#Aliza Nisenbaum

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

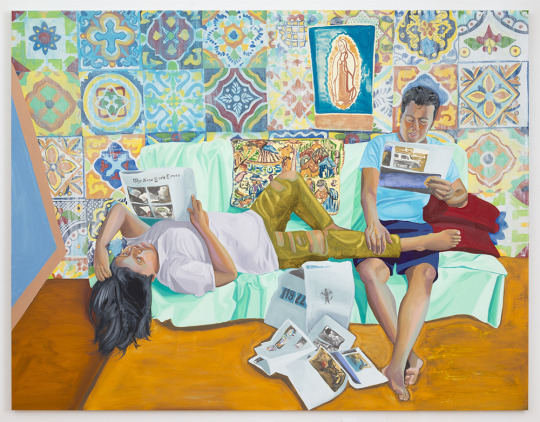

Aliza Nisenbaum (Mexican, 1977), Mis Cuatro Gracias (Brendan, Camilo, Carlos, Jorge) [My Four Graces (Brendan, Camilo, Carlos, Jorge)], 2018. Oil on linen, 75 x 95 in.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aliza Nisenbaum Inside Turn, Lead and Follow 2024

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aliza Nisenbaum (Mexican b. 1977, lives and works in New York City), Neena dreams of DJing, 2021. Oil on canvas, 63 x 57 in. | 162.6 x 144.8 cm.

#art#artwork#modern art#contemporary art#modern artwork#contemporary artwork#21st century art#21st century modern art#21st century contemporary art#American art#modern American art#contemporary American art#female American artist#female artist#female painter#woman artist#woman painter#Aliza Nisenbaum#DJing#dreams#popular culture#popular culture in art

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

elsewhere on the internet: jewish currents

Jewish Currents has consistently published articles that I think about for days afterwards. Here are a few pieces from recent issues.

Can Tourist Be Liberatory

Raphael Magarik: People often think of tourism as shallow, consumerist, and apolitical. How is solidarity tourism different? Jennifer Lynn Kelly: In solidarity tourism, guides educate tourists about their context, their conditions, and their freedom struggles. In each of the tours considered in my book—which range from the week-long tours across historic Palestine, to day tours of cities or villages in the West Bank, to two-hour tours in the eastern part of occupied Jerusalem or in West Jerusalem—guides focus on the history of Palestinian displacement and provide an alternative to Zionist narratives. For example, on bus tours through the West Bank, guides will point to sprawling Palestinian terraces and explain how Palestinians have always cared for the land. In doing so, they are intervening in the Zionist idea that Palestine was “a land without a people for a people without a land.” By assembling these kinds of itineraries, the guides are pressing tourism into the service of anti-colonial work.

JLK: Tourism often aspires toward authenticity: unfettered access to an unscripted world. That is a consumerist desire. Solidarity tourism is not exempt from this tendency, but it reveals and subverts the script of tourists’ expectations. For instance, in the book I talk about a moment where a tourist was looking at a blackened wall in Nablus and asked, “What happened here?” And the tour guide said, “Someone was spray painting their bed frame.” In these moments, tour guides are interrupting tourists’ desire for a narration of violence and only violence.

RM: The Israeli siege of Gaza essentially renders in-person tourism impossible. How do guides respond to this problem? JLK: In Gaza, some guides might walk tourists virtually through their space and answer questions about their conditions. Others use recorded snippets to create a hypothetical tour where they say, “If you were to take a walking tour in Gaza City, here is where I would take you.” There are also virtual tours that help visitors imagine a vibrant, thriving tourism industry in Gaza after liberation. Like solidarity tourism, these virtual experiences are a true refiguring of tourism. The result is not just a camera leading tourists through a space but an exercise in imagining liberation.

Portraits of Encounter

Aliza Nisenbaum’s exhibition at the Queens Museum is bookended by a pair of paintings that create an echo. At one end hangs La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times (2016), in which a teenage girl and her father read the paper on a couch.

...

“The best portrait painters working today introduce something new into art not through stylistic innovations, but by whom they choose as subjects,” Dushko Petrovich wrote in an article that discusses Nisenbaum’s work published in T Magazine in 2018. Certainly, there’s gratification in seeing marginalized people get the kind of sumptuous treatment they receive in Nisenbaum’s paintings. But reading Nisenbaum primarily through the lens of representation elides important aspects of her practice—for example, she paints dancers and flowers, and she gets as animated about color as she does about her subjects.

Portraiture gives Nisenbaum a framework in which to encounter other people. In this she’s like the artist Alice Neel, who famously canonized friends, neighbors, and art-world figures in portraits so penetrating, they can be uncomfortable to look at. Neel called herself a “collector of souls”; Nisenbaum, by contrast, seems less interested in baring people’s true selves on canvas than in capturing something of their profound unknowability. Her subjects are often lost in thought or activity, like Marissa in La Talaverita and Pedacito de Sol. Others are immersed in settings filled with material culture—like Andra, a facilities staffer at the Queens Museum whom Nisenbaum depicts in his office,

She also developed a policy of compensating sitters. Before she was selling her work, she would cook for them and give them their finished paintings. (These small gestures of care sometimes yielded significant results; during the Covid-19 pandemic, when they were struggling with unemployment, Marissa and her mother were able to sell two early Nisenbaum pieces to Anton Kern Gallery, which represents the artist.) Now that there is a market for her work, Nisenbaum pays her subjects, and donates to organizations that are somehow aligned with the people she’s depicting in a given project. In the case of the current exhibition, that’s the La Jornada and Queens Museum Cultural Food Pantry, which takes place at the museum every Wednesday.

Such practices build on Levinas’s idea of an ethics grounded in the face-to-face encounter. In the process, they help Nisenbaum mitigate the exploitation that has been a hallmark of art history, especially when the people being portrayed come from groups on the margins of society. But beyond payment, Nisenbaum is interested in mutual relationships as both a standard and a subject. For example, the exhibition includes a large painting of the pantry titled Eloina, Angie, Abril y Marleny, Despensa de Alimentos, Queens Museum (2023). It’s a vertiginous scene of flattened perspective in which produce, volunteers, and “shoppers” form a sweeping, colorful loop of activity.

Bad Memory

an editorial column written by members of the Jewish Currents staff and reflects a collective discussion.

Germany is acclaimed for its efforts to atone for the Holocaust. But its method of repudiating the past has become a tool of exclusion.

..

To show itself fit to enter the community of Western European nations, a new, reunified Germany set out to prove, over the next two decades, that it had sufficiently repented. Germans even coined a new word—Vergangenheitsbewältigung—to name the process of “coming to terms with the past” that has become a linchpin of German national identity. Seeking to bolster its claim to penitence, the newly reunified country trumpeted a “Jewish renaissance” driven largely by immigration from the former Soviet Union—an influx of Jews that, as the scholar Hannah Tzuberi has put it, became the “most valuable guarantor of [Germany’s] democratic, liberal, tolerant character.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Neena dreams of DJing" by Aliza Nisenbaum (2021), oil on canvas

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aliza Nisenbaum - Tumbao de Omambo. 2020

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aliza Nisenbaum’s paintings for Altanera, Preciosa y Orgullosa, her current exhibition at Regen Projects, fill the gallery with colorful portraits depicting dancers from dance troupes and studios local to Southern California- including Teresita de Jesús of Studio 10, Folklorico Revolución, Mariachi Tierra Mia, and Amelia Muñoz Dancers.

From the press release-

An early, leading figure in the centrality of representation and portraiture in the preceding decade, Nisenbaum develops vibrant, figurative paintings through a form of participatory observation. She forges relationships with her subjects and connects meaningfully to the complex communities they create together. Informed by a diverse array of artistic and political traditions, Nisenbaum’s pictures (and the process through which they are made) recall forebears such as Alice Neel, Sylvia Sleigh, and Diego Rivera.

From mariachi to salsa, the works give painterly shape to the fleeting festivity of these traditions. Exploring connections between sight and sound, they evoke music and movement in an otherwise static, silent medium by way of color, contour, and pattern. As such, they recall modernist experiments and visionaries such as Sonia Delaunay and Florine Stettheimer. Mindful of the ever-intensifying specter of technology that shapes our daily lives and recalling sociologist Émile Durkheim’s theory of “collective effervescence,” Nisenbaum’s paintings celebrate these spaces and occasions for dancing as consecrated moments apart from our screens and devices, reminding us of the pleasure of being more fully of and with our bodies and each other.

The exhibition’s title, Altanera, Preciosa y Orgullosa, draws from “La Bikina,” an iconic Mexican ballad, and describes the song’s namesake subject, a “haughty, gorgeous and proud” woman. As such, it alludes to the sounds and sentiments that might accompany the dancers and musicians pictured throughout Nisenbaum’s paintings, as well as her overarching interest in depictions of female power, independence, and self-assuredness. These themes recur in La Bruja, a painting of dancers learning to carry lit candles safely atop their heads as they dance to lyrics that describe a witch, or “bruja,” at work in the middle of the night. For Nisenbaum, La Bruja, like “La Bikina,” evokes a powerful mythology of strong women, informed by their own agency and control as they move through the world.

Poised and focused, Shine Arm Styling, on 1, introduces us to a duo especially attentive to the most decisive details. Likewise, Nisenbaum’s paintings orchestrate a carefully calibrated concert of humming patterns and colors, from the rhyming latticework of tights to the gauzy curtains that drape and cocoon the rooms, the lacey fretwork of leotards and costumes, and the pronounced grain of the wooden floors. Animating and unbridled patterning recurs across the canvases, a painterly translation of the energy of the dancers and the spirit of their music. Just as the women tap more and more frenetically in La Bruja—building and accelerating—the pattern that frames them expands through and beyond the figures, likening the sonic experience to this visual effect, as well as the pace of paint handling that produces it.

Similarly, as dancers slide and screech to a halt, the undulating motion of the wooden floors mirrors the movement of the figures via painterly gesture. Rehearsal mirrors and elevated bars occasion playful angles, geometries, and juxtapositions, expanding and suturing spaces and passages. They punctuate, frame, divide, and at times provocatively double or even triple figures and forms, creating and implying pictures within pictures. Such reflections liken Nisenbaum’s activity as a painter to that of the whirling dancers. Her complex tableaux reveal her deep awareness and clear delight in the possibilities of painting to narrate human experience and the relationships that sustain us.

This exhibition closes 10/26/24.

#Aliza Nisenbaum#Regen Projects#Amelia Muñoz Dancers#Art#Art Shows#Dance Studio#Dancers#Folklorico Revolución#Los Angeles Art Show#Los Angeles Art Shows#Mariachi Tierra Mia#Painting#Teresita de Jesús of Studio 10

0 notes

Text

Pedacito de Sol (Vero y Marissa), 2022, oil on canvas, 75 × 95 inches.

Aliza Nisenbaum

Paintings of the individual and the community.

Photos by Thomas Barratt.

Eloina, Angie, Emma, Abril y Marleny, Despensa de Alimentos, Queens Museum, 2023, oil on canvas, two panels: 95 × 75 inches each.

El Taller, Queens Museum, 2023, oil on canvas, two panels: 95 × 75 inches each.

0 notes

Text

Portrait of Aliza Nisenbaum (b. 1977, Mexico City). Photo credit to Brad Ogbonna/ Courtesy of Vogue.

Aliza Nisenbaum, "Tumbao de Omambo" (2020). Oil on canvas. Courtesy the artist and Anton Kern Gallery.

source & more HERE

0 notes

Text

Susan, Aarti, Keerthana and Princess, Sunday in Brooklyn 2018 by Aliza Nisenbaum

#art#painting#Susan Aarti Keerthana and Princess Sunday in Brooklyn 2018#The Tate Museum#Aliza Nisenbaum

1 note

·

View note

Text

Aliza Nisenbaum (Mexican, 1977), Dálida and Michael (Serenata del Tres Cubano) from Aquí Se Puede (Here You Can), 2021. Oil on canvas, 64 x 57 in.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aliza Nisenbaum, Yessi (2014)

1 note

·

View note

Text

ISBN: 978-618-87242-1-1 Συγγραφέας: Gozansky Shana Εκδότης: ΙΝΩ Σελίδες: 48 Ημερομηνία Έκδοσης: 2024-08-26 Διαστάσεις: 19.5 x 15.5 Εξώφυλλο: Σκληρόδετο

0 notes