#American independent trader

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

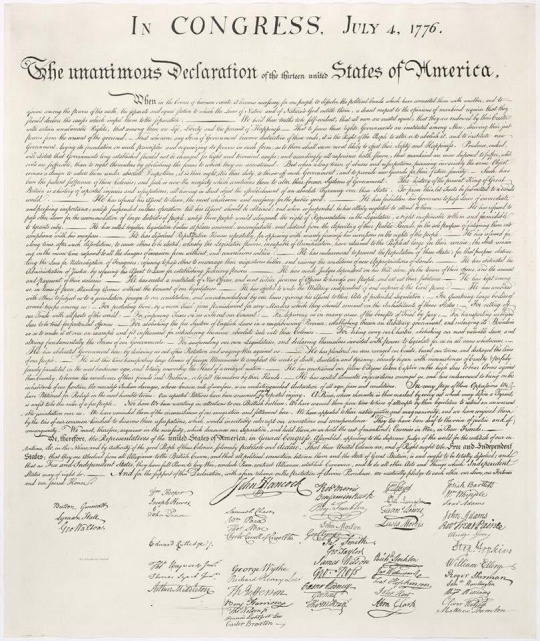

* * * Independence Day History Lesson * * *

“Have you ever wondered what happened to the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence? 🤔

Five signers were captured by the British as traitors, and tortured before they died. Twelve had their homes ransacked and burned. Two lost their sons in the revolutionary army, another had two sons captured. Nine of the 56 fought and died from wounds or hardships of the revolutionary war.

They signed and they pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor.

What kind of men were they? 👇

Twenty-four were lawyers and jurists. Eleven were merchants, nine were farmers and large plantation owners, men of means, well educated. But they signed the Declaration of Independence knowing full well that the penalty would be death if they were captured.

Carter Braxton of Virginia, a wealthy planter and trader, saw his ships swept from the seas by the British Navy. He sold his home and properties to pay his debts, and died in rags.

Thomas McKeam was so hounded by the British that he was forced to move his family almost constantly. He served in the Congress without pay, and his family was kept in hiding. His possessions were taken from him, and poverty was his reward.

Vandals or soldiers or both, looted the properties of Ellery, Clymer, Hall, Walton, Gwinnett, Heyward, Ruttledge, and Middleton.

At the battle of Yorktown, Thomas Nelson Jr., noted that the British General Cornwallis had taken over the Nelson home for his headquarters. The owner quietly urged General George Washington to open fire. The home was destroyed, and Nelson died bankrupt.

Francis Lewis had his home and properties destroyed. The enemy jailed his wife, and she died within a few months.

John Hart was driven from his wife’s bedside as she was dying. Their 13 children fled for their lives. His fields and his gristmill were laid to waste. For more than a year he lived in forests and caves, returning home to find his wife dead and his children vanished. A few weeks later he died from exhaustion and a broken heart. Norris and Livingston suffered similar fates.

Such were the stories and sacrifices of the American Revolution. These were not wild eyed, rabble-rousing ruffians. They were soft-spoken men of means and education. They had security, but they valued liberty more. Standing tall, straight, and unwavering, they pledged: ‘For the support of this declaration, with firm reliance on the protection of the divine providence, we mutually pledge to each other, our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.’”

- Michael W. Smith

Happy Independence Day 🇺🇸 💫

#pay attention#educate yourselves#educate yourself#knowledge is power#reeducate yourself#reeducate yourselves#think for yourself#think for yourselves#think about it#do your homework#do some research#history research#do your own research#do your research#question everything#ask yourself questions#american history#history lesson

359 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Have you ever wondered what happened to the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence?

Five signers were captured by the British as traitors, and tortured before they died. Twelve had their homes ransacked and burned. Two lost their sons in the revolutionary army, another had two sons captured. Nine of the 56 fought and died from wounds or hardships of the revolutionary war.

They signed and they pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor.

What kind of men were they? Twenty-four were lawyers and jurists. Eleven were merchants, nine were farmers and large plantation owners, men of means, well educated. But they signed the Declaration of Independence knowing full well that the penalty would be death if they were captured.

Carter Braxton of Virginia, a wealthy planter and trader, saw his ships swept from the seas by the British Navy. He sold his home and properties to pay his debts, and died in rags.

Thomas McKeam was so hounded by the British that he was forced to move his family almost constantly. He served in the Congress without pay, and his family was kept in hiding. His possessions were taken from him, and poverty was his reward.

Vandals or soldiers or both, looted the properties of Ellery, Clymer, Hall, Walton, Gwinnett, Heyward, Ruttledge, and Middleton.

At the battle of Yorktown, Thomas Nelson Jr., noted that the British General Cornwallis had taken over the Nelson home for his headquarters. The owner quietly urged General George Washington to open fire. The home was destroyed, and Nelson died bankrupt.

Francis Lewis had his home and properties destroyed. The enemy jailed his wife, and she died within a few months.

John Hart was driven from his wife’s bedside as she was dying. Their 13 children fled for their lives. His fields and his gristmill were laid to waste. For more than a year he lived in forests and caves, returning home to find his wife dead and his children vanished. A few weeks later he died from exhaustion and a broken heart. Norris and Livingston suffered similar fates.

Such were the stories and sacrifices of the American Revolution. These were not wild eyed, rabble-rousing ruffians. They were soft-spoken men of means and education. They had security, but they valued liberty more. Standing tall, straight, and unwavering, they pledged: ‘For the support of this declaration, with firm reliance on the protection of the divine providence, we mutually pledge to each other, our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.’”

- Michael W Smith

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

🔶 SAT after Shabbat - ISRAEL REALTIME - Connecting to Israel in Realtime

Shavua tov, a good week, a blessed week, success and safety for our warriors, safe return for our hostages.

▪️A HERO SOLDIER HAS FALLEN.. in battle in Gaza: Yair Avitan, 20, from Ra’anana. May his family be comforted among the mourners of Zion and Jerusalem, and may G-d avenge his blood!

.. Related, condition of Jeri Deri remains critical, family asks for prayers for Rabbi Raphael Yehuda ben Esther.

▪️IRAN THREATENS.. Iran threatened Israel with a "war of annihilation" if it attacked Lebanon. This is what the Iranian delegation told the UN. "Despite the fact that Iran sees Israel's propaganda about its intention to attack Lebanon as psychological warfare, if it launches a full-scale military attack, a war of annihilation will begin. All options, including the full involvement of all resistance fronts, are on the table.”

▪️SAUDI ARABIA & SPAIN ADVISE CITIZENS TO LEAVE LEBANON.. immediately!

▪️TOURISTS SWEPT AWAY IN DEAD SEA.. 4 tourists from India blown away from shore. Last report: 3 rescued, 1 in serious condition.

🔸DEAL again? “US submitted a new proposal to Hamas.”

.. A political official in the Prime Minister's Office: Israel is committed to the wording of the proposal that President Biden welcomed. (Seems to be saying a new proposal is not agreed to.)

.. Osama Hamdan, a senior Hamas official, said there was no progress regarding a ceasefire. "We are still ready to respond positively to any proposal that ends the war." (But not that releases hostages or disarms Hamas.)

▪️AID PIER.. Pentagon: “floating pier will be dismantled due to sea conditions”, again.

▪️AID ROTTING.. The UN has not yet collected 1,100 trucks that have been waiting for several weeks at the Kerem Shalom crossing. The same goes for 9,000 loaded pallets that have been waiting to be picked up for several weeks from the American dock shore staging area.

.. What moved? Thursday: 53 trucks for private traders entered the strip from the Kerem Shalom crossing (guess what they are carrying - cigarettes). 72 trucks were brought into the Gaza Strip through the Erez crossing by the UN aid organizations.

▪️SKIN CANCER WEEK IN ISRAEL.. Every month in Israel, approximately 170 adults are diagnosed with skin cancer. Get periodic checks with a dermatologist, and if it looks or feels weird see your doctor.

▪️SHURAT HADIN - PROSECUTE CLOONEY.. Shurat HaDin petitions the US Attorney General to prosecute Amal Clooney, who advised the International Criminal Court to put out warrants over the war - in violation of 2 US federal laws prohibiting assisting international organizations against US allies.

⭕ ISLAMIC RESISTANCE OF IRAQ.. claims to have attacked the "Waller" oil tanker in the Mediterranean Sea, which was destined to reach the port of Haifa. No such attack known.

⭕ ANTI-TANK MISSILES (8) fired by HEZBOLLAH at Mashgav area, Mt. Dov outpost, Metulla, and Avivim.

⭕ HEZBOLLAH ROCKETS hit a horse barn in the Western Galilee, killing 2 horses.

⭕ FRIDAY NIGHT HEZBOLLAH MASSIVE BARRAGE - 15 rounds of Rockets & Drones - across a wide area of northern towns and cities.

⭕ HEZBOLLAH ROCKETS - this afternoon - at Tel Hai, Kiryat Shmona

⭕ HAMAS ROCKETS - short range - near-Gaza Nir Am Shooting Range, Sderot, Ibim, Nir Am

♦️ARTILLERY.. shelling in the center of Shujaiya, Gaza, and in the Alshakosh area, west of Rafah.

♦️RAFAH’s GOING GUERRILLA.. Commander of the 12th Brigade: Hamas is waging a guerrilla war in Rafah consisting of independent groups, which makes the combat mission difficult.

♦️IDF AIRSTRIKES LEBANON.. outskirts of Kfar Shuba, and in the villages of Kila and Zebkin.

♦️COUNTER-TERROR OPERATIONS - ANBATA.. east of Tulkarm, overnight.

♦️GAZANS CLAIM.. that IDF destroyed 500 dunams / 125 acres of greenhouses northwest of Rafah.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The resistances to slavery were the principal grounds for the radically alternative political culture that coalesced in the Black communities of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the era of revolutionary, liberal, and nationalist impulses among Europeans in North America. Among Blacks, the rule of law was respected for its power rather than for any resemblance to justice or a moral order. For the slaves, the rule of law was an injustice, a mercurial and violent companion to their humiliations, a form of physical abuse, a force for the destruction of their families, and an omnipresent cruelty to their loved ones. Even for free Blacks, the rule of law was too often a cruel hypocrisy, impotent in protecting their tenuous status. For both the slaves and the free Blacks, even as revolutionary fervor increased among the colonists, the masquerades of the law were becoming more transparent: the domestic slave trade displaced the African slave trade in the late eighteenth century. With this new economy of slavery, the separation of slave families by sale and the kidnapping and enslavement of free Blacks increased astronomically.

To the very contrary, the rebellious colonial ruling class sought to invest the rule of law with a moral authority sufficient to justify their rejection of British authority. As slave traders and merchants, as slaveholders and propagandists, as lawyers, ministers, and civil authorities for slavery, the most influential men and women among the emergent American community used the rule of law as the warrant for the justness of their claims and practices. By their law they hunted, traded, bought, and sold other human beings; waged war against, whipped, dismembered, burned, hanged, and tortured their property for possessing a human will; treated their colonist servants and laboring classes with the customary disdain of the English gentle classes. Now this same law was to serve their revolutionary ambitions, their right to liberty.

On this score, the Blacks, particularly the slaves, possessed conflicting opinions. The 5,000 Blacks who fought for American independence fought for liberty, and had a very different vision of national freedom than the one imagined by their countrymen. But as we shall see, many thousands of Blacks would fight against independence, not for love of imperial Britain but because they understood that Black freedom was otherwise unobtainable. Like the Native American nations that sided with the British, the Black Loyalists sought to employ the British army to serve their own interests, for their own ends. Long after the defeated British had departed, their allies, the Native Americans and the Blacks, continued the struggle for liberty. For generations to come, Native Americans recognized America as a colonial power, and Blacks read the new nation as tyrannical. Their suspicion of and opposition toward American society survived in the political cultures of Blacks and Native Americans for the next two hundred years."

Cedric Robinson, Black Movements in America (1997)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Walla Walla – People of Many Waters

A Sahaptin tribe who lived for centuries on the Columbia River Plateau in northeastern Oregon and southeastern Washington, their name is translated several ways but, most often, as “many waters.” While the people have their own distinct dialect, their language is closely related to the Nez Perce. The tribe included many groups and bands that were often referred to by their village names, such as Wallulapum and Chomnapum ... A hunter-gatherer tribe, they lived in “tents” that were easy to move. However, their lodging differed from many other nomadic tribes, in that it was bigger and covered with tule mats rather than hides. Called a longhouse, it was made out of lodge poles much like a tepee, but was much longer, sometimes as much as 80 feet in length. Resembling a modern-day “A” frame house in appearance, the lodge poles were covered with mats made of tule, a plant that grows freely in the area along waterways. When the tribe moved, the mats were gathered and moved and the lodge poles left behind ... Beginning in the early 1700s the Walla Walla people raised great herds of horses, making their lifestyle much easier as they gathered seasonal plants. They also traveled across the Rocky Mountains to trade dried roots and salmon to the Plains Indians for buffalo meat and hides ... The people were first encountered by white travelers during the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. The explorers were warmly welcomed by Chief Yellepit, whose village of about 15 lodges, was situated on the Columbia River near the mouth of the Walla Walla River. The communication between the two groups was made between a Shoshone woman who had been captured by the Walla Walla and the expedition’s guide and interpreter, Sacagawea, who was also of the Shoshone tribe. Though Yelleppit extended an offer to the expedition to stay with the village, Lewis and Clark were in a hurry to reach the Pacific Ocean. However, they promised to spend a few days on their return. In April 1806, as the explorers began to make their way back east, the expedition spent several days with the Walla Walla, during which time, gifts were exchanged and goods traded. Two of the items left by the expedition with the tribe was a peace medal engraved with a portrait of Thomas Jefferson and a small American flag. In their documentation, Lewis and Clark estimated the tribe’s numbers as 1,600; however, this probably included other bands now recognized as independent ... The next non-native to encounter the Walla Walla people was a trader by the name of David Thompson of the Canadian-British North West Company, who arrived in 1811. About five miles upriver from Chief Yellepit’s village, he staked a pole with a note claiming the territory for the British Crown and declaring that the North West Company intended to build a trading post at the site. Continuing downriver, Thompson stopped at Yellepit’s village, where he discovered the American “claims” in the form of Yellepit’s flag and medal. Though neither Lewis and Clark or Thompson had much power to actually lay claim to the region, Yellepit was very supportive of the idea of Canadians setting up a trading post nearby ...

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

F.8.6 How did working people view the rise of capitalism?

The best example of how hated capitalism was can be seen by the rise and spread of the labour and socialist movements, in all their many forms, across the world. It is no coincidence that the development of capitalism also saw the rise of socialist theories. Nor was it a coincidence that the rising workers movement was subjected to extensive state repression, with unions, strikes and other protests being systematically repressed. Only once capital was firmly entrenched in its market position could economic power come to replace political force (although, of course, that always remained ready in the background to defend capitalist property and power).

The rise of unions, socialism and other reform movements and their repression was a feature of all capitalist countries. While America is sometime portrayed as an exception to this, in reality that country was also marked by numerous popular movements which challenged the rise of capitalism and the transformation of social relationships within the economy from artisanal self-management to capitalist wage slavery. As in other countries, the state was always quick to support the capitalist class against their rebellious wage slaves, using first conspiracy and then anti-trust laws against working class people and their organisations. So, in order to fully understand how different capitalism was from previous economic systems, we will consider early capitalism in the US, which for many right-“libertarians” is the example of the “capitalism-equals-freedom” argument.

Early America was pervaded by artisan production — individual ownership of the means of production. Unlike capitalism, this system is not marked by the separation of the worker from the means of life. Most people did not have to work for another, and so did not. As Jeremy Brecher notes, in 1831 the “great majority of Americans were farmers working their own land, primarily for their own needs. Most of the rest were self-employed artisans, merchants, traders, and professionals. Other classes — employees and industrialists in the North, slaves and planters in the South — were relatively small. The great majority of Americans were independent and free from anybody’s command.” [Strike!, p. xxi] So the availability of land ensured that in America, slavery and indentured servants were the only means by which capitalists could get people to work for them. This was because slaves and servants were not able to leave their masters and become self-employed farmers or artisans. As noted in the last section this material base was, ironically, acknowledged by Rothbard but the implications for freedom when it disappeared was not. While he did not ponder what would happen when that supply of land ended and whether the libertarian aspects of early American society would survive, contemporary politicians, bosses, and economists did. Unsurprisingly, they turned to the state to ensure that capitalism grew on the grave of artisan and farmer property.

Toward the middle of the 19th century the economy began to change. Capitalism began to be imported into American society as the infrastructure was improved by state aid and tariff walls were constructed which allowed home-grown manufacturing companies to develop. Soon, due to (state-supported) capitalist competition, artisan production was replaced by wage labour. Thus “evolved” modern capitalism. Many workers understood, resented, and opposed their increasing subjugation to their employers, which could not be reconciled with the principles of freedom and economic independence that had marked American life and had sunk deeply into mass consciousness during the days of the early economy. In 1854, for example, a group of skilled piano makers hoped that “the day is far distant when they [wage earners] will so far forget what is due to manhood as to glory in a system forced upon them by their necessity and in opposition to their feelings of independence and self-respect. May the piano trade be spared such exhibitions of the degrading power of the day [wage] system.” [quoted by Brecher and Costello, Common Sense for Hard Times, p. 26]

Clearly the working class did not consider working for a daily wage, in contrast to working for themselves and selling their own product, to be a step forward for liberty or individual dignity. The difference between selling the product of one’s labour and selling one’s labour (i.e. oneself) was seen and condemned (”[w]hen the producer … sold his product, he retained himself. But when he came to sell his labour, he sold himself … the extension [of wage labour] to the skilled worker was regarded by him as a symbol of a deeper change.” [Norman Ware, The Industrial Worker, 1840–1860, p. xiv]). Indeed, one group of workers argued that they were “slaves in the strictest sense of the word” as they had “to toil from the rising of the sun to the going down of the same for our masters — aye, masters, and for our daily bread.” [quoted by Ware, Op. Cit., p. 42] Another group argued that “the factory system contains in itself the elements of slavery, we think no sound reasoning can deny, and everyday continues to add power to its incorporate sovereignty, while the sovereignty of the working people decreases in the same degree.” [quoted by Brecher and Costello, Op. Cit., p. 29] For working class people, free labour meant something radically different than that subscribed to by employers and economists. For workers, free labour meant economic independence through the ownership of productive equipment or land. For bosses, it meant workers being free of any alternative to consenting to authoritarian organisations within their workplaces — if that required state intervention (and it did), then so be it.

The courts, of course, did their part in ensuring that the law reflected and bolstered the power of the boss rather than the worker. “Acting piecemeal,” summarises Tomlins, “the law courts and law writers of the early republic built their approach to the employment relationship on the back of English master/servant law. In the process, they vested in the generality of nineteenth-century employers a controlling authority over the employees founded upon the pre-industrial master’s claim to property in his servant’s personal services.” Courts were “having recourse to master/servant’s language of power and control” as the “preferred strategy for dealing with the employment relation” and so advertised their conclusion that “employment relations were properly to be conceived of as generically hierarchical.” [Op. Cit., p. 231 and p. 225] As we noted in last section the courts, judges and jurists acted to outlaw unions as conspiracies and force workers to work the full length of their contracts. In addition, they also reduced employer liability in industrial accidents (which, of course, helped lower the costs of investment as well as operating costs).

Artisans and farmers correctly saw this as a process of downward mobility toward wage labour and almost as soon as there were wage workers, there were strikes, machine breaking, riots, unions and many other forms of resistance. John Zerzan’s argument that there was a “relentless assault on the worker’s historical rights to free time, self-education, craftsmanship, and play was at the heart of the rise of the factory system” is extremely accurate. [Elements of Refusal, p. 105] And it was an assault that workers resisted with all their might. In response to being subjected to the wage labour, workers rebelled and tried to organise themselves to fight the powers that be and to replace the system with a co-operative one. As the printer’s union argued, its members “regard such an organisation [a union] not only as an agent of immediate relief, but also as an essential to the ultimate destruction of those unnatural relations at present subsisting between the interests of the employing and the employed classes … when labour determines to sell itself no longer to speculators, but to become its own employer, to own and enjoy itself and the fruit thereof, the necessity for scales of prices will have passed away and labour will be forever rescued from the control of the capitalist.” [quoted by Brecher and Costello, Op. Cit., pp. 27–28]

Little wonder, then, why wage labourers considered capitalism as a modified form of slavery and why the term “wage slavery” became so popular in the labour and anarchist movements. It was just reflecting the feelings of those who experienced the wages system at first hand and who created the labour and socialist movements in response. As labour historian Norman Ware notes, the “term ‘wage slave’ had a much better standing in the forties [of the 19th century] than it has today. It was not then regarded as an empty shibboleth of the soap-box orator. This would suggest that it has suffered only the normal degradation of language, has become a cliche, not that it is a grossly misleading characterisation.” [Op. Cit., p. xvf] It is no coincidence that, in America, the first manufacturing complex in Lowell was designed to symbolise its goals and its hierarchical structure nor that its design was emulated by many of the penitentiaries, insane asylums, orphanages and reformatories of the period. [Bookchin, The Ecology of Freedom, p. 392]

These responses of workers to the experience of wage labour is important as they show that capitalism is by no means “natural.” The fact is the first generation of workers tried to avoid wage labour is at all possible — they hated the restrictions of freedom it imposed upon them. Unlike the bourgeoisie, who positively eulogised the discipline they imposed on others. As one put it with respect to one corporation in Lowell, New England, the factories at Lowell were “a new world, in its police it is imperium in imperio. It has been said that an absolute despotism, justly administered … would be a perfect government … For at the same time that it is an absolute despotism, it is a most perfect democracy. Any of its subjects can depart from it at pleasure . .. Thus all the philosophy of mind which enter vitally into government by the people … is combined with a set of rule which the operatives have no voice in forming or administering, yet of a nature not merely perfectly just, but human, benevolent, patriarchal in a high degree.” Those actually subjected to this “benevolent” dictatorship had a somewhat different perspective. Workers, in contrast, were perfectly aware that wage labour was wage slavery — that they were decidedly unfree during working hours and subjected to the will of another. The workers therefore attacked capitalism precisely because it was despotism (“monarchical principles on democratic soil”) and thought they “who work in the mills ought to own them.” Unsurprisingly, when workers did revolt against the benevolent despots, the workers noted how the bosses responded by marking “every person with intelligence and independence … He is a suspected individual and must be either got rid of or broken in. Hundreds of honest labourers have been dismissed from employment … because they have been suspected of knowing their rights and daring to assert them.” [quoted by Ware, Op. Cit., p. 78, p. 79 and p. 110]

While most working class people now are accustomed to wage labour (while often hating their job) the actual process of resistance to the development of capitalism indicates well its inherently authoritarian nature and that people were not inclined to accept it as “economic freedom.” Only once other options were closed off and capitalists given an edge in the “free” market by state action did people accept and become accustomed to wage labour. As E. P. Thompson notes, for British workers at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, the “gap in status between a ‘servant,’ a hired wage-labourer subject to the orders and discipline of the master, and an artisan, who might ‘come and go’ as he pleased, was wide enough for men to shed blood rather than allow themselves to be pushed from one side to the other. And, in the value system of the community, those who resisted degradation were in the right.” [The Making of the English Working Class, p. 599]

Opposition to wage labour and factory fascism was/is widespread and seems to occur wherever it is encountered. “Research has shown”, summarises William Lazonick, “that the ‘free-born Englishman’ of the eighteenth century — even those who, by force of circumstance, had to submit to agricultural wage labour — tenaciously resisted entry into the capitalist workshop.” [Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor, p. 37] British workers shared the dislike of wage labour of their American cousins. A “Member of the Builders’ Union” in the 1830s argued that the trade unions “will not only strike for less work, and more wages, but will ultimately abolish wages, become their own masters and work for each other; labour and capital will no longer be separate but will be indissolubly joined together in the hands of workmen and work-women.” [quoted by E. P. Thompson, Op. Cit., p. 912] This perspective inspired the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union of 1834 which had the “two-fold purpose of syndicalist unions — the protection of the workers under the existing system and the formation of the nuclei of the future society” when the unions “take over the whole industry of the country.” [Geoffrey Ostergaard, The Tradition of Workers’ Control, p. 133] As Thompson noted, “industrial syndicalism” was a major theme of this time in the labour movement. “When Marx was still in his teens,” he noted, British trade unionists had “developed, stage by stage, a theory of syndicalism” in which the “unions themselves could solve the problem of political power” along with wage slavery. This vision was lost “in the terrible defeats of 1834 and 1835.” [Op. Cit., p. 912 and p. 913] In France, the mutualists of Lyons had come to the same conclusions, seeking “the formation of a series of co-operative associations” which would “return to the workers control of their industry.” Proudhon would take up this theme, as would the anarchist movement he helped create. [K. Steven Vincent, Pierre-Jospeh Proudhon and the Rise of French Republican Socialism, pp. 162–3] Similar movements and ideas developed elsewhere, as capitalism was imposed (subsequent developments were obviously influenced by the socialist ideas which had arisen earlier and so were more obviously shaped by anarchist and Marxist ideas).

This is unsurprising, the workers then, who had not been swallowed up whole by the industrial revolution, could make critical comparisons between the factory system and what preceded it. “Today, we are so accustomed to this method of production [capitalism] and its concomitant, the wage system, that it requires quite an effort of imagination to appreciate the significance of the change in terms of the lives of ordinary workers … the worker became alienated … from the means of production and the products of his labour … In these circumstances, it is not surprising that the new socialist theories proposed an alternative to the capitalist system which would avoid this alienation.” While wage slavery may seem “natural” today, the first generation of wage labourers saw the transformation of the social relationships they experienced in work, from a situation in which they controlled their own work (and so themselves) to one in which others controlled them, and they did not like it. However, while many modern workers instinctively hate wage labour and having bosses, without the awareness of some other method of working, many put up with it as “inevitable.” The first generation of wage labourers had the awareness of something else (although a flawed and limited something else as it existed in a hierarchical and class system) and this gave then a deep insight into the nature of capitalism and produced a deeply radical response to it and its authoritarian structures. Anarchism (like other forms of socialism) was born of the demand for liberty and resistance to authority which capitalism had provoked in its wage slaves. With our support for workers’ self-management of production, “as in so many others, the anarchists remain guardians of the libertarian aspirations which moved the first rebels against the slavery inherent in the capitalist mode of production.” [Ostergaard, Op. Cit., p. 27 and p. 90]

State action was required produce and protect the momentous changes in social relations which are central to the capitalist system. However, once capital has separated the working class from the means of life, then it no longer had to rely as much on state coercion. With the choice now between wage slavery or starving, then the appearance of voluntary choice could be maintained as economic power was/is usually effective enough to ensure that state violence could be used as a last resort. Coercive practices are still possible, of course, but market forces are usually sufficient as the market is usually skewed against the working class. However, the role of the state remains a key to understanding capitalism as a system rather than just specific periods of it. This is because, as we stressed in section D.1, state action is not associated only with the past, with the transformation from feudalism to capitalism. It happens today and it will continue to happen as long as capitalism continues.

Far from being a “natural” development, then, capitalism was imposed on a society by state action, by and on behalf of ruling elites. Those working class people alive at the time viewed it as “unnatural relations” and organised to overcome it. It is from such movements that all the many forms of socialism sprang, including anarchism. This is the case with the European anarchism associated with Proudhon, Bakunin and Kropotkin as well as the American individualist anarchism of Warren and Tucker. The links between anarchism and working class rebellion against the autocracy of capital and the state is reflected not only in our theory and history, but also in our anarchist symbols. The Black Flag, for example, was first raised by rebel artisans in France and its association with labour insurrection was the reason why anarchists took it up as our symbol (see the appendix on “The Symbols of Anarchy”). So given both the history of capitalism and anarchism, it becomes obvious any the latter has always opposed the former. It is why anarchists today still seek to encourage the desire and hope for political and economic freedom rather than the changing of masters we have under capitalism. Anarchism will continue as long as these feelings and hopes still exist and they will remain until such time as we organise and abolish capitalism and the state.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you’re enjoying the Cecil Union debate of 2023, or if you like Cecil are confused about what exactly a union is, here are three that you can check out! These collectives work towards building a worker-owned future and have projects such as mutual aid, education campaigns, and volunteer initiative all across the country.

Workers United, which has been in the news a lot lately due to organizing by Starbucks Baristas for living wages and better work conditions. This is the union I was a part of (until Starbucks fired me recently)

United Food and Commercial Workers Union, which represents the growing Trader Joe’s employee union! Food service sucks and it’s important to support folks who work in this oftentimes dangerous sector with representation.

Strippers United, the only American national union run entirely by sex workers. This union is working to decriminalize sex work and reclassify strippers as employees rather than independent contractors.

Fuck the man! Join a union! If you can’t join one - start one instead!

And remember, one worker is more valuable than all CEOS put together.

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Amazing grace how sweet the sound, that saved a wretch like me. I once was lost, but now I'm found. Was blind but now I see…”

Sung an estimated 10 million times each year, "Amazing Grace" was born not of American Black spirituals as some believe, but across the Atlantic, in the tiny English market town of Olney, some 60 miles north of London, with lyrics older than the Declaration of Independence.

John Newton, a slave trader who eventually became a minister, penned the famous words of "Amazing Grace" for a sermon for his 1773 New Year's service at the Church of St. Peter and St. Paul.

“Amazing Grace” was a partial reflection of John Newton’s own self-perception at the time and his ultimate transformation into a man of faith.

Near the end of his life, Newton worked to help abolish the slave trade in England.

Forgiveness and redemption are possible, may humanity finally wake up and see…

🙏🏻❤️🙏🏻

#america#american#amazing grace#pray for america#god bless america#christianity#christ jesus#yieldfruit#christian

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Engraving of Spaniards enslaving Native Americans by Theodor de Bry (1528–1598), published in America. part 6. Frankfurt, 1596

What Happened?

In the beginning colonists enslaved African and Native American people. Native Americans were enslaved before African people arrived to the United States. Eventually the arrival of African slaves caused the development of relationship, a kinship, between these two cultures. They grew to have children together creating the Black Indigenous race. African and Native American people produce intermarriage.

In the beginning Black Native Americans were created through enslavement as time progressed some Native American populations decided to enslave Africans. Children that came from intermarriage of Black and Native American people were considered illegitimate. There wasn't enough Native American blood to address that as their identity.

The Facts?

"As early as 1708, the slave population of South Carolina, a colony that benefited from fully conceived practices of slavery in Barbados, had an enslaved population of 2,900 African descended slaves and 1,400 Native American slaves"

"In Charleston, South Carolina, slave traders could purchase both African and Native American slaves; however, these experiences were not merely documented in the annals of history, periodicals, and scientific analysis."

Interested in Reading More?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genealogy Sites

This is a list of all the sites that I’ve used to research my family history. Some of these sites may be state specific (Carolinas) but most of them include information from through the country. I will continue to update the list as time goes on 🤌🏾

Slave Narratives (I was able to find one of my ancestors through this, they were interviewed) https://www.loc.gov/collections/slave-narratives-from-the-federal-writers-project-1936-to-1938/about-this-collection/

Slave Voyages (If you would like to get information on the slave ships, ports, and possibly markets) https://www.slavevoyages.org/

Lowcountry Africana (lists the names of freedmen and their counties, this is focusing on the state of South Carolina) https://lowcountryafricana.com/

South Carolina Plantations (lists the plantations owned throughout the state, some have more information) https://south-carolina-plantations.com/

Race and Slavery Petitions (legal documents concerning slaves, free people of color, and white people) https://dlas.uncg.edu/petitions/

Fold3 (military related records) https://www.googleadservices.com/pagead/aclk?sa=L&ai=DChcSEwjzyemb27P-AhXHFdQBHdQhAKcYABAAGgJvYQ&ae=2&ohost=www.google.com&cid=CAESa-D22pb5Baezi2zOQjbzS8dX8mAHU3FYMHV7nDM6hDG-QfuJjyvM5UhkOdqQKmnYkPmOw4WLqYwmNPsmIEkWhD537b9hOSATv7xHExAvsLnbo8ak8vURfKWQgQjP1ngE1JDxgkvDP0TPPzZl&sig=AOD64_2CatEJVnBDXpyjDm9G2h0saZZ9tw&q&adurl&ved=2ahUKEwjOkdyb27P-AhVymGoFHWKhA4EQ0Qx6BAgGEAE

Plantations of North Carolina (list of plantations throughout the state split into counties) https://www.ncgenweb.us/ncstate/plantations/nc_plantations.html

#black spiritualist#african american culture#black spiritualism#hoodoo tumblr#hoodoo#african american spirituality#black genealogy#black history

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Unofficial Black History Book

~~

Phillis Wheatley (1753-1784)

Imagine being the best-known and also the first African-American woman to publish a book of poetry at the age of 13, whilst being a slave.

This is her story.

Phillis Wheatley was the first African-American and second female to publish a book of poems. And she was also the youngest.

Phillis Wheatley was born on May 8th, 1753, in Gambia, West Africa. There's no record of her real birth name.

When she was no younger than seven, she was kidnapped by slave traders and brought to America in 1761. The slave traders renamed her 'Phillis' based on the slave ship she arrived on, 'The Phillis'

She was transported to the Boston docks with a shipment of "refugee" slaves who, because of their age or physical frailty, were unsuited for rigorous labor in the West Indian and Southern Colonies. They were the first ports of call after the Atlantic Crossing.

In August 1761, Susanna Wheatley, the wife of Boston tailor John Wheatley, was "in want of a domestic."

Susanna purchased "a slender, frail female child...for a trifle."

The captain of the slave ship believed that Phillis was terminally ill, and he wanted to make at least a small profit off of her before she died.

It's reported that a Wheatley relative surmised her to be "of slender frame and evidently suffering from a change of climate," "nearly naked, with no other covering than a quantity of dirty carpet about her," and "about seven years old...from the circumstances of shedding her front teeth."

When Phillis was sold to the Wheatley family, she adopted their last name and was taken under Susanna's wing as her domestic.

During her time serving the Wheatleys, which was about sixteen months, Susana discovered that Phillis had an extraordinary capacity to learn. The Wheatleys, including their son Nathaniel and their daughter Mary, taught her how to read and write after discovering her precociousness.

But this didn't excuse her from her duties as a house slave.

Phillis was soon immersed in the Bible, astronomy, geography, history, theology, British literature, and the Greek and Latin classics of Virgil, Ovid, Terence, and Homer. Inspired, she began writing poetry between the ages of 12 and 13.

At a time when African Americans were discouraged and intimidated from learning how to read and write, Phillis' life was an anomaly.

When she started to publish her poems, her fame, and talent soon spread across the Atlantic. With Susanna's support, Phillis started posting advertisements for subscribers for her first book of poems.

However, a scholar of Phillis's work, Sondra O'Neale, notes, "When the colonists were apparently unwilling to support literature by an African, she and the Wheatleys turned in frustration to London for a publisher."

In 1773, Phillis was in continuously poor health; she had chronic asthma. But she sets off for London with Nathaniel Wheatley, her master's son.

When she arrived in London, she was accepted and adored for both her poise and her literary work. And during her time there, she also received medical treatment for the ailments she was battling.

She met Selina Hastings, a friend of Susanna Wheatley and the Countess of Huntingdon. Eventually, Hastings funded the publication of Phillis's book. "Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral." Was the first book of poetry published by an enslaved African American in the United States.

Her book includes many elegies as well as poems on Christian themes, even dealing with race, such as the often-anthologized "On being brought from Africa to America."

Phillis was also a strong supporter of America's fight for independence; she penned several of her poems in honor of George Washington, who was Commander of the Continental Army. She sent him one of her works that was written in 1775, and it eventually inspired an invitation to visit him in Cambridge, Massachusetts. In March 1776, she traveled to Washington.

Phillis eventually had to return to Boston to tend to Susanna Wheatley, who was gravely ill.

After the elder Wheatleys’ died, Phillis was left with nothing and had to support herself as a seamstress.

We don’t know exactly when she was freed by the Wheatleys, but some scholars suggest that she was freed between 1774 and 1778. And during that time, most of the Wheatley family had died.

Even with her literary popularity at its all-time high and being manumitted, freedom in 1774 Boston proved to be incredibly difficult.

Phillis was unable to secure funding for another publication or even sell her writing.

In 1778, she was married to a free African American man from Boston named John Peters. They had three children, but sadly, none of them survived infancy.

Their marriage proved to be a struggle due to the couple's battle with constant poverty. Phillis was then forced to find work as a maid in a boarding house, where she lived in squalid, horrifying conditions.

Even through all her misfortune, Phillis continued to write. But, with the growing tensions between the British and the Revolutionary War, she lost enthusiasm for her poems.

Although she continued to contact various publishers, she was unsuccessful in finding support for a second volume of poetry.

On December 5th, 1784, Phillis Wheatley died alone in a boarding house at 31 years old, without a penny to her name.

Many of her poems for her second volume disappeared and have never been recovered.

___

Next Chapter

The 16 Street Baptist Church Bombing

_____

My Resources

#the unofficial black history book#black history matters#black history 365#black history#black history is american history#black culture#black tumblr#black tumblr writers#black female writers#black female poets#know your history#learn your roots#black figures#herstory#history#black writblr#phillis wheatley#black activism#discrimination#writers on tumblr#black stories#black authors#women in history

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Overview of WL COMPANY DMCC financial marketplace

The company we want to talk about today is called WL COMPANY DMCC. WL Company DMCC (License Number DMCC-89711, Registration Number DMCC19716, Account Number 411911), registered in Dubai, UAE whose registered office is Unit No BA95, DMCC Business Centre, Level No 1, represented by the Director, Stephanie Sandilands.

DMCC is the largest free trade zone in the United Arab Emirates, which is located in Dubai. It was established in 2002 and now serves as a commodity exchange that operates in four sectors: precious goods; energy; steel and metals; agricultural products.

Main services and activities

WL COMPANY DMCC is a financial marketplace, the direction of which is financial services, consulting, management, analysis of services, provision of services by third parties to the end user. The list also includes:

• Investment ideas;

• Active product trading;

• Analytical support for traders;

• Selection of an investment strategy in the market using various assets.

WL COMPANY DMCC operates on the MetaTrader 5 trading platform. There is a convenient registration, detailed instructions, as well as the ability to connect a demo account for self-study.

Among the main services:

1. Trading.

2. Social Services.

3.ESG Investment.

4. Analytics.

5. Wealth management.

Company managers will help with registration, with opening an account, with access to the platform. After training (if required), you can make a minimum deposit of 500 USD and start trading.

Main advantages and disadvantages of WL COMPANY DMCC

Before going directly to the benefits of the marketplace, it is worth saying a few words about the loyalty program. Depending on the amount of investment, the user receives one of three grades. Each of them gives certain privileges. The program itself makes it possible to get the maximum effect from investments in a short time.

Now about the benefits of WL COMPANY DMCC:

1. Availability of a license in the jurisdiction of the DMCC trading zone.

2. No commission when making SFD transactions on shares.

3. More than 6700 trading instruments.

4. High professional level of support.

5. Very strong analytical support (client confidence level 87%).

6. Weekly comments and summaries from WL COMPANY experts.

7. Modern analysis software.

8. Large selection of investment solutions.

9. Own exclusive market analysis services in various areas.

10. Own analytical department with the publication of materials in the public domain.

11. Modern focus on social services.

The feedback from WL COMPANY DMCC clients highlights the positive characteristics of the work of marketplace analysts, the convenience of a personal account, the speed of processing positions, analysis tools, and low commissions.

Negative reviews relate to the freezing of the system, delays in withdrawing funds for a day, and the small age of the company. Also, for some users, the application for withdrawal of funds was not processed the first time, and someone could not instantly replenish the deposit. North American traders complain that WL COMPANY DMCC only has a presence in Dubai.

At the same time, the financial group received several significant awards:

• Best MetaTrader 5 Broker 2022

• The Most Reliable Fintech Service 2023

Outcome

According to the information received, it can be concluded that WL COMPANY DMCC can be called a good financial marketplace in the modern market. By registering with the DMCC, the company can be called reliable and trustworthy. There are also negative reviews, but they relate mainly to the technical component.

For August, 2023 WL COMPANY DMCC has about 12000 clients worldwide. The main regions are North America, Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Traders can act independently or use the advice of marketplace experts.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Adams and Hamilton, briefly

A closer examination of Adams’s use of eighteenth-century moral philosophy, especially Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments, reveals a striking and underappreciated originality in Adams’s political thought. As Luke Mayville has powerfully demonstrated, Adams’s preoccupation with aristocracy - and its malignant twin, oligarchy - in the Defense and Discourses reveals not a fondness for, but rather a grave fear of, oligarchic power in American society. While democratic republican reformers like Jefferson believed that America would weed out the roots of ancient and corrupt oligarchic institutions and cultivate the seeds of a truly meritocratic and virtuous elite, Adams was doubtful. According to Adams, the deep, social psychological roots of authority would give rise to a “natural aristocracy” not of the wise, talented, and virtuous, but rather of the beautiful, well-born, and wealthy. What is more, this national aristocracy would not only survive, but thrive if left unchanged, all to the detriment of the republic. Adams approached moral philosophy as more than an academic guide to the human psyche. He made it a crucial link between the “phenomena of social life and the problems of political power” that enabled him to advance a unique conception of oligarchy.

Adam Smith’s America: How a Scottish Philosopher became an Icon of American Capitalism by Glory M. Liu (2021).

[I may add to this post later, as I have been wanting to do a longer post summarizing/explaining why the Hamilton/Adams relationship was the way it was.]

To understand the differences between Adams and Hamilton, one first has to start with an understanding of the differences between the New England colonies, the Middle/Mid-Atlantic colonies, and the Southern colonies. (American schools start teaching about the differences between the colonies in elementary/middle school - so I’m not sure if the very crude summary that follows is even necessary - and there are entire books on this topic). These were separate societies. (Leaving out the Southern colonies) we have the Germans, Dutch, and English in PA/NY/NJ/DE vs the Puritan descendant Massachusetts colonists. The founders of these colonies were different groups of people: they differed economically, in religious beliefs, in the structure of society, in attitudes on a range of subjects, etc. A ‘tolerant’ society focused on profit - the Dutch traded weapons to the Native Americans that they in turn used to raid NE towns - vs the fiercely independent and religious communities of NE. A people who saw themselves in America seeking freedom (NE) vs disparate peoples in America seeking profit (Middle). NE did not have farmland that could support large agricultural operations - family farms were most common. In contrast, NY/NJ was governed by a slave-owning, Dutch and English aristocracy, heavily involved in trade of wheat (the breadbasket of N. America), fur and lumber for West Indian sugar. William Duer, who marries into the Livingston family, spent part of his early adulthood running his family estate in the West Indies; an entire branch of the prestigious Cruger family were NY-West Indian merchants. This latter group pushed Hamilton to the forefront of national politics.

The anger NEnglanders held against the Middle colonists for their interactions with Native Americans (the French and Indian War played no small part in hatred) and their bias based on moral deficits lasts straight through the AmRev - Albany was considered practically a den of sin by NE soldiers, who also, of course, were horrified to be under the charge of Philip Schuyler. One of the reasons for Schuyler’s removal as commander of the Northern Dept was exactly this political concern. When we read several accounts of Schuyler as aristocratic, this is NE bias at work, too, against a ‘Dutch’ large landowner, wealthy slave holder, and prominent trader of West Indian goods.

And then Hamilton enters the picture. Adams may have disliked him because he’s an upstart - someone who rose very quickly in the early national political scene through his support from and for the Dutch slave-owning aristocracy, while Adams labored for decades supporting the nascent country with a political philosophy he found far more principled - but there were also real differences in interests and philosophy. And AH did very little to reduce any suspicion. Hamilton seemed to have decided fairly early on that Adams was not of sufficient skill or integrity - and just plain did not share the same profit-loving beliefs - to play a major role in new government, so he undermined Adams, even when wholly unnecessary. (Not to say that Adams was particularly adept in his roles as V. President and President, either.) Adams regarded Hamilton’s economic plans as harmful to the poor (they were) and designed to further enrich the wealthy (they did). Adams absolutely recognized Hamilton for the warmonger he was.

Hamilton meddles almost immediately against Adams - ensuring that he’d get few electoral votes in 1789, when the election of Washington wasn’t even in question. He wanted Adams to lose the election of 1796, throwing his support behind Pinckney instead. With an aim of not disrupting the continuity the new nation experienced under Washington, Adams kept most of the same cabinet members, only to have AH use those members to run the gov’t behind Adams’s back. Let’s not even get into AH’s machinations during the Quasi-War. In a long list of ways, Hamilton was duplicitous towards Adams before outright challenging him. And then Hamilton had the nerve to claim a superior moral character to Adams in 1800 in his pamphlet shared with other members of the Federalist party. There was a lot of underhandedness going on from AH. This again is an example of Hamilton’s invincible belief in his own rightness.

That said, Adams had no extraordinary interest in Hamilton’s personal life beyond the fairly common staunch Calvinist point-of-view that a deficient family background brought about a deficient moral character, void of virtue and reason, and therefore unfit to lead. Nor was Adams singular in his concern about the talent, reason, and virtues - the character - of major political players - these concerns take up a lot of ink in this period of time because of the prevalent moral and political philosophies. Who should be leaders? Who should vote? To the extent that Adams shared the common Federalist belief that a natural aristocracy was composed of men reliant on reason and virtue, Hamilton, by way of his illegitimate birth in the West Indies, was never going to fit the ideal. And Hamilton certainly lived up (or down?) to that negative reputation of being primarily interested in benefiting the wealthy and the well-born, and then a confirmed adulterer. But Adams could be fairly publicly moderate with men with whom he held private disagreements (Franklin!). He even seems to have had a good opinion of Philip Schuyler, as I recall one of the things Adams wanted to do was to name Philip Schuyler and others holding the rank of General at the time of the end of the AmRev to positions of formal leadership in 1798-99, and was baffled at Hamilton elevating himself and all his cronies.

Once Hamilton was dead, Adams (who turned 70 in 1805) seemed to enjoy making up additional gossip about him - we have no record, for example, of anyone else stating that Hamilton was an opium addict. We also have no record of anyone else stating that Hamilton was having affairs with all his sisters-in-law. But Adams also wasn’t publicly publishing this stuff - it’s in his correspondence to select others.

All that said, Adams really should be more popular than Hamilton - Adams really was an anti-slavery Founding Father; though he was not an abolitionist, he offered them his support. He was closer to a political moderate (in modern parlance) than Hamilton. And he rightly identified the oligarchic plan that underlay the High Federalists’ vision, although he certainly wasn’t a populist, either.

There’s a lot more historical context than just personality differences between personages. And there’s a lot more understanding of political and moral philosophies of the time that is needed before speculating about the whats and whys of Adams’s behavior (or speculation about Washington’s reactions to additional speculation). Warning, lecture here: Folks have dedicated their professional lives to understanding some of these topics, and we need to show greater interest in what they have found and reframe our opinions accordingly.

This is horribly brief and reductive and I can already see the simplifications that will lead to errors, and I may expand on it later, but it gets some general thoughts down.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

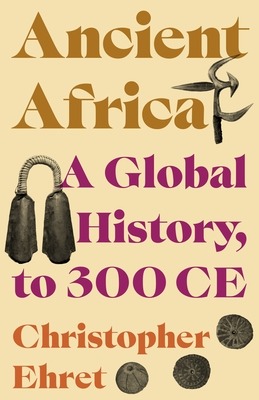

New Title Tuesday: History Recommendations

Ancient Africa by Christopher Ehret

This book brings together archaeological and linguistic evidence to provide a sweeping global history of ancient Africa, tracing how the continent played an important role in the technological, agricultural, and economic transitions of world civilization. Christopher Ehret takes readers from the close of the last Ice Age some ten thousand years ago, when a changing climate allowed for the transition from hunting and gathering to the cultivation of crops and raising of livestock, to the rise of kingdoms and empires in the first centuries of the common era.

Ehret takes up the problem of how we discuss Africa in the context of global history, combining results of multiple disciplines. He sheds light on the rich history of technological innovation by African societies - from advances in ceramics to cotton weaving and iron smelting - highlighting the important contributions of women as inventors and innovators. He shows how Africa helped to usher in an age of agricultural exchange, exporting essential crops as well as new agricultural methods into other regions, and how African traders and merchants led a commercial revolution spanning diverse regions and cultures. Ehret lays out the deeply African foundations of ancient Egyptian culture, beliefs, and institutions and discusses early Christianity in Africa.

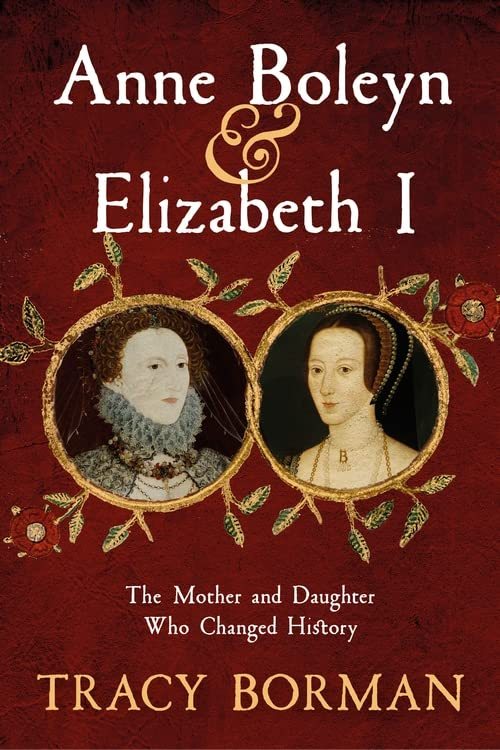

Anne Boleyn & Elizabeth I by Tracy Borman

Anne Boleyn is a subject of enduring fascination. By far the most famous of Henry VIII's six wives, she has inspired books, documentaries and films, and is the subject of intense debate even today, almost 500 years after her violent death. For the most part, she is considered in the context of her relationship with Tudor England's much-married monarch. Dramatic though this story is, of even greater interest - and significance - is the relationship between Anne and her daughter, the future Elizabeth I. Elizabeth was less than three years old when her mother was executed. Given that she could have held precious few memories of Anne, it is often assumed that her mother exerted little influence over her.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Piecing together evidence from original documents and artefacts, this book tells the fascinating, often surprising story of Anne Boleyn's relationship with, and influence over her daughter Elizabeth. In so doing, it sheds new light on two of the most famous women in history and how they changed England forever.

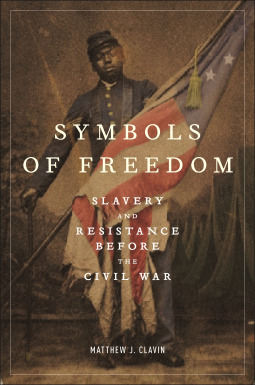

Symbols of Freedom by Matthew J. Clavin

In the early United States, anthems, flags, holidays, monuments, and memorials were powerful symbols of an American identity that helped unify a divided people. A language of freedom played a similar role in shaping the new nation. The Declaration of Independence’s assertion “that all men are created equal,” Patrick Henry’s cry of “Give me liberty, or give me death!,” and Francis Scott Key’s “star-spangled banner” waving over “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” were anthemic celebrations of a newly free people. Resonating across the country, they encouraged the creation of a republic where the right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” was universal, natural, and inalienable.

For enslaved people and their allies, the language and symbols that served as national touchstones made a mockery of freedom. Deriding the ideas that infused the republic’s founding, they encouraged an empty American culture that accepted the abstract notion of equality rather than the concrete idea. Yet, as award-winning author Matthew J. Clavin reveals, it was these powerful expressions of American nationalism that inspired forceful and even violent resistance to slavery.

Symbols of Freedom is the surprising story of how enslaved people and their allies drew inspiration from the language and symbols of American freedom. Interpreting patriotic words, phrases, and iconography literally, they embraced a revolutionary nationalism that not only justified but generated open opposition. Mindful and proud that theirs was a nation born in blood, these disparate patriots fought to fulfill the republic’s promise by waging war against slavery.

In a time when the US flag, the Fourth of July, and historical sites have never been more contested, this book reminds us that symbols are living artifacts whose power is derived from the meaning with which we imbue them.

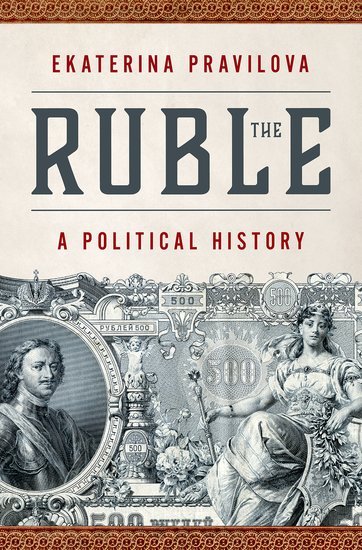

The Ruble by Ekaterina Pravilova

Money seems passive, a silent witness to the deeds and misdeeds of its holders, but through its history intimate dramas and grand historical processes can be told. So argues this sweeping narrative of the ruble's story from the time of Catherine the Great to Lenin.

The Russian ruble did not enjoy a particularly reputable place among European currencies. Across two hundred years, long periods of financial turmoil were followed by energetic and pragmatic reforms that invariably ended with another collapse. Why did a country with an industrializing economy, solid private property rights, and (until 1918) a near perfect reputation as a rock-solid repayer of its debts stick for such a prolonged period with an inconvertible currency? Why did the Russian gold standard differ from the European model

In answering these questions, Ekaterina Pravilova argues that politics and culture must be considered alongside economic factors. The history of the Russian ruble offers an opportunity to explore the political reasons behind the preservation of a supposedly backward financial system and to show how politicians used monetary reforms to block or enact political transformations.

#history#nonfiction books#nonfiction#new books#reading recommendations#reading recs#book recommendations#book recs#library books#tbr#tbrpile#to read#booklr#book tumblr#book blog#library blog#readers advisory

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress adopts the Declaration of Independence, which proclaims the independence of the United States of America from Great Britain and its king.

The declaration came 442 days after the first volleys of the American Revolution were fired at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts and marked an ideological expansion of the conflict that would eventually encourage France’s intervention on behalf of the Patriots.

The first major American opposition to British policy came in 1765 after Parliament passed the Stamp Act, a taxation measure to raise revenues for a standing British army in America. Under the banner of “no taxation without representation,” colonists convened the Stamp Act Congress in October 1765 to vocalize their opposition to the tax.

With its enactment in November, most colonists called for a boycott of British goods, and some organized attacks on the customhouses and homes of tax collectors. After months of protest in the colonies, Parliament voted to repeal the Stamp Act in March 1766.

Why did the American Colonies declare independence?

Most colonists continued to quietly accept British rule until Parliament’s enactment of the Tea Act in 1773, a bill designed to save the faltering East India Company by greatly lowering its tea tax and granting it a monopoly on the American tea trade.

The low tax allowed the East India Company to undercut even tea smuggled into America by Dutch traders, and many colonists viewed the act as another example of taxation tyranny. In response, militant Patriots in Massachusetts organized the “Boston Tea Party,” which saw British tea valued at some 18,000 pounds dumped into Boston Harbor.

The British Parliament, outraged by the Boston Tea Party and other blatant acts of destruction of British property, enacted the Coercive Acts, also known as the Intolerable Acts, in 1774. The Coercive Acts closed Boston to merchant shipping, established formal British military rule in Massachusetts, made British officials immune to criminal prosecution in America, and required colonists to quarter British troops.

The colonists subsequently called the first Continental Congress to consider a united American resistance to the British.

With the other colonies watching intently, Massachusetts led the resistance to the British, forming a shadow revolutionary government and establishing militias to resist the increasing British military presence across the colony.

In April 1775, Thomas Gage, the British governor of Massachusetts, ordered British troops to march to Concord, Massachusetts, where a Patriot arsenal was known to be located. On April 19, 1775, the British regulars encountered a group of American militiamen at Lexington, and the first shots of the American Revolution were fired.

Initially, both the Americans and the British saw the conflict as a kind of civil war within the British Empire: To King George III it was a colonial rebellion, and to the Americans it was a struggle for their rights as British citizens.

However, Parliament remained unwilling to negotiate with the American rebels and instead purchased German mercenaries to help the British army crush the rebellion. In response to Britain’s continued opposition to reform, the Continental Congress began to pass measures abolishing British authority in the colonies.

How did the American Colonies declare independence?

In January 1776, Thomas Paine published “Common Sense,” an influential political pamphlet that convincingly argued for American independence and sold more than 500,000 copies in a few months. In the spring of 1776, support for independence swept the colonies, the Continental Congress called for states to form their own governments, and a five-man committee was assigned to draft a declaration.

The Declaration of Independence was largely the work of Virginian Thomas Jefferson. In justifying American independence, Jefferson drew generously from the political philosophy of John Locke, an advocate of natural rights, and from the work of other English theorists.

The first section features the famous lines, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The second part presents a long list of grievances that provided the rationale for rebellion.

When did American colonies declare independence?

On July 2, 1776, the Continental Congress voted to approve a Virginia motion calling for separation from Britain. The dramatic words of this resolution were added to the closing of the Declaration of Independence. Two days later, on July 4, the declaration was formally adopted by 12 colonies after minor revision. New York approved it on July 19. On August 2, the declaration was signed.

The Revolutionary War would last for five more years. Yet to come were the Patriot triumphs at Saratoga, the bitter winter at Valley Forge, the intervention of the French, and the final victory at Yorktown in 1781. In 1783, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris with Britain, the United States formally became a free and independent nation.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

G.1.4 Why is the social context important in evaluating Individualist Anarchism?

When reading the work of anarchists like Tucker and Warren, we must remember the social context of their ideas, namely the transformation of America from a pre-capitalist to a capitalist society. The individualist anarchists, like other socialists and reformers, viewed with horror the rise of capitalism and its imposition on an unsuspecting American population, supported and encouraged by state action (in the form of protection of private property in land, restricting money issuing to state approved banks using specie, government orders supporting capitalist industry, tariffs, suppression of unions and strikes, and so on). In other words, the individualist anarchists were a response to the social conditions and changes being inflicted on their country by a process of “primitive accumulation” (see section F.8).

The non-capitalist nature of the early USA can be seen from the early dominance of self-employment (artisan and peasant production). At the beginning of the 19th century, around 80% of the working (non-slave) male population were self-employed. The great majority of Americans during this time were farmers working their own land, primarily for their own needs. Most of the rest were self-employed artisans, merchants, traders, and professionals. Other classes — employees (wage workers) and employers (capitalists) in the North, slaves and planters in the South — were relatively small. The great majority of Americans were independent and free from anybody’s command — they owned and controlled their means of production. Thus early America was, essentially, a pre-capitalist society. However, by 1880, the year before Tucker started Liberty, the number of self-employed had fallen to approximately 33% of the working population. Now it is less than 10%. [Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis, Schooling in Capitalist America, p. 59] As the US Census described in 1900, until about 1850 “the bulk of general manufacturing done in the United States was carried on in the shop and the household, by the labour of the family or individual proprietors, with apprentice assistants, as contrasted with the present system of factory labour, compensated by wages, and assisted by power.” [quoted by Jeremy Brecher and Tim Costello, Common Sense for Hard Times, p. 35] Thus the post-civil war period saw “the factory system become general. This led to a large increase in the class of unskilled and semi-skilled labour with inferior bargaining power. Population shifted from the country to the city … It was this milieu that the anarchism of Warren-Proudhon wandered.” [Eunice Minette Schuster, Native American Anarchism, pp. 136–7]

It is only in this context that we can understand individualist anarchism, namely as a revolt against the destruction of working-class independence and the growth of capitalism, accompanied by the growth of two opposing classes, capitalists and proletarians. This transformation of society by the rise of capitalism explains the development of both schools of anarchism, social and individualist. “American anarchism,” Frank H. Brooks argues, “like its European counterpart, is best seen as a nineteenth century development, an ideology that, like socialism generally, responded to the growth of industrial capitalism, republican government, and nationalism. Although this is clearest in the more collectivistic anarchist theories and movements of the late nineteenth century (Bakunin, Kropotkin, Malatesta, communist anarchism, anarcho-syndicalism), it also helps to explain anarchists of early- to mid-century such as Proudhon, Stirner and, in America, Warren. For all of these theorists, a primary concern was the ‘labour problem’ — the increasing dependence and immiseration of manual workers in industrialising economies.” [“Introduction”, The Individualist Anarchists, p. 4]

The Individualist Anarchists cannot be viewed in isolation. They were part of a wider movement seeking to stop the capitalist transformation of America. As Bowles and Ginitis note, this “process has been far from placid. Rather, it has involved extended struggles with sections of U.S. labour trying to counter and temper the effects of their reduction to the status of wage labour.” The rise of capitalism “marked the transition to control of work by nonworkers” and “with the rise of entrepreneurial capital, groups of formerly independent workers were increasingly drawn into the wage-labour system. Working people’s organisations advocated alternatives to this system; land reform, thought to allow all to become an independent producer, was a common demand. Worker co-operatives were a widespread and influential part of the labour movement as early as the 1840s … but failed because sufficient capital could not be raised.” [Op. Cit., p. 59 and p. 62] It is no coincidence that the issues raised by the Individualist Anarchists (land reform via “occupancy-and-use”, increasing the supply of money via mutual banks and so on) reflect these alternatives raised by working class people and their organisations. Little wonder Tucker argued that:

“Make capital free by organising credit on a mutual plan, and then these vacant lands will come into use … operatives will be able to buy axes and rakes and hoes, and then they will be independent of their employers, and then the labour problem will solved.” [Instead of a Book, p. 321]

Thus the Individualist Anarchists reflect the aspirations of working class people facing the transformation of an society from a pre-capitalist state into a capitalist one. Changing social conditions explain why Individualist Anarchism must be considered socialistic. As Murray Bookchin noted:

“Th[e] growing shift from artisanal to an industrial economy gave rise to a gradual but major shift in socialism itself. For the artisan, socialism meant producers’ co-operatives composed of men who worked together in small shared collectivist associations, although for master craftsmen it meant mutual aid societies that acknowledged their autonomy as private producers. For the industrial proletarian, by contrast, socialism came to mean the formation of a mass organisation that gave factory workers the collective power to expropriate a plant that no single worker could properly own. These distinctions led to two different interpretations of the ‘social question’ … The more progressive craftsmen of the nineteenth century had tried to form networks of co-operatives, based on individually or collectively owned shops, and a market knitted together by a moral agreement to sell commodities according to a ‘just price’ or the amount of labour that was necessary to produce them. Presumably such small-scale ownership and shared moral precepts would abolish exploitation and greedy profit-taking. The class-conscious proletarian … thought in terms of the complete socialisation of the means of production, including land, and even of abolishing the market as such, distributing goods according to needs rather than labour … They advocated public ownership of the means of production, whether by the state or by the working class organised in trade unions.” [The Third Revolution, vol. 2, p. 262]

So, in this evolution of socialism we can place the various brands of anarchism. Individualist anarchism is clearly a form of artisanal socialism (which reflects its American roots) while communist anarchism and anarcho-syndicalism are forms of industrial (or proletarian) socialism (which reflects its roots in Europe). Proudhon’s mutualism bridges these extremes, advocating as it does artisan socialism for small-scale industry and agriculture and co-operative associations for large-scale industry (which reflects the state of the French economy in the 1840s to 1860s). With the changing social conditions in the US, the anarchist movement changed too, as it had in Europe. Hence the rise of communist-anarchism in addition to the more native individualist tradition and the change in Individualist Anarchism itself: