Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

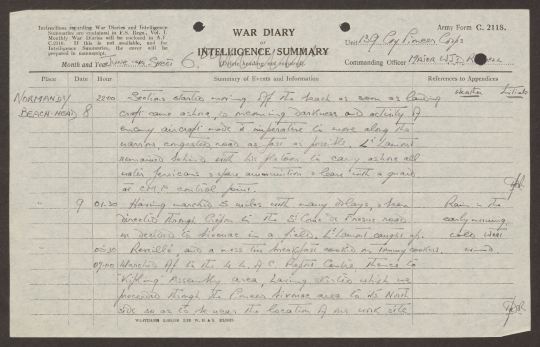

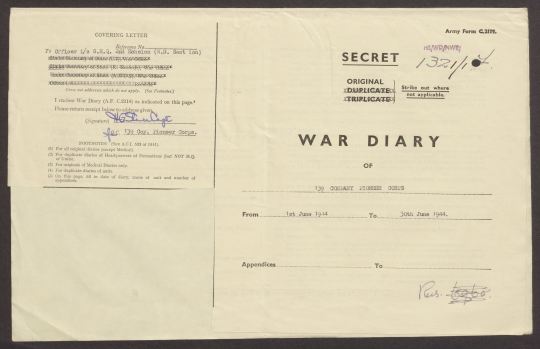

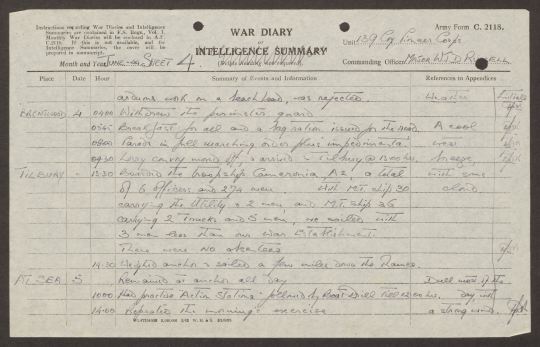

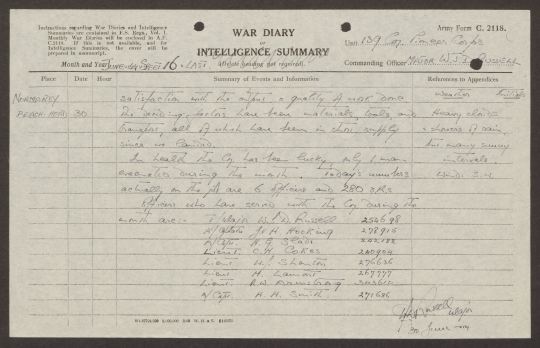

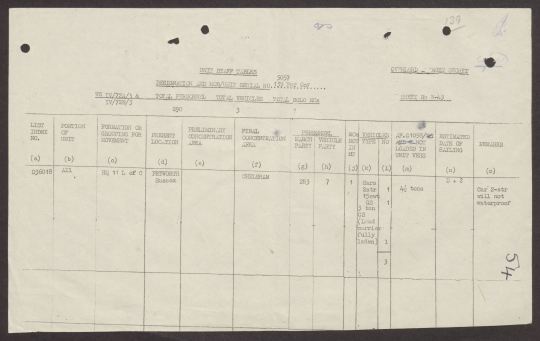

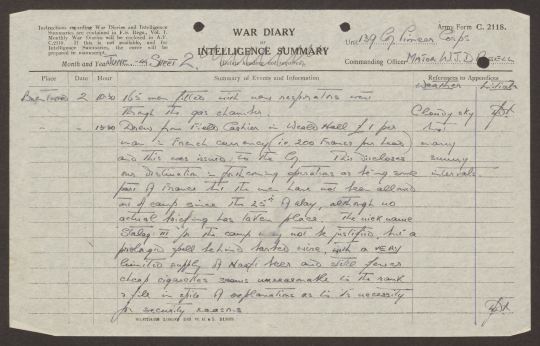

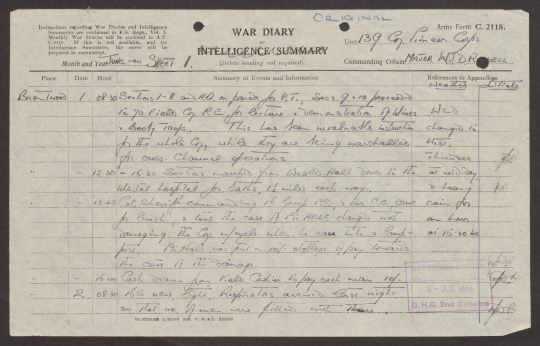

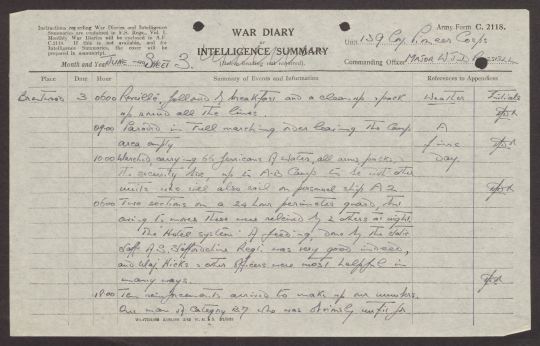

Jack Weaver’s Commanding Officer Diaries. Dad (Jack) was a Corporal with 139 Pioneer Company during the D-Day Landings. These diaries describe in detail the experiences of our Father and his part in the Landings. Dad was a Painter and Decorater and Part - Time Fireman in Leominster. Let no one forget them.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leominster’s Victorian Water Supply.

The Pinsley Brook in Vicarage Street prior to being piped in the 1970s provided great entertainment for a young child. The Brook had been diverted by the monks hundreds of years earlier where it fed fish ponds and acted as a drain. It powered three mills and ran under the (still currently existing) 12th century monastery infirmary building, part of which was a reredorter or toilet for the monks.

The Pinsley Mill was rebuilt and looked just like this in the 1960s, but it was semi-derelict.

https://catalogue.millsarchive.org/pinsley-mill-leominster

The Pinsley Brook of 1860 should have been piped. It was a breeding ground for disease. It was used for washing clothes in Vicarage Street. By 1960 it was clean and full of aquatic life. The brook flowed slowly parallel to Vicarage Street and across the entrance to Hampton Gardens. It was crossed by a lovely narrow arched red brick bridge further along Vicarage Street. The bridge led to a very narrow lane along which there was a terrace of very small Victorian houses. Hampton Gardens had been built from red bricks to match the houses around it. However, not built nearly so well as our Victorian ancestors had done. By the 1970s whole sides of houses were collapsing.

It was possible to catch crayfish, minnows and bullyheads (Bullheads). There were eels and very occasionally a Trout. Someone decided to erect a metal fence on concrete posts to block access to the path which ran beside the Brook. It was also an attempt to prevent access to water. The fence was promptly pulled down in places. If you followed the Brook westwards you were in the countryside in less than five minutes. Here the Brook was bordered by ash trees and weeping willows with roots wallowing in the water. Running parallel to the stream was the much larger River Kenwater.

Can you imagine this? Walking along a narrow path with unspoilt streams flowing either side of you with trees and bushes lining the route. At the end of the path there was a wooden style. Once over this a whole vista of lush meadows opened out, accessed by a beautiful naturally arched stone bridge. It was later replaced by an ugly metal and concrete one.

If you followed the brook in the opposite direction there was serious fun to be had. Once the stream passed Brook Hall it disappeared into an open tunnel which flowed underneath Broad Street. Despite passing the Brook Hall hundreds of times for over 20 years I never passed through the front door. By crouching under it was possible to continue to follow the brook for several minutes before arriving at the other end of the tunnel. We were perhaps using the same route as Monks had done in the past.

The Waterworks Museum writes the following about the gradual improvement in Leominster’s water supply.

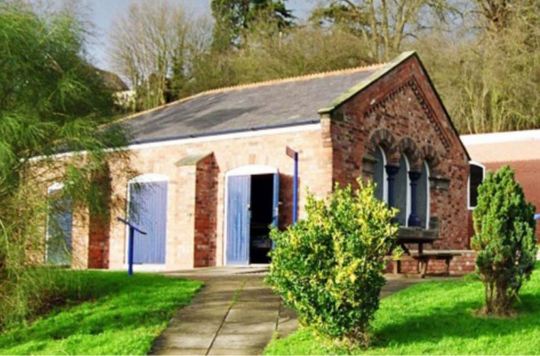

Tangye House; ex-Leominster's water-pumping station.

In the 1860s Leominster, an important market town in Herefordshire, endured several epidemics of typhoid fever from contaminated drinking water.

Many of the more affluent traders had their own wells in their gardens but also cesspits.

Poorer people took their water direct from the Pinsley Brook.

The epidemics reached such a level of attrition amongst the adult population that the Government directed the Town Council to provide the townsfolk with piped, potable water.

Money was raised through a Government loan by Mr Tertius Southall, a distant relation of the founder of the Waterworks Museum, Stephen Southall, and the waterworks building was constructed. It housed a steam engine and pump (later discarded with no records remaining) and was built above a known aquifer.

Quite quickly the water level in the aquifer was brought too low to use and water was piped in from some distance.

In 1990 the waterworks building was due to be razed to allow the extension of a business park in the town.

The Museum negotiated with the developers, dismantled the building with the advice of Avoncroft Museum, and reconstructed it on the Waterworks Museum site.

The roof support is of particular interest being an early wrought steel structure.

The building is now called the Tangye House and is home to the 97 litre Tangye horizontal diesel engine and other displays

In Leominster, people took their water from public pumps or directly from the river, while the richer townsfolk had their own private wells. It was not until these became infected by sewage and the rich people began to die that anything was done. A waterworks was only constructed in 1865 after a typhoid epidemic in which 38 people died, in the building that is now the Tangye House at the Museum.

Source: https://www.waterworksmuseum.org.uk/portfolio-view/tangye-house/

In many accounts of life in the Victorian Workhouse it is recorded that all inmates, including, children drank beer every day. In early Workhouses men were allowed up to three pints a day. Farm labourers would take jars or pots of beer or cider with them for liquid refreshment during the long days of work. Visitors or guests to average Victorian family home would be offered beer or wine. In most cases these were watered down especially in the Workhouse. This was not true of pub ale which was far stronger than the ale available on public sale by the 1930s. It is interesting that we have slowly but surely returned to the stronger alcohol drinks which became legal in the late 20th Century.

Many of you will know the reason for Victorians at all social levels avoiding water. Before piped water was installed in Leominster in 1867 water was obtained from shallow wells, which were liable to contamination, although many 17th Century reports on Leominster record the high quality of the water.

In Leominster like many other towns a water carrier would collect water from the river Lugg or Kenwater in order to sell it at half a penny a bucketful. It is extraordinary that river water was thought to be ‘clean’ enough to drink. Relative to well water, it was. Leominster was flooded regularly, and this enabled all kinds of sewage to pollute any wells, let alone what was thrown into wells.

After a cholera scare and thirty-eight deaths of townspeople from typhoid in 1864, the dangers of water from wells and springs were clear. In 1867 Leominster invested £8000 in constructing wells, pumping station, reservoirs, and pipework to supply the town.

Water was pumped into two 200,000 gallon reservoirs at Newlands drive from near the railway station. A further £5000 was spent on sewerage system.

The following article describes glowingly how much better Leominster’s water was by the end of the 19th Century.

The town is situated on the old red sandstone formation, and slightly above the valley of the river Lugg. The strata passed through were the surface-soil, consisting of about 6 feet of compact and nearly impervious red clay; a bed of river-gravel a few inches thick, forming the water-bed of the valley, on a level with, and no doubt communicating with, the river itself 200 yards distant; and below this, red and blue marl, with occasional lumps of sandstone rock for the remainder of the distance. No considerable supply of water was found below the gravel stratum, but that which found its way into the well through the fissures in the lower marl was of a remarkably soft character. A collecting drain was therefore made in the gravel for 150 yards in a direction away from the river. The supply of water was found to be ample in the very dry season 1869-70, and is much in excess of any probable requirement of the town. The quality is excellent, and is always clear and bright, requiring no filtration.

The water is pumped direct from the well into the supply reservoir, which is about 140 feet above the well and three-fourths of a mile distant in a direct line, and it passes from thence into the mains for distribution. The pumping station is at the well; there are two high-pressure engines of a nominal power of 12 horses each. The annual cost of pumping, including labour, fuel, and materials, is about £230. The area of the district is about one mile in length by three-fourths in breadth. About 800 houses are now supplied for domestic purposes - very little for trade purposes. The quantity of water pumped is about 100,000 gallons per day for all purposes. The water is supplied direct from the mains without cisterns. The supply is constant and adequate. The charge is 1s. in the £ on the net rateable value; no extra charge for water-closets.

Extract from Littlebury's Directory and Gazetteer of Herefordshire, 1876-7

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leominster prepares for Nuclear War.

James Garrett is the author at the heart of this Post. He describes in detail Leominster’s preparations for Nuclear Attack during the Cold War. Many of us will remember those ludicrous information programmes on how to prepare in case of a Nuclear attack. Taking shelter under the stairs or even a table were seriously advocated.

An earlier Post describes the much more thorough and realistic preparations in Leominster during World War II. The measures taken then were aimed at saving hundreds of lives.

During the Cold War the aim it appears was to save eleven lives. These eleven were presumably going to restore the services after the bomb. Hopefully, they had enough supplies for several years as above ground nothing would have survived. The area would also have been dangerously radioactive for decades to come. Russia is building an enormous dome over Chernobyl 30 years after a radioactive leak.

James now describes the preparations for Nuclea r War with warranted scepticism.

The Leominster Bunker Part of Britain's Nuclear War Government System

The elderly residents of Arkwright Court, a sheltered housing complex in Church Street, Leominster, would be among the first to know a nuclear war was imminent. That is, if they were to observe a group of 11 people entering the usually-empty basement beneath their homes. The basement with 18" thick walls and a 9" thick concrete ceiling is equipped with water, food and fuel supplies, an air filtration system, kitchen, operations room, generator and sophisticated communications equipment. The II would have left fate to look after their families and friends as they descended into the basement, otherwise known as Leominster district wartime control room, 'The Bunker'. They include the council's chief executive, Geoffrey Robson, who would be designated wartime district controller. If, because of the devastation caused by a nuclear attack he was cut off from higher authorities, Mr. Robson would have life and death powers over everyone in the district. Even if communications were unaffected, he would still wield a frightening array of powers on behalf of the government. His colleagues would include (in 1986) council treasurer Len Lewis (deputy controller), planning officer Chris Campbell (responsible for food supplies), housing officer Mike Clayton (homeless), chief technical officer John Berrett (devastation clearance), environmental health officer Dennis Fothergill (sanitation) and Mike Preece (fuel). Their job would be to operate rest centres and billets for refugees and the homeless, burying the dead and controlling the spread of disease, distributing food to the hungry survivors, clearing highways and attempting to maintain essential services such as water. With the aid of the police and armed forces they would also be responsible for maintaining a semblance of law and order.

These thankless - if not impossible - tasks would be repeated by similar groups throughout the country. Leominster's bunker is part of a nationwide chain of control centres - either planned or already in existence - for local authorities, the military, central government and BBC. Its purpose is specifically - and solely - to ensure that the government would survive a holocaust - even if little else did. Therefore, claims that the bunker is equally designed for the management of natural disasters such as flooding are inaccurate. The council itself has said the bunker will remain an empty shell until war threatens, and it would therefore be unusable in a civil emergency.

It is worth noting that no provision at all is made for sheltering the general public from the horrific effects of nuclear war. At local level, Hereford & Worcester County Council's plans are to establish so-called 'community executives' which would run parishes and town wards if contact with the district council bunkers were cut. These executives would be 'authorised to act on behalf of the district controller in times of isolation, to maintain the life and morale of the community within his local control.' This statement, made to me in early 1983 by the county council's deputy emergency planning officer, Terry Radburn, conceals an astonishing, disconcerting reality. Such local executives - under the command of ‘community leaders', would assume dictatorial powers over their fellow citizens. By March 1983 no community leaders had been appointed, but that situation may have changed. If appointments have been made - Mr. Radburn said 'retired military people and schoolteachers - a cross-section really' were the sort of people, he sought - their identities are a secret to most people and their role has never been the subject of public debate.

Leominster district is unlikely to be affected directly by a nuclear explosion. None of the military installations in the area seems to be of enough importance to be subjected to nuclear attack. However, Herefordshire would in no way escape unscathed. The prevailing winds would carry deadly radioactive fallout over the county from obvious targets like the nuclear power stations on the Bristol Channel or the docks at Avonmouth and Barry. Untold numbers of people would certainly die. Thousands of hungry, frightened refugees from devastated regions to the south, north and east would stream into the county. Mr. Robson and his staff would have to try to look after them. Not easy, with food and water desperately short, and hard-pressed medical staff unable to cope with the demand for dwindling supplies of medicine. The futility of attempting to cope with the aftermath of a nuclear holocaust has led growing numbers of people and organisations to denounce civil defence as a cruel confidence trick. The British Medical Association, representing the country's doctors, pointed out that a one megaton nuclear attack on one city would overwhelm the resources of the entire national health service. Most realistic scenarios assume a nuclear attack on Britain would be in the order of 200 megatons. Rather than ensuring that it would continue to function after a nuclear war by developing bunkers, the government should be engaging in direct talks with the Russians on abolishing nuclear weapons. Genuine steps towards nuclear disarmament are far more important than the recruitment of local dictators.

James Garrett

The following article is taken from the Hereford Times 2000, written by Bill Tanner.

Once thought vital to the region's survival, the controversial concrete bunker beneath Arkwright Court, Leominster, now appears as out of date as the logic that inspired it.

The five main nuclear powers have confirmed a 'commitment' to eliminating their atomic arsenals. Although largely symbolic, the gesture was hailed as a landmark in the cause of a nuclear-free world.

But things were very different when the Arkwright Court bunker was built back in the early 1980s. The threat from atomic attack was ever present, and Herefordshire, like all other areas, was expected to prepare for such a strike.

As the only official fallout shelter the bunker would have housed council officials chosen to run selected services. Known as an 'emergency control room', thick walls and a heavily reinforced door housed communications kit and power supplies.

Not everyone welcomed the bunker. Public protests, including marches, pickets, petitions, blockades and even a book greeted proposals to spend some £70,000, including Government grants, building it.

As the cold war thawed over subsequent years, the facility's function was frequently called into question. Options for alternative use ranged from a social centre to underground offices.

But the then Leominster District Council maintained the shelter as a 'co-ordination centre' in case of disaster. By 1994, the town's civic trust was offering access but warned there was little to view beyond a ventilation system and telephone line.

In 1998 the bunker became the responsibility of Herefordshire Council and has effectively been empty ever since.

A spokesperson for the authority said the shelter was being looked at as a site for short-term storage but admitted that 'we don't need it anymore'.

l Although Arkwright Court was the county's only official nuclear shelter, provision for a similar facility exists under Hereford Shirehall. Plans were also put forward as late as 1988 for a bunker beneath Brockington, the present county council HQ.

Source; Hereford Times. Bill Tanner 2000.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hop - picking before mechanisation.

How could picking hops for 12 hours a day in all kinds of autumn weather for six weeks be in anyway considered enjoyable? It was, in part, ‘needs be’. There were few opportunities for working class rural people, especially, women to earn extra money and along with their children. My mother took all three of us children hop picking in the 1950s near Weobley. My older brother and sister both had their own cribs to earn money. They were aged ten and eleven. The cribs were 9ft long and 2ft deep. The picked hops were dropped into the crib. Twice a day a Busheller would empty the crib and count the number of bushels. A bushel was a standardized wicker basket. Each bushel was the equivalent of 8 gallons of water. An average picker would harvest 25 bushels each day and was paid a shilling a bushel or 5p. As a five-year-old I was left to play with the other toddlers. We never strayed far as each hopyard had its own ‘bogey man’ waiting to kidnap you. Well that is what all the ‘mums’ claimed.

To a small child being penned between 25ft high hop plants was rather scary. Not unlike the giant plants in Jack and Beanstalk which reached the sky. The smell of hops always brings back happy memories, it cannot have been such a bad time. It also a time when a family pulled together with a common interest, to earn money. We were also fortunate to be living locally with a warm bed and dry house to return to. 1960s mechanization of hop picking was about to replace the need for large numbers of casual workers at harvest time.

No one expected to end the picking season with pockets full of money but every little helped. When I first started blackcurrant picking in the early 1960s the pay was 5p a 1lb . This was enough to buy a loaf of bread at the time. However, it would have taken over an hour to pick 1lb blackcurrants. Blackcurrants are probably my favourite fruit to this day. The daily weight was entered on your card at the end of the day. All pickers were expected to bring their own stool to sit on. Sometimes old wooden crates were turned on their side, they were ideal. No one was paid until the picking season was over. Those weighing your fruit would pick through the currants to remove any leaves, stems and unripened fruit to make sure you were not over paid! The row of plants you had picked was also checked. If it was decided, you had skipped the harder to pick fruit you would be told to start the row again. By 1970 I was able to earn £50 a week of 12-hour night shifts at the Bibby and Baron plastics factory in Leominster. Picking blackcurrants would have been ludicrous. ‘Pick your own’ was also in its[AW1] infancy bringing an end for the need for large numbers of fruit pickers.

During the summer months work at Dale’s Nursery was not as well paid but far more enjoyable. Growing and tending Chrysanthemums was a pleasure. There was also plenty of overtime on weekends and no income tax to pay. It was not illegal. Registering at the Labour Exchange as a student exempted you from tax. A few years later students had to claim income tax back but pay it up front.

After World War II if you needed transport it was motorized. Sometimes it was a tractor with a trailer. The ex-World War II canvased top army truck transporting us to the blackcurrant fields was luxurious. Not only was there protection from the elements but even benches to sit on, although children were still expected to sit on the floor. There were no men, just women and children. I was now old enough to go picking without family. The music in the fields which Alec refers to had been replaced by transistor radios. The volume was turned to almost maximum as there were no mini earphones in those days.

There were a few Gypsy families but not in the same numbers found hop picking. It must be said that local people were far less positive about Gypsys than Alec’s Pre-World War II experiences suggest. My impression is that ‘travelers’ has become a term to cover all people who do not follow the traditional sedentary existence. The 1970s saw the rapid growth of ‘hippy’ style travelers. Travelling for them was not a tradition but a life style choice.

No food or drink was provided for the pickers. The vacuum flask had arrived and sealed plastic containers to keep sandwiches fresh. Then were ‘Smith’s Crisps’ in sealed packets. Only plain flavoured with a blue sachet of salt ready to be added. Ready salted crisps were not available.

Today Farmer’s complain loudly that British born people will no longer do the work. They are constrained by the money Supermarkets and thus customers will pay for fresh food. It needs a concerted effort by an organization like the N.F.U. to improve working conditions for all and demand higher prices as a consortium. Supermarkets will always attempt to divide and conquer. Nevertheless, it is very unlikely farmers would be able to recruit enough workers. Times have changed and not many people would be prepared to work outdoors for long hours in all weathers whatever they were paid.

I think Alec would have been pleased with the growth of real ales in the 21st Century given his final paragraph.

Its time to let Alec Haines to take you back to Pre-World War II Leominster.

September was the month when the hop picking season began. For six- or seven-weeks whole families including children worked very long and arduous hours picking hops from Monday to Friday. This hard work had to be done so that the children could be clothed for the winter, coal could be ordered, and the balance carefully kept ensuring that the family had some means of survival in the cold months ahead. About a dozen hop yards circled the town within a walking distance of 4 miles. At 4.00 a.m. a large exodus of people moved from Leominster in all directions, usually in complete darkness, to get a good crib and a good picking area of hops. A crib was made out of crude timber about eight feet in length and four feet in width with 4 pole corners, some cross members, and then the whole covered inside with sacking which was positioned so that it formed a long draping interior into which the hops were picked.

Picture the very early start to the first day: complete darkness. candles in a jam jar placed on nearly every crib, one on each corner. The candles flickering in the jars just gave enough light to recognise perhaps the four, five or six people picking the hops into the crib from the long hop bines.

At the end of the first day that crib was your very own until the hop picking finished, no one else could try and claim that crib.

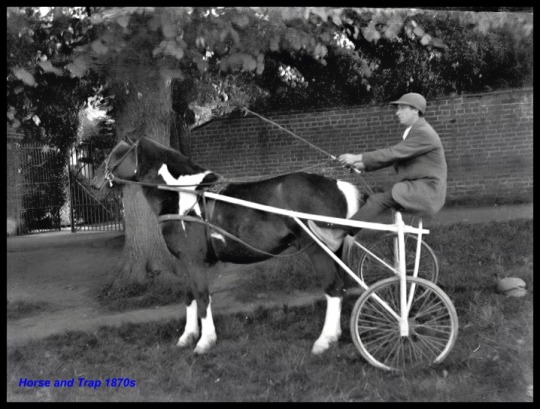

After the first day of hop picking then horses and wagons conveyed people to the hopyards, starting from town at 7.00 a.m. The wagons for Ivington bury and The Park would leave from the Toll House at the top of the Ryelands Road exactly at 7.00 a.m. When the chimes of the Priory Church struck that hour the two horses to each wagon would push forward with their loads of men, women and children. Anyone who was late of course, had to walk out carrying all their days necessities with them.

On one of those loads was a lady who was wearing a black fur coat, no doubt given to her by the lady of the house for whom she did the weekly washing. She looked resplendent in this coat every morning but in the early part of October she would have looked rather more like a white ghost when she arrived at the hopyard for the frost on those foggy mornings would have turned the coat completely white.

Mrs. Winnie Morris relates how she and her friends at the crib would pick away furiously until the crib was full and then prepare the breakfast whilst they were waiting for the busheller to come and take out the hops. A good wood fire was prepared from wood sticks out of the hedgerows, and out would come the eggs and bacon, bloaters and kippers, the big black iron kettle would be boiling away, probably for others to fill up their teapots as well. Often with many hop pickers even a frying pan was not needed at all. they had the method of frying bacon by twisting the bacon round a stick, putting it over the top of the wood fire and then catching the falling fat onto slices of bread. This was very eagerly awaited as the treat of the day by "the young children. Bloaters, kippers and herrings would also be fried over the wood fire but probably placed on two

sticks over the burning embers. Herrings were often put into brown paper and then placed just on the outside of the fire as it died down; these would slowly cook and be a tasty tender treat at the next meal break in early afternoon.

No perfumery house in France could match, such a beautiful smell as that which wafted down through the hop yard and had the following ingredients. woodfire smoke, frying of kippers, bloaters, herrings, eggs and bacon, the hops. and the Sulphur that had been newly sprayed on the hops. All these ingredients mixed up together and in various places throughout the hopyard gave you a smell which you would never again find on this earth it went with you to the grave. How sad therefore it must have been for the very many families who could not afford to fry those foods but worked on hard all day with just bread and jam, not even the bread with margarine on it, just jam. There were very many families in that situation. Maggie Prim has spoken of the period when she and her children and friends picked hard.,11 hours a day at her crib over a period of 51/2 weeks and received a total of £7.00, not much for at least 5 adults but as she said, "It was a Godsend".

The Busheller was not the most popular man in hopyard. He with two other labourers would arrive at about 9.00 a.m. and start bushelling. The bushel was a rather long elongated basket with two handles. He would eye the crib and if there were too many leaves in the sample he would ask for those leaves to be removed. It depended on his fairness as to how many sarcastic remarks he received whilst this was being done. Someone usually asked him if he attended his father and mothers' wedding. Someone else remarked that dark glasses would improve his eyesight. The number of remarks depended entirely on how heavily he pushed the hops into the bushel basket. He was always being accused of putting his elbows in to squash them even more. There was nothing to be said after the last full bushel was taken out - then he entered in your receipt book and in the farmer's book the quantity of measured bushels. This process was repeated about 3.00 p.m. in the afternoon and soon after 5.00 p.m. the wagons arrived to take the families back home.

In practically every hopyard there were two cribs set up, for the missionaries, and Leominster Cottage Hospital, manned by volunteers and to a greater degree by the people in the hopyard who perhaps would be waiting for the busheller or waiting for the wagons, and who had a little time on their hands. They would pick hops into these cribs and in so doing they raised considerable sums of money for these worthy causes.

Several gypsy caravans would be parked on meadow land near the hopyards, the same gypsy families returning every year to pick fruit and then to pick hops. Their children would eventually get married, so the gypsy families and their caravans - horse drawn of course - multiplied in numbers. These were kind friendly people, their caravans in spotless condition, with beautiful ornaments in the windows, horse brasses gleaming and all copper and brass utensils glistening. With the evening sun now setting many of them sat around their individual outdoor fires with probably a rabbit or two in the pot and no doubt a swede or two from the adjoining field. Two lurcher dogs that had caught the rabbits in the first place were now lying near the re hoping that their master would remember when the bones had cooled a bit, and hoping that he might miss a little bit of meat between the rabbit's breast bone. The master's wife has probably done the washing and is now hanging it on a line tied to a tree and the caravan, wisely taught by her mother always to observe from which part of the compass the wind is blowing. She hangs then, up wind of the fires. Tomorrow morning, they will be about, well about before 7.00 a.m. for there are some mushrooms that will need picking for breakfast from near the farmer's orchard. Whilst he is there a few cooking apples would come in handy also. Just as well he helps himself to a few pounds of potatoes for he knows that he should have a few perks before those "townies" start their daily raids after seven o'clock m the morning. The gypsy families move on to help with other crops mainly. cider apple picking When one goes back to that meadowland, their home of six weeks, as peaceful and clean as the first day they came, no rubbish, no smell, just a little round ring of burnt grass here and there as if they were allotments for the fairies but certainly no sign of any rabbit bones.

In 1985 the genuine gypsy has not changed his clean habits, even though he now has a gleaming chromium plated caravan towed behind a shiny modern lorry. His sons may well be driving a Mercedes Benz car because welfare state has given him the benefits that are due to him. He is still prepared to "have a go" at anything and does not dabble in the small paying enterprises that his forebearers used to follow.

Unfortunately lumped together with the gypsies are another class of people called itinerants, but these are people who desecrate the environment, leave their rubbish, rags, and discarded metals wherever they park, be it highway, byeway or country Jane. A tree, or a wayside flower has no meaning to them for they would eliminate them from the glory of the Good Lord who gave them for man, beast and bird to see, appreciate and enjoy. It is certain that the itinerants and the tinkers could never live in harmony with the gypsies. The gypsy will always earn some part of his living from the land, the others will treat it only as waste land.

The hopyards also brought many a child screaming to their mothers for this the part of the season when wasps were very hungry, looking for a discarded 1am sandwich or an uncovered jam jar. Nice sweet apples were in the nearby orchards causing many small children to be unsuspectingly stung by the hordes of wasps that constantly flew over and around the cribs, the vinegar bottle and the bluebag were often used to help banish the pain.

There were human wasps too. For very many miles a man called Ellis would travel around the hopyards, even out to Little Hereford, selling herrings at twenty-four for a shilling (Sp), with a form of barrel strapped in front of him, the strong leather straps tied around his waist as well. Carrying over cwt of herrings, and calling in succession to every hopyard, he went through each one selling these herrings. When the barrel was empty, he refilled from a larger barrel in his small cart at the roadside, but, as five or six people have told me, this man often was hard pushed to sell any herrings in the late afternoon, for they were now beginning to look stale, and Ellis had been found peeing on them at the bottom of the hopyard to make them look fresh. No one in the hopyards would have had herrings for tea when they got home at 6 o'clock. How different the price of herrings today -75p each.

Walter Morgan remembers as a young boy going out to pick hops at Watkins, The Park, Ivington. His parents were picking hops next to a man who had a large family. As soon as Mr. Watkins left the farm buildings with the cart and the busheller, to come into the hopyard, that was the opportunity for him to ask the young Walter to go and take the big black kettle and fill it up wit h cider from the hop kiln, where the drying of hops took place. Walter says that when Mr. Watkins met him then no doubt he thought that the young lad was going to fill the kettle with water. Not so, for there was plenty of cider in the buildings for Mr. Watkins' favoured friends. So he filled the kettle with cider and struggled to this man for the deal had to be honoured by both parties, Walter's part of the deal was to have a cigarette. The kettle of cider was not handed over until he received a cigarette, then the delighted little man would place the cider on an old orange box near to his stool and drink the whole of the cider through the spout of the kettle. When that was finished, the kettle was filled with water, placed on the fire and that cider tainted boiling water added a peculiar taste to the brew when that was poured out for tea.

Just after the Second World War, Yeomans' Buses travelled on their normal service routes through several of the villages and parishes in our picking areas, lvington , Monkland, Upper Hill. What a wonderful sight it must have been to see and then to hear one of their Radio Coaches come by these hopyards with its windows open and this lovely sound of music pouring out as it wound its way to the next village. Children heard this sound some way off and the whole of the hopyard children would rush to the roadside to see his wonderful invention, for most would not have had a radio at home and this sound coming from a bus was nothing short of a miracle.

At the conclusion of hop picking the payment for labour rendered took place. The farmer usually made arrangements to pay out on the next day and what a contrast! The hopyard people arrived in their best clothes with their baskets, purses and hand bags ready to receive their money. A few farmers had bottles of spirits to offer them a drink and then they cheerfully went back to the shops to buy something for themselves. Before hop picking they could only dream.

Today hop picking is done on a scale approaching high technology factory farming and all the hops are brought into the building by tractors. Only a few labourers are required, for everything is mechanised; indeed, many hopyards have closed, for the brewers use far less hops than years ago. The Gods of Chemistry and Biotechnology have replaced the hops with inferior products. The beer drinker knows to his cost and to his palate that nothing can replace the taste of hops in his beer.

[AW1]

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

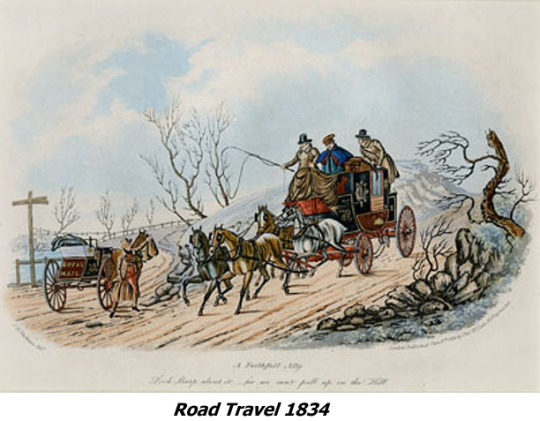

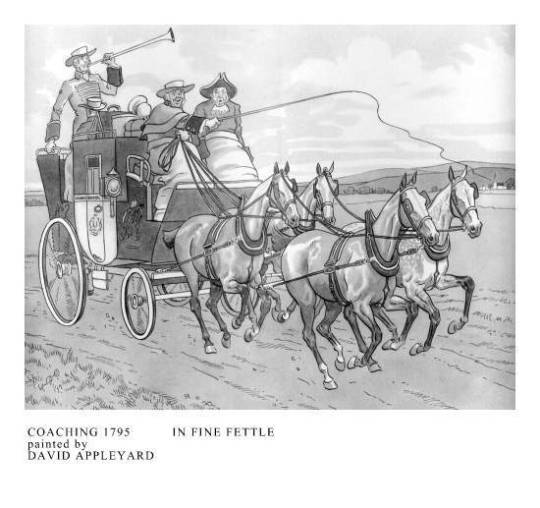

Travel by road in the early 19th Century.

Historical sources which give plenty of factual details are often more informative. It is much better to know how much it costs to travel rather than bland statements like ‘road travel was not affordable and was very slow’. Better to know, how much it cost and how long the journey took.

The following article focuses on transport links in the Leominster district circa 1800 to 1900. It is also explaining how people and goods could travel to all parts of England and Wales.

I did not record the source of the article used in this Post. If anyone recognizes it, please let me know.

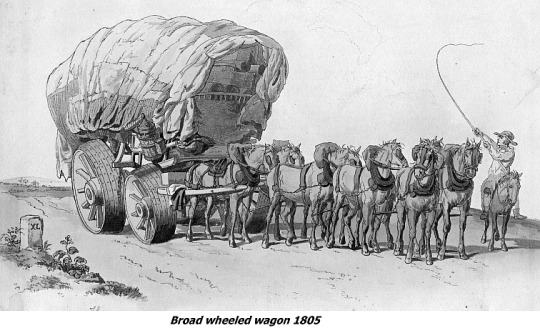

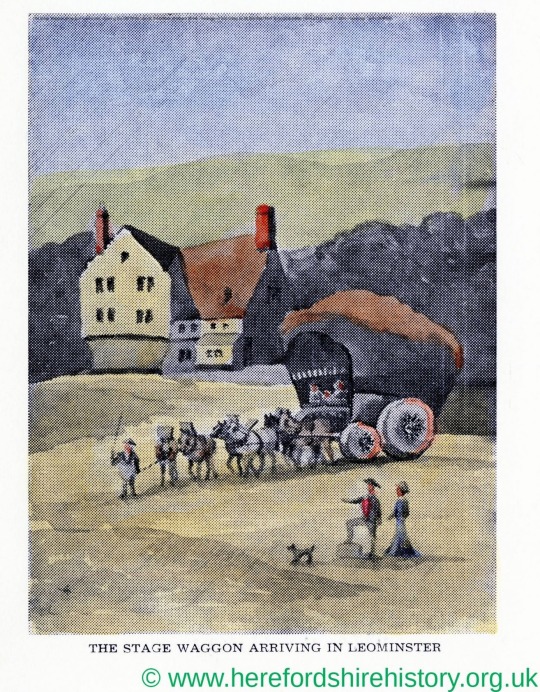

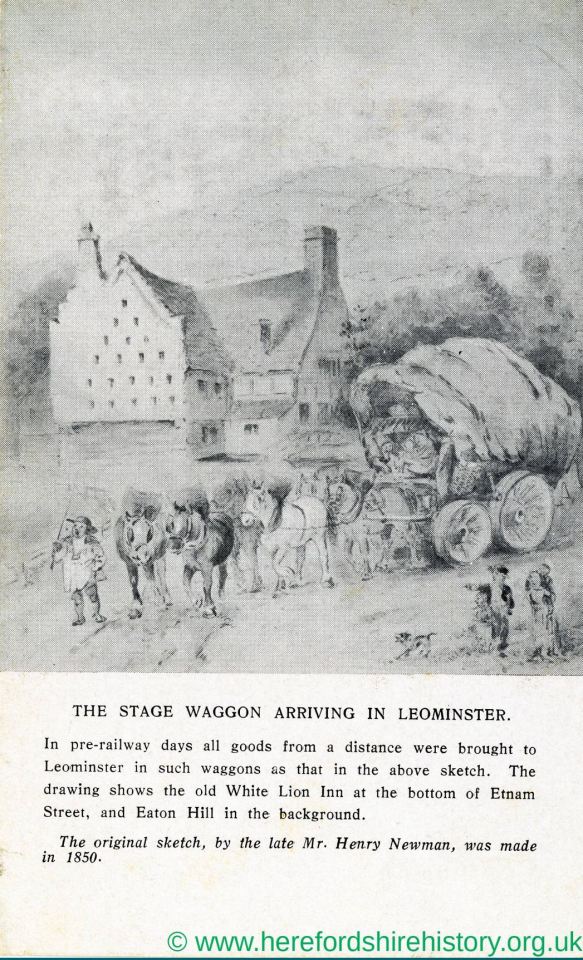

On the last mile of its journey from the direction of Worcester, a large stage waggon, drawn by a team of six horses, lumbers past the White Lion Inn, with a dovecote built into its west wall, into Etnam Street.

There were no navigable rivers near Leominster, although it was not for the lack of trying. Attempts to make the River Lugg navigable had been costly mistakes. The diversion of the Pinsley Brook by monks centuries earlier had been far more successful.

The Leominster Canal did operate for over 60 years until its closure in 1858. It was only 18 miles long and did not connect to other waterways. It was used to transport coal but never made a profit. In hindsight it would have been wiser to invest in better roads.

The White Lion holds many good memories for me. My mother and father would take me for ‘pop and crisps’ in the 1960s. The White Lion was a good choice as children could sit out in the garden. Children were not allowed to enter a Public House. Even more special was its location. The railway ran past the end of the garden. A steam locomotive could pass at any time. A glass of fizzy lemonade, a packet of crisps and a steam train! What bliss.

The author of the following article is unknown to me, although it does include an entry from the Hereford Journal published in 1809.

Massively built waggons could carry heavy loads of up to eight tons and ran on wheels with rims nine inches wide with sixteen-inch hubs. Wheels of this size were needed to cope with the severe jolting caused by uneven road surfaces. These were reduced to a quagmire in wet weather when the fragile, badly-maintained surface frequently broke up. The waggoner had to walk beside the lead horse for he could be heavily fined for riding on the horse or the waggon. Freight charges varied between ls. 6d. to 2s. per hundredweight. Travelers who could not afford the stage-coach fares sometimes travelled under the canvas cover amongst the bales of freight. Like the stage-coach routes, a similar web of waggon routes covered the country, with staging posts to change the horses.

In the example which follows a Waggon leaving Worcester on Tuesday arrived at Brecon on Sunday morning via Bromyard and Leominster.

Some idea of the extensive network and the time the waggons spent travelling from London can be gleaned from this extract taken from an advertisement in the Hereford Journal of 18 January, 1809:

The proprietors of the Cambrian Waggon Company beg leave most respectfully to inform the public that they have established a regular conveyance to and from London, Oxford, Cheltenham, Glocester [sic], Worcester, Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Halifax, Saddleworth, Huddersfield , Wakefield, Sheffield, Birmingham, Ludlow, Chester, Shrewsbury and all parts of the North of England and Scotland. For Herefordshire , Monmouthshire and all parts of South Wales and the South of Ireland, their London waggons set out from the Cambrian Warehouse, Bell Inn, Smithfield, London every Saturday morning and will call going out and coming in at the Dolphin, Oxford Street, Pack Horse Inn, Worcester Tuesday night, Cambrian Warehouse Bromyard Wednesday morning, Hereford Thursday morning, Hay Thursday night, Brecon Sunday evening, Llandovery Monday morning ... and arrive at Carmarthen Tuesday Noon, from where all goods for Cardiganshire, Pembrokeshire and the south of Ireland will be regularly forwarded. All good intended for this conveyance from Manchester., Birmingham etc. are particularly requested to be directed and forwarded from Manchester and Stockwell from Birmingham to the Pack Horse at Worcester and also from Glocester [sic] and the clothing country, by Page to the Cambrian Warehouse Hereford and return via Bristol return from the Cambrian Warehouse Brecon on Saturday evening, Abergavenny Saturday night and arrive at the Moderator Warehouse Newport on Monday Morning, when all goods for Bristol, Bath and the West of England will be regularly forwarded by the Moderator boat to Bristol and from there by different carriers.

In 1801 North's Cambrian Waggon Company called at the Talbot Hotel in Leominster, but by 1808 they had a warehouse in Corn Square from where a network of other carriers radiated. Horse-drawn transport persisted until it was replaced by motorized delivery vans. As late as 1902, on market days a network of 39 carriers based at pubs in Leominster carried supplies to the surrounding villages, despite the penetration of the county by the railway. Very rural areas like Leominster could not be well served by the sparse railways infrastructure and stations built across Herefordshire. Road transport always remained the means of travel in rural areas.

My wife and I held our wedding reception at the Talbot Hotel in 1975. At that time, it was owned by Mr. Burke. It was not difficult to imagine it full of travelers in the 19th Century. The low ceilings and timber framed rooms and open fire places added to the medieval feel. Public Houses and Hotels in Leominster were hit hard by the arrival of railways. Instead there was a rapid growth in Railway Pubs and Hotels in urban areas.

Until the arrival of the railway, stage-coaches carried passengers around the county. In 1808, Broome, Whitney and Co. operated a twice-weekly service from Hereford through Leominster to Shrewsbury on Tuesdays and Fridays, taking all day for the journey. Travelling inside, the fare from Hereford to Shrewsbury was £1 2s., and outside was 12s. A labourers wages were £12 a year. From Hereford to Leominster the fare was 6s. inside and 3s. outside; parcels were carried at 1d . per pound.

Assuming the journey from Hereford to Leominster took 8 hours it means the stage-coaches travelled a 7 m.p.h. on average. Clearly a coach with passengers and luggage could have attained much faster average speeds. A casual walking speed is 3 m.p.h. It gives an indication of how poor roads around Leominster were. Also consider these were the main roads, not the village tracks. It is also possible country lanes and tracks were in better condition as they were not being constantly battered by heavy coaches and wagons.

This all changed with the construction of the railways. The journey time from Hereford to Shrewsbury was reduced to an hour and a half by train instead of a whole day by stage-coach. It would also have been far more comfortable. We can never overestimate the changes brought about by the arrival of the railways.

0 notes

Text

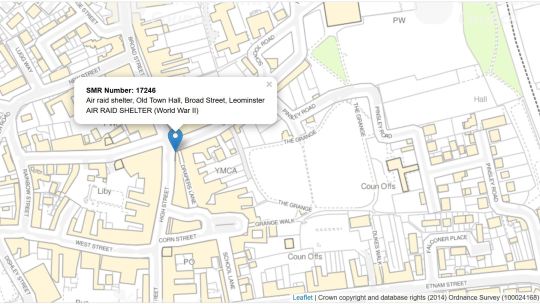

Leominster’s Air Raid Shelters.

We are constantly reminded of how indebted the ‘babyboomer’ generation is to those fighting the two world wars of the 20th Century. No other generation in British history has not be called upon to fight for their country. Many of us are now in our 70s. Add to this the rapid growth in the standard of living and the freedoms not available to earlier generations.

We should also remember that wars had huge impacts of the life of those left behind even in rural districts similar to Leominster.

The following information to be found on the Herefordshire.gov web site. It illustrates another example of how Town’s like Leominster had to prepare for the worst. Despite how unlikely it was that Leominster would have been bombed directly imagine the psychological impact in preparing bomb shelters.

Leominster’s siren which I remember so well from the 1950s and 1960s being used to alert part-time firemen of an emergency, was loud. Consider the impact during the war even if only for drills for the people of Leominster.

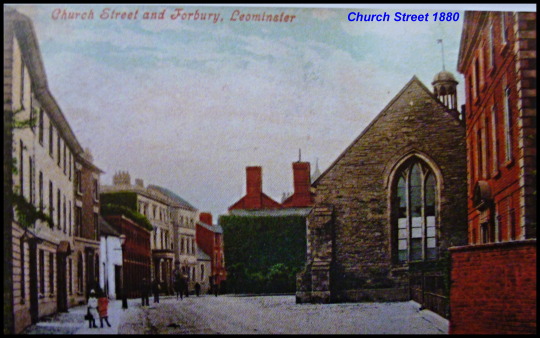

In October 1940, the cellars of the old Town Hall were converted into a basement air raid shelter for the use of 154 people. When completed, it was found to be very damp. Further investigation revealed water mains on two sides and a gas main on the other. As the cost of remedial work was too great, the shelter fell into disuse and was superceded by the two K-type shelters in Burgess Street and Church Street in November 1941. The Town Hall was demolished in the 1970s. Any trace of the cellars would have disappeared when the new library was built on the site in 1991.

General note: Correspondence and discussions on the provision of air raid shelters started at the outbreak of war and continued without any sense of urgency until May 1940, when France was invaded. Presumably the bombing of cities like Rotterdam provoked a sense of urgency and a flurry of telegrams between the Council and Birmingham Civil Defence HQ soon saw work commence.

By October 1940 three shelters had been completed in Leominster but people were advised to carry torches until lights were completed. It was also pointed out that the shelters were to be used by people "caught" in the street and not for sleeping in at night. One month later, "in view of recent events" (the London Blitz), it was thought necessary to provide picks, shovels and crowbars so anyone trapped could tunnel out. Shelter doors were kept locked and opened by a warden, or a glass key case could be smashed.

Type KB public air raid shelter (brick and concrete) for 50 people, completed in February 1942. This was a replacement for the basement shelter under the Town Hall, which became uninhabitable due to damp. The shelter was purchased for £1 by Bill Bengry and G.D. Bengry after the war, and was demolished by them in the 1960s. A brick service bay is now built on the site.

Bill Bengry was a very well-known and successful Motor Racing competitor in the 1960s.

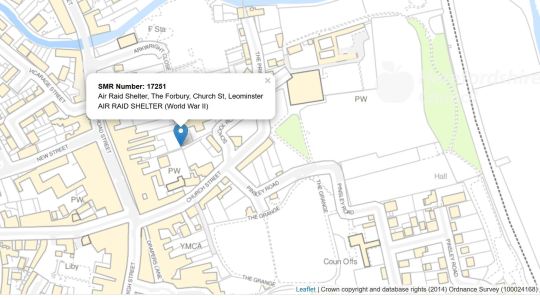

Air Raid Shelter, The Forbury, Church St, Leominster

Grid Reference

: SO 497 592

Parish

: LEOMINSTER, HEREFORDSHIRE

A "K" type public air raid shelter for 50 people, constructed in February 1942. It was situated on the paved area in front of The Forbury in Church Street. It was one of two replacements for the Town Hall basement shelter which became uninhabitable due to damp. It was dismantled after the war in the demolition programme. The construction materials were brick and concrete.

Old Cinema Site, Corn Square, Leominster

Grid Reference

: SO 4971 5903

Parish

: LEOMINSTER, HEREFORDSHIRE

The basement of the old cinema in Corn Square was converted into an air raid shelter for 66 people. The work was completed in October 1940. Part of the cinema itself housed the NAAFI.

The Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI) is an organisation created by the Government in 1921 to run recreational establishments needed by the British Armed Forces, and to sell goods to servicemen and their families.

NAAFI’s greatest contribution was during the Second World War. By April 1944 the NAAFI ran 7,000 canteens and had 96,000 personnel (expanded from fewer than 600 canteens and 4,000 personnel in 1939). It also controlled ENSA, the forces entertainment organisation. In the 1940 Battle of France alone, the EFI had nearly 3,000 personnel and 230 canteens.

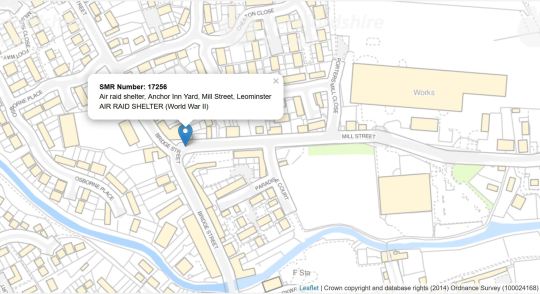

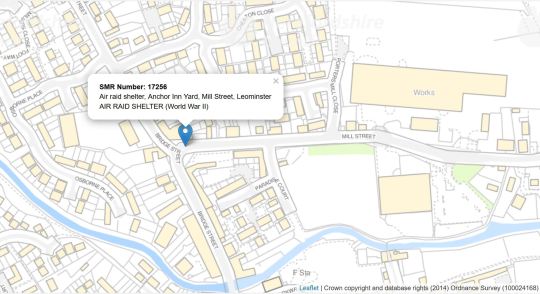

Air raid shelter, Anchor Inn Yard, Mill Street, Leominster

Grid Reference

: SO 4952 5950

Parish

: LEOMINSTER, HEREFORDSHIRE

A Type KA public air raid shelter holding 50 people, constructed in February 1942 in Anchor Inn Yard, next door to the Hop Pole Inn in Mill Street. The shelter was demolished after the war in the general programme. The landlord's offer to buy the shelter was accepted on the understanding that he would demolish it himself at his own expense if the Highways Authority needed to widen the A49 road. Not surprisingly he declined, and the Anchor Inn was itself demolished in an A49 widening scheme. The construction materials of the air raid shelter were brick and concrete.

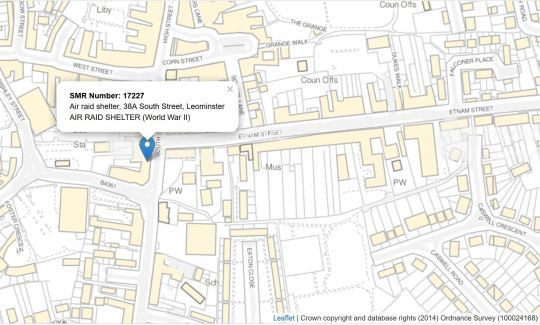

Air raid shelter, 38A South Street, Leominster

Grid Reference

: SO 4961 5888

Parish

: LEOMINSTER, HEREFORDSHIRE

Basement air raid shelter built in 1940. The cellars of the shop were reinforced with concrete to form a shelter for 73 people. The property is now the premises of estate agents Russell, Baldwin & Bright.

Air raid shelter, Black Horse Public House, South Street, Leominster

Grid Reference

: SO 4956 5871

Parish

: LEOMINSTER, HEREFORDSHIRE

Air raid shelter built in February 1942. Type KB (brick and concrete) holding 50 people. The shelter was demolished after the war in the general programme, despite efforts by the landlord of the Bowling Green pub (as it was then known) to purchase it.

Air raid shelter, 42 Vicarage Street, Leominster

Grid Reference

: SO 4948 5934

Parish

: LEOMINSTER, HEREFORDSHIRE

A KA type above-ground public air raid shelter for 50 people. It was built of brick and concrete and completed in February 1942. It was built on the site of allotments which the army had been using to practise building trenches. After the war, it was bought as a warehouse for a paraffin business. It was subsequently converted into a bungalow. Apart from the addition of windows and an extension at the rear, the shelter is in its original condition.

I remember this Bungalow very well. We were living in Hampton Gardens at the time (circa mid-20th Century), a matter of few hundred yards away. It was occupied by a single elderly lady, who had been a nurse. It is difficult to believe that only a few years earlier soldiers were practicing the building of trenches on that very site.

Air raid shelter, Anchor Inn Yard, Mill Street, Leominster

Grid Reference

: SO 4952 5950

Parish

: LEOMINSTER, HEREFORDSHIRE

A Type KA public air raid shelter holding 50 people, constructed in February 1942 in Anchor Inn Yard, next door to the Hop Pole Inn in Mill Street. The shelter was demolished after the war in the general programme. The landlord's offer to buy the shelter was accepted on the understanding that he would demolish it himself at his own expense if the Highways Authority needed to widen the A49 road. Not surprisingly he declined, and the Anchor Inn was itself demolished in an A49 widening scheme. The construction materials of the air raid shelter were brick and concrete.

https://htt.herefordshire.gov.uk/her-search/monuments-search/search/Monument?ID=17246

Sources and Further Reading

1. <1> SHE18932 - Document: Bassett, A. 1996. Defence of Britain Project record form: Basement Air Raid Shelter, Old Town Hall, Broad Street, Leominster.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leominster Cricket Club 2nd XI in the 1950s.

Another short story of 1950s Leominster by Alec Haines. Irresistible because it is another episode from the many quirky stories of English Cricket. A ‘History of Leominster Cricket’ would make a very interesting read. Also note that the players only ran to the Pavilion during torrential rain. Many matches on the Grange were played despite constant light rain. Most players wore spiked cricket boots and not lightweight trainers.

Source; Leominster's 20th century characters and its poacher 1988

by Alec Haines (Author)

During the 1950's cricket as usual was proving to be a very exciting game both in Leominster and the surrounding villages.

Leominster 2nd eleven were playing an away game at BRAMPTON BRYAN one Saturday afternoon during this period of time. Russel Cooper, the captain, who always carried his large rolled umbrella with him to all the away matches decided on reaching the club pavilion that all players must change quickly into their cricket gear as the weather forecast was 'heavy rain' for that afternoon. The game commenced promptly on time. After one hours of play very heavy rain forced the players to run into the pavilion, with the rain beating down it was decided to bring the tea interval forward by half an hour in the hope that the game perhaps could proceed afterwards. The club bar quite naturally remained open during the whole time the game was not in progress. Tea having been taken the rain continued to pour down from the heavens, so the two captains had no option but to abandon the game. But unknown to Leominster’s captain two younger members of the side had put inside his umbrella three or four handfuls of sawdust and had fastened the securing strap properly. All the players now changed, proceeded to their transport, one of BENGRYS BUSES, and awaited the arrival of the captain. With very heavy rain falling he duly arrives at the entrance of the bus, "Well lads," he said, "I am going to make a final inspection of the wicket”. He marches some ten yards, unties the securing strap, opens the umbrella above his head and the whole pile of sawdust falls out onto his head and all over his slightly damp clothes. He turns back immediately to the transport, sits in the front seat of the bus and orders the driver to make straight back for Leominster. This was the first and only time that a cricket team from town had ever driven past so many pubs on the route and had never sipped one drop of beer on the way home. The first time also that the cricketing fathers had arrived home to see their children going to bed, not as on some rare occasions when they would arrive home just before their children were having their Sunday morning breakfasts.

0 notes

Text

Agricultural Servant employed near Weobley. Bondage and the Mop Fair.

Bondage and the Mop Fair

Deals were struck within a bondage system whereby men provided a female worker, or bondager, to labor on demand for the employer in exchange for such things as the cottage rent. In the overpopulated rural south, agricultural laborers were mostly hired by the day, piece, or other short period, as they were abroad. Low wages - paid in cash or kind - resulted in wretched diets, bad work habits, and the low productivity that formed a vicious circle. Work days were often incredibly long, the jobs heavy and dirty, and the relative isolation of farms served as a disincentive to those attracted by higher wages and greater conviviality in urban places. Crimes such as incendiarism and animal maiming that were associated with social resentments were rife until they began to decline after mid-century.

Researching a family tree is enormously rewarding. The Weaver family charts are included in the earliest of my Posts. It opens the door to many other avenues of research. George Weaver was born in 1835, our Great, Great Grandfather. He was an agricultural servant.

He was born in 1835 in Pembridge and died in 1883. In 1851 he was employed as an agricultural servant at the Court in Mansell Gamage in Weobley Parish. In later life he was occupation was listed as an agricultural labourer. What was the difference? There are substantial differences in the conditions of service and employment contracts. Arguably a labourer was more senior with greater experience and was paid a wage. However, a servant’s terms of service had some advantages, but it did not include a wage. Some servants may have been given a notional payment at the end of their term.

Image of Mop Fair.

Unfortunately, in very many cases people were employed as servants up until the age 16 and then became labourers as their ‘owners’ let them go. I use the word ‘owners’ carefully as this was almost a form of slavery and was certainly feudal in its character. A more widely used term in feudal times would have been a serf. Unlike a serf, in theory you could leave your position but you would have broken a contract and thus the law. Also people were not forced to become servants as slaves were; in fact, there was huge competition to be appointed as an agricultural servant. As you may have already worked out George Weaver was 16 in 1851 and by the next census of 1861 he was an agricultural labourer.

George is living with the Jones family who have a 140 acre farm and employ a further five farm labourers but they do not count as part of the family. This is a clue as to why it was better to be a servant. Farming was very labour intensive, employing five labourers to work 140 acres seems extraordinary now.

A single servant like George would have lived in and bed and board would be part of the contract of hire. If married they would be provided with a cottage on the farm which The Court Farm had, although in 1851 it looks as though other Jones family members were living in the cottages.

Image of Mansell Court.-

Workers looking to be hired would attend a ‘hiring fair’ held in the local area and they advertised themselves as ready for work. Around Leominster they were known as ‘the Mop’. If you were skilled in one aspect of farming you would mark yourself out with a plait of straw for a thatcher or a crook for a shepherd. Women were assembled in a hall and the men in the streets. If you were selected you normally received a six month or year contract. You can see all the bonuses here for a servant, accommodation and food sorted and no longer a strain on the family. They also had security of employment for that period. A farm labourer had none of these advantages.

The term ‘Mop’ derives from the fact that each person was supposed to be carrying an implement to indicate the trade for which they were seeking employment and the mop was used by general domestic servants. Many people came from far and wide to take part and this encouraged another large group of people hoping to ply their services to the assembled crowds by entertaining them, feeding them and selling their produce.

0 notes

Text

Railways spelt end of the line for Grand Assembly Room

Railways spelt end of the line for Grand Assembly Room

An interesting article regarding the Lion Ballroom. My sister’s future husband worked at Alexander & Duncan’s in the 1960s, before becoming its owner. Despite going into the works numerous times, I was not aware of the secret history upstairs. A child in his early teens was occupied with so many other things. The Lion Ballroom and the associated buildings have a long and important place in the history of Leominster. We should be grateful to all those who worked so hard to preserve and restore it.

Ballroom dancing has an important place in the life of my wife and I. Mr Mann an excellent teacher at Green Lane Leominster Secondary Modern School taught us Ballroom Dancing in the 1960s. The lessons were every Friday evening in the main hall during the winter months. The music was provided by 78 records played on a wonderful 1940s Gramophone player. It was also the beginning of my love of vinyl records. The Hall like the rest of the school had been an army camp during World War 2. Although the school did have newer buildings housing the Science Block, Gardening and Music rooms.

ANYONE WITH STORIES ABOUT THIS SCHOOL PLEASE LET ME KNOW. Over 80% of Leominster’s children attended this school for two decades and yet there are no public records! Enter a search for Leominster Grammar School in Google and their hundreds of results Less than 15% of Leominster children attended this school. I attended both Schools and they were excellent in different ways.

It remains Leominster’s forgotten school.

Chris Upton’s article titled the ‘Lost Lion of Herefordshire ‘follows. It is both informative and entertaining.

Source:

https://www.birminghampost.co.uk/lifestyle/nostalgia/chris-upton-tells-tale-lion-6125548

We are well accustomed to an old building being described as a “best kept secret” or a “forgotten treasure” – it’s all part of good tourist PR.

All the same, it’s remarkable how, on our overcrowded and much scrutinised island, a building can go missing. Even if, as in this case, it is 60ft long and 22ft wide.

Such is surprisingly the case with the Lion Hotel in Leominster. Not so much the old hotel itself, since it stands in the middle of Broad Street and can hardly put on dark glasses on that account, but the Lion Ballroom behind it. Pevsner overlooked the room, and the Department of Environment removed it – despite an earlier listing at Grade II* – from its schedule of listed buildings.

Perhaps there are so many lion hotels – in a wide variety of colours – in this part of England that you can easily mislay one without noticing.

The Leominster Lion stands on the west side of Broad Street, the road that runs north-south through the middle of the town. The eponymous beast peering down from its parapet, looks more docile than its rampant counterpart at Shrewsbury, reflecting perhaps the more sedate pace of life for Herefordshire big cats.

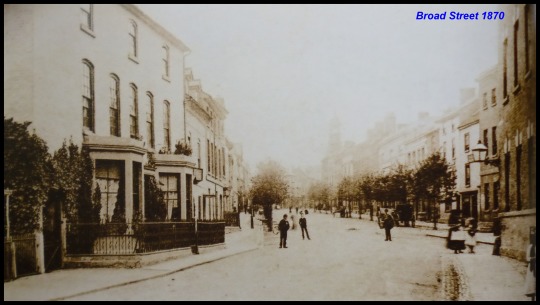

This was not always the case. The road concerned – variously called High Street and Broad Street – was once the busiest of thoroughfares. Head this way for Hereford and Bristol to the south, and for Shrewsbury and Liverpool to the north. And an east-west route, from London to the Welsh border at Kington, passed this way too.

As a result, a host of hostelries clustered along the length of the street, all offering food and accommodation to the weary traveller and hungry trader passing through the town. There were at least nine inns along here at one time, from the Waterloo Hotel at the top end to the Unicorn at the bottom. Only one of them survives as a hotel today.

There was a Red Lion on this site from at least the mid-18th Century, doubtless popular with the stall-holders and farmers frequenting the market outside. In the local press each successive lease-holder “begged the indulgence of his friends and the public”, and promised “excellent wines and liquors and unremitting assiduity and attention”.

But the Georgian coaching trade was about to transform Leominster into a major service station, and by the 1830s nine stage and mail coaches were calling at the Red Lion each day. The Red Lion did not have the monopoly, but it was by some distance the major coaching destination in the town.

Sales particulars from the 1830s show that the inn had a granary and stables for the horses, capacious cellars, a walled garden, a cider mill, and “numerous” bedrooms. Evidently the estate agent couldn’t be bothered to count them.

However, the reputation of a good coaching inn was not founded entirely on such passing trade. Its local good-standing was based on the presence of an assembly room, a place for cards and dancing and polite Georgian chit-chat. By the early 1800s the Red Lion had cornered this market as well.

It was when an ambitious Leominster lawyer by the name of James Thomas Woodhouse took over the lease of the Red Lion in 1839 that the hotel’s assembly room was turned from necessary amenity to star attraction.

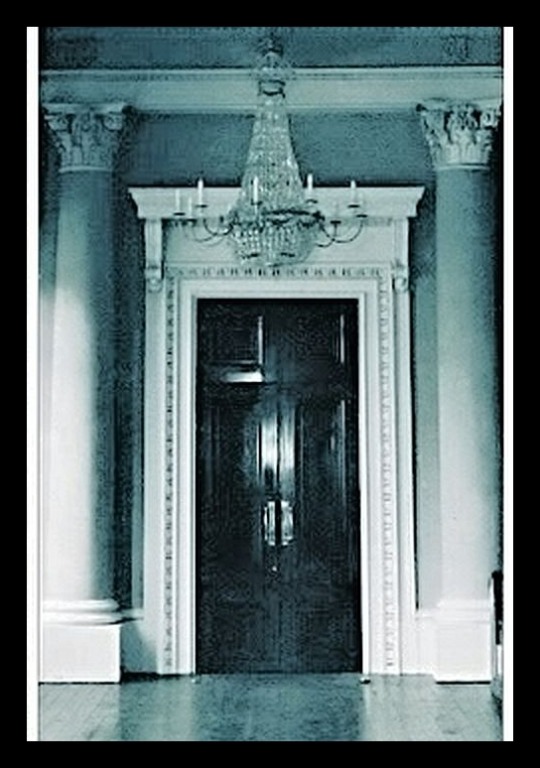

Woodhouse purchased the property next door in order to expand the hotel’s frontage and add a carriage-way and built a grand new assembly room at the rear. A local architect, John Collins, designed the room in fashionable neo-classical style, all Corinthian columns and candelabra. Leominster had seen nothing like it.

The new assembly room was ready for its first revellers by Christmas 1843, and a succession of balls, concerts and meetings made good use of it. But the truth was that the ex-Red Lion and new Lion Hotel and its assembly room had come just a little too late. The assembly was a declining fashion, the railway was approaching, and the coaching trade was about to be killed stone-dead. Even the styling in the ballroom, you could argue, was now out of fashion. What you have on your hands, sir, is a dead lion.

Ironically, one of the last grand balls ever held at the Lion (in December 1853) was to celebrate the opening of the Ludlow to Hereford railway line. For the hotel too, it was shortly to be the end of the line.

After some years of disuse, in 1861 the building was taken over by a Quaker ironmonger – Samuel Alexander – and became the Lion Implement Warehouse. The former assembly room served as his rather grand showroom, and it continued in that guise for the next century or so. By the 1960s many had forgotten just what the place was, and that included Nikolaus Pevsner. The plasterwork was falling off, and the grand entrance doors had made their exit elsewhere.

However, there’s to be no unhappy ending to this story, and we can celebrate an early Victorian masterpiece brought back from the brink.

With money from the district and town councils, and from the National Lottery, the Lion and its assembly room has been restored to its pristine best. It reopened in 1997. The age of assemblies may have departed, but there’s still a call for concerts and weddings and…er… karate classes.

Not quite what John Collins and James Woodhouse had in mind, perhaps, but there you are.

0 notes

Text

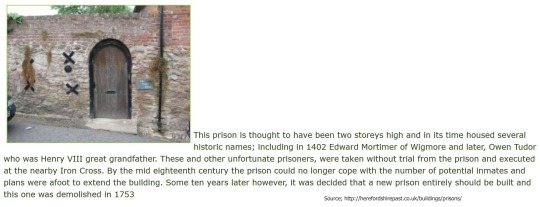

Forbury Prison, Leominster

Historic Environment Record reference no. 19552, Ordnance Survey grid reference SO 4972 5914

It is recorded that since "very early times" there had been a place in Leominster for the detainment of local offenders and captives. The building was apparently of two floors with a gaoler's lodge close by, and is said to have been within the West Gate of the Priory in Church Street. As the local Law Courts held their sittings in the Frere Chamber above the gateway, this arrangement would have been very convenient.

It is here that Owain Glyn Dwr is said to have held Edward Mortimer of Wigmore in 1402. After the decisive Battle of Mortimer's Cross during the Wars of the Roses in 1461, Edward IV used the prison to house Owen Tudor (great-grandfather of Henry VIII), David Floyde, Morgan ap Reuther and other men of note after he had defeated them. It was from here that they were taken, without trial, to the Iron Cross (HER reference no. 12129) and there executed.

In later years the prison was used to detain Catholic recusants, including the famous priest and martyr Father Roger Cadwallader. Quakers, Independents and other Non-Conformist religious members were also imprisoned here.

A Deed of Richard, Abbot of Reading, dated Thursday after the Feast of SS. Simon and Jude, anno XVII Richard II (1394), announcing the appointment of John Lunteley of Lucton to the life office of Gaoler of the prison, gives the following information on his salary and allowances:

"He shall receive in the hall of the Manor of Leominster his Victuals in Meat and Drink as the serving men do every day there. And moreover the said John shall receive every year during his life one Robe of the sort of the serving men and 4s for his salary, with all small profits belonging and due to the said Office."

By 1742 the Forbury Prison was too small for the number of prisoners needing to be housed and the Corporation appointed a Committee to prepare a plan for enlargements, with work to be completed by the following spring. In July 1752 the West Gate of the town, along with the Frere Chamber, collapsed but the gaol appears to have escaped any damage. The minutes of the Corporation Proceedings show that the gaol was still in use the following year:

"Tuesday, March 20, 1753

"Ord., That James Clark, Esq., have leave to pull down a part of the Stone Wall near to the dungeon in the Church Street, and to place the stone in the School Yard, and to take away the Rubbish that shall be occasioned therby, and not prejudice any part of the Gaol or said Dungeon."

The following month the Corporation condemned the Forbury Prison to demolition and a new prison was built in nearby New Street.

In 1897 Gainsford T. Blacklock in his book The Suppressed Benedictine Minster & Other Ancient & Modern Institutions of the Borough of Leominster(Leominster Folk Museum, 2nd Edition, 1999) wrote "As the overlord of the 'Peculiar' of Leominster, the Abbot of Reading maintained a Prison, as an adjunct of the local Court of Justice. On the south side of the roadway, just within the Gate, were the Gaoler's Lodge and the Abbot's Prison. The old Prison is now used as a Warehouse. The iron ring and staples to which the prisoners were fastened were until recently still to be seen in the lower part of the walls of the interior. Only a few courses of the masonry of the original front wall of the Prison remain, but the Doorway can be clearly made out.

"It was in this prison that Edmund Mortimer, the Earl of March, of Wigmore Castle, was confined by Owen Glendower in 1402. Mortimer, who was the grandson of Philippa, the daughter of Lionel Duke of Clarence, having a better claim to the throne, owing to his being a more direct heir than Henry IV, that monarch secretly rejoiced at his discomfiture, and refused the urgent requests of the Percies [sic] to ransom him, or to embark on any military enterprise for his release."

(Taken from Alec Haines, Leominster's 20th Century Characters and its Poacher, 1988, p. 56)

With thanks to Eric Turton of Leominster Folk Museum for information on this topic.

[Original author: Miranda Greene, 2003]

0 notes

Text

Leominster’s Victorian Racecourse

Leominster race course was active in the Victorian era. Two days were held annually in August or September. It is very likely it depended on when the harvest had finished. The race was held near to Etnam Street. Temporary booths or stands were built for spectators. The track was a mile in length.

The Victorian races or ‘plates’ as they were called included hunting horses bred locally, Galloways and ponies were the accepted breeds. This was not Ascot. The races were called plates as this was normally the prize for the winning owner as well as some cash winnings for the jockey.

The course was on the Broad, Etnam Street and racing was certainly a regular event post 1808 and was still an annual event throughout the Victorian era in some form. When enclosures took place the racecourse was left unchanged. Probably because the Gentry and local farmers wanted it to continue. It would probably have upset many local people. By the late 1880s the races were taking place in August. This was probably because harvesting was finishing several weeks earlier due to improved mechanisation.

The racecourse was lost on the construction of the Shrewsbury and Hereford railway. The rail line was constructed through the centre of the racecourse in 1853. This implies the course was actually at south eastern end of Etnam Street or very close to where the railway station lies today. This would have provided a large flat floodplain area which was used only for animal grazing rather than crops. The term Broad may well have applied to all the lower flood plain land on or near the River Lugg. Although steeplechases did continue beyond the arrival of the railway on a shorter course.

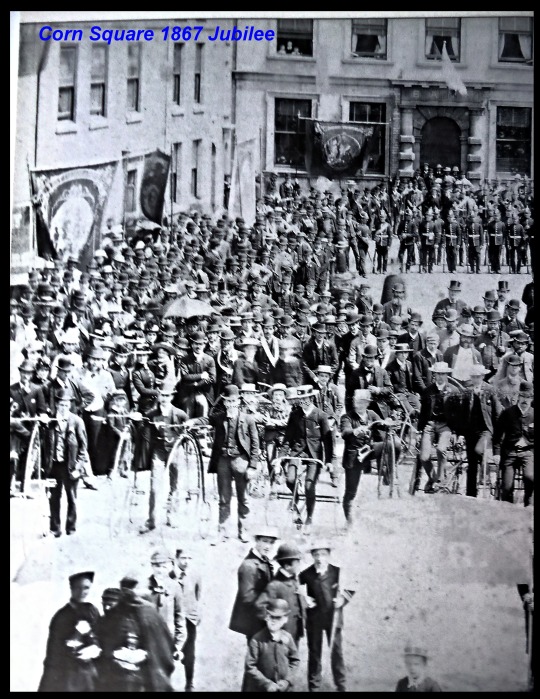

Earliest meeting: Wednesday 28th July 1790 Final meeting: Tuesday 27th March 1883 The Herefordshire market town of Leominster, close to the River Lugg, is located 12 miles north of Hereford. Racing was first staged in the town on Ernam Street, Broadway on Wednesday 28th July 1790 when a 3 race card included a Galloway race and a pony race. However, the feature race was for Hunters and consisted of three 4 mile heats. Eventually, after 12 miles of running, the race was won by Mr Honslow’s Gimcrack. The first-time results were reported in the Sporting Magazine was from a 2 day meeting on Wednesday 22nd and Thursday 23rd August 1838 on the racecourse on Eaton Meadows. After racing there was a firework display organised by Mr Baker, and Ordinaries were served at the Royal Oak Inn and Waterloo Hotel. Races continued intermittently for the next 45 years until the final meeting took place on Tuesday 27th March 1883.

Source:

http://www.greyhoundderby.com/Leominster%20Racecourse.html

0 notes

Text

Leominster’s World War II R.A.F. Wireless Operator.

Another opportunity to highlight one of the many individuals who are in danger of being overlooked by history. This poignant and important account can be found on the Leominster Scouts website. I can remember being fitted out with my first ‘ Cubs’ uniform in 1960. Mum walked me through the Grange and down the Pinsley Road to the Scout Hall. There were clearly far more important individuals who had preceded me. Fred Bassett was one of them.

Source; http://www.leominsterscouts.co.uk/digital-museum/1940-s/catalina/

Frederick James Bassett

Having joined the RAF Fred Bassett was assigned to 302 Flying Training Unit operating from RAF Oban.

On the evening of 12th May 1944 Catalina JX273 and its nine crew took off on a night training exercise.

Fred Basset was the Wireless Operator/ Air Gunner under the command of pilot David Clyne, a successful footballer in the Scottish League before the war. The intended route was via Barra Head. However, the aircraft was flying well off-course, realising the navigational error, the pilot endeavoured to gain height but when he had reached about 213m (700ft), the Catalina crashed into the side of Heishavel Beag on the island of Vatersay killing 3 crew including Fred Bassett

RAF recovery teams later broke up the plane and salvaged the engines but much of the wreckage remains intact to this day.

A memorial has been erected close to the crash site but it interestingly gives Fred’s initials incorrectly.

Fred Bassett is buried in Leominster’s Moravian Burial Ground, his wife Nora was buried alongside him in 1994.

I found this additional information following a little research.

Aircraft Accident Details

The Catalina featured here (JX273) was built by Boeing of Vancouver, Canada. Sometime after its delivery to the UK, this aircraft was assigned to 302 Flying Training Unit, then operating from RAF Oban (a flying boat base).

On the evening of the crash, the Catalina took off from Oban on the west coast of Scotland, fully loaded and with depth charges under each wing. The aircraft was on a night training exercise with a complement of nine persons, including the pilot and co-pilot.

The intended course was via Barra Head. However, the aircraft was flying well off-course, and was no longer above the sea, as the pilot believed. Realising the navigational error, the pilot endeavoured to gain height. However, when he had reached about 213m (700ft), the Catalina—which, by now, was over higher ground—crashed into the side of Heishavel Beag on Vatersay.

Aircraft Crew Casualties

Of the nine personnel on board, three were killed and the remaining six were injured. Those who died were:

Flt Sgt David Clyne, Captain

Sgt R. (Fred) Basset, Wireless OP-AG

Sgt Patrick Hine, Rigger (mechanic)-AG

Those injured were:

Sgt E. Kilshaw, 2nd Pilot

Sgt P. Lee, Navigator

Sgt G. Calder, Wireless Op / Mechanic-AG

Sgt Roy Beavis, Engineer

Sgt Ron Anstey, Wireless OP-AG

Sgt R. Whiting, Flight Mechanic

The survivors were taken by the Royal Navy to hospital in Oban. Near the foot of the hillside, stands a new memorial to those who died and to those who survived. The plaque on this memorial pillar can be seen below. Photos of the memorial pillar are available also at South Yorkshire Aircraft Museum.

Source; http://www.aircrashsites-scotland.co.uk/catalina_vatersay.htm

0 notes

Text

Street lighting arrives in Leominster.

My Grandmother lived in Ebbw Vale in South Wales. She was the mother of seven boys who were coalminers and two daughters. My mother was the elder daughter. Once a year we visited her and some of my Uncles. Their coalminers terraced stone cottages had no electricity or internal toilets. At night we used lanterns for light downstairs. At bedtime we used candles. It was the 1950s, not the 1850s. Granny Pep. cooked on a coal fired hearth. There were also gas street lamps which were lit by the Lamplighter. The lamps were lit to enable miners to go to work at all hours. They also carried lamps. There were several lamps hung on hooks by the back door. Uncle Tom, the eldest son, took me down a pit also using a gas lamp. Health and Safety officials are probably pulling their hair out right now.

Its possible Leominster was advanced in its introduction of street lighting in England. London was only legislating for the placement of street lighting in the early 17th Century. This was a response to fighting crime rather than health and safety. It only applied to the main streets, much of Leominster remained in the dark. The early lamps did not spread light very far. Toward the end of the 17th Century residents were also required to hang lanterns outside their homes after dark.

For centuries, rushlights were the poor person’s light-source of choice. You make them by repeatedly coating a rush in hot fat, building up the layers to create a rather scrawny candle. These long, gently-curving lights were balanced in special holders. To double the illumination, you could ignite both top and bottom (‘burning the candle at both ends’). Rushlights were still used in rural England to the end of the 19th century, and they had a temporary revival during World War II. Bacon grease was commonly used but mutton fat was considered best by some, partly because it dried to a harder, less messy texture than other fats.]A small amount of beeswax added to the grease would cause the rush to burn longer.

The expression ‘the game’s not worth the candle’ makes it clear that lighting a candle felt like burning money itself. The twenty minutes for which one rushlight lasted was a familiar unit of time and had to be exploited to the maximum. A housewife might have invited village neighbours over to share a rushlight for an interval of hurried darning.

Only the rich could afford a profusion of beeswax candles. In large households, a daily ration of candles was often included in employment conditions, and the fate of candle-ends was hotly disputed: they were the preserve of senior servants, who’d sell them on to supplement their wages.

Yet there was another, cheaper alternative. The tallow candle was made from animal fat, ideally sheep or cow, because ‘that of hogs … gives an ill smell, and a thick black smoke’. The art of creating the longest-lasting blend was very valuable, and in 1390 tallow chandlery was listed among the foremost crafts of London. Tallow candles had a horrible brown colour and made a dreadful meaty stink. Despite this, desperate people would eat them in times of famine for the calories they contained.

Apart from the unpleasant smell, the great drawback to tallow candles was the need to snuff. Their wicks had to be trimmed every few minutes or they smoked. And, in an age of candles, fire-light and timber-framed houses, accidents were common. Once in seventeenth-century London a servant named Obadiah illicitly took a candle up to his bedchamber. There it fell over and burnt ‘half a yard of the sheet’. But the quick-thinking Obadiah woke a fellow servant, and together they ‘pissed out the fire as well as they could’.