#8 june 1972

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

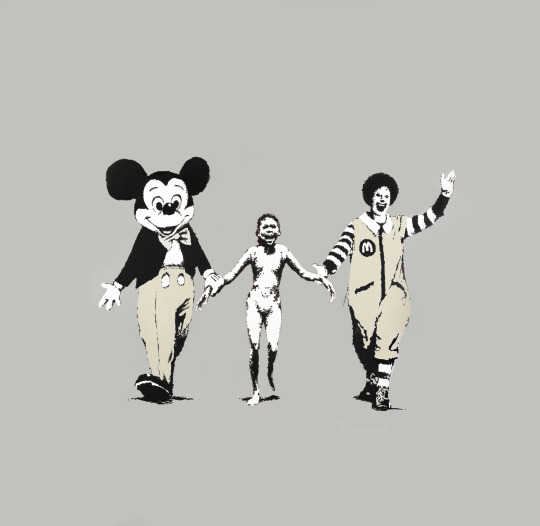

Mickey. Kim. Ronnie.

#banksy#napalm girl#kim phuc#mickey mouse#ronald mcdonald#mickey#ronny#ronnie#mcdonalds#mcdonald#nick ut#nick Út#8 june 1972#1972#vietnam war#usa#nixon#napalm#war#graffityart#graffity

1 note

·

View note

Text

70's Electric Light Orchestra CASHBOX Advertisements 1. May 20th, 1972 2. June 9th, 1973 3. March 16th, 1974 4. July 3rd, 1976 5 and 6. October 23rd, 1976 7. October 9th, 1976 8. November 27th, 1976 9. July 1st, 1978 10. June 23rd, 1979 (via: archive.org)

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

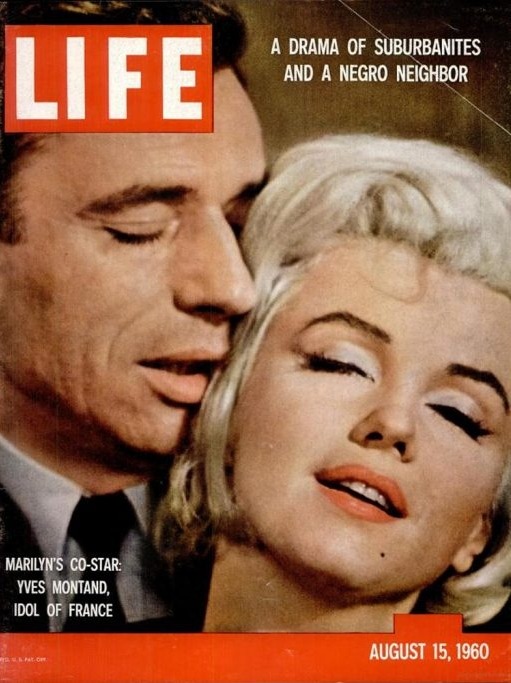

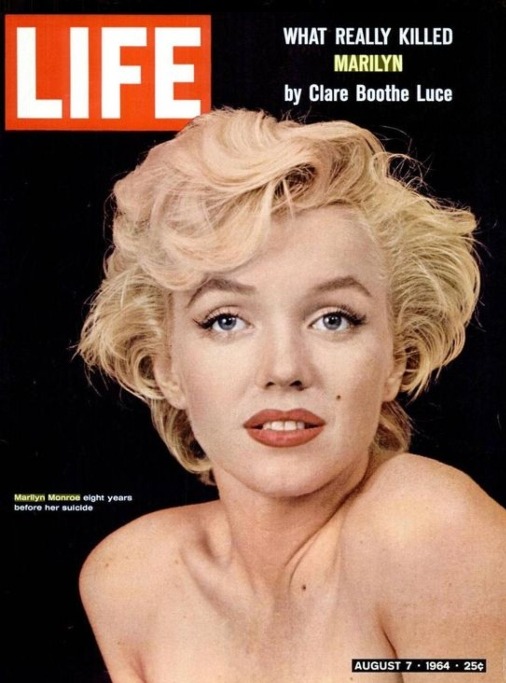

Marilyn Monroe LIFE Magazine Covers

April 7, 1952

May 25, 1953

July 8, 1957 (International Edition)

April 20, 1959

November 9, 1959

August 15, 1960

June 22, 1962

August 17, 1962

August 7, 1964

September 8, 1972

October 1981

August 1982

445 notes

·

View notes

Photo

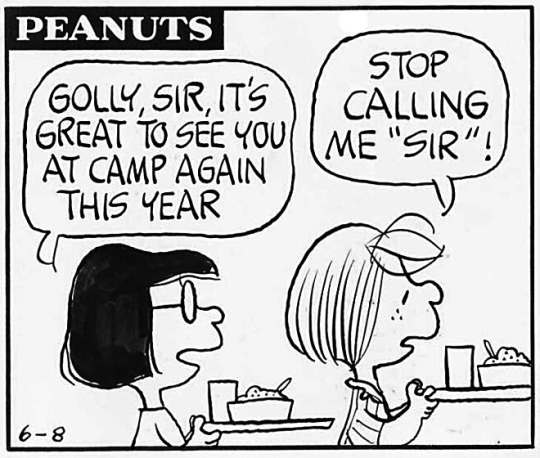

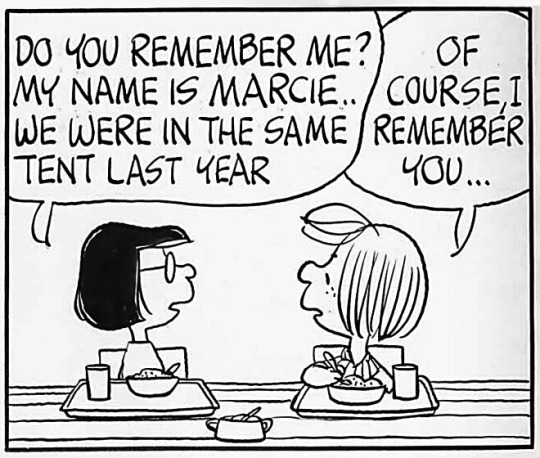

Charles Schulz, Peanuts, June 8, 1972

#charles schulz#peanuts#peppermint patty#marcie#comics#comic strip#vintage comics#70s#1970s#patricia reichardt#illustration#black and white

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Unofficial Comprehensive Age List of Blue Lock Characters from Oldest to Youngest

I made this because of this post I made here as a means to keep me sane, but feel free to reblog to keep it as a reference and stuff!

Oldest

Youngest

1. Buratsuta Hirotoshi — November 7th, 1957 (62) 2. Isagi Issei — May 1st, 1972 (46) 3. Isagi Iyo — January 4th, ???? (43)** 4. Bachira Yu — August 16th, 1981 (37) 5. Noel Noa — April 2nd, ???? (31)** 6. Jinpachi Ego — March 31st, ???? (30)** 7. Dada Silva — October 23rd, ???? (28)** 8. Leonardo Luna — October 31st, ???? (27)** 9. Adam Blake — September 30th, 1992 (26) 10. Pablo Cavasoz — March 7th, ???? (23)** 11. Teieri Anri — August 17th, 1996 (22) 12. Aiku Oliver — June 30th, 1999 (19) 13. Don Lorenzo — July 4th, 1999 (19) 14. Michael Kaiser — December 25th, 1999 (19)* 15. Yukimiya Kenyu — April 28th, 2000 (18) 16. Okawa Hibiki — June 12th, 2000 (18) 17. Baro Shoei — June 27th, 2000 (18) 18. Shido Ryusei — July 7th, 2000 (18) 19. Imamura Yudai — July 15th, 2000 (18) 20. Karasu Tabito — August 15th, 2000 (18) 21. Wanima Junichi — August 20th, 2000 (18) 22. Wanima Keisuke — August 20th, 2000 (18) 23. Sendo Shuto — October 7th, 2000 (18) 24. Itoshi Sae — October 10th, 2000 (18)* 25. Aryu Jyubei — November 3rd, 2000 (18)* 26. Kuon Wataru — November 16th, 2000 (18)* 27. Iemon Okuhito — November 19th, 2000 (18)* 28. Otoya Eita — December 3rd, 2000 (18)* 29. Ishikari Yukio — December 10th, 2000 (18)* 30. Gagamaru Gin — January 2nd, 2001 (18)* 31. Tokimitsu Aoshi — March 21st, 2001 (18)* 32. Nagi Seishiro — May 6th, 2001 (17) 33. Kira Ryosuke — May 23rd, 2001 (17) 34. Julian Loki — June 9th, 2001 (17) 36. Igarashi Gurimu — July 6th, 2001 (17) 37. Bachira Meguru — August 8th, 2001 (17) 38. Mikage Reo — August 12th, 2001 (17) 39. Kiyora Jin — August 31st, 2001 (17) 40. Raichi Jingo — October 11th, 2001 (17)* 41. Tsurugi Zantetsu — October 30th, 2001 (17)* 42. Hiori Yo — November 30th, 2001 (17)* 43. Chigiri Hyoma — December 23rd, 2001 (17)* 44. Kunigami Rensuke — March 11th, 2002 (17)* 46. Isagi Yoichi — April 1st, 2002 (17)* 47. Kurona Ranze — September 6th, 2002 (16) 48. Itoshi Rin — September 9th, 2002 (16) 49. Nanase Nijiro — January 1st, 2003 (16)* 50. Niko Ikki — February 5th, 2003 (16)* 51. Naruhaya Asahi — March 20th, 2003 (16)*

* As Sae has turned 18 after the Second Selection and Isagi has turned 17 sometime during or a bit before the PxG match, it can be assumed that every character with a birthday between was a year younger and has aged up to the ages currently shown on the list sometime in the series.

So basically: Michael Kaiser — December 25th, 1999 (18 → 19) Itoshi Sae — October 10th, 2000 (17 → 18) Aryu Jyubei — November 3rd, 2000 (17 → 18) Kuon Wataru — November 16th, 2000 (17 → 18) Iemon Okuhito — November 19th, 2000 (17 → 18) Otoya Eita — December 3rd, 2000 (17 → 18) Ishikari Yukio — December 10th, 2000 (17 → 18) Gagamaru Gin — January 2nd, 2001 (17 → 18) Tokimitsu Aoshi — March 21st, 2001 (17 → 18) Raichi Jingo — October 11th, 2001 (16 → 17) Tsurugi Zantetsu — October 30th, 2001 (16 → 17) Hiori Yo — November 30th, 2001 (16 → 17) Chigiri Hyoma — December 23rd, 2001 (16 → 17) Kunigami Rensuke — March 11th, 2002 (16 → 17) Isagi Yoichi — April 1st, 2002 (16 → 17) Nanase Nijiro — January 1st, 2003 (15 → 16) Niko Ikki — February 5th, 2003 (15 → 16) Naruhaya Asahi — March 20th, 2003 (15 → 16)

** The birth year and age of these characters are unknown because it is unclear whether these characters have aged into their listed ages or were these ages when introduced, so there is a chance that these ages are now off by one year. Thus, they may be either a year younger and have just turned that age or are all currently a year older because their birthdays have passed now.

In other words: Isagi Iyo — January 4th, 1975 OR 1976 (43 → 44 || 42 → 43) Noel Noa — April 2nd, 1987 OR 1988 (31 → 32 || 30 → 31) Jinpachi Ego — March 31st, 1988 OR 1989 (30 → 31 || 29 → 30) Dada Silva — October 23rd, 1989 OR 1990 (28 → 29 || 27 → 28) Leonardo Luna — October 31st, 1990 OR 1991 (27 → 28 || 26 → 27) Pablo Cavasoz — March 7th, 1995 OR 1996 (23 → 24 || 22 → 23)

Other things to keep in mind:

Blue Lock is supposed to be set in mid/late 2018, and the current events we see take place in 2019. Given that the series has an official setting and official ages with confirmed passage of time with people aging as their birthdays pass, characters should be born during the years listed above.

However, the birth years of certain adults (see above) can be iffy simply because there is a lack of information about them and the exact timeline of events occurring in the series. (E.g. it is known that Isagi turned 17 sometime around the PxG match, but it is unclear whether or not Noel Noa's birthday has also passed despite his birthday being the day after Isagi's.)

What is certain are the birth years of the U-20 players and the Blue Lock participants because U-20 players cannot be older than the maximum age of 20 in the year of the competition to qualify, so their oldest has to be born sometime in '99 to be able to play. As for the Blue Lock participants, the original 300 players were selected from a pool of high schoolers, so they have to be between 15-18, as Japan only has three years of high school, with each grade having a specific age range due to how the school year is arranged to start in April and end in March, as such, 1st years are always 15-16 years old, 2nd years are always 16-17 years old and 3rd years are always 17-18 years old, so everyone had to be born between '00-'03.

Extra things that came to mind as I wrote this:

— As it is currently April in Blue Lock, the 3rd year boys are technically graduated from high school, and the 1st and 2nd years should be the 2nd and 3rd years now. — Depending on how far into April it is, Yukimiya could be or turn 19. — The boys would be around 20-25 years old irl rn.

#bllk#blue lock#if you saw me post this early#bc i misclicked smth#no you didn't LOL#it is also bc of this#that i found#so many timeline discrepancies#at least when comparing irl dates#well some other days too#like Sae turning 18 after the Second Selection#bc the boys were said/thought to move into Blue Lock#on November 20th which is well after Sae's bday#but still before the 2nd Selection so????#regardless i tried my best#for peace of mind really wwww

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

TV Guide - September 19 - 25, 1964

Fall Preview: 1964 - 1965 Shows

ABC

12 O'Clock High (September 18, 1964 – January 13, 1967)

ABC Scope (November 11, 1964 – March 2, 1968)

The Addams Family (September 18, 1964 – April 8, 1966)

Bewitched (September 17, 1964 – March 25, 1972)

The Bing Crosby Show (September 14, 1964 – April 19, 1965)

Broadside (September 20, 1964 – May 2, 1965)

F.D.R. (January 8, 1965 - July 23, 1965)

Jonny Quest (September 18, 1964 – March 11, 1965)

The King Family Show (January 23, 1965 – September 10, 1969)

Mickey (September 16, 1964 – January 13, 1965)

No Time for Sergeants (September 14, 1964 – May 3, 1965)

Peyton Place (September 15, 1964 – June 2, 1969)

Shindig! (September 16, 1964 – January 8, 1966)

The Tycoon (September 15, 1964 – April 27, 1965)

Valentine's Day (September 18, 1964 – May 7, 1965)

Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (September 14, 1964 – March 31, 1968)

Wendy and Me (September 14, 1964 – May 24, 1965)

CBS

The Baileys of Balboa (September 24, 1964 – April 1, 1965)

The Cara Williams Show (September 23, 1964 – April 21, 1965)

The Celebrity Game (April 6, 1964 - September 13, 1964 / April 8, 1965 - September 9, 1965)

The Entertainers (September 25, 1964 –March 27, 1965)

Fanfare (June 19, 1965 - September 11, 1965)

For the People (January 31 – May 9, 1965)

Gilligan's Island (September 26, 1964 – April 17, 1967)

Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. (September 25, 1964 – May 2, 1969)

Many Happy Returns (September 21, 1964 – April 12, 1965)

Mr. Broadway (September 26 – December 26, 1964)

The Munsters (September 24, 1964 – May 12, 1966)

My Living Doll (September 27, 1964 – March 17, 1965)

On Broadway Tonight (July 8, 1964 - March 12, 1965)

Our Private World (May 5 – September 10, 1965)

The Reporter (September 25 – December 18, 1964)

World War One (September 22, 1964 - April 18, 1965)

NBC

90 Bristol Court (October 5, 1964 - January 4, 1965)

Branded (January 24, 1965 – September 4, 1966)

Cloak of Mystery (May 11 - August 8, 1965)

Daniel Boone (September 24, 1964 – May 7, 1970)

The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo (September 19, 1964 – April 24, 1965)

Flipper (September 19, 1964 – April 15, 1967)

Harris Against the World (October 5, 1964 - January 4, 1965)

Hullabaloo (January 12, 1965 – August 29, 1966)

International Showtime (September 15, 1961 - September 10, 1965)

Karen (October 5, 1964 – April 19, 1965)

Kentucky Jones (September 19, 1964 – April 10, 1965)

The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (September 22, 1964 – January 15, 1968)

Moment of Fear (May 19 - September 15, 1964 / 25 May 25 - August 10, 1965)

NBC Wednesday Night at the Movies (September 16, 1964 - September 8, 1965)

Profiles in Courage (November 8, 1964 – May 9, 1965)

The Rogues (September 13, 1964 – April 18, 1965)

Tom, Dick and Mary (October 5, 1964 - January 4, 1965)

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

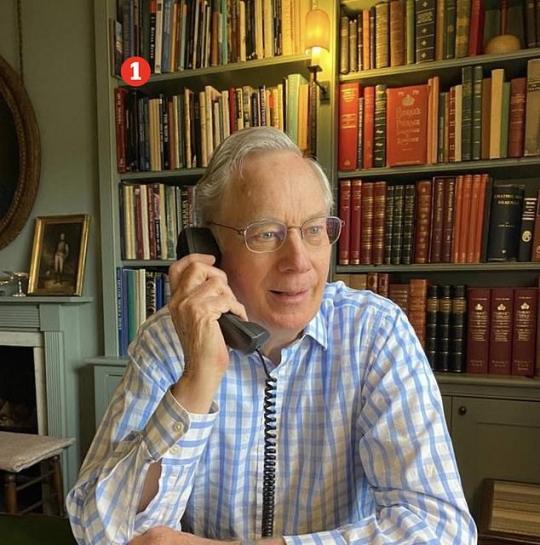

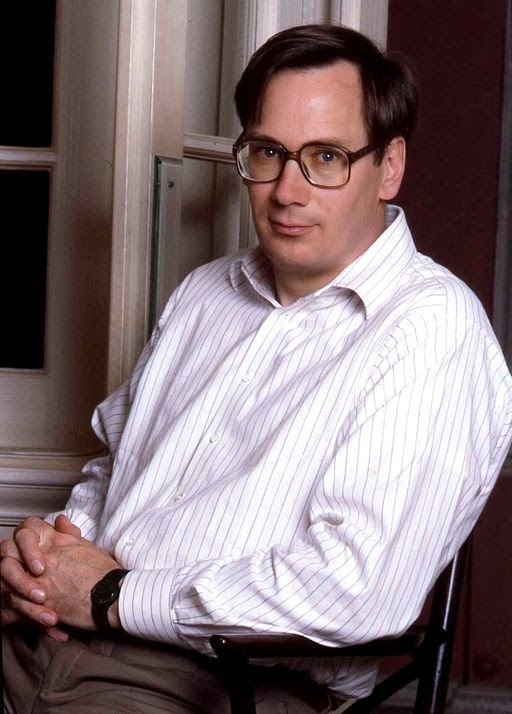

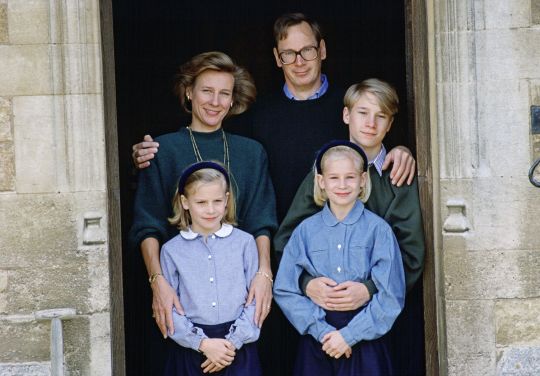

Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester

Physique: Average Build Height: 6′ 0½″ (1.84 m)

Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester (Richard Alexander Walter George; born 26 August 1944) is a member of the British royal family. He is the second son of Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, and Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester, the youngest of the nine grandchildren of George V, nephew of Edward VIII and George VI, and first cousin of Elizabeth II. He is 31st in the line of succession to the British throne, and the highest person on the list who is not a descendant of George VI. At the time of his birth, he was 5th in line to the throne.

Tall, spectacled and reserved looking, he wasn't high in the line of fuckable royals until after the death of Queen Elizabeth II. The Duke isn’t the most handsomest guy being British royalty, but he has that "nerdy hot" thing going on having matured into a fine silverfox.

Prince Richard attended Wellesley House School at Broadstairs and Eton College. In 1963, he matriculated at Magdalene College, Cambridge, where he read architecture, graduating with the degree of Bachelor of Arts in June 1966. In 1966, Richard joined the Offices Development Group in the Ministry of Public Building and Works for a year of practical work. He returned to Cambridge in 1967, completing both parts of the Diploma in Architecture degree in June 1969. Upon passing his exams, he became a practicing architect in London.

After the death of his elder brother, William, he was in direct line to inherit his father's dukedom, to which he succeeded in 1974.

The Duke occasionally represents the royal family at official functions when the monarch can't be there. He also has myriad patronages under his purview, and is the royal family's Trustee of the British Museum.

He married Birgitte van Deurs Henriksen on 8 July 1972; the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester have three children. Other than the fact that I think he's cute and that he was practiced as an architect, I have no other research to offer you.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gaps Between Character Appearances: Flash vol. 1

Basically what it says on the tin: an examination of the longest amounts of time a character was absent for during the Silver/Bronze Age Flash run.

Heroes and Supporting Cast:

Barry Allen: Since he was the main character, Barry was, unsurprisingly, basically in every issue of the Flash. There are therefore no significant gaps in his appearances.

Iris West-Allen: Iris was in pretty much every issue from 1956 to 1979, when she was killed by the Reverse-Flash. She then disappeared from the comic until 1985, when she returned for the end of the Trial of the Flash arc---an absence of six years.

Henry and Nora Allen: Their biggest absence was a seven-year gap between 1966 and 1973. There was then a second large gap between their appearance in 1973 and their reappearance in 1978.

Daphne Dean: Her biggest gap was an 11-year disappearance from 1966 to 1977. She then had another large gap between 1977 and 1982.

Ira West: His biggest gap was a 3-year gap between 1975 and 1978. He then pretty much disappeared from the book entirely after 1979.

Solovar: His biggest absence was a 13-year gap between 1965 and 1978.

Wally West: As Kid Flash, he appeared pretty consistently, either with Barry or on his own, until the very end of the run. The biggest gap is a two-year span between 1981 and 1983.

Patty Spivot: She didn't have any gaps of more than a year at any point between 1977 and and 1984, her full run on the series.

Fiona Webb: Fiona didn't have any gaps of more than a year for her full run on the series, either, which lasted from 1980 to 1985.

Joan Garrick: Her biggest gap in the Flash series was between 1978 and 1982 (the latter of which was her last appearance in Barry's run).

Jay Garrick: His biggest gap is the same 4-year gap as Joan's (between 1978 and 1982). He then disappears from the comic for its last three years (most of which were taken up by the never-ending Trial of the Flash arc).

Dexter Myles: His biggest gap was a roughly three-year period between 1970 and 1973.

Villains:

Professor Zoom the Reverse-Flash: The biggest gap in appearances he had prior to his death was the 5-year gap between 1969 ("Time Times 3 Equals--?") and 1974 ("Green Lantern---Master Criminal of the 25th Century"). After his death in 1980, he effectively disappeared for 3 years, reappearing in 1983 only to die again.

Abra Kadabra: His biggest gap in appearances was the five-year gap between 1972 ("The Flash in Cartoon-Land!") and 1977 ("Kill Me, Flash--Faster, Faster!"). There was also a 4-year gap between 1968 ("The Thief Who Stole All the Money in Central City") and 1972.

Gorilla Grodd: Grodd was absent for seven years, between 1971 (“Beyond the Speed of Life!”, otherwise known as the issue where Digger and James trip the Flash and he dies) and 1978 (“Beyond the Super-Speed Barrier").

Captain Cold: Captain Cold had two fairly sizeable gaps between appearances: a five-year gap between 1969 ("Captain Cold Blows His Cool") and 1974 ("The Hot-Cold War in Central City!"), and a four-year gap between 1977 ("To Believe or Not to Believe!") and 1981 ("Captain Cold's Cold, Cold Flame"). There was also a 3-year gap between his appearance in Showcase #8 and his appearance in Flash #114.

Mirror Master: Mirror Master had a number of two-year gaps between appearances, but never anything more than that. He was the most consistently appearing Flash villain.

Heat Wave: The biggest gap for Heat Wave was basically the same as for Captain Cold---a five-year gap between 1969 and 1974.

Captain Boomerang: Digger disappeared for four years between 1967 ("The Stupendous Triumph of the Six Super-Villains") and 1971 ("Beyond the Speed of Life!"). He was also missing for a 3-year period between 1976 (“The Last Day of June is the Last Day of Central City!”) and 1979 ("Road to Oblivion!").

Trickster: Trickster had a number of 3-year gaps between appearances---between 1965 ("The Trickster's Toy Thefts") and 1968 ("The Swell-Headed Super Hero"), between 1968 and 1971 ("Beyond the Speed of Life!"), between 1971 and 1974 ("The Day I Saved the Flash!", also known as writer Cary Bates' self-insert fanfic), between 1977 ("Prisoner of the Past") and 1980 ("If, At First You Don't Succeed"), and between 1980 and 1983 ("Dead Reckoning").

Weather Wizard: Weather Wizard was absent for six years, from 1967 ("The Race to the End of the Universe") to 1973 ("The Heart that Attacked the World").

Pied Piper: Hartley was absent from 1967 ("The Stupendous Triumph of the Six Supervillains") to 1972 ("The Flash of 1000 Faces"), a gap of five years. He also had a roughly four-year gap between 1977 ("Prisoner of the Past") and 1981 ("The Pied Piper's Paradox Peril"), and a 4-year gap between his first appearance in 1959 and his second appearance in 1963.

The Top: Roscoe was absent for six years, from 1967 ("The Stupendous Triumph of the Six Supervillains") to 1973 ("The Million-Dollar Death Trap!"). He was then basically absent from his death in 1976 to his return as a ghost in 1981, a five-year gap. His last appearance in the comic was in November 1981.

Golden Glider: Her biggest gap was a three-year absence from 1978 (“The Golden Glider’s Final Fling!”) to 1981 ("1981--A Flash Odyssey!"). Her last appearance in the comic was in October 1982.

Rainbow Raider: His biggest gap was a year-and-a-half-to-two year gap between 1981 ("A Stab in the Black!") and 1983 ("Trade Heroes and Win!").

Mr. Element/Dr. Alchemy: There was a six-year gap between Dr. Alchemy's appearance in 1958 ("The Man Who Changed the Earth!") and Mr. Element's appearance in 1964 ("Our Enemy, the Flash!"). Albert Desmond disappeared again from 1966 ("One Bridegroom Too Many!”) to 1972 ("The Curse of the Dragon’s Eye!”), a roughly six-year gap. He also disappeared for another six years between 1974 (“The Fury of the Fire-Demon!”) and 1980 (“Dr. Alchemy and Mr. Desmond"). His last appearance in the series was in September 1980. Alvin only appeared from July to September 1980 during Barry's run, and as such there were no gaps between his appearances.

Paul Gambi: Paul was absent for 10 years between 1963 and 1973, and then had a 9-year gap between 1976 and 1985.

Among the villains, Grodd had the biggest gap between his appearances, since he was gone from the pages of the Flash for seven years. Albert Desmond had the most frequent long absences, though, with three different six-year gaps.

Among the Rogues proper, The Top and the Weather Wizard had the largest gaps between appearances, though the Top's death meant that he was gone for more of the series than Weather Wizard.

#flash comics#flash rogues#the flash#barry allen#iris west#wally west#daphne dean#henry allen#nora allen#fiona webb#dexter myles#paul gambi#professor zoom the reverse flash#gorilla grodd#dr. alchemy#mr. element#albert desmond#alvin desmond#mirror master#the top#captain boomerang#pied piper#heat wave#weather wizard#golden glider#rainbow raider#the trickster

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The M*A*S*H Time Loop

This was pretty much just a stream of consciousness writing. I haven't looked at it much since I wrote it a couple of days ago but I wanted to post it anyway.

The sitcom M*A*S*H ran from 1972 to 1983 and captured households around America. The series follows M*A*S*H (Mobile Army Surgical Hospital) unit 4077 through the Korean War. Knowledgable readers might have noticed that the Korean War lasted 3 years from June 1950 to July 1953 while the M*A*S*H series ran for 11 years from September 1972 to February 1983. This significant timeline difference created an interesting effect on M*A*S*H that led to many fans discussing the ‘M*A*S*H time loop theory.’ As the name would imply, this fan theory posits that the events of M*A*S*H do not take place during the Korean War as we know it, but instead that the show follows the 4077th as they are stuck in an endless time loop and are unable to escape the war.

Clearly, the timeline of M*A*S*H is a bit difficult to line up with the events of the actual Korean War due to the 8-year difference. Characters such as BJ Hunnicutt and Radar O’Riley were on the sitcom for 8 years but canonically it is difficult to say if they were meant to have spent the same amount of time in Korea. While the episodes were aired weekly, it is impossible to say if most of the episodes were meant to take place a week apart. There are several episodes for which we know this is not the case, for example, the season 9 episode ‘A War for All Seasons’ begins with the 4077th ringing in the new year and follows several key events throughout 1951 and ends on New Year’s Day 1952. This seems to imply that the previous 8 seasons all take place in 1950. It could also imply that subsequent episodes all take place in 1952 or later, though many assume that some episodes show events that were not seen in ‘A War for All Seasons.’ On the opposite end of the spectrum, several episodes take place over a matter of hours. The season 8 episode ‘Life Time’ happens essentially in real time as Hawkeye has only 20 minutes to complete an arterial graft on a wounded soldier. These and other episodes make creating a sensible timeline for the M*A*S*H series an incredibly complicated process. Trapper John leaves in the first episode of season 4, does this mean that he was only in Korea for 6 months? As mentioned earlier, Radar and BJ were on M*A*S*H for the same number of years, but Radar leaves before ‘A War for All Seasons,’ does this mean that Radar was enlisted for a year or less while BJ was present for 2 years? Does it matter how long any of these characters were engaged in the Korean War? The time loop theory certainly says no.

The nature of all sitcom television lends itself very well to the concept of a time loop. The show almost always resets itself at the end of every episode and it begins the next episode in essentially the same place. The order of the episodes often doesn’t matter. Everything is always happening, nothing happens, it doesn’t matter. In M*A*S*H specifically, one of the core themes of the show is the cyclical nature of war. It intentionally pokes fun at the repetition, the monotony with lines like ‘the future’s been canceled by the war department’ and ‘Father, what do you think of purgatory so far?’ as well as with aspects such as the omnipresent PA voice. Hawkeye Pierce becomes the main focus of the show and the audience's lens in many ways and as such is one of the easiest introductions to this concept. Hawkeye complains about being stuck nearly every episode and often phrases it as though he is not just stuck as a surgeon in a war zone, but as if his whole life is stuck, as if his past and future are all contained within the war. Another character giving credence to this theory is Radar O’Riley. Radar earned his nickname due to his uncanny ability to sense incoming wounded before anyone else and to predict what his commanding officers will ask for before they open their mouths. While this is certainly a fun gag for the show, many think it shows that Radar is aware, consciously or unconsciously, of the time loop. Radar is aware of when the choppers will arrive and when Henry needs files because it has all happened before and will happen again. Many fans also point out that this could be the reason for Radar’s reaction to Henry being sent home. It is more than just realizing that he will be left in Korea while the man he has come to see as a father figure goes home to his family. On some level, Radar remembers that Henry will not make it home; he knows he can not stop it. Of course one of the biggest pieces of evidence against the idea of a time loop is the fact that it does end. Everyone goes home in the end, however, this does not entirely disprove the theory. Many pieces of media that focus on the concept of time loops end with our protagonists escaping. But they can not escape entirely. Though all of our characters leave Korea by the end of the series, those who are still alive have not left completely. They will be stuck remembering this time forever.

While the original intention of M*A*S*H certainly was not to tell a story about a group of army doctors, nurses, and enlisted men trapped in a time loop, that is in many ways the story we got. It is the best showcase of the cycle, the monotonous horror of war in modern media. The only changes come with tragedy, death, or abandonment. It is a time loop in the only ways that matter.

#mash#m*a*s*h#mash 4077#m*a*s*h 4077#mash time loop#mash timeloop#time loop#timeloop#time loop theory#timeloop theory#hawkeye pierce#hawkeye#benjamin franklin pierce#bj hunnicutt#beej#radar o'reilly#walter o'reilly#trapper john mcintyre#trapper john#trapper mcintyre#trapper#mash writings#mash essay#mash theory#henry blake#sherman potter#margaret houlihan#mash analysis#m*a*s*h analysis

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

August 8, 2024

Heather Cox Richardson

Aug 09, 2024

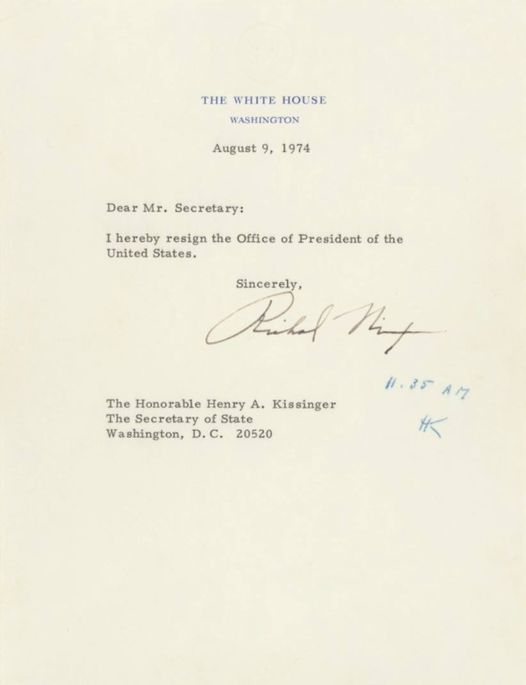

Fifty years ago, on August 9, 1974, Richard M. Nixon became the first president in U.S. history to resign.

The road to that resignation began in 1971, when Daniel Ellsberg, who was at the time an employee of the RAND Corporation and thus had access to a top-secret Pentagon study of the way U.S. leaders had made decisions about the Vietnam War, leaked that study to major U.S. newspapers, including the New York Times and the Washington Post.

The Pentagon Papers showed that every president from Harry S. Truman to Lyndon B. Johnson had lied to the public about events in Vietnam, and Nixon worried that “enemies” would follow the Pentagon Papers with a leak of information about his own decision-making to destroy his administration and hand the 1972 election to a Democrat.

The FBI seemed to Nixon reluctant to believe he was being stalked by enemies. So the president organized his own Special Investigations Unit out of the White House to stop leaks. And who stops leaks? Plumbers.

The plumbers burglarized the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in California, hoping to find something to discredit him, then moved on to bigger targets. Together with the Committee to Re-elect the President (fittingly dubbed CREEP as its activities became known), they planted fake letters in newspapers declaring support for Nixon and hatred for his opponents, spied on Democrats, and hired vendors for Democratic rallies and then scarpered on the bills. Finally, they set out to wiretap the Washington, D.C., headquarters of the Democratic National Committee, in the fashionable Watergate office complex.

Early in the morning of June 17, 1972, Watergate security guard Frank Wills noticed that a door lock had been taped open. He ripped off the tape and closed the door, but on his next round, he found the door taped open again. Wills called the police, who arrested five men ransacking the DNC’s files.

The White House immediately denounced what it called a “third-rate burglary attempt,” and the Watergate break-in gained no traction before the 1972 election, which Nixon and Vice-President Spiro Agnew won with an astonishing 60.7% of the popular vote.

But Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, two young Washington Post reporters, followed the sloppy money trail back to the White House, and by March 1973 the scheme was unraveling. One of the burglars, James W. McCord Jr., wrote a letter to Judge John Sirica before his sentencing claiming he had lied at his trial to protect government officials. Sirica made the letter public, and White House counsel John Dean immediately began cooperating with prosecutors.

In April, three of Nixon’s top advisors resigned, and in May the president was forced to appoint former solicitor general of the United States Archibald Cox as a special prosecutor to investigate the affair. That same month, the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, informally known as the Senate Watergate Committee, began nationally televised hearings. The committee’s chair was Sam Ervin (D-NC), a conservative Democrat who would not run for reelection in 1974 and thus was expected to be able to do the job without political grandstanding.

The hearings turned up the explosive testimony of John Dean, who said he had talked to Nixon about covering up the burglary more than 30 times, but there the investigation sat during the hot summer of 1973 as the committee churned through witnesses. And then, on July 13, 1973, deputy assistant to the president Alexander Butterfield revealed the bombshell news that conversations and phone calls in the Oval Office had been taped since 1971.

Nixon refused to provide copies of the tapes either to Cox or to the Senate committee. When Cox subpoenaed a number of the tapes, Nixon ordered Attorney General Elliot Richardson to fire him. In the October 20, 1973, “Saturday Night Massacre,” Richardson and his deputy, William Ruckelshaus, refused to execute Nixon’s order and resigned in protest; it was only the third man at the Justice Department—Solicitor General Robert Bork—who was willing to carry out the order firing Cox.

Popular outrage at the resignations and firing forced Nixon to ask Bork—now acting attorney general—to appoint a new special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, a Democrat who had voted for Nixon, on November 1. On November 17, Nixon assured the American people that “I am not a crook.”

Like Cox before him, Jaworski was determined to hear the Oval Office tapes. He subpoenaed a number of them. Nixon fought the subpoenas on the grounds of executive privilege. On July 24, 1974, in U.S. v. Nixon, the Supreme Court sided unanimously with the prosecutor, saying that executive privilege “must be considered in light of our historic commitment to the rule of law. This is nowhere more profoundly manifest than in our view that 'the twofold aim (of criminal justice) is that guilt shall not escape or innocence suffer.'... The very integrity of the judicial system and public confidence in the system depend on full disclosure of all the facts….”

Their hand forced, Nixon’s people released transcripts of the tapes. They were damning, not just in content but also in style. Nixon had cultivated an image of himself as a clean family man, but the tapes revealed a mean-spirited, foul-mouthed bully. Aware that the tapes would damage his image, Nixon had his swearing redacted. “[Expletive deleted]” trended.

In late July 1974, the House Committee on the Judiciary passed articles of impeachment, charging the president with obstruction of justice, abuse of power, and contempt of Congress. Each article ended with the same statement: “In all of this, Richard M. Nixon has acted in a manner contrary to his trust as President and subversive of constitutional government, to the great prejudice of the cause of law and justice and to the manifest injury of the people of the United States. Wherefore Richard M. Nixon, by such conduct, warrants impeachment and trial, and removal from office.”

And then, on August 5, in response to a subpoena, the White House released a tape recorded on June 23, 1972, just six days after the Watergate break-in, that showed Nixon and his aide H.R. Haldeman plotting to invoke national security to protect the president. Even Republican senators, who had not wanted to convict their president, knew the game was over. A delegation went to the White House to deliver the news to the president that he must resign or be impeached by the full House and convicted by the Senate.

In his resignation speech, Nixon refused to acknowledge that he had done anything wrong. Instead, he told the American people he had to step down because he no longer had the support he needed in Congress to advance the national interest. He blamed the press, whose “leaks and accusations and innuendo” had been designed to destroy him. His disappointed supporters embraced the idea that there was a “liberal” conspiracy, spearheaded by the press, to bring down any Republican president.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Letters From An American#Heather cox Richardson#Nixon#history#American History#the presidency#Watergate

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Aug. 8, 1974, Republican U.S. President Richard Nixon shocked the nation. Following more than a year of multiple investigations into his administration over the Watergate scandal, Nixon went on television and announced that he would be resigning from office the following day.

“To continue to fight through the months ahead for my personal vindication would almost totally absorb the time and attention of both the president and the Congress in a period when our entire focus should be on the great issues of peace abroad and prosperity without inflation at home,” Nixon said as the nation watched. “Therefore, I shall resign the presidency effective at noon tomorrow.”

Less than two years earlier, Nixon had defeated South Dakota Sen. George McGovern, the Democratic Party’s candidate, in a landslide victory that pundits had compared to former President Franklin Roosevelt’s historic reelection in 1936. But now, Nixon became the first president in the nation’s history to step down before finishing his term. Americans were stunned and relieved. But even as Nixon’s administration has come to represent the ultimate rupture of a presidency, his was in fact the third consecutive administration to end in disruption in the mid-20th century. John F. Kennedy had been assassinated in November 1963. Lyndon Johnson had unexpectedly withdrawn from his reelection campaign in 1968. And then, six years later, Nixon would resign.

Nor was the outcome inevitable, as it may seem today. Nixon had fought when Congress, a grand jury, special prosecutors, judges, and reporters tried to find out what his role had been in the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in June 1972, and whether he had obstructed subsequent investigations. Just a few days before Nixon’s announcement, a mere 31 percent of Republicans polled by Gallup felt that he should no longer hold the office.

The pressure had mounted. On July 24, in United States v. Nixon, the Supreme Court ruled that the president must turn over secret White House tape recordings—one of which contained a “smoking gun” in which legislators could hear him in a conversation with advisor H.R. Haldeman, agreeing that they should persuade the CIA to stop the FBI from looking into the matter. On Aug. 7, Sen. Barry Goldwater, Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott, and House Minority Leader John Rhodes—all Republicans—met with Nixon and said that if the House voted to send them articles of impeachment, which seemed likely, many in the GOP would join the Democrats in voting to remove him from office. Nixon’s job approval, according to Gallup, fell to 24 percent, with more than a majority of the country thinking he should leave. That’s what he did.

On Aug. 9, at 9:31 a.m., the president entered into the East Room with the first lady, Pat Nixon, and addressed a small group of cabinet officials, friends, and supporters. As he held back tears during different moments of his talk, Nixon advised everyone who was surrounding him: “Aways give your best. Never get discouraged, never be petty. Always remember, others may hate you, but those who hate you don’t win unless you hate them, and then you destroy yourself.”

He then went down to the Diplomatic Reception Room, where he wished the new president, Gerald Ford, good luck. Nixon walked up the staircase to the helicopter that was waiting for him outside, turned to look at the White House one last time as president, waved with his fingers shaped as a “V” for victory, and then flew off to Andrews Air Force Base, where Air Force One brought him back to California.

“With his departure,” wrote Jules Witcover in the Washington Post on Aug. 9, “he leaves behind a political legacy of negativism that far transcends the damage to his own party.”

Nixon’s presidency came to an abrupt end, but the resignation was just the final stage of a tumultuous era. The nation had been embroiled in fierce internal battles over issues such civil rights and the war in Vietnam. College campuses had been rocked by ongoing protest. Even the clothing that a person chose to wear sent strong signals about what they stood for. The Democratic Convention in August 1968 in Chicago had been a fiasco. The whole world watched as anti-war activists clashed with Mayor Richard Daley’s police force; inside the convention, anti-war delegates fought with supporters of then-Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who had become the nominee when Johnson withdrew from the race

And all of this took place after there had been a series of assassinations that started with Kennedy. When Martin Luther King Jr. was killed in Memphis, Tennessee, in April 1968, unrest swept through major cities. When an assassin killed one of the late president’s brothers, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, in June, many young people lost all hope.

It is not a surprise that in 1974, Knopf published Robert Caro’s The Power Broker, a masterful work that would come to be considered one of the greatest nonfiction books of the century. Caro traced the career of the legendary unelected civil servant Robert Moses, who started his career as an idealistic reformer but ended as someone who did whatever was necessary, and to whomever, in his quest for total power. “The real lesson of Moses’ career,” wrote a reviewer in the Los Angeles Times, “and it is not nearly so difficult to understand in light of recent events such as Watergate—is the way the techniques of opinion manipulation and power use can operate within democracy.”

But another perspective suggested that perhaps Nixon’s resignation demonstrated that “the system worked,” with the optimists wanting to believe that a scandalous president being forced to give up power would restore the trust in government and elected officials that Vietnam and Watergate had stolen from them.

“No one can rejoice in the events which culminated in the resignation of the President,” noted American Bar Association President Chesterfield Smith in a newspaper interview. “We can, however, find comfort in the fact that … when our system for the administration of justice was tested—by perhaps its greatest challenge of all time—that system proved equal to the task.”

Such feelings did not last long. History took a different turn, and public distrust of government worsened. In 2024, Americans have trouble believing that their leaders will serve the public interest. According to Pew, a mere 22 percent trust the federal government to do what is right “just about always.” Though there have been some moments of improvement, such as at times during Ronald Reagan’s presidency and in the years immediately after 9/11, the public trust percentages upward of 70 percent that were normative in the early 1960s currently feel impossible to recreate. Even in recent years, when trust has grown slightly higher, positive numbers remain far lower than before.

So why didn’t Nixon’s resignation make things better? How did an act of such massive historical weight fail to cure the ills that were afflicting the body politic?

To begin with, Richard Nixon was never held accountable. Just one month after he told Americans that he was stepping down, his successor, Ford—who Nixon had appointed to be his vice president in 1973, when Spiro Agnew resigned in scandal—pardoned Nixon for any crimes that he might have committed. Seeking to heal the nation, Ford did the opposite. Nixon, who in 1977 told television interviewer David Frost that if a president did something, then it was legal, went on to have a career writing books and giving advice to future leaders. Rather than a criminal, he was treated as a statesman.

Public distrust also never went away because Vietnam and Watergate created a more vigilant outlook, with institutional support, as more people on both the left and right were constantly on the lookout for wrongdoing. Investigative journalists, nonprofit organizations, and good government groups such as a Common Cause were determined to keep holding elected officials accountable. So Americans naturally learned more about the bad things that politicians could do, such as when Sen. Frank Church’s committee revealed the illicit activities of the CIA during the Cold War, as the forces of reform struggled to clean the government so that it work be better. The quest for improvement tapped into a distrust of government that had always been part of the United States since its founding, when the country was created in a rebellion against a corrupt and oppressive British government.

Had this healthy skepticism been balanced with messages about the virtues of what Washington could do, such as when elderly Americans received health care through Medicare or poor young kids received nutrition through school lunch programs, public opinion might have improved. But instead, a conservative movement swept through the nation. Conservatism targeted the ills of government. As Reagan declared in his inaugural address, “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

These feelings only intensified as more conservatism became more entrenched in politics and as the United States moved further away from Roosevelt’s New Deal and Johnson’s Great Society. Even some Democratic leaders such as President Bill Clinton, though still liberal, embraced Reagan’s logic as well. During his State of the Union address in 1996, Clinton proclaimed that “the era of big government” was “over.”

As if all of this was not enough, the intensification of hyperpolarization over the past two decades has caused red and blue Americans to distrust officials from the other side. To be sure, strong partisanship is a good thing. Robust parties offer Americans real mechanisms within the mainstream political system to express differences and to struggle over policy. Parties have helped to provide coherence to the country’s incredibly fragmented government.

But when “affective polarization” became normative, as political scientist such as Liliana Mason have argued, intense emotionalism left members of each party disliking the other and disgusted by their opponents to the point that there could be no reconciliation. Fundamental differences have been supplanted by fundamental distrust. And social media has created multiple opportunities to spread all kind of information regardless of its veracity, which further fuels these feelings.

Besides the sorts of tensions that this culture of distrust has created, the sentiment also makes it more difficult for the government that we all need to survive, thrive, and do good work.

Rather than hoping that somehow conditions will miraculously change, the time has come for a new reform agenda, where the country’s elected officials take the concerns that were at the root of the good-faith skepticism that took hold when Nixon stepped down. Instead of just railing against those in charge, Americans need more dialogue about improving processes, procedures, and rules—while demanding better leadership—in order to produce a government that is always looking out for the national interest.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fear #8 (June 1972) cover by John Severin.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy 48th wedding anniversary to King Carl XVI Gustaf and Queen Silvia of Sweden!

The couple tied the knot on June 19 1976 at the Stockholm Cathedral, having met 4 years prior at the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich; Silvia was assigned to be Carl Gustaf's translator during the games. Carl Gustaf acceded to the throne in the following year following the death of his grandfather.

Their engagement was announced on March 12 1976; the King proposed with a 2-carat ring that belonged to his late mother.

Their chosen date of June 19 is a symbolic date for the Bernadotte family and one in which multiple family members have gotten married on, including Carl Gustaf and Sofia's eldest daughter, Crown Princess Victoria.

They have three children and eight grandchildren: Crown Princess Victoria, Duchess of Västergötland (46), mother of Princess Estelle (12) and Prince Oscar (8); Prince Carl Philip, Duke of Värmland (45), father of Prince Alexander (8), Prince Gabriel (6) and Prince Julian (3); and Princess Madeleine, Duchess of Hälsingland and Gästrikland, (42), mother of Princess Leonore (10), Prince Nicolas (9) and Princess Adrienne (6).

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Banksy

“Can’t Beat That Feeling”, 2014. The unauthorized retrospective, S/2 London, Curated by Steve Lazarides

Nick Ut (VD, 1951)

Phan Thị Kim Phúc (1963), the girl in the picture/napalm girl. Pulitzer Prize photo "The Terror of War", Trảng Bàng, June 8, 1972 by Vietnamese-American photographer Nick Ut for the Associated Press

[eucanthos' hi res img recontsruction from sotheby's]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phan_Thi_Kim_Phuc#Activism

https://banksyexplained.com/napalm-2004-2/

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays (bc I can)

I put my own fancasts and my headcannon b-day'

Euphemia Braithewaite-Potter - January 4, 1907

Walburga Irma-Black - April 17, 1907

Fleamont Potter - May 15, 1909

Charlus Potter (Monty' brother) - August 19, 1900

Lucretia Black (Orion' sister) - August 3, 1914

Orion Black - September 30, 1920

Druella Rosier (Axel' sister) - December 31, 1928

Axel Rosier (Rosier twins dad) - November 14, 1930

Cygnus Black (Black sisters dad) - July 30, 1938

Adele Jacob-Rosier (Rosier twins mom) - June 7, 1938

Alphard Black - June 26, 1925

Rodolphus Lestrange - October 19, 1952

Rabastan Lestrange- September 21, 1954

Lucius Malfoy - July 1, 1954

Enid Pettigrew (Peter' sister) - January 30, 1962

Mason McKinnon (Marlene' brother) - December 20, 1952

Mitchell McKinnon (Marlene' brother) - June 25, 1955

Matthew McKinnon (Marlene' brother) - November 7, 1958

Maxwell McKinnon (Marlene' brother) - February 29, 1962

Petunia Evans-Dursley - January 10, 1958

Mavan Rosier (Rosier twins brother) - March 14, 1965

Annabella Rosier (Rosier twins sister) - April 16, 1968

Elizabeth Meadows (Dorcas' sister) - May 1, 1965

Fabian Prewett - September 30, 1958

Gideon Prewett - September 30, 1958

Molly Prewett-Weasley - October 30, 1949

Billius Weasley (Arthur' brother) - May 26, 1952

Arthur Weasley - February 6, 1950

James Potter - March 27, 1960

Remus Lupin - March 10, 1960

Sirius Black - November 3, 1960

Peter Pettigrew - August 31, 1960

Lily Evans-Potter - January 30, 1960

Mary Macdonald - September 16, 1959

Marlene McKinnon - August 1, 1960

Dorcas Meadows - April 2, 1960

Bartemius Crouch Jr. - July 9, 1961

Evan Rosier - June 20, 1961

Pandora Rosier - June 20, 1961

Regulus Black - December 31, 1961

Alice Fortescue-Longbottom - August 14, 1960

Frank Longbottom - September 14, 1959

Ted Tonks - March 20, 1953

Emmeline Vance - July 18, 1957

Rita Skeeter - December 19, 1951

Ophelia Zabini - January 15, 1951

Emma Vanity - February 28, 1960

Andromeda Black - October 10, 1953

Narcissa Black - July 19, 1955

Bellatrix Black - May 2, 1991

Tom Riddle Jr. - February 19, 1979

Mattheo Riddle - January 20, 1980

Aliana Riddle - January 20, 1980

Mandy Lestrange - March 13, 1985

Cara Lestrange - May 23, 1986

Delphini Riddle - August 16, 1987

Lorenzo Berkshire - December 17, 1996

Nymphadora Tonks - October 8, 1973

Nina Tonks (Nymphadora' sister) - June 13, 1978

Lucas Rosier (Rosekiller child) - July 21, 1985

Nicholas Rosier (Rosekiller child) - July 1, 1987

Draco Malfoy - June 5, 1980

Lila Malfoy (Draco' sister) - June 5, 1980

Artemis McKinnon (Dorlene child) - September 13, 1981

Aries McKinnon (Dorlene child) - October 17, 1982

Jack McKinnon (Dorlene child) - January 23, 1987

Harry Potter - July 31, 1980

Lillian Potter (Harry' sister) - July 31, 1980

Rose Potter (Harry' sister) - May 24, 1981

Leo Potter (Harry' brother) - February 16, 1983

Pansy Parkinson - August 1, 1980

Blaise Zabini - November 1, 1980

Teddy Lupin - April 11, 1985

Neville Longbottom - July 30, 1980

Juliana Longbottom (Neville' sister) - October 15, 1986

Nicky Longbottom (Neville' brother) - October 15, 1986

Penelope Vance (Emmary child) - November 12, 1988

Hermione Granger - September 19, 1980

Violet Granger (Hermione' sister) - May 14, 1979

Bill Weasley - November 29, 1970

Charlie Weasley - December 12, 1972

Percy Weasley - August 22, 1976

Fred Weasley - April 1, 1978

George Weasley - April 1, 1978

Ron Weasley - March 1, 1980

Ginevra Weasley - August 11, 1981

Luna Lovegood - February 13, 1981

Eclipse Rosier (Pandalily child or Luna' sister) - January 11, 1985

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay @scarlet-bitch (hope you don’t mind the tag) this is the very basic like timeline of that thing I mentioned. It’s a super crossover xD

—//—//—//—

1917

James “Bucky” Barnes is born March 10

Howard Stark is born August 15

1918

Steve Rogers is born July 4

1921

Margaret “Peggy” Carter is born April 21

1930

Eric Lehnsherr is born May 25

1932

Charles Xavier is born July 13

1939

Howard Stark starts up Stark Industries

1950

Nick Fury is born July 4

1954

John Winchester is born April 22

Mary Winchester is born December 4

1956

David Rossi is born May 9

1958

Henry Winchester stumbles upon a mutant/human co-op trying to force mutations in humans. He is saved by an undercover CIA agent and forced into Witness Protection without his wife and child. The CIA agent has betrayed the CIA and is instead working with the co-op.

The CIA agent, calling herself Abbadon, starts to subtly threaten Millie.

1960

Harold Finch (Thomas) is born April 9

1962

Abbadon injects John with a prototype serum that is supposed to force a mutation out of him. It seems to fail.

Nathan Ingram is born June 6

Olivia Manx is born July 5

1964

Phil Coulson is born July 8

1965

Abbadon scares Millie, who believes that she has hidden John’s existence from Abbadon as the ex-CIA agent never threatens him, away. Millie leaves John with her sister Maisy. She takes on the name Maria.

Millie meets and falls in love with Howard Stark.

Nathan Ford is born August 16

Carl Elias is born August 18

1966

Robert Hersh is born May 7

Mark Snow is born May 22

1967

Anthony Marconi is born November 23

1968

Lionel Fusco is born March 17

James “Rhodey” Rhodes is born October 6

1969

Bruce Banner is born December 18

1970

Tony Stark is born May 29

Emily Prentiss is born October 12

1971

Clint Barton is born June 18

Aaron Hotchner is born November 2

1972

Joycelyn Carter is born March 7

Haley Hotchner is born July 16

1973

Derek Morgan is born June 6

1974

Pepper Potts is born February 12

1975

John Reese (Harris) is born May 4

1977

Elle Greenaway is born June 24

Penelope Garcia is born July 7

1978

Sam Wilson is born September 23

1979

Dean Winchester is born January 24

1981

Samantha Groves is born September 4

Sean Hotchner is born August 7

Spencer Reid is born October 28

1982

Maria Hill is born April 4

1983

Grant Ward is born January 7

Sam Winchester is born May 2

Nathan Ingram leaves MIT with an unfinished degree to start IFT May 29

Michael Cole is born July 10

Sameen Shaw is born October 25

Mary Winchester dies November 2

1984

Jessica Moore is born January 24

Will Ingram Finch is born August 31

Natasha Romanov is born November 20

1985

Devon Grice is born November 30

1986

Alec Hardison is born April 13

Dum E is created June 18

1987

Tony graduates from MIT June 5

Leo Fitz is born August 19

Jemma Simmons is born September 11

1988

Skye (Daisy Johnson) is born July 2

1989

This is the last year that Millie Winchester was seen alive. This is because she abandons the name and steps fully into her Maria Stark alias.

Pietro & Wanda Maximoff are born January 1

1990

Adam Milligan is born September 29

1991

Maria and Howard Stark die December 16

1992

Theresa Whitaker is born March 7

John Winchester drops his sons off with his half brother Tony Stark April 20

July 20 Tony manages to gain custody of his nephews.

1993

John Winchester suffers a mental break and kills Kate Milligan and kidnaps his son on October 3

October 11 Adam is dropped of with Tony which causes a scandal

1995

Caleb Phipps is born July 26

1997

Taylor Carter is born June 18

1999

Masha Ingram-Finch is born February 24

2000

Lee Fusco is born January 9

2001

Peter Parker is born August 10

2003

Genrika Zhirova is born December 13

2004

Lionel and his wife divorce

2005

Jack Hotchner is born October 7

“The Machine” goes online February and the next day sold.

2007

On February 5 Tobias Hankel kidnaps Spencer Reid.

2008

Henry LaMontagne is born November 12

2009

Tony is kidnapped by 10 Rings February 13

2010

The Ferry bombing happens killing Nathan Ingram September 26

Sometime during October or November Rick Dillinger is hired by Finch

Dillinger dies December 5ish

2012

May 4; Battle of New York happens.

#inkstained rambles#marvel cinematic universe#person of interest#criminal minds#super crossover#the supernatural are mutants

11 notes

·

View notes