#1909-1993

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

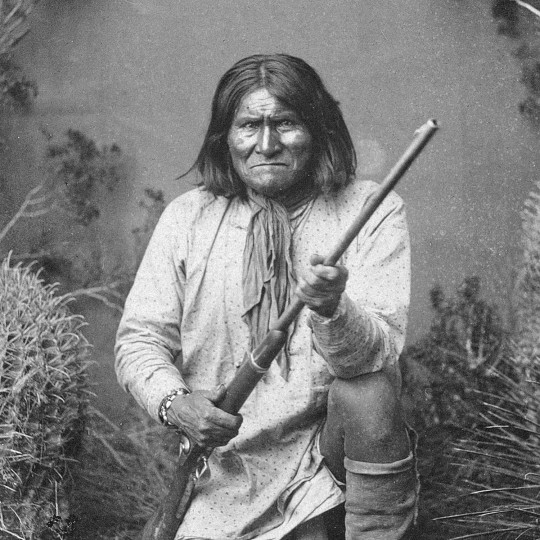

Geronimo

Geronimo (Goyahkla, l. c. 1829-1909) was a medicine man and war chief of the Bedonkohe tribe of the Chiricahua Apache nation, best known for his resistance against the encroachment of Mexican and Euro-American settlers and armed forces into Apache territory and as one of the last Native American leaders to surrender to the United States government.

During the Apache Wars (1849-1886), he allied with other leaders such as Cochise (l. c. 1805-1874) and Victorio (l. c. 1825-1880) in attacks on US forces after Apache lands became part of US territories following the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). Between c. 1850 and 1886, Geronimo led raids against villages, outposts, and cattle trains in northern Mexico and southwest US territories, often striking with relatively small bands of warriors against superior numbers and slipping away into the mountains and then back to his homelands in the region of modern-day Arizona and New Mexico.

He surrendered to US authorities three times, but when the terms of his surrender were not honored, he escaped the reservation and returned to launching raids on settlements. He was finally talked into surrendering for good by First Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood (l. 1853-1896), under the command of General Nelson A. Miles (l. 1839-1925), in 1886. None of the terms stipulated by Miles were honored, but by that time, Geronimo felt he was too old and too tired to continue running. Geronimo's surrender to Gatewood is told accurately, though with some poetic license, in the Hollywood movie Geronimo: An American Legend (1993).

Geronimo was imprisoned at Fort Pickens, Pensacola, Florida, before being moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Toward the end of his life, he became a sensation at the St. Louis World's Fair (1904) and President Theodore Roosevelt's Inaugural Parade (1905) as well as other events. Although one of the stipulations of his surrender was his return to his homelands in Arizona, he was held as a prisoner elsewhere for 23 years before dying in 1909 of pneumonia at Fort Sill.

Name & Youth

His Apache name was Goyahkla ("One Who Yawns"), and, according to some scholars, he acquired the name Geronimo during his campaigns against Mexican troops, who would appeal to Saint Jerome (San Jeronimo in Spanish) for assistance. This was possibly Saint Jerome Emiliani (l. 1486-1537), patron of orphans and abandoned children, not the better-known Saint Jerome of Stridon (l. c. 342-420), translator of the Bible into the Vulgate and patron of translators, scholars, and librarians.

Geronimo was born near Turkey Creek near the Gila River in the region now known as Arizona and New Mexico c. 1825. He was the fourth of eight children and had three brothers and four sisters. In his autobiography, Geronimo: The True Story of America's Most Ferocious Warrior (1906), dictated to S. M. Barrett, Geronimo described his youth:

When a child, my mother taught me the legends of our people; taught me of the sun and sky, the moon and stars, the clouds, and storms. She also taught me to kneel and pray to Usen for strength, health, wisdom, and protection. We never prayed against any person, but if we had aught against any individual, we ourselves took vengeance. We were taught that Usen does not care for the petty quarrels of men. My father had often told me of the brave deeds of our warriors, of the pleasures of the chase, and the glories of the warpath. With my brothers and sisters, I played about my father's home. Sometimes we played at hide-and-seek among the rocks and pines; sometimes we loitered in the shade of the cottonwood trees…When we were old enough to be of real service, we went to the field with our parents; not to play, but to toil.

(12)

After his father died of illness, his mother did not remarry, and Geronimo took her under his care. In 1846, when he was around 17 years old, he was admitted to the Council of Warriors, which meant he could now join in war parties and also marry. He married Alope of the Nedni-Chiricahua tribe, and they would later have three children. Geronimo set up a home for his family near his mother's teepee, and as he says, "we followed the traditions of our fathers and were happy. Three children came to us – children that played, loitered, and worked as I had done" (Barrett, 25). This happy time in Geronimo's life would not last long, however.

Continue reading...

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sidney Horne Shepherd.1909-1993. Male model. Oil on canvas.

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

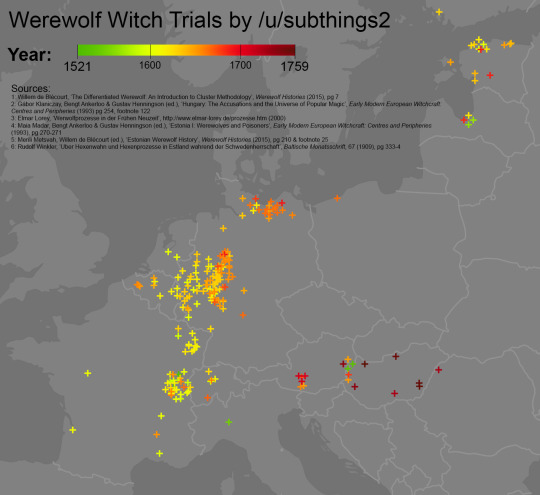

Map of werewolf witch trials

by subthings2

Mapping the location of 223 witch trials that included accusations of turning into a wolf, mostly based on Lorey's online list (just under 200 listed). Blécourt gives a few corrections to Lorey's list, Klaniczay has 13 Hungarian trials, and Madar, Metsvah and Winkler collectively give 14 Estonian trials; Metsvah says there are 30 recorded in Estonia in total, but data on the rest weren't provided. When a location has multiple trials, the crosses form a circle around the city so as to not overlap - this is most obvious for Tallinn, Riga, and Sopron.

The initial point was to visualise how the trials spread over time, but what it also makes really obvious is how tightly clustered most of them are - this matches how regional the witch trials in general were, but also that beliefs in werewolves weren't evenly spread across Europe; hence the lack of anything in Great Britain, Basque Country, but weirdly also Scandinavia where southern Sweden is known for having a decent number of werewolves in its folklore.

Finally, after going through all of Lorey's descriptions, there's a few that stood out that I wanted to share (machine translated from German):

1619 Tonnis Steven von Grevenstein, shepherd in Kallenhardt (Electoral Cologne Office of Rüthen). “Out of pain and unbearable torment, I had to say that I was a magician and a Wehrwolf, but God in heaven knows that everything is a lie and I have never seen a devil in my life.”

1652 Wilhelm Scheffern, shepherd from Metterich (di Metternich near Münstermaifeld, Kurtrier). One of the reasons he was talked about was because - in contrast to his successors - there were never any losses due to wolf attacks during his time as a shepherd. "It is entirely believed that the defendant could turn himself into a werewolf" (6th count) and "that he ... once made himself invisible in the field" (point 15). However, previously in points 2 and 3 "that his "The father was burned because of the vice" and "that the defendant's sisters were burned years ago because of the vice of magic." (Court verdict not received; according to Krämer, however, probably executed.)

1661 Cuno Jung, a shepherd from Westerburg, had not defended himself strongly enough against being called a werewolf. Because his parents were already under suspicion and his sister had been executed as a witch, he spoke out against the witchcraft trials. He also refused to take part in an execution as a lay judge. He once even tried to buy his way out as an observer at a witch trial. Executed in Westerburg.

there's also the WAR WLF of Lemgo, featuring this funky little guy that's also had several people write about the rather unfunky little trial

the single case aaaall the way up in Finland is Erkki Juhonpoika

Sources:

Willem de Blécourt, ‘The Differentiated Werewolf: An Introduction to Cluster Methodology’, Werewolf Histories (2015), pg 7

Gábor Klaniczay, Bengt Ankerloo & Gustav Henningson (ed.), ‘Hungary: The Accusations and the Universe of Popular Magic’, Early Modern European Witchcraft: Centres and Peripheries (1993) pg 254, footnote 122

Elmar Lorey, ‘Werwolfprozesse in der Frühen Neuzeit’, http://www.elmar-lorey.de/prozesse.htm (2000)

Maia Madar, Bengt Ankerloo & Gustav Henningson (ed.), ‘Estonia I: Werewolves and Poisoners’, Early Modern European Witchcraft: Centres and Peripheries (1993), pg 270-271

Merili Metsvah, Willem de Blécourt (ed.), ‘Estonian Werewolf History’, Werewolf Histories (2015), pg 210 & footnote 25

Rudolf Winkler, ‘Uber Hexenwahn und Hexenprozesse in Estland wahrend der Schwedenherrschaft’, Baltische Monatsschrift, 67 (1909), pg 333-4

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

Young girl, making tortillas, Mexico, ca. 1947 - by Fritz Henle (1909 - 1993), German/American

338 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tattoo Art by Samuel Steward Samuel Steward (July 23, 1909 – December 31, 1993) was a university professor who left teaching to became a tattoo artist and pornographer. He was friends with people like Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Alfred Kinsey, Paul Cadmus, George Platt Lynes , and other important LGBT writers and artist. In the 1960's, besides writing pornography under the name Phil Andros, he was the official tattoo artist for the Hells Angels. Throughout his life, he kept extensive secret diaries, journals and statistics of his sex life. In 1949 he met Alfred Kinsey and became an unofficial collaborator with Kinsey's Institute for Sex Research. He wrote several non pornographic novels, a book of poetry, and several memoirs focusing on different aspects of his life. There are also several biographies of his life, the most well known being Secret Historian: The Life and Times of Samuel Steward, Professor, Tattoo Artist, and Sexual Renegade.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fritz Henle (June 9, 1909 – January 31, 1993), Holland Museum, 1955.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sam Steward (1909-1993) - scratchboard.

Sam Steward, born Samuel Morris Steward (1909 – 1993), also known as Phil Andros, or Phil Sparrow. The talented and charming Samuel M. Steward began his career as a novelist, professor of English at Chicago’s DePaul and other universities, and an editor of the World Book Encyclopedia. His letters to Gertrude Stein in the early ’30s led to a close friendship with her and Alice B. Toklas. “Sammy” periodically visited them in France, shared artistic insights, and befriended many in their circle. A fine draughtsman, he was also an American tattoo artist.

(Don Bryson publication)

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ernst A. Heiniger (Swiss, 1909-1993) Bahnhofplatz, Zurich. 1933 © Fotostiftung Schweiz

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Klamath Falls, OR (No. 4)

During World War II, a Japanese-American internment camp, the Tule Lake War Relocation Center, was located in nearby Newell, California, and a satellite of the Camp White, Oregon, POW camp was located just on the Oregon–California border near the town of Tulelake, California. In May 1945, about 30 miles (48 km) east of Klamath Falls, (near Bly, Oregon) a Japanese Fu-Go balloon bomb killed a woman and five children on a church outing. This is said to be the only Japanese-inflicted casualty on the US mainland during the war.

Timber harvesting through the use of railroad was extensive in Klamath County for the first few decades of the 20th century. With the arrival of the Southern Pacific Transportation Company in 1909, Klamath Falls grew quickly from a few hundred to several thousand. Dozens of lumber mills cut fir and pine lumber, and the industry flourished until the late 1980s when the northern spotted owl and other endangered species were driving forces in changing western forest policy.

On September 20, 1993, a series of earthquakes struck near Klamath Falls. Many downtown buildings, including the county courthouse and the former Sacred Heart Academy and Convent, were damaged or destroyed, and two people were killed.

Source: Wikipedia

#Lake Ewauna#Klamath Falls#wildlife#fauna#flora#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#landscape#nature#USA#summer 2023#Oregon#Pacific Northwest#cityscape#architecture#lake shore#Klamath County#Lake Ewauna Nature Trail#Stukel Mountain#reservoir

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nino Carbe (1909-1993), 'The Little Mermaid', ''Heavy Metal'', April 1980

#nino carbe#italian-american artists#heavy metal magazine#heavy metal#the little mermaid#hans christian andersen#mermaids

347 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sono donna anche oggi, anche se non è l'8 marzo e nessuno mi porta una mimosa.

Sono donna anche oggi, che non ho nessuna serata in discoteca con uomini nudi che dovrebbero farmi divertire ballando e invece, poveretti, mi fanno solo pena...loro e chi ci va quel maledetto 8 marzo.

Sono donna ogni giorno, quando mi alzo e ho la forza di dire ''tocca a me'', senza nessuno che mi impone qualcosa o senza obblighi legati ad ormai morte tradizioni ed usanze.

Mi piace essere donna, non sono una femminista sfegatata che difende ad ogni costo e ad oltranza il mio genere, perché le stronzate le facciamo anche noi e non siamo sante, almeno io aureole in testa non ne vedo proprio a nessuno, ma mi piace la mattina pettinarmi i capelli, mettere il mascara e perdere quegli intramontabili venti minuti davanti ad un armadio, sempre pieno di cose che a me in quel preciso istante non piaceranno.

Mi piace essere donna, perché in quel lontano 1907 e poi 1909 e infine in quel 1910 qualcuno finalmente capì che anche io ho un pensiero, e posso renderlo libero come ogni altro maschietto del tempo stava facendo; mi piace essere donna perché mi piace esser come tutti gli altri, in fondo cosa cambia?

Al posto di averle in basso due palle, le ho appiccicate sul petto.

Non voglio dire frasi e luoghi comuni come "grazie a noi avete i vostri figli, uomini", perché a riguardo nessuno ha un merito superiore, perché se qualcuno ci ha creati entrambi siamo complementari e non subordinati.

Se qualcuno ha lottato per una parità di diritti, se esiste questa benedettissima uguaglianza voglio lottare e conquistarla ogni giorno, voglio esser donna anche quando le cose si metton male e c'è da rimboccarsi le maniche, voglio esser donna quando c'è da lavorare anche se non si tratta di gonna sexy ma di una tuta grigia e sporca di nero a fine giornata, voglio essere donna e voglio combattere tenacemente in una società "evoluta" e dinamica, in una società dal libero pensiero e dalla mentalità aperta che ancora boicotta l'espressione di ogni genere e di tutti i generi.

"Dichiarazione universale dei diritti umani" e "Dichiarazione dei diritti umani di Vienna", 1945 prima e 1993 poi... vi dice nulla? A me sì, e dice che se io voglio studiare, laurearmi e lavorare in un'azienda e starne a capo, posso farlo perché ho la stessa brama, grinta e forza che avrebbe il mio collega dalle palle attaccate in basso che il colloquio non lo ha superato. Mi dice anche che la mia mansione non è esclusivamente accudire i figli e sfornare lasagne e torte al cioccolato per il mio amato maritino che, povero, al rientro dal suo faticoso lavoro deve trovare qualcosa in tavola e il figlio che già dorme, pulito e profumato. No. Non sono una serva, una schiava, un'allevatrice e macchina di procreazione. Gli antichi romani si sono estinti e siamo nel ventunesimo secolo.

Io sono donna e ho diritto di vivere, io sono donna e ho diritto, io sono donna, io sono. Io. Quell' "io" promotore di soggettività, indipendenza ed esistenza. Non esiste moralmente, eticamente, metaforicamente (chi più ne ha, più ne metta) UOMO e DONNA, esiste io. E quest'ultimo devo ogni giorno, ora, minuto confermarlo senza che altri io prendano il sopravvento.

Io sono donna anche oggi, che non è l'8 marzo, ma in ogni attimo della mia esistenza pretendo reciproco rispetto e fedeltà, detengo la mia dignità e manipolo senza vincoli i fili di un burattino chiamato Vita.

Silvana Blasco

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joe DeRita (July 12, 1909 – July 3, 1993)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marianne Straub

Textile designer Marianne Straub was born in 1909 in Amriswil, Switzerland. Straub moved to Britain in the 1930s, and became one of the country's leading textile designers from the 1940s to the 1960s. In 1964, she designed the moquette for London tubes and buses that remained in use until 2000. Straub's fabrics were also used in airplanes, hospitals, ships, and government buildings. She was also an accomplished art educator who taught at the Central School of Art, Hornsey College of Art, and the Royal College of Art. In 1972, Straub was named a Royal Designer for Industry, the highest honor for designers in the UK. In 1993, she won the Sir Misha Black Medal.

Marianne Straub died in 1994 at the age of 85.

Image: DCA-30-1-POR-S-87-1. Design Council Archive, University of Brighton Design Archives

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

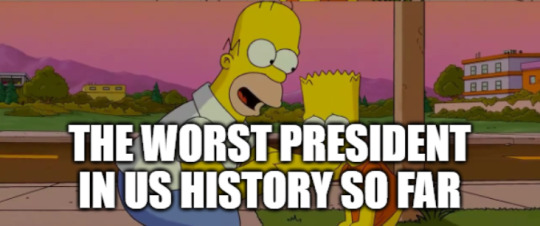

Who's the Worst President in the History of the United States?

What's going on? You know how these brackets work! I've matched up all 45 presidents of the United States of America by a random generator, and I'll be making 1v1 polls for each matchup. The loser gets eliminated, the winner moves on to the next matchup. The ultimate winner is crowned the WORST PRESIDENT.

What are the rules? 1. Vote for the one you DISLIKE. You want people you like to lose and be eliminated. 2. Submitting reasons to vote will be published! Help convince others to your side--either to vote for someone you hate or leave someone you like alone! Propaganda submitted as asks will be tagged with the president, or you can reply directly on the matchup posts. 3. Your reasons for disliking a president are your own. If you just hate their haircut, fair enough. However, I recommend you look at their policies, values, and actions in things like supporting slavery of Native American genocide, limiting social and economic mobility, contributing to the prison-industrial complex, US imperialism and neo-imperialism, and more! 3b. It is acceptable to consider reasons before/after their tenure as president. 3c. Because the above will be in basically every post, they will not be tagged. If they are triggers for you, I recommend you simply block this block. No hard feelings, I promise. 4. If you submit propaganda, make sure it's true. There are lots of random myths about presidents floating around. I'll do my best to fact-check, but do a quick Google before you hit submit, please!

Who are the contestants? All 45 presidents of the United States of America. Here's the full list!

George Washington (1789-1797)

John Adams (1797-1801)

Thomas Jefferson (1801-1809)

James Madison (1809-1817)

James Monroe (1817-1825)

John Quincy Adams (1825-1829)

Andrew Jackson (1829-1832)

Martin Van Buren (1837-1841)

William Henry Harrison (1841)

John Tyler (1841-1845)

James K. Polk (1845-1849)

Zachary Taylor (1849-1850)

Millard Fillmore (1850-1853)

Franklin Pierce (1853-1857)

James Buchanan (1857-1861)

Abraham Lincoln (1861-1865)

Andrew Johnson (1865-1869)

Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1877)

Rutherford B. Hayes (1877-1881)

James A. Garfield (1881)

Chester A. Arthur (1881-1885)

Gover Cleveland (1885-1889; 1893-1897)

Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893)

William McKinley (1897-1901)

Theodore 'Teddy' Roosevelt (1901-1909)

William Howard Taft (1909-1913)

Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921)

Warren G. Harding (1921-1923)

Calvin Coolidge (1923-1929)

Herbert Hoover (1929-1933)

Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-1945)

Harry S. Truman (1945-1953)

Dwight D. Eisenhower (1952-1961)

John F. Kennedy (1961-1963)

Lyndon B. Johnson (1963-1969)

Richard Nixon (1969-1974)

Gerald Ford (1974-1977)

Jimmy Carter (1977-1981)

Ronald Reagan (1981-1989)

George H. W. Bush (1989-1993)

Bill Clinton (1993-2001)

George W. Bush (2001-2009)

Barack Obama (2009-2017)

Donald Trump (2017-2021; 2025 President elect)

Joe Biden (2021-2025)

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Little boy going to the tavern for his father's wine, Sardinia - by Fritz Henle (1909 - 1993), German/American

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vittorio Reggianini 1800s, Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret 1882

Frédéric Soulacroix, Bernhard Osterman 1870–1938

józsef arpád koppay 1903, frederic leighton 1830-1896

Artemisia Gentileschi 1623-1625, Sophie Anderson 1823–1903

horst kristner 2015, micheal leonard 1993

Vlaho Bukovac 1909, lothar von seeback 1898

louis anquentin 1886-1887, halyna mazepa 1946

evgeny sedukhin, Andrey Mikhailovich Ponomarev 1960s

scheherazade 1921, willem gerard hofker 1948

albert besnard, clement serneels 1939

Georges Lepape 1912, viktor zaretsky 1989

Makinti Napanangka 2001, Jean-Michel Basquiat 1981

james gleeson 1984 dino, buzzati 1967

#comp post#this took forever lol#please notice that this is not in chronological order! theres a 2015 up with the 1800s pieces. its just thematically ordered#well#not thematic#whatever

33 notes

·

View notes