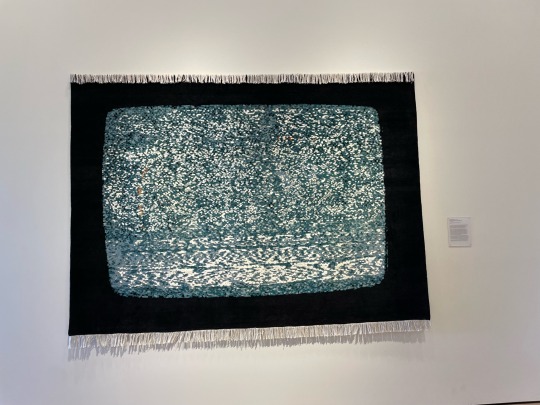

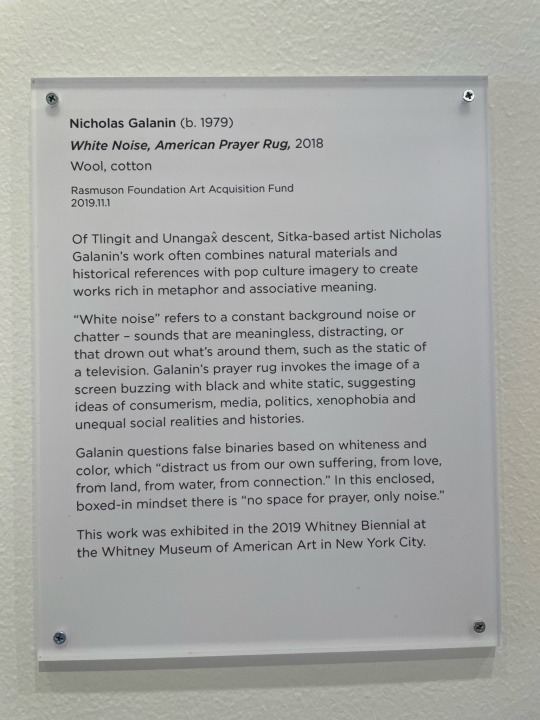

#American prayer rug

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In my neighborhood, everyone knows the corners where migrants wait for work. I live in Jackson Heights, Queens, where you can’t so much as step out the door without hearing a language other than English. Newcomers arrive in waves and settle like layers of sediment. On my block, there’s a contingent of elderly Polish ladies who have been living in their century-old co-ops for decades. A few blocks over in one direction is Calle Colombia, the official nickname for a corner of Eighty-second Street since 2009; countless times, I’ve walked past a street vender guarding tall stalks of sugarcane that she feeds through a machine to make juice. A few blocks over the other way, Bangladeshi men, their beards dyed orange, hawk prayer rugs and other religious goods from overturned milk crates on the sidewalk.

In recent years, the newest residents have come mostly from Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador. Such migrants line up each day at dawn at paradas—“stops”—hoping to get picked up for day jobs, like tiling, roofing, or painting. At least among Spanish speakers, paradas across New York are known by names that describe either their location or their purpose, such as “La de Limpieza” (“the Housecleaning One”) or “Home Depot.” How these spring up is less complicated than one might think—people learn to do whatever work is immediately available in the area. The main housecleaning parada is in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where women regularly find jobs in the homes of Hasidic Jews. In the leafy suburbs, there are more landscapers. In Flushing, close to a blocks-long stretch of Chinese-run kitchen-and-bathroom showrooms, there’s a street corner where the waiting Chinese men know how to install kitchens and bathrooms.

These word-of-mouth spots exist all over the city and in the surrounding suburbs, but nowhere are they more crowded than in Queens. The most popular construction parada near my apartment is technically in Woodside: “La 69” is a section of Sixty-ninth Street between Roosevelt Avenue and Broadway. For years, it was normal to see a few dozen men milling around there, but since 2022 hundreds of workers have been lining up in the mornings, including more women than ever. In the winter, nonprofits and church groups hand out jackets and hot breakfasts, and during the warmer months, at one end of La 69, some people sleep in a tiny plaza called Pigeon Paradise. Earlier this year, after the Trump Administration took power and began what it called the “largest deportation effort in U.S. history,” the numbers lessened for a while—people are terrified of ICE. A regular told me that, at least twice, an unmarked car pulled up to the parada, sending everyone running. But attendance at the parada has since returned to pre-Trump levels, despite the obvious risks. People have to work.

At La 69, there is hardly a system, but people are known to wait in certain areas according to their nationality: Mexicans and Guatemalans near the plaza, Ecuadorians and Colombians closer to Roosevelt Avenue. This could be because contractors prefer workers who hail from their home countries. One day last summer, a car pulled up to La 69. It was 10 a.m., which is around the time when people at the parada who haven’t been picked up yet think about going home. A crowd of Central Americans who were still waiting by Pigeon Paradise sized up the car as it slowed to a stop. When they realized that this meant a potential job, they swarmed. More than twenty men tapped on the windshield and called out day rates in Spanish: “Hundred fifty!” “Hundred forty!” “Hundred twenty!” One man agreed on a rate and jumped in. “Please,” the other men pleaded, as they do every day. “Just take one more.”

“Don’t worry too much about that,” the day worker said, in Spanish, as he took his seat and cracked open a can of Coke. He went by Pato, and he was twenty-seven. “I’ve been here eight years, but it’s never been as bad as this,” he said. There were just too many migrants, Pato said, and not enough jobs. Guys would work for anything nowadays.

We went to an apartment building nearby, where Pato spent several hours unscrewing shelves, pulling down old panelling, and organizing piles of debris. During a lunch break, Pato called his family back home—his parents still lived where he’d grown up, in the mountainous region of Chimaltenango, Guatemala. He spoke with them in Kaqchikel, his first language. Later, Pato told me that he was building a home there with the money he’d earned here. “Not even renovating—from scratch,” he said. Construction was coming along, and he hoped that in two or three years it might be ready, and that he could go back to finally start a family. “I’ll have my little house and my little land,” he said. “Now that’s what you call a dream. Here, there’s no life, only work.” He shook his head. “Work every day for eight years.”

As Pato kept on through the afternoon, he told me that he lived in a shared house in Corona, some forty blocks from La 69, with other migrants from Guatemala, Mexico, and Ecuador. He considered himself lucky: you can never be entirely sure about living with anyone besides your own family, he said, but he got along fairly well with the other tenants.

I’d heard about migrant houses like the one Pato described. Jackson Heights, Corona, and Elmhurst are full of them—you can identify them, in many cases, from the black garbage bags of personal belongings that have been stuffed onto metal balconies, for lack of interior space. These dwellings range from crowded but legitimate sublets to dangerous and unlawful boarding houses. At worst, they resemble modern-day tenements: entire families crammed into single bedrooms, with any common spaces subdivided by curtains or sheets or partition walls to allow for as many additional beds as possible. They are often dark, cramped, and poorly ventilated, with barely any privacy.

When the pandemic began, it quickly became clear which New York neighborhoods suffered the most from overcrowding, because of their overwhelmingly high rates of infection. (Central Queens became known as the “epicenter of the epicenter.”) In 2021, during Hurricane Ida, ten people living in unregulated basement apartments drowned in floodwaters. Last month, three men died when a fire broke out in an overcrowded home in Jamaica Estates where immigrant tenants lived; according to reports, the landlord lived in the back of the house and had long been renting out beds in small makeshift rooms divided by partition walls. Migrants in New York also whisper about an even cheaper arrangement: renting beds by the hour, alternating with others on a schedule. This is sometimes known in Spanish as a cama caliente, because the bed is still warm when a night-shift worker comes home in the morning to sleep.

In February, I paid a portion of one migrant’s rent for a bed in a two-family row house in East Elmhurst. I came and went as I pleased. Twelve migrants, all from Ecuador, lived on the first floor. The housemates told me that another large group lived on the second floor, though they weren’t allowed upstairs and rarely spoke with their neighbors. The house’s owners—an older woman and her adult son—lived in the basement.

The first floor had four bedrooms, each occupied by a young couple paying eight hundred to eleven hundred dollars a month; one of the couples shared their room with their five-year-old daughter, the only child in the house, and her uncle. In the narrow hallway, brown and red shower curtains cordoned off a fifth “room” that had twin beds (about seven hundred dollars each) placed so close together that they were almost touching; two single men slept there. Everyone shared a tiny bathroom, where a handwritten sign over the toilet read, in Spanish, “Gentlemen, aim well into the bowl. Thank you.”

A small kitchen was the sole common area. On one side, there were stained-wood cabinets, sticky from years of grease; along the other wall stretched a peeling bar counter with three chairs. There wasn’t enough space in the fridge and the cabinets for a dozen people’s food, so a lot of it stayed out in the open. On the bar counter sat three giant plastic tubs of rice. In some cupboards, unrefrigerated leftovers, such as grilled fish or cooked rice speckled with peas and carrots, were kept in covered pots and pans. Large bags of sugar sat unsealed on the tile floor, where cockroaches scurried around day and night.

On a freezing afternoon in mid-February, the entire house reeked of nail-polish remover. I entered the kitchen to find one of the residents, Lilia, getting a manicure. Supplies were strewn across the counter: brushes, cotton balls, bottles of acetone, various colors of polish. Two of Lilia’s housemates, Elisa and Mercy, were doing the nail painting—one woman on each hand. “We didn’t find work at the parada today, so we’re doing this,” Mercy told me, in Spanish, without taking her eyes off of the smooth coat of violet polish she was applying. “We have to pass the time somehow.”

“How fun,” I said, tentatively.

Lilia, a twenty-six-year-old, had long black hair and wore a T-shirt printed with the word “Hatteras”—the North Carolina beach town. (She’d never been there.) She had an air of confidence that set her apart from the other housemates. She slipped more English words into her Spanish sentences, even if incorrectly, and she’d been in the country for a year or two longer than most of the others. I was impressed that she had enlisted the two women to work feverishly on her nails. For a moment, I wondered if Lilia might actually be paying them. Then I realized that, whenever Elisa or Mercy finished a coat, they immediately scrubbed off the polish with acetone and started again. This was a training session. “I work in a spa, and the girls are hoping to get jobs there this summer,” Lilia explained. “I’m teaching them.”

Besides Lilia, the other housemates worked in construction. Those who lacked regular work set out for the paradas each morning before dawn. All the tenants were young, mostly between twenty-four and thirty, and over time they’d learned certain skills. Elisa and Mercy were mainly plumbers; Elisa’s husband, Iván, and her brother, Matías, were mostly roofers; others described themselves as Jacks-of-all-trades, capable of doing everything from house painting to Sheetrock installation. Lilia’s husband, Adolfo, placed himself in this category: “Anything to renovate a home—that’s what I know how to do.” A housemate named Anita had recently been finding work in the parking lot of a Home Depot in the Bronx. This led some of the others to start looking for gigs there, too.

This past winter, the housemates seldom went out. Day jobs were scarce, and it was too cold for volleyball and soccer, their favorite pastimes. Perhaps more important, the Trump Administration had them terrified. Nobody had any kind of legal status, and although none of them personally knew anyone who had been deported, rumors of mass arrests were enough to restrict their behavior.

Throughout January and February, the neighborhood’s streets were hushed, the Latin American restaurants emptier. Even before Trump’s Inauguration, a city campaign named Operation Restore Roosevelt had forced the removal of many unlicensed street venders from the area, compounding the eerie quiet. “We just stay at home,” Matías told me. They passed the time in their bedrooms, where they ate most of their meals and scrolled TikTok or watched TV. A bilingual sign hanging in the front entrance read “NOTICE: Door must remain locked at all times.” Even Yuri, Mercy’s five-year-old, played mainly inside now, running in and out of the room that she shared with her parents and her uncle.

On the day of the nail-painting marathon, Elisa and Mercy kept at it until well after dark, becoming dizzy from the pungent chemical odor that hung in the stale kitchen air. When they finally stopped, Lilia’s cuticles were stained black.

All over Queens, especially along major thoroughfares such as Roosevelt Avenue, posters in Spanish affixed to lampposts, walls, and train pilings advertise rooms and apartments meant for migrants. “I rent an apartment. 4 Bedrooms. Available Now. Living Room, Kitchen, Bathroom. 7-8 people”; “I rent rooms. Veronica. ‘No Papers.’ Kitchen OK.”

Some signs, taped over one another, specify if rooms are exclusively for women or couples, and if children are allowed. In recent years, real-estate agents and landlords have begun posting versions of these signs on Facebook groups and TikTok accounts, accompanied by photographs of bare mattresses in empty rooms. Migrants try to avoid real-estate agents—who typically charge three times one month’s rent for the first payment—and landlords who require documentation, especially income verification. (It’s illegal in New York City for landlords to require proof of immigration status when selecting tenants.) Among migrants who post online in search of housing, one of the most common phrases is “No Real State.” The best way to find housing, everyone said, is to hunt with people you already know.

Plenty of migrants have no choice but to depend on the ads. I recently came across a Facebook page called “Cuartos en renta Queens New York.” An affiliated website advertised apartments and single rooms for sublet in Queens. I messaged a number on WhatsApp and soon began texting with a broker named Renata, who wrote to me in Spanish, in all caps, and immediately began trying to persuade me to rent a room in a shared apartment in Woodside, two blocks from the 7 train.

“THEY ARE ASKING WHAT YOU DO FOR WORK AND WHAT COUNTRY YOU ARE FROM,” Renata texted. Just like some of the contractors hiring day workers, people frequently prefer to live with housemates from their own countries. Migrant communities in Queens have their own prejudices and stereotypes about one another. I’ve learned that many Ecuadorians think that Mexicans are drunks and Venezuelans are criminals; Mexicans and Guatemalans, in turn, often think of Ecuadorians as vagrants.

In the days and weeks that followed, Renata sent me photographs of small but neat-looking bedrooms across central Queens—mainly in Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, and Woodside. If I didn’t respond instantly, she called and texted multiple times. “YOU DON’T ANSWER,” she wrote. Finally, one night, we spoke on the phone. Renata told me that, for her clients, the ideal roommate spends most of his time out of the house and doesn’t cook much. Derechos a la cocina—rights to the kitchen—are a negotiated “amenity” in a shared house. You pay lower rent if you eat all your meals elsewhere.

In New York, one of the most expensive rental markets in the U.S., the reasons for sharing a space with so many others are almost always financial. Non-immigrants in New York may not understand how widespread and varied these arrangements are, especially in the outer boroughs. I met a Peruvian couple who were renting out their second bedroom, originally meant for their baby, to a single man. I visited a Mexican family in their Corona apartment, where a young relative who was new to the city slept on the couch. Janeth, an Ecuadorian woman living in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, told me that ten people were staying in her three-bedroom apartment. The landlord had recently raised the rent because of the number of tenants, Janeth told me, but otherwise didn’t bother them. (A landlord who allows overcrowding can be subject to fines, but the penalties per violation are relatively low.)

Plenty of these roommate arrangements are cordial. Everyone living at Janeth’s place ate dinner together at night. “There’s one gentleman from El Salvador living with us, and he’s gotten used to Ecuadorian food,” she said, adding that she sometimes lets fresh arrivals sleep in the living room for free.

Nevertheless, living in such tight quarters with so many other people can create severe tensions, particularly when everyone’s financial condition is precarious. Emperatriz Carpio, who manages the domestic-violence program at Voces Latinas, a nonprofit that serves migrants in the Jackson Heights area, told me that some of her most complicated cases arise in shared living spaces where victims lack the financial stability to move out. “I had one client who had been experiencing emotional and psychological abuse, and she still lived in the same house with her ex and his new partner,” Carpio said. “I believe the house had three rooms. She was in one room with her two kids, and the ex and his new partner were in another room.” Eventually, the new partner also brought her family into the third room. The client “mostly just stayed in her own room.”

Alcohol abuse, Carpio added, was another common problem. I thought of Pato, the Guatemalan man I’d met at La 69. After that work was done, he offered to return the next day with a companion to help haul out debris that he’d arranged in dusty heaps.

The following afternoon, Pato showed up with one of his housemates, María, a short Ecuadorian woman who wore leggings and a long-sleeved shirt. “Don’t worry, she’s strong,” Pato grinned, and María nodded. “Works harder than any man I’ve seen. She’s the strongest woman in Ecuador!” For the next two hours, they trudged up and down three flights of stairs, lugging hundreds of pounds of trash. María lifted the heaviest loads, navigating the stairs in determined silence. Later, on the drive back from the dump, the strongest woman in Ecuador spoke about the three children she’d left behind, more than a year earlier, in a coastal community overrun by drug cartels. “I’m doing this for them,” María said.

Pato opened his backpack and began drinking from a tall can in a brown paper bag. I smelled beer. He spoke longingly about Guatemala and the home he was building there. I eventually learned that, however lucky Pato felt about his housing situation in Corona, his housemates saw things differently. Not long after the dump run, his phone number went out of service, and María told me that she and the other tenants had kicked Pato out because he was drinking too much. When I finally tracked him down, six months later, he told me only that he’d had “personal problems” and was now living in another shared house in Elmhurst. I tried on several occasions to meet him again, but he always cancelled. He sometimes called me randomly; twice, he rang in the middle of the night. One morning at ten, I answered, and Pato’s speech was so slurred that I could hardly understand him.

The owners of properties where new migrants live are often immigrants themselves. Having arrived in New York a few decades earlier, perhaps from China, Ecuador, or the Dominican Republic, they settled in Queens and eventually achieved homeownership. Some, such as the owners of the East Elmhurst house, live in the basement, maximizing their own margins by renting the upper floors and minimizing liability by likewise living in the shadows. Other property owners rent out multiple units and reside elsewhere. In New York State, such people are known as “small landlords,” which means that they own no more than ten units. Many are middle class and view their rentals as necessary to offset high living costs.

From public records, I learned that the landlord of one crowded Corona migrant house—some of whose renters I’ve known for a while—owned at least four other properties across Queens and the Bronx. I couldn’t reach him directly, but one of his tenants told me that he was kind. He went by Jack, but she referred to him as El Chino. “El Chino treats us well,” she told me. “When he comes to the house, he asks us what’s bad, what’s not bad, and fixes things. At Christmas, he gives a toy to each of the kids.” Jack spoke only Chinese and English, she said, so her eldest daughter, who is eleven, translated his instructions—“how to put the bottles where the bottles go, the plastic where the plastic goes, the cardboard where it’s cardboard, the food where it’s food.” The tenant added that her daughter has a protocol for translating. “Mami, first I’ll listen, and then I’ll talk,” the girl likes to say.

Small landlords often know about overcrowding or other irregularities in their units, but they tend to ignore such matters as long as the rent is paid on time. Sometimes they just want to avoid conflict. Roy Ho, the president of the Property Owners Association of Greater New York, an organization that he founded, in 2020, to support Chinese small landlords, told me, “Landlords are aware that this problem exists. They trade stories. Their tenants might come in and say, ‘I’m renting for me, my wife, and my kid.’ Then, two months later, they go to fix the water or the plumbing and realize it’s so many more people.” Attempting to resolve the issue in court is a long, costly process that can end up being more of a financial risk than accommodating such renters. “They are reluctant to address the problem, even if they want to,” Ho said.

Hongyao Chen, a forty-one-year-old hospital worker based in Bayside, Queens, manages a two-family rental property in Maspeth for his elderly parents. He told me, “We were tenants ourselves in the beginning.” After the family of four moved to New York City from Fujian, China, in 2001, they shared a cramped one-bedroom apartment in Manhattan’s Chinatown for nearly seven years. “We were never late paying rent,” he said. “My parents worked super hard, and they encouraged us to finish school. Luckily, my sister and I were able to go to college.” In 2008, during the housing bubble, Chen’s parents bought the home in Maspeth for nine hundred and twenty-eight thousand dollars. To afford the mortgage, they rented out the second unit to the employees of a company based in Poland. Nine years later, they moved into a five-bedroom home in Bayside, along with Hongyao, his wife, and his children, and started renting out the entire Maspeth property to supplement their monthly Social Security income of about eight hundred dollars.

Chen told me that he and other small landlords he knew used to be quite content to accept tenants on the margins of the economy. “Some people maybe had a cash job, or didn’t have a stable job, but we had no problem renting to them,” he said. Chen also acknowledged that it was a common practice to rent out basement apartments at lower rates, mainly to undocumented tenants. Small landlords often consider undocumented renters to be among the most reliable tenants—because they don’t want to attract any legal trouble. “I know landlords who prefer undocumented tenants, for this reason,” Ho said. “The renters might not have a pay stub, but you know they will pay on time.”

For Chen’s family, everything changed during the pandemic. In New York State, eviction moratoriums lasted until early 2022, and in 2024 the state passed the Good Cause Eviction Law, which solidified eviction protections for renters. At the time, Chen’s father, who speaks no English, was still in charge of managing the Maspeth property. “He got scammed by a real-estate agent,” Hongyao Chen said. The agent, who he says was unlicensed, presented false proof-of-income documents, saying that a man would occupy a three-bedroom unit with his wife and two children. Nine people ended up living there, and they all stopped paying rent after the first month. “They slept in the living room—everywhere,” Chen said. The utility bills were extremely high. Chen felt that he had no recourse but to contact the police. The tenants eventually left. “My parents are talking about to transfer the ownership to me,” Chen texted me recently. “But I don’t want it. I hate being a landlord. That is more than a full time job and too much problem to be a landlord in nyc now. One day I want to sell it. Life is too short, I want a peaceful life.” (Chen’s sister, who is now married, at one point owned two rental properties of her own, on Staten Island. She has since sold them, he said.)

Such stories led Ho, a small landlord himself, to found his group as a way of organizing Chinese landlords in the city. Asian households have the highest rate of homeownership in New York City, partly because in immigrant communities there can be a lack of knowledge about securities such as stocks and bonds; a dearth of legal status can sometimes make utilizing such options difficult. “They may have a nail salon, a restaurant, retail, even a cash business—and a 401(k) is not accessible to them,” Ho told me. “Real estate is one of the only assets that they understand.”

Several activist groups in the Asian American community have since embraced the landlords’ cause, as part of organizing campaigns that often include unrelated issues popular with conservatives, such as opposition to affirmative action in college admissions. Ho told me, “The impression that you get is that Chinese landlords have become more vocal than they used to be, and they have become more vocal than other ethnic landlords.” He said that in New York the issue was a major driver of the community’s rightward shift in recent elections.

The resentments of immigrant landlords illustrate a broader paradox of current city politics: older immigrant communities, often inherently sympathetic to the challenges faced by new arrivals, are increasingly voting for politicians who espouse broadly anti-immigrant policies. Thomas Yu, the executive director of Asian Americans for Equality, a community-development organization with an office in Jackson Heights, told me, “There is a lot of anger at the city for how they feel like the legislators have left them behind.”

For more than twenty years, Yu has been looking to find solutions that work for both landlords and tenants in immigrant neighborhoods. In 2022, his group launched a pilot project providing grants for small landlords to renovate their units, thus allowing them to participate in a federal program in which tenants experiencing homelessness or abuse pay part of their rent with vouchers. (Although federal housing vouchers are generally unavailable to undocumented tenants, a new bill that has been introduced in the legislature in Albany would establish a housing-subsidy program for all renters across New York State, regardless of their immigration status.)

Yu found that, especially in the outer boroughs, small landlords were eager to accept the grants. “They needed that economic stability themselves,” he said. “There’s a sort of dogma in this world that all landlords are bad, and all tenants are free from fault. It’s very hard for people to be nuanced about it.” He worries that the pressures on small landlords will have a long-term impact on what he calls New York’s “cultural enclaves”—neighborhoods such as Jackson Heights, Chinatown, and the Lower East Side. “It forces a lot of these small owners to cash out. They’re, like, ‘I give up. I cannot sustain this.’ So they sell to bigger and bigger, and fewer and fewer, property owners.”

All the immigrant homeowners I spoke with emphasized that they did not want to make things harder for new migrants. But they insisted that the current system is failing, making it more difficult for small landlords to turn a profit and for tenants to find decent, affordable housing. An Iranian American landlord, whose family, seeking asylum during the Iran-Iraq War, brought him to New York as an infant, told me, “People have to do what they can to get by, just like my family did when we came to America.” Today, he manages six rental units in Queens. He lives in the basement of one of his multifamily properties in Astoria, where he has noticed issues of overcrowding in other homes nearby—including one multifamily dwelling that seems to house a phalanx of delivery drivers, who speed around the neighborhood on electric scooters. “I’m not here to pull up the ladder after making it off the lifeboat,” he noted, in an e-mail. “Still, it’s tough to see how this plays out for landlords and neighbors.”

Lilia and Elisa, two of the Ecuadorians in the East Elmhurst unit, are sisters-in-law. In 2023, they were living together with their husbands in a smaller Corona apartment when they learned that a group of relatives was headed to the U.S. border. The two women set out to find a bigger place where all of them could live. After work, they knocked on the doors of local houses that had “For Rent” signs in the windows.

They found the East Elmhurst house after a few weeks. They didn’t know to check the Department of Buildings website, where they would have learned that there were no certificates of occupancy registered for the property, and that there had been numerous complaints, filed over the past ten years, alluding to overcrowding and illegal conversions. (One complaint, filed in 2015, reads, “The house is subdivided in many rooms and is renting the rooms like a hotel.”)

The place was certainly tight, but the housemates were glad to keep costs down, even if it meant piling up on top of one another. Over time, more family members and friends arrived from Ecuador and occupied the remaining rooms. The two couples had learned some useful lessons in their first apartment together, where the landlord had lived in the same unit and enforced strict rules about kitchen rights and cleaning responsibilities. “It’s not good to live with strangers,” Lilia’s husband, Adolfo, told me. There were small things that they came to like about the new house, such as its proximity to a bus that took them to the parada La 69. Between the house and a neighboring one, there was a light well, and the housemates realized that in the winter they could use it as a second refrigerator, storing cartons of milk on the windowsill. They set house rules; no outside shoes were allowed indoors. Everyone wore black Nike or Adidas slides inside—or, in Mercy’s case, fluffy Teddy-bear slippers. Every day, a housemate was assigned to clean the kitchen and the bathroom and to empty the garbage. They called one another “neighbor,” and soon gave out nicknames. Adolfo, who constantly used sad-face emojis in the house group chat, was Tristito. Eduardo was lean and strong, and he wore tight-fitting shirts that showed off his muscles, so his nickname was Músculo. The house’s eldest resident, a thirty-seven-year-old single man named Efer, liked to play soccer, so he was called Messi.

But for the most part the house was uncomfortable. The absence of privacy was maddening, and the tenants were constantly smashing the cockroaches in the kitchen with their slides. “We have to live like this,” Matías told me. “This is the reality of being a migrant.” Everyone had kitchen rights—eleven adults to one four-burner stove—and this meant that they cooked meals in shifts beginning at 3 a.m. One of the residents had heard that New York City tap water was unsafe to drink, so for nearly two years they had needlessly bought cases of plastic water bottles from a market down the street.

Frustratingly, the house came unfurnished. On Junction Boulevard, the tenants found the basics—mattresses, bed frames, kitchenware—but the items cost them a relative fortune. They learned to be wary of Facebook Marketplace, where sellers frequently asked for payment up front and then disappeared; they were surprised that things like that happened in America. The tenants began to trust only one another as they established a routine that marked the beginning of their American Dream.

We talked a lot about dreams during the days I spent there. Most of the housemates had left everything behind; some had parted with their kids without knowing when, or if, they would see them again. Some wanted to leave the U.S. as soon as they had enough money to take substantial savings back with them. A few were considering staying for good. Mercy, whose daughter barely remembered Ecuador, said, “Ultimately, God will decide.” One day, in the kitchen, the tenants discussed the infamous case of a social-media personality who’d offered to help transport the body of a dead migrant back to Ecuador—and then allegedly ran off with all the money. I told the residents that a business near my apartment offered a similar service: funeral transports to Latin American countries. They looked horrified, and I sensed the years flashing before their eyes.

Since they’d come to New York, many of their dreams had begun to feel more abstract, as they focussed on the day-to-day difficulties of surviving. Músculo still had a vision, though: he wanted to become a licensed plumber, so that he could start his own business and work for himself. Some friends had recommended a vocational school in New Jersey. But the tuition—about four thousand dollars—was prohibitive. Mercy, his wife, told me that she was hoping to find an affordable after-school program for Yuri when she enrolled in kindergarten; currently, the couple was paying two hundred dollars a week for day care. Mercy didn’t realize that many public schools in the city provide after-school care for free. All Matías wanted was to get a tax I.D. number, so that he could find a regular job and stop waiting for contractors at the parada every day at dawn. He was trying to figure out how to do the necessary paperwork.

Lilia was determined to learn enough English to be able to communicate with her clients at the spa. Indeed, all the housemates had the goal of mastering basic English. Some showed me notebooks that they had filled up at free classes around the city; Lilia told me that she had trekked all the way to Long Island City for her first such class. Inside the notebooks, they had carefully written out Spanish phrases and their English equivalents, translated phonetically so that they could more easily pronounce the words. (“Uan mor taim pliz” for “One more time please”; “Si iu tumorou” for “See you tomorrow.”) But, for the most part, they had found these classes “boring” and far too advanced. They needed to focus on the basics (“I,” “you,” “we”) and the essentials (“room,” “bed,” “job”). The few words that they already knew were entirely trade-related: “roofing,” “plumbing,” “nails.”

Sometimes, late at night in the kitchen, when the housemates had returned from work, or from looking for work, and were cooking in shifts—two people at a time using the four burners, reheating rabbit or potato stew—they asked me to hold casual English lessons. They wanted to learn how to ask very specific questions.

Matías’s request: “Will you pay now, or later?”

Mercy’s: “Why are you discounting more from my paycheck than from hers?”

The only person who understood everything I said was Yuri, Mercy’s daughter. But the five-year-old, like so many immigrant children her age, was too shy to speak English in front of her parents. Of the adults, Lilia was the most engaged student. She said that her bosses at the spa spoke mainly Korean but some English—and that she would be grateful for any chance to communicate with them, even if her own English were limited to halting sentences. After a few days of lessons, she coined my house nickname: I became Profe, as in “teacher.”

A prize-ribbon sticker—the kind that kids get for winning first or second place in a school competition—was stuck to the door of the bedroom where Anita slept with her husband, Hernán. “I did my best!” it read. Yuri must have received the award at day care, I figured, unless it was a trace of previous tenants.

The housemates didn’t know anything about the prior residents. A migrant dwelling doesn’t tend to break up all at once, unless something happens with the landlord—an eviction notice, say, or the sale of a property. More often, people gradually trickle out, their rooms or beds given to new occupants, until the home’s population looks nothing like it did a year or two earlier. A tenant could become financially secure enough to rent on their own, or a job offer could lead them to another city or state. Perhaps, as with Pato, a dispute or a vice churns up enough trouble to warrant a less amicable departure. Now another possibility loomed large: ICE might pick someone up at work, and they’d never be heard from again.

Even though the East Elmhurst housemates lived in such intimate quarters, and some of them had been well acquainted back home, they kept a great deal from one another, especially when it came to matters such as money and their plans for the future. Why were some of the housemates unsure about exactly how much the group paid in total rent? (Adolfo collected the money, individually, at the start of each month.) At one point, Matías mentioned to me that he might be moving to another state. Through “some contacts” from La 69, he’d heard about a potential long-term job at a building in Kansas—or maybe it was Minnesota. “It would be for two years, wherever it is,” he told me. When I brought this up in the presence of some of the other housemates, he winced. “I didn’t tell them,” he revealed afterward.

The out-of-state opportunity fizzled, but Matías still contemplated leaving and finding a proper room that he could have to himself, instead of paying some seven hundred dollars a month to sleep in a bed inches from another tenant. He began an active search in mid-March, after his roommate, Messi, drank too much one Saturday morning and caused an altercation, breaking the front door of the house before passing out in his bed. A housemate called the police, but the officers didn’t come inside. Messi ended up paying about a thousand dollars to repair the door.

As with every dispute in the house, alliances formed over whether to kick Messi out. Some were vocal about wanting to expel him. Mercy, for her part, was upset that the incident had happened while Yuri’s cousin was visiting. The little girls had been scared. To my surprise, Matías was more willing to let Messi try to redeem himself. He noted that he and Messi had both left their wives and kids behind when they came to New York. “I understand that people are lonely. I really get it,” Matías told me. I thought, again, of Pato—the Guatemalan migrant whose own removal had seemingly led him to spiral—and considered how lonely he must have been, too. Living with many others was no antidote to emotional solitude.

Things blew over, and Messi stayed. Still, Matías said, the episode had made him intent on improving his own situation. He’d called numbers he’d seen on “For Rent” signs, and was considering some rooms a few blocks away. The only thing stopping him from moving out was that he didn’t want to leave his sister Elisa—the only family member he had nearby. “It’s a very, very difficult decision,” he told me. “I’m thinking about it a lot.”

As Matías considered his options, spring nudged Queens back to life, even if many people remained fearful of the intensifying deportation efforts. People have been flocking back to Thirty-fourth Avenue—the longest pedestrian street in the city. Children play in the shade of budding oak trees, and women from Mexico and Ecuador ring handbells and scoop ice cream from red carts. The remaining members of the neighborhood’s old Argentine and Uruguayan communities—who were prominent here before they moved out to the suburbs—share sips of mate on park benches. A group of older Bangladeshi and Nepalese residents gather for tea. In the evenings, an elderly husband and wife from Eastern Europe, who must be in their nineties, are wheeled out by their Caribbean aides to watch people stroll past. I’ve never seen the couple say a word to each other, but sometimes his finger grazes the side of her hand and, staring straight ahead, she smiles.

Everything in New York City is touched and shaped by these waves of people, not only those who came earlier but those who continue to arrive now. The idea of “making it” in the new country is inextricably linked to memories of the old country and those who remain there. In Queens, it’s virtually never a mistake to ask someone where they are originally from. People’s eyes will widen—with happiness or with sadness, depending on how long they’ve been away, but always with longing.

“Everyone has their own way to cope,” Matías told me in late March, in Corona. “I play volleyball.” He led me to three houses on the same block whose residents had constructed elaborate volleyball courts in their back yards, complete with spectator bleachers, floodlights, and tall mesh fences around the courts’ perimeters. At least one of the homes had been a “volleyball house” for more than twenty years, I learned, and had hosted generations of Ecuadorian and other Latin American migrants who gathered to play or watch anytime the weather was good. The people who lived there worked the courts, renting them out. Elderly Spanish-speaking women grilled chicken and pork off to the side, which they served in abundant portions alongside potatoes and rice; others sold hot and cold beverages and loose cigarettes, or worked as referees. The matches continued into the night, even when gusts of wind left us shivering in our windbreakers. The most competitive courts had dozens of onlookers. There, Matías and I ran into familiar faces: Iván, Hernán, and even Messi also hung out at the volleyball houses. The others, they told us, were still at work.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

How different cultures in ASOIAF view cats pt. 1

In our world, culture and religion shape how we view animals, and for this post, specifically cats. An example of how cats a view differently in cultures can be seen in Islamic cultures and Romani Cultures. Because cats clean themselves often, they are viewed as clean by Muslims and can be kept with the family. But for Romani, because of the Marime which states that the genital region is a source of impurity, a cat licking its own lower regions this becomes unclean. Roma still keep pets but they generally don’t let them sleep in their bed or lick them. This is all contrasted by American culture where a pet is viewed as a member of the family and will be referred to as the baby or child of their owners and is allowed to sleep in bed with them.

It’s so interesting and I want to expand this to how Westerosi people see cats and what types of cats they keep.

Dorne

Dorne takes a lot of inspiration from the Arabic would and I think it only makes sense for them to have a similar view of cats.

Cats keeping themselves clean makes them the perfect pets for humans. Cats are also known to pray to the seven if given a seat in a sept (cats love prayer rugs and it’s really cute). Both religious and hygienic, cats are viewed as more sophisticated than other animals and thus are kept closer by their families.

The salty Dornish are best known for their love of cats with many ancient breeds residing in their homes. The green orphans will sail with a cat or two and give them a fish from the days haul. Cats are also seen as omens of good fortune and many shops have a resident cat. Septa also keep cats control pests and because they will sleep at the feet of the seven when their statue is warm. The Turkish Van and Turkish Angora are both old and rare breeds of cats that would flourish in Dorne.

The Sandy Dornish also enjoy cats. Because cats naturally retain more water than dogs, they are fitted to live in the desert. These cats are some of the more wild ones as it’s common for the domestic cat to mix is wild cats. During harsh sandstorms, the Dornish will wrap the cats up in a blanket to protect them from the elements. Cats are known to love this and scene request it when their is no sand storm. The Savannah cat is a cross between wild Serval and a domestic short hair cat.

The stony Dornish are less attached to cats than the Sandy or salty Dornish. Every house hold does have a cat and it’s common for cats to sleep in the room of their favorite person, but the stony Dornish believe that cats have some impurity to them because they lick their own genitals. Families will often perform a cleaning ritual on their cats by wiping them down with a wet cloth to cleanse them of impurity. Cats in stony Dorne are slender and very angular, making them great at slipping through stony hills and along steep walls. The Cornish Rex and Devon Rex are popular cat breeds.

The Iron Islands

Cats were a big part of Scandinavian culture. The goddess Freya had her chariot pulled by Norwegian Forest cats (also called fairy cats) and it was custom for a groom to give his bride a kitten as a wedding gift. For Vikings specifically, cats were kept to control the pests on ship.

Because the Iron Islands is more based on mythical Viking culture than historical Scandinavian culture, we can have some fun with the cats.

Ships are a big part of the iron islands culture, so each ship should have a cat or two. Perhaps to “bless” a ship before it sets off, a kitten is brought into the ship and makes it their own. I also see the Ironman have a very communal ownership of the cats. Fisherman will give the cats some of their catch as part of a good luck ceremony and people will set up small cat houses for them. They could also view a cat staying with you as a sign of good luck. But because of Thai communal ownership, it would probably be taboo to try and keep a cat to yourself. The iron islanders see a cat as not belonging to a person but to a ship or island.

Types of cats I think the iron islanders would have. Because they’re kind of weird, I think some weird breeds would fit. The Selkirk Rex is known for playing in water, being loyal to their human, and also have some curly fur!

The Andal Kingdoms

The Andals had a similar relationship to cats that Europeans had before the Black Death. For the Andals, cats were viewed as mainly pest control for their farms and cities. People rarely tries to socialize kittens when born which led to people believing cats were naturally aggressive.

It wasn’t until Maesters discovered that cats help prevent the spread of disease by killing rats that cats became a more popular household animal.

The reach was the first kingdom to become very found of the cat. They were perfect help for their farms and perfect pest control for old town. Old Town holds a celebration of cats each year to thank them for preventing extreme disease outbreaks from happening in the city. The Redwyne family is famous for breeding Persians cats that resemble the pugs they breed with short faces. Rich families have a few Persian cats that they dress up as little lords and ladies as an extra show of wealth.

In the storm lands and riverlands, cats are seen as antithetical to the land. The kingdom’s natural wetness drives cats away. Fisherman are often at odds with local cat populations as they fight over fish. Despite the general population’s disinterest in cats, they are a common staple at inns and bars as they keep rats away from the straw and wheat. Patrons consider seeing a cat with folded ears as a lucky charm that their stay at the inn will be a pleasant one.

I reached the max amount of photos for this post so we will continue with westerlands, the vale, north, beyond the wall, and valyrians!

#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#asoiaf headcanons#cats in asoiaf#HotD#house of the dragon#hotd headcanon#cats in hotd#I love cats

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Palestine

The Israel-Palestine conflict is not complicated. People will try to make it look complicated in the hopes that you will be intimidated and back away without study, but the truth is simple and can be presented simply.

Israel has full control over Palestine's borders - and among the list of things they've banned from import is rebar, concrete, water pipe, and a significant number of consumer electronics.

They say it's because these things can be used for war. They can. But so can rations, clean water, clothes, and air. Banning these is not a military action - it is cruelty. And in the case of Israel, the goal is to make destruction a one way ratchet. Every building that is bombed, every road that breaks, every pipe that bursts - they cannot be fixed. Palestine cannot get better. It can only rot. And when it does not rot fast enough, it is broken.

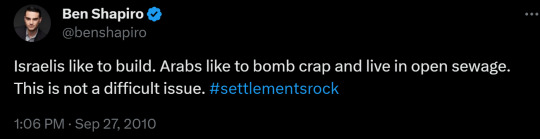

The people of Palestine know this. It's obvious. If you as an American don't talk about it, you'll get Ben Shapiro and his ilk all but bragging about it.

If you do talk about it, they'll accuse you of conspiracy. Demand to see credible sources - hoping that you'll forget that foreign journalists are illegal in Palestine as concrete, rebar, and water pipes.

I will not justify the crimes of Hamas. What they have done is unforgivable. But something like Hamas only happens when goading an entire civilization into becoming their worst selves. By condemning them to death by decay, then pointing and laughing. By cruelties beyond imagination.

Imagine being in this situation. Imagine that your water is not clean because a bomb hit your street twenty years and cracked both your sewage line and your water main. Now they leak and mingle. It stinks and you smell it. You see a hospital bombed, and the tragedy isn't just the people in the building - It's the fact that you can't build another. It's just gone. Everything that is taken from you is just gone. And as if that wasn't enough, your tormentors laugh at you. Mock you. Call you a savage that likes to like in open sewage. Call you an idiot that doesn't know how to build hospitals. Call you a zealot for the rage you feel when they shit on your prayer rug. A liar, because every crime you report remains unconfirmed, even as they lock the people who could confirm it out.

It would be very tempting to become a monster. And Israel banks on that too. They want more members in Hamas. It was Israel that raised the organization to such heights. And they did so because it justifies everything they do. Its mere presence in the region does wonders in delegitimizing the dream of a Palestinian state. Its violence is what gives Israel the thin veneer self defense. Hamas gets more members every time Israel drops a bomb, but Israel claims it needs more bombs to deal with the rise of Hamas. This cycle is not an accident. And with self reported casualty ratios of 2 civilians per 1 combatant, all Israel is really waiting for is 1/3 of the region to join. (Although human rights orgs have said the ratio is more like to 9 to 1.)

The world has spent decades watching a slow motion genocide. Now, it's not even slow. There are many things you can do to help Palestine, but the cheapest, easiest, and most effective actions are political. One man spending a day making bombs can undo the work of a hundred men spending a year laying brick. If all you do is keep track of the Zionists and make sure not to vote for them, you'll have done more than enough.

(And thanks for reading.)

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bless This Woman

So, @rom-e-o presented me, out of the blue and in the middle of the night, with this gorgeous piece of fan art😍😍😍:

And it inspired a wholesome and sweet little ficlet, surprise, surprise.

Btw: Yes, my Ebenezer grows his hair out long, if this is the first encounter with my work you've had. Also, in future, I plan to try and publish my Scrooge story, and Romey and I are kind of in cahoots with that; so we are trying out some slightly different character designs for Scrooge. That Netflix look is so specific, that I don't want to risk getting sued. This hairstyle is one we've decided on for him, as opposed to his lovely swoop.

It was a request Ebenezer had never been asked before; one he never thought to encounter. He wasn't what anyone would particularly call a "praying man", even now after he'd turned his life around for the good. But he'd be damned if he wouldn't become one: Because how could he possibly deny a woman as sweet and lovely as his Bess when she shyly asked him if he would pray over her that night before bed?

"Pray over you?" Ebenezer asked. Not in a condescending way, but certainly in a slightly confused way. He'd never heard that phrase for it before. Praying for someone, yes, but over someone? That was new to him.

Bess stood before him in her gauzy summer nightgown, the neckline slipped tantalizingly down to expose one speckled shoulder. She looked a little embarrassed, a slightly rosy tint in her cheeks making her freckles pop sharply--something her husband adored. "I-I know it sounds silly," she commented with a small, beseeching smile. She ducked her head and lowered her gaze in instinctive supplication, as her hands fiddling together at her waist. "But it's... it's something George used to do with Mama every night when he was home and... well... it's kind of something I've always hoped the man I love would do for me, too."

She looked back up at him, trying to judge his reaction to it. "Y-You don't have to if you don't want to," she assured him in a bit of a rush. "I just thought I'd ask. Doesn't hurt to ask, right?" She bit her bottom lip, hoping she hadn't just made herself look foolish in her husband's eyes.

She hadn't. And as far as Ebenezer was concerned, she never could.

Smiling softly at the woman, the Englishman stood from his seat beside the small fire, closing and placing his journal upon the mantelshelf as he did. Then he approached his wife, opening his arms to her. "It doesn't sound silly," he murmured softly, taking her into his embrace. He snuggled the American close, nuzzling into her thick, inky curls and kissing her crown. A satisfied purr nearly rumbled from his chest as Bess folded him into her arms and snuffled into the soft fabric of his nightshirt over his heart. "And, no, it never hurts to ask. I'd be happy to pray over you."

Bess looked up at him, eyes sparkling with happiness? "You would?" she asked, sounding rather relieved. "Truly?"

Her husband nodded as he kissed her hairline. "Of course." He touched his brow to hers and gave her a sheepish smile. "You might have to tell me how," he muttered. "I've never prayed over someone. Come to think, I can't recall when I last prayed for someone either. Not really. Not like you would in church."

Bess giggled as she nudged her nose along his. "This isn't exactly like that," she assured him. "It's not a big production full of show-boating piety the Bishop likes to make. This is more genuine and from the heart."

"I'm not even sure I know how to pray, to tell you the truth."

"George always told me that prayer is just talking to God. And the best way to talk to God is to talk to him as though He were a good friend."

He knew that was true. Still, Ebenezer felt a little out of his depth as he watched his beloved sink to her knees on the plush rug beneath their bed. Regardless, he knelt beside her. "H-How did George used to do this?"

Snorting, Bess gently pulled out of Ebenezer's embrace. She grabbed his hand and pulled him after her as she moved towards their marital bed. "Don't worry, I won't judge," she stated with a smirk and wink over her shoulder.

"I only caught him doing it a few times," Bess answered as she scooted into the man's side, ever desiring to be close as possible. She manages to twine her legs and feet with his. "But the few times I did, he always had his hands on Mama. On her shoulders, around her waist, hugging her--he was always touching her."

"Well, I certainly like the sound of that," Ebenezer remarked. Without a moment's hesitation, he stretched an arm across his wife's shoulders and pulled her close again. He pressed his lips to her brow. "Mmm, I love you," he murmured, the sentiment leaving him automatically.

Bess hummed as she leaned into his touch. "That love you feel--let that be what guides what you say," she quietly instructed.

In many ways, that didn't give Ebenezer a clue as to what to do at all. Yet in many others, it did.

The couple knelt there at their bedside in silence for a moment, the man absently stroking the woman's arms as she pressed into him. His mind, for a moment, felt like a wheel stuck in muddy clay. What should he say? How should he begin? He supposed the best way was just to start.

"Dear Lord, first and foremost, I would like to thank You for the wonderful woman beside me. I'm... not always certain what my convictions are in terms of faith and religion; one thing I do believe with certainty, however, is that You have placed my wonderful Bess beside me."

Bess dared to open her eyes and lift her gaze just enough to see her husband's down-turned face just above hers. She smiled in adoration at the man, marking how his long eyelashes brushed his cheekbones. Somehow, she managed to press a little closer to the man, nudging her head under his chin.

Ebenezer tightened his grip on her. "I come to You now, to pray for my Bess, Lord," he continued on, voice quiet but steady. He still didn't really know what he was doing, but that didn't seem to matter: He was focusing on his adoration for his wife, letting that guide him through what he wanted to say, and it was doing the trick. He was feeling much more confident in every passing moment. And, amazingly enough, even more in love with his mate.

"I pray that You watch over my beloved Bess, Lord. That you take her into Your arms and keep her safe throughout her life. I pray, if she can't find comfort and happiness in this world, that she is able to find it in You. I place her ultimate well-being in You, Lord, for I know there are things that I, as a mere man, cannot do to protect and comfort her."

Bess pressed her face into the open neck of Ebenezer's nightshirt and nuzzled at the hairy swathe of chest bared to her. On instinct she fluttered kisses to over sternum. "Oh, Darling...."

A slight heat bloomed across Ebenezer's face, but he didn't falter. "I ask You to continue to bless this woman with goodness you have granted to be in her life, Lord. And should it ever come to an end, I repay You grant her the strength to overcome challenges, just as You have granted her before. I ask You to continue healing and soothing the wounds and scars of Bess' past, and that You might bring her to realize that she is so much more than them--that they do not define her. I pray that she continues to discover herself in You, oh, Lord, and that she might draw great satisfaction and peace from that.

A lump suddenly formed in the man's throat and tears bit at his closed eyes. "I also pray that-" he cleared his throat as it croaked, "-that You might allow my lovely Bess to remain in my life, Lord. To remain by my side and help me continue to bear the burden of life. She is my greatest strength, my greatest happiness, my Brightness. And I ask with all my heart and soul that she might remain so, Lord. I promise to strive each day to be a better man, to be stronger and more virtuous, and to make this world a better, kinder place if You might allow Bess to remain in my life. I promise to cherish her with my entire being and do my best to care for her and make her happy all the days of my life."

Bess felt something warm and wet drip onto her cheek. Looking up again, she saw a single trickle of tears dripping down Ebenezer's cheek. Moved to wet eyes herself at the sight (her kind, sweet, tenderhearted man), the Yank reached up and gently dried them away. Then she kissed his stubbly chin. "Amen," she whispered. "That was beautiful. Thank you, my dearest moonlight."

Ebenezer gazed down at her with a trembling chuckle. "Not as beautiful at George's though, yes?" he rasped, looking a little shy.

Bess shook her head with a doting smile. "Better," she answered honestly. "Because it's my prayer. And it came from you and your heart. And I'll cherish it and carry it with me, until the day I die."

Genuine relief flooded through the gentleman. Bowing his head, he lifted a hand to his love's face and held her tenderly as he pulled her into a lingering kiss, one she eagerly returned.

"I'll do this again every night if you'll, please, just stay with me forever, Bess," Ebenezer whispered against her lips. His eyes were beseeching as he gazed deeply into hers. "Please."

Bess couldn't help the little smile that curled her lips, nor the little chuckle that left her in response to that promise. "Well, then, you're about to become a praying man, Ebenezer Charles. Because, while I can't speak for our Heavenly Father, I have no intentions of leaving your side. Not ever. Now, please, kiss me again."

And her husband, ever faithful and giving, did just that.

#scrooge 2022#netflix scrooge#scrooge a christmas carol#ebenezer scrooge#scrooge#fanfiction#scrooge x oc#bess scrooge#ebeness#ebenezer x bess

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, idea that I'm really excited about

Everyone is always talking abt an in-person temple for pagans but what if instead of a temple-temple, there was a museum-temple?

Hear me out bc I think this would be really cool.

Things the temple-museum would have:

Permanent exhibits including:

Outside land art similar to Sun Tunnels by Nancy Holt that line up with the solstices/constellations

Inside sky art for meditating similar to Skyspace by James Turrell (PLS look this one up, it's so pretty. The picture in the article doesn't do it justice)

A wall of prayers/manifestations/affirmations. Visitors write them on a post it or note card and pin it to the wall to make a collaborative exhibition like Post Secret at the Museum of Us

A small gallery with general overviews of popular pagan pantheons: Hellenic, Celtic, etc. This will include artifacts from those time periods either depicting the deities or how people worshiped them

A small gallery with historical witchcraft artifacts. This will include medieval European poppets, Copic love spell manuscripts, Chinese oracle bones, etc.

Rotating temporary exhibits including:

Witch trials from around the world (1400-present, bc they do still happen)

Paleolithic cultures: Venus of Wellendorf, Stonehenge, Cave paintings/music, the Lion-man ivory, etc

Did Christianity Steal From Paganism: yes… no… it’s complicated (basically the overlap between early Christianity and Roman paganism) This will include villa mosaics, sarcophaguses, layouts of early churches, etc

The Rise of Modern Occultism: Hilma af Klint, Carl Jung, surrealism, spiritualism, Wicca, etc

A series of exhibits celebrating closed practices: different indigenous religions, Voodoo, Hoodoo, etc (Very important: these will not be teaching those crafts, just giving them the same public platform/attention as open practices. Key word here is "celebrating." People who practice in those closed communities will be consulted)

How paganism is incorporated into Abrahamic religions: Judaism and paganism, Catholicism and paganism, etc (People who practice in those communities will be consulted)

Modern witchcraft, good or bad? So that would be New Age, the rise of consumerism, witchtok, etc

More in-depth focuses on different pantheons: Celtic, Slavic, Mesopotamian, Hellenic, etc

Historical witchcraft accusations and race: Mary Lewis, the New York City Panic of 1741, Ann Glover, etc

Regular people's (like you!) devotional art. The public will be encouraged to donate/create devotional art pieces. Be that visual media, performance art, video art, music, sculpture, photography, writing, etc. It'll really highlight all the different ways people are worshiping, the diversity in deities being worshiped, and how big our community is

An auditorium. This would be for concerts, festivals/ceremonies that are done inside, and guest speakers. Guest speakers would include academics like Malcolm Gaskill (English historian and author), Katherine Howe (American author), etc. as well as big name practicing witches/pagans.

A garden. I haven’t decided yet what kind but I’m debating between a rooftop garden like the MET, one behind the building but open to visitors, or an atrium like medieval European cloisters/monasteries (bc I love those). The garden would be for meditating, connecting to nature/the gods, feeding pollinators, protecting "creepy" insects like spiders or burrowing bugs (bug hotel?), and potentially -depending on what type of garden it is- housing wild birds in bird houses or bats in bat boxes. Also, it could be a good place for festivals/ceremonies that are done outside, concerts, or general get-togethers like altar piece swaps!

And an altar/worship space. Obviously. It wouldn't be a temple without it. I'm thinking it would be mostly a big empty room with chairs and rugs scattered about and an alcove in one wall for the altar. Inside the alcove will mostly be nonspecific religious objects like candles, nice fabrics, flowers, incense, etc . Visitors will be encouraged to bring their own small personal devotional tools (except candles/incense for fire safety reasons). That way they can pray to, appreciate, and connect to their own gods and the main altar doesn't leave anybody out; the main altar is more for ambience than specific worship.

Giftshop? I'm not sure about this one yet bc it feels wrong to have a gift shop in a temple, but most museums, even small ones, have gift shops. It could have fresh herbs from the garden, candles, and local artists' art like prints, stickers, jewelry, etc. All at a reasonable price ofc (I hate overpriced museum giftshops more than anything else in the world... except overpriced museum tickets)

In terms of funding, museums get more government funding than churches, but they do have to pay taxes churches don't. I was thinking of generally modeling it after the Museum of Us in San Deigo; they let their employees pick the holidays they take off so they can each adhere to their personal religious practice, start paying them at $22 an hour with built in raises each year, and good insurance. They have done an amazing job, way better than any big museum, at collaborating with communities from all over the world to either give back artifacts in their collections or closely work with them to reframe how the artifact is presented/stored. They also don't charge for tickets, memberships, school trips, or basically anything except the giftshop. But that means they rely heavily on donations which may not work as well for a museum that's just starting out. Idk, this is all hypothetical rn.

The pillars the museum-temple would stand on are worship, education, and community.

I feel like teaching people about the history of these practices is super important and isn't smth that everybody bothers to learn or has correct information about. (And I'm a huge history/museum nerd if you can't tell lol)

I'm actually really excited about this lol

#i'm getting my degree in art history and museum studies if u can't tell lol#i've done two internships at the American Musuem of Natural History in NYC and i'm set up to do a third next summer#and i'm close w the Director of the Museum of Us and have been invited to work with them in the future (i admire them so much)#so the idea of running a museum that's also a place where ppl can worship and build community is INCREDIBLE to me#but it would take a lot of money. funding is what i'm most concerned about rn#most museums have a bord of directors where they get abt 60% of their funding from but idk who would want to sponsor smth like this#hellenic polytheism#witchcraft#paganism#paganblr#pagan community#polytheism#pagan temple#witchblr#witch community

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

RWRB Quotes that speak to me on this really fucking shitty day

Hey, have I told you lately that you're brave? I still remember what you said to that little girl in the hospital about Luke Skywalker:"He's proof that it doesn't matter where you come from or who your family is." Sweetheart, you're proof too.

It is, indeed, bullshit. It's all I can do not to pack a bag and be gone forever. Perhaps I could live in your room like a recluse. You could have food sent up for me, and I'll be lurking in disguise in a shadowy corner when you answer the door. It'll all be very dreadfully Jane Eyre

I'm afraid, though, I'm stuck here. Gran keeps asking Mum when I'm going to enlist, and did I know Philip had already served a year by the time he was my age. I do need to figure out what I'm going to do, because I'm certainly closing in on the end of what's an acceptable amount of time for a gap year. Please do keep me in your- what is it American politicians say?-thoughts and prayers

It drives me nuts sometimes that you don't get to have more say in your life. When I picture you happy, I see you with your own apartment somewhere outside of the palace and a desk where you can write anthologies of queer history. And I'm there, using up your shampoo and making you come to the grocery store with me and waking up in the same damn time zone with you every morning.

Have you ever had something go so horribly, horribly, unbelievably badly that you'd like to be loaded into a cannon and jettisoned into the merciless black maw of outer space?

I wonder sometimes what is the point of me, or anything. I should have just packed a bag like I said. I could be in your bed, languishing away until I perish, fat and sexually conquered, snuffed out in the spring of my youth. Here lies Prince Henry of Wales. He died as he lived: avoiding plans and sucking cock.

Specifically, we were discussing enlistment, Philip and Shaan and I, and I told Philip I'd rather not follow the traditional path and that I hardly think I'd be useful to anyone in the military. He asked why I was so intent on disrespecting the traditions of the men of this family, and I truly think I dissociated straight (ha) out of the conversation, because I opened my blasted mouth and said, "Because I'm not like the rest of the men of this family, beginning with the fact that I am very deeply gay, Philip."

Once Shaan managed to dislodge him from the chandelier, Philip had quite a few words for me, some of which were "confused or misguided" and "ensuring the perpetuity of the bloodline" and "respecting the legacy." Honestly, I don't recall much of it. Essentially, I gathered that he was not surprised to discover I am not the heterosexual heir I'm supposed to be, but rather surprised that I do not intend to keep pretending to be the heterosexual heir I'm supposed to be.

Sometimes I imagine moving to New York to take over launching Pez's youth shelter there. Just leaving. Not coming back. Maybe burning something down on the way out. It would be nice.

9. How hard you try

10. How hard you've always tried.

11. How determined you are to keep trying.

give yourself away sometimes, sweetheart. there's so much of you.

They all turn to look at him, and Alex feels a wave of something so much bigger than himself sweep over him, like when he was a child standing bowlegged in the Gulf of Mexico, rip-tide sucking at his feet. A sound escapes his throat uninvited, something that he barely even recognizes, and June has him first, then the rest of them, arms and arms and hands and hands, pulling him close and touching his face and moving him until he's on the floor, the goddamn terrible hideous antique rug that he hates, sitting on the floor and staring at the rug and the threads of the rug and hearing the Gulf rushing in his ears and thinking distantly that he's having a panic attack, and that's why he can't breathe, but he's just staring at the rug and he's having a panic attack and knowing why his lungs won't work doesn't make them work again.

He's faintly aware of being shifted into his room, to his bed, which is still covered in the godforsaken fucking newspapers, and someone guides him onto it, and he sits down and tries very, very hard to make a list in his head.

One.

One.

One

Once upon a time, there was a young Prince, who was born in a castle. And there had never been a prince quite like him: he was born with his heart on the outside of his body.

Whereas the other princes and noble children could withstand the slings and arrows of childhood, the Prince felt everything acutely. Everything seemed to touch and threaten his unprotected heart.

Oh for Christ sake Alex, for once! I wish you could see me for who I am and not who you want me to be! Sometimes, I don't think you know me at all!

I wasn't raised by a loving, supportive family like you were!

Nothing will ever happen to you.

I don't want your protection, I want your support.

#rwrb#red white and royal blue#rwrb movie#alex claremont diaz#henry fox mountchristen windsor#henry hanover stuart fox#firstprince#book quotes#personal#i can't anymore

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

I sit here and I watch the news about Gaza

and I think

shit, I need to get back to work;

it's toxic to just fixate on the news,

It's bad for my mental health.

I can't be irresponsible to myself

I have class in the morning.

I have exams next week...

But how can I turn a blind eye?

How can I not care

that nine thousand Gazan children are dead,

that the Israeli Occupation Force has dropped the equivalent of an atomic bomb

on a space about the size of the New York City metropolis,

that an episcopal church was bombed—

it was one of the oldest churches in the world,

that one of the oldest mosques in the region was destroyed

that hospitals are being shelled with doctors and patients still within,

that men are carrying pieces of their dead children out of houses in plastic grocery bags because there's no other way to carry that many pieces in their hands,

that over a million people were told to evacuate on bombed-out roads,

and then they were shot and bombed with USAmerican white phosphorus when trying to leave?

Do you know what white phosphorus does to a human body?????

Please google it.

And if you "don't want to see something like that"

Oh,

I want you to google it even more now.

just to be appropriately horrified.

How can I not see that the Israeli government doesn't see Palestinian people [THEIR people if we're going by statehood metrics, who were on that land when the BRITISH GOVERNMENT decided to make the state] as human beings,

that they'd do anything to slaughter Palestinians under the cover of radio silence so the world turns away?

And that men wail from minarets—

not to call their flock to holy prayer but

to speak messages of hope that god will save them,

to attempt to reach the outside world, when the information reaches the people at the edge of the strip, who have international SIM cards and can get the word out,

and to deliver news of where the bombs fall so that paramedics can know where to dig more bodies out—the bodies that aren't a bloody slurry sprayed across the streets and walls, anyways.

And that journalists are being executed en masse to hide the story.

And that men are being stripped naken and forced to sit on the ground for hours at a time, just like in Nazi Germany.

And I can't forget the fact that the United States, MY NATION, voted AGAINST a UN call for a ceasefire...

TWICE.

And that construction companies are already tearing down the old apartments to make room for new living arrangements for the colonisers, before the old buildings even stop burning.

And that settlers are coming into these abandoned homes and looting food and jewelry and desecrating prayer rugs.

And it isn't the fault of Jewish people.

I know that.

Jewish people deserve a place to be safe and free, wherever they are...

But this fact likewise does not require the creation of an ethnostate.

The implication that the only way for Jewish people to be safe is to kill everyone else... is it not in itself antisemitic?

I'm scared for the Palestinian people, and also for my Jewish diaspora friends.

They hate what's going on just as much as I do,

but they're going to get blamed by well-meaning Palestine supporters.

I know they will.

They know they will.

We all know that they will.

Another wave of antisemitism.

Another wave of islamophobia.

Another wave of killings.

Another wave of ethnic cleansing.

On it goes.

A little boy was already killed by his mother's racist landlord in Chicago. Stabbed 26 times.

Three college students were attacked and one was maimed for life.

Attacks against synagogues here in the US have only increased. Two people were shot, allegedly for a Free Palestine...

But we all know that the neonazis have been using this mess to stir the pot against Jewish people and boost their recruitment.

The Palestinian 2023/24 school year has been officially canceled going forward.

Because the enrolled students are dead or missing.

Because they were bombed with American ground-to-ground missiles.

We all know the missiles are American in origin.

Russia has its own genocide to attend to, and China doesn't care enough to give arms to anyone. And we know it's American White Phosphorus.

All the while, war profiteers in my nation get richer and richer,

richer and richer and richer,

and richer and richer and richer and richer and richer and richer—

and they'll laugh like the evil FUCKING pricks that they are

when Gaza gets bombed,

and they'll laugh like the evil FUCKING pricks that they are

when Jewish people get attacked in the streets,

because every act of violence

and every sentiment of hated

fills their pockets with more and more and more US-AMERICAN DOLLARS and GUNS and BOMBINGS and SHOOTINGS and HATRED and GOD BLESS AMERICA—

or something like that

.

.

.

I've signed petitions.

I've signed so many I've lost track of the ones I've signed and the ones I haven't, the ones for other countries that I can repost but can't sign or they might get tossed out.

I've donated money to relief organizations for when the borders re-open, because I'm an optimistic bastard like that.

I've sent emails.

I've sent... so many emails.

I've called all my Representatives in Congress.

I've spread news to as many of my friends as I can without them blocking me.

And still Gaza burns.

And still children are slaughtered, even during the fake ceasefire.

And still I have exams next week.

And still I think about how I really shouldn't fixate on this, because it affects my mood.

and it's been impacting my performance at school.

and it's been undoing months of work I've done with my therapist to try and disconnect from current events.

And still I think about how

"the current events"

rain down like hellfire on innocent mothers of dead children,

and children of dead mothers,

and sisters of dead brothers,

and brothers of dead sisters,

and fathers of dead babies,

and babies of dead fathers,