#A statue of Emmett Till is unveiled in Mississippi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A statue of Emmett Till is unveiled in Mississippi : NPR

Emmett Till's statue reflects the afternoon sun, during its unveiling on Friday in Greenwood, Miss.

Rogelio V. Solis/AP

GREENWOOD, Miss. — Hundreds of people applauded �� and some wiped away tears — as a Mississippi community unveiled a larger-than-life statue of Emmett Till on Friday, not far from where white men kidnapped and killed the Black teenager over accusations he had flirted with a white woman in a country store.

"Change has come, and it will continue to happen," Madison Harper, a senior at Leflore County High School, told a racially diverse audience at the statue's dedication. "Decades ago, our parents and grandparents could not envision that a moment like today would transpire."

The 1955 lynching became a catalyst for the civil rights movement. Till's mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, insisted on an open-casket funeral in Chicago so the world could see the horrors inflicted on her 14-year-old son. Jet magazine published photos of his mutilated body, which was pulled from the Tallahatchie River in Mississippi.

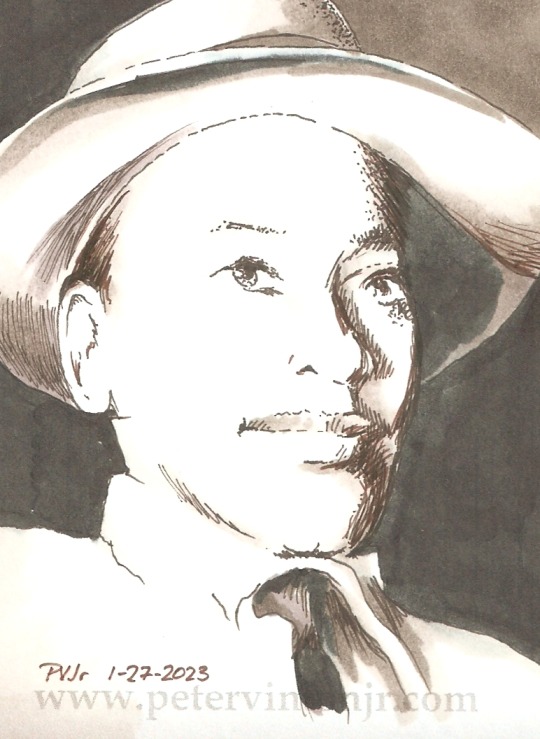

The 9-foot (2.7-meter) tall bronze statue in Greenwood's Rail Spike Park is a jaunty depiction of the living Till in slacks, dress shirt and tie with one hand on the brim of a hat.

The rhythm and blues song, "Wake Up, Everybody" played as workers pulled a tarp off the figure. Dozens of people surged forward, shooting photos and video on cellphones.

Anna-Maria Webster of Rochester, New York, had tears running down her face.

"It's beautiful to be here," said Webster, attending the ceremony on a sunny afternoon during a visit with Mississippi relatives. Speaking of Till's mother she said: "Just to imagine the torment she went through — all over a lie."

This undated portrait shows Emmett Louis Till, who was kidnapped, tortured and killed in the Mississippi Delta in August 1955 after witnesses said he whistled at a white woman working in a store. AP Photo/AP hide caption

"But you, know, change has a way of becoming slower and slower," said Thompson, the only Black member of Mississippi's current congressional delegation. "What we have to do in dedicating this monument to Emmett Till is recommit ourselves to the spirit of making a difference in our community."

The statue is a short drive from an elaborate Confederate monument outside the Leflore County Courthouse and about 10 miles (16 kilometers) from the crumbling remains of the store, Bryant's Grocery & Meat Market, in Money.

The statue's unveiling coincided with the release this month of "Till," a movie exploring Till-Mobley's private trauma over her son's death and her transformation into a civil rights activist.

The Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr., the last living witness to his cousin's kidnapping, wasn't able to travel from Illinois for Friday's dedication. But he told The Associated Press on Wednesday: "We just thank God someone is keeping his name out there."

He said some wrongly thought Till got what he deserved for breaking the taboo of flirting with a white woman, adding many people didn't want to talk about the case for decades.

"Now there's interest in it, and that's a godsend," Parker said. "You know what his mother said: 'I hope he didn't die in vain.'"

Greenwood and Leflore County are both more than 70% Black and officials have worked for years to bring the Till statue to reality. Democratic state Sen. David Jordan of Greenwood secured $150,000 in state funding and a Utah artist, Matt Glenn, was commissioned to create the statue.

Jordan said he hopes it will draw tourists to learn more about the area's history. "Hopefully, it will bring all of us together," he said.

Till and Parker had traveled from Chicago to spend the summer of 1955 with relatives in the deeply segregated Mississippi Delta. On Aug. 24, the two teens took a short trip with other young people to the store in Money. Parker said he heard Till whistle at shopkeeper Carolyn Bryant.

Four days later, Till was abducted in the middle of the night from his uncle's home. The kidnappers tortured and shot him, weighted his body down with a cotton gin fan and dumped him into the river.

Jordan, who is Black, was a college student in 1955 when he drove to the Tallahatchie County Courthouse in Sumner to watch the murder trial of two white men charged with killing Till — Carolyn's husband Roy Bryant and his half brother, J.W. Milam.

An all-white, all-male jury acquitted the two men, who later confessed to Look magazine that they killed Till.

Nobody has ever been convicted in the lynching. The U.S. Justice Department has opened multiple investigations starting in 2004 after receiving inquiries about whether charges could be brought against anyone still living.

In 2007, a Mississippi prosecutor presented evidence to a grand jury of Black and white Leflore County residents after investigators spent three years re-examining the killing. The grand jury declined to issue indictments.

The Justice Department reopened an investigation in 2018 after a 2017 book quoted Carolyn Bryant — now remarried and named Carolyn Bryant Donham — saying she lied when she claimed Till grabbed her, whistled and made sexual advances. Relatives have publicly denied Donham, who is in her 80s, recanted her allegations. The department closed that investigation in late 2021 without bringing charges.

This year, a group searching the Leflore County Courthouse basement found an unserved 1955 arrest warrant for "Mrs. Roy Bryant." In August, another Mississippi grand jury found insufficient evidence to indict Donham, causing consternation for Till relatives and activists.

Although Mississippi has dozens of Confederate monuments, some have been moved in recent years, including one relocated in 2020 from the University of Mississippi campus to a cemetery where Confederate soldiers are buried.

The state has a few monuments to Black historical figures, including one honoring civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer in Ruleville.

A historical marker outside Bryant's Grocery has been knocked down and vandalized. Another marker near where Till's body was pulled from the Tallahatchie River has been vandalized and shot. The Till statue in Greenwood will be watched by security cameras.

Jordan won applause when he said Friday: "If some idiot tears it down, we're going to put it right back up."

#A statue of Emmett Till is unveiled in Mississippi#emmett till#emmett till statue#mississippi#civil rights activists

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"That is, after all, how it works. We don't come here with hatred in our hearts. We have to be taught to feel that way. We have to want to be that way, to please the people who teach us to want to be like them. Strange, to think that people might learn to hate as a way of getting some approval, some acceptance, some love. I thought about all that."

Double biography today. And even a cursory glance at this weekend's headlines will make fairly obvious why I chose to talk about these two people.

Born in 1941 Chicago, Emmett Till was 14 years old when, on August 24, 1955, he was kidnapped and tortured to death by a white mob in Money, Mississippi for the never-proven "crime" of flirting with a white woman. His mutilated body was retrieved from the Tallahatchie River three days later. His mother, Mamie Till-Bradley, made the agonizing decision for her son's bloated, mutilated body to be displayed in an open casket funeral at Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ, in Chicago. Thousands of people lined up to view the body and more than 50,000 mourners attended the funeral service. The resultant media coverage threw a spotlight on extrajudicial lynchings in the U.S., and forced a greater public discourse on segregation, racial violence, and systemic inequality.

In September of that year Till's accused murderers were ultimately acquitted by an all-white, all-male jury after only 67 minutes' deliberation. Four months later the accused murderers openly admitted to the crime to journalist William Bradford Huie, in an article that would then appear in the Jan. 24, 1956 edition of Look magazine. This article's publication was in many respects a clarion call to justice for many grassroots and local activists, kickstarting the Modern Civil Rights Movement.

Mamie Till-Bradley continued to advocate for social and racial justice for the rest of her life, never passing up an opportunity to educate about the circumstances of her son's murder right on up until her death in 2003. While Till's story remains a part of the American public consciousness (even directly informing the underlying plot of Harper Lee's To Kill A Mockingbird), the details tend to become lost to time --glossed over, sanitized. Of late this has been notably mitigated, with 2022's airing of the miniseries Women of the Movement on ABC, featuring Adrienne Warren as Mamie Till-Bradley. In March of 2022, President Joe Biden signed into law the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, and this past October the feature film Till premiered in theaters, directed by Chinonye Chukwu and starring Danielle Deadwyler as Mamie Till-Bradley. One attendee at the notorious 1955 trial was future State Sen. David Jordan (D-Greenwood), who successfully sponsored the commissioning of a bronze statue of Emmett Till, unveiled in October of 2022 at Rail Spike Park.

(Read "What Emmett Till's Mother Taught Me About Grief and Justice" by Sybrina Fulton, mother of Trayvon Martin.)

Bottom line here: Emmett Till's story has pointedly NOT vanished into invisibility and obscurity, unlike a great many other lynchings and massacres. But the larger issue is more primal: Emmett Till should still be alive, today --he should be comfortably just into his eighties, possibly enjoying the company of grandchildren. And to pull that very same thread, Amadou Diallo should still be alive; Trayvon Martin should still be alive; Breonna Taylor should still be alive --they should all be into their late-twenties, possibly settling into a career, perhaps starting families of their own.

Tyre Nichols should still be alive.

Incidentally, these biographies all now have a permanent home, rather than subject themselves to arbitrary throttling-down at the murky whims of various social media. Safer and more sensible that way, especially since so many states (mine included, unfortunately) have redoubled their efforts to ensure that this subject matter stays out of school curricula. New to this series? Go here to start the lessons: http://www.petervintonjr.com/blm/start.html

Black History Month kicking off in a few more days, my friends. More biographies and accompanying art, still to come. I feel as though I keep repeating this, but: we've a lot still to learn. So go study.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mississippi Unveils Emmett Till Statue Near Where White Men Kidnapped And Killed Till Decades Earlier

Hundreds of people applauded — and some wiped away tears — as a Mississippi community unveiled a larger-than-life statue of Emmett Till on Friday, not far from where white men kidnapped and killed the Black teenager over accusations he had flirted with a white woman in a country store.

“Change has come, and it will continue to happen,” Madison Harper, a senior at Leflore County High School, told a racially diverse audience at the statue’s dedication. “Decades ago, our parents and grandparents could not envision that a moment like today would transpire.”

The 1955 lynching became a catalyst for the civil rights movement. Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, insisted on an open-casket funeral in Chicago so the world could see the horrors inflicted on her 14-year-old son. Jet magazine published photos of his mutilated body, which was pulled from the Tallahatchie River in Mississippi.

The 9-foot (2.7-meter) tall bronze statue in Greenwood’s Rail Spike Park is a jaunty depiction of the living Till in slacks, dress shirt and tie with one hand on the brim of a hat.

The rhythm and blues song, “Wake Up, Everybody” played as workers pulled a tarp off the figure. Dozens of people surged forward, shooting photos and video on cellphones.

Anna-Maria Webster of Rochester, New York, had tears running down her face.

“It’s beautiful to be here,” said Webster, attending the ceremony on a sunny afternoon during a visit with Mississippi relatives. Speaking of Till’s mother she said: “Just to imagine the torment she went through — all over a lie.” -(source: nbc news)

DNA America

“it’s what we know, not what you want us to believe.”

#dna #dnaamerica #news #politics

0 notes

Link

A statue in honor of Emmett Till has been unveiled in Greenwood, Mississippi. Emmett Till’s story will forever be remembered and is a prominent chapter in American Black history. His life has continued to be honored; his Chicago home is now a national landmark and the white house finally signed an anti-lynching act. Now, 70 years later, Greenwood, Mississippi have decided to dedicate a statue to the young boy who was murdered for being falsely accused of 'whistling at a white woman.' Mayor Carolyn McAdams said she hopes this statue brings a change of attitude and tolerance within the community. Stating, “I hope it shows that we can’t change the past, but we can certainly do something about the future. And so I hope it shows that we are compassionate, we are caring, and this should never, ever happen again.” The $250,000, 9-foot tall bronze statue is located in Greenwood’s Rail Spike Park, not far from where the young boy was kidnapped after the false accusations. The statue depicts a young, joyful Till in slacks, a dress shirt, and a tie with one hand on the brim of a hat. “I want us to look right and left to each other and say we need to do better in the spirit of young Emmett, the spirit of this memorial,” said U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson, “We won’t let his death be in vain.” All members of the community came out to witn...

0 notes

Text

Emmett Till honored with 9-foot statue in Mississippi city where 1955 ..

Emmett Till honored with 9-foot statue in Mississippi city where 1955 .. A Mississippi community with an elaborate Confederate monument will unveil a larger-than-life statue of Emmett Till, not far from where white men kidnapped and killed the Black teenager over accusations that he flirted with a white woman in a country store... . . . . . . . .

0 notes

Text

Video Extra >>> Emmett Till statue unveiled in Mississippi

Video Extra >>> Emmett Till statue unveiled in Mississippi

Emmett Till statue unveiled in Mississippi Watch More Videos: Go to Video Links Category or Subscribe to the Black Truth News Youtube Page

youtube

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Community with Confederate monument gets Emmett Till statue

Community with Confederate monument gets Emmett Till statue

JACKSON, Miss. — A Mississippi community with an elaborate Confederate monument plans to unveil a larger-than-life statue of Emmett Till on Friday, decades after white men kidnapped and killed the Black teenager for whistling at a white woman in a country store. The 1955 lynching became a catalyst for the civil rights movement after Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, insisted on an open-casket…

View On WordPress

#Courts#Government and politics#Homicide#Human rights and civil liber#Judiciary#Law and order#Legal proceedings#Local courts#Local governments#Political activism#Political issues#Political movements#Social affairs#Social issues#Violent crime

0 notes

Link

Months removed from the height of nationwide street protests, the movement has arrived at an important juncture, where its next steps will determine its success.

Syreeta McFadden 7:00 AM ET

Direct action is never the primary component of a movement’s longevity; it is only a piece that works in concert with a multitude of efforts.Martin H. Simon / Redux

August 28 holds significant meaning for many African Americans. This year, it marked the 65th anniversary of the murder of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old Black boy who was lynched by two white men near Money, Mississippi. Till’s death served as one of the catalysts for the civil-rights movement, and organizers of the 1963 March on Washington—one of the largest mass demonstrations of the 20th century—selected this date for their gathering. This year was also the 57th anniversary of that march. Amid the coronavirus pandemic, the National Action Network organized thousands of people wearing masks to fill the Mall last Friday and commemorate the march’s legacy—and assert a new commitment to fighting injustice. It is not a coincidence that the Movement for Black Lives —a consortium of more than 50 Black-led organizations, including the Black Lives Matter Global Network—also hosted its virtual Black National Convention that Friday evening, where it unveiled its multipronged political agenda on matters of police brutality and beyond.

The momentum for cultural and political change stemming from the reemergence of Black Lives Matter demonstrations this summer has been extraordinary. Throughout communities across the country, portraits of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor are wheat-pasted on building walls. Signs that read black lives matter are posted in residential and storefront windows, and the words have been painted onto city streets. Statues that venerate racists, segregationists, and Confederates have come tumbling down. Brands and corporations have rushed to acknowledge systemic racism, ranging between strong and lukewarm commitments to addressing structural inequities. The Minneapolis City Council unanimously voted to dismantle its police department. And school districts in Oakland, California ~,~ and Madison, Wisconsin, announced plans to terminate their police contracts. But as the end of summer approaches, will this transformative energy last or languish?

Since the height of the protests in June, there’s been an absence of a meaningful nationwide embrace of police reforms. That month, President Donald Trump signed an executive order calling for the creation of a national database on police use of force, yet the measure fails to address broader issues related to policing. And while the aftermath of the Jacob Blake shooting by police in Kenosha, Wisconsin, may provide renewed pressure on state legislators to act, there’s no denying that the largest social movement of the 21st century has to enter a new chapter.

To that end, at Friday night’s convention, the Movement for Black Lives presented a robust 2020 platform, connecting the dots among issues of policing, reproductive justice, housing, climate change, immigration, and disabled and trans rights. In addition to outlining demands to “ end the war on Black people,” the platform urges the passage of the Breathe Act, federal legislation that would ensure the closure of Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention facilities, defund police departments, and reestablish social programs for the formerly incarcerated. The platform also calls for land reparations for Indigenous communities and Black farmers, electoral justice via the passage of the John Lewis Voting Rights Act, and the advocacy and protection of trans people. The convention was an energetic capstone to a summer of victories both significant and modest.

Still, direct action is never the primary component of a movement’s longevity; it is only a piece that works in concert with a multitude of efforts. Movements frequently face setbacks and fierce resistance, and some even wait decades to capture the national imagination. “When the cameras turn off, when there’s not as much attention to the issues in mass media or social media, we think that the movement activity has somehow ended,” Allen Kwabena Frimpong, a co-founder of the AdAstra Collective, an organization that supports and studies social movements, said in a recent interview. “But it hasn’t. It’s that what is required of us has shifted … in this phase of the cycle. It’s a time to build strategy.”

When Black Lives Matter protests first captured the nation’s attention and spread across American cities in the late summer of 2014, three high-profile police killings of Black people had occurred: John Crawford III in Ohio, Eric Garner in New York, and Michael Brown in Missouri. It was 18-year-old Brown’s shooting death by an officer in Ferguson that marked a tipping point in the movement: The nation saw several weeks of uprisings and sustained protests demanding policing reform and accountability. That energy was sustained in Chicago, New York, Baton Rouge, Dallas, Minneapolis, Milwaukee, Oakland, St. Louis, and others until 2016.

The street protests subsided with the advent of Trump’s presidency, but this did not mean that activism and organizing weren’t happening behind the scenes. The networks created by those protests nurtured the infrastructure necessary to seed engagement today. The Movement for Black Lives released a policy platform in 2016, pivoting toward increased influence in electoral politics, and advocating for economic justice, investment in education and health care, and reparations. And activists working in Ferguson launched Campaign Zero, a data-driven resource that drew attention to police-union contracts that make it impossible to discipline, investigate, or fire officers for repeated charges of misconduct. Organizers from these groups, along with those from the Black Lives Matter Global Network, have maintained a clarity of focus for years.

And it shows: In 2016, just 43 percent of Americans supported the Black Lives Matter movement. Four years later, the needle has moved significantly. A majority of Americans —and more than half of white people— support the protests as well as major reform in policing. Defunding police departments has been a long-held position by activists working toward outright abolition and the transformation of norms for enforcing public safety. In this moment, ideas that were once deemed too radical have meaningfully entered the mainstream discourse.

Perhaps the closest analogue for this present American moment is 1965, in Selma, Alabama—where protests led to a swift federal legislative response. After years of grassroots efforts and organizing to challenge local voting laws that barred Black Americans from the ballot box, national civil-rights leaders from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee started to align their efforts with Alabama activists. But it was the death of Jimmie Lee Jackson —a veteran and church deacon who was shot by a state trooper during a nighttime march on February 18—that accelerated the push for federal intervention. That’s when the idea to march 54 miles from Selma to Montgomery was born. (At one point, organizers considered carrying Jackson’s casket to the steps of the capitol to lay at the feet of Governor George Wallace.)

On March 7, 1965, known as Bloody Sunday, the nation witnessed the totalitarian brutality of the American South on live TV when state troopers advanced on some 600 protesters attempting to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Then-25-year-old John Lewis, the head of SNCC, was severely beaten and suffered a skull fracture; the troopers tear-gassed and battered other protesters on the bridge. From Atlanta, the head of the SCLC, Martin Luther King Jr., urged people from other states to come to Selma in solidarity, and by March 9, hundreds had answered the call. They attempted to cross the bridge again to march to Montgomery, but turned back to avoid another confrontation with the troopers. The strategy was employed to dramatize the unequal application of the law and to affirm the peaceful disobedience of this enterprise. Meanwhile, in Washington, D.C., as protests in support of the Alabama campaign went on outside the White House, a small group of young people staged a sit-in for almost seven hours—first in a main-floor corridor and later in the East Wing—after surreptitiously gaining entry through one of the building’s public guided tours.

Activists, bolstered by the national attention to the crisis in Selma, saw the swift materialization of those efforts at the federal level. On March 15, addressing a joint session of Congress, President Lyndon Johnson introduced voting-rights legislation. “Their cause must be our cause too,” Johnson said. “Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.” With the support of federal courts, activists and allies set out again for Montgomery, leaving Selma on March 21 and arriving at the capitol on March 25. That final Selma-to-Montgomery march, which culminated with 25,000 participants, was the embodiment of a victory soon to come: On August 6, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law.

The civil-rights movement was ultimately successful, yet it was also beset by ruthless obstruction. Prior to 1965, Selma activists, along with SNCC, orchestrated voter-registration efforts and sit-ins to protest segregation, and were met with fierce resistance from state and local authorities in concert with the White Citizens’ Council and the Ku Klux Klan. A 1964 court injunction forbidding gatherings of three or more people for the cause of civil rights also stymied momentum. It’s clear that social movements are endemic to American life: The constant presence of protests and activism has shaped culture and policy over the past 60 years. Yet the anticipation of delays and deterrence by oppositional forces is built into movement work. Key players have to continuously adapt their strategies and challenge resistance by powerful actors to achieve any movement’s goals.

Today, the Black Lives Matter movement is a decentralized, leaderful, interdependent network of organizations and individuals, channeling its resources toward building a society where Black people can flourish. Friday’s march and convention presented a myriad of committed activists working twin threads of direct-action protests and longer-term plans to dramatize the urgency of this crisis. Rooted in Black feminist thought, the convention demonstrated the capaciousness of this movement and highlighted efforts from large and small communities nationwide. Success for these activists and allies ranges from closing down a notorious jail to electing someone to Congress. As long as these efforts face a hostile Trump administration, though, the movement is likely to encounter many setbacks. Still, its holistic agenda—that all (cis/trans/queer/disabled) Black lives matter—is why the movement will last.

“Every Black person in the United States is gonna stand up,” Jacob Blake Sr., the father of Jacob Blake, told the crowd at Friday’s march. “We’re gonna hold court today. We’re gonna hold court on systematic racism … Guilty. Racism against all of us.” Widespread multicity street protests in the name of Blake and others may once again claim nationwide consciousness. But the unseen, deliberative work of activism will persist whether the cameras are on or off.

Black Lives Matter Just Entered Its Next Phase

0 notes

Text

Emmett Till statue unveiled in Mississippi

youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Community with Confederate monument gets Emmett Till statue

Community with Confederate monument gets Emmett Till statue

JACKSON, Miss. — A Mississippi community with an elaborate Confederate monument plans to unveil a larger-than-life statue of Emmett Till on Friday, decades after white men kidnapped and killed the Black teenager for whistling at a white woman in a country store. The 1955 lynching became a catalyst for the civil rights movement after Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, insisted on an open-casket…

View On WordPress

#Courts#Government and politics#Homicide#Human rights and civil liber#Judiciary#Law and order#Legal proceedings#Local courts#Local governments#Political activism#Political issues#Political movements#Social affairs#Social issues#Violent crime

0 notes