#1987 MLB All Star Game

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

NBC Sports: MLB 1987-All Star Game-National League @ American League: Full Game

.Source:The New Democrat What I remember about this game is not much. I remember the Oakland Coliseum when it was beautiful and essentially a classic ballpark, with the Raiders moving to Los Angeles. I remember the rebirth of the Oakland Athletics to a certain extent, with them hiring manager Tony La Russa and Jose Canseco, Mark McGwire and Carny Lansford already being on the club before Canseco…

View On WordPress

#1987 MLB All Star Game#1987 MLB Season#Joe Garagiola#Major League Baseball#MLB Game of The Week#NBC Sports#Oakland Coliseum#Vin Scully

0 notes

Text

Joe West

Physique: Husky Build Height: 6′1″

Joseph Henry West (born October 31, 1952), nicknamed "Cowboy Joe" or "Country Joe", is an American former baseball umpire. He worked in Major League Baseball (MLB) from 1976 to 2021, umpiring an MLB-record 43 seasons and 5,460 games. He served as crew chief for the 2005 World Series and officiated in the 2009 World Baseball Classic. On May 25, 2021, West broke Bill Klem's all-time record by umpiring his 5,376th game.

He’s the most polarizing man on the Hall of Fame ballot. Fans have been screaming at him for 44 years, managers and players cursing him, and he has a personality bigger than virtually every player who steps onto the field. All I have to say about this this guy is… DAT ASS.

Born in Asheville, North Carolina, he grew up in Greenville and played football at East Carolina University (ECU) and Elon College. West entered the National League (NL) as an umpire in 1976; he joined the NL staff full-time in 1978.

West has been married twice. After the death of his first wife, West remarried.

Career Highlights and Awards Special Assignments All-Star Game (1987, 2005, 2017) Wild Card Game (2013, 2014, 2020, 2021) Division Series (1995, 2002, 2005, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2012, 2016) League Championship Series (1981, 1986, 1988, 1993, 1996, 2003, 2004, 2013, 2014, 2018) World Series (1992, 1997, 2005, 2009, 2012, 2016) World Baseball Classic (2009) MLB record 43 seasons umpired MLB record 5,460 games umpired

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mark Osborne and Angeline Jane Bernabe at ABC News:

Pete Rose, Major League Baseball’s hit king who then became a pariah for gambling on the game, has died at the age of 83, the medical examiner in Clark County, Nevada, confirmed to ABC News on Monday. Rose was found at his home by a family member, according to the medical examiner. There were no signs of foul play. The coroner will investigate to determine cause and manner of death. The medical examiner told ABC News that Rose was not under the care of a doctor when he died, and the scene is being examined. The coroner will investigate to determine the cause and manner of death. ABC News has reached out to Rose's rep.

Rose brought a workmanlike attitude to America's pastime and won innumerable fans for his hustle on the field. By the end of his 24-year career, 19 of which were with the Cincinnati Reds, he held the record for most career hits, as well as games played, plate appearances and at-bats. He was also a 17-time All-Star, the 1973 NL MVP and 1963 Rookie of the Year. He also won three World Series -- two with Cincinnati's "Big Red Machine" clubs in 1975 and 1976, and a third with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1980. But Rose will always be remembered as much for being banned for life from MLB in 1989 over gambling on games while he was managing the Reds. With Rose under suspicion, new MLB Commissioner Bart Giamatti commissioned an investigation led by John Dowd, a lawyer with the Department of Justice, in April 1989. By June, the damning report was released, documenting at least 52 bets on Reds games in 1987, his first season as solely a manager after serving as player/manager for three seasons. The bets totaled thousands of dollars per day, according to the Dowd Report.

MLB legend and all-times hits leader Pete Rose died at 83. Rose was banned from the league over gambling on games while as Reds manager.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

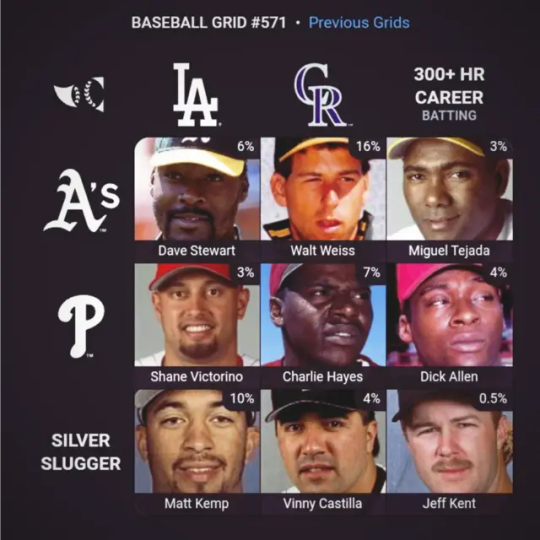

Happy World Series Friday!!! Here is my MLB Immaculate Grid number 571 for Thursday October 24, 2024.

If I'm not mistaken, aside from Charlie Hayes, this grid has a number of players that I haven't used in a grid. BTW, I wish there was a way to keep track of that. But I digress.

Dave Stewart was one of the most intimidating pitchers daring the late 1980s and early 1990s. Stewart out together four straight 20+ win seasons from 1987 - 1990 for the Oakland A's. In 1988, Stewart led the AL with 37 starts of which he completed 14. He would repeat as league leader in starts and complete games in 1990 with 36 starts and 11 CG with 4 shutouts. During that stretch, he averaged 265 innings oitcher per season with a league best 275.2 in 1988 and 267 in 1990. Stewart put up numbers that a vast majority of starters today can't even imagine reaching.

How is Jeff Kent not in the Hall of Fame. The guy has 2461 hits and 377 homers as a second baseman. That's good for 13th all time in hits amd number one in homers for a second baseman. He was a four time All-Star, four time Silver Slugger and top three in MVP voting winning the 2000 NL MVP while playing on the same team as Barry Bonds. If he was an outfielder then I can see it. But as a second baseman? He deserves another look by a Veterans committee for the Hall.

Well that's all for now folks. Who ya got in game 1!!! Yanquis or Doyers. Let me know. On to grid number 572.

#MLB Immaculate Grid#Immaculate Grid#Baseball Trivia#Baseball History#Historia Del Beisbol#Yakyū No Rekishi#Baseball#Beisbol#Pro Yakyu#BaseballSisco

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Minnesota Twins are an American professional baseball team based in Minneapolis. The Twins compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) Central Division. The team is named after the Twin Cities moniker for the two adjacent cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul. The franchise was founded in Washington, D.C., in 1901 as the Washington Senators. The team moved to Minnesota and was renamed the Minnesota Twins for the start of the 1961 season. The Twins played in Metropolitan Stadium from 1961 to 1981 and in the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome from 1982 to 2009. The team has played at Target Field since 2010. The franchise won the World Series in 1924 as the Senators, and in 1987 and 1991 as the Twins. From 1901 to 2023, the Senators/Twins franchise's overall regular-season win–loss–tie record is 9,177–9,875–109 (.482); as the Twins (through 2023), it is 4,954–5,011–8 (.497).

...

Yeah, we're cooked.

Lead is fully gone now, and with 9 games left we have to outpace the Tigers, who are on fire and get basically three free wins to end the season. Over the last 4.5 weeks, we have exactly matched our pace from the infamous September 2022 collapse (11-22 to end the season in '22, 10-20 so far now). The remarkable and gutwrenching part about this is it comes literally immediately after the high-water mark of the season, 17 games over .500 after game 3 against the Rangers.

Turns out losing 2/5 of the starting rotation for the season and 2/3 of the star position player core for long stretches, then relying on a rotation, lineup, and bullpen largely inexperienced with this type of constant high leverage games and all running on fumes, that wasn't a great recipe for success. At the same time, the variety of ways the Twins have found to lose over this stretch almost defies explanation. Everything needs to go right in order to win, and that never happens. They're just playing that bad.

As recently as 9/2, after we won the first game of the Rays series, Fangraphs had us at a season-high 95.8% chance to make the playoffs. On 9/12, a week ago, after taking the Angels series, it was 90.8%. It's now 62.6%, the lowest it's been in over three months, and even that feels high with how this team (and Detroit) has been playing. We're managing the statistical equivalent of rolling a natural 1.

I fucking hate the Guardians. We play them twice as often as the Yankees, they are our direct playoff competition, we always lose in the same fucking way, and they definitely hate us back.

The pitching was fine in this series. Great even, 13 runs over 4 games is respectable and solidly above average. Starters and middle relief did their job. The only blips were Jax game 1 (there's been a lot of discussion over the psychological effect of getting out of the 7th and having to go back out for the 8th) and Henriquez game 3 (thrown in way over his head because all our leverage guys were down).

The problem, as it's often been, was the offense. Just unable to add on, answer back, push runners across, extend rallies, or literally anything to give our pitching staff breathing room. It's a problem over this stretch, and it's a problem every time we play this team. Each game had one or two guys who could get something going (Buxton, Wallner, Castro, Correa, Margot), but the rest of the lineup fell flat. It's reminiscent of last year's May-June malaise, where bullpen losses showed up on the scorecards but the real problem was endless missed opportunities on offense.

Eesh. I don't know. I like how the team's shaping up for next year, and there's still plenty of mathematical paths for them to make it this year, but it's looking bad and has for a bit now.

I think I'll be an NL supporter for the playoffs this year.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bo Jackson: The Ultimate Two-Sport Legend

Bo Jackson is one of the most remarkable athletes in sports history. Known for his extraordinary abilities in both professional baseball and football, Jackson is the only athlete to be named an All-Star in two major American sports leagues. His combination of power, speed, and agility made him a legend and an icon of the 1980s and early 1990s, leaving an indelible mark on both the NFL and MLB.

Early Life and College Stardom

Born on November 30, 1962, in Bessemer, Alabama, Jackson grew up in a large family and displayed his athletic talents from an early age. He excelled in multiple sports, including baseball, football, and track. After high school, he attended Auburn University, where he became a dominant force in college football. In 1985, Jackson won the Heisman Trophy, the most prestigious individual award in college football, solidifying his status as one of the nation’s top athletes.

At Auburn, Jackson also played baseball and ran track, showcasing his ability to dominate in multiple sports. His combination of speed and strength on the football field earned him a spot as one of the greatest college football players of all time.

The Dual-Sport Pro Career

Jackson’s dual-sport professional career began with a twist. He was initially drafted by the Tampa Bay Buccaneers as the first overall pick in the 1986 NFL Draft. However, due to issues related to his college eligibility and mistrust of the Buccaneers’ ownership, Jackson chose not to sign with them. Instead, he decided to pursue a career in Major League Baseball (MLB).

Jackson made his MLB debut with the Kansas City Royals in 1986. His raw power and speed on the field were immediately evident, and he quickly became one of the most exciting players in the game. In 1989, he was named an All-Star and even earned All-Star Game MVP honors after hitting a towering home run and showcasing his exceptional athleticism.

In the meantime, Jackson found his way to the NFL. After being drafted by the Los Angeles Raiders in the 7th round of the 1987 draft, he negotiated a unique contract that allowed him to play football after the conclusion of the MLB season. This rare arrangement led to one of the most captivating two-sport careers in history. Jackson’s football prowess was on full display as he regularly broke off long touchdown runs, including his famous 91-yard touchdown run on Monday Night Football against the Seattle Seahawks, a moment that cemented his legacy in the NFL.

The “Bo Knows” Era

In the late 1980s, Jackson’s fame transcended sports. He became the face of Nike’s “Bo Knows” advertising campaign, which celebrated his ability to excel in both baseball and football. The campaign featured commercials where Jackson tried his hand at other sports like basketball, tennis, and hockey, humorously suggesting that there was nothing Bo couldn’t do. This marketing campaign was wildly successful and helped make Jackson a pop culture icon.

Career-Ending Injury

Unfortunately, Jackson’s remarkable career was cut short by a devastating injury. In a 1991 NFL playoff game, he suffered a dislocated hip while being tackled during a run. The injury was severe, and complications from the dislocation led to avascular necrosis, a condition that deteriorated the bone and cartilage in his hip. This injury forced Jackson to retire from football, but he made a valiant return to baseball in 1993 with the Chicago White Sox, playing for two more seasons before retiring from professional sports in 1994.

Legacy and Impact

Even though his professional career was shortened, Jackson’s impact on sports and popular culture is undeniable. His ability to play both baseball and football at such a high level was unprecedented, and his feats on the field continue to be the stuff of legend. His highlights are still frequently replayed, and he remains a symbol of athletic greatness.

Bo Jackson’s story is one of natural talent, perseverance, and a relentless drive to succeed. He is widely considered one of the greatest athletes of all time, not just for his performances in football and baseball, but also for his legacy of pushing the limits of what an athlete can achieve.

0 notes

Text

Cleveland Municipal Stadium

Erieview Dr.

Cleveland, OH

Cleveland Stadium, commonly known as Municipal Stadium, Lakefront Stadium or Cleveland Municipal Stadium, was a multi-purpose stadium located in Cleveland, Ohio. It was one of the early multi-purpose stadiums, built to accommodate both baseball and football. The impetus for Cleveland Stadium came from city manager William R. Hopkins, Cleveland Indians' president Ernest Barnard, real estate magnate and future Indians' president Alva Bradley, and the Van Sweringen brothers, who thought that the attraction of a stadium would benefit area commerce in general and their own commercial interests in downtown Cleveland in particular. In November 1928, Cleveland voters passed by 112,448 to 76,975, a 59% passage rate, with 55% needed to pass, a US$2.5 million levy for a fireproof stadium on the Lakefront. Actual construction costs overran that amount by $500,00

Built in 1931 during the administrations of city managers William R. Hopkins and Daniel E. Morgan, it Cleveland Stadium was designed by the architectural firms of Walker and Weeks and by Osborn Engineering Company. It featured an early use of structural aluminum. The stadium was dedicated on July 1, 1931. On July 3, 1931, it hosted a boxing match for the National Boxing Association World Heavyweight Championship between Max Schmeling and Young Stribling, with 37,000 fans in attendance. The stadium was built for football as well as for the Cleveland Indians, who played their first game there on July 31, 1932. The stadium opened in 1931 and is best known as the long-time home of the Cleveland Indians of Major League Baseball (MLB), from 1932 to 1993 (including 1932–1946 when games were split between League Park and Cleveland Stadium), and the Cleveland Browns of the National Football League (NFL), from 1946 to 1995, in addition to hosting other teams, other sports, and concerts. The stadium was a four-time host of the Major League Baseball All-Star Game, one of the host venues of the 1948 and 1954 World Series, and the site of the original Dawg Pound, Red Right 88, and The Drive.

Through most of its tenure as a baseball facility, the stadium was the largest in Major League Baseball by seating capacity, seating over 78,000 initially and over 74,000 in its final years. For football, the stadium seated approximately 80,000 people, ranking as one of the larger seating capacities in the NFL. Former Browns owner Art Modell took over control of the stadium from the city in the 1970s and while his organization made improvements to the facility, it continued to decline. The stadium was added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 13, 1987. The Indians played their final game at the stadium in October 1993 and moved to Jacobs Field the following season. Although plans were announced to renovate the stadium for use by the Browns, in 1995 Modell announced his intentions to move the team to Baltimore citing the state of Cleveland Stadium as a major factor. The Browns played their final game at the stadium in December 1995, after which they were renamed the Baltimore Ravens.

As part of an agreement between Modell, the city of Cleveland, and the NFL, the Browns were officially deactivated for three seasons and the city was required to construct a new stadium on the Cleveland Stadium site. Cleveland Stadium was demolished beginning from November 1996 to completion in early March 1997 to make way for Cleveland Browns Stadium, which opened in 1999. Much of the debris, 15,000 short tons, from the demolition was placed in Lake Erie to create three artificial reefs for fishermen and divers, offshore of Cleveland and neighboring Lakewood. Construction on the new stadium began later in 1997 and it opened in August 1999 as Cleveland Browns Stadium. Modell had agreed to leave the Browns' name, colors, and history in Cleveland, and the NFL agreed to have a resurrected Browns team by 1999, either by relocation or expansion.

0 notes

Text

Know About MLB Pitcher John Smoltz Wife Kathryn Darden Who Is A Philanthropist

John Andrew Smoltz also professionally known by the name John Smoltz is an American former baseball pitcher. Also popular by the nickname Smoltzie and Marmaduke, John Smoltz played 22 seasons in Major League Baseball from 1988 to 2008. The 55-year-old, John Smoltz also served as a color analyst alongside Joe Simpson for the Atlanta Braves games on Peachtree TV. Furthermore, John Smoltz became the 574th overall picked player by the Detroit Tigers in the 1985 Amateur Draft. Smoltz initially played for the Class A Lakeland Tiger in the minor-league team and later moved on to the Class AA Glens Falls Tigers in 1987. Moreover, he made his MLB debut in 1988 for the Atlanta Braves. In this article, we will be talking about John Smoltz’s wife Kathryn Darden.

The Warren, Michigan-born, John Smoltz played most of the time for the Atlanta Braves. He played for the Braves from 1988 to 1999. Later, he again joined them in 2001 and ended his years at the Braves in 2008. In his final season, he played for the Boston Red Sox and St. Louis Cardinals. During his playing career, he won the 1995 World Sjoheries Champion with the Atlanta Braves. Likewise, he also appeared for the All-Star team eight times. He also holds the record for career strikeouts and the record for the most career game pitched for the Braves. After retiring from his playing career, he started his career as a color commentator and analyst for both Fox Sports and MLB Network. Likewise, he also provided color commentary during baseball’s biggest events like All-Star Game and World Series. In 2015, John Smoltz was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Without further delay, here are some interesting facts about John Smoltz wife Kathryn Darden.

Read more

0 notes

Photo

Cheryl D. Miller (born January 3, 1964) is a former basketball player. She was a sideline reporter for NBA games on TNT Sports and works for NBA TV as a reporter and analyst, having worked as a sportscaster for ABC Sports, TBS Sports, and ESPN. She was the head coach and general manager of the Phoenix Mercury. She was enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. She was inducted into the inaugural class of the Women's Basketball Hall of Fame. She was inducted into the FIBA Hall of Fame for her success in international play. She is the sister of retired NBA star and fellow Hall of Famer Reggie Miller and MLB catcher Darrell Miller. She played at Riverside Polytechnic High School where she was a four-year letter winner and led her team to a 132–4 record. She was awarded the Dial Award for the national high-school scholar-athlete of the year. She was the first player, male or female, to be named an All-American by Parade magazine four times. Averaging 32.8 points and 15.0 rebounds a game, she was Street & Smith's National High School Player of the Year. In her senior year, she scored 105 points. She set California state records for points scored in a single season (1156), and points scored in a high school career (3405). She served as a sideline reporter for the NBA on Thursday night doubleheader coverage. She joined Turner Sports as an analyst and reporter for the NBA. She did make occasional appearances as Studio Analyst for the NBA games. She became the first female analyst to call a nationally televised NBA game. She served as the sideline reporter in 2K Sports' NBA 2K Series. She worked as a Basketball Commentator at the 1994 Goodwill Games. She worked as a basketball reporter and called weightlifting for the 2001 Goodwill Games. She served as a women's basketball analyst and men's basketball reporter for coverage of the 1996 Olympics. She served as a reporter for the Wide World of Sports and a commentator for college basketball telecasts. She served as Field Reporter for the 1987 Little League World Series and served as a Correspondent for the 1988 Calgary Olympics. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence https://www.instagram.com/p/Cm9CxfCLkku/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

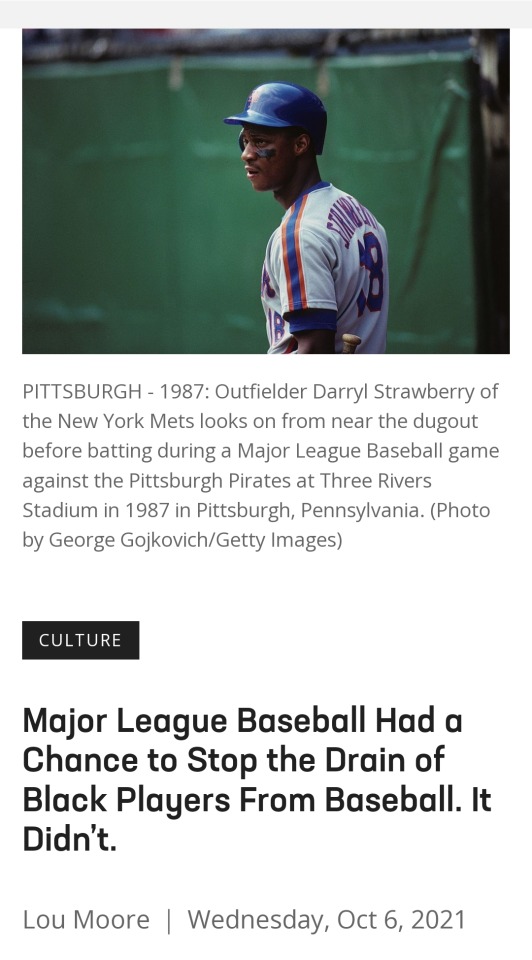

Text

Baseball was warned. In a 1974 article about the lack of Black MLB managers, the Sporting News pointed to an equally pressing concern: the decline of the Black player. Editor C.C. Johnson Spink wrote that over the previous five years, there had been a significant drop in the numbers of African-American players drafted, from 40 percent to roughly 15 percent. Spink also wrote that, statistically, Black players had outperformed their White counterparts.

If Black players left baseball, he concluded, then the game would suffer.

Three years later, Atlanta Braves general manager Bill Lucas, the league’s first Black GM and also the highest ranking Black official in MLB at the time, sounded a similar alarm, telling a reporter, “I’ve noticed a decline of Black ball players drafted and being funneled into the minor leagues and a decline in the number pursuing the major leagues. It’s an indication we may be losing some good athletes to other spring sports.”

Lucas wasn’t alone. The popular Black sportswriter Doc Young wrote numerous editorials about the decline of the Black superstar. Investigative pieces in newspapers across the country highlighted the general decline of Black American players. MLB officials publicly stated there was a problem. Monte Irvin, who integrated the New York Giants in 1949 and was at that time working in the commissioner’s office, said, “Black kids are not just playing as much baseball as they used to.” His solution? Get the kids when they were young. As he put it, “in the inner cities, a kid may have baseball ability right after he gets out of grade school but doesn’t know what to do with it. We have to get scouts to dig him out, to tell him where to play.”

The numbers told the story: From 1947, the year Jackie Robinson broke into the major leagues, to 1973, the number of Black players in MLB increased. But from 1973 to 1976, Black participation dropped from 144 to 109 players, or from 24 percent to 18.2 percent of the league.

Still, Lucas seemed largely unfazed. “I don’t think it’s serious, though,” he said. “The Black ballplayer’s not becoming extinct, or anything like that.” MLB lacked urgency, too. Perhaps the sport’s leaders were blinded by the fact that, in 1977, Black superstars were still prominent. Though Henry Aaron, Willie Mays, and Jackie Robinson were gone, players such as Joe Morgan, Reggie Jackson, Willie Stargell, and an aging Lou Brock were thrilling fans. MLB had two Black MVPs in George Foster and Rod Carew; two Black Rookies of the Year in Eddie Murray and Andre Dawson; a host of rising Black talents including Dave Parker, Dave Winfield, and Willie Randolph; and a Black No. 1 draft pick in Harold Baines.

That year, the most MLB did to reconnect with Black youth was to use Jackie Robinson Week – the 30-year commemoration of his breaking the color barrier during All-Star Week – to, as Irvin put it, “make them (young Blacks) aware of Robinson’s contributions.”

That would not be enough.

At the game’s lower levels, the Black talent drain already was underway. For years, Black players had argued that teams had unwritten quotas governing how many Black players they would have on their rosters. Because of these quotas, they believed that Black players had to be great – or else they would never get a real chance to carve out playing careers. Black kids believed this, too. Gates Brown, a former Detroit Tiger who worked in the organization after his retirement, said in 1977 that when he tried to recruit Black kids, “you still get the same line: you got to be twice as good as the White kid.”

Brown had no remedy except to say, “Be tough, hang in there.”

Crucially, baseball’s scouting system had changed. According to Hall of Famer Frank Robinson, when barrier breakers like Jackie Robinson came in, most teams started to sign Black talent, believing that was the best and cheapest way to compete. A generation later, however, scouts felt that they had tapped that mine. So they stopped looking for Black gems – or even showing up at all. One Black player concluded that White scouts refused to go to the inner city and scout Black players because they were afraid. Meanwhile, Black scouts were disappearing. Of the 566 official MLB scouts in 1982, only 15 were Black. Fourteen teams did not have any full-time Black scouts. That led the great Joe Morgan to ask, “How can you expect to sign a lot of Black players if you don’t have a lot of Black scouts?”

This lack of Black scouts coincided with teams’ increasing dependency on drafting college players. From 1972 to 1982, MLB teams went from drafting 334 collegians to 615, a near reversal of numbers when compared to high school players. Pittsburgh Pirates player Bill Madlock believed that this was intentional, done because fewer Black players played in college. Purposeful or not, the change had a huge impact on the Black talent pool for two reasons. First, by the 1970s, a number of Historically Black Colleges and Universities, or HBCUs, had begun dropping baseball. As Black Sports reported in a 1971 article, these schools lacked the resources to field teams. Most did not offer scholarships. Without that, many potential players instead chose to concentrate on their books. Second, the predominantly White institutions that could offer baseball scholarships were limited to only 13 per team. As a result, a host of young Black athletes who looked to college sports for potential economic mobility saw limited chances in baseball and so tried their luck with football and basketball, "They seemed to be turned off by baseball,” said Brown, the Tigers lifer. “More concentrate on football and basketball. There's more money, and they get to the big-time quicker."

Baseball also lost Black talent because America’s structural inequalities had taken their toll on the inner city game. In the late 1970s, youth coaches noted that while the sport was doing fine in the mostly White suburbs, inner cities struggled to field teams from the Little League to high school levels. As one youth leader in Miami put it, they lacked money for league sponsorships, kids couldn’t afford equipment, and the facilities were neglected. MLB officials understood this, and, Irvin concluded, “they don’t have the wide-open spaces for baseball anymore.” But the sport didn’t do anything about it.

With MLB unwilling to truly step in, it mostly fell on individual Black players to do what they could. In the late 1980s in Los Angeles – a city that had a rich history of producing Black talent – Black stars such as Darryl Strawberry and Eric Davis saw the warning signs. They returned to practice at Harvard Park, a public gathering place in the middle of one of the most dangerous sections of the city, the type of place where you were more likely to see someone struck by a bullet than struck out by a pitch. They helped youngsters with tips and gear and otherwise remained a presence, letting Black kids know that baseball could be a future home for them, too. Soon, programs like Reviving Baseball in the Inner Cities, which is run by MLB and still exists today, would follow their lead to provide kids with opportunities to play ball.

But by then it was too late. Baseball’s failure to get out in front of the problem in the 1970s and early 1980s had real and lasting consequences. The number of Black players in MLB remained relatively stable from 1977 to 1987 – and then the well nearly dried up. Today, the number of African-American players sits at an all-time low of roughly 7 percent. If MLB wants to increase Black American participation in the game, the league will have to make massive investment in youth baseball, bring more Black decision-makers into the fold, and stop repeating the same tired lines that the game isn’t as cool or appealing as basketball and football.

Today’s baseball fans, a demographic group that itself is also shrinking, have far fewer Black stars to get excited about. Yesterday’s icons warned us this day was coming. But the league never righted the ship. And that makes it fair to ask: Even now, is the league truly dedicated to fixing this problem?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fifty Years Ago, Satchel Paige Brought the Negro Leagues to Baseball's Hall of Fame

https://sciencespies.com/history/fifty-years-ago-satchel-paige-brought-the-negro-leagues-to-baseballs-hall-of-fame/

Fifty Years Ago, Satchel Paige Brought the Negro Leagues to Baseball's Hall of Fame

Eyewitnesses said that Satchel Paige, one of the best pitchers baseball will ever see, would tell his teammates to sit on the field, so confident that he’d strike out the batter on his own.

The right-handed ace’s showmanship was backed up by the remarkable athletic ability on display with his deadly accurate fastball. Over an estimated 2,600 innings pitched, Paige registered more than 200 wins and, impressively, more than 2,100 strikeouts. And those numbers are incomplete—many of his games, having been played in the Negro Leagues, going unrecorded.

“Satchel was pitching in a way if, just based on his performance as a pitcher, he would’ve ranked as one of the all-time greats, if not the greatest,” says Larry Tye, author of the 2009 biography Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend.

For 20 years after he more-or-less hung up his cleats, however, the National Baseball Hall of Fame, where baseball greats from Babe Ruth to Walter Johnson were enshrined, didn’t have room for Paige or any other Negro Leaguers. Because it was a different league, segregated from the majors solely by race, the Hall hadn’t even considered its players eligible for induction. But in 1971, the Cooperstown, New York, institution finally began to recognize the accomplishments of players whose case for greatness rested on their performance in the Negro Leagues, starting with Paige.

Paige reclines in an easy chair in the St. Louis Browns’ bullpen on June 28, 1952. Team president Bill Veeck, who was known for wacky publicity stunts, purchased the chair for Paige, who was already in his mid-forties.

(Bettmann / Getty Images)

A native of Mobile, Alabama, Leroy Paige was born in 1906 and grew up with 11 siblings. Given the nickname “Satchel” for a contraption he made for carrying passengers’ bags at a local train station, he found his talent for baseball at a correctional school.

At 18, he joined the Mobile Tigers, a black semi-professional team. No stranger to barnstorming—the practice of teams traveling across the country to play exhibition matches—Paige debuted in the Negro Leagues in 1926 for the Chattanooga Black Lookouts. Among the teams he played for were the Birmingham Black Barons, the Baltimore Black Sox, the Pittsburgh Crawfords (surrounded by other legends, including Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell), and the Kansas City Monarchs. Paige won four Negro American League pennants with the Monarchs from 1940 to 1946.

Paige was far from the only phenom in the Negro Leagues. Gibson was a monumental power hitter; Oscar Charleston played a gritty, all-around game; and Bell was known for his beyond-human speed, just to name a few. But when it came to star quality, Paige possibly surpasses them all.

Satchel Paige (back row, second from left) posing with the Pittsburgh Crawfords at their spring training site at Hot Springs, Arkansas, in 1932. Pittsburgh was one of several Negro League teams that Paige would play for during his career.

(Mark Rucker / Transcendental Graphics via Getty Images)

“He’s probably the biggest drawing card in the history of the Negro Leagues,” says Erik Strohl, vice president of exhibitions and collections at the Hall of Fame.

Legend surrounds Paige with stories of his remarkable feats, and some of it was even self-produced: He kept track of his own statistics and the numbers he would provide to others were astounding, if not sometimes inconsistent. While a lack of written accounts at many of his pitching performances has created issues of veracity, the confirmed information available still suggests that his accomplishments are befitting of his prestige.

“When you say that he is a legend and one of the greatest players of all time, it may seem like an exaggeration,” says Strohl, “and it’s hard to quantify and qualify, but I think probably, undoubtedly that was true in terms of the length and swath of his career.”

“He had great speed, but tremendous control,” says historian Donald Spivey, author of the 2013 book If You Were Only White: The Life of Leroy “Satchel” Paige. “That was the key to his success,” he adds, which paired with Paige’s ability to identify batters’ weaknesses from their pitching stances.

Spivey says that Paige’s prestige was a boon even for his opponents, as crowds would flock to the games where he was pitching. “The man was a tremendous drawing card,” he notes. He earned a reputation for jumping from one team to the next, depending on who offered the most money.

“He got away with it because he was so reliable,” says Tye. “He gave you the ability to draw in fans.

Not unlike other talented Negro Leaguers of the era, Paige wanted an opportunity with the MLB. Midway through the 1948 season, he got his chance when he signed with the Cleveland Indians. He was certainly an atypical “rookie”, entering the league when he was 42 after more than 20 years of Negro League competition (Jackie Robinson, for comparison, joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947 when he was 28.) Paige managed to make his time count: he won six games amid a tense battle for the American League pennant, and Cleveland went on to take both the pennant and the World Series victory.

Though his debut MLB season was successful, he spent just one more year with the Indians in 1949 before joining the St. Louis Browns in 1951. Following a three-year stint with St. Louis, Paige’s career in the MLB appeared over. However, he continued playing baseball in other leagues, and still found a way to make a brief one-game, three-inning appearance with the Kansas City Athletics in 1965 at the age of 59, not giving up a single run.

Paige’s time in Major League Baseball was impressive for a player entering the league in their 40s, asserts Phil S. Dixon, author of multiple books about the Negro Leagues.

“He also helped those teams because people wanted to see Satchel Paige,” Dixon says. “Not only was he a decent pitcher, he was an amazing draw.”

The Negro Leagues were both the stage at which Paige dazzled audiences for years on end, and the mark of a barrier separating him and other black players from baseball’s biggest stage for years. That barrier would, for a time, be perpetuated by the Hall of Fame.

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn (front row, center) meets with the new committee established to nominate Negro League players to the Hall of Fame at his office on February 4, 1971. Among the members is sportswriter Sam Lacy (back, center).

(Charles Ruppmann / NY Daily News via Getty Images)

Despite the impact that the Negro Leagues had on baseball and American culture, by the 1960s, just two players associated with them had been recognized as Hall of Famers. Robinson was the first black player inducted, in 1962, and seven years later his former teammate Roy Campanella joined him. The two had achieved entry off the merits of their MLB careers, however, whereas icons like Paige and Gibson had either few or no seasons outside the Negro Leagues.

To those who played the game, their worthiness was not a matter of debate. On occasions when black squads faced off against their white contemporaries, they won at least as often as not, if not more. In 1934 Paige and star MLB pitcher Dizzy Dean had their barnstorming teams—one black, one white—face off against each other six times in exhibition play. Paige’s crew won four of those six meetings, including a tense 1-0 victory at Chicago’s Wrigley Field after 13 innings.

“Their role in the black community was one that said, ‘We can play as good as anybody,’” says Dixon. “‘And there’s no reason for us not being in the major leagues, because not only can we play all of those guys, we can beat those guys.”

In the prime of Paige’s Negro League career, New York Yankees’ outfielder Joe DiMaggio once described Paige as the “best and fastest” pitcher he’d ever played against. Former Boston Red Sox star Ted Wiliams used part of his Hall of Fame speech in 1966 to mention the exclusion of Paige and other black players

“I hope that someday the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson in some way can be added as a symbol of the great Negro players that are not here only because they were not given the chance,” Williams said to the crowd, a speech that Strohl notes occurred amid the civil rights movement.

Satchel Paige poses with his Baseball Hall of Fame plaque on his induction day, August 9, 1971, at Cooperstown, New York. Paige was the third black player inducted to the Hall, and the first inducted for Negro League achievements.

(Associated Press)

Meanwhile, sportswriters supportive of the cause used their platforms to argue for Negro Leaguers’ presence in the Hall. Members of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America, the body responsible for selecting Hall members, also created a committee in 1969 to advocate for Negro League inductions.

MLB commissioner Bowie Kuhn, elected in 1969, publicly welcomed to the idea of putting Negro League players in the Hall of Fame. In his 1987 autobiography Hardball: The Education of a Baseball Commissioner, Kuhn stated that he didn’t buy into the reasons against inducting Negro League players.

“I found unpersuasive and unimpressive the argument that the Hall of Fame would be ‘watered down’ if men who had not played in the majors were admitted,” Kuhn wrote, looking back at the time.

“Through no fault of their own,” he added, “the black players had been barred from the majors until 1947. Had they not been barred, there would have been great major-league players, and certainly Hall of Famers, among them.”

With Kuhn’s help, the Hall formed their Negro leagues committee in 1971, comprised of several men including Campanella and black sportswriters Sam Lacy and Wendell Smith. They were tasked with considering the merits of past players and executives for inclusion, and they announced Paige was their inaugural nominee in February.

Nevertheless, the Hall ran into controversy in how they planned to honor the Negro Leaguers: with a separate section, apart from the Major League inductees. Among the reasons cited were that some of the proposed inductees would not meet the minimum of ten MLB seasons competed in like other honorees. Instead of appearing like a tribute, the move was viewed by many as another form of segregation.

“Technically, you’d have to say he’s not in the Hall of Fame,” said Kuhn at the time, according to the New York Times. “But I’ve often said the Hall of Fame isn’t a building but a state of mind. The important thing is how the public views Satchel Paige, and I know how I view him.”

Backlash to the idea, from sportswriters and fans alike, was plentiful. Wells Trombly, writing for the Sporting News, declared, “Jim Crow still lives. … So they will be set aside in a separate wing. Just as they were when they played. It is an outright farce.”

New York Post sports columnist Milton Gross rejected Kuhn’s rosy interpretation, writing, “The Hall of Fame is not a state of mind. It is something semi-officially connected with organized baseball that is run by outdated rules which, as Jackie Robinson said the other day, ‘can be changed like laws are changed if they are unjust.’”

With the backdrop of backlash and an upcoming election, the Hall changed their mind in July of that year.

The pitcher himself stated that he was not worried where his tribute would be stored. “As far as I am concerned, I’m in the Hall of Fame,” he said. “I don’t know nothing about no Negro section. I’m proud to be in it. Wherever they put me is alright with me.”

Tye argues that it was still a painful experience for Paige. “Satchel had dealt with so much affront that I think he took it with quite a bit of class when they offered to let him into the segregated Hall,” he says. “But it clearly was devastating to him.”

A player whose name drew crowds and whose performances dazzled them, Paige was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in August 1971. A statue of Paige now adorns the Hall of Fame’s courtyard. It was installed in 2006, which is also the most recent year any Negro Leaguer has been inducted into the Hall.

He is portrayed with his left leg up in the air. His right hand nestles the baseball. Eyes closed, Satchel is preparing a pitch for eternity.

“I am the proudest man on the earth today, and my wife and sister and sister-in-law and my son all feel the same,” said Paige at the end of his Hall of Fame acceptance speech, reported the New York Times. “It’s a wonderful day and one man who appreciates it is Leroy Satchel Paige.”

#History

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Made Magic Johnson So Great Ervin Johnson Bio

When you think of Ervin "Magic" Johnson's video game, you ask yourself exactly how he can have been one of the best point player in the history of the NBA. learn more lacked fantastic rate his steps weren't precisely smooth or graceful, and also he wasn't an excellent leaper. He had not been precisely a fantastic shooter as well. What he did do that was fantastic, was play each minute of every game with one thought in his mind. He asked himself "What can I do, today, to help my team win this basketball game? Throughout the 1980's nobody generated the right response regularly than Magic did. 9 times in 12 seasons Magic Johnson led the Los Angeles Lakers to the NBA finals. 5 of those times the Lakers won the NBA champion. During three of those champion victories, Magic Johnson was awarded the MVP. Interesting Facts About Magic Johnson: Among Magic's most embarrassing moments was when he was leading the LA Lakers out of the storage locker area in his first basketball video game ever before as a Laker. He was so nervous that he forgot to tie the drawstring on his warm up pants, which created him to fail on his face when he headed out on the court to take his heat up shots.Every time that the Lakers played in Detroit, his mother made fried poultry as well as repairings for the entire team. Her sweet potato pie became practice after the game.When Magic moved right into his Bel Air manor, the child that lived next to him asked if Magic Johnson might play. The following point the boy recognized, Magic Johnson had actually grabbed a pair of footwear as well as was out shooting baskets with him! Magic Johnson Timeline Bio 1980: Wins first NBA Championship trophy 1982: Averages an NBA best 2.7 takes per video game 1987: Leads the league in assists for the 4th time 1991: Wins second All Star MVP award Other fascinating truths regarding Magic Johnson: As a child, Magic Johsnon came from the Boys as well as Girls Club in Lansing, Michigan. As a grown-up he supports their nationwide organization and also the Challenger Club of South Central Los Angeles. He also arranges a Mid Summer's evening's Magic, a basketball video game to benefit the United University Fund. Given that learning he was HIV favorable back in 1991 he has established up the Magic Johnson AIDS structure. Till today Magic Johnson has did marvels for areas around the world with his philanthropic initiatives. Magic Johnson's Bio. Profession highlights, interesting truths, and his timeline bio. Throwback Jerseys NBA, NFL, MLB, and also NHL throwback jerseys. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VsOBT8u0HXM

1 note

·

View note

Note

Any feel good movies and queer movies recs? Thank you so much x

Oh anon. I’m so glad you asked. I’ll try to recommend mostly happy queer movies, but if I think it’s worth watching despite the unhappiness I will put in a warning. The feel good movies should be exactly what it says on the tin.

Ever After (1998): A take on the Cinderella story, it’s historical high romance (the costumes!), girl power, and in my opinion a great twist on a classic fairy tale. Also Leonardo DaVinci (yes, the painter) is the fairy godmother. I would not lie about this.

Undrafted (2016): An indie movie made about a local league baseball game immediately following the MLB draft, and the star player of one team is not picked. Now it remains to be seen if they can pull together to win. It’s touch and go in places so far as the writing goes, but it’s got a lot of heart.

The Princess Bride (1987): I may talk about this movie too much, and I don’t want to over hype it but like. It’s a classic. Extremely quotable and romantic af (without being mushy), it’s also an adventure story with villains that you love to hate.

Pee Mak (2013): Ok, I need you to bear with me on this one. This is a Thai movie that is a horror comedy romance. (Light on the horror.) Basically it’s a very funny ghost story that also has a really cute love story plot. I wish I could explain it better than that, but I highly recommend it.

Arsenic and Old Lace (1944): This is a classic dark comedy (my favorite kind, but not for everyone). A man is just trying to marry his fiance in peace, but the day goes south when he realizes his sweet old aunts have been poisoning drifters and burying them in their basement (using their brother who thinks he’s Teddy Roosevelt digging the Panama Canal.) Oh also there’s a recently escaped convict hiding out in the house. Hijinks ensue.

Beautiful Boxer (2003): Another Thai movie, this is based on the true story of a trans boxer (amab). A lot of angst, but ultimately a happy ending. They do not use a trans actor though, a male kickboxer was used (although I thought he gave a good performance).

The Adventures of Priscilla: Queen of the Desert (1994): An Australian movie that follows two gay male drag queens and one trans woman (also a drag queen) in their trip across the desert on their way to a show. (One of the men is travelling to pick up his estranged son from his ex wife, but the other two don’t initially know this.) Not the most politically correct of movies, but it ends well.

Fingersmith (2005)/Tipping the Velvet (2002)/Maurice (1987): I put these all in the same line because they are all very similar, these are period BBC miniseries dramas based on books, and all end well. Fingersmith is a “lady’s maid” lesbian love story with a massive plot twist halfway through. Tipping the Velvet is one woman’s introduction into the world of male impersonation (and lesbianism). And Maurice is about a young man who goes to college and realizes he’s gay. (I’m grossly oversimplifying.)

My Beautiful Laundrette (1985): A movie about a young British-Pakistani man trying to make his way in the world by operating a laundrette. And his rocky-ish relationship with his ex-fascist punk boyfriend. Heavy on the drama, but ultimately ends happily.

A Single Man (2009): This is the only not-very-happy queer movie. It’s about a middle aged man’s grieving process after his partner is killed in a car accident. I thought it was very interesting because it’s set in the 60s so he can’t grieve openly. It’s also basically following him throughout the day he decides he will commit suicide so tw for that.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunday, June 05, 2022 Canadian TV Listings (Times Eastern)

WHERE CAN I FIND THOSE PREMIERES?: LORDS OF THE OCEAN (History Canada 2) 8:00am 2022 MTV MOVIE & TV AWARDS (MTV Canada) 8:00pm BATTLE ON THE BEACH (HGTV Canada) 9:00pm THE GREAT FOOD TRUCK RACE (Food Network Canada) 9:00pm WATERGATE: BLUEPRINT FOR A SCANDAL (CNN) 9:00pm 2022 MTV MOVIE & TV AWARDS: UNSCRIPTED (MTV Canada) 10:00pm

WHAT IS NOT PREMIERING IN CANADA TONIGHT OUR DREAM WEDDING (Premiering on June 11 on Super Channel Heart & Home at 12:40pm) DEADLY YOGA RETREAT (TBD - Lifetime Canada)

NEW TO AMAZON PRIME CANADA/CBC GEM/CRAVE TV/DISNEY + STAR/NETFLIX CANADA:

DISNEY + STAR GENDER REVOLUTION: A JOURNEY WITH KATIE COURIC

RUGBY (TSN5) 12:00pm: Old Glory DC vs. Toronto Arrows

MLB BASEBALL (SN1) 1:30pm: Twins vs. Jays (SN Now) 4:00pm: Red Sox vs. A’s (TSN2) 7:00pm: Cardinals vs. Cubs

NHL HOCKEY PLAYOFFS (CBC/SN) 3:00pm: Rangers vs. Lightning - Game #3

FIRE MASTERS (Food Network Canada) 7:00pm: The chefs hit the grills for the battle of the wild; In the Feast of Fire, the chefs serve up BBQ feasts.

THE JUBILEE PUDDING: 70 YEARS IN THE BAKING (CBC) 7:30pm: In The Queen's Jubilee year, this special follows Fortum & Mason's competition as it celebrates our Monarch's 70 years on the throne by finding an original and celebratory cake, tart or pudding fit for The Queen.

NBA BASKETBALL PLAYOFFS (SN1/SN) 8:00pm: Celtics vs. Warriors - Game #2

BEACH CABANA ROYALE (HGTV Canada) 8:00pm: Nicole "Snooki" Polizzi hosts a competition in which designers have one day to transform beach cabanas for three families; Egypt Sherrod and Orlando Soria decide which competitor incorporates the most innovative overhaul and earns the Golden Oar.

DISAPPEARANCE IN YELLOWSTONE (Lifetime Canada) 8:00pm: Jessie must fight against all odds to escape from the police and track down her daughter before she's killed.

THE QUEEN AND CANADA (CBC) 9:00pm: Adrienne Arsenault examines the relationship between the Queen and Canada.

VERY SCARY PEOPLE (HLN) 9:00pm (SERIES PREMIERE): From 1987 to 1992, rapes, abductions and murders of young women occur north of the U.S.-Canadian border; a tip leads cops to an unlikely suspect: a blond, blue-eyed accountant who lives with his wife in a pink house in the suburbs.

AMERICAN CARTEL (Investigation Discovery) 9:00pm/10:00pm/11:00pm (SERIES PREMIERE): The 2003 murder of police officer Matthew Pavelka leads to an international manhunt, millions of dollars seized, multiple homicides, and the discovery of the Mexican Cartel's infiltration of a U.S. street gang.

EXPLORER: THE DEEPEST CAVE (Nat Geo Canada) 10:00pm: World class cavers search underground mazes, twisting tunnels and dead ends in search of a passage that leads to the bottom of deepest cave on Earth.

DEVIL'S ADVOCATE: THE MOSTLY TRUE STORY OF GIOVANNI DI STEFANO (MSNBC) 10:00pm/11:00pm (SERIES PREMIERE): The story of dictators and major crime figures who were represented by a man masquerading as a lawyer.

#cdntv#cancon#canadian tv#canadian tv listings#fire masters#rugby#mlb baseball#nhl hockey#nba basketball

0 notes

Text

Stuart Scott

Stuart Orlando Scott (July 19, 1965 – January 4, 2015) was an American sportscaster and anchor on ESPN, most notably on SportsCenter. Well known for his hip-hop style and use of catchphrases, Scott was also a regular for the network in its National Basketball Association (NBA) and National Football League (NFL) coverage.

Scott grew up in North Carolina, and graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He began his career with various local television stations before joining ESPN in 1993. Although there were already accomplished African-American sportscasters, his blending of hip hop with sportscasting was unique for television. By 2008, he was a staple in ESPN's programming, and also began on ABC as lead host for their coverage of the NBA.

In 2007, Scott had an appendectomy and learned that his appendix was cancerous. After going into remission, he was again diagnosed with cancer in 2011 and 2013. Scott was honored at the ESPY Awards in 2014 with the Jimmy V Award for his fight against cancer, less than six months before his death in 2015 at the age of 49.

Early life

Stuart Orlando Scott was born in Chicago, Illinois on July 19, 1965 as the son of O. Ray and Jacqueline Scott. When he was 7, Scott and his family moved to Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Scott had a brother named Stephen and two sisters named Susan and Synthia.

He attended Mount Tabor High School for 9th and 10th grade and then completed his last two years at Richard J. Reynolds High School in Winston-Salem, graduating in 1983. In high school, he was a captain of his football team, ran track, served as Vice President of the Student Council, and was the Sergeant at Arms of the school's Key Club. Scott was inducted into the Richard J. Reynolds High School Hall of Fame during a ceremony on February 6, 2015, which took place during the Reynolds/Mt. Tabor (the two high schools that Scott attended) basketball game.

He attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity and was part of the on-air talent at WXYC. While at UNC, Scott also played wide receiver and defensive back on the football team. In 1987, Scott graduated from the UNC with a B.A. in speech communication. In 2001, Scott gave the commencement address at UNC where he implored graduates to celebrate diversity and recognize the power of communication.

Career

Following graduation, Scott worked as a news reporter and weekend sports anchor at WPDE-TV in Florence, South Carolina from 1987 until 1988. Scott came up with the phrase "as cool as the other side of the pillow" while working his first job at WPDE. After this, Scott worked as a news reporter at WRAL-TV 5 in Raleigh, North Carolina from 1988 until 1990. WRAL Sports anchor Jeff Gravley recalled there was a "natural bond" between Scott and the sports department. Gravley described his style as creative, gregarious and adding so much energy to the newsroom. Even after leaving, Scott still visited his former colleagues at WRAL and treated them like family.

From 1990 until 1993, Scott worked at WESH, an NBC affiliate in Orlando, Florida as a sports reporter and sports anchor. While at WESH, he met ESPN producer Gus Ramsey, who was beginning his own career. Ramsey said of Scott: "You knew the second he walked in the door that it was a pit stop, and that he was gonna be this big star somewhere someday. He went out and did a piece on the rodeo, and he nailed it just like he would nail the NBA Finals for ESPN." He earned first place honors from the Central Florida Press Club for a feature on rodeo.

ESPN

Al Jaffe, ESPN's vice president for talent, brought Scott to ESPN2 because they were looking for sportscasters who might appeal to a younger audience. Scott became one of the few African-American personalities who was not a former professional athlete. His first ESPN assignments were for SportsSmash, a short sportscast twice an hour on ESPN2's SportsNight program. After Keith Olbermann left SportsNight for ESPN's SportsCenter, Scott took his place in the anchor chair at SportsNight. After this, Scott was a regular on SportsCenter. At SportsCenter, Scott was frequently teamed with fellow anchors Steve Levy, Kenny Mayne, Dan Patrick, and most notably, Rich Eisen. Scott was a regular in the This is SportsCenter commercials.

In 2002, Scott was named studio host for the NBA on ESPN. He became lead host in 2008, when he also began at ABC in the same capacity for its NBA coverage, which included the NBA Finals. Additionally, Scott anchored SportsCenter's prime-time coverage from the site of NBA post-season games. From 1997 until 2014, he covered the league's finals. During the 1997 and 1998 NBA Finals, Scott did one-on-one interviews with Michael Jordan. When Monday Night Football moved to ESPN in 2006, Scott hosted on-site coverage, including Monday Night Countdown and post-game SportsCenter coverage. Scott previously appeared on NFL Primetime during the 1997 season, Monday Night Countdown from 2002 to 2005, and Sunday NFL Countdown from 1999 to 2001. Scott also covered the MLB playoffs and NCAA Final Four in 1995 for ESPN.

Scott appeared in each issue of ESPN the Magazine, with his Holla column. During his work at ESPN, he also interviewed Tiger Woods, Sammy Sosa, President Bill Clinton and President Barack Obama during the 2008 presidential campaign. As a part of the interview with President Barack Obama, Scott played in a one-on-one basketball game with the President. In 2004, per the request of U.S. troops, Scott and fellow SportsCenter co-anchors hosted a week of programs originating from Kuwait for ESPN's SportsCenter: Salute the Troops. He hosted a number of ESPN game and reality shows, including Stump the Schwab, Teammates, and Dream Job, and hosted David Blaine's Drowned Alive special. He hosted a special and only broadcast episode of America's Funniest Home Videos called AFV: The Sports Edition.

Style

While there were already successful African-American sportscasters, Scott blended hip-hop culture and sports in a way that had never been seen before on television. He talked in the same manner as fans would at home. ESPN director of news Vince Doria told ABC: "But Stuart spoke a much different language ... that appealed to a young demographic, particularly a young African-American demographic." Michael Wilbon wrote that Scott allowed his personality to infuse the coverage and his emotion to pour out.

Scott also integrated pop culture references into his reports. One commentator remembered his style: "he could go from evoking a Baptist preacher riffing during Sunday morning service ('Can I get a witness from the congregation?!'), to quoting Public Enemy frontman Chuck D ('Hear the drummer get WICKED!') In 1999, he was parodied on Saturday Night Live by Tim Meadows. Scott appeared in music videos with the rappers LL Cool J and Luke, and he was cited in "3 Peat", a Lil Wayne song that included the line: "Yeah, I got game like Stuart Scott, fresh out the ESPN shop." In a 2002 segment of NPR's On the Media, Scott revealed one approach to his anchoring duties: "Writing is better if it's kept simple. Every sentence doesn't need to have perfect noun/verb agreement. I've said 'ain't' on the air. Because I sometimes use 'ain't' when I'm talking."

As a result of his unique style, Scott and ESPN received a lot of hate mail from people who resented his color, his hip-hop style, or his generation. In a 2003 USA Today survey, Scott finished first in the question of which anchor should be voted off SportsCenter, but he also was second to Dan Patrick in the 'definitely keep him' voting. Jason Whitlock criticized Scott's use of Jay-Z's alternate nickname, "Jigga", at halftime of Monday Night Football as ridiculous and offensive. Scott never changed his style and ESPN stuck with him.

Catchphrases

Scott became well known for his use of catch phrases, following in the SportsCenter tradition begun by Dan Patrick and Keith Olbermann. He popularized the phrase booyah, which spread from sports into mainstream culture. Some of the catchphrases included:

"Boo-Yah!"

"Hallah"

"As cool as the other side of the pillow"

"He must be the bus driver cuz he was takin' him to school."

"Holla at a playa when you see him in the street!"

"Just call him butter 'cause he's on a roll"

"They Call Him the Windex Man 'Cause He's Always Cleaning the Glass"

"You Ain't Gotta Go Home, But You Gotta Get The Heck Outta Here."

"He Treats Him Like a Dog. Sit. Stay."

"And the Lord said you got to rise Up!"

"Make All the Kinfolk Proud ... Pookie, Ray Ray and Moesha"

"It's Your World, Kid ... The Rest of Us Are Still Paying Rent"

"Can I Get a Witness From the Congregation?"

"Doing It, Doing It, Doing It Well"

"See ... What Had Happened Was"

Legacy

ESPN president John Skipper said Scott's flair and style, which he used to talk about the athletes he was covering, "changed everything." Fellow ESPN Anchor, Stan Verrett, said he was a trailblazer: "not only because he was black – obviously black – but because of his style, his demeanor, his presentation. He did not shy away from the fact that he was a black man, and that allowed the rest of us who came along to just be ourselves." He became a role model for African-American sports journalists.

Personal life

Scott was married to Kimberly Scott from 1993 to 2007. They had two daughters together, Taelor and Sydni. Scott lived in Avon, Connecticut. At the time of his death, Scott was in a relationship with Kristin Spodobalski. During his Jimmy V Award speech, he told his teenage daughters: "Taelor and Sydni, I love you guys more than I will ever be able to express. You two are my heartbeat. I am standing on this stage here tonight because of you."

Eye injury

Scott was injured when he was hit in the face by a football during a New York Jets mini-camp on April 3, 2002, while filming a special for ESPN, a blow which damaged his cornea. He received surgery but afterwards suffered from ptosis, or drooping of the eyelid.

Appendectomy and cancer

After leaving Connecticut on a Sunday morning in 2007 for Monday Night Football in Pittsburgh, Scott had a stomachache. After the stomachache worsened, he went to the hospital instead of the game and later had his appendix removed. After testing the appendix, doctors learned that he had cancer. Two days later, he had surgery in New York that removed part of his colon and some of his lymph nodes near the appendix. After the surgery, they recommended preventive chemotherapy. By December, Scott—while undergoing chemotherapy—hosted Friday night ESPN NBA coverage and led the coverage of ABC's NBA Christmas Day studio show. Scott worked out while undergoing chemotherapy. Scott said of his experience with cancer at the time: "One of the coolest things about having cancer, and I know that sounds like an oxymoron, is meeting other people who've had to fight it. You have a bond. It's like a fraternity or sorority." When Scott returned to work and people knew of his cancer diagnosis, the well-wishers felt overbearing for him as he just wanted to talk about sports, not cancer.

The cancer returned in 2011, but it eventually went back into remission. He was again diagnosed with cancer on January 14, 2013. After chemo, Scott would do mixed martial arts and/or a P90X workout regimen. By 2014, he had undergone 58 infusions of chemotherapy and switched to chemotherapy pills. Scott also went under radiation and multiple surgeries as a part of his cancer treatment. Scott never wanted to know what stage of cancer he was in.

Jimmy V Award

On July 16, 2014, Scott was honored at the ESPY Awards, with the Jimmy V Award for his ongoing battle against cancer. He shared that he had 4 surgeries in 7 days in the week prior to his appearance, when he was suffering from liver complications and kidney failure. Scott told the audience, "When you die, it does not mean that you lose to cancer. You beat cancer by how you live, why you live, and in the manner in which you live." At the ESPYs, a video was also shown that included scenes of Scott from a clinic room at Johns Hopkins Hospital and other scenes from Scott's life fighting cancer. Scott ended the speech by calling his daughter up to the stage for a hug, "because I need one," and telling the audience to "have a great rest of your night, have a great rest of your life."

Death

On the morning of January 4, 2015, Scott died of cancer in his home in Avon, Connecticut, at the age of 49.

Tributes

ESPN announced: "Stuart Scott, a dedicated family man and one of ESPN's signature SportsCenter anchors, has died after a courageous and inspiring battle with cancer. He was 49." ESPN released a video obituary of Scott. Sports Illustrated called ESPN's video obituary a beautiful and moving tribute to a man who died "at the too-damn-young age of 49." Barack Obama paid tribute to Scott, saying:

I will miss Stuart Scott. Twenty years ago, Stuart helped usher in a new way to talk about our favorite teams and the day's best plays. For much of those twenty years, public service and campaigns have kept me from my family – but wherever I went, I could flip on the TV and Stu and his colleagues on SportsCenter were there. Over the years, he entertained us, and in the end, he inspired us – with courage and love. Michelle and I offer our thoughts and prayers to his family, friends, and colleagues.

A number of National Basketball Association athletes—current and former—paid tribute to Scott, including Stephen Curry, Carmelo Anthony, Kobe Bryant, Steve Nash, Jason Collins, Shaquille O'Neal, Magic Johnson, Dwyane Wade, LeBron James, Michael Jordan, Bruce Bowen, Dennis Rodman, James Worthy and others. A number of golfers paid tribute to Scott: Tiger Woods, Gary Player, David Duval, Lee Westwood, Blair O'Neal, Jane Park and others. Other athletes paid tribute including Robert Griffin III, Russell Wilson, Jon Lester, Lance Armstrong, Barry Sanders, J. J. Watt, David Ortiz and Sheryl Swoopes. UNC basketball coach Roy Williams called him a "hero." Arizona Cardinals head coach Bruce Arians said: "We lost a football game but we lost more this morning. I think one of the best members of the media I've ever dealt with, Stuart Scott, passed away."

Colleagues Hannah Storm and Rich Eisen gave on-air remembrances of Scott. On SportsCenter, Scott Van Pelt and Steve Levy said farewell to Scott and left a chair empty in his honor. Tom Jackson, Cris Carter, Chris Berman, Mike Ditka and Keyshawn Johnson from NFL Countdown shared their memories of Scott.

During Ernie Johnson, Jr.'s acceptance speech for his 2015 Sports Emmy Award for Best Studio Host, he gave his award to Scott's daughters, saying it "belongs with Stuart Scott". At the 67th Primetime Emmy Awards and at the 2015 ESPY Awards, Scott was included in the "in memoriam" segment, a rare honor for a sports broadcaster.

Filmography

He Got Game (1998)

Disney's The Kid (2000)

Drumline (2002)

Love Don't Cost A Thing (2003)

Mr. 3000 (2004)

Herbie: Fully Loaded (2005)

The Game Plan (2007)

Enchanted (2007)

Just Wright (2010)

Television

Arli$$ (2000)

I Love the '80s (2002)

Soul Food (2003)

She Spies (2005)

I Love the '70s (2003)

One on One (2004)

Stump the Schwab (2004–06)

Dream Job (2004)

Teammates (2005)

I Love the '90s (2004)

I Love the Holidays (2005)

I Love Toys (2006)

Black to the Future (2009)

Publications

Scott, Stuart; Platt, Larry (2015). Every Day I Fight. Blue Rider Press. ISBN 978-0-399-17406-3.

Wikipedia

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chirco: Trammell finally gets his due with jersey retirement

Detroit - No. 3 finally has been retired by the Tigers.

Twenty-two years after playing his last game in the “Old English D,” Alan Stuart Trammell got his due by getting his No. 3 jersey retired and placed on the brick wall in left center field during a pregame ceremony Sunday afternoon at Comerica Park.

Numerous former teammates of Trammell were in attendance for the ceremony, including 1984 rotation members Jack Morris, Dan Petry and Dave Rozema, Trammell’s longtime double-play mate Lou Whitaker and outfielder Kirk Gibson.

Tigers radio play-by-play man Dan Dickerson emceed the event, and Gibson and Whitaker took the podium to reflect on the player that “Tram” was and the man that he is.

Gibson, for one, called Tram “a selfless person and player.”

Trammell meant so much to Whitaker when they were teammates that Whitaker made an exception Sunday: he took a flight to see Tram.

“I’m here today because of Tram,” Whitaker said. “It’s always hard to get me to leave my comfort zone. But for Tram, whatever it takes.”

And when Trammell took the podium, he gave Tigers fans even more reason to love him.

In front of an energetic crowd, Trammell delivered a speech that made everyone in the ballpark come to their feet multiple times for a raucous round of applause.

He expressed dignity and humility in thanking his teammates for helping make him into the Hall-of-Fame talent he became.

“To play with Lou was an absolute joy,” Trammell said. “Without him, I wouldn’t be here today.”

He told the fans that he played for them, and that it was his “pleasure” to wear the “Old English D” his whole entire playing career.

He played 19 of his 20 MLB seasons alongside Whitaker, the two of them forming the longest double-play tandem in MLB history from 1977-95. “Sweet Lou” retired a season before Tram hung up the cleats for good in 1996.

In playing all 20 of his major league seasons in Detroit, Trammell became one of two players in Tigers history to play 20-or-more years in the big leagues and to play all of them for the Tigers.

The other player: “Mr. Tiger,” Al Kaline, who played 22 seasons in Motown.

Trammell finished his Hall-of-Fame career with 185 home runs, 1,003 runs batted in, a .285 batting average and a .767 on-base plus slugging percentage.

He also made six All-Star teams, and won four Gold Gloves and three Silver Slugger awards.

More importantly, though, he always carried himself with class both on and off the diamond, and endeared himself to all those that came across his path.

“My hope is that when fans come to Comerica Park and look up and see No. 3, the story that will be told will be of someone who played the game the right way, was consistent and accountable,” Trammell said.

Rest assure, Tram, the story will be just that, and will be told for many years to come.

Other numbers and accomplishments:

According to Baseball-Reference.com, Trammell finished with 70.7 wins above replacement, a higher WAR than fellow Hall-of-Fame shortstops Barry Larkin (70.4) and Ernie Banks (67.5).

Tram recorded at least three WAR a season from 1980-91. During the same span, he averaged 5.2 WAR a year, won World Series MVP with the “Bless You Boys” in 1984 and was the runner-up for the AL MVP in 1987.

Follow the writer of this story, Vito Chirco, on Twitter @VitoJerome. Follow the Detroit Sports Podcast Network on Twitter @DetroitPodcast.

www.detroitsportspodcast.com

The Detroit Sports Podcast Network was founded in 2013, and can be listened to anywhere podcasts are found, including on ITunes, Stitcher and Podomatic.

1 note

·

View note