#Amery

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Vivien my secret changling

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

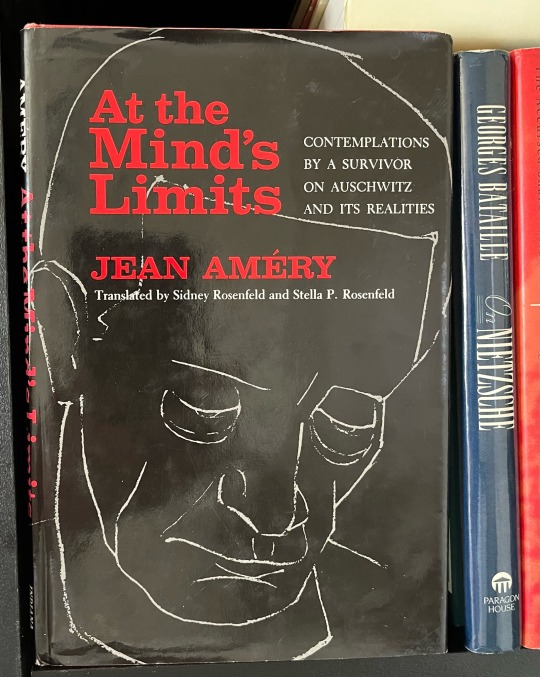

“The moment has come to make good a promise I gave. I must substantiate why, according to my firm conviction, torture was the essence of National Socialism - more accurately stated, why it was precisely in torture that the Third Reich materialized in all the density of its being. That torture was, and is, practiced elsewhere has already been dealt with. Certainly. In Vietnam since 1964. Algeria 1957. Russia probably between 1919 and 1953. In Hungary in 1919 the Whites and the Reds tortured. There was torture in Spanish prisons by the Falangists as well as the Republicans. Torturers were at work in the semifascist Eastern European states of the period between the two World Wars, in Poland, Romania, Yugoslavia. Torture was no invention of National Socialism. But it was its apotheosis. The Hitler vassal did not yet achieve his full identity if he was merely as quick as a weasel, tough as leather, hard as Krupp steel. No Golden Party Badge made of him a fully valid representative of the Führer and his ideology, nor did any Blood Order or Iron Cross. He had to torture, destroy, in order to be great in bearing the suffering of others. He had to be capable of handling torture instruments, so that Himmler would assure him his Certificate of Maturity in History; later generations would admire him for having obliterated his feelings of mercy.

Again I hear indignant objection being raised, hear it said that not Hitler embodied torture, but rather something unclear, "totalitarianism." I hear especially the example of Communism being shouted at me. And didn't I myself just say that in the Soviet Union torture was practiced for thirty-four years? And did not already Arthur Koestler . . . ? Oh yes, I know, I know. It is impossible to discuss here in detail the political "Operation Bewilderment" of the postwar period, which defined Communism and National Socialism for us as two not even very different manifestations of one and the same thing. Until it came out of our ears, Hitler and Stalin, Auschwitz, Siberia, the Warsaw Ghetto Wall and the Berlin Ulbricht-Wall were named together, like Goethe and Schiller, Klopstock and Wieland. As a hint, allow me to repeat here in my own name and at the risk of being denounced what Thomas Mann once said in a much attacked interview: namely, that no matter how terrible Communism may at times appear, it still symbolizes an idea of man, whereas Hitler-Fascism was not an idea at all, but depravity. Finally, it is undeniable that Communism could de-Stalinize itself and that today in the Soviet sphere of influence, if we can place trust in concurring reports, torture is no longer practiced. In Hungary a Party First Secretary can preside who was himself once the victim of Stalinist torture. But who is really able to imagine a de-Hitlerized National Socialism and, as a leading politician of a newly ordered Europe, a Röhm follower who in those days had been dragged through torture? No one can imagine it. It would have been impossible. For National Socialism - which, to be sure, could not claim a single idea, but did possess a whole arsenal of confused, crackbrained notions - was the only political system of this century that up to this point had not only practiced the rule of the antiman, as had other Red and White terror regimes also, but had expressly established it as a principle. It hated the word "humanity" like the pious man hates sin, and that is why it spoke of "sentimental humanitarianism." It exterminated and enslaved. This is evidenced not only by the corpora delicti, but also by a sufficient number of theoretical confrmations. The Nazis tortured, as did others, because by means of torture they wanted to obtain information important for national policy. But in addition they tortured with the good conscience of depravity. They martyred their prisoners for definite purposes, which in each instance were exactly specified. Above all, however, they tortured because they were torturers. They placed torture in their service. But even more fervently they were its servants.” - Jean Améry, ‘At the Mind's Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities’ (1966) [pages 30, 31]

#amery#améry#jean amery#jean améry#at the mind’s limits#third reich#wwii#holocaust#torture#fascism#hitler#mengele

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

ᵖʰᵒᵗᵒ ᵇʸ ⁻ ᶜʰʳⁱˢ ᶜᵃˢᵒⁿ ᵉᵈⁱᵗ ᵇʸ ⁻ ᵃ ᵐ ᵉ ʳ ⁱ ˢ ʰ ᵘ ᵍ ᵉ ⁽ᵗʳⁱᶜᵉ⁾

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baby in Vain (Escho, Copenhagen) are back in Berlin, playing a co-headline with Amery (Night School, Montreal) on Oct 2 at 8MM.

Please come.

0 notes

Text

Amery, live at The Monarch Tavern in Toronto, August 2024

instagram

0 notes

Text

Amery - Hotwire The Nite

0 notes

Text

PONLE PLAY | 2024 - 011

#ponle play#gastrico.tv#podcasts#music podcast#new music#musica nueva#music#musica#caribou#porches#amery#architects#belle and sebastian#Spotify

0 notes

Audio

Listen/purchase: Continue As Amery by Amery

0 notes

Text

ameri

#ultrakill#ultrakill gabriel#gabriel ultrakill#gabriel#v1 ultrakill#ultrakill council#v1#ultrakill v1#virtue ultrakill#ultrakill virtue#ok there's too much of them#myart#song is ameri - nilfruits#I mostly wanted to study the mv but i wish i had enough time to do a longer one </3

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Amerie & Malakai First and Last Interactions

#heartbreak high#heartbreak high netflix#heartbreakhighedit#amerie wadia#malakai mitchell#amerie x malakai#malakai x amerie#my edits

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

malakai fighting demons and the demons are bisexuality and wanting to fuck a blonde guy

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

“What, for example, was the attitude of the intellectual in Auschwitz toward death? A vast, unsurveyable topic, which can be covered here only fleetingly, in double time! I will assume it is known that the camp inmate did not live next door to, but in the same room with death. Death was omnipresent. The selections for the gas chambers took place at regular intervals. For a trifle prisoners were hanged on the roll call grounds, and to the beat of light march music their comrades had to file past the bodies - Eyes right! - that dangled from the gallows. Prisoners died by the score, at the work site, in the infirmary, in the bunker, within the block. I recall times when I climbed heedlessly over piled-up corpses and all of us were too weak or too indifferent even to drag the dead out of the barracks into the open. But as I have said, people have already heard far too much about this; it belongs to the category of the horrors mentioned at the outset, those which I was advised with good intentions not to discuss in detail.

Here and there someone will perhaps object that the front-line soldier was also constantly surrounded by death and that therefore death in the camp actually had no specific character and posed no incomparable ques: tions. Must I even say that the analogy is false? Just as the life of the front-line soldier, however he may have suffered at times, cannot be compared with that of the camp inmate, death in battle and the prisoner's death are two incommensurables. The soldier died the hero's or victim's death, the prisoner that of an animal intended for slaughter. The soldier was driven into the fire, and it is true that his life was not worth much. Still, the state did not order him to die, but to survive. The final duty of the prisoner, however, was death. The decisive difference lay in the fact that the front-line soldier, unlike the camp inmate, was not only the target, but also the bearer of death. Figuratively expressed: death was not only the ax that fell upon him, but it was also the sword in his hand. Even while he was suffering death, he was able to inflict it. Death approached him from without, as his fate, but it also forced its way from inside him as his own will. For him death was both a threat and an opportunity, while for the prisoner it assumed the form of a mathematically determined solution: the Final Solution! These were the conditions under which the intellectual collided with death. Death lay before him, and in him the spirit was still stirring; the latter confronted the former and tried - in vain, to say it straight off - to exemplify its dignity.

The first result was always the total collapse of the esthetic view of death. What I am saying is familiar. The intellectual, and especially the intellectual of German education and culture, bears this esthetic view of death within him. It was his legacy from the distant past, at the very latest from the time of German romanticism. It can be more or less characterized by the names Novalis, Schopenhauer, Wagner, and Thomas Mann. For death in its literary, philosophic, or musical form there was no place in Auschwitz. No bridge led from death in Auschwitz to Death in Venice. Every poetic evocation of death became intolerable, whether it was Hesse's "Dear Brother Death" or that of Rilke, who sang: "Oh Lord, give each his own death." The esthetic view of death had revealed itself to the intellectual as part of an esthetic mode of life; where the latter had been all but forgotten, the former was nothing but an elegant trifle. In the camp no Tristan music accompanied death, only the roaring of the SS and the Kapos. Since in the social sense the death of a human being was an occurrence that one merely registered in the so-called Political Section of the camp with the set phrase "subtraction due to death," it finally lost so much of its specific content that for the one expecting it, its esthetic embellishment in a way became a brazen demand and, in regard to his comrades, an indecent one.

After the esthetic view of death crumbled, the intellectual faced death defenselessly. If he attempted nonetheless to establish an intellectual and metaphysical relationship to it, he ran up against the reality of the camp, which doomed such an attempt to failure. How did it work in practice? To put it briefly and tritely: just like his unintellectual comrade, the intellectual inmate did not occupy himself with death, but with dying. Then, however, the entire problem was reduced to a number of concrete considerations. For example, there was once a conversation in the camp about an SS man who had slit open a prisoner's belly and filled it with sand. It is obvious that in view of such possibilities one was hardly concerned with whether, or that, one had to die, but only with how it would happen. Inmates carried on conversations about how long it probably takes for the gas in the gas chamber to do its job. One speculated on the painfulness of death by phenol injections. Were you to wish yourself a blow to the skull or a slow death through exhaustion in the infirmary? It was characteristic for the situation of the prisoner in regard to death that only a few decided to "run to the wire," as one said, that is, to commit suicide through contact with the highly electrified barbed wire. The wire was after all a good and rather certain thing, but it was possible that in the attempt to approach it one would be caught first and thrown into the bunker, and that led to a more difficult and more painful dying. Dying was omnipresent, death vanished from sight.

Now of course, no matter where you are, the fear of death is essentially the fear of dying, and Franz Borkenau's claim that the fear of death is the fear of suffocation holds true also for the camp. For all that, if one is free it is possible to entertain thoughts of death that at the same time are not also thoughts of dying, fears of dying. Death in freedom, at least in principle, can be intellectually detached from dying: socially, by infusing it with thoughts of the family that remains behind, of the profession one leaves, and mentally, through the effort, while still being, to feel a whiff of Nothingness. It goes without saying that such an attempt leads nowhere, that death's contradiction cannot be resolved. Still, the effort contains its own intrinsic dignity: the free person can assume a certain spiritual posture toward death, because for him death is not totally absorbed into the torment of dying. The free person can venture to the out most limit of thought, because within him there is still a space, however tiny, that is without fear. For the prisoner, however, death had no sting, not one that hurts, not one that stimulates you to think. Perhaps this explains why the camp inmate and it applies equally to the intellectual as well as to the unintellectual did experience agonizing fear of certain kinds of dying, but scarcely an actual fear of death. If I may speak of myself, then let me assert here that I never considered myself to be especially brave and probably also am not. Yet, when they once fetched me from my cell after I already had a few months of punitive camp behind me and the SS man gave me the friendly assurance that now I was to be shot, I accepted it with perfect equanimity. "Now you're afraid, aren't you?" the man - who was just having fun - said to me. "Yes," I answered, but more out of complaisance and in order not to provoke him to acts of brutality by disappointing his expectations. No, we were not afraid of death. I clearly recall how comrades in whose blocks selections for the gas chambers were expected did not talk about it, while with every sign of fear and hope they did talk about the consistency of the soup that was to be dispensed. The reality of the camp triumphed effortlessly over death and over the entire complex of the so-called ultimate questions. Here, too, the mind came up against its limits.

All those problems that one designates according to a linguistic convention as "metaphysical" became meaningless. But it was not apathy that made contemplating them impossible; on the contrary, it was the cruel sharpness of an intellect honed and hardened by camp reality. In addition, the emotional powers were lacking with which, if need be, one could have invested vague philosophic concepts and thereby made them subjectively and psychologically meaningful. Occasionally, perhaps that disquieting magus from Alemannic regions came to mind who said that beings appear to us only in the light of Being, but that man forgot Being by fixing on beings. Well now, Being. But in the camp it was more convincingly apparent than on the outside that beings and the light of Being get you nowhere. You could be hungry, be tired, be sick. To say that one purely and simply is, made no sense. And existence as such, to top it off, became definitively a totally abstract and thus empty concept. To reach out beyond concrete reality with words became before our very eyes a game that was not only worthless and an impermissible luxury but also mocking and evil. Hourly, the physical world delivered proof that its insufferableness could be coped with only through means inherent in that world. In other words: nowhere else in the world did reality have as much effective power as in the camp, nowhere else was reality so real. In no other place did the attempt to transcend it prove so hopeless and so shoddy. Like the lyric stanza about the silently standing walls and the flags clanking in the wind, the philosophic declarations also lost their transcendency and then and there became in part objective observations, in part dull chatter. Where they still meant something they appeared trivial, and where they were not trivial they no longer meant anything. We didn't require any semantic analysis or logical syntax to recognize this. A glance at the watchtowers, a sniff of burnt fat from the crematories sufficed.” (pages 15 - 19)

#amery#améry#jean amery#jean améry#at the mind’s limits#aushwitz#naziism#wwii#holocaust#bataille#georges bataille#nietzsche#books#bookshelf#library

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

You guys don’t understand…. Amerie never got the letter

#she doesn’t even know malakai wrote her a letter#actually sobbing#screaming crying gagging#NETFLIX I NEED ANOTHER SEASKN AND I NEED THEM TO BE OKAY#i am unwell#malakai mitchell#malakai x amerie#amerie#amerie wadia#malamerie#heartbreak high#hbh s2#hbh spoilers#heartbreak high season 2#PLEASE#i am a wreck#also FUCK rowan btw#rowan hate club

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Shameless/Limitless proudly presents Baby in Vain (Escho, Copenhagen) + Amery (Night School, Montreal) + Anemone (DJ), Oct 2 at 8MM.

Design comes courtesy of i: amerypress

Please come.

0 notes

Text

#Mairimashita! Iruma-kun#Welcome to the Welcome to Demon School Iruma-kun#Azazel Ameri#Orange Hair#Brown Eyes#Long Hair#Fox Girl#Fox Ears#Demon Girl#Choker#Collar

403 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let’s thank the media gods for heartbreak high having one of the only legit adoptions of a love triangle plot line, where all corners are actually connected

#heartbreak high#heartbreak high season 2#amerie wadia#malakai mitchell#bisexual#rowan#missy beckett#sasha so#darren rivers#quinni gallagher jones

2K notes

·

View notes