#A Benefit Portfolio In Defense of the First Amendment

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

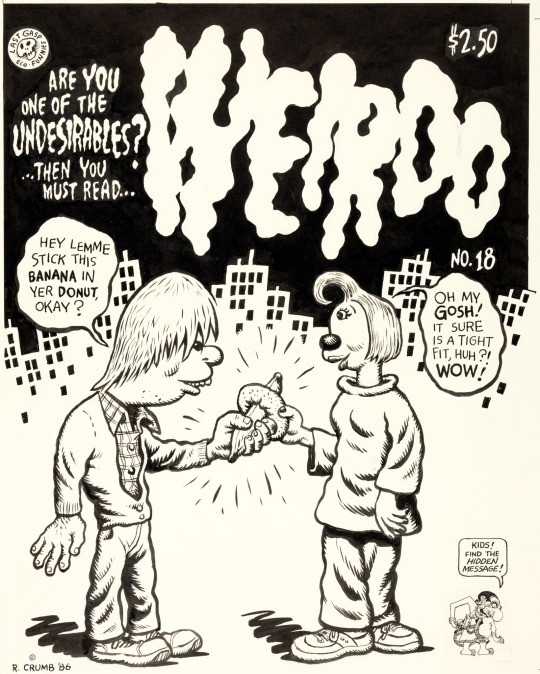

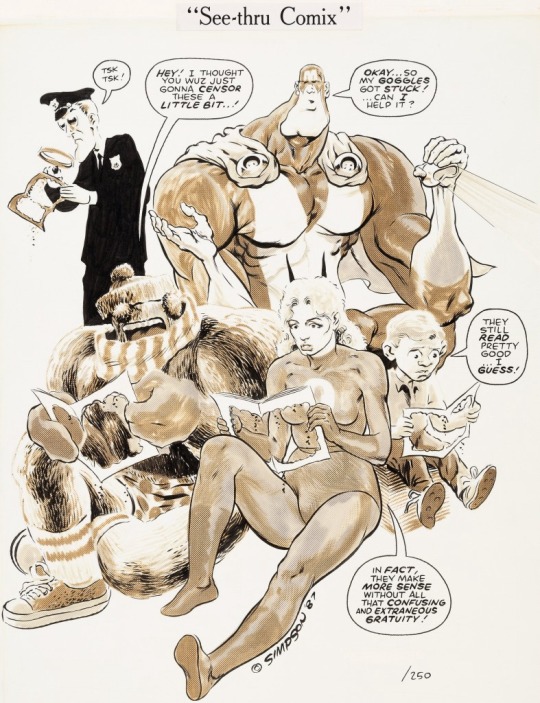

“A Benefit Portfolio In Defense of the First Amendment” Frank Miller, Sergio Aragones, Robert Crumb, Bob Burden, Reed Waller, Steve Bissette, Denis Kitchen, Don Simpson, Hilary Barta and Mitch O’Connell (1987) Source

#frank miller#Sergio Aragones#Robert Crumb#Bob Burden#Reed Waller#Denis Kitchen#Don Simpson#Hilary Barta#Mitch O’Connell#A Benefit Portfolio In Defense of the First Amendment

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Three originals (with closer looks) from 1987′s A Benefit Portfolio In Defense of the First Amendment (CBLDF) The originals are by Frank Miller (who donated an original unused cover from Ronin) and Robert Crumb, and Sergio Aragones.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Congress Moves For Emergency Containment of Ethics Outbreak

Below is my column in The Hill newspaper to the latest outbreak of ethics and the politically distancing being used by members to control the outbreak over insider trading. Notably, Minority Leader Chuck Schumer was adamant on barring business owned by President Donald Trump and Vice President Mike Pence from benefiting from the stimulus package. Notably absent however was a similar ban for members who have considerable stock or ownership interests in such companies.

Here is the column:

Members of Congress are moving with speed and determination to meet an existential crisis on a bipartisan basis. This is not about the coronavirus. The public has learned, once again, that lawmakers may be profiteering in the stock market. Members from both parties have worked for decades to prevent the closing of this obvious avenue of corruption. I know because I have been advocating for two decades that members of Congress should agree to the mandatory use of blind trusts for any stock ownership.

But members of Congress know voters will soon move on, distracted by the outbreak of a deadly disease or redirecting their political rage against the opposing party. The past incubation period for ethics outbreaks is only a couple of weeks and, with some political distancing, the curve is already flattening out. Lawmakers can rest easy because normalcy is simply one news cycle away and, until then, they are tax sheltering in place.

Several members of Congress have been denounced for dumping stocks before the government took critical measures to deal with the pandemic. Senators Richard Burr, Kelly Loeffler, James Inhofe, and Dianne Feinstein together are responsible for as much as $11 million in recent stock sales. It turns out that many lawmakers become market investment geniuses after they enter Congress. A University of Memphis study found that 75 percent of randomly selected members had made “stock transactions that directly coincided with legislative activity.” A Georgia State University study noted that, from 1993 to 1998, senators beat the stock market by 12 points with their portfolios and outperformed “corporate insiders” by 8 points.

Over the years, I have written about the obvious profiteering by members through insider information, stock manipulation, and sweetheart deals. It is not just a problem for the lawmakers. In 2016, the spouse of an aide to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi bought stock in two pharmaceutical firms, just before Congress passed a bill benefiting the companies. In 2017, the Senate demanded that the Justice Department open an investigation into the drugmaker Mylan. Nine days later there was a $465 million settlement with the company. Meanwhile, during that brief period, an aide to Senate Minority Whip Richard Durbin sold tens of thousands of dollars of Mylan stock. An investigation by Politico revealed numerous examples of such suspicious trades by House and Senate staffers of both parties.

Whenever a member of Congress is caught in such a scandal, Washington immediately turns to its timely and proven emergency plan and protocol. First, all lawmakers will express shock and dismay. Second, the affected members call for ethics investigations of themselves. Third, Washington waits for the next shiny object to dangle before voters. Why not? We fall for the same $5 genuine gold watch scam over and over again. The two political parties have us so wired into hating the other side that we still refuse to accept that both parties are equally craven and corrupt.

Right on cue, Washington has moved gingerly through phases one and two of its emergency contingency plan. Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer and members like Burr have called for ethics investigations. This, after all, is what the ethics rules of Congress are really designed for. They give cover to the alleged corrupt practices of members. What happened here is perfectly legal and, even more troubling, ethical under the rules of Congress. There is no requirement of a blind trust by members.

Under a blind trust, the trustees and beneficiaries generally communicate only to discuss asset distributions, to discuss general investment goals or to disclose summary trust information required for tax purposes. A blind trust is a mandatory requirement which lawmakers in neither party want. Accordingly, when scandals arise, members pass legislation named for public consumption, like the laughable Stop Trading On Congressional Knowledge Act which, notably, does not stop members from trading on congressional knowledge. The law, also known as the Stock Act, applies the same insider trading rules to members and staff that are applied to company executives. While fines are possible, they are unlikely.

Insider trading cases are hard for prosecutors to make against members of Congress because the law was designed to punish corporate officials who trade stocks by using proprietary information. Members of Congress do not deal with proprietary information held by company executives and, even with the broader definitions applied by the courts, it would be very difficult to use the legal language to fit legislative profiteering.

Moreover, legislative information usually holds some public controversy component that can be pointed to as the reason for a trade. Indeed, Burr has claimed that his decision was based on public information, a defense that would be challenging to defeat given the level of media attention and the varying reports that were being aired. While a shareholder would face alleged securities fraud in a civil action, Burr can legitimately claim that his action to sell simply showed better instincts than information.

The Stock Act has worked as members intended, however, as the public eventually moves on. One year after its passage, Congress then quietly amended the law to reduce disclosure requirements. The leadership on Capitol Hill passed the bill in “30 seconds” while most members were out of town to further reduce accountability. President Obama held a massive ceremony to sign the original bill, but his signing of the amendments one year later resulted in just a single sentence acknowledgement.

This is just one of the many federal loopholes that have allowed members of Congress to grow rich in public service. This includes the ability of the children and spouses of our elected officials to receive windfall contracts and undeserved positions from companies to buy influence, while elected officials can insist there is nothing illegal about such deals. This is how the rules are written. They facilitate, not frustrate, special dealing.

As so many of our leaders in Congress have declared, this crisis will pass. The ethics investigations will drag on, and public attention will shift back to political rage. Voters will soon be denouncing the opposing party with the same reliable and willful blindness to the transgressions in their own party. For now, both Republicans and Democrats are remaining steadfast and assuring their respective voters to keep calm and carry on.

Jonathan Turley is the Shapiro Professor of Public Interest Law at George Washington University. You can follow him on Twitter @JonathanTurley.

Congress Moves For Emergency Containment of Ethics Outbreak published first on https://immigrationlawyerto.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Petitions of the week

This week we highlight petitions pending before the Supreme Court that address, among other things, whether police violate the Fourth Amendment when they conduct a suspicionless search of a probationer’s home, whether a defendant advancing a claim under Brady v. Maryland must demonstrate that he or she could not have uncovered the suppressed evidence through the exercise of due diligence, and whether there is a “good faith defense” to 42 U.S.C. § 1983 that shields a defendant from damages liability for depriving citizens of their constitutional rights if the defendant acted under color of a law before it was held unconstitutional.

The petitions of the week are below the jump:

Rose v. Select Portfolio Servicing Inc. 19-1035 Issue: Whether 11 U.S.C. § 362(c)(3)(A) terminates the automatic bankruptcy stay as to property of the bankruptcy estate.

PennEast Pipeline Co. v. New Jersey 19-1039 Issue: Whether the Natural Gas Act delegates to Federal Energy Regulatory Commission certificate-holders the authority to exercise the federal government’s eminent-domain power to condemn land in which a state claims an interest.

Pike v. Gross 19-1054 Issues: (1) Whether a defendant who asserts that trial counsel failed to present key evidence is precluded from showing prejudice under Strickland v. Washington, unless the evidence omitted at trial differs substantially in subject matter from the evidence actually presented; and (2) whether the Eighth and 14th Amendments prohibit condemning to death a defendant who was 18 years old at the time of the offense.

Hamm v. Tennessee 19-1059 Issue: Whether police violate the Fourth Amendment when they conduct a suspicionless search of a probationer’s home.

CJ CheilJedang Corp. v. International Trade Commission 19-1062 Issue: Whether, to avoid prosecution-history estoppel under Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co., “the rationale underlying the amendment” must be the rationale the patentee provided to the public at the time of the amendment.

Comcast Corp. v. Tillage 19-1066 Issues: Whether the Supreme Court of California’s rule from McGill v. Citibank, N.A. – that provisions in predispute arbitration agreements waiving the parties’ right to seek “public injunctive relief” in any forum are contrary to California public policy and unenforceable – falls outside the Federal Arbitration Act’s saving clause because it is not a ground that “exist[s] at law or in equity” for the “revocation” of any contract; and (2) whether, even if the McGill rule falls within the FAA’s saving clause, it is otherwise preempted by the FAA because it interferes with fundamental attributes of arbitration by negating the parties’ agreement to resolve their dispute bilaterally.

Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. v. Painters and Allied Trades District Council 82 Health Care Fund 19-1069 Issues: (1) Whether the chain of causation between a manufacturer’s allegedly false or misleading statements or omissions and end payments for prescription drugs is too attenuated to satisfy the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act’s proximate cause requirement, given that every prescription-drug payment depends on numerous intervening factors, including a doctor’s independent decision to prescribe; (2) whether everyone who pays for a product with an alleged latent risk or defect necessarily suffers injury sufficient to confer Article III standing, even when the product is fully consumed, provides the bargained-for benefits and causes no ill effects.

AT&T Mobility LLC v. McArdle 19-1078 Issue: Whether California’s public-policy rule conditioning the enforceability of arbitration agreements on acquiescence to public-injunction proceedings is preempted by the Federal Arbitration Act.

Dailey v. Florida 19-1094 Issues: (1) Whether a defendant advancing a claim under Brady v. Maryland must demonstrate that he or she could not have uncovered the suppressed evidence through the exercise of due diligence; (2) whether the materiality of a Brady claim must be determined by considering the probative force of the withheld evidence cumulatively and in the context of the government’s entire case; and (3) whether the Florida Supreme Court’s error in treating petitioner’s claim under Giglio v. United States as though it alleged knowing use of perjury, when it actually alleged withholding exculpatory evidence, warrants reversal.

Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, Council 31 19-1104 Issue: Whether there is a “good faith defense” to 42 U.S.C. § 1983 that shields a defendant from damages liability for depriving citizens of their constitutional rights if the defendant acted under color of a law before it was held unconstitutional.

The post Petitions of the week appeared first on SCOTUSblog.

from Law https://www.scotusblog.com/2020/04/petitions-of-the-week-89/ via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes

Text

D&O Insurance: No Coverage for Alleged Misconduct Not Undertaken in an Insured Capacity

One of the basic requirements in order for coverage to be triggered under a directors’ and officers’ liability insurance policy is that the misconduct alleged must have been undertaken by insured individuals in an “insured capacity” – that is, in their capacities as directors or officers of the insured entity. In a recent insurance coverage ruling, the Delaware Superior Court held that because the allegations against the insured individuals “arose out of” their involvement with entities other than the insured entity, there was no coverage for the individuals under their bankrupt company’s D&O insurance policy. The ruling underscores the importance of capacity issues in determining D&O insurance coverage and highlights the ways in which allegations of misconduct undertaken in multiple capacities can lead to complicated coverage questions. The Delaware Superior Court’s November 30, 2018 decision can be found here.

Background

Keith Goggins and Michael Goodwin became directors of U.S. Coal in October 2009. During the time of their involvement with U.S. Coal, Goggins and Goodwin attempted to “reinvigorate” U.S. Coal through debt purchase and other capital restructuring. Goggins and Goodwin undertook these restructuring actions through two investment vehicles they formed, East Coast Miner LLC (“ECM”) and East Coast Mine II LLC (“ECM II”). Goggin was an investor and manager of the two investment entities, Goodwin was just an investor in the two investment entities.

In 2014, U.S. Coal’s creditors filed a petition for a Chapter 7 bankruptcy. A trustee was appointed. In 2015, U.S. Coal’s unsecured creditors committee filed a lawsuit against Goggin, Goodwin, ECM, and ECM II, alleging that Googin and Goodwin breached their fiduciary duties and committed other actions in favor of their own personal interest.

In an amended complaint, the Trustee substituted for the creditors as the named plaintiff. The amended complaint alleged that Googin and Goodwin “schemed to form and use the ECM entities to control U.S. Coal and defraud its creditors” by entering into various agreements that provided the entities with a higher return on investment and a preferred recovery in the event of U.S. Coal’s liquidation. The Trustee’s suit alleged twenty-one counts against Goggin, Goodwin and the ECM Entities. The court later said in the insurance coverage action that the counts brought against Googin and Goodwin were “largely based on their self-interested dealing that benefited ECM entities and themselves and undermined the interest of U.S. Coal and its debtors and creditors.”

Goggin and Goodwin submitted the claim to U.S. Coal’s D&O insurer, which defended the claim under a reservation of right. The insurer took the position that the claims against the two individuals were not covered under policy Exclusion 4(g), the “capacity” exclusion. The various parties sought to mediate the underlying claim. When the parties were unable to resolve the claim through mediation, Goggin and Goodwin filed an action in Delaware Superior Court seeking a judicial declaration that Exclusion 4(g) does not apply to the claims against them and that the insurer is obligated to pay all of their defense and indemnity expenses. Goggin and Goodwin filed a motion in the coverage lawsuit for judgment on the pleadings.

Exclusion 4(g) provides that:

The Insurer shall not be liable to make any payment for Loss in connection with any Claim made against an Insured:

(g) alleging, arising out of, based upon, or attributable to any actual or alleged act or omission of an Individual Insured serving in any capacity, other than as an Executive or Employee of a Company….

The November 30, 2018 Decision

In a November 30, 2018 Memorandum Opinion and Order, Delaware Superior Court Judge Paul R. Wallace, applying Delaware law, denied Goggin and Goodwin’s motion for judgment on the pleading, ruling that exclusionary clause applied to preclude coverage.

In reaching his decision, Judge Wallace said the “capacity” exclusion’s language “is clear and unambiguous.” He specifically noted the exclusion’s use of the “arising out of “ language, a term he noted that Delaware’s court have construed “broadly.” He also noted that court’s interpreting “arising out of” language have applied a “but-for” test to construe the meaning of insurance policy exclusions. Under this analysis, the question is “where the underlying claim would have failed ‘but for’ the excluded conduct.”

Applying the “but for” test in this case, Judge Wallace found that the alleged conduct “falls under the exclusionary clause.” He said that the Trustee Claims “would not have been established ‘but-for’ Goggin and Goodwin’s alleged ECM-related misconduct.” He added that “but for” the individuals’ roles as members and managers of the ECM entities, the claims in the amended complaint would have failed.

Judge Wallace added the observation that the Trustee’s claims are “most reasonably viewed as having arisen from Goggin and Goodwin’s misconduct as members/managers of the ECM Entities (although certainly related too to their co-existence as U.S. Coal’s directors).”

Accordingly, Judge Wallace said, “the exclusionary clause applies and eliminates [the insurer’s] coverage obligation under the D&O Policy.” Because the exclusion applies, the individuals “would not be due coverage for the ECM-related activity claims under the D&O policy.”

Discussion

Judge Wallace’s ruling in this case is very fact-specific. However, the coverage dispute and the circumstances alleged in the underlying claim do highlight the importance of capacity issues for D&O insurance coverage determination.

An unusual feature of the policy language involved here is that the policy addressed the insured capacity issue in an exclusion. This is a relatively unusual way for a policy to address the issue of insured capacity. More typically, the insured capacity issue is addressed in the D&O insurance policy’s definition of the term “Wrongful Act.” The significance of the definition is that D&O insurance provides coverage for Claims against Insured Persons alleging a Wrongful Act. The typical definition will specify that the term Wrongful Act refers to any breach of duty, neglect, omission or act by an officer or director “in their respective capacities as such” or any matter claimed against an officer or director “by reason of his or her status as an Executive or Employee of a Company.”

Disputes involving capacity issues are not uncommon, for the simple reason that it is not unusual for a director or officer to be acting in multiple capacities. Company executives may act in a personal capacity as well as a corporate capacity. A representative of a private equity firm who sits on a portfolio company’s board may be acting both in his capacity as representative of the PE firm and of the portfolio company.

Because of the frequency with which corporate officials may act in dual or multiple capacities, it is important that the D&O insurance policy does not require in order for coverage to apply that the insured person was acting “solely” in an insured capacity.

In this case, the court did not find that coverage was precluded because the two individuals were acting in a dual capacity; rather, the court’s ruling turned on its conclusion that the misconduct alleged “arose out of” the two individuals’ uninsured capacity as manager members of the ECM Entities, and not out of their insured capacity as directors and officers of U.S. Coal. The “arising out of” language appeared in the policy exclusion at issue, which, as I noted is an unusual D&O insurance policy feature.

The interpretation and application of a different policy that did not have the “insured capacity” exclusion – and in particular that did not have the “arising out of” exclusionary language – might possibly have produced a different outcome. In that regard, I think it is important to note that Judge Wallace expressly acknowledged (albeit parenthetically) that while the Trustee’s claims “arose out of” their capacities as members/managers of the ECM Entities, the claims were “certainly related too to their co-existence as U.S. Coal’s directors.”

The two individuals wouldn’t have been sued in the Trustee’s complaint if they weren’t directors of U.S. Coal. Indeed, the gravamen of the Trustee’s complaint is that, due to conflicts of interest, the two individuals’ breached their duties as directors of U.S. Coal. The fact that they allegedly were acting in a dual capacity, in my view, ought not be sufficient to preclude coverage entirely; at most, the fact that the claims allege misconduct allegedly undertaken in a dual capacity ought to result in an allocation between covered and non-covered claims. A policy without the exclusionary language – language which, as noted above, is unusual – might have provided at least allocated coverage to the extent the individuals were sued (as Judge Wallace acknowledged) in their capacities as U.S. Coal directors.

All of that said, the important thing to note about this case is the critical significance of capacity questions and the role of capacity as a prerequisite to coverage under a D&O insurance policy.

In an earlier post (here), I discussed a June 2015 opinion of the Eleventh Circuit in which the appellate court affirmed a district court ruling interpreting the same exclusionary provision as was at issue here, and applying the exclusion to preclude coverage for an underlying claim in which individual insureds were alleged to be acting in a dual capacity.

A December 4, 2018 memo from the White & Williams firm discussing the Delaware Superior Court’s decision can be found here.

The post D&O Insurance: No Coverage for Alleged Misconduct Not Undertaken in an Insured Capacity appeared first on The D&O Diary.

D&O Insurance: No Coverage for Alleged Misconduct Not Undertaken in an Insured Capacity published first on http://simonconsultancypage.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

D&O Insurance: No Coverage for Alleged Misconduct Not Undertaken in an Insured Capacity

One of the basic requirements in order for coverage to be triggered under a directors’ and officers’ liability insurance policy is that the misconduct alleged must have been undertaken by insured individuals in an “insured capacity” – that is, in their capacities as directors or officers of the insured entity. In a recent insurance coverage ruling, the Delaware Superior Court held that because the allegations against the insured individuals “arose out of” their involvement with entities other than the insured entity, there was no coverage for the individuals under their bankrupt company’s D&O insurance policy. The ruling underscores the importance of capacity issues in determining D&O insurance coverage and highlights the ways in which allegations of misconduct undertaken in multiple capacities can lead to complicated coverage questions. The Delaware Superior Court’s November 30, 2018 decision can be found here.

Background

Keith Goggins and Michael Goodwin became directors of U.S. Coal in October 2009. During the time of their involvement with U.S. Coal, Goggins and Goodwin attempted to “reinvigorate” U.S. Coal through debt purchase and other capital restructuring. Goggins and Goodwin undertook these restructuring actions through two investment vehicles they formed, East Coast Miner LLC (“ECM”) and East Coast Mine II LLC (“ECM II”). Goggin was an investor and manager of the two investment entities, Goodwin was just an investor in the two investment entities.

In 2014, U.S. Coal’s creditors filed a petition for a Chapter 7 bankruptcy. A trustee was appointed. In 2015, U.S. Coal’s unsecured creditors committee filed a lawsuit against Goggin, Goodwin, ECM, and ECM II, alleging that Googin and Goodwin breached their fiduciary duties and committed other actions in favor of their own personal interest.

In an amended complaint, the Trustee substituted for the creditors as the named plaintiff. The amended complaint alleged that Googin and Goodwin “schemed to form and use the ECM entities to control U.S. Coal and defraud its creditors” by entering into various agreements that provided the entities with a higher return on investment and a preferred recovery in the event of U.S. Coal’s liquidation. The Trustee’s suit alleged twenty-one counts against Goggin, Goodwin and the ECM Entities. The court later said in the insurance coverage action that the counts brought against Googin and Goodwin were “largely based on their self-interested dealing that benefited ECM entities and themselves and undermined the interest of U.S. Coal and its debtors and creditors.”

Goggin and Goodwin submitted the claim to U.S. Coal’s D&O insurer, which defended the claim under a reservation of right. The insurer took the position that the claims against the two individuals were not covered under policy Exclusion 4(g), the “capacity” exclusion. The various parties sought to mediate the underlying claim. When the parties were unable to resolve the claim through mediation, Goggin and Goodwin filed an action in Delaware Superior Court seeking a judicial declaration that Exclusion 4(g) does not apply to the claims against them and that the insurer is obligated to pay all of their defense and indemnity expenses. Goggin and Goodwin filed a motion in the coverage lawsuit for judgment on the pleadings.

Exclusion 4(g) provides that:

The Insurer shall not be liable to make any payment for Loss in connection with any Claim made against an Insured:

(g) alleging, arising out of, based upon, or attributable to any actual or alleged act or omission of an Individual Insured serving in any capacity, other than as an Executive or Employee of a Company….

The November 30, 2018 Decision

In a November 30, 2018 Memorandum Opinion and Order, Delaware Superior Court Judge Paul R. Wallace, applying Delaware law, denied Goggin and Goodwin’s motion for judgment on the pleading, ruling that exclusionary clause applied to preclude coverage.

In reaching his decision, Judge Wallace said the “capacity” exclusion’s language “is clear and unambiguous.” He specifically noted the exclusion’s use of the “arising out of “ language, a term he noted that Delaware’s court have construed “broadly.” He also noted that court’s interpreting “arising out of” language have applied a “but-for” test to construe the meaning of insurance policy exclusions. Under this analysis, the question is “where the underlying claim would have failed ‘but for’ the excluded conduct.”

Applying the “but for” test in this case, Judge Wallace found that the alleged conduct “falls under the exclusionary clause.” He said that the Trustee Claims “would not have been established ‘but-for’ Goggin and Goodwin’s alleged ECM-related misconduct.” He added that “but for” the individuals’ roles as members and managers of the ECM entities, the claims in the amended complaint would have failed.

Judge Wallace added the observation that the Trustee’s claims are “most reasonably viewed as having arisen from Goggin and Goodwin’s misconduct as members/managers of the ECM Entities (although certainly related too to their co-existence as U.S. Coal’s directors).”

Accordingly, Judge Wallace said, “the exclusionary clause applies and eliminates [the insurer’s] coverage obligation under the D&O Policy.” Because the exclusion applies, the individuals “would not be due coverage for the ECM-related activity claims under the D&O policy.”

Discussion

Judge Wallace’s ruling in this case is very fact-specific. However, the coverage dispute and the circumstances alleged in the underlying claim do highlight the importance of capacity issues for D&O insurance coverage determination.

An unusual feature of the policy language involved here is that the policy addressed the insured capacity issue in an exclusion. This is a relatively unusual way for a policy to address the issue of insured capacity. More typically, the insured capacity issue is addressed in the D&O insurance policy’s definition of the term “Wrongful Act.” The significance of the definition is that D&O insurance provides coverage for Claims against Insured Persons alleging a Wrongful Act. The typical definition will specify that the term Wrongful Act refers to any breach of duty, neglect, omission or act by an officer or director “in their respective capacities as such” or any matter claimed against an officer or director “by reason of his or her status as an Executive or Employee of a Company.”

Disputes involving capacity issues are not uncommon, for the simple reason that it is not unusual for a director or officer to be acting in multiple capacities. Company executives may act in a personal capacity as well as a corporate capacity. A representative of a private equity firm who sits on a portfolio company’s board may be acting both in his capacity as representative of the PE firm and of the portfolio company.

Because of the frequency with which corporate officials may act in dual or multiple capacities, it is important that the D&O insurance policy does not require in order for coverage to apply that the insured person was acting “solely” in an insured capacity.

In this case, the court did not find that coverage was precluded because the two individuals were acting in a dual capacity; rather, the court’s ruling turned on its conclusion that the misconduct alleged “arose out of” the two individuals’ uninsured capacity as manager members of the ECM Entities, and not out of their insured capacity as directors and officers of U.S. Coal. The “arising out of” language appeared in the policy exclusion at issue, which, as I noted is an unusual D&O insurance policy feature.

The interpretation and application of a different policy that did not have the “insured capacity” exclusion – and in particular that did not have the “arising out of” exclusionary language – might possibly have produced a different outcome. In that regard, I think it is important to note that Judge Wallace expressly acknowledged (albeit parenthetically) that while the Trustee’s claims “arose out of” their capacities as members/managers of the ECM Entities, the claims were “certainly related too to their co-existence as U.S. Coal’s directors.”

The two individuals wouldn’t have been sued in the Trustee’s complaint if they weren’t directors of U.S. Coal. Indeed, the gravamen of the Trustee’s complaint is that, due to conflicts of interest, the two individuals’ breached their duties as directors of U.S. Coal. The fact that they allegedly were acting in a dual capacity, in my view, ought not be sufficient to preclude coverage entirely; at most, the fact that the claims allege misconduct allegedly undertaken in a dual capacity ought to result in an allocation between covered and non-covered claims. A policy without the exclusionary language – language which, as noted above, is unusual – might have provided at least allocated coverage to the extent the individuals were sued (as Judge Wallace acknowledged) in their capacities as U.S. Coal directors.

All of that said, the important thing to note about this case is the critical significance of capacity questions and the role of capacity as a prerequisite to coverage under a D&O insurance policy.

In an earlier post (here), I discussed a June 2015 opinion of the Eleventh Circuit in which the appellate court affirmed a district court ruling interpreting the same exclusionary provision as was at issue here, and applying the exclusion to preclude coverage for an underlying claim in which individual insureds were alleged to be acting in a dual capacity.

A December 4, 2018 memo from the White & Williams firm discussing the Delaware Superior Court’s decision can be found here.

The post D&O Insurance: No Coverage for Alleged Misconduct Not Undertaken in an Insured Capacity appeared first on The D&O Diary.

D&O Insurance: No Coverage for Alleged Misconduct Not Undertaken in an Insured Capacity syndicated from https://ronenkurzfeldweb.wordpress.com/

0 notes

Text

Congress Examines SBA Poultry Loan Practices in Contentious Hearing

Contract poultry producer Karen Crutchfield, Photo credit: Marcello Cappellazzi.

The central question at last week’s House Small Business Committee hearing was this: Who does the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) 7(a) program really help, and does that comport with the program’s stated intent? SBA’s 7(a) program has come under fire recently, following the release of an SBA Inspector General’s (IG) report that found SBA had wrongly made at least $1.7 billion in loans for contract poultry facilities.

In response to the report, as well as cries from the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC) and many other food and farm organizations, Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) offered, and the Committee passed, an amendment to an SBA oversight bill (S. 2283) requiring SBA to report on how it plans to address the issues highlighted in the IG’s report. Subsequently, the House Small Business Committee also called for this congressional hearing, which gave SBA its first opportunity to respond to directly to Congress. The Committee heard from SBA Inspector General Hannibal Ware and the Associate Administrator for Capitol Access at SBA, William Manger (who is responsible for the 7(a) program).

The following post includes a recap and analysis from the House Small Business Committee, as well as forecasted next steps. To learn more about the findings of the IG’s report, see NSAC’s previous post: New Report Exposes Over $1 Billion in Bad Loan-making at SBA.

Contentious from the Beginning

The battle lines were drawn early on in the hearing as Associate Administrator Manger immediately went on the defensive when asked whether the contract poultry loans were made in compliance with SBA’s regulations. IG Ware, however, stuck behind the findings of his report and reasserted to the Committee that the loans were contrary to SBA regulations. Ware also stood behind his assessment that the loans were made to the near exclusive benefit of large, multinational corporations – not the “small businesses” SBA is tasked to support.

Committee Chairman Steve Chabot (R-OH) and Ranking Member Nydia Velázquez (D-NY) put tough questions to Manger, pointedly asking if SBA should even be in the poultry loan business. The default rate for contract poultry loans is incredibly low, just 0.37 percent, which makes it unclear why SBA would need to step in as an additional source for poultry loans. Manger’s answer, which seemed not to satisfy the Chair and Ranking Member, was that since many loans involve land acquisitions and borrowers with sub-par credit, the borrowers cannot always qualify for a private loan and therefore need help from SBA. It is interesting to note, however, that later in the hearing Manger also stated that SBA would no longer allow loans that include ancillary property.

Response to Reform and a Revelation

Responding to the Committee’s questions about what reforms SBA had made or would be making following the IG report, Manger highlighted the following SBA actions:

Limiting contract poultry production loans to 15 years. This is apparently based on SBA’s estimation of the “useful life” of a poultry facility; however, many farmers would disagree with their estimates. Contract farmers indicate that integrators begin to require facility upgrades as early as years 7-8 into the contract, which then requires the farmer to seek further loan support and take on additional debt.

Implementing a limitation on loans to land used for the actual poultry operation. Though Manger did not state this explicitly, it appears that some poultry loans included other land, possibly associated farmland or homesteads located on the same property as the facility.

Requiring that start-up operations, and those having a change in ownership, have at least 10 percent equity.

While these actions seem designed to show that SBA is being responsive to the IG’s report, there is little in the announced changes that would provide any additional protection for the farmer borrowers struggling under highly restrictive and short-lived contracts with poultry integrators.

During the conversations about SBA’s recent reforms, Associate Administrator Manger revealed to the Committee that SBA had loosened the affiliate rules in 2016 to eliminate the economic dependence test. This test, which was in place during the period reviewed by the IG’s report, classified any business that was economically dependent on another business (even if it had separate ownership) to be an “affiliate” of that latter business. The economic dependence test was an important safeguard against SBA making loans to large businesses.

Ranking member Velasquez hammered Manger on this point, demanding further clarification and identification of who made the decision to loosen the rules. Not only does allowing loans to affiliates open the door to SBA serving large businesses; it also enables SBA to prop up and exacerbate a flawed contracting system in which poultry integrators exploit chicken farmers, who often become dependent on unsustainable, government-backed loans.

Credit Tests and Loan Contract Practices

Among the many other important issues that the Committee dug into during this hearing were inquiries into SBA’s credit testing practices and loan term setting for poultry-specific lending.

SBA’s lending practices generally require a credit test, which must show that the borrower is not able to obtain credit elsewhere in order to secure an SBA loan. This test is in place in order to ensure that SBA is not crowding out the private market or disrupting commercial markets; however, the Committee questioned whether or not the test was being applied correctly for contract poultry facility loans.

Although Manger defended SBA’s practices regarding credit testing for poultry facility loans, he also admitted that SBA relies on the private lenders that write the SBA-backed loans to make the final determination and to include certification in the loan file.

Unfortunately, Ware could not provide any additional insights into whether the poultry facilities receiving SBA loans are meeting the “no credit elsewhere” test; however, he did reveal that a separate investigation of 7(a) programs’ compliance with the test is underway.

Chairman Chabot also asked Manger to explain to the Committee why SBA was making poultry loans of 15-20+ years when the contracts typically only last around three years. Manger attempted to evade the question, simply noting that several of the loans reviewed by the IG were for such long lengths because they included additional land not directly related to the poultry facility. In the end, Manger failed to address the disconnect or to explain why SBA would back long-term loans for short-term contracts when there is no assurance of cash flow.

What Comes Next?

The House Small Business Committee held this oversight hearing as a result of the IG report, but they are not alone in taking action. Senator Booker offered an amendment to S. 2283, the Small Business 7(a) Lending Oversight Reform Act of 2018, that would require SBA to inform Congress on what it does in response to the IG report. This hearing provided an initial, albeit partial, response.

Following the House Small Business Committee hearing, NSAC will be looking to see if S. 2283 and its House companion H.R. 4743 are passed into law. While not specifically targeted at resolving the issues with the SBA poultry lending, the bipartisan House and Senate bills are both aimed at addressing similar underlying issues across the 7(a) loan portfolio.

NSAC will also be watching for additional reports and revelations that may come from the Office of the IG following the completion of related investigations. We applaud IG Ware and his office for this important work and for helping to ensure that SBA has the best interests of small business borrowers as its top priority – not the interests of large, multinational corporations.

The post Congress Examines SBA Poultry Loan Practices in Contentious Hearing appeared first on National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition.

from National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition https://ift.tt/2JurclO

from Grow your own https://ift.tt/2vQ7KOa

0 notes

Text

Qualcomm: Thank You, CFIUS

New Post has been published on http://indolargeprints.com/qualcomm-thank-you-cfius/

Qualcomm: Thank You, CFIUS

Rethink Technology business briefs for March 6, 2018.

The CFIUS letter makes clear that security concerns are not “theater”

Broadcom CEO Hock Tan, source: Broadcom.

Broadcom (AVGO) has characterized the delay in the Qualcomm (QCOM) shareholder meeting as

…a blatant, desperate act by Qualcomm to entrench its incumbent board of directors and prevent its own stockholders from voting for Broadcom’s independent director nominees.

Broadcom also has criticized the secrecy surrounding Qualcomm’s request for a Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. (CFIUS) review:

Broadcom reiterates that Qualcomm failed to disclose to its own stockholders and to Broadcom that it secretly filed a voluntary unilateral request for CFIUS review on January 29, 2018. Broadcom’s only correspondence with CFIUS was in response to CFIUS inquiries about Broadcom’s nomination of directors to the Qualcomm board of directors, and such requests did not reveal that Qualcomm filed to initiate the CFIUS review on January 29, 2018.

Although Broadcom clearly wants to portray Qualcomm’s management as going behind the backs of its shareholders, I doubt that the secrecy can be considered a failing.

The Wall Street Journal has published a letter by the Treasury Department’s Deputy Assistant Secretary Aimen N. Mir explaining the investigation that was sent to both parties on March 5. Mir divulges some information about Qualcomm that, while not classified, is probably not generally known:

U.S. national security also benefits from Qualcomm’s capabilities as a supplier of products. For example, Department of Defense national security programs rely on continued access to Qualcomm products. Qualcomm holds a facility security clearance and performs on a range of contracts for the United States government customers with national security responsibilities. Qualcomm currently holds active sole source classified prime contracts with DOD.

In my past life in the defense industry, I probably worked for many of those same government customers, and I can attest to their sensitivity regarding security matters. They would expect Qualcomm to proceed with the utmost discretion.

It was entirely appropriate for Qualcomm to alert CFIUS to the national security implications of the Broadcom takeover. The only thing that’s mildly surprising is that Qualcomm even needed to do this. But it’s probably symptomatic of the “compartmentalization” of so many of these types of classified programs.

Personnel in these programs often can’t even acknowledge their existence. Probably, Qualcomm did first alert its customers, who then “suggested” that Qualcomm inform CFIUS since the customers themselves would be precluded from doing so.

The letter’s unintended irony

The Mir letter also describes a broad range of concerns about the impact of weakening Qualcomm’s competitiveness, especially in the emergent technology of 5G:

Reduction in Qualcomm’s long-term technological competitiveness and influence in standard setting would significantly impact U.S. national security. This is in large part because a weakening of Qualcomm’s position would leave an opening for China to expand its influence on the 5G standard-setting process.

Also, a concern is what Broadcom will change post acquisition:

CFIUS, during the investigation period, will continue to assess the likelihood that acquisition of Qualcomm by Broadcom could result in a weakening of Qualcomm’s position in maintaining its long-term technological competitiveness. Specifically, Broadcom’s statements indicate that it is looking to take a “private equity” style direction if it acquires Qualcomm, which means reducing long-term investment, such as R&D, and focusing on short-term profitability.

Almost certainly, this would be the case, especially considering the $106 billion in debt financing the Broadcom intends to use. The letter is refreshingly complimentary of Qualcomm, especially in light of the vilification of Qualcomm as an abusive monopolist at the hands of the Federal Trade Commission.

After applauding Qualcomm’s technological leadership and R&D investments, the letter takes a somewhat different view of Qualcomm’s licensing business than the FTC:

Qualcomm’s current business model is based upon licensing of patented Qualcomm technologies; Qualcomm believes that Broadcom will change that licensing methodology. Broadcom’s CEO Hock Tan recently criticized Qualcomm’s licensing structure, saying he would reset the business model, which he called “broken.” However, Mr. Tan did not elaborate on how he would change the existing model, which currently relies on the licensing business to fund the company’s large R&D expenditures. Changes to Qualcomm’s business model would likely negatively impact the core R&D expenditures of national security concern.

The letter rightly characterizes Qualcomm as a national technological resource, yet it is the very actions of the government in the form of the FTC suit that have contributed to the weakening of Qualcomm and its vulnerability to takeover.

Why I voted the White Card

The impending proxy fight involves voting between competing slates of directors. Shareholders have been mailed proxy ballots, a “white card” for Qualcomm incumbents and a “blue card” for the Broadcom candidates. I voted (online, because it’s easier than mailing in the ballot) for the Qualcomm incumbents.

I’ve often been critical of Qualcomm’s management for its cluelessness regarding its regulatory issues. I firmly believe that reform of Qualcomm’s business practices is necessary. However, I’ve never believed that Qualcomm should or would be required to dismantle its fundamental licensing practices.

Apple (AAPL) has complained about being “taxed” on every iPhone its contract manufacturers make as if the $10 or $15 of added cost is an onerous financial burden. Apple claims, as the FTC has claimed, that Qualcomm has no right to charge royalties at the handset level.

Qualcomm has every right to do so. Qualcomm reached an agreement with the contract manufacturers to license not one or two patents but a large portfolio of patents that might or might not be applicable to a given handset (and not just Apple’s). For simplicity and convenience, the fees were to be paid on a handset basis.

It’s a perfectly enforceable and reasonable licensing contract, and Apple and the FTC will be proved wrong in challenging it. Licensing of patent bundles is a common practice that neither Apple nor the FTC is empowered to overturn. In every successful anti-competition action that has been taken so far anywhere in the world against Qualcomm, not once has Qualcomm been required to abandon the practice.

Convinced as I am that Qualcomm will ultimately prevail against Apple and the FTC, I was surprised to learn in the days before the planned (and now delayed) shareholder meeting that the proxy vote was going to be close. And some are now convinced that Qualcomm would have lost the vote.

Qualcomm’s institutional investors, which own 79% of outstanding shares, seem to have lost their nerve to stay the course. It’s hard to blame them. Given that Qualcomm’s growth opportunities are from certain, while anti-competition actions, such as the recent EU fine of $1.2 billion, seem very certain, the $82/share Broadcom offer must seem like a great way cash out with a net gain.

I continue to believe that the best interests of Qualcomm’s shareholders are served by Qualcomm moving forward with the NXP (NXPI) acquisition. On February 20, Qualcomm upped its bid by 16% for NXP to $127.50/share cash, while lowering the minimum tender threshold to 70% from 80%.

More importantly, Qualcomm reached an agreement to buy the shares of major institutional holders of NXP who together own 28% of the company. Among them was Elliott Advisors, who had vocally opposed the deal until now. Having mollified Elliott probably paves the way for broad-based acceptance of the tender offer and conclusion of the deal.

My investment case for Qualcomm has always been predicated on the NXP acquisition. In announcing the amended offer, Qualcomm pointed out that $1.50 of its non-GAAP EPS target for 2019 of $6.75-7.50 would come from NXP. NXP has been the one sure thing in the Qualcomm growth strategy.

With the acquisition of NXP, its 5G leadership, its brilliant ARM processor design, its innovation in mobile communications, Qualcomm deserves to remain an independent, and most importantly, American, enterprise.

The above Tech Briefs contain excerpts from a report published exclusively for Rethink Technology subscribers. Qualcomm is part of the Rethink Technology Portfolio and is rated a buy. Overall, the Portfolio provided a 39.2% total return in its first year.

Consider subscribing to the Rethink Technology service before March 12, when the price will increase 20%. Subscribing before March 12 permanently locks in the lowest price regardless of future price increases, which will probably happen on an annual basis.

Disclosure: I am/we are long QCOM, AAPL.

I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Related Posts:

No Related Posts

0 notes

Text

Treasury Dept. Says You Shouldn’t Have The Right To Sue Your Bank Or Credit Card Company

Forget the Sixth Amendment, which guarantees the “right to a speedy and public trial” in criminal matters. And who needs that ancient Seventh Amendment and its fancy “right of trial by jury.” The U.S. Treasury Department has concluded that American consumers can not be trusted to thoughtfully exercise these Constitutional rights — at least not when doing so might be an annoyance to the financial services sector.

This morning, the Treasury released a report [PDF] criticizing the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s recently finalized rule that limits the use of forced arbitration in consumer financial services.

What Is Forced Arbitration?

Those who read Consumerist frequently are probably familiar with arbitration, but for those who aren’t, here’s a crash course: Go look at the contract/user agreement/terms of service for just about any company you do business with: your bank, credit card company, wireless provider, cable/broadband service, software, e-commerce, electronics, online services… There’s a very good chance that buried deep in that contract is a clause that does two things, neither of which are to your advantage.

First, it blocks you from suing that company in court. Instead, you must go through private — often confidential — arbitration. Second, these clauses almost always include a condition barring you from joining your complaint together with other customers who were wronged in the same way, even through arbitration.

So Company X can illegally overcharge 10 million customers, but rather than face a single class-action lawsuit representing all 10 million victims, Company X says it’s more convenient to face 10 million individual arbitration hearings.

The Reality

Except they know that this will never happen. Very few Americans know about or understand the basics of arbitration, so the odds of even a small percentage of those 10 million customers hiring an attorney and arbitrating a dispute is going to be small. Thus, rather than facing a single class-action representing 10 million customers, Company X might face 10 or 15 arbitration claims. And even though each of those few customers might go into arbitration with exactly the same evidence, it’s entirely possible that they could each result in a different decision by the arbitrator. What’s more, it’s likely that no one will know as many arbitration hearings include a gag order preventing the customer from saying anything publicly.

If the individual harm done to each customer is small, Company X might also face zero arbitration cases. After all, who is going to hire a lawyer and go through the arbitration process for a $1 overcharge? As federal appeals court Judge Richard Posner noted in Carnegie v. Household Int’l, “only a lunatic or a fanatic sues for $30.”

Maybe Company X gives refunds — possibly even a few dollars extra as a “sorry about that” — to the handful of customers that notice and take the time to complain to customer service, but Company X has not been held accountable and made to answer for its apparent crime.

Say 100,000 Company X customers realize the overcharge, spend the half an hour on the phone with customer service escalating their complaint, and finally get a refund and another $10 in credit for their troubles (so $11 each). That means Company X has only had to pay out $1.1 million of the $10 million it illegally collected. It’s also avoided the stigma and cost of a criminal or civil defense and possibly avoided having to explain to state or federal prosecutors what happened.

This is why critics of forced arbitration have referred to these clauses as “get out of jail free cards” for big businesses.

The New Rule

The 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reforms not only established the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, but also directed the CFPB to study forced arbitration to determine if it was being abused and needed to be regulated to guarantee that financial institutions were not allowing themselves to sidestep the legal system.

After years of research, the CFPB finally finalized its arbitration rule in July 2017.

That rule does not outlaw forced arbitration. Rather, it prevents certain financial companies — only those that are directly regulated by the CFPB — from using forced arbitration to block class actions.

In the CFPB’s view, this means that banks, credit card companies, and other affected companies could still seek to have legal disputes resolved through arbitration, but they would not be able to minimize their liability for large-scale crimes and mismanagement.

The Treasury Disagrees

Yet, to the Trump administration — via the new Treasury Department report — making banks accountable for their bad behavior is unacceptable.

Claiming that the financial sector will face “extraordinary costs,” the Treasury Department says that restoring consumers’ rights to hold banks’ accountable is not worth the additional 600 class-action lawsuits that might be filed each year, resulting in $100 million a year in additional legal defense fees, and $340 million per year in settlements.

That sounds like a lot of money, but when you consider that the ten largest banks in the U.S. have nearly $12 trillion in assets, and that these additional hundreds of class-action lawsuits would be spread out across thousands of affected financial services companies, this is not a rule that banks can’t afford to comply with.

Or — and this is just a crazy suggestion — maybe the bad banks that would get sued could stop doing awful things like, opening millions of fake accounts in customers’ names to juke sales figures, and then telling those customers they can’t sue.

We’ve Heard This Song Before…

The Treasury steals another talking point from the banking lobby when it makes the argument that class actions shouldn’t be allowed because plaintiffs rarely get much money while class-action attorneys get rich (almost as rich as bankers!).

“[P]laintiffs who do claim funds from class action settlements receive, on average, $32.35 per person,” reads the Treasury report, which plays up the fact that plaintiffs’ lawyers will make an additional $66 million a year if there is no forced arbitration.

Again, that seems like a ridiculous amount of money, but the Treasury glosses over that this is the payout for all class-action attorneys across potentially hundreds of lawsuits.

Meanwhile, disgraced Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf, who admitted before Congress that he’d heard about employees opening up fake accounts at least three years before settling with the CFPB over such allegations (and who may have actually been warned about the problem nearly a decade earlier) initially walked away from his position in the midst of the scandal with a compensation package worth $130 million.

The bank’s board, facing heavy backlash from lawmakers and the public, eventually clawed back about half of that, but a man who allegedly turned his head while thousands of his employees were defrauding millions of customers still ended up with a golden parachute that was worth all of the additional compensation that all class-action plaintiffs attorneys might see.

As for the “small payout to plaintiffs” argument, it glosses over the fact — as described above — that some companies use arbitration clauses to avoid accountability for transgressions that are small on an individual basis but substantial when seen as a whole.

But again, maybe the way for the banks to make sure that plaintiffs’ attorneys don’t make all those extra millions is to not screw over their customers?

Willful Ignorance?

“The Treasury report willfully ignores the fact that class actions returned $2.2 billion to consumers between 2008 through 2012 — after deducting attorneys’ fees and court costs,” says Lisa Donner, executive director, Americans for Financial Reform. “That hardly seems like ‘no relief.’

Donner also points to a study from the Economic Policy Institute, which found that the average consumer who goes to arbitration ends up having to pay their bank or lender $7,725 in fees.

“It is clear that consumers derive benefits from class-action lawsuits and lose when forced into secret arbitration,” she says.

Just The Latest Attack On Your Rights

Bank-backed members of Congress are currently attempting to undo the rule using the Congressional Review Act, a previously little-known federal law that allows Congress to stop any new federal regulations within the first few months after they have been finalized. The House CRA resolution passed on a nearly party-line vote in July, almost immediately after the arbitration rule became official, but it has since stalled in the Senate where it reportedly does not have enough support from moderate Republicans to reach the 50 votes it needs. However, the CRA repeal window for the arbitration rule doesn’t close until early November, so it’s possible the Senate could pounce on it at the last minute.

With legislative repeal of the rule in doubt, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce — which is the nation’s biggest lobbying organization, even though some people mistakenly think it’s a governmental agency — recently sued the CFPB in federal court, seeking to halt the rule.

The Treasury Department report, which lists no author and does not appear to have been written at the request of any Congressional committee or even the White House, seems to be a de facto legal brief in support of the Chamber of Commerce lawsuit.

Or perhaps this is a personal crusade for Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, a former Goldman Sachs banker, who took over collapsed mortgage lender IndyMac in 2009 at the bottom of the Great Recession. As CEO of IndyMac, which changed its name to OneWest under Mnuchin’s leadership, the lender was heavily criticized for overly aggressive foreclosure actions. Between the time Mnuchin’s investor group acquired the IndyMac portfolio and when they sold it in 2015, the company was a defendant in more than 1,500 civil lawsuits filed in federal court.

by Chris Morran via Consumerist via Blogger http://ift.tt/2yDkZlz http://ift.tt/eA8V8J

0 notes

Photo

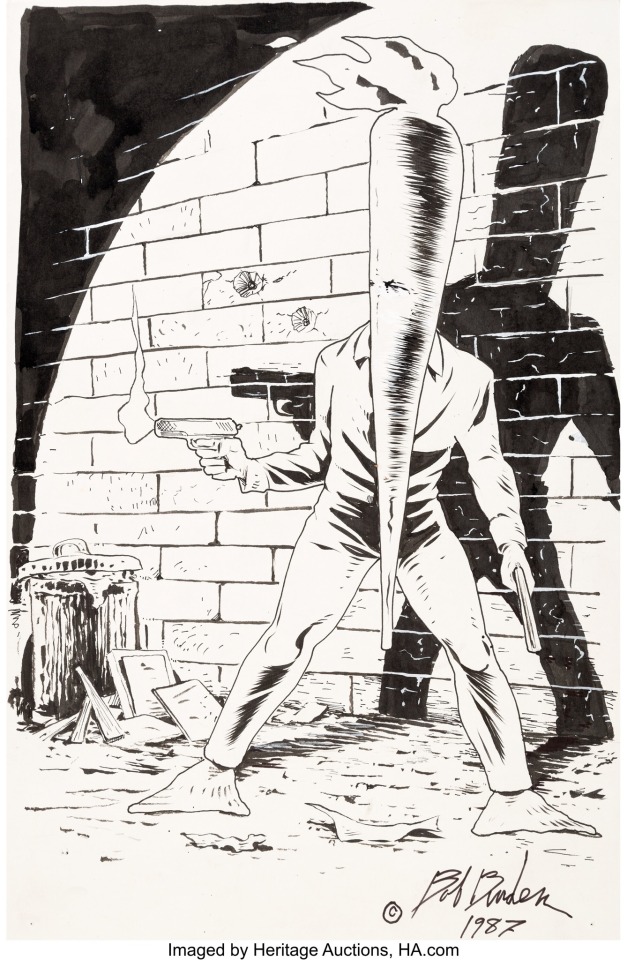

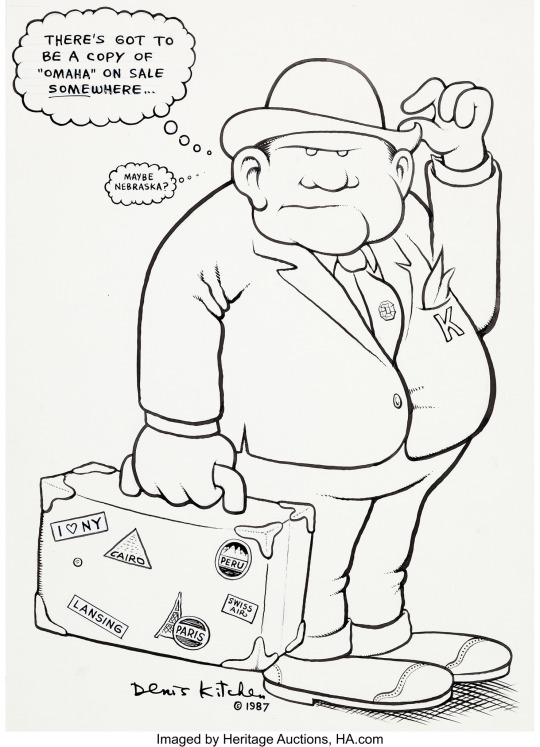

Complete original art from A Benefit Portfolio In Defense of the First Amendment, published by the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, 1987.

From the listing: “In 1986, comic shop clerk Michael Correa was arrested and charged with selling obscene material. Publisher Dennis Kitchen spearheaded a unique project to raise money to help with Correa's legal expenses. This benefit portfolio led to the formation of the non-profit organization The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.” Specific titles cited in the case included Bizarre Sex, Heavy Metal, Weirdo, Omaha the Cat Dancer, and The Bodyssey.

Artwork by:

1. Robert Crumb (this piece was an unpublished cover intended for Weirdo #18)

2. Stephen Bissette

3. Hilary Barta (pencils) and Mitch O’Connell (inks)

4. Sergio Aragones

5. Reed Waller

6. Bob Burden

7. Don Simpson

8. Denis Kitchen

9. Frank Miller (this piece was an unpublished cover intended for Ronin #4)

10. Eric Vincent

#A Benefit Portfolio In Defense of the First Amendment#portfolio#original art#CBLDF#comic book legal defense fund#Robert Crumb#Weirdo#Stephen Bissette#censorship#zipatone#Hilary Barta#Mitch O'Connell#Sergio Aragonés#Groo#Reed Waller#omaha the cat dancer#Michael Correa#comic books#Bob Burden#Flaming Carrot#Don Simpson#Megaton Man#Denis Kitchen#Frank Miller#Ronin#Eric Vincent#Richard Corben#The Bodyssey#Heavy Metal#Bizarre Sex

389 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Forget the Sixth Amendment, which guarantees the “right to a speedy and public trial” in criminal matters. And who needs that ancient Seventh Amendment and its fancy “right of trial by jury.” The U.S. Treasury Department has concluded that American consumers can not be trusted to thoughtfully exercise these Constitutional rights — at least not when doing so might be an annoyance to the financial services sector. This morning, the Treasury released a report [PDF] criticizing the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s recently finalized rule that limits the use of forced arbitration in consumer financial services. What Is Forced Arbitration? Those who read Consumerist frequently are probably familiar with arbitration, but for those who aren’t, here’s a crash course: Go look at the contract/user agreement/terms of service for just about any company you do business with: your bank, credit card company, wireless provider, cable/broadband service, software, e-commerce, electronics, online services… There’s a very good chance that buried deep in that contract is a clause that does two things, neither of which are to your advantage. First, it blocks you from suing that company in court. Instead, you must go through private — often confidential — arbitration. Second, these clauses almost always include a condition barring you from joining your complaint together with other customers who were wronged in the same way, even through arbitration. So Company X can illegally overcharge 10 million customers, but rather than face a single class-action lawsuit representing all 10 million victims, Company X says it’s more convenient to face 10 million individual arbitration hearings. The Reality Except they know that this will never happen. Very few Americans know about or understand the basics of arbitration, so the odds of even a small percentage of those 10 million customers hiring an attorney and arbitrating a dispute is going to be small. Thus, rather than facing a single class-action representing 10 million customers, Company X might face 10 or 15 arbitration claims. And even though each of those few customers might go into arbitration with exactly the same evidence, it’s entirely possible that they could each result in a different decision by the arbitrator. What’s more, it’s likely that no one will know as many arbitration hearings include a gag order preventing the customer from saying anything publicly. If the individual harm done to each customer is small, Company X might also face zero arbitration cases. After all, who is going to hire a lawyer and go through the arbitration process for a $1 overcharge? As federal appeals court Judge Richard Posner noted in Carnegie v. Household Int’l, “only a lunatic or a fanatic sues for $30.” Maybe Company X gives refunds — possibly even a few dollars extra as a “sorry about that” — to the handful of customers that notice and take the time to complain to customer service, but Company X has not been held accountable and made to answer for its apparent crime. Say 100,000 Company X customers realize the overcharge, spend the half an hour on the phone with customer service escalating their complaint, and finally get a refund and another $10 in credit for their troubles (so $11 each). That means Company X has only had to pay out $1.1 million of the $10 million it illegally collected. It’s also avoided the stigma and cost of a criminal or civil defense and possibly avoided having to explain to state or federal prosecutors what happened. This is why critics of forced arbitration have referred to these clauses as “get out of jail free cards” for big businesses. The New Rule The 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reforms not only established the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, but also directed the CFPB to study forced arbitration to determine if it was being abused and needed to be regulated to guarantee that financial institutions were not allowing themselves to sidestep the legal system. After years of research, the CFPB finally finalized its arbitration rule in July 2017. That rule does not outlaw forced arbitration. Rather, it prevents certain financial companies — only those that are directly regulated by the CFPB — from using forced arbitration to block class actions. In the CFPB’s view, this means that banks, credit card companies, and other affected companies could still seek to have legal disputes resolved through arbitration, but they would not be able to minimize their liability for large-scale crimes and mismanagement. The Treasury Disagrees Yet, to the Trump administration — via the new Treasury Department report — making banks accountable for their bad behavior is unacceptable. Claiming that the financial sector will face “extraordinary costs,” the Treasury Department says that restoring consumers’ rights to hold banks’ accountable is not worth the additional 600 class-action lawsuits that might be filed each year, resulting in $100 million a year in additional legal defense fees, and $340 million per year in settlements. That sounds like a lot of money, but when you consider that the ten largest banks in the U.S. have nearly $12 trillion in assets, and that these additional hundreds of class-action lawsuits would be spread out across thousands of affected financial services companies, this is not a rule that banks can’t afford to comply with. Or — and this is just a crazy suggestion — maybe the bad banks that would get sued could stop doing awful things like, opening millions of fake accounts in customers’ names to juke sales figures, and then telling those customers they can’t sue. We’ve Heard This Song Before… The Treasury steals another talking point from the banking lobby when it makes the argument that class actions shouldn’t be allowed because plaintiffs rarely get much money while class-action attorneys get rich (almost as rich as bankers!). “[P]laintiffs who do claim funds from class action settlements receive, on average, $32.35 per person,” reads the Treasury report, which plays up the fact that plaintiffs’ lawyers will make an additional $66 million a year if there is no forced arbitration. Again, that seems like a ridiculous amount of money, but the Treasury glosses over that this is the payout for all class-action attorneys across potentially hundreds of lawsuits. Meanwhile, disgraced Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf, who admitted before Congress that he’d heard about employees opening up fake accounts at least three years before settling with the CFPB over such allegations (and who may have actually been warned about the problem nearly a decade earlier) initially walked away from his position in the midst of the scandal with a compensation package worth $130 million. The bank’s board, facing heavy backlash from lawmakers and the public, eventually clawed back about half of that, but a man who allegedly turned his head while thousands of his employees were defrauding millions of customers still ended up with a golden parachute that was worth all of the additional compensation that all class-action plaintiffs attorneys might see. As for the “small payout to plaintiffs” argument, it glosses over the fact — as described above — that some companies use arbitration clauses to avoid accountability for transgressions that are small on an individual basis but substantial when seen as a whole. But again, maybe the way for the banks to make sure that plaintiffs’ attorneys don’t make all those extra millions is to not screw over their customers? Willful Ignorance? “The Treasury report willfully ignores the fact that class actions returned $2.2 billion to consumers between 2008 through 2012 — after deducting attorneys’ fees and court costs,” says Lisa Donner, executive director, Americans for Financial Reform. “That hardly seems like ‘no relief.’ Donner also points to a study from the Economic Policy Institute, which found that the average consumer who goes to arbitration ends up having to pay their bank or lender $7,725 in fees. “It is clear that consumers derive benefits from class-action lawsuits and lose when forced into secret arbitration,” she says. Just The Latest Attack On Your Rights Bank-backed members of Congress are currently attempting to undo the rule using the Congressional Review Act, a previously little-known federal law that allows Congress to stop any new federal regulations within the first few months after they have been finalized. The House CRA resolution passed on a nearly party-line vote in July, almost immediately after the arbitration rule became official, but it has since stalled in the Senate where it reportedly does not have enough support from moderate Republicans to reach the 50 votes it needs. However, the CRA repeal window for the arbitration rule doesn’t close until early November, so it’s possible the Senate could pounce on it at the last minute. With legislative repeal of the rule in doubt, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce — which is the nation’s biggest lobbying organization, even though some people mistakenly think it’s a governmental agency — recently sued the CFPB in federal court, seeking to halt the rule. The Treasury Department report, which lists no author and does not appear to have been written at the request of any Congressional committee or even the White House, seems to be a de facto legal brief in support of the Chamber of Commerce lawsuit. Or perhaps this is a personal crusade for Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, a former Goldman Sachs banker, who took over collapsed mortgage lender IndyMac in 2009 at the bottom of the Great Recession. As CEO of IndyMac, which changed its name to OneWest under Mnuchin’s leadership, the lender was heavily criticized for overly aggressive foreclosure actions. Between the time Mnuchin’s investor group acquired the IndyMac portfolio and when they sold it in 2015, the company was a defendant in more than 1,500 civil lawsuits filed in federal court. by Chris Morran via Consumerist

http://www.bollywoodnews4free.tk/2017/10/treasury-dept-says-you-shouldnt-have.html

0 notes