly believe repatriation is the only appropriate outcome for these items and many more#this is just a list#rather than a long think piece#but it's still though provoking

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bronze Statue from Nigeria

Explore a curated collection of authentic African art at our online store. Discover unique antique pieces, masks, textiles, stools, and woodwork that tell stories of heritage and craftsmanship. Bring the spirit of Africa into your home with our handpicked treasures. Shop now for a cultural journey through timeless arti, Baule mask ivory coast, Baga stool guinea, Bronze Statue from Nigeria , Kuba textile Congo, Hand carved baga stool guinea , Lega Mask in USA. https://mdafricanart.com/

The Slave Historical centers

However there are a few motion pictures that have attempted however much as could reasonably be expected to portray what the Slave Exchange Time resembled, one wouldn't actually comprehend how disheartening and close to home the Period was until you go on an outing to one of the slave exhibition halls, similar to those in Badagry. In the event that you are not in that frame of mind for a close to home margin time or not an admirer of history, you might need to skirt the excursion to the slave historical centers.

Bronze Statue Nigeria

Ceremonial beaded Bracelet South Africa

Ceremonial cache sexe from nigeria

Dan Guere Mask from Liberia

Gouro Mask from Ivory Coast

Shield from South Africa

Ceremonial cache sexe

Bronze Statue from Nigeria

Baga Stool from Guinea

Kuba textile from Congo

With around 4 slave historical centers present in Badagry, they all assist with safeguarding the social legacy and remind visiting travelers the sufferings individuals impacted by the slave exchange went through. The slave exchange exhibition halls incorporate - Badagry Legacy Gallery, Seriki Faremi's Brazilian Baracoon, Vlekete Slave Market and Mobee Illustrious Family Slave Historical center.

However the vast majority of these galleries have somewhat changing anecdotes about their originators, they all offer the very anguishing encounters of slaves that have been held hostage in the rooms. On your visit to every one of these galleries, you will be relegated a local escort who will make sense of in extraordinary subtleties the story behind each room and item.

Vlekete Slave Market

This market was laid out in 1502, it filled in as a gathering point for European slave shippers and African brokers. This market was as around then the biggest and generally populated, offering near 900 slaves each week. Slaves were typically actioned for products like iron bars, reflect, dry gin, bourbon, firearm and different things.

Seriki Faremi's Brazilian Baracoon

Seriki Faremi William Abass Baracoon comprises of 40 small rooms and each room was utilized as a cell to hold 40 slaves. A few different things in plain view incorporate, created iron chains of different sizes and shapes. The more modest chains are utilized on the offspring of the captives to keep them from upsetting their folks while they chipped away at the estate.

Seriki Faremi was a man who for the most part traded slaves for housewares and different things as the Brazilians that time don't perceive cowries as cash.

The possibility of Bosses utilizing Umbrella traces all the way back to the pilgrim period. Seriki's popular yellowish weighty umbrella is said to have cost him 40 slaves and different things, for example, porcelains, cups and gramophone records, each cost him 10 slaves.

The Seriki's garments, archives of exchanges and the staff of office introduced to him by the provincial bosses are as yet present at the scene.

Badagry Legacy Historical center

It is a story building situated in the focal point of the memorable traveler town of Badagry (in the Boekoh quarters region, known as "Adugbo Oyinbo" in nearby Yoruba vernacular, signifying "neighborhood of white men"). It houses the relics, records and culture of the Badagry public. Things in the exhibition hall traces all the way back to pre-slave time, slave period and post slave time. The African story didn't start with slave period and this historical center shows it; as you will track down the way of life and records of individuals who possessed Badagry well before the pioneers came and made a huge difference.

There are 8 exhibitions generally named at various times of the slave period in the Badagry Historical center. The Early on Exhibition, which is the first you will see as you enter the historical center, has a sculpture of a man with broken chains.All displays make sense of how slaves are caught, sold, rebuffed, moved and in particular, genuine legends who battled for the nullification of slave exchange are in plain view in the exhibition.

Mobee Illustrious Family Slave Historical center

Very much like the other slave historical centers, it contains comparative articles the slave dealers used to hold slaves hostage during the slave period.

One novel thing found in this exhibition hall is the Cannon firearm, which is generally fired three times each day - in the first part of the day as a sign the slaves are going to the homestead, at night to tell the slaves are returning from the ranch and later in the evening, to advise all captives to remain inside, anybody found external after this advance notice is normally sold into servitude.

One fascinating truth anyway is, while the pioneer behind this slave gallery helped slave exchange, his child, Boss Sumbu Mobee worked with the annulment of slave exchange.

Badagry Slave Course: Final turning point

To get over to the "Final turning point", you should enlist a boat from the breakwater where slaves were removed 4:00am consistently to the opposite side to deal with the manor or be sent to their last processes abroad. Lines of coconut trees established by the slaves are still along the shore where you will take a boat.

Along the streets, white stones are organized to check the specific course the slaves strolled on, binded by shackles in a solitary document.

Through the excursion to the "Final turning point", you will see a well and near a milestone peruses, "Unique Spot, Slaves Otherworldly Lessening Great", worked by every one of the bosses in Badagry managing on slave business who met up around then to enchant in the well, a sort of dark sorcery which brings neglect. No one has drank from this well in more than 600 years and the rainbow looking shadow cast over the water will make you keep thinking about whether the spell is as yet strong.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ben Enwonwu: The Nigerian artist who made a bronze sculpture of the Queen Elizabeth II

Ben Enwonwu: The Nigerian artist who made a bronze sculpture of the Queen Elizabeth II

The year was 1956, and there was much fanfare and anticipation for Queen Elizabeth’s first visit to Nigeria. The young monarch was just a few years into her reign and making a highly anticipated visit to the West African country, which had yet to become a republic. Ahead of her arrival, famed Nigerian artist Ben Enwonwu received a royal commission to commemorate her visit with a statue, which…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

The art dealer, the £10m Benin Bronze and the Holocaust

Countless historic artefacts were looted from around the world during the colonial era and taken to Europe but there is now a growing campaign to return them. Among the most famous are the Benin Bronzes seized from modern-day Nigeria. Barnaby Phillips finds out about one family's dilemma.

One morning in April 2016, a woman walked into Barclays Bank on London's exclusive Park Lane, to retrieve a mysterious object that had been locked in the vaults for 63 years.

Attendants ushered her downstairs. Three men waited upstairs, perched anxiously on an uncomfortable sofa, watching customers go about their business.

Twenty minutes later the woman appeared, carrying something covered in an old dishcloth. She unwrapped it, and everyone gasped.

A youthful face cast in bronze or brass stared out at them. He had a beaded collar around his neck and a gourd on his head.

The men, an art dealer called Lance Entwistle and two experts from the auctioneers Woolley and Wallis, recognised it as an early Benin Bronze head, perhaps depicting an oba, or king, from the 16th Century.

It was in near-immaculate condition, with the dark grey patina of old bronze, much like a contemporary piece from the Italian Renaissance. They suspected it was worth millions of pounds. The bank staff quickly led them into a panelled room, where they placed the head on a table.

The woman who went down into the vaults is a daughter of an art dealer called Ernest Ohly, who died in 2008.

I have chosen to call her Frieda and not reveal her married name to protect her privacy.

Ernest's father, William Ohly, who was Jewish, fled Nazi Germany and was prominent in London's mid-century art scene.

William Ohly lived "at the nexus of culture, society and artists", says Entwistle.

His "Primitive Art" exhibitions attracted collectors, socialites, and artists such as Jacob Epstein, Lucian Freud, Henry Moore, Francis Bacon, Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell.

He died in 1955. Ernest Ohly inherited his love of art, but was a more reserved character.

"A very, very difficult man to know. He didn't let anything out. You did not know what he was thinking," said Entwistle.

Ernest Ohly's death provoked a ripple of excitement at the lucrative top end of the ethnographic art world. He was rumoured to have an extensive collection. His statues from Polynesia and masks from West Africa were auctioned in 2011 and 2013. And that, dealers assumed, was that.

But his children knew otherwise. In old age, he had told them he had one more sculpture. It was in a Barclays safe box and not to be sold, he specified, unless there was another Holocaust.

In 2016 matters were taken out of the children's hands. Barclays on Park Lane was closing its safe boxes; it told customers to collect their belongings.

I met Lance Entwistle in 2019, in his library lined with books on African sculpture. His website said his company has been "leading tribal art dealers for over 40 years".

"Tribal art" is a term that Western museums now avoid, but is still common in the world of auctions and private sales.

I was bowled over. It was beautiful, moving and its emergence from obscurity was so exciting"Lance Entwistle

Art dealer on the "Ohly head" sold to a collector for £10m

Entwistle has rarely been to Africa, and never to Nigeria, but he's well connected. The British Museum, the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris and the Metropolitan in New York have all bought pieces from him.

I asked him how he had felt when Frieda pulled the cloth away from the Benin Bronze head in the bank.

"I was bowled over," he said. "It was beautiful, moving, and its emergence from obscurity was so exciting. I'm very used to being told about a Benin head, a Benin plaque, a Benin horse and rider. Generally I'm not excited because 99 times out of 100 they're fake, and often the remaining 1% has been stolen."

Provenance is everything in Entwistle's world. This time, thanks to the Ernest Ohly connection, he was confident he was dealing with a bona fide piece.

He told Frieda the Benin Bronze head was significant and unusual, and convinced her to take it home in a taxi, to her terraced house in Tooting, south London.

The Benin Bronzes were brought to Europe in the spring of 1897, the loot of British soldiers and sailors who conquered the West African kingdom of Benin, in modern day Nigeria's Edo state.

Although they are called Benin Bronzes, they are actually thousands of brass and bronze castings and ivory carvings. When some were displayed in the British Museum that autumn, they caused a sensation.

Africans, the British believed at the time, did not possess skills to produce pieces of such sophistication or beauty. Nor were they supposed to have much history.

But the bronzes - some portrayed Portuguese visitors in medieval armour - were evidently hundreds of years old.

They were our documents, our archives, the 'photographs' of our kings. When they were taken our history was exhumed"Victor Ehikhamenor Nigerian artist about the Benin Bronzes

Benin had been denigrated in British newspapers as a place of savagery, a "City of Blood". Now those newspapers described the Bronzes as "surprising", "remarkable" and admitted they were "baffled".

Some of these bronzes are still owned by descendants of those who pillaged Benin, while others have passed from owner to owner.

Victor Ehikhamenor, an artist from Edo state, told me the bronzes were not made only for aesthetic enjoyment.

"They were our documents, our archives, the 'photographs' of our kings. When they were taken our history was exhumed."

But as their value in the West has increased, they've also become prestige investments, held by the wealthy and reclusive.

London auction sales tell the story. In 1953, Sotheby's sold a Benin Bronze head for £5,500. The price raised eyebrows; the previous record for a Benin head was £780.

In 1968 Christie's sold a Benin head for £21,000. (It had been discovered months earlier by a policeman who was pottering around his neighbour's greenhouse and noticed something interesting amidst the plants).

In the 1970s, "Tribal Art" prices soared, and Benin Bronzes led the way. And so it went on, all the way to 2007 when Sotheby's in New York sold a Benin head for $4.7m (£2.35m).

Entwistle kept an eye on that 2007 sale. The buyer, whose identity was not publicly revealed, was one of his trusted clients.

Nine years later, presented by Frieda with the challenge of selling Ernest Ohly's head, Lance knew where to turn.

"It was the first client I offered it to, which is what you want, there was no need to shop around," he said.

There was only a minor haggle over price. The client, Entwistle insisted, was motivated by his love of African art.

"He will never sell, in my view." Whoever he is, wherever he is, he paid another world record fee.

The "Ohly head", as Entwistle calls it, was sold for £10m - a figure not previously disclosed.

If you envisaged the woman who sold the world's most expensive Benin Bronze, you might not come up with Frieda.

We met in the Tate Modern gallery, overlooking the Thames. She had travelled from Tooting by underground. She is a grandmother, with grey close-cropped hair and glasses. She used to work in children's nurseries, but is retired.

"My family is riddled with secrets," she said. "My father refused to speak about his Jewish ancestry."

She did her own research on relatives who were killed in Nazi concentration camps. Ernest Ohly was haunted, "paranoid", says Frieda, by the prospect of another catastrophe engulfing the Jews.

Six million Jews were murdered during the Holocaust - and, according to the Jewish Claims Conference, the Nazis seized an estimated 650,000 artworks and religious items from Jews and other victims.

Ernest Ohly distrusted strangers and lived in a world of cash and secret objects. He kept a suitcase of £50 notes under the bed.

"Ernie the Dealer" was the family nickname. The children grew up surrounded by art. But by the end he was tired of life.

His house was chaotic, his Persian rugs infested with moths. The family found the suitcase of banknotes but discovered they were no longer legal tender.

Ernest Ohly may have let things slide, but he had been a formidable collector.

"He and my grandfather never went to Africa or the South Pacific, but got their knowledge from being around objects," said Freida.

"There was a whole group of European dealers in London, in the 1940s through to the 1970s."

The British Empire was ending, and the deaths of its last administrators and soldiers brought rich pickings.

"I never understood why my father was so interested in reading obituary pages. The Telegraph, the Times, really studying them. If they were Foreign Office, armed forces, anything to do with Empire, he wrote to the widows."

Ernest Ohly listed his buys in ledger books. That's how Entwistle found what he was looking for: "Benin Bronze head... Dec 51, £230" from Glendining's - a London auctioneers where he also bought coins and stamps.

In today's money, that is just over £7,000. In other words, a substantial purchase. But Ernest Ohly knew what he was doing. He had a steal. He put the head in the safe box in 1953, and it stayed there until 2016.

"It was like a lump of gold," said Frieda. The windfall was not quite as large as it might have been.

Ernest Ohly's affairs were a mess, and the taxman took a substantial amount. Still, Frieda says, she can sleep easy now. The Benin head bought care for her family, and property for her children.

Frieda is married to a man of Caribbean descent - and her son is a journalist.

A few years ago he wrote an article about how the Edo - the people of the Benin Kingdom - tried to stop the sale at Sotheby's of a Benin ivory mask.

In fact, although he did not know this, it was a mask that his great-grandfather, William Ohly, displayed at his gallery in 1947.

The article described Edo outrage that the family who owned the mask - relatives of a British official who looted it in 1897 - should profit from what they regarded as theft and a war crime.

Frieda is too intelligent and sensitive not to appreciate the layers of irony behind her story. She had followed the arguments about whether the Benin Bronzes should be returned to Nigeria.

Britain has laws to enable the return of art looted by the Nazis, but there is no similar legislation to cover its own colonial period.

"Part of me will always feel guilty for not giving it to the Nigerians… It's a murky past, tied up with colonialism and exploitation."

Her voice trailed off.

"But that's in the past, lots of governments aren't stable and things have been destroyed. I'm afraid I took the decision to sell. I stand by it. I wanted my family to be secure."

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-56292809?utm_source=pocket-newtab

0 notes

Text

26th April: Tutorial and Visit to the British Museum

Tutorial

Due to a COVID among faculty members, we had to meet our tutor via Teams for the first session. Regardless, it was a great session for constructive thought, and it assisted me in considering my next actions. I brought up the progress of the written portion of my project and was eager to discuss it with my tutor and support team member via Google docs.

Written work from this week can be accessed here.

During the session, I mentioned that I have been seeking more effective ecological frameworks that address the issue of object accumulation. I brought up minimalism in particular, as it is a framework and lifestyle choice that is directly against accumulation, yet my tutor seemed to be sceptical of minimalism. I believe I must investigate minimalism as a discipline more since, as my tutor mentioned, not everyone can be minimalistic; it is a lifestyle choice that is still inaccessible to a majority of people. Additionally, it was great to be paired with someone who was researching a related subject; I have written about sustainability and humanitarian emrgencies in the fashion and textiles industry, and she is undertaking a similar project proposal that examines consumer guilt. After the meeting, my team member and I started working on a Miro board, which I consider a great method to communicate and showcase our progress.

A snippet of our board from later that May...

The British Museum

I then decided to visit the British Museum as a source of inspiration. However, I soon came to realise objects of harm may be found almost anyplace, including our museums. As I visited the Africa section, where I came upon the Benin Bronzes. These exquisite bronze-cast statues have been in production since the 16th century, yet many of the original bronzes were looted during the Scramble for Africa by the colonisers of Benin (now present-day Nigeria). Despite the fact that the British Museum makes its questionable past apparent on a plaque alongside the bronzes, I subsequently learned that the British Museum continues to disregard Nigeria's requests to return its national and cultural artefacts. As well as that, I visited the Gebelein Man, otherwise known as Ginger. It was quite surreal to see a human corpse lying, surrounded by ceramics as a form of exhibit. Simply stated, it enabled me to reflect on the concept of an object and how, unsettlingly, our use of objects has desensitised us to other humans.

Benin Bronzes. (2022). The British Museum, Africa. Public exhibit.

Gebelein Man. (2022). The British Museum, Ancient Egypt. Public exhibit.

0 notes

Photo

@worldblog.page Hollow bronze sculpture. #archoskar The 'Cannot Let Go'. Created by Tong-Liang Hsieh (2001). Located in Taichung, Taiwan. Photo by Ching-Hung Art Space. . "Better than a thousand hollow words, is one word that brings peace." — Buddha. #architectureoskar Follow @worldblog.page for more beautiful stories😊 #hollow #bronze#archive#channel#naijanews #sculpture#sculpture#everest#instagram #buddha#washingtonpost #blm#aljazeera #joseifworld #cnnnews#petemcbride #BBCNews#unitednations #instafollow #reelsinstagram#unitedstates#updates #naturephotography #earthfocus #status #Happening #Nigeria https://www.instagram.com/p/CXS9s9CIkNK/?utm_medium=tumblr

#archoskar#architectureoskar#hollow#bronze#archive#channel#naijanews#sculpture#everest#instagram#buddha#washingtonpost#blm#aljazeera#joseifworld#cnnnews#petemcbride#bbcnews#unitednations#instafollow#reelsinstagram#unitedstates#updates#naturephotography#earthfocus#status#happening#nigeria

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

institutions return African artefacts

A Cambridge University college has handed over the statue of a bronze cockerel looted by British colonial forces during its invasion of Benin in 1897 to Nigerian officials. The statue, locally called ‘Okukur’, was given to Jesus College in 1905 by the father of a student. The Premium Times reports that the college's Legacy of Slavery Working Party in 2019 concluded that the cockerel ‘belongs with the current Oba at the Court of Benin’. College official Sonita Alleyne said ‘it's a momentous occasion’ and ‘the ‘right thing to do’. Information Minister Lai Muhammad said the Nigerian Government will use all ‘legal and diplomatic instruments’ to demand the return of Nigeria's stolen artefacts and cultural materials worldwide. In March, the University of Aberdeen also said it will return a Benin Bronze to Nigeria, becoming the first institution to do so more than a century after Britain looted the sculptures.

And the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology is set to return historic artefacts to the Uganda National Museum in Kampala. Items were collected and donated to the museum by the late British anthropologist and missionary John Roscoe from the Anglican Missionary Society. The Monitor reports that the museum holds about 1 400 separate ethnographic objects from Uganda, many of them acquired by Roscoe. The project team will select a set of artefacts from the museum and repatriate them to Uganda by the end of 2022, conduct research on their history and provenance, and exhibit them in the Uganda Museum in late 2023. Makerere University graduate students will assist with researchers.

A statue of African explorer HM Stanley will stay in a north Wales town in the UK after a ballot of people in the area. Denbigh residents who took part voted overwhelmingly to retain the bronze of Stanley, who was born in the town. BBC News reports that the consultative vote was called after petitions to remove Stanley's figure over accusations of cruelty and racism during his explorations. The adventurer is most famous for his quote ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’ when he tracked down Dr David Livingstone in a remote part of what is now Tanzania in 1871.

0 notes