#Birgitte Christensen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#movies#polls#ordet#ordet 1955#ordet movie#50s movies#carl theodor dreyer#henrik malberg#birgitte federspiel#emil hass christensen#preben lerdorff rye#cay kristiansen#have you seen this movie poll

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Everyone at Borgen is anxious about Laugesen’s revealing book.”

#borgen#borgenedit#borgen season 1#birgitte nyborg#philip christensen#say whatever you want about philip but their chemistry was amazing

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Jeppe på Berget" (1984) - Magne Bleness

Films I've watched in 2023 (50/119)

Such a good adaption of this play. Johannes Joner's nuanced portrayal of the Baron is the perfect mixture of vapid fop and powerful aristocrat you do not want to cross.

#films watched in 2023#Jeppe på Berget#Per Christensen#Kirsten Hofseth#Jan Ø. Wiig#Johannes Joner#Arne Bang-Hansen#Per Frisch#Per Gørvell#Birgitte Victoria Svendsen#Magne Bleness#Ludvig Holberg#motionpicturelover's screencaps#FT

0 notes

Photo

Preben Lerdorff Rye in Ordet (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955)

Cast: Henrik Malberg, Emil Hass Christensen, Birgitte Federspiel, Preben Lerdorff Rye, Cay Kristiansen, Ejner Federspiel, Gerda Nielsen, Sylvia Eckhausen, Ove Rud, Henry Skjaer. Screenplay: Carl Theodor Dreyer, based on a play by Kaj Munk Cinematography: Henning Bendtsen. Production design: Erik Aaes. Film editing: Edit Schlüssel. Music: Poul Schierbeck.

As a non-believer, I find the story told by Ordet objectively preposterous, but it raises all the right questions about the nature of religious belief. Ordet, the kind of film you find yourself thinking about long after it's over, is about the varieties of religious faith, from the lack of it, embodied by Mikkel Borgen (Emil Hass Christensen), to the mad belief of Mikkel's brother Johannes (Preben Lerdorff Rye) that he is in fact Jesus Christ. Although Mikkel is a non-believer, his pregnant wife, Inger (Birgitte Federspiel), maintains a simple belief in the goodness of God and humankind. The head of the Borgen family, Morten (Henrik Malberg), regularly attends church, but it's a relatively liberal modern congregation, headed by a pastor (Ove Rud) who denies the possibility of miracles in a world in which God has established physical laws, although he doesn't have a ready answer when he's asked about the miracles in the Bible. When Morten's youngest son, Anders (Cay Kristiansen), falls in love with a young woman (Gerda Nielsen), her father, Peter (Ejner Federspiel), who belongs to a very conservative sect, forbids her to marry Anders. Then everyone's faith or lack of it is put to test when Inger goes into labor. The doctor (Henry Skjaer) thinks he has saved her life by aborting the fetus, but Inger dies. As she is lying in her coffin, Peter arrives to tell Morten that her death has made him realize his lack of charity and that Anders can marry his daughter. Then Inger is restored to life with the help of Johannes and the simple faith of her young daughter. Embracing Inger, Mikkel now proclaims that he is a believer. The conundrum of faith and evidence runs through the film. For example, if the only thing that can restore one's faith is a miracle, can we really call that faith? What makes Ordet work -- in fact, what makes it a great film -- is that it poses such questions without attempting answers. It subverts all our expectations about what a serious-minded film about religion -- not the phony piety of Hollywood biblical epics -- should be. Dreyer and cinematographer Henning Bendtsen keep everything deceptively simple: Although the film takes place in only a few sparely decorated settings, the reliance on very long single takes and a slowly traveling camera has a documentary-like effect that engages a kind of conviction on the part of the audience that makes the shock of Inger's resurrection more unsettling. We don't usually expect to find our expectations about the way things are -- or the way movies should treat them -- so rudely and so provocatively exploded.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Through the Years → Queen Mary of Denmark (870/∞) 2 June 2024 | The Queen participated in Hjernesagen's 30th anniversary and presentation of Hjernesagen's Research Grant and Honorary Award. On arrival at DGI Huset in Vejle, the Queen was received by Hjernesagen's director Birgitte Hysse Forchhammer, national chairman Jens Bilberg and mayor of Vejle Municipality Jens Ejner Christensen. (Photo by Alex Tran/Kongehuset)

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Photo

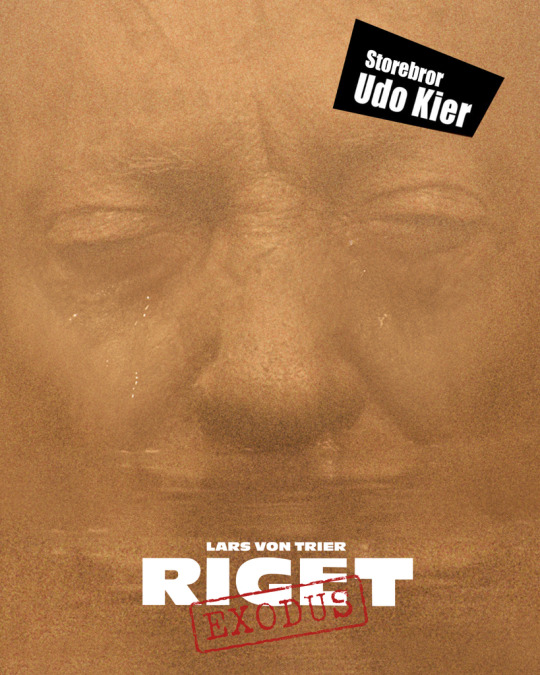

RIGET: EXODUS (2022) dir. Lars von Trier

#sdfghjklæøkjhgfhdhjklæjhgfdhjk#riget#the kingdom#tvedit#alexander skarsgård#lars mikkelsen#udo kier#tuva novotny#mikael persbrandt#laura christensen#nikolaj lie kaas#søren pilmark#birgitte raaberg#bodil jørgensen#riget exodus#2020#**

121 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#birgitte nyborg#magnus christensen#borgen#sidse babett knudsen#lucas lynggaard tønnesen#borgen spoilers

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me in 2012: Poor Magnus is falling through the cracks.

Me in 2022: Poor Magnus has fallen through the cracks.

#borgen#birgitte nyborg#magnus christensen#i basically spend the whole show swallowing vowels and prtending i speak danish#skål#tusen takk#vi ses

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ordet (1955, Denmark)

By the 1950s, Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer had made eleven films. However, his last three works were victims of circumstance. The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) consistently ranks high in film critics’ lists of the greatest movies ever made, but it offended ardent French nationalists who resisted the idea of a Dane directing a movie about one of the nation’s secondary patron saints. Vampyr (1932), in its stillness and languor befitting its disturbing atmosphere, was despised by audiences – including a riot from Viennese moviegoers demanding a refund – expecting more action. Day of Wrath (1943) released a firestorm of controversy in Nazi-occupied Denmark because of its allegory about living under an authoritarian regime. All three of these films were commercial failures. All three of these films are today considered cinematic exemplars.

Danish movie producers might have sneezed, claiming imaginary allergies, at the notion of financing the next Dreyer film, but the Danish government decided to reward Dreyer – struggling with finances after World War II – with a lifelong lease to the Dagmar, the state arthouse movie theater. With a morsel of the Dagmar’s profits, Dreyer sought a project he could make on a shoestring budget. Dreyer’s twelfth film would be Ordet (“The Word” in English), based on a play of the same name by Lutheran pastor Kaj Munk. Ordet is a severe film that never loses hold of an attentive viewer. It contains a provocative ending that cannot (and will not) be spoiled, and it is an ideal follow-up to The Passion of Joan of Arc and Day of Wrath in that this piece examines the nature of faith. Instead of probing why the film’s characters believe (or don’t believe) in God, its focus is instead on how the characters express their belief.

In the autumn of 1925, widowed Borgen family patriarch Morten (Henrik Malberg) is a devout farmer soon to be busy with doting on his third, incoming grandchild. Morten has three sons: his eldest, Mikkel (Emil Hass Christensen), is agnostic, married to Inger (Birgitte Federspeil), and the couple have taken care of Morten’s two grandchildren; middle son Johannes (Preben Lerdorff Rye) went mad studying Søren Kierkegaard’s texts and now believes himself to be Jesus Christ; and youngest son Anders (Cay Kristiansen), the center of the film’s attention for a plurality of its runtime, is lovesick. The entire Borgen family lives under the same roof – creating tension, but Morten is nevertheless proud of “Borgensfarm”.

Anders and Anne Petersen (Gera Nielsen) wish to marry. Anne’s father Peter (Ejner Federspiel), is the local leader of the conservative Inner Mission sect of Lutheranism; Anders and Anne correctly believe he will oppose the marriage. Peter’s standoffish rejection inspires Morten – also originally in opposition – to change his mind. He stomps over to Peter’s residence, arriving mid-sermon, and failing to sway his friend. Peter’s telephone rings as they argue, and Peter must bear news of a family emergency at Borgensfarm.

Pacing and an intricate plot are of no concern to Dreyer. For the film’s opening two-thirds, Dreyer – who wrote the adapted screenplay – takes all the time needed to let the audience know the lives of the Borgens. The love shared between all three generations of the Borgen family is never questioned, although their understanding of and relationship with God differs. Because of my lack of religious belief, I do not know how to accurately describe Dreyer’s comparison of Morten and Peter other than the former is less beholden to religious dogma than the latter. The agnostic Mikkel believes God as essentially dead, forsaking long ago the children of Earth to the kindness and cruelty of their neighbors. No one in the Borgen household condemns or lampoons Mikkel for not believing. Certainly not Inger, who sympathizes with this struggle of faith. Not even Johannes, the most difficult son to truly understand. Johannes, speaking Jesus’ words from scripture and words that one could imagine Jesus might have said in rural 1920s Denmark, appears as a cloud-gazing, simply-clothed itinerant by day. His words are lofty, his speech deliberate, his empty gaze distancing him from those who surround him. He asks others to pray and believe, never wrathful if they do not listen or heed his advice. By night, he returns home as he always has done. Though he no longer addresses his father, brothers, sister-in-law, and nieces as his father, brothers, sister-in-law, and nieces, they still treat him as family – even though they do not accept him as Christ. For Anders, he is obviously preoccupied with the woman he loves.

Ordet is structured around the domestic lives and habits of its characters – it is akin to free verse poetry, resisting any attempts at novelistic analysis. Characters fully express themselves, and dialogue never overlaps between speakers (even in argument). There is silence after completed statements of opinion and revelation. In that silence, Dreyer’s camera captures the listener’s reaction (except for Johannes, who does not visually react): contentment, disbelief, amusement, concern, horror, understanding. This is executed in the mostly empty spaces of the Borgen household, against clear backdrops. In the dialogue pauses during and between conversations, all one can hear is ambient noise: the floorboards creaking as a character is making their way across the room, the clock ticking in the parlor room, someone shuffling positions in their chair. Cinematographer Henning Bendtsen (1959’s Boy of Two Worlds, 1991’s Europa) keeps his camera distant – of Ordet’s 114 total shots (averaging more than sixty seconds each between cuts), only three are close-ups. It is as if there is a presence accompanying the characters even in the most ordinary scenes, but that presence is something unknowable, something beyond an individual’s understanding of God.

Bendtsen’s mastery of mise en scène (a concept that is generally defined as the combination of set design, shot composition, and actor placement to empower cinematic or theatrical art) culminates when Mikkel’s oldest daughter, Maren (Ann Elisabeth Groth), walks into the parlor room to see her uncle Johannes waiting in the dark. Inger has gone into labor; her pregnancy endangering her life. Maren has overheard how perilous her mother’s situation is from the adults and cannot sleep.

youtube

She asks Johannes if her mother will die soon; he responds, “Do you want her to, little girl?” The camera cuts. “Yes, because then you’ll bring her back to life, won’t you?” It is a curious response that raises unanswered questions how Mikkel’s two girls view Johannes as an uncle and as a self-proclaimed Christ. The others will not allow me to perform this miracle, notes Johannes, as the camera begins to slowly revolve around them. Maren and Johannes have a late-night conversation about what happens when a mother goes to heaven and miracles. The gradual dolly shot going across Johannes and Maren’s front sides display the empty depths of the parlor room, suggesting something there. Again, it suggests something beyond our conception of God. Maren and Johannes’ conversation adds to this, as Johannes comforts Maren, imparting that mothers will be with their children even in death, without the stress of other things during the day. In three minutes, a creaking floorboard, ticking clock, Johannes’ blank face, and the familial tenderness between the two actors have encapsulated what Ordet conveys to open-minded viewers of all faiths.

All of this is demanding, in different ways, for the acting ensemble and the audience. In many films (especially today’s cinema), editors will cut quickly from reactions to dialogue or during dialogue – serving to either undermine an actor’s ability or conceal their shortcomings. Because of the camerawork and minimal editing, there is little room for any mediocre acting to hide in Ordet (which contains stellar performances from its ensemble), a production that asks its actors to inhabit their characters for lengthy stretches without a cut. In a way, this harkens to Ordet’s background as a stage play, but the film adaptation does not feel stage-bound. For the audience, the barely moving camera and thoughtful pace can be an impediment to the impatient. But I suspect many viewers – as I did – will have difficulty unpackaging Johannes. Johannes, with all credit to Preben Lerdorff Rye, seems like he accidentally walked onto the wrong movie set and began acting thinking he was shooting for that other production. That last sentence could be construed as disparagement, but it is not – Rye’s performance befits the character, and Dreyer’s intention to perplex viewers with Johannes’ presence is controlled and purposeful.

Johannes’ presence in Ordet strikes at unsettling ideas for Christians and non-Christians alike, and these conflicting ideas are integral to the film’s controversial final ten minutes. In contrast to Morten’s comfortable, undemanding religiosity and the Inner Mission’s stringent emphasis on dogma, Johannes’ claims to be Christ is unnerving. The New Testament is filled with parables, gospels, and miracles told and performed by Christ. The Borgen family and the Inner Mission sect adherents would rather Jesus be dead, with God’s physical embodiment and judgment removed from the corporeal world humans share, than believe Johannes to be the son of God. Every character in Ordet except Johannes believes that the days of God’s miracles have passed; to some viewers, the film may seem to endorse this view. But Dreyer’s intentions are not to evangelize on behalf of any Christian belief – Dreyer, according to film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, was not religious and his occasional visits to a French Reformed church were attempts to familiarize himself with Christian colloquialisms for his film projects. Dreyer wants to understand how religion plays a role in the lives of the Borgens and the film’s secondary characters and how they express their faith. He succeeds.

By the time Ordet’s final act begins, the viewer is probably still wondering how such an apparently simple film that may have bored them in the opening half-hour has convinced them to finish it – barreling into the thickets of one’s soul with unexpected force. Dreyer and the actors have outlined their characters completely, allowing observant viewers intuit each character’s reactions to the mundane and the sublime. The film’s paradoxical and transcendent conclusion provides these characters and the audience an ending that we desperately desire, but also challenges that desire to question our faith.

For the first time since the silent era, Carl Theodor Dreyer had made a film that was instantly acclaimed by critics and audiences in Denmark and abroad – including receiving the Golden Lion at the 1955 Venice Film Festival and a joint Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Film shared with four other movies. Despite Ordet’s success, Dreyer would continue to struggle in finding funds to make another film. Dreyer made only one more film in Gertrud (1964), and a long-gestating project about Jesus (no surprise that Dreyer would consider making such a film) never came to fruition, although a manuscript outlining the film was published in 1968.

As someone who was never raised with much of an understanding of the Abrahamic religions, I nevertheless find films commenting about the nature of religious belief fascinating. Almost all these films, due to demographics and religious history, have been within Christianity’s folds. Too often faith is held as a nightstick for comic or dramatic purposes in narrative art – and this sort of art is neither challenging nor rewarding for anyone. In recent years, I have found glorious exceptions from Old Hollywood and in non-English-language cinema that put to shame the evangelical-specific, exclusionary present of the American Christian film industry. Ordet is arguably one of the most exacting and illuminating religious films ever made. Late in Ordet, Dreyer’s film finds itself in a wallow of despair and ends with spirits exultant. Its ending – one that I desired – still leaves me uplifted and horrified.

My rating: 10/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#Ordet#Carl Theodor Dreyer#Henrik Malberg#Emil Hass Christensen#Birgitte Federspiel#Preben Lerdorff Rye#Cay Kristiansen#Ejner Federspiel#Gerda Nielsen#Henning Bendtsen#Kaj Munk#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

4 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

Birgitte: Phillip, we tried things your way.

Phillip: No, we didn't.

Birgitte: I did it in my head and it didn't work.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ORDET (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955)

#ordet#la palabra#carl theodor dreyer#henrik malberg#preben lerdorff rye#emil hass christensen#cay kristiansen#birgitte federspiel#film#cine

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Women of Borgen

Elna Munch, Helga Larsen, Karen Ankersted, Mathilde Malling Hauschultz. I hope we all know these names. These are four women who were the first of their gender to gain a seat in Parliament in 1918, and thus ended the Parliament debate about whether women are cut out to be politicians. To all those who wish to debate whether women should enter politics on equal terms with men and ultimately make Prime Minister, I can only say: You’re 100 years behind. So many insignificant topics have been discussed. Did any of you really believe I intended to resign and become a housewife? You must not know me at all then. I very much want to end all these foolish discussions. Today, the last part of the government reform package was passed. We’ve shown you where we want to take Denmark. I’m very pleased and proud of that. That’s why I’m going to let the Danish voters decide. Not what gender the Prime Minster should be, but whom they feel is the best Prime Minister for Denmark.

#borgen#borgenedit#sidse babett knudsen#birgitte hjort sørensen#birgitte nyborg#katrine fønsmark#hanne holm#laura christensen#pia munk#and a bunch of other ladies#gif#mine#sbk*#borgen*#it's honestly amazing that there are even more women in this series#with multi-episode arcs that could have been included#Borgen is the show we all deserve

262 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝔽𝕒𝕞𝕚𝕝𝕚𝕖𝕟 𝕒𝕗 𝔸𝕟𝕥𝕙𝕠𝕟𝕪 𝕀𝕧𝕒𝕟 ℍ𝕠𝕝𝕤𝕥

Søren Engelbrecht Holst (Deceased father - Jesper Christensen) Birgitte Lise Michelsdatter (Deceased mother - Ingrid Bergman)

Mathilde Abrielle Holst née Pelletier (Ex-wife - Marion Cotillaird) Sofia Veronique Holst (Daughter - Virginia Gardner)

Growing up as a child, Anthony’s life was never steady. Due to the way his father chased where less than legal work laid, he never had a real home, never settled. Bouncing from country to country Birgitte tried her best to have a semblance of a family through it all but Søren was busy teaching his son how to be a man and forget about being a boy.

Anthony feared his father, he had a ruthless personality at work and it continued long after he did multiple jobs and favours for dangerous men. As he grew older, he learned to revere and respect him as he watched him climb the rungs up the proverbial ladder.

Though his mother was his protector when Søren’s words and actions grew too much, she could not shield him from his reality, from what footsteps had been paved for him to follow. His father sidled his way to becoming the right hand for a French gangster and eventually took over his crime ring. Birgitte tried her very best with Anthony, and it is because of her he has a semblance of humanity about him.

It was his mother who convinced him he should marry. Whilst Anthony had a few love inconsequential affairs in his day, Birgitte set him up with the daughter of a fairly well-to-do restaurateur. He was soon to wed Mathilde at his mother’s request and he learned to love the woman as a good husband should. All the while he wheedled his way into Mathilde’s family business, soon earning his father-in-law’s trust for his name to be on the lease as well as it going to him when he died.

Though his heart perhaps did not belong to Mathilde entirely, he had a fondness for her, especially when she bore his child. Now Anthony Ivan Holst had never been one for showing emotions but when Sofia was born and he heard the screaming of the new baby, his baby - he was a changed man. Holding her in his arms for the first time, tears fell down his face and he gave her a silent promise to never let harm come to her.

Though he loved his daughter more than life itself he never wanted to become his father to her. Fearing himself becoming a self fulfilled prophecy, when she was old enough he sent her off to boarding schools throughout her life. When Sofia became a teenager, he and Mathilde split up, the latter half of their marriage only really being held together by their daughter.

He is still fiercely protective of Mathilde, remaining fairly amicable as they both gave into the fact their relationship was nothing but manufactured to fit a mould. It was the turn of the century and they both deserved better than that.

When his father died the business became his. His father’s last words were for him to continue his legacy. Anthony was simply surprised he was not murdered before death caught up to him. The Holst legacy was his it was everything he wanted. Or, everything his father wanted him to want.

His mother’s death was quite a different affair. She eventually developed dementia, forcing Anthony to send her to a nursing home and relent the responsibility to someone else in her later life. He was not there when she slipped away into the darkness - he would never know Birgitte asked for him in her last moments at the mercy of the nurses there.

Sofia once used to idolise her father when she was a child, she still recalls being thrown above his head and feeling like she was flying. Everytime her parents sent her away to England, she felt her heart break a little bit more. Her heart is shattered when all Anthony ever wanted was to keep it safe.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

PERIOD. from Bacon CPH on Vimeo.

Dir: Emilie Thalund Production: Bacon CPH Producer: Birgitte Rask Production Manager: Laura Valentiner-Bohse DOP: Sine Brooker B-foto: Steadicam: Kim Jensen Set Designer: Eva Kristine Lendorph Christensen Editor: Anders Jon Colourgrade: Hannibal Lang Sound Design: Sound Composer:

Big thanks

1 note

·

View note