#Baden-Württenberg

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

LORD’S DAY ✝️

#late#Ulm Minster#Ulmer Münster#Germany#Deutschland#Baden-Württenberg#Lutheran#cathedral#church#25th Sunday OT

0 notes

Photo

Tussilago

Ubiquitous plant, this one in the post-flower stage, soaking in drizzle. Tübingen, BW.

#iPhone#iPhone13Pro#botanical#Tussilago#coltsfoot#Tübingen#Tuebingen#Baden-Württenberg#Germany#looking down#cropped

0 notes

Text

youtube

kibaszott AI-botoló muszka gecik arra nem figyelnek hogy ne {német név}{négyjegyű szám} legyen az ÖSSZES Orbánt éltető top komment amit upvoteolgatnak

hallo Deutsche Freunde aus Baden-Württenberg Oblast'

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A invenção do automóvel foi vista como bruxaria e loucura na época. A coragem de uma mulher mostrou o invento ao mundo.

O surgimento do automóvel deve muito a uma mulher: Bertha Benz. Ela foi a pioneira em testar um veículo motorizado, há 130 anos. Para homenageá-la e também a todas as mulheres no seu dia internacional, a Mercedes-Benz divulgou um vídeo que retrata esse momento especial.

Casada com Carl Benz, inventor do primeiro automóvel, Bertha ajudou o marido no desenvolvimento do Patent-Motorwagen, primeiro carro a ser patenteado na história, no início de 1886. Meses depois o modelo foi lançado, mas ainda carecia de confiança das pessoas para se tornar um produto de massa.

O primeiro veículo do mundo foi o Patent-Motorwagen, criado em 1886.

Por isso, em 1888, escondido de Carl, ela decidiu fazer uma viagem com o Motorwagen. A aventura começou no início agosto e teve a companhia dos dois filhos, Richard (14 anos) e Eugen (15).

A família, sem o marido, saiu de Mannheim, na Alemanha, onde moravam, e percorreu 104 km pela região de Baden-Württenberg, alcançando Pforzheim, cidade natal de Bertha. Ela não se intimidou pelo fato de que alguns trechos das estradas, que normalmente eram usados apenas por cavalos e carruagens, eram tudo menos adequados para o automóvel.

O desprendimento dela foi considerado a primeira viagem de longa distância com um automóvel que se tem notícia. A ‘pilota de testes’ queria mostrar a funcionalidade da invenção, que até então não havia despertado interesse nas pessoas para comprá-la.

Durante a jornada de ida Bertha teve de usar da criatividade, e do conhecimento mecânico, para resolver problemas que surgiam, como pode ser visto no vídeo. Primeiro recorreu a um alfinete de chapéu para desentupir o tubo de combustível. A peça fora obstruída por impurezas geradas pelo solvente derivado de benzina que Bertha comprou na farmácia para usar como combustível.

Já o curto-circuito num fio foi solucionado com a liga de uma meia usada como isolante. Na viagem, ela desenvolveu o conceito da lona de freio. Ainda teve de empurrar o carro por vários quilômetros quando acabou o combustível.

No trajeto de volta ela optou por um caminho mais curto, de 90 km, pela margens do rio Reno.

Com a viagem, Bertha atingiu o objetivo de mostrar a funcionalidade do Patent-Motorwagen e atraiu clientes para a oficina de Carl interessados no veículo.

Com a experiência da esposa e dos filhos, ele também corrigiu algumas falhas no veículo e aplicou outras melhorias. Nascida em 1849, Bertha Ringer casou-se com Carl em 1872, um ano depois dele criar a empresa Benz. Desta união, nasceram cinco filhos. Em 1927 a sua companhia se aliou à Daimler, surgindo a Daimler-Benz, que mais tarde viraria apenas Daimler AG. O grupo é proprietário da Mercedes-Benz.

Bom anoitecer pra nós! Lucas Lima

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illerkirchberg: Getrauert wird nur, wenn der Täter Deutscher war

Info-direkt:»Der mutmaßliche Ermordung eines 14-jährigen Mädchens durch einen Asylwerber aus Eritrea in Illerkirchberg (Baden-Württenberg) legt die widerliche Doppelmoral der bundesdeutschen Eliten offen. Ein Kommentar von Thomas Steinreutner Ein Beispiel dafür liefert Bundestagsabgeordneter Bernd Riexinger („Die Linke“) [...] Der Beitrag Illerkirchberg: Getrauert wird nur, wenn der Täter Deutscher war erschien zuerst auf Info-DIREKT. http://dlvr.it/SdwKkF «

0 notes

Text

TÜBINGEN, Baden-Württenberg, Germany 🇩🇪 by @der_heimatfotograf

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Desert Fox: Separating the myth and the man of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel

Sweat saves blood, blood saves lives, and brains saves both.

- Field Marshal Erwin Rommel

War hero or Nazi villain? Field Marshal Erwin Rommel is, to this day, the subject of heated debate. He was the “Desert Fox,” revered by Allied Forces for his supposed chivalry, and allegedly implicated in the “Valkyrie” plot to assassinate Hitler.

But present day historians have increasingly come to re-examine the life and the legend of this most iconic of World War Two generals.

I first became interested in this question after reading Corelli Barnett’s magisterial account ‘The Desert Generals’ back when I was in Sandhurst. I read other World War Two books before then of course but it was only at Sandhurst did I first give serious consideration towards Rommel as ‘the Good German’ general. I read other books too like General Sir David Fraser’s ‘Knight’s Cross: a life of Field Marshal Rommel’ as a stand out one on military stuff but a very cursory examination of his early life and beliefs.

Rommel was a legend in the making.

Whichever side of the debate one falls on there is no doubt that Erwin Rommel, was one of the most celebrated and respected generals of the Second World War and indeed, some even say one of the greatest generals of all time. His prowess on the battlefield earned him more than a battlefield earned him the admiration of both his men and his enemies alike, with adversaries lining up to pay tribute to their greatest foe in the field.

“We have a very daring and skilful opponent against us, and, may I say across the havoc of war, a great general,” said no less than Winston Churchill himself of Rommel, just after the war ended in his book on the conflict, The Second World War.

When Churchill came under fire in the press for praising a man seen as a Nazi, he doubled down, commenting “He also deserves our respect because, although a loyal German soldier, he came to hate Hitler and all his works, and took part in the conspiracy to rescue Germany by displacing the maniac and tyrant.

For this, Rommel paid the forfeit of his life. In the sombre wars of modern democracy, chivalry finds no place… Still, I do not regret or retract the tribute I paid to Rommel, unfashionable though it was judged.”

Indeed, the extent to which Rommel was a Nazi is one of the great questions that has been asked since the war and one that is debated to this day. Rommel, while respected by those who fought him from afar as generals and indeed, thought of a genius to many of those who fought beneath him in the Wehrmacht, has often faced criticism of his tactics and his decision making, with some post-war writers holding him up as a man prone to erratic behaviour on the battlefield and a great sufferer from the stresses of the job.

“Rommel was jumpy, wanted to do everything at once, then lost interest. Rommel was my superior in command in Normandy. I cannot say Rommel wasn’t a good general. When successful, he was good; during reverses, he became depressed,” said Sepp Dietrich, who fought under Rommel in France and ended the war as the most senior figure in the Waffen-SS.

A similar sentiment was expressed by Luftwaffe field marshal Albert Kesselring, a contemporary of Rommel’s and an officer of similar rank, who later wrote: “He was the best leader of fast-moving troops but only up to army level. Above that level it was too much for him. Rommel was given too much responsibility. He was a good commander for a corps of army but he was too moody, too changeable. One moment he would be enthusiastic, next moment depressed.”

Who was this great man then? We know him today as a great tactician, a charismatic leader, a respected general and the last German participant in the so-called “clean war”. But how true are those assessments? Was the Desert Fox as chivalrous as his enemies thought him to be?

Rommel was far from just a Second World War hero – he distinguished himself in World War One too.

Rommel graduated from the military academy in Gdansk – then known as Danzig and an integral part of Germany – in 1912 and was immediately posted back to his home region of Baden-Württemberg.

When war broke out in 1914, Rommel was ready to face his first major conflict posting. As a battery commander within the 124th division of the German army, he would distinguish himself and gain his first recognition from the higher-ups.

Erwin saw his first action at the age of 23 on August 22, 1914, near the French town of Verdun. Rommel led his platoon into a French garrison, catching them by surprise and personally leading the charge ahead of the rest of his men, earning credits for bravery and ingenuity. He would be awarded the Iron Cross, Second Class, for his actions, a promotion to First Lieutenant and a transfer into the Royal Württemberg Mounted Battalion as a company – rather than platoon – commander.

Rommel would go on to fight in the German campaigns in Italy and Romania, with particular note being taken by the German Army hierarchy of his conduct in the Italian campaign. The Royal Württemberg Mounted Battalion fought at the Battle of Caporetto, the twelfth battle to be fought along the Isonzo River in modern-day Slovenia, and one that would go down as probably the largest military defeat in the history of Italy.

Rommel would play a central role, leading the Royal Württemberg, with just 150 men, to capture an estimated 9,000 Italians, complete with all their guns, for a cost of just 6 of his own men.

The young Rommel used the challenging, mountainous terrain of Caporetto – now known as Kobarid – to outflank the Italians and convince them that they were totally encircled by Germans, when in fact there was just one battalion. Fearing that they were surrounded, the Italians surrendered en masse and were surprised to find that so few men were able to capture them.

The efforts of the German Army to break into the Italian Front through the Slovenian Alps – at the time, part of Italy – were vital in furthering an advance towards Venice, though the Germans were eventually stopped and turned back.

Rommel was awarded the Pour Le Merite award by the Kaiser for his leadership at Caporetto, but also gained the respect and loyalty of his men, who were not only impressed by the way in which his tactics had won the battle, but also by the way that he had stood up to the German Army high command and argued for more and better food for his men. The legend of Rommel was growing apace.

Rommel was an effective teacher as well as a military leader.

It shouldn’t be too surprising that Rommel was a capable teacher: his father had been a headmaster, while the ability to communicate his ideas effectively in the field would lead to some of his most enduring military victories. There was no point coming up with a revolutionary tactic to win a battle if you couldn’t then inform and inspire your men well enough for them to then go and carry it out.

At the end of the First World War, Rommel was entering his late 20s and had already been widely feted for his military prowess. While it might have seemed a little dull compared to the derring-do on the Isonzo, the role of the Royal Württenberg Mountain Battalion lay much closer to home, with German society slowly disintegrating into civil wars between, on the left, socialists who wanted Germany to undergo a revolution similar to that which had recently occurred in Russia, and on the right, groups such as the Freikorps, disgruntled ex-soldiers and nationalist, anti-communist paramilitaries that would go on to form the kernel of the Nazi Party.

Rommel, recently promoted again to the rank of Captain, was ordered to use his soldiers in a policing capacity, putting down insurrections all over southern Germany. It was during this period that he showed some of the sense of restraint that would distinguish his conduct in North Africa during World War Two, trying to avoid the use of force against crowds of civilians where possible.

After the Weimar Republic took hold, however, the country somewhat stabilised and Rommel found himself in Dresden, teaching new recruits. He had been promoted in turn to Major, then Lieutenant Colonel, placing him in the very highest echelons of the Treaty of Versailles-reduced German Army.

He was recognised as one of the prime instructors in that army and wrote a book, “Infantry Attacks”, that furthered his theories on warfare and explained his experiences in the Izonzo – it sold incredibly well and increased Rommel’s personal fame, as well as bringing him to the attention of Adolf Hitler, who was known to have read the book.

Rommel met Hitler in Goslar, Germany in 1934, while Rommel was posted as battalion commander. Hitler’s charisma and promises to reestablish Germany as a world power after the crippling results of World War I inspired Rommel to become a fervent supporter of the Nazi Party.

The two men had several encounters following this, and Rommel rose through the ranks on Hitler’s personal recommendation. But it was ultimately Hitler’s liking for Rommel’s book Infantry Attacks that led to his becoming the commander of Hitler’s personal guards during his tour of the Sudetenland.

By the 1930s with Hitler fully secured in power, the German Army, for whom Rommel worked, and the Nazi state were more and more inseparable. It would be this coming together that prompted a major dilemma for the career soldiers such as Rommel: did the duty lie to their country, and whoever might be governing it, or to the party, that was coming to define what that country was about?

Rommel was a committed Nazi and not the “decent face” of the German Army.

Rommel’s antagonism wasn’t so much against Nazism as it was towards the Nazis in leadership who led it. His committment to Nazism eroded as the war took a wrong turn and as Hitler increasingly became erratic in his military decision making that Rommel grew increasingly frustrated.

Just how much of a Nazi Rommel was is one of the biggest questions that is debated about him to this day. It is largely due to the Rommel myth that was perpetuated by the likes of Winston Churchill after the war that Rommel was taken by the victorious Allies as “the good Nazi”, or the honest general who happened to be being ordered about by the Nazis, merely a career soldier who followed orders and stayed out of politics.

Let’s put that one to bed, here and now. Rommel was an early adopter of the Nazi Party and a committed believer in the ideals of National Socialism, while also being an officer who regularly disobeyed orders – making both commonly held assumptions wrong.

That said, he is one of the few figures of that period who is still revered in Germany, who still has streets named after him and memorials in his honour. It seems that the myth persists in his homeland too, despite countless books and articles to the contrary.

One such author attempting to shake this idea from the public consciousness is Wolfgang Proske, a historian and history professor from Rommel’s hometown on Heidenheim, who has written 16 books about his town’s most famous son. “Rommel was a deeply convinced Nazi and, contrary to popular opinion, he was also an anti-Semite. It is not only the Germans who have fallen into the trap of believing that Rommel was chivalrous. The British have been convinced by these stories as well,” he told British newspaper The Independent in 2011 when a new memorial to the Field Marshal was unveiled.

“At the time when Rommel marched into Tripoli, more than a quarter of the city’s population were Jews,” Proske continued, “There is evidence which�� shows that Rommel forbad his troops to buy anything from Jewish traders. Later on, he used the Jews as slave laborers. Some of them were even used as so-called ‘mine dogs’ who were ordered to walk over minefields ahead of his advancing troops.”

While Rommel was never a member of the Nazi Party, it is widely known that Wehrmacht figures, particularly high-ranking ones such as Rommel, welcomed Hitler coming to power. Those, like Rommel, whose backgrounds had shut them off from the highest ranks of the Kaiser’s forces, saw the new government as one that would see them move to the top of the tree and as such were generally in favor of it.

Goebbels himself wrote in 1942, when Rommel was in the running for the role of Commander-in-Chief of the Wehrmacht, that the Field Marshal was ”ideologically sound, is not just sympathetic to the National Socialists. He is a National Socialist; he is a troop leader with a gift for improvisation, personally courageous and extraordinarily inventive. These are the kinds of soldiers we need.”

Rommel owes a large part of his fame to the fact that he made fools of opposing general - well almost (Patton would disagree).

Rommel’s prowess as a general is unquestioned. On the back of his heroics as a low-level officer in World War One added to by his role teaching at the forefront of modern military tactics, he was perfectly positioned to lead the Nazi war machine into the second conflict.

When the war began, he was leading Hitler’s personal protection battalion – so much for a man who kept a distance from the center of Nazi power – and thus was privy to the highest levels of discussions regarding tactics, particularly the way in which to use mechanized infantry such as tanks. After the early successes in Poland, Rommel moved with the front to France and commanded Panzer units, before distinguishing himself against the British at Arras and leading the drive towards Dunkirk.

With the British regrouping on the other side of the Channel after a crushing defeat – which, lest we forget, Dunkirk was – the focus turned to North Africa, where Rommel would lead the newly-established Afrika Korps. He was the superstar of the German Army, a reputation largely built on his ability to vanquish the British, whom he would now face again in the desert. It was at this time that his nickname, The Desert Fox, was coined by the British press, who sought to create a figure against which the war could be fought.

The legacy of Rommel as the acceptable Nazi could be seen to stem from this point when the media in Britain saw fit to create a worthy adversary for their troops to combat. Rommel was thought to be an old-style soldier rather than an out-and-out Nazi: though we have seen that he was a Nazi, and he had arguably committed war crimes by summarily executing prisoners in France just weeks before.

Come the victory of the British at Tobruk and El Alamein, the British propaganda machine had even more than a noble adversary. They had a noble adversary against whom they had lost in Europe and then subsequently defeated: when the characters of the British side, Auchinleck and Montgomery, were spoken of, they needed someone of equal weight to make their victories seem even more heroic, a role that fit Rommel perfectly.

With morale at home low after the Dunkirk evacuation, the victories in North Africa were vital to keeping spirits up, and a glorious victory against an equally glorious enemy sounded even better. Churchill himself called Rommel an “extraordinary bold and clever opponent” and a “great field commander” in the House of Commons in 1942 – after he had just been defeated.

Rommel’s reputation for chivalry in North Africa might not just be down to his own intentions.

Of course, some aspects the Allied propaganda about Rommel – that he was a fair fighter, that he respected the ideals of chivalry when other Germans didn’t – were generally true.

It is undoubted that, by and large, Rommel adhered to the rules of war when plenty of Nazi generals didn’t, but it bears mentioning that the reason that so many German generals were so callous is that they were ordered to be like that. Orders within the Nazi war machine came down from high and were often brutal in their nature: summary execution of prisoners, rounding up of Jews and other minorities, scorched earth policies. That was just the orders aimed at enemies: often generals would be ordered to stand their ground to the death when all military logic told them to make a tactical retreat.

Rommel’s dedication to upholding the “war without hate” as he called the more traditional methods of war is up for debate, but certainly, he did take measure to negate the harsher aspects. That said, there are other factors that question whether his commitment to the “war without hate” was intentional, circumstantial or ideologically-driven.

When most German generals were likely to commit acts of ethnic cleansing, Rommel was not generally faced with the question. North Africa, where this reputation was developed, had hardly any Jews, for example, and other potential targets for Nazi aggression were protected by being citizens of Italy and Rommel was wary of standing on the toes of their allies. That said, many within the North African Jewish community are reported as having felt that they were spared from the horrors suffered by Jews in Europe by the actions of the Afrika Korps, led by Rommel.

It is also widely accepted that he refused to execute captured Jewish prisoners and hated the use of slave labour. As far as his own troops were concerned, Rommel repeatedly refused orders directly from Hitler. When, at the end of the second Battle of El Alamein, Hitler commanded him directly not to retreat and to show his soldiers “no other road than that to victory or death.”

Knowing that it was impossible for him to defeat the advancing British, who massively outnumbered his forces, Rommel chose to ignore the letter from the Fuhrer and fled all the way across North Africa to Tunisia rather than face death in the sand. While he was way too politically powerful to be censured by Hitler, actions such as this were contributory to a wider feeling among the Nazi hierarchy that Rommel was not one of them.

He was a PR superstar in Germany, but was both respected and later suspected by the Nazi leadership.

Rommel’s reputation within Germany might well have made him untouchable for the Nazi hierarchy, even when he did things that were in direct contradiction of the ideological and military strategy of the regime. They had invested so much time and so much weight in making him the poster boy of their propaganda regime that, when Rommel turned out to be less than what they had hoped for, they could not easily dispose of him.

On paper, he was the perfect fit for their media machine: he was an early adopter of Nazism, already a hero from the First World War and an excellent general, with victories aplenty. Moreover, they could cite the Allies reverence for him in their favor, and Rommel himself was comfortable in the spotlight and relished the attention.

Hitler was always wary of building up any one single figure too far – lest he be challenged himself – but Goebbels, the chief propagandist, knew an opportunity when he saw it and Rommel could not be passed up. As Rommel’s media image grew and grew, he became the darling of the public back home, but in the corridors of power in Berlin, there were plenty of higher-ups who were less convinced of his powers.

Even from the early days of the war in 1941, when Rommel was in France, some of those who fought alongside him were doubting just how effective he actually was a general. By the time that the war in North Africa had turned against him in 1943, the German furthest expansions were contracting: the Battle of Stalingrad had been lost in February and Rommel departed Tunisia in May.

It might have made sense if the Nazis had thought Rommel their best general, to send him to the Eastern Front where the war was being lost. Perhaps, too, the brutal nature of the war on the Ostfront was seen as beyond Rommel’s nature: this was not the time or place for “war without hate”, in the eyes of the Nazi leadership.

Instead, he was dispatched to Italy. As Italy fell, Rommel was demoted from the head of the campaign to second in command to Albert Kesselring, alongside whom he had served throughout the North Africa campaigns.

Later in France, Rommel was the man in charge of building the Atlantic Wall that would protect Nazi-occupied France from Allied invasion: though he had warned heavily that his experiences in North Africa had taught him that land and sea defences would be nothing if air supremacy allowed the Allies to destroy the Nazi army from above, Rommel was ignored.

After the defeat in North Africa, the retreat through Greece and Italy and the failure to stop the D-Day invasions, his reputation as a superstar general back home was in tatters.

Rommel’s reputation got a huge boost because of a 1951 film.

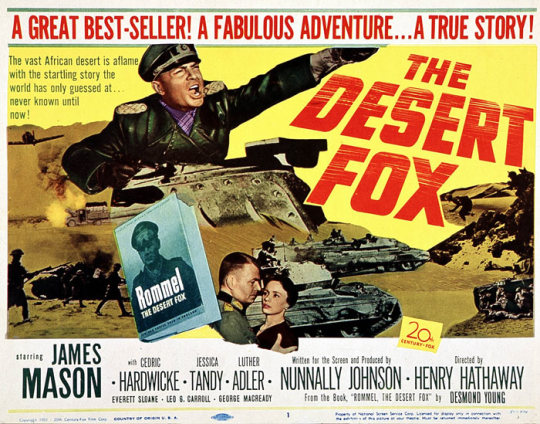

If Rommel’s reputation as a great leader was undermined by the catastrophic defeats on the African, Italian and Western Fronts in the last two years of the war, why was it that the so-called “Rommel Myth” was so pervasive after the war? The theories are numerous, but one major contributing factor must be the success of the 1951 film, The Desert Fox. Rommel was played by the iconic actor James Mason who won critical acclaim for his role.

Rommel was a well-known figure in Allied countries and in 1950, the first biography of the “good German” was released in the UK. Written by Desmond Young, a British brigadier-general who had himself been captured by Rommel during the war, “Rommel: The Desert Fox” was incredibly popular in Britain and cemented the position of the vanquished general as the acceptable enemy.

His later involvement in the 1944 plot against Hitler did a lot to wash Rommel of the stain of Nazism – conveniently forgetting the decade or so that he had spent close to the top of the regime – and his position as the general who was beaten “fair and square” endeared him to a British audience. After all, it’s much easier to build heroes of your own generals when they have beaten a general that you also respect.

The 1951 film of The Desert Fox further spread the myth and was widely popular in the UK. The narrative of Rommel, the good German, being defeated by the heroic British in the clean war in North Africa was a far more palatable one in the burgeoning Cold War than one that emphasised the horrible destruction that had come through the Soviet victory in the East.

There could be little appetite for a war with Russia when people were constantly being reminded of the horrific images that had emerged from the Eastern Front. Thus, the clean general of the fair fight in North Africa was an enticing idea.

The Germans, too, were all too pleased to go along with Rommel as their figurehead. Their army had been severely curtailed after their defeat, but there was a clamour to de-Nazify the Wehrmacht and remove the stigma from the German armed forces. The Bundeswehr, the new German army, was more palatable to a post-war world when it could be seen as the legacy of good soldiers lead by bad politicians rather than an integral and vital part of the Nazi war machine.

Thus, the idea of The Desert Fox was created and, to a large extent, still persists. He remains the only Nazi to be lionised within Germany: public squares and streets bear his name, as does the largest barracks of the Bundeswehr. Whether such a status is deserved, however, is still a question about which historians continue to argue.

During the first half of 2020 many countries have been reconsidering the roles of their historical figures - remembered in statue form - due to their controversial views or actions from today’s point of view. In Britain, France and Belgium, statues of figures associated with the colonial past have become the target of public criticism in some quarters. In the United States, not only statues of Confederate figures who defended slavery during the American Civil War were destroyed or even demolished, but also, for example, the discoverer of America, Christopher Columbus.

In Germany a similar process was also underway. The monument to the Wehrmacht Marshal Erwin Rommel in Heidenheim came under severe renewed scrutiny.

Germany's memorial to Field Marshal Erwin Rommel is perched on a hillside overlooking the middle-class town of Heidenheim an der Brenz where he was born 120 years ago. The words inscribed on the white limestone monument describe the legendary Second World War general as "chivalrous", "brave" and as a "victim of tyranny"

The monument, which was built in 1961 by the German Afrikakorps Association, aroused long-term controversy and in the past was repeatedly damaged by inscriptions that called Rommel a Nazi. In 2014, Heidenheim City Hall expressed its intention to contrast the monument with another memorial building. By 2020 those calls took on a greater momentum.

The German artist Rainer Jooss was brought in by the municipal authorities to re-interpret the existing monument without having to destroy it completely. Jooss took as his starting point to focus on other parts of Rommel’s legacy. It was little known that Rommel had large minefields laid during the campaign of German troops in North Africa during World War II. In Libya and Tunisia alone, at least 3,300 people have lost their legs and another 7,500 have been maimed since the statistics were kept in the 1980s. So Jooss designed black silhouette cut out of a maimed child victim of war to complement the monument.

“The monument does not represent the truth, but encourages us to look for it,” said Bernhard Ilg, Mayor of Baden-Württemberg, at the presentation of the monument’s design unveiling in July 2020. Jooss was more stoic. Joos believed it would be a mistake to remove the Rommel monument altogether,"If we let grass grow over it, that would mean the end of the important task of dealing with history.”

The artist behind the modification to the Heidenheim monument said his statue was purposefully made to look small next to the impressive limestone bloc."I wanted to confront the monumental (features) of the original memorial with the fragility of a land mine victim.” Jooss wanted and hoped that it was up to “the next generations to make a picture of themselves based on factual histography.”

Yet eminent historians have since dismissed the fresh silhouette plaque as a transparent attempt to avoid addressing the deep seated questions about Rommel. Indeed Rommel’s privileged position to being seen as the ideal role model for the Bundeswehr (the unified armed forces of Germany and their civil administration and procurement authorities). While recognising his great talents as a commander, they point out several problems: such as Rommel's involvement with a criminal regime and his political naivete. However, there are also many supporters of the continued commemoration of Rommel by the Bundeswehr, and there remains military buildings and streets named after him and portraits of him displayed.

The politician scientist Ralph Rotte called for his replacement with Manfred von Richthofen. Historian Cornelia Hecht opined that whatever judgement history will pass on Rommel – who was the idol of World War II as well as the integration figure of the post-war Republic – it was now the time in which the Bundeswehr should rely on its own history and tradition, and not any Wehrmacht commander. Jürgen Heiducoff, a retired Bundeswehr officer, had written that the maintenance of the Rommel barracks' names and the definition of Rommel as a German resistance fighter are capitulation before neo-Nazi tendencies. Heiducoff agreed with Bundeswehr generals that Rommel was one of the greatest strategists and tacticians, both in theory and practice, and a victim of contemporary jealous colleagues, but argued that such a talent for aggressive, destructive warfare was not a suitable model for the Bundeswehr, a primarily defensive army. Heiducoff criticised those Bundeswehr generals for pressuring the Federal Ministry of Defence into making decisions in favour of the man who they openly admire.

Rommel has had his supporters from this avalanche of revisionist criticism. Historian Michael Wolffsohn supported the Ministry of Defense's decision to continue recognition of Rommel, although he thought the focus should be put on the later stage of Rommel's life, when he began thinking more seriously about war and politics, and broke with the regime. Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (MDR) reported that, "Wolffsohn declares the Bundeswehr wants to have politically thoughtful, responsible officers from the beginning, thus a tradition of 'swashbuckler' and 'humane rogue' is not intended".

According to authors like Ulrich vom Hagen and Sandra Mass though, the Bundeswehr (as well as NATO) deliberately endorses the ideas of chivalrous warfare and apolitical soldiering associated with Rommel. At a German Ministry conference soliciting input on the matter, Dutch general Ton van Loon advised the German Ministry that, although there can be historical abuses hidden under the guise of military tradition, tradition is still essential for the esprit de corps, and part of that tradition should be the leadership and achievements of Rommel. Historian Christian Hartmann opined that not only Rommel's legacy was worthy of tradition but the Bundeswehr "urgently needs to become more Rommel".

There are other historians who have tried to take a middle path on the continued controversy of Rommel’s legacy. Historian Johannes Hürter believed that instead of being the symbol for an alternative Germany, Rommel should be the symbol for the willingness of the military elites to become instrumentalised by the Nazi authorities. As for whether he can be treated as a military role model, Hürter writes that each soldier can decide on that matter for themselves. Historian Ernst Piper argued that it was totally conceivable that the Resistance saw Rommel as someone with whom they could build a new Germany. According to Piper though, Rommel was a loyal national socialist without crime rather than a democrat, thus unsuitable to hold a central place among role models, although he should be integrated as a major military leader.

Whether one is for and against Rommel such debates take place because he is dead in conveniently ambiguous circumstances.

Recovering from skull fractures in hospital, he missed the main event - the 20 July Bomb Plot 1944 - insitigated by other senior German army officers. Hitler survived the blast, and immediately set about executing the plotters.

While Rommel had lots of contact with many key conspirators and was generally aware of the movement(s) to assassinate Hitler, there is no direct evidence that he knew about the July 20th plot in advance, let alone was involved in any detailed planning. Several conspirators allegedly confessed during interrogation that he was involved and, like Speer, his name was found on Goerdeler’s list of possible participants in a new German government.

Rommel was listed among various possibilities for Reich President. Unfortunately for him, there was no question mark or other notation, as in Speer’s case, which indicated that he was unaware of the designation.

He maintained his innocence when confronted by General Burgdorff on the day he died and also told his wife and son that he had played no part in the events of July 20th. But ultimately, there’s no way to know what he was or was not aware of. He took that with him to the grave.

The list of members of the 20 July plot doesn´t name Rommel as part of the attempt to kill Adolf Hitler. But: Rommel was blamed of having known of plans to do so. So he was forced to commit suicide.

On 19 th October 1944 Rommel met two german generals at his home. They showed him pretended evidence about his paticipation in “operation valkyrie”, which he denied to be true. They accompanied him away from his home, where he swallowed a capsule filled with potassium cyanide and died. The two generals Wilhelm Burgdorf and Ernst Maisel , members of german court of military honour, who had handed over the capsule to Rommel, drove back to his home and contended that Rommel had died because of ramifications of an injury he received on 17th of July during an allied bombardement.

Given a choice between a trial, involving his disgrace, execution and his family’s impoverishment - and suicide - he chose the latter.

The story given to the public was that he’d died of wounds sustained in the air attack. He was named a “german hero”, was “honoured” with a state funeral an d buried in Herrlingen, Germany.

Had he lived who knows what his real fate might have been at the hands of the Allies. At the main Nuremberg trials, the two army generals prosecuted were Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and General Alfred Jodl. Both were accused of conspiracy to commit crimes against peace; planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression; war crimes; and crimes against humanity. Both were convicted on all four charges and hanged.

The principal charge against Keitel was the infamous 13 May 1941 Barbarossa Decree, which condemned captured prisoners and ensured a high level of brutality by German soldiers against Soviet civilians. Jodl was the author of the Commando decree – ordering that any Allied commandos encountered in Europe and Africa should be killed immediately without trial, even if in proper uniforms or if they attempted to surrender.

General Heinz Guderian is an example of a prominent German general who did survive the war but was not prosecuted for war crimes.

Another prominent example is Field Marshall Kesselring, who had commanded the defence of Italy after the Allies invaded. Kesselring was not prosecuted at Nuremburg, but did face a British military court in Italy. The Moscow declaration of October 1943 had stated that those accused of war crimes would be prosecuted in the country where they had committed their crimes. Although the trial was conducted in Italy, Italian judges did not participate as Italy was not considered an ally. Kesselring was prosecuted for the shooting of hundreds of Italian prisoners in retaliation for attacks on German soldiers. Kesselring was found guilty and condemned to death. British General Alexander, who had run the Italian campaign, and Winston Churchill pleaded for the sentence to be commuted - which it was. Kesselring was released in 1952 and lived until 1970.

By comparison Rommel was never accused of issuing similar decrees. Many felt that he was an honourable soldier. Nor was he ever accused of shooting prisoners in the way Kesselring was. Rommel’s military reputation is that of a highly professional soldier who carried out his duties according to a military code of ethics. His record is untainted by atrocities or unsavoury tactics against the enemy or civilian populations. He tended to live a charmed life early in the war.

Had he lived one can only speculate as to his fate and his legacy. Speculation regarding a possible role for him in the rebuilding of German forces for NATO, had he survived, is unrealistic. Rommel was never a strategically-minded commander. Indeed it is well known that Quartermasters hated him for his habit of outrunning his supplies on the battlefield.

The likelihood is he might well have been allowed to live without any kind of Allied retribution for war crimes as he was never guilty of any such departures from a strict military code of behaviour. But in trial - he would surely would have been put on trial even if he would be found not guilty - the messy details of his involvement with the Nazi regime would come to light. It would show that Rommel certainly benefited from the regime he served, and I think would have been considered guilty by association, even if his enthusiasm for Hitler waned in his final days.

Post-war, it would not have surprised me at all if the Allies had sought to build a West German government around Rommel. Staunchly anti-Communist, he nevertheless was seen widely as honourable and pro-West. But what role he would have been given - or what role the allies might have been able to make palatable to a war ravaged population - can only be speculated.

I suspect he would have served in some official capacity within the Bundeswehr before retiring to write his highly expected memoirs. It’s telling that Rommel’s chief of staff, Hans Speidel, drove the creation of the Bundeswehr and was the first to be named a generaloberst in that force. Later he was Supreme Commander of all NATO ground forces in Central Europe (which was almost all of it). It’s an intriguiing thought what Rommel might have played in a post-war Cold War Germany and Europe. Speidel and Rommel were inseparable and cut from the same bolt of cloth. Indeed it was Hans Speidel, who had been involved in the July 20 plot, wrote after the war that Rommel was a member of the resistance, (for which there is no evidence) that contributed towards Rommel and ‘The Good German’ Myth.

Given all that was “overlooked” by both the Allies and the German people after World War Two. There’s no logical reason to think that Rommel would not have been as honoured, if not more so, after the war. After all, one of the main Bundeswehr barracks continues to be named after him in 1965.

To me he was a great general rightly lauded by his peers and military historians - but not the best. Rommel was a highly competent tactical commander, but there were many such commanders in the Wehrmacht. His prominence is due to a number of things. Firstly, he was always Hitler favourite; secondly Goebbels played him up in his propaganda; and thirdly he fought the British and Americans and thus received much more attention in the Western press and historians after the War than the German commanders fighting the Soviets.

Indeed an argument can be made that by fighting in the Western Desert in a sector that the British had logistical and material superiority (and thus difficult to defeat), Rommel essentially taught the British and the Americans Blitzkrieg tactics - essentially modern warfare. His very inflated legacy saved the British from admitting their military performance in North Africa was abysmal until the Axis forces overextended their supply lines and the American supply of goods was able to compensate for substandard British equipment.

It’s also forgotten that Rommel also oversaw the building of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall which was essentially a fiction when he took over. Immense resources were poured into the project. The impact was to delay the Anglo-Americn invasion about 5 hours and only on one beach (Omaha).

And no matter how humane and honourable he was, Rommel was ultimately a weak man who chose to look away when it was convenient to his career to do so. Indeed I agree with many historians today that he was primarily bent on serving Hitler to advance his career. He was a man who believed he was serving a king and realises too late that he was a devil. I have little doubt that he was conflicted by that especially as it grew during the seven months of his life leading up to his death. Perhaps the best tactical military manoeuvre he made was to take the poison forced upon him and thereby save his family but also secure his legacy, even if that legacy remains mostly intact if a little more tarnished to this day.

#rommel#nazism#nazi#german history#war#second world war#battle#soldier#general#erwin rommel#allies#germany#afrikacorps#statues#culture#society#history#military#military history

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dream Castle by munal43

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sind hier irgendwelche Baden-Württenberger? Ich hab ne Frage, bitte meldet euch

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Last weeks' fun in the dark.. Trying to capture the #perseidmeteorshower in Baden württenberg, Germany from 3.30am 13 August 2019 . . Visit my website... www.rodweyphotography.com . . #meteorshower #skywatch #swabia #stargazing #meteor #nature #astrophotography #pictureoftheday #photooftheday #earthescope #visitgermany #landscapescapture #germanroamers #rodweyphotography #weather #badenwuerttemberg #nightphotography #longexposure #landscapephotography #germany #natgeotravel #lonelyplanet #rodwey2004 #natgeotravelpic #canonuk #earthepix #perseids #deutschland #aroundtheworld . . @perseidmeteorshower_ @germanytourism @stormhour @bbcweather @thephotohour @spacex @spacedotcom @ @beautifuldestinations @earthescope @ig_badenwuerttemberg @thetimes @igersgermany @timeout @passionpassport @citybestviews @superphoto_longexpo @germanroamers (at Baden-Württemberg, Germany) https://www.instagram.com/p/B1b9vL7ANod/?igshid=1f8wgu9imqhg8

#perseidmeteorshower#meteorshower#skywatch#swabia#stargazing#meteor#nature#astrophotography#pictureoftheday#photooftheday#earthescope#visitgermany#landscapescapture#germanroamers#rodweyphotography#weather#badenwuerttemberg#nightphotography#longexposure#landscapephotography#germany#natgeotravel#lonelyplanet#rodwey2004#natgeotravelpic#canonuk#earthepix#perseids#deutschland#aroundtheworld

1 note

·

View note

Text

Baden-Württenberg Derby Freiburg - Stuttgart Welcher Verein hat die bessere Webseite? 📷https://www.klubportal.com/de/

#scf#scfreiburg#vfb#stuttgart#freiburg#dfb#bundesliga#derby#klubportal#sports#basketball#fussball#football#design#rezultati#webdesign

0 notes

Text

We wish we lived in Schwarzwald, Baden-Württenberg

Trekking through the Upper Danube Valley. Baden-Württemberg, Germany 1980

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

AfD wirft Innenminister Unkenntnis über linksextreme Szene vor

JF: „Katastrophales Nichtwissen“: Mit scharfen Worten hat der Stuttgarter Bundestagsabgeordnete Dirk Spaniel (AfD) die Beantwortung einer Anfrage der AfD im baden-württembergischen Landtag durch Innenminister Thomas Strobl (CDU) kritisiert. Es geht um die aggressiven Linksautonomen in der Landeshauptstadt. http://dlvr.it/Pz0YT1

0 notes

Text

Basel, Switzerland: jembatan, sungai Rhine, kota tua, dan tram.

**Mampir kesini karena krn ditempuh dengan murah melalui tiket kereta api provinsi Baden-Württenberg

0 notes

Photo

Beautiful Wine fields are found all across Baden-Württenberg. This time, I stopped in the pretty city of Rüdesheim.

Rüdesheim am Rhein, Germany July, 2017

#Germany#Europe#Mountains#Deutschland#wine#nature#river#blue sky#travel#old city#cityscape#green#clouds#hiking#harvest#walk#town#bundesländer#tb#memories

1 note

·

View note