#Bishops' Bible of 1568

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Jesus' Food

Iesus sayth vnto them: my meate is to do the wyll of hym that sent me, and to finishe his worke. — John 4:34 | Bishops' Bible of 1568 (BB1568) Bishops' Bible of 1568 (written in old English) © 2023 by Berean Bible. All rights Reserved. Cross References: Psalm 40:8; Matthew 3:15; Luke 2:49; John 5:30; John 5:36; John 6:38; John 8:29

#Jesus#food#obedience#God's will#work (completed)#John 4:34#Gospel of John#New Testament#BB1568#Bishops' Bible of 1568#Berean Bible

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Least Amount Of Stupid

“Whoever is simple (easily led astray and wavering), let him turn in here! As for him who lacks understanding, [God’s] Wisdom says to him, Come, eat of My bread and drink of the [spiritual] wine which I have mixed. Leave off, simple ones [forsake the foolish and simpleminded] and live! And walk in the way of insight and understanding.” Proverb 9:4-6AMPC

Have you ever done something stupid? After we’ve seen the end result of what we did, we hold our heads in our hands, moaning, ‘what have I done.’ Growing up, Dad often quoted, “There is a way that seems right to a man, but its end is the way to death.” Proverbs 14:12ESV. The way of the lie is so easy to follow. Where we are in history, the popular way, leads to death and destruction.

I had a crazy notion, when I became born again in Christ— automatically I was wise. Yet I can look back over the years and see stupid mistakes. Time and again, Jesus has had to bail us out financially. Decisions made concerning our children didn’t bear good fruit. Where did the frequent wrong ideas come from? Years of not consulting Christ, instead doing things the way that ‘felt right.’

Changes had to take place in me. “The reverent and worshipful fear of the Lord is the beginning (the chief and choice part) of Wisdom, and the knowledge of the Holy One is insight and understanding” Proverbs 9:10AMPCAlthough I loved God, I hadn’t revered Him enough to begin seeking consistently His ways. Too much was done on the move without prayers for instructions.

Instructions are given in James 1:5-8AMPC “ If any of you is deficient in wisdom, let him ask of the giving God [Who gives] to everyone liberally and ungrudgingly, without reproaching or faultfinding, and it will be given him. Only it must be in faith that he asks with no wavering (no hesitating, no doubting). For the one who wavers (hesitates, doubts) is like the billowing surge out at sea that is blown hither and thither and tossed by the wind. For truly, let not such a person imagine that he will receive anything [he asks for] from the Lord, [For being as he is] a man of two minds (hesitating, dubious, irresolute), [he is] unstable and unreliable and uncertain about everything [he thinks, feels, decides]” James 1:5-8AMPC. My prayers became, ‘Lord I don’t know how, give me wisdom.’ Changes began to form in the results of decisions made.

When we waffle back and forth between two ideas we’re “simple.” The GNT of our text reads, “ignorant people.” Kenneth Copeland translates this scripture as ‘stupid.’ Bishop’s Bible 1568 writes “Who so is without knowledge,” sounds like Copeland might be right. Wavering back and forth is stupid and I’ve been there.

Most of the devotionals, the Lord leads me to write, are about— ‘I’ve tried the wrong way. God’s way is better.’ At my age, I want the least amount of ‘stupid’ as I can possibly have. In our society today, Believers can afford ‘stupid’ even less than in years past. We’re to be as little Jesus Christs walking around doing what Jesus did. There’s not one verse indicating Jesus did things ignorantly. He was always on top of every situation. Make a pledge to yourself today to seek God’s wisdom before finishing your next sentence; completing your next chore, or doing anything. Or not. It’s your choice. You choose.

LET’S PRAY: Almighty God, God of wisdom thank You for making wisdom available to us. We don’t have to live in a world of constant mistakes. All we need to do is ask You for wisdom. Lord, please give us the wisdom we need, in the name of Jesus Christ.

by Debbie Veilleux

Copyright 2024 You have my permission to reblog this devotional for others. Please keep my name with this devotional, as author. Thank you.

#Jesus Christ#word of god#lord of lords#god#holy spirit#it's your choice#devotional#stupid#back and forth#top#revere#wrong way#wisdom#love#hope#faith

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE DESCRIPTION OF SAINT JOHN CHRYSOSTOM The Golden-Mouthed Bishop and Doctor of the Church Feast Day: September 13

"For I always say: Lord, your will be done; not what this fellow or that would have me do, but what you want me to do. That is my strong tower, my immovable rock, my staff that never gives way."

We usually hear people saying that everything is relative, that we do not need to tell someone what to do or what is right or wrong, they may even quote the verse: 'Thou shalt not judge.'

But God also gave us the ability to reason out, to know what is right or wrong through our conscience and the ability to help each other in the formation of our consciences. Evil usually happens when we tolerate evil and we do not use our ability to denounce it.

This saint was a very important figure in the early Church and his example still radiates for us today. He is St. John Chrysostom, one of the original Doctors of the Eastern (Greek) Church, together with Sts. Basil, Gregory Nazianzen and Athanasius.

He was born in Antioch (now part of Turkey) in c. 347 from Greek parents from Syria. His father died soon after his birth and he was raised by his mother together with his elderly sister. He was baptized in 368 and received the ministry of a lector. He was educated under the pagan Libanus, whom he acquired the skills in rhetorics and studied Christian theology under Diodore of Tarsus whom he acquired the vast knowledge of the Bible. He lived an ascetic life and became a hermit before being ordained as a deacon in 381 by Meletius and as a priest in 386 by Flavian.

Both were not in communion with Rome and later, John was instrumental in leading their followers in reconciliation between Antioch and Rome. For twelve years, he gained popularity because of eloquence in public speaking. He emphasized charity to the poor and spoke against abuse of wealth and power. His time as a hermit made him memorize the Bible and explained it in relation to everyday life; his style of preaching were efficient that many pagans were converted to the Faith.

He was appointed as the Archbishop of Constantinople (present-day Istanbul, Turkey) and was controversial for refusal to host lavish banquets, deposed those bishops and priests who have 'bought' their offices, banned the travelling preachers who ask for money and he openly criticized the opulence of the royalty. He also founded hospitals in the city and became popular among the commoners, but unpopular among the clergy and prominent citizens.

He was accused of heresy and unchastity by his enemies and was deposed in the Synod of Oaks in 403, orchestrated by the emperor Theodosius and his wife Eudoxia.

He was exiled in a far and poor town of Cucusus and then to Pythius (now part of Georgia) and died while on his way there on September 14, 407. His recorded last words were: 'Glory be to God in all things.'

His reputation was restored a decade after his death, he was referred to as 'Chysostomos' meaning 'golden-mouthed', recognized as a Church Father in the Council of Chalcedon in 451, and a Doctor of the Church in 1568. He is the patron of preachers, orators and educators, as well as against epilepsy.

Like St. John Chrysostom, may the words be coming out of our mouths be 'golden', valuable and goes beyond time, and may his example inspire us to reject honor and reputation if these will mean tolerance of misguided values and approval of evil.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The King James Bible

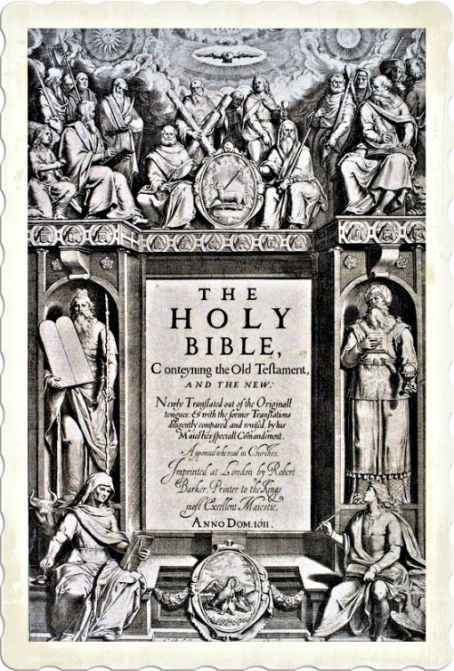

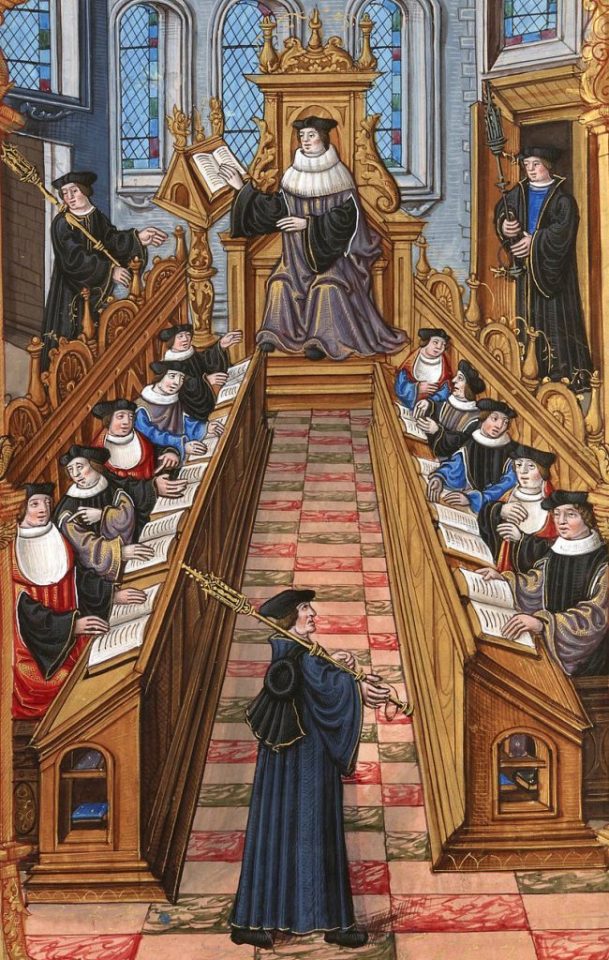

The King James Bible A feast is made for laughter, and wine maketh merry: but money answereth all things. King James Bible Ecclesiastes 10:19 All things are full of labour; man cannot utter it: the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing. King James Bible Ecclesiastes 1:8 The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun. King James Bible Ecclesiastes 1:9 And I saw the dead, small and great, stand before God; and the books were opened: and another book was opened, which is the book of life: and the dead were judged out of those things which were written in the books, according to their works. King James Bible Revelation 20:12 And when he had spoken these things, while they beheld, he was taken up; and a cloud received him out of their sight. King James Bible Acts 1:9 I am not worthy of the least of all the mercies, and of all the truth, which thou hast shewed unto thy servant; for with my staff I passed over this Jordan; and now I am become two bands. King James Bible Genesis 32:10 A great influence on the English language occurred in 1611, five years before Shakespeare died. This was the publication of the King James's translation of the Holy Bible, a 14th-century translation by John Wycliffe, The King James Version, as it is called, was completed in 1611. If Shakespeare gave the language its greatest poetry, the Bible gave it much of its greatest prose. This version of the Bible was not written by one man but by a team or committee of some 47 scholars. We know very little about them except that they were certainly men of literary genius, and we have their finished work as a proof.

King James Bible The followers of John Wycliffe undertook the first complete English translations of the Christian scriptures in the 14th century. These translations were banned in 1409 due to their association with the Lollards. The Wycliffe Bible pre-dated the printing press but it was circulated very widely in manuscript form, often inscribed with a date which was earlier than 1409 in order to avoid the legal ban. Because the text of the various versions of the Wycliffe Bible was translated from the Latin Vulgate, and because it also contained no heterodox readings, the ecclesiastical authorities had no practical way to distinguish the banned version; consequently, many Catholic commentators of the 15th and 16th centuries (such as Thomas More) took these manuscripts of English Bibles and claimed that they represented an anonymous earlier orthodox translation. In 1525, William Tyndale, an English contemporary of Martin Luther, undertook a translation of the New Testament. Tyndale's translation was the first printed Bible in English. Over the next ten years, Tyndale revised his New Testament in the light of rapidly advancing biblical scholarship, and embarked on a translation of the Old Testament. Despite some controversial translation choices, and in spite of Tyndale's execution on charges of heresy for having made the translated Bible, the merits of Tyndale's work and prose style made his translation the ultimate basis for all subsequent renditions into Early Modern English. Under the leadership of John Calvin, Geneva became the chief international centre of Reformed Protestantism and Latin biblical scholarship. The English expatriates undertook a translation that became known as the Geneva Bible. This translation, dated to 1560, was a revision of Tyndale's Bible and the Great Bible on the basis of the original languages. Soon after Elizabeth I took the throne in 1558, the flaws of both the Great Bible and the Geneva Bible (namely, that the Geneva Bible did not "conform to the ecclesiology and reflect the episcopal structure of the Church of England and its beliefs about an ordained clergy") became painfully apparent. In 1568, the Church of England responded with the Bishops' Bible, a revision of the Great Bible in the light of the Geneva version.

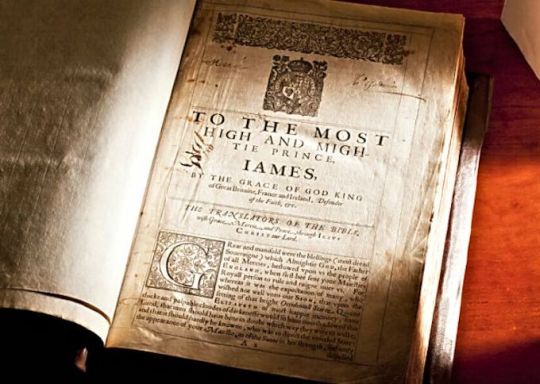

King James I While officially approved, this new version failed to displace the Geneva translation as the most popular English Bible of the age - in part because the full Bible was only printed in lectern editions of prodigious size and at a cost of several pounds. Accordingly, Elizabethan lay people overwhelmingly read the Bible in the Geneva Version - small editions were available at a relatively low cost. At the same time, there was a substantial clandestine importation of the rival Douay–Rheims New Testament of 1582, undertaken by exiled Roman Catholics. This translation, though still derived from Tyndale, claimed to represent the text of the Latin Vulgate. In May 1601, King James VI of Scotland attended the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland at St Columba's Church in Burntisland, Fife, at which proposals were put forward for a new translation of the Bible into English. Two years later, he ascended to the throne of England as James I. In January 1604, King James convened the Hampton Court Conference, where a new English version was conceived in response to the problems of the earlier translations perceived by the Puritans, a faction of the Church of England. James gave the translators instructions intended to ensure that the new version would conform to the ecclesiology - and reflect the episcopal structure - of the Church of England and its belief in an ordained clergy. The translation was done by 6 panels of translators (47 men in all, most of whom were leading biblical scholars in England) who had the work divided up between them: the Old Testament was entrusted to three panels, the New Testament to two, and the Apocrypha to one. In common with most other translations of the period, the New Testament was translated from Greek, the Old Testament from Hebrew and Aramaic, and the Apocrypha from Greek and Latin. In the Book of Common Prayer (1662), the text of the Authorized Version replaced the text of the Great Bible for Epistle and Gospel readings (but not for the Psalter, which substantially retained Coverdale's Great Bible version), and as such was authorized by Act of Parliament. By the first half of the 18th century, the Authorized Version had become effectively unchallenged as the English translation used in Anglican and English Protestant churches, except for the Psalms and some short passages in the Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England. Over the course of the 18th century, the Authorized Version supplanted the Latin Vulgate as the standard version of scripture for English-speaking scholars. With the development of stereotype printing at the beginning of the 19th century, this version of the Bible became the most widely printed book in history, almost all such printings presenting the standard text of 1769 extensively re-edited by Benjamin Blayney at Oxford, and nearly always omitting the books of the Apocrypha. Today the unqualified title "King James Version" usually indicates this Oxford standard text. The outstanding prose works of the Renaissance are not so numerous as those of later ages, but the great translation of the Bible, called the King James Bible, or Authorized Version, published in 1611, is significant because it was the culmination of two centuries of effort to produce the best English translation of the original texts, and also because its vocabulary, imagery, and rhythms have influenced writers of English in all lands ever since. Similarly sonorous and stately is the prose of Sir Thomas Browne, the physician and semiscientific investigator. His reduction of worldly phenomena to symbols of mystical truth is best seen in Religio Medici (Religion of a Doctor), probably written in 1635. It is impossible to estimate the importance or effect of the King James Bible on the English language. Listen to the simplicity but the power of the prose in these lines from St Paul's first epistle to the Corinthians: When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face. now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known. And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity.

King James Holy Bible What we call "modern English" comes from the period immediately following the publication of the Bible and Shakespeare's death. We generally consider 1640 to be the beginning of modern English, and the language has changed remarkably little ever since. By the 17th century the language had discarded its grammatical complexities: no more declensions and a minimum use of the subjunctive. Grammatical gender had disappeared and English became the only European language to employ natural gender that is using feminine pronouns for things feminine, masculine pronouns for things masculine and the neuter "it" for everything else. How much simpler than in, say, German where a table is "he", a postage stamp is "she" and a girl is "it". Then too, English gave up its second person singular - what on the Continent is known as "the familiar form" expressed by to in Italian. Spanish and French and du in German. In English this was "thou" and its use became restricted to poetry, church and a few provincial dialects. Instead, English, as you well know, now simply uses the plural form "you" for everyone and for all. In place of the grammatical complexities of Old English, the language became more exact in other ways. Modern English has a fixed system of word order more exact than exists in any other language and a highly sophisticated use of tenses which causes so much difficulty for a foreign student. So the King James Bible, also known as the Authorized Version, has had a profound influence on the English language since its publication in 1611 and certainly played a significant role in standardizing the English language. In fact its translators sought to create a version that would be accessible and understandable to all English speakers, regardless of their social status or region. This helped to establish a uniform form of English across different communities. What's more it contributed to a great vocabulary enrichment since the translators of the King James Bible used rich and eloquent language, drawing heavily from the literary traditions of the time. They introduced many words and phrases into the English language that have since become commonplace, including "eye for an eye," "the salt of the earth," "scapegoat," "fly in the ointment," and "out of the mouth of babes." Furthermore The King James Bible popularized certain phrasal patterns and idiomatic expressions that are still in use today. Its language has permeated various aspects of English-speaking culture, including literature, politics, and everyday speech. The King James Bible has also had a profound impact on the moral and ethical values of English-speaking societies. Its teachings and narratives have shaped the cultural and religious landscape of the English-speaking world, influencing everything from laws and social norms to literature and art. Therefore the King James Bible's influence on the English language is vast and enduring, and its legacy continues to be felt in both religious and secular contexts to this day. For example the King James Bible has influenced numerous English writers and poets over the centuries, including William Shakespeare, John Milton, John Bunyan, and John Donne. Its majestic language and poetic style have left an indelible mark on English literature. Many famous literary authors have been influenced by the Bible, as its stories, themes, and language have permeated Western culture for centuries. Here are some notable authors whose works show significant influence from the Bible. First we can quote John Milton, whose epic poem "Paradise Lost" draws heavily on biblical themes, particularly those found in the book of Genesis. The poem explores the Fall of Man, the rebellion of Lucifer, and other biblical narratives. Or Shakespeare's works that are filled with biblical allusions and imagery. Many of his plays, such as "Hamlet," "Macbeth," and "King Lear," contain references to biblical stories and characters. But how not to mention John Bunyan, the author of "The Pilgrim's Progress," who was deeply influenced by the Bible. His allegorical tale draws heavily on biblical themes and imagery to explore the Christian journey. And also Herman Melville's masterpiece, "Moby-Dick," that contains numerous biblical allusions and references. The novel explores themes of good and evil, redemption, and the search for meaning - all of which are deeply rooted in biblical tradition.

King James I of England and Scotland Even poets such as Emily Dickinson whose poetry often reflects her deep engagement with the Bible. Many of her poems explore religious themes, and she frequently incorporates biblical imagery and language into her work. Then there is T.S. Eliot, a renowned modernist poet, who drew extensively on the Bible in his poetry. His famous work "The Waste Land" contains numerous biblical references and allusions, reflecting his interest in Christian theology and symbolism. But also Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, George Eliot, and Thomas Carlyle were influenced by the Bible. Last but not least we can remember Fyodor Dostoevsky. Dostoevsky, though not writing in English, was influenced by the Bible in his Russian novels. His exploration of moral and existential themes in works like "Crime and Punishment" and "The Brothers Karamazov" resonates with biblical ideas of sin, redemption, and the human condition. Dubliners is a collection of fifteen short stories by James Joyce, and the book contains a story with this title “A Little Cloud” that alludes to a Biblical passage, I Kings 18:44: “And it came to pass at the seventh time, that he said, Behold, there ariseth a little cloud out of the sea, like a man's hand. And he said, Go up, say unto Ahab, Prepare thy chariot, and get thee down that the rain stop thee not.” The little cloud is the harbinger of a great rain, which the prophet Elijah summons to end a drought. The title "A Little Cloud" may also evoke the biblical phrase from the book of Job, where God speaks to Job out of the whirlwind, saying: "Hast thou entered into the treasures of the snow? or hast thou seen the treasures of the hail, which I have reserved against the time of trouble, against the day of battle and war?" (Job 38:22-23, King James Version). This passage refers to the idea of small clouds holding great potential, possibly reflecting the protagonist's aspirations and dreams in the story. As a matter of fact in "A Little Cloud," the protagonist, Little Chandler, dreams of becoming a successful writer like his friend Gallaher, who has achieved fame abroad. However, his dreams clash with the realities of his mundane life in Dublin, where he is trapped in a dull job and responsibilities of family life. The story explores themes of disillusionment, longing for escape, and the tension between dreams and reality. The biblical allusion could be interpreted as suggesting that even small aspirations or desires, represented by "a little cloud," can carry significant weight and have profound implications for individuals, especially when they collide with the harsh realities of life, akin to the "time of trouble" mentioned in the biblical passage. To conclude this article we must consider that the Bible is one of the most widely printed and distributed books in history. Millions upon millions of copies of the Bible have been printed in numerous languages and editions over the centuries. It has been translated into thousands of languages and dialects, making it accessible to people all around the world. The Bible has had a profound impact on countless individuals across diverse cultures and time periods. You can also visit these pages: www.kingjamesbibleonline.org www.biblestudytools.com Origins of proverbs Wisdom of proverbs Quotes by authors Quotes by arguments Thoughts and reflections Essays with quotes Read the full article

#1611#Aramaic#Bible#church#cloud#common#Dubliners#Early#England#English#Genesis#Greek#Hebrew#james#John#Joyce#king#literature#Milton#modern#New#Old#Oxford#poetic#prayer#prose#Puritans#scholars#Shakespeare#style

0 notes

Text

the interesting thing about the kjv was that it already sounded a bit outdated when it was published--it was a light revisions of the bishop's bible from 1568, which IIRC was itself based on an even older version. the kjv only came into wider use gradually, and didn't become the most popular version of the bible in the english speaking world until the end of the 18th century

i really like how religious texts result in an immense amount of effort being focused on the problem of translation (for that particular text) i mean, even the really great nonreligious works havent had a tenth of the work, debate, thought, controversy put into translating them that religious texts have. its so cool! especially because given that theyre old so you cant be a native speaker of the language they were written in (i mean, obviously people speak greek and hebrew, but theyre different languages than koine and biblical hebrew)

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

HISTORY OF ENGLISH BIBLE: The Bishops' Bible (1568)

HISTORY OF ENGLISH BIBLE: The Bishops’ Bible (1568)

Meanwhile, there was one quarter in which the Geneva Bible could hardly be expected to find favor, namely, among the leaders of the Church of England. Elizabeth herself was not too well disposed towards the Puritans, and the bishops, in general, belonged to the less extreme party in the church. On the other hand, the superiority of the Genevan to the Great Bible could not be contested.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

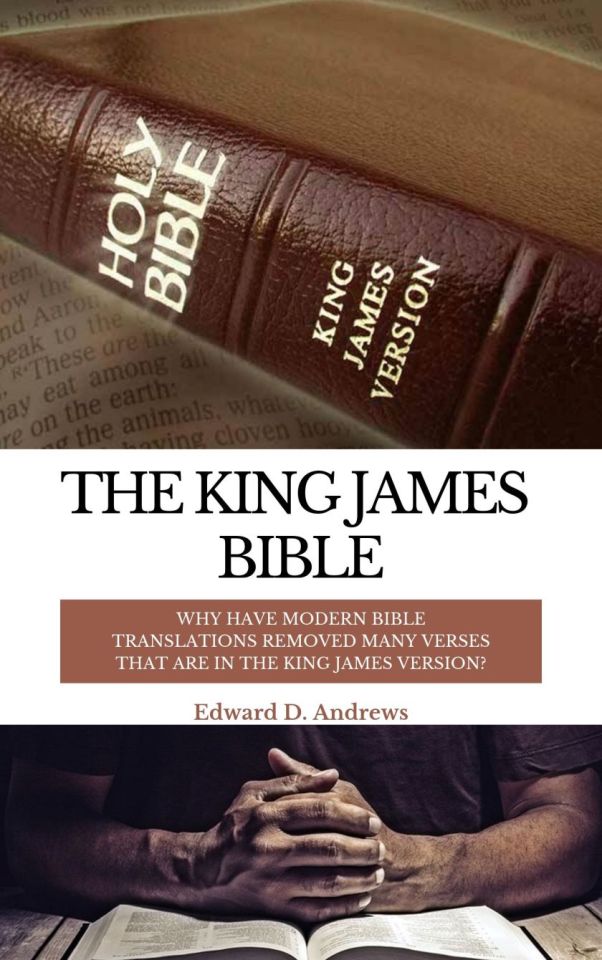

EARLY TUDOR EDUCATION

“Early in the 16th century, it became a fashionable for upper0class girls to receive an education, something which benefitted Henry VIII’s two daughters, Princess Mary and Elizabeth (Henry VIII’s daughter with his second wife, Anne Boleyn), their kinswoman Lady Jane Grey, and other girls of the gentry and nobility.

One of Elizabeth’s tutors was Roger Ascham (1515-1568), who published a book called The Scholemaster on his revolutionary methods for ensuring that he got the best out of his pupils. Ascham believed that great care should be taken to ensure that the child learned in the correct way, since “these faults, taking once root in youth, be never or hardly, plucked away in age”. He was a benign schoolmaster, arguing that a child should be praised when they did well, since “I assure you, there is no whetstone, to sharpen a good wit and encourage a will to learning, as is praise.” He also felt that children who tried their best but made mistakes should not be punished, arguing that scholars should not be made to fear their tutor. As far as Ascham was concerned, it was essential to instill a love of learning into his pupils, something which he achieved with Princess Elizabeth, who continued throughout her lifetime. The future Elizabeth I was extremely well educated, speaking French, Spanish, Italian, as well as reading Latin and Greek. She was Ascham’s star pupil, with the tutor declaring that she put the young men of England to shame with her “excellent gifts of learning. Educational provision also improved for children lower down the social scale in Tudor England. A number of grammar schools were founded, with their curriculums based on humanist principles and focusing on Latin and Greek. These tended to cater to sons of the gentry and lower nobility and boys would start at the age of seven. The day at grammar school was a long one – of ten starting before sunrise and finishing after the sunset. For poorer children, there might be a parish school close to their home, where the vicar would teach them to read or write. Although some tutors, such as Roger Ascham, had enlightened views on punishments most Tudor schoolboys would expect to be beaten if they made an error or misbehaved. MAGDALEN COLLEGE SCHOOL, OXFORD

During the early Tudor period, Magdalen College School in Oxford offered young boys the best school education that they could get in England It opened at Easter 1480, moving into its permanent building just inside the gates of Magdalen College, that autumn. The school offered free tuition to its pupils, who sat at their lessons between 5 am and 5 pm every day, only breaking for breakfast and lunch. The schoolroom, on the ground floor of the two-story school house, had room for 100 scholars, who were instructed by two tutors. To keep order, the pair used a birch cane to chastise the boys. To be educated there was a great privilege, with the school the first in England to teach classical Latin in accordance with humanist principles, rather than the corrupted Latin of the medieval period. This allowed the scholars to read classical works in the original language. Many of the pupils went on to become bishops and great thinkers, with William Tyndale, who translated the Bible into English, one of the school’s alumni.”

- TUDOR TREASURY by Elizabeth Norton

#Education#renaissance#dailytudors#book quote#book: tudor treassury#queen elizabeth i of england#roger ascham#william tyndale#magdalen college#oxford#history#humanism

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is the best version of the Bible for the most accurate English translation?

I'll try to answer this ask with the books:

Treasure and Tradition from the Saint Agustine Academy Press

My Catholic Faith: A Manual of Religion by Bishop Louis LaRavoire

So I decided include the Least Trusted Bibles™ and maybe the Failed Protestant English Translations™ because it's fun. This has nothing to do with the ask, and I'll probably just answer quickly at the end.

So here's the list of rejects:

John Wycliffe's Bible (1382-1395) He rejected the church, relied only on the teachings of the bible, had followers called Lollards and got declared a heretic.

Martin Luther's Bible (1522-1534) "Martin Luther's rejection of church teaching led him to accept scripture alone as a source of divine revelation. Therefore he sought to create a bible for the common man using vernacular German. Seeking to avoid the Catholic Vulgate and having no access to original manuscripts, Luther consulted recently printed copies of the Septuagint and the Hebrew Masoretic Text. Though his bible was unprecedented in it's popularity and influence, it is universally noted that his translation contained significant biased based on his beliefs." I just think it's funny how he used the Septuagint and also used the book that didn't trust the Septuagint.

William Tyndale's Bible (1525-1536) This one is truly a failure because he was inspired by Luther's Bible but didn't trust Luther's Bible enough to accept it so he made his own but also used heterodox commentaries of Luther's Bible... and people say women give off mixed signals but clearly they've never seen William Tyndale. Anyways, this translation was absolutely demolished by my dude St. Thomas who pointed out biased mistranslations.

The Great Bible (1538) King Henry the VIII's first authorized English translation of the bible. Imagine Tyndale's but worse because the author Myles Coverdale (fanboy of Tyndale) tried amending it with The Vulgate and Luther's Bible. (Remember how Luther was like I don't wanna use The Vulgate! Yeah I guess they didn't care)

The Geneva Bible (1560) because people hate to see a girlboss winning, protestants fled to Geneva during the reign of the Catholic Queen Mary (the girlboss in question). They created The Geneva Bible.

The Bishop's Bible (1568) At least they tried being a bit more logical in this one. A bit. The English bishops under Elizabeth the 1st were "dissatisfied with the Great Bible due to it's translation from the Vulgate, yet the Geneva Bible was far too Calvinistic" You see where there's like a little bit of a thought occuring? Anyways it's size and cost were problems, so people kept using the Geneva Bible.

King James Version (1604-1611) Cringe. The Non-Catholic manuscripts were preferred in making this book and it shows. "resulting in significant changes, including the canon of books" I like how the book My Catholic Faith has a really good little paragraph about it more or less about this. "Having rejected Tradition, Protestants cannot be certain that the books they have accepted are genuine... Protestant Bibles, the most popular of which is called "The King James Version" omit all or parts of The books of Tobias, Judith, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Baruch, Machabees (I and II) and parts of Esther and Daniel. Luther rejected parts of St. James because the apostle said that faith without works is dead. Luther and followers omitted the Apocalypse, the Epistle to the Hebrews, and the Epistle to St. Jude."

Which ones can you trust then?

The Clementine Revision of the Vulgate (if that still exists anyways)

The Douay-Rheims Bible (you'll love this one)

Challoner's Revision of the Douay-Rheims Bible (The Catholic Church's officially approved English bible)

If you ever go back in time I advise getting the original Vulgate (by St. Jerome). I also advise that once you return to get a bulletproof vest and other protective gear because I will go after you want you to be safe from heathens.

#asks#i probably put too much work in this#and way too little at the end but i had fun.#and if this has an error or something kill me

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The King James Version - Early modern printing press (6/?)

On May 2, 1611 the King James Version (KJV), or the Authorized Version, was published. This translation had a big influence on English literary style. It was long accepted as the standard English Bible (until the early 20th century).

James I was the successor of Elizabeth I, whose reign imposed a high degree of uniformity upon the Church of England. In her reign, Protestantism was reinstated as the official religion after the short, Catholic reign of Mary I. When James I became king, he requested that the English Bible should be revised because existing translations “were corrupt and not answerable to the truth of the original”.

Before the introduction of the KJV, the Great Bible, authorized by Henry VIII in 1538, was relatively popular, however the editions did contain several inconsistencies. Clergy liked the later Bishops’ Bible (1568), but this version wasn’t authorized by Elizabeth I, nor gained wide acceptance. The Geneva Bible (1557) was the most popular English translation, made by English protestants living in exile during the reign of Mary I.

While a translation of a Bible might now seem very normal, but translating the Bible has been a point of heavy debate. It played an important role in the religious history of Early Modern Europe. I think it is very interesting.

Want to read more?

John O’Malley, Trent and All That, Renaming Catholicism in the Early Modern Era, Cambridge MA, 2000, Chapter II: 'Hubert Jedin and the Classic Position', pp. 46-71

François, Wim. “Vernacular Bible Reading in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe: The «Catholic» Position Revisited.” The Catholic Historical Review, vol. 104, no. 1, 2018, pp. 23–56.

Britannica, "King James Version". Encyclopedia Britannica, 2 Feb. 2021.

Corbellini, Sabrina. “Reading, Writing, and Collecting: Cultural Dynamics and Italian Vernacular Bible Translations.” Church History and Religious Culture, vol. 93, no. 2, 2013, pp. 189–216.

#history#religious history#book history#early modern europe#printing press#james i#english history#protestantism#bible studies

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today the Church remembers William Tyndale, Priest and Martyr.

Ora pro nobis.

William Tyndale (c. 1494 – c. 6 October 1536) was an English scholar who became a leading figure in the Protestant Reformation in the years leading up to his execution. He is well known as a translator of the Bible into English, influenced by the works of Erasmus of Rotterdam and Martin Luther.

A number of partial English translations had been made from the 7th century onwards, but the religious ferment caused by Wycliffe's Bible in the late 14th century led to the death penalty for anyone found in unlicensed possession of Scripture in English, although translations were available in all other major European languages.

Tyndale worked during a Renaissance of scholarship, which saw the publication of Reuchlin's Hebrew grammar in 1506. Greek was available to the European scholarly community for the first time in centuries, as it welcomed Greek-speaking intellectuals and texts following the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Notably, Erasmus compiled, edited, and published the Greek Scriptures in 1516. Luther's German Bible appeared in 1522.

Tyndale's translation was the first English Bible to draw directly from Hebrew and Greek texts, the first English translation to take advantage of the printing press, the first of the new English Bibles of the Reformation, and the first English translation to use Jehovah ("Iehouah") as God's name as preferred by English Protestant Reformers. It was taken to be a direct challenge to the hegemony of both the Catholic Church and the laws of England maintaining the church's position.

A copy of Tyndale's The Obedience of a Christian Man (1528), which some claim or interpreted to argue that the king of a country should be the head of that country's church rather than the pope, fell into the hands of the English King Henry VIII, providing a rationale to break the Church in England from the Catholic Church in 1534. In 1530, Tyndale wrote The Practyse of Prelates, opposing Henry's annulment of his own marriage on the grounds that it contravened Scripture. Fleeing England, Tyndale sought refuge in the Flemish territory of the Catholic Emperor Charles V. In 1535, Tyndale was arrested and jailed in the castle of Vilvoorde (Filford) outside Brussels for over a year. In 1536, he was convicted of heresy and executed by strangulation, after which his body was burnt at the stake. Tyndale, before being strangled and burned at the stake in Vilvoorde, cries out, "Lord, open the King of England's eyes". His dying prayer seemed to find its fulfilment just one year later with Henry's authorisation of the Matthew Bible, which was largely Tyndale's own work, with missing sections translated by John Rogers and Miles Coverdale. Within four years, four English translations of the Bible were published in England at the king's behest, including Henry's official Great Bible. All were based on Tyndale's work.

Tyndale's translation of the Bible was plagiarized for subsequent English translations, including the Great Bible and the Bishops' Bible, authorised by the Church of England. In 1611, the 47 scholars who produced the King James Bible drew significantly from Tyndale's original work and the other translations that descended from his.One estimate suggests that the New Testament in the King James Version is 83% Tyndale's words and the Old Testament 76%. Hence, the work of Tyndale continued to play a key role in spreading Reformation ideas across the English-speaking world and eventually across the English speaking world.

As well as individual words, Tyndale also coined such familiar phrases as:

* my brother's keeper

* knock and it shall be opened unto you

* a moment in time

* fashion not yourselves to the world

* seek and ye shall find

* ask and it shall be given you

* judge not that ye be not judged

* the word of God which liveth and lasteth forever

* let there be light

* the powers that be

* the salt of the earth

* a law unto themselves

* it came to pass

* the signs of the times

* filthy lucre

* the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak (which is like Luther's translation of Matthew 26,41: der Geist ist willig, aber das Fleisch ist schwach; Wycliffe for example translated it with: for the spirit is ready, but the flesh is sick.)

* live, move and have our being

The translators of the Revised Standard Version in the 1940s noted that Tyndale's translation, including the 1537 Matthew Bible, inspired the translations that followed: The Great Bible of 1539; the Geneva Bible of 1560; the Bishops' Bible of 1568; the Roman Catholic Douay-Rheims Bible of 1582–1609; and the King James Version of 1611, of which the RSV translators noted: "It [the KJV] kept felicitous phrases and apt expressions, from whatever source, which had stood the test of public usage. It owed most, especially in the New Testament, to Tyndale".

Almighty God, you planted in the heart of your servant William Tyndale a consuming passion to bring the Scriptures to people in their native tongue, and endowed him with the gift of powerful and graceful expression and with strength to persevere against all obstacles: Reveal to us your saving Word, as we read and study the Scriptures, and hear them calling us to repentance and life; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

#father troy beecham#christianity#troy beecham episcopal#jesus#father troy beecham episcopal#saints#god#salvation#peace#martyrs#Bible

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

[PDF] Download KJV, Personal Size Reference Bible, Sovereign Collection, Leathersoft, Brown, Red Letter, Comfort Print: Holy Bible, King James Version -- Thomas Nelson Publishers

Download Or Read PDF KJV, Personal Size Reference Bible, Sovereign Collection, Leathersoft, Brown, Red Letter, Comfort Print: Holy Bible, King James Version - Thomas Nelson Publishers Free Full Pages Online With Audiobook.

[*] Download PDF Visit Here => https://best.kindledeals.club/0785239235

[*] Read PDF Visit Here => https://best.kindledeals.club/0785239235

This beautiful Bible edition honors the legacy of the King James Version Bible in a convenient portable size with essential study tools and traditional red-letter text for the Words of Christ.The Sovereign Collection continues Thomas Nelson's long history and stewardship publishing Bibles. King James Sovereign Collection editions draw from the legacy of the trustworthy and timeless KJV with elegant drop cap illustrations leading into each chapter, the exclusive Comfort Print typeface inspired by centuries-old Thomas Nelson editions, and more classic Bible details.In 1611, the King James Version Bible, also known as the Authorized Version, was published. Nearly 50 of the day’s finest scholars, all from the Church of England, had been organized into six groups for the task. Using the Bishop’s Bible of 1568 as the basis for this revision, the Old Testament was translated from Hebrew and the New Testament from Greek. The completed work was then peer-reviewed before being sent to bishops

0 notes

Text

Rumination #17: Exactly what are the "Ten Words" (or what some people call the "Ten Commandments")?

Everyone seems to know about a portion of Scripture they call the "Ten Commandments." They were written on tablets of stone; and they supposedly represent the baseline of morality for two religions: Judaism and Christianity. But what exactly are they?

First, they are never called the "Ten Commandments" in Scripture. It is quite odd that they ever earned this name. They are listed in Exodus 20:2-17 and Deuteronomy 5:6-21. They are called the "the Ten Words" in Exodus 34:28; Deuteronomy 4:13; and Deuteronomy 10:4. It is from these three passages that they earned their title. In Hebrew, they are called "aseret ha-devarim" [the ten words]. In the Greek Septuagint they are "deca logos" [ten words]. In the Latin Vulgate, they are "verba decem" [ten words]. So how did they earn the English name, "the Ten Commandments"?

The Wycliffe Bible, one of the earliest English Bibles (1395 CE) translated "aseret ha-devarim" as "ten words." The Coverdale Bible (1535 CE) translates the phrase as "ten verses." Virtually every English Bible from that time on has translated the phrase as "Ten Commandments." So what happened between the Wycliffe translation and the Bishop's Bible in 1568? The Protestant Reformation. The Geneva and Bishop's well-established the phrase "the Ten Commandments"; but the Authorized Version [King James Bible] of 1611, theologically sealed the matter. They were to be called "the Ten Commandments" from then on.

So, does it really matter? Certainly, the ten words of Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5 are imperatives, aren't they? Traditional Judaism lists them as part of the "613 mitzvot" [commandments]. So, what difference does it make if they are incorrectly translated into English?

Beloved, there is a reason they went from being "words" to "commandments" and it isn't out of reverence for mitzvot - it is the opposite. The word "devarim" [words] carries with it the promise of liberty and life - after all, we are to live by "every word that proceeds from the mouth of HaShem." (Deuteronomy 8:3; Matthew 4:4) To some, the word "commandments" bears the appropriate negative connotation. There is a theological reason "words" became "commandments."

To be fair, some of the men of the Protestant Reformation considered these words as valid and operable in the lives of believers. Sadly, those same men were those that promoted a heretical theology called "Supercessionism" or "Replacement Theology." The real force behind the denigrating of the Ten Words is to be found in Dispensationalism. It is there that the Ten Words became a relic of a past "dispensation" - the "dispensation of law" which in the dispensationalist's mind is the antithesis to the "dispensation of grace."

It was not the name "Ten Commandments" that reduced these words of life to "the Law carved on stone" in Christianity - it was the theology, whether Supercessionist as with Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Presbyterianism; or Dispensationalism as with Baptist, Pentecostalism, or Evangelicalism (and sadly, some forms of Messianic Judaism). The theology aims to do the same thing in this regard: relegate the Ten Words to cold hard tablets of stone.

That is not what they are. They were delivered by the mouth of the Almighty King of the universe to the ears of an entire nation at once. They came with sounds and sights that have never been experienced since. They were spoken audibly by the mouth of the Master of all worlds. We could see those words, as if sparks. HaShem Himself carved them onto tablets (twice). Our tradition tells us that those tablets were miraculously carved in a way to be visible on both sides, with the words suspended as if on air.

Beloved, they are words of life. They are Ten Words. They are the summary of HaShem's self-revelation. Think about that for a moment. Everything that He said, is found within these Ten Words. And the first of them is...

I am the HaShem your G-d, Who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.

Exodus 20:2

This is His formal introduction to His bride. Never forget that.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

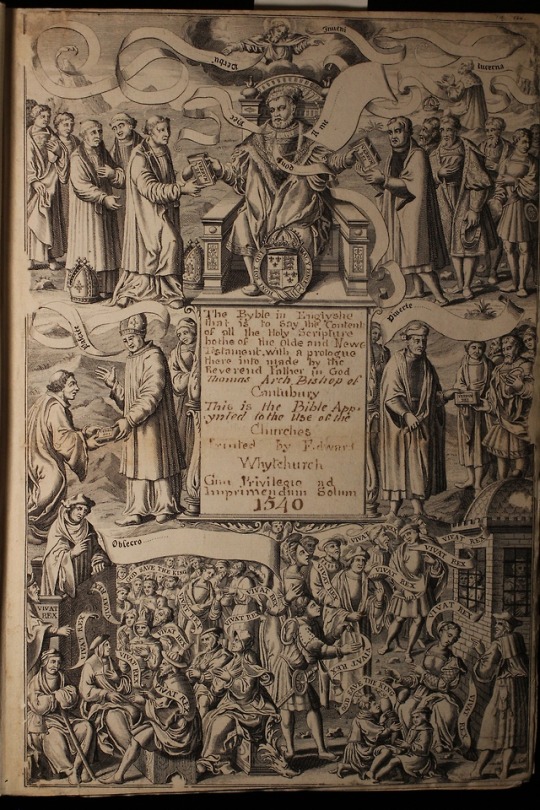

[Bible] The Byble in Englyshe, tr Myles Coverdale. London : Edward Whitchurch, 1540.

Original collection

On the left is a Great Bible, the first English Bible to be authorized by the monarchy. This Bible, prepared by Myles Coverdale, was commissioned by Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell. The cover was created by Hans Holbein and shows the King handing the “verbum dei” or “word of God” to the Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, while the peasants below are saying “vivat rex” or “long live the king!”

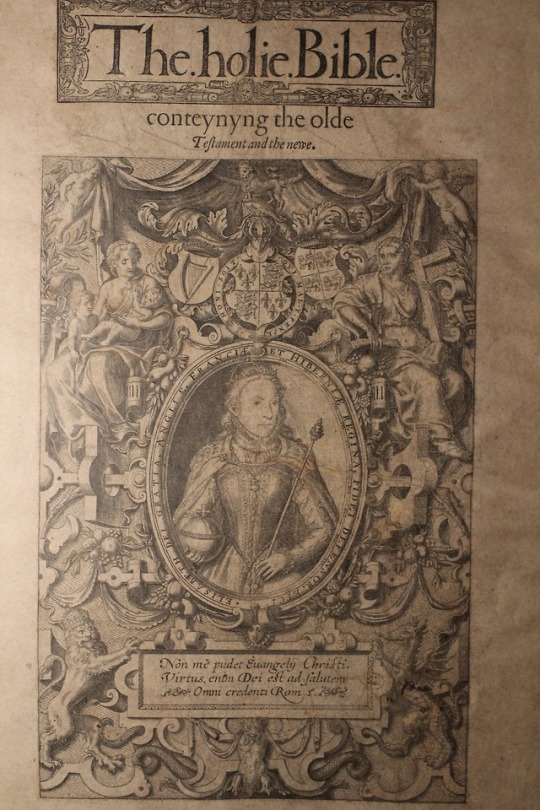

[Bible] Holie Bible, the Bishops’ Bible. London : Richard Jugge, 1568.

Original collection

On the right is Elizabeth I’s Bishops’ Bible. This authorized Bible was meant for worship in the Church of England, and thus was known as the Bible for the Bishops. It would be known as the Treacle Bible because the translation of Jer. 8:22 reads, “is there no treacle in Galaad.” Unlike the Geneva Bible, this Bible was an attempt to appease the Church and not the growing Puritan population.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is the King James Bible so popular?

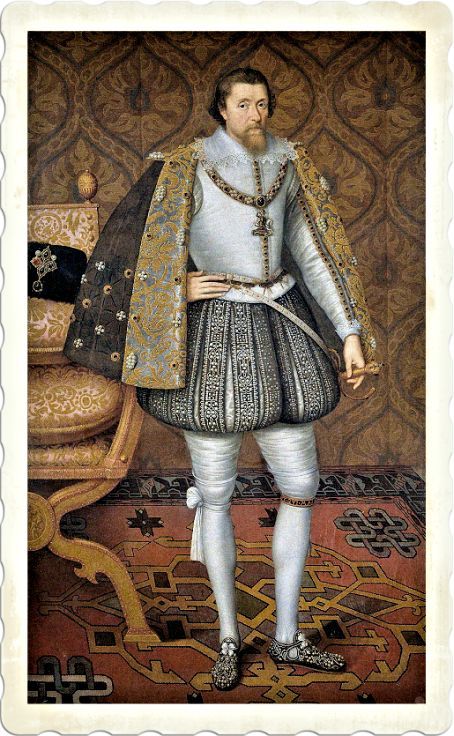

Shortly after he ascended the English throne in 1603, King James I commissioned a new Holy Bible translation that, more than 400 years later, is still widely read around the world.

This Bible, known as the King James Version (KJV), helped King James leave behind a lasting cultural footprint — one of his goals as a leader. “James saw himself as a great Renaissance figure who wanted to impart on the world culture, music, literature and even new ways of learning,” Bruce Gordon, a professor of ecclesiastical history at Yale Divinity School, told Live Science.

But given the KJV’s age, why is it still so popular across different Christian denominations?

Related: Why does Christianity have so many denominations?

In short, the KJV’s influence has waxed over the centuries because, Gordon said, it was the version that was most widely read and distributed in countries where English was the dominant language and that its translation was “never really challenged until the 20th century.” In that time, the KJV became so embedded in the Anglo-American world that “many people in Africa and Asia were taught English from the KJV” when Christian missionaries brought it to them, Gordon said. “Many people weren’t even aware that it was one of many available translations,” he added, “they believed the King James Version was the Bible in English.”

But there’s more to the story that goes back to the translation’s inception.

Why did King James want a newly translated Bible?

Before James commissioned the KJV in 1604, most people in England were learning from two different Bibles — the Church of England’s translation, commonly read during worship services (known as the Bishops’ Bible, first published in 1568), and the more popular version most Brits read at home, known as the Geneva Bible, first published in 1560. The Geneva Bible was the Bible of choice among Protestants and Protestant sects, and as a Presbyterian, James also read that version. However, he disliked the lengthy and distracting annotations in the margins, some of which even questioned the power of a king, according to Gordon.

What’s more, when James assumed the English throne in March 1603, following the death of Queen Elizabeth I, he inherited a complicated political situation, as the Puritans and the Calvinists — religious followers of reformer John Calvin — were openly questioning the absolute power of the Church of England’s bishops. James’ own mother — Mary, Queen of Scots — had been executed 16 years earlier in part because she was perceived to be a Catholic threat to Queen Elizabeth’s Protestant reign. “Mary’s death made James keenly aware of how easily he could be removed if he upset the wrong people,” Gordon said.

A portrait of James VI and I, King of Scotland, England and Ireland (1566-1625). The portrait, painted by the Dutch painter Daniel Mytens (also spelled Daniël Mijtens) in 1621, is on display at the National Portrait Gallery in London. (Image credit: Photo by Robert Alexander/Getty Images)

To moderate such divisions, James commissioned a Bible that aimed to please both parishioners of the Church of England and the growing Protestant sects by removing the problematic and unpopular annotations of the Geneva Bible while remaining true to the style and translations from both Bibles that each group revered. Despite James’ efforts, Gordon said, “the KJV didn’t really succeed while James was alive.” That’s because the market for James’ version didn’t really arise until the 1640s, when Archbishop William Laud, who “hated the Puritans,” suppressed the Geneva Bible that the Puritans followed, Gordon said.

James died from a stroke in March 1625, so he never saw his Bible become widely accepted. But even during his lifetime, after James commissioned the translation, he didn’t oversee the process himself. “It’s almost as if he got the ball rolling, then washed his hands of the whole thing,” Gordon said.

Related: Was the ‘forbidden fruit’ in the Garden of Eden really an apple?

How the KJV was translated

To oversee the translation, James commissioned six committees made up of 47 scholars from the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. They were tasked with translating all of the Hebrew and Greek texts of the Old and New Testaments into English. It was a complicated and sometimes contentious process that took seven years to complete. Though we don’t have a lot of the records of those committees, “through our best reconstructions, we understand it was a very rigorous debate with everyone committed to the most accurate translation of the Bible,” Gordon said.

Much of the resulting translation drew on the work of William Tyndale, a Protestant reformer who had produced the first New Testament translation from Greek to English in 1525. “It’s believed that up to 80% of the King James Version stems from the William Tyndale version,” Gordon said.

A comparison between Tyndale’s Bible, 1528: I Corinthians, chapter 13, 1-3, (top) and the King James Version, 1611: I Corinthians, chapter 13, 1-3, (bottom). (Image credit: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Why is the KJV still popular today?

For a book that was published in 1611, it’s amazing how influential and widely read the KJV still is today. Though there are hundreds of versions and translations of the Bible, the KJV is the most popular. According to market research firm Statistica, as of 2017, more than 31% of Americans read the KJV, with the New International Version coming in second place, at 13%. Five large denominations of Christianity — Baptist, Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Latter-day Saints and Pentecostal — use the KJV today.

The KJV “works as both a word-for-word and sense-for-sense translation,” meaning it acts as both a literal translation of many of the words believed to have been used by Jesus Christ and his Apostles and accurately conveys the meaning behind those words and events, Gordon said. One line of manuscripts used in the KJV — the Textus Receptus of Erasmus, translated from Greek to Latin by the 16th-century Dutch scholar and philosopher Desiderius Erasmus — is thought by some to be a particularly important inclusion in the KJV, especially for those who see it as the purest line of the New Testament going back to the Apostolic Age (A.D. 33 to 100), Gordon said.

Despite the KJV’s popularity throughout the centuries, Gordon said some scholars now view parts of it as outdated. He cautioned that there have been other ancient manuscripts discovered since the KJV was commissioned that enhance scholars’ understanding of some biblical events and possibly even change the meaning of certain words.

Related: What led to the emergence of monotheism?

For example, in the mid-20th century, “many translators believed that ‘maiden’ or ‘young woman’ was a more accurate Hebraic translation to use to describe Jesus’ mother Mary, instead of ‘virgin,'” Gordon said. If correct, the interpretation would have far-reaching implications as the Old Testament prophet Isaiah had prophesied that the Messiah would be born of a virgin. “Translations,” Gordon said, “are not neutral things.”

To that end, many KJV readers (known as “King James Onlyists”) don’t believe the Bible should be updated at all and hold to the notion that James’ version was translated from the most reliable manuscripts. What’s more, Gordon said, some Onlyists believe that the scholars who oversaw the KJV translation were “divinely inspired” and that more modern translations should be disregarded because they have been “carried out by nonbelievers.”

Even casual religious observers or nonbelievers are affected by the prose of the KJV Bible in ways they may not realize. Its poetic language has influenced generations of artists and activists, with many biblical phrases becoming part of our everyday language. A few examples include “the blind leading the blind,” “the powers that be,” “my brother’s keeper,” “by the skin of your teeth,” “a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” “rise and shine” and “go the extra mile,” according to Wide Open Country. Even the famous opening line “Four score and seven years ago” from President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address was inspired by language used in the KJV.

Originally published on Live Science.

New post published on: https://livescience.tech/2021/05/17/why-is-the-king-james-bible-so-popular/

0 notes