#Assiniboine River

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Manitoba was incorporated as a province on January 27, 1870.

#Manitoba#province#27 January 1870#155th anniversary#history#Red River#travel#landscape#cityscape#landmark#tourist attraction#summer 2012#Canada#original photography#The Forks Historic Port#Winnipeg#architecture#Esplanade Riel Pedestrian Bridge#Hudson Bay Company#Lower Fort Garry National Historic Site#Lyons Lake#museum#vacation#nature#Assiniboine River#Canada Goose#wildlife#bird#animal#Canadian Museum for Human Rights

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Instructors and other staff at two of Manitoba’s largest colleges have voted in favour of taking strike action.

Manitoba Government and General Employees’ Union (MGEU) members at Red River College Polytech (RRC) and Assiniboine Community College (ACC) gave the union “a strong strike mandate” over three days of voting, the union announced Friday.

“Our members work hard to provide students with the very best education they can, but they have been struggling. Instructors and other support staff at the colleges are amongst the lowest paid in the country. Recruitment and retention is a huge issue,” said MGEU president Kyle Ross in a release.

“It’s unfair for our members and the students. It’s time for our members to catch up and keep up.” [...]

Continue Reading.

Tagging: @politicsofcanada

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Indigenous Poets to Read

Disclaimer: Some of these poems deal with pregnancy, colonialism, substance abuse, murder, death, and historical wrongs. Exercise caution.

Tacey M. Atsitty [Diné] : Anasazi, Lady Birds' Evening Meetings, Things to Do With a Monster.

Billy-Ray Belcourt [Cree] : NDN Homopoetics, If Our Bodies Could Rust, We Would Be Falling Apart, Love is a Moontime Teaching.

CooXooEii Black [Arapaho] : On Mindfulness, Some Notes on Vision, With Scraps We Made Sacred Food.

Trevino L. Brings Plenty [Lakota] : Unpack Poetic, Will, Massacre Song Foundation.

Julian Talamantez Brolaski [Apache] : Nobaude, murder on the gowanus, What To Say Upon Being Asked To Be Friends.

Gladys Cardiff [Cherokee] : Combing, Prayer to Fix The Affections, To Frighten a Storm.

Freddy Chicangana [Yanacuna] : Of Rivers, Footprints, We Still Have Life on This Earth.

Laura Da' [Shawnee] : Bead Workers, The Meadow Views: Sword and Symbolic History, A Mighty Pulverizing Machine.

Natalie Diaz [Mojave] : It Was The Animals, My Brother My Wound, The Facts of Art.

Heid E. Erdrich [Anishinaabe] : De'an, Elemental Conception, Ghost Prisoner.

Jennifer Elise Foerster [Mvskoke] : From "Coosa", Leaving Tulsa, The Other Side.

Eric Gansworth [Onondaga] : Bee, Eel, A Half-Life of Cardio-Pulmonary Function.

Joy Harjo [Muscogee] : An American Sunrise, Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings, A Map to The Next World.

Gordon Henry Jr. [Anishinaabe] : How Soon, On the Verve of Verbs, It Was Snowing on The Monuments.

Sy Hoahwah [Comanche/Arapaho] : Colors of The Comanche Nation Flag, Definitive Bright Morning, Typhoni.

LeAnne Howe [Choctaw] : A Duck's Tune, 1918, Iva Describes Her Deathbed.

Hugo Jamioy [Kamentsá] : PUNCTUAL, If You Don't Eat Anything, The Story of My People.

Layli Long Soldier [Lakota] : 38, WHEREAS, Obligations 2.

Janet McAdams [Muscogee] : Flood, The Hands of The Taino, Hunters, Gatherers.

Brandy Nālani McDougall [Kānaka Maoli] : He Mele Aloha no ka Niu, On Finding my Father's First Essay, The Island on Which I Love You.

dg nanouk okpik [Inupiaq-Inuit] : Cell Block on Chena River, Found, If Oil Is Drilled In Bristol Bay.

Simon J. Ortiz [Acoma Pueblo] : Becoming Human, Blind Curse, Busted Boy.

Sara Marie Ortiz [Acoma Pueblo] : Iyáani (Spirit, Breath, Life), Language (part of a compilation), Rush.

Alan Pelaez Lopez [Zapotec] : the afterlife of illegality, A Daily Prayer, Zapotec Crossers.

Tommy Pico [Kumeyaay] : From "Feed", from Junk, You Can't be an NDN Person in Today's World.

Craig Santos Perez [Chamorro] : (First Trimester), from Lisiensan Ga'lago, from "understory".

Cedar Sigo [Suquamish] : Cold Valley, Expensive Magic, Secrets of The Inner Mind.

M. L. Smoker [Assiniboine/Sioux] : Crosscurrent, Heart Butte, Montana, Another Attempt at Rescue.

Laura Tohe [Diné] : For Kathryn, Female Rain, Returning.

Gwen Nell Westerman [Cherokee/Dakota] : Dakota Homecoming, Covalent Bonds, Undivided Interest.

Karenne Wood [Monacan] : Apologies, Abracadabra, an Abecedarian, Chief Totopotamoi, 1654.

Lightning Round! Writers with poetry available on their sites:

Shonda Buchanan [Coharie, Cherokee, Choctaw].

Leonel Lienlaf [Mapuche].

Asani Charles [Choctaw/Chickasaw].

#first nations poetry#indigenous poetry#native american poetry#first nations literature#indigenous literature#poetry#all my relations#long post#nagamon

803 notes

·

View notes

Text

Telegram from Commander Alfred H. Terry to the Adjutant General of the Division of the Missouri

Record Group 393: Records of U.S. Army Continental CommandsSeries: Special Files of Letters ReceivedFile Unit: Sioux Indian Papers, 1879 - Brief and Letters Received 3721 (with enclosures to 3571) Thru 5219

[pre-printed form]

The Western Union Telegraph Company.

The rules of this company require that all messages received for transmission shall be written on the message blanks of the Company.

under and subject to the conditions printed thereon, which conditions have been agreed to by the sender of the following message.

A.R.Brewer, Secretary. William Orton, Prest.

No. [handwritten] 242 [/handwritten]

[handwritten at top of page] [illegible] / 36/ 29P [/[

[handwritten at right] 123 [ppw?] [/]

Dated [handwritten] At Paul/Minn/23 [/handwritten]

To [handwritten] Adjutant Gent Division [/handwritten]

Rec'd at cor. Lasalle and Washington Sts.,

Chicago, Ills. [handwritten] July 23, 1879 [/handwritten]

[handwritten] Missouri Chicago

On the seventeenth June the advance of [Mibs?] Column

under Lieutenant Clark second cavalry composed of

Lieutenant Bordens Company fifth infantry Lieutenant

Hoppins company second cavalry and fifty Indian scouts

had a sharp engagement between Beaver Creek + Mouth of

frenchmans Creek with four hundred Hostile Indians the

indians were pursued twelve miles when the troops in

advance became surrounded [illegible letters stricken through] Main Command was moved

forward rapidly + the Enemy fled North of Milk river

Colonel Miles reports that the troops engaged fought in

admirable order + are entitled to much credit that the action

of our Indians was quite satisfactory Cheyennes, Sioux,

Crows, Assiniboines and Bannacks fighting with the troops

Killing several Hostile Indians + forcing the enemy to

abandon a large amount of property. Our casualties are

two men Company Second Cavalry wounded two Cheyenne

and one Crow Indian Scouts killed and one Assiniboine

scout seriously wounded. A large scouting party sent

upon North side of Milk river near Head of

Porcupine reports to Colonel Miles that main

camp under Sitting Bull composed of sixteen

hundred lodges is on little rocky having moved over

from Frenchmans Creek Colonel Miles says this

report is corroborated by several others + by men

who were in the Hostile Camp as late as June Sixteenth

+ that he expects to move up between frenchmans Creek +

the Little Rocky where possibly the Main body of

Indians may be engaged

Terry Department Commander

246 paid Govt Rate

# 532

[stamped] RECEIVED

[stamped] JUL

[stamped] [2?] 23

[stamped] 1879

[stamped] MIL.DIV.,MO.

#245

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Floating ice on the Assiniboine River, taken sometime between 1903 and 1906 by Fred Landen, an English immigrant. Photo via the Winnipeg Archives

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bison calves stand in Saskatchewan’s Wanuskewin Heritage Park, the first to be born in the the Archaeological Site and Cultural Centre in more than 150 years. Photo By WanuskewinHeritage Park

How Canadian Bison Have Been Brought Back From The Brink In Saskatchewan

In Saskatchewan’s Wanuskewin Heritage Park, bison are a vital piece of the indigenous cultural history and have been brought back from the brink to help rewild fragile grasslands.

— By Karen Gardiner | Published June 3, 2023 | July 29th, 2025

Dr. Ernie Walker has heard enough tired takes on Saskatchewan’s flat landscape. “A lot of people refer to the prairies as big and empty or useless,” he says, indignant, as he leads me around Wanuskewin Heritage Park, an archaeological site and cultural centre 15 minutes from the Saskatchewan city of Saskatoon. “That’s not it. What’s significant about the prairies is that it’s subtle.”

Standing under a big blue sky, amid dry rolling grassland that stretches uninterrupted all the way to the horizon, I think I understand the misconception: lacking mountains and with sparse trees, this isn’t exactly the type of landscape that wallops you with its dramatic features. But if there’s anyone who can convincingly argue for the value of this place, it’s Walker.

The park’s founder and chief archeologist, Walker has spent four decades with his hands in Wanuskewin’s dirt, turning up artefacts — including stone and bone tools, amulets and even gaming pieces — that have whispered to him stories of this land’s significance. Working here as a ranch hand in the early 1980s, he convinced his boss that the land had great archaeological importance. That slowly set in motion the park’s establishment, which involved a rare-for-the-time collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

“When visitors look at the landscape, I’m always interested in what they’re actually seeing,” Walker continues. “They need to know the story behind this place.” The story here is of 6,000 years of almost uninterrupted human occupation. That narrative was drummed into the land by millions of bison hooves until the animals met a violent end. But now, the bison are back and they’re writing a new chapter.

An abandoned building stands along the roads of rural Saskatchewan. Photo By Design Pics Inc, Alamy

A Place of Sanctuary

In the Nēhiyawēwin (Plains Cree) language, ‘Wanuskewin’ roughly translates as ‘sanctuary’. Lying at the fertile confluence of the South Saskatchewan River and Opimihaw Creek, it was a gathering place for the people of the Northern Plains — the Blackfoot, Cree, Ojibwa, Assiniboine, Nakota and Dakota — who all followed bison herds and found sustenance and shelter here. Before European settlement, this land was home to vast numbers of bison (also known as buffalo) and the multitudes of species they supported, from the insects that thrived in the bison’s manure and the birds that fed on those insects to the humans that were dependent on the bison’s meat and skin.

But then came catastrophe. Bison were deliberately slaughtered to near extinction, a tactic used by settlers to starve Indigenous people into submission. “Around 400 years ago, there were 26 to 30 million bison on the Great Plains in North America,” Walker says. “By the 1890s, there were just 1,200.”

With the bison and their way of life gone, Plains people were left with little choice but to sign Treaty Six, an 1876 agreement with the British Crown that opened up the land for European settlement and promised one square mile of land to every Indigenous family of five. They were then corralled onto reserves.

“What if I were to come to all of your houses, empty your fridges and say you guys have to move to the s****y part of town?” Wearing a fringed buckskin waistcoat adorned with beaded flowers, Jordan Daniels, a member of the Mistawasis Nêhiyawak (Cree) Nation, raises his voice above the prairie wind to ensure we understand the depth of his ancestors’ loss. I’ve left Walker for now and joined a small group along Wanuskewin’s bison viewing trail where we’ll see and learn about Wanuskewin’s reestablished herd.

“The bison were a central part of our existence,” Daniels explains. “We made our teepees out of them. They were a main food source. Everything we needed for sustenance came from these animals.” There was also an emotional connection. Many Indigenous people consider bison kin, and the animal is ubiquitous in Indigenous stories and art. “They played a central role in our beliefs and in our way of seeing the world around us,” explains Daniels.

Bringing back the bison to Wanuskewin was always the park’s founders’ dream. In 2019, the animals finally came home. Six calves from Saskatchewan’s Grasslands National Park established the herd, followed by an additional five animals from the United States with ancestral ties to Yellowstone National Park. The herd, which has grown to 12, is now helping to restore native grasses. North America’s grasslands are one of the most endangered biomes in the world and bison, a keystone species, can help restore balance between animals, land and humans.

While grazing, Daniels explains, bison’s hooves aerate soil and help to disperse seeds, and by wallowing (rolling around), they create depressions that fill with rainwater and stimulate plant growth and provide habitat for microorganisms, amphibians and insects. “They’re ecologically unmatched,” he says. “But, I feel, nothing outweighs the cultural factor of having bison back here.”

Daniels’ connection is intensely personal. He explains that his seven-times great grandfather was Chief Mistawasis, the first chief in Saskatchewan to sign on to Treaty Six. Before signing, Daniels says, Mistawasis “had spent his life living how our people have done since time immemorial, out on the plains hunting bison. And today, I’m able to look at animals that are genetically close to the ones that he’d have interacted with. It’s a very impactful and powerful thing.”

Tianna McCabe, a Navajo, Arapaho and Cree powwow dancer, explains the significance of her ornate regalia. Photo By Concepts/KareeDavidsonPhotography.Com

Happy To Be Home

Wanuskewin is about protecting the future as much as preserving the past. I meet with young Indigenous people who demonstrate aspects of their cultures, once suppressed, now thriving. Tianna McCabe, a Navajo, Arapaho and Cree powwow dancer, explains the significance of every fabric and colour of her ornate regalia before hopping her way through an Old Style Fancy Shawl dance, her feet landing with each staccato beat of a drum.

As the day eases into night, I follow a group to the top of a bluff to meet Métis chef Jenni Lessard, who’s prepared our Han Wi (‘moon dinner’ in Dakota language). As well as bison tenderloin, sourced from a nearby farm and seasoned with yarrow and sage, we eat pickled spruce tips and bannock bread with chokecherry syrup. Sipping wild mint and fireweed tea, we gather around a fire, rejoined by Dr Ernie Walker to hear “a miraculous story”.

Dezaray Wapass, a Fancy Shawl dancer, performs in Wanuskewin National Park. Photo By Concets/KareeDavidsonPhotography.Com

In August 2020, Walker was visiting the bison herd when he noticed a boulder protruding from a patch of vegetation the animals had worn away. Seeing a groove cut across the top of it and, brushing away the dirt, he spotted more cuts and realised what he was seeing was a petroglyph. The boulder turned out to be a ‘ribstone’, so-called because its engraved motifs represent bison ribs. Three more petroglyphs were later unearthed, as well as the stone knife used to carve them.

What the bison did when they uncovered those petroglyphs was to complete the story of Wanuskewin. “We’d always lamented that, here in the park, we’ve got [archeological sites like] buffalo jumps, teepee rings and North America’s most northerly medicine wheel, but we didn’t have any rock art,” explains Walker.

Wanuskewin is on the tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage designation. The discovery of the petroglyphs, Walker believes, has boosted its chances. He tells me: “The stones complete everything you’d expect to find on the Northern Plains, but you don’t usually find those things within walking distance of each other.”

Dressed in a white Stetson, blue jeans and cowboy boots, Walker retains the appearance of a young ranch hand but, after 40 years of arguing for this place, I sense he’s content to rest a little. “I’ve told this story many times before,” he says. Now, the bison have picked up Wanuskewin’s epic story and it’s time to let them tell it once again.

#Canadian Bison#Saskatchewan#Wanuskewin Heritage Park#Archaeological Site and Cultural Centre#Dr. Ernie Walker#Chief Archeologist#Nēhiyawēwin (Plains Cree) Language#Wanuskewin (Sanctuary)#Blackfoot Cree Ojibwa Assiniboine Nakota and Dakota#Jordan Daniels#Mistawasis Nêhiyawak (Cree) Nation#Indigenous People#Grasslands National Park#Tianna McCabe a Navajo Arapaho and Cree Powwow Dancer 💃#Old Style Fancy Shawl Dance 💃#Métis chef Jenni Lessard#Han Wi (‘Moon Dinner’ in Dakota Language)#Chokecherry Syrup#Petroglyphs#UNESCO World Heritage

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

in light of recent events... who are some of your favorite underused indigenous faces?

I think it'd be better to ask Indigenous creators some of their suggestions (if they're accepting asks!) but I will list people I know of with resources at the time of posting so the roleplay community knows who has them since the main directory is down. I know some of these are well known but I hardly see anybody use them:

Gil Birmingham (1953) Comanche.

Ernie Dingo (1956) Yamatji.

Benjamin Bratt (1963) Peruvian of Quechua descent / German, English, Sudeten German.

Zahn McClarnon (1966) Irish, Polish, Hunkpapa Lakota and Sihasapa Lakota.

Jason Scott Lee (1966) Kānaka Maoli and Chinese.

Kimberly Guerrero (1967) Colville, Ktunaxa, Bitterroot Salish, and Cherokee.

Michael Greyeyes (1967) Plains Cree.

Aaron Pedersen (1970) Arrernte and Arabana.

Robbie Magasiva (1972) Samoan.

Kaliko Kauahi (1974) Kānaka Maoli and Japanese,

Jennifer Podemski (1974) Saulteaux, Ojibwe, Lenape, Metis, and Polish Jewish - has Chronic Lyme Disease.

Chaske Spencer (1975) Yankton, Assiniboine, Sisseton, Nez Perce, Cherokee, Creek, French, and Dutch.

Simone Kessell (1975) Ngāti Tūwharetoa and Ngāi Te Rangi.

Tawny Cypress (1976) African-American, Accawmacke / Hungarian, German - is queer.

Daniella Alonso (1978) Peruvian of Quechua descent, Japanese / Puerto Rican.

Jesse Williams (1980) African-American, Seminole / Swedish.

Marisa Quinn (1980) Mexican and Lipan Apache.

Meagan Good (1981) African-American, Afro-Barbadian, Puerto Rican, Cherokee, Creole, and Jewish.

Jennifer Pudavick (1982) Metis.

Gabriel Luna (1982) Mexican and Lipan.

Rudy Youngblood (1982) Comanche and Yaqui.

Heather White (1983) Mohawk / Nakoda Sioux.

Cara Gee (1983) Ojibwe.

Andrew M. Gray (1983) Spanish / Miwok.

Uli Latukefu (1983) Tongan.

Alex Meraz (1984) Mexican of Purepecha descent.

Jessica Matten (1985) Red River Metis of Cree and Saulteaux descent, Chinese, French, British, and Ukrainian.

Martin Sensmeier (1985) Tlingit, Koyukon, Eyak, Irish, and German.

Cooper Andrews (1985) Samoan / Hungarian Jewish.

Elle Maija Tailfeathers (1985) Kainai Blackfoot and Northern Sami.

Nathalie Kelley (1985) Argentinian, Quechua of Peruvian descent.

Maika Harper (1986) Inuit.

Miranda Tapsell (1987) Larrakia.

Oona Chaplin (1986) Chilean [Mapuche, Spanish, evidently Romanian] / English, Irish, 1/16th Scottish.

Lily Gladstone (1986) Amskapi Pikuni Blackfoot, Kainai Blackfoot, and Nez Perce.

Jenna Talackova (1988) Babine and Czech.

Joan Smalls (1988) Afro-Virgin Islander, Irish / Puerto Rican [Spanish, Taino, Indian].

Ashley Callingbull (1989) Cree.

Ellyn Jade / Jade Willoughby (1990) Ojibwe, Afro Jamaican, Taíno, British - is Two-Spirit (she/her) - not straight otherwise unspecified, has nephrotic syndrome and celiac’s disease.

Kiowa Gordon (1990) Hualapai, English, Scottish, Danish, Manx.

Mary Galloway (1990) Quamichan - is queer.

Keisha Castle-Hughes (1990) Tainui, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Porou / English.

Tanaya Beatty (1991) Da’naxda’xw and Himalayan.

Richard Harmon (1991) Mi'kmaq, French, Italian, English.

Cody Kearsley (1991) Metis.

Grace Dove (1991) Secwepemc.

Rose Matafeo (1992) Samoan / Scottish and Croatian.

Yalitza Aparicio (1993) Mixtec and Triqui.

Bryana Holly (1993) Kānaka Maoli, Japanese, Slovenian, Russian.

Ashley Moore (1993) African-American, Cherokee, and White.

Luciane Buchanan (1993) Tongan / Scottish.

Kawennáhere Devery Jacobs (1993) Mohawk - is queer.

Frankie Adams (1994) Samoan.

Taija Kerr (1994) Kānaka Maoli and African-American.

Khadijha Red Thunder (1994) Chippewa Cree, African-American, Spanish - is pansexual.

Angel Bismark Curiel (1995) Taino, Afro Dominican, Spanish - has asthma and a heart murmur.

Kehlani (1995) African-American, French, Blackfoot, Cheroke, Spanish, Mexican, Filipino, Scottish, English, German, Scots-Irish/Northern Irish, and Welsh, as well as distant Cornish, Irish, and possibly Choctaw - is a non-binary womxn and is a lesbian.

Sasha Lane (1995) African-American, Māori, English, Scottish, Sorbian, French, Cornish, distant German, Italian, Belgian Flemish, Russian, and Northern Irish - is gay and has schizoaffective disorder.

Cody Christian (1995) Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, French / English.

Chase Sui Wonders (1996) Tahitian, Chinese, Japanese, and Unknown White.

Courtney Eaton (1996) Chinese, Māori Cook Islander / English.

Román Zaragoza (1996) Akimel O’odham, Mexican / Japanese, Taiwanese.

Keahu Kahuanui (1996) Kānaka Maoli as well as some Japanese, likely small amounts of Scottish and French.

Court

Alex Aiono (1996) Ngāti Porou and Samoan / English, German, Irish, Danish, smaller amounts of Welsh, Swiss-German, and Scottish.

Madeleine Madden (1997) Gadigal, Eastern Arrernte, Kalkadoon and White.

Alaqua Cox (1997) Menominee and Mohican - is Deaf and is a leg amputee.

Kaiit (1997) Papuan, Gunditjmara, Torres Strait Islander - non-binary - she/he/they.

Morgan Holmstrom (1997) Metis of Cree descent, Ilocano Filipino, and Sambal Filipino.

Sofia Jamora (1997) Kānaka Maoli and Mexican.

Amber Midthunder (1997) Hunkpapa Lakota, Hudeshabina Nakoda, Sissiton-Wahpehton Dakota, Thai-Chinese, and White.

Froy Gutierrez (1998) Mexican and Caxcan / European.

Forrest Goodluck (1998) Navajo / Hidatsa, Mandan, Tsimshian, one-eighth Japanese, Norwegian, English, French-Canadian, German.

Kekoa Kekumano (1998) Kānaka Maoli.

Shina Novalinga (1998) Inuit.

Sivan Alyra Rose (1999) Chiricahua Apache / Afro-Puerto Rican, Creole - is genderfluid (she/they) and pansexual.

Erana James (1999) Ngāti Whātua-o-Ōrākei, Tainui.

Lizeth Selene (1999) Black and Unspecified Indigenous Mexican.

Willow Allen (1999) Inuit.

Anna Lambe (2000) Inuit - is bisexual.

Auli'i Cravalho (2000) Puerto Rican, Kānaka Maoli, Native Hawaiian, Portuguese, Chinese, Irish - is bisexual.

Joshua Odjick (2000/2001) Algonquin, Cree, and possibly Ojiwbe.

D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai (2001) Ojibwe, Cree, Chinese Guyanese, Afro Guyanese, White.

Matthew Sato (2001) Japanese, Chinese, Kānaka Maoli, Norwegian, Azorean Portuguese, English, Irish, Scottish, German.

Quannah Chasinghorse (2002) Hän, Gwich’in, Sicangu Oyate Lakota Sioux, and Oglala Lakota Sioux.

Jimmy Blais (?) Plains Cree.

Meegwun Fairbrother (?) Ojibwe, Scottish.

Ryan-James Hatanaka (?) Metis, Japanese, Scottish / Irish.

Delno Ebie (?) Lenape, Ojibwe, Cherokee, Mohawk, Montaukett, Powhatan, Pequot, Narragansett, Italian [including Sicilian], Greek, and possibly other descent.

Taiana Tully (?) Kānaka Maoli.

Lindsay Watson (?) Kānaka Maoli.

+ please let me know if I'm missing anyone or worded things wrong!

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

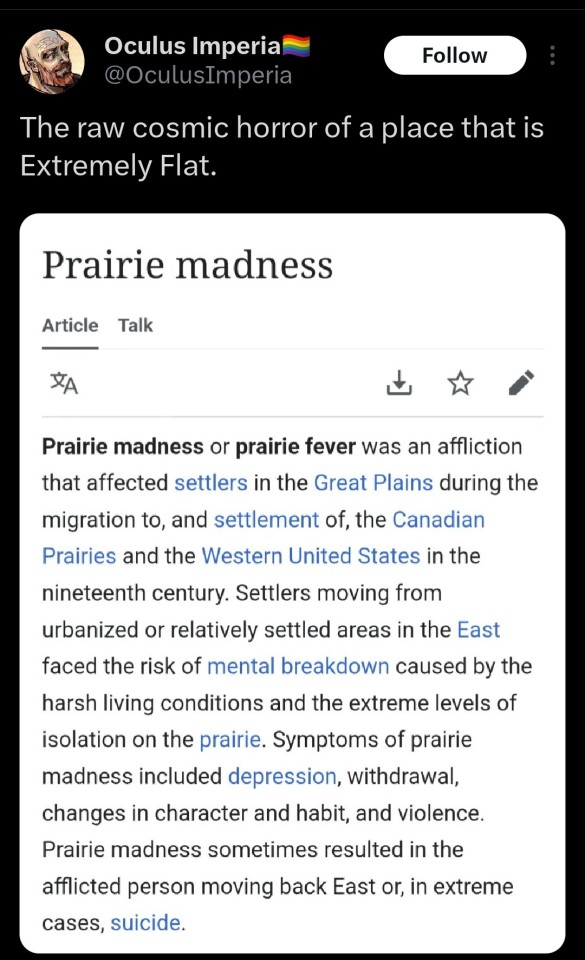

Adding on to this. I'm someone from good old MB, Canada, which means I have lived my whole life surrounded by plains, yet at the same time, about a 8 min drive from a small mountain that loomed over the town I lived in. Also to this, here when you look out to the wide open plains, you'll often see another batch of trees off in the distance, meaning you never get that overwhelming sense of fear that comes from wide open spaces. And by small patch what I actually mean is multiple batches of trees slowly but surely building in multitudes till you are driving through a forest the further North you go, and even to south you're likely to encounter a small hilly area or even the Assiniboine river valley. Ever city/town is swamped with trees (to the point in some cases you feel like you're living in a forest), and the landscape is consistently broken by just how many lakes we have here. So in other words, despite traveling through places like the Rockies or the plains of the US, I have never had this fear because I lived in a place that basically had everything in mini form, bar the forests, cause good lord.

58K notes

·

View notes

Text

Manitoba became a province of Canada on July 15, 1870.

#Manitoba#province of Canada#Lower Fort Garry National Historic Site of Canada#The Forks#Assiniboine River#Lyons Lake#Esplanade Riel Pedestrian Bridge#Red River#summer 2012#Canada#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#cityscape#architecture#landscape#countryside#Trans-Canada Highway#Winnipeg#prairie#15 July 1870#anniversary#Canadian history

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A nature reserve on the banks of the Assiniboine River near Brandon, Man. will soon be a site for conservation, learning and healing.

Wabano Aki, which means tomorrow’s land in Anishinaabe, will be used for agriculture, conservation, cultural and spiritual purposes by Indigenous communities in partnership with the Nature Conservancy of Canada.

The 305-hectare area of land, previously known as Waggle Springs, was officially renamed on Sept. 28.

Christine Chilton, community relations manager at the Manitoba chapter of the conservancy, said the site acts as a classroom, but the partnership helps the land to take on a new meaning.

“We often approach things from a Western science perspective. And we’re realizing that it’s actually really important to take in a whole of society approach, which means that there’s a lot of different ways of knowing, and there’s a lot of different uses of land that can all work together to make a better tomorrow,” Chilton said. [...]

Continue Reading.

Tagging: @politicsofcanada

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 Ways to Embrace the Magic of Winnipeg Winters ❄️

Winnipeg’s winters are more than just cold—they’re an experience. From snow-draped landscapes to cozy indoor escapes, here’s how you can make this frosty season unforgettable.

1. Take a Winter Walk Through Assiniboine Park

Bundle up and head to Assiniboine Park to see snow-covered trees and frozen ponds. The quiet stillness of the park in winter feels like stepping into a postcard. Pro tip: Bring a thermos of hot cocoa to sip along the way!

2. Skate the River Trail

Did you know Winnipeg boasts one of the longest natural skating trails in the world? The Red and Assiniboine Rivers turn into a stunning icy pathway every winter. Lace up your skates and experience the city from a whole new perspective. Check out The Forks for trail updates and rentals.

3. Snap Frosty Photos

Winter light in Winnipeg is pure magic. Sunrise and sunset cast golden hues over snowy streets, while frost-covered branches make for stunning close-ups.

"A stunning Winnipeg sunset casts a warm glow over the frozen Red River, blending vibrant hues with the serenity of winter."

Share your photos using #snowinthepeg to connect with the community.

4. Go Ice Fishing on Lake Winnipeg

Experience the thrill of ice fishing on one of Manitoba’s most iconic lakes. Gather your gear, set up a cozy shack, and enjoy the peacefulness of waiting for the catch of the day.

Don’t forget to dress warmly and bring snacks! For guides and tips, check out Manitoba Ice Fishing.

5. Cozy Up Indoors

Not every adventure has to be outdoors. Winnipeg winters are also perfect for cozy moments:

Sip on homemade hot cocoa while reading by the fire.

Try a winter craft like knitting or baking cookies.

6. Visit a Local Festival

Festival du Voyageur is a must-see winter event! Celebrate the season with music, food, ice sculptures, and cultural experiences that capture the heart of Manitoba.

"Intricate snow sculptures at Festival du Voyageur showcase the creativity and culture of Winnipeg winters."

What’s your favourite way to enjoy Winnipeg winters? Share in the comments or tag me in your own adventures!

Stay warm, Snowinthepeg

#winnipeg#winnipeg manitoba#canada#winter#snow#snowflakes#winter wonderland#pine trees#snowman#ice#cold#fishing#ice hockey

0 notes

Text

"...in 1884, the DIA [Department of Indian Affairs] announced that it would be opening new boarding and industrial schools in British Columbia. In the early 1880s, only seven federally funded mission schools were operating in the province, including boarding schools at Metlakatla, Port Simpson, Yale, Chilliwack, and Mission, with a total enrolment of 544 students, 322 boys and 222 girls. In the opinion of local DIA officials, Metlakatla was the most desirable spot for an industrial school because it already had the necessary infrastructure. It was also the epicentre of growing Indigenous resistance on the Northwest Coast.

Though the conflict at Metlakatla in 1882, tensions persisted in the community and surrounding area. Indigenous Peoples were frustrated at the failure of government to prevent further settler encroachment on their lands. In response, Ts’msyan and Nisga’a citizens created new political organizations to fight back and assert their sovereignty. In fact, DIA officials who wanted to open new schools on the Northwest Coast often heard complaints from parents, including, “what we want from the Government is our land, and not schools.” Moreover, news of the 1885 war between Canada and the Métis and allied Cree, Assiniboine, and Saulteaux communities made its way over the Rocky Mountains. W.H. Lomas, the Cowichan Indian agent, confirmed the growing danger:

Rumours of the Metlakatla land troubles and of the North-West rebellion have been talked over at all their little feasts, and not often with credit to the white man.

Lomas warned that the provincial government’s disregard for Indigenous Peoples was tantamount to playing with fire and that action should be taken immediately to dissuade further dissent and prevent a general uprising. The “smouldering volcano” of Indigenous-settler relations once again threatened to erupt. Settler fears about Indigenous resistance, as Ned Blackhawk argues, directly inform colonial policy. In this context, and with Duncan out of the picture and Bishop Ridley in charge, the Metlakatla school was retroftted to become the province ’s first official industrial school.

John R. Scott, who had taught in Australian schools for Indigenous children, was chosen as its first principal. When he reported for duty in 1888, he found its condition unsatisfactory. There was no furniture to accommodate the pupils. After securing proper lodgings, Scott toured neighbouring communities to convince Indigenous parents to send their children to the school. He travelled to Fort Simpson and Kincolith and also visited a number of fishing camps along the Nass River. Of his journey, he wrote:

At these places I called at nearly all the huts and houses, and wherever I saw any children I explained to their parents the objects of the school and the provision made by the Government for educating Indian boys.

Some parents were interested, but Scott’s efforts were mostly met with indifference. Unfazed, he took in four boys, and two more pupils followed shortly thereafter. On May 13, 1889, he officially opened the Metlakatla school with just six students. By the end of the year, fifteen boys, four Nisga’a, eight Ts’msyan, and three Haida, were attending. Ottawa soon deemed the Metlakatla experiment a success and began preparations for new schools in the province. As in the colonial period, Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Catholic missionaries competed over newly available federal funds. Given the widely known difficulties with mission day schools, Powell proposed that boarding and industrial schools be established in strategic locations throughout the province as “the more desirable and advantageous course.” Considerable debate ensued among the churches and the DIA about the number and most suitable locations for such schools, with Powell and Indian agents relentlessly lobbying the DIA. In the end, three schools were established in 1890: Kamloops in the interior, Kuper Island, of the east coast of Vancouver Island, and Cranbrook in the southeastern mainland. Allocated per-capita grants of $130 per annum per pupil based on annual attendance, all three were run by Catholic missionaries and staffed by the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. All three were also situated in areas with significant Indigenous opposition to colonization.

In the late 1870s, Kamloops was identified as a hotbed of discontent over the provincial government’s land policy. In the summer of 1877, when two reserve commissioners arrived to investigate Secwépemc complaints, they quickly received of an alarmed telegram to the Indian Branch in Ottawa: “Indian situation very grave from Kamloops to American border – general dissatisfaction – outbreak possible.” Kuper Island and the parts of Vancouver Island that were located in the Cowichan Indian Agency also had a reputation for resistance. Most notably, Indigenous Nations were angry over the state’s attack on the potlatch, a ceremony and important economic gathering that Ottawa outlawed via an 1884 amendment to the Indian Act. In the late 1880s, the Kootenay region was also seen as troublesome. In 1887, provincial reserve commissioner Peter O’Reilly, Trutch’s brother-in-law, laid out reserves in the Cranbrook area in an unsatisfactory way, and Ktunaxa citizens, particularly Chief Isadore, were dissatisfied.

A detachment of the newly formed North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) under the command of Sam Steele was sent out from nearby Lethbridge, Alberta, as a show of force to deter further conflict. As tensions eased and the police were redeployed, the barracks that had been built for them were updated “for industrial school purposes in the interests of the Indian children.” The fact that Indigenous children were to be institutionalized in an old NWMP barracks established to check the power of their parents confirms that the structures of settler colonialism in British Columbia developed in the shadow of colonial conflict over the land, as Blackhawk shows was the case in the American West. Indeed, the principal of the Kootenay Indian Industrial School, Nicolas Coccola, acknowledged that when the school opened in 1890, the Ktunaxa were “on the eve of breaking out into war with the whites.” State schooling thus emerged in what Blackhawk calls the “maelstrom of colonialism.” The new school system was tiered, and the funding available to schools depended on their rank and utility to the DIA. At the bottom of the hierarchy were the Indian Day Schools. Given their high rates of irregular attendance and inability to separate children from their parents and communities, they were seen as inefficient but still necessary stop-gaps. Thus, most day schools received only a few hundred dollars of federal funding, barely enough to cover a teacher’s annual salary. Paying the remaining costs was left to the churches. Nevertheless, by 1890, ten were in operation, mostly on the coast, at Alert Bay, Bella Bella, Clayoquot, Cowichan, Hazelton, Kincolith, Lakalsap, Masset, Nanaimo, and Port Essington. By 1900, their number had jumped to twenty-eight in all parts of the province. Securing regular attendance remained an issue, however. In 1884, Harry Guillod, the Indian agent for the West Coast Agency, informed the DIA of a disturbing incident:

Rev. Father Nicolaye has had trouble with the Indians. He, as a punishment, shut up two pupils for non-attendance at school, and some sixty of the tribe made forcible entry into his house, and three of them held him while others released the boys … It is very uphill work trying to get the children to attend school, as the parents are indifferent, and are away with them at other stations for months during the year.

Far from being agnostic about schooling, Indigenous parents organized against the teacher and advocated for education on their terms. Gwichyà Gwich’in historian Crystal Gail Fraser notes that Indigenous parents often “understood the implications” of Indian education “while demonstrating their awareness that their complicity within the system did not equate to unqualified approval.” Parents and guardians actively negotiated their circumstances and “proved remarkably successful in their capacity to transform, to greater and lesser degrees, emerging state structures and policies around schooling.” Still, such activity convinced the DIA that boarding and industrial schools were necessary to separate children from their parents and communities to facilitate re-education and assimilation.

Indian Boarding Schools, originally designed for younger children and located on or near Indian reserves, were a step above day schools in the DIA ranking. According to state officials, they had the advantage of being able to house children and establish some distance from parents for much of the year to disrupt Indigenous lifeways. Indeed, Métis historian Allyson D. Stevenson argues that “disruption and dispossession figure prominently in the colonization of Indigenous kinship.” Their per-capita grant was usually in the range of sixty to eighty dollars, and some also received free or cheap land grants to open new facilities. In 1890, boarding schools were operating at Coqualeetza, Port Simpson, Mission, and Yale. The All Hallows Boarding School at Yale originally accepted Indigenous and white pupils, the latter mostly the daughters of Anglican families in the Diocese of New Westminster who were unhappy with the non-denominational public school system being implemented across the province. As Jean Barman writes, All Hallows was unique in that it was both a boarding school for Indigenous girls, complete with DIA funding, and a private Anglican school for white pupils who paid fees. By 1900, there were seven boarding schools, with new institutions being established or recognized by the DIA at Alberni, Alert Bay, and North Vancouver. Most incarcerated Indigenous children from many different Nations from across the province.

The highest rank in the new system was reserved for the Indian Industrial Schools. The first schools were mostly paid for by the federal government, but an Order-in-Council of 1892 shifted substantial costs back to the churches. Missionaries were now expected to operate the institutions on per-capita grants that were below the then-current level of expenditure, usually $130. The government assumed that teaching would be done on a volunteer basis or would be covered by churches. The inadequate funding simply exacerbated existing problems. Nevertheless, by 1900 new industrial schools at Alert Bay, Coqualeetza (which was upgraded to an industrial school), and Williams Lake joined Metlakatla, Kuper Island, Kamloops, and Kootenay. Within twenty years, the number of Indigenous children attending federally funded schools of all kinds – day, boarding, and industrial – had doubled, reaching a total of 1,568 by 1900."

- Sean Carleton, Lessons in Legitimacy: Colonialism, Capitalism, and the Rise of State Schooling in British Columbia. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 2022. p. 121-126.

#british columbia history#indian residential schools#kamloops#metlakatla#settler colonialism#public schooling#missionary schools#nineteenth century canada#history of education#settler colonialism in canada#day schools#indigenous people#indigenous resistance#indigenous history#first nations#academic quote#reading 2024#lessons in legitimacy

0 notes

Text

Exploring Tuxedo, Winnipeg: Homes for Sale and Waterfront Properties

Nestled in the serene and prestigious neighborhood of Tuxedo, Winnipeg lays a community renowned for its blend of elegance, natural beauty, and modern conveniences. Tuxedo appeals to discerning homebuyers seeking luxurious residences and serene waterfront properties within a tranquil urban setting.

Tuxedo Winnipeg Homes for Sale are highly sought-after for their upscale appeal and prime location in the heart of Winnipeg. The neighborhood boasts a variety of architectural styles, from classic Tudor homes to sleek, contemporary designs, ensuring there's a home to suit every taste and preference. Whether you're looking for a sprawling estate nestled amidst lush greenery or a sophisticated townhouse with modern amenities, Tuxedo offers an array of options to accommodate different lifestyles.

In addition to its residential charm, Tuxedo also features stunning Waterfront Property For Sale Winnipeg. These properties overlook serene lakes and rivers, providing homeowners with picturesque views and a peaceful retreat from city life. Living in a waterfront home in Tuxedo offers not only natural beauty but also the opportunity to enjoy recreational activities such as boating, fishing, and relaxing by the water's edge.

One of the defining characteristics of Tuxedo is its proximity to essential amenities and recreational opportunities. Residents benefit from easy access to top-rated schools, including Tuxedo Park School and St. John's-Ravenscourt School, making it an attractive choice for families seeking quality education for their children. The neighborhood is also home to upscale shopping centers like Tuxedo Village Shopping Centre, which offers a variety of boutiques, cafes, and restaurants, perfect for both everyday needs and leisurely outings.

For outdoor enthusiasts, Tuxedo boasts several parks and green spaces, including Assiniboine Park and its famous Leo Mol Sculpture Garden. These green havens provide residents with opportunities for jogging, picnicking, and enjoying nature trails, enhancing the neighborhood's appeal as a desirable place to live.

Investing in real estate in Tuxedo represents not just a purchase of property, but an investment in a lifestyle characterized by luxury, tranquility, and community. The neighborhood's strong property values and stable housing market make it an attractive option for buyers looking to secure a long-term residence in a prestigious and well-established community.

If you're considering purchasing a home in Tuxedo or exploring waterfront property for sale in Winnipeg, Jennifer Queen Real Estate is here to assist you every step of the way. Our experienced team specializes in matching buyers with their ideal properties, offering personalized service and expert guidance throughout the home-buying process. Whether you're a first-time homebuyer or looking to upgrade to your dream home, we are committed to helping you find the perfect property to suit your needs.

In conclusion, Tuxedo, Winnipeg, epitomizes luxury living with its elegant homes and serene waterfront properties. Whether you're captivated by the neighborhood's architectural beauty or the peacefulness of waterfront living, Tuxedo offers a lifestyle of sophistication and convenience unmatched in Winnipeg. Explore the possibilities awaiting you in Tuxedo today and let Jennifer Queen Real Estate help you find your perfect home in this prestigious neighborhood.

Contact us to schedule a viewing or learn more about available properties in Tuxedo and waterfront property for sale in Winnipeg. Take the first step towards making Tuxedo your home and discover why this neighborhood is a preferred choice for those seeking the best of urban living combined with natural beauty.

0 notes

Text

Winnipeg first responders make water rescue from fast-moving Assiniboine River

A person was sent to hospital in critical condition Sunday night after being rescued from strong currents on the Assiniboine River. The Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service (WFPS) says they got the call around 5:30 p.m., and sent crews to the Donald Street Bridge where they were able to rescue the person, who was being pulled toward the Red River by the current. Officials are warning Manitobans to…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Photo taken by L.B. Foote in 1919 of the Harrow Street and Academy Road intersection, with the roof of Kelvin High School visible. Wellington Crescent and the Assiniboine River are visible in the background. Photo via the Archives of Manitoba

2 notes

·

View notes