#A Clockwork Orange - 1971 - Dir. Stanley Kubrick

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Clockwork Orange - 1971 - Dir. Stanley Kubrick

#orange#t shirt#movie#stanley kubrick#a clockwork orange#Stanley Kubrick#70s movies#1971#Malcolm McDowell#alex delarge#movies#Adrienne Corri#Patrick Magee#Warren Clarke#John Clive#Michael Bates#Aubrey Morris#Miriam Karlin#Clive Francis#Michael Tarn#Carl Duering#ultraviolence#retro futurism#retro futuristic#studiohouse designs#A Clockwork Orange - 1971 - Dir. Stanley Kubrick

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Clockwork Orange (1971) dir. Stanley Kubrick.

#A Clockwork Orange (1971)#A Clockwork Orange#1971#70s#70's#alex delarge#Stanley Kubrick#Malcolm McDowell

893 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Clockwork Orange (1971) dir. Stanley Kubrick

266 notes

·

View notes

Text

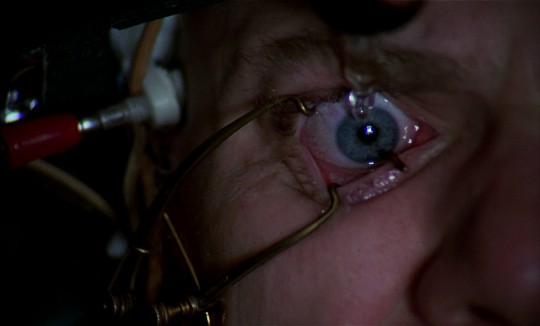

100 ꜰᴀᴠᴏʀɪᴛᴇ ꜰɪʟᴍꜱ

67/100 — a clockwork orange | 1971

dir. stanley kubrick ༄

#100 favorite films#a clockwork orange#films#cinema#movies#film#film frames#cinematography#film stills#cinephile#screencaps#stanley kubrick#film is not dead#film tag#film screenshots#film screencaps

985 notes

·

View notes

Text

⋆˚。⋆ ⋆A Clockwork Orange (1971) dir. Stanley Kubrick⋆˚。⋆ ⋆

#a clockwork orange#1971#stanley kubrick#1970s#70s#vintage aesthetic#colour palette#alex delarge#retro aesthetic#cinematography#movie screenshots#movie screengrabs#movie screencaps#movie frames#cinematography appreciation#movie#movies#escapism through film#the beauty of cinema#cinephile#1970s cinema#letterboxd#malcolm mcdowell#filmedit#kubrick stare#dystopia#art#painting#surrealism

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

A Clockwork Orange / 時計じかけのオレンジ Trailer dir: Stanley Kubrick (1971)

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

a clockwork orange (1971) dir. stanley kubrick

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

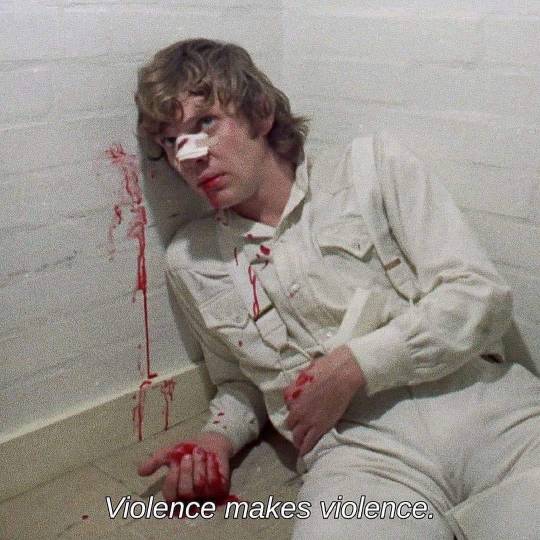

If... (1968, dir. Lindsay Anderson) / A Clockwork Orange (1971, dir. Stanley Kubrick)

#directors saw malcolm mcdowell in his twenties and said 'make this twink bleed in a corner'#and they were so right#if... 1968#a clockwork orange 1971#malcolm mcdowell

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top First Time Watches of 2024

I was tagged by @manganiello (a big thank you, even if I have the same answers as before)

Rules: post 9 of your favourite films you saw for the first time this year that aren’t new (2023/2024) but are new to you and tag 9 others to do the same.

Welcome To The Dollhouse (1995) dir. Todd Solondz

A Clockwork Orange (1971) dir. Stanley Kubrick

Opening Night (1977) dir. John Cassavetes

Teorema (1968) dir. Pier Paolo Pasolina

A Serious Man (2009) dir. Coen Brothers

Amadeus (1984) dir. Miloš Forman

The Adventures of Tintin (2011) dir. Steven Spielberg

In The Mood For Love (2000) dir. Wong Kar Wai

Starship Troopers (1997) dir. Paul Verhoeven

Tagging: @honeyglazedbabe @thiagodasilva @powerbottombrucespringsteen @kitc0nn0r @ancientcitystyle @kennyroyz @inamax @dickprints @jamieleecvrtis

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Clockwork Orange (1971) Dir. Stanley Kubrick Malcolm McDowell as Alex DeLarge

#a clockwork orange#1971#stanley kubrick#malcolm mcdowell#alex delarge#anthony burgess#1970s movies#70s movies#1970s#70s#seventies#milk bar#ultra violence#violence kink#statue

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

a clockwork orange (1971) dir. stanley kubrick

#a classic among not very good but still watchable cinema enjoyers#a clockwork orange#stanley kubrick#kubrick#cinematography#film#filmbro#cinema#malcolm mcdowell#1971

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Clockwork Orange - 1971 - Dir. Stanley Kubrick

#t shirt#movie#ringer tee#stanley kubrick#a clockwork orange#white#ringer#ultraviolence#droogs#Stanley Kubrick#70s movies#1971#Malcolm McDowell#alex delarge#movies#Adrienne Corri#Patrick Magee#Warren Clarke#John Clive#Michael Bates#Aubrey Morris#Miriam Karlin#Clive Francis#Michael Tarn#Carl Duering#rucking fotten#retro futurism#retro futuristic#A Clockwork Orange - 1971 - Dir. Stanley Kubrick

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Film #608: 'Barry Lyndon', dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1975.

I suspect that Stanley Kubrick, like Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles before him, has become one of those directors that it is difficult to enjoy. What I mean by this is not that they make films that are hard to like, but that they have become so lionised by the history of cinema that watching anything they've made starts to feel a bit like homework. With Kubrick in particular it feels like there is a 'right way' to enjoy his films, which is to say, to study them intently and thus not enjoy them at all. Even his broadest comedy, Dr. Strangelove (1964), has had most of its pleasure leached out of it by successive generations of film scholars avidly discussing it as high art, repeating the same stories about Kubrick's perfectionism over and over until the film basically ceases to matter - it becomes, in this form, just an object one can point to and declare genius. So, you can imagine that I went back to Barry Lyndon with a bit of nervousness. After all, this is a three-hour period drama, and the first film Kubrick had released after 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and A Clockwork Orange (1971). Was this going to be enjoyable at all? Or was it going to be a final exam?

This isn't the first time I've seen Barry Lyndon, according to my notebooks. That said, I think that my first viewing must have been a hazy post-midnight watch a decade ago, because I have barely any recollection of it. This is true of many of the films early on in the list, which is partly the reason why I'm writing these summaries/essays - so that I don't have to rewatch a film in order to reflect on it years from now. What I certainly didn't remember from that first viewing was the scope of Kubrick's vision here - how lush the sets and locations and costumes are - or just how much story and how many events Kubrick has crammed into the three-hour runtime. Nor did I remember how witty and engaging the film actually is.

In the 1750s, young Irish rake Redmond Barry (Ryan O'Neal) is incensed when his cousin, Nora, falls in love with the advantageous Captain Quin, and challenges Quin to a duel. After his victory, Barry is quickly persuaded to leave town to avoid the repercussions, leaving his mother Belle (Marie Kean) and taking refuge in the British Army. Here, life for Barry is difficult but respectable - after the death of a family friend, however, Barry deserts his regiment and tries to escape to a peaceful country. He poses as a British lieutenant, but this disguise is seen through by a Prussian captain, who forces him to join the Prussian army instead. When Barry saves this captain's life, he is honoured and, following the Seven Years' War, given a job as a spy in the Prussian Ministry of Police. This continues one of the dominant threads in Barry's life: that of playing both sides until he determines where the advantage lies. Unbeknownst to Captain Potzdorf, he schemes with the professional gambler he has been asked to spy on, and the two escape the country before the Prussian government can arrest them. The life of a gambler is Barry's introduction to noble society, although initially an undignified one, as Barry is often called upon to fight duels in order to collect outstanding debts. However, when he lays eyes on Lady Lyndon (Marisa Berenson), he sees an opportunity for legitimate wealth and privilege. Lord Lyndon's abrupt death means that before long, Barry takes the title of Barry Lyndon, much to the disapproval of Lady Lyndon's son, Lord Bullingdon (played for most of the film by Leon Vitali).

Lord Bullingdon is right to disapprove - despite the birth of a second son, on whom Barry dotes, the marriage is toxic, with Barry wasting his wife's fortune and restricting her to the house. Most of Barry's financial ineptitude is devoted to the attempts to gain a permanent title as part of the landed gentry. Barry's mother, reunited with her son, also pushes him to attain a title, although it seems that Barry doesn't really need any more encouragement. Barry's relationship with his stepson grows more antagonistic, culminating in an outright brawl during a concert. After this, Lord Bullingdon abandons his family's estate, seeking to make his own way in the world. Tragedy strikes when the younger son is thrown from a horse which is to be his birthday present, despite the boy's promise that he will not ride the horse unsupervised. Barry is inconsolable, and Lady Lyndon's condition worsens. For a time, the estate is left in the care of Barry's mother, who makes several calculated staff cuts under the guise of attaining financial stability. Several of the estate's long-standing staff persuade Lord Bullingdon to return and challenge Barry to a duel. Despite the opportunity to easily win the duel against the petrified Lord Bullingdon, Barry refuses, believing that Lord Bullingdon will have received his satisfaction. He is wrong about this, though, and gets shot in the leg, requiring amputation. Barry is offered one final lifeline: an annual stipend from his wife's estate, as long as he never returns to Britain. He accepts, and the final scene of the film shows a recovering Lady Lyndon, pausing thoughtfully as she signs Barry's annuity check.

That description should give a sense of just how eventful Barry Lyndon is as a film. I haven't even mentioned the minor events - Barry's brief relationship while posing as a lieutenant; the scene with the highwaymen; the fact that Captain Quin survives the duel after all - because they're of limited importance to the main plot. What Kubrick has succeeded in is bringing the fullness of a picaresque novel to the screen and giving it the true ambience of a serial novel. One element that really adds to this is the perfect casting of even the smallest roles. All the minor characters who appear, from the highwayman's teenaged son to the soldier that Barry bests in a boxing match to Captain Potzdorf's governmental uncle, are all given performances of such precision and vividness that they feel like entire chapters of Barry's life, even though they spend mere seconds on screen. Kubrick also makes Barry Lyndon's literary sources explicit by dividing the film into halves, each with its own wordy subtitle that tells us what we're about to see. There's also a significant shift from William Makepeace Thackeray's original novel which is largely unavoidable: the novel is told in the first person while the film, out of necessity, takes a more objective third-person approach. Kubrick has kept an omniscient narrator at times, to clarify events that Barry is not present for or which lack an impartial observer to explain. However, the majority of the film comes to us seemingly unmediated, which I think might be partly responsible for the reputation that has become attached to the film: that it's cynical and cold.

On the charge of cynicism, it's hard to disagree. Redmond Barry undergoes a slightly odd shift of personality when he meets Lady Lyndon, suddenly becoming cruel and callous in a way that seems too quick, even for a film that compresses time in this way. He's started as a deeply romantic figure, but one of the first times we see him after his marriage, he's blowing pipe smoke into Lady Lyndon's face despite her protests. His drive has become naked greed, which seems a little out of proportion with his behaviour immediately prior to the wedding. When this change has been commented on, it's usually suggested that Barry's romanticism has been dashed by his wartime experiences. I think this is a perfectly fine explanation, but I just don't see it on the screen to quite the degree I would anticipate. The events following the death of Barry's son are also deeply cynical - Lady Lyndon's depression and Barry's turn to alcoholism are indicative of Barry's failures as a husband and of the futility of his aspirations for wealth. Lord Bullingdon fights for his family's honour, but is terrified as he does so, and death would in some ways be a kindness to Barry, who faces mounting debts. Even his exile does not rid the Lyndon estate of him, as they are perpetually bound to pay his annuity. All ends as well as it could be expected to, but that does not mean unencumbered happiness for any of the characters. But does this mean that the film is 'cold'? I don't think so at all. Kubrick paints the first two thirds of the film with streaks of broad comedy, the effects of which linger long afterwards. Barry's awkward courtship with his cousin, the ruse by which he and the Chevalier de Balibari (Patrick Magee) escape Prussia, and even the duels Barry fights on the Chevalier's behalf, were all met with loud laughter from the packed Embassy Theatre screening. Even in the duel against Lord Bullingdon, there are beats of humour to leaven the gloom that hangs over everything. The film may be judgmental of its protagonist, but it does so while looking at a world full of witty and absurd characters.

Another element that has contributed to the film's chilly reputation is its visual style. Kubrick was partly inspired by the paintings of William Hogarth, and in one of the film's most famous images, Barry is shown in an almost identical pose to Hogarth's Marriage A-la-mode 2 (a painting which could basically sum up the entire second half of the film). What this means, on a practical level, is a large number of carefully-constructed tableaux, expressive lighting techniques, and landscapes in which the power of the elements overwhelms the human figures. The cinematography was the work of the Academy Award-winning John Alcott, who also worked with Kubrick on 2001 and A Clockwork Orange, and it is in every respect remarkable: stately and dramatic when it needs to be, caring and intimate at other times, but never obtrusive when the performances need to carry all the weight of a scene. I'm not completely sure where this style's association with 'coldness' comes from, but I imagine it's probably been reinforced by Kubrick's reputation as a perfectionist, which I think usually robs a director's films of warmth, too, which is what I was thinking of way back in my opening paragraphs. A reputation like this is almost never factually accurate, and stories tend to get blown out of proportion. Kubrick and Alcott shot many of these scenes without electric lighting, and famously borrowed three large and expensive lenses left over from the Apollo missions which enabled them to shoot some indoor scenes by candlelight. However, this fact has been blown out of proportion, and it's now commonly said that the production used no electric lighting at all - a story that's completely implausible if you look at any of the exterior nighttime scenes. Even the artificial lighting, however, successfully mimics the natural lighting to such a degree that it feels like it was filmed on location in time as well as place.

Because Kubrick's previous films were heavily based in more popular genres, and because they all shared a more acidic and satirical edge, many audiences were unsure what to make of Barry Lyndon, and the film was a disappointment at the box office. Critics were equally dismissive - multiple critics, including Charles Champlin and Pauline Kael, referred to it being less of a film and more of a coffee-table book, with Kael adding that Kubrick had "drained the blood" out of the source material. Even Vincent Canby, in an otherwise positive review, described the film as "another fascinating challenge". I find these statements a little odd, given that Kubrick's other films were no less weighty or accessible than Barry Lyndon was, but I think this is always one of the problems of trying to anticipate what a director renowned for being surprising will do. Although making a slow and stately film is entirely appropriate to what Kubrick clearly wanted to say about Thackeray's novel, it seems like this was the wrong type of surprise to viewers who wanted another breaking of their expected boundaries. In any event, this critical disappointment had an apparent impact on Kubrick. It definitely factored into his decision to make a slightly more traditional genre piece next... The Shining (1980).

Despite this, Barry Lyndon underwent a reappraisal over time, and it is now recognised as one of the director's masterpieces. Although I'm usually loath to rank films, I think Barry Lyndon definitely falls in my top three for Kubrick's films, and it certainly seems like one of his most accessible films. It merges the farcical comedy and bleak satire that his films are known for, while also being endlessly appealing on a visual level. Far from being worried that it was going to be homework, I'm tempted to go and watch it again already - and that's not something I say about a lot of Kubrick's three-hour-long doorstops.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Clockwork Orange (1971) dir. Stanley Kubrick

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

art imitating art

‘A Clockwork Orange’ (1971) dir. Stanley Kubrick // ‘Prisoners Exercising’ (1890) by Vincent van Gogh

#art imitates art#art imitating art#films#cinema#movies#art#film#film screencaps#a clockwork orange#vincent van gogh#van gogh#film community#film frames#stanley kubrick

91 notes

·

View notes