#Cay Kristiansen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

'Ordet' – Carl Dreyer searches for grace on Criterion Collection

One of the most powerful and profound films about faith ever made, Carl Dreyer’s Ordet (Denmark, 1955) (which translates to “The Word”) turns a Romeo and Juliet story into a passionately spiritual drama of love and acceptance. Anders (Cay Kristiansen) and Anne (Gerda Nielsen) are young lovers in rural farming community, he the son of proud farmer Morten (Henrik Malberg), she the only daughter of…

#1955#Carl Dreyer#Cay Kristiansen#Criterion Channel#Denmark#DVD#Ejner Federspiel#Gerda Nielsen#Henrik Malberg#Ordet#Preben Lerdorff Rye

0 notes

Text

Carl Theodore Dreyer

I like to say I’ve seen CTD’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” but actually, it was playing on a screen at a Catpower concert about 100 years ago. Catpower was all the rage back then. She was allowed to be grumpy on stage. And, people ate it up. So, this is the first CTD film I’ve ever actually seen.

Camera movement. Pans, tracking, 360s — both around the subject (the uncle and the young girl whose mother is about to die in childbirth) and spinning in the middle of the subject (a room for example). That one of the uncle and the child is sweet and captivating. She is like the Christ child and Mary in a Renaissance painting. She’s the only one who takes the crazy uncle, Johannes, seriously, and as it turns out, she’s not far off.

This film is about communities and identity, in this case formed by religion. There are two rival religious factions, old and new. Each thinks marrying into the other would be unacceptable. To us now, these differences in belief systems seem insignificant. They weren’t small differences to the characters in the story. They take this stuff very seriously.

Yet, when in the presence of the potential for a real miracle, nobody takes it seriously. (Spoiler follows.) Ok, so it’s easy to say now, after we find out the crazy uncle apparently can bring someone back from the dead. It’s hard to believe in a real miracle. It’s easier to believe in a fantasy, or a conspiracy theory, or just plain lies.

The film has a classical structure. Setup of the Borgen family: father, and brothers, and wife, and kids at the farm with Johannes. The inciting event is when the youngest son wants to marry a girl from their rival religious sect. The son’s father, Morten, is against the union until he finds out that the girl’s father refuses because the Borgen’s religion isn’t up to snuff. The child birth tragedy comes exactly at the midpoint. Inger, wife of the eldest son, Mikkel, seems to be recovering, but Johannes predicts her death unless his father believes in him. A nice midpoint surprise. Nothing like actual death to elevate religious conflict.

It all comes down to this:

And, what about Kierkegaard? Study him and go crazy, apparently. That’s the explanation given for Johannes’s delusional state of mind. But, Johannes seems to control two life and death scenarios. Maybe he is Jesus Christ after all. If Jesus lived in our time, he’d be locked up, or at least shooed away from hanging out by the subway entrance.

Even before Catpower, I took a class with a young philosophy professor, who told us that “Soren” was slang for “dick” in Denmark. The class was on Nietsche, and I think the girls loved him. Lots of wavy hair. I guess philosophy worked out for him. But, I can’t find any reference to “Soren” as a swear word on the interweb. People will believe just about anything for a song and dance.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

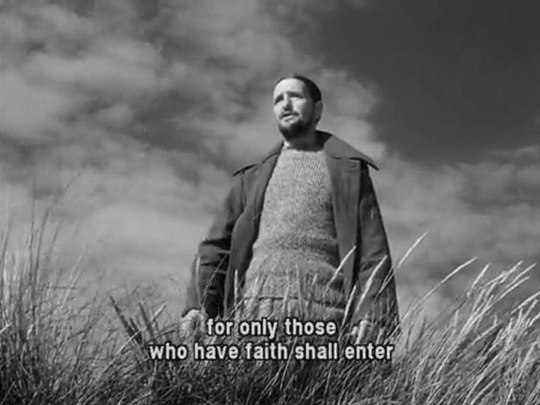

Preben Lerdorff Rye in Ordet (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955)

Cast: Henrik Malberg, Emil Hass Christensen, Birgitte Federspiel, Preben Lerdorff Rye, Cay Kristiansen, Ejner Federspiel, Gerda Nielsen, Sylvia Eckhausen, Ove Rud, Henry Skjaer. Screenplay: Carl Theodor Dreyer, based on a play by Kaj Munk Cinematography: Henning Bendtsen. Production design: Erik Aaes. Film editing: Edit Schlüssel. Music: Poul Schierbeck.

As a non-believer, I find the story told by Ordet objectively preposterous, but it raises all the right questions about the nature of religious belief. Ordet, the kind of film you find yourself thinking about long after it's over, is about the varieties of religious faith, from the lack of it, embodied by Mikkel Borgen (Emil Hass Christensen), to the mad belief of Mikkel's brother Johannes (Preben Lerdorff Rye) that he is in fact Jesus Christ. Although Mikkel is a non-believer, his pregnant wife, Inger (Birgitte Federspiel), maintains a simple belief in the goodness of God and humankind. The head of the Borgen family, Morten (Henrik Malberg), regularly attends church, but it's a relatively liberal modern congregation, headed by a pastor (Ove Rud) who denies the possibility of miracles in a world in which God has established physical laws, although he doesn't have a ready answer when he's asked about the miracles in the Bible. When Morten's youngest son, Anders (Cay Kristiansen), falls in love with a young woman (Gerda Nielsen), her father, Peter (Ejner Federspiel), who belongs to a very conservative sect, forbids her to marry Anders. Then everyone's faith or lack of it is put to test when Inger goes into labor. The doctor (Henry Skjaer) thinks he has saved her life by aborting the fetus, but Inger dies. As she is lying in her coffin, Peter arrives to tell Morten that her death has made him realize his lack of charity and that Anders can marry his daughter. Then Inger is restored to life with the help of Johannes and the simple faith of her young daughter. Embracing Inger, Mikkel now proclaims that he is a believer. The conundrum of faith and evidence runs through the film. For example, if the only thing that can restore one's faith is a miracle, can we really call that faith? What makes Ordet work -- in fact, what makes it a great film -- is that it poses such questions without attempting answers. It subverts all our expectations about what a serious-minded film about religion -- not the phony piety of Hollywood biblical epics -- should be. Dreyer and cinematographer Henning Bendtsen keep everything deceptively simple: Although the film takes place in only a few sparely decorated settings, the reliance on very long single takes and a slowly traveling camera has a documentary-like effect that engages a kind of conviction on the part of the audience that makes the shock of Inger's resurrection more unsettling. We don't usually expect to find our expectations about the way things are -- or the way movies should treat them -- so rudely and so provocatively exploded.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ordet (1955) · Carl Theodor Dreyer

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Word (1955)

Danimarkalı büyük usta Carl Theodor Dreyer’in 1955 yapımı filmi ‘The Word’, çiftlikte yaşayan bir aileyi merkez alarak aşk, ölüm ve din üzerinden inanç kavramını sorgulamaktadır. Çiftlik sahibi yaşlı Morten’in küçük oğlu Anders, dini konularda çatışma yaşadıkları ailenin kızı Anne ile evlenmek istemektedir. Büyük oğlu Mikkel’in karısı Inger üçüncü çocuğuna hamiledir, ortanca oğlu Johannes ise İsa…

View On WordPress

#birgitte federspiel#carl theodor dreyer#cay kristiansen#drama#gözyaşı Şişesi#henrik malberg#preben lerdorff rye#ustalara saygı

0 notes

Photo

Ordet | Carl Theodor Dreyer | 1955

Cay Kristiansen, Sylvia Eckhausen, Gerda Nielsen

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

New The Girls Are Willing Movie

The Girls Are Willing movie download

Actors:

Axel Bang Else-Marie Mogens Viggo Petersen Cay Kristiansen Henny Lindorff Buckhøj Anna Henriques-Nielsen Vilhelm Henriques Verner Tholsgaard Ole Larsen Valsø Holm

Download The Girls Are Willing

THE MISHEARD: Where the grass is weed and the girls are willing. Girls from New Orleans, Metairie and the West Bank are set to represent the United States at the One Nation. VOTE NOW: Misheard is:. Troop 4738 Information In the new Girl Scout Leadership Experience, the focus of Girl Scout activities are to. in Germany. Beastie Boys - College Girls Are Easy Lyrics College Girls Are Easy Lyrics - Anywhere I go a fly girl will please me, east to west. The reunion will definitely happen.. . Girls Will Be Girls: Girl Stalk, Part I from GWBGonline Girls Will Be Girls: Girl Stalk, Part I. Guns N' Roses: Where the grass is weed and the girls are willing Misheard (wrong) Guns N' Roses Lyrics from Paradise City. Lori Dokken's Web Home "the TURBO girls" Concert at Unity Christ Church - On August 9th "the TURBO girls" will. Fuller said: "All of the girls are up for it. Food & drinks will be served first, so that the girls are not. Girls Will Be Girls Online Internet shorts featuring characters from the cult film "Girls Will Be Girls. Varla finally joins housemates Evie and Coco for her first internet short based on the cult film "Girls Will Be Girls.

#The Girls Are Willing#Axel Bang#Else-Marie#Mogens Viggo Petersen#Cay Kristiansen#Henny Lindorff Buckh&xF8;j#Anna Henriques-Nielsen#Vilhelm Henriques#Verner Tholsgaard#Ole Larsen#Vals&xF8; Holm

0 notes