#ARABIC NOUN CASES

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

ARABIC NOUN CASES: A BEGINNER’S GUIDE

Learning Arabic can be both fascinating and challenging, especially when it comes to understanding noun cases. Arabic noun cases are essential for correct sentence structure and meaning. In this guide, we’ll break down the basics of Arabic noun cases in a way that’s easy to grasp and apply.

Introduction

Have you ever wondered why certain words in Arabic change their endings depending on their role in a sentence? This is due to noun cases. Mastering Arabic noun cases is like understanding the grammar puzzle that holds the language together. Let’s dive in and decode this essential aspect of Arabic grammar.

What Are Arabic Noun Cases?

In Arabic, noun cases indicate the grammatical function of a noun in a sentence. This is similar to how pronouns change in English, like “I” becoming “me” or “my.” Arabic uses specific endings to show whether a noun is the subject, the object, or shows possession.

The Three Main Noun Cases

There are three primary noun cases in Arabic:

Nominative (المرفوع): Used for subjects of sentences.

Accusative (المنصوب): Used for objects of sentences.

Genitive (المجرور): Used to show possession or after prepositions.

Each case has specific endings that change based on the noun’s role in the sentence.

Nominative Case (المرفوع)

The nominative case is used for the subject of the sentence, the noun that is doing the action. For example:

الولدُ يلعب (al-walad-u yal’ab) – The boy is playing.

Here, الولدُ (al-walad-u, “the boy”) is in the nominative case, marked by the “ُ” (dammah) ending.

Accusative Case (المنصوب)

The accusative case is used for the direct object of the sentence, the noun receiving the action. For example:

رأيتُ الولدَ (ra’aytu al-walad-a) – I saw the boy.

Here, الولدَ (al-walad-a, “the boy”) is in the accusative case, marked by the “َ” (fathah) ending.

Genitive Case (المجرور)

The genitive case shows possession or follows a preposition. For example:

كتابُ الولدِ (kitābu al-walad-i) – The boy’s book.

Here, الولدِ (al-walad-i, “the boy”) is in the genitive case, marked by the “ِ” (kasrah) ending. It is also used after prepositions:

في البيتِ (fī al-bayt-i) – In the house.

Noun Case Endings

Understanding the endings for each case is crucial:

Nominative: “ُ” (dammah) for singular, “ُونَ” (ūna) for masculine plural, “َاتٌ” (ātun) for feminine plural.

Accusative: “َ” (fathah) for singular, “ِينَ” (īna) for masculine plural, “َاتٍ” (ātin) for feminine plural.

Genitive: “ِ” (kasrah) for singular, “ِينَ” (īna) for masculine plural, “َاتٍ” (ātin) for feminine plural.

Using Noun Cases in Sentences

Let’s look at some examples:

Nominative: الطالبُ يدرس (al-ṭālib-u yadrus) – The student is studying.

Accusative: أكلتُ التفاحةَ (akaltu al-tuffāḥah) – I ate the apple.

Genitive: قلمُ الطالبِ (qalam-u al-ṭālib-i) – The student’s pen.

Understanding these cases helps in constructing accurate and meaningful sentences.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Learning Arabic noun cases can be tricky, and beginners often make these mistakes:

Incorrect Endings: Mixing up the endings for each case.

Ignoring Prepositions: Not applying the genitive case after prepositions.

Overlooking Context: Forgetting that context can change the required case.

Tips for Mastering Noun Cases

Practice Regularly: Regular practice helps solidify understanding.

Use Flashcards: Create flashcards for each case ending and practice frequently.

Engage in Conversations: Practicing with native speakers can reinforce correct usage.

Read Arabic Texts: Reading helps you see noun cases in context, enhancing your learning.

Conclusion

Arabic noun cases might seem complex at first, but with regular practice and exposure, you’ll find them to be a logical and essential part of mastering the language. Remember, each case serves a specific purpose and helps in conveying precise meanings. Keep practicing, and soon you’ll find using noun cases to be second nature.

FAQs

What are the main noun cases in Arabic?The three main noun cases in Arabic are nominative (subject), accusative (object), and genitive (possession or after prepositions).

How can I remember the different noun case endings?Using flashcards and practicing with real sentences can help reinforce the different endings for each case.

Why are noun cases important in Arabic?Noun cases are crucial for proper sentence structure and meaning, indicating the grammatical function of nouns in sentences.

Can noun cases change the meaning of a sentence?Yes, incorrect use of noun cases can alter the meaning of a sentence or make it grammatically incorrect.

Are there exceptions to the noun case rules?While the rules for noun cases are generally consistent, some irregular nouns and specific contexts might present exceptions.

Understanding and applying Arabic noun cases correctly will significantly enhance your ability to read, write, and speak Arabic with accuracy and confidence. Happy learning!

About Author: Mr.Mahmoud Reda

Meet Mahmoud Reda, a seasoned Arabic language tutor with a wealth of experience spanning over a decade. Specializing in teaching Arabic and Quran to non-native speakers, Mahmoud has earned a reputation for his exceptional expertise and dedication to his students' success.

Mahmoud's educational journey led him to graduate from the renowned "Arabic Language" College at Al-Azhar University in Cairo. Holding the esteemed title of Hafiz and possessing Igaza, Mahmoud's qualifications underscore his deep understanding and mastery of the Arabic language.

Born and raised in Egypt, Mahmoud's cultural background infuses his teaching approach with authenticity and passion. His lifelong love for Arabic makes him a natural educator, effortlessly connecting with learners from diverse backgrounds.

What sets Mahmoud apart is his native proficiency in Egyptian Arabic, ensuring clear and concise language instruction. With over 10 years of teaching experience, Mahmoud customizes lessons to cater to individual learning styles, making the journey to fluency both engaging and effective.

Ready to embark on your Arabic learning journey? Connect with Mahmoud Reda at [email protected] for online Arabic and Quran lessons. Start your exploration of the language today and unlock a world of opportunities with Mahmoud as your trusted guide.

In conclusion, Mahmoud Reda's expertise and passion make him the ideal mentor for anyone seeking to master Arabic. With his guidance, language learning becomes an enriching experience, empowering students to communicate with confidence and fluency. Don't miss the chance to learn from Mahmoud Reda and discover the beauty of the Arabic language.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

ling reading

(from one of the articles that went into my #litreview)

At the morphological levels, it is well known that SA [Standard Arabic] has richer agreement paradigms that include dual forms and feminine plurals in the second and third persons. On the other hand, CA [Colloquial Arabic] tend to have richer aspectual and temporal systems with independent morphological markers and proclitics. Another major difference includes the presence of a robust morphological case system in SA that marks nouns as nominative, accusative, and genitive, while this system is totally absent in CA.

from “Arabic Diglossia and Heritage Arabic Speakers” by Abdulkaf Albirini and Elabbas Benmamoun, published in Handbook of Literacy in Diglossia and in Dialectal Contexts

This fucking rules btw. Fuck noun cases all my homies hate noun cases and LOVE richer aspectual and temporal systems 🥰

#wugs and co#noun case lovers are always the people who didn;t have to learn them through elementary school arabic classes

1 note

·

View note

Note

do you have any sources on the worship of the goddess inanna/Ishtar during the Seleucid/Hellenistic period to the Parthian period? i dont recall stumbling upon anything talking about her.

even though from what I've been reading mesopotamian deities were still popular (like bel-marduk in Palmyra and nabu in Edessa or shamash in hatra and mardin or sin in harran etc etc.. ) i dont recall reading anything about her or anything mention her worship (other than theories of the alabaster reclining figurines being depictions of her)

A good start when it comes to late developments in Mesopotamian religion is Religious Continuity and Change in Parthian Mesopotamia. A Note on the survival of Babylonian Traditions by Lucinda Dirven.

Hellenistic Uruk, and by extension the cult of Ishtar, is incredibly well documented and the most extensive monograph on this topic, Julia Krul’s The Revival of the Anu Cult and the Nocturnal Fire Ceremony at Late Babylonian Uruk, is pretty much open access (and I link it regularly here, and it's one of my to-go wiki editing points of reference as well); it has an extensive bibliography and the author discusses the history of research of the development of specific cults in Uruk in detail. The gist of it is fairly straightforward: her status declined because with the fall of Babylon to the Persians the priestly elites of Uruk decided it’s time for a reform and for the first time in history Anu’s primacy moved past the nominal level, into the cultic sphere, at the expense of Ishtar and Nanaya. Even the Eanna declined, though a new temple, the Irigal, was built essentially as a replacement; we know relatively a lot about its day to day operations. An akitu festival of Ishtar is also well documented, and Krul goes into its details. All around, I don’t think the linked book will disappoint you.

An important earlier work about the changes in Uruk in Paul-Alain Beaulieu’s Antiquarian Theology in Seleucid Uruk. There’s also Of Priests and Kings: The Babylonian New Year Festival in the Last Age of Cuneiform Culture by Céline Debourse which covers Uruk and Babylon, but there is less material relevant to this ask there. Evidence from Upper Mesopotamia and beyond is more fragmented so I’ll discuss it in more detail under the cut. My criticism of this take on the reclining figures is there as well.

The matter is briefly discussed in Personal Names in the Aramaic Inscriptions of Hatra by Enrico Marcato (p. 168; search for “Iššar” within the file for theophoric name attestations). References to a deity named ʻIššarbēl might indicate Ishtar of Arbela fared relatively well (for her earlier history see here and here) in the first centuries CE. The evidence is not unambiguous, though. This issue is discussed in detail in Lutz Greisiger’s Šarbēl: Göttin, Priester, Märtyrer – einige Probleme der spätantiken Religionsgeschichte Nordmesopotamiens. Theophoric names and the dubious case of ʻIššarbēl aside, there are basically no meaningful attestations of Ishtar from Hatra, but curiously “Ishtar of Hatra” does appear in a Mandaic scroll known as the “Great Mandaic Demon Roll”. According to Marcato this evidence should not be taken out of context, and additionally it cannot be ruled that we’re dealing with a case of ishtar as a generic noun for a goddess (An Aramaic Incantation Bowl and the Fall of Hatra, pages 139-140; accessible via De Gruyter). If this is correct, most likely Marten (the enigmatic main female deity of the local pantheon), Nanaya or Allat (brought to Upper Mesopotamia by Arabs settling there in the first centuries CE) are actually meant as opposed to Ishtar.

Joan Goodnick Westenholz suggested that Mandaic sources might also contain references to Ishtar of Babylon: the theonym Bablīta (“the Babylonian”) attested in them according to her might reflect the emergence of a new deity derived from Bēlet-Bābili (ie. Ishtar of Babylon) in late antiquity (Goddesses in Context, p. 133)

In addition to Marcato’s article listed above, another good starting point for looking into Mesopotamian religious “fossils” in Mandaic sources is Spätbabylonische Gottheiten in spätantiken mandäischen Texten by Christa Müller-Kessler and Karlheinz Kessler; Ishtar is covered on pages 72-73 and 83-84 though i’d recommend reading the full article for context. The topic is further explored here.

In his old-ish monograph The Pantheon of Palmyra, Javier Teixidor proposed that the sparsely attested local Palmyrene goddess Herta (I’ve also seen her name romanized as Ḥirta; it’s agreed that it’s derived from Akkadian ḫīrtu, “wife”) was a form of Ishtar, based on the fact she appears in multiple inscriptions alongside Nanaya (p. 111). She is best known from a dedication formula where she forms a triad with Nanaya and Resheph (Greek version replaces them with Hera and Artemis, but curiously keeps Resheph as himself). However, ultimately little can be said about her cult beyond the fact it existed, since a priest in her service is mentioned at least once.

I need to stress here that I didn’t find any other authors arguing in favor of the existence of a supposed Palmyrene Ishtar. Joan Goodnick Westenholz mentioned Herta in her seminal Nanaya: Lady of Mystery, but she only concluded that the name was an Akkadian loanword and that she, Resheph and Nanaya indeed formed a triad (p. 79; published in Sumerian Gods and their Representations, which as far as I know can only be accessed through certain totally legit means). Maciej M. Münnich in his monograph The God Resheph in the Ancient Near East doesn’t seem to be convinced by Teixidor’s arguments, and notes that it’s most sensible to assume Herta seems to be Nanaya’s mother in local tradition. He similarly criticizes Teixidor for asserting Resheph has to be identical with Nergal in Palmyrene context (pages 259-260); I’m inclined to agree with his reasoning, interchangeability of deities cannot be presumed without strong evidence and that is lacking here.

I’m not aware of any attestations from Dura Europos. Nanaya had that market cornered on her own. Last but not least: I'm pretty sure the number of authors identifying the statuettes you’ve mentioned this way is in the low single digits. The similar standing one from the Louvre is conventionally identified as Nanaya (see ex. Westenholz's Trading the Symbols of the Goddess Nanaya), who has a much stronger claim to crescent as an attribute (compare later Kushan and Sogdian depictions, plus note the official Seleucid interpretatio as Artemis for dynastic politics purposes), so I see little reason to doubt reclining figures so similar they even tend to have the same sort of gem navel decoration are also her, personally.

A great example of the Nanaya-ish statuette from the Louvre (wikimedia commons). To sum everything up: while evidence is available from both the south and the north, the last centuries BCE and first centuries CE were generally a time of decline for Ishtar(s); for the first time Nanaya was a clear winner instead, but that's another story...

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

I had a question about how h is pronounced in Spanish- I know in a lot of words, it's technically silent, like el alcohol- "alkohl" , or huesped sounding more like "weh-sped". But what about words like el azahar? Do the h's in the middle of a word typically get pronounced, or is it more like there are special cases? or is just "azaar"?

The only times the H gets specifically pronounced is when you're talking about loanwords - words directly taken from other languages, which are often proper nouns, names, etc that come very directly from other languages

But otherwise, no the H is silent - though I have noticed people do seem to do a special vocal emphasis just to make it clear there's an extra syllable sometimes. As in, if I hear someone say "Alhambra", to me it sounds like Al-Aambra" rather than skipping the sound completely, but that could just be how I hear it

Whether you're saying el azahar as sort of like "azar" or "azaar" both make sense

It's mostly just important for spelling to know that you'll be saying something like agua de azahar and not "agua de azar"

I would recommend checking out Forvo which is a pronunciation site where people from all over pronounce certain words and you can hear the accents

[Side Note: el azar is another word for "luck" in Spanish but it's directly related to el azahar "orange blossom" in Spanish - in Arabic the original word meant "flower", but in Al-Andalus (modern Andalusia in the south of Spain which was occupied by Muslims for 700 years) the word came out as azzar or azahar for talking about the white flowers of "orange blossoms"...... in games of dice, one of the sides was labeled "flower" so saying al azar meaning "randomly" was something like "by the throwing of the dice" - one of the things where game terminology affects language]

#langblr#spanish#learning spanish#learn spanish#english language#asks#spanish vocabulary#vocabulario

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding how contemporary Israeli coloniality mobilizes environmental space requires us to begin from the function of the border—and the ways in which the border is mobilized by the interlocking political systems of settler-colonialism, apartheid, and occupation in Israel/Palestine.

In the case of Israel, its major features of nation-statehood, including final territorial borders, notion of "peoplehood," and sovereign rule largely remain incomplete. As a result, its ability to create the categories of insider/outsider and citizen/foreigner become particularly interesting when one notes that Israel is the only internationally recognized state in the world without de facto final borders. Continued occupation, annexation, expropriation, expansion, displacement, forced transfer, practices of apartheid, and besiegement of the Palestinian population and their lands places Israel's borders, in practice, in continuous flux. Working from the relationship of rejection and non-identification of the Palestinian other by the state, the border within the Israeli "incorporation regime" has only one side. When it comes to its division from Palestinian communities—whether citizens, residents or refugees—the borders of the state are one-directional. Sfard continues that:

"This one-way barrier functions like a one-way mirror. Both deflect (people or light) from only one side. In the case of the separation fence, it is the Palestinian side that gets deflected. For Palestinians, the fence is both a physical barrier and a borderline. For Israelis the fence is neither. The fact that the barrier has only one side gives Israel an inside, without having to recognize that the area on the other side of the fence is an outside. While a border establishes distinct sovereignties on either side of it, this one-way fence with sovereignty only on one side creates moving lines of sovereignty. The border is a process, a verb rather than a noun."

Evidently, Sfard is discussing Israel's Wall in Jerusalem and the West Bank. However, when examining exclusion in the context of an incorporation regime that spans contemporary Israel/Palestine as a single geographical unit, his conclusions regarding the barrier can here be broadened to describe the logic of exclusion to which all non-Jewish Palestinian political subjects are faced. Put differently, in the case of contemporary Israel/Palestine, understanding that "the border is a verb" means that we are examining something that is multifaceted and multi-layered. The borders of the Jewish State are not at the periphery or margins of the territorial state itself: Israel's borders are not at the border. Rather, its borders, including the inherent logic of exclusion and otherness that this political-legal concept produces, are constantly moving, and with various violent intensities bleed across the categories of citizen, immigrant, resident, and refugee.

Palestinian-Arab presence within this incorporation regime is situated within a continuous logic of exclusion specific to their civic status, effectively making their bodies into borders. They are included in the Israeli incorporation regime, yet they are perpetually consigned to its peripheries. Together, the racially hierarchical framework of the Israeli state apparatus and its juridicopolitical order determines that the borders of the state, its ideological and conceptual contours and the limits and ends of its representation and protection, all acquire their shape and meaning from the non-Jewish other.

Shourideh C. Molavi, Environmental Warfare in Gaza: Colonial Violence and New Landscapes of Resistance

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

also it took me learning that the arabic word for "to understand" is فهم to find out that فهمیدن is a naturalized loan from arabic which was really surpising to me! Most persian verbs that are arabic in origin take the form of "arabic noun + کردن" but in this case the base form of the original arabic verb was loaned wholesale (rather than taking the verbal noun form as in فکر کردن) and used as the root for the verb

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dose # 14 - two types of lām

Categories of words

Before we start, we need to talk about the three types of words in Arabic : noun, verb and ḥarf.

A verb فعل [fi'l] is a word with a meaning that indicates a tense.

A noun اسم [ism] is a word with a meaning that does not indicate a tense and is not linked with time.

The word “ḥarf” حرف [ḥarf] literally means “letter”, but in this context it can also refer to a "grammatical particle". In Arabic this is a part of speech that is neither a noun nor a verb, and plays a supporting role in a sentence, it needs other words to have a complete meaning. Some particles are composed of one letter and some are composed of several letters.

Indefinite vs definite nouns?

Before we start the lesson, I would like to introduce a small grammatical point related to the tanween which we have seen before.

The tanween in Arabic is the mark of the indefinite nouns.

This means two things : that is can only come at the end of the nouns (never at the end of a verb); AND that it means that this nouns is indefinite for example :

A pen = قَلَمٌ A book = كِتَابٌ A king = مَلِكٍ A prince = أَميرًا

Since Arabic has grammatical cases as we said in an earlier lesson, the choice between the 3 different tanweens is made depending on the role that the word plays in a sentence.

هَذَا قَلَمٌ أَحْمَرٌ [This is a red pen]

رَأيْتُ قَلَمًا [I saw a pen]

كُتِبَ بِقَلَمٍ أَحْمَرَ [It was written with a red pen]

This is true in case of the ḥarakat as well as the tanweens.

Types of "lām" and the definite article

“Al” in Arabic is the Arabic equivalent of “the”, and it’s the most common way to define a noun.

Note that “Al” will never accompany a verb or a preposition. There are other marks of a definite noun but we will discuss them in more advanced lessons.

In Arabic, “Al” is referred to as “aattʿrīf” أل التعريف [audio], and it only comes with a noun.

“Al” is composed of two letters, alif (ا) and lam (ل). There are two ways to pronounce the “lām” depending on the letter that follows it. These two ways to pronounce it are what I refer to as the types of “lām”.

This may seem like a strange concept but you will get more familiar with it when you hear more examples :

1- First “lām” type : lam qamariyya (the lunar “lām”) لام قمرية [audio]

When followed by the moon letters the “lām” in “al” أل التعريف is pronounced, and the letter that follows it is also pronounced. So basically, the word is read the way it is written.

Note : I might also refer to this "lām" as the "moon lām".

There are 14 moon letters and they are :

Examples

أَرْنَبٌ + أل التَّعْريف = الأَرْنَبُ

[audio]

جَمَلٌ + أل التَّعْرِيف = الجَمَلُ

[audio]

وَلَدٌ + أَل التَّعْرِيفِ = الوَلَدُ

[audio]

Notice how the words without أل التعريف all had tanween, but once we added the "al" the word automatically becomes definite. And we mentioned that the definite article cannot have tanween.

2- Second “lām” type : lam šamsiyya (the sun “lām”) لام شمسية [audio]

When followed by the sun letters, the “lām” is not pronounced, and the letter that follows it has shadda (stressed letter).

There are 14 sun letters, and they are :

Examples

دَرْبٌ + أل التَّعْرِيف = الدَّرْبُ

[audio]

طَائِرَةٌ + أَل التَّعْرِيف = الطَائِرَةُ

[audio]

سَمَكَةٌ + أَل التَّعْرِيفِ = السَّمَكَةُ

[audio]

To help you memorize

To help you memorize which letter is a sun letter and which letter is a moon letter, memorize the name of the letter, for example, instead of saying (أ) Alif, try saying حرف الألف (ḥarful alif) , the letter alif, and instead of saying “dal” for the letter د try saying حرف الدال (ḥarfu-ddāl) ie the letter dāl.

When you memorize each letter’s name with “al” you will automatically know if this letter is a moon or sun letter.

If you go back to the old lessons, you'll see that I color coded all the sun letters in green while the moon letters in blue.

Additionally, another interesting clue is the "emphatic letter" is similar to the letter that is the lighter version for example س -ص are both sun lettets, ذ - ظ are also sun letters.

Also the letters that look alike (sister letters as I call them) are also similar (except for the ب); for example ت - ث are sun letters, ص - ض are sun letters, ر-ز , ط-ظ are all sun letters.

ف- ق are moon letters. ح-ج-خ are also moon letters, ع-غ are moon letters.

How time flies! ヾ(^∇^)

With this we have reached the very last lesson of this course. I hope you found it helpful and interesting! And please excuse any imperfections, I spent alot of time trying to make it as good as I could. I also looked up information and asked professionals whenever I needed to verify any information. I really enjoyed working on it and I was so happy with your participation and encouragement!

Hope to have you again insha'Allah in future courses ♡(◕ᗜ◕✿)

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

omg hi! I was thinking about it after I saw post on radblr about gendered languages soo I want to ask you to make a poll if it's okay!

my native language is gendered so you can refer to chair as he and to door as she and everything, it is not only reflected in nouns but also in adjectives and verbs. and since everything is gendered, you can't talk about someone without specifying their sex, so for example, if you want to say "this teacher is very nice" you need to specify in every word that teacher's sex.

so the problem in my country that feminists are dealing with, is that people, when referring to a woman, are using he/him for noun and she/her for the rest of the words. like in "this doctor is very nice" "doctor" will be used in a male form, while all the other words will be used in a female form or if someone want to say "this doctor is a good specialist" they will only specify that this is a woman only in a word "this" or won't do even that.

this way of using words is already erasing women from the language, but with all that, one of the arguments against using female form while talking about a woman (which is grammarly correct and is what feminists are asking for) is that female form sound "unserious" or "unprofessional". it is also a common thing to hear something like "she's not an actress, she's an actor!" as if "actress"(female) is inferior and "actor"(male) is superior.

there are female forms of words that people do not care about(some still do), mostly because it is usually women's professions like "teacher", "kindergartener", "flight attendant", "babysitter", etc but it is only adding to all that misogyny.

so all this talking was because I wanted to ask you to make a poll about if other women speaking gendered language have this kind of problem in their country/language.

I also always feel weird when people in english are using gay as an adjective, like saying gay woman instead of lesbian and gay people while referring to LGB but not lesbian people or bi people for some reason. but it seems like a lot of woman here on radblr don't really mind that? so I thought that it might be because of how english is not gendered and if there's any gyns speaking gendered languages, I would also like to read what they think about it.

my language is similarly gendered! coincidentally, chair is also masculine, but the door is also masculine. table is feminine, pillow is feminine, blanket is masculine, room is feminine, etc. it would also be in arabic that if you say "this teacher is very nice" it would be "this(feminine) teacher(feminine) is very nice(feminine)". its extremely gendered which i dont mind but what i DO dislike about it is if you want to be neutral, the default is male. masculine is both masculine and neutral depending on context. male as neutral doesn't sit right with me personally.

how it works in your language sounds terrible! one thing i like about my language is the way words are feminised is pretty simple and consistent. doctor vs doctora, teacher (mudaris, male) vs teacher (mudarisa, female). you just add an -ah sound at the end of the profession & it becomes female.

i would argue english IS gendered tho, its just not as gendered as languages like arabic, german, spanish, etc but it is indeed gendered. especially compared to languages like mandarin, in which the pronoun for both sexes is ta (so no he nor she, just ta. context clues or the character used will indicate the sex tho). theres also stuff to be said about how "female" and "woman" have "male" and "man" in them.

ANYWAYS... heres the poll u asked for,, i wasnt sure if some of these options apply to any languages but i thought id make these options regardless in case thats simply my ignorance:

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arabic Essential Grammar #6 - The Dual

Hello hello, back again with something that really stumped me when I first started learning Arabic. The Dual!

In most languages, there is a singular form and a plural form, but in Arabic, they also have a Dual form! Used to refer to pairs of something or two people, it adds an ending to verbs/nouns which, you guessed it, then have their own conjugations!

It sounds really overwhelming, but in practice it isn't too difficult. In colloquial Arabic, the dual is really only used in regards to periods of time ( two hours ) or the parts of the body ( two eyes).

Endings

The nominative dual ending is: انِ

The accusative and genitive ending is: ...يْنِ

This is added to the singular of the word after removal of the case ending. For example:

From right to left: two books (nom.dual), book (nom)

كِتَابَانِ ------- كِتَابٌ

From right to left: two books (acc/gen.dual), book (acc)

كِتَابَيْنِ -------- كِتَابً

Special notes

If the noun ends in a taa marbuuta (), it becomes a regular ta () before the ending is added.

From right to left: Lady ( nominative), two ladies (nom.dual), two ladies (gen/acc.dual

سَيِّدَةٌ -------سَيِّدَتَانِ -------سَيِّدَتَيْنِ

If the noun ends in a hamza (), it changes into a waw () before the ending is added.

From right to left: desert ( nominative), two deserts (nom.dual), two deserts (gen/acc.dual)

صَحْرَاءٌ ------ صَحْرَاوَانِ ------- صَحْرَاوَيْنِ

Adjectives must agree with the nouns, and so they are also in dual.

عَندها عَيْنَانِ كَبِيْرَتَانِ

she had two large eyes.

If you're confused by what I mean by nominative, accusative and genitive, then please check out Arabic Essential Grammar #1!

Thanks for reading! Next week, I'm thinking of explaining either comparative/superlative or focusing on prepositions and their accompanying cases. Let me know what you want me to cover!

#Glumblr#arabic essential grammar#arabic grammar#arabic langauge#study arabic#grammar#arabic#arabic learning#arabic langblr#langblr#studyblr#tips

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is customary to think of the Renaissance as a time of great flowering. There is no doubt that linguistic and philological developments of this period are interesting and significant. Two new sets of data that modern linguists tend to take for granted became available to grammarians during this period: (1) the newly recognized vernacular languages of Europe, for the protection and cultivation of which there subsequently arose national academies and learned institutions that live down to the present day; and (2) the languages of Africa, East Asia, the New World, and, later, of Siberia, Central Asia, New Guinea, Oceania, the Arctic, and Australia, which the voyages of discovery opened up. Earlier, the only non-Indo-European grammar at all widely accessible was that of the Hebrews (and to some extent Arabic); Semitic in fact shares many categories with Indo-European in its grammar. Indeed, for many of the exotic languages, scholarship barely passed beyond the most rudimentary initial collection of word lists; grammatical analysis was scarcely approached.

In the field of grammar, the Renaissance did not produce notable innovation or advance. Generally speaking, there was a strong rejection of speculative grammar and a relatively uncritical resumption of late Roman views (as stated by Priscian). This was somewhat understandable in the case of Latin or Greek grammars, since here the task was less evidently that of intellectual inquiry and more that of the schools, with the practical aim of gaining access to the newly discovered ancients. But, aside from the fact that, beginning in the 15th century, serious grammars of European vernaculars were actually written, it is only in particular cases and for specific details (e.g., a mild alteration in the number of parts of speech or cases of nouns) that real departures from Roman grammar can be noted. Likewise, until the end of the 19th century, grammars of the exotic languages, written largely by missionaries and traders, were cast almost entirely in the Roman model, to which the Renaissance had added a limited medieval syntactic ingredient.

From time to time a degree of boldness may be seen in France: Petrus Ramus, a 16th-century logician, worked within a taxonomic framework of the surface shapes of words and inflections, such work entailing some of the attendant trivialities that modern linguistics has experienced (e.g., by dividing up Latin nouns on the basis of equivalence of syllable count among their case forms). In the 17th century a group of Jansenists (followers of the Flemish Roman Catholic reformer Cornelius Otto Jansen) associated with the abbey of Port-Royal in France produced a grammar that has exerted noteworthy continuing influence, even in contemporary theoretical discussion. Drawing their basic view from scholastic logic as modified by rationalism, these people aimed to produce a philosophical grammar that would capture what was common to the grammars of languages—a general grammar, but not aprioristically universalist. This grammar attracted attention from the mid-20th century because it employs certain syntactic formulations that resemble rules of modern transformational grammar.

Roughly from the 15th century to World War II, however, the version of grammar available to the Western public (together with its colonial expansion) remained basically that of Priscian with only occasional and subsidiary modifications, and the knowledge of new languages brought only minor adjustments to the serious study of grammar. As education became more broadly disseminated throughout society by the schools, attention shifted from theoretical or technical grammar as an intellectual preoccupation to prescriptive grammar suited to pedagogical purposes, which started with Renaissance vernacular nationalism. Grammar increasingly parted company with its older fellow disciplines within philosophy as they moved over to the domain known as natural science, and technical academic grammatical study increasingly became involved with issues represented by empiricism versus rationalism and their successor manifestations on the academic scene.

Nearly down to the present day, the grammar of the schools has had only tangential connections with the studies pursued by professional linguists; for most people prescriptive grammar has become synonymous with “grammar,” and the prevailing view held by educated people regards grammar as an item of folk knowledge open to speculation by all, and in nowise a formal science requiring adequate preparation such as is assumed for chemistry.

This is Eric P Hamp in the Britannica. Hamp (1920 - 2019) was of the same generation as Burgess (1917 - 1993), educated in philology around the time of the World Wars. This is the generation suceeding that of Tolkien (1892 - 1973).

I have highlighted two bits of temporal deixis. He sees, correctly, there having been a sort of scientific watershed around the period of the Wars.

"Nearly down to the present day" I interpret as being more metaphorical than temporal -- the hope of the postwar scientists was that in "the present day" of peace, the bright light of linguistic science would illuminate the world more than tangentially. Since he lived to 2019 he will have been well aware that this failed to happen despite his efforts, and therefore the Priscian darkness continues to hang around -- but "nearly" almost not.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello! I am back after a long, long hiatus haha. I am back with a masterlist for learning Albanian!!! I will update this with more later, I have like 592949294 other links to add, but this is a good start! Also I will be updating more, hopefully with my Spanish, German, and Arabic practice too! Here we go!

Albanian Language Resources

Free—————————————————————

BEST OF THE BEST: https://m.youtube.com/@LearnAlbanianOnline

This youtube channel!! <3 This channel has videos of actual Albanian classes being taught to English speakers. The teacher is a native Albanian speaker. He had slides of information and goes through many of the syntax rules of the language! It also helps to hear the English speaking students learning since you can compare how they sound with how the teacher sounds, and learn how to correct your own mistakes! 100% my most recommended first resource for beginners.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

https://lrc.la.utexas.edu/eieol_toc/albol (https://lrc.la.utexas.edu/eieol_toc/albol)

A wonderful resource by a university that provides many of the grammar rules for Albanian, for verbs, nouns, tenses, cases, etc.! I suggest looking at this along with a book for more context and so it is less daunting.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

https://archive.org/details/ERIC_ED195133 (https://archive.org/details/ERIC_ED195133)

The Internet Archive has a TON of free pdfs, and I found one of a book called Readings In Albanian. It has Albanian stories with an English translation side by side, and the stories start out at beginner level and increase in difficulty! A great supplemental resource.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

https://fsi-languages.yojik.eu/languages/DLI/Albanian/Volume%2001.pdf (https://fsi-languages.yojik.eu/languages/DLI/Albanian/Volume%2001.pdf)

This is a 282 page PDF about Albanian for beginners, and I’m pretty sure I found it on a site that mentioned it was for the Peace Corps or something haha. Regardless, my favorite part about this resource is that about 20 pages in, it has a sketch diagram showing the human mouth/throat regions, and a chart showing how each sound is made in Albanian with its corresponding IPA letter! (IPA: international phonetic alphabet).

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Help:IPA/Albanian (https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Help:IPA/Albanian)

The Albanian alphabet with its corresponding IPA letters. You can find interactive charts IPA letters all over the internet as well as people who read them out loud on youtube. You can use the interactive chart along with the listed letters in the wiki to learn how to say each letter properly! :)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

https://www.youtube.com/@AlbanianFairyTales (https://www.youtube.com/@AlbanianFairyTales) a great beginners resource! It has animated fairytales that are read in Albanian, with English subtitles! The reader speaks clearly and slowly, and it’s super easy to understand! Also pretty entertaining too! :)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Studying Apps (free and paid options):

Memrise: look up Albanian on desktop, add any Albanian courses that you like, and they will show up on your mobile app (you can only add official courses on mobile). They have a set of cards for one of the books I listed as well! Some of the Albanian courses on Memrise also have audio for the words!!

Anki App for flashcards

Clozemaster for audio and reading practice

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Books:

Colloquial Albanian: The Complete Course for Beginners by Hector Campos and Linda Mëniku

Discovering Albanian by by Hector Campos and Linda Mëniku

541 Albanian Verbs by Rozeta Stefanllari and Bruce Hintz

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Courses (not free):

Udemy- Learn Albanian: Beginner to Advanced by Toby Soenen and Muhamed Retkoceri

https://www.udemy.com/share/107Vpc3@bbYWSZOx0APye82YKpfkqJr5NDWMyVoVUaanoNCaHtp-jFQGWXuy7mLCnpyS6SIlpw==/ (https://www.udemy.com/share/107Vpc3@bbYWSZOx0APye82YKpfkqJr5NDWMyVoVUaanoNCaHtp-jFQGWXuy7mLCnpyS6SIlpw==/)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

If anyone has other recommendations, please let me know! :)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

hazel2468 hey @fierceawakening how did you get that written in Phyrexian? And do you know where I can find out how to say stuff in Phyrexian?

INFODUMP INITIATED

I wrote it.

(lit. "I made the text." as I don't believe we have "write.")

(declarative) + (text) + (make 1p>3p).

Alphabet, posted by WotC, is here:

I keep a dictionary here, which is not completely up to date but has most of what we know:

Typing these made me realize I'd forgotten to add "place" the noun. So uuuuuuuuh it's there now. :'-)

Various fonts are floating around. The one I use I got here:

I believe there are newer versions that have numerals in them, as revealed by the Phyrexian die given out at ONE prerelease. This one doesn't, sadly, just 0123456789 as Arabic numerals, as seen on cards.

And I learned the grammar from GuruJ's Field Guide, which is out of date now sadly:

And here we go, Phyrexian grammar 101:

Most Phyrexian words have two vowel slots in them. The vowel at the end changes (including being dropped) for conjugations, the vowel at the beginning doubles for plurals.

So take the noun pxajt_r, praetor. If I want to say praetors, I double the a. So "praetors" by itself is pxaajtr, but if I want to say "my praetors" or "their praetors," I put a vowel between the t and the r.

Verb conjugations modify that slot also.

Phyrexian sentences are structured like this:

Mood/tense marker - subject - verb (conjugated for the relationship between the subject and the object)

Sentences begin with a bar and end with a hook. If a sentence is a question, a quote, an exclamation, etc. the starting bar is modified but the ending hook is not.

Mood and tense markers tell you when something happened and in what way. For example, xe is present tense/declarative/this is true now, 'u is past tense, lo is imperative (it's not the case now, it's something someone wants you to go and do), əl is negated present tense (this is NOT happening). We know several of them but not all of them. I believe there will be a chart in the Beadle and Grimm's booklet that's coming out.

The subject goes in the middle. If you have adjectives "a green Phyrexian beast" they get glommed on to the base noun. "!Is greenphyrexianbeast fight" = "The green Phyrexian beast fights!"

If you're trying to say "the green Phyrexian beast fights the fleshlings!" that would be "!is fleshlings greenphyrexianbeast fights (where the verb is conjugated as "it toward them," see below)"

Verb conjugations are... weird as hell.

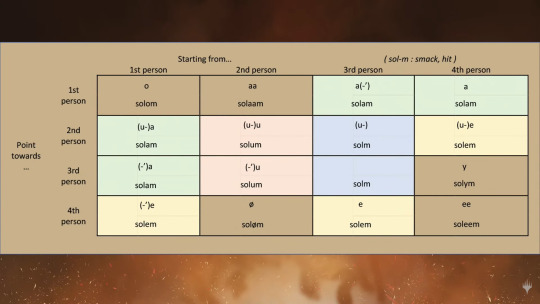

Verbs are conjugated by changing the last vowel (usually the second though some prefixes have vowels in them.) So you have a word like "sol_m," hit, and you use a vowel in the _ spot to indicate who's hitting who.

There aren't transitive verbs (verbs with objects, "she hears music") and intransitive ones ("she dances.") Instead, you look at who is doing the action and then who it's "pointing at" as in: am I doing something to/for you, or am I just doing it myself, or... etc.

This is the chart:

Nouns use this too. If I'm trying to say "my book," the noun would be "tek_t", and to say it's mine I start with me and then point at myself. So "xe tekot," "Declarative - book - me toward me," means "It's my book/The book is mine/etc."

The weird stuff in parentheses is "vowel harmony," but we haven't been told how that works yet. The possible explanation that makes the most sense to me personally is that when certain vowels are near certain consonants, that means the previous consonant's radical changes with it. I am not sure this is the case so I don't do it, which means I may slightly misspell some verbs. :-)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

16 year old X: ugh german cases are so difficult, i have to use a different ending or whatever depending where the noun is in the sentence?? i give up on this language

18 year old X: okay i'll study arabic, it has logical but relatively simple grammar!

arabic now:

#FIFTY FOUR FUCKING OPTIONS#for those curious: options are singular dual plural across the top#the three larger boxes are the three cases each of which change depending on masculine/feminine/broken plural#AND then each one is different for definite and indefinite#according to x#languages#x's adventures in arabic#and the most fun part is that most writing doesn't include the small vowels that differentiate these cases#so have fun figuring out if it's talking about two translators or a group of them!#oh and ALSO good luck with the rules for when to use each of them#which kind of sentence is it? is it after a preposition? is it this kind of subject or THIS kind of subject? is the moon in alignment?#and i almost forgot! verbs have a completely different set of cases and rules :))

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Most Essential Vocabulary #4

This time I’m focusing on the vocabulary that’s probably the most confusing in terms of grammatical gender: words with confusing gender, words from Greek, words that are feminine that take masculine articles etc etc etc

This could be its own post on grammar but I’m including it in essential vocabulary because these are things that a lot of people either don’t fully explain or that aren’t touched upon in great detail. But just know that this post includes some grammar info in addition to simple vocabulary lists

I decided to do it this way because these are words and concepts you���re going to need to know, and especially if you don’t have a teacher or are doing self-study, this is something you’ll come across and be VERY confused by

Basic Vocabulary / Vocabulario básico

el género = gender / genre [of media]

la gramática = grammar

la sintaxis = syntax

la concordancia

el sustantivo = noun el nombre = noun / name el pronombre = pronoun

el subjeto = subject

el objeto = object

el adjetivo = adjective

la concordancia = “gender agreement” [meaning that adjectives should “agree” with the nouns; lit. “concordance” or “agreement”]

-

Some Confusing Nouns / Unos sustantivos confusos

el día = day

la mano = hand

el barco = large ship, “ship”

la barca = small boat, “boat”

el bolso = purse, handbag el bolsillo = pocket

la bolsa = plastic bag, shopping bag

la bolsa / La Bolsa = stock market / The Stock Market

el rayo = lightning bolt / ray

la raya = line, stripe

el síntoma = symptom

el modelo = model [noun] el modelo, la modelo = model [profession]

el testigo = witness / something or someone that witnesses an event, “testimony” el testigo, la testigo = a witness / witness, someone providing testimony [legal]

la víctima = victim [always feminine]

el caballero = knight / gentleman / “men”, “gentleman” [as opposed to damas which is “women”; where sometimes gendered things like clothes or bathrooms are used with hombres “men” or caballeros “gentlemen”... and women with mujeres or damas] damas y caballeros = ladies and gentlemen la caballero = lady knight

el sofá = sofa, couch

el pijama = pajamas, pyjama [often used in singular while English says “pajamas/PJs”]

el karma = karma

Words like el sofá, el pijama, and el karma are called “loanwords” [los préstamos lingüísticos, lit. “language/linguistic loans”] - where el sofá and el pijama come from the Arabic/Sanskrit and the Islamic world, while el karma is a Hindu/Buddhist term

Most loanwords come into Spanish as masculine - el clóset [instead of el armario], el kiosk/el quiosco “kiosk”, el yoga “yoga”, el quipu “quipu” [from Quechua, an Inca string with knots for counting] el origami, el vodka, el samovar, el feng shui, or el básket [instead of el baloncesto for “basketball”]. There are some that come as feminine like la katana from Japanese, but it’s a rarer case

In general, most of the time a loanword will be masculine. Feminine loanwords do exist, but it’s often more professions that change forms. The most common is el chef or la chef from French as “chef”.

See also: el/la gurú “guru”, el/la samurái “samurai”, or el chamán, la chamana “shaman”. Many loanwords that are professions can exist in masculine or feminine and most don’t change forms but some do - like el sultán and la sultana, or el vikingo and la vikinga.

In my experience it tends to be more related to how long the word has been present in Spanish / Pan-Hispanic consciousness, and how easily it is to adapt to traditional Spanish linguistic conventions [like “Viking” goes to vikingo and so since it ends in -o, you could end it in vikinga]

Also note that there are some expressions in Spanish that are from Latin and considered loanwords in some cases, though they’re more established in Spanish - etcétera, or viceversa, versus, or something like a posteriori “after the fact / in hindsight” are common examples but may have other translations or versions... like de facto may be de hecho [in fact/in deed]. Others are more specifically legalese just like English.

And pay special attention to loanwords that come from English - anglicismos or “anglicisms” - as they may be more regionally used in some countries than others. Spain for example tends to frown more on English being adapted into Spanish. A common example is computer technology terms; el internet is sometimes referred to as la red “net” or “network”, and while some countries may say online, others may say en línea “on line”

One example that people use a lot for this preference towards keeping Spanish Spanish is el feedback for “feedback”, which in some countries may be seen as la retroalimentación which is literally “backwards feeding”

-

Gender Matters / El género importa

el radio = radius la radio = radio [from la radiotelegrafía; feminine la radio often refers to the actual device]

el frente = front la frente = forehead

el capital = money, capital / “start-up money”, resources la capital = capital (city) el capitolio = capital building, ruling government building capital = capital, crucial, significant [adj]

el cometa = comet la cometa = kite [probably from the trailing tail on a kite]

el cura = priest [often Catholic in my experience; synonymous to el sacerdote] la cura = cure la curita = (small) bandage, “band-aid”, plaster [UK]

el orden = order (of events), sequence / order (not chaos) la orden = order (command), military command

el coma = coma, comatose la coma = comma [the , symbol]

el cólera = cholera la cólera = rage, wrath, ire

el mar = sea [common] la mar = sea [deeper water, poetic, or significant] / “sea”, a large number of alta mar = high seas, open waters

el azúcar / la azúcar = sugar [both are correct; sometimes you’ll see either gender, so don’t be surprised if you normally see el azúcar “sugar” in one setting, but la azúcar morena “brown sugar” in a different setting”]

el sartén / la sartén = frying pan [depending on region it will be masculine or feminine]

el arte = art las bellas artes = fine arts las artes marciales = martial arts

With el arte it usually refers to “art” like a piece of art, or painting/drawing/sculpting and other forms of art.

The word las artes only really takes on feminine in plural form and it tends to mean “specific ways of doing something” as a kind of group or umbrella term.

-

Words from Greek / Palabras que provienen del idioma griego

el idioma = language, idiom

el clima = weather / clime, climate

el planeta = planet

el síntoma = symptom

el cisma = schism, rift

el tema = subject, theme

el poema = poem

el teorema = theorem

el drama = drama / drama, theater [subject]

el problema = problem

el lema = motto, slogan

el trauma = trauma, hurt

el enigma = puzzle, riddle, enigma

el estigma = stigma

el sistema = system

el esquema = schematic, diagram

el magma = magma

el dilema = dilemma, problem

el aroma = aroma, smell, fragrance

el carisma = charisma

el diafragma = diaphragm

el cromosoma = chromosome

el fantasma = ghost, phantom

And as a general rule anything [at least 99% of anything] ending in -grama in Spanish is masculine:

el diagrama = diagram, chart

el anagrama = anagram

el telegrama = telegram

el holograma = hologram

el crucigrama = crossword puzzle

You should also know that the vast majority of words ending in -ista are unisex

el artista, la artista = artist

el dentista, la dentista = dentist

el electricista, la electricista = electrician

el especialista, la especialista = specialist

el futbolista, la futbolista = football player / soccer player

el ajedrecista, la ajedrecista = chess player

el budista, la budista = Buddhist budista = Buddhist

el idealista, la idealista = an idealist idealista = idealistic

el activista, la activista = activist

deportista = sporty, “a jock”

optimista = optimistic

pesimista = pessimistic

perfeccionista = perfectionist

egoísta = selfish

realista = realistic

renacentista = Renaissance [adj]

modernista = modernist posmodernista, postmodernista = postmodern, postmodernist

derechista = right-wing, conservative

izquierdista = left-wing, “leftist”

racista = racist

fascista = fascist

socialista = socialist

comunista = communist

Additionally...

la tesis = thesis

la sinopsis = synopsis

el análisis = analysis [in plural it’s los análisis which can throw people off]

la hipótesis = hypothesis [in plural it’s usually las hipótesis]

la diéresis = umlaut, dieresis [the symbol with two dots on top like ü]

Another very specific word to be aware of is el atleta or la atleta “athlete”, which is from Greek and unisex, though it ends in A

-

Feminine Words with Masculine Articles / Palabras femeninos con artículos masculinos

This is a larger grammar topic that isn’t always properly explained.

There are certain words in Spanish that begin with A- or HA- that are technically feminine but take masculine articles in singular [el or un], but will take feminine articles in plural [las and unas]

This is a unique rule that is compared to the difference between “a” and “an” in English

The gist of it is that if that for this to occur, a noun must

be feminine

begin with A- or HA-

have its stressed syllable be the first one; i.e. the A- or HA- is the stressed syllable

For example: el agua “water”... is technically feminine (#1), it begins with A (#2), and it is pronounced agua (#3). Another one is el hambre “hunger”, technically feminine (#1), begins with HA (#2), and it is pronounced hambre

All of this is done to preserve the A sound [which is why it’s compared to “a” and “an”]. If you were to say “la agua” it would come out as “lagua” due to the two A sounds melding together in Spanish syllables. In other Romance Languages, this problem also exists and may be fixed with apostrophes [’] or other symbols to make sure a word is fully pronounced and understandable

el agua = water

el hambre = hunger, famine

el alma = soul

el arpa = harp

el arma = weapon

el águila = eagle

el ascua = ember

el hada = fairy

el ave = bird las aves = birds, fowl [umbrella term, as opposed to el pájaro an individual “bird”]

el aula = classroom

el ala = wing

el álgebra = algebra

el ancla = anchor el áncora = anchor

el hacha = axe, hatchet / big candle, torch [depends on context]

el asma = asthma

el alba = dawn

el área = area, zone

el asta = antler

el hampa = gang, criminal group

el ama = female owner, “mistress” [not in the romantic sense which is amante; the ama female form of “master/owner” which is el amo], lady of the house el ama de llaves = housekeeper [lit. “owner/keeper of the keys”; in older contexts this is the seniormost maid or the one in charge of managing the female maids; today ama de llaves is often “housekeeper” or “cleaning woman”] el ama de casa = housewife

Note: There’s also el ampa which is also written el AMPA [la asociación de madres y padres de alumnos] which is basically the Spanish equivalent of the PTA [Parent Teacher Association]... literally el ampa means “the association for mothers and fathers of students”

Note 2: There’s a Spanish drama called Las señoras del (h)AMPA which is a pun on el ampa and el hampa; being a group of women in the PTA who get involved in criminal activity - the pun works since H is silent and in this case “optional”

~

Despite the masculine article, the word itself is feminine and takes feminine adjectives:

el águila calva = bald eagle

el ave acuática = waterfowl las aves acuáticas = waterfowl [pl]

el hada madrina = fairy godmother

el álgebra avanzada = advanced algebra

agua pasada no mueve molino = “let bygones be bygones”, “water under the bridge” [lit. “passed water doesn’t move the mill”]

This also applies to the continents: Asia and África are technically feminine but if you ever used an article with them it would be el and take feminine adjectives

For more of the grammar information related to this please see: THIS POST

-

Indeterminate Feminine / El femenino de indeterminación

These are commonly adverbial phrases, but many of them use feminine or feminine plural - there’s no specific subject or noun [thus the “indeterminate” or “that which is not determined”], but many times these things that aren’t specified may take on feminine adjectival forms

a la ligera = “lightly”, “not seriously” tomar algo a la ligera = to take something lightly

a medias = “halfway”, “by half measures”, “half-assed”

a diestra y siniestra = “all over the place” [lit. “to the right and left”; diestro/a is the word for “right-hand/right-handed”, and siniestro/a is the older word for “left-hand/left-handed” which is now zurdo/a given the moral implications of “sinister”; so literally it means “to the right-hand and to the left-hand”; in some cases this expression is in masculine form but I’ve seen it most commonly in feminine]

a secas = “by itself”, “with nothing else included” / “ungarnished” (food context) [lit. “dryly”]

a tientas = by fumbling, by touch, “fumbling around”

a ciegas = blindly / blindfolded

a oscuras = in the dark, in darkness, without light [synonymous with en la oscuridad]

a solas = one-on-one, alone, privately

a escondidas = in secret, “behind someone’s back”

a sabiendas = knowingly, “knowing full well”, “consciously”

a gatas = on all fours

(despedirse) a la francesa = “to leave without saying goodbye” [lit. “to say goodbye the French way”]

a las claras = “perfectly clear”, “crystal clear”

de oídas = hearsay [lit. “from hearing” or “from what was heard”]

por las buenas = “the easy way”

por las malas = “the hard way”

Also in culinary things, you’ll see a la used a lot... like the dish pulpo a la gallega meaning “Galician-style octopus”, or albóndigas a la madrileña “Madrid-style meatballs” or huevos a la mexicana “Mexican-style eggs”

This is pretty common in most Romance Languages in my experience

#Spanish#language learning#langblr#languages#spanish vocabulary#language#vocabulario#reference#ref#so much vocab

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding Tanween in Arabic

Tanween is an essential aspect of Arabic grammar and pronunciation, often overlooked by beginners. It refers to the nunation (the addition of the sound "n") that occurs at the end of a noun, affecting how the word is pronounced and understood. This linguistic feature adds depth to the Arabic language and plays a crucial role in conveying meaning.

tanween in arabic appears in three main forms: fatḥah (ً), ḍammah (ٌ), and kasrah (ٍ). Each of these forms alters the way a word is articulated, depending on its context within a sentence. For instance, tanween with fatḥah indicates an indefinite noun that is in the accusative case, while tanween with ḍammah signifies a noun in the nominative case. Understanding these distinctions is vital for grasping the nuances of Arabic syntax and phonetics.

One of the common challenges learners face is distinguishing between nouns that take tanween and those that do not. Generally, tanween is applied to indefinite nouns, helping to clarify meaning and grammatical function. For example, "كتاب" (kitāb) means "book," while "كتابٌ" (kitābun) refers to "a book." This subtle shift transforms the word from a definite noun into an indefinite one, enhancing the richness of the language.

As you delve deeper into Arabic, embracing concepts like tanween becomes increasingly important. It not only improves your reading and writing skills but also aids in comprehension and communication. The beauty of the Arabic language lies in its intricate details, and mastering aspects like tanween can significantly enhance your proficiency.

If you're eager to learn more about Arabic and its complexities, consider exploring resources that can guide you through your journey. One such platform is Shaykhi, which offers a wealth of information and tools for Arabic learners. Whether you're starting from scratch or looking to refine your skills, Shaykhi provides a supportive environment to help you grow in your understanding of Arabic and the Quran.

0 notes

Text

Berakhot 10b: 16. "The Pear."

It appears we are building a Mandala, a map of the future Jewish world. We began with a small wall, which means future planning for all the generations we are going to free from poverty, climate migration, and mismanaged governments.

The next piece in the puzzle is what is called an Archway in Shlomo, "his health" with a prescription in it. The Mishnah says correctly one cannot ascend while there is a wall. that would mean a "cieling" which we know is not the case, because the top of the world is Shabbat, which has no constraints around it. We should be able to go right to it once we plan for it.

But we must ascend, we must deconstruct what has kept us stuck, why are we doing all of this again? Who or what is at fault, and for what reason would we ever want to do it again? The answer to this is a Tania, a tonic:

16. In Shlomo, where did he say an archway, is the inscription "wall" but where did he say an ascent, but "wall"?

The Value in Gematria is 8237, חבגז, habagaz, "a pear."

The Es, the Tree of the Knowledge of the Good and Evil was not an apple it was an apricot. Apricots and their flowers are associated not with a female in bloom but a male. We blame Evil for tempting Adam, but she was tempted by the fruit of three which was almost certainly associated with a man, hence the hard slimy slithery thing that came crawling out of the trees branches.

Except her sin, having sex before she was old enough to understand, which created a very difficult situation for her younger partner was necessary if an adult's sexual orientation was to form. As we find out this does not take place until around Day Four in Bemidbar.

Before then we have what is called a pear by the Gematria...a "troublesome agreement between a young bull and a cow that is broken. You can't go back, but you can go forward."

"The verb פרר (parar) generally reflects the undoing of a previously established agreement. Almost half of the more than fifty occurrences of our verb conveys the "breaking" or "violating" of a covenant, usually the covenant between God and man (Jeremiah 11:10, Judges 2:1) but also between just men (Isaiah 33:8). Other agreements or agreeablenesses that can be frustrated are: counsel (2 Samuel 15:34), vows (Numbers 30:9), reverential fear (Job 15:4), commandments (Ezra 9:14), even God's judgment (Job 40:8).

The verb פרר (parar) means to split or divide. It occurs in Arabic and Aramaic with the same or similar meanings, and in the Bible only twice: in Isaiah 24:19 and Psalm 74:13. Still, it takes no great leap to see the obvious kinship with the previous verb. Also note that in both occurrences, this verb conjugates into forms that are based on the form פור (pwr), and see below.

There's no verb to root פרר (prr III), but that doesn't mean there never was one; it's just not used in the Bible. That is, of course, if we maintain that the following nouns have nothing to do with the previous verb(s):

The masculine noun פר (par) denotes a young bull, and that almost exclusively as sacrificial animal. Its masculine form is פרים (same as Purim) or פרי (meaning 'bulls of'), and note that the latter form is spelled the same as the word meaning fruit (see below).

The feminine equivalent פרה (para), meaning cow or heifer (Numbers 19:1, 1 Samuel 6:7, Isaiah 11:7). Note the similarity between this noun and the verb פרה (para; see below).

Perhaps these three roots indeed developed, or where introduced into the Hebrew language, independently, but to a Hebrew audience it would seem as if the Hebrew word for young bull literally meant "breaker, violator," which gave all the more sense to sacrificing such an animal."

Do not go back is the inscription in the arch over the Eden and also the Egypt Gate, it is the tonic to all that affects a Jew's well-being. This is an important discussion to have no matter one's age. Even if one is quite seasoned one must able to articulate its meaning to younger persons with top of the mind awareness of its meaning.

Workforce planning is done in advance but so is the enlightenment of the society; both are done at all times. Once a society commits to the strategic plan for the journey from Eden to its Promised Land, its own sacred territory, there can be no going back. As the Mishnah says, society must never find itself on a flat trajectory. This is how we prevent the past from taking root after its time is done.

0 notes