#1832 digression

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Lamarque!

And now we learn why he was well-liked. His defense of liberty would appeal to republicans like Les Amis; his work under Napoleon would appeal to Bonapartists. Bonapartists were a very large group, too, characterized as the “mob” or “masses” here. Many of the Bonapartists we’ve met have been from varied backgrounds, too! Just think of Fauchelevent and Marius. We see this through Les Amis and our peek into the Faubourg Saint-Antoine with republicans, too, so all in all, he was a popular figure.

The protesters are a diverse group, too, including students, activists, refugees, striking workers, and so on. They’re also organized quickly. Having seen how these groups work with Les Amis and the July Revolution digression, it’s not shocking that their constant thought of the possibility of violent protest – combined with their effective communication and networking in secret – would leave them prepared for this kind of situation.

This chapter feels very tense, giving us a sense of what those there experienced. That mounting pressure is really palpable.

That tension is heightened by the ambiguity. Even in this historical style, Hugo doesn’t claim definitive knowledge of what happened. He offers possibilities based on what’s said, but we don’t know exactly what (or who) started the protests. What’s significant is that they started, and that we know why.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Mis Musical: they were schoolboys, never held a gun...no one ever told them a summer day could kill...they were so naiive to believe their revolution could succeed. This is why they call em revolutions, they keep spinning and nothing changes...rebelling against state power is impossible... The Revolution of 1830 AKA The July Revolution AKA "The Second French Revolution", a successful rebellion that occurred in Paris literally only two years before the June Rebellion (but because of moderate politicians ended with a new more progressive King being installed to replace the ultra-conservative King, instead of the total elimination of monarchy), a rebellion which Victor Hugo writes an entire digression about in the novel when discussing how it influences 1832, and which Les Amis would've taken some part in:

271 notes

·

View notes

Text

This current poll is almost finished, with less than a day left of the whole thing! I need ideas for the next one, to start one back up as soon as possible. They can be tournaments or individual polls. My current ones:

Tournaments:

-best ship (this is gonna be evil lmao)

-Best song

-Best version

-Best minor character (idk what is considered minor but I'd figure that out)

-I had another idea if how to do the best character one, in which I pit every single character I did against every single other person,then figure out their average percentage and put them in order. I'm curious if the results would change. It would be a bit repetitive so I'll either wait for a while to do that or have it going on at the same time as new ideas.

Shorter ones:

-Best Ami

-Kiss, Marry, Kill with each character

-Best time period (i.e. 1815, 1823, 1832...)

-Best digression

Feel free to suggest more or comment which ones you'd be most interested in! 😁 I will add the ideas I'm definitely using to the pinned post, so you all can see future ones.

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello there! today i came across a claim that sort of baffled me. someone said that they believed the historical norse heathens viewed their own myths literally. i was under the impression that the vast majority of sources we have are christian sources, so it seems pretty hard to back that up. is there any actual basis for this claim? thanks in advance for your time!

Sorry for the delay, I've been real busy lately and haven't been home much. Even after making you wait I'm still going to give a copout answer.

I think the most basic actual answer is that it's doubtful that someone has a strong basis to make that claim, and the same would probably go for someone claiming they didn't take things literally. I think we just don't know, and most likely, it was mixed-up bits of both literal and non-literal belief, and which parts were literal and which parts weren't varied from person to person. We have no reason so suppose that there was any compulsion to believe things in any particular way.

About Christians being the interlocutors of a lot of mythology, this is really a whole separate question. On one hand there's the question of whether they took their myths literally, and on the other is entirely different question about whether or not we can know what those myths were. Source criticism in Norse mythology is a pretty complicated topic but the academic consensus is definitely that there are things we can know for sure about Norse myth, and a lot more that we can make arguments for. For instance the myth of Thor fishing for Miðgarðsormr is attested many times, not only by Snorri but by pagan skálds and in art. Myths of the Pagan North by Christopher Abram is a good work about source criticism in Norse mythology.

Though this raises another point, because the myth of Thor fishing is not always the same. Just like how we have a myth of Thor's hammer being made by dwarves, and a reference to a different myth where it came out of the sea. Most likely, medieval Norse people were encountering contradictory information in different performances of myth all the time. So while that leaves room for at least some literal belief, it couldn't be a rigid, all-encompassing systematic treatment of all myth as literal. We have good reason to believe they changed myths on purpose and that it wasn't just memory errors.

I know you're really asking whether this one person has any grounds for their statement, and I've already answered that I don't think they do. But this is an interesting thought so I'm going to keep poking at it. I'm not sure that I'm really prepared to discuss this properly, but my feeling is that this is somehow the wrong question. I don't know how to explain this with reference to myth, so I'm going to make a digression, and hope that you get the vibe of what I'm getting at by analogy. Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917) described animism in terms of beliefs, "belief in spiritual beings," i.e. a belief that everything (or at least many things) has a soul or spirit. But this is entirely contradicted by later anthropology. Here's an except from Pantheologies by Mary Jane Rubenstein, p. 93:

their animacy is not a matter of belief but rather of relation; to affirm that this tree, that river, or the-bear-looking-at-me is a person is to affirm its capacity to interact with me—and mine with it. As Tim Ingold phrases the matter, “we are dealing here not with a way of believing about the world, but with a condition of living in it.”

In other words, "belief" doesn't even really play into it, whether or not you "believe" in the bear staring you down is nonsensical, and if you can be in relation with a tree then the same goes for that relationality; "believing" in it is totally irrelevant or at least secondary. Myths are of course very different and we can't do a direct comparison here, but I have a feeling that the discussion of literal versus nonliteral would be just as secondary to whatever kind of value the myths had.

One last thing I want to point out is that they obviously had the capacity to interpret things through allegory and metaphor because they did that frequently. This is most obvious in dream interpretations in the sagas. Those dreams usually convey true, prophetic information, but it has to be interpreted by wise people who are skilled at symbolic interpretation. I they ever did this with myths, I'm not aware of any trace they left of that, but we can at least be sure that there was nothing about the medieval Norse mind that confined it to literalism.

For multiple reasons this is not an actual answer but it's basically obligatory to mention that some sagas, especially legendary or chivalric sagas, were referred to in Old Norse as lygisögur, literally 'lie-sagas' (though not pejoratively and probably best translated just as 'fictional sagas'). We know this mostly because Sverrir Sigurðsson was a big fan of lygisögur. But this comes from way too late a date to be useful for your question.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

If the sewers are one of the circles of hell, they have their demons. And these demons are the police dispatched to hunt down the surviving insurrectionists. Fortunately for Jean Valjean, their efforts lack thoroughness. Even the lantern failed to expose him in the darkness, as they hurried toward Saint-Merry with its larger barricade.

Adding to the portrayal from the previous chapter, Hugo reminds us that Jean Valjean's remarkable resourcefulness wasn't an easy feat, considering he teetered on the brink of exhaustion due to 'lack of sleep and food.' The sudden emergence of the police behind him must have been extremely stressful, likely triggering flashbacks of a previous instance when the police chased him with Cosette before he reached the convent.

I love how Hugo chose to digress and explain the meaning of the word 'bousingot' as it was in 1832. It’s just so like him!

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

prompt list

If you want to know what is on the list before you get a bingo card, here is what I would currently feed the bingo card generator. Characters are about a quarter of the list, I tried to choose words and tropes and au tags etc that would work for as many people as possible within brick fandom and have very few non-gen prompts, but it probably leans towards my preferences heavily still.

-

canon compliant, technically canon compliant, canon divergence, missing scene, crossover, fix-it, time travel / time loop, magic, hijinks, angst, fluff, character death, animals, pov outsider, ghosts, bodyswap, 5 + 1, epistolary, secret identity, mistaken identity, alternate universe, different era, hurt/comfort, character study, action / adventure, trope reversal, happy ending, humour, fake relationship, marriage, friendship, siblings, family, misunderstandings, rarepair, rivalry, developing relationship, established relationship, strangers, Valjean, Cosette, Fantine, Javert, Éponine, Gavroche, Marius, Les Amis de l’ABC, Patron Minette, Montparnasse, Thénardier, Madame Thénardier, Azelma, Favourite, Tholomyes, Myriel, Gillenormand, Enjolras, Combeferre, Prouvaire, Feuilly, Courfeyrac, Bahorel, Lesgle, Joly, Grantaire, Mabeuf, the momes, Baptistine, the nuns / the convent students, Simplice, Fauchelevent, Theodule, Mlle Gillenormand, Georges Pontmercy, the gamins, the grisettes, volume i, volume ii, volume iii, volume iv, volume v, digression, the year 1817, 1832, Montfermeil, Montreuil-sur-mer, Paris, the Gorbeau house, the Rue Plumet, the convent, Digne, the Corinthe, minor character, one-off character, character seldom fanworked, character you have never fanworked, pass the Bechdel Test, ship you have never fanworked, trope you have never fanworked, kiss, first, last, hands, blood, romanticism, symbolism, nature, garden, red, blue, light, dark, window, door, fire, water, science, secrets, truth, food / cooking, sleep, illness, music, beauty, horror, future, past, time, mystery, best laid plans, home, travel, curiosity, argument, fight, party, three wishes, memories, weather

0 notes

Text

should post this to my simblr really. not gonna. mcoc. post it here for posterity's sake.

Dr. Apollina Soteira. 1 Doctorate of Psychology in the year 1832 on SMP-Earth-#9,331,004-1. Therapist & Field Medic [Dr. Soteira gained an M.D. at some unknown point between leaving her home server and joining the war effort] for the Anarchist Revolution* helmed by Maximilien Astor, c. 219,999-220,000 on SMP-Tyranny-#456,123-1 for 3 months until summary execution by revolutionary leader and then-husband Maximilien Astor for conspiracy to betray faction ideals. [Note: voted against killing the then 5 year old son of the Emperor by standing between the child and Astor's gun. Cause of death was an iron bullet to the brain, through the right eye.].

[*Entitled a revolution, Maximilien Astor's faction was rather more an Anarchist coup, as Mr. Astor had once been high-ranking in the military of his nation. Consider him, if you will, akin to a fusion of Robespierre and Napoleon in action, but with rather more Militant Anarchist motivations - and outcomes.]

This picture was taken roughly 3 personally-chronological years post-second-mortem**, on SMP-Masquerade-#100-2.

[**Dr. Soteira lives her current existence as a vampire, and has done so since the year 1835 on SMP-Earth-#9,331,004-1, whence she was turned by a man known only as The Count in all historical records.]

The method of capture, and reason for visual distortion, is unknown, as since all current photographic technology requires iron, and Dr. Soteira's existence is generally incompatible with the metal, being supernatural in nature***.

[***Common understanding of the Supernatural indicates iron as deadly to fae beings solely, whilst others - namely, as is relevant, vampires - have aversions to silver. Contrary to this notion, it appears Dr. Soteira's home Server's brand of Supernatural existence consolidated all weaknesses to iron, thus Dr. Soteira is capable of things such as seeing herself in mirrors made of any metal other than iron, but incapable of things such as wearing standard defensive gear - iron armour and shields are deadlier than simply getting shot would be [as most use flint for their arrows or firework rockets, not iron bullets - guns are a rare commodity exclusive to certain Servers. It is likely her home Server had no such thing, in fact - but I digress]. One must research the occult of her home World to understand the eccentric intricacies and rules of her unnatural status, as it may be in direct contrast to the laws and guidelines one may have in their own Server, and such an oversight could be deadly if one were to find themselves in direct conflict with a Vampire of her ilk.]

Also. Bc why not. Have the raw screencap;

bbg <3

#hmmmm#clrmc#sure. anyway.#yeah me rambling abt my original blorbos because nobody sent me the oc ask game thing :(#also im playing fallen london right now and my bbg is the pc so <3 made me think of her. made me want to exposit

1 note

·

View note

Text

#also btw guys based on the placement of the dominoes chapter that scene would have happened probably between 1828 and 1830#(since Hugo doesn't discuss the 1830 July revolt until after and also Feb 1832 doesn't begin until after that even)#so it's not like this was a scene mentioned because it had some great bearing on the June Rebellion#it's mentioned to illustrate the Amis and the work they were alreadt doing and also the relationships and attitudes (@shitpostingfromthebarricade)

Okay so "when does the dominoes scene take place" is a Question, because the only time cue in 4.1.6 itself is "at about this period." But I always took "around this period" to be the place that the narrative had gotten up to the last time we had a time check, and that's April 1832.

4.14, towards the end: "Hardly twenty months had rolled by since the July Revolution; the year 1832 had opened with a menacing atmosphere," and then discusses events of early 1832.

4.1.5 begins "Toward the end of April everything was worse," describes the ferment which has been building since 1830, and describes events in Saint-Antoine specifically in April 1832; it gives the date in connection with two events (one of the coded papers found and the mouchard claiming to be a Babeuvist).

And then 4.1.6, "Enjolras and His Lieutenants," starts "around this period"--so, April 1832.

It is confusing, because 4.1.6 is the last chapter of "A Few Pages of History," which is the 1830 digression, but that digression starts in 1830 and then talks about the revolutionary activity that followed it.

And it's even more confusing because then the narrative jumps backwards from here to fill in what Marius has been doing since 1830--but we are jumping back; all of the stuff with the jailbreak and Eponine finding Cosette's address for Marius is filling in the personal plot (the Idyll of the Rue Plumet) and taking us back where we left off in the political one (the Epic of the Rue Saint-Denis).

inspired by @hecstia ‘s gorgeous jily post :)

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Riot and insurrection are defined by minority vs majority, with insurrection being a just movement by the majority to maintain its democratic power and rioting being a minority using violence against the people (the exception being colonialism because Hugo believed in “civilizing” missions, as illustrated by his remarks on Columbus). Through this link, they’re also defined by their tie to progress: insurrection is part of progress and is good, and rioting looks to the past and is therefore bad.

Hugo’s comments on writing under tyranny are fascinating in the context of Napoleon III. Hugo was exiled, but he was still conscious of how censorship could affect his work in France. The dense prose mentioned, then, could be this novel! Its themes are concealed, to an extent, by its length and its digressions. Hugo outright tells us his opinions (like he’s doing now), but after reading so much, it can be difficult to keep track of without a very close reading (which is made difficult by length, too – even though the goal of these posts has been to close-read each chapter, there will always be chapters that I understand better and others that are incomprehensible. A censor needing to read this quickly would be very lost!). Hugo’s prose doesn’t seem concise at all, but perhaps he felt that it was appropriate for the breadth of what he covered, and that he felt he learned to better articulate himself with this consciousness.

(Or maybe Hugo wants a republic so he can digress freely. Maybe digressions are democracy)

Despotism being the same under a “genius” feels like a jab at Napoleon I, too, making it an even harsher critique of the less respected (by Hugo) Napoleon III! And it’s also a return to Louis Philippe, who – while a good person – still suffers from the flaw of being a king in a France that doesn’t want one.

And he has a point that suffrage is wonderful because it offers an alternative to both insurrection and rioting! If the people have a non-violent and legitimate way of expressing their opinions, then they become less necessary. Hugo’s dream of them disappearing is a lot – protest is seen as another right alongside suffrage – but it’s a nice ideal in that it imagines a democracy that functions perfectly and thus only needs the vote to decide well.

And unfortunately, Hugo’s right about the reluctance to distinguish between the two by those in power. We’re back to animal symbolism, but this time, it’s between an animal and a person. The “dog” expected to serve the person is beaten for disobedience, leaving no alternative but to transform into a ferocious lion capable of resisting.

I love that Hugo basically says “June 1832 was insurrection, but there’s a good chance I’ll forget and say riot in the future; just know I don’t mean that politically.” It’s almost a form of self-awareness over how many words he uses to describe most things!

He’s making a claim to historical accuracy, too, and one grounded in the perspective of the protesters. The judicial records he mentions would have been from their trials and, therefore, from the point of view of a state threatened by them. Hugo’s fictionalized account continues to give a voice to those neglected by those narratives.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 5.1.1 The Charybdis of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine and the Scylla of the Faubourg du Temple

Wow, Hugo. Fuck the fuck off.

We start off book five with.. I was going to say it’s the worst chapter in this book, but it’s been a while since the Argot digression so I’m having trouble saying that for certain.

It’s bad, though. It’s unbelievably bad.

Hugo, in a bout of pretty terrifying cognitive dissonance, explains, after all his talk about the necessity of revolt and revolution, why the revolt of 1848 was uniquely illegitimate and bad. Worse, he does it while praising the heroism of the poor stupid workers who had their hearts in the right place but were too deluded to realize they were standing against Progress and the True Revolution or whatever. It’s all very love the sinner hate the sin and how you have to admire and pity the revolting rabble for their spirit even as it’s obviously necessary to gun them down.

Because Hugo, of course, was on the government’s side in this fight. Rose’s footnote glosses breezily over what he actually did in it, but my understanding is that he was supposed to go and mediate with the rebels, but instead he gunned them down by the hundreds on his own initiative.

And yet, the only use of “I” in this chapter on the 1848 barricades is

There were a few corpses here and there, and pools of blood on the pavement. I remember a white butterfly flying back and forth in the street. Summer does not abdicate.

He’s rewriting himself as a mere observer in 1848, the way he legitimately was in 1832. Maybe he wishes he had been; I’d kind of hope so.

His politics evolved in the intervening years, but he never seems to have been able to say the workers in 1848 were in the right and he was in the wrong.

And, let’s be clear: the workers were in the right. They were responding to policies of the new republic that were designed to unemploy them and drive them out of Paris, because the reigning bourgeois liberals wanted to shut the working class left out of politics permanently. This all took place, of course, five months after the working class left fought on the barricades that put the bourgeois liberals into power.

The workers knew perfectly well what they were fighting for. It was their own survival against a hostile government.

But Hugo is grimly determined not to acknowledge any of that, so we get such shitty, demeaning, infantilizing, horrifyingly condescending takes as these:

Those are mournful days; for there is always a certain amount of right even in this madness, there is suicide in this duel, and these words, intended for insults-beggars, rabble, ochlocracy, populace-indicate, alas, rather the fault of those who reign than the fault of those who suffer; rather the fault of the privileged than the fault of the outcasts .

and

The exasperations of this multitude that suffers and bleeds, its misconstrued violences against the principles that are its life, its forcible resistance to the law, are popular coups d'etat and must be repressed. The man of integrity devotes himself to it, and out of the very love for that multitude, he battles against it. But how excusable he feels it, even while opposing it; how he venerates it, even while resisting it! It is one of those rare moments when, in doing what we have to do, we feel something that disconcerts and almost dissuades from going further; we persist, we are compelled to; but the conscience, though satisfied, is sad, and the performance of the duty is marred by a pang.

June 1848 was, let us hasten to say, a thing apart, and almost impossible to classify in the philosophy of history. All that we have just said must be set aside when we consider that extraordinary emeute in which was felt the sacred anxiety of labor demanding its rights. It had to be put down, that was duty, for it was attacking the Republic. But what basically was June 1848? A revolt of the people against itself.

and

it attacked in the name of the revolution--what? The revolution.

Fuck. This. Guy.

And it’s just. At odds with the entire rest of his own book? It feels like a Hugo who hasn’t READ the rest of this book? These barricades are a whole lot like the barricades we’ve been praising! Only these are Wrong, Deluded barricades, so they’re described as scary.

They weren’t deluded, they just disagreed with Hugo. For very good reasons.

Hugo’s truly horrifying “I had to do this for your own good” tone is making me think back to the other murdery revelations of this readthrough--the idea that Marius could have murdered Cosette if things had worked out differently.

And I can’t help but think Hugo deliberately spared his self-insert not only this experience of having fought on the wrong side of the barricade, but also the experience of murdering the republic herself. Like Hugo, Marius was profoundly capable of it--but unlike Hugo, fate or fatality or Providence intervened and stopped him.

And the bizarre and shocking part of that is--if it’s true, then some part of Hugo knows he was in the wrong, even as he claims here over and over that he wasn’t.

If this really is how these parts of the story fit together, some part of him knows that he murdered the Republic.

#brickclub#lm 5.1.1#really starting the new tome out with a bang huh#cw: murder#cw: domestic violence#cw: war crimes

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 4.10.1, “A Superficial Analysis,” and 4.10.2., “The Root of the Matter”

This book, “The Fifth of June 1832,” constitutes a third digression for Volume IV--though, as we move into the barricade sections, it’s hard to tell whether this is a digression, or just background. The barricade brings everything together and levels distinctions--including between story and digression.

4.10.1 lays out the simplistic, bourgeois dismissal of riot against which 4.10.2 will argue. @everyonewasabird‘s writeup sums it up--these are the same centrist arguments against (effective) protest that people are still making today, and they were bullshit then, too.

The “school of politics, known as the happy medium” isn’t just a dig at centrists; the phrase in the original is juste milieu, which was the actual doctrine of the Doctrinaires. The idea that there could be a happy medium between revolution and authority was the actual political philosophy of the ruling elite of the July Monarchy.

4.10.2 lays out the difference between Riot (never justified even when well-meant) and Insurrection (always justified, always noble, even when unsuccessful) and... yikes. This chapter covers a lot of ground and most of it is not good. There’s a lot of straightforward cheering for colonialism in this chapter and a lot of stanning of Great Men, even when tyrannical, that simply isn’t reconcilable with the ideas put forth in Waterloo.

(There is also a long discursus on writing under censorship, which includes “Historical repression produces conciseness in the historian. The granite solidity of some celebrated prose is nothing other than a density created by the tyrant’s oppression.” On the one hand, it’s a good observation and it’s true of quite a lot of this book. On the other hand, if this is Hugo at his most concise...)

But under everything, the basic idea--that while rebellion against unjust tyranny is a duty, rebellion against the collective sovereignty of The People is mere riot, no matter who the rioters are; and that these are definitely different things which you can totally tell apart, always (unless of course you’re a bourgeois in which case they both look like sedition)-- that’s the cognitive dissonance of 1848. The valorization of 1830 to undercut 1832, which he decries--correctly--in 4.10.1 as bourgeois bafflegab is... exactly what he’s setting up here, and what he’ll use in a few chapters to valorize the February Days of 1848 at the expense of the June Days.

And in the midst of all of this self-protective flailing, the one thing that rings out as totally sincere is also the most heartbreaking:

All that belongs in the past; the future is different. What is wonderful about universal suffrage is that it nips riot in the bud and, by giving the vote to insurrection, disarms it. The disappearance of war, war on the streets as well as on the frontiers, is the inevitable progression. Whatever today might be, tomorrow brings peace.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I went into a little more detail on the pros and cons of various translations!

The other pieces of advice I would give a first-time reader:

1.) This book has, famously, a lot of digressions. Hugo will stop the action to tell you about the history of the Paris sewers or underworld slang or the battle of Waterloo. They can seem irrelevant. They're not--they're really the heart of the book--though in ways that aren't always obvious on first reading.

The thing I would keep in mind is that the digressions are where Hugo hides things from the censors. I'm just going to quote what I told plaidadder:

LM was published ten years into Hugo's twenty-year-long political exile from France, for a French audience, using the plausible deniability of historical fiction to write about the current French regime and encourage its overthrow. When you get to the Paris sections, there will be asides every time he introduces a new setting apologizing for not being able to verify the details of the neighborhood as it presently looks, because it's been a while since he's been in Paris--these are all meant to remind the contemporary reader why that is: That the regime of Napoleon III, who had been elected President of the Second Republic and declared himself Emperor, would have arrested Hugo instantly if he'd returned. Hugo is writing to remind the French people that they have toppled tyrannical regimes before and they can do it again. But to make that case, he has to get this book past Napoleon III's censors. This need shapes the entire structure of the book. It's a large part of why the focus is on the rebellion of June 1832, which failed, and not those of July 1830 or February 1848, which were immediately successful (though less so in the long run). It's part of why the depiction of that rebellion, though it is the book's climax, comes so far from the end and why the rest of the denouement is such an extreme tonal shift. It's part of why his arguments with Napoleon I form such an important thematic throughline. And it is absolutely why the digressions are placed where they are, and why they're so long, and honestly why they're deliberately kind of dense and impenetrable--Hugo is counting on the censors to see the digressions as unconnected to the story and not read them carefully, when really, they're the places the book's argument comes the closest to the surface. tl;dr: The digressions should be read in a spirit of "Mods are asleep, post sedition!"

has anyone here read les mis and what did you think of it. i am vaguely thinking of reading it but idk if i really want to or not

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hmm... I think there's something to be said about the way Napoleon said, "There is no immortality but the memory that is left in the minds of men... to have lived without glory, without leaving a trace of one's existence, is not to have lived at all," and then Victor Hugo in the Waterloo digression explains how Napoleon's supposed "greatness" and his ambition to achieve glory was causing an imbalance to the universe, that "the world going to one man's head--would be fatal to civilization... [and that t]he stench of spilled blood, cemeteries filled to overflowing, weeping mothers"( 2.1.9.)--the result of Napoleon's quest for glory so he could live with glory and therefore immortalize himself--was so wrong a cause that he and his actions became "an inconvenience to God." (2.1.9.)

This, compared with the way he describes Les Amis as a group of young indvidiuals who end up "swallowed into the darkness of a tragic episode," but also, just before that, writes on how "[t]his group was remarkable." (3.1.4.) Who remembers the insurgents of 1832? Victor Hugo makes it a point to ensure the reader understands that no one ends up remembering the names of the Amis--he titles their first chapter "A Group That Almost Became Historic." (3.1.4.) But he also insists that the reader understand that they were heroes despite the fact that their names ended up lost in the pages of history--on several places he remarks their deeds with the word "heroes."

Napoleon spoke of not having lived if one does not live with glory. For his actions being remarkable, it resulted in an inconvenience to both God and history that cannot decide upon a verdict of his rule and fights. For Les Amis, who died in obscurity, having achieved no glory enough to have a name to history, Victor Hugo calls them remarkable and heroes. Their goal was not to achieve glory for themselves; there was no intent of writing their personal names into history. Their goal was to achieve a revolution, in Enjolras' words, "the revolution of Truth." (5.1.5.) And therein lies the difference between selfishness and selflesness, for Hugo. Those who seek greatness are reduced to historical debate and those who reject greatness are themselves made great in principle, if not in history.

#it was just a thought...I could be wrong#les amis de l'abc#victor hugo#napoleon bonaparte#history#possibly???#idk#les mis meta#les miserables#les miserables meta#orestes fasting pylades drunk

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

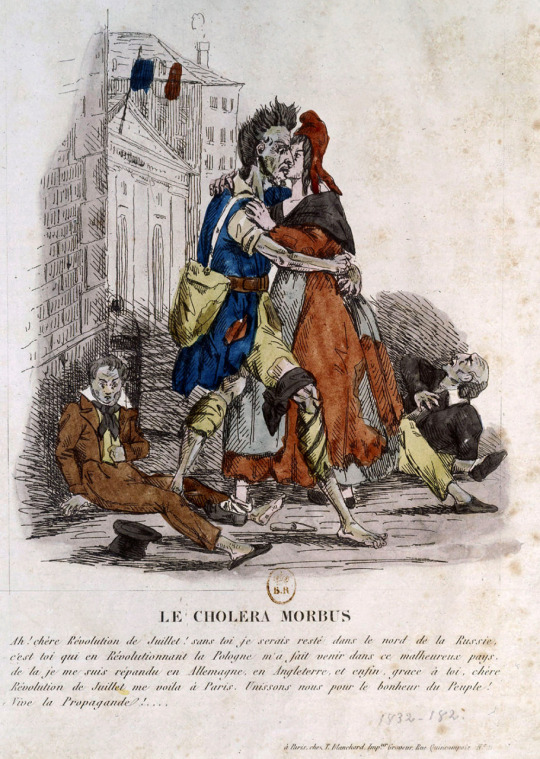

One more mention of cholera! I really miss the cholera digression in the Brick. Was it so hard to write one more digression? Marius and Cosette did not notice it, so we also should not notice it. Though it was such a big thing and claimed around 19,000 lives in six months. How preoccupied one should be not to notice it! And Hugo was obviously not interested. None of those several dozen inhabitants of Paris who operate in Les Mis died of it (Lamarque doesn’t count, he is not a character here) – it’s a miracle! I really want to know how Jean Valjean reacted to the news about the cholera epidemic. Did he stay home more than usually? Did he not worry about it at all? (In the next chapter, we'll find out that it did not affect his habit of going out to walk in the evening.)

Cosette and Marius continue learning new things about each other, and they find further similarities and differences in their life stories. Marius is trying to brag about his baron title, and Cosette reaction is just adorable: “this had produced no effect on Cosette. She did not know the meaning of the word. Marius was Marius.”

This chapter is not as easy-going as the previous one. “Loving almost takes the place of thinking,” alerts Hugo. It’s about Marius, who tries to brush aside memories about the Gorbeau house adventure, though he subconsciously understands that this is important, and they should have discussed it with Cosette. Instead, he suppresses this memory, preferring to remain in “a rosy cloud.” This will hit them quite painfully.

Cholera-related cartoon from 1832:

#les mis letters#lm 4.8.2#les miserables#cosette#marius pontmercy#jean valjean#cholera#gorbeau house raid

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deconstructing Mormon Hymns #5

Hymn #26

Oh how lovely was the morning!

Radiant beamed the sun above.

Bees were humming, sweet birds singing,

Music ringing thru the grove,

When within the shady woodland

Joseph sought the God of love

When within the shady woodland

Joseph sought the God of love.

Okay. This verse says Joseph Smith went out to the woods to pray. Only the last and Official version of the event (Written in 1838 and published in 1842) mentions a grove of trees. The first few versions do not mention anything about a location. In regards to his age, the Official version says he was 14, and earlier versions – accounts written in Joseph's own hand – say he was fifteen or sixteen. What was he seeking? Official version says Joe wanted to know which church was right. The account written first by Joe says that he had decided that mankind had “apostatized from the true and living faith and there was no society or denomination that built upon the gospel of Jesus Christ.”

Language wise? This verse is evocative of peace and tranquility. Sacredness. The natural peace and spirituality (not Mormonspeak spirituality, I mean legitimate, human beings love being outside spirituality) that comes from being in the woods and in nature. This is on purpose. Once you tie religious dogma to the natural human instinct and response to being in a nice place, whenever you are in a nice place you think of the dogma. I still sometimes go out on a hike, stumble upon a pretty clearing in the woods, and am reminded of this song and the story.

Humbly kneeling sweet appealing -

'Twas the boy's first uttered prayer -

When the pow'rs of sin assailing

Filled his soul with deep despair;

But undaunted, still he trusted

In his Heav'nly Father's care,

But undaunted, still he trusted

In his Heav'nly Father's care

So here we have random dark powers attacking young Joe as he tried to pray to god. This is the Official version. Joseph's handwritten version (1832) has no mention of being attacked by anything evil. The 1832 version just mentions that he was “filled with the spirit of God and has his sins forgiven”.

Language wise, we have some more evocative imagery going on. Humble boy sweetly asking for help! So innocent! So naive but trusting! All qualities we are expected to strive for. They are vague and perpetually adjusting. Think purity culture, think childlike dependency.

Suddenly a light descended,

Brighter far than noonday sun,

And a shining, glorious pillar

O'er him fell, around him shone,

While appeared two heav'nly beings

God the Father and the Son,

While appeared two heav'nly beings,

God the Father and the Son.

The handwritten account (1832) mentions fire, not light, in a pillar. This is where things get really sketchy. Two beings, god and jesus, is the Official version (published 1842). The handwritten account only mentions one being, assumed to be christ, and addresses Smith as his son.

In 1835 a version is written that one being appeared in flame, and a second appeared and forgave Joe of his sins, then testified of jesus. This implies that neither being is god or jesus. Joe calls them angels, and this is where he says he was fourteen.

The language here is pretty typical of stuff surrounding descriptions of god and jesus. Noonday sun, light, glorious, shining, heavenly. All kinda vague attributes, but goddamn it sticks in the brain. I will forever, forever associate “noonday sun” with this song.

“Joseph, this is my Beloved;

Hear him!” Oh how sweet the word!

Joseph's humble prayer was answered,

And he listened to the Lord.

Oh, what rapture filled his bosom,

For he saw the living God,

Oh what rapture filled his bosom,

For he saw the living God.

Okay, kinda bold to put words in gods mouth. Also, given gods track record, doesn't it seem that god would stay silent and make jesus praise him? I digress. Joseph's “humble prayer” is from the latest version, the whole “which church is true?” question. The whole conversation jesus is supposed to have with Joe isn't in the first few accounts of the event. Joe originally decided he was just going to ask forgiveness and roll from there.

Listened to the lord? Debatable. When you change the story, when you change what god orders you to do retroactively, you can make it seem like you always listened to the lord. And again, joseph decided that he saw both god and jesus in the final version. The first few versions were either just jesus, or only angels.

The language of this verse makes me want to roll my eyes. More fawning over how humble joseph was, how glorious god is, ad neaseum.

Musically, this song is gentle and sacred. I mean that in the heaviest of mormon terms, by the way. This song is treated just as sacred or even more sacred than some of the songs about the crucifixion or the atonement. Mormons will deny it left and right, but they worship and revere Joseph Smith more than they focus on christ.

TL;DR: Joe smith couldn't get his story straight, at all, ever. The church picks the version they like the best, omit anything that they don't like, and slap the word “truth” all over it. Then get mad when you say otherwise.

Historical Source: https://www.themormondelusion.com/the-first-vision

#exmormon#exmo#ex lds#ex cult#apostake#im feeling very exmo in this chilis tonight#deconstructing#deconstructing mormon hymns#@dreamcatcher24601

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Premise: this answer is not *against* yours, it's just what I thought while reading your reblog. Some things are direct answers, most stuff is related to what you said but they are comments more than counterarguments.

So I share your preference for characters, it's just I'm a big fan of historical and architectural details as well. Sure I could look up the sewers on Wikipedia but would I? No, there is too much choice and I wouldn't pick up the sewers randomly. I just like info I guess, I'm not able to explain why.

But I think super detailed descriptions serves the plot as well. Place descriptions shape the verse the story is in and shape the narrative tone as well, historical digression are useful to understand the characters if you are into them. I'm bringing a negative example I already alluded to in the OG post, skipping the 1830 revolution fucked up a bit the understanding of the motives of Enjolras and comrades to our modern eyes, some readers tend to judge Enjolras' determination as misplaced, naive and unnecessarily violent while if you know how 1830 and the aftermath went you get why revolution felt both like a necessity and very achievable to Les Amis. You also can understand why on the other side people was tired of the frequent republican revolts and lost faith. I get why Hugo didn't feel the need to include it, because he wanted to be Les Amis and the 1832 uprising symbols more than specific historical events related with other specific historical events, besides he thought all those events were obvious to the reader but now it's not true anymore so a historical digression would have been useful to better understand the characters. True, one could look up the details on Internet but how many people have done that?

Then

1)like you implied, fictional books had a strong divulgative role in the past but I don't think this role is dead. A fictional plot is still a motivator to learn "actual" knowledge for a lot of people. This goes for TV shows as well. Offtopic, that's why well written misinfo is dangerous in fiction, people learn from them.

2)A writer writes for fun too. So "for fun" is enough to answer to "why did Hugo add that". Obviously the reader is allowed to be bored while reading it, myself I like almost none of the canon romances I read from Hugo and I'm sure he enjoyed writing all of them. So I'm not saying you should enjoy everything the writer puts in a book, just that fun is a sufficient justification for adding one more digression/plot. I happen to love them anyway.

Anyway I prefer characters' details as well (but I like all kinds like I said) but the preference for characters' details is not universal, you and I love them, other people think they're a waste of time and words. There are also writing advices that suggest to avoid everything is not necessary to understand the main plot. So I don't think the contemporary culture favours character details over places and history, it may be a matter of personal preference as well.

I know Hugo's love for details gets made fun of a lot but I think it's honestly endearing. The sewer exploration was really interesting, I can't say Myriel's background left a mark in me but it was so pleasant to read. Loved the descriptions of Paris, the description of the light related to what was happening in the city. In fact often I've been left wanting more details when I read Les Miserablès (and Hugo in general). Why did Grantaire have that Robespierre waistcoat? How bad was his relationship with his father? How was he ugly? How was Enjolras' relationship with his (human) mother? How much did Cosette remember of Eponine? Would she be resentful? Favourite and Fantine. The whole story of Le Cabuc that sounds interesting as fuck? How did Les Amis react to 1830 victory (actually I think skipping the 1830 revolution brought some issues to the 1832 uprising plot)? How did they react when their victory was stolen? The background of Valjean and his sister? What was the impact of the ethnicity of Javert's mother on Javert? Etc etc

It's also... "relaxing", I don't know... in Les Mis as well in other novels of his, when I met a character I get to know their personality, at least a brief backstory usually, the context of their behaviour. If something happens I know how it happened usually. I don't have to keep asking myself wtf is happening, I don't have the risk to miss crucial event or motivations. And I can see literally the events unfold behind my eyes, either because the author is precise with his material descriptions or because he gets to portrait the "vibes" with vividness.

72 notes

·

View notes