#Anti ageing treatment Dublin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Aesthetic Clinic: Why Is It Better Than a Normal Salon?

Experts in minimally invasive or completely non-surgical treatments can be found in an aesthetic clinic. While they might also provide pampering services, the primary goals of aesthetic treatments are anti-ageing therapies and the reduction of signs of ageing. The treatments include facials, fillers, and botox!

Many now favour aesthetic clinics over traditional salons, as they have become more and more well-liked in Dublin. We will explain why there has been such a change from traditional salons to aesthetic salons in this blog!

Certified Medical Professionals

One of the biggest benefits of visiting an aesthetic clinic is being treated by certified doctors! These procedures involve delicate materials and techniques.

Medical professionals are trained to employ the newest tools and technologies to provide patients with the exact answers they have been seeking.

Medical Facilities and High-Grade Items

Given that aesthetic treatments can be either surgical or non-surgical, a Dublin aesthetic treatment clinic should be equipped with clinical equipment and medical-grade facilities.

You can be confident that delicate and precise procedures like fillers will be carried out safely and provide the exact result you have been looking for because the doctors are qualified and experienced professionals.

Modern Apparatus and Technology

Every day, you will read in the newspapers or magazines about some new advancements in cosmetic technology. The good news is that these treatments will also be available at aesthetic clinics!

Aesthetic clinics are becoming more and more popular because they provide longer-lasting results with less recovery time! You only need to make one trip to the aesthetic clinic every few weeks; you do not have to visit the salon every day!

Where Can I Find the Best Aesthetic Clinic in Dublin?

When we consider an aesthetic clinic, we should keep in mind the sensitivity of the procedures and the importance of having a certified doctor, as mentioned before. You can eliminate the hassle and the tension by calling Lisa Thompson Aesthetics! They are the premier aesthetic clinic in Dublin, with cutting-edge technology and certified doctors.

0 notes

Text

Glowing Skin Awaits: Your Guide to Top Skin Clinics in Dublin

The following blog includes details about the leading skin clinic that is dedicated to providing top-notch services to make you beautiful.

Healthy, glowing skin is about beauty, self-care, confidence, and poise. Skin clinics have skyrocketed in Dublin recently due to ground treatments, personalized skincare solutions, and cutting-edge technologies. They can cure skin problems, including acne and aging signs, or renew your face.

This post will discuss what skin clinics in Dublin offer, including the services, and provide details on choosing the right one for you.

Why choose a skin clinic in Dublin?

Dublin has positioned itself as a hub for contemporary skincare. The skin clinics there provide treatments for all skin types and skin concerns. Here are some reasons to consider these centers:

• High-end Technology: They own top-of-the-line machines and products, such as facials that happen to be laser services, but are also the means of using the latest technology.

• Best Skin and Hair Experts: All dermatologists and other such qualified specialists are perfect in training in clinical skills and techniques in advanced skincare.

• Treatment Plans Customized to Your Skin Profile: Anti-aging, acne-this treatment is for you.

• Convenient: Centers are throughout the city, so you're never too far away from a great solution.

Most Popular Treatments in Dublin Skin Clinics

1. Hydrafacial:

It is one of the most popular treatments. This deeply cleanses and hydrates the skin in just one treatment.

Benefits:

· Suitable for all skin types

· Improves texture and elasticity

· Help lessen fine lines and wrinkles

· Removes blackheads and unclogs pores

· Gives that radiant and hydrating feel to the skin

Such treatment in Dublin generally lasts 30 to 60 minutes and yields immediate results without downtime. It's just the right thing for skin rejuvenation before a big occasion or as part of the monthly skincare routine.

2. Facials

They are at the core of effective skincare, and clinics across Dublin offer a variety to treat every once. There's a facial for you, whether you have oily or sensitive skin.

Popular Types of Facials Available in Dublin:

· Anti-Aging Facials: Targeting fine lines and wrinkles

· Deep Cleansing Facials: Best for acne-prone

· Hydrating Facials: To restore moisture and plumpness

· Brightening Facials: Combat dullness and enhance glow

· Sensitive Skin Facials: Soothe redness and irritation

Benefits of Having Regular Facials:

· Helps improve skin tone and texture

· Improved absorption of skin care products with penetrating

· Stimulates blood circulation

· Detoxification of the skin

· Helps put the mind at peace after a stressful day

What to Expect When Coming for Treatment in a Dublin Skin Clinic

A skin clinic Dublin visit usually begins with a consultation. The skincare specialist assesses you and discusses your aims. Based on this assessment, a custom treatment plan is drawn up.

The Following are the Typical Steps Involved:

· Skin Analysis: Using digital means or using a magnifying lamp

· Discussion of Concerns: Acne, pigmentation, dryness, etc.

· Treatment Plan Creation: Number of sessions, home care advice

How to Choose the Right Center

Choosing a trusted place can be complicated and overwhelming when faced with multiple offers. Below is a guideline that may help you in your quest:

1. Qualifications

Ensure that the professionals possess the required certificates and experience in skin treatments. This information is usually found on the clinic's website or in reviews elsewhere.

2. Check for Service Availability

Clinics that provide all services, from facials, hydrafacial Dublin, and microneedling to laser treatments and chemical peels, are usually within one's preferences.

3. You Have to Ask for a Consultation

A reliable clinic will conduct a skin consultation before recommending any procedure; this will ensure the treatment is tailored to your skin type and goals.

4. Evaluate the Reviews

Testimonials can illuminate the work and give you a good insight into its reputation, professionalism, and treatment results.

5. Cleanliness

A good clinic will maintain proper hygiene practices and standards concerning their equipment and treatment rooms.

Skin Care Clinics for Seasons in Dublin

Dublin's weather can be tough on the skin. Harsh winters and humid summers often lead to a lot of problems, such as dryness and the development of skin breaks. Here is the adaptation from skin clinics:

· Hydration and facials for barrier repair: super moisturizers in winter

· Summer treatments include deep cleansing, facials enriched with SPF, and oil control.

· Hydrafacials and monthly custom facials maintain overall skin health.

Most clinics also personalize their standard recommendations. So, you will have perfect skin no matter what season it is outside.

Home care after treatments from Clinics

It should typically be followed with proper care at home, which is necessary to preserve and prolong the results obtained at the clinic.

Skin Care advice after/Facial/Hydrafacial treatment:

· Do not wear make-up for at least 24 hours

· Gentle and hydrating Cleansers should be used

· SPF is used daily to protect the new skin

· No exfoliation for a few days.

· Drink lots of water to keep your skin hydrated.

Your specialist might also recommend the best products according to your skin's needs.

Final Thoughts: Invest In Your Skin Health.

A visit to a skin clinic in Dublin is more than just a luxury; it is investing in the health of your skin and maintaining your overall confidence. Be it the instant results of Hydrafacial or the customized experience of Facials Dublin, there is no shortage of options to achieve that glowing, beautiful skin.

Dublin Skin Clinic provides the perfect environment for a complete skincare journey with expert counseling, state-of-the-art technology, and sustained cassiterite. , the results speak for themselves: refreshing, glowing, and invigorated skin for any occasion.

0 notes

Text

Why Visit Skin Clinic In Dublin?

Are you a Dublin resident? If yes, then you don’t need to roam anywhere for advanced toxin treatments in Dublin. The best skin clinics in Dublin offer great and amazing services to people who are looking for radiant and flawless skin like never before.

So let us dive deeper into this blog and learn more about the Dublin skin clinics.

Is Skin Care Necessary?

Yes, Skincare is a necessary routine for proper health and well-being:

Prevention of skin cancer: Protects the body from harmful UV rays, so one has to always protect his skin using sunscreen for everyday activities. One can also wear a brimmed hat as well as cloth that protects from sun UV light.

Dry skin: Moisturizing acts as an avoidance measure for dry skin hence making skin prone to cracks that predispose to infection.

Anti-aging: As you get older, your skin loses collagen and elastin which may lead to wrinkling and bruising.

Skin barrier: Skin serves as a barrier to your internal systems, so it continues protecting it by taking proper care of it.

Acne prevention: Proper skin care prevents acne.

What Does Skin Clinic Dublin do?

Many of the reasons for regular visits to skin care specialists go beyond superficial cosmetic considerations. At Skin Clinics in Dublin, the emphasis on holistic health and personalized attention sets the standard of distinction in quality service for skin care. By gifting yourself with preventive care, targeted treatments, and a patient-centric approach, you can really develop your skin and unlock the full range of benefits from regular visits to skin care specialists. This has made the centers of advanced toxin treatment in Dublin the gateways to radiant and healthy skin, all under the plank of expertise and transformative care.

Facilities Offered by Skin Clinics in Dublin

Along with the expert team, skin clinics in Dublin have great facilities to offer. Here are some of the primary services:

PRP Facial Treatment.

Dermal Fillers.

Anti-wrinkle Injections.

Medical grade microneedling.

Philart Polynucleotide booster.

Advanced toxin treatment.

Mesotherapy.

Valmont Spa.

Restylane Skin Boosters.

Fat-dissolving injections.

Restylane skin boosters.

Profile Treatment.

GA facial treatments.

Why Choose GA Skin Care?

At GA Skincare we spend ourselves bringing out the best from the heart of Dublin in St Stephen's Shopping Centre. We offer advanced skincare routines with high-quality products and aesthetic treatments including anti-wrinkle injections, dermal fillers, and medical-grade microneedling. We also offer luxurious facial treatments and Valmont SPA treatments. As all our clients are matched with among the best professional practitioners in their field, we tend to focus more on superior results, using the leading global skincare brands such as Zo Skin Health, SkinCeuticals, Valmont, and many others to give our clients only high-class experiences.

Conclusion

After going through this blog, I hope now you understand why Skincare consultation is an essential tool to help you understand the state of your skin as well as recommend good products to use. It assists one in assessing your skin requirements possibly in relation to some factors such as lifestyle and the surrounding environment to help him/her achieve healthy skin. It helps people get expert advice for the betterment of their skin.

#skin care clinic#prp treatment#skin care treatment#advanced toxin treatment#botox ireland#anti wrinkle injections dublin

1 note

·

View note

Text

Best Facial Salon in Dublin, CA: Your Guide to Glowing Skin

Dublin, CA, a vibrant city in the heart of the San Francisco Bay Area, is home to many top-notch beauty and wellness centers. When it comes to achieving glowing, healthy skin, finding the best facial salon is key. Whether you’re looking for a relaxing spa experience or a targeted treatment for specific skin concerns, Dublin offers a variety of salons that cater to all your skincare needs. Here’s your guide to finding the best facial salon in Dublin, CA.

Why Getting a Facial is Important

Facials are more than just a luxury; they are an essential part of maintaining healthy, radiant skin. Here’s why you should consider incorporating facials into your skincare routine:

1. Deep CleansingFacials provide a deep cleanse that goes beyond what you can achieve at home. They remove dirt, oil, and impurities that clog pores, leading to clearer, healthier skin.

2. ExfoliationExfoliating treatments during a facial help remove dead skin cells, promoting cell turnover and revealing a brighter, smoother complexion.

3. Anti-Aging BenefitsMany facials include anti-aging treatments that help reduce fine lines, wrinkles, and age spots. Regular facials can keep your skin looking youthful and radiant.

4. Customized SkincareA professional facial is tailored to your skin type and concerns. Whether you have dry, oily, sensitive, or combination skin, a skilled esthetician will choose the right products and techniques to address your specific needs.

5. Stress ReliefFacials are not only beneficial for your skin but also provide a relaxing, stress-relieving experience. The soothing environment and gentle massage can help you unwind and rejuvenate.

Top Facial Salons in Dublin, CA

1. The Rouge Esthetics and SpaKnown for its personalized approach and high-quality treatments, The Rouge Esthetics and Spa is a favorite among Dublin residents. They offer a wide range of facials, including deep cleansing, hydrating, and anti-aging treatments. The spa uses top-notch skincare products, ensuring that your skin receives the best care possible.

2. LaBelle Day Spas & SalonsWith a reputation for excellence, LaBelle Day Spas & Salons offers luxurious facials that leave your skin glowing and refreshed. Their skilled estheticians customize each treatment to suit your skin type and concerns, from acne-prone to mature skin. The tranquil environment and professional service make this a top choice for those seeking a premium facial experience.

3. Skin ReflectionsIf you’re looking for advanced skincare solutions, Skin Reflections is the place to go. This salon specializes in medical-grade facials that target specific skin issues such as hyperpigmentation, fine lines, and acne. Their knowledgeable staff and state-of-the-art equipment ensure that you receive effective, results-driven treatments.

4. The Bloom Room EstheticsThe Bloom Room Esthetics offers a range of organic and holistic facial treatments that focus on nourishing and rejuvenating the skin. Their facials are designed to be gentle yet effective, using natural products that are free from harsh chemicals. This salon is ideal for those who prefer a more natural approach to skincare.

5. Rejuvenate Day SpaRejuvenate Day Spa is known for its calming ambiance and expert skincare services. Their facial treatments are tailored to your needs, whether you’re looking to hydrate, brighten, or detoxify your skin. The spa’s experienced estheticians take the time to understand your skin concerns and recommend the best treatments for optimal results.

How to Choose the Best Facial Salon in Dublin, CA

1. Read Reviews and TestimonialsBefore booking an appointment, take the time to read reviews and testimonials from previous clients. This can give you insight into the quality of service, the expertise of the staff, and the overall experience at the salon.

2. Consider the Range of ServicesLook for a salon that offers a variety of facial treatments, from basic cleansing facials to advanced anti-aging and acne treatments. A salon with a comprehensive menu ensures that you can find the right facial for your needs.

3. Check the Products UsedThe quality of products used in your facial can make a significant difference in the results. Opt for salons that use high-quality, professional-grade skincare products, especially if you have sensitive skin or specific concerns.

4. Experience and Expertise of EstheticiansThe skill and knowledge of the esthetician are crucial for a successful facial. Choose a salon where the staff is well-trained, experienced, and able to provide personalized advice and treatments.

5. Ambiance and CleanlinessA clean, relaxing environment is essential for an enjoyable facial experience. Visit the salon beforehand if possible, or take a virtual tour on their website to ensure that the ambiance meets your expectations.

Conclusion

Finding the best facial salon in Dublin, CA, is key to achieving healthy, glowing skin. Whether you prefer a luxurious spa experience or a more targeted, medical-grade treatment, Dublin has a salon that will meet your skincare needs. By considering factors like reviews, services offered, and the expertise of estheticians, you can choose the perfect place to pamper your skin and enjoy a radiant complexion.

0 notes

Text

Unlocking Fertility Insights: The Role of AMH Testing in Reproductive Health

Understanding AMH Testing

AMH testing has revolutionized the way we assess female fertility and ovarian reserve. As one of the most reliable indicators of a woman's reproductive potential, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels in the blood provide valuable insights into ovarian function and egg supply. This article delves into the significance of AMH testing in reproductive health and fertility planning.

Deciphering AMH: A Key to Ovarian Reserve

AMH, produced by cells within the ovarian follicles, reflects the number of small follicles containing eggs in a woman's ovaries. Since these follicles represent the ovarian reserve, AMH levels offer critical information about a woman's reproductive capacity. Unlike other hormones that fluctuate throughout the menstrual cycle, AMH levels remain relatively stable, making it a reliable marker for ovarian reserve assessment.

The Importance of AMH Testing in Fertility Planning

The AMH fertility test serves several essential purposes in fertility planning:

Predicting Response to Fertility Treatment: For women undergoing assisted reproductive technologies such as IVF, an AMH test helps predict how ovaries will respond to stimulation medications, guiding treatment protocols and optimizing outcomes.

Assessing Age-related Fertility Decline: While age remains the most significant factor in female fertility, AMH testing provides additional insights, especially for women with irregular menstrual cycles or other fertility concerns.

Identifying Ovarian Dysfunction: Abnormal AMH levels can indicate underlying ovarian dysfunction or conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), prompting further evaluation and treatment.

The AMH Testing Process

An AMH blood test involves a simple blood draw, typically performed on any day of the menstrual cycle. The blood sample is then analyzed in a laboratory to measure AMH levels. Results are usually available within a few days and are interpreted in conjunction with other fertility assessments, such as ultrasound evaluations and hormone tests.

Where to Access AMH Testing

In Ireland, accessing an anti mullerian hormone test is convenient, with many fertility clinics and reproductive health centers offering this service. Reputable clinics like ReproMed Ireland in Dublin specialize in comprehensive fertility assessments, including AMH testing. These clinics provide expert interpretation of results and personalized fertility consultations to guide individuals on their fertility journey.

Interpreting AMH Test Results

AMH test Ireland results are typically reported in nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL). While interpretation may vary based on factors such as age and menstrual cycle regularity, generally:

High AMH Levels: High AMH levels may indicate a robust ovarian reserve, which can be advantageous for fertility treatment but may also be associated with conditions such as PCOS.

Low AMH Levels: Low AMH levels may suggest diminished ovarian reserve, potentially impacting natural conception and response to fertility treatment.

AMH test Dublin plays a pivotal role in assessing ovarian reserve and guiding fertility planning. By providing valuable insights into ovarian function and egg supply, AMH testing empowers individuals to make informed decisions about family planning and fertility treatment. With AMH testing readily available in Ireland, individuals can proactively manage their reproductive health and take proactive steps toward achieving their family-building goals.

0 notes

Text

Kiehls Launches 1L Refillable's For It's Best Sellers

Kiehls Launches 1L Refillable’s For It’s Best Sellers

Since 1851, Kiehl’s has always strived for better. From responsible formulations, packaging &manufacturing, to supporting communities and helping to reduce environmental impact. Kiehl’s is proud to continue its journey towards a Future Made BetterTM with its first foray into refillable beauty. Kiehls New refillable 1L products The NEW Kiehl’s Pouch Refillables are apart of their ever-evolving…

View On WordPress

#Are kiehls products clean?#beauty news#featured#Is kiehls a clean brand?#Is kiehls a good brand?#kie#Kiehl’s#kiehls#kiehls anti ageing#Kiehls blue herbal spot treatment#kiehls calendela water cream#kiehls creamy avocado eye treatment#Kiehls Dublin#kiehls eco friendly#Kiehls eye cream#Kiehls Just Like Us#Kiehls malaysia#Kiehls promo code#kiehls refillable#Kiehls review#Kiehls sale#kiehls sustainability#kiehls sustainable#Kiehls uk#Kiehls Ultra Facial Cream#kiehlsuk#skin care#skincare#what is Kiehls best product?#Which kiehls eye cream is the best?

0 notes

Text

Betty Friedan and Second Wave Feminism in the USA and Ireland

by Deirdre Swain

The Cork City Reference Library holds a large collection of books about feminism, particularly Irish feminism. BorrowBox also possesses a range of eBooks on feminism that were published in the last 7 years. In this article, I will discuss Betty Friedan, a well-known American feminist who was born in February 1921, and the second-wave feminist movement in Ireland. I will then introduce a reading list of books on feminism which are available on BorrowBox. I will also provide a reading list of books on feminism which will be available in the Reference Library once it re-opens to the public.

Betty Friedan and Second Wave Feminism in the USA

The recent TV drama, Mrs. America depicts the struggle to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment in the USA in the 1970s. The popularity of this TV series demonstrates a renewed interest in the women’s liberation movement and certain prominent and influential American feminists, namely Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, Shirley Chisholm and Bella Abzug.

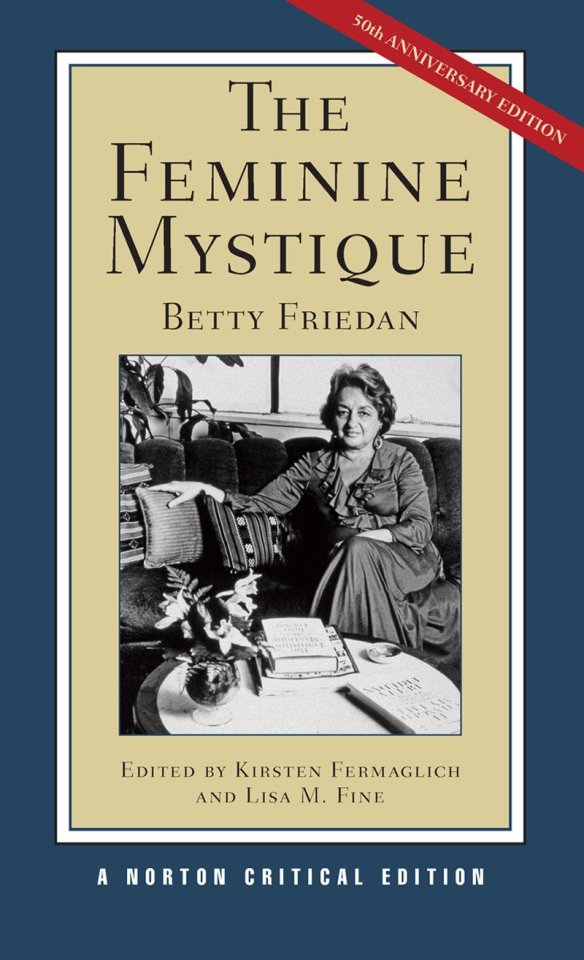

February 2021 marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Betty Friedan, one of these second wave feminists and author of the seminal feminist text, The Feminine Mystique. She was born Bettye Naomi Goldstein to a Jewish family in Peoria, Illinois on 4 February 1921. Her mother, Miriam Horwitz, was an unhappy housewife whose parents, Hungarian Jewish immigrants, did not allow her to go to university. Miriam encouraged Betty to do the opposite, and she strongly supported her daughter’s education. Betty went to university in Smith College, graduating in 1942. She then studied Psychology in the University of California, Berkeley, for a year. Thereafter, she worked as a journalist in New York, writing about the Jim Crow laws and anti-Semitism. Later, she worked as a women’s magazine writer. In 1949, she married Carl Friedman (later Friedan), and they had 3 children. They got divorced in 1969.

In 1957, Betty attended the 15th anniversary of her graduation from Smith College. At this reunion, she conducted a survey on her former fellow students (females) to explore the direction of their lives since graduation. She was perturbed by the amount of discontent among them. This revelation about the lives of her peers led to the writing of her book, The Feminine Mystique. This publication recounts the dilemma of suburban housewives, who are expected to spend all of their time on domestic duties and the rearing of children. They are overshadowed constantly by the thought, “Is this it?” They feel guilty for not being satisfied with their role, but they cannot deny the fact that they are unfulfilled. The “feminine mystique” of the book’s title is the societal assumption that household duties and motherhood alone will give women a sense of achievement. Friedan coined the phrase “the problem with no name” to describe women’s unhappiness with and inability to live up to this feminine mystique. She contended that women could have a successful career as well as a family.

The book sold three million copies and resonated with many suburban women because it showed them that they were not alone in their feelings of dissatisfaction. It was also strongly criticised for its homophobic language and for excluding Black and working class women. It spoke from a standpoint where every American housewife was white and middle class. Her solution to the problem of “the feminine mystique” (delegating housework) were also criticised for being inadequate and for failing to tackle the problem fully.

Friedan was aware of some of the shortcomings of The Feminine Mystique, and she wrote a second book to tackle some of the problems not resolved in the first one, including the double enslavement of working women who still had to do all the housework. The title of this book is The Second Stage. She also wrote numerous other books, including It Changed My Life: Writings on the Women’s Movement, which was published in 1976 and Beyond Gender: the New Politics of Family and Work, which was published in 1998.

Betty Friedan was a women’s activist and fought for reproductive rights, equal pay, equal representation and equality in hiring. She co-founded the National Organisation for Women (NOW) in 1966. In 1969, she launched the National Association for Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL Pro-Choice America). She co-founded the National Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC) with Gloria Steinem, Bella Abzug and several other women in 1971. The NWPC is a US organisation which supports and trains women who seek elected and appointed offices in all levels of government. Betty was quick-tempered, and she tended to lash out at people, including other feminists such as Gloria Steinem, even though they had similar aspirations for women. She was also quite disparaging in her treatment of lesbian women, referring to them as “the lavender menace”.

Later in her life, Friedan became a Zionist and fought to expose Anti-Semitism in the women’s movement. She received the Eleanor Roosevelt Leadership Award in 1989 and was awarded honorary degrees by the State University of New York and Columbia University. She died on her birthday, 4 February, in Washington DC in 2006, aged 85.

What advances for women were taking place in Ireland during the time of Betty Friedan’s activism in the United States?

The Irish Women’s Liberation Movement

In the summer of 1970, five women met in Bewley’s café in Dublin and decided that it was time for some drastic changes in Irish women’s lives; time to fight for equal rights. That day, these women held what was to be the first meeting of the Irish Women’s Liberation Movement (IWLM) group, the first radical women’s liberation group in Ireland. Although the group lasted little more than seven months, its legacy changed women’s lives significantly and positively. As proof of the success of the IWLM, the two injustices that this group fought hardest against – the marriage bar, which was abolished in 1973, and the illegality of contraception – are unimaginable in today’s world.

Margaret Gaj owned the restaurant, Gaj’s, on Baggot Street, where the IWLM would meet every Monday night. Margaret Gaj was passionate about women’s rights. Her circle of friends included Sinn Féin official Máirín de Búrca, journalist Mary Maher, who was interested in socialist issues, Máirín Johnston, who was a member of the Communist Party and who was also active in the Labour Party and Dr. Moira Woods, who was in an organisation called Irish Voice on Vietnam, which protested against the war in Vietnam. These five women started the IWLM group that day in the summer of 1970 in Bewley’s café, but around a dozen women were actively involved in the founding of this women’s organisation, the majority of them journalists. Nell McCafferty and Mary Kenny, both journalists, were two prominent founders of the IWLM.

Chains or Change was the title of the IWLM charter. It was put together in the form of a booklet which detailed the goals and ideals that the IWLM strove for. There were 6 demands: equal pay; an end to the marriage bar that kept women from working after they got married; equal rights in law; justice for widows, deserted wives and “unmarried mothers”; equal education opportunities; and the legalisation of contraception. Neither abortion nor divorce were mentioned at all in Chains or Change. When the most basic civil rights for women were being fought for, abortion and divorce did not even arise because they were not considered to be a priority. The booklet was a milestone in the history of women’s rights in Ireland, because it was the first time that anyone had published a comprehensive list of the injustices that church, state and social code perpetuated against women.

Nell McCafferty

Nell McCafferty was born in Derry. She got her degree from Queen’s University in Belfast and trained as a teacher, but she could not get a job in Derry, because the Protestant schools knew she was Catholic, and the Catholic schools did not think she was a real Catholic but, rather, a communist. She moved to Dublin to work as a journalist for the Irish Times. Nell writes in her autobiography of an incident from when she first moved to Dublin; she wanted to buy a record player on hire purchase but was told that no woman could sign an agreement without the co-signature of a male guarantor. A male stranger signed for her because she did not know any men in Dublin. This man was unemployed, and her own earnings amounted to five times more than his welfare entitlements.

Nell was a founding member of the Irish Women’s Liberation Movement (IWLM). In the IWLM, Nell was someone who could be depended upon to put forward forceful arguments that were backed up by accurate facts, and she could convey them both in writing and in person.

Nell’s journalism was objective, and she used it to bear witness to the struggles of the oppressed. She did not even have to give her opinion; her writing style and her description of what she observed in society were enough to expose hypocrisy and injustice without her having to comment on the issues herself. As well as being a feminist activist, Nell was also a civil rights activist on issues in Northern Ireland. When she started to work at the Irish Times, she joined the “women’s page” staff. Initially, she was fearful that this would involve writing about fashion, cooking and babies, but it actually enabled her to write on issues regarding women’s liberation and women’s rights.

The Contraceptive Train

In May 1971, the IWLM founders organised what became known as the “contraceptive train”, which was a protest against the fact that contraceptives were illegal in the Republic of Ireland. Nell McCafferty said that she had got the idea for the contraceptive train when she was in Northern Ireland at a civil rights march. The march went from North to South, and at the border, a student activist called Cyril Tallman held up a copy of Edna O’Brien’s novel Country Girls in one hand and a Durex condom in the other, saying that both were banned in the South. Nell was initially indignant about the condom, but the following year when the IWLM was talking about contraceptives, Nell got the idea of reversing the journey from Dublin to the North.

There was a ban on contraception in the Republic of Ireland, which was enshrined in the 1935 Criminal Law Act. This made the importation, distribution and sale of contraceptive devices a criminal offence. Advertising contraceptives was also illegal. The contraceptive pill was available in Ireland only on prescription, as a “menstrual cycle regulator”.

There were 47 founders and members of the IWLM on the contraceptive train on 22 May 1971, just enough to fill two carriages. However, when Nell McCafferty asked for a packet of contraceptive pills in a Belfast pharmacy, she was asked for a prescription, and the same happened when she asked for a coil, loop and Dutch cap. It turned out that the only contraceptives that were available in Belfast without prescription were condoms and spermicidal jelly. Nell was not happy with the prospect of taking a stand at Dublin customs with just condoms and spermicidal jelly, so it was decided that packets of aspirins would be bought, since they were similar enough in appearance to contraceptive pills that it was hoped they would pass for same! When the women arrived at customs in Dublin, the customs officers told them they were breaking the law, but let them through, because arresting them was not an option for them. The contraceptive train accomplished what it set out to do; the state refused to lift the ban on contraceptives, but it also failed to enforce it. The IWLM exposed this hypocrisy and proved that women would be free to import contraceptives from the North into the Republic from then on without any interference from law enforcement officials. Nell McCafferty made a statement at the train station, and two of the women went on the Late Late Show on TV to talk about the experience.

Mary Robinson failed in March and May of 1971 to get the Senate to add her Contraceptive Bill to its order paper. Despite Mary Robinson’s and the IWLM’s efforts to legalise contraceptives, it was not until 1979 that the government passed the Family Planning Act. This Act allowed solely married couples to get access to contraceptive devices other than the pill with a prescription. Family Planning clinics were already selling condoms, but the government was turning a blind eye to this because they were accepting “donations” in exchange for the condoms. In 1990, the Irish Family Planning Association was fined £500 for selling condoms in the Virgin Megastore in Dublin. Finally, in 1992, the government extended legislation to allow supermarkets and retail stores to sell condoms. The contraceptive train literally set the wheels in motion regarding the legalisation of contraceptives, but it took a long time before the law was changed for the benefit of women.

References

-Code, L., ed. (2000). Encyclopedia of Feminist Theories. London: Routledge.

-Parry, M. (2010). ‘Betty Friedan: Feminist Icon and Founder of the National Organization for Women’, American Journal of Public Health, 100 (9), pp. 1584-1585.

-Shteir, R. (2021). ‘Why We Can’t Stop Talking about Betty Friedan’, New York Times, 3 February. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/03/us/betty-friedan-feminism-legacy.html (Accessed: 9 February 2021).

McCafferty, N. (2004). Nell: a Disorderly Woman. Dublin: Penguin Ireland.

Stopper, A. (2006). Mondays at Gaj’s: The Story of the Irish Women’s Liberation Movement. Dublin: The Liffey Press.

Reading list of books on feminism

Available on BorrowBox:

-Dear Ijeawele, or a Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (published in 2017): https://fe.bolindadigital.com/wldcs_bol_fo/b2i/productDetail.html?productId=HCU_469861&fromPage=1&b2bSite=4813

-Feminist Fight Club, by Jessica Bennett (published in 2016): https://fe.bolindadigital.com/wldcs_bol_fo/b2i/productDetail.html?productId=PRU_398091&fromPage=1&b2bSite=4813

-Feminists Don’t Wear Pink (And Other Lies), by Scarlett Curtis (published in 2018): https://fe.bolindadigital.com/wldcs_bol_fo/b2i/productDetail.html?productId=PRU_574840&fromPage=1&b2bSite=4813

-Give Birth Like a Feminist, by Milli Hill (published in 2019): https://fe.bolindadigital.com/wldcs_bol_fo/b2i/productDetail.html?productId=HCU_655895&fromPage=1&b2bSite=4813

-We Should All Be Feminists, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (published in 2014): https://fe.bolindadigital.com/wldcs_bol_fo/b2i/productDetail.html?productId=HCP_402800&fromPage=1&b2bSite=4813

Available in the Reference Library, Grand Parade

-Code, L., ed. (2000). Encyclopedia of Feminist Theories. London: Routledge.

-McCafferty, N. (1984). The best of Nell: a selection of writings over fourteen years. Dublin: Attic Press.

- Stopper, A. (2006). Mondays at Gaj’s: The Story of the Irish Women’s Liberation Movement. Dublin: The Liffey Press.

-Pierse, Mary S. (ed.) (2010). Irish Feminisms, 1810-1930. Abingdon: Edition Synapse/Routledge (5 volumes).

-Owens, R. (2005). A social history of women in Ireland, 1870-1970. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

-Connolly, L. and O’Toole, T. (2005). Documenting Irish Feminisms: the Second Wave. Dublin: The Woodfield Press.

-Connolly, L. (2002). The Irish women’s movement: from revolution to devolution. Dublin: Lilliput Press.

-Rose, C. (1975). The female experience: the story of the woman movement in Ireland. Galway: Arlen House.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Profhilo Fillers for a Picture-Perfect Wedding Look

The wedding day is one of the most important days of any woman’s life. Hence, it is quite natural that she would want to look her very best for her husband-to-be and everyone in attendance. Rather than going for superficial skin treatments, why not go in for something that’s skin-deep?

Lisa Thompson Aesthetics provides the most sought-after Profhilo Filler treatment in Dublin that gives you a rush of youthful glow and radiance that is bound to make you steal the show. So, what exactly are Profhilo Fillers? Let’s have a good look.

What is the Profhilo Filler Treatment?

Profhilo fillers are a non-surgical and minimally invasive way to boost collagen from deep within the skin. The pain-free skin revitalising fillers smooth out wrinkles, reduce fine lines, and restore lost glow to the skin. The treatment makes use of injections with fine needles to inject naturally derived hyaluronic acid that helps boost collagen within the skin.

Where can Profhilo Fillers be used?

The fillers are used for filling and smoothening out different areas of the face such as the mouth area, cheeks, forehead, laugh lines, nasolabial folds, and around the eyes. The treatment is very quick as it takes only 30 minutes and is virtually painless.

So, choose Lisa Thompson Aesthetics for the best Profhilo Filler treatment in Dublin right away!

#profhilo#profhilo filler#jawline filler#aesthetic clinic#aesthetic clinic dublin#aesthetic treatment clinic dublin#anti ageing treatment dublin#jawline filler dublin

0 notes

Text

Methuselah Foundation Unveils ELONgevity Protection to Support Human Longevity Initiatives, Provide Access to Promising Experimental Therapies

Methuselah Foundation Unveils ELONgevity Protection to Support Human Longevity Initiatives, Provide Access to Promising Experimental Therapies

Dogelon Mars (ELON) will be the key for terminally ill participants to unlock investigational treatments that offer a fighting chance to overcome deadly diseases DUBLIN, Sept. 20, 2022 /PRNewswire/ — Methuselah Foundation Co-founder and CEO David Gobel announced the formation of the ELONgevity Protection Project to promote human anti-aging efforts and provide members diagnosed with terminal…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

When Fred Halliday—scholar, activist, journalist and teacher—died two years ago at the too-early age of 64, obituaries and tributes swamped the British press; the New Statesman subtitled its remembrance “The death of a great internationalist.” Halliday was a truly original thinker, a combination of Hannah Arendt (in her concern for the connection between ethics and politics) and Isaac Deutscher (in his materialist yet supple approach to history). Halliday also knew a little something about the Middle East: he spoke Arabic, Farsi and at least seven other languages, and he traveled widely throughout the region, including in Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, Palestine, Israel, Libya and Algeria. He is one of the very few writers who, after 9/11, understood the synthesis between fighting radical Islam and opposing the brutal inequities of the neoliberal global order. He was an uncategorizable independent, supporting, for instance, the communist government in Afghanistan and the US invasion of that country. He embodied the dialectic between utopianism and realism. In his scholarship and research, in his outspokenness and courtesy, in the complexity of his thinking, he was the model of a public intellectual. It is Halliday’s writings—not those of Noam Chomsky, Edward Said, Alexander Cockburn, Christopher Hitchens or Tariq Ali—that can elucidate the meaning of today’s most virulent conflicts; it is Halliday who represented radicalism with a human face. It says something sad, and discouraging, about intellectual life in our country that Halliday’s death—which is to say, his work—was ignored not only by mainstream publications like The New York Times but by their left-wing alternatives too (including this one).

It is cheering, then, that a selection of essays, written by Halliday for the website openDemocracy between 2004 and 2009, has just been published by Yale University Press. Called Political Journeys, it gives a taste—though only that—of the extraordinary range of Halliday’s interests; included here are analyses of communism , the cold war, Iran’s revolution, post-Saddam Iraq, violence and politics, radical Islam, the legacies of 1968 and feminism. The book gives a sense, too, of Halliday’s dry humor—he loved to recount irreverent political jokes from the countries he had visited—and his affection for lists, as in the essay “The World’s Twelve Worst Ideas” (No. 2: “The only thing ‘they’ understand is force”). But most of the articles, written as they were for the Internet, are comparatively short and represent a brief span in a long career; this necessarily sporadic volume will, one hopes, lead readers to some of Halliday’s two dozen other books and more extensive essays.

Political Journeys is a well-chosen title for the collection. It alludes not just to Halliday’s travels but also to the ways his ideas—especially about revolution, imperialism and human rights—changed in reaction to tumultuous world events over the course of four decades. For this he has often been attacked, even posthumously. Earlier this year, Columbia University professor Joseph Massad opened a piece about Syria, published on the Al Jazeera website, by dismissing Halliday—along with his “Arab turncoat comrades”—as a “pro-imperial apologist.” (Massad also put forth the novel idea that Syria “has been…an agent of US imperialism,” which might be news to Bashar al-Assad and the leaders of Iran and Hezbollah, Syria’s allies in the so-called axis of resistance.) Yet it was precisely Halliday’s intellectual flexibility—his ability to derive theory from experience rather than shoehorn the latter into the former—that was one of his greatest strengths. Pace Massad,

Halliday didn’t move from Marxism into imperialism, neoconservatism, neoliberalism or “turncoatism”; rather, he developed a deeper, more humane and far sturdier kind of radicalism. It was one that refused to hide—much less celebrate—repression, carnage and virulent nationalism behind the banner of progress, world revolution, selfdetermination or anti-colonialism. Halliday sought not to reject the socialist tradition but to reconnect it to its heritage—derived from the Enlightenment, from 1789, from 1848— of reason, rights, secularism and freedom. He would also develop an unsparing critique of the anti-humanism that, he thought, was ineradicably embedded in the revolution of 1917 and its successors.

Halliday believed that the duty of committed intellectuals is to keep their eyes open, to learn from history, to be humble enough to be surprised (and to admit being wrong). The alternative was what he called “Rip van Winkle socialism.” He sometimes told his friends, “At my funeral the one thing no one must ever say is that ‘Comrade Halliday never wavered, never changed his mind.’”

* * *

Fred Halliday was born in 1946 in Dublin and raised in Dundalk, a town near the northern border that, he pointed out, The Rough Guide to Ireland advises tourists to avoid. The Irish “question” and Irish politics remained, for him, a touchstone—though more as a warning than an inspiration, especially when it came to Mideast politics. The unhappy lessons of Ireland, he wrote in 1996, included “the illusions and delusions of nationalism” and “the corrosive myths of deliverance through purely military struggle.” He added: “A good dose of contemporary Irish history makes one sceptical about much of the rhetoric that issues from dominant and dominated alike.… [A] critique of imperialism needs at the very least to be matched by some reserve about most of the strategies proclaimed for overcoming it.” Growing up in the midst of the Troubles, Halliday developed, among other things, a healthy aversion to histrionic nationalism and the repugnant concept of “progressive atrocities.”

Halliday graduated from Oxford in 1967 and then attended the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Later he would earn a PhD from the London School of Economics (LSE), where, for over two decades, he taught students from around the world and was a founder of its Centre for the Study of Human Rights. (The intellectual and governing classes of the Middle East are sprinkled with his graduates.) He was an early editor of the radical newspaper Black Dwarf and, from 1969 to 1983, a member of the editorial board of the New Left Review, a journal for which he occasionally wrote even after he broke with it over key political issues. He immersed himself in the revolutionary movements of his time and gathered an enviable range of friends, interlocutors and contacts along the way: traveling with Maoist Dhofari rebels in Oman; working at a student camp in Cuba; visiting Nasser’s Egypt, Ben Bella’s Algeria, Palestinian guerrillas in Jordan and Marxist Ethiopia and South Yemen (the subject of his dissertation). He wasn’t shy: he proposed a two-state solution to Ghassan Kanafani of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, infamous for its hijackings; argued with Iran’s foreign minister about the goals of an Islamic revolution; told Hezbollah’s Sheik Naim Qassem that the group’s use of Koranic verses denouncing Jews was racist—“a point,” Halliday dryly noted, “he evidently did not accept.”

Halliday received, and accepted, invitations to lecture in some of the Middle East’s most repressive countries, including Ahmadinejad’s Iran, Qaddafi’s Libya and Saddam’s Iraq, where a government official told him, without shame or embarrassment, that Amnesty International’s reports on the regime’s tortures and executions were correct. Clearly, he was no boycotter. But neither was he seduced by these visits: in 1990, he described Iraq as a “ferocious dictatorship, marked by terror and coercion unparalleled within the Arab world”; in 2009, he reported that the supposedly new, rehabilitated Libya was just like the old, outcast Libya: a “grotesque entity” and “protection racket” that was regarded as a joke throughout the Arab world. His moral compass remained intact: that year, he warned the LSE not to accept a £ 1.5 million donation from the so-called Charitable and Development Foundation of the dictator’s son, Saif el-Qaddafi. Alas, greed trumped principle, and Halliday’s arguments were rejected—which led, once the Arab Spring reached Libya, to the LSE’s public disgrace and the resignation of its director.

* * *

In May 1981, Halliday published an article on Israel and Palestine in MERIP Reports, a well-respected Washington journal that focuses on the Middle East and is closely identified with the Palestinian cause. It is an astonishing piece, especially in the context of its era, more than a decade before the Palestine Liberation Organization recognized Israel’s right to exist and the signing of the Oslo Accords. It is no exaggeration to say that, at the time, the vast majority of the left, Marxist and not, held anti-Israel positions of various degrees of ferocity; to do otherwise was to risk pariahdom.

While harshly critical of Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians and of the occupation , Halliday proceeded to question—and forcefully rebuke—the bedrock beliefs of the left: that Israel was a colonial state comparable to South Africa; that Israelis were not a nation and had no right to self-determination; that Israel was a recently formed and therefore inauthentic country (most states in the Middle East—including, for that matter, Palestine— are modern creations of imperialist powers); that a binational state was desired by either Israelis or Palestinians and, therefore, could be a recipe for anything other than civil war and a harshly authoritarian government. (Halliday asked a question often ignored by revolutionaries: Why would anyone want to live under such a regime?)

Most of all, he challenged the irredentism of the Palestinian movement and its supporters. Partition, he presciently warned, is “the only just and the only practical way forward for the Palestinians. They will continue to pay a terrible price, verging on national annihilation, if they prefer to adopt easier but in fact less realizable substitutes, and if their allies and supposed friends continue to urge such a course upon them.” Halliday stressed that a truly revolutionary strategy cannot be “at variance with reality.” Solidarity without realism is a form of betrayal.

The reality principle, and its absence, was a theme Halliday would return to frequently, as in his reappraisal of the legacy of 1968. “It does not deserve the sneering, partisan dismissal,” he wrote in 2008. But nostalgic celebration was also unearned, for “the problem is that in many ways, we lost.” Despite triumphal rhetoric, the year of the barricades led not to worldwide revolution but to conservative governments in France, England and the United States (Richard Nixon). In the communist world, the situation was even worse: “It was not the emancipatory imagination but the cold calculation of party and state that was ‘seizing power.’” In Prague, socialist reform was crushed; in Beijing, the Cultural Revolution’s frenzy reached new heights.

Yet Halliday, like most of us, was sometimes guilty of letting wishful thinking cloud his vision too. In 2004, he called for the United Nations to assume authority in Iraq, which was then in free fall. This ignored the fact that Al Qaeda’s shocking bombings of the UN’s Baghdad mission the previous year—resulting in the death of Sergio de Mello, the secretary general’s special representative in Iraq, and so many others—had disposed, rather definitively, of that issue; the UN had withdrawn its staffers and, clearly, could not ask them to undertake another death mission. (Nor was there any indication that the UN’s member nations—many of whom opposed any intervention in Iraq—would have supported such a proposition.) And his claim, made in 2007, that “a set of common values is indeed shared across the world,” including a commitment to “democracy and human rights,” is hard to square with much of Halliday’s own reporting—such as his 1984 encounter with a longtime acquaintance named Muhammad, who had formerly been a member of the Iranian left. Now a supporter of the regime, Muhammad visits Halliday in London and explains, “We don’t give a damn for the United Nations.… We don’t give a damn for that bloody organisation, Amnesty International. We don’t give a damn what anyone in the world thinks.… We have made an Islamic Revolution and we are going to stick to it, even if it means a third world war.… We want none of the damn democracy of the West, or the socalled freedoms of the East.… You must understand the culture of martyrdom in our country.” Indeed, Halliday’s optimism of the intellect here is belied by even a casual look at any of the world’s major newspapers— whether from New York or Paris, Baghdad or Beirut—on any given day.

* * *

Iran, which Halliday first visited in the 1960s as an undergraduate, was foundational to his political development; he analyzed, and re-analyzed, its revolution many times, as if it was a wound that could not stop hurting. (Iran is the only country to which Political Journeys devotes an entire section of essays.) His initial study of the country, Iran: Dictatorship and Development, was written just before the anti-Shah revolution of early 1979. Based on careful observation and research, the book scrupulously analyzed Iran’s class structure, economy, armed forces, government, opposition movements, foreign policy—everything, that is, but the role of religion, which Halliday seemed to regard as essentially a front for political demands, and which he vastly underestimated. The book’s last sentence reads, “It is quite possible that before too long the Iranian people will chase the Pahlavi dictator and his associates from power… and build a prosperous and socialist Iran.”

Events moved quickly. In August 1979, Halliday filed two terrifying dispatches from Tehran, published in the New Statesman, documenting the chaotic atmosphere of fear and xenophobia, the outlawing of newspapers and political parties, and the brutal crackdown on women, intellectuals, liberals, leftists and secularists. “It does not take one long to sense the ferocious right-wing Islamist fervour that grips much of Iran today,” he began. Later, he would write, “I have stood on the streets of Tehran and seen tens of thousands of people…shouting, ‘Marg bar liberalizm’ (‘Death to liberalism’). It was not a happy sight; among other things, they meant me.” A revolution, he realized, could be genuinely anti-imperialist and genuinely reactionary.

But the problem wasn’t only Iran or radical Islam. As the ’70s turned into the ’80s, it became clear—or should have—that most of the third world’s secular revolutions and coups (in Algeria, Syria, Libya, Ethiopia and, especially, Iraq) had failed to fulfill their emancipatory promises. Each became a one-party dictatorship based on repression, torture and murder; each stifled its citizens politically, intellectually, artistically, even sexually; each remained mired in inequality and underdevelopment. None of this could be explained, much less justified, by the legacy of colonialism or the crimes of imperialism, real as those are. These were among the central issues that led to Halliday’s rift with the New Left Review—and that continue to divide the left, both here and abroad. Indeed, it is precisely these issues that often underlie (and sometimes determine) the debates over humanitarian intervention, the meaning of solidarity, the US role as a global power, the centrality of human rights and of feminism, and the Israel-Palestine conflict. (In 2006, Halliday would sum up his points of contention with his former comrades, especially their support of death squads and jihadists in the Iraq War : “The position of the New Left Review is that the future of humanity lies in the back streets of Fallujah.”)

Halliday’s revised thinking—his emphasis on democracy and rights; his aversion to the particularist claims of tribe, nation, religion or identity politics; his unapologetic secularism; his questioning of imperialism as a purely regressive force—is evident in his enormously compelling book Islam and the Myth of Confrontation, published in 1996. (Halliday dedicated it to the memory of four Iranian friends, whom he lauded as “opponents of religiously sanctioned dictatorship.”) In this volume he took on two still prevalent, and still contested, concepts: the idea of human rights as a Western imposition on the third world, and the theory of “Orientalism.”

Halliday argued that, despite the assertions of covenants such as the 1981 Universal Islamic Declaration of Human Rights (which defines “God alone” as “the Source of all human rights”) and the 1990 Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam (which defines “all human beings” as “Allah’s subjects”), there is no such thing as Islamic human rights—or, indeed, of rights derived from any religious source. Such rights apply to everyone and, therefore, must be based on man-made, universalist principles or they are nothing: it is the “equality of humanity,” not the equality before God, that they assert. (That is why they are human rights.) Because rights are grounded in the dignity of the individual, not in any transcendent or divine authority, they can be neither granted nor rescinded by religious authorities, and no country, culture or region can claim exemption from them by appealing to holy texts, a history of oppression, revered traditions or because rights “somehow embody ‘Western’ prejudice and hegemony.”

In this light, the search for a kinder, gentler version of Islam—or, for that matter, of any religion—as the basis of rights is “doomed” to failure; for Halliday, the question of a religion’s content was entirely irrelevant. “Secularism is no guarantee of liberty or the protection of rights, as the very secular totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century have shown,” he argued. “However, it remains a precondition, because it enables the rights of the individual to be invoked against authority.… The central issue is not, therefore, one of finding some more liberal, or compatible, interpretation of Islamic thinking, but of removing the discussion of rights from the claims of religion itself.… It is this issue above all which those committed to a liberal interpretation of Islam seek to avoid.” The issues that Halliday raised in 1996 are by no means settled today, and they are anything but abstract; on the contrary, the Arab uprisings have forced them insistently to the fore. In Tunisia, Libya and Egypt, secularists and Islamists struggle over the role (if any) of Islam in writing new constitutions and legal codes; at the United Nations, new leaders such as Egypt’s Mohamed Morsi and Yemen’s Abed Rabbu Mansour Hadi argue that the right to free speech ends when it “blasphemes” against Islamic beliefs.

But more than a defense of secularism is at stake here. Halliday argued that the very idea of a unitary, reliably oppressive behemoth called the West—on which so much antiimperialist and “dependency” theory rested— was false. “Far from there having been, or being, a monolithic, imperialist and racist ‘West’ that produced human rights discourse, the ‘West’ itself is in several ways a diverse, conflictual entity,” he wrote. “The notion of human rights was not the creation of the states and ruling elites of France, the USA, or any other Western power, but emerged with the rise of social movements and associate ideologies that contested these states and elites.” The West embodied emancipation and oppression, equality and racism, abolitionism and slavery, universalism and colonialism. Political theories and practices that refuse to acknowledge this—proudly brandishing their “anti-Western” credentials—will be based on the shakiest foundations.

* * *

The argument between advocates of the concept of “Orientalism,” put forth most famously by Edward Said, and its critics—often associated with the scholar Bernard Lewis—was close to Halliday. Lewis had been a mentor of his at SOAS, and one he admired; Said, whom Halliday described as “a man of exemplary intellectual and political courage,” was a friend. (Though not forever: Said stopped talking to Halliday when the two disagreed on the first Gulf War.) Yet on closer look, Lewis and Said shared an orientation: both had rejected a materialist analysis of Arab (and colonial) history and politics in favor of a metadebate about literature. “For neither of them,” Halliday argued, “does the analysis of what actually happens in these societies, as distinct from what people say and write about them…come first.” Increasingly, Halliday would regard the Orientalist debate as one that deformed, and diverted, the discipline of Mideast studies and helped to foster a vituperative atmosphere.

Said had argued that, for several centuries, British and French writers, statesmen and others had created a static, mythical Middle East—sometimes romanticized, sometimes denigrated, always objectified— as part of an unwaveringly racist, imperialist project. (Indeed, Said’s book has turned the word “Orientalist,” which used to refer to scholars of the Muslim, Arab and Asian worlds, into a term of opprobrium.) With sobriety and respect, Halliday considered and, in the end, devastatingly refuted the theory’s major tenets. With its sweeping, all-encompassing claims, he argued, the concept of Orientalism was a form of fundamentalism: “We should be cautious about any critique which identifies such a widespread and pervasive single error at the core of a range of literature.” It was based on a widely held yet entirely unsubstantiated belief that Europe bore a particular hostility toward the Muslim world: “The thesis of some enduring, transhistorical hostility to the orient, the Arabs, the Islamic world, is a myth.” It was undialectical, ignoring not only the myths that Easterners projected against the West—ignorant stereotyping is, if nothing else, a busy two-way street—but the ways the East itself reproduced the tropes of Orientalism: “A few hours in the library with the Middle Eastern section of the Summary of World Broadcasts will do wonders for anyone who thinks reification and discursive interpellation are the prerogative of Western writers on the region.” In fact, Islamists can be among the greatest Orientalists, for many insist on an Islam that is eternal, opaque and monolithic.

Most of all, though, Halliday questioned the assumption that the presumably impure origin of an idea necessarily negates its truth value. “Said implies that because ideas are produced in a context of domination, or directly in the service of domination, they are therefore invalid.” Carried to its logical conclusion, of course, this would entail a rejection of modernity itself—from its foundational ideas to its medical, technological and scientific advances—for all were produced “in the context of imperialism and capitalism: it would be odd if this were not so. But this tells us little about their validity.” (“Antiimperialism” and “self-determination” are, we might note, Western concepts, just as penicillin, the computer, the machine gun and the atom bomb are Western inventions.) And he questioned a key tenet of postcolonial studies and postcolonial politics: that the powerless are either more insightful or more ethical than their oppressors. “The very condition of being oppressed…is likely to produce its own distorted forms of perception: mythical history, hatred and chauvinism towards others, conspiracy theories of all stripes, unreal phantasms of emancipation.” Suffering is not necessarily the mother of wisdom.

But if Halliday was a foe of the simplicities of Orientalism, he was equally opposed to Samuel Huntington’s notion of “the clash of civilizations”—a concept that, he pointed out, was as beloved by Osama bin Laden as by neoconservatives—and to essentialist fictions like “the Islamic world” and “the Arab mind.” (On this, he and Said certainly agreed.) More than fifty diverse countries contain Muslim majorities; the job of the intellectual—whether located inside or outside the region—was to specify and demystify rather than deal in lumpy, ignorant generalities. “Disaggregation and explanation, rather than invocations of the timeless essence of cultures,” was the Mideast scholar’s prime task, Halliday insisted. He rejected mystified concepts such as Islamic banking and Islamic economics (“Anyone who has studied the economic history of the Muslim world…will know that business is conducted as it is everywhere, on sound capitalist principles”); the Islamic road to development (Iran’s economy was “a perfectly recognisable ramshackle rentier economy, laced with corruption and inefficiency”); and Islamic jurisprudence (Sharia, Halliday noted, has virtually no basis in the Koran). Echoing E.P. Thompson, Halliday argued that much of what passes for the ancient and authentic in the Islamic world—including Islamic fundamentalism itself—is the creation of modernity, and can be productively analyzed only within a political context.

Halliday proposed that even the Iranian Revolution—with its mobilization of the masses, consolidation of state power, repressive security institutions and attempts to export itself—had, despite its peculiar ideology, reprised the basic dynamics of modern, secular revolutions: “not that of Mecca and Medina in the seventh century but that of Paris in the 1790s and Moscow and St Petersburg in the 1920s.” Islam, Halliday insisted, could not explain the trajectory of that revolution or, for that matter, the politics of the greater Middle East.

Was Halliday right? Surely yes, in his refusal of essentialist fantasies and apolitical thinking. And in some ways, the Arab uprisings have confirmed everything for which he had spent a lifetime arguing. Here were populist movements demanding democratic institutions, transparency, and an end to tyranny and corruption; here were hundreds of thousands of protesters demanding entry into the modern world, not its negation; here was the assertion of participatory citizenship over passive subjecthood. Yet the subsequent trajectory of those initial revolts also proved him wrong: nowhere else in the contemporary world have democratic elections led to the triumph of religious parties. Nowhere else do intra-religious schisms result in the widespread carnage of the Shiite-Sunni split. Nowhere else do the democratic rights to freely speak, publish and create collide with strictures against blasphemy—even among some presumed democrats. Nowhere else does the fall of dictatorship and the assertion of self-determination translate, so quickly and so often, into attacks on women’s equality. “Islam explains little of what happens” in Turkey and Pakistan, Halliday wrote in 2002, and he believed this to be true of the region as a whole. Yet I doubt there are many Turks or Pakistanis (or, for that matter, Iranians, Egyptians, Algerians, Lebanese, Afghans, Saudis or Yemenis) who would agree. Can they all be the victims of false consciousness?

Here, I think, lies the problem: in his fight against lazy generalizations about Islam and its misuse as a univocal explanation, Halliday sometimes sought to scrub away, or at least radically minimize, Islam itself, as was demonstrated by his early book on Iran. It is almost as if he—the confirmed skeptic, the lover of reason, the staunch secularist, the self-proclaimed bani tanwir (“child of enlightenment”)—could not quite believe in religion as a force unto itself, and an astonishingly powerful one at that. “What people actually do,” he wrote in 2002, “is not determined by ideology.” This is, we might note, a classic Marxist position, in which the “superstructure” of belief is subsumed beneath class and politics. Yet Halliday’s erstwhile Iranian friend Muhammad— and, indeed, so many of the events that Halliday himself witnessed—told him otherwise. And as organizations as diverse as the Nazi Party and Al Qaeda have shown, rational, politically focused strategies and utterly lunatic ideologies can, alas, coexist.

* * *

In the immediate aftermath of September 11, Halliday was clear about several points: that the attacks would resonate throughout global politics, changing them for many decades to come; that Al Qaeda was a “demented” product not of ancient Islam but of modernity, and represented “the anti-imperialism of racists and murderers”; and that terrorist violence “from below,” though not directly caused by poverty, could not be severed from the grotesque inequalities that international capital had created. In 2004, he wrote, “The central challenge facing the world, in the face of 9/11 and all the other terrorist acts preceding and following it, is to create a global order that defends security while making real the aspirations to equality and mutual respect that modernity has aroused and proclaimed but spectacularly failed so far to fulfil.” This was not a question of either/or, but of and/ and. Ever the dialectician, Halliday observed that imperialism and terrorism are hardly antagonists; rather, they share a “central arrogance,” each “forcing their policies and views onto those unable to protect themselves, and proclaiming their virtue in the name of some political goal or project that they alone have defined.” And he noted with anger and sorrow how terrorism—which has killed far more people in the East than in the West —had transformed millions of people throughout the world into bewildered bystanders, creating an internationale of fear.

Afghanistan had been one of Halliday’s key areas of study, and he repeatedly pointed to several crucial facts that many Americans still resist understanding. Al Qaeda did not spring out of nowhere, much less from its beloved eighth century. It was Ronald Reagan’s arming of the anti-Soviet guerrillas— even after the Soviet pullout in early 1989, when Kabul’s communist government still stood—that was instrumental in creating the Islamist militias and warlord groups, some of which transformed themselves into the Taliban and Al Qaeda. Thus had our fanatical anti-communism led to the empowerment of “the crazed counter-revolutionaries of the Islamic right.” For Halliday there was no schadenfreude in this, no gloating, no talk of chickens coming home to roost or of blowback (a concept that fundamentally misunderstands— and moralizes—historic causation: was Sobibor the blowback from the Versailles Treaty?). But he insisted, rightly, that the crisis of 9/11 could not be understood, much less successfully confronted, in the absence of engaging this “policy of world-historical criminality and folly.”

Halliday had supported the US overthrow of both the Taliban and Saddam (in addition to military intervention against Saddam in the first Gulf War, and against Milosevic in Bosnia and Kosovo). He criticized three tendencies of the post-9/11 world with increasing dismay, though not quite despair: the retreat into rabid nationalism in both East and West; the Bush administration’s conduct in Iraq and in international affairs generally (“The United States is dragging the Western world…towards a global abyss,” he warned in 2004); and the left’s romance with jihad, especially in relation to Hamas, Hezbollah and the Iraqi “resistance.” And indeed, it was somewhat shocking to read Tariq Ali, writing in the New Left Review in the especially bloody year of 2006, exulting in the rise of “Hamas, Hizbollah, the Sadr brigades and the Basij.… A radical wind is blowing from the alleys and shacks of the latter-day wretched of the earth.” Or, more recently, to find his colleague Perry Anderson arguing that the “priority” of Egypt’s new, post-Mubarak government should be to annul the country’s “abject” peace treaty with Israel as a way of recovering “democratic Arab dignity.” Rip van Winkle socialism, indeed.

After September 11, Halliday focused much of his intellectual energy on explaining the ways the attacks and their serial, convulsive aftermaths were decisively changing international relations. While classic internationalism—in the sense of humane solidarity with the suffering of others—was imperiled, a kind of militarized internationalism was on the rise. Conflicts that had been relatively distinct, except on a rhetorical level, had become ominously entwined and the ante of violence—especially against civilians—cruelly raised. “Events in Lebanon and Israel, Iraq and Afghanistan, Turkey and Libya are becoming comprehensible only in a broader regional and even global context,” he wrote in 2006. This new dispensation, which he dubbed the “Greater West Asian Crisis,” represented a struggle for political supremacy in a region that now included not just the Arab world and Israel but also Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan, among others—including a plethora of volatile nonstate militias that are beholden to no constituencies and recognize no restraints. While some conflicts, such as Hezbollah versus Israel, might still be geographically confined, none could be politically or, because of the existence of transnational guerrillas, operationally confined. (Consider, for instance, the reported presence of Islamist fighters from Chechnya and Pakistan in Syria’s civil war.) Halliday warned that the resulting strife would be “more complex, multilayered and long-lasting than any of the individual crises, revolutions or wars that characterized the Middle East.” This was written six years ago; despite the hopefulness of the subsequent Arab Spring revolts, it would be difficult to dispute the alarming vision contained therein.

* * *

In the last decade of his life, Halliday turned, with an urgency both intellectual and moral, to the legacy of revolution in the twentieth century. His writings on this topic—precisely because they are the work of a writer deeply embedded in, and respectful of, the Marxist tradition and committed to the creation of what one can call, without cynicism, a more just world—are important for anyone who seeks to understand the history of the past century or the bewilderments of the present one. These essays make for painful reading, too—especially, I think, for leftists—in their willingness to question, and discard, comforting beliefs.

Halliday’s re-evaluation shared nothing with the smug rejection of revolution that had become so fashionable after 1989, or with the disparagement of communism as an “aberrant illusion.” To the contrary: “Millions of people struggled for and believed in this ideal,” he wrote in 2009. “As much as liberalism, communism was itself a product of modernity…and of the injustices and brutalities associated with it.” Nor had Halliday signed on to a celebration of the neoliberal world order: “The challenge that confronted Marx and Engels,” he wrote in 2008, “still stands, namely that of countering the exploitation, inequality, oppression, and waste of the contemporary capitalist order with a radical, cooperative, international political order.” Against flat-earthers like Thomas Friedman, he argued that the globalized world of the twenty-first century is more unequal than its predecessors.

And so the question of what is to be done still remained, but had to be faced with far more humility and critical acumen than ever before. If Halliday had little sympathy for talk of failed gods, he was equally impatient with the “vacuous radicalisms” and romanticized revival of tattered revolutionary ideals that permeate too much of the left, including—or perhaps especially— the anti-globalization and solidarity movements. The idealization of violence (“the second intifada has been a disaster for the Palestinians”); the eschewing of long-term political organizing in favor of dramatic but impotent protests; the failure to study the complex and blood-soaked trajectory of the past century’s revolutions; the Pavlovian identification with virtually every oppositional movement, regardless of its real political aims: all of this was, in Halliday’s view, the road to both tragedy and farce. “The anti-globalization movement has taken over a critique of capitalism without…reflecting on what actually happened in the 20th century,” he told an interviewer in 2006. “I read the stuff coming out of Porto Alegre and my hair falls out.”

For despite communism’s commitment to, and partial achievement of, certain economic and social values (including a planned economy, women’s equality and secularism)—values that, Halliday believed, must be preserved—its record of murder and authoritarianism could not be evaded. “The history of revolution in modern times is one not only of resistance, heroism and idealism,” he wrote in 2003, “but also of terrible suffering and human disaster, of chaos and incompetence under the guise of revolutionary transformation, of the distortion of the finest ideals by corrupt and murderous leaders, and of the creation of societies that are far more oppressive and inefficient than those they seek to overthrow.” What distinguished Halliday’s argument, however, was his insistence that these failures could not be rationalized as the divergence between “Marxist theory and communist practice”; twentieth-century revolution must be judged an inevitable failure, he concluded.

Thus Halliday rejected all “what if” forms of analysis: what if Lenin had not died, or Bukharin had come to power, or the Germans had turned to the left instead of to the Nazis. (These are questions that, I admit, still haunt me.) He did not believe that a more liberalized version of communism could have prevented the collapse of the Soviet Union. In his view, the key issue— one that many leftists want to avoid—is that communism’s “failure was necessary, not contingent.” This was because of four elements that were central to any communist program and, he argued, to Marxism itself: “the authoritarian concept of the State; the mechanistic idea of Progress; the myth of Revolution; and the instrumental character of Ethics.” (However, Halliday did not—at least as far as I know—ever adequately explain the relationship between the socialist tradition that grew out of the Enlightenment and the fatal flaws of communism.)