#Brissotin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

What is the view on here about who, if anyone, was most responsible for the September massacres ? I’ve seen such differing takes on this, e.g I’m reading Jonathan Isreal who allocates a lot of blame to leading Montagnards , and also Peter McPhee who is much less inclined to do so.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

In defense for Manon Roland

(Before beginning this defense of Manon Roland, and by extension, some Girondins, I want to clarify that I do not share most of their ideas (although I admire some, it must be admitted to avoid any confusion that I completely disapprove of the war project they pursued, which I find irresponsible. Additionally, at that time, other foreign powers were primarily dividing Poland". Moreover, for those who do not know me, you can see the position I defend in the frequency that I share in the links I have provided on my pinned post. I am engaging in the defense here while trying to raise truthful arguments, but some events, such as the arrest of the Girondins, are much more complex than evil Montagnards vs. kind Girondins).

Today, I come to the defense of Manon Roland, the muse of the Girondins, whom some accuse of being nothing more than a scheming bourgeois disconnected from reality. Citizens, I believe it is time to sweep away all these accusations. The republicanism and political activity of Manon Roland can hardly be doubted in light of the facts. Indeed, from a young age, Manon Roland harbored a hatred—quite understandable, if not legitimate, I don't think I need to explain why—for the elites of the Ancien Régime and developed a strong sense of republicanism, not for constitutional monarchy. On this point, there is a resemblance to Camille Desmoulins. She hosted a salon with what was considered in 1790-1791 to be the extreme left, namely Buzot, Pétion, Brissot, and Robespierre (she was not the only one to host a political salon; Madame Condorcet and Madame de Staël did the same). According to her memoirs, she sheltered the Roberts during the terrible shooting on the Champ de Mars due to the repression of the republicans. According to Manon Roland, she eventually sent François and Louise Robert away because they were too imprudent in their behavior, but perhaps we should see signs of the first political divergences there.

Regarding the declaration of war against Austria that Madame Roland supported, there were good reasons for the Girondins—who were not really a heterogeneous group, they did not like the nickname "Girondins" very much—to advance this idea. Let us not forget that Emperor Leopold II of Austria had just died, and his son, Francis I, had succeeded him. He was much more bellicose towards France than his father. Moreover, there were suspicions, confirmed after the flight of the King, who was arrested in Varennes, that Louis XVI wanted foreign powers to invade the country to restore absolute monarchy. If France were to enter into war, Louis XVI would make moves. Not to mention that it is logical to fear that royalist emigrants, especially the future kings Louis XVIII and Charles X, would return with an army. In fact, these emigrants obtained a joint declaration from Prussia and Austria stating that these countries were not at all satisfied with the events in France. According to Manon Roland and others of her political persuasion, logic dictated that France strike first. Louis XVI, who wanted war, would then appoint new "Girondin" ministers, including Jean Marie Roland de la Platière, Manon's husband, who would become Minister of the Interior with the aim of provoking war. This situation thus presents a duplicitous game. She would once again play her role as an organizer behind the scenes, and it is true that she advised her husband a great deal. Moreover, as the war began very poorly for France, the political group of the Girondins made certain decisions, certain decrees rather judicious, especially in the long term, such as the dissolution of the royal guard and the mobilization of 20,000 federates from all over France to form the National Guard, which would later have a decisive effect on the invasion of the Tuileries on August 10. Louis XVI vetoed these decrees, as the Girondins hoped, which showed everyone the double game the King was playing. Furthermore, if some criticize the letter that Jean Marie Roland de la Platière wrote, which led to Manon Roland's husband being dismissed, in which the content of the letter urged the King to reconsider his veto, he was dismissed in June 1792, but now Louis XVI's intentions were even clearer, and later he would become minister again, which shows a long-term victory.

Regarding their liberal economic policies and free trade, and especially the fact that they did not want to abolish private property, it should be noted in their defense that even the most radical revolutionaries were not in favor of ending private property. There is also a misconception that the Girondins were not in favor of abolishing slavery, whereas Brissot, for example, was in favor of gradual abolition. Léger Félicité Sonthonax, a Girondin, nevertheless gradually abolished slavery, gradually putting an end to an inhumane idea, but also to the astute decision that slaves would join the fight for the French Republic.

There have been ideas that the Girondins, and therefore Manon Roland—who is more associated with the Brissotins—were discredited because they voted against the death of the King, but in reality, it was a political strategy not to legitimize the events of August 10, just as the Montagnards later justified the September massacres. Therefore, we cannot blame one political faction for employing a political strategy while condemning another.

Moreover, Manon Roland had reasons to attack Danton, whose suspicions of corruption were proven true, and who could never justify his accounts when he was Minister of Justice, among other things. He was saved only by the support of the Montagnards, who, during a political session, were obliged to show their support for him, but even some of them were beginning to have doubts about him.

Furthermore, when the Girondins—about thirty of them—were arrested, Vergniaud was somewhat right to say that there was a violation of the laws of the Republic, that they were elected by French departments and not just by Paris. Following their house arrest, most of them fled Paris and fomented uprisings. Those who remained were tried, and to illustrate how contested the verdict could be, since the debate had lasted more than 5 days, there was a terrible motion: "If it happens that (the judgment…) the judgment of a case brought before the revolutionary tribunal has (lasted more than three days) been extended three days, the president will open the next session by asking the jurors if their conscience is sufficiently enlightened." This was proposed by Robespierre, but one can hold all the members of the Convention who voted for this motion equally responsible.

Manon Roland showed honor and courage, which must be recognized among other things ( it seems that she really take care of Petion wife who was in jail too… Far from a snobbish person). She stayed in Paris even though she was not bound by an oath to remain under house arrest, did not foment rebellion, yet was judged and later condemned to death, which is completely unjust. She had a certain legalistic aspect (which I find somewhat parallel to Robespierre, who also accepted being arrested by reluctant gendarmes), reinforced by the fact that she apparently refused the help of a friend to escape by pretending to be her, although Manon Roland refused.

Interestingly, she is said to have written a letter to Robespierre again—although they were initially allies then enemies—but she refuses to send it. I will send you this link; does she paradoxically, in this case, still have some respect for him compared to a Danton whom she loathes? According to Lamartine, who is unreliable on many points, so I would doubt this anecdote greatly, Robespierre signed her arrest with a "slight expression of remorse."

In any case, Manon Roland, despite all that can be reproached of her—such as her belief that women should be submissive to their husbands and must accept many rules, her mistakes in not wanting to support social policies—is a dedicated citizen to the Republic, a woman who is not an opportunist, and whose fervor for republicanism cannot be doubted.

Sources: Frédéric Bluche, Danton

See this link: http://lionel.mesnard.free.fr/Paris-revolution-Manon-Roland.html

Jean Clement Martin

Antoine Resche

Memories of Manon Roland

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

born to watch a movie, cursed to memorise revolutionary france's mental state

#why would you go to war with austria?#you dont even have an army#all your commanders are emigres#vce#bad day to be a brissotin#revs#vcehistory#highschool#year12

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frev Friendships — Saint-Just and Robespierre

You who supports the tottering fatherland against the torrent of despotism and intrigue, you whom I only know, like God, through his miracles; I speak to you, monsieur, to ask you to unite with me in order to save my sad fatherland. The city of Gouci has relocated (this rumour goes around here) the free markets from the town of Blérancourt. Why do the cities devour the privileges of the countryside? Will there remain no more of them to the latter than size and taxes? Support, please, with all your talent, an address that I make for the same letter, in which I request the reunion of my heritage with the national areas of the canton, so that one lets to my country a privilege without which it has to die of hunger. I do not know you, but you are a great man. You are not only the deputy of a province, you are one of humanity and of the Republic. Please, make it that my request be not despised. I have the honour to be, monsieur, your most humble, most obedient servant. Saint-Just, constituent of the department of Aisne. To Monsieur de Robespierre in the National Assembly in Paris. Blérancourt, near Noyon, August 19, 1790. Saint-Just’s first letter ever written to Robespierre, dated August 19 1790

Citizens, you are aware that, to dispel the errors with which Roland has covered the entire Republic, the Society has decided that it will have Robespierre's speech printed and distributed. We viewed it as an eternal lesson for the French people, as a sure way of unmasking the Brissotin faction and of opening the eyes of the French to the virtues too long unknown of the minority that sits with the Mountain. I remind you that a subscription office is open at the secretariat. It is enough for me to point it out to you to excite your patriotic zeal, and, by imitating the patriots who each deposited fifty écus to have Robespierre's excellent speech printed, you will have done well for the fatherland. Saint-Just at the Jacobins, January 1 1793

The proposal [to have Robespierre enter the Committee of Public Safety] was made to the committee by Couthon and Saint-Just. To ask was to obtain, for a refusal would have been a sort of accusation, and it was necessary to avoid any split during that winter which was inaugurated in such a sinister manner. The committee agreed to his admission, and Robespierre was proposed. Memoirs Of Bertrand Barère (1896) volume 2, page 96-97.

Patriots with more or less talent […] Jacquier, Saint-Just’s brother-in-law. Robespierre in a private list, written sometime during his time on the Committee of Public Safety

Saint-Just doesn’t have time to write to you. He gives you his compliments. Lebas in a letter to Robespierre October 25 1793

Trust no longer has a price when we share it with corrupt men, then we do our duty out of love for our fatherland alone, and this feeling is purer. I embrace you, my friend. Saint-Just. To Robespierre the older. Saint-Just in a post-scriptum note added to a letter written by Lebas to Robespierre, November 5 1793. Saint-Just uses tutoiement with Robespierre here, while Lebas used vouvoiement.

We have made too many laws and too few examples: you punish but the salient crimes, the hypocritical crimes go unpunished. Punish a slight abuse in each part, it is the way to frighten the wicked, and to make them see that the government has its eye on everything. No sooner do we turn our backs than the aristocracy rises in the tone of the day, and commits evils under the colors of liberty. Engage the committee to give much pomp to the punishment of all faults in government. Before a month has passed you will have illuminated this maze in which counter-revolution and revolution march haphazardly. Call, my friend, the attention of the Jacobin Club to the strong maxims of the public good; let it concern itself with the great means of governing a free state. I invite you to take measures to find out if all the manufactures and factories of France are in activity, and to favor them, because our troops would within a year find themselves without clothes; manufacturers are not patriots, they do not want to work, they must be forced to do so, and not let down any useful establishment. We will do our best here. I embrace you and our mutual friends. Saint-Just To Robespierre the older. Saint-Just in a letter to Robespierre, December 14 1793

Paris, 9 nivôse, year 2 of the Republic. Friends. I feared, in the midst of our successes, and on the eve of a decisive victory, the disastrous consequences of a misunderstanding or of a ridiculous intrigue. Your principles and your virtues reassured me. I have supported them as much as I could. The letter that the Committee of Public Safety sent you at the same time as mine will tell you the rest. I embrace you with all my soul. Robespierre. Robespierre in a letter to Saint-Just and Lebas, December 29 1793

Why should I not say that [the dantonist purge] was a meditated assassination, prepared for a long time, when two days after this session where the crime was taking place, the representative Vadier told me that Saint-Just, through his stubbornness, had almost caused the downfall of the members of the two committees, because he had wanted that the accused to be present when he read the report at the National Convention; and such was his obstinacy that, seeing our formal opposition, he threw his hat into the fire in rage, and left us there. Robespierre was also of this opinion; he believed that by having these deputies arrested beforehand, this approach would sooner or later be reprehensible; but, as fear was an irresistible argument with him, I used this weapon to fight him: You can take the chance of being guillotined, if that is what you want; For my part, I want to avoid this danger by having them arrested immediately, because we must not have any illusions about the course we must take; everything is reduced to these bits: If we do not have them guillotined, we will be that ourselves. À Maximilien Robespierre aux enfers (1794) by Taschereau de Fargues and Paul-Auguste-Jacques. Robespierre and Saint-Just had also worked out the dantonists’ indictment together.

…As far from the insensibility of your Saint-Just as from his base jealousies, [Camille] recoiled in front if the idea of accusing a college comrade, a companion in arms. […] Robespierre, can you really complete the fatal projects which the vile souls that surround you no doubt have inspired you to? […] Had I been Saint-Just’s wife I would tell him this: the sake of Camille is yours, it’s the sake of all the friends of Robespierre! Lucile Desmoulins in an unsent letter to Robespierre, written somewhere between March 31 and April 4 1794. Lucile seems to have believed it was Saint-Just’s ”bad influence” in particular that got Robespierre to abandon Camille.

In the beginning of floréal (somewhere between April 20 and 30) during an evening session (at the Committee of Public Safety), a brusque fight erupted between Saint-Just and Carnot, on the subject of the administration of portable weapons, of which it wasn’t Carnot, but Prieur de la Côte-d’Or, who was in charge. Saint-Just put big interest in the brother-in-law of Sijas, Luxembourg workshop accounting officer, that one thought had been oppressed and threatened with arbitrary arrest, because he had experienced some difficulties for the purpose of his service with the weapon administration. In this quarrel caused unexpectedly by Saint-Just, one saw clearly his goal, which was to attack the members of the committee who occupied themselves with arms, and to lose their cooperateurs. He also tried to include our collegue Prieur in the inculpation, by accusing him of wanting to lose and imprison this agent. But Prieur denied these malicious claims so well, that Saint-Just didn’t dare to insist on it more. Instead, he turned again towards Carnot, whom he attacked with cruelty; several members of the Committee of General Security assisted. Niou was present for this scandalous scene: dismayed, he retired and feared to accept a pouder mission, a mission that could become, he said, a subject of accusation, since the patriots were busy destroying themselves in this way. We undoubtedly complained about this indecent attack, but was it necessary, at a time when there was not a grain of powder manufactured in Paris, to proclaim a division within the Committee of Public Safety, rather than to make known this fatal secret? In the midst of the most vague indictments and the most atrocious expressions uttered by Saint-Just, Carnot was obliged to repel them by treating him and his friends as aspiring to dictatorship and successively attacking all patriots to remain alone and gain supreme power with his supporters. It was then that Saint-Just showed an excessive fury; he cried out that the Republic was lost if the men in charge of defending it were treated like dictators; that yesterday he saw the project to attack him but that he defended himself. ”It’s you,” he added, ”who is allied with the enemies of the patriots. And understand that I only need a few lines to write for an act of accusation and have you guillotined in two days.” ”I invite you, said Carnot with the firmness that only appartient to virtue: I provoke all your severity against me, I do not fear you, you are ridiculous dictators.” The other members of the Committee insisted in vain several times to extinguish this ferment of disorder in the committee, to remind Saint-Just of the fairer ideas of his colleague and of more decency in the committee; they wanted to call people back to public affairs, but everything was useless: Saint-Just went out as if enraged, flying into a rage and threatening his colleagues. Saint-Just probably had nothing more urgent than to go and warn Robespierre the next day of the scene that had just happened, because we saw them return together the next day to the committee, around one o'clock: barely had they entered when Saint-Just, taking Robespierre by the hand, addressed Carnot saying: ”Well, here you have my friends, here are the ones you attacked yesterday!” Robespierre tried to speak of the respective wrongs with a very hypocritical tone: Saint-Just wanted to speak again and excite his colleagues to take his side. The coldness which reigned in this session, disheartened them, and they left the committee very early and in a good mood. Réponse des membres des deux anciens Comités de salut public et de sûreté générale (Barère, Collot, Billaud, Vadier), aux imputations renouvellées contre eux, par Laurent Lecointre et declarées calomnieuses par décret du 13 fructidor dernier; à la Convention Nationale (1795), page 103-105

My friends, the committee has taken all the measures within its control at this time to support your zeal. It has asked me to write to you to explain the reasons for some of its provisions. It believed that the main cause of the last failure was the shortage of skilled generals, it will send you all the patriotic and educated soldiers that can be found. It thought it necessary at this time to re-use Stetenhofen, whom it is sending to you, because he has military merit, and because the objections made against him seem at least to be balanced by proofs of loyalty. He also relies on your wisdom and your energy. Salut et amitié. Paris, 15 floréal, year 2 of the Republic. Robespierre. Robespierre to Saint-Just and Lebas, May 4 1793

Dear collegue, Liberty is exposed to new dangers; the factions arise with a character more alarming than ever. The lines to get butter are more numerous and more turbulent than ever when they have the least pretexts, an insurrection in the prisons which was to break out yesterday and the intrigues which manifested themselves in the time of Hébert are combined with assassination attemps on several occasions against members of the Committee of Public Safety; the remnants of the factions, or rather the factions still alive, are redoubled in audacity and perfidy. There is fear of an aristocratic uprising, fatal to liberty. The greatest peril that threatens it is in Paris. The Committee needs to bring together the lights and energy of all its members. Calculate whether the army of the North, which you have powerfully contributed to putting on the path to victory, can do without your presence for a few days. We will replace you, until you return, with a patriotic representative. The members composing the Committee of Public Safety. Robespierre, Prieur, Carnot, Billaud-Varennes, Barère. Letter to Saint-Just from the CPS, May 25 1794, written by Robespierre. It was penned down just two days after the alleged attempt on Robespierre’s life by Cécile Renault.

Robespierre returned to the Committee a few days later to denounce new conspiracies in the Convention, saying that, within a short time, these conspirators who had lined up and frequently dined together would succeed in destroying public liberty, if their maneuvers were allowed to continue unpunished. The committee refused to take any further measures, citing the necessity of not weakening and attacking the Convention, which was the target of all the enemies of the Republic. Robespierre did not lose sight of his project: he only saw conspiracies and plots: he asked that Saint-Just returned from the Army of the North and that one write to him so that he may come and strengthen the committee. Having arrived, Saint-Just asked Robespierre one day the purpose of his return in the presence of the other members of the Committee; Robespierre told him that he was to make a report on the new factions which threatened to destroy the National Convention; Robespierre was the only speaker during this session. He was met by the deepest silence from the Committee, and he leaves with horrible anger. Soon after, Saint-Just returned to the Army of the North, since called Sambre-et-Mouse. Some time passes; Robespierre calls for Saint-Just to return in vain: finally, he returns, no doubt after his instigations; he returned at the moment when he was most needed by the army and when he was least expected: he returned the day after the battle of Fleurus. From that moment, it was no longer possible to get him to leave, although Gillet, representative of the people to the army, continued to ask for him. Réponse de Barère, Billaud-Varennes, Collot d’Herbois et Vadier aux imputations de Laurent Lecointre (1795)

On 10 messidor (June 28) I was at the Committee of Public Safety. There, I witnessed those who one accuses today (Billaud-Varenne, Barère, Collot-d'Herbois, Vadier, Vouland, Amar and David) treat Robespierre like a dictator. Robespierre flew into an incredible fury. The other members of the Committee looked on with contempt. Saint-Just went out with him. Levasseur at the Convention, August 30 1794. If this scene actually took place, it must have done so one day later, 11 messidor (June 29), considering Saint-Just was still away on a mission on the tenth.

Isn’t it around the same time (a few days before thermidor) that Saint-Just and Lebas would dine at your father’s house with Robespierre? Lebas often dined there, having married one of my sisters. Saint-Just rarely there, but he frequently went to Robespierre’s and climbed the stairs to his office without speaking to anyone. During the dinner which I’m talking about, did you hear Saint-Just propose to Robespierre to reconcile with some members of the Convention and Committees who appeared to be opposed to him? No. I only know that they appeared to be very devided. Do you have any ideas what these divisions were about? I only learned about it through the discussions which took place on this subject at the Jacobins and through the altercation which was said to have taken place at the Committee of Public Safety between Robespierre older and Carnot. Robespierre’s host’s son Jacques-Maurice Duplay in an interrogation held January 1 1795

Saint-Just then fell back on his report, and said that he would join the committee the next day (9 thermidor) and that if it did not approve it, he would not read it. Collot continued to unmask Saint-Just; but as he focused more on depicting the dangers praying on the fatherland than on attacking the perfesy of Saint-Just and his accomplices, he gradually reassured himself of his confusion; he listened with composure, returning to his honeyed and hypocritical tone. Some time later, he told Collot d'Herbois that he could be reproached for having made some remarks against Robespierre in a café, and establishing this assertion as a positive fact, he admitted that he had made it the basis of an indictment against Collot, in the speech he had prepared. Réponse des membres des deux anciens Comités de salut public et de sûrété générale… (1795) page 107.

I attest that Robespierre declared himself a firm supporter of the Convention and never spoke but gently in the Committee so as not to undermine any of its members. […] Billaud-Varenne said to Robespierre, “We are your friends, we have always walked together.” This dishonesty made my heart shudder. The next day, he called him Peisistratos and had written his act of accusation. […] If you reflect carefully on what happened during your last session, you will find the application of everything I said: a man alienated from the Committee due to the bitterest treatments, when this Committee was, in fact, no longer made up of more than the two or three members present, justified himself before you; he did not explain himself clearly enough, to tell the truth, but his alienation and the bitterness in his soul can excuse him somewhat: he does not know why he is being persecuted, he knows nothing except his misfortune. He has been called a tyrant of opinion: here I must explain myself and shine light on a sophism that tends to proscribe merit. And what exclusive right do you have to opinion, you who find that it is a crime to touch souls? Do you find it wrong that a man should be tenderhearted? Are you thus from the court of Philip, you who make war on eloquence? A tyrant of opinion? Who is stopping you from competing for the esteem of the fatherland, you who find it so wrong that someone should captivate it? There is no despot in the world, save Richelieu, who would be insulted by the fame of a writer. Is it a more disinterested triumph? Cato is said to have chased from Rome the bad citizen who had called eloquence at the tribune of harangues, the tyrant of opinion. No one has the right to claim that; it gives itself to reason and its empire is not the in the power of governments. […] The member who spoke for a long time yesterday at this tribune did not seem to have distinguished clearly enough who he was accusing. He had no complaints and has not complained either about the Committees; because the Committees still seem to me to be dignified of your estime, and the misfortunes that I have spoken to you of were born of isolation and the extreme authority of several members left alone. Saint-Just defending Robespierre in his last, undelivered speech, July 27 1794

One brings St. Just, Dumas and Payan, all of them shackled, they are escorted by policemen. They stay a good quarter of an hour standing in front of the door of the Committee’s room; one makes them sit down onto a windowsill; they have still not uttered a single word, pleasant people make the persons who surround these three men step aside, and say move back, let these gentlemen see their King sleep on a table, just like a man. Saint-Just moves his head in order to see Robespierre. Saint-Just’s figure appeared dejected and humiliated, his swollen eyes expressed chagrin. Faits recueillis aux derniers instants de Robespierre et de sa saction, du 9 au 10 thermidor (1794) by anonymous.

The Committee of General Security was being spied on by Héron, D…, Lebas: Robespierre knew, through them, word for word, everything that was happening at said committee. This espionage gave rise to more intimate connections between Couthon, Saint-Just and Robespierre. The fierce and ambitious character of the latter gave him the idea of establishing the general police bureau, which, barely conceived, was immediately decreed. Révélations puisées dans les cartons des comités de Salut public et de Sûreté générale ou mémoires (inédits) (1824) by Gabriel Jérôme Sénart.

Intimately linked with Robespierre, [Saint-Just] had become necessary to him, and he had made himself feared perhaps even more than he had desired to be loved. One never saw them divided in opinion, and if the personal ideas of one had to bow to those of the other, it is certain that Saint-Just never gave in. Robespierre had a bit of that vanity which comes from selfishness; Saint-Just was full of the pride that springs from well-established beliefs; without physical courage, and weak in body, to the point of fearing the whistling of bullets, he had the courage of reflection which makes one wait for certain death, so as not to sacrifice an idea. Memoirs of René Levasseur (1829) volume 2, page 324-325.

Often [Robespierre] said to me that Camille was perhaps the one among all the key revolutionaries whom he liked best, after our younger brother and Saint-Just. Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834) page 139.

After the month of March, 1794, Robespierre's conduct appeared to me to change. Saint-Just was to a great degree the cause of this, and this leader was too youthful ; he urged him into the vain and dangerous path of dictatorship which he haughtily proclaimed. From that time all confidences in the two committees were at an end, and the misfortunes that followed the division in the government became inevitable. […] We did not hide from [Robespierre] that Saint-Just, who was formed of more dictatorial stuff, would have ended by overturning him and occupying his place ; we knew too that he would have us guillotined because of our opposition to his plans; so we overthrew him. Memoirs of Bertrand Barère (1896), volume 1, page 103-104.

The continued victories of our fourteen armies were as a cloud of glory over our frontiers, hiding from allied Europe our internecine struggles, and that unhappy side of our national character which acts and reacts so deplorably as much on the whole population as on our nghts and our manners. The enthusiasm with which I announced these victories from the tnbune was so easily seen that Saint- Just and Robespierre, being in the committee at three in the morning, and learning of the taking of Namur and some other Belgian towns, insisted for the future that the letters alone of the generals should be read, without any comments which might exaggerate their contents. I saw at once at whom this reproach was directed, and I took up the gauntlet with the deasion of a man willing to once more merit the hatred of the enemies of our national glory, and the bravery of our armies. Then Samt-Just cried, “ I beg to move that Barère be no longer allowed to add froth to our victories.” […] While Saint-Just was reproving me, Robespierre supported the longsightedness of his friend… […] The next day my report on the taking of Namur was somewhat more carefully drawn up, and I alluded to the observation of my critics, who were envious of the power of public opinion in favour of our troops, then busied in saving the country. This phrase in my report was much commented on, although its meaning was only clear to those who had heard the debate in the committee on the previous evening “Sad are the tunes, sad is the period, when the recital of the triumphs and glories of the armies of the Repubhc is coldly hastened to in this place! Henceforth liberty will be no longer defended by the country, it will be handed over to its enemies!”This pronouncement was not of a nature to be forgiven by Saint-Just and Robespierre, so they determined to supplant me with regard to these reports. They forced that idiot Couthon to attend the Committee of Public Safety at eleven in the morning, before I got there Couthon asked for the letters of the generals that had come in during the night, and took his usual seat at the back of the hall, waiting until the assembly was sufficiently full for him to announce the victones. About one, Couthon, being paralysed and unable to stand up in the tribune, coldly read the news from the armies from his place. This time, no effect was produced in the Assembly, or upon the public. This attempt, authorised by Robespierre and Saint-Just, having missed fire completely, the committee signified its dissatisfaction at the innovation. Ibid, volume 2, page 123-125

After his return from Fleurus, Saint-Just remained some time in Paris, although his mission as representative to the armies of the Sambre and Meuse and the Rhine and Moselle was unfinished. The campaign was only beginning, but he had several projects in hand, and he stayed in committee, or rather his office, where he was always absorbed and thoughtful. Robespierre, in speaking of him at the committee, said familiarly, as if speaking of an intimate friend: ”Saint-Just is silent and observant, but I have noticed, in his personality, he has a great likeness to Charles IX.” This did not flatter Saint-Just, who was a deeper and cleverer revolutionist than Robespierre. One day, when the former was angry about several legislative propositions or decrees that did not please him, Saint-Just said to him, “Be calm, it is the phlegmatic who govern.” Ibid, volume 2, page 139

This tyrannical law was the work of Saint-Just Consult the Momteuv of the 22nd of Germinal, where it is reported with the explanation of his motives, and you will see that, if there had been no committee, SamtJust would have used his power with as much dictatorial fanaticism as did Manus, that great enemy of the Roman anstocracy. Robespierre’s fnend never forgave me for having dimmished the force of this blow. Whilst I was at the tnbune of the Convention, he came, with someone unknown, and perused my register of requisitions. He took down certain names, and some days after, towards midnight, Robespierre and Saint-Just entered the committee, where they did not usually come (for they worked in a private office, under pretext that their duties were completely private) A few moments after their entry Saint-Just complained of the abuse I had made of the requisitions, which had been granted, said he, in such profusion that the law of the 21st of Germinal had become null and void. Ibid, volume 2, page 146

Robespierre, Saint-Just and Couthon were inseparable. The first two had a dark and duplicitous character; they pushed away with a kind of disdainful pride any familiarity or affectionate relationship with their colleagues. The third, a legless man with a pale appearance, affected good-nature, but was no less perfidious than the other two. All three of them had a cold heart, without pity, they interacted only with each other, holding mysterious meetings outside, having a large number of protégés and agents, impenetrable in their designs. Révélations sur le Comité de salut public by Prieur-Duvernois

Robespierre, who had great confidence in Le Bas because he knew his wise and prudent character well, had chosen him to accompany Saint-Just, whose burning love of the fatherland sometimes led to too much severity, and who had a tendency to get carried away. […] [Saint-Just] also had friendship for me and came often enough to our house. […] Finally our providence, our good friend Robespierre, spoke to Saint-Just to engage him to let me depart with them, along with my sister-in-law Henriette. He consented, but with some conditions. Memoirs of Élisabeth Lebas (1901)

Volume 8 — page 153. ”Saint-Just, his (Robespierre’s) only confident.” His only confident? Élisabeth Lebas corrects a passage in Alphonse de Lamartine’s Histoire des Girondins (1847)

The Lamenths and Péthion in the early days, quite rarely Legendre, Merlin de Thionville and Fouché, often Taschereau, Desmoulins and Teault, always Lebas, Saint-Just, David, Couthon and Buonarotti. Élisabeth Lebas regarding visitors to the Duplay’s during the revolution

—

When arriving in Paris in September 1792, Saint-Just first lived on No. 7 rue de Gaillon up until March 1794, and then on No. 3 rue de Caumartin (today’s No. 5) up until his death. Both those places were within a ten minute walking distance from Robespierre’s home on 398 Rue Saint-Honoré.

Saint-Just was away from Paris (and therefore Robespierre) on missions between March 9 to March 31, October 17 to December 4, December 10 to December 30 (1793), January 22 to February 13, April 30 to May 31 and June 10 to June 29 (1794).

#sj and max holding hands 🤗💓#robespierre#saint-just#maximilien robespierre#louis antoine de saint just#barère#élisabeth lebas#philippe lebas#frev#frev friendships#long post#saintspierre

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint-Just Hyping up Robespierre's Speech

Saint-Just, ordinarily rather reserved at the Jacobin Club, made an exception on January 1, 1793. Despite presiding over the session, he didn't share personal views or push his own agenda. Instead, he invited his colleagues to fund the printing and nationwide distribution of Robespierre's second speech on Louis XVI's trial (delivered on December 28, 1792)

His address was probably delivered in a a rather matter-of-fact and perfunctory tone. That being said, in my head, he's going full movie villain on the jacobins, urging them to open their purses or face the "dire consequences from the Archangel of Terror! Mwahahaha!”

(Translation under the cut)

Translation:

Citizens, you are well aware that, to dispel the errors with which Roland has enveloped the entire Republic, the Society has resolved to print and distribute Robespierre's speech. We have regarded it as an eternal lesson for the French people (1), as a sure way to unmask the Brissotin faction and to open the eyes of the French to the virtues of the minority seated on the Mountain that have been too long unknown. I remind you that a subscription office is open at the secretariat. It is enough for me to indicate this to stimulate your patriotic zeal, and, by emulating the patriots who have each contributed fifty ecus (2) to print Robespierre's excellent speech, you will have well earned the gratitude of the nation.

Notes

(1) The gushing is adorable

(2) In today's terms, fifty ecus translates to approximately 1900 euros. This was no small amount, particularly in light of the country's economic climate at the time.

Source:

Saint-Just, Louis Antoine Léon de. Œuvres. Paris: Gallimard, 2014

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ladies and gentlemen, it’s official! I’m writing a musical!

For those of you in the community who have known me for a while, this is nothing new, but I’ve been working on it for quite awhile, so I finally want to unveil what I have so far.

The show is officially called “Tyrant! The Story of Robespierre” or just “Tyrant!” for short, and here’s my first concept for the album cover below!

As for the actual story and songs, right now I’m planning on having 16 songs per act, and I’ll format the songs I’ve written or am currently in the process of writing!

Italic = work in progress

Bold = fully written

With that being said, this is the song catalogue and all I’ve gotten done so far!

Act 1:

Tyrant! (Show opener) - immediately after his death

Address for the King - early childhood

Never shall we part - transition from childhood to adulthood, meets Camille

Song addressed to Miss Henriette - young adulthood

And So I Reminisce - trio song for the siblings

He Just Can’t Stop - lawyer career in Arras

Let Us Speak/We Swear - Estates general + tennis court oath

Camille’s Address (Bring It Down) - Storming of the bastille

Hey Ladies! (Theroigne’s song + Women’s March on Versailles)

Bienvenue aux Jacobins - Joins the Jacobin club and meets Danton, gets elected president of the club

Never shall we part (1st reprise) - Camille’s marriage to Lucile

Escape (Louis + Marie flee Paris, Champ de Mars massacre)

There’s Safety Here (Robespierre meets Maurice Duplay, moves into the Duplay house)

This Means War! (Speeches against the war and Brissotins, war gets declared anyways)

The Tuileries Tango (Storming of the Tuileries and overthrow of the monarchy)

Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité For All (Establishment of the republic, Robespierre at his height, his big “I want” song)

Act 2:

Incorruptible (Saint-Just’s debut and Robespierre’s election to the National convention)

So Ends the Reign of Tyranny (Louis’ trial and execution)

Bienvenue aux committee/ Bienvenue le Jacobins (reprise) (Appointment to the CPS)

Choose Your Side/And So I Reminisce (reprise) (Charlotte and Augustine’s fight, fracture in the family, duet with Élèonore, PLATONIC, NOT ROMANTIC)

Principio Ad Finem/ A late night’s walk (“darker” ‘I want’ song, NOT A VILLAIN SONG )

What is he doing? (Camille publishes his paper and says stupid stuff)

Never Shall We Part (2nd and 3rd reprises) (Max and SJ duet, Camille’s denouncement from friends to enemies)

A Meeting/Make Him a Monster (CPS meeting, Thermidorian villain song)

You’re Unwell (Eleonore and SJ duet, Max falls ill/ slowly loosing his sanity)

So Ends the Reign of Tyranny/ Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité for All (reprise) (Arrests and executions of Camille, Danton and their followers, closest thing to a villain song for Robespierre)

This Glorious Day (Festival of the Supreme Being, more Thermidorian conspiring)

Principio Ad Finem (reprise) (Max writes his 8 Thermidor speech)

My Final Bow (8 Thermidor speeches for the convention and the Jacobins)

We Swear/Let Me Speak! (9 Thermidor denouncement and arrest)

Requiem (Hotel De Ville siege, bullet to the jaw, death, 11th hour power ballad)

May You Ne’er Be Forgotten (basically charlotte’s ‘who lives who dies who tells your story’, her 11th hour power ballad, grand finale of the show)

I know that was a lot thrown at y’all, and obviously I’ve still got a long ways to go, but I’ll be working hard at it all summer, and I hope to have at least half of the first act finished by the end of this summer! I’ll keep working on asks too now that my schedule’s freed up, but I thought it’d be a fun announcement to share with all of you for Max’s birthday, and I can’t wait for you to see the rest of it! Love you all! ❤️❤️❤️

-Syd

319 notes

·

View notes

Note

Don't you ever mention Hébert or Robespierre again in all the 15-odd years left in your pitiful Maraisard life or I'll shoot myself. Im so pissed off about this I could honestly go outside right now and set up a fusillade just for spite"s sake and it would entirely be the fault of YOU and your venomous calumny,paid for by WILLIAM PITT no doubt,and what's worse is that there's no consequences for this nowaday. See,in my France,when the merciful and good Saint-Just still had the say-so,even half a canto of one of your dumb fucking posts would be enough to get one tribunaled. But nowadays one can just go online and say all sorts of counter-revolutionary,Girondist,Rolandine,Brissotin,Indulgent,Thermidorian,Feuillantesque,DUMB . FUCKING NONSENSE. And not face even a single consequence...and I thinks that's not so good. Possibly even bad if I'm being completely honest,which I am. If you ever feel the compulsion to post about one of the noble and virtuous men of the Montagne of 1794 again (or Hébert for that matter) please be aware that I will be rendering my remains unrecognizable by way of a sawn-off shotgun.

Calm down, kid.

#death threats#threats#tw sui ideation#Suicide threats#I made him mad by... mentioning historical fact?#I don't understand#Copypasta

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pour la défense du terme "réaction (thermidorienne)"

Voici une section d'un article que je suis en train de faire à partir de la 4e partie (encore inédite) de ma thèse, que je viens de rédiger et qui va sans doute finir par être réduite de beaucoup, mais que je pense pouvoir intéresser mes abonnés ici. Il s'agit d'une réflexion sur la pertinence du terme "réaction (thermidorienne)".

Grosso modo, je suis plutôt d'accord avec l'idée qu'utiliser "Réaction thermidorienne" pour désigner la période 9 thermidor an II-4 Brumaire an IV n'est pas génial, parce que cela ignore les mois de flottements et de luttes politiques de la fin de l'an II et du début de l'an III (je préfère parler de la période de la "Convention thermidorienne"), mais je pense qu'il est insensé de prétendre que le projet politique qui a fini par triompher au cours de cette période n'était pas réactionnaire :

À l’instar des critiques de l’usage de « la Terreur », que ce soit comme désignant d’une « politique[1] » cohérente ou simple chrononyme, d’autres termes traditionnels connaissent en ce moment historiographique une remise en question salutaire. Celui de « Réaction thermidorienne » en fait partie. Comme le dit Michel Biard en parlant des désignants des acteurs, « « thermidorien » n’a aucun sens précis, « réacteur » est abusif puisqu’on ne peut réduire la période qui suit Thermidor à une « réaction » au sens politiquement piégé du mot[2] ». On ne peut qu’être d’accord avec Biard sur premier terme. Le problème du mot « thermidorien » — qui peut s’appliquer tant aux personnes ayant participé au coup d’État parlementaire du 9 thermidor ou qui y ont adhéré après, qu’à celles qui en profiteront par la suite pour dénoncer et renverser les politiques adoptées au cours de 1793 et de l’an II — est connu depuis longtemps. Néanmoins, l’usage continué du terme de « réacteur », qui a précisément été adopté pour différencier les individus de la seconde catégorie de ceux du premier, et avec lui de « réaction », me paraît justifié à trois titres. D’abord, comme il s’agit d’un terme d’époque, il peut être utile pour comprendre l’état d’esprit de ceux qui l’employèrent. Mais au-delà de ce premier type d’usage, et sans vouloir englober toute la dernière séquence de la Convention à partir du 9 thermidor dans le terme de « Réaction », ce qui serait effectivement abusif, il y a fondamentalement un processus de « réaction » au premier sens du mot à l’œuvre puisque il y eut chez beaucoup de conventionnels une volonté affichée (quoique sélective) de revenir sur l’œuvre des mois précédents. Ensuite, le terme de « réaction » au sens fort du terme, non comme chrononyme, mais pour désigner la politique d’abandon des mesures et jusqu’aux principes démocratiques, sociaux et jusnaturalistes de 1793-an II, et de « réacteur » pour désigner ceux qui soutenaient un tel projet politique, me paraît adapté. On peut reconnaître la complexité de la « réaction » contre une « terreur » construite de façon à imbriquer aussi étroitement violence et participation populaire, de façon cynique chez les anciens Montagnards et sans doute beaucoup plus sincère, tant le lien leur paraissait naturel (leurs propres expériences semblant confirmer les écrits des auteurs anciens hostiles à la démocratie) chez les « Brissotins » réintégrés. On peut même se demander comment situer par rapport à ce terme les démocrates qui ont participé à la construction de l’épouvantail « terroriste » en croyant ne s’opposer qu’au volet répressif des politiques de 1793-an II mais qui finirent par dénoncer la « réaction ». Néanmoins, on ne peut comprendre une période qui vit l’abandon de la constitution de 1793 en faveur de celle qui fonda le Directoire, qui réprima la gauche et anéantit le mouvement populaire, sans pouvoir nommer le projet politique antidémocratique, antisocial et donc réactionnaire qui fut la cause de ces retournements, et ceux qui en étaient porteurs. [1] Patrice GUENIFFEY, La politique de la Terreur, 2000. [2] Michel BIARD, Les derniers jours de la Montagne, 2023, p. 23.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

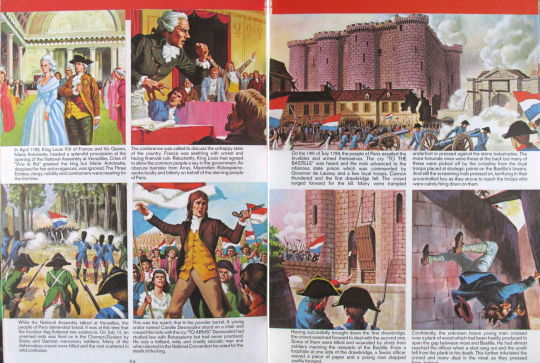

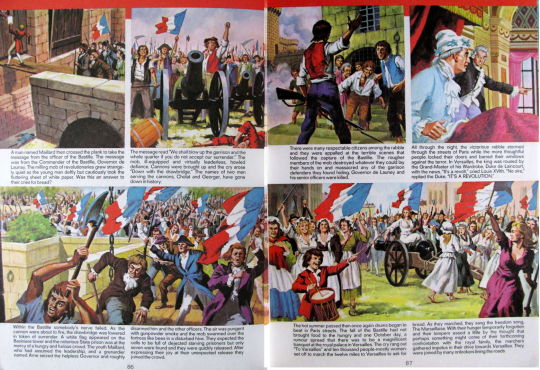

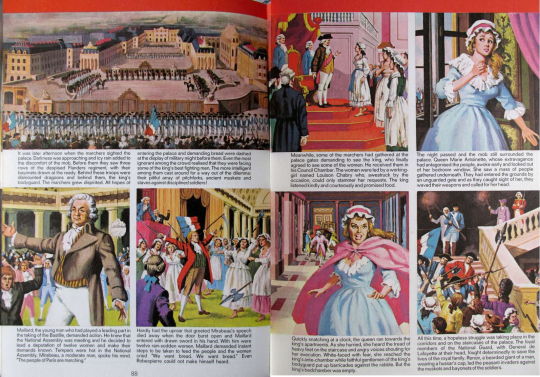

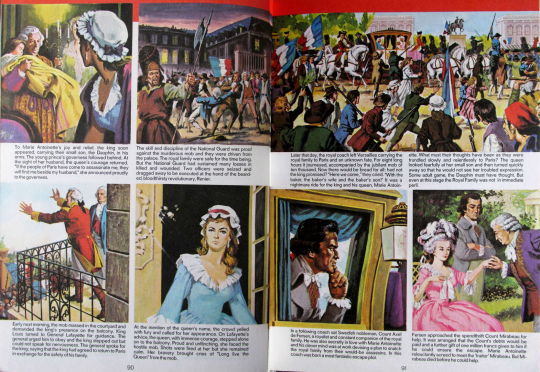

Tell Me Why children's annual 1970

@suburbanbeatnik @trashpoppaea @montagnarde1793 @patientsisavertu @taleon-arts @vivelareine

If you thought Jackie 1976 was bad… This is from Tell Me Why, a non-fiction annual from 1970. Good to see a piece on Vidocq, but Marie-Antoinette has the Julie Christie/Jean Shrimpton/Catherine Deneuve look of the Jackie heroine, and I'm not sure how old the artist thought Max was…! They've made him look older than Marat! In the children's books of this era, the Brissotins were generally presented as the only Revolutionaries you were allowed to like.

#french revolution#révolution française#popular historical iconography#popular historiography#vintage children's books

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paradoxes in the Revolutions of 1792 and the Revolt of 1870

Warning: There are some text elements in the treatment of Algerian deportees in New Caledonia that are shocking. So refrain from reading if you are not ready.

Do you share my impression of certain aspects of the different revolutions or uprisings in France? I mean, the French Revolution, at its most left-leaning during the government of Year II, was very conservative regarding property rights. Regarding property rights, the entire political class was very timid, even the far left like the Enragés and the Hébertists, who were more focused on economic issues like taxation. However, some, like Momoro, apparently began to consider land redistribution, such as sharing large farms, but without a clear plan (and far from any notion of collectivization of agriculture). There was a concession made by the Convention on property rights with the Ventôse Laws, perhaps? And it is true that on certain economic issues, there were conservative elements, even though during the journée of September 5, 1793, the sans-culottes managed to extract the maximum.

Even Gracchus Babeuf, who seems to advocate for collective exploitation, primarily talks about agriculture. I'm not saying there weren't progressive aspects. There were, like the introduction of universal suffrage, for example, and many other aspects, such as the fact that deputies like Louis Michel le Peletier defended the project to implement free, mixed, secular, and compulsory education, supported by several deputies, including Robespierre (it's sad that this was only adopted years later by a man who, opportunistically, in my opinion, lacked the integrity of Le Peletier, who seems to have been opposed to most of the revolutionaries of 1793-1794 and who unjustly reaped all the credit for this project—I’m talking about Jules Ferry, sorry to the fans of this character). But it must be acknowledged that there were also conservative aspects.

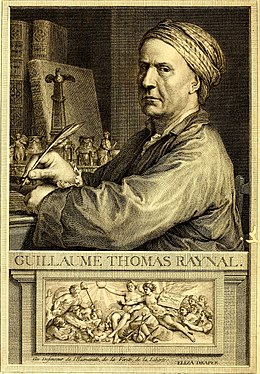

Paradoxically, the Convention proved to be extremely progressive compared to so many others regarding the colonies. The abbé Raynal, so conservative on property rights, apparently called Toussaint Louverture the "Black Spartacus." Sonthonax, considered a Brissotin and advocate of gradual abolition of slavery, did not hesitate to oppose the colonists and slaveholders (just like the Convention) by granting full citizenship to the revolting slaves of 1791 barely a year later. There was the dissolution of the colonial assembly, and important and well-known revolutionaries enthusiastically supported the revolts of the colonized, even their independence, like Deputy Marat or the prosecutor of the Commune, Chaumette, among many others. Black deputies were elected, such as Jean-Baptiste Belley. Some Black people managed to attain high ranks. The overly hostile colonists could be expelled, and there was the dismissal of Governor Philippe Blanchelande, who had distinguished himself by his fierce repression of the slave revolt. During his execution in 1793, Rosalie Julien, one of the important women of the revolution, wrote, "He made the blood of Blacks and patriots flow in streams." It is important to note that she equated the attack on Blacks with that on people considered patriots, a more common position at that time than one might think. I know we must be careful about anachronisms, but I feel that aside from a distrust of foreigners (though this did not prevent people like Fleuriot Lescot or Claude François Lazowski, who came from a Polish family, from holding important positions), the French political class was less racist in 1794 than in 1870 or during the mid-20th century, especially concerning the colonies and overseas territories. There was a regrettable step backward (honestly, can you imagine the Convention of Year II, or the Jacobin or Cordelier Clubs tolerating even the idea of a horrible human zoo as we saw in 1906? I can't). Of course, there were people who supported slavery at that time, like Cloots (a very questionable and paradoxical figure of the revolution, considered close to the Hébertists, yet a very wealthy and conservative man regarding property rights, who had pro-slavery thoughts and was a fervent supporter of colonization because his family and he profited from it, even though he supposedly wanted the Revolution to extend beyond borders according to his own words; according to historian Antoine Resche, he called himself the orator of the human race—very complicated as a revolutionary).

For those who think of the left envisioned by Karl Marx, we're still far from it. Here's an excerpt from The Holy Family: "The revolutionary movement that began in 1789 with the social circle, which, in the midst of its course, had as its main representatives Leclerc and Roux and eventually succumbed temporarily with Babeuf's conspiracy, had sown the seeds of the communist idea, which Babeuf's friend, Buonarroti, reintroduced in France after the revolution of 1830. This idea, developed consistently, is the idea of the new state of the world." Moreover, I have encountered communists who heavily criticize the revolutionaries, except for some ultra-revolutionary members (a few have even added Marat to the list of characters they appreciate, though they know he was not an ultra-revolutionary) by explaining that, in their view, the second revolution from 1792 until the fall of the last Montagnards like Charles Gilbert Romme remained bourgeois, though less so than the one of 1789.

Abbé Raynal

Jean Baptiste Belley

Léger-Félicité Sonthonax

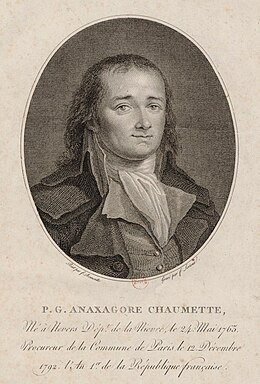

Pierre-Gaspard Chaumette

Jacques Roux

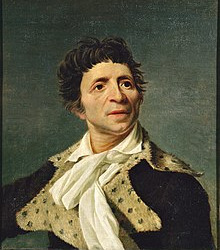

Jean Paul Marat

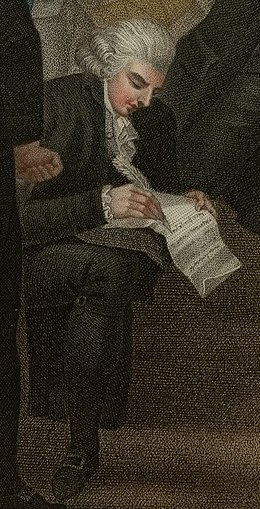

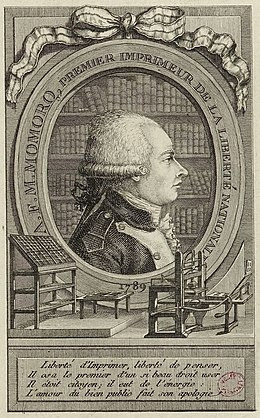

Antoine-François Momoro

Anacharsis Cloots

Toussaint Louverture

Gracchus Babeuf

Jean-Baptiste Edmond Fleuriot-Lescot

Rosalie Jullien

On the other hand, we have the Paris Commune uprising of 1870, which ended in horrific repression (some estimate that 10,000 people died within a week in the city of Paris).

The origins of this Paris Commune are quite complex to explain, involving the fall of Napoleon III's dictatorship, Bazaine's lamentable behavior, the fact that the new regime forming a republic was composed of monarchists while Paris was predominantly republican, the new regime's abolition of wages, which was one of the only sources of income for workers, and so on.

These Paris communards represented various leftist movements, including the Blanquists, named after Auguste Blanqui (a small anecdote: the composer of "The Internationale" was a communard named Eugène Pottier), anarchists, Proudhonians, as well as centralists like Delescluze (some might even call them Jacobins, though I am not well-informed about that), and even collectivists. The Paris Commune marked a significant shift to the left (albeit briefly). I will mention four measures passed by this government: the abolition of night work (at least for bakers), the separation of Church and State, free, secular, and compulsory education, and the elimination of distinctions between legitimate and illegitimate children.

The repression was atrocious, with death sentences raining down (one of the key figures in the repression, alongside Thiers, was Jules Ferry), and deportations to New Caledonia as well.

It is here that the communards (or at least a significant number of them) were less progressive on certain issues than the main actors of the Convention of Year II. Except for individuals like Louise Michel or Charles Malato, the son of deported communards who followed them to Nouméa, most of the communards did not support the Kanaks at all. There was a lingering racist attitude towards these colonized people, who were also fighting against the injustices imposed on them by the French government. Some even participated in the repression against the Kanaks following the Great Kanak Revolt of 1878, whose main leaders were Atai, chief of Komalé, and Cavio, chief of Nékpi, among others.

I have the impression that the communards behaved similarly toward the deported Algerians. Indeed, in 1869, a significant new insurrection broke out in Algeria, spreading from Kabylie, the Aurès, and towards Algiers, and other territories (the war against France began in 1830, with the defeat of Emir Abdelkader in 1847, the division of three departments in 1848, and the continued Algerian resistance against the establishment of the French colony, notably led by Lalla Fatma N’Soumer and Cherif Boubaghla, though Fatma N'Soumer was captured by the French army in 1857 and died in captivity in 1863 at the age of 33, and Cherif Boubaghla died in combat in 1854; other uprisings lasted until 1870, and one of the most significant was that named Mokrani revolt ).

The insurrection was defeated after fierce fighting, with death sentences raining down, the expulsion of tribes, the sequestration of property, and deportations as well, with around 60 deportees dying from the conditions of deportation. Louise Michel described their arrival in these terms: "We saw them arrive in their great white burnouses, the Arabs deported for having also risen up against oppression. These Orientals, imprisoned far from their tents and flocks, were simple and just, and could not understand the way they had been treated."

They had even fewer privileges than the deported communards. According to some sources, they were chained with red-hot irons, subjected to more intense forced labor, and had to eat soup from the shoes of the jailers. They were forcibly separated from their wives, leading some to marry Kanaks, while others married communard women. It is true that some communards, like Louise Michel and Jean Allemane, campaigned for their amnesty. There were escapes by Algerians, some of whom were recaptured. One of the most famous was Azziz El Haddad, who died in the home of his friend the communard and former deportee Eugène Mourot on August 22, 1895, in Paris. Mourot was also opposed to the colonization of Algeria. A collection by the communards against colonization ensured that his body was repatriated to Algeria.

However, while some deported communards supported them, it should not be forgotten that other communards were driven by colonialist mindsets. It is also interesting to learn more about the Commune of Algiers, proclaimed by Alexandre Lambert, among others. Some European insurgents supported a fraternal republic, but one that excluded Algerian insurgents. Alexandre Lambert, who was killed during the Bloody Week, published a newspaper called Le Colon. The title is quite telling.

Auguste Blanqui

Charles Malato

Jean Allemane

Louise Michel

Eugène Mourot

Bou-Mezrag El-Mokrani, brother of Mohamed El-Mokrani

Cheikh El Haddad father of Aziz el Haddad and Cheikh M'hand

Chérif Boubaghla and Lalla Fatma N'Soumer (Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, 1866) alleged portraits

Émir Abdelkader

Ataï

And so, this is the paradox of these two French "revolutionary groups" from 1792-1794, and the group of the Communards from 1870. The first group, still very timid on certain social rights such as property rights (even within the extreme left), was nevertheless much more committed to advocating for more rights among men of different colors, with some even going further by supporting the ideas of revolts by the colonized. Moreover, the colonizers were much less listened to after a certain point in time.

In contrast, during the Paris Commune, while there were more progressive ideas and people who were less conservative about property rights (after all, there was representation from collectivists), they were much less engaged in supporting the colonized and at times even approved of colonial repressions.

Sources: Jean Marc Schiappa Alain Decaux Antoine Resche Mehdi Lallaoui - Kabyles du Pacifique

P.S.: I'm not trying to hand out praise or criticism regarding property rights. I'm merely attempting to make an observation. In fact, I might even be wrong on certain points, so I invite you to correct me. And I don't intend to bash the Paris Communards, many of whom suffered or gave their lives for an ideal Republic, and whose horrific repression we don't often discuss. But it's important to acknowledge everything, including their mistakes. Perhaps one day I should address the question of the French left as a whole, from 1789 to 1962, concerning colonization.

#frev#french revolution#france#commune#Paris Commune#1700s#1800s#algeria#new caledonia#colonization#Kanaks#marat#louise michel#Blanqui#babeuf#sonthonax#toussaint louverture#third republic

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

I must admit I am fascinated by your admiration for l'Incorrupt,considering that from a cursory glance your principles seem decidedly Brissotin in all but the letter. You don't mind le Journée de 31 mai? The fall of the Gironde in general? Desmoulins getting wrecked and owned for party rocking free speech style? I'm not trying to struggle session you,it's just simply never that I see an individual of your apparent political persuasion (social democrat?) arguing in DEFENSE of Robespierre!

Robespierre certainly wasn't perfect. He wasn't a great person and there are choices of his I absolutely disagree with, (such as the Law of 22 Prairial), but he did good things too. He wasn't a dictator, like most people believe. That's the main I'm defending here. My defense comes from an essay I wrote for my teacher in response the EXTREMELY inaccurate slideshows presented to the class during a unit on the French Revolution. Simply put, he was not a bloodthirsty tyrant that guillotined half of France. To say otherwise is factually incorrect. This viewpoint comes from Thermidorian propaganda, not the actual events as they happened. Autistic hyperfixation took over and I did quite a bit of research on the topic, checking the legitimacy of my sources (since I knew it would be a bold stance to take), I pirated a few books since there didn't seem to be a way for me to access a physical copy from any library or bookstore in the city (unfortunately), then I spent 11 days writing a 30 page essay and handed it in to my teacher. I got the highest possible grade for that essay.

There are things about Robespierre I find quite interesting, such as his various progressive political views, or the high probability that he was autistic. And there's so much misinformation and propaganda around his image I don't mind correcting based on the deep research that I have done. I defend him because saying that he was a dictator is a claim based on poor, surface level research. However I also allow myself to denounce these claims whilst acknowledging the things that he did do wrong (in my opinion). If you request, I can explain in deeper detail why, but for now I will mention briefly that: He was never the leader of France; he was one of 12 members of the Committee of Public Safety that had equal power; Robespierre signed the least number of arrest warrants out of all the Committee members; he openly hated the death penalty and tried to have it abolished in 1790; there is no evidence to suggest he even attended a single execution; the Festival of the Supreme Being was not Robespierre's attempt to start a cult around himself, though his enemies certainly took it as an opportunity to frame his as such; he definitely had autism, there's no disputing that one, it is so blatantly obvious.

Thank you for the ask! If you have any more questions, I'm happy to try and answer.

#i wrote a 30 page essay#this only the tip of the iceberg#i could talk about it for ages#but right now i'm tired and appreciate the ask#mainly that it wasn't overly aggressive as i have sometimes encountered in the past#thus giving me the chance to calmly explain my point of view

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why do people on here prefer the mountain to the Brissotin ? I feel like I’ve not been able to work out what the difference in opinion actually was

I suppose people have their own reasons. The Mountain are more left leaning while Brissotins are more center. It depends on people's own political opinions, and also why they are interested in the French Revolution in the first place. The Monagnards are simply more (in)famous figures of the Revolution. I suppose there might be people who get interested in frev for Brissot (?) but not sure if they are around here. So, I'd say Montagnards being preferred is a combination of popularity + people interested in frev being more left-leaning. (Like, seriously, general population TM sees frev as aristocrats vs sans culottes, or maybe Marie Antoinette vs Robespierre. They don't really know about Brissotins, tbh.) That being said, I feel the Brissotin brand of approach is more popular in general life, at least in the (Anglo) West (UK, USA, Canada, etc.) even if people don't know about it being a Brissotin approach. Not sure how France feels about it. But you know the whole idea about the French Revolution "simply replacing aristocracy with bourgeoise (rich middle class)"? It's the Brissotin spirit (I wouldn't say that they won in the end, because it was Thermidorian mess and not them, but you sure can't blame Montagnards for that. Unless you want to blame them for not getting their shit together to prevent it, but that's another story). So I suppose some people preferring Montagnards is also out of the protest for the present state of being, which is more in line with Brissotin approach than anything else, imo. Yes, I am aware this is an oversimplification, but you get the idea.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

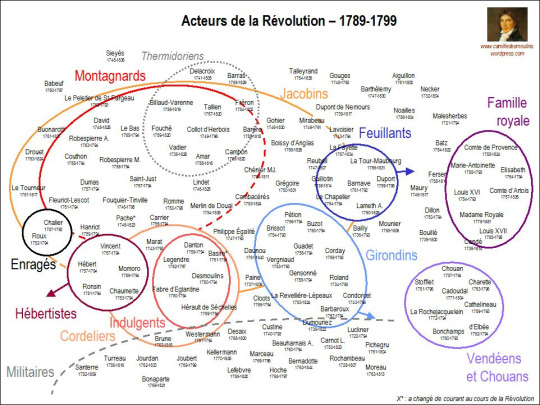

How many political parties were there during the revolution?

Because duo to the popularity (I mean by popularity "the most influential" like "Jacobin" and "Girondins" etc. ) I start to forgot that was there more political parties so could you tell us about them and their most notable achievements ?

It is hard to really talk about political parties when it comes to the French Revolution, at least not in the way in which we today think of the term, with worked out ideologies and party programs for each and everyone. Furthermore, some of these ”parties” are not like the others. Jacobin, Cordelier and Feuillant all refer to people belonging to a certain political club, paying money for their membership, whereas girondins, montagnards, thermidorians, enragés, hébertists (and robespirreists that are not mentioned in the chart) all are loose compounds of people that pushed for (or were at least said to push for) the same political changes, and often were personal friends as well. The vagueness of all of this has lead to debates not only regarding what each group really stood for, but even who really belonged to them. My understanding of these groups is honestly not much deeper than what can be read on wikipedia (each group already has its own page) but to shortly summarize:

Jacobins — members of the Jacobin Club (Society of the Friends of the Constitution) which was founded in 1789 and shut down in November of 1794. It’s main quarter was on rue Saint-Honoré in Paris, but unlike the Cordeliers and Feuillants, it also set up sister clubs out in the provinces. This makes the Jacobins the biggest political group throughout the revolution in terms of official members. When it comes to ideology, the club’s first set of official reglutions, passed on February 8 1790, stated that ”the object of the Society of Friends of the Constitution is: 1, to discuss in advance the questions which must be decided in the National Assembly; 2, to work towards the re-establishment and strengthening of the constitution according to the spirit of the preamble above; 3, to correspond with other Societies of the same type which may be formed in the kingdom” as well as that ”loyalty to the constitution, dedication to defending it, respect and submission to the powers it has established, will be the first laws imposed on those who wish to be admitted to these Societies.” However, as the revolution radicalized, so did the Jacobin club.

Cordeliers — members of the Cordelier Club (also known as the Society of the Friends of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen) which existed from 1790 to 1795. Its head quarter was in the Cordeliers Convent (hence the name) in Paris, located on 15 rue de l'École de Médecine. The Cordeliers had lower fees in comparison to the Jacobins, and as a result, counted more working class men and women among its members. Its leaders were however still middle class. The Cordeliers are traditionally described as more radical than the Jacobins.

Feuillant — member of the Feuillants Club (Society of the Friends of the Constitution), founded on July 16 1791. The group held meetings in a former monastery of the Feuillant monks on Rue Saint-Honoré in Paris, hence the name. The club was for upholding the Constitution of 1791, which designated France as a constitutional monarchy.

Girondins (also sometimes known as Brissotins or Rolandins) — political group which existed within the Legislative Assembly and then National Convention, in particular the 29 deputies ordered arrested by said Convention on June 2 1793. Of these, 20 would be guillotined in Paris on October 31 the same year, while many others fled to be executed or commit suicide in order to prevent it across the following months. The name ”girondin” stem from the fact many of the groups alleged members originated from the department of Gironde. In the article The "Girondins" Were Girondins, after All (1988) Frederick A. de Luna concludes that the earliest labeling of girondins as girondins stem from April 1792, after which they grew to be frequently used by their enemies. The girondins themselves did however never use the name, and in the pamphlet J. P. Brissot, député à la Convention nationale, à tous les républicains de France ; sur la société des Jacobins de Paris (October 1792) Brissot even exclaimed ”Will the slanderers now remain silent? Will they stop pretending to believe and wanting to make believe in a faction of Gironde or of Brissot?” The girondins have traditionally been associated with 1, waging a pro-war campaign within the Legislative Assembly and the Jacobin club from December 1791 to April 1792 (as can be seen above, the first recorded labeling of girondins as girondins is from the same month said war was declared), pushing for a more liberal economy as well as seeking more ”moderate/less violent” solutions compared to the Mountain during the time of the Convention. However, there’s no actual safe connections between these goals and all the men tradionally described as girondins for as far as I’m aware. To give the word to Terror: the French Revolution and its Demons (2022) by Michel Biard and Marisa Linton:

Montagnards — member of the Mountain, a group within the Legislative Assembly and then especially the National Convention, so dubbed because its members occupied the highest benches of the hall of the assembly. I honestly don’t really know what defines this ”party” more than being opponents of the girondins. So while the latter are associated with being pro-war, for a more liberal economy and reluctant to ”violent/exceptional measures”, the Montagnards are instead described as anti-war, for a more planned economy and welcoming of more ”violent/exceptional measures.” However, like in the case with the girondins, were we to line up every person tradionally described as a montagnard and check up his stance on each of these three topics, I’m unsure if we would actually get a very unified result.

Unlike in the case of the girondins, indulgents and exagères, we have proof of the montagnards describing themselves as just that. Here is Robespierre, who might as well be called the leader/heart of the ”party,” defining what a montagnard is on June 12 1794. More than anything, it may however rather illustrate how this wasn’t a properly defined group either, as I’m sure the members of every other ”party” discussed here would be willing to describe themselves in the exact same way:

Yes, Montagnards, you will always be the boulevard of public liberty; but you have nothing in common with intriguers and perverts, whoever they may be. If they try to deceive you, if they claim to identify with you, they are no less foreign to your principles. The Mountain is nothing other than the heights of patriotism; a Montagnard is nothing other than a pure, reasonable and sublime patriot.

The fall of Robespierre marks the beginning of the end for the Mountain, many of who’s members would be expulsed, executed and exiled during the thermidorian convention.

Thermidorians — the name has its origin in the journée of 9 thermidor (July 27 1794), the day Robespierre and his allies fell from power, but it is not fully clear if it is active participation in/support of said journée, or holding power during the period that followed it, which is distinguished by its step back, for better or worse, from the more ”revolutionary measures” taken during 1793-1794 that makes someone a thermidorian. In the article ”Robbers, Muddlers, Bastards, and Bankrupts?” A Collective Look at the Thermidorians (2019) Mette Harder writes that this too is a very poorly defined group — ”Beyond their individual names, there is, however, no clear sense of who the Thermidorians were collectively, how cohesive a group they became, and what exactly they hoped to achieve while in power. Their name itself adds to this uncertainty, as it is used interchangeably to describe a specific group of reactionaries and the entire Convention post-thermidor.”

Indulgents (also sometimes known as dantonists) — group associated around Convention deputy Georges-Jacques Danton, and in particular those executed alongside him on April 5 1794. Traditionally described as driving a campaign that was about softening ”the terror” as well as pushing back from dechristianization from late 1793 up until their execution. This idea is however something that has been heavily contested in more recent years, some historians concluding the Indulgents never were a coherent group with a common goal to begin with but that this was rather something contructed by their enemies in time for their trial (see for example chapter 8 — Le chef d’un groupe indulgent ? — of Danton: le mythe et l’histoire (2016) or Camille et Lucile Desmoulins: un rêve de république (2018).

Hébertists (also known as exagères) — group associated around the journalist Jacques René Hébert, and in particular those that were executed alongside him on March 24 1794. Drove a campaign for a hardening of ”the terror” and dechristianization from late 1793 up until the execution. Like with the indulgents, it’s however hard for me to say if the members themselves identified themselves as a group or if this is a post-construction.

Enragés — just read this. I honestly had trouble finding much more.

#bottom line - don’t attach too much meaning to these ”parties ”#frev#french revolution#ask#it would be interesting with a study that actually checks up on how many people actually lined up with their ”party” in thoughts and action

113 notes

·

View notes

Note

Even during his patriotic moment he is still trying to be modest.

I’m not so sure about that…

This excess of delicacy in a man who humbly made his apology, produced its effect; it was a repetition of the tragic scene which Robespierre opened one day in the tribune, while speaking of the fury of the Brissotins against him; he tragically unbuttoned his coat, and, showing his uncovered chest, said: ”Strike, Brissotin barbarians, strike: you can take my life, if my blood can be useful to the good people whom I love.” After talking about himself for an hour, Robespierre proposes the means to save the fatherland; he wants the citizens of Paris to go and fight the rebels; but our wives and children must not remain exposed to the aristocratic fury. (Such was your language, O Robespierre, when, in the dreadful nights which preceded the massacres of September, you stirred up the rage of the assassins by your bloodthirsty declamations.) Courrier des départements, v. 8, n. 11, p. 269-171

help, i think my robespierre seems to have lost his coat while having a moment of patriotic ecstasy, what do i do?

Is the Robespierre cute?

Oh my! Where are your Robespierre's clothes!! Robespierres are very bashful beings. Even during his patriotic moment he is still trying to be modest. Please assist him in either locating his coat or obtaining a new one for him. I hear that Robespierres really enjoy striped coats, so I recommend obtaining one of those if possible. Perhaps it would be beneficial to speak (gently!) to your Robespierre about having fits like this. I fear he will be embarrassed after a while. Best of luck, citoyen!

Verdict: Yes, this Robespierre is cute- but tell him to put some clothes on.

#please tell me ne at least kept a shirt on#or did he speak for a full hour with his chest bare??#nightmare fuel

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

PITT

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, Jonatan Israel claims that Robespierre made use of "semi-criminal" individuals to fill the posts in the Paris revolutionary tribunal and in the Paris commune. Is there any evidence of that or is Jonathan Israel's elitism speaking?