Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

A Trip Through Tribunal History in Celebration of the Hundredth Anniversary of Judicial 3000

It is hard to believe that there was a time when humans lived without “Judicial 3000”. “Judicial 3000” is of course an artificial intelligence program which calculates information to the closest degree in order to determine the fairest solution to various legal conflicts. To celebrate the hundredth anniversary of this program, the staff at the “The Bob Loblaw Law Blog” are looking back at a much more complicated and tenacious time in legal history when mere human mortals sat around and decided various legal and fairness issues. To do this we the staff at the ”The Bob Loblaw Law Blog” traveled to planet Westlaw where we were granted access to various different tribunal hearings. Two caught our attention and we decided to share those with our gracious readers today.

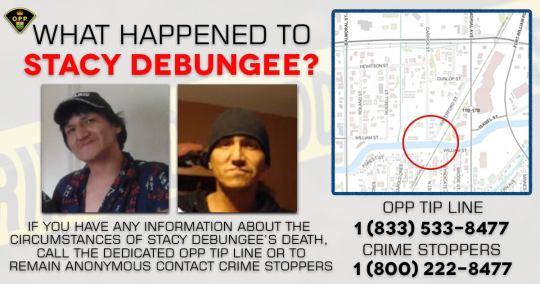

Obviously, we have all heard our history teacher bots talk about the issue of policing in the 2000s, all of which culminated in the tense North American Black Lives Matter protests in the year 2020. The relationship between the citizenry and police was tense particularly within marginalized groups in the earth state formally known as Canada. This remains an important time in history and as such we decided to bring you a glimpse into one of the ways in which such issues were handled. Namely, we bring you an October 17th, 2023, hearing from the Ontario Civilian Police Commission (OCPC).

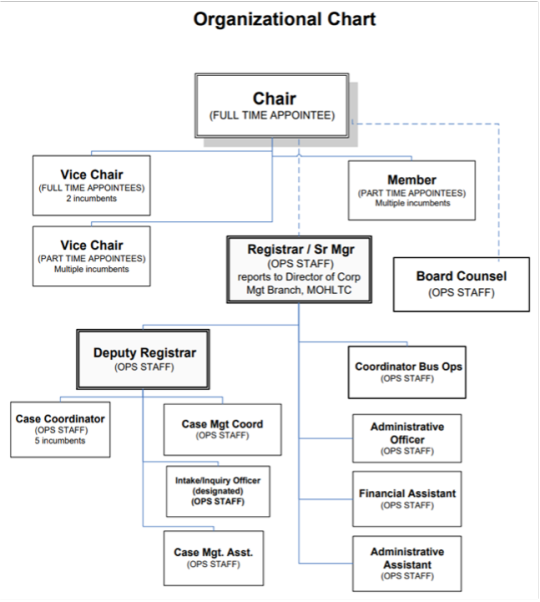

According to its own website, OCPC was among three civilian police oversight agencies in Ontario. The other two are Special Investigation Unit and Office of the Independent Police Review Director. Before politician-bots ran a strictly centralized government and “Judicial 3000” dealt out remedies for injured parties in a variety of fields, certain legislative documents gave power to administrative tribunals to resolve conflicts. The OCPC got its powers and duties from the Police Services Act, section 22(1) which empowered the board members to uphold prescribed standards of police services. While that is the source of its power, the source of the OCPC’s existence is the Adjudicative Tribunals Accountability, Governance and Appointments Act of 2009. This document chronicles the course of conduct expected of tribunals.

Essentially, the narrative the police adhered to was that Mr. Debungee had been drunk and fallen into the Bay. So, what’s the issue here? Well, the issue is that the death was suspicious and the result of murder. The bigger issue? A private investigator hired by the family discovered this and not the police officer in charge of the investigation. This is where complaints against the police officer began to be filed. From the Office of the Independent Police Review Director to our very own OCPC where appeals are sought.

According to the Ontario tribunal website, the OCPC had two divisions, one that is adjudicative and one that is investigative. The former deals with appeals of disciplinary matters, budgetary disputes and other functions while the latter deals with public complaints on the conduct of members within the police force. The hearing our blog had access to was an adjudicative one. The OCPC panel was hearing an appeal from the decision of a police disciplinary hearing for Officer Shawn Harrison. We were only able to recover records until November 2023 and by that point the board had not yet made a decision on this hearing. Bad news for those interested to hear the final verdict, spoiler alert; we do not know.

The mentioned OCPC website explained that the OCPC had the authority to confirm, vary or revoke a decision of the hearing officer. It also has the authority to replace the decision with one of its own or call for a new hearing to take place. Therefore, we can assume that three hundred years ago, the OCPC had decided on one of these options especially considering that the OCPC does not, according to its own website, resort to alternative dispute resolution due to its jurisdiction.

Shawn Harrison v Thunder Bay Police Services – OCPC Hearing:

This hearing began with a little bit of confusion, counsel for Shawn Harrison, the police officer, admitted to neglect on the part of his client but wanted to appeal the issue in order for the neglect charges to remain but in a much more constrained manner. The counsel for Debungee had a hard time with this but finally, they were able to see eye to eye on the matter and move on. David Butt, Mr. Harrison’s lawyer, rested his appeal on four arguments. He first argued that errors were made in the analysis of guilt in the charge of neglect of duty. Then he argued that there was too much reliance on unconscious racial bias. Mr. Butt admitted that there were huge discrepancies in how police officers treat cases involving Indigenous victims and criminals. He went as far as to suggest that systematic changes should be made. He ended this part of his argument by saying that while all that is true, we should not be over-extending this kind of analysis to every case.

On one hand, racism is a rampant issue on the other it has nothing to do with this case. For us at the blog, this was a confusing argument, one that would definitely confuse even our own “Judicial 3000”. Alas, we move on to Mr. Butt’s third argument, he found that the verdicts his client had received were inconsistent. Fourth, he took issue with the penalty.

At some point, Mr. Butt launches into an example to draw comparisons to the events at hand, at which point one of the panel members stops him and tells him that this example is not helpful and that she was not following it. In this way, the panel seemed involved and proactive, even paying attention to small details and arguments. Panel members would chime in when they found holes in the argument or untruths. It was in those moments that this process most resembled how our “Judicial 3000” machine operates, without bias and with an eye only to finding the truth. This was impressive for mere mortals.

Are Human Tribunals Fair?

On the surface, the OCPC seems like a procedurally fair tribunal. Both sides were given the chance to speak, present their arguments and interject where their point of view was needed. As mentioned before, there was no decision made in this hearing that was available to us, but the members seemed to operate without bias, or at least without obvious and determinable bias. Further, 80% of the application and appeals that they receive is scheduled for a hearing within 90 days. Although for the modern reader who is used to the 30-minute turnaround time of the “Judicial 3000” this might seem like an eternity, 90 days was a fair window of time for complaints to be dealt with during the year 2023. Having access to timely decisions for legal problems was one of the hallmarks of a fair legal system in the 21st century.

In terms of internet and media coverage (yes the internet was by 2023 invented and widely used), while Shawn Harrison’s conduct had been widely covered by various online news sources, no information could be found online by our team about this particular hearing. The OCPC itself is mentioned in a few recent news articles chronicling recent officers who have been subject to penalties. In most of the news articles we read the decision of the hearing officer which had been appealed was upheld by the OCPC. Aside from that though, while the time frame in history we are looking at was a period in which there were many calls to hold police officers accountable for racist behaviour, not much attention is given to this administrative board that does just that. Perhaps, one explanation is that administrative remedies are of such a technical legal nature that even their existence is not known by most of the population of the state formally known as Canada.

Tribunal Members:

We at the “Bob Loblaw’s Law Blog” thought it would be interesting for the reader to know more about the members who serve on this tribunal. Lest you forget that the OCPC is not a AI program and was actually operated by human beings who made the ultimate decision. Eleven humans, all with differing backgrounds, served on this tribunal. One Associate Chair, three Vice Chairs, five members, one Executive Chair and finally one alternative Executive Chair. Members are required to comply with procedural fairness, and natural justice requirements and to act impartially. Each member is required to sign a document promising that they will uphold the requirements of fairness. Members are also bound by the OCPC Rules of Practice. The members seem to come from a background of law and some but not all were involved with their community in various ways. For example, Sean Weir, the Executive Chair, was an elected Councillor of the Town of Oakville and a director of the Hospital in the town. Member Laura Hodgson was involved with Ottawa’s Centre for Refugee Action and Tungasuvvingat Inuit. Most of the members have been in their position since 2022 or 2023 and their terms will end within the next two to three years.

But let us move on now to another hearing we were able to get our hands on. Another important and contentious topic in the history of humankind is that of control over decisions made in relation to their own well-being in terms of physical and mental health. After all, the creatures that roamed the planet Earth 300 years ago were mortals who often experienced illnesses of different kinds and had to make decisions for themselves on the recovery path they desired. The issues that arose from disagreements between the individual and a healthcare professional about the capacity of the patient to consent were dealt with by the Consent and Capacity Board (CC Board).

Consent and Capacity Board Overview

The Hearing

In the hearing that the writers at our blog were able to watch there were three members present. While they did not identify whether they were the legal expert, physician or member of the community, by the line of questioning each pursued it would be easy to make a guess. As advised by the rules of the Consent and Capacity Board we are not at liberty to share the names of the those involved. However, we can share with you that the hearing was concerning a patient in a Kingston mental health facility who had refused to take medication despite the fact that this doctor believed he was experiencing a manic episode and should be on medication. This November 6th, 2023, hearing was to determine whether the doctor would be allowed to proceed in prescribing medication to the patient without the patient’s consent. The patient himself was presented along with his legal representative, his doctor and three members of the Consent and Capacity Board. The doctor began the session by speaking about the client’s bi-polar diagnosis and mentioned previous examples of his manic behaviour. The doctor finished by asserting that his patient did not have the capacity to make decisions regarding his treatment.

For his part, the patient’s lawyer tried to make holes in the doctor’s findings by questioning whether or not the doctor had taken the necessary steps to explain to the patient his situation and his required medication. The lawyer argued that the doctor had undermined his duty to fully explain the treatment process under the false assumption that the patient himself was not capable of consenting. The members did not interject during testimonies but then proceeded to ask each side appropriate and clarifying questions. It was obvious that public safety was an important concern for the Board. A lot of the questions they asked were regarding the patient’s past public displays of violence.

Is the CC Board Procedurally Fair?

Then they began questioning the patient himself. This felt like a procedurally fair decision on the part of the tribunal members because it was obvious that the patient was frustrated by the fact that for most of the hearing, others were speaking on his behalf. He seemed happy to be able to speak for himself. Though he often went off-topic the members questioning him were very patient with him and took his words very seriously. The tribunal’s decision to have a doctor, a legal expert and a community member on the panel is also a very important step towards ensuring fairness. This way it is not the opinion and concerns of one professional group that dominates the line of questioning in each hearing.

The CC Board seems to operate in a way that is procedurally fair in terms of access to justice, for example following an involuntary admission or when a patient is found to not have the capacity for decision-making, the patient can get an advisor from the Psychiatric Patient Advocate Office. Advisors from this office help explain the legal recourse available to the patient and they will complete the paperwork for a CC Board hearing. Based on information available to us from 2023 documents and websites it is obvious that the CC Board, more than the OCPC, is concerned about treating individuals who seek guidance through their procedure with fairness. This is important because the population that they help is particularly vulnerable to exploitation and unequal treatment. On average the tribunals determine the limits of the rights of citizens on a larger scale than courts do.[1] Therefore, fairness is a much more important consideration.

In the CC Board, fairness is guaranteed by making sure that conference hearings are available, making sure that patients have access to legal representatives, and that there are interpreters available for those who need it.

How is the CC Board Perceived?

As opposed to the previous tribunal, the Consent and Capacity Board receives a lot of media attention. Based on a few articles we perused, the general population's understanding is that the Consent and Capacity Board deals with really complicated disputes. It seems that a lot of the decisions, unlike the OCPC, are appealed and it falls on the courts to affirm the Board’s decision. Specifically, an appeal of a CC Board decision can be pursued at the Superior Court of Justice based on a question of fact or law.

As mentioned before, the CC Board is very strict about keeping information confidential, so the results of the hearing are not released to the public. However, from the way that the members were interacting with the patient in the hearing we can assume that they might decide that the patient does not have the capacity to make decisions regarding their treatment. The CC Board does not always make a decision themselves. According to the Consent and Capacity Board rules of practice s20.7; if all parties wish to resolve matters by dispute resolution, then the Board can make that order upon request.

0 notes