#Bessie Coleman

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#bessie coleman#black literature#black history#black tumblr#black community#african american#america history#civil rights#black history is american history#black excellence#black girl magic#blackexcellence365#equal rights#equality#eq

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today In History

Born January 26, 1892, Elizabeth “Bessie” Coleman became the first woman of African American and Native American descent to earn an aviation pilot’s license, as well as the first person of African American and Native American descent to earn an international aviation license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

Aviation professionals and aficionados continue to be inspired by Bessie’s daring and determination.

“The air is the only place free from prejudices. I knew we had no aviators, neither men nor women, and I knew the Race needed to be represented along this most important line, so I thought it my duty to risk my life to learn aviation.”

CARTER™️ Magazine

#carter magazine#carter#historyandhiphop365#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#cartermagazine#today in history#staywoke#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth#history#bessie Coleman

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

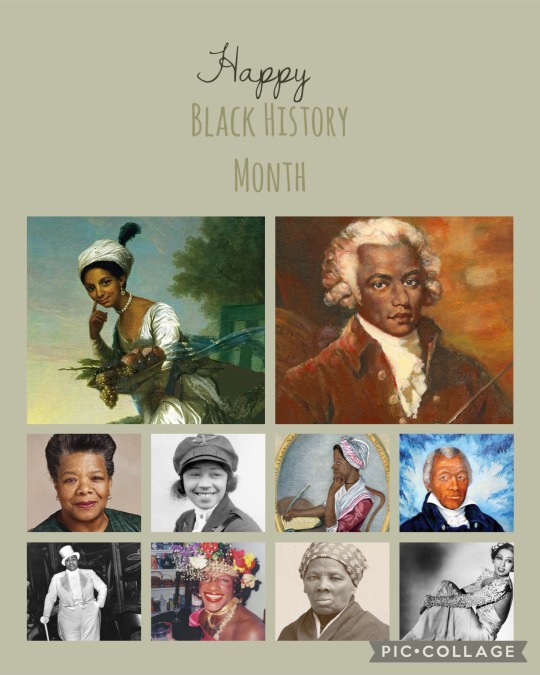

Black Historical Figures I think are cool af!

Happy Black History Month! Below the cut you’ll find a list of 10 black historical figures I think are super cool (and often overlooked in favour of their white/non-black counterparts) all of the figures are inspirational to me in some way and I think anyone can learn from their examples, regardless of race.

Dido Elizabeth Belle aka Dido Belle Lindsay - staying the course of your beliefs, knowing you deserve better. Knowing what’s right is more than possible.

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-George(s) - don’t let anyone take your talents and passions from you. Those who treat you wrong don’t deserve you.

Phillis Weatly/Phyllis Weatly - no matter what you’ve been subjected to, don’t let anyone take your voice from you.

James Armistead Lafayette - fight (spy) for what you believe in. You may turn out to be the most powerful piece in the fight.

Harriet Tubman - no matter the evils of the world, there are good people out there, don’t forget your strengths and allies.

Freda Josephine Baker (née McDonald) best known simply as Josephine Baker - dance and keep dancing, no matter how bad things are. You only live once.

Bessie Coleman - pursue your dreams no matter who tells you that you can’t. You may match them in renown yet.

Gladys Bentley - wear what you want, speak how you want, and love whomever you choose.

Marsha P. Johnson - be here, be queer, and speak truth to power.

Maya Angelou born Marguerite Annie Johnson - write, write, write, oh… and don’t fear life.

#meerathehistorian#black history month#black history month 2024#black history#queer history#black lives matter#dido elizabeth belle#joseph bologne#chevalier St Georges#history#phillis wheatley#american revolution#James Armistead Lafayette#harriet tubman#josephine baker#bessie coleman#gladys bentley#maya angelou#marsha p johnson#queer#lgbtq+#bisexual#lesbian

67 notes

·

View notes

Note

im sorry if this comes off as ignorant, but who's the person in your ao3 pfp?

That's Bessie Coleman, the first black woman to earn a pilot's licence. You should look her up. She's fascinating

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is Bessie Coleman, an early American acrobatic aviator. She is the first Black pilot, the first Native American pilot, and one of the first female pilots.

Born on January 26, 1892 in Atlanta, Texas to a family of sharecroppers, Bessie Coleman grew up in poverty. Her father abandoned the family when she was nine, and her elder brothers soon left as well, leaving her mother with the four youngest of her thirteen children. While taking care of her younger sisters, Bessie completed all eight available years of primary education, excelling in math. She enrolled at the Colored Agricultural and Normal University in Langston, Oklahoma in 1910, but lack of funds forced her to leave after only one term.

Five years later, she left the South and moved to Chicago to join her brother, where she worked as a beautician and manicurist for several years. An avid reader, she learned about World War I pilots in the newspaper and became intrigued by the prospect of flying. Her brother taunted her that she would never be able to fly. As a black woman, she had no chance of acceptance at any American pilot school, so she moved to France in 1919 and enrolled at the Ecole d'Aviation des Freres Caudon at Le Crotoy. After returning briefly to the United States, she spent one more term in France practicing more advanced flying before finally settling back in her birth country. She did exhibition flying and gave lectures across the country from 1922 to 1926. While flying, she refused to perform unless the audiences were desegregated.

Upon saving her money and nearing her goal of opening a flight school for blacks in the United States, Bessie Coleman was tragically killed on April 30, 1926 during a rehearsal for an aerial show when the airplane she was in unexpectedly went into a dive and then a spin, subsequently throwing Coleman from the airplane at 2,000 feet. Upon examination of the aircraft, it was later discovered that a wrench used to maintain the engine had jammed the controls of the airplane. Bessie was 34 years old. It is unknown whether her murder was an accident or intentional sabotage.

Despite her tragic fate, Coleman’s legacy of flight endures and she is credited with inspiring generations of African-American aviators, male and female, including the Tuskegee Airmen and NASA astronauts.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

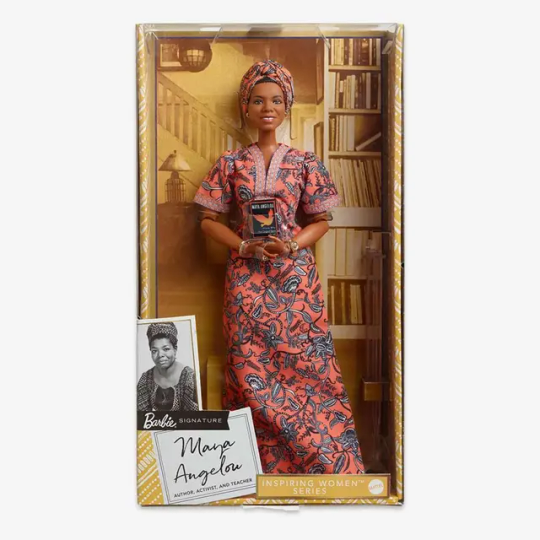

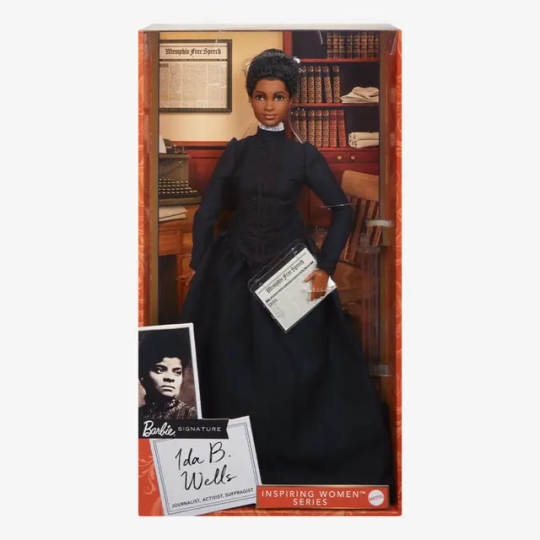

As February is Black History Month / African-American History Month (I'll be honest I don't know whether either of those terms are preferred - if someone could let me know, I would appreciate it), I thought I would make a post about how Mattel and the Barbie brand have intersected with this.

I have previously made some posts about this subject so just to collate some links:

A brief history of depictions of Black Barbies.

One of Mattel's first media tie-in dolls - Julia from the show Julia.

Alpha Kappa Alpha Barbie to commemorate America's first Black sorority.

Backstory on two of the dolls in the Barbie doll line depicted exclusively as Black women - Christie and Nikki.

The lore of Brooklyn and Malibu.

To expand on the above - I must shout out again Kitty Black Perkins by name even though I mentioned her in the history of Black Barbies post. Perkins is a now-retired Barbie designer credited with designing the first Barbie to be depicted as Black (that is to say, not a Francie or a Christie or another character - but Barbie), among other Barbies.

In addition to the first Black Barbie, Perkins is credited with design of four Holiday Barbies, as well as a number of other Barbies and friends of Barbie - apparently designing or having input into the design of hundreds of Barbies.

Without the influence of Perkins, it's very possible that we would not have modern doll releases featuring Brooklyn as a lead alongside Malibu.

Mattel have included a number of historical Black women in their Inspiring Women collection; this is not all of them by any means, but an example.

#barbie#black history month#black history#african american history#african american history month#kitty black perkins#brooklyn roberts#holiday barbie#inspiring women#sheroes#bessie coleman#ida b wells#maya angelou

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bessie Coleman by Allison Adams

Bessie Coleman (1892 – 1926) was an American civil aviator. She was the first female pilot of African American descent and the first woman of Native American descent to hold a pilot license. She was also the first person of African American and Native American descent to hold an international pilot license. Bessie would only perform if the crowds were desegregated and entered through the same gates.

#bessie coleman#Allison Adams#herstory#women’s history#women in history#black history#art#artwork#female portrait#female pilot#black women in history#irl women/girls

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Breaking Barriers: The Inspiring Journey of Bessie Coleman, America's First Black Female Aviator

#bessie coleman#black power#black excellence#black history#black tik tok#black pilot#black pilots#black woman

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

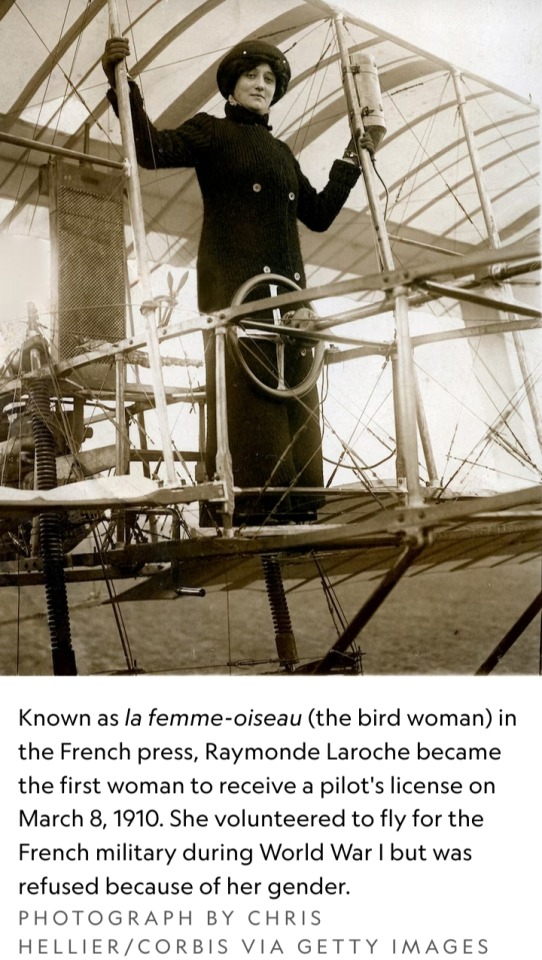

By Rachel Hartigan

Published: 9 March 2023

The history of the first women who flew is a tale of breathtaking bravery and lives cut tragically short.

On 8 March 1910 — 113 years ago today — Raymonde de Laroche, a former Parisian stage actress, became the first licensed female pilot in the world.

Nine years later, she was killed when the experimental aircraft she was flying dove into the ground.

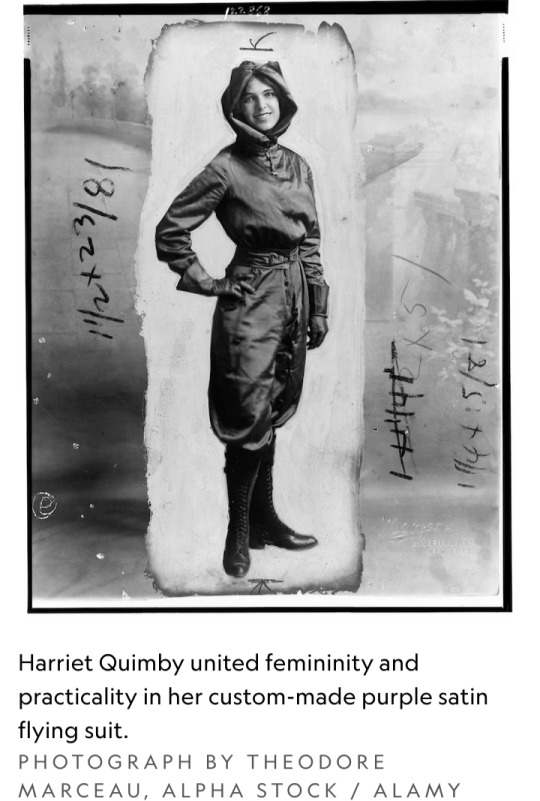

Harriet Quimby, a well-known journalist, became the first American woman to obtain a pilot’s license in 1911.

She died a year later when her new plane pitched her into Boston Harbor.

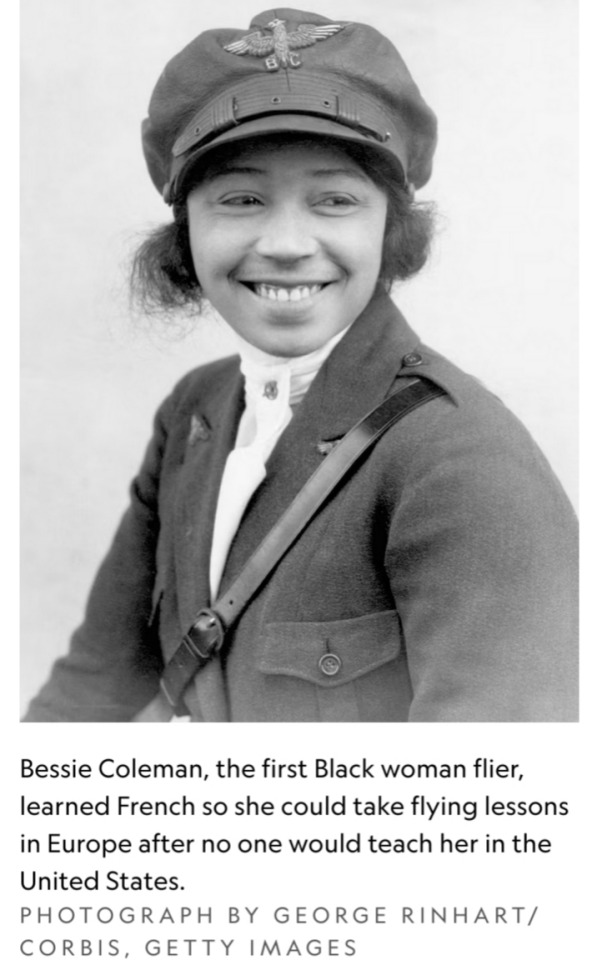

In 1921, Bessie Coleman was the first Black woman to receive a pilot’s license — she had to travel to France to find a flight school that would teach her.

But five years later, she was killed when a wrench got caught in her plane’s controls, sending the plane plummeting.

Flying was perilous in aviation’s earliest days.

"The planes were flimsy contraptions fashioned from bamboo, wire and fabric,” according to the late historian Eileen Lebow.

They didn’t have seat belts or even a roof to hold the pilot should the aircraft flip over.

Yet women like Laroche, Quimby and Coleman were willing to risk their lives for the freedom that flights promised.

“Aviation was a new profession seemingly free from the gender expectations and sex typing that limited women elsewhere,” noted historian Susan Ware at the National Air and Space Museum’s inaugural Amelia Earhart Lecture in Aviation History in 2022.

“Women were getting in at the beginning.”

For many of them, the thrill of flying was intoxicating but so was the opportunity to be assessed on their own merits.

“These women wanted to be judged as human beings rather than as women,” says Ware.

Coleman especially saw flight as a path toward broader gender and racial equality.

"I knew we had no aviators, neither men nor women, and I knew the Race needed to be represented along this most important line,” she said shortly after she returned to the United States from France in 1921.

“I thought it my duty to risk my life to learn aviating and to encourage flying among men and women of the Race who are so far behind.”

Before she died, she’d planned to open a flight school that would welcome African American aviators.

Many early women fliers shared the dream that achievement in this field would lead to more independence.

As one journalist and amateur pilot wrote in 1930, “A woman who can find fulfillment in the skies will never again need to live her life in some man’s spare moments.”

Some of that independence would come from the ease of travel that aviation promised in its earliest incarnation.

Many people, including Amelia Earhart, believed at first that airplanes would become as commonly owned by families as bicycles and automobiles already had.

Other women embraced the financial independence that they thought the new field would offer.

Neta Snook, whose first solo flight was in a plane she rebuilt, made her living by offering up her plane for aerial advertising, test flying experimental aircraft, taking paying passengers up for aerial tours, and teaching beginning fliers, including Earhart.

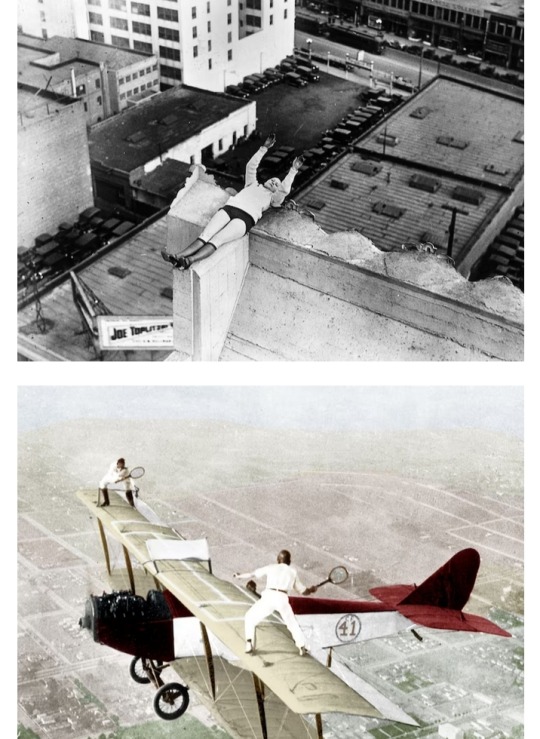

Gladys Roy, on the other hand, earned good money as a stunt pilot, dancing the Charleston and playing tennis on the wings midflight for amazed crowds at air shows.

(Snook retired from aviation when she became pregnant in her mid-twenties and lived to be 95; Roy died at 25 when she accidentally stepped into a propeller.)

Sisters Katherine and Marjorie Stinson took a more long-term approach, establishing a flight school in Texas with their mother and brother that trained, among others, Canadian pilots in the run up to World War I.

When the U.S. entered the war, the country’s civil aviation — including the Stinson School for Flying — was shut down.

Katherine went to Europe to serve as an ambulance driver while Marjorie became an aeronautical draftsman for the Navy.

War and the development of commercial aviation conspired to dampen women’s hopes of equality in the air.

Experienced women pilots such as LaRoche and Katherine Stinson volunteered to serve in their countries’ nascent air forces during World War I.

They were denied, the military preferring to train unseasoned men.

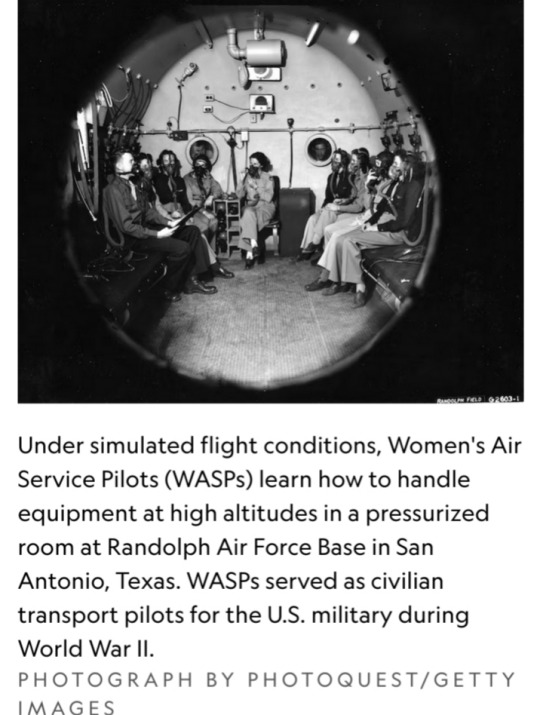

The same pattern occurred in World War II, although Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) did ferry U.S. military planes as civilian pilots during the conflict.

(The Soviet Union, however, had three female air combat regiments.)

The dream of every family owning a private plane never did materialize; the infrastructure required would have been too extensive.

Instead, the commercial aviation industry developed, hiring men — many of whom had been trained as pilots by the military.

It was no use pointing out, as Earhart did, that "if women had access to the training and equipment men had we could certainly do as well."

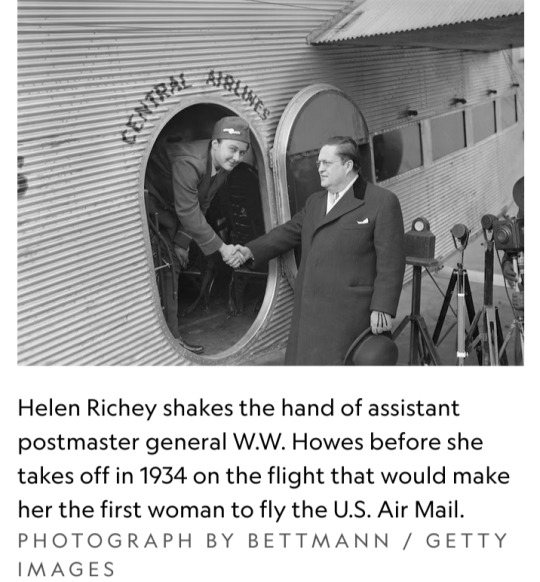

Helen Richey became the first female commercial pilot in 1934 but was hounded out of her job.

The U.S. Commerce Department, under pressure from the all-male pilots’ union, decreed that women weren’t allowed to fly scheduled routes in bad weather.

(They’d previously considered “grounding female pilots for nine days a month during menstruation,” according to Ware).

There wouldn’t be another female commercial pilot until 1973, when Emily Howell Warner was hired by Frontier.

#Raymonde de Laroche#Harriet Quimby#Bessie Coleman#Eileen Lebow#Susan Ware#National Air and Space Museum#Amelia Earhart#Neta Snook#Gladys Roy#Katherine and Marjorie Stinson#Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs)#Helen Richey#Emily Howell Warner#female pilot#International Women's Day#International Women's Month#National Geographic#Nat Geo

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inspiring Women: Bessie Coleman - 2022

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

BESSIE COLEMAN // AVIATOR

“She was the first African-American woman and first Native American to hold a pilot license. She earned it from the Federation Aeronautique Internationale on June 15 1921. She had an early interest in flying however AAs, NAs and women had no flight training opportunities in the US, so saved and obtained sponsorships to go to France for flight school. She became a high-profile pilot in notoriously dangerous air shows in the US. She died in a plane crash in 1926 and wasn't able to start a school for African-American fliers.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The kids are all right.

youtube

This is a frustrating story, because it seems like the one person who didn't learn anything is the teacher. (I was going to write a snarky quip refuting her, but then I realized one might debate whether a "hero" requires fame, or only deeds, or some secret third thing. Good grounds for a high school debate, but not to nitpick a third grader.)

However, I like this news story because it doesn't center the closeminded teacher. Instead, it centers both historical black aviator Bessie Coleman and one of her youngest fans, third grader Alex Williams. Part of the video is Alex telling us in her own words why Bessie Coleman matters to her and to the world, and why Alex refused to follow a teacher's instructions.

(Nevertheless — civil disobedience 101 — you gotta be prepared for negative consequences, if you defy orders, break rules, or challenge authority. Alex got a mini lesson in that, too. The story of Bessie Coleman shows that for some things, it's worth it.)

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bessie Coleman, 1921.

Née le 26 janvier 1892 à Atlanta, Texas, Bessie Coleman est entrée dans l'histoire comme la première femme noire d'origine amérindienne à devenir pilote d'avion. Issue d'une famille de 13 enfants, sa jeunesse est marquée par la pauvreté et les défis de la ségrégation raciale. Malgré ces obstacles, elle nourrit des rêves ambitieux dès son plus jeune âge.

Après avoir terminé ses études dans une école ségréguée, Bessie s'installe à Chicago où elle travaille comme manucure. Inspirée par les récits des pilotes revenant de la Première Guerre mondiale, elle développe une passion pour l'aviation. Cependant, son chemin vers le ciel est semé d'embûches. Aux États-Unis, aucune école de pilotage n'accepte de femmes noires. Refusant de se laisser décourager, elle apprend le français et s'envole pour la France.

Là, elle s'inscrit à l'école de pilotage des frères Caudron. Après seulement sept mois de formation, Bessie fait sensation en obtenant sa licence de pilote de la Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, brisant ainsi les barrières raciales et de genre dans l'aviation.

De retour aux États-Unis, elle fait sensation. Elle se spécialise dans les spectacles aériens, exécutant des cascades époustouflantes et gagne le surnom de « Queen Bess ». À travers ses performances, elle rêve d'ouvrir une école de pilotage pour les Afro-Américains.

Mais sa carrière est tragiquement écourtée. Le 30 avril 1926, lors d'une répétition pour un spectacle aérien en Floride, elle est éjectée de son avion et meurt sur le coup. Son héritage, cependant, perdure. Bessie Coleman reste une figure emblématique, symbolisant le courage, la détermination et le pouvoir de briser les barrières.

Son rêve de former des pilotes afro-américains se concrétise en 1928 avec la création, par William J. Powell, du Bessie Coleman Aero Club et de la Bessie Coleman Flying School à Los Angeles. En 1931, des pilotes de Chicago lui rendent hommage en survolant sa tombe et y répandant des fleurs, une tradition qui perdure chaque année jusqu'à la retraite de tous les pilotes constituant le groupe d'origine. Son nom est donné à des rues et lieux publics dans diverses villes. En 1995, la poste américaine émet un timbre à son effigie. Bessie est également honorée par des intronisations posthumes dans des halls of fame et inspire une bande dessinée (Black Squaw) et le nom d'une montagne sur Pluton (Coleman Mons).

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbie Inspiring Women Doll, Bessie Coleman Collectible Dressed in Aviator Suit with Helmet and Goggles

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bessie Coleman was beautiful!

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

4 notes

·

View notes