#ALSO JILL AND ROSINE!!!!

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It's funny that, despite all the misogyny in the writing of Berserk, the interactions between the female characters are shown well. Casca and Farnese have one of the purest relationships in the story, which also helps Farnese's character development (as well as her learning magic from Schierke), Luca and her girls, the short interaction between Schierke and Sonya was interesting, even Casca and Charlotte had mutual respect, although Casca was jealous.

#ALSO JILL AND ROSINE!!!!#casca#casca berserk#farnese#charlotte berserk#luca berserk#schierke#schierke berserk#berserk#sonia berserk

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

i've been having a shit time...permission to post him.? this is an illusion of choice i'm giving you

#WASAJFLWNFKSND ITS SO GOOD#so loser cringe panicked and his first instinct to scramble to help her and then the Pause....i gagged#the paneling of him between jille and rosine like its perfect. you understand everything without a word#i love the detail of apostles still often having weak points that are related to their human life...#and for guts of all people to exploit this...much to think about. i'm cashing my life on the fact you'll run to save her#and lower your defense cause you're focused on her well being...smiling so wide and killing myself#also eheh blatantly devilman inspired linework :)#a#miura spiritualmente in pre ciclo mentre illustrava questo mini arco sto disgraziato sta sempre a bocconi pieno di sangue bagnato fradicio

1 note

·

View note

Text

I’m rereading The Lost Children Arc, I have once again come to the conclusion that Rosine did nothing wrong

1 note

·

View note

Text

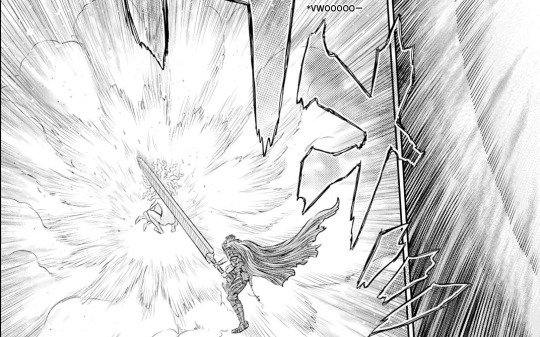

Something I noticed while looking for panels for an ask that I have queued up for the next day or two: this is the moment Guts' breakdown over his sword starts. When he does manage to hit Griffith as he's shielding Casca, but it doesn't work, his sword is stopped, and now he feels helpless and lost. Initally when I first read the chapter I assumed the 'what' was about Griffith protecting Casca again, but in full context of Guts' subsequent breakdown over his sword failing him and Griffith still being untouchable, it seems much more clearly a reaction to his failure to touch Griffith here.

And the funny thing is if Griffith hadn't magically stopped his sword here, Guts would've cut Casca in two along with Griffith. Based on that panel of his quivering hands, he might still be trying to, if they're quivering with effort rather than shock.

And I find it interesting that Guts' breakdown over not being able to hit Griffith with his sword even happens considering this moment exists. Not only is Casca's kidnapping not a factor we see him consider, Guts nearly killing her along with Griffith isn't a factor either. If he had successfully killed Griffith here, Casca would've died with him, and Guts is having a breakdown over failing to do that. He's not relieved that Griffith's power saved Casca's life from him here, he's not torn over his own capacity for destruction, he's in despair that his sword was stopped.

It's also a neat parallel to the Lost Children arc, the moment when Jill shields Rosine. The protector/protected roles are reversed, but either way Guts had the opportunity to kill one opponent and one innocent, and in both instances he tries to do it only to be stopped by an unforseen circumstance (Griff's invulnerability, a crossbow bolt from Jill's dad and Farnese's knights finding him).

That Guts in a rage aesthetic, sword held high, one glowing eye in a dark demonic silhouette, lots of visual similarities here.

Maybe Casca's endangerment is a coincidental detail we're not meant to examine too closely, it's hard to say with the new team stlil finding their feet. But yk, it does fit Casca's magic dream therapy sequence, where the Guts in her subconscious mind nearly kills her while fighting Griffith, and of course it fits Guts' whole blacking-everything-else-out-in-a-rage beast of darkness thing. It's a solid illustration of Guts' black-out rage, a theme so significant that it's what the story is named after.

It's a dark moment and I hope it gets some attention or at least acknowledgement in future chapters, but at the very least it's a fitting addition to this fight with Griffith, and it's potentially interesting that it hasn't even crossed Guts' mind in his despair.

#could also be more foreshadowing for guts killing innocents when the armour takes him over in presumably the next few chapters#fingers crossed lol#chapter 367#character: guts#theme: revenge#theme: inner monster

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

The God of Misty Valley

The Beast of Darkness broke loose and is offering Guts power.

In exchange for yielding himself.

It seems like the Beherit will come into play it was hinted several times he might be it's new owner and would use it.

But I think it's a red herring. I have a theory that the giant cedar tree from Misty Valley will give him his power up through a wish, I think it is a god.

The tree seems like it's sentient it showed Puck a vision of the elves that used to live their.

In the story of Peekaf the Misty Valley elves were able to grant a wish.

And Guts even compared it to the sacrificial ceremony. I think that aspect of Peekaf's story will turn out to be true and that it was because of the power of the giant cedar tree.

I think there are clues that the tree is a god. Schierke explained that many churches were built on pagan shrines.

It turned out the church in Enoch Village was built over the shrine of the Lady of the Depths who was worshiped as a river god.

There is a church in Jill's village. I think it was shrine to the giant cedar tree and that it was worshipped as a god.

It was revealed by one of Jill's kidnappers that pagans lived around her area that worshipped trees.

I think there is evidence that the giant cedar tree is powerful. Misty Valley reminded Puck of Elfhelm which was a powerful land.

Also the atmosphere of Misty Valley was very similar to Elfhelm.

To how this will be possible. I think Guts and Puck was linked to Misty Valley similar to Schierke, Farnese and Casca being linked to Elfhelm. I think it's why Puck did not disappear along with the rest of the elves from Elfhelm.

Schierke theorized that the Moonlight Boy was a manifestation of Danann but I think this was foreshadowing of what the Beast is. I think the Beast is a manifestation of the giant cedar tree.

I think he possessed Guts offscreen. The Beast of Darkness did first appear in the Misty Valley Arc and I don't think that is a coincidence.

I think there is hint that the Beast of Darkness is a spirit possessing Guts. When Guts is taken over by the Beast when wearing the Berserker Armor it's similar to Schierke becoming one with a spirit.

It was played for laughs about Puck usurping Danann's throne. But I think it was foreshadowing that he is the ruler of Misty Valley. I think because of the cedar tree linking itself to Puck.

I think the cedar tree will use Puck to grant Guts' wish using his True Name which can be used to control an elf.

Humorously it was shown that Magnifico was trying to learn the True Names but I think it was foreshadowing that this concept would be use.

I think the giant cedar tree and Misty Valley still exist in the Interstice.

Flora's spirit mansion tree rotted in the physical world but it still existed in the Astral World.

As to why the giant cedar tree would get involve I think it is personal. Rosine became an Apostle during the full moon, when magical forces are at their strongest. I think the tree god was watching.

I think the cedar tree had an oath with the people from Jill's village and was angered that demons had targeted them and defiled his valley.

Also I think it blames the God Hand for the disappearance of the elves.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the best adaptation of Berserk? Looking at the content, not the visuals. It's been a while since I watched the 2016 film adaptation and I could be wrong, but isn't this the most accurate film adaptation of the arc? Yes, there is a changed third episode, but the script for this episode was written by Miura. I've heard many times people complain not only about the visuals, but also about the story. They say he's boring, but isn't that because Berserk himself became a little… boring after the Golden Age? Many people praise the plot of the 1997 anime, although it is essentially fan fiction and not an accurate adaptation. They usually say that the 1997 anime comes first, the movies come second, and the 2016 anime comes third. I think it's exactly the opposite (anime 2016-movies-anime 1997) because isn't the 2016 film adaptation the most accurate adaptation of some Berserk arc? Why is the 2016 anime so bad apart from the visuals? I'm interested to hear your opinion <3

Thanks for the ask anon! It's been a while since I've gotten some asks in my inbox so I'm very happy to answer this.

Truth be told, I'm not really a fan of any of the adaptations. I don't like how the word 'masterpiece' is thrown around when it comes to praising the series, but when talking about its adaptations, I've referred to it as an "unadaptable masterpiece" more than once. I don't think that any of the Berserk adaptations have truly and decently adapted the girth that is the Golden Age, and by extension, the Conviction arc.

With the 1997 anime, it's the most accurate in regards to its adaptation to the Golden Age but I find the pacing to be extremely slow at times. With that being said, I applaud it for adapting all of the important Griffith scenes (such as the Genon flashback and the Tombstone of Flames) because those are some of my favorite parts of the Golden Age and it's unfortunately the only adaptation to contain those scenes. The soundtrack is great, the 90's nostalgia is there, and it was a good first crack at such a heavy arc. Decent, but not good.

It gets complicated for me with the ova trilogy because I do think they're good when it comes to portraying Guts and Griffith's relationship as a heart-wrenching, avoidable tragedy. The iconic "Do I need a reason?" line? The way that Guts and Griffith's eyes just absolutely soften when they see each other from across the ballroom? I fold every time. Which is why I get so angry when I remember that SO MUCH had been cut. These movies were the introduction to Berserk for a whole lot of people and more often than not, the only adaptation of Berserk they'll ever watch. So many uninformed and brain cell melting takes and opinions come out of this and it makes me so upset because so much of what was cut is incredibly important to understanding Griffith. But the important Griffith scenes aside, Charlotte's presence was cut down significantly too. Granted it would've been super uncomfortable and downright disturbing to watch her father assault her, but the lodestone scene was a very nice moment between her and Casca. And it would've at least given her character a lot more depth. Also speaking of Casca, why the fuck is she whitewashed??? Don't give me that shit about "the lighting" either. She's clearly lighter, appearing much more tan than brown. I've already voiced my criticisms about Casca's character before but her being whitewashed in the most popular and well known adaption doesn't sit right with me.

And lastly, the 2016 anime. Frankly, I don't like it at all. I find the animation to be way too off-putting for me to even make it through a single episode, and just like the ova trilogy, a lot has been cut. It left out the Lost Children arc for God's sake! That's my second favorite arc in the entire series. Although maybe it's good that Jill and Rosine weren't subjected to an adaptation unworthy of them. The 2016 anime feels like a very hasty summary of the Conviction arc instead of an actual adaptation, which is a shame because Conviction is an arc that's detrimental to how everyone's post-Eclipse arcs are established. You asked if it's the most accurate adaptation of a Berserk arc, but it's not. Far from it. It's the least accurate by a long shot. If you're going into it after watching the 1997 anime and the ova trilogy, you're going to be extremely confused.

Overall, my ranking of the three adaptations goes like this: the ova trilogy, the 1997 anime, and then the 2016 anime. This isn't to say that anyone's preference for one adaptation is valid. We all love this dark and crazy world created by Miura afterall.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Here's an interesting thought experiment:

Lost Children but instead of Guts...it's Samus

Who y'know would probably have a soft spot for abused little girls like Jill and Rosine on the one hand

But would also mayyyybe not really dig Rosine's whole shtick of kidnapping little kids and murdering their parents during village raids due to...personal experience

Oof. I honestly don't know what Samus would do against actual children. Guts forced himself to see every "elf" as a monster for the sake of his revenge, and even he grew disgusted with his own actions. I can't see Samus shooting at Rosine at all, even if she herself is harming other children. Unless she really was ordered to :(

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

i saw somebody the other day acting like berserk is a lesser story because you cant have any ships in it and im literally still so mad about it

#they were like 'we cant ship farnese and serpico and we cant ship rosine and jill > : ('#and like YEAH WHO CARES?#ALSO ACTING LIKE ROSINE AND JILLS DEAL CANNOT EXIST JUST BECAUSE ROSINE TOLD GUTS JILL HAD A CRUSH ON HIM#WHILE ACTIVELY TRYING TO KILL HIM AND PROBABLY JUST MOCKING HIM AND MAKING A WRONG ASSUMPTION#IS STUPID AND I HATE IT HERE

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading for Redemption in Post-Golden Age Berserk

Below is some rambling thematic/character analysis and vague gay flapping about how Berserk could have *ahem* or should have ended. So please enjoy my little theory brain working on overdrive again (if you like) as I discuss how Griffith and Guts’s relationship could have been resolved through one decisive act... No it’s not killing Griffith, get out of here!

To follow are some ideas including (pearl clutch):

Griffith’s “redemption”

An act of love between Guts and Griffith

Guts becoming a shield instead of a sword as the culmination of his character arc

A second (!) sacrifice

This is a bit of a grasping-at-straws deep-dive into post-GA Berserk, but one that is I think actually surprisingly well-substantiated, that is if you’re willing to follow me into the vague realm of thematic parallels. For those of you who were unsatisfied with the way this latter part of the story treated G&G's relationship, I hope you might especially enjoy it.

Caution: I’m basically reading the entire post-GA story through the lens of Griffith and Guts’s relationship, because to me that’s the emotional and narrative heart of the story. I think we can in fact view a lot of post-GA relationships and characters through this lens, and the story becomes, imo, richer for it. Think Jill and Rosine, Serpico and Farnese, just for some easy ones.

Please keep in mind that this is obviously 1000% empty speculation and useless headcanon at this point, and it relies on drawing connections between seemingly disconnected scenes and characters, but it’s fun to think through this stuff, so I hope you enjoy this little journey into my sad gay heart and hopefully it’ll at least give you some food for thought by the end.

I’m also relying on previous meta written by myself and @bthump, so if you feel you’re missing context for any of this, please check out my previous two metas and basically bthump’s entire archive (an intimidating prospect that I assure you is totally worth it).

For all those simply interested in “Guts chops off Griffith’s stupid head”-esque discussions... Well, you’re welcome to stay... but strap in.

Part 1, On Post-Eclipse Griffith: Griffith Needs to be “Redeemed,” But What Does That Actually Mean?

The way I read NeoGriffith, and basically every moment post-Eclipse for Griffith generally, is that he is living his own personal hell. He is lonely, he is miserable, he’s playing prince charming in an empty and unfulfilling (heterosexual) relationship with Charlotte. He is loved and adored by everyone around him, he is the bearer of light, but I think it’s clear that in spite of this (and perhaps because of it) he still hates himself.

His last act as a human soul was to destroy himself by destroying those around him, and that moment was crystallized into the form of Femto.

And indeed, that shadowy other half remains very much present post-Eclipse. Femto and NeoGriffith are shown to be inextricable mirrors: the charming outward persona and the festering self-hatred beneath the mask. The two are halves of the same coin – Griffith’s two coping mechanisms, forever intertwined after the Eclipse.

We see this at play in “Backlighting” especially, where it’s made clear that Femto is always “with” NeoGriffith.

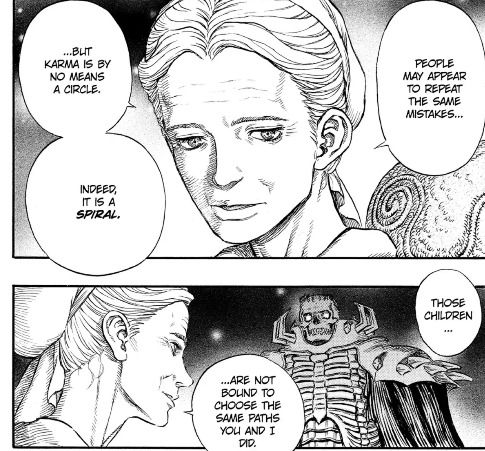

(Chapter 303, “Backlighting”)

(And side note, I hope to eventually post another meta about this motif of light/darkness in post-GA Berserk at some point… probably in like three years or something given my posting history lol)

In addition to this continued presence of Femto as an embodiment of Griffith’s self-loathing, we are also clearly shown his loneliness as NeoGriffith, and also his dissatisfaction with his life, in every panel where we see him standing alone/isolated from his new Band of the Hawk.

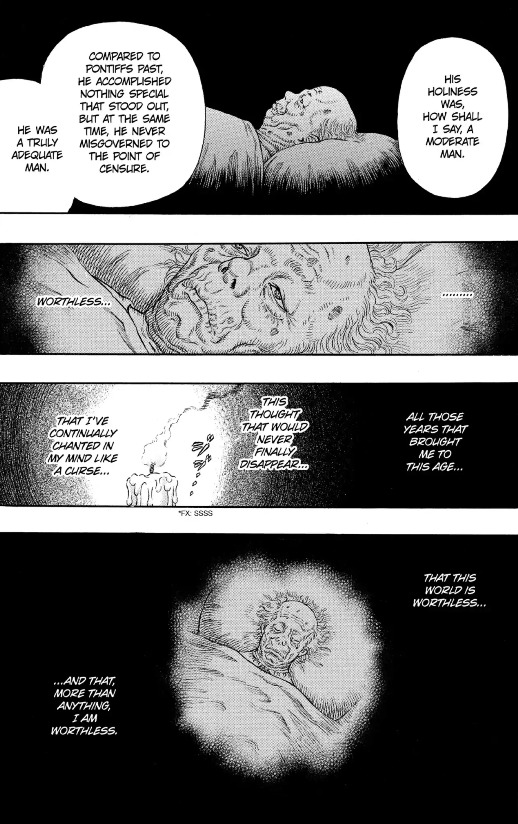

However – and this is where I begin my pitch for reading the entirety of Berserk through the Guts x Griffith lens – I think his mindset is also communicated to us as reader indirectly, through the voice of a different character entirely: the Pontiff. A minor character to be sure, but take a look at his inner monologue in Chapter 264. It’s both visually and rhetorically associated with Griffith.

See the parallels in the theme of repression of personal desires, a zealotry-based leadership role, light/darkness interplay and mirroring, castle and hawk wings imagery, and an assertion of worthlessness:

(Chapter 264, “Divine Revelation”)

Tell me that doesn’t sound suspiciously similar to someone else we know!

Now this is the type of thing that I find post-GA Berserk does a lot – it gives us these highly emotional moments about characters we really don’t know or care very much about as readers. It can lead to a bit of disconnect and feeling that the story has cheapened itself by highlighting these random characters. However, at least for me, this recurring pattern can be recontextualized by reading these charged moments as analogues for other characters, in that they are giving us insight through parallels with characters we know and care more about. I realize there is no in-text justification for doing this, but it provides a richer post-GA reading experience, at least for me, and hopefully for some of you as well.

So, through the Pontiff, I think we’re being granted a small glimpse into what Griffith might be feeling in his new life. Lest you think I am grasping at straws, which I totally am, nevertheless I offer you this: to Griffith too, the world in his new life has become a pretty painting, a castle on the wall, but he is left cold and lonely, stranded in the dark. “There was no love, hatred, nothing.” The absence of everything, specifically his everything, the world-shattering pain and love that Guts represents for him, remains a void in Griffith’s life.

(And as a bonus, also note the scene’s prominent light/dark reflection of the black and white Hawk – i.e., Femto and NeoGriffith, as visually paired and inverse)

Now, what does this have to do with Griffith’s capacity for “redemption”? Well, according to my previous readings of Griffith’s motivations behind sacrificing Guts and the Hawks, I do not believe that he feels any remorse or regret about the sacrifice. That’s because in order to feel regret, he would have to believe that both:

There was another choice he could have made

He deserves to feel something other than pain

I would offer that regret doesn’t belong in a headspace where Griffith thinks he is currently paying the price for his actions – with his emptiness, eternal suffering, repression, self harm, all of it. His life as NeoGriffith is, for him, both imprisonment and penance – it is the embodiment of the idea that he has to live as a monster. This is him reaping what he’s sown, "bear[ing] his evil and confront[ing] his destiny" as Void puts it.

In other words, he can’t regret his decision because he’s living with what he thinks he deserves. To admit otherwise is to admit that he doesn’t deserve this torment, which should be unthinkable to someone who still wears his self-loathing as a literal suit of armour.

And yes this perspective is extremely selfish, it’s not seeing the world from the perspective of those who he has harmed by his actions, but, evidently, that’s what self-loathing can do to people.

To conclude Griffith’s arc in a satisfying way, I would have liked to see him confront his actions, to experience regret, to repent from a non-selfish perspective. However, to do so, he would have to finally see himself as someone worthy of being loved, and to recognize that he in fact was that person once. That the sacrifice was a mistake after all, because he was loved by Guts all along.

The story has set up the fact that Griffith still absolutely needs Guts. Griffith at his most traumatized, at his moment of greatest despair needed (and now still needs) help to escape from the hell he’s living and thinks he deserves. And it’s all because he’s the victim of a misunderstanding that has led him to mistakenly believe he was never loved and was never worthy of love.

He chose the sacrifice because he was told by the Godhand that he is too dirty, too evil, to be redeemed or to be loved, in spite of Guts loving him all along. This is the belief that tore their relationship (and the world) apart. And it was a mistaken one! Guts is the one with the ability and the willingness to give him that: to right that narrative wrong. From this perspective, the only thing that will “save” Griffith, to allow him to repent and acknowledge what he’s done was a mistake, is an expression of love from Guts.

Now, I would have believed that this ending was unlikely or impossible except for the fact that Guts is not only aware that he fucked up with Griffith and is consumed with regret over it, but he has also spent the rest of the story trying to right that wrong in misguided ways (i.e., through Casca instead of through Griffith). And given Guts’s inability to fully embrace his hatred of Griffith, because he still loves him, I suspect that in fact all it would take to be swayed into redirecting this back to Griffith is for him to understand what Griffith is actually feeling (still human underneath, heart beating for him and otherwise dead inside, consumed by self loathing, believing he isn’t worthy of love).

I basically think the post-GA story was set up to end with Guts demonstrating his love for Griffith in some way. That’s the reason why the story continued after that point. And in fact, Guts being given a do-over has been foreshadowed explicitly – karma is a spiral, and “those children” have the chance to right the mistakes from the first time around.

(Chapter 222, “Claw Marks”)

Some sort of do-over seems both narratively and generically necessary here – Griffith has been operating since their second duel under a mistaken belief about how Guts felt about him all along, and Guts has the key to fix it.

If the narrative ended without righting that mistake, undoubtedly in the most juicy, melodramatic circumstances possible (e.g., perhaps it would be too late to matter as both are poised to die anyway), it would be both narratively unsatisfying and incomplete. This mistaken belief – that Guts never loved Griffith – lies, after all, at the heart of the story, it’s what made everything go wrong in the first place. Narratives about misunderstandings must correct them for the emotional payoff, I think it was simply a matter of when it happened and under what circumstances.

Part 2, On Foreshadowing: There Are Lots of Interesting Parallels Between Pre- and Post-GA Berserk, OK?

One idea for how this narrative resolution might have gone down I’m also taking from a non-directly G&G related plot beat in post-GA Berserk.

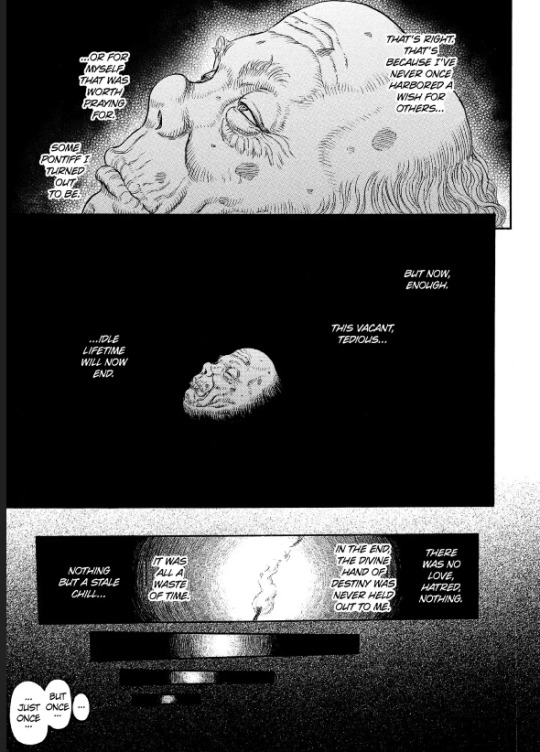

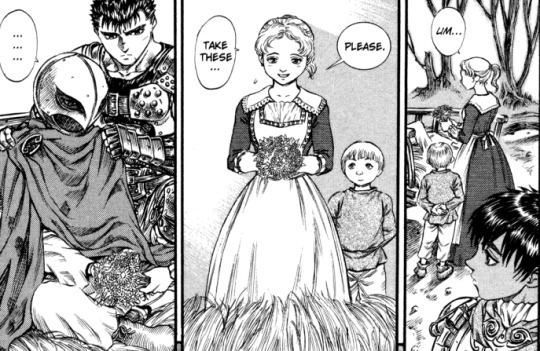

Now, we all know about the explicit and more subtle (read: gay) parallels between Rosine/Jill and Griffith/Guts drawn throughout the Lost Children Arc. But what if I were to suggest that the final note of their relationship, Jill throwing herself on top of Rosine, might have offered a thematic parallel to Griffith and Guts at the end of the story? Perhaps Guts might do the same in a moment of love and pain:

(Chapter 116, “The Way Home”)

This hope and a prayer (i.e., super amazing thematic prediction that isn’t based on any concrete evidence whatsoever) would have been a neat conclusion for the story, tying together a bunch of story threads in an incredibly simple and elegant way:

The narrative misunderstanding/wrong at the heart of the story (i.e., that Guts never loved Griffith) would finally be finally put right

It provides a neat resolution to both Griffith’s and Guts’ character arcs

The parallels are on point

To expand on this, in terms of character arcs, on Griffith’s end, a moment like this, perhaps where Guts bodily protects Griffith from a killing blow, would finally allow him to correct his fundamentally negative and damaging view of himself that has defined his entire character arc, the view that has led him to believe that he should bury himself under self hatred and repressed desires. Because if Guts sacrifices himself for him, it would not just tell but show Griffith that he was in fact loved all along. This act would finally provide him with a genuine sense of self and self worth through a love that is entirely reciprocated (instead of through dreams: either selfishly or selflessly pursued).

This would be incontrovertible evidence of Guts’s love for him; one of the main problems in resolving this narrative misunderstanding is to create a situation where Griffith can actually believe that Guts’s expression of love is genuine – how can he possibly believe this through anything other than an extreme, incontrovertible act? And so I offer Guts sacrificing his life for him.

On Guts’s end, it would finally allow him to take his life into his own hands and truly self actualize – he’s been passively reacting for most of the story, and this would be a chance for him to actively do something, to finally make a meaningful choice, and it would be an act that would allow him to unburden himself of hatred, regret, guilt, etc. It would also fulfill what I think of as one of Guts’ most deeply held personal values and beliefs – his desire to save someone through an act of love rather than through his sword (and yes I read Guts as fundamentally a caretaker at heart, more on this below).

In terms of parallels:

The theme Berserk often returns to about the merits of being with someone v. the burden of “protecting” someone would finally be resolved with Guts (likely) failing to protect his loved one, but also in doing so finally being with him in their (likely) dying together and finally fully coming to an understanding of each other.

Guts realizing that his life can mean something outside his sword (what he’s been looking for his whole life) – basically becoming a shield instead of a sword at the end of the story.

Griffith’s sacrifice at the end of the GA would finally be mirrored by a reciprocal act by Guts in the form of a second sacrifice, but this case one that is born out of love instead of hate. This idea in particular I need as a reader so badly, particularly because the acts they each took on behalf of the other across their relationship are so uneven – Guts has just been so passive overall and as a reader it would be incredibly satisfying to have him take up his role as the protagonist and take the final, decisive action to resolve their relationship. This is also why I can’t get on board with any resolution where Griffith has to take another action “for” Guts – imo the resolution of this arc should rest on Guts’ shoulders.

Basically, it would give both of their lives meaning in one swift move.

And what’s especially neat about this potential conclusion to the story is that I think the story gives us some really provocative small moments that foreshadow it, where we're shown that love can triumph over hatred.

At least some sort of reconciliation/act of love comes up again and again in the story, though in seemingly unrelated situations that imo just have too much in common with Guts/Griffith to dismiss outright. There’s of course the “karma is a spiral” moment and the Jill & Rosine parallels that I’ve mentioned, which suggest that it’s possible to still right a deep-seated wrong, to “save” (at least emotionally, if not physically) someone who has fallen into darkness through an act of love.

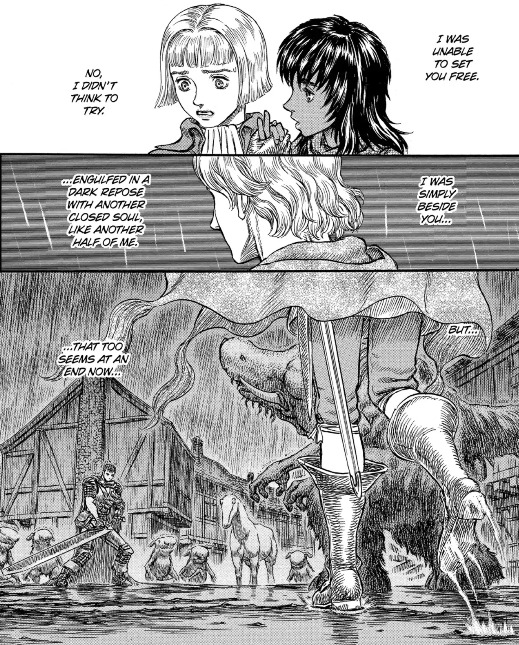

But there’s also the idea of saving one’s “other half” “from being torn to pieces in the storm” via Serpico and Farnese:

( Chapter 211, “Evil Horde Part 1”)

God, this passage. First off, I think Guts and Griffith's relationship is being explicitly paralleled through the word choices (“other half”/”half of me”), but also because this sentiment is basically echoing all of Guts’s paralysis and helplessness at the moment of the Eclipse.

Like Serpico, he too was unable to set his loved one free from a prison of darkness and hatred, something perfectly visualized in Guts trying in vain to pry his way in to Femto’s eggshell – as well as all the regret, hatred, and feelings of impotence (i.e., the darkness) that came along with that failure.

The “I didn’t think to try” aspect to this is also relevant and interesting given the changed context of pre- and post-Eclipse G&G. Guts during the GA didn’t see what Griffith was going through as leader of the Band of the Hawks as being a prison, a burden, or damaging to his sense of self; he simply thought he was “flying alone” above all of them but couldn’t conceive of how personally devastating that was for Griffith. Now though, after Guts has taken up the mantle as the RPG group leader, he’s probably in a better position to understand this and to also understand that something better is preferable for both of them, even if it seems like it’s forever out of reach.

And yet Serpico’s statement seems to be a really significant idea in light of all this – it’s suggesting that maybe this dilemma isn’t over – that maybe Guts can still see to it that his “other half isn’t torn to pieces” in some new storm that’s brewing.

I also submit Case B: Luca and her tribute to “the chick [child] that died within the egg”… Now, while she’s specifically addressing Eggman throughout this scene, this moment also explicitly parallels Griffith as a similar child who died within an “egg.” Compare:

(Chapter 83, “God of the Abyss” and Chapter 176, “Determination and Departure”)

This is a “sinner’s” tribute to a child who died too young, who is now buried and alone, who has no one to love or mourn him. Again, I think the parallels to both Griffith and Guts are there, telling us that even those people who have done terrible wrongs, who have lived shameful lives, can still be loved (i.e., mourned), and that trauma does not have to define you or your legacy.

And this connection doesn’t just appear through the language choices (sinner, chick) but also through mirrored imagery between the above scene and these ones:

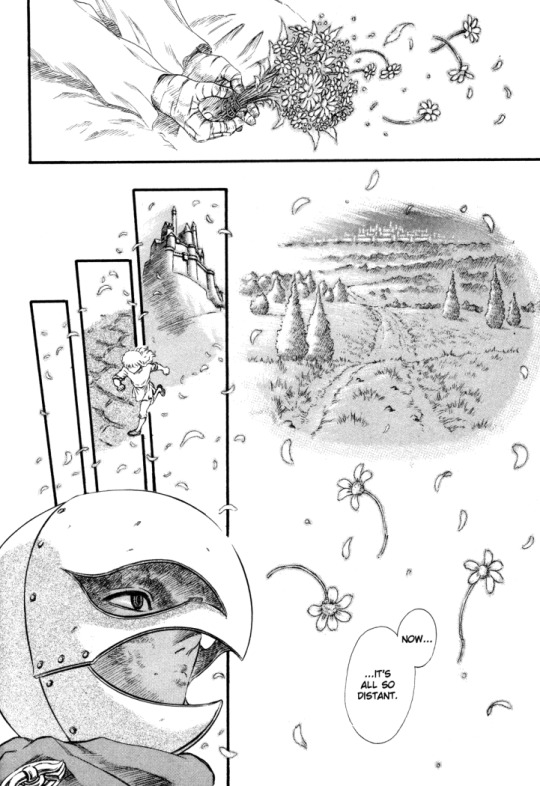

(Chapter 59, “Devil Dogs Chapter 1” and Chapter 331, “Spring Flowers of Distant Days Part 3” although admittedly the latter one comes much later, so it only works as a retroactive parallel)

The essential thing that Luca’s tribute is telling us as readers, is that in mourning (a form of love) someone evil and despicable, love offers the counterpoint, specifically the remedy, to hatred.

Part 3, On Narrative Conclusions: Why a Second Sacrifice?

So, my dumb little brain is telling you that the conclusion of the story should have been a scene where Guts makes a sacrifice for Griffith. But why?

Well, most importantly I think it offers a crucial structural parallel to the other sacrifices we've seen throughout the story. That's because there are some important distinctions to make between this sacrifice and earlier ones. This sacrifice would not be with a behelit. It would not be the consequence of magic or the gods meddling, the strings of fate, or an action born of hatred. It would not be a sacrifice that destroys people but instead one that actualizes them.

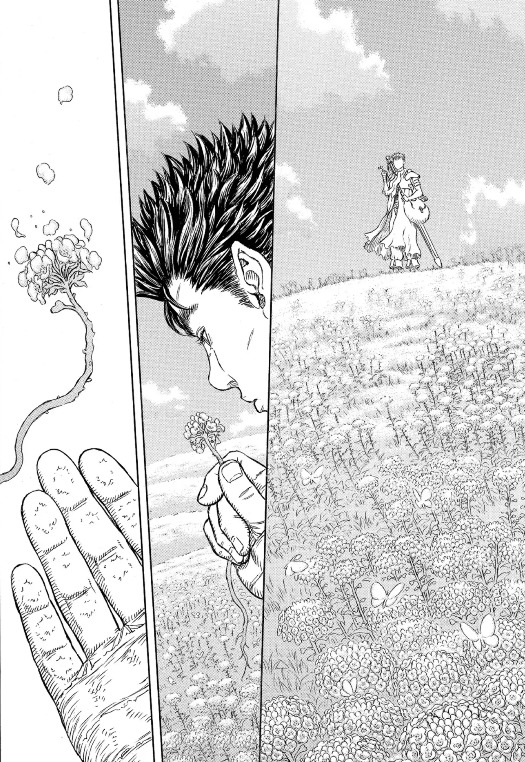

I think this is the best possible ending to the story, in large part because Guts demonstrating his love for Griffith is what was been set up to unburden both of them from their current armours (see: Femto) of imprisonment and their respective “shackles” of hatred.

(Chapter 202, “Magic Stone”)

Now, on a character level I think it would be overly simplistic to say that the story is telling us that Guts will forgive Griffith. I think both characters too far gone for simple forgiveness between the two of them, I don’t think that was ever a realistic outcome to their story.

What they need instead is shared understanding and a shared declaration of love to help them realize who they are as people (loved and worth loving). That's why I think the Jill/Rosine parallel works so well, because it only needs to be an irrational action on Guts’s part (like throwing himself in front of Griffith to protect him) as a definitive expression about what Guts wants to do, outside of his usual waffling as well as any obligations or duties he might feel. A sacrifice by Guts would be a simple action, one taken because of him following his heart.

Guts making a genuine sacrifice for his “other half,” to save him, to finally know himself and know another person, creating a deeply honest a connection through an expression of love… tell me that’s not a perfect conclusion to a story about trauma and its devastating impacts on people and their relationships with each other.

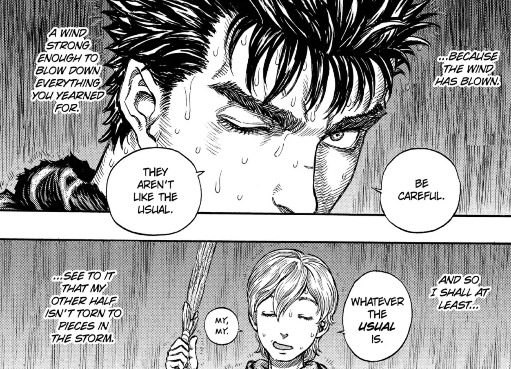

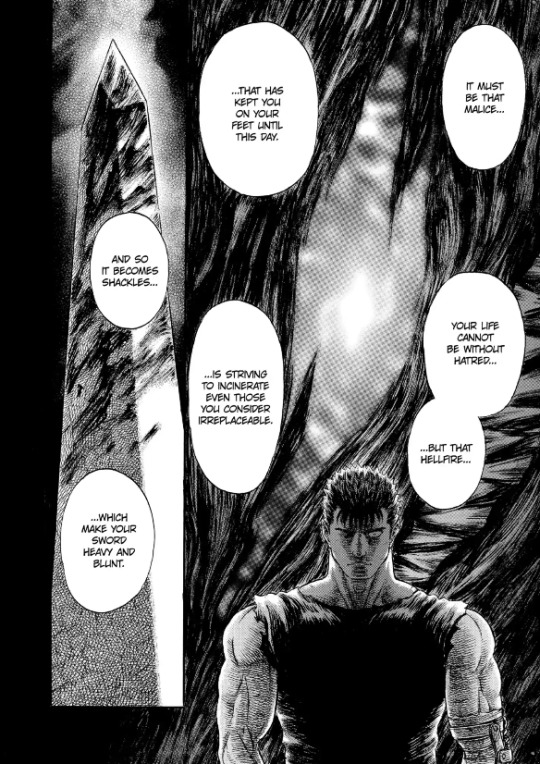

Because I think it’s clear that the idea of not being able to truly hate Griffith is just as relevant to Guts as it is to Rickert:

(Chapter 336, “Pandemonium”)

Guts says this to Rickert while looking sad, not angry. Maybe, just maybe, Guts is aware of his own feelings on the matter too. Perhaps he's as much speaking aloud as to himself here.

The wrench in Guts’ desire for that all-consuming hatred is, of course, that residual love he feels, the structural equivalent to Griffith’s own bthumping heart. In that light, that love could very well make Guts do something spontaneous and irrational, essentially bursting through his own darkness to definitively break the hold of the hatred that’s shackling him. Especially if he somehow comes to understand the pain and love that Griffith is still feeling too.

Now to be clear, I don’t think forgiveness necessarily needs to come into the equation here, and I think it’s psychologically reductive to say that Guts can overcome his trauma this way. I think those wounds run too deep, but conversely I think that his love does too. Basically I think the resolution to their arc absolutely could and should have remained messy as fuck. An act of love born from a crippling wound is as honest as it gets for these characters.

Now, the narrative explicitly tells us after it declares that Guts is shackling himself to hatred through his sword, that that the way Guts will go about this unburdening/unshackling of his hatred is through Casca, by taking up the sword for her sake as a “protection against hellfire” AKA as a protection against his own hatred:

(Chapter 203, “Elementals”)

But we see repeatedly that this is simply a “path [he’s] chosen,” not necessarily the only path or, indeed, necessarily the correct one. In fact, we see that this path is not actually succeeding at protecting him or Casca from anything. And that’s because when we look at Guts’s actions, he isn’t actually working to protect himself from his own hatred, because he can’t help but be reminded of his own trauma as a result of Casca’s trauma:

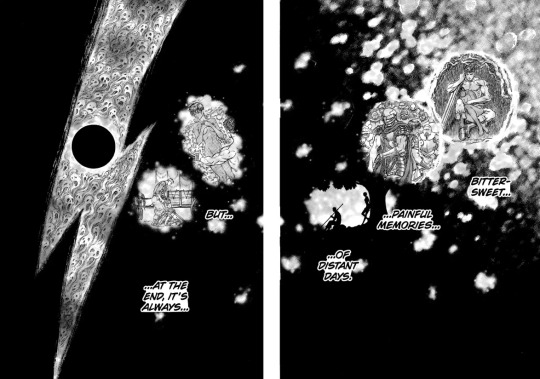

(Chapter 287, “Bubbles of Futility”)

“At the end, it’s always.” Trauma lies at the end of this road named Casca. And I think that’s because Casca is no longer really an independent person to him; she is a symbol, a burden, and a force that keeps The Struggle alive; she’s a means, not an end in itself. At the end, instead, it’s always that wound, and purposefully so. (And this interpretation is of course aided by her being a veritable doll throughout the majority of the rest of the story).

The Struggle and Casca herself aren’t presented as what Guts objectively wants as an end consequence of his actions – they are presented as the means towards something else.

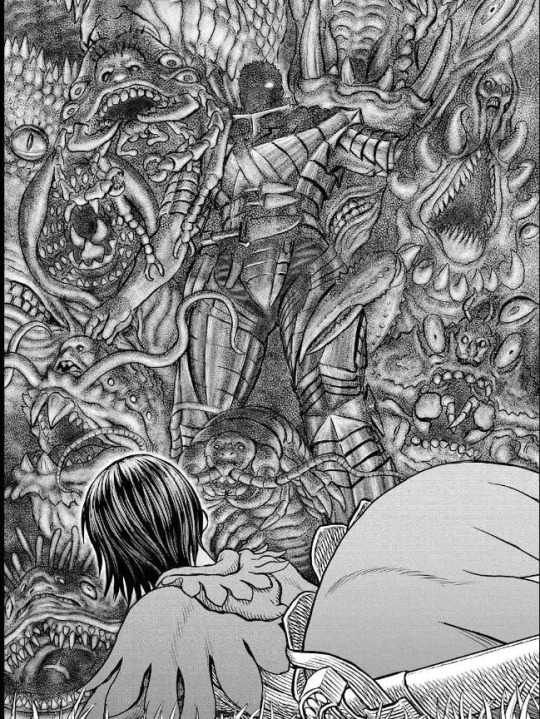

The story drills into us the idea that this goal of restoring Casca is based on neither a positive and altruistic motive on Guts’ part, nor is it something that’s destined for jolly good things. See: the ominous foreshadowing with “The power to protect someone and the power to be with someone are different,” “fixing” Casca despite her own wishes, and Casca also seeing Guts as a monster from the Eclipse in her own right. In this light, I think it’s very appropriate that Casca views Guts in exactly the same way:

(Chapter 359, “A Wall”)

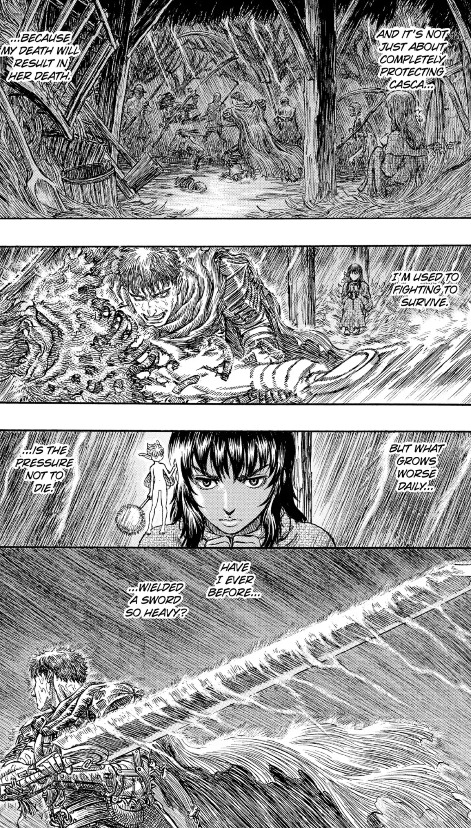

The “path [he’s] chosen” – The Struggle, the burden, the guilt, or everything that Casca is to him – isn’t good for Guts. It’s a path shackled, and it’s one that makes his sword heavy with guilt, anger, and hatred.

(Chapter 188, “Winter Journey Part 2”)

But we’re told that this isn’t a path that’s been set in stone (re: “those children are not bound to choose the same paths you and I did”). Guts has the power to choose differently than continuing to fight as a sword.

To sum up, I read Guts as explicitly thinking of Casca as a duty/chain/burden rather than as something personally fulfilling or as a genuine escape from his hatred. At the end, it’s always. And that’s why the conclusion to his story, at least imo, should lie somewhere else.

(And sidenote, this dynamic between duty and desire (giri and ninjō) is a huge part of the Japanese cultural (literary, dramatic, and cinematic) tradition, and I think it’s pretty clearly at play here, where Casca represents duty, Griffith represents desire).

To me, this is the whole point of Guts still being “bound” to Griffith, because in his heart of hearts, he still wants to be, because can’t ever truly hate Griffith, because he’ll always love him/be in love with him. And accordingly, any act Guts takes for Griffith at the end of the story will not happen because he feels obligated or burdened, like he does with Casca, but because on some level he genuinely wants to embrace love and be free of the burden of his Struggle and hatred.

~~

Small tangent on Guts: the question of what Guts actually wants is obviously crucial to the story, he’s the protagonist after all. But what does he want? To save Casca? Well, he did his part there. What now? To live with Casca? Continue The Struggle? To kill Griffith? Honestly, this question is actually really fucking ambiguous, which is kind of shocking for a protagonist (supposedly) three-quarters of the way through his story. (My headcanon reason for this ambiguity is that Miura wanted to maintain plausible deniability that this story is gay AF, which is also the reason behind Griffith’s motivations being so ambiguous as well).

To make this question a bit more abstract, if Guts was free to do whatever he wanted – as in, if he didn’t feel obligated to do what he’s supposed to – what would he do? If we can’t answer that question, I think we can’t truly understand Guts as a character.

My own answer to this question lies in reading those moments we see him as a caretaker as the most genuine senses of who Guts is as a person.

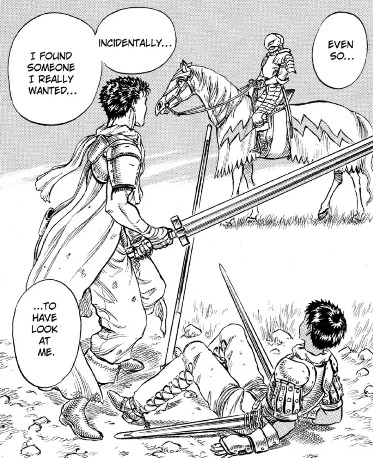

(Chapter 1, “The Golden Age”)

Those desperate moments of grabbing his mother’s hand as well as him trying to return the flower spirit to its home are the moments I think he is acting in line with the person he genuinely wants to be outside of any expectations of what he thinks he’s good at or what he’s “supposed” to be, or in terms of obligations in trying to impress someone or doing what he thinks is expected of him… He just does these things instinctively, because I think fundamentally he’s a loving person who essentially just wants to be loved back.

These moments are especially important to highlight I think, because in these moments Guts has no external motivating factors. He is a child who loves his mother, who wants to reassure her and be reassured in turn; he is a young man who wants to repay an act of kindness out of genuine good heartedness.

I will submit also the following, as a pretty clear crystallization of what Guts is about:

(Chapter 33, “One Snowy Night”)

If he ended up sacrificing his life for Griffith at the story’s conclusion, it would be exactly in line with this same impulse: to love and be loved. This is what has always, at least imo, defined Guts beneath all the shame, and rage, and guilt, and shackles of duty, and his feelings of inadequacy.

In becoming Griffith’s shield, he wouldn’t be protecting him through his sword, he would be saving him through an act of love.

~~

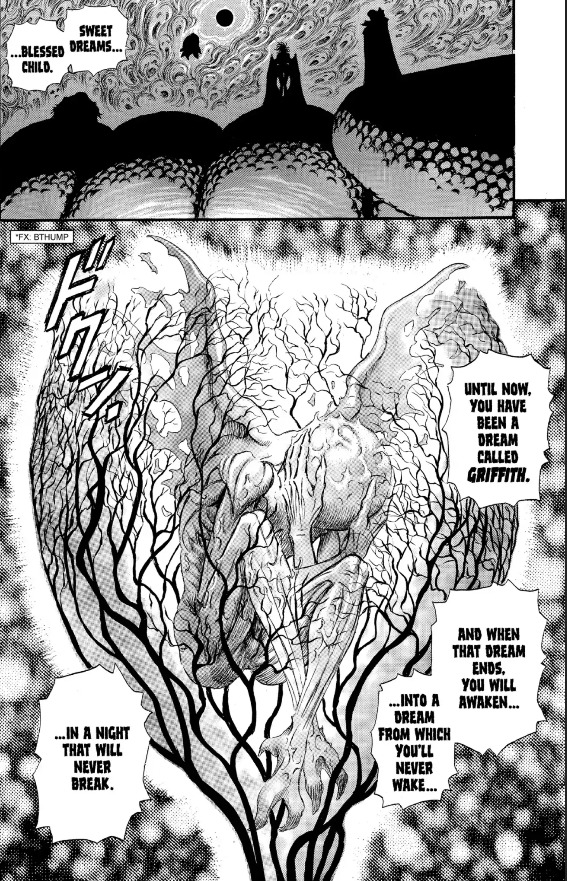

And OK, what I see as the smoking gun for this weird little theory comes from this very innocuous page from a random, seemingly unrelated story thread and chapter.

(Chapter 206, “Troll Raid”)

This page is framed in such an aesthetically significant way – a full page spread given to such a small line, like why unless it’s about more than some random townspeople.

The key that saves us lies in those we are trying to forget.

Guts has been trying to forget Griffith, to move on, for basically half of the story – this line very easily could be read as directly commenting on Guts’ journey and his inability to unburden himself.

BUT this line goes further – it’s not only suggesting that Guts trying to forget his past is not a good thing, it’s also suggesting that Guts needs to be saved somehow, and that it can happen through the one he’s “trying to forget.”

What does Guts need to be saved from? Well, from the burden of The Struggle, from berserking, from his sword, his regret, his hatred. And how can he do this through Griffith? By giving his love/life to him, as a shield instead of as a sword… It’s just too perfect!@!

So yeah, while this is all entirely wishful thinking, I also don’t think Guts sacrificing his life for Griffith is totally unreasonable or “out there” spec – I do legitimately see this as a once-possible and honestly pretty perfect ending to the story. So that’s what I’m fucking going with, goddammit.

Part 4, Conclusions

Imo Guts making a sacrifice for Griffith would be the most important theme Berserk could ultimately endorse – because, in my reading at least, Griffith has entirely defined his choices around the belief that he does not deserve absolution (reminder: I think he ultimately made the sacrifice because the Godhand convinced him there was no coming back from what he already was, and so as a result he doubles down on that belief by agreeing to the sacrifice). For someone who believes that he isn’t worthy of love to be loved nonetheless, outside of those cycles of worth, exchange, and self loathing that he is so bound within, that would be a pretty damn powerful message. And for a character who is defined by his trauma to decide that love is ultimately more important? That's what I want from this story.

And as I noted above, on a character level, I can absolutely buy that Guts would make a sacrifice for Griffith, because I read this as being in line with Guts’s most fundamental desires as a person, and because I think Guts feels personally responsible for what happened to Griffith and still desperately wants to right that wrong, he just doesn’t know how to do so.

However, on a broader narrative level, I think this is more difficult to make a case for because to a lot of readers Griffith seems beyond redemption.

And honestly I think if Miura had wanted to do a classic redemption arc, where Griffith comes to realize that he regrets his original decision to make the sacrifice (as in a reading where he chose the dream and has now come to be dissatisfied with his current situation), this arc would have started long ago and it would have been made abundantly clear to readers.

If Miura had been gearing up for Griffith to come to realize that he did the wrong thing and eventually at the end of the story planned to have him take another action on Guts’s behalf to redeem himself, I think for a turn like this to work effectively, his emotional state wouldn’t still be so ambiguous to us – Miura would have been showing us his incremental but explicit realizations that this is not in fact what he wants in order to get us to root for his redemption. If Miura was in fact headed in that direction, it just seems like it was too little too late at this point.

OTOH, though, if Griffith already knows what he did was wrong, as with my reading, then the thing he needs to come to understand in order to be redeemed isn’t that he made the wrong choice, it’s that he doesn’t have to hate himself. And for that, he needs to be told that he is loveable, and indeed, is and was loved even at his most despicable. It’s Guts’s love he needs, narratively and emotionally, and such a realization could come right at the very end of the story, no build up on Griff’s end necessary.

To put this in slightly different terms, Griffith’s redemption involves him coming to realize that the sacrifice was the wrong choice, but not because he realizes he never actually wanted the dream after all, but because he comes to realize that he never had to punish and hate himself for all his prior actions, because he was loved all along – that his sacrifice/act of suicide was wrong because it was never “necessary” in the first place.

Basically, whether he’s chosen the dream or the sacrifice yields different stakes for Griffith’s redemption – they hinge on fundamentally different things, and I don’t buy that the first one was possible given post-GA characterizations, but the second seems not only possible but necessary to bring this interpretation of the story to a satisfying resolution.

And I think there are different scales of redemption that are possible to admit here. But I do think both Guts and Griffith need some sort of redemption for the story overall to be satisfying – they’ve both done atrocious things, but the story has also expressly shown us that neither of them are a lost cause.

Both are still fundamentally broken, vulnerable, and fragile people; especially because both still need each other, after all, they’re both still in love with each other. This isn’t the characterization of people who are fundamentally beyond some kind of redemptive final act(s). It also helps that Griffith is basically treated as a deuteragonist post-Conviction Arc.

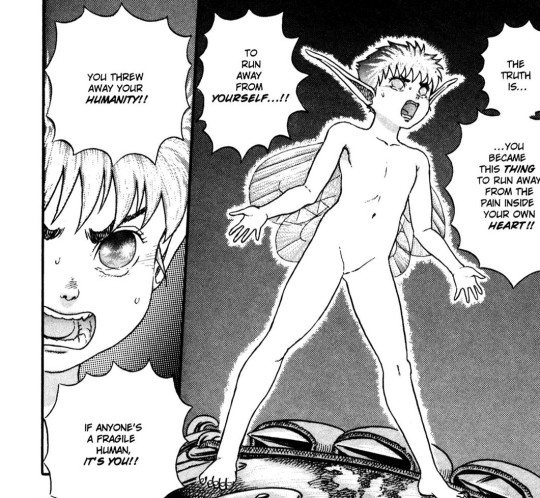

And ultimately I think Miura has shown us that this is a state that the apostles/“monsters” of the story all have in common. I’m thinking here of this moment we see at the very beginning of the story:

(Chapter 4, “Guardians of Desire”)

As Puck says here, apostles are very much still fragile humans. The most fragile, in fact. Their deformed bodies are proof of their having broken themselves. The clearest demonstration of this is of course Griffith, who as an apostle became what he always hated. These are “fallen” people, unloved, hiding from themselves and from the world. If that’s not someone who is in need of mercy and redemption, I don’t know who is.

As to whether both Guts and Griffith still need to “pay,” narratively and morally, for their actions, this is not something I have a strong personal opinion about – I think both of them have already suffered hugely. That being said, I do think a second sacrifice narratively should lead to both of their deaths at the end of the story. That’s for two reasons, one because I think they both would both probably view death as a release more than anything, and two because it would function as the narrative consequence for their actions, especially if they were to get taken out by Apostle!Casca, who has also suffered hugely at the hands of both of these men.

Death would be what finally frees both Guts and Griffith from their pretty fucking miserable/doomed lives and would finally provide them some kind of peace as well as self-actualization – in that sense Casca’s actions could be read in the mode of both mercy and vengeance. So that’s why I lean in that direction, but then again I’ve always been more interested in mercy/forgiveness/redemption as story tropes than revenge/punishment, though I think the story was set up to be able to balance both in a really interesting way.

Anyway, I hope you enjoyed my senseless ramblings. If I had my druthers this is how the story would have ended, and I guess it gets to live in my headcanon forever, and maybe yours too if you like my interpretation of the story.

Sorry for any of you who were waiting for another post from me – the news of Miura’s death really kept me from thinking about Berserk for a while, for obvious reasons. But the story is what we make of it, especially now, so I hope this maybe gave you a bit of solace too.

As always, feedback, discussion, etc. is welcome.

#since it's all fanon now i figured why not throw my hat in the ring#yes im hating the continuation series#also I've been sitting on this post for literal years#how did that happen seriously wtf#this post has been about gay stuff#as per usual#berserk#berserkmeta#berserk meta#griffith#griffith meta#and even some#guts meta#!!!#im really branching out

130 notes

·

View notes

Note

Domestic violence TW // I read that one Japanese account said that Miura experienced domestic violence growing up by the hands of his religious father, and that it reflected in characters like Jill.

Yes. There's a lot about that if you poke around, but essentially his father was very abusive and mentally unstable for much of his childhood and then stabilized after becoming very religious. He said something to the effect of, then it was calmer but full of religion.

He talked about one specific incident where his father destroyed their television with a hammer while saying not to watch television and then bought a new one a week later and claimed to have never done/said that. Also, something about his sister self-harming. This is all, I believe, from a 30-page long interview he did back in 2000 in a journal about gender/sexuality studies and shojo manga.

Honestly, it feels a little strange to talk about, but I guess it is out there, so. I'll say this: I did admittedly wonder about his background re: abuse because the way he portrays trauma was extremely... accurate and also sort of consistent, e.g. all the fathers tend to be awful (Gambino, Jill and Rosine's fathers, the King) and when the mothers are present they tend to be kind of long-suffering and desperate.

This is something that really stood out for me with Jill, for example, because of the way the story ends - with Guts leaving Jill to return to her abusive family and Jill basically determined to face that reality albeit with greater strength than she previously had. Because I guess the fantasy is that she would escape and be happy, but the actual ending of the story is, while kind of a big OUCH, more reflective of reality for children in that situation much of the time. And he always seemed to want to stay honest to reality even if he did so while still trying to infuse hope into these dark or bittersweet outcomes.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tagged by @marley-manson!

What year did you get into Berserk?

I am bad at the passage of time, but a few years ago.

Did you watch the anime or read the manga first?

I watched the 1997 anime, then the 2012 films, then read the manga (I bought volumes up tooo... I think just past the eclipse).

Who’s your favorite character and why?

Guts. He's a character type that really gets me when it gets me, a traumatised, angry man, with a stoic outlook and a penchant for destruction/self-destruction when he's at his peak of pain. I just love him-- there's something about the scene where he's dying and surrounded by wolves but he decides to live anyway. He faces the absurd (living when life has no ultimate meaning) and continues. He doesn't know WHY he wants to live but he lives searching for a reason, his own reason, to continue (he chooses Griffith then wrongly chooses to leave him again, then realises that far too late-- we also love a tragedy okay). Guts embodies something pretty philosophical for me. But also big violent traumatised man desperately loyal to (and in love with/desperate to be loved by) another man make brain go brrrrrrr.

I honestly think I have a lot in common with the average straight cis-male Guts enjoyer, except I think he's also Gay for Griffith (because he is).

Do you have a favorite story arc?

Can only be The Golden Age. It’s the most beloved for a good reason. <- It's a perfect arc.

What are your top 3 ships?

Guts/Griffith is probably the only one I actually care about, ha.

Who’s your favorite apostle?

I don't think I read far enough to have gotten to the more interesting ones?

Is there a character you’d know that you’d be friends with?

I think most of the Band of the Hawk seems pretty genuinely like they'd be good friends-- so probably the general group of like Judeu, Casca, etc. etc.

Who’s your favorite God Hand?

I mean if you're counting Femto it has to be Femto.

You’re allowed to bring one character back from the dead. Who are you bringing back?

From the previous answer by @marley-manson: I’m gonna say Rosine. She should’ve lived and ran away with Jill. <- that's about where I stopped reading and this is totally correct. That little arc was very good but also made me >:(.

Tagging: anyone who follows me who's into Berserk because I wanna know!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isidro brings out the worst in Berserk (or, me going on a long, dumb tangent like the old days)

Tis’ time.

I was watching The Kavernacle’s recent upload about how a lot of anime capitalizes on this weird fetishization of women and girls - which is for the most part true and is why I personally try to stay clear of a lot of anime. Honestly, any anime that focuses way too much on the “Japanese school girl” archetype and anime that depict nearly all female characters as though they’re still in the adolescent stage either behavior-wise or “phenotypically” (like that moe shit) kind of weirds me out.

Berserk has kind of stayed away from this, but it seems like it teeters on that because so many of the female characters in the series are under the age of 20. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that but I noticed in the chapters where the Guts’ party first arrived on Elfhelm, the character designs were on the borderline of giving characters that round cherubic type face, but especially with the female characters. In the recently chapters (From the last two years) Miura seems to have chiseled the style again, which is more preferable IMHO.

But I think this kind of tangles into some wider problems I find with some character designs. If people remember me and my content, probably my biggest gripe with Berserk as a series was its usage of sexual violence toward women. It still bugs me but I can give Miura credit in that he seems to have teetered away from using it so exploitatively. THAT SAID, I think as an older fan (and an older person altogether) I think a bigger overarching issue with Berserk is that Miura was never really that good at creating female characters.

(I can have so many interesting opinions now that I don’t care about making friends within this fandom)

No I’m not saying people shouldn’t draw any adult female character with more youthful features (I mean, as some who is at that age where I experience ageism, a lot of people - particularly men - believe that as soon as a woman hits 25 they’re suppose to shrivel up??? 🤨) just -

DON’T KNOW WHY A LOT OF (MALE) CREATORS DON’T UNDERSTAND THAT WOMEN CAN HAVE DIVERSE FEATURES AND DIVERSE PERSONALITY TYPES.

I think that diatribe is for another day (I know I’ve been explaining this to other people on my other social media during my Tumblr hiatus). But to condense what I’m saying, I notice that there isn’t a lot of age diversity of female characters: most of the female characters are in adolescent. Now, I don’t think it was a big issue in early Berserk because - and even though I still take some issue with how over-exploitation was handled - we still got to explore these young girls as characters whether it were girls like Casca, Theresia, Rosine(Rosalind), Jill, or even Erica and we’re meant empathize with the cruelty (or potential cruelty in the case of Erica) that the world dished out to them. Even with Luca and her gang we got explore the concept of sisterhood if just for a bit.

Now there’s less of that - WHICH CAN BE A GOOD THING because not every female character’s traumatic origin has to be rooted in a gender-based violence backstory. I like having Schierke not having a clear backstory and being “wise beyond her years” and we can just keep it that way. Only problem is that I see a lot more that weird lol!con humor when it comes to her - especially with her relationship with Guts.

I’m thinking of the excuse they use in hentai where, “the young prepubescent girl character is really a 7000 year old demon-lord from another dimension - so it’s not really p*doph!l!a.” Schierke is way mature for her own age, so she’s practically an adult. 😒

This isn’t just an issue with Schierke. Like, I notice a lot of up-skirt shots with these newer young girl characters; with Isma it’s kind of worse because she also embodies that “too naïve to know that she’s a turn on” when she’s like what? Thirteen? Fourteen?? I guess we’re also given the excuse that a lot of these characters are magical/supernatural/near-human so you can away with a lot more. Now that they’re on Elfhelm and there is a litany of these female characters we just have a bunch of the fantasy-universe version of the Japanese school girl shit, where we enter -

Ugh. Isidro.

I wasn’t too fond of him the beginning but I could appreciate his place a little. But his introduction was the point where we we start to see more of that typical dumb, pervy schoolboy humor in the series. I get it: Isidro is a teenage boy.

So was Guts.

And Griffith.

And Rickert.

And it’s just as important to have a diversity of young boy characters as well, but it’s just that for the amount of spotlight Isidro is given, not much of it is meaningful, especially in recent chapters. If anything his character is devolving IMO. MAYBE it’s some weird affect that Elfhelm has on him and other characters that is yet to be explored, but I somehow doubt it. Maybe it’s a phase that’ll be gone soon. I dunno.

Maybe just overall the time spent on Elfhelm isn’t being spent as productively as I had hoped for. I mean BY NO MEANS AM I OVERLOOKING THE FACT THAT AFTER OVER 20 YEAR OF WAITING CASCA IS FINALLY CURED WHICH IS BY FAR THE BIGGEST ACCOMPLISHMENT IN THIS SERIES EVER but I think with so much anticipation of what comes next for her and Guts it’s frustrating to see other side stories that aren’t focused on their to reconciliation spent so frivolously. We got a bit with Guts and the Berserker armor; we got a bit with Schierke and her training; we got a bit with Farnese and her training; we got a bit with Casca retraining her self and her trauma.

See what I’m getting at a bit? We’re just getting bits and shit, it seems. No streamline story arc. We get introduced to one bit and then POP where at some other point with some other character. I get that things are a bit different in this setting because this is the first time in a long while that Guts, Casca and their company are actually physically safe from the affects of the formers’ brands. I with so much rest and recreation time I WANT there to be more retrospective time as well.

I’ve said elsewhere that I’m super duper disappointed with how Puck has gone downhill, especially in regard to he and Guts’ relationship. We haven’t gotten any sort of meaningful interaction with him since Isidro came into the story. AND EVEN BETWEEN THE TWO OF THEM IT’S MORE OR LESS MEANINGLESS FRIVOLITY. Couldn’t Puck and Isidro be using their on-screen time more wisely, even if it has to be away from each other. What happened to Isidro wanting to be a bad-ass swordsman? Like, just being associated with two badass swordsmen (now that Casca is active again) is not a replacement for character/skill development. DO SOMETHING. BE INSPIRED OR SOME SHIT (INSTEAD OF LOOKING UP WITCH SKIRTS).

And what the hell is Serpico doing? And Roderick? And aren’t there like three or four other -

- OKAY this is what happens when have these big ass fantasy adventure parties where only a third of the occupants actually contribute shit of merit. That’s why the O.G. Band of the Hawk worked; I guess that’s neo Band of the Hawk technically works but I just don’t give a shit about them because #fuckgriffith.

GOD DAMMIT I JUST NEED THE STORY TO GET BACK TO THE HOLY TRIAD CHARACTERS ALREADY (GUTS-GRIFFITH-CASCA). PLEASE FOR THE LOVE OF GOD LET MOONLIGHT BOY BE A BRIDGE TO THAT HAPPENING SOON. щ(ಠ益ಠщ)

I think I have to stop here.

Don’t you miss this? Me starting on one note and ending on something completely different but universally important?)

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did Rosine have feelings for Jill?

Hello and thanks for the ask!HMMM I think Rosine did care for Jill a lot, because after all, they were childhood friends!

Even when Rosine appeared before Jill as apostle, she is very playful with Jill, placing a frog onto her head, showing that she is no threat to her. This looks a bit like Rosine did this often when they were playing together.

She’s also very affectionate! Even though this is definitely suggestively drawn, I’m not sure this interaction is 100% romantic, most of it actually seems sisterly to me. Like, I do get very touchy with my sisters, too, but then again, I won’t ever touch them in the same way as Rosine touches Jill here lol… I’m not sure if that makes sense.Though I suppose Rosine could be in the middle of exploring her sexuality, too.

Also: The theme in Lost Children is similar to Peter Pan: After all, there’s a dude accompanied by an ELF abducting children to neverland, to escape from the woes of the real world and he also has a romantic interest in one of the girls he’s taking with him (should sound familiar as hell to you)

I think it’s possible that Rosine’s affection and interest shown towards Jill is indeed romantic. Perhaps, it might be even an escape into romance from the loneliness of living alone in the misty valley with only slaves elves as friends. Who knows!

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

What Berserk and the Game of Thrones have in common? Both are the works where I had often found myself wondering "does author criticise violent misogyny he is portraying, or is the author himself misogynist who fetishises portrayals of rape?"... And Game of Thrones was a lot worse in that regard, in my opinion.

Well are we talking about Game of Thrones or Song of Ice and Fire because they are very different animals. GoT I think is pretty bad, while Song of Ice and Fire is very good. At first glance both works have a lot in common but upon closer examination they are actually very different. Berserk is dark fantasy while Song of Ice and Fire is Low Fantasy, Berserk is drawing on Romanticism and Nietzsche, while Song of Ice and Fire is drawing on humanism and the War of the Roses they are actually two very different works. In terms of their depiction of sexual violence and women, I think Song of ice and Fire does does much better in a few key ways.

1) Actual good female characters. Arya Stark, Sansa Stark, Cat Stark, Danny, Brienne, Cersei Lannister (its complicated), Melisandre, Olenna Tyrell, Osha, Asha Greyjoy

Even if you have more troubled characters like Arianne Martell, Lysa Arryn, or Shae, Ygritte, the good female characters not only outnumber the bad, they also are very different from each other. And the books try to make a point to remind the audience of the presence of female characters within the story even in small scenes.

Berserk meanwhile has probably only a few character (Schierke, rosine, Jill and Sonia) and maybe two more who are aren’t actively offensive (Isma, Luca, Erica, Nina, Fiona). And most of those good female characters only emerge later in the series. Meanwhile the vast majority of the female characters are really just embodiment of various sexist stereotypes.

2) A lot less rape. of those female characters I mentioned in Song of Ice and Fire, only two have even a hint of rape as a threat directed at them on screen. A few more are put into marriages of dubious consent but we also don’t see the sex On Screen.

There is a lot of mention of rape in Berserk happening to unnamed characters but this isn’t really shown directly we mostly see the after effects of it

Now in the show they increase this number for reasons....

Berserk meanwhile, has sexual violence very graphically directed at almost all of its female characters to some degree or another, Casca gets almost raped or threatened with rape 10 times not even counting the actual rape. And quite a few of those are quite graphically shown. And there is so much rape of unamed women shown in explicit detail throughout the comic.

3) Contextualization. Song of Ice of Fire does have its own issues with its depiction of sexual violence but there is much more a point with its use of it. Rape in Song of Ice and Fire mostly occur in the context of the dubious nature of medieval marriages, an extension of war, or as part of sexual slavery, with the point being the “normal’ of medieval life. Martin is talking about rape culture and the commodification of female bodies. Meanwhile with Berserk there are only two rapes that I would say are actually necessary to the story (Casca and Guts)

Now there are a lot of things Berserk does better than Song of Ice and Fire while Game of Thrones I would argue is actively bad compared to both.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don’t think the ending of lost children is saying that people like Jill should stay with their abusers or that it’s noble to suffer I think it’s just making the point that there isn’t a paradise where you will never suffer, as it seemed that Jill tried to leave with Guts as a form of escapism thinking her problems would disappear if she did, like rosine did with the sacrifice. Yeah it’s still not that great and it doesn’t reflect well on guts either when he could’ve just brought her to Godo and had him look after her or something. Though the narrative does frame it as though guts made the “right” choice, basically tough love and making her stronger or whatever. And there was the idea that the demons haunting him at nightfall would be too dangerous for her anyway.

Enh I'll admit that Jill's naivete is a detail that makes Jill's decision to stay work strictly on a character level. Sure, Jill is frightened off by ghosts and decides to stick with the devil she knows, I'll totally buy that.

But yeah like you go on to mention, the narrative framing it as the right choice is the real problem here for me. I doubt Miura intended to flat-out say that abused kids should just deal with it, but it's effectively what the narrative says consistently throughout the Lost Children arc, from putting the Peekaf 'you'll regret leaving home' story in the arc about child abuse to Rosine's regret and longing for home as she dies to Jill deciding it's best for her to stay with her abusive parents and just struggle and cry her way through it.

Also maybe worth noting that plot-wise Jill's decision doesn't actually fit the larger narrative of Berserk. This is probably accidental lol, due to being a serialized story, but think about it: she decides to stay with her family because it's dangerous elsewhere too. Well, what happens a year later when her village is leveled by dragons because Griffith genre shifted the story to high fantasy? It's a hell of a lot safer to be traveling with Guts than it is to be an ordinary villager during the Fantasia arc lol.

So yeah. ia that staying with her abusive family makes sense for Jill on a character level, but it's the way the themes of the Lost Children arc seem to support that decision that bothers me, and I don't think it really works on a plot level either, taking the later story into account.

Thanks for the ask!

#ask#anonymous#a#b#arc: c#character: jill#theme: abuse#i'd also argue that isidro traveling with guts weakens this too - sure he does get one lecture about how#leaving home isn't great but it hasn't come up again in the last like 200 chapters and he doesn't seem to regret running away#and he wasn't even running away from abuse as far as we know - just boredom#but you can also argue that isidro is more capable or braver than jill or w/e so i'm keeping this point in the tags lol

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

OPINION: Here's Why Berserk Is the Perfect Blend of Shonen and Shoujo

My tastes in media have shifted in all sorts of directions throughout the years, but there’s one constant: Berserk is still my favorite manga and my favorite work of fiction, period. It was an absolute game-changer for me when I first experienced Miura’s hellish fantasy in early high school. I was amazed to see a manga that amalgamated so many appealing and variegated concepts, emotions, and aesthetic elements into one cohesive package. Miura’s world was not only frightening, but also beautiful, and even in my adolescent opinion, I thought it had the most painstakingly gorgeous hand-drawn illustrations I had ever seen. I was shocked a dark fantasy existed that blended the best of shounen and seinen, with the emotional depth and character development more native to shoujo.

In recent times, I found out my personal interpretation of Berserk might be more factually on point than I realized. Kentaro Miura, the creator, remarked in one of a Crunchyroll interview that Fist of the North Star greatly influenced Berserk. Miura also mentioned in the official Berserk Official Guidebook that the character Serpico was meant to mirror Andre from the acclaimed European-inspired shoujo Rose of Versailles. To celebrate the anniversary of the Berserk manga, I’ll explore how the depressingly overlooked Lost Children Arc — in particular, volumes 14-16 — embodies Miura’s unique mesh of the best of both shounen and shoujo, resulting in an entirely original and moving narrative. Because of this, Berserk is rightfully branded (pun intended, tee-hee) as a monolithic manga masterpiece for the ages. Read on for more.

Image via Dark Horse Comics

The Lost Children Arc is, in my opinion, the most underrated of all Berserk arcs. The short saga rarely gets discussed in online circles and has been skipped in both anime and game incarnations of the series (even in the most recent musou-style PS4 Berserk title). There are good reasons why, as the arc features some very graphic depictions of abuse and violence toward children. Despite its sensitive and graphic nature, the Lost Children Arc provides very cautionary insights about the cyclical nature/consequences of abuse toward kids. Miura is at his most compassionate here, encouraging readers to look at the ugliness of life straight in the eye while simultaneously showing the beauty of humanity’s indomitable will to survive.

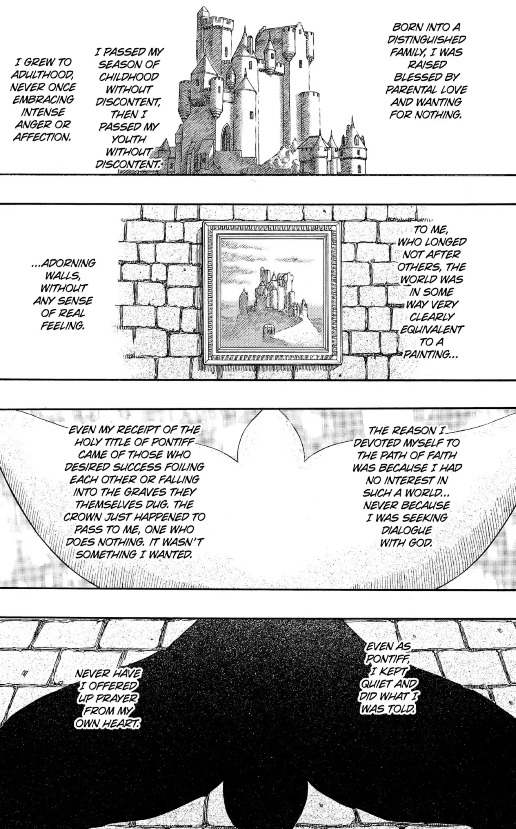

Berserk's central character, Guts, meets Jill — a young girl and the protagonist of the arc — in a manner somewhat similar to the first meeting between Kenshiro and Rin in Fist of the North Star: The Movie. Guts saves Jill from a cruel group of men who kidnapped her, just as Kenshiro saves Rin from, well, a cruel group of violent men too. Guts goes to Jill’s hometown, which is plagued by demonic elves who eat humans and steal the children in the village. The central antagonist is Rosine, an Apostle who sacrificed the lives of her parents in order to obtain demonic powers, and who turns stolen children into murderous elves. Rosine and Jill were the closest of friends growing up, and both experienced the same level of abuse from their respective fathers. These two abusive father figures exemplify the unique way Berserk departs from shounen like Fist of the North Star.

Berserk borrows FotNS's depiction of the dreary lives led by many of the average inhabitants of its bleak universe. But whereas FotNS almost always portrays the average person/family of the post-apocalyptic world within a positive light, Berserk offers no easy dichotomy. Outside of the main characters and villains, FotNS is a roughly binary world split between the muscular roaming murderers and the hapless, regular people trying to survive their grim existence. Berserk injects a much starker component by locating the grisly realities of household abuse, refusing to portray the average family as uniformly faultless, saintly individuals. Jill’s father is an embittered alcoholic who abuses both his wife and daughter, and Rosine’s father does the same to her. Miura’s Berserk, unlike FotNS, is a disturbing — yet sadly realistic — world where even average individuals embody the same cruelty of their environment, where horror is focalized within the everyday, as well. Showing that disenfranchised, suffering individuals are capable of continuing cycles of abuse gives Berserk a nuanced edge that sets it apart from other shounen/seinen.

Image via Dark Horse Comics

In a more overt way, the Lost Children Arc further drives home its realist message via heavily deconstructed fantasy shoujo tropes that contrast from the norm. In a show like Sailor Moon, for example, Usagi and the Sailor Guardians must transform into their magical forms, and use their magical powers to fend off demons and save their loved ones along with the Earth. Their "regular" day-to-day human selves are not enough to defeat the evil beings and trials they face. Though it’s debatable, as I could see someone referencing love and friendship as the "true" means of triumph in Sailor Moon, I see its fantastical elements as the primary vehicles through which salvation, unity, and victory is achieved.

In contrast, Berserk does the inverse and uses escapist fantasy elements and magical powers to express a disturbing, sobering message. In one sequence, Jill is horrified that the demon elves actually kill each other in their mock warfare activities, and Rosine tells her they’re simply "playing human" in those games. Here, Miura uses the fantastical, mystical environment of Rosine and her misty valley to reenact and highlight the gruesome realities of human cruelty. In this way, fantasy is a vehicle to point toward the grim, bare facts of human reality, rather than the typical usage of fantasy as an escape from the hard truths of our existence. However, even though Miura uses Rosine’s fantastical powers as a means to communicate the ugliness of human behavior, he simultaneously adds a sympathetic layer to her character that expresses a deeply compassionate look at how enduring exploitation can easily reproduce horror and suffering.

The maltreatment and alienation that led Rosine to sacrifice her parents and become a terrifying demonic being feel very understandable given the circumstances of her life. Although Rosine’s actions are utterly indefensible, the manga still invites a somewhat compassionate reading of her character. It’s hard not to feel some degree of empathy for Rosine, a young girl who simply longed to live in a better world where adults did not beat her and make others suffer needlessly. Gaining power with the Behelit was an anguished cry from her inconsolable heart that understandably — though not justifiably — rejected the endless harshities of life.

Finally, Miura creates further sympathetic nuance around this unique take on fantasy the moment Rosine dies. Rosine personally identified with a fairytale about a lonely outcast child named Peekaf and expressed deep sorrow that she found no elves when she visited the Misty Valley. Puck — the Elf that follows Guts and provides much-needed comedic relief throughout all of Berserk — reveals that Elves likely did live in the Misty Valley, and his very existence proves the meaning of the story of tragic Peekaf. Rosine experiences a brief blip of comfort in her last moments as she tearfully realizes the fantasy story she clung to for dear life was not entirely false or meaningless. Here Miura adds another layer of complexity by reminding us that make-believe has traces of important truths, and those fantastical narratives can still help us even if the reality of life isn’t as bright or as happy as we hoped.

Image via Dark Horse Comics