#A Hundred Stories of Military Valour

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

#ukiyo-e#Utagawa Kuniyoshi#歌川 国芳#Kiso Yoshinaka#japan#japanese#asia#木曽義仲#Buyu hyakuden#武勇百傳#A Hundred Stories of Military Valour#British Museum#Woodblock print#Edo Period

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shaman's Portal

Out in the Oklahoma Panhandle lies Beaver Dunes State Park, a recreational playground centered on hundreds of acres of gleaming silica sand dunes, where visitors can camp, hike, swim, and dune-buggy their way across the vast sandy hills. There's a reasonable entry fee, so the only real downside is the slight possibility of being captured through a mysterious human-snatching gateway.

It's called Shaman's Portal, said to have swallowed more than a handful of unsuspecting travelers and vacationers over the last few centuries. The exact spot where the disappearances have taken place has not been determined, but it's fair to say that, wherever it is, anyone's stumbled across it simply hasn't reported back.

If the accounts are to be believed, the first recorded occurrences date back to the sixteenth century when conquistador Francisco Vázquez de Coronado traipsed across the continent from Mexico, passing through Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas, looking for the famed Seven Cities of Gold. A friar on the expedition allegedly wrote in his journal about the loss of three men when camping near the dunes in Oklahoma.

It was the work of El Diablo. That night be the sandy hills we had been warned by the natives to avoid, we lost three able bodied men of valour: Juan Viscaino, Marco Romano, and Juan Munoz. They had been hunting game for the men when the three ill-fated men were taken from us in a lightning bolt of green.

The "lightning bolt of green" coincides with the bright-green flash of light more recent observers say accompanies a victim's abduction, an indication that the same phenomenon has endured for at least half a millennium.

In 1894, settler Nancy Wright is said to have vanished amid the dunes attempting to rendezvous with her lover. In 1977, Bill Gruendyke, a camper from Colorado, disappeared as well, leaving behind both his vehicle and campsite. The night before he vanished, locals reported seeing those telltale signs flashes of green radiance. One morning in 1997, a group of young campers from Kansas woke to discover one of their companions missing. Again, a fellow camper reported seeing the emerald light the night od the disappearance.

The source behind the phenomenon, often referred to as Oklahoma's Bermuda Triangle, is yet undermined, but there are several theories. Some believe it may be some kind of interdimensional portal focused on the infrequency trampled spot amid the dunes. At the other end of the theoretical spectrum is the idea that the disappearances are the result of boring old sinkholes. As for the flashes of green light, they may simply be discharges of static electricity; visitors to similar sand dunes regularly experience small shocks due to the friction of wind and sand grains.

The most popular theory, however, involves the existence of a UFO buried somewhere among the sand hills. A number of years ago, a group of relatives attending a family reunion claimed to have seen a crowd of military-looking personnel digging out-or possibly covering up-something alien, late at night within the park. The family was spotted by the uniformed men, who detained them for several hours and warned them not to talk about what they saw. Following up on the story, a researcher named Dr. Mark Thatcher investigated the area in the 1990s and hired a geologist to test soil samples. The two men found unusual levels of ionization and electromagnetic radiation, which the scientists equated to similar findings at both the legendary UFO crash site in Roswell, New Mexico, and the Bermuda Triangle. However, they too were approached by officials who produced government credentials-remember, it's a state-run park-and warned them to cease and desist, an admonition they evidently took them to heart. Dr. Thatcher has since fallen off the radar.

In an attempt to get to the bottom of the story once and for all, Tammy Wilson, founder of the paranormal research team Eerie Oklahoma, sent out some feelers in 2006 hoping to gather more information. In return, she was contacted via e-mail by an individual using the alias Davis Humes, who warned her not to visit Beaver Sands and to forget anything she knew. Humes listed a number of researchers, including Dr. Thatcher, who had disappeared as a result of their investigations, and advised Wilson that it would be in her best interest to move on, as well.

After several exchanges between Humes and Wilson, Humes claimed that it was all a hoax that he himself instigated in 1997 as a psychology experiment about the nature of urban legends and conspiracy theories. He said he abandoned the experiment long ago, but thanks to the Internet, the mystery of "Shaman's Portal" took on a new life of its own. Having received this admission by Humes, Tammy Wilson considered the matter closed.

The only question that remains, of course, is whether the confession was genuine or simply a last-ditch effort to head off further scrutiny by discrediting the legend as a simple practical joke.

0 notes

Photo

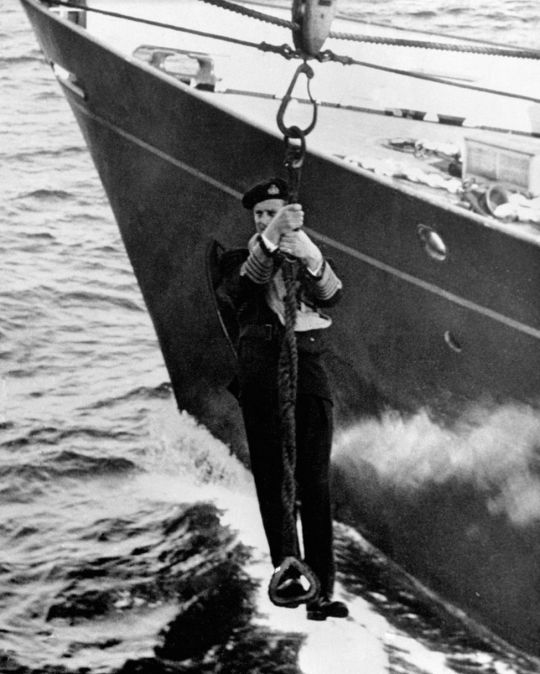

He was a servicemen at heart, he was good at it and he enjoyed it. There was no ego in the man. I think the Navy provided him with an anchor for life. He was always very proud in the uniform and his sense of duty and correctness dovetailed quite well when he married the princess.

- First Sea Lord Sir Jonathon Band, Royal Navy

Many military veterans and observers have privately said that the late Duke of Edinburgh could have become the First Sea Lord had he not married Princess Elizabeth, who assumed the throne following the death of her father, King George VI.

At the onset of World War Two, Philip started at the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth, where he would go on to be named “best cadet” and eventually took command of a frigate, HMS Magpie.

With Britain at war in 1940, Philip joined the Royal Navy, serving as a midshipman on HMS Ramillies, and was posted to the Indian Ocean.

The Duke of Edinburgh was mentioned in despatches for his service during the Second World War. He was a midshipman aboard HMS Valiant off the southern coast of Greece when he earned his honourable citation.

A young naval officer, he was praised for his actions in the decisive Battle of Cape Matapan against the Italian fleet in March 1941.

Philip had been in control of the searchlights as the ship battled an Italian cruiser when he spotted an unexpected second enemy vessel nearby. He survived unscathed amid his shattered lights as an enemy cannon shell ripped into his position. His commanding officer said: "Thanks to his alertness and appreciation of the situation, we were able to sink in five minutes two 8in gun Italian cruisers."

Shortly afterwards, he was awarded the Greek War Cross of Valour. The duke later spoke of how he coped when his shipmates died or were wounded. "It was part of the fortunes of war," he said. "We didn't have counsellors rushing around every time somebody let off a gun, you know asking 'Are you all right – are you sure you don't have a ghastly problem?' You just got on with it."

At the age of 21, Philip was one of the youngest officers in the Royal Navy to be made First Lieutenant and second-in-command of a ship – the destroyer escort HMS Wallace of the Rosyth Escort Force.

In July 1943, Wallace was dispatched to the Mediterranean and provided cover for the Canadian beachhead of the Allied landings in Sicily. The ship came under repeated attack in the dead of night, off the coast of Sicily.

With quick-thinking, Philip threw a wooden raft with smoke floats over-board, giving the impression of burning debris which was enough to throw the Luftwaffe plane off target.

Hundreds of lives, including Philip's, were probably saved by this act. One of his colleagues, onboard HMS Wallace that night, was Harry Hargreaves, "Prince Philip saved our lives that night," he told The Observer newspaper in 2003, “I suppose there might have been a few survivors, but certainly the ship would have been sunk. He was always very courageous and resourceful and thought very quickly."You would say to yourself, 'What the hell are we going to do now?' and Philip would come up with something.”

Philip also served as First Lieutenant on the destroyer HMS Whelp in the Pacific, where he helped to rescue two airmen in 1945.

The men's Avenger bomber crashed into the ocean during the Allies' Operation Meridian II against the Japanese. The duke, who was 23 at the time, sent the battleship to the spot where the plane had gone down. The bomber had flooded and rough seas were preventing the men from getting into their dinghy.

Philip, who first spoke publicly about the incident in 2006 for a BBC Radio 4 documentary, remarked in a typically matter-of-fact manner: "It was routine. If you found somebody in the sea, you go and pick them up. End of story, so to speak."

He alerted the sick bay, arranged for hot food to be waiting for them and found new uniforms for the airmen. The men had no idea who their rescuer actually was until they were told he kept a picture of Princess Elizabeth in his cabin.

The royal wedding took place just two years later.

Philip was reunited years later with one of the airmen – former Petty Officer (Airman) Norman Richardson – at the Royal British Legion's Field of Remembrance at Westminster Abbey in 2013.

Mr Richardson, of Weybridge, Surrey, said at the time: "We had a joke about Prince Philip giving me a set of his clothes when I was picked up off the coast of Sumatra. The duke still remembers it, and I told him they weren't really his clothes, they were the property of the purser's store."

The duke was on HMS Whelp on September 2 1945 in Tokyo Bay when the Japanese surrendered. He recalled the horrors of seeing former prisoners of war returning from the camps. "It was an emotional experience. These people were naval officers who hadn't been in a naval atmosphere for three or four years, sometimes longer," he told a BBC documentary in 1995. "When we sat down in the mess they were suddenly in an atmosphere that they recognised. They sat there with tears running down their cheeks. They just couldn't speak."

For seasoned veterans, there was little doubt Philip had had the potential to rise to the very top of the Royal Navy. The late Terry Lewin, who served alongside Philip when both were junior officers, went on to become First Sea Lord. And it was once suggested to him had the duke remained in the navy, they might have been competing for the top job, "I don't think the competition would have been very strong," Lord Lewin later told the BBC, "He would have walked it."

Yet as an officer, Philip never achieved the level of affection Lord Mountbatten managed. He was notoriously not one to suffer fools gladly. And one junior sailor on HMS Magpie said he never wanted to serve under him again. But Philip is also remembered as an immensely capable officer who drove himself as hard as his men and remained cool in moments of crisis.

Although the duke's royal duties became his first priority, he maintained his interest in the Royal Navy - and used his position to support the preservation of Britain's maritime heritage.

In 2011, the Queen appointed him lord high admiral, a post that has existed since the 14th Century.

The duke maintained his love of ships and the sea, which remained a constant source of fascination to him. "The environment is completely different to anything you'll find on land," he once said, "You're at sea and exposed to the elements in a way you never are ashore. At sea you're in a cockleshell in this enormous expanse of the ocean. So that tends to cut you down in size a bit."

RIP HRH Prince Philip.

#first sea lord sir jonathan band#prince philip#duke of edinburgh#quote#britain#royal navy#military#sea#duty#service#world war two#royalty

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Khutulun

The pride of the Mongol Empire.

Birth: 1260 Death: 1306

Genghis Khan is a legendary figure in History. The man who descended upon continents and countries, winning battles across the land from modern Austria to Indonesia and cementing a legacy that would last the ages. Whilst a large population of peoples on the Asian continent are thought to be descended from the famous warlord - Khutulun was his great, great granddaughter.

The Mongol Empire was like many empires of the day, it was patriarchal and women would hold lesser ranks than men. However women would ride horseback, fight in battles, tend to herds and some would come to influence the men in charge. Children were raised by both the mother and father, children being homeschooled would learn the necessary parts of their future roles from their parents. Widows would also inherit the property of their husbands and become head of their family should they suffer the loss of their husbands. Women could control significant human, animal and material resources. Imperial women were also critical to the expansion of the Mongol empire. They could be integral to the arranging of marriages to benefit their families politically, as marriages were arranged between families, a fantastic example of this is when the five daughters of Chinggis Khan and Borte married their fathers allies during a critical part of the empires expansion. Women participated actively in their society and were highly valued for it.

In the time that Khutulun was born, the once great and vast Mongol Empire had started to falter and cracks had started to appear in its framework. A rift had appeared in group. Some favoured the old ways, riding, hunting, shooting and fighting. The very practises that had birthed the empire. Men like Kaidu of the Changatai Khanate and father of Khutulun favoured these old ways. Her uncle, Kublai Khan instead favoured politics, governance and things that did not gel with the old ways. This conflict in ideals caused friction within the empire and ultimately Kaidu and Kublai began to active battle one another.

Alongside her fourteen brothers, Khutulun was brought up in the nomadic way. She trained as many others would in combat, horse riding and archery. Khutulun thrived in this way of life but also had the military know how and brains to match the brawn. The conflict between Kaidu and Kublai lasted thirty years, throughout which Khutulun was by her fathers side in the conflict and was often the one he sought advice from in political and military matters. Khutulun was formidable, Marco Polo described her;

“so well-made in all her limbs, and so tall and strongly built, that she might almost be taken for a giantess” and that she was “so strong, that there was no young man in the whole kingdom who could overcome her, but she vanquished them all”.

Her valour was second to none. Polo would also write that she would often make off the cuff decisions in the midst of battle. Riding from her fathers side and pouncing on the enemy as she did and dragging them back to her father.

Now - the challenge:

When Khutulun came of age, as a princess of a Khan, there was a long line of families and men vying for her hand in marriage. However Khutulun had other ideas. She issued a challenge:

She would marry no suitor unless he could beat her in a bout of wrestling and they would owe her a hundred horses if they could not best her.

Khutulun ended up owning a lot of horses.

Kaidu’s clan valued the physical ability above all else and there were no weight classes, rules for combat or referees standing by to tell you off: anyone could issue a challenge and winners were regarded with an air of being god like. Khutulun was a fantastic wrestler. It is testament to her ability that it is said she owned 10,000 horses upon her death - meaning that she won and she won often. Even when a prince arrived that was favoured by her family, her father even asking her to lose the match and marry well, she won the match and walked off with 1,000 horse which the prince had bet (cocky that he would win) and no husband.

Khutulun was stubborn about the challenge she had thrown down but eventually she married. There are several accounts to why she might have married. One states that rumour began to spread that she was conducting an illicit affair with her own father and thus had to marry out of necessity to quell these rumours. Another version has her falling madly in love with another mongol leader. other versions have her marrying a man sent to kill her father and some see her marrying a soldier in her fathers army.

Nevertheless, she was her fathers favourite and towards the end of his life; he tried to have her installed as heir to his fortune. This met stiff resistance. Despite the freedoms and standing that women held in the empire, it was still a patrilineal society and Khutulun had 14 brothers with a claim to the empire. Her brother Orus became the next Khan and gave her a commanding position within his armies. However she died in 1306, giving rise to questions about her manner of death which remains unknown. Her unknown manner of death has led some to believe that her death was as a result of her presence becoming unwanted. Her prowess as both a commander and a warrior could lend credence to the idea that she was killed to end her influence.

Khutulun disappears from history for a while after her death. Her comeback came when a frenchman writing an account of her great, great grandfather came across the legend of Khutulun and wrote a story about her. Turandot changed her challenge, in this story the great princess was written to challenge her suitors to riddles and the losers would instead be killed. Later when this story was adapted into an opera, Khutulun was transformed into a no-nonsense woman who finally gave into love - something that greatly disregards Khutuluns true legacy.

Mongolia remembers Khutulun for her true legacy and slowly, Khutulun has been returned to being the last true nomadic warrior princess.

Stuff:

https://www.historyextra.com/period/medieval/the-brutal-brilliance-of-genghis-khan/

https://www.historyonthenet.com/mongol-women-in-society

Women and the Making of the Mongol Empire - Anne F. Broadbridge (Cambridge University Press, 18 Jul 2018)

https://historywitch.com/tag/khutulun/

https://www.rejectedprincesses.com/princesses/khutulun

https://allthatsinteresting.com/khutulun

https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-famous-people/khutulun-0010840

#khutulun#mongolian empire#warrior princess#excellent athlete#badass all around#yeah yeah i know#what upload schedule#mongol#genghis khan#kublai khan#mongolia#history#biographies#short biography

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Post-modern Ares:

“God of war (brutality & valour).” = a tired walking monument of all evils in the world, not sure if he wants to exist.

(irl references: General Radahn from Elden Ring, Kratos from God of War)

a very large man piled in hundreds of layers of military garbs that makes it seem impossible that he’s standing (military jackets, bullet proof vests, greek bronze helmet, roman garbs, gas masks, endless medals faded of colour and rusted, guns and dangers and swords, etc. all are a mix of nationalities because every country is guilty of war), a war-torn face with a 1000 yard stare, eyes are bloodshot and blood red.

Rarely speaks, voice is deep and booming like a war trumpet, sharp and clear words, one of the loudest roars ever heard. always a bummer to be in the presence of - if not wholly intimidating by his might and lingering anger, just depressing in his endless stories of veterans and glory days of war gone to waste. his shadow hovers over war monuments, but when there is conflict going on in the world, it is concerning when he’s not there (the best determination between war and genocide), would show up at the aftermath to shadow the casualties of war (strangely a softy with children). a lumbering old puppy dog for Aphrodite, only time he seems to relax is at her touch - sings ‘Lili Marlene’ for her.

Seen on TV most of the time - in international conferences or frontline footage, or in military museums. Only travels to return to Aphrodite to remind him of what he exists for.

Given a chance he would explain how he is still needed, he reminds humanity of the ugly side of war now more than ever - “The last few centuries, I have not seen Athena fight beside me, nor have I charged on my own two feet. Now I am chained and dragged into battles. I am stabbed by my own comrades into screaming, my roars of pain rewritten as a battlecry.” - there has not been any ‘glorious war’ for centuries.

Ares.

703 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vimy Blindness: The Unknown Commanders of the CEF.

This is the text of a presentation I gave today at the Where To Next symposium at UNSW Canberra. The symposium was hosted by the Australian Centre for the Study of Armed Conflict and Society. The topic of the day was now that the centenary is coming to a close where does Great War history need to go next? And on that topic I put together this. The day was apparently filmed so when I get the link I’ll probably slap that up too.

Snow blindness is caused by the enormous reflection from snow or ice. It’s a temporary condition that causes a loss of vision due to the overwhelming power of reflected light. Much like Gallipoli and Sir John Monash for Australia, there are two things, one person and one event, that outshine the rest of Canada’s First World War history. Those two are of course Sir Arthur Currie and Vimy Ridge.

Sir Arthur Currie, the real estate developer and insurance broker turned soldier is in one way or another at the centre of much Canadian First World War historiography. His story is one well known and often told because it has all the elements that make for a great tale. There's the drama of his pre-war dealings and the embezzlement of military funds to cover his mounting debts. There's his time as a brigade commander during the Second Battle of Ypres to his promotion to the command of the First Canadian Division and his part in the Battle of Vimy Ridge. This lead to his eventual command of the Canadian Corps and the outstanding parts they played in the Battle of Amiens and the Hundred Days Offensive. Interspersed between these momentous events is his political battle with the erstwhile Canadian Minister of Militia and Defence, Sam Hughes and the struggle when two of Curries subordinates discovered his financial problems and their combined attempts to solve them before knowledge of his indiscretions were made public. This is a story that extends beyond the war itself and only finishes in the 1920s with a highly publicised libel suit launched by Currie on a Canadian newspaper friendly to his nemesis Hughes. It's a story that plays well to modern sensibilities and as more than one commentator has noted, Currie is that most beloved of combinations; a good general and a 'colonial'. He can easily be portrayed as the opposite of Alan Clark's Donkey generals.

The Battle of Vimy Ridge is the other blinding light in the realm of Canadian war writing. Seen in much the same way that Gallipoli is in Australia and New Zealand, Vimy Ridge exemplifies the spirit of Canadian martial and national valour. This was even noted at the time with Canadian Director of Medical Services, brigadier A.E Ross writing "in those few minutes I witnessed the birth of a nation.”1 Vimy, part of the wider Battle of Arras, was the high point of the British involvement in the French Nivelle Offensive. On 9 April 1917 the four Canadian divisions and one British division attacked the strongly defended Vimy Ridge and after three days of horrific fighting, held the heights. It was also the first time that all four Canadian divisions, containing men from every region of Canada, had gone into battle side by side and despite the 10,000 casualties they took, the attack was a success. Given its significance at the time and since the story of Vimy has been written, rewritten, dissected and discussed from every conceivable angle for more than a hundred years now. A cursory search on Trove returns over 300 book results for Vimy, covering the full range of academic history and popular history to novels to plays. While the day may not be commemorated, or perhaps celebrated, in the same way that Anzac Day is, it remains a potent symbol of Canadian sentiment and national identity.

If one shades their eyes from the blinding light of Currie and Vimy then they will find a collection of people waiting to be rediscovered. But the question remains that why have these senior commanders and administrators of the CEF not yet been examined. Canadian historian JL Granatstein addresses this question in the Oxford Companion to Canadian Military History, as part of the broader dearth of military biography in Canada. He draws attention to the lack of quality historians researching Canadian officers and the shortage of both public and publisher interest in their stories. Of the attention given Canadian soldiers most tends toward stories of action and heroism beloved by popular audiences. And when biography is seldomly addressed by more skilled historians, they lack the readability or flair of the popular authors. Granatstein says; "In the ceaseless bleat of military historians – or of non-historians who write reams of historical doggerel unfazed by lack of skill – to be taken seriously by their peers, it would help at times simply to write better history, or to expose politely those who do not.”2

But though style may be lacking this isn't sufficient to answer the question of why Canadian commanders of the CEF, or study of senior Canadian officers in general, remains so underepresented.

On the bright side the last two decades have seen growth in academic studies of Canadian command, particularly by historians like William Stewart with his 2015 book the Embattled General on the somewhat unlucky Richard Turner, commander of the Canadian 2nd Division. Likewise, Patrick Brennan of the University of Calgary brought up this very question in a 2002 article and has perhaps done the most to advance the cause in this regard. He has published several pieces on senior commanders of the CEF, covering battalion commanders, a brigadier and a divisional commander. None of this work has been longer than a journal article. A number of other historians such as Douglas Delaney, Stephen Harris and Kenneth Radley have all done some research in the area of Canadian command but only as one part of a larger work. What is yet to be done is a broader and deeper look at the men who occupied these key positions in the CEF.

The hierarchical nature of the military means that it's vital to understand how the command system operates and how the personalities, skills and experiences of the men in command are applied to the organisation under them. In Australia over the last few decades historians have put considerable effort into studying the men who commanded the divisions of the AIF, with most of these generals receiving biographies and Monash, like Currie, receiving several. Questions regarding individual generals, their personal command philosophy and how that translated into the administration, training and fighting of their divisions remain to be asked, let alone answered. Most of the constituent parts of the Canadian military have been examined in some detail but its generals by and large have received less research than its chaplains.3 Without an understanding of the men at the top of the heap, our understanding of the organisation is incomplete. This is one area which there is much work still to be done with only two of the eight Canadian divisional commanders having received a book length treatment. More conspicuous research has been put in by New Zealander Christopher Pugsley, who in his work has looked at the dominions, comparing Australian, New Zealand and Canadian wartime experience. Command has factored largely in his comparison of the three dominions and his analysis has deepened our understanding of the many similarities but more interestingly, the vast differences in the dominions at war. Research such as this, looking at these officers in comparison to one another and in context of the war they were collectively fighting, is one potentially fruitful area of research for the future.

My own research falls in this area and I'm hoping it will go some way to filling this gap. The project is an analysis of British and dominion divisional commanders, looking at both their military and personal lives. One area I'm particularly interested in is the informal social networks that underpin the Edwardian armies of the British empire. They were often formed early in these men's careers, during their time as junior officers in the regiments, at staff college in Camberly or Quetta and serving on the staffs of senior officers. Maintained through copious amounts of correspondence these networks spanned the entire empire as officers were sent from Britain to the dominions and colonies. With the advent of the Imperial General Staff and dominion officers spending time with the British Army, along with the practice of seasoned British officers acting as Inspector Generals or advisors to colonial militaries these informal networks grew to encompass officers from every corner of the empire. In this way relationships were formed and networks grew that enabled the disparate armies of the British empire to build not only a level of interoperability, but also a level of cultural and gentlemanly conduct that benefited its participants. Thus, when the CEF, and the AIF and NZEF for that matter, went to war in 1914 the British generals who ended up in charge of dominion troops were often already familiar with at least some of the men now under their command. These unofficial networks within the officer corps of the imperial armies were important to the military prospects of officers seeking promotion and they mattered to the smooth running of general staffs. How far promotions were questions of merit and professional skill and how much patronage and relationships still mattered is another question that deserves to be asked, even if it cannot be satisfactorily answered.

The lack of work on Canadian command is not due to the absence of primary records, although some key individuals didn't leave many papers, but is due more to difficulty in access. Canada is a large country and with comparatively little interest in military history, not to mention military biography, especially now as the centenary draws to a close, money to conduct research is difficult to come by. With the recent boom in digitisation this may offer the enterprising historian an opportunity to turn down the light emitted by Currie and Vimy and to uncover some yet untold stories.

#ww1#wwi#great war#world war 1#canadian army#CEF#canadian history#history#military history#long post is loooong#hiscourse

62 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Elendenal sat down with a creak of plate, moving his right hand - unadorned in plate, to enable his intended task - to take the pen from its place inside the holder, looking down to the parchment spread before him. A moment’s consideration and he set the pen to paper, writing his thoughts upon its surface.

Zephyr 25, 1300 AE

I find myself at something of a crossroads, writing these thoughts upon paper as a means to draw the feelings associated to them from me, and perhaps establish a record to be used in future. Let me state for the record herein, that I am a man conflicted. These past weeks have seen extraordinary developments in my life, but so too have they seen me face challenges I did not - perhaps naively - expect to have to confront again. There are barriers in my path, now, that must be removed with utmost delicacy: lest the effort to do so shatter the very thing I wish to reach beyond their obstacle.

I have been made Field Marshal of the Coalition, if that is what it can be called, at Lake Doric. This is not how I intended to spend my time at this Camp, but neither can I write here in honesty that it is a turn of events I am going to strive to oppose. My arrival in Lake Doric was less a conscious decision and more a matter of providence: a path that was laid for me by Balthazar, I suspect, through my mortal associates. If not for that night in the Rurikton Cafe, I never would be here.

None of this would have happened, had I not met Margrave Elysian, my now-dear friend and brother in cause, upon that auspicious evening.

It is ironic, I believe the term is, that I am impeded in my task to rid the enemies of mankind from Lake Doric by the very people that convinced me to give my aid here. Lady Aubrey Valente knows not how much she changed my life, with that simple suggestion of hers. Luxelen, my friend - or so I hope - stands as the largest impediment in my attempts to bring an end to the carnage and suffering in Lake Doric. I have attempted to reason with her, and shown her respect and courtesy in the act, and at best she has responded with cool disdain.

I am told by Alissa Lepre, the newest member of the Scions of the Six, that it is Luxelen’s way of adapting - that she will ‘come around’ eventually. While I am not opposed to her having the time she needs, it makes me worry for the people of Lake Doric. While the one that should be an ardent ally dithers, they die by the dozens, and more refugees are created every day. It is not that I do not understand her recalcitrance, it is simply that I do not believe that this is the place for it. I will never understand her mind, I fear, for we are naturally opposed creatures, her and I.

The Refuge Defense Force will be recalled, according to Alissa, and that is for the better. Luxelen does not understand the fundamental necessitation of war: she is too passionate, too focused on what she sees - whether correct or incorrect - as an enemy to understand when she does not know something, or when her views are damaging, if not outright destructive. A rogue element in a battlefield, be it a single person or a full unit, pose a danger to their parent force and allies even greater than an enemy. A single misstep in the grand strategy, a single unforeseen disobedience, and the entire army risks shattering. It is one thing for your enemy to surprise you, it is far more catastrophic to be sabotaged from within - especially when that sabotage is entirely unintended.

If the R.F.D take to the field without being part of the chain of command, they will kill a great many people, and I fear many of them will be due to nothing more than idealistic ignorance. War is not like the stories, it is not a tale where a valorous few can make the difference in spite of everything else. It is methodical, it is alive, it is a constant game of chess between Commanders. One piece out of place, and the entire board is compromised. If against all odds they take the field and refuse orders, I will not sanction a diverting of force to save them, and nor will I allow them to deploy within a mile of Coalition forces.

I cannot justify killing dozens, perhaps hundreds more, and crippling our forces to rescue a unit that is at this stage more of a strategic impediment than a benefit. I pray they do not fight, they are good people, kind people, even if they make terrible soldiers. Humanity needs their compassion, their kindness, and their benevolence - but I cannot use a sword that refuses to swing where it is directed, and the R.F.D is akin to the most unreliable blade in the armoury.

Luminary Drake Griggs also appears to be a potential obstacle, which is odd from a man I considered a fast friend. At the meeting I called for the military leaders of the camp, Lord Griggs was at best a quiet observer, at worst mildly disinterested. He strikes me as a man of few words absent cause, yet it was his support I was accounting as one of the most resolute. Perhaps this estimate of him as a man unconcerned with politics was overhasty. The Luminary offered no objection when I was nominated with Aodhan and Cainneth, yet now he appears almost to be avoiding me, as if he does not wish to acknowledge the reality of what occurred.

This is worrisome, as I factored he and Cervato Haswari both as staunch and committed allies in this war. I pray I can still count on Cervato in this, but if the Luminary is hedging, I cannot help but feel she will follow him in doing so. This would be crippling to our coalition; the Accord is set to lead the main core of our infantry.

Aodhan Helstrom, Morgan Valister and Cainneth Cross I have no concerns about. The first is a man of war, he knows what’s needed and he understands the demands of honour and commitment to purpose. I foresee many late evenings discussing strategy and tactics with the weathered Headmaster, a disciple of Balthazar in both thought and deed. Cainneth Cross I can safely say has become a treasured friend, and a source of unerring integrity and wise counsel. Of all those to have joined the Scions, he truly is an Exemplar in truth. As for Morgan Valister, she is precisely what one would expect: austere, stoic, and utterly merciless. In her eyes, I see the rage of butchered Ascalon, and a war fervour to rival mine own. Lady Valister will be an integral part of this war effort, both for her mental acumen and the morale she will inspire in those around her.

These allied forces hold much promise, in the prosecution of the war against the Mantle. With Crown support coming from Cainneth, and the combined forces of the Accord, and Noble Houses part of the various organisations in camp, and the brilliance of the Schools, I had expected a powerful war machine. I am reminded, at this time, of one of my first initiatives: a campaign against a banner of Dragonsworn on behalf of the Vigil, in Scion 215, 1327 AE. We had tracked their forces to a large expanse near the Ascalon border, and I had been commissioned by the Vigil to prosecute the hunt for the heretics. I still remember their mad screeches as my couched lancers shattered them, the impact of the lances blowing apart their bodies and the thunder of the charge crushing skull and bone underhoof.

There is nothing more satisfying than a victory won through adherence to the doctrines of war: to adherence to honour, loyalty, and love of one’s comrades. I cannot think of a more fitting reward than the smiles of joy on the faces of those you led not into death, but into the new dawn, through superior use of assets and dominion of the strategic and tactical planes. There is a beautiful purity in the attainment of a good victory, of a pure victory, and the successful prosecution of an entire campaign - absent regret, or the stain of unsavoury deeds, neither of which I am pleased to say I have ever had the displeasure of experiencing.

Cristian Eskara is not in the same situation.

A man of considerable zeal, he continues to teeter between redeemed and damned, switching one day from humility and sombre remorse to arrogance and unapologetic savagery. The High Exemplar has become a wraith of his own destruction, justifying things that could never be justified, impugning my reputation and motivations, and diverting from the conversation the moment his contradictions and falsifications are highlighted. It saddens me. I have faith in Cristian Eskara, more faith than Genevieve believes I should have, but I cannot turn away from him nor forsake him. In many ways, he is a victim of his own circumstance, a war casualty over a much greater period of conflict. I wish to believe he can save himself from his own demons, even if nobody else will.

My next decisions will shape what is to come, and I know I must tread carefully. If I can secure the Luminary’s support, dispel Luxelen’s doubts, and manage to unite these people - to gain the chance I need, I can shatter any lingering misgivings. I will prosecute this war with integrity, honour, and valour befitting the God of War. I will take this burden upon my shoulders and carry it to the end of the line. I have no aspirations for Empire, no matter what Cristian believes: I just wish to end the suffering, end the bloodshed, and protect those falling victim to its growing violence. Every day this war drags on, good men, good women, pay for it. It is my duty to defend mankind against that which assails it, and no threat is greater in its immediacy than the Mantle at Lake Doric.

I pray that my comrades in this cause rally to me, that Drake, Cervato, Luxelen, Cainneth, Aodhan, Morgan, William and Cristian - yes, even dear, misguided Cristian - stand with me and give me the faith I need, the faith I have given them, to not just end this war: but do so in a way that every man, woman, and otherwise can look back on and say was done rightly, and properly. If they but offer me the moment, I will seize it, and victory will follow. This is not simply a fight for land or territory, it is a war for the human soul. How we fight it and how we win it are equally as important as winning itself.

I will pray they recognise the truth of my intent, and give me their support.

The alternative, I fear, is an end to all we have worked for.

Signed,

Elendenal Pendragon IV,

Scion of Honour.

( @luxelen, @cristianeskara, @genevievekent, @lordgriggs, @rising-ember )

#lake doric#the stormfall crusade#the stormfall coalition#cristian eskara#drake griggs#lucas elysian#luxelen larkspur#genevieve kent#morgan valister#cainneth cross#aodhan helstrom#cervato haswari#elendenal pendragon#story#the scions of the six#journal entry#memoirs

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Private William J. Bartlett was a wizened 35-years old when the letter transcribed below was published. He was a journalist by profession and the object of his letter was 13-years his junior. The former survived the war, the latter did not.

“HE DID HIS BIT”[i]

[BY W.J. BARTLETT.]

Pte. W.J. Bartlett of the 18th Battalion, the author of this story, is a former member of the Advertiser editorial staff. His letters from the front, and from England, have appeared from time to time in this paper.

What a simple phrase, but oh, how deep its meaning! He did his bit for King and country, and then passed away.

What tales of great human struggles this bloody war are wrapped up in this simple sentence. What pain and suffering these brave heroes suffered [where] they passed to the great beyond.

Go where you will in France and Flanders, you will come across cemeteries, and on the wooden crosses you will often find the simple epitaph: “He Did His Bit,” and as I have gazed on the little mounds of earth in a vision, I have seen them fighting in the grim battles, fighting for their very existence, for their King and country. Often I have muttered if only the people at home knew the full significance of the saying “He did his bit.”

Many of the lads who have fallen have performed great deeds of gallantry, but their names have never even been mentioned in dispatches, simply because their heroic acts were not witnessed by the “higher ups.” Every battalion, English and colonial, had had such heroes in their ranks, and their memories will live forever in the minds of their comrades who are spared to pull through this grim war.

The 18th Canadian Battalion has had many brave comrades fall on the battlefield, and though their gallant deeds have never been blazed in the papers, they have never picked out for a D.C.M.[ii] or a V.C.[iii], their comrades who fought side by side with them, midst crashing shells and weird whistling bullets, will always speak with pride of their daring acts.

One of those 18th heroes who hell in action, who did his bit, was Pte. H. Drinkwater of Galt, Ont., and a braver man never donned the King’s uniform.

But I said “man.” In reality he was only a boy, not long out of his teens. He was a Canadian to the fingertips, keen and alert all the time, and full of optimism.

No, he did not have the appearance of a soldier. His featured belonged to the feminine type, and his smile must have been born with him.

Young Drinkwater did not seem to know what fear was. No matter how dangerous a task he was given on the battlefield, he was always ready, and looked on the humorous side of things, even when the hellish shells burst near him and the shrapnel played on his steel helmet.

But it was the at the Battle of St. Eloi[iv], where Drinkwater distinguished himself most, when the terrific struggle for the crater was in progress. It was a night long to be remembered by those whose mission it was to add further honor and glory to the good old Union Jack.

About an hour after midnight, the Canadians set out on their difficult task. From the German line flare after flare went up to search for attacking parties. The deadly machine guns of the enemy occasionally swept the battlefield , and a few shells would whistle through the air and burst with a thunderous roar. But the boys pressed onward to their goal.

Now the hellish sounds of crashing bombs rent the air. Fritz was getting his iron rations. Then it was hell let loose. The enemy opened up this artillery, and huge shells raced through space, high explosives and shrapnel burst among the Canadians. The sky was now lit up with hundreds of flares of many colors. Our artillery was more than equal to the Germans and the guns poured forth murderous volleys. While the battle was at its highest, young Drinkwater, who was in the think of the hellish destruction, was called upon as guide for an officer. From place to place he led the way unflinchingly. The shells falling all around and the very earth quivering from the might explosions. Yet he accomplished his heroic task. Then again he went back to the crater, and this time he volunteered to bring in one of our bombing parties just before daybreak. Again he was successful, bringing back every man safely. It was, indeed, a plucky daring deed, and the hero came through unhurt.

But the fortunes of war are very strange. About a month after he was again in the trenches. Some seven comrades were with him. Young Drinkwater was talking of the good old days he spent in Galt and of the good times that were coming. Some dozen shells had fallen near when the merry conversation was in progress. Then in a few seconds the scene was changed. A big explosive shell fell amongst them with a terrific, deafening explosion. The laughter, the merry conversations were silenced, and the groans of the wounded rent the air. Young Drinkwater, the fearless Canadian lad, was among the wounded. Quickly his wounds were dressed, and he was carried on a stretcher to a dressing station. He was still conscious when carried out, and his chances seemed good in pulling through. But some hours after he left the suffering clay. The cruel ordeal was too much for him. Life’s curtain was rung down on the brave warrior’s life. He had done his bit.

The letter speaks eloquently to the actions of Private Drinkwater and this soldier obviously had an impact emotionally on Bartlett as he writes with keen direction and purpose to his audience in order to convey and portray the heroism and youth of his subject. The letter also expresses, at a soldier’s level, the intensity of the combat at St. Elois Craters, the 18th Battalion’s first blooding during battle.

As can be seen from his photograph Private Drinkwater did look young, and at 5’ 3.5” he was shorter than most of the men in the Battalion. He needed permission from his mother, Mary Drinkwater, duly gave permission to her then 20-year old son to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force with the 18th Battalion. He enlisted at Galt (now Cambridge), Ontario on October 28, 1914. Drinkwater must have been eager to go to war as enlistments had only started with the 18th Battalion on October 22 of that year.

Bartlett, as mentioned, was part of the editorial staff at the London, Advertiser and he had enlisted with the 18th Battalion at London, Ontario. He was not as quite as eager, joining on December 2, 1914, but he joined early enough to become one of the “originals” to form the Battalion before it went overseas.

It is not clear from their service records how these men were connected. We do not know if they served in the same platoon or company. Perhaps Drinkwater’s actions were widely known to the men of the Battalion, the stuff of martial legend. What is apparent that during the morass that was the action as St. Eloi Private Drinkwater kept his head and was able to guide an officer through the confusion of the mutilated and mis-numbered craters to help that officer in some constructive fashion. Drinkwater further distinguishes himself getting a party of bombers that are outside of contact with the rest of the Battalion back to the relative safety of the main line of resistance, such as it was during St. Eloi.

Bartlett establishes vividly the crucible in which Drinkwater distinguishes himself. St. Eloi was an introduction to the hell of intensive trench operations, that was exacerbated by poor execution at the divisional level.

Tragically, as young Drinkwater speaks of the future, his is brought to am moment that would lead to the conclusion of his life. He would die of his wounds at the No. 6 Canadian Field Ambulance on April 25, 1916. Ironically, on that day, the 18th Battalion War Diary states, “Battalion in Trenches. Very quiet day, nothing unusual occurred[v]. LIEUT. H.A. COLTER arrived as reinforcement.” The irony does not appear to be lost on Bartlett. Part of his message about his comrade is about how the actions that merit recognition are not, and he does take a swipe at the process of nominating awards as, at that time, only officers who witnessed acts of valour could put those acts forward for consideration of recognition.

The letter offers a glimpse into the admiration of one soldier for the valour and duty of another. Bartlett is a journalist and a wonderful instrument of expression towards this end. He gives a look back at the feelings of a soldier – a mixture of imperial nationalism and pride (“For King and country”) mixed with a hard-bitten scepticism of knowing that the public will never know the sacrifice, in part because of the “higher ups” and the military bureaucracy that prevents soldiers like Private Drinkwater to be recognized (he never was except for the standard war medals, scroll, plaque, and Silver Cross for his grieving mother) for “Doing Their Bit.” Bartlett helps his audience to understand a bit of at what cost this service comes.

As a further testament to Private Drinkwater, a letter from Captain Samuel Monteith Loghrin, the Company Commander for “B” Company of the 18th Battalion wrote of some of the experiences he shared with Drinkwater. It was Captain Monteith that was led by Drinkwater during the St. Eloi action:

“”I regret very must to inform you of the death of your son. He was killed when on duty with our company. A heavy shell struck the trench where he and two others were standing, and all of them were wounded. Your son was conscious when being removed on the stretcher. I thought he would recover, but found the next day that he had died in the ambulance between the first dressing station and the field ambulance. He was buried in a cemetery close to our rest camp where I am writing this letter, and I intend to go up to the cemetery and arrange for marking his grave with one of our regimental crosses. Your son died doing his duty and gave his life in a noble and honourable cause. He was a bright, cheery boy. I remember before leaving England he had appendicitis and was to be left behind. He came and pleaded with me to be taken with the 18th Battalion. I spoke to the doctor and we arranged it, and for a time I lightened his duties until he was strong and well. He was a very brave young man, and acted as a guide for me one night in a grenade attack.[vi] Not the least sign of fear did he give, but was joking all the time, even when the metal was flying like a snowstorm. His humorous disposition made him very popular with the boys and he will be much missed by all of us. As a father, I can partly appreciate your sorrow. If I can be of any assistance in giving further information I will be pleased to do so.”[vii]

[i] Submitted to the author by Allan Miller, curator of the 149th Battalion CEF – Lambton’s Own Facebook Group. Original article from: The London Advertiser. June 6, 1916.

[ii] Distinguished Conduct Medal.

[iii] Victoria Cross.

[iv] It is strongly recommended to reference Cook, Tim (1996) “The Blind Leading the Blind: The Battle of the St. Eloi Craters,” Canadian Military History: Vol. 5: Iss. 2, Article 4. Page 25.

[v] Author’s emphasis.

[vi] Author’s emphasis.

[vii] Galt Weekly Reporter, May 11, 1916, Page 1.

“He was a Canadian to the fingertips…” Private William J. Bartlett was a wizened 35-years old when the letter transcribed below was published. He was a journalist by profession and the object of his letter was 13-years his junior.

#Captain Samuel Monteith Loghrin#Galt Ontario#London Ontario#Private Harry Drinkwater#Private William J. Bartlett#St. Eloi#The London Advertiser

0 notes

Text

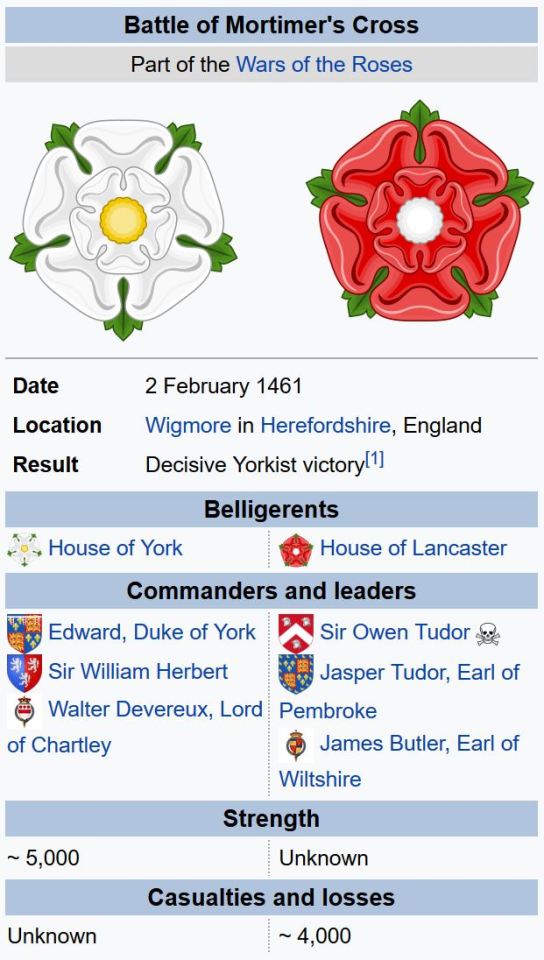

Battle of Mortimer’s Cross.

After reading several accounts of the battle of Mortimer’s Cross over the years this one stands out. It is far from what might be called academic and probably contains historical errors. Nevertheless, it brings the Battle to life. It concentrates on the people and places not the military strategy or political background. There are probably better sources if that is what you seek. Historians are consistent in recording how little is known about this battle when compared with other Wars of the Roses events. It is more than ‘Historical Fiction’ and give a sense of time and place.

If you prefer a more academic but no less entertaining account of the battle then read the following. It is no less interesting and almost certainly more accurate.

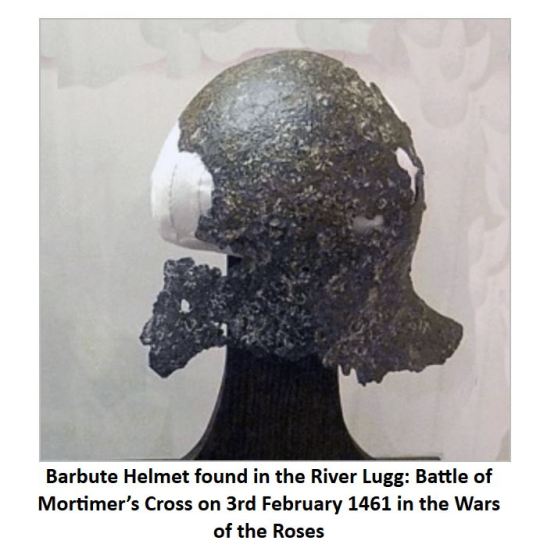

The Civil War of 1459 to 1461 in the the Welsh Marches: Part 2 The Campaign and Battle of Mortimer's Cross – St Blaise's Day, 3 February 1461

by Geoffrey Hodges

http://www.richardiii.net/downloads/Ricardian/essay_civil_war_1459_1461_mortimer.pdf

Background

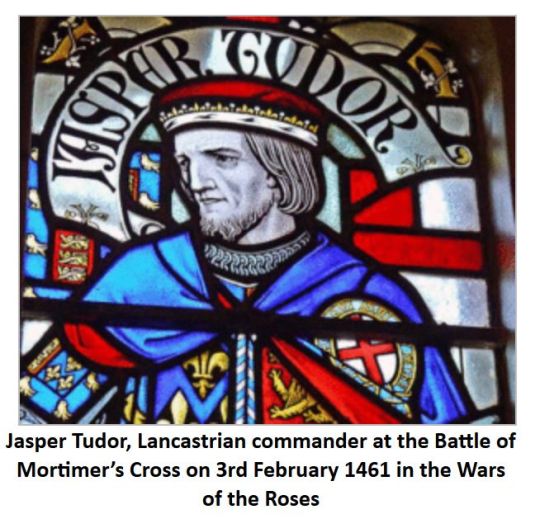

Upon the death of the Duke of York at Wakefield the previous December, the Yorkists were led by his 18-year-old son Edward, now 4th duke of York.[4] He sought to prevent Lancastrian forces from Wales, led by Owen Tudor and his son Jasper, Earl of Pembroke, from joining up with the main body of Lancastrian forces. The elder Tudor had been second husband to Catherine of Valois, widow of Henry V; their sons, as Henry VI's half-brothers, had been made earls, and the family became a major power in South Wales. His army included Welshmen, drawn especially from the area of the Tudor lands in Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire, along with French and Breton mercenaries and Irish troops led by James Butler, Earl of Wiltshire and Ormond.[5] Edward, based at Wigmore Castle had gathered his army from the English border counties and from Wales. Among his leading supporters present were Lord Audley, Lord Grey of Wilton, Sir William Herbert of Raglan, Sir Walter Devereux and Humphrey Stafford.[6] After spending Christmas in Gloucester, he began to prepare to return to London. However, Jasper Tudor’s hostile army was approaching and he changed his plan; so as to block Pembroke’s advance and block him from meeting up with the main Lancastrian force which was approaching London, Edward moved north with an army of approximately five thousand men to Mortimer’s Cross. Source; wikipedia

Source;

Malvern Chase: An Episode of the Wars of the Roses and the Battle of Tewkesbury, an Autobiography

Edited By W S SYMONDS

Published by William North and Simpkin Marshall, Tewkesbury and London (1881)

MALVERN CHASE was first published in 1880 and its popularity was such that six editions were printed within ten years. Although William Symonds subtitled it as an `autobiographical' account of the Wars of the Roses, it is in reality a superb historical reconstruction supported by much documentary evidence.

The medieval romance not only satisfied the Victorian liking for all things gothic, whether in architecture, furniture, or painting, but, as a story of masculine derring-do, feminine fidelity, and ghostly portent, it also followed the literary fashion of the time.

The author's descriptions of the Malvern Hills and the Vale of the Severn, at a time when they consisted of forest, heath, and marsh, paint an appealing picture that provokes a yearning for those less crowded times, even if life was much more uncertain. The populist support for the Witchfinder to sniff out those experimenting with herbal remedies has a resonance with a latter-day suspicion of scientific research.

The book has been out of print for many years and this new edition revives for a twenty-first century reader its effective characterisation, breadth of scholarship, and lively narrative.

BATTLE OF MORTIMER’S CROSS.

We found the Welsh village of Presteine occupied by Yorkist troops sent forward from Wigmore, and a messenger was awaiting us from my father telling us to push on and join him there. We saw on our march Pylleth Hill, where the Earl of March gave battle to Owen Glendower, and after a desperate struggle was defeated and made prisoner. The scene of the personal combat between these renowned chieftains was below this hill, on the banks of the river.

I burned with impatience once again to meet my father, but no sooner had we arrived at Wigmore than we found he had moved southwards to join Duke Edward.

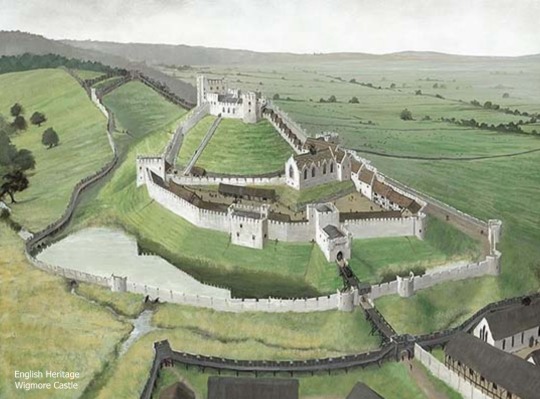

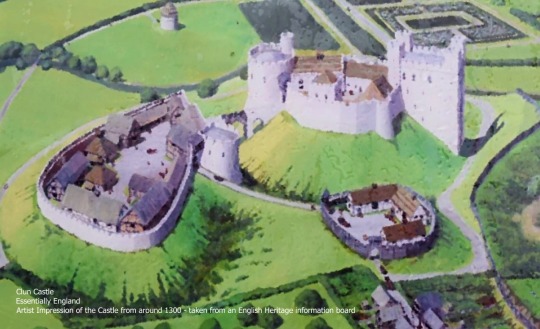

Wigmore Castle is built on the site of a stronghold as old as the time of Edward the Elder; and we admired the grandeur of the castle with its massive keep, situated amidst scenes of picturesque beauty. Long before we reached it we could hear the din and clangour of armed men, and outside the castle was a large village occupied by retainers, the dwellings situated upon a sloping rock and intersected by ravines. Hundreds of men-at-arms were in troops around the castle, while others were marching southwards towards Hereford, their steel caps and morions sparkling in the setting sun.

"Who goes there?" shouted a hoarse voice as we rode up to the drawbridge of the castle, and the reply, "Robin of Elsdune," seemed to be a sufficient password.

Robin now dismounted and spoke anxiously to the warder, who informed him that the widowed Duchess of York, and her sons, George and Richard (afterwards the Dukes of Clarence and Gloucester), were within the walls for safety; that an attack by the Welsh army under the Tudors was hourly expected, and yet the assembled forces were leaving to meet Duke Edward, trusting to the strength of the place, and the garrison, to keep it against all corners.

We then rode down the slippery paths to the village, where large wooden sheds afforded shelter for man and horse for the night, and arranged that our troops should be well cared for, and ready to saddle at a moment's notice. This done, Robin invited me to accompany him to an interview with the widowed Duchess of York, to present her with a token and message from her son, the Duke. We crossed a ravine to the eminence on which the castle is situated, and, on Robin again giving the password, we were conducted to the keep, a massive square palace, in which was lodged the widowed Duchess.

The great square was crowded with men-at-arms, with several domestics clad in mourning, and to one of these Robin addressed himself, showing the gold chain which he occasionally wore. In a few minutes the servant re-appeared and summoned us to the presence of the widowed lady.

Knowing that Duke Edward was nearly twenty years of age, I was surprised to see his mother so young and so beautiful. Clad in the deepest mourning, with golden hair and lovely blue eyes, it was hardly possible to believe her to be the mother of that manly sop, and yet the likeness was strong, for Edward had nothing of the "swarthy Mortimers" about him, and resembled his mother, yet without a shade of effeminacy.

The Duchess received Robin with more than courtesy, it was the welcome of a trusted friend, and as he knelt and pressed her hand to his lips, the tears flowed down her cheeks. On his telling her my name, she extended her hand to me to kiss, saying that she had heard from Lord Edward the good service I had rendered.

In the meantime Lord George had seized upon Robin, and was showing him a new bow and a wooden battle-axe, but the Duchess had explanations to receive from the Archer, so she called him on one side, and left me to entertain the boy and his little brother, Lord Richard.

Lord Richard was dark and swarthy like his father, with an inclination to high shoulders; his face was handsome, but his form was then feeble, and I little thought that I should behold him leading the most terrific charges at the battle of Theocsbury, or that he would become a knight renowned for feats of valour and of arms. Even then, as he sat upon my knee, he insisted on showing me "Robin's swing" with the battle-axe, much to the danger of my head, and his brother's also. Lord George had flaxen hair, and a weak expression of countenance.

The Duchess now addressed me, and noticing the ring on my finger, the gift of her eldest son, she said the service must be good that won such a token of his regard, as it was her own gift on his natal day. She also alluded to my interview with Lord Warwick, at his castle at Hanley, and I fancied a shade crossed her countenance as she spoke of him, for, notwithstanding the predilection of her husband and her son Edward, she never altogether trusted this powerful and somewhat unscrupulous Baron.

It was now time for us to take our departure, when the Duchess inquired if we thought she was safe from the raids of the Welshers within the walls of the castle, or if she should take sanctuary in the Abbey. To this Robin replied that "there were Marchmen to meet Welshers, and it would be difficult for all the Welshmen in Wales to penetrate to the stronghold of Wigmore Keep."

We now made our salutations, and took our departure, Lord Richard entreating us to take him with us, and once again practising the "Robin swing" at my devoted knees.

"Is not that a lady a man may die for?" said Robin, as we reached the bottom of the staircase. He now inquired for the Captain of the Archers within the walls, and, showing his golden chain, gave some brief directions which that leader appeared to accept without questioning. "We must now," he said, "make for the Abbey!"

The Abbey of Wigmore is distant nearly a mile northwards of the castle, and here lie buried the remains of the illustrious Mortimers from the times of Ranulph, who, having vanquished Edric Sylvaticus, Earl of Shrewsbury, received from the Conqueror himself the extensive possessions and immense estates which belong to this royal house. When we reached it, masses were being said for the souls of Duke Richard and his son.

Wigmore Abbey.

Wigmore Abbey was an Augustinian abbey with a grange, from 1179 to 1530, situated about a mile (2 km) north of the village of Wigmore, Herefordshire, England: grid reference SO 410713. Only ruins of the abbey now remain. Source; wikipedia

It was from his ancestors, who lie buried within the walls of this Abbey, that Edward of York inherited such decision of character that no sense of personal danger, and no tie of kindred, could ever turn him from the attempted accomplishment of a purpose once determined on, and I pondered, as I stood among the graves of this proud family, who never seemed to shrink from any violence to gain their end, if such was to be the character of the youth who, if success attended upon his arms, might one day be King of England.

My cogitations upon the Mortimers past and present were abruptly broken by the sound of a war trumpet outside the Abbey walls, and I found that some two hundred archers from the castle and village were assembled, and prepared to follow Robin of Elsdune, fully confident in his knowledge of the country, and his sagacity as a leader. In the meantime the Archer had sent a message to Tom of Gulley's End, and our own men-at-arms and horses had arrived at this trysting place. Robin spoke in Welsh to the archers, and I could perceive that he was giving precise directions for their guidance.

In the meantime, the Welsh borderers from the forest of Radnor and Kington had attacked the van ahead of us, and again the shouts and oaths of battle rent the air. In the narrow trackways it was only now and then that our riders could act and charge, but Robin and his archers seemed everywhere, and I could hear his long, keen, bugle blast now in the woods and thickets, and now in some copse, from which his men poured their arrows on the flanks of the Welsh forces. Nor did the Welsh forget their wonted bravery. They rushed upon their unseen foes into the churchyard and up the knoll, but only to meet death from the unerring shafts. With wild and terrible clamour, the whole army had now turned back, and closed in tumultuous throng round the village of Brampton Brian. Again and again we attacked them with our little body of horsemen, but some billmen threw themselves under our horses, and I had soon lost a dozen of our best troopers, while several fought on foot, having had their horses killed under them. I now saw that it was useless continuing this unequal strife, so, shouting to my dismounted men to ride behind their companions, we fought our way foot by foot out of the throng, and made for the village of Leintwardine, which had been appointed for our rendezvous and retreat. Soon afterwards the Archer joined us there, having lost only ten of his men, while the Radnor troops who attacked the van had retired towards Wigmore, Jasper Tudor having had a narrow escape of being taken prisoner. Our point had been gained, the whole Welsh army was now in full retreat to Knighton.

We now left the village, which in the morning we found in peace and tranquillity, and in the evening was crowded with the dead and dying. The moon had arisen as we rode into the village of Wigmore, and lit up the standard of York and Mortimer as it floated high above the keep of the noble castle.

Being well-nigh exhausted, I did not awake until after cock-crowing next morning. Robin had already looked to the horses and their riders, and was conversing with a scout who had arrived from Knighton, full of the rage of Jasper Tudor at the retreat of the whole army, owing to the ambush and attack of a few hundred men. His father, Owen Tudor, was with the horsemen of the rearguard, and had been dismounted, so that it was his charger Robin rode back to Wigmore.

It was now the intention of Jasper Tudor to await fresh forces from Clun, and then march upon Hereford, without attempting to besiege the Castle of Wigmore, hoping to crush Duke Edward before he could receive aid from the Earl of Warwick.

We found the gracious Duchess had already heard of our success the day before, and we received her dignified congratulations. She then gave us communications she had received from her son, Duke Edward, who had intended first marching to Ludlow, but, from the tidings he had received from our advanced outposts, was now determined to march to meet the Welsh army. He had sent word to the troops under my father, Sire John de Guyse, Sire Herbert of Crofts, Sire Howell Powell, and other leaders, to join their forces with his on the line of the trackway between Kington and Leominster; and he left to his trusty follower, Robin of Elsdune, to organise, as he best could, a force at Wigmore, which might hang upon the rear of the Welsh army as they advanced from Knighton and Clun.

Two whole days we now passed within the Castle, during which we collected a considerable number of veteran dependents of the house of Mortimer, who had seen many a bloody field, but whose bows and spears had been laid against their cottage walls, as if their days of adventure were over. But these hours of leisure soon passed away, and a messenger arrived from Duke Edward's camp on Kingsland Field to inform us that he should await there the onset of the Welsh, while a scout from Knighton brought the tidings that Jasper Tudor had this time led his army by Presteine. His army was calculated at over twelve thousand men, but a large proportion were badly armed, and but few armour-bearing knights in the field.

In less than an hour the archers and men-at-arms of Wigmore were assembled in the great courtyard, when the Duchess herself bade us God-speed. Leaving a sufficient garrison for the Castle, we were soon in full march for Avemestry, the village whither my father and the Lord of Crofts had marched the day we arrived at Wigmore. It was nearly dark when we reached this village, and learnt that all the troops collected there had moved to Kingsland, where Duke Edward had set up his standard, surrounded by his whole army, with the exception of our reserves.

Billmen

The bill is a polearm weapon used by infantry in medieval Europe. The bill is similar in size, function and appearance to the halberd, differing mainly in the hooked blade form. Bill-men were English soldiers who were armed with the bill.

The dawn of the morning of Candlemas Day (1461) aroused us from our rough quarters in the village of Avemestry, and before the sun had risen we had marshalled our troops. I then rode for the camp of Duke Edward, to communicate to him our exact position with three hundred good men and true, and the arrival of the Welsh army on the hills of Shobdon. As I rode forward on a sturdy pony, with "Roan Roland" led behind me, the fog cleared from the valley, and the gloom was passing into a morning's twilight, indicating the rising of the sun. Suddenly a wailing voice rose among the hills, and a noise as of people stamping came through the air; my companion said it was the "creening of the Welsh," and, on listening to the mysterious sounds more attentively, I heard distinctly the warlike notes of the Welsh march I had heard on the harp in the great hall of Hergest.

Hergest Court.

Manor house, now farmhouse and sub-divided into two tenements. Reputed to have been built c1430 for Thomas Vaughan; on the site of an earlier house but largely remodelled during the C17 and C18 and further altered during the C20. Part sandstone rubble and part close-studded timber framing with wattle and daub infill, part shingle clad (to south-east side) Welsh slate roof. Source; https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1081747

The sun rose as I rode upon the field of Kingsland, when a magnificent sight met my astonished eyes. At the eastern extremity rose the pavilion of Duke Edward, above which waved the Plantagenet banner, and on the right and left were the tents of the knights and gentlemen who were now gathered together in front, while a flourish of trumpets announced that the Duke and his retinue were now sounding to horse. Duke Edward was arrayed in splendid armour, across which hung a rich golden baldric studded with silver roses. Behind him were two heralds, and pursuivants clad in their peculiar livery.

In front of the pavilions were drawn up in battle array some 6,000 foot and archers, all armed with bows or cross-bows, and pikes, or short double-edged swords, while troops of horsemen galloped across the field. Among the various groups I recognised the flags and devices of many esquires and gentlemen who led their vassals and tenants in this quarrel. Here floated the Swan of De Guyse, and my heart beat when I saw on the far left the red Talbot of De Brute. On the right was the Dolphin of Howell, and the devices of Scudamore, Baskerville, Bromwich, and many others.

Sire John de Guyse rode by the side of the Duke, and his dark complexion and deeply marked features were a strong contrast to the fair face of the distinguished youth, who looked as much a king's son as the other a tried warrior.

The Duke's quick and stern eye, for no one had a sterner eye in battle, glanced towards me as I rode up on the gallop. He gave me a look of recognition and approbation, while he bid me wait until he had discussed some points in question with the knights around him.

The chivalrous spirit of Duke Edward urged him to challenge Jasper Tudor, the Earl of Pembroke, to the ordeal of personal combat, to be waged first with the lance or battle-axe, and afterwards with swords and daggers, until the death of one or other of the combatants. None of the knights to whom he referred encouraged the idea, as, whoever might gain the victory, battle between the forces, now so near to each other, would be certain to ensue. The Duke was not to be persuaded, so it was determined that I should carry his challenge, accompanied by one of the heralds.

The heads of the Welsh columns were now seen advancing on the western side of the great plain; they displayed a few banners, and as there was little doubt that the Earl of Pembroke led the van, the Duke commanded me to lose not a moment, but to ride with the herald bearing a white flag, and to give his solemn challenge to deadly combat. The herald rode in front, displaying the white banner, and I followed, riding slowly across the plain, passing several corps of men-at-arms, until we reached a knight cased in bright steel armour void of ornament, with the exception of a collar of the order of St. David of Wales. His herald displayed the banner of the Earl of Pembroke. The knight's visor was up, and he had a dark sullen look and a swarthy complexion. On his left hand rode an elderly knight with visor up, whose good-humoured expression contrasted forcibly with the stern bearing of Lord Pembroke; his helmet was bruised and dinted, and behind him rode a pursuivant with the banner of the Tudors. The face was that of one who had been extremely handsome in his youth, and indeed it was that face and form which had attracted Catherine of France, the widowed Queen of Henry V.

I had little time for observing more, as the Earl of Pembroke rode forward to receive the message from Duke Edward of York. On the herald's proclaiming the challenge to mortal combat, first by sounding his trumpet, and then in a loud voice, I rode up and threw a mailed glove of the Duke's in front of the charger of Jasper Tudor. His pursuivant was about to raise it from the ground, when the Earl shouted to him to let it lie, and said in response, "Return, Sir Esquire and Sir Herald, to your master, and say that Jasper Tudor declines to meet a beardless boy with sword and lance. Such questions are not to be settled by the death of babes or infants, but by the valour of bearded men. It were better for him to return to the care of his mother until mayhap we drag him thence to answer for being in arms as a traitor to our Lord the King!"

Enraged at this want of courtesy to my noble master, I said something about the fall of knighthood and of honour, when I was told by a knight near at hand to ride back from whence I came and bear a civil tongue lest perhaps I might return with cropped ears and a slit tongue to them that sent me. I turned to hurl an angry defiance in the teeth of the speaker, when I saw, underneath a bassinet or steel cap which had no visor, the heavy features and sinister countenance of Sire Andrew Trollop. Shaking my gloved fist in his face and shouting "Traitor!" I gave the spur to "Roan Roland," not a moment too soon, for at a loud signal of this treacherous knight a shower of arrows followed me, and my days would have been numbered but for the good shirt of mail I wore beneath a leather jerkin. Fortunately my horse was uninjured, and the herald was untouched.

Duke Edward received the reply from the herald, given in somewhat modified terms, in silent contempt, but he was much exasperated at the traitorous and un-knightly attack upon his esquire.

The sun had now risen above a dark bank of clouds, which stretched across the eastern sky, and we witnessed a strange appearance in the heavens, which I have never seen before or since. Some say it was a "delusion" caused by the clouds, others say it was a "miracle," but the sun rose as three separate suns, each as large as the other, and so continued for the space of half-an-hour. The appearance was hailed by the shouts of our assembled army, also by the loud cries of the Welsh forces, who were still marching on to the western plain.

How little had I realised the scenes on a field of battle! I had imagined that we should shoot flights of arrows and advance pikes, and charge with knights and mailed men on war-horses, and cut and slash, and wield our battle-axes, and the battle would be won; but the field of Kingsland was obstinately contested from sunrise to sunset, and every yard of ground was fought for, for hours together.

It was a slow, surging, struggle for life and death, varied by occasional charges of horsemen and knights as the leaders thought fit, and I have ever thought that, had it not been for the clear head and splendid qualities, as a general, of the youth the Earl of Pembroke sneered at as an "infant," the battle would have been lost by us. Although Duke Edward evinced great personal courage whenever there was a sign of the troops giving way, he remained standing for an hour at a time, giving directions through his esquires, and watching the movement of every corps. At the close of that long and eventful day he exposed his life again and again in terrific charges into the very thickest of the Welsh forces. Neither did he ride his war-horse during the earlier part of the day, but galloped to and fro on a stout palfrey to various parts of the battle-field, directing attacks or repelling the onset of the ever-advancing Welsh, who at one time nearly surrounded us; nor was I, or the other esquires, engaged in the mêlée for some hours, not until towards the close of this great struggle, as we were engaged in carrying messages and rallying the weary; neither did I ride "Roan Roland", or he would have expired from sheer exhaustion before the fight was over. He was led, like the Duke's charger, behind the great pavilion, and I rode across the field again and again, on a stout Welsh pony, till he was killed under me, and then I ran or walked until I caught another, there being no lack of steeds without riders.