#38/41-103CE

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

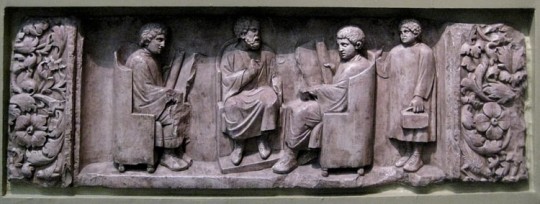

Roman Education

Roman education had its first 'primary schools' in the 3rd century BCE, but they were not compulsory and depended entirely on tuition fees. There were no official schools in Rome, nor were there buildings used specifically for the purpose. Wealthy families employed private tutors to teach their children at home, while less well-off children were taught in groups.

Schools

Teaching conditions for teachers could differ greatly. A tutor who taught in a wealthy family did so in comfort and with facilities; some of these tutors could have been brought to Rome as slaves having been captured during war times, and they may have been highly educated. Other teachers, employed by the less well-off rented a room to hold classes or set up a school in the extended area of a shop, which the Roman historian, Suetonius (69 to c. 130/140 CE) refers to as a pergula (Gram.18.1). It was not uncommon for poorer teachers to hold classes for their students in outdoor public places – the trivium – the corner of the street, or in the piazzas. Classes began at dawn and continued until noon. The Roman poet, Martial (38/41-103 CE), complained about being woken at dawn by the booming voice of a teacher and his outdoor class: "Before the crested rooster has crowed you shatter the silence with your harsh words..." (Ep. 9.68).

Schools were privately operated by teachers and therefore dependent on tuition fees. Teachers were of relatively low status, and throughout antiquity, the profession was seen as a humble one. Schoolteaching was seen as a trade, in the servile commercial sense, and it paid poorly.

Parents paid the school fees in instalments at the end of each term, however, this was not a certainty; they did not always pay due to not having the money to do so, or because they were unhappy with the progress of their child, and as a result, teachers often found themselves in difficult financial positions. In the education hierarchy, the litterator (primary teacher), who required no special qualifications, was on the lowest level of income. In 301 CE, the salary for a primary teacher was 50 denarii a month per pupil; a bushel (c. 35 l) of wheat was 30 denarii. The grammaticus, a more prestigious position as an advanced educator is recorded in 301 CE as receiving a salary of 200 denarii per pupil per month. The rhetor, the teacher of rhetoric, required greater skills and expertise, and as a result, there were opportunities for achieving a good salary.

Continue reading...

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roman Education

Roman education had its first 'primary schools' in the 3rd century BCE, but they were not compulsory and depended entirely on tuition fees. There were no official schools in Rome, nor were there buildings used specifically for the purpose. Wealthy families employed private tutors to teach their children at home, while less well-off children were taught in groups.

Schools

Teaching conditions for teachers could differ greatly. A tutor who taught in a wealthy family did so in comfort and with facilities; some of these tutors could have been brought to Rome as slaves having been captured during war times, and they may have been highly educated. Other teachers, employed by the less well-off rented a room to hold classes or set up a school in the extended area of a shop, which the Roman historian, Suetonius (69 to c. 130/140 CE) refers to as a pergula (Gram.18.1). It was not uncommon for poorer teachers to hold classes for their students in outdoor public places – the trivium – the corner of the street, or in the piazzas. Classes began at dawn and continued until noon. The Roman poet, Martial (38/41-103 CE), complained about being woken at dawn by the booming voice of a teacher and his outdoor class: "Before the crested rooster has crowed you shatter the silence with your harsh words..." (Ep. 9.68).

Schools were privately operated by teachers and therefore dependent on tuition fees. Teachers were of relatively low status, and throughout antiquity, the profession was seen as a humble one. Schoolteaching was seen as a trade, in the servile commercial sense, and it paid poorly.

Parents paid the school fees in instalments at the end of each term, however, this was not a certainty; they did not always pay due to not having the money to do so, or because they were unhappy with the progress of their child, and as a result, teachers often found themselves in difficult financial positions. In the education hierarchy, the litterator (primary teacher), who required no special qualifications, was on the lowest level of income. In 301 CE, the salary for a primary teacher was 50 denarii a month per pupil; a bushel (c. 35 l) of wheat was 30 denarii. The grammaticus, a more prestigious position as an advanced educator is recorded in 301 CE as receiving a salary of 200 denarii per pupil per month. The rhetor, the teacher of rhetoric, required greater skills and expertise, and as a result, there were opportunities for achieving a good salary.

Continue reading...

37 notes

·

View notes