#Almería province

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The title of a city was granted to Dalías by King Alfonso XIII on February 12, 1920.

#title of a city#Dalías#12 February 1920#105thanniversary#Spanish history#Almería province#Andalusia#Poniente Almeriense#small town#España#Spain#Southern Europe#Southern Spain#architecture#cityscape#travel#vacation#summer 2021#original photography#tourist attraction#landmark#Sierra Gador#Plaza de la Alameda#Mirador Ermita Santa Cruz#Church of Santa María de Ambrox de Dalías#C. Rbla. de Gracia#Ayuntamiento de Dalías#landscape

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albox, Almería, Andalusia.

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

mentally i'm here

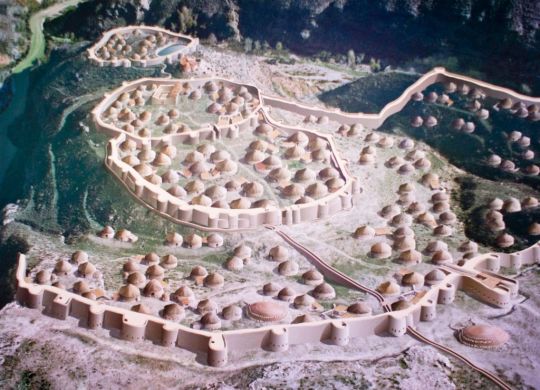

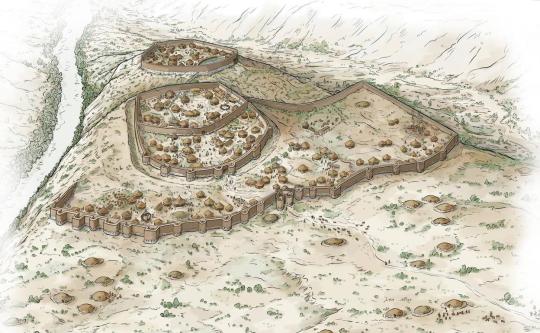

#this is the settlement of los millares :)#it is known as the first city in all of iberia#it is located in the modern province of almería and it is dated to ca. 3200 BCE !!!!#as you could imagine. as someone with almeriense ancestry. this is soooo <33333333#next time my birthday happens while we are in almería and thus i get to force my family to do anything i'm gonna force them#to visit los millares hehe

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Almería lies the world's largest concentration of commercial greenhouses, often referred to as ‘the sea of plastic’. This vast expanse of polytunnels, housing millions of kilos of fruits and vegetables mainly destined for export, stretches for hundreds of kilometers, a white panorama until the horizon. Also within this sea of plastic dwell the migrant workers who work to ensure Europe's supermarkets are stocked year-round. While they perform the vital task of ensuring Europe's all-season access to fresh produce, these workers often live in a state of physical and institutional vulnerability. This state of affairs remained largely hidden, until recent shocks like the Covid-19 pandemic and armed conflicts exposed the fragility of our food supply chains. Spain issues approximately 150,000 permits annually for seasonal laborers (European Parliament 2021). However, within just the province of Almería, there are more than 100,000 migrants working in greenhouses, 80% of them holding undocumented status in the country. This lack of legal recognition leaves the workers off official records, denying them universal rights such as labour rights and access to formal rental contracts. It is a dire situation that forces many to call the shanty towns surrounding the greenhouses their homes. During my research, I often heard how some workers pay up to 6,000 euros annually to greenhouse managers for the working contracts necessary to seek legal status in the country, turning the quest for legalization into a profitable business. Almería serves as a primary entry point for migrants traveling from West and North African countries to Europe. For those who cross the Mediterranean without visas - the majority of greenhouse laborers - this work is virtually the only option for income generation on arrival. While informal greenhouse jobs provide financial support to workers and their families back in their home countries, they also perpetuate vulnerability in livelihoods and employment, highlighting and embedding a stark contrast between EU citizens enjoying affordable food and the undocumented migrant workers compelled to work in precarious conditions to provide it.

145 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello nyúl, am here to request a foreigner (spanish) reader who is in Korea for Uni and starts dating school president dahyun but a year into a relationship reader starts missing home and dahyun ends up calling readers parents to help her make all of readers hometown food or foods from there childhood and when reader gets home they are surprised by this gestured by ends up loving it of course, then you can make it even fluffier by dahyun giving YN 2 tickets back to Spain for the summer holiday as a surprise present

Hey! How are you doing? <3

You always send me good ideas and request for fics, thank you very much 🥺🩷 I know I still have some of your requests pending, and I'm slowly working on it! In the meantime, I hope you enjoy this ( ◜‿◝ )♡

There is no place like home

School president! Dahyun x Spanish exchange student! reader

tags: College AU! fluff.

notes: fem pronouns used!

For someone born and raised in Mojácar, a small city in the province of Almería, embarking on the exciting experience of studying in Korea, particularly in the vibrant and enormous Seoul, was practically a dream.

So shortly after your arrival, the immensity of said culture immersed you in an absolutely unknown world, where the main difficulty had been from the beginning the language barrier (because let's be honest, at the beginning you couldn't pronounce annyeonghaseyo correctly not even to save your life), although soon, between classes and new faces, you caught the attention of Dahyun, the class president.

And well, how could you not catch her attention? You always seemed like a lost puppy hanging around the hallways, speaking a language practically unknown to her, and for god's sake, it surprisingly made you look adorable doing it.

But again, and just as from the beginning, the language barrier presented itself as a challenge, so the interactions between you and her were mostly simple greetings and smiles. Because you couldn't speak Korean to save your life, nor could she speak Spanish. However, as the days went by, the spark overcame problems as earthly as a linguistic obstacle, through patience and friendly gestures, dissolving the difficulty of her first encounters.

Because beyond that, you and Dahyun had learned to communicate through gestures, shared laughter, and genuine expressions. The connection grew day by day, turning their friendship into something deeper and more meaningful. And of course, over time you learned one or another Korean expression or sentence, purely through the process of adapting to the environment, but it was no longer crucial. You told each other everything, without saying a word.

And as your friendship intensified, excitedly sharing your Spanish roots with Dahyun, as well as the tenderness of discovering Korean traditions together, the sum of each and every one of those experiences strengthened their connection.

Which wreaked new havoc on you.

So after some time, you felt trapped in a whirlwind of emotions. The attraction grew, and every moment with Dahyun was a rollercoaster of sensations: you felt fascinated by Dahyun's vibrant energy, her infectious joy, and the way she lit up any place with her presence; You felt anticipation for her text messages, or you got giggles and butterflies in your stomach when you looked at each other.

All of that was, according to you, the worst and at the same time the best that could happen to you. You loved being by her side, but you also feared the always possible probability of a one-sided love.

Except it wasn't a one-sided love.

Although you didn't know it yet.

Because the turning point came on a starry night, during one of the now routine night walks through Seoul, when Dahyun, with a special shine in her eyes and her heart beating strongly against her ribs, confessed her feelings for you. It was a moment full of nervousness, because the words were different, they were another language, but the sparkle in your eyes revealed those same passionate feelings and finally, love resonated clearly.

//

But after a year of shared laughter, walks around the city, and mutual support, you began to experience a quiet melancholy. You were nostalgic for your home in Spain, longing for the familiar streets of Mojácar, as well as the aromas of your mamá 's cooking and the comforting meals she prepared in your childhood, remembering how she used to say that 'the cuisine of Mojácar is the best exponent of the gastronomic tradition of the Costa de Almería'.

And for Dahyun, who never took her eyes off you (because deep in her heart, she still associated you with the image of the adorable lost puppy wandering the college hallways, which was what she saw when she met you for the first time), she clearly observed the melancholy in your eyes and didn't need to ask anything about it. Sje just knew it.

And with ingenuity and determination, Dahyun decided to take action. So while she was slowly laying out a plan that she hoped would cheer you up, one day while you two were sharing a quiet walk around campus, Dahyun took your phone with a mischievous smile.

“Would you mind if I took your emergency number? You never know when we might need it,” Dahyun said, playfully.

Without even thinking and with a giggle, you gave her the phone number she had asked for. Anyway, you thought it was always good to have someone other than yourself have your emergency contact, just as a precaution. You never know, right?

And of course, what you didn't know on that occasion was that Dahyun was planning something special. That night after Uni, Dahyun discreetly left to make an international call.

"Hola, es esta la casa de reader? Uhm, soy Dahyun y, uh, su hija y yo hemos estado saliendo por un año y poco más. Llamé porque me gustaría conversar una situación con ustedes" Dahyun explained respectfully, using the Spanish she had learned.

So, after a pleasant conversation (and less difficult than Dahyun expected, given her little knowledge of Spanish), she shared her idea with your parents. Together, they created a plan to transform your dorm room into a piece of Spain. Your parents' help was very useful for Dahyun, being able to recover numerous family recipes, details about your home, and anecdotes that only your true friends could know.

So with information in hand, Dahyun gave free rein to her efforts for the surprise. Since you and Dahyun did not coincide in all classes, since academically you had different interests, consequently you two had different class dismissal times. And that day, after the end of her classes, Dahyun had run to your dorm room while you would still be engrossed in your studies for about two more hours.

You had a kitchen in your small dorm room, but you didn't usually use it, since you had little or practically no time to cook something decent, and therefore, you tended to eat with Dahyun outside or heat up microwave dinners; so at that moment, Dahyun had your entire kitchen to herself and she was ready to get to work.

The first task that Dahyun set himself was to prepare Ajo Colorao, a typical dish in almost the entire province of Almería, including Mojácar, your hometown, and which you had stated more than once that you loved to eat. So in the kitchen, and with the ingredients scattered all over the counter, Dahyun immersed herself in the process. First she prepared Ajo Colorao, a dish that, according to your parents had explained to her during the phone call, is made up of a puree that has the consistency of a salmorejo and where cooked potatoes are combined with desalted cod, chorizo pepper, garlic, tomato and cumin, and that you particularly liked to accompany with bollo de panizo, a typical bread from Almería.

Then, the second masterpiece on her gastronomic list was Patatas in ajopollo, a dish that reminded you of Sunday lunches, characterized by family reunion and togetherness, as well as shared laughter. Dahyun remembered that your parents had told her that the trick for this recipe was to first brown the bread, almonds and garlic in a frying pan with oil at low temperature until it turned golden brown, and then mash everything in a mortar until it was obtained a a soft, but thick mixture. Soon she understood that this pasty mixture was 'ajopollo', and that it accompanied the potatoes.

The aroma that filled the kitchen while Dahyun prepared your favorite dishes evoked the homely memories of your childhood in Mojácar and while now she was cooking the papaviejos —a typical dessert from Almería, preferred by the little ones, and whose ingredients simply consisted of potatoes, milk , flour and sugar—, she reflected on the connection she had built with you since you two had been dating, more than a year ago. Dahyun had the feeling that with each ingredient that fell into the pan it not only seemed to carry with it the very essence of your hometown, but also your happiness. She had noticed how homesick you had been lately, and this surprise was intended to do just that.

Make you happy.

Because if Dahyun loved something about you dearly, it was your smile.

With that in mind, Dahyun checked the clock, taking note that it was almost time for you to return to your room after classes. And it was just in time, because a few minutes later, she heard the slight struggle while you inserted the key, and then a 'click' when removing the lock. You paused for a moment, noticing a familiar scent hanging in the air.

And then, as you opened the door, the sight of the unfolding in front of you, left you speechless. Dahyun had transformed your modest room into a corner of Mojácar in the heart of Korea.

Dahyun, with a nervous and anticipatory smile, was waiting for you standing next to the table. Her eyes shone with a mixture of excitement and anxiety, while she held an apron that revealed her as the author of this surprise feast.

"Welcome home!" Dahyun exclaimed happily when you entered. Your eyes met and the knowing glow between them conveyed the affection and dedication she had invested in this surprise.

Your heart skipped a beat when you saw the incredible surprise Dahyun had prepared for you. In turn, your face lit up with a mixture of surprise and excitement, and your eyes shone as you recognized every detail that evoked your distant home.

"Dahyun, how...?" You murmured, not finding the right words to express your gratitude.

The table was decorated with details reminiscent of Mojácar, from small flags to photos of local landscapes. Dahyun had learned a lot about your culture and wanted you to feel a piece of home in that moment.

"Do you like it?" Dahyun asked, her eyes shining with hope while pointing to the plates.

You nodded, unable to contain your excitement. You approached the table and looked at each dish in awe, and Dahyun, with her apron on, began to describe each dish excitedly, revealing how she had contacted your parents for authentic recipes and cooking tips.

The table was full of delicacies, from succulent Patatas en ajopollo to the Ajo Colorao that you remembered with nostalgia. There were even papaviejos, your favorite childhood dessert, perfectly golden and sprinkled with sugar.

And as you ate each dish, you felt your eyes filled with tears of gratitude. Every bite reminded you of home, your mother's kitchen, and the family meals you had missed so much. Dahyun, carefully observing your every reaction, was satisfied to see that her surprise was achieving the desired effect.

But just when Dahyun couldn't feel happier and prouder of her small achievement, and after finishing dinner, you got up to hug her tightly.

“I can’t believe you did all this for me,” you said, your voice filled with emotion. "You're amazing, Dahyun."

Dahyun reciprocated the hug, feeling your heartbeat. “Your happiness is mine,” Dahyun whispered. "And even though we are far from Mojácar, I want you to feel like you have a home here with me."

But the surprise didn't end there! There was more!

Because while Dahyun shared with you a handful of churros, which she had personally gone to buy at a Spanish place in the area, she handed you an envelope containing tickets back to Spain for the summer vacation.

"I want you to have the opportunity to hug your family and enjoy meals from home in person," Dahyun expressed, her eyes shining. She then came up to kiss you gently on the forehead, on the nose, on the cheeks. She practically drew a map of kisses on your face, and you let her do it.

And so, between traditional dishes and affectionate gestures, another chapter of your story with Dahyun was woven, a story that transcended borders and demonstrated that home is not always in a physical place, but in the shared heart.

Dahyun was your home.

And that being the case, there is no place like home.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

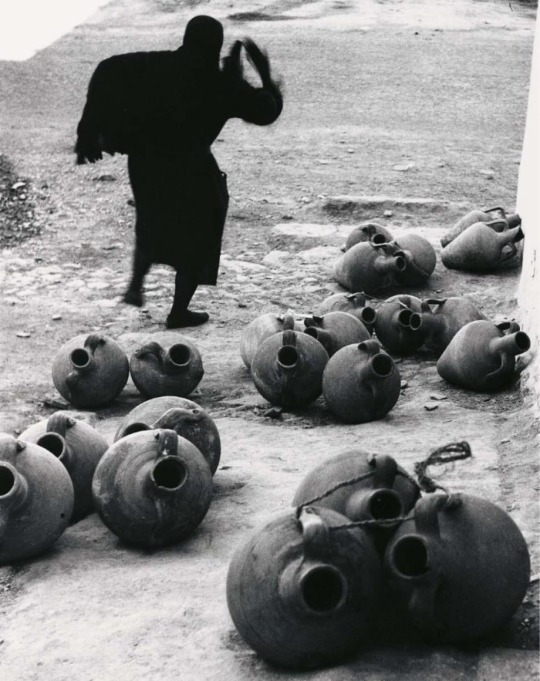

Tabernas, Almería province, Spain. c.1962

By: Carlos Pérez Siquier

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Almeria Greenhouses

The greenhouse complex that covers about 100 square miles in the province of Almería, Andalucía, Spain, is visible from space.

0 notes

Text

I’m sure a lot more things happened in the year of our Lord 1804,

but think about this for a second. The Burr-Hamilton duel happened July 10th. An earthquake occurred along the Cabo de Gata close to the Province of Almería in Spain August 25th. This was the time Commodore Samuel Barron and his new squadron came to relieve Commodore Edward Preble of the Mediterranean squadron. The policy of paying tribute to the Barbary pirates was coming to an end. Napoleon’s coronation was on December 2nd. This was a year of earth shaking events.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tolerance Project Extra

The Good The Bad and the Ugly Part 2

Introduction

Welcome to the 2nd Chapter in an epic blog that covers the classic Western The Good the bad and the ugly this 2nd half of the making of the film covers the locations and the excellent film score.

Shooting The Good the Bad and the ugly the locations

Directed by Sergio Leone, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is a quintessential spaghetti Western film. Like other films in the popular genre, the 1966 epic was mostly filmed on location in various European countries. Although The Good, the Bad and the Ugly's filming locations aren't actually in the American West, Leone's classic captures a striking authenticity. Led by Western movie star Clint Eastwood as "the Good," Lee Van Cleef as "the Bad," and Eli Wallach as "the Ugly," the film sees the three titular gunslingers fighting over a buried cache of Confederate gold during the American Civil War.

Billed as the third installment in the Dollars Trilogy, the film launched Eastwood's career to new heights, and garnered a then-impressive $38 million at the worldwide box office. Filled with duels and violent conflicts, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly features Leone's signature use of long shots and close-ups, all of which helps the accomplished director build the Western's searing, slow-burn tension. Not only does the film feature many of Leone's hallmarks, but it's perhaps the definitive spaghetti Western film. Filled with iconic scenes, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly's filming locations are equally memorable.

The Good the Bad and the ugly Monastery and Desert work scenes were all filmed in the same area of Spain Cabo de Gata Almera Andalucia

An Italian-led production, The Good, The Bad and The Ugly also had co-producers in Spain, West Germany, and the United States. By and large, most of the filming for the spaghetti Western took place in Spain. The film's monastery and long desert walk scenes, for example, were filmed in the same area of the country — Cabo de Gata, Almería in Andalucía. Set in the US, the movie uses Spain's scenic landscapes to serve as believable stand-ins. Tuco force-marching Blondie across the desert is an incredibly visceral sequence, and the filming location augments that feeling

The Westerns Battle at Langstone Bridge Over the Arlanza River was also shot in Spain

While gunfights and duels are a crucial part of Clint Eastwood's definitive spaghetti Western, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is also packed with traditional battle sequences. Set during the American Civil War, the film uses the nation-shaping conflict to augment its tense atmosphere and sense of looming menace. In the movie, there's a famous battle scene between the Confederate and Union armies — the Battle at Langstone Bridge. In reality, the battle scene was shot along a particular stretch of the Arlanzon River in Spain.

The Good the Bad and the Ugly Bridge Explosion scene was also filmed on location

Filmed in the Almeria province of Spain, one of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly's most memorable scenes features a town besieged by cannon fire. During the course of the conflict, a bridge connecting the Union and Confederate camps is rigged with explosives and blown up by Blondie and Tuco. In the aftermath of the first take, Leone realized that reshoots were necessary, as three of the production's cameras were destroyed during the intense sequence. With the desert walk scene also being filmed in Almeria, the province's many scenic backdrops add a satisfying continuity to the film's setting

The Rail Road scene featured in the Good The Bad and the Ugly was filmed outside of Granada

At one point during the film, Tuco has a memorable moment involving railroad tracks, a corpse, and a high-speed train. Full of suspense, the railroad sequence was filmed at the Estación de Calahorra in La Calahorra, Guadix — a spot located roughly midway between the well-known Spanish cities of Granada and Seville. With impressive brickwork and a red-tiled roof, the station is a perfect stand-in for the Spanish-inspired architecture of the American Southwest. That said, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly makes great use of its filming locations — even if they were an ocean away from where the movie is set.

The Films Finale was shot at the Sad Hill Cemetery in Spain

Perhaps the most well-known scene in the entire film, the cemetery scene from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly was filmed at Sad Hill. The Spanish cemetery, which is tucked away in a small, rock-enclosed valley, is shockingly reminiscent of the landscapes found in the American West. During the sequence, Blondie and Angel Eyes commence a tense showdown while Tuco watches. To transform the location into an authentic setting for the film's iconic climax, Leone ordered that 10,000 empty graves be built on the land.

The Music

The score is composed by frequent Leone collaborator Ennio Morricone. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly broke previous conventions on how the two had previously collaborated. Instead of scoring the film in the post-production stage, they decided to work on the themes together before shooting had started, this was so that the music helped inspire the film instead of the film inspiring the music. Leone even played the music on set and coordinated camera movements to match the music.

The unique vocals of Edda Dell'Orso can be heard permeating throughout the composition "The Ecstasy of Gold". The distinct sound of guitarist Bruno Battisti D'Amorio can be heard in the compositions 'The Sundown' and 'Padre Ramirez'. Trumpet players Michele Lacerenza and Francesco Catania can be heard on 'The Trio'. The only song to have a lyric is 'The Story of a Soldier, the words of which were written by Tommie Connor.

[ Morricone's unmistakable original compositions, containing gunfire, whistling (by John O'Neill), and yodeling permeate the film. The main theme, resembling the howling of a coyote (which blends in with an actual coyote howl in the first shot after the opening credits), is a two-pitch melody that is a frequent motif, and is used for the three main characters. A different instrument was used for each: flute for Blondie, ocarina for Angel Eyes, and human voices for Tuco.

The score complements the film's American Civil War setting, containing the mournful ballad, "The Story of a Soldier", which is sung by prisoners as Tuco is being tortured by Angel Eyes. The film's climax, a three-way Mexican standoff, begins with the melody of "The Ecstasy of Gold" and is followed by "The Trio" (which contains a musical allusion to Morricone's previous work on For a Few Dollars More).

"The Ecstasy of Gold" is the title of a song used within The Good, The Bad and the Ugly. Composed by Morricone, it is one of his most established works within the film's score. The song has long been used within popular culture. The song features the vocals of Edda Dell'Orso, an Italian female vocalist. Alongside vocals, the song features musical instruments such as the piano, drums, and clarinets.

The song is played in the film when the character Tuco is ecstatically searching for gold, hence the song's name, "The Ecstasy of Gold". Within popular culture, the song has been utilized by such artists as Metallica, who have used the song to open up their live shows and have even covered the song. Other bands such as the Ramones have featured the song in their albums and live shows. The song has also been sampled within the genre of Hip Hop, most notably by rappers such as Immortal Technique and Jay-Z. The Ecstasy of Gold has also been used ceremoniously by the Los Angeles Football Club to open home games.

The main theme, also titled "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly", was a hit in 1968 with the soundtrack album on the charts for more than a year, reaching No. 4 on the Billboard pop album chart and No. 10 on the black album chart. The main theme was also a hit for Hugo Montenegro, whose rendition was a No. 2 Billboard pop single in 1968.

To listen to the original Good the Bad and ugly main theme by Ennio Morricone click here (6) The Good, the Bad and the Ugly • Main Theme • Ennio Morricone - YouTube to listen to the cover version by Hugo Montenegro click here "The Good, The Bad and The Ugly" by Hugo Montenegro and His Orchestra

The Collider website published an article called The 10 Best Movies Scored by Ennio Morricone, According to IMDb all the films featured in the Dollars trilogy featured in the list but it was the music for the good the bad and the ugly that got the top spot.

why did it get the number 1 spot these were their reasons why

Eastwood’s Man with No Name is back in the final film of the Dollars trilogy, The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly, set during the Civil War. The mysterious man, nicknamed Blondie, plots with a Mexican outlaw, Tuco, to turn Tuco in for the reward money, then free him, but Blondie betrays Tuco and leaves him in the desert. Tuco seeks revenge, but instead, the two men team up to find a stash of buried gold.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly is one of the most famous Westerns and is also regarded as one of the best, and the same goes for Morricone’s score. It’s iconic and beloved, with Morricone at his best. It's almost impossible to imagine any of the Dollars trilogy without Morricone’s music, but especially this one. It uses many of the same elements of the scores of the previous films, such as whistles, guitars, and vocals, but Morricone’s just about perfect the Western sound here.

Next week the final chapter the lost the good the bad and ugly sequel what is the best way to watch the trilogy and what links the film to the Tolerance project.

Pictures

1 2 and 3 the vairous locations seen in the good the bad and ugly

4 the cover for the soundtrack album

Notes Thank you to wikepedia for the background details on the music score and colidar film website for their article called The 10 Best Movies Scored by Ennio Morricone, which explains why the soundtrack to the Good the bad and ugly is excellant.

Next week Part 3 of this blog on the Good the Bad the Ugly how best to watch trilogy the lost sequel and how the film ties in with the Tolerance film

#the good the bad and the ugly#collider#google images#wikipédia#tolerance project#Tolerance Project extra blog#classic films#classic western

0 notes

Text

I’m so glad there is representation of my city In heart stopper, thank you Alice Oseman for choosing Almería out of all of Spain.

it will always be weird to me bc it’s like the most forgotten province of Spain and Andalusia and then, one of the most famous shows/books lately decided to put the grandparents of the protagonist from there. THANK YOU

When my mother and I watched the show for the first time and we saw they mentioned Almería we paused to burst out laughing bc we didn’t expect it and ran to my father to tell him. but why did she choose Almería? She must have family from here or something like that. We will never know…

anyway thank you Alice Oseman for choosing the best thing in all of Spain

#Almeria#gracias se te quiere Alice#Pero por que?#Tendrá familia de aquí seguro vamos#O vino de vacaciones y se quedó alucinando#No me extraña

0 notes

Photo

Yes the US dropped a nuclear bomb in Spain yet this map forgets to remember two very important facts about why it was not a tragedy:

-The bombs didnt explode (at least the nuclear part didnt)

-It was dropped in Almería province which wouldnt have meant a lost of human or animal life not even plant life cuz there is nothing remarkable in Almeria,

Countries on which the US 🇺🇸 has dropped a nuclear bomb.

by amazing__maps

603 notes

·

View notes

Text

The island of San Andrés was declared a natural monument by the Junta de Andalucía on October 1, 2003.

#island of San Andrés#Carboneras#natural monument#1 October 2003#travel#Almería province#Andalucía#Andalusia#Spain#España#summer 2021#vacation#Mediterranean Sea#nature reserve#beach#palm tree#Southern Spain#Southern Europe#anniversary#Spanish history#boat#Playa de Los Cocones#Playa de los Barquicos O de los Cocones#original photography#tourist attraction

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Calle las Algas, Almería, Andalusia.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

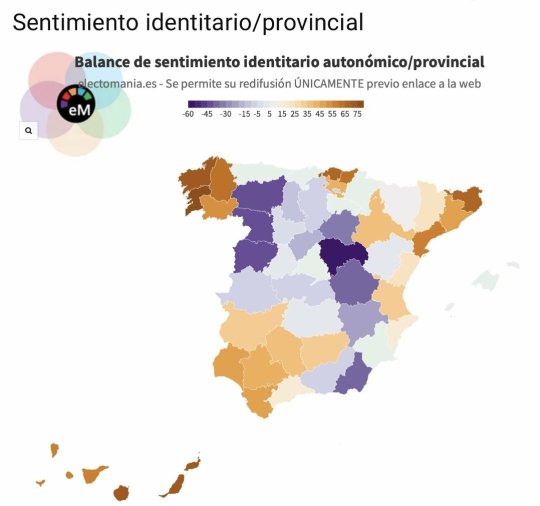

just came across this map, i think it's quite interesting! it shows the identity sentiment of pertenance to a province / autonomous community by province, in brown-ish you have those provinces where the feeling is strongest, and in blue-ish those where the feeling is lowest.

the conclusions i can get while looking at it are

galicians, catalonians, basques and canarians are the ones with the highest regional identity. that should be no surprise, it makes a lot of sense as their cultures are the most distinct

all of castile has the lowest regional identity, which also kinda make sense i guess.

you can clearly see the two largest autonomic disputes in the country: guadalajara not feeling manchego (in fact i found this map on a tweet from someone from guadalajara demanding they secede from la mancha) and the old kingdom of león (león, zamora and salamanca) not feeling castilian.

andalusia is also quite interesting to me because you can clearly see the split between western and eastern andalusia. the west feels very andalusian, while the east not so much, especially almería.

the 'neutral' ones are the most interesting to me i think. i understand why madrid is like that, and i sorta get the balearic islands as well (people there tend to identify with their island and not the autonomy?), as well as murcia (people from cartagena would rather have a province of their own) but i have no clue about most of these

feel free to add your thoughts !!!

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another Excellent Reason To Book A Trip To Andalucia: A Record Number Of Blue Flag Beaches, Marinas And Boats - Simply Shuttles

Such are the strengths of the Spanish region of Andalucia as a magnet for tourists – including its reliably warm, Mediterranean climate, as well as its picturesque scenery and fascinating cultural heritage and diversity – you might not imagine that many would-be visitors would require even more reason to arrange a holiday break here.

Indeed, the marinas, beaches and boats further add to the attraction of this part of southern Spain – and now, tourists might have been given even greater justification for arranging a spot of sightseeing in Andalucia.

Specifically – as reported by The Olive Press – Andalucia has been awarded 148 Blue Flags in 2023. This exceeds the region’s previous record, with three more flags having been gained this year than was the case in 2022.

This landmark achievement means that only one region in the whole of Spain – Valencia – now has more Blue Flags than Andalucia, which is ahead of Catalonia and Galicia on this measure.

What is the Blue Flag scheme, anyway?

If you have considered doing some sightseeing in Andalucia – or have done so in the past – you might have come across mentions of “Blue Flag beaches” or similar, and wondered what these references meant.

The short answer to this question, is that Blue Flags are voluntary awards for beaches, marinas, and sustainable tourism boats around the world.

However, it isn’t easy for such a facility to earn this sought-after ecolabel; in order for a Blue Flag to be granted, various strict environmental, educational, safety, and accessibility criteria must be satisfied, with this compliance being maintained over time.

The grand idea behind the Blue Flag programme – which was first established in 1985 – is to help connect the public with their surroundings, and to encourage them to find out more about their environment.

So, for a given site to qualify for a Blue Flag, it must make available environmental education opportunities, as well as a permanent display of information that is relevant to the site’s biodiversity, ecosystems, and environmental phenomena.

As a visitor, then, knowing that a particular amenity in one of the above categories has been awarded a Blue Flag, means you can treat this as an indicator of its quality and suitability as a tourist attraction.

Andalucia’s Blue Flag credentials are getting stronger and stronger

If there is one Spanish region – even by the usual high standards of Spanish regions – that is especially committed to complying with environmental legislation and improving the quality of its beaches, it is surely Andalucia.

Such commitment is demonstrated by the fact that while the region had some 96 Blue Flags in 2019, this number has expanded to an even more impressive 148 this year.

Of those 148 Blue Flags, 127 were granted to beaches, which is five more than last year’s number. Andalucia’s marinas, meanwhile, attracted 19 Blue Flags, and two Blue Flags were awarded to sustainable boats.

On a province-by-province level, it was Málaga that attracted the most Blue Flags of the Andalucia region – 47, to be exact, with 39 for beaches, six for ports, and two for sustainable boats. Such parts of the autonomous community as Cádiz (37 flags), Almería (33 flags), and Huelva (17 flags) also fared strongly in the rundown.

Given such numbers, it can hardly be surprising that Spain as a whole boasts the highest number of Blue Flag beaches in the world, with a total of 729, which is six more than in 2022.

So, whether you come to Andalucia’s beaches with a view to catching some rays, trying out some water sports, spending quality time with the rest of your travelling group, or something else entirely, you can be confident of having a quality experience.

Call the Simply Shuttles team today on +34 951 279 117, or send us an email, and we will be pleased to arrange the excellent-value airport and private hire transfers that could help you get even more out of your next visit to the Costa del Sol.

0 notes

Text

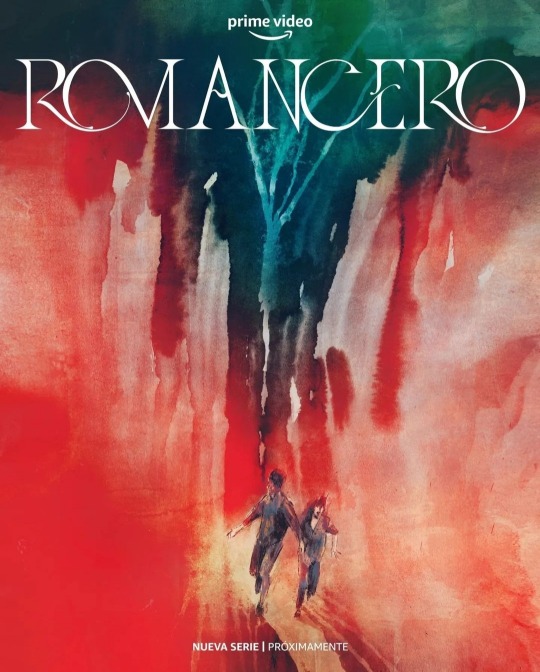

@asongofstarkandtargaryen I have found about a new upcoming horror series, Romancero.

This is the info I have found until now:

The cast of the series will be led by Sasha Cócola (Techo y comida, Los hombres de Paco) and the Serbian actress Elena Matic (Kineski zid, Bon voyage). The little that is known about the synopsis is related to its characters, since they are the ones who will give life to Jordán and Cornelia. He is not a boy and he is not a man and she is a girl whose childhood has been stolen. Turned into some strange teenagers, they decide to change their lives and flee from the desert of southern Spain, pushed by circumstances. In their escape from a cruel Andalusia, as real as it is mythical, they come across demons, witches and blood drinkers.

They are accompanied on this adventure by Belén Cuesta (La trinchera infinita, Paquita Salas, La llamada, Cristo y Rey, La casa de papel, Vis a Vis, El Aviso), Ricardo Gómez (El sustituto, La ruta, Cuéntame cómo pasó, Vivir sin permiso, La Casa entre los cáctus, 1898: Los últimos de Filipinas), Guillermo Toledo (Los favoritos de Midas, Crimen perfecto, 7 vidas, Historias de Lavapiés, Juana La Loca, Black is Beltza), the Argentinian actress Julieta Cardinali (Ecos de un crimen, Maradona: Sueño Bendito, Los ricos no piden permiso, Valentín, Carta a Eva) and Alba Flores (La casa de papel, Las cartas perdidas, El tiempo entre costuras, Vis a Vis, Sagrada familia). In addition, to complete the information about the series, Romancero will be set on locations in Almería and Madrid, two of the cities that host the filming of the fiction, in different natural settings in the province of Almería, while the interiors will be filmed in Madrid.

Jordán and Cornelia are two helpless youngsters on the run from the forces of the law, powerful supernatural creatures, and themselves. The series, which has just started filming, will consist of six episodes of 30 minutes each and its action takes place in a single night.

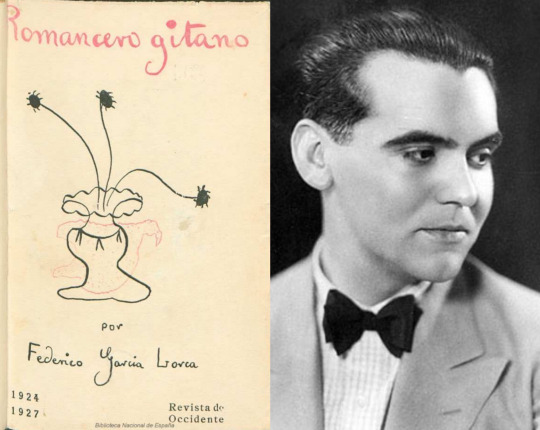

"With echoes of the famous Romancero Gitano, a poetic work by Federico García Lorca (Fuente Vaqueros, Granada, June 5 of 1898 - Víznar, Granada, August 18 of 1936), it seems that the references of Romancero will be very different from each other. Comics, Gothic literature, the stories of witches, ghosts and creatures, the poetry of Federico García Lorca or esotericism, all of this in the enveloping setting of a desert and cruel South, where the clichés of rural Spain and more cañí they coexist with supernatural creatures, violence, revenge, redemption and love”, comments the information provided. "We love that Romancero is a horror series with a strong local point of view, an approach that allows us to offer a different and updated vision of our traditions and culture," says María José Rodríguez, Head of Spanish Originals, Amazon Studios. "We want to offer the public unique stories and different voices that resonate and impact. We are convinced that Romancero will not leave anyone indifferent," says Rodríguez.

"We are very happy to work with Fernando Navarro and Tomás Peña on a project as distinctive as Romancero," James Farrell, Head of International Originals, Amazon Studios, told the press. On behalf of THE MEDIAPRO STUDIO, the producer is Laura Fdz. Espeso and Javier Méndez, Fernando Navarro, Alejandro Florez and Maya Maidagan serve as executive producers. Everyone will be looking for the new original Spanish youth horror series that will replace the gap left by El Internado: Las Cumbres in the new Prime Video catalog. Prime Video has announced its upcoming Spanish original series “Romancero,” a fast-paced horror story with supernatural overtones written by the horror author and screenwriter Fernando Navarro (Venus, Verónica) and directed by Manson collective member Tomás Peña, in which It will be his first foray into a fiction production, after directing video clips for artists such as Rosalía, C. Tangana, Katy Perry, Raw Alejandro, Bad Gyal or The Prodigy.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Well, I find it very interesting that Romancero Gitano is a source of inspiration for a series, another work of Lorca was adapted some years ago into a film, La Novia (based on the play Bodas de Sangre).

The book is composed of 18 poems: Romance de la luna, luna, Preciosa y el aire, Reyerta, Romance sonámbulo, La monja gitana, La casada infiel, Romance de la pena negra, San Miguel, San Rafael, San Gabriel, Prendimiento de Antoñito el Camborio en el camino de Sevilla, Muerte de Antoñito el Camborio, Muerto de amor, Romance del emplazado, Romance de la Guardia Civil española, Martirio de Santa Olalla, Burla de don Pedro a caballo and Thamar y Amnón.

So, maybe the stories of the characters are inspired on the poems.

It was published in 1928, so maybe the series will be set on the 1920's, although it hasn't been told any concrete period, I don't know if they will through a modern day setting.

Romancero Gitano isn't a horror book but maybe some elements of the poems like metaphors or symbolisms could be taken for some kind of magical elements (and some of the metaphors are a bit strange due to surrealism influences, although surrealism is more a thing from Poeta en Nueva York, writen between the years 1929-30, published in 1940 in Mexico). The other inspiración for the series is Gothic literature, so that would be the source of supernatural elements.

Like, the Romancero book mainly are stories (some of them tragical) about Andalusian Romani people and their culture, and also deals with the marginalization and oppresion suffered by the Romanis because of the Civil Guard (the Spanish Gendarmerie).

Taking a look at the cast for Romancero, Alba Flores is Romani. She's from the Flores family, a famous Andalusian Romani family of artists, in fact Alba's grandmother was the flamenco dancer and singer Lola Flores.

An interesting aspect from Romancero Gitano is that Lorca mixed elements from the literary movements from the early 20th century and the style of poetry from the past, like the "Romancero viejo", that is a collection of anonymous poems from oral tradition from the Iberian Peninsula from the Middle Ages that were later published in books between the 15-16th centuries. Then there's the "Romancero nuevo", that is the total of the writen poetry of known authors since the 16th century (although it's common to focus on the poetry from the 16-17th centuries mainly).

Talking about symbolism, these are the main symbols used by Lorca in Romancero Gitano (although some of them are very common in other of his works):

• Metals (knives, anvils, rings...): the life of Romani people and death.

• Air or wind: tragedy, male eroticism aggressive and violent.

• Mirror: home and sedentary life.

• Water: (in motion) life, (at rest) stagnant passion or death.

• Well: stagnant passion or death

• Horse: unbridled passion that leads to death. It could also mean virility, wild passion or freedom.

• Moon: It is the most used by Lorca, it appears 218 times. Its symbolism depends on how it appears. If it is red it means painful death; black, simply death; big means hope; pointy, has an erotic connotation. I could also mean femininity or sensuality.

• Rooster: sacrifice and destruction of the Romani

• The Civil Guard: they represent authority, therefore symbols of destruction and death over the Romani

• Alcohol: negativity.

• Milk: the natural.

• Wicker rod: lordship, nobility, dignity and elegance of the Romani

•Color green: death. It could also represent love frustration, forbidden desire and male sexual instinct

• Color black: death.

• Color white: life, light.

• Roses: blood

• Rider: omen of death

• Fish: associated with sexuality and dawn

• Blood: sexual instinct and omen of death

I wonder if this symbols will be shown in some kind of way.

For example the symbol of the green color meaning death can be noted in the poem Romance sonámbulo, like in this case the green that is constantly used for descriving the woman or her environment means that is going to die/is dying, and she couldn't meet her lover again. Then there's other symbols like the moon that means death too and the aljibe (a water cistern) is water at rest, so it could also mean death. It could be that the woman got drown in the aljibe, and maybe the civil guards are involved or responsible for her death.

And also metals could be a death symbol, and the eyes of the woman are described as "cold silver", maybe a way of saying that her eyes are grey.

Verde que te quiero verde.

Verde viento. Verdes ramas.

El barco sobre la mar

y el caballo en la montaña.

Con la sombra en la cintura

ella sueña en su baranda,

verde carne, pelo verde,

con ojos de fría plata.

Verde que te quiero verde.

Bajo la luna gitana,

las cosas le están mirando

y ella no puede mirarlas.

*

Verde que te quiero verde.

Grandes estrellas de escarcha,

vienen con el pez de sombra

que abre el camino del alba.

La higuera frota su viento

con la lija de sus ramas,

y el monte, gato garduño,

eriza sus pitas agrias.

¿Pero quién vendrá? ¿Y por dónde...?

Ella sigue en su baranda,

verde carne, pelo verde,

soñando en la mar amarga.

*

- Compadre, quiero cambiar

mi caballo por su casa,

mi montura por su espejo,

mi cuchillo por su manta.

Compadre, vengo sangrando,

desde los montes de Cabra.

- Si yo pudiera, mocito,

ese trato se cerraba.

Pero yo ya no soy yo,

ni mi casa es ya mi casa.

- Compadre, quiero morir

decentemente en mi cama.

De acero, si puede ser,

con las sábanas de holanda.

¿No ves la herida que tengo

desde el pecho a la garganta?

- Trescientas rosas morenas

lleva tu pechera blanca.

Tu sangre rezuma y huele

alrededor de tu faja.

Pero yo ya no soy yo,

ni mi casa es ya mi casa.

- Dejadme subir al menos

hasta las altas barandas,

dejadme subir, dejadme,

hasta las verdes barandas.

Barandales de la luna

por donde retumba el agua.

*

Ya suben los dos compadres

hacia las altas barandas.

Dejando un rastro de sangre.

Dejando un rastro de lágrimas.

Temblaban en los tejados

farolillos de hojalata.

Mil panderos de cristal,

herían la madrugada.

*

Verde que te quiero verde,

verde viento, verdes ramas.

Los dos compadres subieron.

El largo viento, dejaba

en la boca un raro gusto

de hiel, de menta y de albahaca.

- ¡Compadre! ¿Dónde está, dime?

¿Dónde está mi niña amarga?

- ¡Cuántas veces te esperó!

¡Cuántas veces te esperara,

cara fresca, negro pelo,

en esta verde baranda!

*

Sobre el rostro del aljibe

se mecía la gitana.

Verde carne, pelo verde,

con ojos de fría plata.

Un carámbano de luna

la sostiene sobre el agua.

La noche se puso íntima

como una pequeña plaza.

Guardias civiles borrachos,

en la puerta golpeaban.

Verde que te quiero verde.

Verde viento. Verdes ramas.

El barco sobre la mar.

Y el caballo en la montaña.

Now I'm remembering about symbolisms of Lorca's works that could be hinted in other fictions, although it's more like a theory/headcanon from a certain part of the Emdt fandom here on Tumblr, is that in El Ministerio del tiempo, Julián is the origin of the symbolism green=death. In this post there's the one in which the idea was pointed, although it points something more general, not concretely being a symbol for death, because depending on the work or the context, green can be also a symbol for life, rebeldy and desire for freedom. It might seem a little weird, but I will develop later.

Lorca's character makes his debut in the season 1 finale 1×08, La leyenda del tiempo, set on 1924 (Lorca was 26 years old in 1924, although Ángel Ruiz, the actor who plays Lorca is much older) that clearly shows references or takes themes from some of his works, like the poem Fábula y rueda de los tres amigos from Poeta en Nueva York and the poem La Leyenda del tiempo (the title of the episode comes from this poem) from the play Así que pasen cinco años , but indirectly could be a little from Romancero Gitano.

Like, firstly in the episode it's shown a special connection between Julián and Lorca through dreams, and their shared dreams of the episode depict Maite's death.

Something like the eye colors of an actor may seem something trivial, but yeah, Rodolfo Sancho's eyes are green, although sometimes it can't be appreciated well, although for example there's a close up to Julián's eyes at the end of episode 1×07 Tiempo de Venganza , and Mar Ulldemolins' eyes, the actress who plays as Maite, are also green.

Just by the end of the episode Julián tries to save Maite but he fails, and it resembles a bit the situation of the poem where the traveler is going to meet his lover, but she died and he couldn't do anything to save her. But at the end in the season 4 finale he finally saved her.

Next there's the issue of Lorca's death, and Julián is worried about and wanted to warn Lorca about his death but he didn't do it, so in season 4 he did it, although Lorca accepted his fate.

This is kind of a joke but in the first seasons Julián is the Margaery Tyrell of Emdt, like the ones who get married with them probably will die soon, in one case Renly and Joffrey (+Tommen in GOT) and then Maite and Amelia.

Between Amelia and Julián there was the thing about the fake engagement that started on episode 1×04 so Amelia's mother doesn't annoy her with trying to push her into an arranged marriage, and then what it's known from Amelia's tomb and the photos, the wedding, their daughter and Amelia's death, and in episode 8 they met their grandaughter Silvia (played by Iria del Río, who has participated in some period dramas like La catedral del mar and Las chicas del cable). Although after what happened in the following seasons, that future will never happen.

I was thinking about the Emdt showrunners Javier and Pablo Olivares. Pablo had Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and the first season of Emdt was his last work (in the last previous years the Olivares brothers worked on period dramas like Isabel or Víctor Ros) and there could be some personal aspects reflected on ths series in some character plots, for example following this theme, there's no cure for ALS and there's the struggle of both brothers towards Pablo's death, from Pablo's perspective, knowing that he's going to die soon, like Amelia visiting her own tomb in the first seasons, knowing she's going to die in 5-4 years, although she didn't knew about the cause of her death (that's a thing for fan theories); Pablo and Javier facing Pablo's future death, reflected in Julián and Lorca, Julián told Lorca that he'll die and Lorca accepts it and Julián deals with it; iI would say that this also could be seen in the Amelia &Julián part, although maybe Julián isn't as much emotionaly involved into it but he cares about Amelia (Julián is more focused on Maite and maybe the thing about knowing that he will allegedly marry, have a daughter and lose someone again it'a a bit hard to process);and there's the last part of Javier mourning his brother, that could be represented in Julián's mouring over Maite's death.

#romancero#upcoming series#sasha cócola#elena matic#belén cuesta#alba flores#julieta cardinali#ricardo gómez#guillermo toledo#long post#fernando navarro

7 notes

·

View notes