#6th-5th centuries BCE

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Etruscan Bronze Helmet in the Shape of a Wolf’s Head 6th-5th centuries BCE.

#Etruscan Bronze Helmet in the Shape of a Wolf’s Head#6th-5th centuries BCE#Wolf's Head Helmet#Head of a Boar#bronze#bronze helmet#bronze sculpture#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#etruscan history#etruscan art

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Limestone statues of Cypriot women

* Vouni

* 5th century BCE / 6th century BCE

* Medelhavsmuseet, Stockholm

Stockholm, November 2023

#Cyprus#Vouni#5th century BCE#6th century BCE#palace#temple#ancient#art#statue#limestone#clothing#jewelry#detail#Medelhavsmuseet#my photo

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

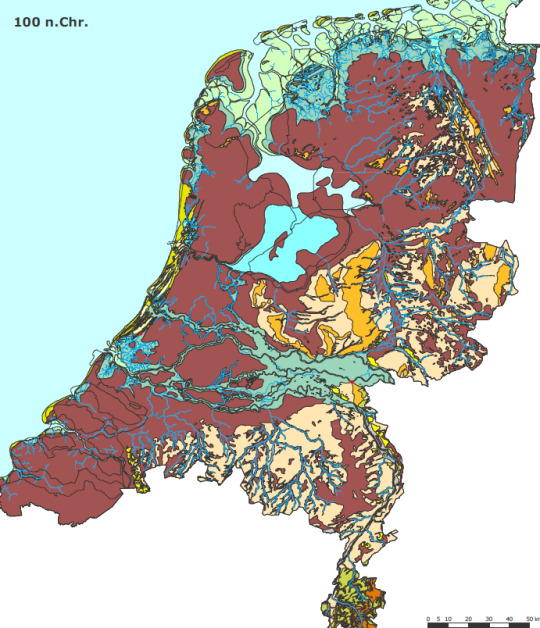

Frisia around the 6th century CE. Made by Fryske Akademy after Heidinga.

Landscape maps of the Netherlands in the Northern Iron Age show that Frisia was mainly a coastal landscape with wetlands (peatland, moor, bog, etc.) inland and only got wetter over time. 1) 500 BCE 2) 100 CE 3) 800 CE Made by Rijksdienst voor Cultureel Erfgoed.

Brown means peat-wetland. Yellow spots at the shores indicate dunes or ridges, the most inhabitable land, as the orange spots in the illustration at the top of this post also indicate.

#frisia#northern iron age#map#netherlands#wadden#zeeland#zuid-holland#noord-holland#north sea#friesland#groningen#utrecht#gelderland#6th century#5th century BCE#1st century#8th century#island#germany#denmark

1 note

·

View note

Text

phoenician glass pendant in the form of a demonic mask (6th-5th century BCE) // jinx the cat (21st century CE)

#tagamemnon#i cant stop looking up phoenician face beads#queueusque tandem abutere catilina patientia nostra

763 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earthenware rhyton in the shape of an ibex head, from Achaemenid Persia (6th or 5th century BCE). Excavated at Gilan, Iran; now in the Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, Japan.

#art#art history#artifact#artifacts#rhyton#Persia#Persian art#Persian Empire#Achaemenid Empire#earthenware#Tokyo National Museum

398 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Zagreus

In ancient Greek mythology, Zagreus is a god closely associated with the wine god Dionysus, the underworld, and hunting. A son of Zeus and Persephone, he is known in the Orphic tradition as the first incarnation of Dionysus, whilst other stories identify him as the son of Hades or even as Hades himself.

The earliest mention of Zagreus comes from a quoted line from the lost Greek epic Alcmeonis, a poem dating back to at least the 6th century BCE, where he is described alongside Gaia, the Greek personification of the earth, as "highest of all the gods" (West, 61). Yet some scholars believe this line was only in reference to him being the highest of all the gods of the underworld, as surviving fragments of works written by the Greek tragedy playwright Aeschylus (c. 525 to c. 456 BCE) identify him closely with Hades.

Zagreus is also the name often given to Orphic Dionysus, whose story was central to the beliefs of the followers of Orphism. In the story, Zagreus, a child of Zeus and Persephone, was killed and eaten by the Titans, except for his heart which was found by Athena and brought to Zeus. Because his heart was saved, Zagreus was able to be reincarnated as the god Dionysus. Zeus punished the Titans for their treachery by destroying them with a thunderbolt, and it was from their ashes that humanity was born.

Followers of Orphism, therefore, believed that humanity had a dual nature, one of the body, inherited from the Titans, and one of the soul, or the divine spark inherited from the parts of Zagreus ingested by the Titans. It was the central focus of Orphism for one to achieve salvation through acts of atonement during their lifetime or else be cursed with endless reincarnation. Aspects of Orphism, including the suffering, death, and resurrection of Dionysus Zagreus, and the idea of redemption for an original sin call to mind aspects of later religions, such as Christianity.

Origins & Interpretations

What little is known of Zagreus outside his association with Dionysus comes from fragments of lost works of Greek literature. He was certainly renowned, as a surviving quote from the lost Greek epic Alcmeonis offers a prayer to "Mistress Earth, and Zagreus highest of all the gods" (West, 61). The invocation of his name alongside Mother Earth seems to suggest that Zagreus was held in high esteem and was thought to be very powerful. Some scholars believe that the reference to him as "highest of all the gods" does not claim that he was the greatest god on Mount Olympus, but rather that he was the greatest god of the underworld.

This can be gathered from the context of the prayer, in which the hero of the Alcmeonis, Alcmaon, calls upon the powers of the earth to see the soul of his father safely transferred to heaven. Zagreus' status as a god of the underworld can further be attested to by two works written by Aeschylus. One of these references, found in a fragmented line of one of Aeschylus' lost Sisyphus plays dating back to around the 5th century BCE, identifies Zagreus as the son of Hades. Another reference, from Aeschylus' Egyptians names Zagreus as Hades himself.

Either way, Zagreus seems to have been a powerful underworld god, earning the epithet "Chthonios," or "the subterranean." As for the associations of him to Dionysus, scholars such as Timothy Gantz have postulated that the separate myths of Zagreus, a son of Hades and Persephone, had over time become merged with the myth of Orphic Dionysus, the son of Zeus and Persephone, so that the name Zagreus came to be associated with both myths.

Continue reading...

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amphoriskos (Container for Oil)

Eastern Mediterranean, possibly from Rhodes, late 6th-early 5th century BCE

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soldiers of the 123rd Separate Brigade, Ukrainian Territorial Defense Forces discovered an Ionian amphora and an ancient Greek wine-pouring jug while constructing fortifications in Mykolaiv Oblast, dating to 6th - 5th century BCE

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anatolian Religion goes International: The Cult of the Goddess Kybele in the Ancient World

Bronze statuette of Kybele on a cart drawn by lions, Roman, 2nd half of 2nd century CE. MET (ID: 97.22.24).

During the Hellenistic period, mystery cults became increasingly popular. Many people found little comfort in the traditional Greek pantheon and, as a result, turned to other belief systems and forms of worship to fulfill their spiritual needs. Philosophical schools like Stoicism and Epicureanism flourished, while new religious cults emerged, often offering consolation for earthly hardships by promising rewards in the afterlife. Many of these cults were centered around foreign deities, partly due to their exotic and mysterious allure. One famous example is the Egyptian goddess Isis, whose cult quickly spread throughout the Mediterranean. These new religious practices were especially popular in various Hellenistic colonies but also gained a following on the Greek mainland. In fact, as early as the 5th century BCE, foreign cults began to make their way into classical Athens. Among these exotic deities was Kybele.

Kybele, also known as Ma or the Great Mother, was an ancient goddess of Anatolian origin. She was initially known in the Hittite world as Kubaba and was of local significance only in the city of Karkemish. During the period of the Neo-Hittite kingdoms (12th–8th century BCE), Kybele—as she came to be known in the Phrygian language—rose in prominence within the Anatolian pantheon. From then on, she was worshipped as a mother goddess, offering aid to those in need. It was in Phrygia that Kybele also developed into a goddess of raw nature, regarded as a divine force capable of taming the wild beasts that roamed the Anatolian landscape. She was often associated with the mountains and caverns that dotted the region.

Cybele enthroned, with lion, cornucopia, and mural crown, Roman, c. 50 CE. Getty Museum

Her main center of worship was located in Pessinus, an ancient Phrygian trading hub on the high Anatolian plateau, situated along the Gallos River, a seasonal tributary of the Sakarya River. Her spirit was believed to dwell in a large black baetylus rock, which served as a sacred cult object. In 205/4 BCE, this stone was famously transported to Rome and placed in a sanctuary on the Palatine Hill after a prophecy declared that her assistance was crucial in the war against Hannibal.

As previously noted, Kybele became very popular in the Greek world. The oldest known temple dedicated to her in the Hellenic world is located on the island of Chios. The Daskalopetra monument, as it is called, was likely built sometime between the late 6th and early 5th centuries BCE. In the following decades, sanctuaries dedicated to Kybele appeared throughout the Greek world. These temples were even given a distinct name: Metroon.

One famous Metroon was in Athens, established next to the Boulè in the Agora. Its significance is evident from the fact that it was rebuilt after the Persians destroyed the original structure in 480 BCE. The Athenian Metroonalso served as a state archive, likely to invoke divine protection over the documents stored inside. Evidence suggests that the structure remained in use well into Late Antiquity. Other notable Metroa include one at Olympia and two in Asia Minor, at Kolophon and Smyrna, both of which were interestingly also used as state archives.

Excavated ruins of the Metroon in Athens.

Kybele was usually worshipped alongside her youthful consort, Attis. Attis is also a deity whose cult dates back to the Late Bronze Age. He originally was a local vegetation god associated with Pessinus. According to myth, Attis castrated himself, died, and resurrected. This was interpreted as a symbolic reference to the fruits of the earth, which die during winter and are reborn in spring. The story of Attis and Kybele was later popularized in literature through Catullus, who wrote a piece of 93 galliambic verses about Attis' self-mutilation.

Self-castration became a defining feature of the priests of Kybele. One could only be admitted to this priestly order after undergoing the harrowing ritual of self-castration. It was believed that sacrificing this body part granted the priests the power of prophecy. Another explanation for this self-mutilation was that it allowed the priests to maintain celibacy, enabling them to devote all their attention to Kybele. The priests of Kybele came to be known as Galli/Galloi, a term derived from the river Gallus, the earlier mentioned tributary of the Sakarya River, along which Pessinus was located. According to tradition, during a specific ritual, the priests drank from the stream, which inspired them with a frenzy.

In Rome, the Galli became an important college of priests, distinct from the other pontifices (priests) in that Roman citizens were completely excluded from this group. The Galli all came from Phrygia and were led by the so-called Archigallus. There were also Galloi in Asia Minor and Syria, known for traveling around and entertaining the masses with their ecstatic dances.

This ecstatic nature was also a key attribute of Kybele’s cult . She was often imagined as being accompanied by wild music and wine, followed by an entourage of men and women who had lost all self-control. This frenzy frequently led to acts of self-mutilation, an apparent reference to Attis. One theory suggests that this 'wild' aspect of Kybele’s cult originates from her association with the Cretan deity Rhea, whose worship also featured raucous, ecstatic rituals. The trance experienced by Kybele’s adherents was likely intended as a form of self-purification.

Cybele in a chariot driven by Nike and drawn by lions toward a votive sacrifice (right); above are heavenly symbols including a solar deity, Plaque from Ai Khanoum, Bactria (Afghanistan), 2nd century BCE

In literature, art, and other sources, Kybele is often depicted riding a chariot pulled by lions. One such famous representation can be admired at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The piece dates to the second half of the 2nd century CE. In this sculpture, the lions appear to have spouts emerging from their mouths, suggesting that the bronze work may have once been part of a fountain. Other theories propose that these spouts were designed to release steam or pour out other liquids instead of just water. Regardless of its original function, the piece is a remarkable example of the high quality of ancient Roman bronze sculpture and simultaneously highlights the popularity of Kybele’s cult in the ancient world, as the bronze is one of the countless artistic representations of the goddess dating back to antiquity.

Olivier Goossens

Read more:

-Roller, L., In Search of God the Mother: The Cult of Anatolian Cybele, 1999.

-Merrill, E., Catullus, 1893.

- Beard, M., "The Roman and the foreign: the cult of the "great mother" in imperial Rome", Shamanism, history, and the state, eds. N. Thomas & C. Hymphrey, 1994, pp. 164–190.

- Roscoe, W., "Priests of the Goddess: Gender Transgression in Ancient Religion", History of Religions, Vol. 35, 1969, pp. 195–230.

-Lane, E. (ed.), Cybele, Attis, and Related Cults: Essays in Memory of M.J. Vermaseren, 1996.

- Alvar, J., Romanising Oriental Gods: Myth, Salvation and Ethics in the Cults of Cybele, Isis and Mithras, 2008.

#roman#roman art#greek#greek art#ancient rome#roman empire#ancient greece#archeology#ancient religion#ancient art#hellenism#hellenistic world#hellenistic culture#anatolia#ancient anatolia#ancient archeology

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient bull figurine

* Cyprus

* 5th century BCE / 6th century BCE

* Medelhavsmuseet, Stockholm

Stockholm, November 2023

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bronze sheet in the form of an owl, Greek, 6th - 5th Century BCE

From the Acropolis Museum

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bead ornaments in the form of female head. 6th–5th century BCE. Credit line: Purchase, 1898 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/246811

#aesthetic#art#abstract art#art museum#art history#The Metropolitan Museum of Art#museum#museum photography#museum aesthetic#dark academia

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

i am a bit stunned by the amount of misinformation going around? and people are now accusing Eve of replacing Lilith in the later transcriptions… ?

let me try to share some of my knowledge? English is not my first language so this might not come across well?

the first ‘bible’ to speak of Adam was the Tanakh. specifically, he appears in the Book of Genesis, which is part of the Torah, the first section of the Tanakh. Genesis describes Adam as the first human, created by God. the story of Adam in Genesis is believed to be dated back to ancient Israelite oral traditions, around the 6th to 5th century BCE during or after the Babylonian Exile. this makes the Tanakh the first surviving document to tell the story of Adam and introduce him as the first human.

the Tanakh is made up of sacred Jewish texts written primarily in Hebrew, and it forms the canonical scriptures of Judaism. the easiest way explain the Tanakh is to think of it as being similar to what Christians refer to as the Old Testament…

Eve is the only named wife of Adam in the Tanakh. She is introduced in the Book of Genesis as Adam's companion, created by God from one of Adam's ribs (Genesis 2:18-25).

Eve is described as the "mother of all living" (Genesis 3:20) and is central to the story of the Garden of Eden and the "Fall" narrative.

Lilith is not mentioned in the Tanakh. her story comes later in the Alphabet of Ben Sira, written sometime between the 8th and 10th centuries CE. the Talmud and earlier Jewish texts mention Lilith as a demon or night spirit, but she has no connection to Adam and isn’t considered to be human at all.

the idea of Lilith as Adam's first wife became prominent in medieval Jewish mysticism and later folklore, but she doesn’t appear in the canonical Tanakh texts themselves.

the Tanakh is ancient scripture, the Alphabet of Ben Sira is a later work that reflects medieval folklore and ideas that expanded on and reinterpreted some biblical themes and figures. Lilith being Adam’s first wife is not considered biblical accurate and can be considered insulting suggesting otherwise ??? (from past experience!!! )

…sooooo Lilith actually replaced Eve and not the other way around.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scythian Warrior. Sibioara, Romania.

6th to 5th Century BCE.

#culture#art#history#ancient culture#ancient art#ancient history#scythia#Scythians#archeology#Romania#sibioara

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sike

Initial info snippet: Βεργίνα (or Vergina in English) is pronounced ver - YEE - nah. Just saying, for no particular reason whatsoever.

Perhaps you know that there is a country in the periphery of Greece that has a flag with a sun. This alongside other issues has been a cause of contention between Greece and this country, as it using this sun as a symbol of its non-Greek nationality was condemned by Greece as an act of cultural appropriation.

That sun looked suspiciously like (as in, it was identical down to the last line) to the Vergina Sun, or sometimes called Vergina Star, most famously discovered in the tomb of King Philip || of Macedon, in Ancient Aegae, Vergina, Macedonia, Greece.

The golden larnax with the Vergina Sun found in the tomb that is believed to be King Philip's.

For some time the Vergina Sun was mostly perceived as a symbol of Macedonia or Macedonian royalty, except that meant polar opposite things to Greeks versus to their neighbours. The Vergina Sun became the symbol of the administrative and historical region of Macedonia within the Greek state, which has this local flag:

The flag was first created in the late 80s after archaeologist Michael Andronikos made the huge discovery of the tombs in Vergina. The Vergina Sun was added as a national symbol at the Hellenic Parliament in 1993.

Meanwhile, in 1992 the newly founded neighbour state (risen through the collapse of Yugoslavia) adopted the EXACT same flag as their official national flag, except the background was changed to red. Greece condemned the use of this symbol, accusing the country of appropriation. Due to the rising tensions between the states, the neighbouring country eventually changed its flag.............. which means it's still the same red flag with the sun except now the sun is "designed differently". Of course, the implications behind it as well as the claims have not changed one bit. The neighbour country was mad at Greece for preventing them to express their true ethnicity and for using her immense evil power (which, as we all know, Greece definitely possesses) to steal THEIR history, because Greece is jealous of THEIR history. Anyway even though there was a legal agreement of sorts between the countries in the last years, it is honoured so little you might as well believe it was never done. And it is crap for our side as well, so everybody hates it.

But here's the funny thing. Even if one argues the true issue is what being a Macedonian entails (which shouldn't truly be a discourse but let's pretend it is)... the hilarious truth is that the Vergina Sun..... is actually not a symbol of Macedonia and Macedonians.

You see, the symbol has been discovered all throughout Greece since at least the 6th century BCE, way before the Kingdom of Macedon rose to any prominence.

Vergina Sun originating from… Sparta, 6th century BC, exhibited in the Louvre.

This famous amphora by Exekias, 6th century BC, depicting Achilleus and Ajax playing a board game. The Vergina Sun decorates their cloaks. Exhibit in the Vatican Museum.

Hercules fighting the Amazons. The Amazon bears a shield with the Vergina Sun. Early 5th century, Gela, Italy. (So it was crafted in the Greek colonies in Magna Grecia, South Italy.) Exhibited in the Regional Archaeological Museum "Antonio Salinas", Palermo.

Jar with the Judgement of Paris. Athena's shield is decorated with a Vergina Sun. Athens, c. 360 BC.

So you know, not only it wasn't an exclusively Macedonian symbol but it actually seems to have been an Archaic symbol of Panhellenic (encompassing all the Greeks) warfare.

Dem evil Griekos stealing other pipl's history.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

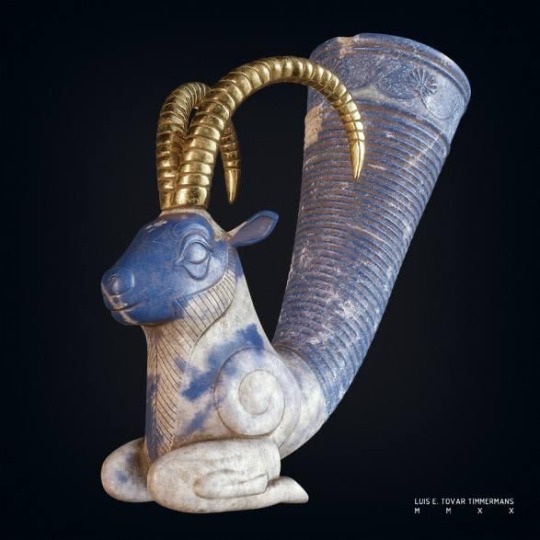

In the heart of the ancient Achaemenid Empire, a masterpiece of Persian artistry emerges—a rhyton (drinking horn or in the shape of a horn) carved from the deep blue lapis lazuli and adorned with gold, taking the form of a majestic ibex (mountain goat).

Dating back to the 6th to 5th century BCE, this exquisite ceremonial vessel not only exemplifies the sophisticated craftsmanship and rich symbolism of the time but also provides a fascinating glimpse into the cultural and economic prowess of ancient Persia.

[Description and Material]:

*Material:

Lapis lazuli, a semi-precious stone prized for its deep blue color, was highly valued in ancient Persia and sourced primarily from what is now Afghanistan.

*Form:

The rhyton is shaped like an ibex, a type of wild goat with prominent, curved horns, reflecting the importance of nature and animal motifs in Persian art.

[Use]:

*Function:

A rhyton is a type of vessel typically used for drinking or pouring liquids, especially in ceremonial contexts. The liquid would be poured from the top and flow out through the spout, which could be the mouth of the animal in this case.

*Ceremonial Role:

Rhytons were often used in religious and royal ceremonies. The choice of lapis lazuli and the intricate craftsmanship suggest that this particular rhyton was likely used by the elite, possibly in rituals associated with the Zoroastrian religion or royal banquets.

[Cultural and Historical Significance]:

*Art and Symbolism: The ibex design reflects the importance of wildlife in Persian culture and the symbolic use of animals in conveying power and divinity. The ibex, with its strong and agile form, could symbolize qualities such as strength and resilience.

*Trade and Wealth: The use of lapis lazuli indicates extensive trade networks and the wealth of the Achaemenid Empire, as this material was not locally sourced and had to be imported.

*Royal Patronage: The Achaemenid rulers were great patrons of the arts, and such luxurious items underscore their desire to display their wealth, power, and cultural sophistication.

[Academic Perspective on Material Culture]:

*Cultural Synthesis:

Scholars often view Achaemenid art, including rhytons, as a synthesis of various cultural influences, including Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Greek, reflecting the diverse and cosmopolitan nature of the empire.

*Representation of Power:

Academics see these artifacts as representations of royal propaganda, showcasing the divine right and grandeur of the Persian kings.

*Symbol of Status:

In material culture studies, such high-quality items are considered symbols of social status and wealth. They provide insights into the social hierarchy and economic conditions of the time.

*Artistic Techniques:

The craftsmanship of the rhyton is analyzed for its artistic techniques, such as carving and polishing lapis lazuli, which indicate advanced skills and aesthetic values.

[Notable Examples]:

Museums and Collections: Notable examples of such rhytons can be found in major museum collections, such as the British Museum and the Louvre, where they are studied and displayed as prime examples of Achaemenid artistry and craftsmanship.

In conclusion, the lapis lazuli rhyton in the shape of an ibex from the Achaemenid period is a significant artifact that illustrates the artistic, cultural, and economic aspects of ancient Persia. It serves as a key piece of material culture, providing valuable insights into the ceremonial practices, trade networks, and socio-political dynamics of the Achaemenid Empire.

#ancient Persia#Zoroastrianism#ceremonial vessel#rhyton#lapis lazuli#Iran#Mesopotamia#Ancient history#Near East#ancient civilisations#ancient art#ancient craft#archaeology#Achaemenid#Achaemenid Culture

76 notes

·

View notes